Abstract

Chronic lung rejection, also called chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), remains the major hurdle limiting long-term survival after lung transplantation, and limited therapeutic options are available to slow the progressive decline in lung function. Most interventions are only temporarily effective in stabilizing the loss of or modestly improving lung function, with disease progression resuming over time in the majority of patients. Therefore, identification of effective treatments that prevent the onset or halt progression of CLAD is urgently needed. As a key effector cell in its pathophysiology, lymphocytes have been considered a therapeutic target in CLAD. The aim of this review is to evaluate the use and efficacy of lymphocyte depleting and immunomodulating therapies in progressive CLAD beyond usual maintenance immunosuppressive strategies. Modalities used include anti-thymocyte globulin, alemtuzumab, methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, total lymphoid irradiation, and extracorporeal photopheresis, and to explore possible future strategies. When considering both efficacy and risk of side effects, extracorporeal photopheresis, anti-thymocyte globulin and total lymphoid irradiation appear to offer the best treatment options currently available for progressive CLAD patients.

Significance Statement

Effective treatments to prevent the onset and progression of chronic lung rejection after lung transplantation are still a major shortcoming. Based on existing data to date, considering both efficacy and risk of side effects, extracorporeal photopheresis, anti-thymocyte globulin, and total lymphoid irradiation are currently the most viable second-line treatment options. However, it is important to note that interpretation of most results is hampered by the lack of randomized controlled trials.

I. Introduction

Lung transplantation is a life-saving therapeutic option in well-selected patients with end-stage chronic lung diseases. Advancements in surgical techniques and early post-transplant care, such as maintenance immunosuppressive therapy and management of infections, have improved post-transplant outcomes in the past decades (Bos et al., 2020). Nevertheless, survival after lung transplantation still lags behind that of recipients of other solid organ transplants, with a median post-transplant survival of only 6.7 years (Chambers et al., 2019). To a larger extent, this poor long-term survival is related to the high incidence of and difficulty managing chronic lung rejection, so-called chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD), a progressive life-threatening condition affecting 50% of patients within five years post-transplant, leading to lung allograft failure, respiratory insufficiency and death (Chambers et al., 2019).

CLAD encompasses two main phenotypes, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) and restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS), along with a mixed phenotype with features of both. BOS is the commonest phenotype in approximately 70% of CLAD patients and is characterized by progressive airway obliteration leading to airflow obstruction. RAS occurs in up to 20%–30% of CLAD patients and is characterized by parenchymal and/or pleural fibrosis with a restrictive pulmonary function decline. RAS has a very poor prognosis, with a median survival of only 1-2 years after diagnosis compared with 3–5 years for BOS. The diagnosis of CLAD is made based on a decline in forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1) of ≥20% from post-transplant baseline, defined as the mean of the two best post-operative FEV1 measurements taken >3 weeks apart, in combination with a concurrent decline in forced vital capacity of ≥20% and persistent opacities on chest imaging for the RAS phenotype (Verleden et al., 2019). CLAD leads to a progressive decline in FEV1; this decline is often stepwise, in which after an initial decrease a plateau phase is reached. However, some patients have a steep and rapidly progressive decline, while others have a slower decline over years (Belperio et al., 2009; Sato et al., 2013). CLAD severity is graded from 1–4 based on the severity of FEV1 decline (stage 1: 66–80%, stage 2: 51–65%, stage 3: 36–50%, stage 4: ≤35% of baseline) (Verleden et al., 2019).

It is postulated that CLAD occurs as a result of the host’s adaptive and innate immune responses directed to the lung allograft, in which a complex array of immune cells and mechanisms is involved (Bos et al., 2022b,c). Next to medical non-compliance with immunosuppressive treatment, various risk factors for CLAD have been identified, both alloimmune and non-alloimmune factors, including ischemia-reperfusion injury, acute cellular rejection, antibody-mediated rejection, respiratory infections, gastroesophageal reflux, and air pollution (Verleden et al., 2019).

The type of standard immunosuppressive maintenance treatment after lung transplantation varies between centers, but usually consists of triple therapy with a calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus/cyclosporine), a cell cycle inhibitor (mycophenolate mofetil/azathioprine) and corticosteroids (Nelson et al., 2022). Currently, therapeutic options to slow the progressive decline in lung function in CLAD are very limited. These include intensification and optimization of maintenance immunosuppression, such as augmentation of corticosteroids and switching to more potent maintenance immunosuppressive drugs, such as from cyclosporine to tacrolimus and azathioprine to mycophenolate mofetil (Nelson et al., 2022). This, often in combination with the addition of azithromycin (if not already initiated as preventive treatment post-transplant), is usually instituted as an early measure to aim to halt CLAD progression (Verleden et al., 2019). The immunomodulatory properties of azithromycin in CLAD are summarized in a review by Vos et al. (Vos et al., 2012).

Beyond this first line of treatments, several lymphocyte depleting and/or modulating therapies have been studied in patients with progressive CLAD, including methotrexate, cyclophosphamide, alemtuzumab, anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG), total lymphoid irradiation (TLI), and extracorporeal photopheresis (ECP). Most of these therapies have only been evaluated in small retrospective single-center studies, and the effect reported is often temporary with further disease progression over time in the majority of patients. Therefore, there is a compelling need for more effective treatments to prevent the onset and progression of CLAD (Verleden et al., 2019).

This review summarizes the data available to date on the efficacy of lymphocyte depleting and modulating therapies in CLAD beyond optimized maintenance immunosuppressive strategies and explores possible future directions in this area. For this, the electronic databases of PubMed and EMBASE were searched in July 2022 and publications related to our predefined topic were included. There is little data available on use of these modalities for the treatment of RAS, as such, most of the data presented in this review focuses on experience from the treatment of BOS.

II. Immunodepleting Therapies

A. Alemtuzumab

Alemtuzumab is a recombinant humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against CD52, which is expressed on the cell surface of mainly T and B lymphocytes, and to a lesser extent on natural killer cells, macrophages, and monocytes, and is believed to play a role in cell signaling and homeostasis (Bhowmick et al., 2016; Syed, 2021). Alemtuzumab induces a rapid, profound and prolonged (i.e., several months) lymphocyte depletion through antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytolysis, complement-dependent cytolysis, and induction of apoptosis, but also leads to an expansion of regulatory T and B cells during repopulation (Bhowmick et al., 2016) (Fig. 1). Because of prolonged lymphodepletion, the potential for sustained bone marrow suppression is of concern, especially given the susceptibility of lung transplant recipients to infections and malignancies (Trindade et al., 2020).

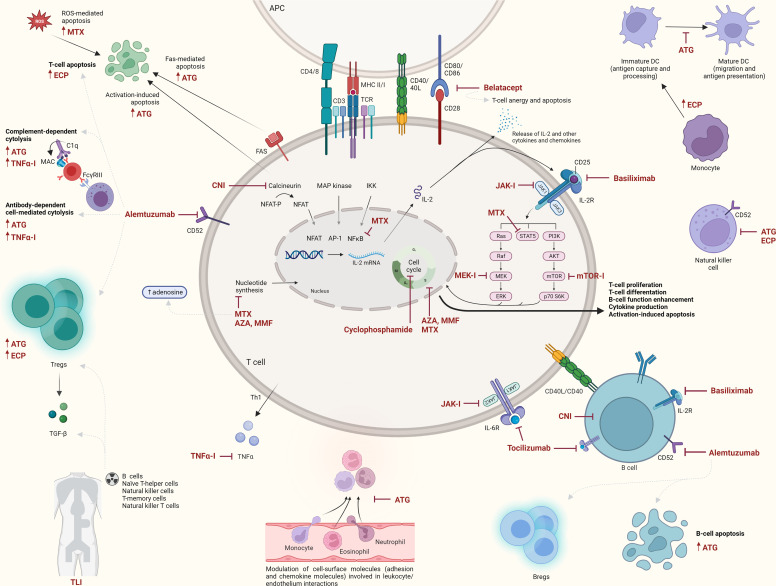

Fig. 1.

Overview of main mechanisms of several lymphocyte depleting and/or modulating therapies for CLAD. APC, antigen-presenting cell (e.g., dendritic cell, macrophage, B cell); AZA, azathioprine; Bregs, regulatory B cells; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; DC, dendritic cell; JAK-I, janus kinase inhibitor; MEK-I, mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase inhibitor; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MTX, methotrexate; TNFα-I, tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitor; Tregs, regulatory T cells. Created with BioRender.com.

Alemtuzumab has been used primarily for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia (Hallek, 2017) and relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (Syed, 2021), but also off-label for induction immunosuppression in solid organ transplantation (Small et al., 2022).

1. Evidence in CLAD

In an effort to more effectively deplete T cells and other immune cells that may contribute to CLAD, Reams et al. investigated the effect of alemtuzumab (30 mg i.v.) in ten BOS patients after failure of prior therapy with methylprednisolone and ATG (Reams et al., 2007). They found a stabilization or improvement of BOS stage in 70% of patients. Alemtuzumab caused a long-lasting decrease in CD4 count and only 27% of patients remained free of infectious complications in the entire cohort, which also included patients with acute cellular rejection (Reams et al., 2007). Another study involving 17 BOS patients mainly demonstrated efficacy of alemtuzumab (30 mg i.v.) in early BOS. BOS-free progression was seen in 53% of patients at 6 months with freedom from FEV1 decline >10% in 70% of early BOS (stage 1) versus only 14% in advanced BOS (stage 2–3). Also, in this study, the infection rate was high (77%) (Ensor et al., 2017).

