Abstract

Fe–S clusters are essential cofactors mediating electron transfer in respiratory and metabolic networks. However, obtaining active [4Fe-4S] proteins with heterologous expression is challenging due to (i) the requirements for [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly, (ii) the O2 lability of [4Fe-4S] clusters, and (iii) copurification of undesired proteins (e.g., ferredoxins). Here, we established a facile and efficient protocol to express mature [4Fe-4S] proteins in the PURE system under aerobic conditions. An enzyme aconitase and thermophilic ferredoxin were selected as model [4Fe-4S] proteins for functional verification. We first reconstituted the SUF system in vitro via a stepwise manner using the recombinant SUF subunits (SufABCDSE) individually purified from E. coli. Later, the incorporation of recombinant SUF helper proteins into the PURE system enabled mRNA translation-coupled [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly under the O2-depleted conditions. To overcome the O2 lability of [4Fe-4S] Fe–S clusters, an O2-scavenging enzyme cascade was incorporated, which begins with formate oxidation by formate dehydrogenase for NADH regeneration. Later, NADH is consumed by flavin reductase for FADH2 regeneration. Finally, bifunctional flavin reductase, along with catalase, removes O2 from the reaction while supplying FADH2 to the SufBC2D complex. These amendments enabled a one-pot, two-step synthesis of mature [4Fe-4S] proteins under aerobic conditions, yielding holo-aconitase with a maximum concentration of ∼0.15 mg/mL. This renovated system greatly expands the potential of the PURE system, paving the way for the future reconstruction of redox-active synthetic cells and enhanced cell-free biocatalysis.

Keywords: Fe−S cluster, reconstituted cell-free protein synthesis, aconitase, cofactor regeneration, SUF helper protein, redox enzymes

Introduction

Iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters are essential prosthetic groups of many redox-active proteins and are employed by organisms across all three domains of life, serving as electron shuttles in a variety of metabolic and respiratory networks.1−4 Among multiple Fe–S stoichiometries and coordination, the cubane-type [4Fe-4S] cluster is associated with the lowest reported standard reduction potential down to −645 mV, depending on pH.5,6 [4Fe-4S] proteins play essential roles in central carbon metabolism, N2 fixation, H2 respiration, organohalide respiration, the biogeochemical sulfur cycle, and C1 metabolism.7−12 Biogenesis of [4Fe-4S] clusters is a complex process involving multiple maturases with long evolutionary histories.13 In bacteria, the assembly process follows a scheme of (i) the extraction of the sulfide group from the precursor cysteine; (ii) the assembly of the [4Fe-4S] cluster on a scaffold; and (iii) the transfer of the [4Fe-4S] cluster to recipient proteins.14 This scheme can be accomplished by three types of helper protein systems: NIF (nitrogen fixation), ISC (iron-sulfur cluster), and SUF (mobilization of sulfur). The NIF system is responsible for the cubane-type Fe–S cluster assembly of nitrogenase for N2 fixation,15 while the ISC system is the primary system for Fe–S cluster assembly in bacteria.16 The third Fe–S cluster assembly system, the SUF system, is more O2-tolerant and is activated when cells suffer from iron starvation and oxidative stress.17−19 The SUF system is encoded by the suf operon (sufABCDSE). The encoded SUF subunits are assembled into two complexes: SufSE and SufBC2D. The SufS-SufE pair extracts S2– from cysteine; the SufBC2D complex acts as a scaffold, receiving the S2– group from the SufES complex and incorporating Fe2+/3+ for Fe–S cluster assembly, which is an ATP- and FADH2-consuming process;20 the SufA is a Fe–S cluster carrier protein that transfers the Fe–S clusters to the recipient proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the SUF pathway. The SufBC2D complex acts as a scaffold, receiving the sulfide (S2–) group from the SufES complex and incorporating Fe2+ and/or Fe3+ depending on the type of cluster for Fe–S cluster assembly.19 FADH2 is used for Fe3+ reduction and [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly is driven by ATP hydrolysis. The assembled [4Fe-4S] cluster is then transferred to the SufA, which further transfers the cluster to the recipient proteins.

Mature [4Fe-4S] proteins have been purified from cells across the tree of life.21,22 However, due to the O2 lability of [4Fe-4S] clusters, the expression and purification of mature [4Fe-4S] proteins often needs to be performed under strictly anaerobic and highly reduced conditions.23 Moreover, purified [4Fe-4S] proteins are often contaminated by ferredoxins (Fd) due to the high affinity of submicromolar KD concentrations.24 An alternative method for [4Fe-4S] protein maturation is to reconstitute the [4Fe-4S] clusters chemically. For example, the Clostridial apo-Fd was reconstituted into holo-form by incubating apo-Fd with 2-mercaptoethanol, S2–, and Fe2+/3+ under anaerobic and alkaline conditions.25 The traditional chemical reconstitution method has been applied to reconstitute many Fe–S proteins in vitro and has reached a level of refinement.26,27

Cell-free protein synthesis systems have emerged as a powerful tool for high-throughput protein expression.28−31 These cell-free systems are flexible, enabling the adjustment of the environmental conditions to produce correctly folded proteins with cofactors,32 and allow the functional expression of enzymes, membrane structural proteins, toxic proteins, and de novo-designed polypeptides with high homogeneity. Furthermore, cell-free systems enable protein expression from linear DNA, bypassing the procedures of plasmid cloning and microbe culturing that often cause sequence mutations. Cell lysate-based cell-free systems are easily prepared, robust, and economical, suitable for large-scale, high-yield protein synthesis and high-throughput mRNA translation,31 while the reconstituted cell-free systems (i.e., the PURE systems) allow protein synthesis in an environment free of proteases, nucleases, and any undefined contaminated components, suitable for biochemical characterization of complex metabolic networks and the bottom-up reconstruction of synthetic cells.28,33,34

Previously, the Swartz group established the protocols for synthesizing mature [2Fe-2S] Fd in a cell extract-based cell-free system (S30) with a high yield of 0.45 mg per mL and a maturation efficacy of ∼85%.35 Interestingly, coexpression of the ISC helper proteins in the cells used for cell-extract preparation did not facilitate mature [2Fe-2S] Fd assembly, likely due to the limited ISC expression and activity in host cells under aerobic conditions. Cell-free synthesis of [FeFe] hydrogenase that contains the cubane-type [4Fe-4S] cluster was also attempted by the same group; nevertheless, the maturation efficacy of holo-[FeFe] hydrogenase (44%) was much lower than the [2Fe-2S] Fd even in the presence of the HydEFG helper proteins.36 Due to the O2 lability of [4Fe-4S] clusters, the cell-free hydrogenase expression and purification were performed under anaerobic conditions, along with the addition of strong reductants to prevent loss of function upon O2 exposure.

