Abstract

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events during childhood known to affect health and well-being across the life span. The detrimental impact ACEs have on children and young people is well-established. It is also known that 85 to 90% of children have at least one sibling. Using this as the foundation for our inquiry, the purpose of this scoping review was to understand what we currently know about the experiences of siblings living with ACEs. Sibling relationships are unique, and for some the most enduring of experiences. These relationships can be thought of as bonds held together by love and warmth; however, they can also provide scope for undesirable outcomes, such as escalation of conflicts and animosities. This scoping review was conducted following Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) methodological framework, complemented by the PAGER framework (Bradbury-Jones et al. 2021), offering a structured approach to the review’s analysis and reporting through presenting the Patterns, Advances, Gaps, and Evidence for practice and Research. In June 2020, we searched 12 databases, with 11,469 results. Articles were screened for eligibility by the review team leaving a total of 148 articles meeting the inclusion criteria. Included articles highlighted overwhelming evidence of older siblings shielding younger siblings, and the likelihood that when one sibling experiences adversity, other siblings will be experiencing it themselves or vicariously. The implications of this in practice are that support services and statutory bodies need to ensure considerations are given to all siblings when one has presented with experiencing childhood adversity, especially to older siblings who may take far more burden as regards care-giving and protection of younger siblings. Given that more than half of the included articles did not offer any theoretical understanding to sibling experiences of ACEs, this area is of importance for future research. Greater attention is also needed for research exploring different types of sibling relationships (full, step, half), and whether these influence the impact that ACEs have on children and young people.

Keywords: adverse childhood experiences, siblings, violence and abuse, trauma

Background/Context

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are traumatic events during childhood that are known to affect health and well-being across the life span (Crouch et al., 2019; Hargreaves et al., 2017; Leban & Gibson, 2019). There is not one fully agreed list of ACEs (Finkelhor, 2020). Depending on a study’s methodological approach, definitions and the number of ACEs measured can vary, with the first study conducted in the 1990s measuring only seven ACEs (Felitti et al., 1998; Manyema & Richter, 2019). The second wave of studies updated this list to a total of ten within three categories, which now appear to be the most commonly used:

abuse (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse)

neglect (emotional neglect, physical neglect)

household dysfunction (domestic violence and abuse, substance abuse, mental illness, parental separation or divorce, incarceration) (Hargreaves et al., 2017; Manyema & Richter, 2019).

These ten ACEs are the focus of this review. There does however continue to be variation between studies; a 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health in the United States chose to only measure nine ACEs, two of which were racial/ethnic mistreatment and economic hardship (Crouch et al., 2019). There are ongoing debates around which ACEs should be measured and the implications or limitations of studies when they do not include stressors that affect a child’s well-being; an example of this being poverty (Hughes & Tucker, 2018).

Variations among studies are also seen with their approach to measuring ACEs. Blum et al. (2019) identified the four most commonly used approaches: (a) cumulative ACEs scores, (b) weighting individual ACEs, (c) weighting ACEs by subgroup, and (d) ACEs typology.

(1) Cumulative ACEs score is when the number of unique ACEs are added together and no consideration is given to frequency, duration, or intensity (Blum et al., 2019).

(2) Weighting individual ACEs involves giving consideration to particular characteristics of each ACE and these being weighted accordingly; events that are more recent, severe, or frequent are weighted higher (Blum et al., 2019).

(3) Weighting ACEs by subgroup consists of ACEs being grouped into categories and each category being weighted rather than the individual ACE, creating a hierarchy of severity (Blum et al., 2019).

(4) ACEs typology involves clustering ACEs together when assessing against them, such as “low ACEs,” “household dysfunction,” “emotional ACEs,” and “high/multiple ACEs” (Blum et al., 2019).

The first study (Felitti et al., 1998) used the ACEs typology approach, asking a total of eight questions within the category of childhood abuse and nine questions within the category of household dysfunction. Respondents were defined as exposed to a category if they responded “yes” to one or more of the questions in that category (Felitti et al., 1998).

The prevalence of ACEs has been discussed at length, with the original ACE study finding one in four adults reporting three or more ACEs (Felitti et al., 1998). Later studies have found them to be somewhat more prevalent within particular populations such as children in care and children within the welfare system (Bramlett & Radel, 2014; Hargreaves et al., 2017). Correlations have also been identified with regards to the number of ACEs individuals are likely to encounter; Duke et al. (2010) assert that individuals who report at least one ACE are likely to report experiencing others, with Baglivio and Epps (2016) strengthening this by finding 67% of their participants who were exposed to one ACE had also been exposed to four or more (Leban & Gibson, 2019).

ACEs impact a child’s social and emotional development as well as causing poor health across their life course, such as having a greater risk of poor physical or mental health, chronic disease, and cancer (Blum et al., 2019; Choi et al., 2019; Crouch et al., 2019). Associations have also been found between ACEs and health harming behaviors such as drug use and smoking at an early age alongside developing depression and anxiety and also premature death (Brown et al., 2009; Chapman et al., 2004; Crouch et al., 2019; Dube et al., 2003). Exposure to childhood adversity can also disrupt healthy brain development in childhood (Crouch et al., 2019; Garner, 2013; Shonkoff et al., 2009, 2012).

The identification of ACE exposure can inform early interventions, thus potentially mitigating negative long-term impacts; however, limitations have been found with this process (Crouch et al., 2019). The lack of consistency in the number of ACEs measured and methodological approaches make it more difficult to create a consistent understanding between studies (Hargreaves et al., 2017; Manyema & Richter, 2019). In addition, the study of ACEs is often undertaken retrospectively, relying on the recall of adults around exposure in childhood. Potential information biases can therefore be a major threat (Anda et al., 2006; Crouch et al., 2019). Exploring ACEs contemporaneously with children and young people, rather than retrospectively as adults, has been found to improve the ability of services and caregivers to mitigate the exposure and impact, reducing the likelihood of poor outcomes (Crouch et al., 2019).

Sibling Relationships

Compared to other family relationships, sibling relationships are understudied, despite being the longest-lasting relationship in most people’s lives (Gilligan et al., 2020). As many as 85 to 90% of children are reported to grow up with at least one brother or sister (Milevksy, 2011; Tippett & Wolke, 2015). Siblings may or may not be blood related, and the definition of siblings can vary between studies. Kiselica and Morrill-Richards (2007, p.149) provide a useful outline of the different types of sibling relationships. These relationships include “biological siblings (share both parents), half-siblings (one parent in common), step-siblings (connected through marriage of parents), adoptive siblings, foster siblings (joined through a common guardian), or fictive siblings (united by emotional bond).” Others (Bass et al., 2006) recognize children who had been living together in the same family and had assumed the role of siblings for two or more years. The definition of sibling used in this review includes all the aforementioned sibling types.

The sibling relationship is unique and for some can be one of the most enduring relationships we have, starting at birth and continuing until death. Siblings can provide an important source of support and play a vital role in an individual’s well-being (Davies, 2015; Edwards et al., 2006; Exley, 2021; Yucel & Yuan, 2015). These relationships can be characterized by love and warmth, providing security and the opportunity to develop social abilities and self-identity (Davies 2015; Edwards et al., 2006). However, sibling relationships can also provide scope for undesirable outcomes, such as escalation of conflicts and animosities (Buist et al., 2013). Some sibling relationships may be ingrained with rivalry and conflict, with emotional distance being introduced when they leave the parental home.