Moniodis et al. compared the efficacy of alemtuzumab (30 mg i.v. or s.c.) (n = 13) to ECP (n = 17) for the treatment of CLAD (Moniodis et al., 2018). The rate of FEV1 decline improved significantly at 3 and 6 months in both groups, compared with pre-treatment, with a benefit also at 1 month in the alemtuzumab group. Subgroup analyses for alemtuzumab in RAS only showed a slowing in slope at 3 months, while the BOS subgroup resembled the overall CLAD cohort. Interestingly, alemtuzumab reduced the number of rapid decliners (>25% drop FEV1) more markedly than ECP at 1, 3, and 6 months following treatment. There were no differences between alemtuzumab and ECP with regard to infections, with 29% of alemtuzumab-treated patients having a clinically significant infection in the year after treatment. There was no difference in survival at 6 months and 1 year between the alemtuzumab, ECP, and untreated (i.e., slowly progressive CLAD) group (Moniodis et al., 2018).

Trindade et al. examined the safety of alemtuzumab in a specific group of lung transplant recipients with short telomeres who are at increased risk of clinically significant leukopenia (Trindade et al., 2020). In this small study (14 CLAD patients of whom three with short telomeres), alemtuzumab treatment appeared safe, with no significant difference in infections necessitating hospitalization, although it was associated with an increased incidence of neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and anemia in the short telomere group (Trindade et al., 2020).

Lastly, a conference abstract, looking at 1-year overall survival after alemtuzumab administration in 14 patients with severe CLAD, reported that 64% were alive with a stable FEV1 in 67% of survivors (Thachuthara-George et al., 2015). Another conference abstract documented that the rate of lung function decline during the 3 months post-treatment (30 mg s.c.) was significantly lower than the 3 months prior to treatment in eight BOS patients with rapid loss of lung function (75% stage 3–4). Clinically symptomatic infections occurred in 50% of patients (Girgis et al., 2020).

Treatment with alemtuzumab appears to attenuate lung function decline, especially in BOS patients. It is, however, difficult to determine whether this change simply represents the natural course of BOS or is a direct treatment effect, although some studies (Moniodis et al., 2018; Thachuthara-George et al., 2015) have documented sustained results. Ensor et al. mainly observed efficacy in BOS stage 1 versus higher stages. Reduced efficacy in more advanced CLAD may be due to a significant delay in therapy to a point beyond where allograft function can be stabilized, because of too severe structural injury to the allograft (Ensor et al., 2017). On the other hand, beneficial results were seen by Girgis et al. where 75% of patients were in CLAD stage 3–4 (Girgis et al., 2020). While alemtuzumab may have a potential benefit in BOS, it carries a high risk of infectious complications. Randomized controlled trials are required to better establish efficacy and safety.

B. Anti-Thymocyte Globulin

ATG is a polyclonal antibody preparation, derived from rabbits or horses immunized with thymocytes or T-cell lines (Mohty, 2007). The polyclonal nature of ATG is reflected in its diverse immune effects, including prolonged (i.e., several weeks) depletion of cytotoxic T cells by complement-mediated lysis, antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, apoptosis (activation-associated and Fas-dependent apoptosis), and opsonization. Alongside T-cell-depleting properties, other potential mechanisms of action involve B-cell apoptosis, depletion of natural killer cells, interference with dendritic cells, modulation of cell surface adhesion proteins and chemokine receptors, and induction of regulatory T cells (Mohty, 2007). One should keep in mind that, despite sharing some common traits, equine and rabbit ATG are strictly different drugs (Mohty, 2007). Rabbit ATG is thought to have a better efficacy and side effect profile than equine ATG, and is more easily accessible than alemtuzumab in some countries.

ATG has been used in conditioning regimens for hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and as induction immunosuppression in solid organ transplants, including lung transplant recipients (Mohty et al., 2014; Small et al., 2022).

Common adverse events related to ATG include transfusion-related reactions, cytokine release syndrome, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, and infections (Mohty et al., 2014).

1. Evidence in CLAD

In addition to some older studies(Date et al., 1998; Kesten et al., 1996; Snell et al., 1996) published in the early era of lung transplantation that showed some efficacy, there are several larger, recent, retrospective studies that have examined the potency of ATG in slowing CLAD progression. In a study of 25 CLAD patients, 32% had stabilization of FEV1 for at least 6 months after ATG (1.5 mg/kg/d for 7 days i.v.), with an improved survival rate (Izhakian et al., 2016). However, these patients appeared to have a slower decline in FEV1 pre-treatment, suggesting an already slower disease progression (Izhakian et al., 2016). January et al. found an increase in FEV1 (defined by a shift from a negative to a positive slope) in the 6 months after ATG (5–7.5 mg/kg over 3‐6 days) compared with before in 40% of a total of 108 patients (93% BOS) (January et al., 2019). Additionally, 44% of the non-responders had a less negative FEV1 slope. It is worth noting that this study included 20% BOS stage 0p (10%–20% FEV1 decline and/or ≥25% decline in FEF25–75%) patients, and that no predictors of response were identified, neither disease severity at time of treatment, nor steepness of FEV1 decline or RAS phenotype (January et al., 2019). Kotecha et al. reported 71 patients receiving mostly equine ATG (500 mg on day 1, subsequent dosing days 2–5 based on CD2/CD3 lymphocyte counts) for CLAD (83% BOS). Twenty-three percent were complete responders who had stabilization or improvement in FEV1, while 40% were partial responders with a ≥20% improved rate of FEV1 decline (Kotecha et al., 2021). Risk of death or retransplantation was significantly lower in these groups, with a 70% and 65% reduction, respectively. CLAD stage 2–3 and younger age were predictors of partial, but not complete, response. CLAD phenotype did not correlate with response. Interestingly, as many centers only try ATG treatment once, 30% of patients had received ATG twice with a median interval of 3 months (Kotecha et al., 2021). Finally, another small study of 13 CLAD patients (77% BOS; ATG 1.5 mg/kg/d, total target dose 10–20 mg/kg) reported stabilization or improvement (>5%) of FEV1 in half of the patients (Margallo Iribarnegaray et al., 2021). Most patients who responded were in CLAD stage 1–2 (71%). Worse survival was observed in rapid decliners (monthly FEV1 drop >100 ml) (Margallo Iribarnegaray et al., 2021).

Most important side effects reported in these studies were mild infusion-related reactions (January et al., 2019; Margallo Iribarnegaray et al., 2021), infections (up to 19%) (January et al., 2019), severe leukopenia (4%) (Izhakian et al., 2016), and neutropenia (14%) (Margallo Iribarnegaray et al., 2021).

ATG appears to be effective in stabilizing or attenuating lung function decline in a subgroup of CLAD patients, including RAS, and may lead to prolonged survival. Although certain predictors of response have been identified, such as early disease stages (Kotecha et al., 2021; Margallo Iribarnegaray et al., 2021), these were not consistent across all studies (January et al., 2019). Multicenter, randomized controlled trials are needed to better determine predictors of response to ATG in CLAD.

C. Total Lymphoid Irradiation

Radiation therapy is undoubtedly best known for its role in cancer treatment, but its use extends beyond this (McKay et al., 2014). TLI targets the main structures of the lymphatic system as most lymphocytes are highly radiation sensitive (Schaue and McBride, 2012). TLI therefore has a strong immunosuppressive nature; it produces a selective and long-lasting (i.e., several weeks) reduction of certain subsets of T-cell and B-cell populations. In general, there is a spectrum of radiosensitivity from B cells through naïve T-helper cells, natural killer cells, toward more radioresistant T-memory cells and natural killer T cells. As a result, irradiation shifts the balance of the immune system. Regulatory T cells and natural killer T cells are relatively radioresistant and their proportion within the lymphoid tissues increases rapidly following irradiation. Further induction and activation of regulatory T cells can occur via TGF-β, which is induced by TLI (Schaue and McBride, 2012). TLI is often administered in ten fractions of 0.8 Gy twice weekly, via mantle, paraaortic and inverted-Y fields (McKay et al., 2014).

1. Evidence in CLAD

A first study in 1998 described poor efficacy of TLI in 11 BOS patients; most patients died within eight weeks of cessation due to further disease progression or infection, and only 36% had sustained stabilization of FEV1 with a mean follow up of 24–72 weeks (Diamond et al., 1998). Later, Verleden et al. documented a significant attenuation in the rate of FEV1 decline in a small group (n = 6) compared with historical controls (n = 5), although half of them failed within the first year after TLI (Verleden et al., 2009). The Newcastle Group also reported that TLI significantly decreased the rate of FEV1 decline in 12 BOS patients (Chacon et al., 2000) and in a further, larger study of 37 BOS patients (Fisher et al., 2005), the majority of whom had BOS stage 2–3. Interestingly, the latter study found that the most pronounced effect appeared to occur in patients with the fastest progression prior to TLI (Fisher et al., 2005). Lastly, in a recent study, the Leuven Group reported the outcome of 20 BOS patients (65% BOS 3) treated with TLI, including the six previously reported (Verleden et al., 2009) patients (Lebeer et al., 2020). Four patients (20%) died during or shortly after TLI due to progressive respiratory insufficiency, while the decline in FEV1 slowed significantly in 94% of the remaining patients, again especially in those with a rapid decline pre-TLI (≥ 100 ml/mo) (Lebeer et al., 2020). An absolute increase in FEV1 was seen in 13% 6 months post-treatment, even though these patients were already in BOS 3. Freedom from graft loss was 27% 2 years after TLI (Lebeer et al., 2020). Lastly, a recently published study (Geng-Cahuayme et al., 2022) included 23% RAS patients and showed significant attenuation of FEV1 slope in both BOS and RAS phenotypes and both rapid and slow decliners. They found that a Karnofsky Performance Status of >70 was a prognostic marker for survival (Geng-Cahuayme et al., 2022).

