Abstract

OPC-20011, a new parenteral 2-oxaisocephem antibiotic, has an oxygen atom at the 2- position of the cephalosporin frame. OPC-20011 had the best antibacterial activities against gram-positive bacteria, including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Enterococcus faecalis, and penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae: MICs at which 90% of the isolates were inhibited were 6.25, 6.25, and 0.05 μg/ml, respectively. Its activity is due to a high affinity of the penicillin-binding protein 2′ in MRSA, an affinity which was approximately 1,050 times as high as that for flomoxef. Against gram-negative bacteria, OPC-20011 also showed antibacterial activities similar to those of ceftazidime. The in vivo activities of OPC-20011 were comparable to or greater than those of reference compounds in murine models of systemic infection caused by gram-positive and -negative pathogens. OPC-20011 was up to 10 times as effective as vancomycin against MRSA infections in mice. This better in vivo efficacy is probably due to the bactericidal activity of OPC-20011, while vancomycin showed bacteriostatic activity against MRSA. OPC-20011 produced a significant decrease of viable counts in lung tissue at a dose of 2.5 mg/kg of body weight, an efficacy similar to that of ampicillin at a dose of 10 to 20 mg/kg on an experimental murine model of respiratory tract infection caused by non-ampicillin-susceptible S. pneumoniae T-0005. The better therapeutic efficacy of OPC-20011 was considered to be due to its potent antibacterial activity and low affinity for serum proteins of experimental animals (29% in mice and 6.4% in rats).

β-Lactam antibiotics are known to have strong, broad-spectrum antibacterial activity against both gram-positive and -negative bacteria and to be safe in clinical use. There is, however, a worldwide increase in bacteria highly resistant to β-lactams (4, 8, 22, 23). Approximately 50 to 80% of Staphylococcus aureus strains have become resistant to many kinds of antibiotics, with a few exceptions, such as vancomycin (VCM). Furthermore, resistance to penicillin among strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae has been spreading worldwide (9, 14, 15). In some regions, such as Spain, almost 50% of S. pneumoniae clinical isolates are penicillin resistant. These facts suggest that there may be few antibiotics which can be utilized against infections caused by these gram-positive pathogens in the future. Furthermore, the introduction of new antibiotics has been decreasing recently compared with the period from 1945 to 1970, when a variety of new antibiotics with new structures were discovered (3). The time has come to attempt to develop new agents which can solve the problem of resistant bacteria. Our efforts have been focused on the development of new antibiotics to solve these problems. In earlier work (6, 7), 2-oxaisocephem antibiotics were synthesized and evaluated as a new class of antibiotics by Doyle et al. They reported that 2-oxaisocephem lacked comprehensive antibacterial activity (7). In the course of our research, we identified OPC-20011 from a novel series of 2-oxaisocephems that showed good antibacterial activity against methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), Enterococcus faecalis, and penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae and had a broad spectrum of antibacterial activity (13, 24). In this study we evaluated the antibacterial activities in vitro and in vivo of OPC-20011 and compared them with those of reference compounds. We also compared OPC-20011 with a 1-sulfur analog with the same substituents as OPC-20011 to clarify the properties of 2-oxaisocephem antibiotics.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Organisms.

The clinical isolates used in this study were obtained from several hospitals in Japan from 1990 to 1995 and were stocked in our laboratory. The other strains used in this study were stock cultures from our laboratory.

Antimicrobial agents.

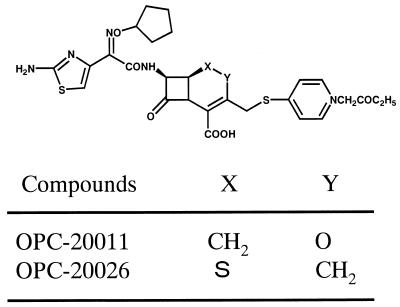

OPC-20011 and OPC-20026, a 1-sulfur analog with the same substituents as OPC-20011 (Fig. 1), were synthesized at the Microbiological Research Institute of Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokushima, Japan. The other antibiotics, including cefotiam (CTM), flomoxef (FMOX), ceftazidime (CAZ), cefpirome (CPR), ampicillin (ABPC), imipenem (IPM), methicillin (DMPPC), and VCM, were purchased from commercial sources.

FIG. 1.

Chemical structures of OPC-20011 and OPC-20026.

Susceptibility testing.

MICs were determined by the twofold agar dilution method with Mueller-Hinton agar (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), which was supplemented with 5% horse blood to support the growth of S. pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Haemophilus influenzae. The overnight cultures were diluted to approximately 106 CFU/ml with fresh broth, and an inoculum of 104 CFU per spot was applied with an inoculating apparatus (Microplanter; Sakuma Seisakusho, Tokyo, Japan) to agar plates containing graded concentrations of each compound. The MICs were defined as the minimum drug concentrations which completely inhibited the growth of bacteria after incubation at 37°C for 18 h.

Affinities of PBPs.

The affinities of penicillin-binding proteins (PBPs) for OPC-20011 and the reference compounds were determined by competition assay with [14C]benzylpenicillin (Amersham Japan Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) as described previously (20, 21). Membranes were collected by differential centrifugations (5,000 × g for 15 min and 100,000 × g for 60 min) of enzymatically (100 μg of lysostaphin/ml containing 10 μg of DNase/ml) disrupted cells of S. aureus FDA 209-P and MRSA 5143 or sonically disrupted cells of S. pneumoniae T0096 and Escherichia coli NIHJ JC-2 in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The concentrations of membrane proteins, based on γ-globulin levels, were adjusted to 8 mg/ml for S. aureus FDA 209-P, MRSA 5143, and S. pneumoniae T0096 and to 20 mg/ml for E. coli NIHJ JC-2. The binding reactions were done for 10 min with test compounds at each concentration followed by 15 min with [14C]benzylpenicillin at 37°C. The binding affinities of PBPs for the test compounds were expressed as the concentration required to prevent 50% of the binding of [14C]benzylpenicillin (50% inhibitory concentration [IC50]) to each PBP, determined by the imaging analyzer BAS 2000 (Fuji Chemical Co. Ltd.).

