Abstract

The Czech Republic submitted a request to the European Commission to be recognised as a Member State with negligible risk of classical scrapie. EFSA has been asked to assess if the Czech Republic in its application has demonstrated for a period of at least 7 years (2015–2021) and proposed for the future, that a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, representative of slaughtered, culled or found dead on farm animals, have been and will continue to be tested annually to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting classical scrapie if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%. A risk‐based approach using stochastic scenario‐tree modelling accounting for surveillance stream and species was applied. There is still a lack of data on the actual performance of the approved tests under field conditions, especially in sheep. Therefore, alternative scenarios were explored extending the range from the sensitivity provided by the past European Union evaluations of diagnostic screening tests to a sensitivity of 50%, consistent with published data obtained under field conditions in infected goat populations. Using data provided by the Czech Republic for 2015–2022, the estimated parameters of the scenario‐tree model, the range of values of diagnostic sensitivity and applying the criterion for the 95% confidence level, it is concluded that the Czech Republic has tested annually a sufficient number of small ruminants to meet the requirement, for all combinations of years and diagnostic sensitivity scenarios except for 60% diagnostic sensitivity in 2021 and 2022, and 50% in 2015, 2016 and 2018–2022. Based on the proposed number of samples to be tested in 2023 and future years, the Czech Republic would test a sufficient number of animals to meet the requirement for all combinations of diagnostic sensitivity, except for the 50% scenario.

Keywords: scrapie, negligible, risk, classical, Czech Republic, surveillance

Summary

Since 1 July 2013, Member States (MS) have been able to submit a request to the European Commission to be recognised as a MS, or zone of a MS, with a negligible risk of classical scrapie (CS). The Czech Republic [Czechia] submitted a request in May 2022 to be recognised as a MS with negligible risk of CS. The European Commission requested the technical assistance of EFSA, to assess if the Czech Republic in its application: (a) has demonstrated that, for a period of at least 7 years, a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, representative of slaughtered, culled or found dead on farm, have been tested annually, to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%; (b) and will continue to carry out annually a sufficient number of tests of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, representative of slaughtered, culled or found dead on the farm, to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%, in order to maintain their status.

As in the three previous evaluations conducted in 2015 for Denmark, Finland and Sweden (EFSA, 2015a,b,c), a risk‐based method using scenario tree modelling with stochastic simulation in order to account for the uncertainty of the estimated parameters was applied to estimate the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system (SSe) of the Czech Republic. The model was developed using R and has been made publicly available. Two risk indicators, namely surveillance stream and species, were considered. The estimation of the relative risk of not slaughtered for human consumption (NSHC) versus slaughtered for human consumption (SHC) streams, and of sheep versus goats was done by analysing surveillance data at MS level between 2009 and 2021.

Currently, there are no data to quantify, at European Union (EU) level, the overall diagnostic sensitivity of the screening diagnostic tests for the detection of CS in small ruminants over 18 months of age under field conditions. The only data available are from the results of the EU evaluations in relation to the sensitivity of the tests approved at EU level. The sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests (rapid tests) under field conditions is considered to be lower than sensitivity estimates obtained under laboratory conditions. Given the uncertainty about the field sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests, alternative scenarios were explored extending the range from the sensitivity provided by the EU evaluations down to a sensitivity of 50%. This is consistent with published data obtained under field conditions in infected goat populations.

As agreed in previous evaluations and for consistency purposes, given a design prevalence (DP) (0.1%), N and n, for each combination of year and test sensitivity, the 95% confidence level of detecting CS was considered achieved when the SSe was 95% or greater at the 5th percentile of the output distribution of the model.

Based on the test sensitivity derived from the EU test evaluation data and from any of the alternative scenarios, during the period 2015–2022, the Czech Republic has tested annually a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, sourced from the NSHC and SHC, to ensure a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%, for all combinations of years and diagnostic sensitivity scenarios except: 60% diagnostic sensitivity in 2021 and 2022, and 50% in 2015, 2016 and 2018–2022.

Based on the expected number of samples claimed to be tested in 2023 and future years and on the test sensitivity derived from the EU test evaluation data and from any of the alternative scenarios, the Czech Republic proposes to test annually a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, sourced from the NSHC and SHC, to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%, for all combinations of diagnostic sensitivity, except for the scenario of 50%.

The sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests under field conditions is a key parameter when estimating the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system. There is still a lack of data on the actual performance of the approved tests in field conditions, particularly for sheep. It would be advisable to generate such data.

Some of the parameters used in this assessment are dynamic. Prior to the assessment of any subsequent application, parameters relating to risk factors and test sensitivity should be reviewed and, if necessary, updated.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and terms of reference as provided by the requestor

Since 1 July 2013, according to Annex VIII, Chapter A, Section A point 2 to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001, a Member State (MS) can submit a request to the Commission to be recognised as a MS, or zone of a MS, with a negligible risk of classical scrapie (CS). In this case, the Commission (EC) should evaluate this request based on the criteria laid down in point 2.1, and, if the evaluation is positive, the negligible risk status may be approved based on a comitology regulatory procedure with scrutiny. The criteria laid down in point 2.1 are based on those mentioned in Article 14.8.3 of the Terrestrial Animal Health Code of the World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH).

The Czech Republic submitted a request to the Commission to be recognised a Member State with negligible risk of classical scrapie on 12 May 2022. The Commission assessed this application positively as regards the criteria in items (a), (b), (d), (e) and (f) of Chapter A, Section A, point 2.1 of Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001, but so far did not conclude its assessment as regards item (c).

Item (c) of Chapter A, Section A, point 2.1 of Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 reads as follows:

“(c) for a period of at least seven years, a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, representative of slaughtered, culled or found dead on farm, have been tested annually, to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1% and no case of CS has been reported during that period.”

Furthermore, point 2.2 of Chapter A, Section A of Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 specifies that:

“2.2 The Member State is to notify the Commission of any change in the information submitted according to point 2.1. relating to the disease. The negligible risk status approved in accordance with point 2.2. may, in the light of such notification, be withdrawn in accordance with the procedure referred to in Article 24(2).”

This implies that the number of tests required for at least the last 7 years according to item I of point 2.1, should also be maintained in the future for the classical scrapie negligible risk status to be retained.

In the framework of Article 31 of Regulation (EC) No 178/2002, the Commission requests the technical assistance of EFSA to assess if the Czech Republic:

has demonstrated that, for a period of 7 years (2015–2021), a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, in the testing streams ‘slaughtered for human consumption’ and ‘not slaughtered for human consumption’, has been tested annually to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting classical scrapie if it was present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%.

and will continue to carry out annually a sufficient number of tests of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, in the testing streams ‘slaughtered for human consumption’ and ‘not slaughtered for human consumption’, to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting classical scrapie, should it be present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1%.

1.2. Interpretation of the terms of reference (if appropriate)

The EFSA working group (WG) agreed to clarify the following points:

Retrospective analysis of surveillance data is conducted on an annual basis, i.e. estimating the confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1% in each year separately. EFSA has not considered any method that accounts for the cumulative evidence provided by the analysis of historic surveillance data.

The period for which surveillance data should be analysed retrospectively is 2015–2021, as in the terms of reference (ToR). However, due to the gap between the submission of the application to the European Commission and the submission of the mandate to EFSA, full data for 2022 were available at the time of analysis and will be analysed as well.

The assessment of whether or not the Czech Republic will continue to carry out a sufficient number of tests will refer to the future in general and not just specifically to 2023, the first year after the retrospective analysis.

Even though sheep and goats will be considered as a single population (small ruminants) in the assessment, prevalence data will be stratified by species.

The assessment will be conducted using raw data provided by the Czech Republic in the dossier and new data that they may provide upon request. The assessment will also consider other data and information contained in the dossier that may help with the assessment, such as demographic data, organisation and implementation of the surveillance system, selection of animals for testing, etc. The aspects of the dossier which are not relevant for the assessment as required in the ToR will not be considered.