The detrimental impact ACEs have on children and young people is well-established. It is also known that 85 to 90% of children have at least one sibling. Using this as the foundation for our inquiry, the current study provided a review and summary of what is currently known about the experiences of siblings living with ACEs. We aimed to compare the existing literature to produce a summary of current knowledge in the field. We also aimed for this review to provide valuable insight that could help statutory bodies, service providers, and policy makers develop effective intervention and/or prevention approaches. The question posed in this review is what do we currently know about the experiences of siblings living with ACEs?

Methods

The extent of understanding around siblings living with ACEs is currently unknown. A scoping review therefore is most appropriate for identifying relevant existing work. Scoping reviews seek to examine and summarize available research to identify gaps and whether further research is needed (Levac et al., 2010; Munn et al., 2018). Unlike a systematic review, a scoping review enabled us to complete a wide-ranging examination of the literature with broader inclusion criteria (Munn et al., 2018). Scoping reviews, however, can still be systematic and rigorous to ensure the reliability of findings when following key methodological frameworks (Levac et al., 2010).

This scoping review was conducted following Arksey and O’Malley’s (2005) methodological framework of a five-stage approach: identifying the research question; searching for relevant studies; selecting studies; charting data; and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results. This approach has been complemented by the PAGER framework (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2021) which offers a structured approach to the analysis and reporting of scoping reviews through presenting the Patterns, Advances, Gaps, and Evidence for practice and Research within the included articles. Articles within this scoping review were identified following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and MetaAnalyses extension for Scoping Reviews (Moher et al., 2009; Tricco et al., 2018). This comprehensive approach enabled an exploration across multiple disciplines to answer one key question: What do we currently know about the experiences of siblings when living with ACEs? (Peters et al., 2015).

Search Strategy

The search terms were developed by the review team and reviewed and revised multiple times by the first author. They included terms for children and young people AND siblings AND ACEs (see Table 1 for full list of search terms).

Table 1.

Keywords for Database Searches.

| Children and Young People Terms AND | Sibling Terms AND | Adverse Childhood Experiences Terms |

|---|---|---|

| adolescen* OR child* OR teen* OR “young people” OR “young person” | sibling* OR brother* OR sister* OR step-brother* OR step-sister* OR half-brother* OR half-sister* OR twin* | “adverse childhood experience*” OR “childhood trauma” OR trauma* OR abuse* OR “physical abuse” OR assault* OR attack* OR “emotional abuse” OR “sexual abuse” OR rape* OR groom* OR “physical neglect” OR neglect* OR “emotional neglect” OR “mental illness” OR “mental health” OR “incarcerated relative*” OR prison* OR incarcerat* OR arrest* OR “domestic violence” OR “domestic abuse” OR “marital violence” OR “intimate partner violence” OR “gender-based violence” OR “substance abuse” OR “substance misuse” OR drug* OR alcohol* OR addict* OR divorc*. |

Multiple initial searches were completed of databases at the start of 2020 to confirm all articles meeting the inclusion criteria were being captured within the final searches. Consultation with the University’s library also enabled the review team to ensure they had identified the most relevant databases for the final search. In June 2020, the first author completed the final search producing 11,469 articles from 12 databases: Consumer Health Database, CINAHL, EMBASE, Healthcare Administration Database, Medline, PILOTS, PubMed, ProQuest Central, PsychInfo, Web of Science, Applied Social Sciences Index & Abstracts, and the International Bibliography of the Social Sciences. Included articles remained up to 2019 as to include the latest full year of research completed. Literature was selected if it met the criteria set out in Table 2. No limit was set for the age of participants so as to include both studies which collect data from children and young people and also those which collect from adults retrospectively. Articles were included if they explored any singular ACE or multiple ACEs. The ACEs included in our review were abuse (emotional abuse, physical abuse, sexual abuse), neglect (emotional neglect, physical neglect), and household dysfunction (domestic violence and abuse, substance abuse, mental illness, parental separation or divorce, incarceration) (Hargreaves et al., 2017; Manyema & Richter, 2019).

Table 2.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria.

| Category | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Peer-reviewed, empirical articles only | Grey literature, conference papers (including poster abstracts), research protocols, books, unpublished thesis/dissertations |

| Focus | Considered siblings in the context of any singular or multiple ACE. | Did not explicitly focus on at least one ACE |

| Relevance | Adversity took place between birth and 18. Siblings are considered within the article |

Articles that do not have any considerations of siblings. |

| Timeframe | Published 2005–2019 | |

| Language | English language only |

Note. ACE = adverse childhood experience.

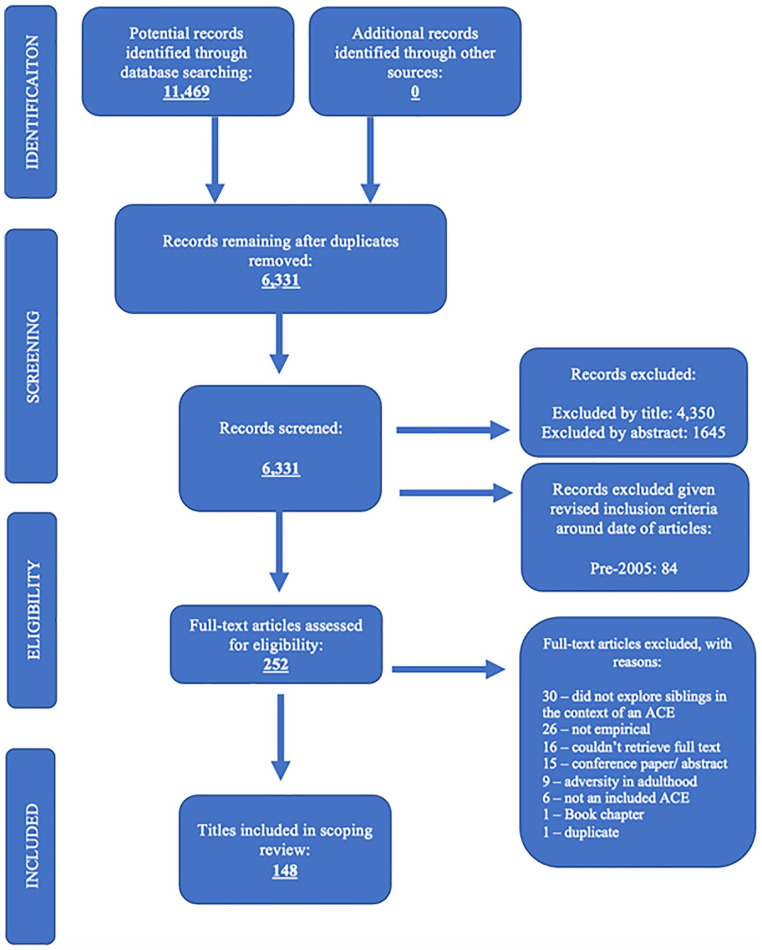

Duplicates were removed, leaving 6,331 articles to be screened by title and abstract; 4,350 articles were excluded by title and a further 1,645 by abstract, leaving 336 articles for full-text reviews. Ten percent of the remaining 252 were reviewed by abstract and title by two reviewers (JT & CB-J) and by full text by another reviewer (MaM). Any discrepancies were discussed and resolved. A total of 104 articles were excluded following full-text reviews, leaving 148 articles within this scoping review. See PRISMAScR Diagram in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMAScR diagram.

