Abstract

Introduction

Short leukocyte telomere length (LTL) has become a hallmark characteristic of aging. Some, but not all evidence suggests that physical activity may play an important role in attenuating age-related diseases and may provide a protective effect for telomeres. The purpose of this study was to examine the association between physical activity and LTL in a national sample of U.S. adults from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).

Methods

NHANES data from the 1999–2002 (n = 6,503; 20–84 yrs) were used. 4 self-report questions related to movement based behaviors (MBB) were assessed. The 4 MBB included whether individuals participated in moderate-intensity physical activity (MPA), vigorous-intensity physical activity (VPA), walking/cycling for transportation, and muscle strengthening activities (MSA). A MBB index variable was created by summing the number of MBB each individual engaged in (range: 0–4).

Results

A clear dose-response relationship was observed between MBB and LTL; across the LTL tertiles, respectively, the mean number of MBB was 1.18, 1.44, and 1.54 (Ptrend<0.001). After adjustments (including age), and compared to those engaging in 0 MBB, those engaging in 1, 2, 3, and 4 MBB, respectively, had a 3% (p=0.84), 24% (p=0.02), 29% (p=0.04), and 52% (p=0.004) reduced odds of being in the lowest (vs. highest) tertile of LTL; MBB was not associated with being in the middle (vs. highest) tertile of LTL.

Conclusions

Greater engagement in MBB was associated with reduced odds of being in the lowest LTL tertile.

Keywords: Aging, epidemiology, physical activity, NHANES

INTRODUCTION

Shortened leukocyte telomere length (LTL) characterizes human aging (5,26,27). Potentially reflecting systemic oxidative stress and inflammation (10,51), short LTL is linked with various cardiometabolic diseases (2,4,13,18,19,21,46,47). Physical activity (PA) may help attenuate age-related diseases, as previous research (8,14,20,23–25,34,37,39,44,49) demonstrates that physically active adults have a longer mean LTL. However, some studies show no relationship (22,32,33,40,45,48,52) with others reporting an inverted U relationship (9,31,43) (review papers see Ludlow (29,30)).

Given these mixed findings, coupled with the fact that the majority of these studies were convenience-based samples or employed targeted populations (e.g., post-menopausal women) (29,30), here, we examine the association between PA and LTL in a national sample of U.S. adults. To improve our understanding of associations between PA and LTL, specific attention was focused on data from 4 movement-based behaviors (MBB). These include moderate-intensity PA (MPA), vigorous-intensity PA (VPA), walking and cycling for transportation, and muscle strengthening activities (MSA).