In the Guideline for drafting a dossier for the recognition of a Member State or zones of a Member State with a negligible risk of classical scrapie Version 6, it is stated that ‘for the calculation it is recommended to use a scenario‐tree modelling, similar to that used by EFSA in its 2015 scientific reports on the evaluation of the application of Sweden/Finland to be recognised as having a negligible risk of classical scrapie, assuming that the sensitivity of the surveillance system is equivalent to the diagnostic sensitivity provided by the past evaluations of screening diagnostic tests by the EFSA and the Joint Research Centre Institute for Reference Materials and Measurement (IRMM) (see Appendix A of the EFSA scientific reports)’. The EFSA WG producing this assessment will apply the same methodology in accordance with the Guideline (EFSA, 2015a,b,c).

1.3. Additional information (if appropriate)

While reviewing the dossier submitted by the Czech Republic, and in order to implement the analytical approach agreed by the EFSA WG producing this assessment (see Section 2.2), it was considered necessary to request additional data or re‐submission of the data already provided in a different format, or at a different resolution level. In particular, EFSA requested the Czech competent authority to:

confirm that the numbers of tested sheep and goats in the SHC and NSHC in 2022 as extracted from the EFSA database are correct.

provide the population of sheep and goats in the SHC and NSHC groups in 2022.

specify how 3,000 tested small ruminants will be split between sheep and goats in the two surveillance groups in future, to clarify the text in the application, where it is stated that ‘The Czech Republic will continue with testing of all fallen stock, emergency slaughtered or killed ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age in order to comply with point 2.1(c) of Section A, Chapter A, Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No. 999/2001. This means that, as in period 2015‐2020, circa 3000 animals will be annually tested’.

The Czech Republic submitted the additional data and information, as requested.

2. Data and methodologies

2.1. Data

2.1.1. Population and surveillance data for the Czech Republic

Demographic and surveillance data, including the number of sheep and goats tested for scrapie, test results and future plans for surveillance were obtained from:

the original application, plus information included in further communications between the European Commission and the MS;

additional data provided by the Czech Republic upon request, as described in Section 1.3.

2.1.2. EU surveillance data

EU surveillance data at MS level have been extracted from the EFSA TSE database and from the EU summary reports published by the European Commission prior to 2016. In the previous evaluations, the historical data available covered a period of 13 years from 2002 until 2014. In order to be consistent, a period of 13 years was used for the current evaluation, covering the period 2009–2021.

Historical data were extracted in a matrix format including the following fields: country (EU member state), species (sheep/goats) surveillance groups (NSHC/SHC), year (2009–2021), number of animals tested and number of classical scrapie cases.

In 2009 and 2010, the EU reports included the total number of TSE cases and the number of atypical cases, but not split by surveillance groups. The number of classical scrapie cases was estimated by subtracting from the total number of scrapie cases the number of atypical scrapie (AS) proportional to the number of total cases in the two surveillance groups: SHC and NSHC. Otherwise, there would be atypical scrapie cases in the data set incorrectly classified as classical scrapie.

The surveillance group eradication measures (EM) were excluded as this was also done in previous evaluations. To maximise the number of cases in the calculation of relative risk, the number of tested animals and number of cases in SHC and NSHC were extracted from both infected and non‐infected flocks.

The final data set contained a total of 3,275,368 small ruminants: 2,277,649 sheep and 997,719 goats. In total, 1,788,379 were tested in the NSHC group and 1,486,989 in the SHC group. Tables A.1 and A.2 of Appendix A show the distribution of animals tested and cases by country, and species (Table A.1) or surveillance stream (Table A.2).

Table A.1.

Summary of the surveillance data by species for the period 2009–2022 included in the calculation of the relative risks

| Country | Goats | Sheep | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total tested | Number classical scrapie cases | Total tested | Number classical scrapie cases | Total tested | Number classical scrapie cases | |

| BG | 10,786 | 21 | 108,714 | 20 | 119,500 | 41 |

| CY | 73,187 | 2,745 | 48,105 | 86 | 121,292 | 2,831 |

| DE | 89,755 | 17 | 89,755 | 17 | ||

| DK | 6,067 | 0 | 6,067 | 0 | ||

| EE | 621 | 0 | 621 | 0 | ||

| EL | 50,188 | 135 | 139,811 | 1,485 | 189,999 | 1,620 |

| ES | 206,686 | 59 | 283,439 | 285 | 490,125 | 344 |

| FI | 349 | 1 | 949 | 3 | 1,298 | 4 |

| FR | 311,870 | 12 | 239,908 | 20 | 551,778 | 32 |

| HU | 38,572 | 3 | 38,572 | 3 | ||

| IE | 146,917 | 71 | 146,917 | 71 | ||

| IS | 16,874 | 7 | 16,874 | 7 | ||

| IT | 265,071 | 86 | 311,891 | 659 | 576,962 | 745 |

| NL | 61,992 | 7 | 61,992 | 7 | ||

| PL | 14,565 | 5 | 14,565 | 5 | ||

| PT | 14,482 | 2 | 192,368 | 25 | 206,850 | 27 |

| RO | 54,632 | 13 | 384,161 | 803 | 438,793 | 816 |

| SE | 11,304 | 3 | 11,304 | 3 | ||

| SI | 7,175 | 4 | 7,175 | 4 | ||

| SK | 53,211 | 45 | 53,211 | 45 | ||

| UK | 10,468 | 78 | 121,250 | 106 | 131,718 | 184 |

| Grand total | 997,719 | 3,152 | 2,277,649 | 3,654 | 3,275,368 | 6,806 |

Table A.2.

Summary of the surveillance data by surveillance stream for the period 2009–2022 included in the calculation of the relative risks

| Country | NHSC | SHC | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total tested | Number classical scrapie cases | Total tested | Number classical scrapie cases | Total tested | Number classical scrapie cases | |

| BG | 5,688 | 6 | 113,812 | 35 | 119,500 | 41 |

| CY | 70,710 | 1,687 | 50,582 | 1,144 | 121,292 | 2,831 |

| DE | 60,354 | 13 | 29,401 | 4 | 89,755 | 17 |

| DK | 6,067 | 0 | 6,067 | 0 | ||

| EE | 621 | 0 | 621 | 0 | ||

| EL | 93,035 | 1,313 | 96,964 | 307 | 189,999 | 1,620 |

| ES | 300,783 | 268 | 189,342 | 76 | 490,125 | 344 |

| FI | 1,298 | 4 | 1,298 | 4 | ||

| FR | 467,638 | 26 | 84,140 | 6 | 551,778 | 32 |

| HU | 14,023 | 0 | 24,549 | 3 | 38,572 | 3 |

| IE | 104,129 | 65 | 42,788 | 6 | 146,917 | 71 |

| IS | 201 | 3 | 16,673 | 4 | 16,874 | 7 |

| IT | 232,831 | 437 | 344,131 | 308 | 576,962 | 745 |

| NL | 19,716 | 3 | 42,276 | 4 | 61,992 | 7 |

| PL | 6,355 | 3 | 8,210 | 2 | 14,565 | 5 |

| PT | 102,246 | 16 | 104,604 | 11 | 206,850 | 27 |

| RO | 139,225 | 276 | 299,568 | 540 | 438,793 | 816 |

| SE | 11,304 | 3 | 11,304 | 3 | ||

| SI | 7,175 | 4 | 7,175 | 4 | ||

| SK | 49,380 | 23 | 3,831 | 22 | 53,211 | 45 |

| UK | 95,600 | 159 | 36,118 | 25 | 131,718 | 184 |

| Grand total | 1,788,379 | 4,309 | 1,486,989 | 2,497 | 3,275,368 | 6,806 |

2.1.3. Sensitivity of diagnostic screening tests

Data and information on the performance of diagnostic screening tests approved for the monitoring of TSE in small ruminants in the EU under laboratory conditions have been sourced from the reports of the Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements (IRMM) and EFSA Opinions (IRMM, 2005a,b,c; EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2010, 2012; EFSA, 2015a,b). These data were produced in the framework of the past EU evaluations of post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests for the detection of TSE in small ruminants and are used in the present report as estimates of the analytical sensitivity of the EU tests i.e. under laboratory conditions (for more details, see Appendix B), and therefore represent a ‘best‐case scenario’ when applied under field conditions (see Section 2.2.3.2).