In vivo effects. (i) Systemic infections.

In vivo activities against systemic infections caused by gram-positive and -negative pathogens were determined. Ten male ICR mice weighing 20 ± 1 g were used for each dosage group. The mice were challenged intraperitoneally with 0.5 ml of approximately 10 to 100 times the 50% lethal doses of the respective pathogens. The bacterial suspensions, which were prepared from overnight cultures on Tryptic soy broth (Difco) for methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) and MRSA, on brain heart infusion broth (Nissui) for S. pneumoniae, and on Mueller-Hinton broth for other pathogens at 37°C, were suspended in the fresh broth of overnight cultures containing gastric mucin (Difco) (for the concentrations, see Table 6). One hour after infection, various doses of each compound were administered to the mice subcutaneously. The number of mice surviving after each dose was determined on day 7 after infection, and the 50% effective dose (ED50) was calculated by the probit method.

TABLE 6.

Protective effects of OPC-20011 and reference compounds against experimental systemic infection models in mice

| Organism (% of mucin used) | Compound | MIC (μg/ml) | Challenge dose (cells/ mouse) | ED50 (mg/kg) | Confidence limit (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S. aureus Smith | OPC-20011 | 0.2 | 1.32 × 107 | 0.22 | 0.11–0.37 |

| (5) | CTM | 0.39 | 0.61 | 0.006–1.56 | |

| CAZ | 12.5 | 12.12 | 6.54–19.66 | ||

| FMOX | 0.39 | 0.53 | 0.17–0.87 | ||

| CPR | 0.39 | 1.72 | 1.29–2.40 | ||

| VCM | 0.78 | 3.74 | 2.58–5.12 | ||

| MRSA 5120 | OPC-20011 | 6.25 | 7.6 × 107 | 1.00 | 0.60–1.57 |

| (5) | CTM | 100 | >100 | ||

| CAZ | 100 | >100 | |||

| FMOX | 25 | 8.52 | 4.41–17.3 | ||

| CPR | 50 | 27.7 | 12.92–105 | ||

| VCM | 0.78 | 11.5 | 7.12–17.2 | ||

| MRSA 5143 | OPC-20011 | 6.25 | 1.31 × 107 | 6.63 | 4.48–10.8 |

| (5) | CTM | >100 | >200 | ||

| CAZ | >100 | >200 | |||

| FMOX | 50 | 74.5 | 37.9–230 | ||

| CPR | 100 | >200 | |||

| VCM | 0.78 | 4.66 | 3.30–6.36 | ||

| E. faecalis C0063 (2.5) | OPC-20011 | 0.78 | 7.0 × 107 | 5.23 | 3.88–7.31 |

| CTM | 100 | >200 | |||

| CAZ | >100 | >200 | |||

| FMOX | 100 | >200 | |||

| CPR | 12.5 | >100 | |||

| ABPC | 1.56 | 5.2 | 3.86–7.00 | ||

| S. pneumoniae Type III | OPC-20011 | <0.0015 | 4.2 × 102 | 5.54 | 3.56–11.9 |

| CTM | 0.1 | 27 | 17.94–56.3 | ||

| (none) | CAZ | 0.2 | 172 | 122–341 | |

| FMOX | 0.2 | 11.2 | 5.26–41.4 | ||

| CPR | 0.013 | 26.72 | 19.5–42.1 | ||

| ABPC | 0.025 | 13.2 | 8.36–25.3 | ||

| S. pneumoniae C0096 | OPC-20011 | 0.006 | 2.0 × 104 | 0.56 | 0.31–0.90 |

| CTM | 6.25 | 29.5 | 17.4–49.5 | ||

| (none) | CAZ | 3.13 | 18.1 | 11.8–33.5 | |

| FMOX | 6.25 | 18.6 | 10.1–63.7 | ||

| CPR | 0.2 | 1.68 | 1.08–2.55 | ||

| ABPC | 3.13 | 8.23 | 5.47–12.8 | ||

| E. coli 29 (2.5) | OPC-20011 | 0.39 | 1.35 × 106 | 0.15 | 0.12–0.19 |

| CTM | 0.10 | 1.10 | 0.78–1.53 | ||

| CAZ | 0.39 | 0.17 | 0.12–0.22 | ||

| FMOX | 0.10 | 0.43 | 0.31–0.57 | ||

| CPR | 0.025 | 0.64 | 0.46–0.86 | ||

| E. coli T0020 | OPC-20011 | 0.013 | 6.8 × 105 | 0.06 | 0.039–0.090 |

| (2.5) | CTM | 0.05 | 0.052 | 0.036–0.072 | |

| CAZ | 0.05 | 0.21 | 0.126–0.298 | ||

| FMOX | 0.025 | 0.59 | 0.435–0.775 | ||

| CPR | 0.013 | 0.65 | 0.486–0.871 | ||

| K. pneumoniae T0011 (2.5) | OPC-20011 | 0.2 | 5.3 × 102 | 8.42 | 5.93–12.4 |

| CTM | 0.1 | 10.7 | 8.14–14.3 | ||

| CAZ | 0.05 | 0.87 | 0.24–1.45 | ||

| FMOX | 0.1 | 12.7 | 9.80–16.4 | ||

| CPR | 0.013 | 0.67 | 0.45–0.91 | ||

| S. marcescens T0004 (2.5) | OPC-20011 | 0.78 | 1.6 × 106 | 1.41 | 0.622–2.30 |

| CTM | 3.13 | 26.7 | 8.34–56.2 | ||

| CAZ | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.065–0.300 | ||

| FMOX | 0.78 | 2.34 | 1.20–3.79 | ||

| CPR | 0.1 | 0.11 | 0.0063–0.209 | ||

| P. mirabilis T0003 (2.5) | OPC-20011 | 0.2 | 2.5 × 106 | 3.38 | 1.51–6.59 |

| CTM | 0.39 | 10.6 | 5.73–26.6 | ||

| CAZ | 0.05 | 1.42 | 8.92–59.3 | ||

| FMOX | 0.39 | 22.6 | 0.686–2.53 | ||

| P. aeruginosa T0017 (2.5) | OPC-20011 | 6.25 | 4.8 × 104 | 130 | 95.7–171 |

| CTM | >100 | >200 | |||

| CAZ | 0.78 | 11.3 | 5.44–22.9 | ||

| FMOX | >100 | >200 | |||

| AZT | 3.13 | 78.6 | 50.3–133 |

(ii) Respiratory tract infection.

