Abstract

Purpose:

To quantitatively analyze lung elasticity in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) using elastic registration based on 3-dimensional pulmonary magnetic resonance imaging (3D-PMRI) and to assess its’ correlations with the severity of IPF patients.

Material and Methods:

Thirty male patients with IPF (mean age: 62±6 y) and 30 age-matched male healthy controls (mean age: 62±6 y) were prospectively enrolled. 3D-PMRI was acquired with a 3-dimensional ultrashort echo time sequence in end-inspiration and end-expiration. MR images were registered from end-inspiration to end-expiration with the elastic registration algorithm. Jacobian determinants were calculated from deformation fields on color maps. The log means of the Jacobian determinants (Jac-mean) and Dice similarity coefficient were used to describe lung elasticity between 2 groups. Then, the correlation of lung elasticity with dyspnea Medical Research Council (MRC) score, exercise tolerance, health-related quality of life, lung function, and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis on chest computed tomography were analyzed.

Results:

The Jac-mean of IPF patients (−0.19, [IQR: −0.22, −0.15]) decreased (absolute value), compared with healthy controls (−0.28, [IQR: −0.31, −0.24], P<0.001). The lung elasticity in IPF patients with dyspnea MRC≥3 (Jac-mean: −0.15; Dice: 0.06) was significantly lower than MRC 1 (Jac-mean: −0.22, P=0.001; Dice: 0.10, P=0.001) and MRC 2 (Jac-mean: −0.21, P=0.007; Dice: 0.09, P<0.001). In addition, the Jac-mean negatively correlated with forced vital capacity % (r=−0.487, P<0.001), forced expiratory volume 1% (r=−0.413, P=0.004), TLC% (r=−0.488, P<0.001), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide % predicted (r=−0.555, P<0.001), 6-minute walk distance (r=−0.441, P=0.030) and positively correlated with respiratory symptoms (r=0.430, P=0.042). Meanwhile, the Dice similarity coefficient positively correlated with forced vital capacity % (r=0.577, P=0.004), forced expiratory volume 1% (r=0.526, P=0.012), diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide % predicted (r=0.435, P=0.048), 6-minute walk distance (r=0.473, P=0.016), final peripheral oxygen saturation (r=0.534, P=0.004), the extent of fibrosis on chest computed tomography (r=−0.421, P=0.021) and negatively correlated with activity (r=−0.431, P=0.048).

Conclusion:

Lung elasticity decreased in IPF patients and correlated with dyspnea, exercise tolerance, health-related quality of life, lung function, and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis. The lung elasticity based on elastic registration of 3D-PMRI may be a new nonradiation imaging biomarker for quantitative evaluation of the severity of IPF.

Key Words: elastic registration, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, magnetic resonance imaging

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is characterized by abnormal deposition of collagen or proliferation of fibroblasts that can synthesize collagen. The development of these irreversible processes leads to lung compliance, lung shrinkage, and elasticity gradually worsening, along with breathlessness, decreases in gas exchange and exercise tolerance, as well as poorer quality of life and lower survival.1–4

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) can provide a global assessment of lung function but are not sensitive to subtle or local functional changes.5 Chest computed tomography (CT) plays a vital role in the diagnosis and evaluation of IPF in usual interstitial pneumonia features and quantitative analysis of fibrotic lesions of IPF6,7; however, radiation exposure and insensitivity to subtle lung morphologic alterations are its main disadvantages. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a radiation-free technique and has been emerging as a promising method in the assessment of interstitial lung disease (ILD).8,9 Magnetic resonance elastography indicated that parenchymal shear stiffness was increased in patients with fibrotic ILD when compared with normal controls10; however, it depends on a special sequence and device. Dynamic MRI may be used to analyze respiratory movements by coupling dynamic acquisition and imaging registration methods.11 Three-dimensional ultrashort echo time MRI allowed for functional imaging of ventilation inhomogeneity within a few breath-holds in patients with cystic fibrosis.12 Recently, the elastic registration algorithm has been used to find the transformation and provides a robust map of local lung displacement vectors, which enables the evaluation of lung deformation between inspiration and expiration.13–17 Chassagnon et al reported that lung shrinkage based on the elastic registration algorithm of chest CT can be used to assess the worsening of ILD in patients with systemic sclerosis, indicating that lung shrinkage is an additional CT marker in the follow-up of f-ILD.3,18 Furthermore, they adopted elastic registration algorithm on MRI to show less lung deformation in SSc patients with pulmonary fibrosis compared with patients without fibrosis.19

At present, the characteristic of lung elasticity in patients with IPF and its relationship with the severity remains unknown. Thus, the aim of this study is to analyze the characteristics of lung elasticity with elastic registration based on 3D-MRI in patients with IPF and explore its correlation with dyspnea, PFTs, exercise tolerance, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis on chest CT.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design

