Abstract

Trybizine hydrochloride [O,O′-bis(4,6-diamino-1,2-dihydro-2,2-tetramethylene-s-triazine-1-yl)-1,6-hexanediol dihydrochloride] was active in vitro against the sleeping sickness-causing agents Trypanosoma brucei subsp. rhodesiense and T. brucei subsp. gambiense; against a multidrug-resistant organism, T. brucei subsp. brucei; and against animal-pathogenic organisms Trypanosoma evansi, Trypanosoma equiperdum, and Trypanosoma congolense; but not against the intracellular parasites Trypanosoma cruzi and Leishmania donovani. Cytotoxic effects against mammalian cells were observed at approximately 106-fold higher concentrations than those necessary to inhibit T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense. Trybizine hydrochloride was able to eliminate T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense and T. brucei subsp. gambiense in an acute rodent model with four intraperitoneal doses of 0.25 mg kg of body weight−1 or four doses of 1 mg kg−1, respectively, or with four oral doses of 20 mg kg−1. The compound expressed activity against suramin-resistant T. evansi strains in mice. However, these concentrations were not sufficient to cure mice infected with multidrug-resistant T. brucei subsp. brucei. A late-stage rodent model with central nervous system involvement could not be cured, indicating that trybizine may not pass the blood-brain barrier in sufficient quantities.

Current methods of treatment of African sleeping sickness are unsatisfactory because the number of available drugs is limited, the period of treatment is long, and the treatment is associated with severe side effects. Melarsoprol (Arsobal; Specia, Paris, France) has adverse effects (17), while the only alternative drug for the late-stage disease, dl-α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO; Eflornithine), is only effective against gambiense sleeping sickness but not against the rhodesiense type (1, 7, 8). In addition, the occurrence of drug-resistant trypanosomes is threatening successful chemotherapy of human trypanosomosis (15a) as well as animal trypanosomoses (2). For Chagas disease and the leishmaniases, the existing drugs are also inadequate because of their variable efficacy, toxicity, and required long courses of treatment (3).

A novel antitrypanosomal agent has been introduced by the Shanghai Institute of Pharmaceutical Industry. Trybizine hydrochloride [O,O′-bis(4,6-diamino-1,2-dihydro-2,2-tetramethylene-s-triazine-1-yl)-1,6-hexanediol dihydrochloride; Chinese patent, CN 1096514A] has been shown to express activity against Trypanosoma evansi, a trypanosome species infecting various domestic animals worldwide. The aim of this study was to evaluate trybizine hydrochloride for its activity against other pathogenic hemoflagellates, particularly those which cause human sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma brucei subsp. rhodesiense and T. brucei subsp. gambiense), Chagas disease (Trypanosoma cruzi), and leishmaniasis (Leishmania donovani).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and cells.

The history of the trypanosome stocks and clones used in this study is given in Table 1. The culture-adapted populations of T. brucei subsp. brucei STIB 950 and STIB 940 show a multidrug-resistant phenotype (10, 11). All Sudanese T. evansi strains used in this study were resistant in vitro and in mice to quinapyramine and suramin (6). T. evansi STIB 780 is highly resistant to quinapyramine and suramin (22). T. evansi STIB 806 is resistant to isometamidium, and T. evansi STIB 780 is resistant to quinapyramine and suramin. Both T. congolense STIB 801 and STIB 790 are resistant to diminazene and isometamidium.

TABLE 1.

History of the trypanosome stocks used in this study

| Designation of derivative | Species | Original designation | Place of isolation | Yr of isolation | Host |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STIB 900 | T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense | STIB 704 | Tanzania | 1982 | Human |

| STIB 930 | T. brucei subsp. gambiense | TH-1/78E(031) | Ivory Coast | 1978 | Human |