Groups of five rats (SD rats; age, 5 weeks), pretreated 3 days before infection with cyclophosphamide, were anesthetized with diethyl ether and challenged directly in the respiratory tract by instilling 0.2 ml of a suspension of MRSA 5143. The challenge doses were 2.75 × 107 CFU/ml. Antibiotics were administered subcutaneously at doses of 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg of body weight for OPC-20011 or 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg for VCM three times, at 24, 36, and 48 h following infection. The lungs were then removed aseptically under diethyl ether anesthesia 24 h after the final treatment and homogenized in 2 ml of distilled water, and the viable bacilli in the lungs of each rat were counted on Mueller-Hinton agar plates.

Groups of five mice (ICR mice; age, 4 weeks) were anesthetized with diethyl ether and challenged directly in the respiratory tract by instilling 0.1 ml of suspension of S. pneumoniae T0005, which is a pathogen insensitive to ABPC. The challenge doses were 2.75 × 104 CFU/ml. Antibiotics were administered subcutaneously at doses of 2.5, 5, and 10 mg/kg once at 24 h for OPC-20011 or at doses of 5, 10, and 20 mg/kg three times, at 24, 40, and 48 h after infection, for ABPC and VCM. The lungs were then removed aseptically under diethyl ether anesthesia 24 h after the final treatment and homogenized in 2 ml of distilled water, and the viable bacilli in the lungs of each mouse were counted on Mueller-Hinton agar plates which were supplemented with 5% horse blood. Statistical analysis was done by the following procedures. The viable count of bacilli in the lungs of each animal was expressed as log10 CFU, and the differences among the groups was determined by using a two-tailed Dunnett’s test.

Time-kill curve.

The activities of OPC-20011 and VCM against MRSA were determined by a time-kill study, as described previously (27). An overnight culture of MRSA was diluted with fresh Mueller-Hinton broth to a density of approximately 104 CFU/ml, and the dilution was preincubated in L-tubes at 37°C for 1 h with shaking. Various concentrations, close to the MICs, of the test compounds were added to the culture. At fixed time intervals, 0.1-ml portions of the contents of each tube were removed to 0.9 ml of fresh saline and spread on drug-free Mueller-Hinton agar plates after being suitably diluted (101 to 107 times). The colonies were counted after incubation for 18 h at 37°C.

Affinity for serum proteins of different animal species.

The binding percentages of OPC-20011 to serum proteins of different animal species were determined by the following procedure. Sera were obtained from different species (ICR mice, SD rats, NEZ rabbits, beagle dogs, cynomolgus monkeys, and healthy human donors). Each serum was mixed with 1/10 volume of 500 μg of OPC-20011/ml and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. The incubated samples were then ultrafiltered with Centrisart Cutoff 20000 (Sartorius). The binding concentrations of the compound in the filtrates were measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (SPD-10A chromatograph [Shimadzu Co. Ltd.]; UV wavelength, 300 nm; solvent, 25% solution of CH3CN containing 0.05% trifluoroacetate).

RESULTS

Susceptibility of clinical isolates.

The activity of OPC-20011 against clinical isolates was compared with that of OPC-20026, CTM, CAZ, FMOX, CPR, ABPC, IPM, DMPPC, and VCM. The MICs at which 90% of the isolates are inhibited (MIC90s) of test compounds for the strains tested are shown in Tables 1 and 2. In the first study, the MIC90s of OPC-20011 were 2 to 16 times lower than those of OPC-20026. In particular, a 16-fold difference was observed between the MIC90 of OPC-20011 and that of OPC-20026 for E. faecalis (Table 1). The MIC90s of OPC-20011 for MSSA, DMPPC-susceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis, and non-ABPC-susceptible S. pneumoniae were 0.78, 1.56, and 0.05 μg/ml, respectively, the lowest MICs among the test compounds. For MRSA, the MIC90 of OPC-20011 was 6.25 μg/ml, which was lower than those of other β-lactam antibiotics tested but 2 dilutions higher than that of VCM. The MIC90s of OPC-20011 for DMPPC-resistant S. epidermidis and E. faecalis were 3.13 and 6.25 μg/ml, respectively, which were almost equal to those for VCM and ABPC, respectively, and 2 to 32 times lower than those of the other reference antibiotics tested.