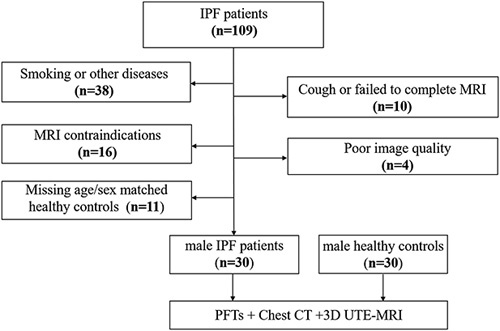

This prospective study was approved Institutional review board of our hospital 2019-123-K85-1 and all participants provided written informed consent. As Figure 1 demonstrated that IPF patients and sex/age-matched healthy controls were evaluated for enrollment from March 2021 to December 2021, followed by inclusion and exclusion criteria. IPF patients were diagnosed by the multidisciplinary team diagnosis based on the 2018 American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS), the Japanese Respiratory Society (JRS), and the Latin American Thoracic Association (ALAT) criteria.1 All participants underwent MRI, chest CT, PFTs, and a 6-minute walk test within 24 hours. The age-matched males with normal chest CT and PFTs were included in the control group. Exclusion criteria include the following: (1) The subjects with smoking, hypertension, diabetes, scoliosis, neuromuscular diseases, connective tissue disease, and tumor; (2) participants with MRI contraindications, such as a pacemaker or claustrophobia; (3) participants who failed to complete MRI or CT had poor images quality; (4) Missing age and sex-matched healthy controls. The definition of poor image quality for MRI and CT, as evaluated by a chest radiologist with 20 years of experience, refers to images that contain noticeable artifacts and are deemed unsuitable for further processing.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of inclusion and exclusion criteria of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

Clinical Data

For patients with IPF, the severity of resting dyspnea was quantified by Medical Research Council (MRC) scale.20 The HRQoL assessment was assessed using a respiratory-specific Questionnaire of the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ),21 which mainly included 3 different domains: respiratory symptoms, activity, and psychosocial impact of the disease. Higher scores (ranging from 0 to 100) correspond to worse quality of life. In addition, according to the standardized criteria of the 6-minute walk test,22 the final peripheral oxygen saturation(SpO2) and walking distance(6-MWD) were also measured.

Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs)

All participants underwent PFTs (MasterScreen, Vyaire Medical GmbH, Hoechberg, Germany), and the collected measurements included the percentage of predicted forced vital capacity (FVC%), percentage of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1%), FEV1/FVC%, percentage of predicted total lung capacity (TLC%), and percentage of predicted DLco corrected for measured hemoglobin (DLco%). The tests were performed according to the standards of ERS/ATS.23

Chest CT and Quantification of Pulmonary Fibrosis

All participants underwent chest CT with multi-section CT devices (Toshiba Aquilion ONE TSX-301C/320; Philips iCT/256) in full inspiration. The whole lung was craniocaudally scanned in a supine position from the lung apex to the lowest hemidiaphragm during a single breath-hold. According to CT criteria, acquisition and reconstruction parameters are as follows: tube voltage=100 to 120 kV, tube current=100 to 300 mAs, section thickness=0.625 to 1 mm, table speed=39.37 mm/s, gantry rotation time=0.8 s, and reconstruction increment=1-1.25 mm.

Segmentation of lung and fibrosis lesions was performed with the software InferScholar (https://www.infervision.com/).7 The full lung region was automatically segmented and then manually corrected by 1 radiologist. According to Christe et al,24 fibrosis lesions were defined as the sum of reticulation and honeycombing signs on chest CT, which were manually outlined. The extent of chest CT patterns was expressed as the percentage of lesions from total lung volume.

MRI Examinations

Before the MRI scan, all participants were trained to practice quiet breathing and deep breathing in the supine position. The participants underwent pulmonary MRI on a 1.5T MRI scanner (MAGNETOM Aera; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with an 18-channel phased-array body coil. MRI was acquired with the 3-dimensional, ultrashort echo time sequence (3D-UTE) at the coronal plane in full end-inspiration and end-expiration. The key parameters as following: repetition time=2.73 msec; echo time=0.05 msec; flip angle=5°; field-of-view=500×500 mm; slice thickness=2.5 mm; matrix=240×240; in-plane resolution=2.08×2.08; spiral duration=1800 μsec. Image reconstructions used the non-uniform Fourier Transform method. The subjects were respectively instructed to hold breathing 2 times on end-inspiration and end-expiration. The total acquisition time was 16 seconds.

