This cohort study compares incidence and causes of sudden death by autopsy among housed and unhoused individuals in San Francisco County, California.

Key Points

Question

How is housing status associated with rates and causes of sudden death by autopsy in San Francisco County?

Findings

In this 8-year cohort study of 868 adult sudden deaths presumed cardiac by World Health Organization criteria (including 151 unhoused individuals [17%]), the sudden mortality rate was 16-fold higher in unhoused vs housed individuals. Noncardiac causes including occult overdose were more common, yet after excluding noncardiac causes, the arrhythmic death rate remained over 7-fold higher in the unhoused population.

Meaning

Homelessness is associated with significantly greater risk of sudden death from both noncardiac causes and arrhythmic causes potentially preventable with a defibrillator.

Abstract

Importance

Over 580 000 people in the US experience homelessness, with one of the largest concentrations residing in San Francisco, California. Unhoused individuals have a life expectancy of approximately 50 years, yet how sudden death contributes to this early mortality is unknown.

Objective

To compare incidence and causes of sudden death by autopsy among housed and unhoused individuals in San Francisco County.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used data from the Postmortem Systematic Investigation of Sudden Cardiac Death (POST SCD) study, a prospective cohort of consecutive out-of-hospital cardiac arrest deaths countywide among individuals aged 18 to 90 years. Cases meeting World Health Organization criteria for presumed SCD underwent autopsy, toxicologic analysis, and medical record review. For rate calculations, all 525 incident SCDs in the initial cohort were used (February 1, 2011, to March 1, 2014). For analysis of causes, 343 SCDs (incident cases approximately every third day) were added from the extended cohort (March 1, 2014, to December 16, 2018). Data analysis was performed from July 1, 2022, to July 1, 2023.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The main outcomes were incidence and causes of presumed SCD by housing status. Causes of sudden death were adjudicated as arrhythmic (potentially rescuable with implantable cardioverter-defibrillator), cardiac nonarrhythmic (eg, tamponade), or noncardiac (eg, overdose).

Results

A total of 868 presumed SCDs over 8 years were identified: 151 unhoused individuals (17.4%) and 717 housed individuals (82.6%). Unhoused individuals compared with housed individuals were younger (mean [SD] age, 56.7 [0.8] vs 61.0 [0.5] years, respectively) and more often male (132 [87.4%] vs 499 [69.6%]), with statistically significant racial differences. Paramedic response times were similar (mean [SD] time to arrival, unhoused individuals: 5.6 [0.4] minutes; housed individuals: 5.6 [0.2] minutes; P = .99), while proportion of witnessed sudden deaths was lower among unhoused individuals compared with housed individuals (27 [18.0%] vs 184 [25.7%], respectively, P = .04). Unhoused individuals had higher rates of sudden death (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 16.2; 95% CI, 5.1-51.2; P < .001) and arrhythmic death (IRR, 7.2; 95% CI, 1.3-40.1; P = .02). These associations remained statistically significant after adjustment for differences in age and sex. Noncardiac causes (96 [63.6%] vs 270 [37.7%], P < .001), including occult overdose (48 [31.8%] vs 90 [12.6%], P < .001), gastrointestinal causes (8 [5.3%] vs 15 [2.1%], P = .03), and infection (11 [7.3%] vs 20 [2.8%], P = .01), were more common among sudden deaths in unhoused individuals. A lower proportion of sudden deaths in unhoused individuals were due to arrhythmic causes (48 of 151 [31.8%] vs 420 of 717 [58.6%], P < .001), including acute and chronic coronary disease.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study among individuals who experienced sudden death in San Francisco County, homelessness was associated with greater risk of sudden death from both noncardiac causes and arrhythmic causes potentially preventable with a defibrillator.

Introduction

Over 580 000 individuals in the US experience homelessness annually.1 Unhoused individuals have limited access to food and safety, which negatively influence health and lead to high burden of disease.2 These factors culminate in a mortality rate that is up to 9-fold higher among unhoused individuals, most commonly from heart disease and drug overdose.3,4,5 While mean age at death in unhoused individuals is around 50 years, how sudden cardiac death (SCD) contributes to this early mortality is unknown.6 As in the general population, identifying the burden of SCD in the unhoused population is critical to guide public health interventions and because some of these deaths may have been preventable with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) or automatic external defibrillator.

A common challenge in SCD studies is that the cause of death is nearly always adjudicated without postmortem data and therefore presumes cardiac cause.7 Sudden cardiac death has been historically defined by consensus criteria, including those from the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society and the World Health Organization (WHO).8,9 These criteria define SCD as a sudden unexpected death occurring within 1 hour of symptom onset or within 24 hours of having been observed alive and symptom free and are intended to capture patients who die of sudden arrhythmic death (SAD), the only type of sudden death rescuable by ICDs or automatic external defibrillators. However, using only medical or paramedic records and death certificates leads to misclassification of noncardiac causes (eg, occult overdose, intracranial hemorrhage, and pulmonary embolism) or nonarrhythmic causes (eg, cardiac tamponade) of sudden death as SCD.10 In the ongoing, prospective San Francisco Postmortem Systematic Investigation of Sudden Cardiac Death (POST SCD) study, over half of all presumed SCDs as defined by WHO criteria were found to have a nonarrhythmic cause of death on autopsy.11

Determining the incidence and underlying causes of SCD in unhoused individuals is essential to inform potential public health interventions and policies targeted at improving health in this vulnerable population. We therefore leveraged the POST SCD study to determine rates and causes of presumed SCD in unhoused and housed populations of San Francisco County, California. Given the unique health challenges experienced by the unhoused population, we hypothesized that unhoused individuals would experience a higher rate of both overall sudden death and autopsy-defined arrhythmic death, with different underlying causes as compared with the housed population.

