Abstract

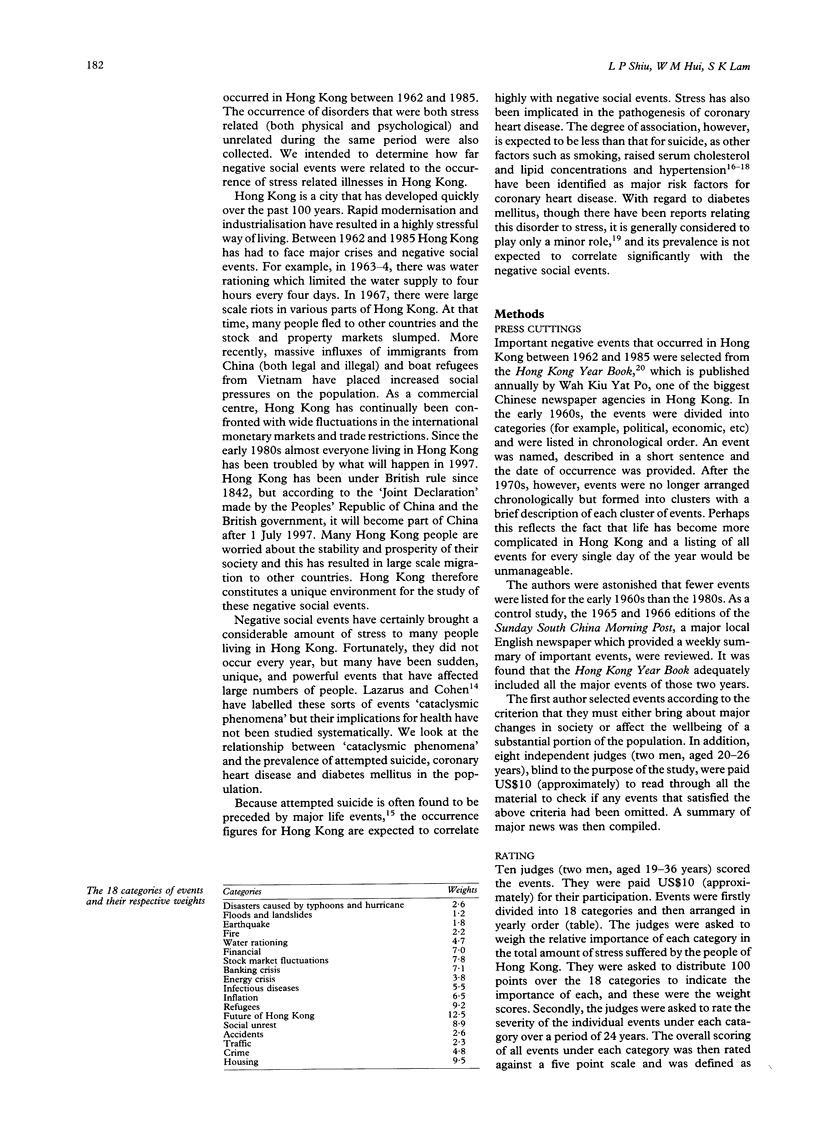

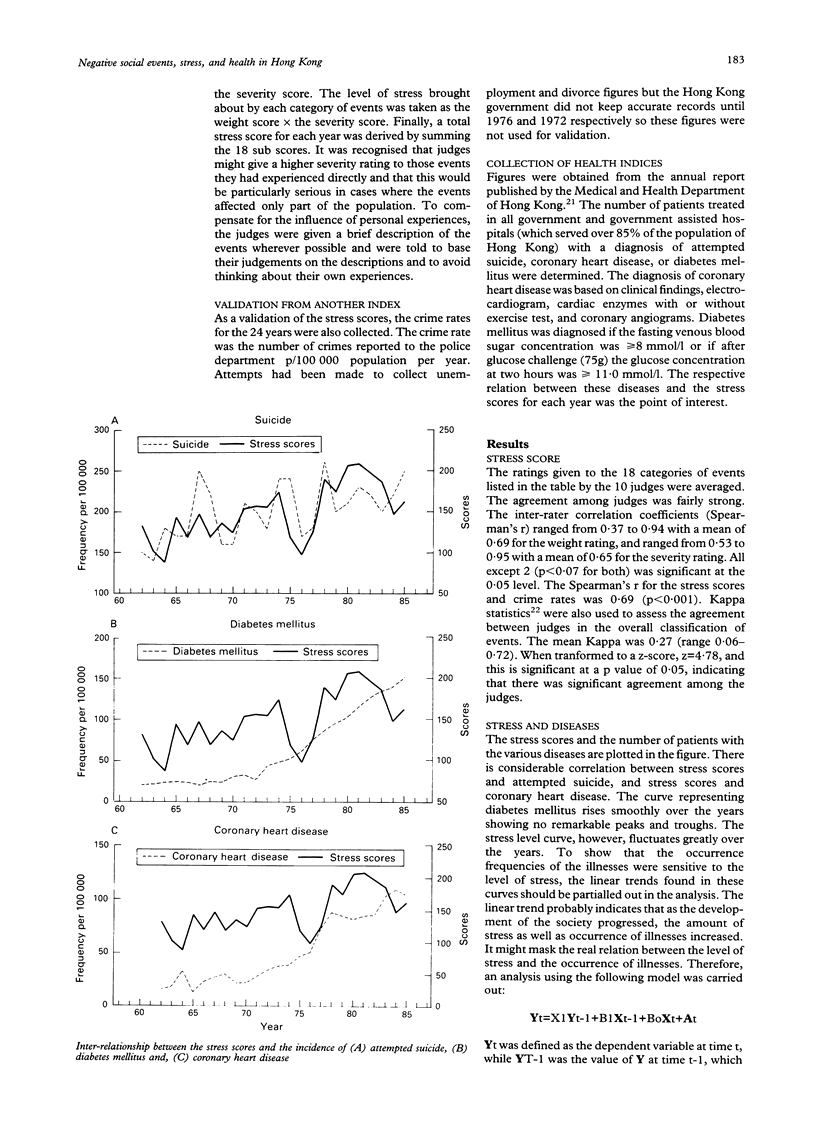

STUDY OBJECTIVE--To investigate the association, if any, between negative social events and physical illness. DESIGN--Comparison of major social events and indices of disease. SETTING-Hong Kong, 1962 to 1985. SUBJECTS--Patients treated in hospital for attempted suicide, coronary heart disease, and diabetes mellitus. MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS--Major events were selected from the annual Hong Kong Year Book, and grouped in one of 18 categories by a panel of 10 assessors. Weights were assigned to each category according the likely stress produced. Individual events were then scored and multiplied by the category weights to produce an overall stress score from which a total stress score for each year was derived. Annual stress scores were then compared with hospital attendance rates for the three medical conditions. CONCLUSIONS--The study has shown that: (1) the stress induced in the community by major negative social events in Hong Kong had been increasing; and (2) this stress is associated with attempted suicide but not with diabetes mellitus or coronary heart disease.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Antoni M. H. Temporal relationship between life events and two illness measures: a cross-lagged panel analysis. J Human Stress. 1985 Spring;11(1):21–26. doi: 10.1080/0097840X.1985.9936734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum A., Gatchel R. J., Schaeffer M. A. Emotional, behavioral, and physiological effects of chronic stress at Three Mile Island. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983 Aug;51(4):565–572. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.4.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. H., Mooney A. Economic change and sex-specific cardiovascular mortality in Britain 1955-1976. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(4):431–442. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90051-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. H., Mooney A. Unemployment and health in the context of economic change. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17(16):1125–1138. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner M. H. Mortality and the national economy. A review, and the experience of England and Wales, 1936--76. Lancet. 1979 Sep 15;2(8142):568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson L. A., Böttiger L. E., Ahfeldt P. E. Risk factors for myocardial infarction in the Stockholm prospective study. A 14-year follow-up focussing on the role of plasma triglycerides and cholesterol. Acta Med Scand. 