In addition to these studies, several conference abstract reports were available. Most of these had similar findings with a decrease in FEV1 decline post-treatment compared with before (Afolabi et al., 1996; Arbeláez et al., 2014; Hunt et al., 2019; Low et al., 2017; Miller et al., 2016; Soresi et al., 2015; Sáez et al., 2014). Hunt et al. reported a mean survival of 4.2 (range 0.75–7.5) years post-TLI, and Soresi et al. a 2-year overall survival of 59% after initiation of treatment (Hunt et al., 2019; Soresi et al., 2015). Schmack et al. attempted to correlate specific lymphocyte phenotypes with response to TLI in a prospective study of 26 patients with progressive BOS (Schmack et al., 2017). They found an inverse correlation between the total number of peripheral B cells, naive B cells, memory B cells, plasmablasts, and naive CD8+ T cells pre-treatment and patient survival (Schmack et al., 2017).

Frequently reported side effects were neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, infections, gastrointestinal symptoms, and fatigue (McKay et al., 2014). The first three often led to treatment being delayed or terminated prematurely (Fisher et al., 2005; Geng-Cahuayme et al., 2022; Lebeer et al., 2020; O’Hare et al., 2011).

Although data on TLI in CLAD remain relatively scarce, the findings are consistent across most studies in which TLI appeared to attenuate the decline in lung function in BOS and RAS. Importantly, it also seemed to be effective in CLAD patients with a rapid decline in lung function at the time of treatment initiation. Early initiation after CLAD onset may be warranted, although good results have also been documented in patients with advanced BOS (Fisher et al., 2005; Lebeer et al., 2020). Reported complications, such as neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, and risk of infection, suggest that TLI should be used with caution, although the incidence of serious side effects was low.

III. Immunomodulating Therapies

A. Methotrexate

Methotrexate is a folic acid analog and acts via several suggested mechanisms, including inhibition of purine and pyrimidine synthesis, suppression of transmethylation reactions with accumulation of polyamines, prolonged (i.e., several weeks) reduction of antigen-dependent T-cell proliferation, apoptosis of T cells through the generation of reactive oxygen species, as well as selective downregulation of B cells, interference with cytokines and matrix metalloproteinases, and promotion of extracellular release of adenosine (Alqarni and Zeidler, 2020; Amrouche and Jamin, 2017; Bedoui et al., 2019). Adenosine is a potent anti-inflammatory mediator that acts through interactions with a variety of immune cell subtypes, such as neutrophils, macrophages, and T cells (Bedoui et al., 2019). In addition, recent insights suggest that methotrexate may also exert its anti-inflammatory effects via inhibition of nuclear factor-κB and the JAK/STAT pathway (Alqarni and Zeidler, 2020; Bedoui et al., 2019).

As a drawback, methotrexate has a high toxicity profile and can cause considerable side effects, including cytopenia, stomatitis, subcutaneous nodulosis, hepatic and renal toxicity, fatigue and lethargy (Bedoui et al., 2019). Although most of these mainly occur when higher doses (usually >30 mg/m2) are used as part of a chemotherapy regimen. Importantly, methotrexate can also cause pulmonary toxicity, such as drug-induced pneumonitis (Pivovarov and Zipursky, 2019).

Methotrexate has been used extensively in the treatment of neoplasms as a chemotherapeutic agent, autoimmune and connective tissue diseases such as rheumatic arthritis (Alqarni and Zeidler, 2020), interstitial lung diseases, including sarcoidosis (van den Bosch et al., 2022), and is commonly used after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation to prevent graft-versus-host disease (GvHD) (Martinez-Cibrian et al., 2021).

1. Evidence in CLAD

Evidence for methotrexate in CLAD is sparse and limited to BOS. A small study of ten patients showed that methotrexate could reduce the rate of lung function decline in BOS (Dusmet et al., 1996). Boettcher et al. also reported some benefit of methotrexate (single dose of 5 mg/kg or 7.5 mg/week) in three BOS patients (Boettcher et al., 2002). The same was found in a larger, retrospective study of 30 BOS patients, the majority of whom had BOS stage 3 at the time of treatment initiation (5–10 mg/week) (Sithamparanathan et al., 2016). A decrease in the rate of lung function decline was seen in 95% of patients treated for at least 6 months (70% of the cohort), with a significant median increase in FEV1 at 3 and 6 months. The reduced rate of lung function decline remained significant in those treated for at least 12 months. However, methotrexate had to be discontinued in 30% of patients due to nausea, fatigue or leukopenia. This number was higher than that seen in, for example auto-immune diseases, but may be explained by the combination of other immunosuppressants and transplant-related drugs (Sithamparanathan et al., 2016).

Although based on a limited number of small uncontrolled retrospective studies, methotrexate might slow the rate of lung function decline in BOS patients, even in patients with severe BOS. With the recent insights on the involvement of methotrexate in the JAK/STAT pathway, one could reconsider further prospective studies as it is a less expensive alternative to more specific Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors (discussed later in this review) (Alqarni and Zeidler, 2020). However, toxicity is still a concern and lack of tolerability and side effects were the main cause of drug withdrawal (Sithamparanathan et al., 2016).

B. Cyclophosphamide

Cyclophosphamide is an alkylating agent belonging to the group of oxazaphosporines (Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016). It is an inactive prodrug, requiring bioactivation by P450 enzymes to exhibit cytotoxic activity. Since cyclophosphamide has been used for over 40 years, there is plenty of experience in its use for the treatment of cancer and as a highly potent immunosuppressant for the treatment of autoimmune and immune-mediated diseases including vasculitis, systemic sclerosis, connective tissue disease-related interstitial lung disease (Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016; Barnes et al., 2018; Emadi et al., 2009; van den Bosch et al., 2022).

Cyclophosphamide halts cell division by cross-linking DNA strands (Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016). Therefore, it is a non-specific cell-cycle inhibitor affecting most cell lines, although it has some selectivity toward T and B lymphocytes, causing prolonged (i.e., several weeks) immunosuppressive effects. It is therefore now widely adopted in tumor vaccination protocols and to control alloreactivity after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016; Nunes and Kanakry, 2019). Interestingly, cyclophosphamide can also increase the number of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016).

Important side effects are cytopenia, nausea, hemorrhagic cystitis, cardio-, liver- and nephrotoxicity, and carcinogenicity with an increased risk of hematological and solid organ malignancies (e.g., secondary acute leukemia, bladder cancer, skin cancer) (Ahlmann and Hempel, 2016; Barnes et al., 2018).

1. Evidence in CLAD

In 1999, Verleden et al. reported the outcome of oral cyclophosphamide (0.5–1 mg/kg daily) in seven BOS patients. In 86% of patients, FEV1 stabilized or increased 3 and 6 months after initiation and remained stable for at least 24 ± 7 months in five patients who were able to continue treatment (Verleden et al., 1999). Cyclophosphamide was well tolerated and had to be discontinued in only one patient because of persistent leukopenia (Verleden et al., 1999). Other than this study, however, no further data in CLAD are available. As such, the role of cyclophosphamide in the treatment of CLAD remains unclear.

C. mTOR Inhibitors

Mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors have been used after lung transplantation for several indications, such as a cell cycle inhibitor alternative, as part of a calcineurin inhibitor-sparing regimen or adjunctive immunosuppressive agent in the setting of rejection, cytomegalovirus infection or in patients with malignancies (Fine and Kushwaha, 2016). mTOR inhibitors block mammalian target of rapamycin, a serine/threonine kinase, and thereby inhibit growth factor-stimulated proliferation of lymphocytes and mesenchymal cells. In addition, mTOR inhibitors also interfere with B and dendritic cell maturation and function (Thomson et al., 2009) and possibly NK cell-mediated endotheliitis (Koenig et al., 2019). Common adverse events are gastrointestinal intolerance, leukopenia, edema, thromboembolic events, and drug-induced pneumonitis.

1. Evidence in CLAD

Most recent studies on mTOR inhibitors have focused on their use in maintenance immunosuppression as part of a calcineurin inhibitor-sparing regimen with the aim of preserving kidney function. The combination of low-dose everolimus and low-dose tacrolimus appeared safe, with no difference in incidence of acute rejection or CLAD compared with high-dose calcineurin inhibitor therapy (Gottlieb et al., 2019; Ivulich et al., 2023; Kneidinger et al., 2022). Few studies looked at the use of everolimus or sirolimus as a treatment of CLAD. Cahill et al. found that in patients with rapidly declining pulmonary function, sirolimus resulted in stabilization or improvement of FEV1 slope (Cahill et al., 2003). Everolimus also improved the FEV1 slope 3 and 6 months after versus before treatment in a study by Fernandez et al. (David Iturbe et al., 2019). Patrucco et al. also found stabilization in FEV1 in CLAD patients, however, subgroup analysis showed progressive functional loss in RAS patients (Patrucco et al., 2021). In another small study, three CLAD patients (60%) remained stable after introduction of everolimus, whereas 40% progressed (Turkkan et al., 2022). Nonetheless, side effects often necessitated discontinuation of mTOR inhibitors (Bos et al., 2021; Cahill et al., 2003; Kneidinger et al., 2022).