A literature matrix was created by the first author and shared with two other reviewers (JT & CB-J) for discussion and review. The following data was extracted from each of the 148 included articles: author, year, title, country of origin, research method, theoretical input, sample size, sample demographic, type of ACE, whether the term “ACE” was used, sibling type, whether siblings were the primary focus, and an overview of the article’s key findings. Analysis was completed using the PAGER Framework, starting with the identification of patterns (Bradbury-Jones et al., 2021). Patterns were identified in two stages; initially within each individual ACE category before being identified across multiple ACE categories. BD created spider diagrams for each ACE as a visual tool to organize the data in a logical way for appraisal and analysis (see example in Figure 2). Every included article was given an identification number. As topics were identified they would be added to the spider diagram, along with the corresponding number of any article that used its citation. The review team then cross-referenced commonalities across all diagrams produced, thus starting to identify patterns in the data. This process then enabled further analysis of data to identify Advances, Gaps, and Evidence for practice and Research.

Figure 2.

Example of data preparation.

Findings

Descriptive Summary

Table 3 provides a full overview of the characteristics of included articles. Articles were located worldwide (24 countries) with the vast majority conducted in the United States (75 articles, 51%); a significant jump from the second highest being the United Kingdom (UK) at 17 articles (11%). We included articles that focused on ACEs, aiming to capture a range of relevant demographic factors, including, for example, gender, ethnicity, disability, and deprivation. Given the geographical reach, by default, issues of ethnicity will have been a consideration within some articles based upon where they were conducted. However, an explicit discussion of diversity was noticeably lacking within the included studies. Age and gender have been considered within a large proportion of the included articles, with many exploring the role of the older sibling in particular, and others considering gender differences in understanding of experiences. Other protected characteristics however, such as race, religion, sexual orientation, and disability, are notably absent in existing literature and we have identified this as a gap that needs to be addressed in the reporting of future studies.

Table 3.

Article Characteristics.

| Variable | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2005–2007 2008–2010 2011–2013 2014–2016 2017–2019 |

21 (14%) 23 (16%) 23 (16%) 36 (24%) 45 (30%) |

| Country of publication | Australia Bangladesh Canada China Croatia Finland Germany Hong Kong Ireland Israel Japan Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Pakistan Portugal Saudi Arabia South Africa South Korea Spain Sweden Turkey United Kingdom USA |

8 (5%) 1 (<1%) 11 (7%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 2 (1%) 4 (3%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 9 (6%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 2 (1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 2 (1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 1 (<1%) 3 (2%) 2 (1%) 17 (11%) 75 (51%) |

| Sample type | Children and young people Parent/carers Adults retrospectively Professionals Combination |

83 (56%) 16 (11%) 28 (19%) 6 (4%) 15 (10%) |

| ACE type | Physical abuse Emotional abuse Sexual abuse Neglect Mental illness Divorce Incarcerations Substance abuse Domestic violence ACE Maltreatment |

40 (27%) 2 (1%) 20 (20%) 2 (1%) 8 (6%) 16 (11%) 6 (4%) 10 (7%) 14 (9%) 12 (8%) 8 (6%) |

| Study design | Secondary data analysis Surveys and questionnaires Interviews Case studies Focus groups Mixed methods Observational |

40 (27%) 41 (28%) 37 (24%) 17 (11%) 2 (1%) 10 (7%) 1 (<1%) |

Note. ACE = adverse childhood experience.

The articles were clustered by childhood adversity type: physical abuse (27%; 40/148), emotional abuse (1%; 2/148), sexual abuse (20%; 30/148), neglect (1%; 2/148), mental illness (6%; 8/148), divorce (11%; 16/148), incarceration (4%; 6/148), substance abuse (7%; 10/148), domestic violence (9%; 14/148), ACE (8%, 12/148), and maltreatment (6%; 8/148). Disparities between the terminology and definitions used meant decisions were made regarding which ACE category some articles were grouped within. Articles which explored broad categories of trauma or child abuse (Foroughe & Muller, 2014; Heins et al., 2011; Lo et al., 2017) or explored multiple but not all of the ACEs included in this review (Hindle, 2007; Wolfe, 2016) were included in the ACE grouping. The small number of articles exploring neglect (n = 2) did not differentiate between physical and emotional neglect, so these have been grouped together within the overarching category of neglect. A category of maltreatment was introduced to the review following a number of articles (n = 8) which used this term to cover a combination of abuse and neglect.

While there is a growing body of literature considering siblings’ experiences of ACEs as a whole, most papers (92%) took the approach of exploring individual ACEs rather than the collective. Of the included articles, 107 (72%) directly focused on siblings whereas the remaining articles explored siblings within their findings despite not being the study’s main focus. Excluding the 40 secondary analysis articles, the most common sample population was children (56%; 83/148) followed by adults providing retrospective reports (19%; 28/148).

Sibling Dynamics

Sibling birth order

Exploring the role of the older sibling was a central theme within many articles. Several papers found evidence that older siblings often position themselves as carers. Older siblings can protect their younger siblings from the ACE, who are seen as more vulnerable (Akerlund, 2017; Callaghan et al., 2016; Foroughe & Muller, 2014; Kaye-Tzadok & Davidson-Arad, 2016; Piotrowski, 2011; Ronel & Haimoff-Ayali, 2010; Tedgård et al., 2019; Vasquez & Stensland, 2015; Woodward & Copp, 2016). Depending on the type of adversity being experienced, older siblings have been found to either buffer and reduce the potential impact for their younger siblings, or protect them from experiencing further abuse (Foroughe & Muller, 2014; Piotrowski, 2011; Vasquez & Stensland, 2015; Woodward & Copp, 2016). Older siblings have been found to further take on the role of the parent, protecting their siblings and sometimes their parent too. Papers such as Tedgård et al. (2019) refer to this as parentification. Children and young people shared with Ronel and Haimoff-Ayali (2010) that due to parental substance abuse and therefore the absence of parents, older siblings saw themselves as substitutes for their parents.

While articles including Kaye-Tzadok and Davidson-Arad (2016) identified that caring for younger siblings enabled older siblings to find meaning in their abuse, others highlighted negative implications. These included increased exposure for older siblings, older siblings masking their own needs and older siblings experiencing more negative impacts from the ACE (Al-Quaiz & Raheel, 2009; Callaghan et al., 2016; Heins et al., 2011; Tailor et al., 2015). Studies indicated that while older siblings can protect younger siblings from the impact of ACEs, this can be to their own detriment with older siblings holding the burden of responsibility (Buckley et al., 2007; Carmel, 2019; Tedgård et al., 2019).

Sibling relationships

Several papers have explored sibling relationships in the context of experiencing ACEs, emphasizing their importance (Akerlund, 2017; Frank, 2008; Geschiere et al., 2017; Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; Noller et al., 2008). This relationship, which for some may be the only viable ongoing relationship, can either improve or worsen the impact of their experiences (Kothari et al., 2017; Piotrowski, 2011). Following surveys completed with children in Sweden, Jernbro et al. (2017) identified that children experiencing physical abuse often chose to make their first disclosure to a sibling. Siblings have been found to provide an important source of support, with the absence of a sibling being associated with higher likelihood of experiencing negative effects from ACEs (Geschiere et al., 2017). Sibling companionship can promote resilience, alleviate potential strains, and predict improved adjustment to the childhood adversity experienced (Jacobs & Sillars, 2012; Vermeulen & Greeff, 2015; Wolfe, 2016).

However, while positive sibling relationships have been found to lessen the impact of ACEs, poor sibling relationships can worsen the impact (Woodward & Copp, 2016). Experiencing childhood adversity can also be the cause of conflict between siblings (Noller et al., 2008; Tucker et al., 2014; Wolfe, 2016). A case study of two brothers by McGarvey and Haen (2005), for example, described the siblings as having a “traumatic bond” whereby they would re-enact their abusive experiences with each other. Further, when exploring the impact of divorce, Civitci et al. (2009) recognized that children and young people with a higher number of siblings can feel the need to compete with each other for their parents’ attention, causing conflict within their sibling relationships. Increased conflict and poor sibling relationships have been found to increase levels of loneliness and add further stress in the aftermath of ACEs, worsening the impact (Noller et al., 2008; Wolfe, 2016).