TABLE 1.

Comparison of antibacterial activities (MIC90s) of OPC-20011 and OPC-20026

| Clinical isolate | No. of strains | MIC90 (μg/ml)

|

Ratioa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPC-20011 | OPC-20026 | |||

| MSSA | 47 | 0.78 | 1.56 | 2 |

| MRSA | 33 | 6.25 | 25 | 4 |

| DMPPC-susceptible S. epidermidis | 44 | 1.56 | 3.13 | 2 |

| DMPPC-resistant S. epidermidis | 34 | 3.13 | 6.25 | 2 |

| E. faecalis | 25 | 6.25 | 100 | 16 |

| Non-ABPC-susceptible S. pneumoniae | 18 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 2 |

| E. coli | 54 | 1.56 | 6.25 | 4 |

| K. pneumoniae | 26 | 3.13 | 12.5 | 4 |

| S. marcescens | 27 | 6.25 | 12.5 | 2 |

| P. mirabilis | 41 | 1.56 | 6.25 | 4 |

| P. rettgeri | 40 | 1.56 | 6.25 | 4 |

MIC90 of OPC-20026/MIC90 of OPC-20011.

TABLE 2.

Antibacterial activities of OPC-20011 and reference compounds against clinical isolates

| Organism (no. of strains) | Compound | MIC (μg/ml)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | ||

| MSSA (47) | OPC-20011 | 0.1–3.13 | 0.39 | 0.78 |

| CTM | 0.025–12.5 | 0.78 | 3.13 | |

| FMOX | 0.39–6.25 | 0.78 | 1.56 | |

| CAZ | 3.13–50 | 12.5 | 25 | |

| CPR | 0.39–25 | 1.56 | 1.56 | |

| IPM | 0.006–1.56 | 0.006 | 0.1 | |

| DMPPC | 1.56–6.25 | 3.13 | 6.25 | |

| VCM | 0.78–1.56 | 0.78 | 1.56 | |

| MRSA (33) | OPC-20011 | 0.78–6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 |

| CTM | 100–>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| FMOX | 0.78–100 | 25 | 100 | |

| CAZ | >100–>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| CPR | 3.13–100 | 50 | 100 | |

| IPM | 0.1–>100 | 50 | 100 | |

| DMPPC | >100–>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| VCM | 0.78–1.56 | 1.56 | 1.56 | |

| DMPPC-susceptible S. epidermidis (44) | OPC-20011 | 0.2–1.56 | 0.39 | 1.56 |

| CTM | 0.39–3.13 | 0.78–3.13 | ||

| FMOX | 0.39–12.5 | 1.56 | 12.5 | |

| CAZ | 3.13–25 | 6.25 | 25 | |

| CPR | 0.39–6.25 | 0.78 | 3.13 | |

| DMPPC | 1.56–6.25 | 3.13 | 6.25 | |

| VCM | 0.78–3.13 | 1.56 | 3.13 | |

| DMPPC-resistant S. epidermidis (34) | OPC-20011 | 0.78–6.25 | 1.56 | 3.13 |

| CTM | 1.56–12.5 | 3.13 | 6.25 | |

| FMOX | 3.13–100 | 25 | 50 | |

| CAZ | 12.5–>100 | 25 | 100 | |

| CPR | 3.13–50 | 6.25 | 50 | |

| DMPPC | 12.5–>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| VCM | 1.56–3.13 | 1.56 | 3.13 | |

| E. faecalis (27) | OPC-20011 | 0.78–6.25 | 3.13 | 6.25 |

| CTM | 100–>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| FMOX | 100–>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| CAZ | –>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| CPR | 12.5–100 | 50 | 100 | |

| ABPC | 1.56–3.13 | 1.56 | 3.13 | |

| ABPC-susceptible S. pneumoniae (27) | OPC-20011 | <0.006– | <0.006 | <0.006 |

| CTM | 0.025–0.78 | 0.2 | 0.78 | |

| FMOX | 0.025–0.39 | 0.2 | 0.39 | |

| CAZ | 0.0125–6.25 | 0.2 | 0.39 | |

| CPR | <0.006–0.78 | 0.0125 | 0.1 | |

| ABPC | <0.006–0.1 | 0.025 | 0.1 | |

| VCM | 0.05–0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| Non-ABPC-susceptible S. pneumoniae (18) | OPC-20011 | <0.006–0.05 | 0.025 | 0.05 |

| CTM | 3.13–6.25 | 6.25 | 6.25 | |

| FMOX | 1.56–6.25 | 3.13 | 6.25 | |

| CAZ | 1.56–6.25 | 3.13 | 6.25 | |

| CPR | 0.2–0.78 | 0.39 | 0.78 | |

| ABPC | 1.56–3.13 | 3.13 | 3.13 | |

| VCM | 0.05–0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| E. coli (54) | OPC-20011 | 0.39–1.56 | 0.78 | 1.56 |

| CTM | 0.1–0.78 | 0.2 | 0.78 | |

| FMOX | 0.05–0.39 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| CAZ | 0.1–0.78 | 0.2 | 0.78 | |

| CPR | 0.025–0.2 | 0.05 | 0.2 | |

| K. pneumoniae (26) | OPC-20011 | 0.1–6.25 | 1.56 | 3.13 |

| CTM | 0.1–1.56 | 0.2 | 0.39 | |

| FMOX | 0.1–0.78 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| CAZ | 0.1–25 | 0.2 | 0.39 | |

| CPR | 0.05–3.13 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| H. influenzae (20) | OPC-20011 | 0.025–0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| CTM | 0.1–0.78 | 0.2 | 0.39 | |