Methods

The University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board approved this study and granted a waiver of informed consent because all patients were deceased. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Additional approval was obtained from 10 San Francisco County hospitals and 3 emergency medical services (EMS) agencies.

Study Population and Definitions

Detailed methods and design of POST SCD have been previously described.11,12 Briefly, POST SCD is a prospective countywide autopsy study of consecutive out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) deaths attributed to WHO-defined SCD among adults aged 18 to 90 years in San Francisco County (2022 total population of 808 437 individuals, including 7754 unhoused individuals).13,14 The OHCAs were defined using Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival criteria.11 Deaths were excluded if the individual had a terminal illness, end-stage kidney disease and was receiving hemodialysis, an alternative identifiable noncardiac cause of sudden death before autopsy (eg, scene evidence of drug use or suicide), or admission within 30 days for noncardiac illness or surgical procedure. Ascertainment of race and ethnicity was made by review of autopsy, EMS, and medical records. The initial POST SCD cohort from February 1, 2011, to March 1, 2014, was designed to capture every incident SCD countywide and comprised 525 cases. During this period, every OHCA death reported to the medical examiner was included. In the extended cohort from March 1, 2014, to December 16, 2018, incident cases were included based on medical examiner (E.M.) call schedule (approximately every third day) and included an additional 343 cases.

Definition of Homelessness

Homelessness was determined by review of medical examiner and clinical records using the San Francisco Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing definition.15 This definition encompasses individuals who lack regular nighttime residence and individuals who live in supervised shelters, including welfare hotels, stabilization rooms, and shelters.

Postmortem Investigation and Adjudication of Sudden Deaths

Cases in the study underwent a comprehensive examination that included full autopsies (performed by forensic pathologist [E.M.]), toxicologic analysis (performed on deceased individuals aged ≤75 years, and those aged >75 years without obvious cause of death, eg, acute myocardial infarction), and medical record review. Cause of death was adjudicated by a multidisciplinary expert panel comprising cardiac electrophysiologists, the assistant medical examiner of San Francisco County, and a cardiac pathologist. Medical records were obtained by search of the electronic health record systems of the 10 San Francisco County hospitals included in the POST SCD study. If next of kin knew that medical care was received elsewhere, records were obtained by submitting a request to out-of-county institutions. Adjudication determined (1) whether the OHCA death met WHO criteria for SCD (hereafter, presumed SCD) based on medical and EMS records, (2) underlying cause of death by autopsy, and (3) whether the presumed SCD was due to arrhythmic cause potentially rescuable with ICD (hereafter, autopsy-defined SAD). Specifically, autopsy-defined SAD was presumed SCD for which no identifiable noncardiac cause or cardiac/nonarrhythmic cause was found on comprehensive postmortem investigation.

Premortem Medical Care

Access to care was confirmed if any hospital-based medical record was found for each individual, including prior testing, emergency department visit, clinic visit, or admission. We determined premortem diagnoses by presence of condition on medical record review. This definition did not capture individuals who received care exclusively at non–hospital-affiliated health sites, such as independent rehabilitation centers.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data from the initial and extended cohorts, from February 1, 2011, to December 16, 2018. The initial cohort (February 1, 2011, to March 1, 2014) was used for incidence calculations because all OHCA deaths in San Francisco County were captured during the initial study period, while the combined cohort was used for all other analyses.

Baseline characteristics are presented as means (SDs) or as numbers and percentages of those by housing status. We compared baseline characteristics and causes of presumed SCD using χ2 or Fisher exact tests for categorical variables and unequal-variance t tests for continuous variables.

We used data from countywide sources to calculate the estimated person-years at risk for housed and unhoused populations. For the unhoused population, data were available from the 2011 and 2013 San Francisco Homeless Point-in-Time Count and Survey Comprehensive Reports.15,16 These reports included total population and age distribution. Since no published data were available for 2012 and 2014, we used data from 2011 to estimate the 2012 population and data from 2013 to estimate the 2014 population. To maintain consistency, housed population counts from only 2011 and 2013 were used, and a similar approach of applying 2011 data to estimate the 2012 population and 2013 data to estimate the 2014 population was used. Total counts of the housed population were obtained from US Census Bureau (USCB).17 Age distribution of the housed San Francisco County population was estimated using 2010 USCB data.13 Person-years at risk was calculated as the sum of estimated person-years at risk in 2 different age groups as provided by census data from these government sources. Additional details of estimation of person-years and incident rates of death are in the eAppendix in Supplement 1.

Event rates for presumed SCD and SAD were estimated by the ratio of events to person-years at risk. We compared event rates by housing status using unadjusted Poisson regression models with robust standard errors, with numbers of events as the outcome and log-person years as an offset. Age and sex were added as control variables in their respective adjusted analyses, and together in a combined analysis.