A small number of articles have begun to consider whether siblings should be placed together when removed from the care of their parents (Cashmore & Parkinson, 2008; Hindle, 2007; Kothari et al., 2017). Hindle (2007) presents case studies of siblings within the UK, sharing the placement decisions for siblings after suffering profound neglect and witnessing violence in the home. While most of these siblings had been placed separately, other articles advocated for siblings to be placed together, arguing it to be critical for children’s sense of connection, emotional support, and continuity (Cashmore & Parkinson, 2008; Kothari et al., 2017).

Davies (2015) is in the minority, having explicitly considered sibling relationships that are not biological. Their article recommended that professionals considering care arrangements should not only consider biological relationships, but also other types of sibling relationships. While most of the articles included in this review either do not specify the type of sibling relationship, or imply a focus on full biological sibling relationships, a small number gave consideration to half-siblings and stepsiblings (Gatins et al., 2014; Hollingsworth et al., 2008). Hollingsworth et al. (2008) reported that stepsiblings are particularly vulnerable to emotional abuse from parents, who may draw siblings in to also cause harm. Gatins et al. (2014) however found that children and young people affected by divorce appear to be better adjusted when they have half-siblings compared to those who only have full biological siblings. Articles explicitly exploring different types of sibling relationships appear to be lacking.

The Identification of Siblings

Identifying siblings experiencing ACEs

Some articles, particularly those focusing on maltreatment or neglect, reported that when one child has been identified as experiencing abuse there is an increased risk for their siblings to also experience abuse (Hamilton-Giachritsis & Browne, 2005; Hines et al., 2006; Lang et al., 2013; MacMillan et al., 2013; Witte et al., 2018). When the childhood adversity results in fatality, surviving siblings are perceived to be at an even greater risk of harm (Damashek & Bonner, 2010). In a retrospective study completed by Witte et al. (2018), 59% of the 870 sibling pairs reported that both siblings had experienced maltreatment. Siblings have also been found to be at risk of experiencing vicarious trauma from seeing the abuse of their sibling (Hollingsworth et al., 2008; Keane et al., 2013). Having a sibling in itself has been found to be a risk indictor for ACEs, with studies finding those with multiple siblings more likely to experience adversity in their childhood (Benjet et al., 2009; Bussemakers et al., 2019). Being a twin, moreover, has been highlighted as increasing risk, with Lindberg et al. (2012) demonstrating the increased stress of caring simultaneously for two children is a likely cause of childhood abuse.

Although there is an increased likelihood of multiple siblings experiencing childhood adversity, several papers asserted that the traumatic events are often experienced very differently (Boynton et al., 2011; Horn et al., 2013; Skopp et al., 2005; Piotrowski, 2011; Piotrowski et al., 2014). Even with shared traumatic experiences, children and young people can perceive the experience very differently and their reactions are unique (Horn et al., 2013; Skopp et al., 2005). Some articles suggest that age or gender may be the cause of these different perceptions (Piotrowski, 2011; Piotrowski et al., 2014). Morrill et al. (2019) offered other possible causes, including varying exposure, individual perceptions, and unique characteristics such as emotion regulation. With a focus on parental substance abuse, Boynton et al. (2011) found that siblings can have different memories of parental alcoholism resulting in one saying their parent was an alcoholic, when the other may not.

Siblings Who Cause Harm to Other Siblings

Sibling violence and abuse

Substantial consideration has also been given to siblings causing harm to other siblings, with this being the focus of nearly 40% of included articles. Several of these papers have identified abuse from a sibling as one of the most common forms of violence in the home (Finkelhor et al., 2009; Kim & Kim, 2019; McDonald & Martinez, 2017; Meyers, 2014; San Kuay et al., 2016; Soler et al., 2015). Multiple papers however highlighted a significant difference in the perception and understanding of this form of abuse. Despite its prevalence and documented detrimental impact, sibling violence and abuse is often dismissed as normal or expected (Button & Gealt, 2010; Desir & Karatekin, 2018; Kim & Kim, 2019; Phillips et al., 2018; Sporer, 2019; Tippett & Wolke, 2015; van Berkel et al., 2018). Parents in particular have been highlighted as holding these views, being found to often minimize the frequency, severity, and impact (Tucker et al., 2013). Aggression between siblings can often be seen as normative and harmless by parents (Miller et al., 2012; van Berkel et al., 2018) with some having difficulty in determining what behaviors are acceptable (McDonald & Martinez, 2019). Tompsett et al. (2018) further find that children themselves can also minimize abuse and violence from a sibling.

Hoffman et al. (2005) and Tompsett et al. (2018) are in the minority, having given consideration to theoretical understandings of sibling violence and abuse. They highlight from a social learning perspective that children who experience abuse from a parent are likely to then use violence against a sibling (Hoffman et al., 2005). Aggressive parents model this behavior as acceptable, leading to their children becoming more aggressive themselves (Tompsett et al., 2018).

Sibling sexual abuse

Within the dataset of articles exploring sibling violence and abuse are a subset of papers which explored children and young people who are sexually abused by a sibling (n = 23), a crossover between the sibling violence and abuse articles and the sexual abuse articles. Many articles share the detrimental impact this ACE can have, finding survivors to experience anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as being estranged from siblings or parents, and having potential future relationship or intimacy problems (Beard et al., 2013; Carlson, 2011; Falcão et al., 2014). Of significance are some of the unique implications of having a sibling cause this harm. Studies have found that it is possible for the abuse to be longer-lasting due to the accessibility of siblings, and even small age gaps between siblings can create a significant power imbalance (Carlson et al., 2006; Tener & Silberstein, 2019). Tener and Silberstein (2019) further highlight that for many, this abuse only ends when the siblings leave the family home.

Like with other forms of sibling abuse, studies suggest that sibling sexual abuse is often normalized, most often by parents and guardians (Tarshish & Tener, 2019; Tener et al., 2018). Some parents have been found to see these behaviors as harmless, perceiving it as a form of age-appropriate curiosity; others are believed to minimize it or deny due to shame (Tarshish & Tener, 2019; Tener et al., 2018, 2019). Bass et al. (2006), for example, presented two contrasting case studies of families where there had been sibling incest; one of the families found the behavior normal whereas the other did not. Although there is a high prevalence of sibling sexual abuse, this particular ACE has been found to be rarely reported (Carlson et al., 2006; Celbis et al., 2006; Joyal et al., 2016; Katz & Hamama, 2017). Some articles argued this to be due parental perceptions normalizing the behavior, or not recognizing the serious nature of the abuse, while others found parents to respond to disclosures with disbelief (Krienert & Walsh, 2011; McDonald & Martinez, 2017; Morrill, 2014).

The underreporting of sexual abuse between siblings has been argued to have hindered large-scale research in this area (Krienert & Walsh, 2011). One of the difficulties associated with researching sibling sexual abuse is the lack of a universally accepted definition and understanding (Caffaro & Conn-Caffaro, 2005). Beard et al. (2013), for example, define this abuse as any form of sexual behavior among relatives in their own study. Bass et al. (2006, p. 93) in comparison, define it as “sexual behavior between siblings that results in feelings of anger, sadness, or fear in the child who did not initiate the behavior”; implying that some sexual behavior would not be considered abusive. These different understandings means that those included in the sample population can vary significantly, potentially affecting the findings of studies.