D. Belatacept and Basiliximab

Little is known about the use of these two agents for CLAD. Belatacept is a selective CD80/86-CD28 T-cell costimulation blocker widely used in kidney transplantation for induction and maintenance immunosuppression (Masson et al., 2014). The role of belatacept in the setting of lung transplantation remains uncertain with only a few small studies reporting its use in maintenance immunosuppression as part of a calcineurin inhibitor-sparing regimen (Huang et al., 2022; Iasella et al., 2018; Timofte et al., 2016), and a conference abstract on antibody-mediated rejection (Zaffiri et al., 2022), while data in CLAD is lacking. Importantly, one randomized controlled trial with 27 lung transplant patients had to be discontinued prematurely due to increased rates of death in the belatacept arm (Huang et al., 2022).

Basiliximab, a chimeric monoclonal antibody that selectively binds to the α–subunit (CD25) of interleukin-2 receptors, is used for induction therapy in lung transplantation (Small et al., 2022). In addition, there are some case series describing its use in maintenance immunosuppression to avoid calcineurin inhibitor-related nephrotoxicity (Högerle et al., 2016; Kim et al., 2021; Ross et al., 2020). Again, there is no data on any potential benefit in CLAD.

E. TNF-Alpha Inhibitors

Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) is a cytokine that acts as a major regulator of inflammatory reactions via the initiation of signal transduction pathways leading to cytotoxicity and upregulation of various cytokines, chemokines and growth factors (Jang et al., 2021). TNFα is also a key factor in the pathogenesis of CLAD (Bos et al., 2022b).

Several TNFα inhibitors are used for the treatment of inflammatory and autoimmune conditions, such as the monoclonal antibodies infliximab, adalimumab, certolizumab, and golimumab, and the recombinant fusion protein etanercept (Jang et al., 2021). Some of these have also been tested in solid organ transplants to mediate inflammatory responses in ischemia-reperfusion injury and rejection (Pascher and Klupp, 2005).

Anti-TNF agents are generally well tolerated, with common adverse effects being minor. General side effects include infusion-related reactions, injection site reactions, anemia, transaminitis, and mild infections; although there is a risk of severe infections and possibly an increased risk of malignancies, especially lymphomas and non-melanoma skin cancers (Jang et al., 2021).

1. Evidence in CLAD

Next to a few preclinical animal studies (Alho et al., 2003; Aris et al., 2002; Smith et al., 2001), there is one proof-of-concept study that reported the use of infliximab (3 mg/kg i.v. at 0-2-6 weeks minimally) in five patients with progressive BOS (Borthwick et al., 2013). FEV1 and 6-minute walk distance improved in four patients and stabilized in a fifth patient with rapid lung function decline. All patients remained stable for at least 18 months. Infliximab was generally well tolerated; one patient developed a fungal infection (Borthwick et al., 2013).

F. Extracorporeal Photopheresis

ECP is a leukapheresis-based immunomodulatory procedure, currently approved for the management of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, GvHD and rejection after solid organ transplantation (Hage et al., 2021). ECP is a procedure in which whole blood is collected from the patient and circulating leukocytes are removed by density centrifugation. The collected buffy coat is then treated with a photosensitizing agent (i.e., 8-methoxypsoralen) and exposed to UV A light before reinfusion into the patient (Cho et al., 2018). The exact mechanisms of therapeutic action are elusive, but ECP is thought to induce apoptosis of lymphoid cells, largely natural killer cells and T cells, and differentiation of activated monocytes into immature dendritic cells which in turn stimulate phagocytosis of lymphoid cells, and maturation and presentation of antigenic peptides (so-called transimmunization). Furthermore, ECP might modify the cytokine profile with induction of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, transforming growth factor beta) and reduction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor alpha), and stimulate upregulation of regulatory T cells (Cho et al., 2018). Different schedules are being used, often with a more intensive induction phase, followed by a maintenance schedule. However, the treatment effects after ECP initiation take time to come into effect. Next to this, there is no consensus on how long this therapy should be continued and there is uncertainty as to whether a sustained response can be observed and for how long after cessation. Furthermore, ECP is not reimbursed by health systems or insurance providers in many countries.

1. Evidence in CLAD

There are numerous publications describing the effects of ECP in CLAD, including several studies and various conference abstracts. Two prospective studies are available (Table 1). Firstly, a prospective multicenter study with 31 BOS patients (58% stage 2–3) from ten lung transplant centers (Hage et al., 2021). Rate of FEV1 decline was reduced by 93% at 6 months, with a reduction ≥50% in 95% of patients. Multivariate analysis identified that pre-enrolment FEV1 rate of decline was associated with both 6- and 12-month mortality. Notably, study enrollment was terminated prematurely due to a higher-than-expected mortality rate within the first year after enrollment of 32% and 41% at 6 and 12 months, respectively. There was no difference in mortality between the ECP group and an observational cohort; worth noting, the slope of FEV1 decline pre-enrollment was much steeper in the former group (Hage et al., 2021). Another prospective single-center study by Jaksch et al. included 51 BOS patients and reported FEV1 stabilization (variation <5%) in 61% of patients with an improvement in survival in these patients compared with both non-responders and non-treated BOS patients (Jaksch et al., 2012). Factors associated with inferior treatment response were cystic fibrosis as underlying lung disease and a longer time between transplant and BOS onset (Jaksch et al., 2012).

TABLE 1.

Prospective studies of ECP in BOS

| Reference | Study design and period | Number of patients | CLAD stages | Duration ECP | Median slope FEV1 pre-ECP (ml/month) | Median slope FEV1 post-ECP (ml/month) | Response rate to ECP | Mortality within study | Predictors of response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hage et al., 2021 | Prospective, multicenter, 04/2015–07/2016 | 31 BOS ECP 13 BOS controls (7 crossover) |

BOS 1 42% BOS 2 29% BOS 3 29% |

6 months | Mean -136 ± 117 | Mean -10 ± 58† | - Reduction ≥50% in 95% of patients (data 16/30, 63%) - Higher rate FEV1 decline in non-survivors at 6 and 12 months post-ECP start |

39% and 48% at 6 and 12 months (87% CLAD, 13% infection) |

FEV1 rate of decline pre-ECP correlated with 6- and 12-month mortality. |

| Jaksch et al., 2012 | Prospective, single-center, 01/2000-06/2010 | 51 BOS ECP 143 BOS controls At least 3 months treatment |

BOS 1 12% BOS 2 20% BOS 3 68% |

3 months (51 patients) 12 months (25 patients) |

−123† | −14* and -18‡ | - FEV1 improvement in 30% (12% 3–6 months, 18% >12 months) - Stabilization in 31% |

Negative impact: BOS onset >3 years post-transplant, rapid FEV1 decline pre-ECP, BOS stage, cystic fibrosis as primary lung disease. Overall survival: response to ECP. |

Period of 3*, 6† or 12‡ months pre-/post-ECP initiation.

Furthermore, several recent retrospective single-center studies included both BOS and RAS patients, varying from 12 to 65 CLAD patients per study, of whom the majority had CLAD stage 2–3 (Table 2). Del Fante, Greer, and Vazirani all reported a significant reduction in rate of lung function decline (Del Fante et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2013; Vazirani et al., 2021) with a stabilization or improvement (≥10%) in lung function around 54%–60% (Del Fante et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2013). Notably, patients who did not complete the initial 3-month induction treatment or at least eight procedures were excluded in Greer’s (Greer et al., 2013) and Del Fante’s (Del Fante et al., 2015) studies, respectively. Robinson et al. looked at the lung function trajectory after forced cessation of ECP due to loss of reimbursement in 12 CLAD patients who had undergone long-term ECP treatment (median 1001 days) (Robinson et al., 2017). FEV1 significantly and rapidly declined within 6 months of cessation, while lung function was stable in all patients before. Moreover, 58% died within 12 months mostly due to CLAD progression (Robinson et al., 2017).

TABLE 2.