| STIB 920 | T. brucei subsp. brucei | STIB 348 | Tanzania | 1971 | Hartebeest |

| STIB 950 | T. brucei subsp. brucei | CP 2469 | Somalia | 1985 | Bovine |

| STIB 940 | T. brucei subsp. brucei | CP 547 | Somalia | 1985 | Bovine |

| GVR 35 | T. brucei subsp. brucei | LUMP 22 | Tanzania | 1966 | Wildebeest |

| STIB 806 | T. evansi | China | 1983 | Buffalo | |

| EASTRY 1 | T. evansi | Sudan | 1994 | Camel | |

| EASTRY2 | T. evansi | Sudan | 1994 | Camel | |

| WESTRY3 | T. evansi | Sudan | 1996 | Camel | |

| WESTRY4 | T. evansi | Sudan | 1996 | Camel | |

| STIB 780 | T. evansi | CP 893 | Kenya | 1982 | Camel |

| STIB 818 | T. equiperdum | China | 1979 | Horse | |

| STIB 910 | T. congolense | STIB 249 | Tanzania | 1971 | Lion |

| CP 81 | T. congolense | Kenya | 1966 | Bovine | |

| STIB 801 | T. congolense | IL 2856 | Burkina Faso | 1983 | Bovine |

| STIB 790 | T. congolense | CP 2036 | Kenya | 1985 | Bovine |

L. donovani MHOM/ET/67/L82 and T. cruzi MHOM/Br/00/Y were propagated in mouse peritoneal macrophages and in the human fetal lung fibroblast cell line WI-38 (ATCC CCL 75), respectively. In addition, rat skeletal muscle myoblast (L-6) cells and human adenocarcinoma (HT-29) cells, isolated in 1964 from a primary tumor (ATCC HTB 38), were used.

Drugs.

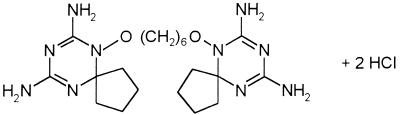

Trybizine hydrochloride (Fig. 1) was obtained from W. Zhou from the Shanghai Institute of Pharmaceutical Industry. The compound was solubilized in dest. H2O before use at 1 mg of drug/ml.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structure of trybizine hydrochloride.

Cultivation of parasites.

T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense, T. brucei subsp. gambiense, T. brucei subsp. brucei, T. evansi, and Trypanosoma equiperdum were propagated in vitro in minimum essential medium (MEM; GIBCO-BRL no. 072-1100 powder) with Earle’s salts supplemented with 1 mg of glucose ml−1, 1% MEM nonessential amino acids (100×), 2.2 mg of NaHCO3 ml−1, and 10 mM HEPES. The medium was further supplemented with 2 mM sodium pyruvate, 0.2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1 mM hypoxanthine, and 15% heat-inactivated horse serum (prepared by us from horse blood obtained from a local slaughterhouse). The medium for T. brucei subsp. gambiense cultures was supplemented with 10% human serum (STI human serum pool) and 5% fetal bovine serum (Biological Industries, Kibbutz Beth Haemek, Israel), both heat inactivated. T. congolense isolates were propagated according to the method of Kaminsky et al. (14) in Iscove’s medium (GIBCO-BRL no. 074-02200; Life Technologies, Basel, Switzerland) supplemented with 0.05 mM bathocuproinedisulfonic acid, 1.5 mM l-cysteine, 0.5 mM hypoxanthine, 2 mM l-glutamine, 0.12 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mM sodium pyruvate, and 15% heat-inactivated goat serum (C.C.PRO GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany).

All cultures were kept in 24-well plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) at 37°C (or 34°C for T. congolense) in a humidified atmosphere in 5% CO2. Cultures were subpassaged to a density of 103 to 105 trypanosomes per ml every second or third day. Trypanosomes in the logarithmic growth phase were used for determination of drug sensitivities.

The medium for cultivation of T. cruzi consisted of MEM (GIBCO-BRL no. 072-1100 powder) supplemented with 1% MEM nonessential amino acids (100×) and 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Monolayers of WI-38 or L-6 cells were subsequently infected with trypomastigote forms of T. cruzi.

All mammalian cells were propagated in MEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Stock cultures of mammalian cells were maintained in T-25 flasks (Falcon, Becton Dickinson) in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were subpassaged to the appropriate split ratio (1:4 to 1:6) once a week.