In our age-adjusted analysis, we considered age a binary predictor with 2 categories: a younger and older group. Due to inconsistency in the cutoffs used to report the age distribution of unhoused and housed individuals in publicly available government data, we used a cutoff of age 61 years and older for the older unhoused population, and 65 years and older for the older housed population. Sex was obtained from the USCB data for the housed population and Point-in-Time Count and Survey Comprehensive Reports for the unhoused population.13,15,16 We performed an additional analysis adjusting for age and sex in a combined model that assumed sex distribution across age groups was identical. Stata, version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC), was used to perform all analyses, with 2-tailed P < .05 indicating significance.

Results

Characteristics of SCDs Among Unhoused and Housed Individuals

We identified 868 presumed SCDs over 8 years: 151 (17%) among unhoused individuals and 717 (83%) among housed individuals (Table 1). The mean (SD) EMS response times (5.6 [0.4] vs 5.6 [0.2] minutes, P = .99) were similar between unhoused and housed individuals. Initial EMS ventricular rhythm was less common in unhoused compared with housed individuals (3.3% vs 8.5%, P = .03), and unhoused individuals had a lower proportion of witnessed sudden deaths (18.0% vs 25.7%, P = .04). Unhoused individuals who experienced sudden deaths were younger (mean [SD] age, 56.7 [0.8] vs 61.0 [0.5] years), were more often male (87.4% vs 69.6%), and had significant racial differences, with fewer Asian individuals (2.0% vs 22.7%) and more Black individuals (25.8% vs 15.1%), than housed individuals who experienced sudden deaths. Unhoused individuals who experienced sudden deaths had a higher prevalence of premortem alcohol or substance use disorder and a higher prevalence of psychiatric conditions, specifically schizophrenia (15.2% vs 5.0%, P < .001), depression (22.5% vs 14.7%, P = .02), and bipolar disorder (7.3% vs 3.9%, P = .01). Among medications, unhoused individuals were more commonly prescribed selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (15.9% vs 8.0%, P = .002), antipsychotics (15.2% vs 7.4%, P = .002), and opioids (25.2% vs 14.9%, P = .002).

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of World Health Organization–Defined (Presumed) Sudden Cardiac Deaths in Unhoused Individuals Compared With Housed Individuals in San Francisco County, 2011-2018.

| Characteristic | Individuals, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unhoused (n = 151) | Housed (n = 717) | ||

| Age, mean (SD), y | 56.7 (0.8) | 61.0 (0.5) | <.001 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 19 (12.6) | 218 (30.4) | <.001 |

| Male | 132 (87.4) | 499 (69.6) | |

| Race and ethnicity | |||

| Asian | 3 (2.0) | 163 (22.7) | <.001 |

| Black | 39 (25.8) | 108 (15.1) | .001 |

| Hispanic | 15 (9.9) | 45 (6.3) | .11 |

| White | 90 (59.6) | 380 (53.0) | .14 |

| Othera | 4 (2.7) | 21 (2.9) | .85 |

| Witnessed death | 27 (18.0) | 184 (25.7) | .04 |

| Initial rhythm | |||

| Asystole | 124 (82.1) | 551 (76.8) | .16 |

| PEA | 6 (4.0) | 21 (2.9) | .50 |

| VT/VF | 5 (3.3) | 61 (8.5) | .03 |

| Other | 5 (3.3) | 19 (2.6) | .65 |

| Missing | 11 (7.3) | 65 (9.1) | 48 |

| Time to EMS arrival, mean (SD), min | 5.6 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.2) | .99 |

| Prior ICD implantation | 0 | 7 (1.0) | .22 |

| Prior medical care | 130 (86.1) | 597 (83.3) | .39 |

| Premortem diagnoses | |||

| Hypertension | 68 (45.0) | 372 (51.9) | .13 |

| Diabetes | 27 (17.9) | 154 (21.5) | .32 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 19 (12.6) | 214 (30.0) | <.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 12 (8.0) | 125 (17.4) | .004 |

| Heart failure/cardiomyopathy | 17 (11.3) | 93 (13.0) | .57 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (4.6) | 62 (8.7) | .10 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 9 (6.0) | 70 (9.8) | .14 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 6 (4.0) | 38 (5.3) | .50 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 27 (17.9) | 66 (9.2) | .002 |