Retrospective, single-center studies of ECP in CLAD

| Reference | Study design and period | Number of patients | CLAD stages | Duration ECP | Median slope FEV1 pre-ECP (ml/month) | Median slope FEV1 post-ECP (ml/month) | Response rate to ECP | Mortality within study | Predictors of response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baskaran et al., 2014 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2000–06/2011 |

88 BOS | 6 months | −127† | −47† | −63% reduction in rate of FEV1 decline, 23% stabilized or improved (data 69/88, 78%) | 19% at 2 years | No impact: % reduction of DSA or lung-associated self-antigens, or level of cytokines (IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, IL-17, IFN-γ, IP-10, MCP-1). | |

| Benden et al., 2008 | Retrospective, single-center, 1997–2007 |

12 BOS | BOS 1 42% BOS 2 17% BOS 3 42% |

12 cycles | 112 From baseline until start ECP |

12 After 12 cycles of ECP until last value |

33% (100% CLAD) Median OS 4.9 years after ECP start (BOS + ACR cohort) |

||

| Del Fante et al., 2015 | Retrospective, single-center, 02/2003–12/2013 |

34 BOS 14 RAS 58 controls At least 8 procedures |

CLAD 1 58% CLAD 2 21% CLAD 3 21% |

Median 26 (IQR 17-42) procedures | −48 (95% CI -61; -36)† | −19 (95% CI -35; -3)† −4 (95% CI -15; +7) 12-24 months post ECP start |

−60% stable graft function at 6 months | 42% (85% CLAD, 5% cancer, 10% other), no difference ECP group and controls | Negative impact: rapid decliners (>100 ml FEV1/month), time from transplant to CLAD onset. No impact: CLAD phenotype, CLAD stage, time from CLAD onset to ECP. Overall survival: RAS (trend: P = 0.06), no influence CLAD stage, rapid decline, time CLAD diagnosis and start ECP. |

| Greer et al., 2013 | Retrospective, single-center, 11/2007–09/2011 | 65 CLAD At least 3 months treatment |

CLAD 0p 5% CLAD 1 9% CLAD 2 32% CLAD 3 54% |

Median 15 (IQR 12–18) cycles | −12% improvement (≥10%) −42% stabilization in FEV1 |

2-year OS 97% in responders | Negative impact: rapid decline (>100 ml FEV1/month), RAS phenotype, ≤15% BAL neutrophils. No impact: CLAD stage, time to CLAD diagnosis and initiation of ECP. Overall survival: response to ECP. |

||

| Isenring et al., 2017 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2008–12/2012 Update from 2008 study(Benden et al., 2008) |

9 of initial 12 BOS, 2 continued ECP after re-transplant | BOS 1 44% BOS 2 11% BOS 3 44% |

Range 48–119 months | - Progression in 17% still alive at end of follow up | 33% (67% cancer, 33% CLAD) | Negative impact: CLAD stage 2-3. | ||

| Karnes et al., 2019 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2000–12/2007 Update from 2010 study(Morrell et al., 2010) |

60 BOS | See(Morrell et al., 2010) | 6 months | See(Morrell et al., 2010) | See(Morrell et al., 2010) | See(Morrell et al., 2010) | 17% <6 months, 50% <16 months of ECP initiation | 12-fold higher chance of response if FEV1 decline >40 ml/months pre-ECP. FEV1 at start ECP correlated linearly with time to mortality and mortality at 16 months after start ECP. |

| Leroux et al., 2022 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2012–07/2019 |

12 BOS ECP 13 BOS controls At least 6 months treatment |

BOS 1 33% BOS 2 25% BOS 3 42% |

Median 32 (IQR 12-58) months | −44 (IQR -112; -8)† | +11 (IQR -0.8; +41)† | −75% FEV1 stabilization (±5%) within 12 months −63% improvement (>5%), 25% stabilization within 24 months of initiation - Lower risk of >20% drop in FEV1 in ECP-treated group versus control decliners. |

33% (100% sudden death) | No impact: rate of FEV1 decline pre-ECP, time BOS diagnosis and ECP start. |

| Meloni et al., 2007 | Retrospective, single-center | 5 BOS At least 4 months treatment |

BOS 2 60% BOS 3 40% |

Range around 4–32 months | −60% FEV1 stabilization | 40% (100% infection) | Tregs stabilized or increased in patients who stabilized and declined in non-responders. | ||

| Moniodis et al., 2018 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2005–12/2014 |

13 BOS ECP 4 RAS ECP 9 BOS alemtuzumab 5 RAS alemtuzumab 78 controls |

CLAD 1 88% CLAD 2 12% |

6 months | −122 (IQR -164; -77)* | −27 (IQR -82; -36)* and -12 (-56–22)† | - Significant reduction in rate of FEV1 decline at 3 and 6 months | OS at 6 months 0.82 (95% CI 0.55–0.94) | Negative impact: RAS phenotype. |

| Morrell et al., 2010 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2000–12/2007 |

60 BOS | BOS 1 8% BOS 2 33% BOS 3 58% |

6 months | −116† | −29† and -21‡ | - Reduction of FEV1 rate of decline in 79% - FEV1 improved in 25% at 6 and 12 months (data 56/60, 93%) |

Median OS 2.6 years after ECP start | No impact: BOS stage, time of BOS onset, rate of FEV1 decline pre-ECP. |

| Pecoraro et al., 2017 | Retrospective, single-center, 11/2013–06/2016 |

15 BOS 39 controls |

BOS 1 7% BOS 2 27% BOS 3 67% |

13 cycles | −80% FEV1 stabilization - FEV1 significantly higher 12 months after start ECP compared with controls |

13% (50% CLAD, 50% cancer), better OS in ECP versus controls | No impact: CLAD stage, time CLAD onset, time BOS diagnosis and ECP. | ||

| Robinson et al., 2017 | Retrospective, single-center, Patients who had to stop ECP end 2014 due to stop reimbursement |

10 BOS 2 RAS |

BOS 2 30% BOS 3 70% RAS unknown |

Median 44 (range 8–142) procedures | −13 (range -8–110) | −17 (range -6–163) | - FEV1 rapidly declined within 6 months after ECP cessation | 58% within 12 months of treatment cessation (43% CLAD, 43% infection + CLAD, 14% cancer) | |

| Salerno et al., 1999 | Retrospective, single-center, 1992–1998 |

8 BOS 20 controls |

BOS 3 88% | Median 6 (range 3–13) months | Range -366; +8 From baseline until start ECP |

Range -30; +44 | −71% FEV1 stabilization or improvement −63% clinical stabilization |

50% alive without retransplant after median 36 months | |

| Vazirani et al., 2021 | Retrospective, single-center, 01/2013–06/2018 | 5 BOS 2 RAS 5 mixed |

CLAD 2 17% CLAD 3 83% |

Mean 9 (95% CI 5; 12) ml/day in responders Mean 7 (4; 10) m/day in non-responders |

Mean 1.4 (95% CI 0; 4) ml/day In responders Mean 5 (3; 7) ml/day in non-responders |

−67% (<20% decrease in FEV1 within 6 weeks of ECP start) | Graft-failure in all non-responders (33%) within 6 months of ECP start | Negative impact: female sex, low baseline neutrophil count (< 1.9 × 109/L), prior exposure to ATG. No impact: CLAD phenotype. |

OS, overall survival; RAS, restrictive allograft syndrome. Period of 3*, 6† or 12‡ months pre-/post-ECP initiation.

Survival seemed to correlate with response to ECP (Greer et al., 2013; Vazirani et al., 2021) though predictors of response varied across the studies. Some studies documented that female sex (Vazirani et al., 2021), a rapid decline in FEV1 pre-ECP (Del Fante et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2013), RAS phenotype (Greer et al., 2013), a low baseline neutrophil count in blood (< 1.9 × 109/L) (Vazirani et al., 2021) or bronchoalveolar lavage (≤15%) (Greer et al., 2013), prior exposure to ATG (Vazirani et al., 2021), and time from transplant to CLAD onset (Del Fante et al., 2015) adversely affected response to ECP. Although others could not find an impact of sex (Del Fante et al., 2015), CLAD phenotype (Del Fante et al., 2015; Vazirani et al., 2021), timing of CLAD onset (Greer et al., 2013), CLAD stage (Del Fante et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2013), or time from CLAD diagnosis to ECP initiation (Del Fante et al., 2015; Greer et al., 2013).

These findings corroborate the results from multiple previous studies where ECP was administered for BOS, as summarized in Table 2. Again, in these studies, that included between 5 and 88 patients, there was a significant reduction in FEV1 decline with in most studies a stabilization in lung function in 60%–80% of patients (Baskaran et al., 2014; Benden et al., 2008; Isenring et al., 2017; Karnes et al., 2019; Leroux et al., 2022; Meloni et al., 2007; Moniodis et al., 2018; Morrell et al., 2010; Pecoraro et al., 2017; Salerno et al., 1999). Lastly, there are numerous conference abstracts reporting similar outcomes.

In all published data to date, ECP has generally been found to be a safe treatment without significant adverse effects.

In summary, clinical evidence suggests that ECP is associated with improvement or stabilization in lung function and decreases the rate of lung function decline in BOS, without an increased risk of infections or significant adverse events, with some studies also showing improved survival. Given that this response appeared to be independent of CLAD duration as well as stage at treatment initiation in most studies, ECP should be considered a viable second-line treatment option.

Large prospective clinical trials are needed to help predict response to therapy, and ultimately guide the placement of ECP in the treatment algorithm for CLAD. The results of a multicentre randomized controlled trial comparing ECP plus standard of care versus standard of care alone in patients with progressive CLAD in the UK (NIHR130612) are therefore eagerly awaited.

IV. B-cell-Directed Treatment

The effects of immunomodulatory and lymphodepleting treatments primarily targeting B cells and anti-human leukocyte and donor-specific antibodies, such as rituximab (anti-CD20), bortezomib and carfilzomib (both proteasome inhibitors), are mainly described in the context of antibody-mediated rejection (Neuhaus et al., 2022; Pham et al., 2021; Razia et al., 2022; Roux et al., 2016; Vacha et al., 2017; Yamanashi et al., 2020). However, evidence for their relevance as part of CLAD treatment is lacking. We can speculate that these agents might have a beneficial effect when given in combination with other therapies, as antibodies and various subsets of B cells are involved in CLAD pathogenesis (Bos et al., 2022c). However, combination therapy may increase the complexity of treatment and risk of side effects.