Discussion

Patterns and advances within this review’s PAGER framework present an overview of what we currently know about the experiences of siblings when living with ACEs (the critical findings). Implications for practice, policy and research are also shared within the PAGER’s framework through gaps, evidence for practice and research recommendations. A full overview of this review’s PAGER framework is provided in Table 4.

Table 4.

PAGER Framework.

| Patterns | Advances | Gaps | Evidence for Practice | Research Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The influence of birth order | There is evidence of older siblings protecting younger siblings from the impact of ACEs. | There is the need for ongoing empirical work exploring the potential increased impact on older siblings who are shielding younger siblings from the ACE. | It is important that support services consider their response to older siblings who may take far more burden than their younger siblings. | To expand research exploring the potential increased impact on older siblings who are shielding younger siblings from the ACE. |

| The influence of sibling relationships | Understanding is growing around how a positive sibling relationship can reduce the impact of ACEs. | Little consideration has been given to the different types of siblings (full, step, half), and whether this influences the impact of ACEs. | It is important for statutory bodies to consider the positive benefit of sibling bonds, especially when making decisions around whether to place siblings together when removed from the care of their parents. | Far greater attention needs to be given to research exploring different sibling relationships (full, half, step). |

| Identifying siblings experiencing ACEs | There is some evidence that when one sibling experiences ACEs, it is likely that other siblings are also experiencing it. | There is limited evidence about how agencies identify whether other siblings have also experienced the ACE. | It is important to consider all siblings when one has presented with experiencing childhood adversity. Siblings need to be included in screening and referrals into interventions. | Research is needed that explores how agencies identify whether other siblings have also experienced ACEs. |

| Siblings who cause the harm | Substantial consideration has been given to siblings harming other siblings. The abusive behavior is often normalized and minimized when it is a sibling causing the harm. |

Focus tends to be on parents minimizing the abuse, with little consideration being given to the views and responses of practitioners and services. | It is important that support services consider their response to sibling abuse, especially when the physical abuse can be bi-directional. | Need more research which considers the views and responses of practitioners and services to children and young people causing harm to siblings. |

| Focus on individual ACEs | There is a growing body of literature considering siblings experiencing ACEs. Most explore individual ACEs rather than the collective. |

Some ACEs are explored substantially more than others. More than half do not offer any theoretical understanding. There is a lack of consideration given to diversity among studies to date. |

More evidence will emerge from future research considering theory. | Theoretical understanding is vital within this area of research. Diversity needs to be addressed in the reporting of future studies. |

Note. ACE = adverse childhood experience.

Sibling Birth Order

A clear advance identified within this review has been the overwhelming evidence of older siblings being a protective factor for their younger siblings, shielding them from adverse experiences. Described by Tedgård et al. (2019) as parentification, their buffering role also finds them taking on the role of the parent. While there has been lot of recognition for the vulnerabilities of younger siblings, substantially less thought has been given to older siblings. Further consideration is now needed around how this protective role impacts the older sibling. This knowledge will be of significance to frontline support services who need to consider their response to older siblings who may take far more burden than their younger siblings.

Sibling Relationships

One of the gaps evident from this scoping review is the lack of research exploring sibling types outside of biological siblings. Very few studies have explored step-, half-, and adoptive-siblings; the majority either do not specify the type of sibling relationship or imply a focus on full biological sibling relationships. The findings of Gatins et al. (2014) that divorce appears to affect those with half-siblings differently to those who only have full biological siblings, indicate that this is an area that needs more consideration. Further research needs to be undertaken which explores the wide range of sibling relationships within society in order to understand if this influences the impact of ACEs. It will be important for statutory bodies to consider these findings in practice, especially when making decisions around whether to place siblings together when removed from the care of their parents.

Identifying Siblings Experiencing ACEs

There is growing evidence that when one sibling experiences adversity, it is likely that their other siblings are also experiencing it, or be at risk of experiencing vicarious trauma. Lindberg et al. (2012) identified twins in particular as being at increased risk of experiencing childhood abuse. Given this correlation, a small number of articles have considered what this means for intervention programs (Ahrons, 2007; Farnfield, 2017; Morrill et al., 2019; Renner & Boel-Studt, 2017; Renner & Driessen, 2019; Skopp et al., 2005). Some studies have argued that interventions are more meaningful when they include siblings; however, in most cases only one child from a family will be referred (Ahrons, 2007; Farnfield, 2017). Recommendations have been made that service providers would be wise to assess all siblings within a family when one has experienced ACEs, and siblings should furthermore be considered when planning services, completing screenings, and undertaking assessments (Morrill et al., 2019; Renner & Boel-Studt, 2017). Renner and Driessen (2019) go further to demonstrate that while siblings need increased attention from services, the needs of all family members should be assessed. Skopp et al. (2005) are clear that in practice this does not simply mean referring all siblings to support programs, as this would not be a good use of resource. Rather, individually assessing all siblings within families is much more appropriate. Knowledge of how agencies approach the identification of siblings, however, is lacking meaning further targeted research around this is required.

Siblings Who Cause Harm to Other Siblings

Substantial advances have been made in the exploration of siblings harming other siblings. An overwhelming pattern across the studies is how this abusive behavior is often normalized and minimized, especially by parents. Considerable underreporting has been highlighted as hindering research in this area (Krienert & Walsh, 2011), with little consideration being given to the views and responses of practitioners and frontline services. Tippett and Wolke (2015) recognize the unique nature of this childhood adversity in that the abusive behavior can be bi-directional, meaning the response of support services is of importance. With research focusing more on the views of parents, future research must consider the views and responses of practitioners and services to children and young people causing harm to their siblings.

Focus on Individual ACEs

While some advances are being made in terms of research exploring multiple co-existing ACEs, the majority have explored them in isolation. This has resulted in some types of childhood adversity, such as physical abuse and sexual abuse, being explored to a greater degree. Research exploring some of the less studied ACEs, or ACEs collectively, is required to develop current understanding. Children and young people who experience one form of childhood adversity are likely to experience multiple, meaning exploring ACEs as a collective would be appropriate. Consideration of theory within the included articles was overwhelmingly poor, with more than half not offering any theoretical understanding. A more thorough understanding around the experiences of siblings when living with ACEs would emerge from future research considering theory; this is a vital consideration going forward.

Tables 5 and 6 provide a summary of the critical findings from this review and the implications for practice, policy, and research.

Table 5.

Summary of Critical Findings.

| Critical Findings |

|---|

| • 148 articles exploring siblings living with ACEs were included. • The majority of included articles have explored individual ACEs in isolation. • Very few articles have explicitly considered sibling relationships that are not biological. • Consideration of theory within the included articles was overwhelmingly poor, with more than half not offering any theoretical understanding. • Older siblings can protect younger siblings from the impact of ACEs; however, this can be to their own detriment with older siblings holding the burden of responsibility. • Support services must consider their response to older siblings who may take far more burden. • Siblings have been found to provide an important source of support lessening the impact of ACES, however these experiences can also be the cause of conflict between siblings. • There is growing evidence that when one sibling experiences adversity, it is likely that their other siblings are also experiencing it, or be at risk of experiencing vicarious trauma. • Service providers would be wise to assess all siblings within a family when one has experienced ACEs; in practice, this does not simply mean referring all siblings. • Substantial advances have been made in the exploration of siblings harming other siblings; this abusive behavior is often normalized and minimized. |

Note. ACE = adverse childhood experience.

Table 6.