In vitro chemosensitivity assays.

Drug susceptibilities were determined in vitro as previously described (18, 19). In vitro activity of trybizine hydrochloride against T. cruzi was determined with a 5-day assay developed in our laboratory (unpublished). WI-38 cells were seeded in a density of 105 cells ml−1 in 1-ml samples into 24-well culture plates (Costar). After 48 h, the medium was removed, and the cell layer was infected with 105 trypomastigote T. cruzi organisms. The infection was allowed to develop for 48 h, after which the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the appropriate drug concentration. Propagation of amastigotes and the appearance of trypomastigotes under drug pressure were determined microscopically after an additional 72-h exposure period. The susceptibility of L. donovani to trybizine hydrochloride in vitro was tested by the procedure described by Neal and Croft (16).

In vivo drug susceptibility test.

Female Swiss ICR mice, weighing 25 to 35 g each, were used for the in vivo drug tests. Each mouse was inoculated intraperitoneally (i.p.) with 105 trypanosomes, and treatment was initiated 24 h after inoculation. Trybizine hydrochloride was administered i.p. or orally at the appropriate concentration. The tail blood of mice was examined for the presence of trypanosomes three times a week for a total of 60 days by the wet blood film technique. Mice were considered cured when no trypanosomes were detected during the observation period. A similar procedure was used to evaluate the activity of trybizine hydrochloride against T. brucei subsp. gambiense, except that Mastomys natalensis rats were used instead of white mice. M. natalensis were immunosuppressed prior to infection with 200 mg of cyclophosphamide kg of body weight−1. The tail blood of Mastomys was examined for the presence of trypanosomes by the hematocrit centrifugation technique (21).

To evaluate the activity of trybizine hydrochloride against central nervous system (CNS) infections, the rodent late-stage model according to Jennings and Gray (9) was used.

Time-versus-dose experiment.

Experiments to determine the time of exposure to a drug versus the viability (time-dose response) of T. brucei subsp. brucei STIB 920 in the presence of trybizine hydrochloride were performed as previously described (12).

RESULTS

The effects of the in vitro activity of trybizine hydrochloride on various hemoflagellates and on mammalian cells are summarized in Table 2. Trybizine eliminated all T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense and T. brucei subsp. gambiense organisms at a concentration of or below 1.3 ng ml−1. The multidrug-resistant T. brucei subsp. brucei stocks were less susceptible, and the difference in susceptibility between the susceptible and multidrug-resistant T. brucei subsp. brucei organisms was 10-fold. T. evansi and T. equiperdum were very susceptible to trybizine; the MICs (0.2 and 0.1 ng ml−1) for them were the lowest obtained for all trypanosome species. T. congolense, a cattle-pathogenic species, was 50- to 100-fold less-susceptible to trybizine. Overall, the MIC and the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) for the most and least susceptible stocks differed 280-fold.

TABLE 2.

In vitro activity of trybizine hydrochloride against various trypanosome species, L. donovani, T. cruzi, and mammalian cells

| Species | Trypanosome stock | Result (ng ml−1) for a:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trybizine hydrochloride

|

Diminazene aceturate

|

||||

| MIC | IC50 | MIC | IC50 | ||

| T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense | STIB 900 | 0.4 ± 0 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | 22.6 ± 10.3 | 5.22 ± 0.60 |

| T. brucei subsp. gambiense | STIB 930 | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 0.20 ± 0.51 | 48.4 ± 45.8 | NDb |

| T. brucei subsp. brucei mdr | STIB 940 | 28.0 ± 10.5 | 5.84 ± 2.09 | 193.0 ± 121.2 | 56.0 ± 9.80 |

| T. brucei subsp. brucei mdr | STIB 950 | 28.5 ± 10.4 | 7.20 ± 7.76 | 185.0 ± 128.1 | 28.0 ± 2.98 |

| T. brucei subsp. brucei | STIB 920 | 2.6 ± 1.2 | 0.84 ± 0.53 | 30.8 ± 7.7 | 5.39 ± 0.99 |

| T. evansi | STIB 806 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.06 ± 0.04 | ND | ND |