Elastic Registration on 3D-UTE Images

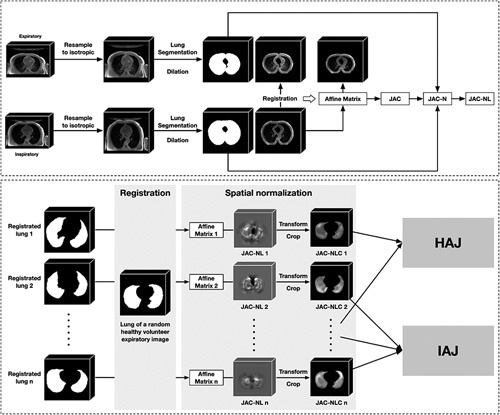

As shown in Figure 2, there were 4 steps to perform elastic registration on 3D-UTE images.

FIGURE 2.

The steps of inspiratory to expiratory elastic registration of transversal pulmonary MRI. The inspiratory and expiratory images of the participant were subjected to isotropic resampling, and then the lung and peri-lung regions were extracted as ROI. Based on the ROI only, the inspiratory image was registered to the expiratory image to obtain the affine transformation matrix, which was used to image transformation and quantitative analysis. For each participant, the JAC, JAC-N, and JAC-NL were all derived from the affine transformation matrix. The registration lung regions of all participants were further registered into a common space, from which the JAC-NL for each participant in the same space was obtained, called JAC-NLC. Finally, participants were grouped, and various comparisons and analyses were made between groups based on the JAC-NLC. JAC indicates Jacobian determinant; JAC-N, normalized JAC; JAC-NL, logarithmic JAC-N; ROC, regions of interest.

Step 1 : Lung segmentation. All MRI sequences were first preprocessed by isotropic sampling with 1 mm. Then, the lung regions were annotated by a junior radiologist (J.H., 7 y’ experience) and checked by a senior radiologist (M.L., 20 y’ experience) to ensure that the lungs were completely and accurately identified. Considering the peri-lung area (the peri-lung area was defined as the area within 10 pixels distance from the lung mask. The purpose of including the peri-lung area is to observe the information of more regions during the registration process to achieve better registration performance), the lung segmentation was dilated by 10 pixels to obtain a registration mask.

Step 2 : Imaging registration. The ElasticSyN algorithm is a powerful open-source software. Advanced Normalization Tools (ANTs) (https://github.com/ANTsX/ANTs) were used to perform elastic registration of inspiratory to expiratory MR images, which is a commonly used and stable registration algorithm.25 The output of the registration algorithm is an affine transformation matrix, which can be used not only for image transformation but also for quantitative analysis.

Step 3 : Quantitative lung deformation. As for each respiratory phase, the Jacobian determinant (JAC) was calculated through the affine transformation matrix resulting from registration. For each participant’s JAC, it was first normalized according to the ratio of inspiratory and expiratory lung volumes to get JAC-N, then log JAC-N to get JAC-NL (JAC is a 3-dimensional matrix calculated based on elastic registration, with the same size as the registration target image. The value at each position represents whether the voxel at that position is stretched (>1), shrunk (<1), or unchanged (=1) during the registration process. Considering that the lung sizes of different individuals may vary, the ratio of the lung volumes during inspiratory and expiratory is used to normalize JAC, denoted as JAC-N, to alleviate bias. The value range of JAC-N is from 0 to positive infinity, so it can be subjected to logarithmic transformation to scale its value range from negative infinity to positive infinity for better observation and comparison. The logarithmically transformed result is denoted as JAC-NL. The value in the JAC-NL indicates whether the voxel is stretched (greater than 0) or shrunk (less than 0).

Step 4 : Generation of the health average Jacobian map. An expiratory image of a randomly selected healthy volunteer was chosen as a common template. The JAC-NL for each participant was registered to this common template based on their registration mask, yielding the corresponding JAC-NLC. After that, the JAC-NLCs of all healthy volunteers were averaged to generate the health average Jacobian map (HAJ).

Qualitative Analysis

To facilitate a visually intuitive comparison between the 2 groups, that is, IPF patients and healthy controls, we generated an average Jacobian map for the IPF patients’ template. The process of generating this IPF average Jacobian map (IAJ) mirrored that of the HAJ, averaging the JAC-NLCs for all IPF patients. Then, project the IPF average Jacobian map or HAJ to different directions along the x, y, and z axis to get the visual deformation on coronal, sagittal, and axial views, respectively.