METHODS

Design and Participants

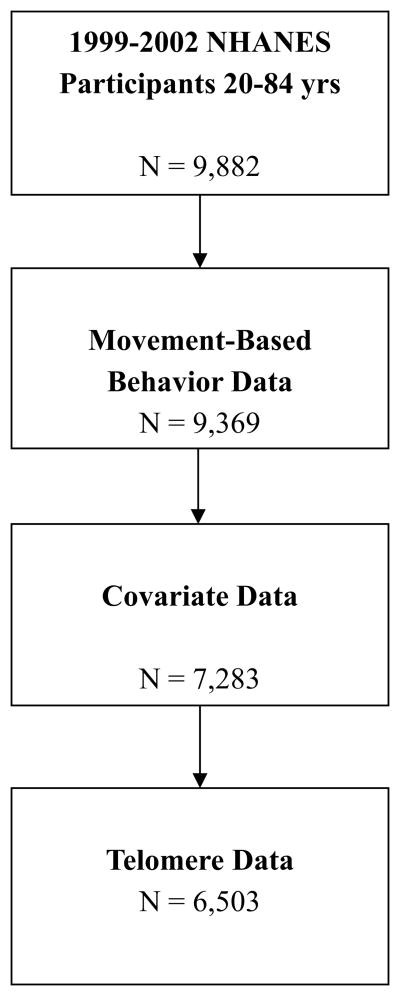

Data were extracted from the 1999–2002 NHANES (only cycles with LTL data at the time of this writing). Procedures were approved by the NCHS review board. Consent was obtained from all participants. Analyses are based on data from 6,503 adults (20–84 yrs) who provided complete data for the study variables. In the 1999–2002 NHANES cycles, 9,882 participants were between 20 and 84 years of age; after excluding those with missing MBB data, 9,369 remained; 7,283 remained after excluding those with missing covariate data; lastly, after excluding those with missing telomere data, 6,503 remained (resultant sample; Figure 1). When comparing the final analytic sample (N=6,503) to the 780 participants with missing telomere data (7,283–6,503=780), there were no differences in age, number of MBB, body mass index (BMI), C-reactive protein (CRP), or smoking (all p’s > 0.05); however, those that were excluded were more likely to be female (60% vs. 51.1%; p<0.001), less likely to be non-Hispanic white (38.1% vs. 50.4%, p<0.001), and had a lower poverty-to-income ratio (PIR) (2.56 vs. 2.71, p=0.01). These are unweighted estimates.

Figure 1.

Participant flow chart

Leukocyte Telomere Length

Detailed methodology of the NHANES procedures for assessing LTL has been previously reported (35). Briefly, DNA was extracted from whole blood and the LTL assay was performed using quantitative polymerase chain reaction to measure LTL relative to standard reference DNA (T/S ratio) (35). Each sample was assayed at least twice, and among samples with a T/S ratio within 7% variability, the average value was used; for samples with a variability greater than 7%, a third assay was run and in this case, the average of the two closest T/S values was used. Notably, in NHANES, telomere length in leukocytes was assessed. We acknowledge that LTL is not specific to skeletal muscle tissue; however, it may not be feasible to take muscle biopsies in large epidemiological studies. Previous work suggests that LTL is modestly (r=0.39) associated with muscle telomere length (1), which is in accordance with other studies (12), providing some justification for continued use of LTL measures, particularly in epidemiological studies.

Movement-Based Behaviors

In the 1999–2002 NHANES, 4 self-report items related to MBB were assessed, including PA participation during transportation and leisure time; notably, objective measures of PA (e.g., accelerometry) were not released until the 2003–2004 NHANES cycle. The 4 MBB included the degree of participation in MPA, VPA, walking/cycling for transportation, and MSA (yes/no responses).

For MPA: “Over the past 30 days, did you do moderate activities for at least 10 minutes that cause only light sweating or a slight to moderate increase in breathing or heart rate?”

For VPA: “Over the past 30 days, did you do vigorous activities for at least 10 minutes that caused heavy sweating, or large increases in breathing or heart rate?”

For walking/cycling for transportation: “Over the past 30 days, did you walk or bicycle as part of getting to and from work, or school, or to do errands?”

For MSA: “Over the past 30 days, did you do any physical activities specifically designed to strengthen your muscles such as lifting weights, push-ups or sit-ups?”

Movement-Based Behavior Index

A MBB index variable was created by summing the number of MBB each individual engaged in (range: 0–4).

Covariates

Covariates included age (continuous), age-squared (due to nonlinearity between age and LTL), gender, race-ethnicity, PIR, smoking status (smokes every day, some days, no longer smokes, and never smoked), measured BMI (kg/m2), and CRP (mg/dL).

Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using procedures from survey data using Stata (v.12). Polytomous regression was used to examine the odds of being in the two lower tertiles (6,53) (vs. upper tertile) of LTL based on the degree of engagement in MBB; those with a MBB index score of “0” served as the referent group.