Results and Discussion

In this study, we investigated the expression of mature [4Fe-4S] proteins using the PURE system (PUREfrex) and the SUF helper protein system. Ideally, the synthesis of [4Fe-4S] proteins would be possible under aerobic conditions, alleviating the need for complex anaerobic systems. The PUREfrex already includes an efficient ATP regeneration system which can also be used to drive SUF-mediated [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly.37 To supply FADH2 to the SUF system and to overcome the O2 lability of [4Fe-4S] clusters, we designed an O2-scavenging cascade including formate dehydrogenase (FDH), NADH-dependent flavin reductase (FRE), and catalase (CAT) to (i) sequentially regenerate FADH2 from formate via NADH and (ii) scavenge the dissolved O2.

Stepwise in Vitro Reconstitution of the SUF System from Individually Purified SUF Subunits

We first sought to reconstitute the SUF system in vitro in a stepwise manner using the recombinant SUF subunits individually purified from E. coli (Figure S1). According to the literature, the first step in the SUF-mediated Fe–S cluster assembly is S2– extraction from cysteine by the SufES complex.38 Indeed, we observed S2– accumulation in reactions when both cysteine and recombinant SufES were added (Figure 2A). Next, we tried to validate the activities of the recombinant SufBC2D complex in vitro, because previous works generally coexpressed the sufBCD and directly purified the mature SufBC2D complex from the host via multistep liquid chromatography.39 [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly on the SufBC2D complex can be inferred from the increase in the characteristic optical absorbance of [4Fe-4S] clusters at 420 nm.40 We first reconstituted the SufBC2D complex under anaerobic conditions. Notably, a small initial amount of [4Fe-4S] cluster was observed (Figure 2B) and the λ420 nm of the reconstituted SufBC2D complex decreased after aeration. We then incubated the oxidized SufBC2D complex with cysteine, Fe2+/3+, ATP, FADH2 (reduced by dithionite), and the recombinant SufES under anaerobic conditions and observed a time-course increase in the λ420 nm (Figure 2C). Moreover, the increase in λ420 nm was not observed in the assays devoid of the recombinant SufES (Figure 2D), suggesting that the recombinant SufBC2D complex, along with SufES, is capable of assembling [4Fe-4S] clusters in vitro under anaerobic conditions. It is worthwhile mentioning that adding a low Fe2+/3+ concentration (<0.1 mM) in the assays prevents the formation of blackish FeS,41 which is required for optical measurement in the absence of turbidity (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Anaerobic [4Fe-4S] cluster reconstitution using the SUF system. (A) Cysteine desulfurase activity of the SufES complex was measured with and without SufS or SufE. Free S2– production was measured based on the time-dependent production of methylene blue (λ670 nm). The bars represent the range and the data points represent the average from two independent experimental replicates, respectively. (B) Observation of [4Fe-4S] clusters (λ420 nm) degradation on the reconstituted SufBC2D complex after a 10 min aeration. (C,D) SUF-mediated [4Fe-4S] assembly was conducted with the oxidized SufBC2D complex in the (C) presence or (D) absence of SufES under anaerobic conditions.

Next, we validated whether the recombinant SufA is capable of transferring [4Fe-4S] clusters from the SufBC2D complex to the recipient proteins in vitro. A thermotolerant [4Fe-4S] Fd from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Thermococcus profundus was used as [4Fe-4S] cluster recipient protein.42 Cytochrome C reduction by Fd was followed at λ550 nm, with electrons supplied by a ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase system for Fd reduction (Figure S3A).35 Often purified [4Fe-4S] Fd results in contaminated Fd-binding proteins, whereas the thermotolerance of Thermococcus Fd allows a single-step purification by heating at 92 °C for 10 min (Figure S1). Accordingly, we heterologously expressed and purified holo-Fd from anaerobically cultivated E. coli cultures. Following a chemical reconstitution to fully mature the recombinant Fd (Figure S4A), the brown-colored holo-Fd preparations with a defined gradient of concentrations were used to establish the optical cytochrome C reduction assay (Figure S3BC).

Subsequently, we synthesized and purified the recombinant apo-Fd using the PUREfrex free of the SUF system and Fe2+/3+ under aerobic conditions. The recombinant apo-Fd was incubated with the recombinant SufBC2D complex charged with [4Fe-4S] clusters (Figure 2C) with and without Fe2+, cysteine, or the recombinant apo-Fd (Figure S3C). The background activities observed in the negative controls could result from either (i) the trace holo-Fd contamination in the commercial spinach ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (Km of Fd < 3 μM) used for Fd reduction in the cytochrome C reduction assays;43 and (ii) the chemical reduction by reductants (e.g., Na2S and DTT). These data suggested that the reconstituted SUF system (SufABCDSE) can likely mature apo-[4Fe-4S] proteins in vitro.

To gain a more definite answer, we also used PUREfrex to produce the apo-form of E. coli aconitase A (AcnA). The maturation of the SUF system can be validated by an NADP-dependent optical assay (λ340 nm) (Figure S5A) where isocitrate, the product of aconitase, is converted to alpha-ketoglutarate by the NADP-dependent isocitrate dehydrogenase, with holo-AcnA purified from anaerobically cultivated E. coli cultures as the standard (fully reconstituted via the chemical method) (Figures S4B, S5B,C). Apo-AcnA incubated with the SUF system for 15 min under anaerobic conditions demonstrated an enzyme activity of ∼90% of holo-AcnA activity. No aconitase activity was observed in the reactions without apo-AcnA or the mature SUF (Figure 3A). Moreover, the apo-AcnA incubated with the anaerobically reconstructed SUF system but without SufA demonstrated reduced enzyme activity (∼70%). Furthermore, no aconitase activity was observed when the apo-AcnA was incubated with either heat-denatured SufBC2D complex or S2– for 15 min, suggesting that the [4Fe-4S] cluster of holo-AcnA was transferred from the recombinant SUF system but not assembled abiotically under the reduced conditions (Figure 3B). Together, our data revealed that the recombinant SufBC2D complex is capable of assembling and subsequently transferring the [4Fe-4S] clusters to the recipient proteins with limited efficiency in vitro under anaerobic conditions, and the efficiency can be enhanced by adding the recombinant SufA.

Figure 3.