Summary of Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research.

| Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research |

|---|

| • Support services must consider their response to older siblings who may take far more burden than their younger siblings. • Statutory bodies need to consider the positive benefit of sibling bonds when making decisions around sibling placements into care. • It is important to consider all siblings when one has presented with experiencing childhood adversity. • Siblings need to be included in screening and referrals into interventions. • Support services need to consider their response to sibling abuse. • Far greater attention needs to be given to research exploring different sibling relationships (full, half, step). • Future research should consider the views of practitioners to children and young people causing harm to siblings. • Research exploring some of the less studied ACEs, or ACEs as a collective, is required to develop current understanding. • Theoretical understanding is vital within this area of research. |

Note. ACE = adverse childhood experience.

Limitations

Although the present review has successfully examined and summarized available research, and identified gaps and areas for further research, some limitations must be noted. First, this review did not assess the methodological quality of the articles included, as this was beyond the bounds of a scoping review. The aim of this review was to present an overview of what we currently know about the experiences of siblings when living with ACEs; however, the assessment of the methodological quality of studies would have added value. Second, we had to reduce the timeframe in which we included articles. While we had planned to include articles from 1995 to 2019 to capture all articles published since the first ACEs study, this timescale was reduced by 10 years due to not having the resource available to review the high volume of articles. Third, our review was also limited to empirical articles published in peer-reviewed journals. We recognize that there will be additional knowledge outside of this, including grey literature, not considered in this review.

Conclusion

This scoping review has examined what is currently known about the experiences of siblings living with ACEs. Included articles have highlighted overwhelming evidence of older siblings shielding younger siblings, and the likelihood that when one sibling experiences adversity, other siblings will be experiencing it themselves or vicariously. The implications of this in practice are that support services and statutory bodies need to ensure considerations are being made for all siblings when one has presented with experiencing childhood adversity, especially older siblings who may take far more burden. Given that more than half of the included articles did not offer any theoretical understanding, this area is of significant importance for future research. Far greater attention is also needed for research exploring different types of sibling relationships (full, step, half), and whether they influence the impact that ACEs have on children and young people.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tva-10.1177_15248380221134289 for Sibling Experiences of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Scoping Review by Ben Donagh, Julie Taylor, Muna al Mushaikhi and Caroline Bradbury-Jones in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse

Author Biographies

Ben Donagh is a doctoral researcher in the School of Nursing at the University of Birmingham, UK. He has over a decade of experience supporting children and young people experiencing violence, abuse, and trauma. His research focuses on the impact of domestic violence and abuse on children and young people, with an interest in sibling relationships and dynamics.

Julie Taylor, PhD, RN, is a Professor and Director of Research in the School of Nursing at the University of Birmingham, UK, and also at Birmingham Women and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust. She has extensive publication and research experience in child maltreatment and advocates for a public health approach to child protection.

Muna Al Mushaikhi, MSC, is a doctoral researcher in the School of Nursing at the University of Birmingham, UK. She has 20 years of pediatric and neonatal nursing experience in the Sultanate of Oman. Her research focus is on the prevention of child injuries.

Caroline Bradbury-Jones, PhD, RN, is Professor of Gender Based Violence and Health in the School of Nursing at the University of Birmingham, UK. Her research work is broadly within the scope of addressing inequalities and more specifically on issues of violence against women. She is the founder of the Risk, Abuse and Violence (RAV) research program at the University of Birmingham: http://www.birmingham.ac.uk/schools/nursing/research/rav.aspx

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Ben Donagh  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2072-3903

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2072-3903

Julie Taylor  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7259-0906

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7259-0906

Caroline Bradbury-Jones  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5237-6777

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5237-6777

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ahrons C. (2007). Family ties after divorce: Long-term implications for children. Family Process, 46(1), 53–65. 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2006.00191.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akerlund N. (2017). Caring or vulnerable children? Sibling relationships when exposed to intimate partner violence. Children & Society, 31(6), 475–485. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Quaiz A., Raheel H. (2009). Correlates of sexual violence among adolescent females in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal, 30(6), 829–834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anda R., Felitti V., Bremner J., Walker J., Whitfield C., Perry B., Dube S., Giles W. (2006). The enduring effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood. A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(3), 174–186. 10.1007/s00406-005-0624-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Baglivio M., Epps N. (2016). The interrelatedness of adverse childhood experiences among high-risk juvenile offenders. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice, 14(3), 179–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bass L., Taylor B., Knudson-Martin C., Huenergardt D. (2006). Making sense of abuse: Case studies in sibling incest. Contemporary Family Therapy, 28(1), 87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Beard K., O’Keefe S., Swindell S., Stroebel S., Griffee K., Young D., Linz T. (2013). Brother-brother incest: Data from an anonymous computerized survey. Sexual Addiction & Compulsivity, 20(3), 217–253. [Google Scholar]

- Benjet C., Borges G., Medina-Mora M., Zambrano J., Cruz C., Méndez E. (2009). Descriptive epidemiology of chronic childhood adversity in Mexican adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45(5), 483–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum R., Li M., Naranjo-Rivera G. (2019). Among young adolescents globally: Relationships with depressive symptoms and violence perpetration. Journal of Adolescent Health, 65(1), 86–93. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boynton M., Arkes J., Hoyle R. (2011). Brief report of a test of differential alcohol risk using sibling attributions of paternal alcoholism. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 72(6), 1037–1040. 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury-Jones C., Aveyard H., Herber O., Isham L., Taylor J., O’Malley L. (2021). Scoping reviews: The PAGER framework for improving the quality of reporting. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 25(4), 457–470. [Google Scholar]

- Bramlett M., Radel L. (2014). Adverse family experiences among children in nonparental care, 2011-2012. National Health Statistics Reports, 74(4), 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D., Anda R., Tiemeier H., Edwards V., Croft J., Giles W. (2009). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 37(5), 389–396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley H., Holt S., Whelan S. (2007). Listen to Me! Children’s experiences of domestic violence. Child Abuse Review, 16(5), 296–310. [Google Scholar]

- Buist K., Deković M., Prinzie P. (2013). Sibling relationship quality and psychopathology of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 33, 97–106. https://doi.org/0.1016/j.cpr.2012.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussemakers C., Kraaykamp G., Tolsma J. (2019). Co-occurance of adverse childhood experiences and its association with family characteristics. A latent class analysis with Dutch population data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 98, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button D., Gealt R. (2010). High risk behaviors among victims of sibling violence. Journal of Family Violence, 25, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Caffaro J., Conn-Caffaro A. (2005). Treating sibling abuse families. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(5), 604–623. [Google Scholar]

- Callaghan J., Alexander J., Sixsmith J., Fellin L. (2016). Children’s experiences of domestic violence and abuse: Siblings’ accounts of relational coping. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 21(4), 649–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson B. (2011). Sibling incest: Adjustment in adult women survivors. Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 92(1), 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson B., Maciol K., Schneider J. (2006). Sibling incest: Reports from forty-one survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 15(4), 19034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel Y. (2019). The experience of “nothingness” among children exposed to interparental violence. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 24(5–6), 473–494. [Google Scholar]

- Cashmore J., Parkinson P. (2008). Children’s and parents’ perceptions on children’s participation in decision making after parental separation and divorce. Family Court Review, 46(1), 91–104. [Google Scholar]

- Celbis O., Ozcan E., Ozdemir B. (2006). Paternal and sibling incest: A case report. Journal of Clinical Forensic Medicine, 13(1), 37–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman D., Whitfield C., Felitti V., Dube S., Edwards V., Anda R. (2004). Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. Journal of Affective Disorders, 82(2), 217–225. 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. K., Wang D., Jackson A. P. (2019). Adverse experiences in early childhood and their longitudinal impact on later behavioral problems of children living in poverty. Child Abuse and Neglect, 98(August), 104181. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civitci N., Civitci A., Fiyakali N. (2009). Loneliness and life satisfaction in adolescents with divorced and non-divorced parents. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 9(2), 513–525. [Google Scholar]