RESULTS

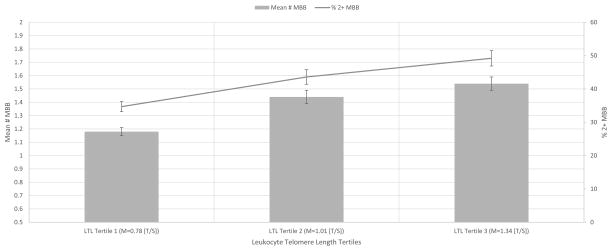

Table 1 displays the characteristics of the sample. The weighted mean number of MBB across the LTL tertiles, respectively, was 1.18, 1.44, and 1.54 (Table 1; Figure 2). The weighted proportion of participants with 2+ MBB across the LTL tertiles, respectively, were 34.7%, 43.6% and 49.2% (Figure 2). Table 2 displays the polytomous regression results. After adjustments (including age), and compared to those engaging in 0 MBB, those engaging in 1, 2, 3, and 4 MBB, respectively, had a 3% (p=0.84), 24% (p=0.02), 29% (p=0.04), and 52% (p=0.004) reduced odds of being in the lowest (vs. highest) tertile of LTL; MBB was not associated with being in the middle (vs. highest) tertile of LTL. When changing the referent group to the middle tertile (not shown in table), and compared those engaging in 0 MBB, those engaging in 1, 2, 3, and 4 MBB, respectively, had a 5% (p=0.60), 12% (p=0.40), 28% (p=0.02), and 56% (p=0.009) reduced odds of being in the lowest (vs. middle) tertile of LTL. Taken together, these findings suggest a dose response relationship between MBB and LTL; greater engagement in MBB was associated with a lower odds of being in lowest vs. highest LTL tertile and lowest vs. middle tertile.

Table 1.

Weighted characteristics of the analyzed sample, NHANES 1999–2002 (N=6503).

| LTL Tertile 1 (n=2168) | LTL Tertile 2 (n=2168) | LTL Tertile 3 (n=2167) | P-Value † | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leukocyte telomere length (T/S ratio) | 0.78 (0.77–0.79) | 1.01 (1.00–1.02) | 1.34 (1.31–1.36) | <0.001 |

| Moderate Physical Activity in past 30 days, % | ||||

| Yes | 48.3 (44.8–51.8) | 53.7 (49.3–58.1) | 48.7 (43.7–53.5) | 0.03 |

| Vigorous Physical Activity in past 30 days, % | ||||

| Yes | 28.7 (26.1–31.1) | 39.2 (34.8–43.5) | 45.0 (40.8–49.1) | <0.001 |

| Walked/Cycled in past 30 days, % | ||||

| Yes | 19.9 (17.6–22.2) | 23.7 (20.1–27.3) | 27.7 (23.8–31.5) | <0.001 |

| Strengthening activities in past 30 days, % | ||||

| Yes | 21.6 (18.2–25.0) | 27.6 (24.3–30.9) | 33.3 (29.9–36.6) | <0.001 |

| Mean # of Movement Behaviors | 1.18 (1.11–1.25) | 1.44 (1.32–1.56) | 1.54 (1.42–1.66) | <0.001 |

| Sum # Movement Behaviors, % | ||||

| 0 | 30.7 (27.0–34.3) | 24.8 (21.3–28.3) | 22.4 (19.7–25.2) | <0.001 |

| 1 | 34.6 (32.0–37.1) | 31.6 (29.3–33.8) | 28.4 (25.3–31.6) | |

| 2 | 21.8 (19.0–24.6) | 22.7 (20.4–25.1) | 26.1 (23.7–28.4) | |

| 3 | 10.9 (9.0–12.9) | 16.0 (13.5–18.5) | 17.8 (14.5–21.0) | |

| 4 | 1.8 (1.0–2.6) | 4.7 (3.0–6.2) | 5.1 (3.2–7.0) | |

| Age, yrs | 52.7 (51.4–54.0) | 44.6 (43.2–45.9) | 38.2 (36.8–39.5) | <0.001 |

| Gender, % | ||||

| Male | 51.7 (48.9–54.4) | 47.4 (44.5–50.4) | 49.0 (47.1–51.0) | 0.10 |

| Race-Ethnicity, % | ||||

| Mexican American | 6.7 (3.9–9.5) | 7.7 (5.7–9.8) | 6.9 (4.9–8.9) | 0.03 |

| Other Hispanic | 5.8 (1.2–10.5) | 5.6 (2.6–8.6) | 7.8 (4.4–11.2) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 76.4 (71.3–81.6) | 75.3 (71.2–79.4) | 68.6 (63.8–73.4) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 7.0 (4.9–9.1) | 7.4 (5.2–9.7) | 12.1 (9.1–15.1) | |

