Abstract

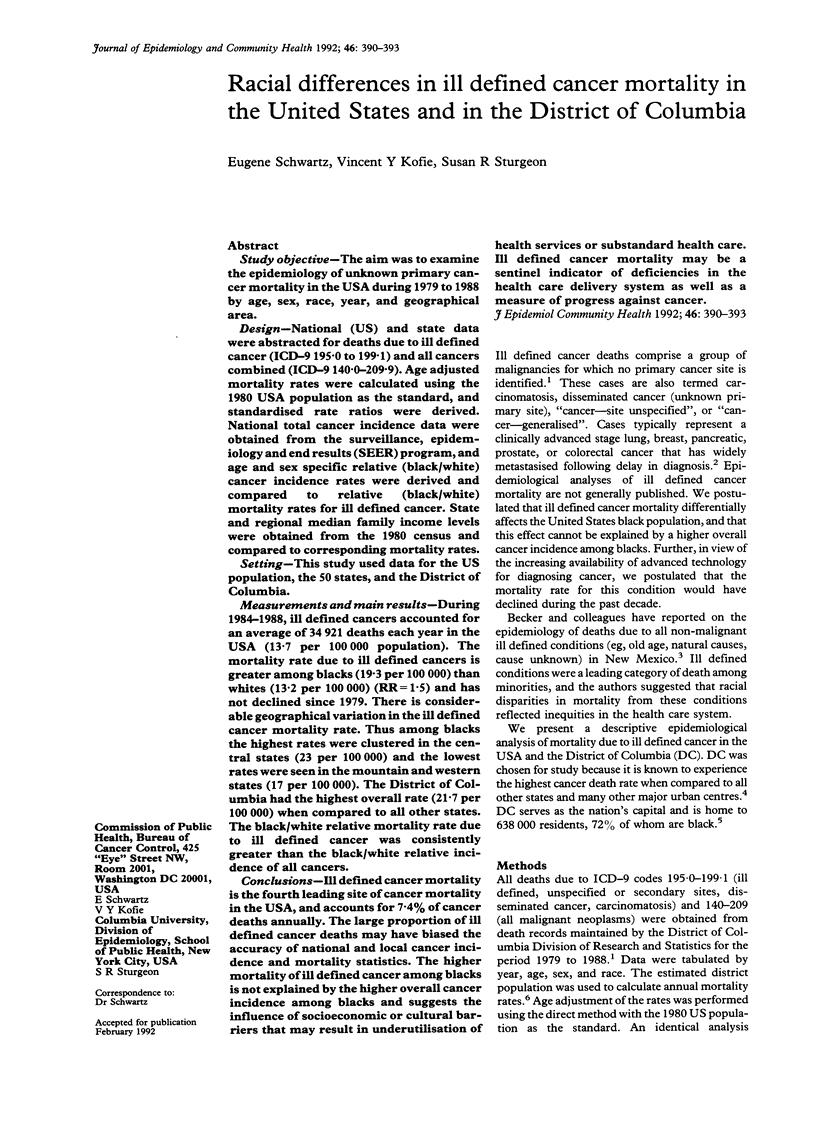

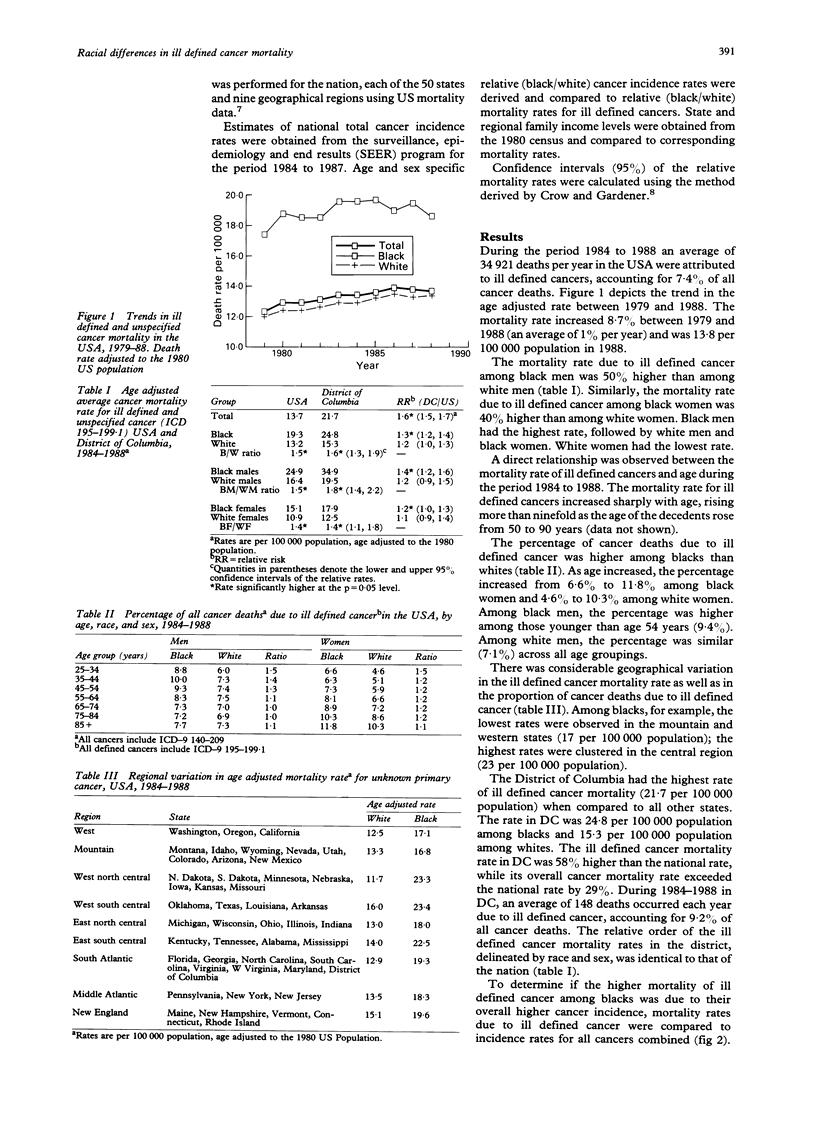

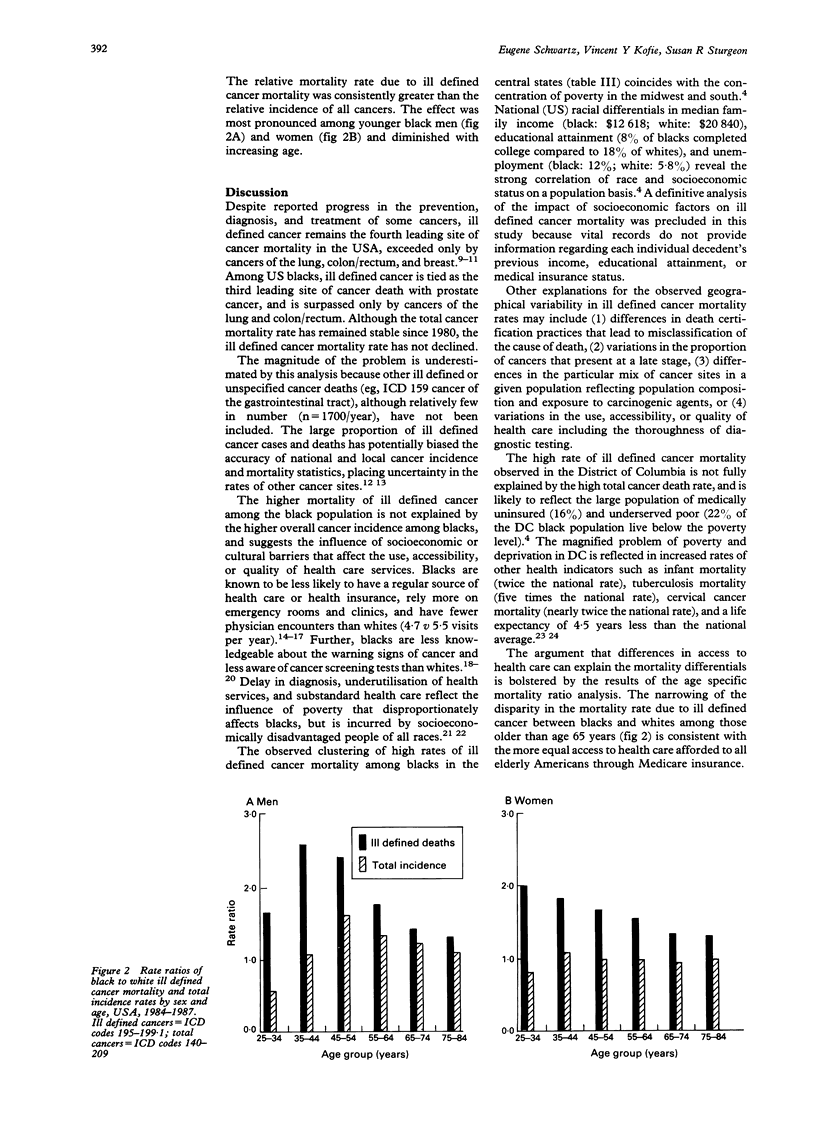

STUDY OBJECTIVE--The aim was to examine the epidemiology of unknown primary cancer mortality in the USA during 1979 to 1988 by age, sex, race, year, and geographical area. DESIGN--National (US) and state data were abstracted for deaths due to ill defined cancer (ICD-9 195.0 to 199.1) and all cancers combined (ICD-9 140.0-209.9). Age adjusted mortality rates were calculated using the 1980 USA population as the standard, and standardised rate ratios were derived. National total cancer incidence data were obtained from the surveillance, epidemiology and end results (SEER) program, and age and sex specific relative (black/white) cancer incidence rates were derived and compared to relative (black/white) mortality rates for ill defined cancer. State and regional median family income levels were obtained from the 1980 census and compared to corresponding mortality rates. SETTING--This study used data for the US population, the 50 states, and the District of Columbia. MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS--During 1984-1988, ill defined cancers accounted for an average of 34,921 deaths each year in the USA (13.7 per 100,000 population). The mortality rate due to ill defined cancers is greater among blacks (19.3 per 100,000) than whites (13.2 per 100,000) (RR = 1.5) and has not declined since 1979. There is considerable geographical variation in the ill defined cancer mortality rate. Thus among blacks the highest rates were clustered in the central states (23 per 100,000) and