Quantitative Analysis

For each participant, the mean of their JAC-NL was calculated, denoted as Jac-mean. In addition to the inter-group comparison of Jac-mean, the correlation of Jac-mean with items in the PFT report was also calculated. We defined marked shrinkage lung areas and compared the distribution of areas in different groups. Referring to Chassagnon et al,19 JAC-NL was used to determine marked shrinkage lung areas with a cutoff value of 0.15 (a greater cutoff value indicates marked shrinkage). The marked shrinkage areas of the healthy template were segmented by using this cutoff value as a threshold for the HAJ. For each fibrotic patient, the marked shrinkage areas were segmented using the cutoff value to binary their logarithm Jacobians determinant. The dice similarity coefficient was used to compare how similar each fibrosis patient’s marked shrinkage area was to that of the healthy template. Finally, Dice was used for inter-group comparisons, as well as for correlation analysis with items in the PFT report.

Registration Quality Evaluation

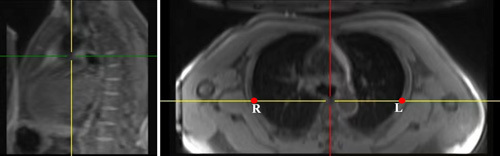

Two metrics were used to evaluate the quality of elastic registration. The first metric was the intersection over union (IoU),26 which measured the degree of overlap between the lung area of the inspiratory image after registration and that of the expiratory image. The second metric measured the distance between the landmark in the inspiratory image after registration and that in the expiratory image.19 Specifically, an observer manually placed 2 categories of landmarks L and R on both inspiratory and expiratory images (Fig. 3). The point L and R were located on the anterior edge of the thoracic vertebra intersecting the chest walls on both sides at the planer of the lower margin of the fourth thoracic vertebra on multiplanar reconstructions. After the registration was completed, the landmarks on the inspiratory image were automatically registered to the expiratory image. The landmarks coordinates were collected to calculate the mean distances of 2 landmarks: DL, the distance between registered landmark-L and original landmark-L in the expiratory image; DR, the distance between 2 landmark-Rs. To verify the repeatability and stability of the registration method, 2 types of respiratory phases (inspiratory and expiratory) were acquired for each participant. The above metrics (IoU, DL, and DR) were calculated for each respiratory phase, and the consistency between the 2 phases was calculated.

FIGURE 3.

The figure shows the position of points L and R. The location of points L and R were manually drawn and derived from the anterior edge of the thoracic vertebra intersecting the chest walls on both sides at the planer of the lower margin of the fourth thoracic vertebra on multiplanar reconstructions (MPR). MPR indicates multiplanar reconstructions

All the above operations were implemented in the Python environment (version 3.8; Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, Del) based on an Ubuntu operating system (version 16.04; Canonical Ltd., London, U.K).

Statistical Analysis

Data were assessed for normal distribution before further statistical calculations. Normally distributed data are presented as mean ± SD and nonnormally distributed data are presented as median with interquartile ranges (IQR). The unpaired t-test and nonparametric methods (quantitative data) or Fisher exact test and χ2 test (categorical variables) were used for comparing different groups. The Spearman correlation coefficient was used to calculate the association between the clinical and the value of elastic registration, and the resulting P values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction. The intraclass coefficients (ICC) were used to determine the repeatability of the method. ICCs were classified from null (=0) to very good (>0.80) and almost perfect (>0.95).27 All statistical analyses were performed with SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA), and statistical significance was assumed when two-tail P<0.05.

RESULTS

Patients’ Characteristics

A total of 109 patients with IPF were initially considered for enrollment, but 79 patients were excluded; ultimately, 30 male patients with IPF (mean age: 62±6 y) and 30 age-matched male healthy controls (mean age: 62±6 y) were recruited (Fig. 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of IPF patients and the controls are depicted in Table 1. The mean and SD values of FVC% predicted (78.5±15.3), FEV1% (80.9±15.6), TLC% (66.3±11.9), and DLco% (52.6±17.5) predicted for IPF patients significantly decreased in comparison with healthy controls. The mean and SD values of 6-MWD and final SpO2 of IPF patients were 464.5±85.5m and 84.9%±9.6%. Based on dyspnea score, there are 6 (20.0%), 16 (53.3%), 5 (16.7%), and 3 (10.0%) patients with IPF, respectively, in MRC 1, MRC 2, MRC 3, and MRC 4. The median score of quality of life for respiratory symptoms, activity, psychosocial impact, and total were 51.4 (IQR: 30.4, 63.6), 47.7 (IQR: 29.5, 59.5), 16.1 (IQR: 7.6, 34.9), and 33.5 (IQR: 17.4, 46.4), respectively. Lesion of pulmonary fibrosis on chest CT was (18.0±11.8)%.

TABLE 1.