| Other | 3.7 (2.0–5.5) | 3.6 (2.5–4.8) | 4.4 (2.5–6.3) | |

| Smoking Status, % | ||||

| Every day | 19.7 (17.1–22.3) | 20.4 (17.3–23.5) | 21.8 (19.1–24.6) | <0.001 |

| Some days | 2.6 (1.8–3.3) | 3.4 (2.4–4.5) | 5.5 (4.0–6.9) | |

| No longer smoke | 30.9 (28.0–33.8) | 25.3 (22.3–28.4) | 19.7 (17.0–22.3) | |

| Never smoked | 46.6 (43.1–50.1) | 50.6 (47.5–53.8) | 52.9 (48.4–57.3) | |

| Body Mass Index, kg/m2 | 28.6 (28.2–29.0) | 28.0 (27.7–28.3) | 27.4 (26.9–27.8) | <0.001 |

| Poverty-to-Income ratio | 3.06 (2.8–3.2) | 3.14 (2.9–3.3) | 2.97 (2.7–3.2) | 0.38 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | 0.49 (0.44–0.54) | 0.39 (0.36–0.42) | 0.35 (0.31–0.39) | <0.001 |

Design-based likelihood ratio test used to determine statistical significance for the categorical variables. Linear regression used to determine statistical significance for the continuous variables by comparing tertile 3 vs. tertile 1.

Figure 2.

Weighted mean number of movement-based behaviors (MBB) and the weighted proportion of adults having 2+ MBB across leukocyte telomere length (LTL) tertiles (Mean (M) LTL across the LTL tertiles was 0.78, 1.01, and 1.34 T/S).

Table 2.

Weighted multivariable polytomous regression examining the odds of being in the two lower tertiles (vs. upper tertile) of leukocyte telomere length based on the degree of engagement in movement-based behaviors, NHANES 1999–2002 (N=6503).

| Tertile 1 vs. Tertile 3 | Tertile 2 vs. Tertile 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Movement Behaviors | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P |

| 1 vs. 0 | 0.97 | 0.78–1.22 | 0.84 | 1.02 | 0.86–1.21 | 0.73 |

| 2 vs. 0 | 0.76 | 0.61–0.96 | 0.02 | 0.86 | 0.70–1.07 | 0.18 |

| 3 vs. 0 | 0.71 | 0.52–0.98 | 0.04 | 0.98 | 0.70–1.37 | 0.92 |

| 4 vs. 0 | 0.48 | 0.29–0.78 | 0.004 | 1.08 | 0.73–1.60 | 0.67 |

| Covariates | ||||||

| Age, 1 yr older | 1.05 | 1.01–1.09 | 0.008 | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.004 |

| Age-squared | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.53 | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.38 |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female vs Male | 0.80 | 0.68–0.94 | 0.008 | 1.04 | 0.88–1.22 | 0.59 |

| Race-Ethnicity | ||||||

| Mexican American vs. white | 1.40 | 0.84–2.33 | 0.18 | 1.29 | 0.94–1.77 | 0.10 |

| Other Hispanic vs. white | 0.86 | 0.34–2.20 | 0.76 | 0.74 | 0.45–1.23 | 0.24 |

| Non-Hispanic black vs. white | 0.56 | 0.38–0.84 | 0.007 | 0.59 | 0.43–0.80 | 0.002 |

| Other vs. white | 0.98 | 0.56–1.71 | 0.96 | 0.84 | 0.52–1.36 | 0.48 |

| Smoking Status | ||||||

| Every day vs. never smoked | 1.16 | 0.95–1.40 | 0.11 | 1.03 | 0.84–1.27 | 0.70 |

| Some days vs. never smoked | 0.72 | 0.46–1.11 | 0.13 | 0.78 | 0.51–1.18 | 0.23 |

| No longer smoke vs. never smoked | 1.07 | 0.90–1.27 | 0.39 | 1.03 | 0.85–1.26 | 0.69 |

| Body Mass Index, 1 kg/m2 increase | 1.02 | 1.01–1.04 | 0.009 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.04 |

| Poverty-to-Income ratio, 1 unit increase | 0.98 | 0.89–1.08 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.94–1.05 | 0.96 |

| C-reactive protein, 1 mg/dL increase | 1.16 | 1.00–1.35 | 0.04 | 1.02 | 0.88–1.19 | 0.69 |