| FMOX | 0.78–3.13 | 0.78 | 1.56 | |

| CAZ | 0.05–0.39 | 0.2 | 0.2 | |

| CPR | 0.05–0.39 | 0.1 | 0.2 | |

| S. marcescens (27) | OPC-20011 | 1.56–12.5 | 1.56 | 6.25 |

| CTM | 3.13–>100 | 12.5 | 100 | |

| FMOX | 0.78–50 | 0.78 | 6.25 | |

| CAZ | 0.2–25 | 0.39 | 0.78 | |

| CPR | 0.05–0.78 | 0.1 | 0.39 | |

| P. mirabilis (41) | OPC-20011 | 0.05–>100 | 0.39 | 1.56 |

| CTM | 0.2–>100 | 0.78 | 100 | |

| FMOX | 0.2–>100 | 0.39 | 100 | |

| CAZ | 0.05–100 | 0.2 | 6.25 | |

| CPR | <0.006–>100 | 0.1 | 1.56 | |

| P. rettgeri (40) | OPC-20011 | 0.39–3.13 | 0.78 | 1.56 |

| CTM | 0.05–>100 | 0.39 | 100 | |

| FMOX | 0.05–6.25 | 0.1 | 3.13 | |

| CAZ | 0.05–6.25 | 0.2 | 1.56 | |

| CPR | <0.006–0.39 | 0.025 | 0.2 | |

| P. aeruginosa (27) | OPC-20011 | 12.5–>100 | 25 | 100 |

| CTM | –>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| FMOX | –>100 | 100 | 100 | |

| CAZ | 1.56–50 | 3.13 | 50 | |

| CPR | 3.13–100 | 12.5 | 50 | |

Against E. coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, OPC-20011 inhibited 90% of the strains at 1.56 and 3.13 μg/ml, respectively, which were 2 to 32 times higher than the MIC90s of the reference compounds. Against H. influenzae, OPC-20011 inhibited 90% of the strains at 0.2 μg/ml, which was equal to or two to eight times lower than the MIC90s of the reference compounds. Against Serratia marcescens, Proteus mirabilis, and Providencia rettgeri, OPC-20011 inhibited 90% of the strains at 6.25, 1.56, and 1.56 μg/ml, respectively, at least 64 times more active than CTM and FOMX. Weaker activity was observed with all of the test compounds against Pseudomonas aeruginosa: the MIC90s were 50 to 100 μg/ml.

PBP affinity.

In order to explain the antibacterial activities of OPC-20011, the binding of OPC-20011 to PBPs in S. aureus FDA 209-P, MRSA 5143, S. pneumoniae C0096, and E. coli NIHJ JC-2 was compared with those of the reference compounds. The results are shown in Tables 3 to 5. The IC50s of OPC-20011 for PBP2, -3, and -4 in S. aureus FDA 209-P were generally 3 to >64 times lower than those of CTM, CAZ, FMOX, and CPR. For PBP2′ in MRSA 5143, the IC50 of OPC-20011 was 2.0 μg/ml, which was approximately 370 and 1,050 times as high as those of CPR and FMOX, respectively. The IC50s of OPC-20011 for PBP1A and -1B in S. pneumoniae C0096 were 9 to 50 times lower than those of ABPC. PBP1B, -2 and -3 in E. coli NIHJ JC-2 showed the highest affinity for OPC-20011 compared with FMOX and CPR, but OPC-20011 did not bind to PBP1A, -4, and -5 at concentrations as high as 62.5 μg/ml.

TABLE 3.

Binding of OPC-20011 and reference compounds to PBPs in S. aureus FDA 209-P

| Compound | IC50 (μg/ml)a

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBP1 | PBP2 | PBP3 | PBP4 | |

| OPC-20011 | NDb | 0.068 | 0.053 | 0.065 |

| OPC-20026 | ND | 0.303 | 0.501 | 0.199 |

| CTM | 10.946 | 0.273 | 0.282 | 0.283 |

| CAZ | ND | 0.360 | >3.13 | 0.327 |

| FMOX | 32.545 | 0.212 | 0.370 | 1.027 |

| CPR | ND | 0.163 | 3.086 | 0.022 |

Binding affinities of test compounds for PBPs are expressed as the concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) required to prevent 50% of the binding of [14C]benzylpenicillin to each PBP.

ND, not detected.

TABLE 5.

Binding of OPC-20011 and reference compounds to PBPs in E. coli NIHJ JC-2

| Compound | IC50 (μg/ml)a

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBP1A | PBP1B | PBP2 | PBP3 | PBP4 | PBP5 | PBP6 | |

| OPC-20011 | >62.5 | 2.56 | <0.1 | <0.1 | >62.5 | >62.5 | 18.84 |

| OPC-20026 | 1.52 | 1.57 | 1.74 | <0.1 | >62.5 | >62.5 | >62.5 |

| FMOX | 0.10 | 1.26 | >62.5 | <0.1 | 1.22 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| CPR | 10.13 | 2.78 | 4.04 | <0.1 | 38.43 | >62.5 | >62.5 |

Binding affinities of test compounds for PBPs were expressed as the concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) required to prevent 50% of the binding of [14C]benzylpenicillin to each PBP.

Protective effects in vivo.