| T. equiperdum | STIB 818 | 0.1 ± 0 | 0.04 ± 0.02 | ND | ND |

| T. congolense | STIB 910 | 11.1 ± 0 | 2.21 ± 0.43 | 111 ± 0 | 63.2 ± 9.03 |

| T. congolense | CP 81 | 11.1 ± 0 | 2.19 ± 0.09 | 111 ± 0 | 64.5 ± 9.70 |

| L. donovani | MHOM/ET/67/L82 | >9 × 104 | NAc | NA | NA |

| T. cruzi | MHOM/Br/00/Y | >1 × 105 | NA | NA | NA |

| Mouse L-6 cells | 1 × 106 | NA | NA | NA | |

| Human HT-29 cells | >1 × 106 | NA | NA | NA | |

MICs and IC50s are given as means ± standard deviations of at least three to five experiments, each performed in duplicate. For details, see Materials and Methods.

ND, not done.

NA, not applicable.

No activity was observed against the intracellular T. cruzi and L. donovani at the highest concentrations tested. Mouse L-6 cells were only affected at a concentration of 1 mg ml−1. This concentration did not affect human HT-29 epithelial cells.

Investigations of the time-dose response of trybizine in T. brucei subsp. brucei STIB 920 revealed that an exposure of 10 μg ml−1 over 16 h was necessary to eliminate all trypanosomes. When the exposure time was extended to 48 h, a concentration of 10 ng ml−1 was sufficient; the same effect was achieved with 1 and 0.1 μg ml−1 over 48 h. It was not possible to inhibit T. brucei subsp. brucei irreversibly with a concentration of or below 1 ng ml−1 (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Time-dose response of T. brucei subsp. brucei STIB 920 to trybizine hydrochloride in vitroa

| Trybizine hydrochloride concn (μg ml−1) | Result with drug exposure time (h)b:

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 1 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 16 | 24 | 48 | 72 | 96 | 144 | |

| 100 | − | − | − | − | |||||||

| 10 | + | + | + | +/− | − | − | |||||

| 1 | + | + | + | + | + | +/− | − | ||||

| 0.1 | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | ||||

| 0.01 | + | +/− | − | − | − | − | |||||

| 0.001 | + | + | + | + | + | ||||||

| 0.0001 | + | + | + | ||||||||

Trypanosome cultures were observed daily for 10 days following the indicated drug exposure time.

+, trypanosomes were not affected by the drug; +/−, drug-induced growth inhibition of trypanosomes (In some cases, cultures recovered to normal growth.); −, drug-induced elimination of trypanosomes.

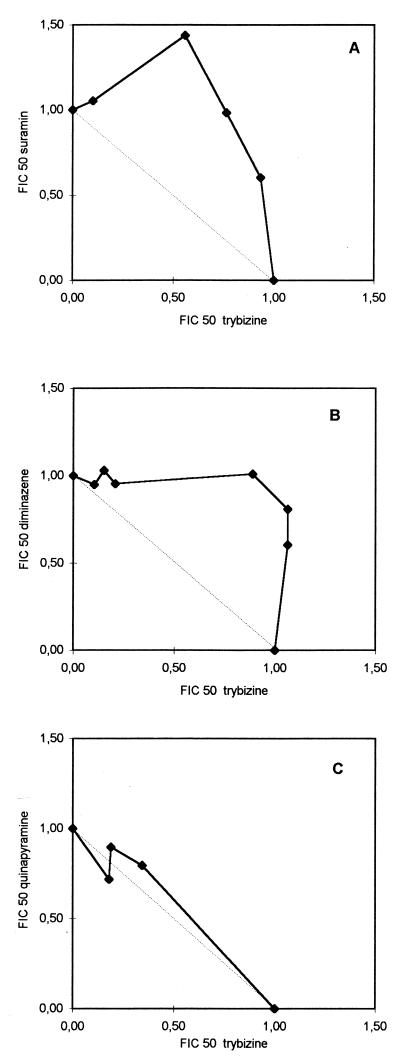

Trybizine and suramin had an antagonistic effect on T. brucei subsp. brucei STIB 920, as demonstrated by the isobologram of fractional IC50s (Fig. 2A). The same antagonistic effect was observed when trybizine was used in combination with diminazene aceturate (Fig. 2B). An additive effect was observed for the combination of trybizine with quinapyramine (Fig. 2C).