Given that some studies suggest a non-linear relationship between telomere length and morbidity (11,15), in addition to considering tertiles of LTL, further analyses examined the relationship between MBB and 5 quintiles of LTL; across these 5 quintiles, respectively, the mean LTL was 0.73, 0.88, 1.01, 1.14 and 1.44 – notably, the 90th and 95th percentiles for LTL in this sample were 1.37 and 1.50, respectively. The mean number of MBB across the 5 quintiles of LTL, respectively, were 1.15, 1.27, 1.46, 1.52 and 1.55. This observed monotonic relationship suggests that, in this sample, LTL had a linear, rather than an inverted U-shaped, association with mean MBB number.

Additional analyses (not shown in tabular format) were computed to see if age moderated the association between MBB and LTL. Three additional multivariable polytomous regression models were computed for those 20–39 yrs, 40–64 yrs, and 65–84 yrs. Results were not significant for the 20–39 and 65–84 yr-old age groups (data not shown); among those who were 40–64 yrs, and compared to those engaging in 0 MBB, those engaging in 1, 2, 3, and 4 behaviors, respectively, had a 15% (p=0.44), 32% (p=0.08), 42% (p=0.01), and 61% (p=0.03) reduced odds of being in the lowest (vs. highest) tertile of LTL.

Further, all 4 MBB were entered separately into a multivariable polytomous regression model to examine their potential independent associations. After adjustments, those engaging in VPA and walking/cycling for transportation, respectively, had a 25% (p=0.01) and 30% (p=0.004) lower odds of being in the lowest (vs. highest) LTL tertile; MPA (OR=1.13, p=0.15) and MSA (OR=0.92, p=0.50) were not independently associated with being the in the lowest (vs. highest) LTL tertile.

In addition to examining independent associations of the different MBB on LTL, it is of interest to examine whether MBB exclusivity (e.g., only engaging in MPA and not any of the 3 other MBB) is associated with LTL. Among the 6,503 participants, 386 engaged in only VPA (i.e., reporting engaging in VPA but not in MPA, MSA or walking for transportation), 1,057 engaged in only MPA, 176 engaged in only MSA and 417 engaged in only walking/cycling for transportation. Results for only VPA, MSA and walking/cycling for transportation were not statistically significant (data not shown). Interestingly, however, those who only engaged in MPA had a 36% (OR=1.36, p=0.01) and 25% (OR=1.25, p=0.06) increased odds, respectively, in being in the lowest and middle tertiles (vs. highest tertile) after adjustments. This is an unexpected finding, but this association, coupled with our observed finding of a dose-response association between MBB engagement and LTL, suggests that engaging in some MBB in isolation may not be favorable, but there may be a combined effect of attenuating the shortening of LTL when multiple MBB are engaged in regularly.

Lastly, given that some studies have demonstrated an inverted U relationship between PA and LTL (29,30), we attempted to examine whether such a relationship was observed for frequency of MSA; duration/frequency of MPA and VPA were not asked in the 1999–2002 NHANES cycles and the majority (76%) of participants did not walk/cycle for transportation so evaluating a dose-response relationship between walking/cycling for transportation and LTL was not possible. No dose-response relationship was observable for MSA; compared to those in the lowest MSA tertile (mean # of MSA in past 30 days: 5.6), and after adjustments in a linear regression, no association was observed between those in the middle (mean MSA 12.9; β=−0.02, p=0.13) and upper (mean MSA: 27.4; β=−0.002, p=0.88) MSA tertiles with LTL.

DISCUSSION

Using a national sample of U.S. adults, we observed a dose-response relationship between MBB engagement (i.e., # of MBB they engaged in) and lower LTL. The potential mechanisms to explain a PA-LTL relationship are not fully established. Among rodent models, several exercise-specific signaling mechanisms (e.g., TERT, IGF-1, eNOS, and AKT) have been associated with altered telomere biology (29,30), and thus, may play an important role in preserving telomere phenotype (30,49,50). Future work is needed to improve our understanding of the mechanisms underlying this potential relationship.