The Characteristics of All Participants

| Patients | IPF (N=30) | Control (N=30) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age (mean± SD, y) | 62±6 | 62±6 | 0.834 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 30 (100.0) | 30 (100.0) | — |

| Height (mean± SD, cm) | 168.6±6.9 | 170.9±5.0 | 0.147 |

| Weight (mean± SD, kg) | 72.4±11.4 | 74.3±7.5 | 0.463 |

| BMI (mean± SD, m/kg2) | 25.1±2.8 | 25.4±2.3 | 0.613 |

| Pulmonary function (mean± SD) | |||

| FVC % predicted | 78.5±15.3 | 105.2±9.6 | <0.001 |

| FEV1% predicted | 80.9±15.6 | 100.4±9.6 | <0.001 |

| FEV1/FVC% predicted | 82.2±5.9 | 82.4±9.8 | 0.923 |

| TLC % predicted | 66.3±11.9 | 97.4±9.5 | <0.001 |

| DLco % predicted | 52.6±17.5 | 101.3±14.5 | <0.001 |

| HRCT patterns, n (%) | |||

| UIP | 23 (76.7) | — | — |

| Possible UIP | 7 (23.3) | — | — |

| 6-MWT (mean± SD) | |||

| 6-MWD (m) | 464.5±85.5 | — | — |

| Final SpO2 (%) | 84.9±9.6 | — | — |

| Dyspnea Score (percentage, %) | |||

| 1 | 6 (20.0) | — | — |

| 2 | 16 (53.3) | — | — |

| 3 | 5 (16.7) | — | — |

| 4 | 3 (10.0) | — | — |

| 5 | 0 | — | — |

| HRQoL (median, IQR) | |||

| Respiratory symptoms | 51.4 (30.4, 63.6) | — | — |

| Activity | 47.7 (29.5, 59.5) | — | — |

| Psychosocial impact | 16.1 (7.6, 34.9) | — | — |

| Total | 33.5 (17.4, 46.4) | — | — |

| Pulmonary fibrosis (mean± SD, %) | 18.0±11.8 | — | — |

— indicated that no values were present and no further comparison could be made.

6-MWD indicates 6-minute walk distance; 6-MWT, 6-minute walk test; BMI, body mass index; DLco, diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; IPF, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation; TLC, total lung capacity; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Evaluation of Elastic Registration Quality

The mean value of IoU was 0.88±0.04. In addition, the mean distance between the landmark-Rs and landmark-Ls were 7.2±4.5 mm and 7.8±4.8 mm, respectively. The inter-observer agreement between the 2 respiratory phases was very good (IoU, ICC=0.83; Distances R, ICC=0.80; Distances L, ICC=0.82).

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Lung Elasticity

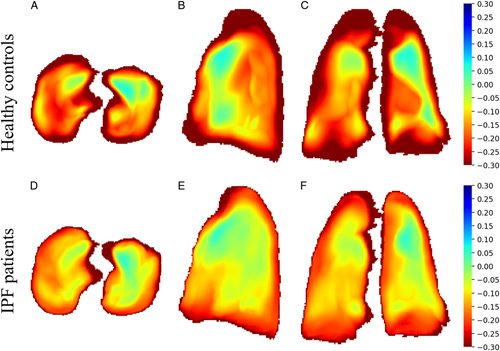

Visual analysis of color maps showed differences in lung elasticity among the IPF patients and healthy controls (Fig. 4). The areas with marked deformation during expiration were found in the peripheral region of the lung in controls, and the lung deformation was decreased in the peripheral region of the lung in patients with IPF. For the median value of Jac-mean, compared with controls (−0.28, IQR: −0.31, −0.24), the IPF patients had smaller values (absolute value) (−0.19, IQR: −0.22, −0.15, P<0.001) of the lung. In addition, the lung elasticity was different between dyspnea groups. As shown in Table 2, the median value of the lung deformation in IPF patients with MRC≥3 (Jac-mean: −0.15, [IQR: −0.16, −0.14]; Dice: 0.06, [IQR: 0.05, 0.08]) were significantly lower than MRC 1 (Jac-mean: −0.22, [IQR: −0.26, −0.21], P=0.001; Dice: 0.10, [IQR: 0.09, 0.10], P=0.001) and MRC 2 (Jac-mean: −0.21, [IQR: −0.27, −0.16], P=0.007; Dice: 0.09, [IQR: 0.09, 0.10], P<0.001). However, the Jac-mean and Dice similarity coefficient was comparable between MRC 1 and MRC 2 (Jac-mean: P=0.210; Dice: P=0.802).

FIGURE 4.

The transversal, sagittal and coronal projection of the mean of Jacobian determinants in each group. Marked deformation areas (in red) were found in the peripheral region of the lung in healthy volunteers(A–C) and decreased in the peripheral region of the lung base in study participants with IPF(D–F) in MRI.

TABLE 2.