[4Fe-4S] cluster transfer from mature SufBC2D complex to apo-AcnA. (A) Apo-AcnA maturation by the SUF system reconstructed under anaerobic and aerobic conditions created by enzymatic O2-scavenging system (see later section). (B) Anaerobic holo-AcnA synthesis using mature SUF, heat-denatured SUF system, or S2–. The reconstitution efficiency of holo-AcnA is evaluated as a function of the relative enzymatic activity to that of the fully chemically reconstituted AcnA using an isocitrate dehydrogenase activity assay (see Supporting Methods). The bars represent the standard deviations. The dots and columns represent the individual values and mean from three independent experimental replicates, respectively.

A Bifunctional O2-Scavenging Enzyme Cascade Enabling Aerobic [4Fe-4S] Cluster Assembly

Following in vitro reconstitution of the mature SUF system under anaerobic conditions, we then worked to overcome the O2 lability of [4Fe-4S] clusters by amendment with an O2-scavenging system. Inherent from the O2-lability of [Fe–S] proteins, several enzymatic O2-scavenging approaches have been developed during the past few decades. Catalase, glucose oxidase, and protocatechuate dioxygenase represent the most common O2-scavenging enzymes.44,45 However, in our case, their substrates/products (i.e., gluconolactone and protocatechuate, respectively) are UV–vis active, which affects the optical analysis for monitoring the [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly. Recently, bilirubin oxidase has been used as a single-enzyme O2-scavenger without H2O2 generation.46 Unfortunately, bilirubin (red) and the oxidized product biliverdin (green) also affect the optical analysis of the [4Fe-4S] clusters. Interestingly, the NADH-dependent flavin reductase (FRE) required for FADH2 regeneration in the SUF system can also scavenge O2 to form H2O2.47 Working with catalase (CAT), the translucent FADH2 can sequentially reduce the level of O2 to H2O via H2O2 (O2 + 2 FADH2 → 2 H2O + 2 FAD). Therefore, we employed flavin reductase and catalase for O2-scavenging. The NADH required for FADH2 regeneration was supplied by the NAD+-dependent formate dehydrogenase (FDH) using formate as the donor of reducing equivalent (Figure 4A).48 Accordingly, we have purified E. coli FRE/CAT and Pseudomonas FDH (Figure S1) to test if this bifunctional three-enzyme cascade can function in the buffer system of the PUREfrex. We measured time-course NAD+ reduction (λ340 nm) by adding both formate and formate dehydrogenase to the PUREfrex buffer (Figure S6AB). The addition of both flavin reductase and FAD to the PUREfrex buffer resulted in a time-course FAD reduction (λ445 nm) (Figures 4B and S6C), and the yellow color of the PUREfrex buffer gradually faded away to become translucent. The same reaction mixture with catalase addition demonstrated a delayed FAD reduction compared to the catalase-free mixture, suggesting FADH2 was recycled back to FAD. Likely, the produced FADH2 was mainly consumed for O2 degradation in the catalase-added PUREfrex buffer in the first 8 min. Together, these data suggest that the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade can sustain continuous FADH2 regeneration in the PUREfrex buffer system under aerobic conditions.

Figure 4.

The bifunctional enzyme cascade for FADH2 regeneration and O2 scavenge. (A) Schematic diagram showing the bifunctional O2-scavenging enzyme cascade. (B) FADH2 production was monitored by a time-dependent decrease in λ445 nm (0–10 min). The reactions were conducted with and without catalase (CAT), flavin reductase (FRE), or FAD. (C) The anaerobicity of the reaction mixture was evaluated by an oxidation–reduction indicator, resorufin. The bars represent the standard deviation. The dots and columns represent the individual value and mean from three independent experimental replicates, respectively.

Next, we employed resorufin, a sensitive fluorescent O2 indicator, to assess the O2-scavenging capability of the O2-scavenging cascade. Under reduced conditions (i.e., dissolved O2 removed), the pink-colored and highly fluorescent resorufin would undergo a reversible reduction to form the nonfluorescent dihydroresorufin (standard reduction potential ∼ −51 mV).49 Consistent with the consumption of O2, the PUREfrex buffer with the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade demonstrated a fluorescence emission (λ590 nm) much lower than reactions devoid of either flavin reductase or FAD (Figure 4C). Moreover, the fluorescence emission of the PUREfrex buffer amended with the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade is comparable to that of the titanium citrate-reduced reactions. These data suggested a faster rate of O2 scavenging by the enzyme cascade than the rate of diffusion of the O2 into the PUREfrex buffer. Therefore, we amended this O2-scavenging enzyme cascade to the SUF-incorporated PUREfrex buffer and performed the SUF-mediated [4Fe-4S] assembly in vitro under aerobic conditions. After 30 min of incubation, the color of SUF-incorporated PUREfrex buffer turned brown, along with an obvious increase in the characteristic optical absorbance of [4Fe-4S] clusters at λ420 nm, comparable to that of the SUF-incorporated PUREfrex buffer incubated anaerobically (Figure 5A). Furthermore, the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade also protected the [4Fe-4S] cluster from oxidation under aerobic conditions for at least 1.5 h, while the absence of the enzyme cascade resulted in a rapid oxidation of the [4Fe-4S] cluster in the first 30 min (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

The bifunctional O2-scavenging enzyme cascade enables SUF-mediated [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly under aerobic conditions. (A) The SUF-mediated [4Fe-4S] assembly (based on the increase in λ420 nm) with and without the O2-scavenging system under aerobic conditions. (B) The bifunctional O2-scavenging enzyme cascade protects the [4Fe-4S] cluster from oxidation (based on the decrease in λ420 nm) under aerobic conditions. The degradation and formation of [4Fe-4S] clusters were monitored by the UV–vis spectrophotometric analysis (280–700 nm).

The combination of the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade and the SUF system enabled in vitro [4Fe-4S] cluster reconstitution under aerobic conditions. We have also shown that mature SUF reconstituted using O2-scavanging system can also support Apo-AcnA maturation (Figure 3A). In E. coli, flavin reductase FRE is the main enzyme responsible for FMNH2/FADH2 regeneration, i.e., the native enzyme supporting the [4Fe-4S] cluster assembly by the SufBC2D complex.20,47 Moreover, our O2-scavenging system only employs a low FAD concentration (∼20 μM) comparable to the intracellular FMN/FAD concentration in E. coli.50 One can be envisaged that such a biomimetic system for [4Fe-4S] protein maturation would be suitable and compatible to reconstruct the cell-wide metabolic networks in both cell extract-based and reconstituted cell-free systems. Going further, the required O2-scavenging capacity, which is proportional to the formate concentration, can be estimated based on the ideal gas law (pv = nRT), atmospheric O2 content (20%), and Henry’s law constant of O2 (Haq/gas = 0.032). For example, since our PUREfrex reactions were performed in a capped 0.3 mL reaction tube with 0.1 mL of the headspace of the atmosphere, the amount of O2 in the PUREfrex reactions would be ∼0.9 μmol/tube (see the detailed calculation in Table S1). Given that the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade reduces each O2 molecule at the cost of two FADH2, complete O2 removal would require ∼1.8 μmol (9 mM) of FADH2 (i.e., formate). Excessive formate addition to the system, while securing the anaerobicity, would result in a drastic pH shift.