| Psychiatric diagnosis | |||

| Schizophrenia | 23 (15.2) | 36 (5.0) | <.001 |

| Depression | 34 (22.5) | 105 (14.7) | .02 |

| Anxiety | 10 (6.6) | 44 (6.1) | .82 |

| Bipolar disorder | 11 (7.3) | 19 (2.6) | .01 |

| Chronic hepatitis C infection | 34 (22.5) | 28 (3.9) | <.001 |

| HIV/AIDS | 17 (11.3) | 40 (5.6) | .01 |

| Tobacco use | 72 (47.7) | 252 (35.2) | .004 |

| Excess alcohol use | 83 (55.0) | 137 (19.1) | <.001 |

| Illicit drug use | 62 (41.1) | 87 (12.1) | <.001 |

| Medications | |||

| Aspirin | 32 (21.2) | 176 (24.6) | .38 |

| Statin | 20 (13.3) | 194 (27.1) | <.001 |

| ACEI | 30 (19.9) | 176 (24.6) | .22 |

| ARB | 4 (2.7) | 55 (7.7) | .03 |

| β-Blocker | 31 (20.5) | 192 (26.8) | .11 |

| Calcium channel blocker | 15 (9.9) | 105 (14.6) | .13 |

| Antiarrhythmic | 12 (8.0) | 49 (6.8) | .63 |

| Diuretic | 29 (19.2) | 173 (24.1) | .19 |

| Nitrate | 7 (4.6) | 55 (7.7) | .19 |

| SSRI | 24 (15.9) | 57 (8.0) | .002 |

| Antipsychotic | 23 (15.2) | 53 (7.4) | .002 |

| Opioid | 38 (25.2) | 107 (14.9) | .002 |

Abbreviations: ACEI, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker; EMS, emergency medical services; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; PEA, pulseless electrical activity; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor; VT/VF, ventricular tachycardia/ventricular fibrillation.

Per entry of data collection in the Postmortem Systematic Investigation of Sudden Cardiac Death study, if individuals did not meet other race and ethnicity categories (ie, Asian, Black, Hispanic, or White), they were classified as other.

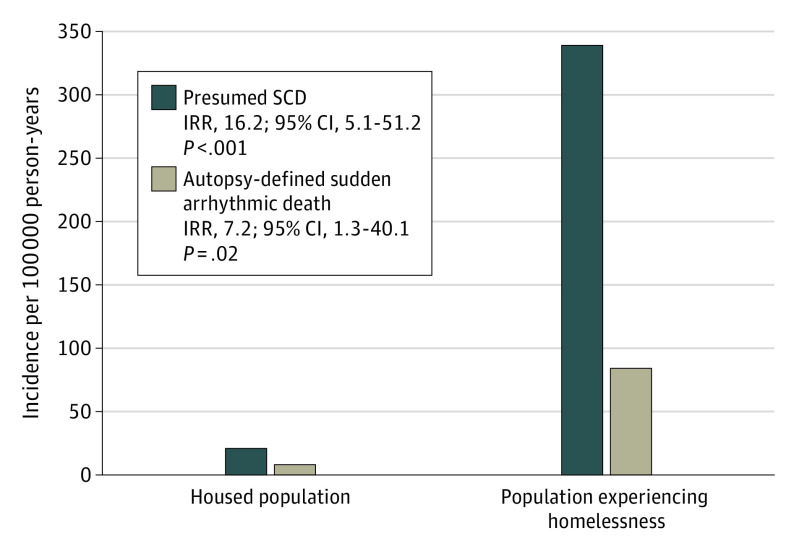

Incidence of Presumed SCD and Autopsy-Defined SAD

Unadjusted 3-year incidence rates for presumed SCD were 341 vs 21 per 100 000 person-years (incidence rate ratio [IRR], 16.2; 95% CI, 5.1-51.2; P < .001) in unhoused vs housed individuals, and 91 vs 13 per 100 000 person-years (IRR, 7.2, 95% CI, 1.3-40.1; P = .02) for SAD. Adjusted for age and sex differences, the IRR for presumed SCD in the unhoused vs housed population was 22.9 (95% CI, 9.1-57.3), P < .001, and 14.5 (95% CI, 4.8-43.5), P < .001, respectively. Age- and sex-adjusted IRR for SAD in the unhoused population vs housed population was 10.5 (95% CI, 2.3-47.3), P = .002, and 6.2 (95% CI, 1.1-33.4), P = .04, respectively (Figure 1, Table 2). In a combined model adjusted for age and sex, the IRR for presumed SCD was 20.1 (95% CI, 9.7-41.9), P < .001, and 8.7 for SAD (95% CI, 2.3-33.2), P = .002, in the unhoused vs housed population.

Figure 1. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) for Presumed Sudden Cardiac Death (SCD) and Autopsy-Defined Arrhythmic Death in Unhoused Individuals Compared With Housed Individuals in San Francisco County, 2011-2014.

Table 2. Incidence Rate Ratios (IRRs) for Presumed Sudden Cardiac Death and Autopsy-Defined Arrhythmic Death in Unhoused Individuals Compared With Housed Individuals in San Francisco County, 2011-2014.

| Analysis/outcome | IRR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | ||

| SCD | 16.2 (5.1-51.2) | <.001 |

| SAD | 7.2 (1.3-40.1) | .02 |

| Age adjusted | ||

| SCD | 22.9 (9.1-57.3) | <.001 |

| SAD | 10.5 (2.3-47.3) | .002 |

| Sex adjusted | ||

| SCD | 14.5 (4.8-43.5) | <.001 |

| SAD | 6.2 (1.1-33.4) | .04 |

| Age and sex adjusted | ||

| SCD | 20.1 (9.7-41.9) | <.001 |

| SAD | 8.7 (2.3-33.2) | .002 |

Abbreviations: SAD, sudden arrhythmic death; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