2.2. Methodologies

Scenario tree modelling using a stochastic approach was the analytical method selected for this assessment, to maintain continuity of approach with previous similar evaluations (EFSA, 2005a,b) and in accordance with the Guideline for drafting a dossier for the recognition of a Member State or zones of a Member State with a negligible risk of classical scrapie Version 6, and Regulation (EC) No 999/2001.

2.2.1. Risk‐based surveillance using scenario tree modelling

For a disease as complex as CS, which is characterised by a long incubation period, the absence of any in vivo diagnostic method and the variable susceptibility of individual animals depending on their genetic profile, it is difficult to demonstrate freedom from disease in the territory or part of the territory of an MS. The concept of ‘CS‐free MS’ has therefore been replaced in Annex VIII to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 by that of ‘MS or zone of a MS with a negligible risk of CS’ by Commission Regulation (EU) No 630/2013.

Commission Regulation (EU) No 630/2013 amending Annex VIII of Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 also aligned the criteria for a MS to be recognised as having a ‘negligible risk of CS’ with those laid down in Article 14.8.3 of the WOAH Terrestrial Animal Health code for ‘scrapie‐free country or zone’.

ToR1 of the mandate for the present report refers to a surveillance strategy that must comply with the concept of ‘freedom from disease’, i.e. the situations in which the monitoring activity is carried out to detect or exclude the occurrence or recurrence or emergence of a disease (Doherr and Audigé, 2001).

Owing to the constraints of the nature of the disease, the application of sampling strategies and the limitations of diagnostic test performance, it is not possible to achieve absolute proof of freedom from disease. Thus, a probabilistic approach is used based on the accumulation of evidence (Cameron, 2012). The implication of such a strategy is that the level of confidence that an animal population is ‘free’ from disease is proportional to the sample size, the design prevalence and the accuracy of the diagnostic test in terms of sensitivity and specificity (FAO, 2014):

the sample size, i.e. the number of animals sampled; the larger the number of animals submitted to testing, the greater is the likelihood of detecting the disease.

The design prevalence (DP); i.e. the assumed prevalence of disease if it is present and also the probability of infection for each animal in the population; the lower the DP is, the larger will be the effort needed to detect the disease. In ToR 1, it is 0.1%.

The accuracy of the diagnostic test in terms of sensitivity and specificity. Sensitivity is a key factor in terms of both the sensitivity of the diagnostic screening test and the sensitivity of the surveillance system, i.e. the probability that the surveillance system would detect disease if it were present. Therefore, maximising the sensitivity strengthens the confidence in freedom, reducing the uncertainty when communicating results. On the other hand, specificity is not a problem when trying to substantiate freedom from disease (Martin et al., 2007). Even if potential false positives can compromise the freedom statement, each initially positive animal should be subject to further confirmatory testing. As highlighted in a previous EFSA Technical Report, each surveillance system should encompass all the necessary follow‐up testing to resolve potential false‐positive results (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2012).

A surveillance system can be thought of as a type of diagnostic screening test on the entire population: The population does have or does not have a disease, and the surveillance is applied in order to make a decision on the disease status. The ability of a surveillance system to correctly identify a diseased population is analogous to the ability of a diagnostic test to identify a diseased animal (FAO, 2014). It is measured quantitatively by the sensitivity of the surveillance system, i.e. the level of confidence of detecting the disease mentioned in ToR 1.

As discussed in Stärk et al. (2006), it had been argued by Martin and Cameron (2003) that the assumption in traditional surveillance that the probability of disease is constant across all individuals in the reference population is not realistic. A single standard value for the DP would imply that all animals in the population have, on average, the same probability of being infected. This is never true: Animals vary in their probability of becoming infected and in their probability of being recognised/detected as sick, depending on the nature of the disease and on their susceptibility to it. To deal efficiently with such a context, the evaluation of surveillance systems can be achieved using scenario trees similar to decision tree structures.

The scenario tree is a modelling format for analysis of surveillance systems under a null hypothesis of the country being infected at a level equal to or greater than the specified prevalence. A scenario tree is developed to represent all applicable relevant factors influencing the probability that a unit in an infected population will be detected as infected. The conditional probabilities associated with each branch of the tree are then multiplied together to give the overall probability of each branch outcome, and these are added up for all branches with positive outcomes to give the probability of the whole surveillance process having a positive outcome for a randomly chosen population unit, given that infection is present in the country. The infection and detection nodes of their trees represent factors affecting the probability of disease occurrence in subpopulations that may be targeted by surveillance.

Scenario trees allow the evaluation of the contribution of risk‐based surveillance that aims to take into account the differences in risk (probability of detection) among animals in the population. In particular, by selecting animals with a higher probability of being infected or a higher probability of being detected if they are infected, the sensitivity of the surveillance can be increased without increasing the total number of animals being tested (FAO, 2014). If surveillance is targeted towards a group of animals that are at higher risk of being infected, a scenario tree allows us to calculate the sensitivity that we achieve for that particular group. For details of the calculation of the sensitivity of the surveillance system, see Section 2.2.2.

To conduct the estimation of the sensitivity of the surveillance system using scenario tree modelling, a tailor‐made model was coded using R software (R Core Team, 2022). The model was validated against the results of the previous evaluations and by comparing them with those produced by the modified risk‐based sensitivity tool (RiBESS) (EFSA, 2012), which is an Excel®‐based user‐friendly tool. To conduct Monte Carlo simulations, the tool is linked to the Microsoft Excel add‐in tool @Risk 7.6 (© 2018 Palisade Corporation). One hundred thousand iterations were used for each simulation performed, which ensured convergence of the model. The R code of the scenario tree model, a readme file and an Excel file containing the input data for the Czech Republic can be accessed in the following link: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8387106.

2.2.2. Estimation of the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system (SSe) using scenario tree modelling

Scenario tree modelling effectively divides the population into different risk groups based on known risk indicator(s), in this case species and surveillance stream. By applying relative risk of infection in each of these groups, the DP, i.e. the theoretical overall probability that a random unit is infected is adjusted in order to estimate the group‐level probability of infection, i.e. the ‘actual’ probability that a random unit from a specific group is infected, based on the available data on the relative risk for the risk indicator/s.

To summarise, a scenario tree is a tool to assist in the calculation of the sensitivity of a component of a surveillance system (FAO, 2014). In contrast to the simple analysis of representative surveys, the purpose of a scenario tree is to take into account the fact that not all animals in the population:

have the same probability of being infected (some are at greater risk than others);

have the same probability of being detected (the sensitivity of detection is greater in some animals than others).

Once the risk indicators are identified and the associated risk parameters estimated, it is possible to combine the different levels in order to obtain the risk groups. If two risk indicators are identified with two levels (categories) each, the four different risk groups can be obtained. Table 1 below shows the distribution of risk groups in the case of two risk indicators with two categories each.

Table 1.

Theoretical distribution of risk groups using two risk indicators with two categories each

| Risk indicator I | Risk indicator II | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RI_IIa | RI_IIb | |||||

| RI_Ia |

Group: 1 |

Group: 2 |

||||

| RI_Ib |

Group: 3 |

Group: 4 |

||||

For each risk group, the weighted risk (WRi) is calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where CombRPi is the risk parameter for the ith specific risk group (combination of the two risk indicators), PopPropi is the fraction of the total population allocated in the ith specific risk group and r is the total number of risk groups, i.e. four in the example.

Using WRi, it is then possible to calculate the effective probability of infection for each risk group i (EPIi) as follows:

| (2) |

where DP is the overall design prevalence and WRi is the weighted risk for each group.

Once the EPIi values are estimated, they can be used as a better estimate at group level in order to calculate:

the sample size required in each group in order to have a probability of detecting at least one positive animal, should the actual prevalence be above the EPIi; or

the sensitivity of a round of testing (RSe), i.e. the probability that at least one animal out of the tested animals will return a positive result, should the actual prevalence be above the EPIi at group level.