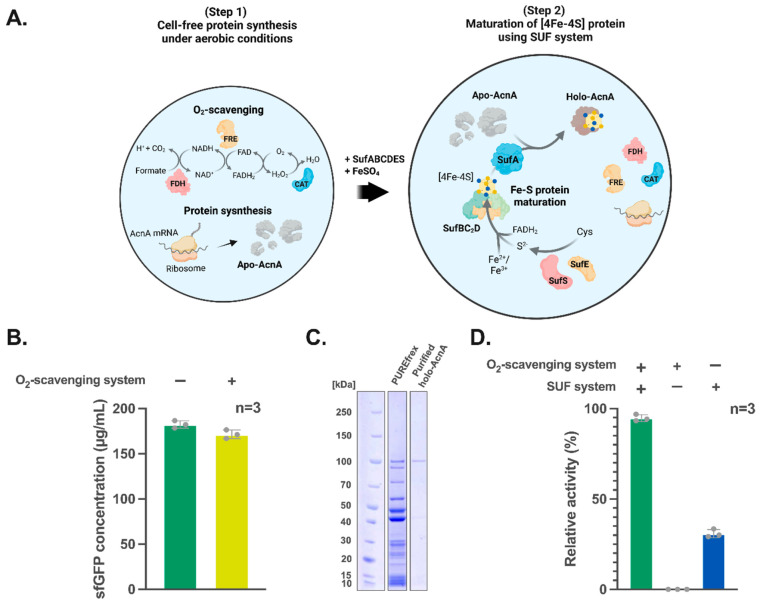

One-Pot, Two-Step Cell-Free Synthesis of Active Aconitase under Aerobic Conditions

Finally, we tested the possibility of combining the processes of mRNA translation, O2 scavenging, and [4Fe-4S] cluster maturation into a one-pot process. Due to the adverse effects of S2– (metal precipitation) and Fe2+ (in-line cleavage of RNA51 and generation of reactive oxygen species) during cell-free translation, we separated the in vitro translation and cluster reconstruction process into two steps (Figure 6A). In step 1, AcnA mRNA was added to the PUREfrex along with the three enzymes for O2-scavenging (FDH/FRE/CAT) to maintain anoxic condition while producing apo-AcnA. In step 2, FeSO4 and SufABCDSE were added to the reactions for the maturation of the apo-AcnA. This two-step process can prevent continuous cysteine desulfurization by SufES that would result in (i) a decrease of available cysteine for mRNA translation and (ii) metal (e.g., Fe2+) precipitation by the S2–.

Figure 6.

One-pot de novo synthesis of mature [4Fe-4S] protein under aerobic conditions. (A) Schematic diagram showing one-pot two-step cell-free synthesis of mature [4Fe-4S] cluster bearing AcnA under aerobic conditions. In vitro translation of AcnA mRNA is carried out in a test tube along with the three O2-scavanging enzymes (Step 1). FeSO4 and SUF components are further added to drive maturation of the apo-AcnA to its holo-form (Step 2). Other required components such as cysteine (Cys) and ATP are carried over from the PUREfrex reaction. (B) Superfolder GFP (sfGFP) production in the PUREfrex reaction mixtures with and without the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade after 6 h of incubation. (C) Purification of holo-AcnA free of N-His6-tag verified by SDS-PAGE analysis. (D) Relative activity of AcnA in the one-pot PURE system with and without the SUF and O2-scavanging system. The bars represent the standard deviations. The dots and columns represent the individual values and mean from three independent experimental replicates, respectively.

For a successful one-pot synthesis, a prerequisite is the compatibility of PUREfrex with the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade. The incompatibility of the two components can lead to a significant reduction of the protein yield. Therefore, we first used the mRNA of superfolder green fluorescent protein (sfGFP) as an indicator of the protein yield in PUREfrex and compared the sfGFP yield of the PUREfrex reactions with and without the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade, respectively. Our data showed that the incorporation of the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade to the PUREfrex only resulted in a reduction of sfGFP yield <5% (Figure 6B), suggesting that the two components are compatible. Another prerequisite is the maturation of the SUF system to provide [4Fe-4S]-charged SufBC2D complex in the O2-scavenged PUREfrex buffer under aerobic conditions (Figure 5A). Accordingly, we translated apo-AcnA mRNA using PUREfrex along with the O2-scavenging system (Figure 6A, Step 1), followed by an addition of SUF components and FeSO4 to generate holo-AcnA (Figure 6B, Step 2). Use of an HRV protease for N-His6-tag removal allowed us to further purify holo-AcnA from other recombinant proteins in the PUREfrex reaction mixture (Figure 6C). The purified holo-AcnA demonstrated a relative enzyme activity of ∼95% to that of the fully chemically matured holo-AcnA (Figure 6D). Moreover, liquid chromatography–mass spectroscopy (LC-MS) analysis revealed concurring citrate consumption and alpha-ketoglutarate production in the assays with AcnA purified from the one-pot, two-step system but not in the assays with AcnA purified from the PUREfrex reactions devoid of the SUF system (Figure S7 and S8). Interestingly, the AcnA produced from the SUF-amended PUREfrex reactions without the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade demonstrated a relative enzyme activity of ∼30% of the aconitase activity (Figure 6D), suggesting that consistent with the observation of previous studies, the SUF system is relatively O2-tolerant. Altogether, these data suggested the successful production of holo-aconitase from the one-pot, two-step process.