The therapeutic effects of OPC-20011 and the reference compounds against acute systemic infections in mice are shown in Table 6. The efficacies of OPC-20011 against S. aureus Smith, MRSA 5120, S. pneumoniae Type III, and S. pneumoniae C0096 were approximately 2 to over 100 times greater than those of the other compounds tested. OPC-20011 showed protective effects equivalent to those of VCM against MRSA 5143 and to those of ABPC against E. faecalis, and it was approximately 8 to over 40 times more effective than the other reference compounds. OPC-20011 also had ED50s ranging from 0.06 to 8.4 mg/kg for the infections caused by gram-negative pathogens, except P. aeruginosa. Against P. aeruginosa T0017, the efficacy of OPC-20011 was nearly equal to that of aztreonam (AZT) but less than that of CAZ, though the other β-lactams, CTM and FMOX, did not exhibit any protective effects.

The therapeutic effects of OPC-20011 and VCM against experimental respiratory tract infection caused by MRSA 5143 are shown in Table 7. A significant decrease in the number of viable cells in the lungs was observed at concentrations of ≥5 mg/kg for OPC-20011 and ≥10 mg/kg for VCM. The efficacy of OPC-20011 at 5 mg/kg was almost equal to that of VCM at 20 mg/kg.

TABLE 7.

Therapeutic effects of OPC-20011 and VCM in an experimental murine model of respiratory tract infection caused by MRSA 5143a

| Compound | Dose (mg/kg) | Log viable bacilli in lungsb (± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 0 | 7.81 ± 0.75 |

| OPC-20011 | 2.5 | 5.92 ± 1.23 |

| 5 | 3.58 ± 0.47** | |

| 10 | 2.21 ± 0.76** | |

| VCM | 5 | 7.14 ± 1.32 |

| 10 | 5.35 ± 1.47* | |

| 20 | 4.48 ± 0.51** |

Challenge dose was 5.5 × 106 CFU/mouse.

Viable bacilli in lungs were counted at 24 h after final treatment. The difference between the control and each treated group was determined by using a two-tailed Dunnett’s test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

The therapeutic effects of OPC-20011, ABPC, and VCM against experimental respiratory tract infection caused by S. pneumoniae T0005 are shown in Table 8. A significant decrease in the number of viable cells in the lungs was observed at concentrations of ≥2.5 mg/kg for OPC-20011 and 20 mg/kg for ABPC with a single treatment. The efficacy of OPC-20011 at 2.5 mg/kg was almost equal to that of ABPC at 10 to 20 mg/kg. When three doses were given, no viable bacilli were observed in any of the OPC-20011-treated groups. With VCM, a significant decrease was observed when three doses were given, though no decrease was observed with a single treatment.

TABLE 8.

Therapeutic effects of OPC-20011, ABPC, and VCM in an experimental murine model of respiratory tract infection caused by S. pneumoniae T0005a

| Compoundc | Dose (mg/kg) | Log viable bacilli in lungsb (± SD)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Single | Three times | ||

| Control | 0 | 6.42 ± 0.82 | 7.21 ± 0.5 |

| OPC-20011 | 2.5 | 4.0 ± 1.5* | <1** |

| 5 | 3.08 ± 1.18* | <1** | |

| 10 | 1.73 ± 0.89** | <1** | |

| 20 | 0.84 ± 1.03** | <1** | |

| ABPC | 2.5 | 6.02 ± 1.08 | 6.23 ± 1.51 |

| 5 | 5.55 ± 1.52 | 3.67 ± 0.73** | |

| 10 | 3.76 ± 2.28 | 2.09 ± 0.96** | |

| 20 | 2.98 ± 1.29* | 1.73 ± 0.95** | |

| VCM | 5 | 5.09 ± 1.19 | 4.11 ± 2.1* |

| 10 | 5.43 ± 1.81 | <1** | |

| 20 | 4.40 ± 1.2 | <1** | |

| 40 | 3.72 ± 2.09 | <1** | |

Challenge dose was 2.75 × 103 CFU/mouse.

Viable bacilli in lungs were counted at 24 h after final treatment. Single, single treatment at 24 h after infection; three times, treatments at 24, 40, and 48 h after infection. The difference between the control and each treated group was determined by using a two-tailed Dunnett’s test (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

MICs of OPC-20011, ABPC, and VCM against S. pneumoniae T0005 were 0.003, 0.2, and 0.39 μg/ml, respectively.

Bactericidal activity.

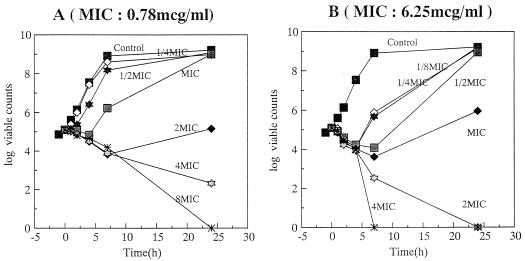

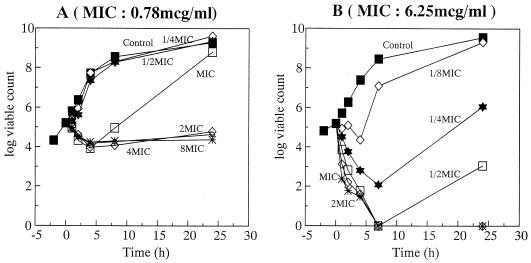

The bactericidal activity of OPC-20011 was compared with that of VCM against MRSA 5143 and MRSA 5120 (Fig. 2 and 3). Against MRSA 5143, both OPC-20011 (at twice the MIC) and VCM (at four times the MIC) showed bactericidal activity. Against MRSA 5120, however, OPC-20011 showed bactericidal activity at one-fourth the MIC within 8 h and produced a rapid decrease in the number of viable cells at the same concentration, while VCM did not show any bactericidal activity even at a concentration of eight times the MIC. The MICs against the obvious regrowth of MRSA 5120 exposed to concentrations of OPC-20011 below the MIC for 24 h were not changed.

FIG. 2.