V. Future Directions

Interestingly, there are many similarities between CLAD and pulmonary chronic GvHD after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, as described elsewhere (Bos et al., 2022a). This could imply that therapies developed for (pulmonary) GvHD may also be effective in CLAD, and vice versa, which deserves further attention. Indeed, efforts are needed from both academia and industry for devoted development of novel (more efficacious and safer) immunosuppressive agents, or drug repurposing, along with innovative trial designs with relevant clinical endpoints focusing on these devastating conditions, which are an unmet need.

A. Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors

Imatinib and ibrutinib are two tyrosine kinase inhibitors commonly used in chronic GvHD with some evidence for their use in pulmonary GvHD. Imatinib (100–400 mg daily) seemed to stabilize FEV1 in some BOS patients after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, and in subgroup analyses of some patients treated with imatinib for chronic GvHD (Magro et al., 2009; Olivieri et al., 2013, 2009; Parra Salinas et al., 2021; Stadler et al., 2009; Sánchez-Ortega et al., 2016; Watanabe et al., 2015). There is minimal data from preclinical animal studies regarding the use of imatinib in CLAD, showing that imatinib improved luminal airway obstruction in experimental bronchiolitis obliterans (Pandolfi et al., 2020; von Suesskind-Schwendi et al., 2013; Watanabe et al., 2017), possibly through reduction of migration and differentiation of fibrocytes in the allograft (Watanabe et al., 2017).

Currently, no data are available on ibrutinib (140–420 mg daily) in CLAD nor from pulmonary GvHD-specific studies, although some stabilization of lung function was observed in subgroup analyses of chronic GvHD studies (Doki et al., 2021; Kaloyannidis et al., 2021). More data on the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in pulmonary GvHD and CLAD are needed to decide whether there is sufficient efficacy in stabilizing lung function or not.

B. Janus Kinase Inhibitors

Ruxolitinib (5–10 mg b.d.) is a relatively new JAK-1/2 inhibitor used with good results in chronic GvHD and some promising results in pulmonary GvHD as well (Streiler et al., 2020; Zhao et al., 2021). There is currently no data in CLAD yet. Promising results of another JAK-1 inhibitor, itacitinib (400–600 mg daily), in a phase 1 study with 23 BOS patients were recently presented, demonstrating that treatment with itacitinib resulted in stabilization of FEV1 in all participants who continued treatment with an absolute increase of ≥10% in 22% of patients (Diamond et al., 2022). Further results from phase 2 as well as results from a phase 2 trial in steroid-refractory chronic GvHD (NCT04200365) and phase 1 trial in pulmonary GvHD (NCT04239989) are awaited.

C. Rho Kinase Inhibitors

Belumosudil (200–400 mg daily) is a rho kinase inhibitor recently approved for the treatment of chronic GvHD after failure of at least two prior lines of systemic therapy in the USA, and will soon be available in the UK as well. Its efficacy merits further investigation in both pulmonary GvHD and CLAD, as in two recent phase 2 chronic GvHD studies, it resulted in a ≥ 10% increase in FEV1 in 55% of 47 (Cutler et al., 2021) and 71% of 17 (Jagasia et al., 2021) subjects with pulmonary GvHD.

D. MEK Inhibitors

MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) inhibitors inhibit the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase enzymes MEK1 and/or MEK2. Trametinib, a MEK-1/2 inhibitor, ameliorated the onset of GvHD (Itamura et al., 2021, 2016) and chronic rejection after lung transplantation (Takahagi et al., 2019) in some animal studies, highlighting the need for further translational research.

E. IL-6 Inhibitors

The humanized IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab prevents binding of IL-6 to its receptor and signal transducer glycoprotein 130 complex, inhibiting downstream JAK/STAT signaling, and has been used in a limited number of studies after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for both acute and chronic GvHD prevention and treatment (Drobyski et al., 2011; Ganetsky et al., 2019; Kattner et al., 2020; Kennedy et al., 2021; Melgarejo-Ortuño et al., 2021; Roddy et al., 2016; Yucebay et al., 2019). In a study of chronic GvHD patients (8 mg/kg q4w), the response rate for pulmonary GvHD ranged between 17 and 33% within the first year of treatment initiation (Kattner et al., 2020). One case report is available in the setting of CLAD in a patient transplanted for COPA syndrome, a genetic disorder leading to upregulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines (primarily IL-1β and IL-6) and development of interstitial lung disease (Riddell et al., 2021). Involvement of IL-6 in the pathogenesis of CLAD has also been documented (Bos et al., 2022b), and tocilizumab (4 mg/kg monthly for 3 doses) effectively suppressed IL-6 upregulation though without clinical improvement in this patient (Riddell et al., 2021). Moreover, one conference abstract demonstrated stabilization of lung function in nine CLAD patients who received tocilizumab (4–8 mg/kg monthly) for at least 3 months, but in combination with other therapies such as ATG, rituximab and immunoglobulins (Ross et al., 2019). Another conference abstract reported reduced onset of rejection when tocilizumab was added in a preclinical animal model, possibly via transient expansion of regulatory T cells (Aoyama et al., 2016).

Further evaluation of a potential role for tocilizumab in the treatment of pulmonary GvHD and CLAD in larger trials is warranted.

F. Inhaled Liposomal Cyclosporine A

Local intrapulmonary lymphocyte suppression and immunomodulation via nebulized immunosuppressive drugs, such as liposomal cyclosporine, may be an elegant way to prevent systemic side effects and ensure high local efficacy in CLAD. Following prior studies demonstrating a possible beneficial effect for CLAD prevention (Groves et al., 2010; Iacono et al., 2019; Neurohr et al., 2022), currently two studies in CLAD are ongoing (BOSTON-1 and BOSTON-2) which results are eagerly awaited.

VI. Conclusion

CLAD is the leading cause of death beyond the first year after lung transplantation (Chambers et al., 2019). Some patients experience an accelerated loss of lung function, whereas others have a slower progression with intermittent loss of function (Belperio et al., 2009; Sato et al., 2013). Several therapeutic options have been used in attempts to prevent, reverse, or slow CLAD progression; however, there are only limited effective therapeutic options and there is currently no consensus on the most effective option (Verleden et al., 2019). Interpretation of these results is overshadowed by the fact that randomized controlled trials are almost universally lacking; thus, it is unclear whether the attenuated rate of FEV1 decline represents true treatment response or merely the natural course of the disease. In advanced CLAD stages, a less pronounced decline in lung function may also be due to limited residual lung function (Kotecha et al., 2021). However, some studies showed sustained lung function stabilization (Jaksch et al., 2012; Kotecha et al., 2021; Moniodis et al., 2018; Robinson et al., 2017) or improvement even in advanced CLAD (Del Fante et al., 2015; Girgis et al., 2020; January et al., 2019; Lebeer et al., 2020; Thachuthara-George et al., 2015; Vazirani et al., 2021). Secondly, comparing studies is complicated because of different treatment dosages and regimens used, also with respect to other transplant-related drugs and center-specific policies. Furthermore, the comparison of results is hampered by the use of different definitions of CLAD prior to an international consensus and of treatment response, highlighting the need for standardization and harmonization.

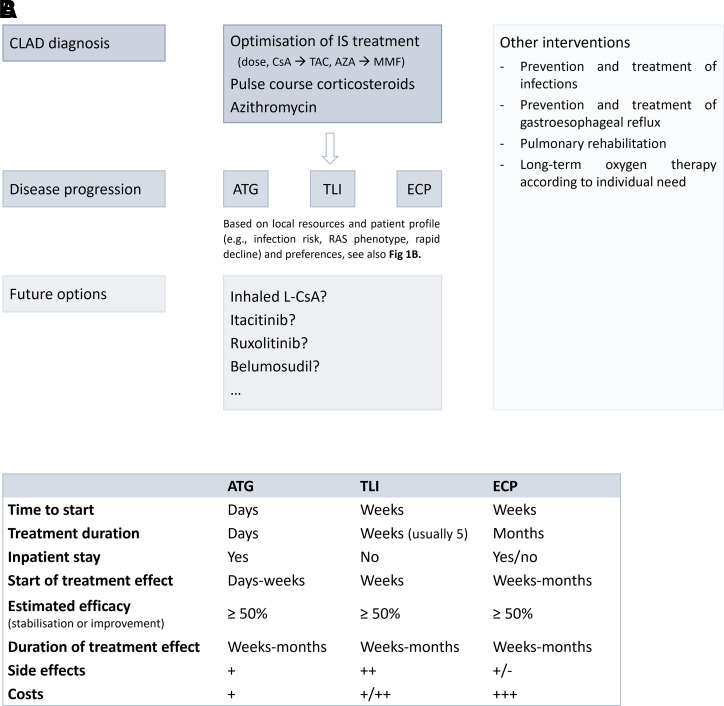

Knowledge of the mechanisms-of-action of existing drugs is an essential prerequisite that allows us to understand how a treatment works, but also the expected side effects, and may allow identification of other treatment options, targeting similar immune cells or pathways. Taking into account the efficacy and risk of side effects, we believe that ECP, ATG, and TLI currently have the most promising data to suggest they could be considered second-line lymphocyte-targeted treatment options for CLAD patients (Fig. 2). As intercurrent infections may drive CLAD onset and progression, however, the need for safer lymphocyte-directed therapies has become clear.

Fig. 2.