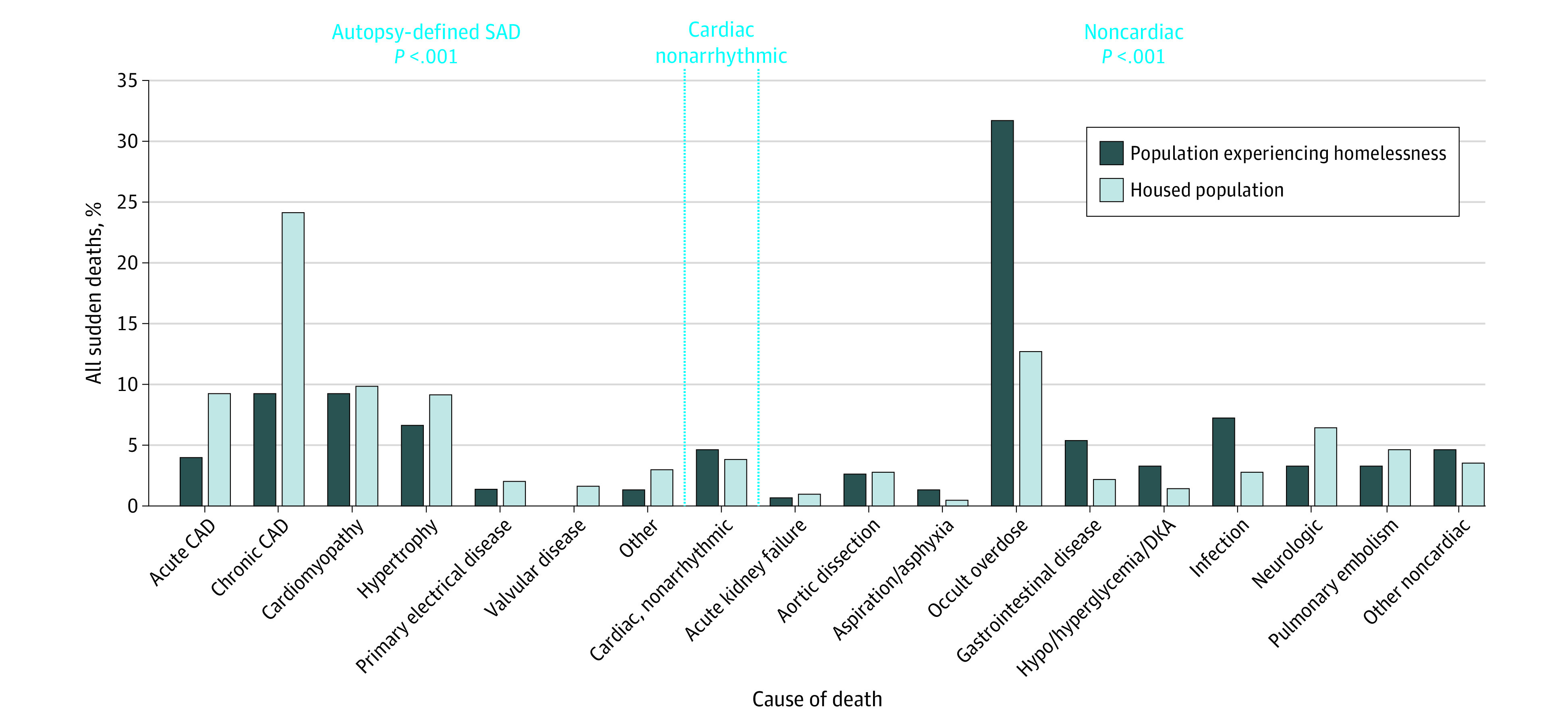

Causes of Sudden Death by Autopsy

Sudden deaths among unhoused individuals had higher proportions of noncardiac causes (63.6% vs 37.7%), including occult overdose (31.8% vs 12.6%), gastrointestinal causes (5.3% vs 2.1%), and infection (7.3% vs 2.8%, all P < .05, Figure 2, Table 3). In both unhoused and housed populations, approximately half of occult overdoses discovered by postmortem toxicologic analysis involved multiple drugs (47.9% vs 58.9%, P = .22). Proportion of sudden death due to occult overdose among unhoused individuals was similar by age group. Among infection causes of sudden death, we found higher proportions of peritonitis (2.6% vs 0.4%) and cystitis/pyelonephritis (1.3% vs 0.1%) in unhoused individuals (all P < .05).

Figure 2. Causes of Sudden Death by Autopsy in Unhoused Individuals Compared With Housed Individuals in San Francisco County, 2011-2018.

CAD indicates coronary artery disease; DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis; SAD, sudden arrhythmic death.