Bactericidal activities of VCM (A) and OPC-20011 (B) against MRSA 5143.

FIG. 3.

Bactericidal activities of VCM (A) and OPC-20011 (B) against MRSA 5120.

Affinity for serum proteins of different animal species.

The affinities of the filters (Centrisart Cutoff 20000) used in this binding study for OPC-20011 were checked. The rate of binding of OPC-20011 to the filters was less than 1%. The binding percentage (± standard deviation [SD]) of OPC-20011 to serum proteins prepared from ICR mice, SD rats, NEZ rabbits, beagle dogs, cynomolgus monkeys, and healthy human donors are shown in Table 9. The rates of binding of OPC-20011 to serum proteins from humans and mice were almost equal.

TABLE 9.

Binding of OPC-20011 to serum proteins from different animal species

| Animal | % Binding to serum proteins (± SD) |

|---|---|

| Mouse | 29.0 ± 3.0 |

| Rat | 6.4 ± 2.5 |

| Rabbit | <1 |

| Dog | 5.8 ± 1.5 |

| Monkey | 1.7 ± 3.1 |

| Human | 23.2 ± 1.7 |

DISCUSSION

OPC-20011 is a 2-oxaisocephem antibiotic that has never been introduced to clinical use. In a previous report about 2-oxaisocephems, it was shown to have limited antibacterial activity (7). Then what is the advantage of a 2-oxaisocephem? The answers were obtained in this study. The antibacterial activities and binding to PBPs of OPC-20011 and OPC-20026, a 1-sulfur analog with the same substituents as OPC-20011, were compared. The antibacterial activity of the 2-oxaisocephem was 2 to 16 times more potent than that of the 1-sulfur cephem. This potency of the 2-oxaisocephem was considered to be due to the high affinity of the PBP in S. aureus, including MRSA.

None of the commercially available cephem antibiotics that were tested had any activity against E. faecalis; OPC-20011, the oxaisocephem antibiotic, showed antibacterial activity similar to that of ABPC, although the 1-sulfur analog with the same substituents as OPC-20011 was not active against this organism.

MRSA has an additional PBP2′, which is involved in resistance to β-lactams (26). There have also been many recent reports about other factors related to DMPPC resistance (2, 5, 10, 11, 17). The mechanism of resistance in MRSA is more complex than PBP2′ alone. Some other factors, such as femA, the glycine content of peptidoglycan, and the enhancement of autolysis, have been reported to be essential for expression of DMPPC resistance. However, PBP2′ is an essential factor for DMPPC resistance (16, 19, 25), and inhibiting the activity or the expression of PBP2′ is the best way to solve the resistance problem. PBP2′ bound OPC-20011 approximately 370 to 1,050 times better than the other β-lactams. This may be the reason for the MIC for OPC-20011 against all of the clinically isolated MRSAs, which was less than 6.25 μg/ml.

Although VCM is probably the best drug that can be used for MRSA infections at present, VCM-intermediate MRSA has been isolated in Japan (12). Though the in vitro anti-MRSA activity of OPC-20011 was less than that of VCM, the in vivo efficacy of OPC-20011 in MRSA infection models was almost equal to or greater than that of VCM. In particular, OPC-20011 showed a therapeutic effect two to four times as potent as that of VCM in the model of respiratory tract infection, even though OPC-20011 showed activity almost equal to that of VCM in systemic infection in mice caused by the same organism, MRSA 5143. One reason may be related to the bactericidal activities of these compounds for MRSA. The bactericidal activity of OPC-20011 for MRSA 5120 was greater than that for MRSA 5143, and these bactericidal activities were well correlated to the efficacy in vivo. Also, the distribution of OPC-20011 in lung tissue was approximately 15 μg/ml after a single administration at a dose of 20 mg/kg (data not shown). It is possible that VCM cannot reach sufficient tissue concentrations due to its poor distribution, as the sputum level of VCM in patients is 2 to 3 μg/ml. This is considered to be consistent with the results of our study comparing the therapeutic effects of OPC-20011 and VCM on respiratory tract infection in rats.

The rate of bacterial eradication by VCM in combination with other β-lactams was reported to be approximately 60% in polymicrobial infections (18). Furthermore, it has been reported that during clinical use, VCM induces microbial substitution (1) when used alone, because of its narrow spectrum. Since OPC-20011 has a broad antibacterial spectrum covering not only gram-positive but also gram-negative pathogens, even if used alone, its induction rate of microbial substitution may be less than that of VCM.

OPC-20011 was the most effective of the compounds tested in this study against S. pneumoniae. The reason for this potent activity was considered to be the high PBP affinity. Though S. pneumoniae C0096 is insensitive to ABPC because of the drug’s weak binding to PBP1A, this PBP showed higher affinity for OPC-20011. Although we tried to examine the therapeutic efficacy in a respiratory tract infection model, to our disappointment, we could not establish the model with this organism. However, the efficacy of OPC-20011 was significantly better than those of ABPC and VCM in a corresponding model with the non-ABPC-susceptible S. pneumoniae T0005.

In conclusion, OPC-20011 has broad-spectrum antibacterial activity, not only against MRSA, but also against penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae and E. faecalis. It is expected to demonstrate activity against gram-negative pathogens equivalent to those of the selected reference compounds. OPC-20011 is thus considered to be an antibacterial agent which can overcome the shortcomings of some of the existing β-lactam antibiotics.

TABLE 4.