Lymphocyte depleting and/or modulating therapies in CLAD. (A) Suggested treatment algorithm for CLAD based on existing data taking into account the efficacy and risk of side effects as well as some potential safer future options that require more investigation. (B) Overview of features associated with ATG, TLI, and ECP treatment. Which therapeutic option is chosen mainly depends on local resources and patient profile (e.g., risk of infection, CLAD phenotype, rapid versus slow lung function decline) and preferences. AZA, azathioprine; CsA, cyclosporine A; IS, immunosuppressive; L-CsA, liposomal cyclosporine A; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; TAC, tacrolimus.

To improve future treatments in lung transplantation, standardization of care, trial protocols, and relevant study endpoints, which include lung function, overall survival and preferably also quality of life and exercise capacity between different transplant centers, are key. Larger randomized controlled multi-center trials, preferably also including RAS patients, with longer follow up as well as platform trials moving rapidly between investigational agents and further investigation of novel treatment options are urgently needed to define the most appropriate treatment algorithm for CLAD. A list of currently ongoing clinical trials is provided in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Ongoing clinical trials in CLAD using lymphocyte depleting or modulating drugs (registered at clinicaltrials.gov or NIHR)

| Study identifier, country | Title | Study design |

|---|---|---|

| NCT02181257, USA | Extracorporeal Photopheresis for the Management of Progressive Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome in Medicare-Eligible Recipients of Lung Allografts | Randomized controlled open-label multicenter trial |

| NIHR130612, UK | Extracorporeal Photophoresis in the treatment of Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction: a randomized controlled trial (E-CLAD UK) | Randomized controlled open-label multicenter trial |

| NCT04792294, Austria | Multicenter Analysis of Efficacy and Outcomes of Extracorporeal Photopheresis as Treatment of Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction | Retrospective multicenter trial |

| NCT03978637, USA, Canada, Belgium | An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Phase 1/2 Study Evaluating the Safety and Efficacy of Itacitinib in Participants With Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome Following Lung Transplantation | Phase 1–2 open-label multicenter trial |

| NCT04640025, USA, Canada, Europe | A Phase 2, Open-Label, Multicenter, Rollover Study to Provide Continued Treatment of Participants Previously Enrolled in Studies of Itacitinib (INCB039110) | Phase 2 open-label multicenter trial |

| NCT03657342, USA and Europe | A Phase III Clinical Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy / Safety of Liposomal Cyclosporine A + Standard of Care (SoC) versus SoC Alone in Treating Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction / Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Patients Post Single Lung Transplant (BOSTON-1) | Phase 3 randomized controlled multicenter trial |

| NCT03656926, USA and Europe | A Phase III Clinical Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy / Safety of Liposomal Cyclosporine A + Standard of Care (SoC) versus SoC Alone in Treating Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction / Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Patients Post Double Lung Transplant (BOSTON-2) | Phase 3 randomized controlled multicenter trial |

| NCT04039347, USA and Europe | A Phase III, Extension Clinical Trial to Demonstrate Efficacy and Safety of Liposomal Cyclosporine A Via the PARI Investigational eFlow Device and SoC in Treating Bronchiolitis Obliterans in Patients Post Single or Double Lung Transplant | Phase 3 open-label multicenter trial |

Abbreviations

- ATG

anti-thymocyte globulin

- BOS

bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome

- CLAD

chronic lung allograft dysfunction

- ECP

extracorporeal photopheresis

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in one second

- GvHD

graft-versus-host disease

- JAK

Janus kinase

- MEK

mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- RAS

restrictive allograft syndrome

- TLI

total lymphoid irradiation

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor alpha

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Bos, Vos.

Performed data analysis: Bos.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Bos, Pradère, Beeckmans, Zajacova, Vanaudenaerde, Fisher, Vos.

Footnotes

This work received no external funding. The following authors are supported by a research fellowship, but received no specific funding for the current review: S.B. is funded by the Paul Corris International Clinical Research Training Scholarship. B.M.V. is funded by the KU Leuven (C24/050). A.J.F. is funded in part by the National Institute for Health Research Blood and Transplant Research Unit (NIHR BTRU) in Organ Donation and Transplantation at the University of Cambridge in collaboration with Newcastle University and in partnership with NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or NHSBT. R.V. is a senior clinical research fellow of the Fund for Scientific Research Flanders (FWO) (1803521N) and supported by a research grant from FWO (G060322N).

No author has an actual or perceived conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

References

- Afolabi A, Healy PG, Corris PA, Dark JH (1996) The role of total lymphoid irradiation in the treatment of obliterative bronchiolitis-2 years on. J Heart Lung Transplant 15:S102. [Google Scholar]

- Ahlmann M, Hempel G (2016) The effect of cyclophosphamide on the immune system: implications for clinical cancer therapy. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 78:661–671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alho HS, Maasilta PK, Harjula AL, Hämmäinen P, Salminen J, Salminen US (2003) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha in a porcine bronchial model of obliterative bronchiolitis. Transplantation 76:516–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alqarni AM, Zeidler MP (2020) How does methotrexate work? Biochem Soc Trans 48:559–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amrouche K, Jamin C (2017) Influence of drug molecules on regulatory B cells. Clin Immunol 184:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama A, Tonsho M, Smith R-N, Colvin R, Dehnadi A, Madsen J, Cosimi A, Benichou G, Kawai T, Allan J (2016) Non-human primate lung allograft survival is prolonged by IL-6 inhibition and ATG treatment possibly through expansion of peripheral regulatory T cells. Am J Transplant 16(205, Supplement 203.). [Google Scholar]

- Arbeláez L, Giraldo A, Altabas M, Coronil O, Bravo Masgoret C, Loor K, Giralt J (2014) Total lymphoid irradiation in bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. Radiother Oncol 111:S136. [Google Scholar]

- Aris RM, Walsh S, Chalermskulrat W, Hathwar V, Neuringer IP (2002) Growth factor upregulation during obliterative bronchiolitis in the mouse model. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166:417–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes H, Holland AE, Westall GP, Goh NS, Glaspole IN (2018) Cyclophosphamide for connective tissue disease-associated interstitial lung disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD010908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskaran G, Tiriveedhi V, Ramachandran S, Aloush A, Grossman B, Hachem R, Mohanakumar T (2014) Efficacy of extracorporeal photopheresis in clearance of antibodies to donor-specific and lung-specific antigens in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 33:950–956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedoui Y, Guillot X, Sélambarom J, Guiraud P, Giry C, Jaffar-Bandjee MC, Ralandison S, Gasque P (2019) Methotrexate an Old Drug with New Tricks. Int J Mol Sci 20:5023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belperio JA, Weigt SS, Fishbein MC, Lynch JP 3rd (2009) Chronic lung allograft rejection: mechanisms and therapy. Proc Am Thorac Soc 6:108–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benden C, Speich R, Hofbauer GF, Irani S, Eich-Wanger C, Russi EW, Weder W, Boehler A (2008) Extracorporeal photopheresis after lung transplantation: a 10-year single-center experience. Transplantation 86:1625–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowmick M, Auckbarallee F, Edgar P, Ray A, Dasgupta S (2016) Humanized Monoclonal Antibody Alemtuzumab Treatment in Transplant. Exp Clin Transplant 14:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher H, Costard-Jäckle A, Möller F, Hirt SW, Cremer J (2002) Methotrexate rescue therapy in lung transplantation. Transplant Proc 34:3255–3257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick LA, Corris PA, Mahida R, Walker A, Gardner A, Suwara M, Johnson GE, Moisey EJ, Brodlie M, Ward C, et al. (2013) TNFα from classically activated macrophages accentuates epithelial to mesenchymal transition in obliterative bronchiolitis. Am J Transplant 13:621–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos S, Beeckmans H, Vanstapel A, Sacreas A, Geudens V, Willems L, Schreurs I, Vanaudenaerde BM, Schoemans H, Vos R (2022a) Pulmonary graft-versus-host disease and chronic lung allograft dysfunction: two sides of the same coin? Lancet Respir Med 10:796–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos S, De Sadeleer LJ, Yserbyt J, Dupont LJ, Godinas L, Verleden GM, Ceulemans LJ, Vanaudenaerde BM, Vos R (2021) Real life experience with mTOR-inhibitors after lung transplantation. Int Immunopharmacol 94:107501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos S, Filby AJ, Vos R, Fisher AJ (2022b) Effector immune cells in chronic lung allograft dysfunction: A systematic review. Immunology 166:17–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos S, Milross L, Filby AJ, Vos R, Fisher AJ (2022c) Immune processes in the pathogenesis of chronic lung allograft dysfunction: identifying the missing pieces of the puzzle. Eur Respir Rev 31:22060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos S, Vos R, Van Raemdonck DE, Verleden GM (2020) Survival in adult lung transplantation: where are we in 2020? Curr Opin Organ Transplant 25:268–273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill BC, Somerville KT, Crompton JA, Parker ST, O’Rourke MK, Stringham JC, Karwande SV (2003) Early experience with sirolimus in lung transplant recipients with chronic allograft rejection. J Heart Lung Transplant 22:169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacon RA, Corris PA, Dark JH, Gibson GJ (2000) Tests of airway function in detecting and monitoring treatment of obliterative bronchiolitis after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 19:263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DC, Cherikh WS, Harhay MO, Hayes D Jr, Hsich E, Khush KK, Meiser B, Potena L, Rossano JW, Toll AE, et al. ; International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (2019) The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-sixth adult lung and heart-lung transplantation Report-2019; Focus theme: Donor and recipient size match. J Heart Lung Transplant 38:1042–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho A, Jantschitsch C, Knobler R (2018) Extracorporeal Photopheresis-An Overview. Front Med (Lausanne) 5:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler C, Lee SJ, Arai S, Rotta M, Zoghi B, Lazaryan A, Ramakrishnan A, DeFilipp Z, Salhotra A, Chai-Ho W, et al. (2021) Belumosudil for chronic graft-versus-host disease after 2 or more prior lines of therapy: the ROCKstar Study. Blood 138:2278–2289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Date H, Lynch JP, Sundaresan S, Patterson GA, Trulock EP (1998) The impact of cytolytic therapy on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. J Heart Lung Transplant 17:869–875. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturbe DF, De Pablo AG, Escobar KFR, Ruiz FS, Pérez VG, Mora VMC, Fernández SMR, Alonso RM, Cifrián JM (2019) Everolimus as a treatment of Chronic Lung Alograft Rejection (CLAD) in lung transplantation. Eur Respir J 54:PA1103. [Google Scholar]