FIG. 2.

Isobolograms of trybizine and the current trypanocides suramin, diminazene, and quinapyramine. Control IC50, normalized to 1 U of the IC50, refers to trybizine alone (X-axis [FIC 50, fractional IC50]) and to suramin (A), diminazene (B), and quinapyramine (C). The solid line represents the isobole of the drug combination in vitro. The dotted line joining the FICs of 1 is the isobole of an additive combination (C). A convex isobole represents an antagonistic combination (A and B).

The results for the activity of trybizine hydrochloride in infected rodents are summarized in Table 4. It was possible to cure mice infected with human-pathogenic T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense when trybizine hydrochloride was applied i.p. at four doses of 0.25 mg kg−1. T. brucei subsp. gambiense-infected rodents were cured with four doses of 1 mg kg−1. Importantly, cure was achieved when trybizine was applied orally with four doses of 20 mg kg−1. However, it was not possible to cure mice infected with multidrug-resistant T. brucei subsp. brucei. Neither was it possible to cure the late-stage CNS model of mice infected with T. brucei subsp. brucei GVR 35. The result was the same even after combination treatment of trybizine hydrochloride with DFMO or suramin.

TABLE 4.

Antitrypanosomal activity of trybizine hydrochloride against various trypanosome species in rodent models

| Species | Stock | Drug susceptibility | Disease model | Dose in mg kg−1 (no. of doses) | Route | No. of rodents cured/no. treated |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T. brucei subsp. rhodesiense | STIB 900 | Susceptible | Acute | 0.1 (4) | i.p. | 2/4 |

| 0.25 (4) | i.p. | 4/4 | ||||

| 1 (1) | i.p. | 3/4 | ||||

| 5 (4) | Oral | 0/4 | ||||

| 20 (4) | Oral | 4/4 | ||||

| T. brucei subsp. gambiense | STIB 930 | Susceptible | Acute | 0.5 (5) | i.p. | 3/4 |

| 1 (4) | i.p. | 4/4 | ||||

| T. brucei subsp. brucei | STIB 950 | Multidrug resistant (including diminazene) | Acute | 0.25 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 |

| 1 (4) | i.p. | 0/3 | ||||

| 2.5 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 | ||||

| 5 (4) | i.p. | 2/4a | ||||

| GVR 35 | Susceptible | Late stage | 5 (10) | i.p. | 0/4 | |

| 2.5 (7) | i.p. | 0/2 | ||||

| 4 (14) (DFMO)b | Oral | |||||

| 2.5 (5) | i.p. | 0/2 | ||||

| 10 (5) (suramin)b | i.p. | |||||

| T. evansi | Eastry 1 | Resistant to suramin and quinapyramine | Acute | 1 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 |

| Eastry 2 | Resistant to suramin and quinapyramine | Acute | 1 (4) | i.p. | 7/8 | |

| Westry 3 | Resistant to suramin and quinapyramine | Acute | 1 (4) | i.p. | 4/4 | |

| Westry 4 | Resistant to suramin and quinapyramine | Acute | 2.5 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 | |

| STIB 806 | Resistant to isometamidium | Acute | 1 (4) | i.p. | 4/4 | |

| STIB 780 | Resistant to suramin and quinapyramine | Acute | 2.5 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 | |

| T. congolense | STIB 801 | Resistant to diminazene and isometamidium | Acute | 1 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 |

| CP 81 | Susceptible | Acute | 2.5 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 | |

| STIB 790 | Resistant to diminazene and isometamidium | Acute | 1 (4) | i.p. | 4/4 | |

| STIB 910 | Susceptible | Acute | 2.5 (4) | i.p. | 0/4 |

Two mice died during treatment because of toxicity.

Trybizine hydrochloride-DFMO or -suramin combination.