Conclusions

Functional expression and purification of [4Fe-4S] proteins have been long-term challenges in biochemical research. In this study, we demonstrated in vitro assembly and transfer of [4Fe-4S] clusters from Fe2+/3+ and S2– from cysteine using the SUF system reconstituted from individually purified SUF subunits. The O2 tolerance of the SUF helper proteins allows facile heterologous expression and purification of each subunit under aerobic conditions and later reconstitution. Interestingly, based on the results of the Thermococcus Fd-mediated cytochrome C reduction assays, the E. coli SUF system seems to be capable of transferring the [4Fe-4S] clusters to [4Fe-4S] proteins from other organisms, suggesting broad applicability of the reconstituted SUF system. In conclusion, the PUREfrex supplied with both the SUF system and the bifunctional O2-scavenging enzyme cascade serves as a facile and efficient platform for synthesizing O2-labile [4Fe-4S] proteins. We anticipate that this renovated PURE system, with the flexibility to be paired with other helper proteins, will facilitate future studies on more challenging [4Fe-4S] proteins, such as FeMoco-dependent nitrogenase, cobalamin-dependent dehalogenases, and NiFeS acetyl-CoA synthase/CO dehydrogenase. Furthermore, although not fully demonstrated in this study, the amendment of the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade also makes the PURE system redox-active. If paired with ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase, the four-enzyme cascade can support the regeneration of all common redox equivalents in cells (Fd, NADPH, cytochrome C, ubiquinone, and FMNH2/FADH2). Therefore, we also foresee the compatibility of this renovated PURE system with the in vitro reconstitution of complex biosynthesis pathways and respiratory networks, likely to the extent of de novo artificial cell reconstruction.

Methods

Methods for heterologous protein expression and purification, in vitro RNA transcription, the optical enzyme activity assays, and analytical chemical methods are shown in the Supporting Information. All experiments requiring the anaerobic environment were performed in a Coy Lab type B vinyl anaerobic chamber with an atmosphere of a 5:95% (v/v) H2:N2 gas mixture. Km and kcat values of the enzymes used in this work are given in Table 1.

Table 1. Km and kcat of the Enzymes Used in This Worka.

| enzyme name | substrate | Km (mM) | kcat (s) | specific activity (μmol/min/mg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isocitrate dehydrogenase | Isocitrate | 0.0075 | 58 | 38 |

| NADP+ | 0.0055 | 32 | ||

| Ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase | NADPH | 0.003 | 250 | – |

| Fd(ox) | 0.05 | 0.15 | ||

| Cysteine desulfurase (SufS) | l-Cysteine | 0.05 | 0.2 | 0.01 |

| Aconitase (AcnA) | Citrate | 1.15 | – | 6.0 |

| Flavin reductase (FRE) | FAD | 0.001 | 40 | – |

| NADH | 0.18 | 40 | ||

| Formate dehydrogenase (FDH) | Formate | 7.5 | 10 | – |

| NAD+ | 0.05 | 7.3 |

The values were referred from the BRENDA database.55

Experimental Materials

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) unless specified otherwise. The PUREfrex reagents were provided by GeneFrontier Corp. (Kashiwa, Chiba, Japan). The pUC57 plasmids carrying the recombinant E. coli SUF proteins, Thermococcus Fd, and the pET-21d(+) plasmid carrying the recombinant E. coli catalase (CAT) were purchased from GenScript Biotech Corporation (Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). The pET-23b(+) plasmid carrying the recombinant Pseudomonas formate dehydrogenase gene is a gift from Prof. Alexander F. Yakunin, Bangor University, United Kingdom.48 The ASKA E. coli clones for aconitase (AcnA) and flavin reductase (FRE) were purchased from the National Institute of Genetics (SHIGEN) (Mishima, Shizuoka, Japan).52 The detailed information for the corresponding recombinant proteins is shown in Table S2.

Gene Cloning

The suf genes (sufA/sufB/sufC/sufD/sufE/sufS) were cloned into a pET-26b(+) expression vector by Seamless ligation cloning extract (SLiCE) cloning,53 while acnA gene was cloned into pET-23a(+) for in vitro transcription. The linearized vector was amplified from the pET-26b(+)/pET-23a(+) plasmid DNA using the appropriate forward and reverse primers. The suf genes were amplified from pUC57 plasmid DNA, while acnA gene was amplified from the corresponding ASKA E. coli clone. Note that the HRV protease-cutting site was inserted between the genes of N-His6-tag and acnA by PCR. All primer sequences are available in Table S2. The SLiCE cloning reaction was performed as described previously.54 Briefly, SLiCE solution (1 μL) and 10× SLiCE buffer (1 μL) were mixed with 60 ng of the inset DNA and 60 ng of the linearized pET-26b(+) vector (C-His6 tag removed by PCR), and the final volume of the SLiCE reaction was adjusted to 10 μL using sterilized ddH2O. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min to produce the pET-26b(+)-SufA/SufB/SufC/SufD/SufE/SufS and pET-23a(+)-AcnA plasmids, respectively. The pET-26b(+)-SufA/SufB/SufC/SufD/SufE/SufS plasmids were transformed into E. coli BL21(DE3) cells (New England Biolabs, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA) for heterologous protein overexpression, respectively, while the pET-23a(+)-AcnA plasmid was subsequently amplified by PCR to make a linear DNA harboring the T7 promoter for the following in vitro transcription.

In Vitro Assembly of the [4Fe-4S] Cluster on the SufBC2D Complex

i. Anaerobic Conditions

The [4Fe-4S]-charged SufBC2D complex was anaerobically produced inside the anoxic chamber. Reaction mixture containing HEPES-Na+ (pH 7.6; 50 mM), NaCl (100 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), dithiothreitol (DTT) (1 mM), pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (10 μM), ATP (1 mM), SufE (0.5 μM), SufS (0.5 μM), SufB (10 μM), SufC (20 μM), SufD (10 μM), FeSO4 (0.1 mM), cysteine (0.5 mM), and glycerol (5%, v/v). The reaction was initiated by the addition of cysteine and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. Optical analysis of the SufBC2D complex was performed using a microplate reader (Epoch 2 microplate reader, Agilent, CA, USA). The mature SUF including [4Fe-4S]-charged SufBC2D complex was further purified using Ni-sepharose-based immobilized affinity chromatography, as described in Supporting Methods. The protein stock solutions were flash-frozen with liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C.

ii. Aerobic Conditions

The [4Fe-4S]-charged SufBC2D complex was aerobically produced on the benchtop using O2-scavanging system. Reaction mixture containing HEPES-Na+ (pH 7.6; 50 mM), NaCl (100 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), DTT (1 mM), pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (10 μM), ATP (1 mM), sodium formate (10 mM), NADH (0.1 mM), FAD (20 μM), formate dehydrogenase (0.05 mg/mL), flavin reductase (0.05 mg/mL), catalase (0.01 mg/mL), SufE (0.5 μM), SufS (0.5 μM), SufB (10 μM), SufC (20 μM), SufD (10 μM), FeSO4 (0.1 mM), cysteine (0.1 mM), and glycerol (5%, v/v). The reaction mixture amended with the O2-scavenging enzyme cascade was first assembled and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min to scavenge the dissolved O2. The SUF proteins were then added to the reaction mixture. The reaction mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min. Optical analysis of the [4Fe-4S]-charged SufBC2D complex was performed by using a microplate reader (Epoch 2 microplate reader, Agilent, CA, USA). The mature SUF including [4Fe-4S]-charged SufBC2D complex was further purified using Ni-sepharose-based immobilized affinity chromatography as described in Supporting Methods. The reaction mixture was flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C for the following in vitro maturation of [4Fe-4S] proteins.