The RSe is calculated for a finite population as follows:

| (3) |

where n is the sample size, DP is the design prevalence, TSe is the sensitivity of the test and N is the total population size. The group sensitivity for group i (GSei) can be calculated for each group just by substituting DP for EPIi, with ni, being the sample size in each risk group and Ni the total population in each risk group:

| (4) |

It is now possible to estimate the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system () as follows:

| (5) |

where SSe is the system (overall) sensitivity, gSei is the group sensitivity of each risk group and r is the number of risk groups included in the survey. SSe represents the ‘confidence’ of detecting the disease given DP, TSe, N and n. The SSe level required by the legislation is usually 95%.

2.2.2.1. Input parameters for the calculation of the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system (SSe) using scenario tree modelling

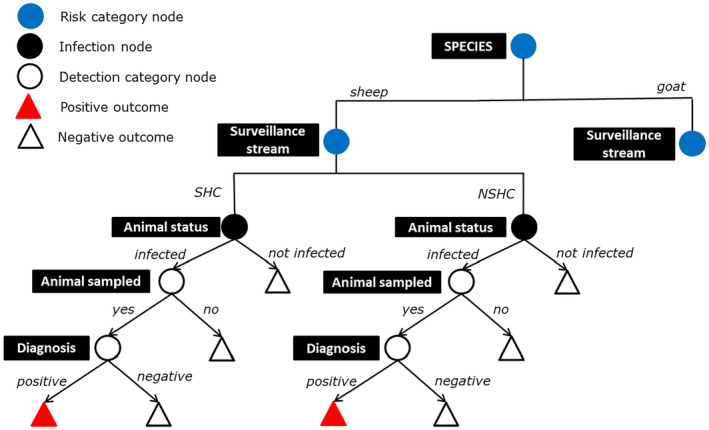

The methodology described above has been applied for the calculation of the annual SSe to detect scrapie at the designed prevalence of 0.1%. Two risk indicators have been selected: surveillance stream with two risk categories (NSHC, SHC), and species with two risk categories (sheep, goats), as displayed in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Scenario tree flow diagram of the analysis of the active surveillance system for CS

- Only the sheep section is shown. The same tree applies to the goat section.

For the calculation of the SSe, two different categories of parameters are used: those common to all MS and MS‐specific parameters.

2.2.3. Common parameters of the scenario tree modelling

2.2.3.1. Design prevalence (DP)

Fixed according to the EU legislation: 0.1%.

2.2.3.2. Sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests (rapid tests) (TSe)

Various prion protein (PrP) detection methods can be applied in the context of statutory surveillance (enzyme‐linked immunosorbent assay, Western blot, immunohistochemistry), but active surveillance screening in the EU requires that the method used must be listed in Regulation (EC) No 999/2001.

Initially, evaluation exercises were carried out using brain tissue from clinical cases of bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) in cattle, and tests performing satisfactorily on bovine tissues were provisionally approved for small ruminants and used for surveillance of TSE in sheep and goats (Commission Decision 2000/374/EC 1 ; Regulation (EC) No 1053/2003 2 ). In 2003, the European Commission launched a new evaluation of diagnostic and analytical sensitivity, diagnostic specificity and repeatability of post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests for TSE using natural CS samples. Based on the results of these evaluations (EFSA, 2005a,b; IRMM, 2005a,b,c), post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests were specifically approved for the detection of TSE in small ruminants (Regulation (EC) No 253/2006 3 ). Further modifications were made in 2008 and 2009, owing to the withdrawal from the market of some tests, and then in 2010 (Regulation (EC) No 956/2010 4 ), with some tests being delisted for performing poorly with regard to AS. The approved test list has remained stable since 2010, with the addition of one new test in 2012 as a result of a new EU evaluation procedure that started in 2008.

IRMM and EFSA published reports summarising the results of the 2003 and 2008 evaluations of the post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests for the detection of TSE in small ruminants (EFSA, 2005a,b; IRMM, 2005a,b,c, 2010; EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2012). When reviewing the results of the evaluations in relation to the diagnostic sensitivity of the tests recommended for approval and used, at least for some years in MS, the lowest reported value for diagnostic sensitivity was 99.6% (95% confidence interval (CI) 98.10–99.99%), based on an evaluation on 246 positive brainstem samples (Appendix B).

Additional requirements apply to approve diagnostic screening tests in terms of analytical sensitivity. All tests are required to fall within an analytical sensitivity of a maximal 2 log10 lower than that of the most sensitive test, based on a log dilution series from known positive samples. Despite the potential for apparent differences in analytical sensitivity, the EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (2009) concluded that ‘no potential differences in field detection performance can be inferred on the sole basis of the difference in analytical sensitivity reported’.

In practice, a number of factors other than the analytical sensitivity of a test under laboratory conditions affect the ability of the test to correctly identify sheep and goats affected by CS, and these are discussed below. These factors are difficult to quantify. They contribute to the uncertainty around the value of the parameter for the sensitivity of the test under field conditions and should be taken into account.

While testing laboratories are kept ‘under control’ by the regulatory requirement to apply tests within recognised quality systems (ISO, 2005) or equivalent (Regulation (EC) No 882/2004 5 ), the initial selection of animals and sampling of material falls largely outside of this procedural control.

Regardless of the analytical sensitivity of the test used, sample location is key to good diagnostic sensitivity of the test under field conditions. Current active surveillance screening looks in the brainstem for evidence of accumulation of the abnormal form (PrPSc) of the cellular PrP (PrPc).

Most of the published data related to PrPSc dissemination dynamics in sheep naturally affected with CS were obtained in sheep bearing the VRQ/VRQ genotype (for details, see EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2010). In these animals, lymphoreticular system (LRS) involvement starts in the gut in the first months post exposure, and thereafter spreads to all lymph nodes, reaching a plateau around 6 months post infection. It is not until an age of between 7 and 10 months that PrPSc becomes detectable in the central nervous system (CNS) (brain and spinal cord), where it accumulates following exponential kinetics. There is a paucity of relevant data related to CS dissemination in sheep of other genotypes. However, the data that do exist indicate that in other genotypes, the dissemination kinetics of the PrPSc is slower, and in some cases, there is also no LRS involvement (EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2010, 2014). Any brainstem samples from animals infected for less than a year are therefore likely to test negative. However, this should not affect the overall sensitivity of the diagnostic screening test in VRQ/VRQ animals since the minimum age for testing is 18 months of age, if it is assumed that infection occurs at, or shortly after, birth.

In the case of infected animals over 18 months of age, the combination of the choice of tissue sampled, genotype, age at testing and the accuracy of sampling will all have an effect on the ability of the screening test to detect an infected animal under field conditions. Consistent and accurate sampling of target areas is essential to give confidence in a negative biochemical result. The accuracy of sampling is also critical in the brainstem, as in the brainstem PrPSc is initially localised to the dorsal nucleus of the vagus nerve, before becoming more widely disseminated as infected animals develop clinical disease (Ryder et al., 2001, 2009; Sisó et al., 2010). Moving away from the target areas at the obex in cattle has also been resulted in a drop in detectable PrPSc (by a factor of 3 over 6 mm), potentially compromising detection (Moynagh et al., 1999).

Although the impact of this initially localised PrPSc deposition on test sensitivity in preclinical populations under field conditions has not been systematically assessed in sheep, there are several reports of studies in which whole goat herds have been culled and test performance compared. These all concur that, when PrPSc accumulation within the brainstem is restricted, sensitivity under field conditions is compromised, with different estimates reported in the literature: 47% (Corbière et al., 2013), 53% (González et al., 2010) and 64% (Ortiz‐Pelaez et al., 2014).

A further confounding issue when considering diagnostic screening test performance in goats is that the formal test evaluations that were undertaken in respect of small ruminant testing were conducted using only sheep scrapie samples. It has been shown subsequently that not all tests perform equally in all genotypes of goats (Papasavva‐Stylianou et al., 2017; Konold et al., 2020; Simmons et al., 2020). Not all caprine PRNP polymorphisms are synonymous with ovine ones, and some caprine polymorphisms coincide with particular diagnostic antibody‐binding sites, reducing the sensitivity of individual tests in certain animals. The actual (as opposed to assumed) overall sensitivity of a testing regime would therefore need to consider the genotypes of every screened animal in conjunction with the specific diagnostic screening test being used.