Some of the equine-pathogenic T. evansi strains including isolates resistant to quinapyramine and suramin were eliminated with four doses of 1 mg kg−1. However, three T. evansi strains could not be cured in mice at all. Only one of three tested cattle-pathogenic T. congolense strains was eliminated with four doses of 1 mg kg−1. For the others, four doses of 2.5 mg kg−1 were not sufficient to achieve a cure in mice.

DISCUSSION

The results obtained clearly demonstrate that trybizine hydrochloride is a powerful antitrypanosomal compound with a specific activity in vitro comparable to melarsoprol (14). Importantly, the cytotoxicity for mammalian cells was very low if at all detectable, which made trybizine a candidate for in vivo evaluation (14).

In mice, trybizine hydrochloride was able to eliminate both human-pathogenic trypanosome subspecies after either i.p. or oral administration. The latter is particularly important, because all currently available trypanocides against human trypanosomiasis have to be applied parenterally or intravenously (15), with the exception of DFMO, which can also be given orally (5). Furthermore, most of the mice infected with quinapyramine- and suramin-resistant T. evansi strains were cured. Thus, our in vitro and in vivo results confirm the activity of trybizine hydrochloride observed against Chinese T. evansi in buffaloes and bovines (21a). Trybizine has great potential against T. evansi, because quinapyramine and suramin resistance appears to be a serious problem in the chemotherapy of surra (6, 22) and, therefore, may become an alternative drug to Cymelarsan. The first trials with the arsenical agent Cymelarsan against T. evansi were carried out by Tager-Kagan et al. (20). However, it has been shown that there is some cross-resistance of Cymelarsan to other trypanocides (22).

The compound showed reduced activity for multidrug-resistant T. brucei subsp. brucei and for T. congolense. This reduced in vitro sensitivity is reflected by the in vivo results. The multidrug-resistant strain T. brucei subsp. brucei STIB 950 could not be cured and neither could three of the four T. congolense strains tested. The mechanisms for the resistance of the T. brucei subsp. brucei strains are not known, since the mode of action of trybizine is not known yet. The nonresponsiveness of both multidrug-resistant T. brucei subsp. brucei and T. congolense is a serious drawback for the potential development of trybizine for treatment of tsetse fly-transmitted trypanosomoses in sub-Saharan Africa, because drug resistance is a major problem in chemotherapy of livestock trypanosomosis, and T. congolense is a major cattle-pathogenic species (2). Experiments with domestic animals are needed to confirm the nonresponsiveness of T. congolense.

A crucial issue for assessment of the potential of any new compound against human trypanosomosis is the ability of such a compound to cross the blood-brain barrier, because in the progress of the disease, trypanosomes invade the CNS. So far, of all current trypanocides, only melarsoprol and DFMO are able to cross the blood-brain barrier in sufficient quantities (4). Trybizine hydrochloride was not able to cure the late-stage CNS model (Table 4) in mice, which would indicate that trybizine is unable to build up therapeutic levels in the CNS. Unambiguous evidence may be given by exploratory pharmacokinetic experiments with monkeys, which are in progress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Yvonne Grether, Cecile Schmid, and Babett Schwöbel for excellent technical support. This investigation received financial support from the UNDP/World Bank/WHO Special Programme for Research and Training in Tropical Diseases (TDR).