Table 3. Causes of Sudden Death by Autopsy in Unhoused Individuals Compared With Housed Individuals in San Francisco County, 2011-2018a.

| Cause of death | Individuals, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unhoused (n = 151) | Housed (n = 717) | ||

| Arrhythmic | 48 (31.8) | 420 (58.6) | <.001 |

| Acute coronary artery disease | 6 (4.0) | 66 (9.2) | .03 |

| Chronic coronary artery disease | 14 (9.3) | 172 (24.0) | <.001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 14 (9.3) | 71 (9.9) | .81 |

| Cause | |||

| Drug or alcohol induced | 12 (7.9) | 26 (3.6) | .02 |

| Nonischemic/dilated/idiopathic | 2 (1.3) | 38 (5.3) | .02 |

| Amyloidosis | 0 | 2 (0.3) | .52 |

| Otherb | 0 | 5 (0.7) | .30 |

| Hypertrophy | 10 (6.6) | 65 (9.1) | .33 |

| Cause | |||

| Hypertensive heart disease | 7 (4.6) | 50 (7.0) | .29 |

| Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy | 1 (0.7) | 8 (1.1) | .63 |

| Unspecified | 2 (1.3) | 7 (1.0) | .70 |

| Primary electrical disease | 2 (1.3) | 14 (2.0) | .60 |

| Valvular disease | 0 | 11 (1.5) | .13 |

| Otherc | 2 (1.3) | 21 (2.9) | .27 |

| Cardiac, nonarrhythmic | 7 (4.6) | 27 (3.8) | .62 |

| Noncardiac | 96 (63.6) | 270 (37.7) | <.001 |

| Acute kidney failure | 1 (0.7) | 7 (1.0) | .71 |

| Aortic dissection | 4 (2.7) | 20 (2.8) | .92 |

| Aspiration/asphyxia | 2 (1.3) | 3 (0.4) | .18 |

| Occult overdose | 48 (31.8) | 90 (12.6) | <.001 |

| Culprit drugd | |||

| Cocaine | 11 (7.3) | 22 (3.1) | .01 |

| Alcohol | 20 (13.2) | 15 (2.1) | <.001 |

| Methamphetamine | 13 (8.6) | 20 (2.8) | .001 |

| Opioid | 10 (6.6) | 17 (2.4) | .006 |

| Opiate | 2 (1.3) | 28 (3.9) | .12 |

| Methadone | 7 (4.6) | 16 (2.2) | .10 |

| Benzodiazepine | 3 (2.0) | 14 (2.0) | .98 |

| Othere | 6 (4.0) | 14 (2.0) | .13 |

| Antidepressant/antipsychoticf | 3 (2.0) | 19 (2.6) | .64 |

| Gastrointestinal causes | 8 (5.3) | 15 (2.1) | .03 |

| Hypoglycemia/hyperglycemia/DKA | 5 (3.3) | 10 (1.4) | .10 |

| Infection | 11 (7.3) | 20 (2.8) | .01 |

| Type of infection | |||

| Peritonitis | 4 (2.6) | 3 (0.4) | .01 |

| Pneumonia | 5 (3.3) | 11 (1.5) | .14 |

| Cystitis/pyelonephritis | 2 (1.3) | 1 (0.1) | .02 |

| Meningitis | 0 | 1 (0.1) | .65 |

| Skin/soft tissue | 0 | 2 (0.3) | .52 |

| Otherg | 0 | 2 (0.3) | .52 |

| Neurologic | 5 (3.3) | 46 (6.4) | .14 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 5 (3.3) | 33 (4.6) | .48 |

| Other noncardiac | 7 (4.6) | 25 (3.5) | .50 |

Abbreviation: DKA, diabetic ketoacidosis.

Medical records were accessible for 860 of 867 individuals.

Other cardiomyopathy types in the housed group include arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia (n = 1), HIV-related cardiomyopathy (n = 1), mitral valve prolapse (n = 1), noncompaction cardiomyopathy (n = 1), and stress cardiomyopathy (n = 1).

Other causes of arrhythmic deaths include myocardial infarction without coronary artery disease (1 among unhoused individuals, 4 among housed individuals), healed myocardial infarction (1 among unhoused individuals, 9 among housed individuals), acquired long QT syndrome (1 among housed individuals), myocarditis (3 among housed individuals), and device failure or concern (4 among housed individuals).

Sum of all reported percentages exceed 100% because of instances in which polysubstance use contributed to overdose.

Other causes of overdose included diphenhydramine, phenobarbital, topiramate, trazadone, gabapentin, tramadol, zolpidem, and carisoprodol.

Antidepressants included serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, and atypical antidepressants.

Other causes of infection included 1 instance of meningitis and 1 instance of disseminated cryptococcus.

Conversely, presumed SCDs among unhoused individuals had lower proportions of arrhythmic causes (31.8% vs 58.6%, P < .001), specifically acute (4.0% vs 9.2%, P = .03) and chronic coronary artery disease (CAD; 9.3% vs 24.0%, P < .001). Chronic CAD and cardiomyopathy, specifically drug- or alcohol-induced cardiomyopathy, were the most common cause of SAD among unhoused individuals (Figure 2, Table 3).

Premortem Medical Care

Most individuals had access to medical care, with no differences by housing status (86.1% vs 83.3%, P = .39). A minority of individuals in both unhoused and housed populations had their underlying cause of sudden death diagnosed premortem (29.5% vs 36.6%, P = .35, eTable in Supplement 1). Only 1 unhoused individual who experienced SAD met established primary prevention criteria for ICD, with a known cardiomyopathy and ejection fraction of 25% despite optimal medical therapy. Thus, less than 1% of sudden deaths in the unhoused population (1 of 151) may have been prevented by current risk stratification criteria for arrhythmic death.