the lowest rates were seen in the mountain and western states (17 per 100,000). The District of Columbia had the highest overall rate (21.7 per 100,000) when compared to all other states. The black/white relative mortality rate due to ill defined cancer was consistently greater than the black/white relative incidence of all cancers. CONCLUSIONS--Ill defined cancer mortality is the fourth leading site of cancer mortality in the USA, and accounts for 7.4% of cancer deaths annually. The large proportion of ill defined cancer deaths may have biased the accuracy of national and local cancer incidence and mortality statistics. The higher mortality of ill defined cancer among blacks is not explained by the higher overall cancer incidence among blacks and suggests the influence of socioeconomic or cultural barriers that may result in underutilisation of health services or substandard health care. Ill defined cancer mortality may be a sentinel indicator of deficiencies in the health care delivery system as well as a measure of progress against cancer.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bailar J. C., 3rd, Smith E. M. Progress against cancer? N Engl J Med. 1986 May 8;314(19):1226–1232. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198605083141905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker T. M., Wiggins C. L., Key C. R., Samet J. M. Symptoms, signs, and ill-defined conditions: a leading cause of death among minorities. Am J Epidemiol. 1990 Apr;131(4):664–668. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergner L., Yerby A. S. Low income and barriers to use of health services. N Engl J Med. 1968 Mar 7;278(10):541–546. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196803072781006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn A. M. On the distribution of underlying causes of death. Am J Public Health. 1982 Feb;72(2):133–140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.2.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krementz E. T., Cerise E. J., Foster D. S., Morgan L. R., Jr Metastases of undetermined source. Curr Probl Cancer. 1979 Nov;4(5):4–37. doi: 10.1016/s0147-0272(79)80019-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors H. W. Ambulatory medical care among adult black Americans: the hospital emergency room. J Natl Med Assoc. 1986 Apr;78(4):275–282. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percy C., Stanek E., 3rd, Gloeckler L. Accuracy of cancer death certificates and its effect on cancer mortality statistics. Am J Public Health. 1981 Mar;71(3):242–250. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.3.242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein D. D., Berenberg W., Chalmers T. C., Child C. G., 3rd, Fishman A. P., Perrin E. B. Measuring the quality of medical care. A clinical method. N Engl J Med. 1976 Mar 11;294(11):582–588. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197603112941104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E., Kofie V. Y., Rivo M., Tuckson R. V. Black/white comparisons of deaths preventable by medical intervention: United States and the District of Columbia 1980-1986. Int J Epidemiol. 1990 Sep;19(3):591–598. doi: 10.1093/ije/19.3.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]