The Characteristic of Lung Shrinkage Based on Elastic Registration Between 2 Groups

| Dyspnea Score (IPF) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy controls (n=30) | IPF (n=30) | P | MRC 1 (n=7) | MRC 2 (n=15) | MRC≥3 (n=8) | |

| Jac-mean | −0.28 (−0.31, −0.24) | −0.19 (−0.22, −0.15) | <0.001 | −0.22 (−0.26, −0.21) | −0.21 (−0.27, −0.16)a | −0.15 (−0.16, −0.14)b * c * |

| Dice | — | 0.08 (0.07, 0.10) | — | 0.10 (0.09, 0.10) | 0.09 (−0.09, 0.10)a | 0.06 (0.05, 0.08)b * c * |

The data are presented as median with interquartile ranges.

the difference between MRC 1 and MRC 2.

the difference between MRC 2 and MRC≥3.

the difference between MRC 1 and MRC≥3.

indicated P<0.05

— indicated that no values were present and no further comparison could be made.

IPF indicates idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; MRC, Medical Research Council.

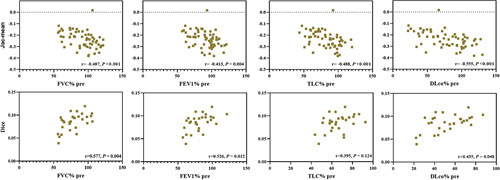

Correlation of Lung Elasticity with PFTs and Clinical Data

The Jac-mean negatively correlated with the FVC% predicted (r=−0.487, P<0.001), FEV1% predicted (r=−0.413, P=0.004), TLC% predicted (r =−0.488, P< 0.001), DLco% predicted (r=−0.555, P< 0.001), while the Dice similarity coefficient showed a positive relationship with FVC% predicted (r=0.577, P=0.004), FEV1% predicted (r=0.526, P=0.012), and DLco% predicted (r=0.435, P=0.048) (Table 3, Fig. 5).

TABLE 3.

Correlations between Lung Shrinkage Based on Elastic Registration and Pulmonary Function Tests

| Jac-mean | Dice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| FVC% | −0.487 | <0.001* | 0.577 | 0.004* |

| FEV1% | −0.413 | 0.004* | 0.526 | 0.012* |

| TLC% | −0.488 | <0.001* | 0.395 | 0.124 |

| DLco% | −0.555 | <0.001* | 0.435 | 0.048* |

Bonferroni correction for multiple correlations P <0.05.

DLco indicates diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide; FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; TLC, total lung capacity.

FIGURE 5.

Relationship between the Jac-mean and Dice similarity coefficient and measurements from pulmonary function tests (FVC% pre, FEV1% pre, TLC% pre, and DLco% pre).

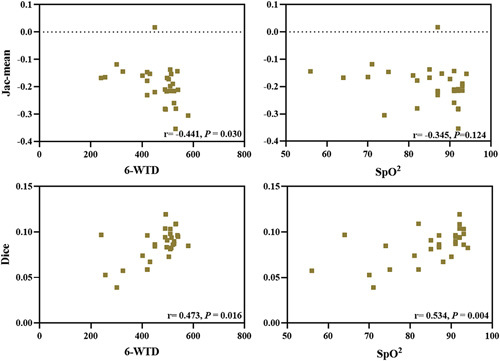

For exercise tolerance, the 6-MWD was correlated with Jac-mean (r=−0.441, P=0.030) and Dice similarity coefficient (r=0.473, P=0.016). Meanwhile, final SpO2 correlated with Dice similarity coefficient (r=0.534, P=0.004) (Table 4, Fig. 6).

TABLE 4.

Correlations between Lung Shrinkage Based on Elastic Registration and Exercise Tolerance

Bonferroni correction for multiple correlations P <0.05.

6-MWD indicates 6-minute-walk distance; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation.

FIGURE 6.

Relationship between the Jac-mean and Dice similarity coefficient and measurements from exercise tolerance (6-MWD and final SpO2). 6-MWD indicates 6-minute walk distance; SpO2, peripheral oxygen saturation.

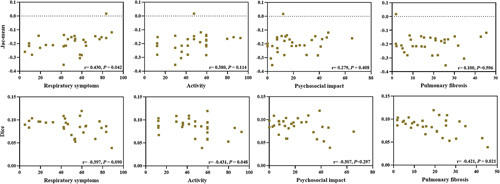

In the aspect of HRQoL, Table 5 and Figure 7 indicated that the Jac-mean correlated with respiratory symptoms (r=0.430, P=0.042), but not related to activity (r=0.380, P=0.114) and psychosocial impact (r=0.279, P=0.408). Moreover, the Dice similarity coefficient negatively correlated with activity (r=−0.431, P=0.048), however, showed no correlation with respiratory symptoms (r=−0.397, P<0.05) and psychosocial impact (r=−0.307, P=0.297). In addition, Figure 7 demonstrated that the Dice similarity coefficient negatively correlated with the extent of pulmonary fibrosis on chest CT (r=−0.421, P=0.021).