Discussion

In this 8-year countywide postmortem study of OHCA deaths, we found: (1) a 16-fold higher rate of sudden mortality among unhoused compared with housed individuals; (2) higher rates of noncardiac causes, including occult overdose, gastrointestinal, and infection causes in sudden deaths among individuals experiencing homelessness; (3) even excluding significantly higher rates of noncardiac causes, the rate of arrhythmic death potentially rescuable with defibrillators was 7-fold higher in the unhoused population; and (4) significant racial differences in the burden of sudden death. Unhoused individuals died most often from noncardiac causes, while housed individuals died more commonly from arrhythmic causes. Chronic conditions leading to arrhythmic death were rarely diagnosed premortem. These findings offer several novel insights into the profound implications of homelessness on sudden death and its underlying causes.

The unique design of POST SCD allowed us to compare precise incidence rates of sudden death by housing status. While the magnitude of increased risk of sudden death and arrhythmic death we found are remarkable, they are consistent with reported 9-fold higher overall mortality rates and 12-fold higher rates of overdose-related deaths among unhoused compared with housed individuals.3,4,18 We found that unhoused individuals were younger than housed individuals, and age-adjusted analysis yielded even higher rates of overall sudden death and SAD in the unhoused population than unadjusted analyses, pointing to heightened risk among younger unhoused individuals. These findings are consistent with paradoxically higher published mortality rates among younger compared with older unhoused individuals,3,4,15,16 and our data suggest that this is not due to higher overdose rates among unhoused youth. We also found that compared with housed individuals, unhoused individuals who experienced sudden death were more likely to be Black. This racial disparity is consistent with the recognized higher rates of homelessness among Black individuals compared with White individuals, including among those hospitalized for cardiovascular diseases, and demonstrates that these health disparities extend to sudden death among Black individuals.19

We found that unhoused individuals were more likely to have nonarrhythmic causes of sudden death compared with housed individuals, despite similar EMS response times. In particular, while the majority of deaths among unhoused individuals had noncardiac causes not rescuable with a defibrillator, including infection, gastrointestinal causes, and occult overdose, the majority of deaths among housed individuals had arrhythmic causes. While the high rate of substance use in the unhoused population has been long recognized,18,20 our study demonstrates its association with early, specifically sudden, mortality and its true impact among the unhoused population. By systematic toxicologic analysis, we found that occult overdose alone accounted for over 30% of presumed SCDs among unhoused individuals, similar to proportions among persons living with HIV and higher than in the general population.12,21 Among SADs attributable to cardiomyopathy in the unhoused population, notably nearly all were related to substance use, suggesting that the impact of substance use extends beyond noncardiac death and contributes to arrhythmic causes as well.

In contrast, housed individuals more closely reflected the classic profile of sudden death that modern medical systems aim to resuscitate and prevent. Acute and chronic CAD together accounted for nearly 30% of sudden deaths among housed individuals, but less than 15% of deaths among unhoused individuals. Consistent with these findings, hyperlipidemia and CAD were more likely premortem diagnoses made among housed individuals, who also experienced higher rates of ventricular arrhythmia on initial rhythm. This is consistent with lower prevalence of traditional atherosclerotic risk factors reported in the unhoused population.19,22 Coronary artery disease accounted for over 40% of arrhythmic deaths in unhoused individuals, but only 15% of these patients had a known diagnosis of CAD, reflecting the need for better screening and primordial prevention in this vulnerable population.

Our analyses demonstrate that SCD is an important cause of premature and excess death in the unhoused population and may help guide future public health interventions. Sudden cardiac death in the unhoused population has a profile distinct from the traditional population; therefore, specific resources targeting the underlying causes we identified may maximize the impact of prevention strategies for reducing early mortality. For example, increasing the availability of automatic external defibrillators in the unhoused population may reduce the significantly higher rates of arrhythmic death. Moreover, redoubled efforts to treat substance use, including safe prescribing patterns and naloxone distribution, may reduce both overdose rates and heart failure in the unhoused population, and targeted immunization efforts may reduce infection causes of sudden death. The higher prevalence of comorbid psychiatric conditions among unhoused individuals also suggests that further investments in psychiatric care for this vulnerable population may be especially important.

Limitations

San Francisco has the nation’s fourth highest overall rate of homelessness.23 The study sample was therefore enriched to meaningfully examine the association of homelessness with presumed SCD but may not reflect the unhoused population nationally or in other cities. Because age groups reported in the US Census Data between the housed and unhoused populations do not perfectly align, direct comparison of these age groups was not possible. However, the small difference in age cutoff of 4 years is unlikely to account for the large difference in IRRs that we identified. Similarly, lack of data on racial makeup by age group and housing status precluded race-adjusted analyses.

We carefully examined other possible sources of bias in our study, including the possibility that unhoused individuals might not seek or have access to medical attention as often as housed individuals. However, nearly all (88.2%) individuals previously sought care, with similar rates in housed and unhoused individuals. The proportion of witnessed sudden deaths was lower among unhoused individuals, which may have contributed to the lower burden of arrhythmic death we observed in this population. In the initial POST SCD cohort, only 16 (3%) families had declined autopsy,11 but housing status for these 16 individuals was not collected, so we could not determine whether autopsy rates were different in the 2 groups. However, the overall rate of autopsy was 97% in the initial study period; thus, differential rates of autopsy should not meaningfully affect our study findings.