REFERENCES

- 1.Bacchi C J, Nathan H C, Livingston T, Valladares G, Saric M, Sayer P D, Njogu A R, Clarkson A B., Jr Differential susceptibility to dl-α-difluoromethylornithine in clinical isolates of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:1183–1188. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.6.1183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Codja V, Mulatu W, Majiwa P A O. Epidemiology of bovine trypanosomiasis in the Ghibe valley, southwest Ethiopia. Occurrence of populations of Trypanosoma congolense resistant to diminazene, isometamidium and homidium. Acta Trop. 1993;53:151–163. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Croft S L. The current status of antiparasitic chemotherapy. Parasitology. 1997;114:S3–S15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croft S L, Urbina J A, Brun R. Chemotherapy of human leishmaniasis and trypanosomiasis. In: Hide G, Mottram J C, Coombs G H, Holmes P H, editors. Trypanosomiasis and leishmaniasis. Tucson, Ariz: CAB International; 1997. pp. 245–247. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doua F, Yapo F B. Human trypanosomiasis in the Ivory Coast: therapy and problems. Acta Trop. 1993;54:163–168. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.El Rayah, I. E., R. Kaminsky, C. Schmid, and K. H. El Malik. Drug resistance in Sudanese Trypanosoma evansi. Vet. Parasitol., in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Iten M, Matovu E, Brun R, Kaminsky R. Innate lack of susceptibility of Ugandan Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense to DL-α-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO) Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;46:190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iten M, Mett H, Evans A, Enyaru J C K, Brun R, Kaminsky R. Alterations in ornithine decarboxylase characteristics account for tolerance of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense to dl-α-difluoromethylornithine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:1922–1925. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.9.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jennings F W, Gray A R. Relapsed parasitemia following chemotherapy of chronic Trypanosoma brucei infections in mice and its relationship to cerebral trypanosomes. Contrib Microbiol Immunol. 1983;7:147–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaminsky R, Chuma F, Zweygarth E. Trypanosoma brucei brucei: expression of drug resistance in vitro. Exp Parasitol. 1989;69:281–289. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(89)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaminsky R, Zweygarth E. Feeder layer-free in vitro assay for screening antitrypanosomal compounds against Trypanosoma brucei brucei and T. b. evansi. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:881–885. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.6.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaminsky R, Mamman M, Chuma F, Zweygarth E. Time-dose-response of Trypanosoma brucei brucei to diminazene aceturate (Berenil) and in vitro simulation of drug-concentration-time profiles in cattle plasma. Acta Trop. 1993;54:19–30. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90065-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kaminsky R, Chuma F, Wasiki R P N. Time-dose response of Trypanosoma congolense bloodstream forms to diminazene and isometamidium. Vet Parasitol. 1994;52:235–242. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaminsky R, Schmid C, Brun R. An “in vitro selectivity index” for evaluation of cytotoxicity of antitrypanosomal compounds. In Vitro Toxicol. 1996;9:315–324. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuzoe F A S. Current situation of African trypanosomiasis. Acta Trop. 1993;54:153–162. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(93)90089-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15a.Maiso, F. Personal communication.

- 16.Neal R A, Croft S L. An in vitro system for determining the activity of compounds against the intracellular amastigote form of Leishmania donovani. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1984;14:463–475. doi: 10.1093/jac/14.5.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pepin J, Milord F, Guern C, Mpia B, Ethier L, Mansinsa D. Trial of prednisolone for prevention of melarsoprol induced encephalopathy in gambiense sleeping sickness. Lancet. 1989;1:1246–1250. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Obexer W, Schmid C, Brun R. A novel in vitro screening assay for trypanocidal activity using the fluorescent dye BCECF-AM. Trop Med Parasitol. 1995;46:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Räz B, Iten M, Grether-Bühler Y, Kaminsky R, Brun R. The Alamar Blue assay to determine drug sensitivity of African trypanosomes (T. b. rhodesiense and T. b. gambiense) in vitro. Acta Trop. 1997;68:139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(97)00079-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tager-Kagan P, Itard J, Clair M. Essai de l’efficacité du CymelarsanND sur Trypanosoma evansi chez le dromédaire. Rev Elev Méd Vét Pays Trop. 1989;42:55–61. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woo P T K. The haematocrit centrifuge technique for the diagnosis of African trypanosomiasis. Acta Trop. 1970;27:384–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21a.Zhou W C, Xin Z H, Zhang X P, Shen J, Qiu Q P. Synthesis and antiprotozoal activities of some new triazine derivatives including a new antitrypanosomal agent, SIPI-1029. Acta Pharm Sin. 1996;31:823–830. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zweygarth E, Kaminsky R. Evaluation of an arsenical compound (RM 110, mel Cy, Cymelarsan®) against susceptible and drug-resistant Trypanosoma brucei brucei and T. b. evansi. Trop Med Parasitol. 1990;41:208–212. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]