Under field conditions, the sensitivity of a test is likely to be lower than analytical sensitivity estimates obtained under laboratory conditions. Currently, there are no data to quantify at EU level the overall diagnostic sensitivity of diagnostic screening tests for the detection of CS in small ruminants above 18 months of age under field conditions.

Given the above, the following approach is used for the parameterisation of the diagnostic screening test sensitivity TSe:

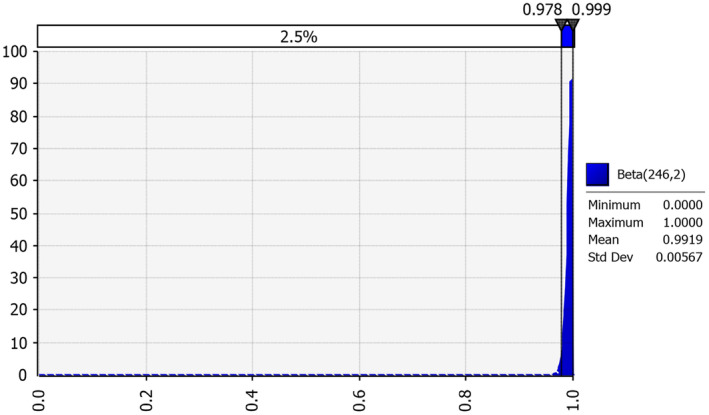

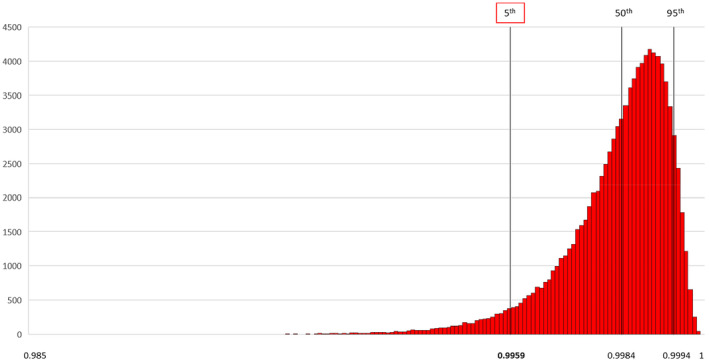

From the results of the past EU evaluations of diagnostic screening tests, the lowest value of diagnostic sensitivity obtained with the tests evaluated was selected as the worst case and applied to each MS. A beta distribution was built using 245 successes out of 246 trials (Figure 2), which corresponds to a TSe of 99.6% (95% CI: 98.80–100) (see Appendix B).

Alternative scenarios using different sensitivity values of the diagnostic screening tests, i.e. 90%, 80%, 70%, 60% and 50%, were applied to reflect the uncertainty of the actual sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests in field conditions.

Figure 2.

Probability distribution of the sensitivity of the diagnostic screening test using the results of the EU evaluation reports

2.2.3.3. Relative risk by species (alpha)

This risk indicator contains two risk categories, namely, sheep/goats.

A preliminary estimation of the specific prevalence of CS by country, year, species and stream has been obtained using the data described in Section 2.1.2.

The excess probability (relative risk) of detecting scrapie in sheep compared with goats was based on the calculation of the prevalence ratio (PR), i.e. the ratio of the prevalence observed in the first group (sheep) to that in the second declared as baseline (goats). Annual data for each country were used as the unit of analysis. A further restriction was applied, excluding country‐ and year‐specific data when the total number of tested animals in a particular country and year was less than 385, to prevent the possibility that sampling errors > 5% might affect the prevalence estimates used in each calculation.

The outcome of interest was the number of cases of CS reported by each country in the frame of active surveillance, whereas the total annual number of tested animals was used as an offset of the model. The following independent variables have been included in the model: country, species, year and surveillance group. Country was included as a random effect. The exponentiated coefficient of the final model represents the PR of detecting CS in the sheep compared with the baseline category (goats), taking into account the effect of country, group and year for the entire EU, for the period 2009–2021, under the testing conditions applied by each country in compliance with the EU legislation. The estimation of the relative risk sheep/goats was extracted from a multilevel negative binomial regression model.

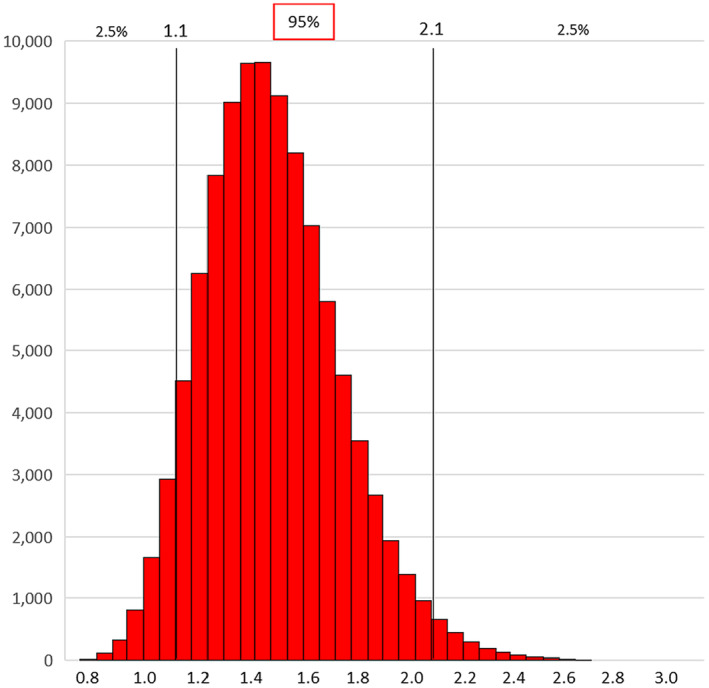

The results of the final model included 334 observations and showed a risk 1.5 times higher (95% CI 1.1–2.1) in sheep than in goats. Therefore, in summary,

the coefficient and associated standard error of the variable ‘species’ in the final multilevel negative binomial regression model were, respectively, 0.409 and 0.171. The corresponding PR was 1.5 (95% CI 1.1–2.1). A normal distribution matching the results obtained with the multilevel negative binomial regression model was used.

The resulting distribution (Figure 3) matched the results obtained with the multilevel negative binomial regression model i.e. a risk 1.5 times higher in sheep than in goats with a 2.5% probability for values < 1.1 and a 2.5% probability for values > 2.1.

Figure 3.

Frequency distribution of the values of the relative risk sheep/goats (α) based on 100,000 iterations

2.2.3.4. Relative risk by surveillance stream (beta)

This risk indicator contains two risk categories, namely, not slaughtered for human consumption (NSHC)/slaughtered for human consumption (SHC).

A similar approach was used to calculate the excess probability (relative risk) of detecting scrapie in the NSHC stream compared with the SHC stream.

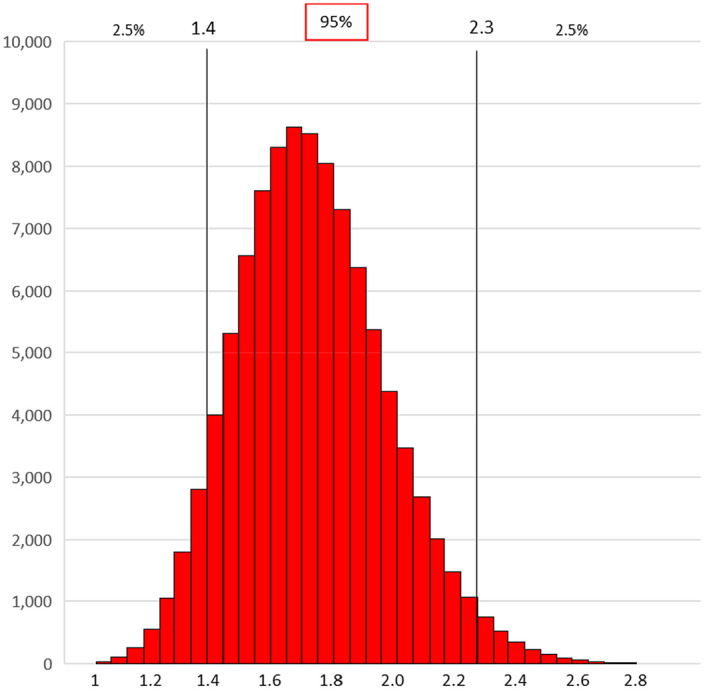

The estimation of the relative risk NSHC/SHC was conducted by fitting a multilevel negative binomial regression. The results of the final model included 334 observations and showed a risk 1.8 times higher (expressed as prevalence rate ratio) (95% CI 1.4–2.3) in the NSHC stream than in the SHC stream. Therefore, in summary,

the coefficient and associated standard error of the variable ‘surveillance group’ in the final multilevel negative binomial regression model were, respectively, 0.58554 and 0.1319. The corresponding PR was 1.8 (95% CI 1.4–2.3). A normal distribution matching the results obtained with the multilevel negative binomial regression model was used, i.e.