TABLE 5.

Correlations between Lung Shrinkage Based on Elastic Registration and Quality of Life

| Jac-mean | Dice | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | P | r | P | |

| Respiratory symptoms | 0.430 | 0.042* | −0.397 | 0.090 |

| Activity | 0.380 | 0.114 | −0.431 | 0.048* |

| psychosocial impact | 0.279 | 0.408 | −0.307 | 0.297 |

Bonferroni correction for multiple correlations P <0.05.

FIGURE 7.

Relationship between the Jac-mean and Dice similarity coefficient and measurements from the health-related quality of life and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis on chest CT. CT indicates computed tomography.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we first evaluated the characteristics of lung elasticity in IPF patients with elastic registration algorithm based on 3-dimensional ultrashort echo time MRI, and our results indicated the lung elasticity was decreased in patients with IPF, especially in dyspnea score with MRC≥3. Furthermore, the decreased lung elasticity correlated with worsening FVC%, FEV1%, TLC%, DLco%, 6-MWD, final SpO2, HRQoL, and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis on chest CT.

The Jac-mean and the Dice similarity coefficient were together used to quantitatively describe the characteristic of lung elasticity in IPF patients, and we found that the lung elasticity of IPF patients worsened in comparison with healthy controls. In healthy controls, the Jacobian maps visually showed that the marked deformation during expiration was in the peripheral region of the lung. In contrast, in patients with IPF, lung deformation was a major loss in the peripheral region of the lung bases, which matches with the lesion distribution of IPF on chest CT. Chassagnon et al19 reported similar results in SSc-ILD patients with less lung deformation during respiratory in patients with fibrosis compared with patients without fibrosis. However, they did not report the relationship between lung elasticity with the severity of diseases such as PFTs, dyspnea, exercise tolerance, HRQoL, and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis in SSc-ILD.

We found that the decreased value of Jac-mean and Dice similarity coefficient correlated with the decreased FVC%, FEV1%, TLC%, and DLco%, which confirms that lung elasticity based on elastic registration is an imaging marker of global and local lung function and indicates that the value of elastic registration between different respiratory phase can be used to regionally quantified and quantitative pulmonary function in patients with IPF. Meanwhile, we also found the value of the Jac-mean and Dice similarity coefficient correlated with 6-MWD, final SpO2, respiratory symptoms, and activity. These results revealed that the reduced lung elasticity is accompanied by decreased exercise tolerance and poor quality of life in patients with IPF. Moreover, it is very important that we found the value of the Dice similarity coefficient also showed a relationship with the extent of pulmonary fibrosis on chest CT, which further proves that the increased fibrosis caused the decrease in lung deformation.

In addition, the accuracy and reproducibility of elastic registration are vital for the evaluation of lung elasticity. Similar to Chassagnon et al,19 we used the landmark distance to evaluate the accuracy of the elastic registration. In addition, we also used IoU to evaluate the registration performance, and the value of IoU reaches 0.88. Furthermore, with the advantage of MRI without the amount of radiation exposure, we verify that the elastic registration results are reproducible by acquiring MR images in end-inspiration and end-expiration and solve the limitation of Chassagnon et al,19 which did not verify the reproducibility of an elastic registration.

There are several limitations of this study. First, our study enrolled a small number of male patients from a single center which limits the generalizability of results. The second limitation is that 3D-PMRI was obtained in the supine position, which may influence lung deformation by higher gravitational forces and reduced rib cage expansion, while PFTs were obtained in the sitting position, which leads to a weaker correlation of lung elasticity with PFTs. In addition, this is a cross-sectional study, and the included patients were still in the long-term follow-up; the application of elastic registration algorithm in the assessment of progress in IPF patients and the suitable measure for the assessment of the disease progression needs further research.

In conclusion, lung elasticity in patients with IPF decreased and correlated with dyspnea, pulmonary function tests, exercise tolerance, HRQoL, and the extent of pulmonary fibrosis. The lung elasticity from the elastic registration algorithm based on MRI may be a new marker in the global and local qualitative and quantitative evaluation of IPF.

Footnotes

This single-center, prospective cohort study was performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital (2019-123-K85-1). And all participants provided written informed consent.

All authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This work was supported by National Key Technologies R & D Program Precision China (No. 2021YFC2500700; 2016YFC0901101) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (No.81870056).

P.Y. and R.Z. work in the Institute of Advanced Research, Infervision Medical Technology Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Xiaoyan Yang, Email: yxy18161659153@126.com.

Pengxin Yu, Email: ypengxin@infervision.com.

Wenqing Xu, Email: wenqingxu2021@163.com.

Haishuang Sun, Email: dr_hssun@163.com.

Jianghui Duan, Email: duanjianghui586@163.com.