Importantly, the relationship between MBB and LTL was observed only among those 40–64 yrs, which suggests that, if confirmed by prospective and experimental work, this may be an important age-group in which targeted PA interventions should be developed, implemented and evaluated. The unexpected finding that those who only engaged in MPA had increased odds of being in the lowest and middle tertiles (vs. highest tertile) needs further investigation. It is possible that engaging in only MPA may result in an inadequate exercise stimulus to achieve exercise-induced LTL adaptations. The observed findings should be interpreted in the context of the study’s limitation, which include, for example, the cross-sectional design and an inability to fully tease out potential intensity/duration effects. Also, given that the excluded sample due to missing LTL data differed by gender, race-ethnicity and PIR when compared to the analytic sample, generalizability to these subpopulations may be limited.

Owing to the limitations of the MBB items, we were not able to determine the duration and frequency of most of the MBB items, but rather whether they engaged in the behavior or not. Previous research, however, suggests that there is likely a range in the amount of PA which provides health benefits without negatively affecting LTL (22,38,40,43). Data in very active adults suggest that if this range is exceeded, then PA may result in a detrimental effect on LTL (22,43). For example, high levels of PA may increase demand on the body to repair and regenerate, resulting in a shortening of LTL. This may explain why some studies don’t always find a dose-response relationship between the amount of PA and LTL (22,32,33,40,45,48,52). Our findings suggest that engaging in more MBB is associated with reduced odds of being in the lowest LTL tertile, suggesting that engaging in multiple MBB may have a combined effect in minimizing LTL shortening.

Future epidemiological studies examining the extent to which MBB duration and frequency influence LTL are needed. Further, future work examining tissue and cell-specific telomere adaptations from exercise is warranted (30). Given the protective effects of telomerase activity (42), future epidemiological studies examining the effects of MBB on telomerase activity is warranted. Due to the combined effects of multiple health-enhancing behaviors on health (28,41), as well as LTL (16,17,36), future epidemiological work examining the additive and additive interaction effects of multiple health behaviors on LTL is warranted. Lastly, given that it is not entirely certain whether LTL is a cause or consequence of morbidity (e.g., cardiovascular disease), future longitudinal mediational models examining whether LTL mediates the relationship between MBB and morbidity/mortality is warranted. However, prospective studies are starting to emerge showing that shorter LTL is predictive of premature mortality from an increased risk of various chronic diseases (e.g., cardiovascular disease) (7), but several issues (e.g., methodology used to assess LTL and potential regression to the mean) need to be carefully considered when examining and interpreting the prospective interrelationships between PA, LTL, and morbidity/mortality (3).

Acknowledgments

No funding was used to prepare this manuscript.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The results of this study do not constitute endorsement by the American College of Sports Medicine.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding: The authors declares no conflicts of interest and no funding was used to prepare this manuscript.