The resulting distribution (Figure 4) matched the results obtained with the multilevel negative binomial regression model i.e. a risk 1.8 times higher in the NSHC stream than in the SHC stream, with a 2.5% probability of values < 1.4 and a 2.5% probability of values > 2.3.

Figure 4.

Frequency distribution of the values of the relative risk NSHC/SHC (β) based on 100,000 iterations

Summary of the distribution of risk groups using two indicators for the estimation of SSe for CS

Table 2 presents the parameterisation of Table 1 for the estimation of SSe for CS each year. The parameter estimates described above are inserted in Equations (1, 2, 4 and 5) of the scenario‐tree model. Alpha (α) refers to the first risk factor (species) and beta (β) to the second (surveillance stream).

Table 2.

Actual distribution of risk groups using two risk indicators with two categories each and associated relative risks for classical scrapie according to the model

| Risk indicator I | Risk indicator II | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSHC | SHC | |||

| Sheep |

PopProp1 = N1/N |

PopProp2 = N2/N |

||

| Goats |

PopProp3 = N3/N |

PopProp4 = N4/N |

||

2.2.4. Country‐specific parameters for each MS

The model described in Section 2.2.2 is parameterised for each year under consideration, i.e. 2015–2022 and also for future years.

Sheep and goat populations within each surveillance stream (Ni)

The population of sheep and goats will vary between years. The differences in the sheep and goat populations within each surveillance stream are taken into account in the model described in Section 2.2.2. Using the notation described earlier,

N1 = Total NSHC sheep per year.

N2 = Total SHC sheep per year.

N3 = Total NSHC goats per year.

N4 = Total SHC goats per year.

Total population of sheep and goats per year.

The values for Ni used in the analysis are provided in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of test and population data by surveillance stream (2015–2022) and expected number of sheep and goats to be tested annually in the future by the Czech Republic

| Year | Total NSHC sheep (N1) | Total NSHC sheep tested (n1) | Total SHC sheep (N2) | Total SHC sheep tested (n2) | Total NSHC goats (N3) | Total NSHC goats tested (n3) | Total SHC goats (N4) | Total SHC goats tested (n4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 3,685 | 2,444 | 21,015 | 373 | 491 | 312 | 3,291 | 9 |

| 2016 | 3,881 | 2,846 | 23,759 | 28 | 617 | 416 | 3,869 | 0 |

| 2017 | 4,319 | 3,320 | 23,499 | 55 | 677 | 546 | 3,800 | 0 |

| 2018 | 3,897 | 2,918 | 24,818 | 3 | 717 | 449 | 4,531 | 0 |

| 2019 | 3,852 | 2,374 | 24,215 | 0 | 821 | 705 | 4,787 | 1 |

| 2020 | 3,317 | 2,382 | 22,134 | 14 | 906 | 735 | 4,512 | 0 |

| 2021 | 3,497 | 1,969 | 19,974 | 0 | 878 | 671 | 4,279 | 0 |

| 2022 (a) | 3,514 | 1,874 | 17,413 | 1 | 991 | 713 | 4,783 | 0 |

| Future (b) | 3,514 | 2,500 | 17,413 | 0 | 991 | 700 | 4,783 | 0 |

: 2022 is not included in the 7 years of data submitted in support of this application. It is neither ‘the future’ because testing has already occurred, and full data are available.

: Specific population size data are not available for future years, so it has been assumed that it will not change, and 2022 data have been carried forward. The projected number of animals to be tested has been taken from the additional detail supplied upon request by the Czech Republic (Jelínková, 2023).

Number of sheep and goats tested within each surveillance stream (ni)

Finally, the number of sheep and goats tested within each surveillance stream (NSHC, SHC) are defined as:

n1 = number of NSHC sheep tested per year.

n2 = number of SHC sheep tested per year.

n3 = number of NSHC goats tested per year.

n4 = number of SHC goats tested per year.

The values for ni used in the analysis are provided in Table 2.

Upon request to the Czech Republic (see Section 2.1.1) on how the 3,000 stated in the application will be split in future years between sheep and goats and the two surveillance groups, the competent authority of the Czech Republic stated that they plan to test 2,500 sheep in the NSHC and 700 in the goats NSHC (included in Table 3), exceeding the original proposed sample size of 3,000 (Jelínková, 2023).

2.2.5. Interpretation of the results of the model

For every iteration, the model produces for each year and diagnostic sensitivity value one overall surveillance sensitivity (SSe) value. Out of 100,000 iterations, the algorithm builds a distribution. The 5th percentile of the distribution is presented in the results (Table 4) as the value at which there is a 95% confidence of having a SSe equal or above that value.

Table 4.

Results of the estimation of the sensitivity of the surveillance system (SSe) of the Czech Republic, for the period 2015–2022 and proposed future surveillance for different values of diagnostic sensitivity

| Year/Diagnostic sensitivity | EU evaluation | 90% | 80% | 70% | 60% | 50% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 0.9984 | 0.9959 | 0.9898 | 0.9776 | 0.9551 | 0.9156 (a) |

| 2016 | 0.9996 | 0.9986 | 0.9954 | 0.9875 | 0.9708 | 0.9383 (a) |

| 2017 | 0.9999 | 0.9997 | 0.9986 | 0.995 | 0.9857 | 0.9641 |

| 2018 | 0.9997 | 0.9989 | 0.9963 | 0.9895 | 0.9744 | 0.9442 (a) |

| 2019 | 0.9988 | 0.9965 | 0.9908 | 0.9789 | 0.9565 | 0.917 (a) |

| 2020 | 0.9994 | 0.9979 | 0.9935 | 0.9834 | 0.9631 | 0.9257 (a) |

| 2021 | 0.995 | 0.9893 | 0.9779 | 0.9579 | 0.9252 (a) | 0.8739 (a) |

| 2022 | 0.9934 | 0.9868 | 0.9741 | 0.9527 | 0.9184 (a) | 0.8654 (a) |

| Future | 0.9994 | 0.9979 | 0.9938 | 0.9845 | 0.9654 | 0.9298 (a) |

: Values lower than 0.95.

As an example, for the combination of 90% diagnostic test sensitivity and 2015, the value 0.9959 presented in Table 4 means that in 95% of the iterations, the output SSe (overall sensitivity) is equal to or above 0.9959 (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Example of a frequency distribution of one output of the scenario‐tree model

As agreed in previous evaluations and for consistency purposes, given DP (0.1%), N and n, for each combination of year and test sensitivity, the 95% confidence level of detecting CS was considered achieved when the SSe was 95% or greater at the 5th percentile of the output distribution of the model.

3. Results of the assessment

The summary of the estimation of the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system (i.e. the level of confidence of disease detection mentioned in the ToR) in the Czech Republic for the different scenarios using historical and future surveillance data is shown in Table 4.

Estimated values of the surveillance system (SSe) of the Czech Republic (corresponding to the level of confidence of disease detection) are expressed as the 5th percentile of the output distribution of the scenario‐tree model of 100,000 iterations, obtained for each combination of year (2015–2022 and future surveillance) and values of diagnostic sensitivity. The model also accounts for RR parameters using surveillance data for the period 2009–2021.

4. Conclusions

4.1. General considerations

The purpose of this report is to apply an epidemiologically sound methodology in a transparent manner so that repeatable results can continue to be produced when applying the same method/s and data as used in previous similar assessments, ensuring consistency and continuity with the approach followed in previous evaluations. The parameterisation of variables of the models has been explained and justified accordingly.