Yueyin Han, Email: hanyy66@126.com.

Lili Zhu, Email: zhulili@ccmu.edu.cn.

Bingbing Xie, Email: 874046332@qq.com.

Jing Geng, Email: jing_geng@foxmail.com.

Sa Luo, Email: luosa001@163.com.

Shiyao Wang, Email: steinway0704@outlook.com.

Yanhong Ren, Email: ryhong7561@sina.com.

Rongguo Zhang, Email: zrongguo@infervision.com.

Min Liu, Email: mikie0763@126.com.

Huaping Dai, Email: daihuaping@ccmu.edu.cn.

Chen Wang, Email: cyh-birm@263.net.

REFERENCES

- 1. Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Myers JL, et al. Diagnosis of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;198:e44–e68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Mei Q, Liu Z, Zuo H, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: An Update on Pathogenesis. Front Pharmacol. 2022;12:797292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verschakelen JA. Lung shrinkage: An Additional CT marker in the follow-up of fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Radiology. 2021;298:199–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Haak AJ, Tan Q, Tschumperlin DJ. Matrix biomechanics and dynamics in pulmonary fibrosis. Matrix Biol. 2018;73:64–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mogulkoc N, Brutsche MH, Bishop PW, et al. Pulmonary function in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and referral for lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;164:103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kwon BS, Choe J, Do KH, et al. Computed tomography patterns predict clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respir Res. 2020;21:295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun HLM, Kang H, Yang X, et al. Quantitative analysis of high-resolution computed tomography features of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a structure-function correlation study. Quant Imag Med Surg. 2022;12:3655–3665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lonzetti L, Zanon M, Pacini GS, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of interstitial lung diseases: A state-of-the-art review. Respir Med. 2019;155:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yang X, Liu M, Duan J, et al. Three-dimensional ultrashort echo time magnetic resonance imaging in assessment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, in comparison with high-resolution computed tomography. Quant Imag Med Surg. 2022;12:4176–4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marinelli JP, Levin DL, Vassallo R, et al. Quantitative assessment of lung stiffness in patients with interstitial lung disease using MR elastography. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2017;46:365–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. McClelland JR, Hawkes DJ, Schaeffter T, et al. Respiratory motion models: a review. Med Image Anal. 2013;17:19–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Heidenreich JF, Weng AM, Metz C, et al. Three-dimensional ultrashort echo time MRI for functional lung imaging in cystic fibrosis. Radiology. 2020;296:191–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Garcia Guevara J, Peterlik I, Berger MO, et al. Elastic registration based on compliance analysis and biomechanical graph matching. Ann Biomed Eng. 2020;48:447–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kaczka DW, Cao K, Christensen GE, et al. Analysis of regional mechanics in canine lung injury using forced oscillations and 3D image registration. Ann Biomed Eng. 2011;39:1112–1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishio M, Matsumoto S, Tsubakimoto M, et al. Paired inspiratory/expiratory volumetric CT and deformable image registration for quantitative and qualitative evaluation of airflow limitation in smokers with or without copd. Acad Radiol. 2015;22:330–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shibata H, Iwasawa T, Gotoh T, et al. Automatic tracking of the respiratory motion of lung parenchyma on dynamic magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with pulmonary function tests in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Thorac Imaging. 2012;27:387–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jahani N, Choi S, Choi J, et al. A four-dimensional computed tomography comparison of healthy and asthmatic human lungs. J Biomech. 2017;56:102–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chassagnon G, Vakalopoulou M, Regent A, et al. Elastic registration-driven deep learning for longitudinal assessment of systemic sclerosis interstitial lung disease at CT. Radiology. 2021;298:189–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Chassagnon G, Martin C, Marini R, et al. Use of elastic registration in pulmonary MRI for the assessment of pulmonary fibrosis in patients with systemic sclerosis. Radiology. 2019;291:487–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mahler DA, Weinberg DH, Wells CK, et al. The measurement of dyspnea. Contents, interobserver agreement, and physiologic correlates of two new clinical indexes. Chest. 1984;85:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zimmermann CS, Carvalho CR, Silveira KR, et al. Comparison of two questionnaires which measure the health-related quality of life of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2007;40:179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. ATS statement: guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Laveneziana P, Albuquerque A, Aliverti A, et al. ERS statement on respiratory muscle testing at rest and during exercise. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Christe A, Peters AA, Drakopoulos D, et al. Computer-aided diagnosis of pulmonary fibrosis using deep learning and CT images. Invest Radiol. 2019;54:627–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Stauffer M, et al. The Insight ToolKit image registration framework. Front Neuroinform. 2014;8:44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rezatofighi H, Tsoi N, Gwak J, et al. Generalized intersection over union: a metric and a loss for bounding box regression. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2019.

- 27. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]