References

- 1.Ahmad S, Heraclides A, Sun Q, et al. Telomere length in blood and skeletal muscle in relation to measures of glycaemia and insulinaemia. Diabet Med. 2012;29:e377–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aviv H, Khan MY, Skurnick J, et al. Age dependent aneuploidy and telomere length of the human vascular endothelium. Atherosclerosis. 2001;159:281–7. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(01)00506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bendix L, Thinggaard M, Fenger M, et al. Longitudinal changes in leukocyte telomere length and mortality in humans. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69:231–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glt153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benetos A, Gardner JP, Zureik M, et al. Short telomeres are associated with increased carotid atherosclerosis in hypertensive subjects. Hypertension. 2004;43:182–5. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000113081.42868.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blackburn EH. Telomere states and cell fates. Nature. 2000;408:53–6. doi: 10.1038/35040500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brouilette SW, Moore JS, McMahon AD, et al. Telomere length, risk of coronary heart disease, and statin treatment in the West of Scotland Primary Prevention Study: a nested case-control study. Lancet. 2007;369:107–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60071-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cawthon RM, Smith KR, O’Brien E, et al. Association between telomere length in blood and mortality in people aged 60 years or older. Lancet. 2003;361:393–5. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12384-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cherkas LF, Hunkin JL, Kato BS, et al. The association between physical activity in leisure time and leukocyte telomere length. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:154–8. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2007.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collins M, Renault V, Grobler LA, et al. Athletes with exercise-associated fatigue have abnormally short muscle DNA telomeres. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35:1524–8. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000084522.14168.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Correia-Melo C, Hewitt G, Passos JF. Telomeres, oxidative stress and inflammatory factors: partners in cellular senescence? Longev Healthspan. 2014;3:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-2395-3-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cui Y, Cai Q, Qu S, et al. Association of leukocyte telomere length with colorectal cancer risk: nested case-control findings from the Shanghai Women’s Health Study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1807–13. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daniali L, Benetos A, Susser E, et al. Telomeres shorten at equivalent rates in somatic tissues of adults. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1597. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Demissie S, Levy D, Benjamin EJ, et al. Insulin resistance, oxidative stress, hypertension, and leukocyte telomere length in men from the Framingham Heart Study. Aging Cell. 2006;5:325–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2006.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du M, Prescott J, Kraft P, et al. Physical activity, sedentary behavior, and leukocyte telomere length in women. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;175:414–22. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elks CE, Scott RA. The long and short of telomere length and diabetes. Diabetes. 2014;63:65–7. doi: 10.2337/db13-1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Falus A, Marton I, Borbenyi E, et al. The 2009 Nobel Prize in Medicine and its surprising message: lifestyle is associated with telomerase activity. Orv Hetil. 2010;151:965–70. doi: 10.1556/OH.2010.28899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Falus A, Marton I, Borbenyi E, et al. A challenging epigenetic message: telomerase activity is associated with complex changes in lifestyle. Cell Biol Int. 2011;35:1079–83. doi: 10.1042/CBI20110046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Gardner JP, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and cardiovascular disease in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:14–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fitzpatrick AL, Kronmal RA, Kimura M, et al. Leukocyte telomere length and mortality in the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:421–9. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glq224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garland SN, Johnson B, Palmer C, et al. Physical activity and telomere length in early stage breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:413. doi: 10.1186/s13058-014-0413-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jeanclos E, Schork NJ, Kyvik KO, et al. Telomere length inversely correlates with pulse pressure and is highly familial. Hypertension. 2000;36:195–200. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kadi F, Ponsot E, Piehl-Aulin K, et al. The effects of regular strength training on telomere length in human skeletal muscle. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:82–7. doi: 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181596695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim JH, Ko JH, Lee DC, et al. Habitual physical exercise has beneficial effects on telomere length in postmenopausal women. Menopause. 2012;19:1109–15. doi: 10.1097/gme.0b013e3182503e97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krauss J, Farzaneh-Far R, Puterman E, et al. Physical fitness and telomere length in patients with coronary heart disease: findings from the Heart and Soul Study. PLoS One. 2011;6:e26983. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaRocca TJ, Seals DR, Pierce GL. Leukocyte telomere length is preserved with aging in endurance exercise-trained adults and related to maximal aerobic capacity. Mech Ageing Dev. 2010;131:165–7. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin J, Epel E, Blackburn E. Telomeres and lifestyle factors: roles in cellular aging. Mutat Res. 2012;730:85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez-Otin C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, et al. The hallmarks of aging. Cell. 2013;153:1194–217. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loprinzi PD, Smit E, Mahoney S. Physical activity and dietary behavior in US adults and their combined influence on health. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:190–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ludlow AT, Ludlow LW, Roth SM. Do telomeres adapt to physiological stress? Exploring the effect of exercise on telomere length and telomere-related proteins. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:601368. doi: 10.1155/2013/601368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludlow AT, Roth SM. Physical activity and telomere biology: exploring the link with aging-related disease prevention. J Aging Res. 2011;2011:790378. doi: 10.4061/2011/790378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ludlow AT, Zimmerman JB, Witkowski S, et al. Relationship between physical activity level, telomere length, and telomerase activity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40:1764–71. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c92aa. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason C, Risques RA, Xiao L, et al. Independent and combined effects of dietary weight loss and exercise on leukocyte telomere length in postmenopausal women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:E549–54. doi: 10.1002/oby.20509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathur S, Ardestani A, Parker B, et al. Telomere length and cardiorespiratory fitness in marathon runners. J Investig Med. 2013;61:613–5. doi: 10.2310/JIM.0b013e3182814cc2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mirabello L, Huang WY, Wong JY, et al. The association between leukocyte telomere length and cigarette smoking, dietary and physical variables, and risk of prostate cancer. Aging Cell. 2009;8:405–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Needham BL, Adler N, Gregorich S, et al. Socioeconomic status, health behavior, and leukocyte telomere length in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999–2002. Soc Sci Med. 2013;85:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ornish D, Lin J, Chan JM, et al. Effect of comprehensive lifestyle changes on telomerase activity and telomere length in men with biopsy-proven low-risk prostate cancer: 5-year follow-up of a descriptive pilot study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:1112–20. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70366-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Osthus IB, Sgura A, Berardinelli F, et al. Telomere length and long-term endurance exercise: does exercise training affect biological age? A pilot study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e52769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponsot E, Lexell J, Kadi F. Skeletal muscle telomere length is not impaired in healthy physically active old women and men. Muscle Nerve. 2008;37:467–72. doi: 10.1002/mus.20964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Puterman E, Lin J, Blackburn E, et al. The power of exercise: buffering the effect of chronic stress on telomere length. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rae DE, Vignaud A, Butler-Browne GS, et al. Skeletal muscle telomere length in healthy, experienced, endurance runners. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2010;109:323–30. doi: 10.1007/s00421-010-1353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sagner M, Katz D, Egger G, et al. Lifestyle medicine potential for reversing a world of chronic disease epidemics: from cell to community. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:1289–92. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanchis-Gomar F, Lucia A. Acute myocardial infarction: ‘telomerasing’ for cardioprotection. Trends Mol Med. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2015.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savela S, Saijonmaa O, Strandberg TE, et al. Physical activity in midlife and telomere length measured in old age. Exp Gerontol. 2013;48:81–4. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simpson RJ, Cosgrove C, Chee MM, et al. Senescent phenotypes and telomere lengths of peripheral blood T-cells mobilized by acute exercise in humans. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2010;16:40–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Song Z, von Figura G, Liu Y, et al. Lifestyle impacts on the aging-associated expression of biomarkers of DNA damage and telomere dysfunction in human blood. Aging Cell. 2010;9:607–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2010.00583.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terai M, Izumiyama-Shimomura N, Aida J, et al. Association of telomere shortening in myocardium with heart weight gain and cause of death. Sci Rep. 2013;3:2401. doi: 10.1038/srep02401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasan RS, Demissie S, Kimura M, et al. Association of leukocyte telomere length with echocardiographic left ventricular mass: the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2009;120:1195–202. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.853895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weischer M, Bojesen SE, Nordestgaard BG. Telomere shortening unrelated to smoking, body weight, physical activity, and alcohol intake: 4,576 general population individuals with repeat measurements 10 years apart. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004191. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Werner C, Furster T, Widmann T, et al. Physical exercise prevents cellular senescence in circulating leukocytes and in the vessel wall. Circulation. 2009;120:2438–47. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.861005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Werner C, Hanhoun M, Widmann T, et al. Effects of physical exercise on myocardial telomere-regulating proteins, survival pathways, and apoptosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:470–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wolkowitz OM, Mellon SH, Epel ES, et al. Leukocyte telomere length in major depression: correlations with chronicity, inflammation and oxidative stress--preliminary findings. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17837. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woo J, Tang N, Leung J. No association between physical activity and telomere length in an elderly Chinese population 65 years and older. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2163–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.19.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ye S, Shaffer JA, Kang MS, et al. Relation between leukocyte telomere length and incident coronary heart disease events (from the 1995 Canadian Nova Scotia Health Survey) Am J Cardiol. 2013;111:962–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2012.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]