- Crouch E., Probst J. C., Radcliff E., Bennett K. J., McKinney S. H. (2019). Prevalence of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) among US children. Child Abuse and Neglect, 92(January), 209–218. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damashek A., Bonner B. (2010). Factors related to sibling removal after a child maltreatment fatality. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34(8), 563–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies H. (2015). Shared parenting or shared care? Learning from children’s experiences of a post-divorce shared care arrangement. Children & Society, 29(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Desir M., Karatekin C. (2018). Parental reactions to parent- and sibling-directed aggression within a domestic violence context. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(3), 457–470. 10.1177/1359104518755219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube S., Felitti V., Dong M., Chapman D., Giles W., Anda R. (2003). Childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction and the risk of illicit drug use: The adverse childhood experiences study. Pediatrics, 111(3), 564–572. 10.1542/peds.111.3.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke N., Pettingell S., McMorris B., Borowsky I. (2010). Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics, 125(4), 778–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards R., Hadfield L., Lucey H., Mauthner M. (2006). Sibling identity and relationships: Sisters and brothers. London. [Google Scholar]

- Exley R. (2021). Understanding sibling relationships in the context of gender diversity. [Google Scholar]

- Falcão V., Jardim P., Dinis-Oliveira R., Magalhães T. (2014). Forensic evaluation in alleged sibling incest against children. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 23(7), 755–767. 10.1080/10538712.2014.949394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnfield S. (2017). Fix my child: The importance of including siblings in clinical assessments. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(3), 421–435. 10.1177/1359104517707995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti V., Anda R., Nordenberg D., Williamson D., Spitz A., Edwards V., Koss M., Marks J. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The adverse childhood experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 774–786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D. (2020). Trends in adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) in the United States. Child Abuse and Neglect, 108, 104641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D., Ormrod R., Turner H. (2009). The developmental epidemiology of childhood victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(5), 711–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foroughe M., Muller R. (2014). Attachment-based intervention strategies in family therapy with survivors of intro-familial trauma: A case study. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 539–548. [Google Scholar]

- Frank H. (2008). The influence of divorce on the relationship between adult parent-child and adult sibling relationships. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 48, 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Garner A. (2013). Home visiting and the biology of toxic stress: Opportunities to address early childhood adversity. Pediatrics, 132(2), S65–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatins D., Kinlaw C., Dunlap L. (2014). Impact of postdivorce sibling structure on adolescent adjustment to divorce. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 55(3), 239–251. [Google Scholar]

- Geschiere M., Spijkerman R., de Glopper A. (2017). Risk of psychosocial problems in children whose parents receive outpatients substance abuse treatment. International Journal of Child, Youth and Family Studies, 8(2), 11–36. [Google Scholar]

- Gilligan M., Stocker C., Conger K. (2020). Sibling relationships in adulthood: Research findings and new frontiers. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12, 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton-Giachritsis C., Browne K. (2005). A retrospective study of risk to siblings in abusing families. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(4), 619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves M. B., Verbitsky-Savitz N., Coffee-Borden B., Perreras L., White C. R., Pecora P. J., Morgan G., Barila T., Ervin A., Case L., Hunter R., Adams K. (2017). Advancing the measurement of collective community capacity to address adverse childhood experiences and resilience. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 142–153. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heins M., Simons C., Lataster T., Pfeifer S., Versmissen D., Lardinois M., Marcelis M., Delespaul P., Krabbendam L., van Os J., Myin-Germeys I. (2011). Childhood trauma and psychosis: A case-control and case-sibling comparison across different levels of genetic liability, psychopathology, and type of trauma. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1286–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindle D. (2007). Clinical research: a psychotherapeutic assessment model for siblings in care. Journal of Child Psychotherapy, 33(1), 70–93. [Google Scholar]

- Hines D., Kantor G., Holt M. (2006). Similarities in siblings’ experiences of neglectful parenting behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 30(6), 619–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman K., Kiecolt K., Edwards J. (2005). Physical violence between siblings a theoretical and empirical analysis. Journal of Family Issues, 26(8), 1103–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingsworth J., Glass J., Heisler K. (2008). Empathy deficits in siblings of severely scapegoated children: A conceptual model. Journal of Emotional Abuse, 7(4), 69–88. [Google Scholar]

- Horn S., Hunter E., Graham-Bermann S. (2013). Differences and similarities in pairs of siblings exposed to intimate partner violence: A clinical case study. Partner Abuse, 4(2), 274–286. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes M., Tucker W. (2018). Poverty as an adverse childhood experience. North Carolina Medical Journal, 79(2), 124–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs K., Sillars A. (2012). Sibling support during post-divorce adjustment: An idiographic analysis of support forms, functions, and relationship types. Journal of Family Communication, 12, 167–187. [Google Scholar]

- Jernbro C., Otterman G., Lucas S., Tindberg Y., Janson S. (2017). Disclosure of child physical abuse and perceived adult support among Swedish adolescents. Child Abuse Review, 26(6), 451–464. 10.1002/car.2443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Joyal C., Carpentier J., Martin C. (2016). Discriminant factors for adolescent sexual offending: On the usefulness of considering both victim age and sibling incest. Child Abuse & Neglect, 54, 10–22. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz C., Hamama L. (2017). From my own brother in my own home: Children’s experiences and perceptions following alleged sibling incest. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(23), 3648–3668. 10.1177/0886260515600876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye-Tzadok A., Davidson-Arad B. (2016). Posttraumatic growth among women survivors of childhood sexual abuse: Its relation to cognitive strategies, posttraumatic symptoms, and resilience. Psychological Trauma, 8(5), 550–558. 10.1037/tra0000103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane M., Guest A., Padbury J. (2013). A balancing act: A family perspective to sibling sexual abuse. Child Abuse Review, 22(4), 246–254. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Kim E. (2019). Bullied by siblings and peers: The role of rejecting/neglecting parenting and friendship quality among Korean children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(11), 2203–2226. 10.1177/0886260516659659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiselica M., Morrill-Richards M. (2007). Sibling maltreatment: The forgotten abuse. Journal of Counselling & Development, 85, 148–161. [Google Scholar]