In Vitro Maturation of Apo-Ferredoxin and Apo-Aconitase Using the SUF System under Anaerobic Conditions

Apo-ferredoxin (Fd) and apo-aconitase (AcnA) were synthesized by PUREfrex2.0 as described in Supporting Methods. The apoproteins were then mixed with purified mature SUF inside the anoxic chamber. The reaction mixture contained HEPES-K+ (pH 7.6; 50 mM), DTT (0.5 mM), 2-mercaptoethanol (0.1%, v/v), FeCl3 (40 μM), anaerobically/aerobically produced SufBC2D complex (2 μM), SufA (1.5 μM), apo-Fd/AcnA (0.01–0.1 mg/mL), and glycerol (5%, v/v). Note that for control experiments, heat-denatured SUF was prepared by incubating the mature SufBC2D complex and SufA at 95 °C for 10 min and was added to the reaction as well as S2– (8 μM) was added to the reaction instead of the SUF system. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 37 °C for 10 min and dialyzed using the Amicon Ultra-0.5 centrifugal filter (cutoff: 3 kDa) (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) inside the anaerobic chamber.

The Bifunctional Enzyme Cascade for FADH2 Regeneration and O2 Scavenging

The O2-scavenging enzyme cascade reaction was performed in the reaction mixture (100 μL) with HEPES-Na+ (pH 7.6; 50 mM), NaCl (100 mM), MgCl2 (5 mM), sodium formate (10 mM), NADH (0.1 mM), FAD (20 μM), formate dehydrogenase (0.05 mg/mL), flavin reductase (0.05 mg/mL), catalase (0.01 mg/mL), and glycerol (5%, v/v). The reaction was initiated by the addition of formate dehydrogenase. Assays were performed under aerobic conditions using an optical 96-well microplate at 37 °C for 10 min with a UV–vis scanning at λ445 nm every 5 s on a microplate reader. The stock solution of sodium formate (1 M) was adjusted to pH 7.6 in a HEPES-Na+ buffer (50 mM) to prevent a drastic pH shift in the reaction mixture.

One-Pot Cell-Free Synthesis of Holo-Aconitase under Aerobic Conditions

Apo-AcnA was synthesized using a customized PUREfrex2.0 system following the manufacturer’s standard protocols on a benchtop. Briefly, in an ice bath, solution I (amino acids, NTPs, tRNAs and substrates for enzymes, etc.; 100 μL), solution II (enzyme mixtures; 10 μL), and solution III (ribosome; 20 μL) were mixed with the components to final concentrations of flavin reductase (0.05 mg/mL), formate dehydrogenase (0.05 mg/mL), catalase (0.025 mg/mL), sodium formate (10 mM), pyridoxal 5′-phosphate (10 μM), NADH (0.2 mM), FAD (20 μM), and AcnA mRNA (0.4–0.7 μM) to a final volume of 200 μL. Cell-free protein synthesis was performed at 37 °C for 6 h, and the reaction mixtures were kept on ice after incubation for in vitro maturation of aconitase using the SUF system. The PUREfrex reaction mixture containing apo-AcnA was supplemented with FeSO4 (0.1 mM) and individually purified SUF subunits: SufA (1.5 μM), SufB (8 μM), SufC (16 μM), SufD (8 μM), SufE (0.4 μM), and SufS (0.4 μM), and was incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The holo-AcnA was purified using Ni-sepharose-based immobilized affinity chromatography as described in Supporting Methods.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Prof. Alexander F. Yakunin, Bangor University, United Kingdom for the gift of formate dehydrogenase construct (UniProt P33160). Icons in figures were created using BioRender (https://biorender.com).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Fd

ferredoxin

- PURE system

reconstituted cell-free protein synthesis system.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssynbio.3c00155.

Table S1. Calculation of dissolved oxygen in the PUREfrex reactions (XLSX)

Supporting Methods; Table S2. Complete list of recombinant proteins, expression vectors, and primers for gene cloning used in this work; Figure S1. SDS-PAGE gel images of purified recombinant proteins and apo-Fd/AcnA synthesized by the PURE system; Figure S2. Images of the mature SufBC2D complex at different concentrations of FeSO4; Figure S3. Standard curve to estimate the holo-Fd concentration using the cytochrome C-coupled optical assays; Figure S4. UV–vis analysis of the recombinant holo-Fd and AcnA purified from the anaerobically cultivated E. coli BL21 cells; Figure S5. Standard curve to estimate the holo-AcnA concentration using the aconitase A and isocitrate dehydrogenase-coupled activity assays; Figure S6. NADH and FADH2 production using formate dehydrogenase and the O2-scavenging system, respectively; Figure S7. LC-MS spectra of citrate; Figure S8. LC-MS spectra of alpha-ketoglutarate (PDF)

Author Contributions

P.-H.W. and K.F. conceptualized this research; P.-H.W. and S.N. performed the experiments; all authors participated in experimental design and data analysis; P.-H.W. and S.N. wrote this paper with assistance from all authors.

Author Contributions

¶ P.-H.W. and S.N. contributed equally to this work.

P.-H.W. is supported by the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwan (111-2628-E-008-009). K.F. is supported by ELSI research grant and NINS Astrobiology Center grant (AB301003 and AB311001). S.E.M. is supported by ELSI research grant.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Special Issue

Published as part of the ACS Synthetic Biologyvirtual special issue “Synthetic Cells”.