Conclusions

Findings of this cohort study show that homelessness was associated with greater risk of sudden death from both noncardiac causes and arrhythmic causes potentially rescuable with a defibrillator. The disparities identified in this study underscore the profound adverse association of housing status with health and potentially preventable sudden mortality. Our precise identification of underlying causes suggests that excess sudden death in the unhoused population is most commonly due to occult overdose, substance use–related cardiomyopathy, chronic CAD, gastrointestinal causes, and infection. Future studies and policy may consider these findings when designing strategies to improve the care of unhoused individuals.

eTable. Proportion of Sudden Arrhythmic Deaths with Causes Known Premortem in Homeless vs. Housed Populations

eAppendix.

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Dept of Housing and Urban Development . HUD 2020 Continuum of Care homeless assistance programs homeless populations and subpopulations. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://files.hudexchange.info/reports/published/CoC_PopSub_NatlTerrDC_2020.pdf

- 2.National Health Care for the Homeless Council . Homelessness & health: what’s the connection? Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/phlp/publications/topic/resources/resources-homelessness.html#:~:text=Homelessness%20and%20Health,external%20icon

- 3.Baggett TP, Hwang SW, O’Connell JJ, et al. Mortality among homeless adults in Boston: shifts in causes of death over a 15-year period. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(3):189-195. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hibbs JR, Benner L, Klugman L, et al. Mortality in a cohort of homeless adults in Philadelphia. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(5):304-309. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408043310506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown RT, Evans JL, Valle K, Guzman D, Chen YH, Kushel MB. Factors associated with mortality among homeless older adults in California: the HOPE HOME study. JAMA Intern Med. 2022;182(10):1052-1060. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.3697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cawley CL, Kanzaria HK, Kushel M, Raven MC, Zevin B. Mortality among people experiencing homelessness in San Francisco 2016–2018. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(4):990-991. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06769-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tseng ZH. Sudden cardiac deaths—WHO says they are always arrhythmic? JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3(7):556-558. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . WHO scientific group on sudden cardiac death and World Health Organization. Accessed September 15, 2023. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39554

- 9.Al-Khatib SM, Stevenson WG, Ackerman MJ, et al. 2017 AHA/ACC/HRS guideline for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and the prevention of sudden cardiac death: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. Circulation. 2018;138(13):e272-e391. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iribarren C, Crow RS, Hannan PJ, Jacobs DR Jr, Luepker RV. Validation of death certificate diagnosis of out-of-hospital sudden cardiac death. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82(1):50-53. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9149(98)00240-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tseng ZH, Olgin JE, Vittinghoff E, et al. Prospective countywide surveillance and autopsy characterization of sudden cardiac death: POST SCD study. Circulation. 2018;137(25):2689-2700. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tseng ZH, Moffatt E, Kim A, et al. Sudden cardiac death and myocardial fibrosis, determined by autopsy, in persons with HIV. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(24):2306-2316. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Census Bureau . QuickFacts: San Francisco County, California. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/sanfranciscocountycalifornia

- 14.City and County of San Francisco Dept of Homelessness and Supportive Housing . 2022 San Francisco PIT count. Accessed November 30, 2022. https://hsh.sfgov.org/get-involved/2022-pit-count/

- 15.Applied Survey Research . 2011 San Francisco County homeless point-in-time county & survey comprehensive report. Published online 2011. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://hsh.sfgov.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/2011SanFranciscoHomelessComprehensiveReport_FINAL.pdf

- 16.Applied Survey Research . 2013 San Francisco County homeless point-in-time county & survey comprehensive report. Published 2013. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://hsh.sfgov.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/San-Francisco-PIT-Homeless-Count-2013-Final-February-13-2014.pdf

- 17.US Census Bureau . Annual estimates of the resident population for counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019. Accessed January 13, 2023. https://www.census.gov/data/datasets/time-series/demo/popest/2010s-counties-total.html

- 18.Fine DR, Dickins KA, Adams LD, et al. Drug overdose mortality among people experiencing homelessness, 2003 to 2018. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(1):e2142676. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.42676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baggett TP, Liauw SS, Hwang SW. Cardiovascular disease and homelessness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(22):2585-2597. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.02.077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Riggs KR, Hoge AE, DeRussy AJ, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with nonfatal overdose among veterans who have experienced homelessness. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(3):e201190. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.1190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodriguez RM, Montoy JCC, Repplinger D, Dave S, Moffatt E, Tseng ZH. Occult overdose masquerading as sudden cardiac death: from the Postmortem Systematic Investigation of Sudden Cardiac Death study. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(11):941-944. doi: 10.7326/M20-0977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Balla S, Alqahtani F, Alhajji M, Alkhouli M. Cardiovascular outcomes and rehospitalization rates in homeless patients admitted with acute myocardial infarction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2020;95(4):660-668. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2020.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Council of Economic Advisers . The state of homelessness in America. Accessed September 9, 2022. https://www.nhipdata.org/local/upload/file/The-State-of-Homelessness-in-America.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Proportion of Sudden Arrhythmic Deaths with Causes Known Premortem in Homeless vs. Housed Populations

eAppendix.

Data Sharing Statement