- Del Fante C, Scudeller L, Oggionni T, Viarengo G, Cemmi F, Morosini M, Cascina A, Meloni F, Perotti C (2015) Long-term off-line extracorporeal photochemotherapy in patients with chronic lung allograft rejection not responsive to conventional treatment: A 10-year single-centre analysis. Respiration 90:118–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond DA, Michalski JM, Lynch JP, Trulock EP 3rd (1998) Efficacy of total lymphoid irradiation for chronic allograft rejection following bilateral lung transplantation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 41:795–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond JM, Vos R, Budev M, Goldberg HJ, Criner GJ, Pilewski JM, Singer LG, Weigt SS, Lakshminarayanan M, Schaub RL, et al. (2022) Efficacy and Safety of the Janus Kinase 1 Inhibitor Itacitinib (ITA) in Patients with Bronchiolitis Obliterans (BOS) Syndrome Following Double Lung Transplant. J Heart Lung Transplant 41:S113. [Google Scholar]

- Doki N, Toyosaki M, Shiratori S, Osumi T, Okada M, Kawakita T, Sawa M, Ishikawa T, Ueda Y, Yoshinari N, et al. (2021) An Open-Label, Single-Arm, Multicenter Study of Ibrutinib in Japanese Patients With Steroid-dependent/Refractory Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. Transplant Cell Ther 27:867.e1–867.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobyski WR, Pasquini M, Kovatovic K, Palmer J, Douglas Rizzo J, Saad A, Saber W, Hari P (2011) Tocilizumab for the treatment of steroid refractory graft-versus-host disease. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 17:1862–1868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dusmet M, Maurer J, Winton T, Kesten S (1996) Methotrexate can halt the progression of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in lung transplant recipients. J Heart Lung Transplant 15:948–954. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emadi A, Jones RJ, Brodsky RA (2009) Cyclophosphamide and cancer: golden anniversary. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 6:638–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensor CR, Rihtarchik LC, Morrell MR, Hayanga JW, Lichvar AB, Pilewski JM, Wisniewski S, Johnson BA, D’Cunha J, Zeevi A, et al. (2017) Rescue alemtuzumab for refractory acute cellular rejection and bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. Clin Transplant 31: 10.1111/ctr.12899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine NM, Kushwaha SS (2016) Recent Advances in Mammalian Target of Rapamycin Inhibitor Use in Heart and Lung Transplantation. Transplantation 100:2558–2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher AJ, Rutherford RM, Bozzino J, Parry G, Dark JH, Corris PA (2005) The safety and efficacy of total lymphoid irradiation in progressive bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 5:537–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganetsky A, Frey NV, Hexner EO, Loren AW, Gill SI, Luger SM, Mangan JK, Martin ME, Babushok DV, Drobyski WR, et al. (2019) Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe steroid-refractory acute graft-versus-host disease of the lower gastrointestinal tract. Bone Marrow Transplant 54:212–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng-Cahuayme AAA, Sáez-Giménez B, Altabas-González M, Vázquez-Varela M, Berastegui-Garcia C, Sagredo JG, Zapata-Ortega M, Recalde-Vizcay E, López-Meseguer M (2022) Efficacy And Safety of Total Lymphoid Irradiation In Different Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction Phenotypes. Clin Transpl 37:14891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girgis R, Sathiyamoorthy G, McDermott J, Lawson C, Kumar A, Hadley R, Leacche M, Murphy E (2020) ALEMTUZUMAB FOR CHRONIC LUNG ALLOGRAFT DYSFUNCTION. Chest 158:A2388. [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb J, Neurohr C, Müller-Quernheim J, Wirtz H, Sill B, Wilkens H, Bessa V, Knosalla C, Porstner M, Capusan C, et al. (2019) A randomized trial of everolimus-based quadruple therapy vs standard triple therapy early after lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 19:1759–1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greer M, Dierich M, De Wall C, Suhling H, Rademacher J, Welte T, Haverich A, Warnecke G, Ivanyi P, Buchholz S, et al. (2013) Phenotyping established chronic lung allograft dysfunction predicts extracorporeal photopheresis response in lung transplant patients. Am J Transplant 13:911–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves S, Galazka M, Johnson B, Corcoran T, Verceles A, Britt E, Todd N, Griffith B, Smaldone GC, Iacono A (2010) Inhaled cyclosporine and pulmonary function in lung transplant recipients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv 23:31–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hage CA, Klesney-Tait J, Wille K, Arcasoy S, Yung G, Hertz M, Chan KM, Morrell M, Goldberg H, Vedantham S, et al. ; EPI Study Group (2021) Extracorporeal photopheresis to attenuate decline in lung function due to refractory obstructive allograft dysfunction. Transfus Med 31:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallek M (2017) Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: 2017 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol 92:946–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HJ, Schechtman K, Askar M, Bernadt C, Mittler B, Dore P, Witt C, Byers D, Vazquez-Guillamet R, Halverson L, et al. (2022) A pilot randomized controlled trial of de novo belatacept-based immunosuppression following anti-thymocyte globulin induction in lung transplantation. Am J Transplant 22:1884–1892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt E, Ging P, Lawrie I, Winward S, Towell S, Gillham C, Egan J, Murray M, Kleinerova J (2019) Total lymphoid irradiation (TLI) for the management of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome (BOS) post lung transplant: A single centre experience. Eur Respir J 54:Supplement 63. [Google Scholar]

- Högerle BA, Kohli N, Habibi-Parker K, Lyster H, Reed A, Carby M, Zeriouh M, Weymann A, Simon AR, Sabashnikov A, et al. (2016) Challenging immunosuppression treatment in lung transplant recipients with kidney failure. Transpl Immunol 35:18–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacono A, Wijesinha M, Rajagopal K, Murdock N, Timofte I, Griffith B, Terrin M (2019) A randomised single-centre trial of inhaled liposomal cyclosporine for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome post-lung transplantation. ERJ Open Res 5:00167–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iasella CJ, Winstead RJ, Moore CA, Johnson BA, Feinberg AT, Morrell MR, Hayanga JWA, Lendermon EA, Zeevi A, McDyer JF, et al. (2018) Maintenance Belatacept-Based Immunosuppression in Lung Transplantation Recipients Who Failed Calcineurin Inhibitors. Transplantation 102:171–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isenring B, Robinson C, Buergi U, Schuurmans MM, Kohler M, Huber LC, Benden C (2017) Lung transplant recipients on long-term extracorporeal photopheresis. Clin Transplant 31:10.1111/ctr.13041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itamura H, Shindo T, Muranushi H, Kitaura K, Okada S, Shin-I T, Suzuki R, Takaori-Kondo A, Kimura S (2021) Pharmacological MEK inhibition promotes polyclonal T-cell reconstitution and suppresses xenogeneic GVHD. Cell Immunol 367:104410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itamura H, Shindo T, Tawara I, Kubota Y, Kariya R, Okada S, Komanduri KV, Kimura S (2016) The MEK inhibitor trametinib separates murine graft-versus-host disease from graft-versus-tumor effects. JCI Insight 1:e86331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivulich S, Paraskeva M, Paul E, Kirkpatrick C, Dooley M, Snell G (2023) Rescue Everolimus Post Lung Transplantation is Not Associated With an Increased Incidence of CLAD or CLAD-Related Mortality. Transpl Int 36:10581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izhakian S, Wasser WG, Fox BD, Vainshelboim B, Reznik JE, Kramer MR (2016) Effectiveness of Rabbit Antithymocyte Globulin in Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction. Transplant Proc 48:2152–2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagasia M, Lazaryan A, Bachier CR, Salhotra A, Weisdorf DJ, Zoghi B, Essell J, Green L, Schueller O, Patel J, et al. (2021) ROCK2 Inhibition With Belumosudil (KD025) for the Treatment of Chronic Graft-Versus-Host Disease. J Clin Oncol 39:1888–1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaksch P, Scheed A, Keplinger M, Ernst MB, Dani T, Just U, Nahavandi H, Klepetko W, Knobler R (2012) A prospective interventional study on the use of extracorporeal photopheresis in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant 31:950–957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang DI, Lee AH, Shin HY, Song HR, Park JH, Kang TB, Lee SR, Yang SH (2021) The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci 22:2719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- January SE, Fester KA, Bain KB, Kulkarni HS, Witt CA, Byers DE, Alexander-Brett J, Trulock EP, Hachem RR (2019) Rabbit antithymocyte globulin for the treatment of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Clin Transplant 33:e13708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]