Supplementary Material

References

- Evans M. C.; Buchanan B. B.; Arnon D. I. A new ferredoxin-dependent carbon reduction cycle in a photosynthetic bacterium. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1966, 55 (4), 928–934. 10.1073/pnas.55.4.928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.; Huang L.; Shulmeister V. M.; Chi Y. I.; Kim K. K.; Hung L. W.; Crofts A. R.; Berry E. A.; Kim S. H. Electron transfer by domain movement in cytochrome Bc1. Nature 1998, 392 (6677), 677–684. 10.1038/33612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yankovskaya V.; Horsefield R.; Törnroth S.; Luna-Chavez C.; Miyoshi H.; Léger C.; Byrne B.; Cecchini G.; Iwata S. Architecture of succinate dehydrogenase and reactive oxygen species generation. Science 2003, 299 (5607), 700–704. 10.1126/science.1079605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinert H.; Holm R. H.; Münck E. Iron-sulfur clusters: nature’s modular, multipurpose structures. Science 1997, 277 (5326), 653–659. 10.1126/science.277.5326.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens P. J.; Jollie D. R.; Warshel A. Protein control of redox potentials of iron-sulfur proteins. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96 (7), 2491–2514. 10.1021/cr950045w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak D. W.; Elliott S. J. Alternative FeS cluster ligands: tuning redox potentials and chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2014, 19, 50–58. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2013.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beinert H.; Kennedy M. C.; Stout C. D. Aconitase as iron-sulfur protein, enzyme, and iron-regulatory protein. Chem. Rev. 1996, 96, 2335–2374. 10.1021/cr950040z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters J. W.; Fisher K.; Newton W. E.; Dean D. R. Involvement of the P cluster in intramolecular electron transfer within the nitrogenase MoFe protein. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270 (45), 27007–27013. 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odom J. M.; Peck H. D. Jr. Hydrogenase, electron-transfer proteins, and energy coupling in the sulfate-reducing bacteria Desulfovibrio. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 1984, 38, 551–592. 10.1146/annurev.mi.38.100184.003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holliger C.; Wohlfarth G.; Diekert G. Reductive dechlorination in the energy metabolism of Anaerobic Bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 1998, 22 (5), 383–398. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1998.tb00377.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jørgensen B. B.; Kasten S.. Sulfur cycling and methane oxidation. In Marine Geochemistry; Schulz H. D., Zabel M., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2006; pp 271–309. [Google Scholar]