It is acknowledged that different approaches to data analysis may produce different results. The application of representative versus risk‐based approaches, annual versus cumulative analysis of historic surveillance data, or deterministic versus stochastic, requires the use of different input parameters and assumptions specific for each.

The uncertainties about the key parameters for the assessment (the relative risks of sheep vs. goats and of NSHC vs. SHC) have been addressed by applying probability distributions, used in the context of a stochastic approach in order to estimate the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system. The uncertainty about the sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests has been addressed via scenario analysis.

The EFSA Working Groups producing these assessments considered that the existing laboratory data on the sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests from past EU test evaluations are not necessarily representative of the sensitivity under field conditions and may result in an overestimation of the overall surveillance sensitivity.

Given the uncertainty about the sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests, alternative scenarios were explored extending the range of values from the sensitivity provided by the EU evaluations to a range of sensitivities down to 50%, consistent with published data obtained under field conditions in infected goat populations.

The calculations of the sensitivity of the surveillance system (the level of confidence of disease detection mentioned in the ToR) have been made based on the assumption that the animals tested are representative of the populations from which the samples were drawn. The assessment of whether this assumption is tenable is beyond the scope of this mandate.

In the analysis of future surveillance, it has been assumed that the number of small ruminants tested will be as declared by the Czech Republic in the dossier or in further communications. If the actual number of tests was to be different, the results of the analysis with regard to future surveillance would not be valid and should be re‐calculated.

The regulatory requirements for active surveillance for scrapie in small ruminants in the EU and the minimum requirements for the recognition of the ‘negligible risk of classical scrapie status’ are different because they are not based on the same assumptions, hence compliance with the former does not mean automatic compliance with the latter.

4.2. Historical surveillance

The results of the estimation of the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system (i.e. the level of confidence of disease detection mentioned in the ToR) using scenario tree modelling with parameters as described in Sections 2.2.3 and 2.2.4, with data as in Table 3, and applying the criterion described in Section 2.2.5, reveal that:

Based on the test sensitivity derived from the EU test evaluation data and from any of the alternative scenarios, during the period 2015–2022, the Czech Republic has tested annually a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, sourced from the NSHC and SHC populations to ensure a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1% for all combinations except: 60% diagnostic sensitivity in 2021 and 2022, and 50% in 2015, 2016 and 2018–2022.

4.3. Future surveillance

The results of the estimation of the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system (i.e. the level of confidence of disease detection mentioned in the ToR) using scenario tree modelling with parameters as described in Sections 2.2.3 and 2.2.4, with data as in Table 3, and applying the criterion described in Section 2.2.5, reveal that:

Based on the expected number of samples claimed to be tested in 2023 and future years and on the test sensitivity derived from the EU test evaluation data and from any of the alternative scenarios, the Czech Republic proposes to test annually a sufficient number of ovine and caprine animals over 18 months of age, sourced from the NSHC and SHC, to provide a 95% level of confidence of detecting CS if it is present in that population at a prevalence rate exceeding 0.1% for all combinations except for the 50% test sensitivity scenario.

5. Recommendations

The sensitivity of the diagnostic screening tests in field conditions is a key parameter when estimating the overall sensitivity of the surveillance system. There is still a lack of data on the actual performance of the approved tests in field conditions, particularly for sheep. It would be advisable to generate such data.

Some of the parameters used in this assessment are dynamic. Prior to the assessment of any subsequent application, parameters relating to risk factors and test sensitivity should be reviewed and, if necessary, updated.

6. Documentation provided to EFSA

Application for the recognition of the Czech Republic as a Member State with a negligible risk of classical scrapie. Ref. Ares(2022)8655055 – 13/12/2022.

Abbreviations

- AS

atypical scrapie

- BSE

bovine spongiform encephalopathy

- CI

confidence interval

- CNS

central nervous system

- CS

classical scrapie

- DP

design prevalence

- EM

eradication measures

- EPI

effective probability of infection

- FAO

Food and Agriculture Organization

- GSe

group sensitivity

- IRMM

Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements

- LRS

lymphoreticular system

- MS

Member State

- NSHC

not slaughtered for human consumption

- PR

prevalence ratio

- PrP

prion protein

- PrPC

cellular prion protein

- PrPSc

abnormal isoform of the cellular prion protein

- RiBESS

risk‐based estimate of system sensitivity tool

- RSe

sensitivity of round of testing

- SHC

slaughtered for human consumption

- SSe

overall sensitivity of the surveillance system

- ToR

terms of reference

- TSe

test sensitivity

- TSE

transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

- WG

working group

- WOAH

World Organisation for Animal Health

- WR

weighted risk

Appendix A – Historical scrapie surveillance data 2009–2021

1.

Tables A.1 and A.2 show the distribution of animals tested and cases by country and species (Table A.1) and surveillance stream (Table A.2).

Appendix B – Results of the evaluation of post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests (rapid tests) for detection of TSE in small ruminants

1.

Table B.1 shows a summary of the results of the different evaluations of post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests (rapid tests) for the detection of TSE in small ruminants.

Table B.1.

Results of the EU evaluation of post‐mortem diagnostic screening tests (rapid tests) for the detection of TSE in small ruminants (sources: EFSA, 2005a,b; IRMM, 2005a,b,c, 2010; EFSA BIOHAZ Panel, 2012)

| Rapid test | Diagnostic sensitivity (%) | Number of positive brainstem samples tested | 95% CI (%) | Rapid test still approved (yes/no) | IRMM report on the evaluation | EFSA report/opinion on the evaluation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prionics Check PrioSTRIP SR (Visual protocol) | 100.00 | 199 | 98.11 | 100 | Yes | IRMM (2010) | EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (2012) |

| 100.00 | 50 (autolysed) | 92.87 | 100 | ||||

| Bio‐Rad TeSeE | 99.60 | 246 | 98.10 | 99.99 | Yes | IRMM (2005a) | EFSA (2005a) |

| Bio‐Rad TeSeE Sheep/Goat | 100.00 | 246 | 98.80 | 100 | Yes | IRMM (2005a) | EFSA (2005a) |

| Enfer | 100.00 | 246 | 98.80 | 100 | No (approved until end of 2010) | IRMM (2005a) | EFSA (2005a) |

| Institut Pourquier | 100.00 | 245 | 98.80 | 100 | No (approved until February 2009) | IRMM (2005a) | EFSA (2005a) |

| Prionics Check LIA SR | 100.00 | 246 | 98.80 | 100 | No (approved until end of 2010) | IRMM (2005a) | EFSA (2005a) |

| Prionics Check Western SR | 100.00 | 246 | 98.80 | 100 | No (approved until end of 2010) | IRMM (2005a) | EFSA (2005a) |

| IDEXX HerCheck BSE | 100.00 | 245 | 98.80 | 100 | Yes | IRMM (2005b) | EFSA (2005b) |

| Beckman Coulter's InProCDI | 100.00 | 246 | 98.80 | 100 | No (approved until February 2009) | IRMM (2005c) | EFSA (2005b) |

Suggested citation: EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , Di Piazza, G ., Lyytikäinen, T ., Ru, G ., Simmons, M ., & Ortiz‐Peláez, A . (2023). Evaluation of the application of the Czech Republic to be recognised as having a negligible risk of classical scrapie. EFSA Journal, 21(10), 24 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2023.8335

Requestor European Commission

Question numbers EFSA‐Q‐2023‐00059

Declarations of interest If you wish to access the declaration of interests of any expert contributing to an EFSA scientific assessment, please contact interestmanagement@efsa.europa.eu.

Acknowledgement EFSA wishes to thank its BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards) for endorsing this scientific report on 27 September 2023, and the members of the Working Group on negligible risk of classical scrapie: Giulio Di Piazza, Tapani Lyytikäinen, Angel Ortiz Peláez, Giuseppe Ru and Marion Simmons, for the preparatory work on this scientific output. EFSA wishes to acknowledge the Department of Animal Health Protection and Welfare of the State Veterinary Administration of Czech Republic that provided data for this scientific output.

EFSA may include images or other content for which it does not hold copyright. In such cases, EFSA indicates the copyright holder and users should seek permission to reproduce the content from the original source.