- Kothari B., McBeath B., Sorenson P., Bank L., Waid J., Webb S., Steele J. (2017). An intervention to improve sibling relationship quality among youth in foster care: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 19–29. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krienert J., Walsh J. (2011). Sibling sexual abuse: An empirical analysis of offender, victim, and event characteristics in National Incident-Based Reporting System (NIBRS) data, 2000–2007. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse: Research, Treatment, & Program Innovations for Victims, Survivors, & Offenders, 20(4), 353–372. 10.1080/10538712.2011.588190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang C., Cox M., Flores G. (2013). Maltreatment in multiple-birth children. Child abuse & neglect, 37(12), 1109–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leban L., Gibson C. L. (2019). The role of gender in the relationship between adverse childhood experiences and delinquency and substance use in adolescence. Journal of Criminal Justice, 66(August 2019), 101637. 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2019.101637 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O'Brien K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5, 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindberg D., Shapiro R., Laskey A., Pallin D., Blood E., Berger R.; ExSTRA Investigators. (2012). Prevalence of abusive injuries in siblings and household contacts of physically abused children. Pediatrics, 130(2), 193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo H. P. W., Lau V. W. Y., Yu E. S. M. (2017). Clinical characteristics and developmental Profile of child abuse victims assessed at child assessment service in Hong Kong: A five-year retrospective study. Hong Kong Journal of Paediatrics, 22, 88–96. [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan H., Tanaka M., Duku E., Vaillancourt T., Boyle M. (2013). Child physical and sexual abuse in a community sample of young adults: Results from the Ontario child health study. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(1), 14–21. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manyema M., Richter L. M. (2019). Adverse childhood experiences: Prevalence and associated factors among South African young adults. Heliyon, 5(12), e03003. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e03003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C., Martinez K. (2017). Victims’ retrospective explanations of sibling sexual violence. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(7), 874–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald C., Martinez K. (2019). Victim narratives of sibling emotional abuse. Child Welfare, 97(2), 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey T., Haen C. (2005). Intervention strategies for treating traumatized siblings on a pediatric inpatient unit. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(3), 395–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munn Z., Peters M., Stern C., Tufanaru C., McArthur A., Aromataris E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18, 143. 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyers A. (2014). A call to child welfare: Protect children from sibling abuse. Qualitative Social Work, 13(5), 654–670. [Google Scholar]

- Milevsky A. (2011). Sibling relationships in childhood and adolescence: Predictors and outcomes. Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Miller L., Grabell A., Thomas A., Bermann E., Graham-Bermann S. (2012). The associations between community violence, television violence, intimate partner violence, parent-child aggression, and aggression in sibling relationships of a sample of preschoolers. Psychology of Violence, 2, 165–178. [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G.; The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PloS Medicine, 6(7), 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrill M. (2014). Sibling sexual abuse: An exploratory study of long-term consequences for self-esteem and counseling considerations. Journal of Family Violence, 29(2), 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Morrill M., Schulz M., Nevarez M., Preacher K., Waldinger R. (2019). Assessing within-and between-family variations in an expanded measure of childhood adversity. Psychological Assessment, 31(5), 660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller P., Feeney J., Sheehan G., Darlington Y., Rogers C. (2008). Conflict in divorcing and continuously married families: A study of marital, parent-child and sibling relationships. Journal of Divorce and Marriage, 28(1–2), 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Peters M. D. J., Godfrey C. M., Khalil H., McInerney P., Parker D., Soares C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(1), 141–146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips D., Bowie B., Wan D., Yukevich K. (2018). Sibling violence and children hospitalized for serious mental and behavioral health problems. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(16), 2258–2578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski C. (2011). Patterns of adjustment among siblings exposed to intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Psychology, 25(1), 19–28. 10.1037/a0022428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piotrowski C., Tailor K., Cormier D. (2014). Siblings exposed to intimate partner violence: Linking sibling relationship quality & child adjustment problems. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(1), 123–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner L., Boel-Studt S. (2017). Physical family violence and externalizing and internalizing behaviors among children and adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 87(4), 474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renner L., Driessen M. (2019). Siblings who are exposed to child maltreatment: Practices reported by county children’s services supervisors. Journal of Public Child Welfare, 13(5), 491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Ronel N., Haimoff-Ayali R. (2010). Risk and resilience: The family experience of adolescents with an addicted parent. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 54(3), 448–472. 10.1177/0306624X09332314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Kuay H., Lee S., Centifanti L., Parnis A., Mrozik J., Tiffin P. (2016). Adolescents as perpetrators of aggression within the family. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry, 47, 60–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J., Boyce T., McEwen B. (2009). Neuroscience, molecular biology, and childhood roots of health disparities: Building a new framework for health promotion and disease prevention. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301(21), 2252–2259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shonkoff J., Garner A., Siegel B., Dobbins M., Earls M., McGuinn L., Pascoe J., Wood D. (2012). The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics, 129, 232–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skopp N., McDonald R., Manke B., Jouriles E. (2005). Siblings in domestically violent families: Experiences of interparent conflict and adjustment problems. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler L., Forns M., Kirchner T., Segura A. (2015). Relationship between particular areas of victimization and mental health in the context of multiple victimizations in Spanish adolescents. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(4), 417–425. 10.1007/s00787-014-0591-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sporer K. (2019). Aggressive children with mental illness: A conceptual model of family-level outcomes. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(3), 447–474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tailor K., Stewart-Tufescu A., Piotrowski C. (2015). Children exposed to intimate partner violence: Influences of parenting, family distress, and siblings. Journal of Family Psychology, 29(1), 29–38. 10.1037/a0038584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarshish N., Tener D. (2019). Exemption committees as an alternative to legal procedure in cases of sibling sexual abuse: The approaches of Israeli CAC professionals. Child Abuse & Neglect, 105, 104088. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedgård E., Råstam M., Wirtberg I. (2019). An upbringing with substance-abusing parents: Experiences of parentification and dysfunctional communication. Nordisk Alkohol Nark, 36(3), 223–247. 10.1177/1455072518814308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tener D., Lusky E., Tarshish N., Turjeman S. (2018). Parental attitudes following disclosure of sibling sexual abuse: A child advocacy center intervention study. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 88(6), 661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tener D., Newman A., Yates P., Tarshish N. (2019). Child advocacy center intervention with sibling sexual abuse cases: Cross-cultural comparison of professionals’ perspectives and experiences. Child Abuse & Neglect, 105, 104259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tener D., Silberstein M. (2019). Therapeutic interventions with child survivors of sibling sexual abuse: The professionals’ perspective. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 192–202. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippett N., Wolke D. (2015). Aggression between siblings: Associations with the home environment and peer bullying. Aggressive Behavior, 41(1), 14–24. 10.1002/ab.21557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tompsett C., Mahoney A., Lackey J. (2018). Sibling aggression among clinic-referred children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 47(6), 941–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco A. C., Lillie E., Zarin W., O’Brien K. K., Colquhoun H., Levac D., Moher D., Peters M. D., Horsley T., Weeks L., Hempel S. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169, 467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker C., Finkelhor D., Turner H., Shattuck A. (2013). Association of sibling aggression with child and adolescent mental health. Pediatrics, 132(1), 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker C., Finkelhor D., Turner H., Shattuck A. (2014). Sibling and peer victimization in childhood and adolescence. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(10), 1599–1606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Berkel S., Tucker C., Finkelhor D. (2018). The combination of sibling victimization and parental child maltreatment on mental health problems and delinquency. Child Maltreatment, 23(3), 244–253. 10.1177/1077559517751670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasquez M., Stensland M. (2015). Adopted children with reactive attachment disorder: A qualitative study on family processes. Clinical Social Work Journal, 44, 319–332. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeulen T., Greeff A. (2015). Family resilience resources in coping with child sexual abuse in South Africa. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 24(5), 555–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte S., Fegert J., Walper S. (2018). Risk of maltreatment for siblings: Factors associated with similar and different childhood experiences in a dyadic sample of adult siblings. Child Abuse & Neglect, 76, 321–333. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe J. (2016). The effects of maternal alcohol use disorders on childhood relationships and mental health. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51, 1439–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward T., Copp J. (2016). Maternal incarceration and children’s delinquent involvement: The role of sibling relationships. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Yucel D., Yuan A. (2015). Do siblings matter? The effect of siblings on socio-emotional development and educational aspirations among early adolescents. Child Indicators Research, 8, 671–697. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-tva-10.1177_15248380221134289 for Sibling Experiences of Adverse Childhood Experiences: A Scoping Review by Ben Donagh, Julie Taylor, Muna al Mushaikhi and Caroline Bradbury-Jones in Trauma, Violence, & Abuse