- Ragsdale S. W. Pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase and its radical intermediate. Chem. Rev. 2003, 103 (6), 2333–2346. 10.1021/cr020423e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia P. S.; D’Angelo F.; Ollagnier de Choudens S.; Dussouchaud M.; Bouveret E.; Gribaldo S.; Barras F. An early origin of iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis machineries before Earth oxygenation. Nature Ecology & Evolution 2022, 6 (10), 1564–1572. 10.1038/s41559-022-01857-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esquilin-Lebron K.; Dubrac S.; Barras F.; Boyd J. M. Bacterial approaches for assembling iron-sulfur proteins. mBio 2021, 12 (6), e0242521 10.1128/mBio.02425-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M. R.; Cash V. L.; Weiss M. C.; Laird N. F.; Newton W. E.; Dean D. R. Biochemical and genetic analysis of the NifUSVWZM cluster from Azotobacter Vinelandii. Molecular and General Genetics 1989, 219 (1–2), 49–57. 10.1007/BF00261156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L.; Cash V. L.; Flint D. H.; Dean D. R. Assembly of iron-sulfur clusters. Identification of an IscSUA-HscBA-Fdx gene cluster from Azotobacter Vinelandii. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273 (21), 13264–13272. 10.1074/jbc.273.21.13264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi Y.; Tokumoto U. A third bacterial system for the assembly of iron-sulfur clusters with homologs in archaea and plastids. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277 (32), 28380–28383. 10.1074/jbc.C200365200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Y.; Outten F. W. The E. Coli SufS-SufE sulfur transfer system is more resistant to oxidative stress than IscS-IscU. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586 (22), 4016–4022. 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd E. S.; Thomas K. M.; Dai Y.; Boyd J. M.; Outten F. W. Interplay between oxygen and Fe-S cluster biogenesis: insights from the Suf pathway. Biochemistry 2014, 53 (37), 5834–5847. 10.1021/bi500488r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wollers S.; Layer G.; Garcia-Serres R.; Signor L.; Clemancey M.; Latour J.-M.; Fontecave M.; Ollagnier de Choudens S. Iron-sulfur (Fe-S) cluster assembly: the SufBCD complex is a new type of Fe-S scaffold with a flavin redox cofactor. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (30), 23331–23341. 10.1074/jbc.M110.127449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakunin A. F.; Hallenbeck P. C. Purification and characterization of pyruvate oxidoreductase from the photosynthetic bacterium Rhodobacter Capsulatus. Biochimica et Biophysica acta 1998, 1409 (1), 39–49. 10.1016/S0005-2728(98)00145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M. C.; Mende-Mueller L.; Blondin G. A.; Beinert H. Purification and characterization of cytosolic aconitase from beef liver and its relationship to the iron-responsive element binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89 (24), 11730–11734. 10.1073/pnas.89.24.11730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khoroshilova N.; Popescu C.; Münck E.; Beinert H.; Kiley P. J. Iron-sulfur cluster disassembly in the FNR protein of Escherichia coli by O2: [4Fe-4S] to [2Fe-2S] conversion with loss of biological activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997, 94 (12), 6087–6092. 10.1073/pnas.94.12.6087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan J. T.; Jarrett J. T. Electron acceptor specificity of ferredoxin (flavodoxin):NADP+ oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002, 406 (1), 116–126. 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00421-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J.; Rabinowitz J. C. Preparation and properties of clostridial apoferredoxins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1967, 29 (2), 246–252. 10.1016/0006-291X(67)90595-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsibris J. C.; Tsai R. L.; Gunsalus I. C.; Orme-Johnson W. H.; Hansen R. E.; Beinert H. The number of iron atoms in the paramagnetic center (G = 1.94) of reduced putidaredoxin, a nonheme iron protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1968, 59 (3), 959–965. 10.1073/pnas.59.3.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petering D.; Fee J. A.; Palmer G. The oxygen sensitivity of spinach ferredoxin and other iron-sulfur proteins. The formation of protein-bound sulfur-zero. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246 (3), 643–653. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)62463-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y.; Inoue A.; Tomari Y.; Suzuki T.; Yokogawa T.; Nishikawa K.; Ueda T. Cell-free translation reconstituted with purified components. Nat. Biotechnol. 2001, 19 (8), 751–755. 10.1038/90802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.-M.; Swartz J. R. Regeneration of adenosine triphosphate from glycolytic intermediates for cell-free protein synthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2001, 74, 309–316. 10.1002/bit.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett M. C.; Swartz J. R. Mimicking the Escherichia coli cytoplasmic environment activates long-lived and efficient cell-free protein synthesis. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2004, 86 (1), 19–26. 10.1002/bit.20026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartz J. R.; Jewett M. C.; Woodrow K. A. Cell-free protein synthesis with prokaryotic combined transcription-translation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2004, 267, 169–182. 10.1385/1-59259-774-2:169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niwa T.; Kanamori T.; Ueda T.; Taguchi H. Global analysis of chaperone effects using a reconstituted cell-free translation system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109 (23), 8937–8942. 10.1073/pnas.1201380109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavickova B.; Maerkl S. J. A Simple, robust, and low-cost method to produce the PURE cell-free system. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019, 8 (2), 455–462. 10.1021/acssynbio.8b00427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavickova B.; Laohakunakorn N.; Maerkl S. J. A partially self-regenerating synthetic cell. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11 (1), 6340. 10.1038/s41467-020-20180-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer M. E.; Wang C.-W.; Swartz J. R. Simultaneous expression and maturation of the iron-sulfur protein ferredoxin in a cell-free system. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2006, 94, 128–138. 10.1002/bit.20830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer M. E.; Stapleton J. A.; Kuchenreuther J. M.; Wang C.-W.; Swartz J. R. Cell-free synthesis and maturation of [FeFe] hydrogenases. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008, 99 (1), 59–67. 10.1002/bit.21511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.-H.; Fujishima K.; Berhanu S.; Kuruma Y.; Jia T. Z.; Khusnutdinova A. N.; Yakunin A. F.; McGlynn S. E. A Bifunctional polyphosphate kinase driving the regeneration of nucleoside triphosphate and reconstituted cell-free protein synthesis. ACS Synth. Biol. 2020, 9 (1), 36–42. 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layer G.; Gaddam S. A.; Ayala-Castro C. N.; Ollagnier-de Choudens S.; Lascoux D.; Fontecave M.; Outten F. W. SufE transfers sulfur from SufS to SufB for iron-sulfur cluster assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2007, 282 (18), 13342–13350. 10.1074/jbc.M608555200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Outten F. W.; Wood M. J.; Munoz F. M.; Storz G. The SufE protein and the SufBCD complex enhance SufS cysteine desulfurase activity as part of a sulfur transfer pathway for Fe-S cluster assembly in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278 (46), 45713–45719. 10.1074/jbc.M308004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson M. K. Iron—sulfur proteins: new roles for old clusters. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1998, 2 (2), 173–181. 10.1016/S1367-5931(98)80058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanden S. A.; Yi R.; Hara M.; McGlynn S. E. Simultaneous synthesis of thioesters and iron-sulfur clusters in water: two universal components of energy metabolism. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56 (80), 11989–11992. 10.1039/D0CC04078A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai T.; Taguchi K.; Ogawara Y.; Ohmori D.; Yamakura F.; Ikezawa H.; Urushiyama A. Characterization and cloning of an extremely thermostable, Pyrococcus furiosus-type 4Fe ferredoxin from Thermococcus profundus. J. Biochem. 2001, 130 (5), 649–655. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a003030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aliverti A.; Pandini V.; Pennati A.; de Rosa M.; Zanetti G. Structural and functional diversity of ferredoxin-NADP(+) reductases. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008, 474 (2), 283–291. 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil P. V.; Ballou D. P. The use of protocatechuate dioxygenase for maintaining anaerobic conditions in biochemical experiments. Anal. Biochem. 2000, 286 (2), 187–192. 10.1006/abio.2000.4802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken C. E.; Marshall R. A.; Puglisi J. D. An oxygen scavenging system for improvement of dye stability in single-molecule fluorescence experiments. Biophys. J. 2008, 94 (5), 1826–1835. 10.1529/biophysj.107.117689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro T.; Moreira M.; Gaspar S. B. R.; Almeida M. G. Bilirubin oxidase as a single enzymatic oxygen scavenger for the development of reductase-based biosensors in the open air and its application on a nitrite biosensor. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 217, 114720. 10.1016/j.bios.2022.114720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudu P.; Touati D.; Nivière V.; Fontecave M. The NAD(P) H:flavin oxidoreductase from Escherichia coli as a source of superoxide radicals. J. Biol. Chem. 1994, 269 (11), 8182–8188. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)37178-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batyrova K. A.; Khusnutdinova A. N.; Wang P.-H.; Di Leo R.; Flick R.; Edwards E. A.; Savchenko A.; Yakunin A. F. Biocatalytic in vitro and in vivo FMN prenylation and (de) carboxylase activation. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15 (7), 1874–1882. 10.1021/acschembio.0c00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerin T. F.; Mondido M.; McClenn B.; Peasley B. Application of resazurin for estimating abundance of contaminant-degrading micro-organisms. Letters in Applied Microbiology 2001, 32 (5), 340–345. 10.1046/j.1472-765X.2001.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimata S.; Mochizuki D.; Satoh J.; Kitano K.; Kanesaki Y.; Takeda K.; Abe A.; Kawasaki S.; Niimura Y. Intracellular free flavin and its associated enzymes participate in oxygen and iron metabolism in Amphibacillus xylanus lacking a respiratory chain. FEBS Open Bio 2018, 8 (6), 947–961. 10.1002/2211-5463.12425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth-Metzler R.; Bray M. S.; Frenkel-Pinter M.; Suttapitugsakul S.; Montllor-Albalate C.; Bowman J. C.; Wu R.; Reddi A. R.; Okafor C. D.; Glass J. B.; Williams L. D. Cutting in-line with iron: ribosomal function and non-oxidative RNA cleavage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48 (15), 8663–8674. 10.1093/nar/gkaa586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa M.; Ara T.; Arifuzzaman M.; Ioka-Nakamichi T.; Inamoto E.; Toyonaga H.; Mori H. Complete set of ORF clones of Escherichia coli ASKA library (a complete set of E. coli K-12 ORF archive): unique resources for biological research. DNA Research 2006, 12 (5), 291–299. 10.1093/dnares/dsi012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi K. A Simple and efficient seamless DNA cloning method using SLiCE from Escherichia coli laboratory strains and its application to SLiP site-directed mutagenesis. BMC Biotechnol. 2015, 15, 47. 10.1186/s12896-015-0162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motohashi K. Seamless ligation cloning extract (SLiCE) method using cell lysates from laboratory Escherichia coli strains and its application to SLiP site-directed mutagenesis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017, 1498, 349–357. 10.1007/978-1-4939-6472-7_23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang A.; Jeske L.; Ulbrich S.; Hofmann J.; Koblitz J.; Schomburg I.; Neumann-Schaal M.; Jahn D.; Schomburg D. BRENDA, the ELIXIR core data resource in 2021: new developments and updates. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49 (D1), D498–D508. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.