Adopted: 28 September 2023

Notes

Commission Decision 2000/374/EC of 27 December 2000 prohibiting the use of certain animal by‐products in animal feed. OJ L 6, 11.1.201, pp. 16–17.

Regulation (EC) No 1053/2003 of 19 June 2003 amending Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards rapid tests. OJ L 152, 20.6.203, pp. 8–9.

Regulation (EC) No 253/2006 of 14 February 2006 amending Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards rapid tests and measures for the eradication of TSEs in ovine and caprine animals. OJ L 44, 15.02.2006, pp. 9–12.

Regulation (EC) No 956/2010 of 22 October 2010 amending Annex X to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards the list of rapid tests. OJ L 279, 23.10.2010, pp. 10–12.

Regulation (EC) No 882/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on official controls performed to ensure the verification of compliance with feed and food law, animal health and animal welfare rules. OJ L 165, 30.4.2004, pp. 1–141.

References

- Cameron AR, 2012. The consequences of risk‐based surveillance: Developing output‐based standards for surveillance to demonstrate freedom from disease. Preventive veterinary medicine, 105(4), 280–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbière F, Chauvineau‐Perrin C, Lacroux C, Lugan S, Costes P, Thomas M, Brémaud I, Chartier C, Barillet F, Schelcher F and Andréoletti O, 2013. The limits of test‐based scrapie eradication programs in goats. PLoS One, 8(1), e54911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doherr MG and Audigé L, 2001. Monitoring and surveillance for rare health‐related events: a review from the veterinary perspective. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B Biological Sciences, 356, 1097–1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , 2005a. Scientific Report of the European Food Safety Authority on the Evaluation of Rapid post mortem TSE Tests intended for Small Ruminants. EFSA Journal 2005;3(6):31r, 17 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2005.31r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , 2005b. Scientific Report of the European Food Safety Authority on the Evaluation of Rapid post‐mortem TSE Tests intended for Small Ruminants. EFSA Journal 2005;3(10):49r, 16 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2005.49r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , 2012. A framework to substantiate absence of disease: the risk based estimate of system sensitivity tool (RiBESS) using data collated according to the EFSA Standard Sample Description – An example on Echinococcus multilocularis. EFSA supporting publications 2012:EN‐366, 44 pp. 10.2903/sp.efsa.2012.EN-366 [DOI]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , 2015a. Scientific report on the evaluation of the application of Sweden to be recognised as having a negligible risk of classical scrapie. EFSA Journal 2015;13(11):4292, 26 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , 2015b. Scientific report on the evaluation of the application of Denmark to be recognised as having a negligible risk of classical scrapie. EFSA Journal 2015;13(11):4294, 25 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) , 2015c. Scientific report on the evaluation of the application of Finland to be recognised as having a negligible risk of classical scrapie. EFSA Journal 2015;13(11):4293, 27 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2015.4293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards) , 2009. Scientific Opinion on Analytical sensitivity of approved TSE rapid tests. EFSA Journal 2009;7(12):1436, 175 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2009.1436 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards) , 2010. Scientific Opinion on BSE/TSE infectivity in small ruminant tissues. EFSA Journal 2010;8(12):1875, 92 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2010.1875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards) , 2012. Scientific Opinion on the evaluation of new TSE rapid tests submitted in the framework of the Commission Call for expression of interest 2007/S204‐247339. EFSA Journal 2012;10(5):2660, 32 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2012.2660 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- EFSA BIOHAZ Panel (EFSA Panel on Biological Hazards) , 2014. Scientific Opinion on the scrapie situation in the EU after 10 years of monitoring and control in sheep and goats. EFSA Journal 2014;12(7):3781, 155 pp. 10.2903/j.efsa.2014.3781 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations) , 2014. Risk‐based disease surveillance – A manual for veterinarians on the design and analysis of surveillance for demonstration of freedom from disease. FAO Animal Production and Health Manual No. 17, Rome, Italy. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/a-i4205e.pdf

- González L, Martin S, Hawkins SA, Goldmann W, Jeffrey M and Sisó S, 2010. Pathogenesis of natural goat scrapie: modulation by host PRNP genotype and effect of co‐existent conditions. Veterinary Research, 41, 48. 10.1051/vetres/2010020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRMM (Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements) , 2005a. The evaluation of rapid post mortem tests for the diagnosis of TSE in sheep. 16 June 2004. European Commission, Directorate‐General Joint Research Centre, Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements.

- IRMM (Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements) , 2005b. Report on the IDEXX HerdCheck® BSE rapid post‐mortem test in the EU scrapie test evaluation 2005. European Commission, Directorate‐General Joint Research Centre, Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements.

- IRMM (Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements) , 2005c. Report on Beckman Coulter’s ‘InPro CDITM’ rapid post-mortem test (version 2) in the EU scrapie test evaluation 2005. European Commission, Directorate-General Joint Research Centre, Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements.

- IRMM (Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements) , 2010. Report on the Prionics®‐Check PrioSTRIP SR Prionics AG. August 2010. European Commission, Directorate‐General Joint Research Centre, Institute for Reference Materials and Measurements.

- ISO (International Organization for Standardization) , 2005. ISO/IEC 17025:2005. General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories, 28 pp.

- Jelínková K, 2023. EFSA mandate CZ application negligible risk classical scrapie. Message to Angel Ortiz Pelaez. 5 May 2023.

- Konold T, Spiropoulos J, Thorne J, Phelan L, Fothergill L, Rajanayagam B, Floyd T, Vidana B, Charnley J, Coates N and Simmons M, 2020. The scrapie prevalence in a goat herd is underestimated by using a rapid diagnostic test. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology, 8, 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PAJ and Cameron A, 2003. Documenting freedom from avian. influenza. In: Report on International EpiLab project 4, Copenhagen, 2003.

- Martin PAJ, Cameron AR and Greiner M, 2007. Demonstrating freedom from disease using multiple complex data sources. 1. A new methodology based on scenario trees. Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 79, 71–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moynagh J, Schimmel H and Kramer GN, 1999. The evaluation of tests for the diagnosis of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy in bovines. In Consumer Policy and Consumer Health Protection. General Directorate XXIV. Preliminary report by the European Commission. Scientific health opinions: Directorate B.

- Ortiz‐Pelaez A, Georgiadou S, Simmons MM, Windl O, Dawson M, Arnold ME, Neocleous P and Papasavva‐Stylianou P, 2014. Allelic variants at codon 146 in the PRNP gene show significant differences in the risk for natural scrapie in Cypriot goats. Epidemiology and Infection, 143, 1304–1310. 10.1017/S0950268814002064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papasavva‐Stylianou P, Simmons MM, Ortiz‐Pelaez A, Windl O, Spiropoulos J and Georgiadou S, 2017. Effect of polymorphisms at codon 146 of the goat PRNP gene on susceptibility to challenge with classical scrapie by different routes. Journal of Virology, 91(22), e01142‐17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team , 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical ## computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Ryder SJ, Dexter GE, Heasman L, Warner R and Moore SJ, 2009. Accumulation and dissemination of prion protein in experimental sheep scrapie in the natural host. BMC Veterinary Research, 5, 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryder SJ, Spencer YI, Bellerby PJ and March SA, 2001. Immunohistochemical detection of PrP in the medulla oblongata of sheep: the spectrum of staining in normal and scrapie‐affected sheep. Veterinary Record, 148, 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons MM, Thorne L, Ortiz‐Pelaez A, Spiropoulos J, Georgiadou S, Papasavva‐Stylianou P, Andreoletti O, Hawkins SAC, Meloni D and Cassar C, 2020. Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy in goats: is PrP rapid test sensitivity affected by genotype? Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation, 32(1), 87–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisó S, González L and Jeffrey M, 2010. Neuroinvasion in prion diseases: the roles of ascending neural infection and blood dissemination. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases, 2010, 747892. 10.1155/2010/747892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stärk KDC, Regula G, Hernandez J, Knopf L, Fuchs K, Morris RS and Davies P, 2006. Concepts for risk‐based surveillance in the field of veterinary medicine and veterinary public health: review of current approaches. BMC Health Services Research, 6, 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]