Binding of OPC-20011 and reference compounds to PBPs in S. pneumoniae C0096

| Compound | IC50 (μg/ml)a

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBP1A | PBP1B | PBP2X | PBP2 | PBP3 | |

| OPC-20011 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 1.28 | >6.4 | <0.025 |

| ABPC | 7.16 | 0.70 | 0.65 | >6.4 | <0.025 |

Binding affinities of test compounds for PBPs are expressed as the concentration (in micrograms per milliliter) required to prevent 50% of the binding of [14C]benzylpenicillin to each PBP.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Yoshiki Obana, Norimitsu Hariguchi, Kaoru Yokomi, and Azusa Tateishi for their superb technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aoki Y. MRSA infection. Clinica. 1992;19:182–187. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berger-Bachi B, Barberis-Maino L, Strassle A, Kayser F H S. FemA, a host-mediated factor essential for methicillin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: molecular cloning and characterization. Mol Gen Genet. 1989;219:263–269. doi: 10.1007/BF00261186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chopra I, Hodgson J, Metcalf B, Poste G. The search for antimicrobial agents effective against bacteria resistant to multiple antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:497–503. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen M L. Epidemiology of drug resistance: implications for a post-antimicrobial era. Science. 1992;257:1050–1055. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Jonge B L M, de Lencastre H, Tomasz A. Suppression of autolysis and cell wall turnover in heterogeneous Tn551 mutants of a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1105–1110. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.3.1105-1110.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle T W, Belleau B, Luh B-Y, Ferrari C F, Cunningham M P. Nuclear analogs of β-lactam antibiotics. I. Synthesis of O-2-isocephems. Can J Chem. 1977;55:468. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doyle T W, Douglas J L, Belleau B, Conway T T, Ferrari C F, Horning D E, Lim G, Luh B-Y, Martel A, Menard M, Morris L R. Nuclear analogs of β-lactam antibiotics. XIII. Structure activity relationships in the isocephalosporin series. Can J Chem. 1980;58:2508. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glaser V. Therapeutic alternatives for drug-resistant bacterial infections. SPECTRUM therapy markets and emerging technologies. Waltham, Mass: Decision Resources, Inc.; 1996. pp. 104–114. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldstein J G. 30 years of penicillin-resistant S. pneumoniae: myth or reality? Lancet. 1997;350:233–234. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)62222-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gustafson J E, Berger-Bachi B, Strassle A, Wilkinson B J. Autolysis of methicillin-resistant and -susceptible Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:566–572. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.3.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hartman B J, Tomasz A. Expression of methicillin resistance in heterogeneous strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1986;29:85–92. doi: 10.1128/aac.29.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiramatsu K, Hanaki H, Ino T, Yabuta K, Oguri T, Tenover F C. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical strain with reduced vancomycin susceptibility. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1997;40:135–136. doi: 10.1093/jac/40.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ishikawa H, Tsubouchi H, Yasumura K. Synthesis and biological activity of new optically active 2-oxaisocephems: 3-(N-alkylpyridinium-4′-thio) methyl derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1994;4:1147–1152. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobs M R. Treatment and diagnosis of infections caused by drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:119–127. doi: 10.1093/clinids/15.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klugman K P. Pneumococcal resistance to antibiotics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1990;3:171–196. doi: 10.1128/cmr.3.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuwahara-Arai K, Kondo N, Hori S, Tateda-Suzuki E, Hiramatsu K. Suppression of methicillin resistance in a mecA-containing pre-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strain is caused by the mecI-mediated repression of PBP 2′ production. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:2680–2685. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.12.2680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maidhof, H., B. Reinicke, P. Blümel, B. Berger-Bächi, and H. Labischinski. femA, which encodes a factor essential for expression of methicillin resistance, affects glycine content of peptidoglycan in methicillin-resistant and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus strains. J. Bacteriol. 173:3507–3513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Shimizu K, Orizu M, Kanno H, Kitamura S, Konishi T, Soma K, Nishitani H, Noguchi Y, Hasegawa S, Hasegawa H, Wada K MRSA Infection Committee. Clinical studies on vancomycin in the treatment of MRSA infection. Jpn J Antibiot. 1996;49:782–799. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ryffel C, Kayser F H, Berger-Bächi B. Correlation between regulation of mecA transcription and expression of methicillin resistance in staphylococci. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:25–31. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.1.25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Spratt B G. Biochemical and genetical approaches to the mechanism of action of penicillin. Philos Trans R Soc Lond. 1980;289:273–283. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1980.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spratt B G, Pardee A B. Penicillin-binding proteins and cell shape in E. coli. Nature. 1995;254:516–517. doi: 10.1038/254516a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tenover F C, Hughes J M. The challenges of emerging infectious diseases. JAMA. 1996;275:300–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomasz A. A report on the Rockefeller University workshop. Multiple-antibiotic-resistant pathogenic bacteria. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:1247–1251. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199404283301725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsubouchi H, Tsuji K, Yasumura K, Matsumoto M, Shitsuta T, Ishikawa H. Synthesis and biological evaluation of a series of new parenteral optically active 3-[[(N-alkylpyridinium-4′-yl)thio]methyl]-2-oxaisocephems. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2152–2157. doi: 10.1021/jm00012a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ubukata K, Nonoguchi R, Matsuhashi M, Konno M. Expression and inducibility in Staphylococcus aureus of the mecA gene, which encodes a methicillin-resistant S. aureus-specific penicillin-binding protein. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:2882–2885. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2882-2885.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Utsui Y, Yokota T. Role of an altered penicillin-binding protein in methicillin- and cephem-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1985;28:397–403. doi: 10.1128/aac.28.3.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wakebe H, Mitsuhashi S. Comparative in vitro activities of a new quinolone, OPC-17116, possessing potent activity against gram-positive bacteria. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2185–2191. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.10.2185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]