1979;206(5):351–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer T., Hetzel B. S. A comparison of trends of coronary heart disease mortality in Australia, USA and England and Wales with reference to three major risk factors-hypertension, cigarette smoking and diet. Int J Epidemiol. 1980 Mar;9(1):65–71. doi: 10.1093/ije/9.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M., Walker P., Green J. L., Weingarden K. Life events stress and psychosocial factors in men with peptic ulcer disease. A multidimensional case-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1986 Dec;91(6):1370–1379. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes T. H., Rahe R. H. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967 Aug;11(2):213–218. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins C. D. Medical progress. Recent evidence supporting psychologic and social risk factors for coronary disease (first of two parts). N Engl J Med. 1976 Apr 29;294(18):987–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197604292941806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasl S. V. Mortality and the business cycle: some questions about research strategies when utilizing macro-social and ecological data. Am J Public Health. 1979 Aug;69(8):784–788. doi: 10.2105/ajph.69.8.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz D. S., Grunberg N. E., Baum A. Health psychology. Annu Rev Psychol. 1985;36:349–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ps.36.020185.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff A., Lester T. W., Addington W. W. Tuberculosis. A chemotherapeutic triumph but a persistent socioeconomic problem. Arch Intern Med. 1979 Dec;139(12):1375–1377. doi: 10.1001/archinte.139.12.1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo W. H., Leung T. M. Suicide in Hong Kong. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1985 Sep;19(3):287–292. doi: 10.3109/00048678509158834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paykel E. S., Prusoff B. A., Myers J. K. Suicide attempts and recent life events. A controlled comparison. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1975 Mar;32(3):327–333. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1975.01760210061003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin J. G., Struening E. L. Live events, stress, and illness. Science. 1976 Dec 3;194(4269):1013–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.790570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenman R. H., Brand R. J., Jenkins D., Friedman M., Straus R., Wurm M. Coronary heart disease in Western Collaborative Group Study. Final follow-up experience of 8 1/2 years. JAMA. 1975 Aug 25;233(8):872–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sever P. S., Poulter N. R. A hypothesis for the pathogenesis of essential hypertension: the initiating factors. J Hypertens Suppl. 1989 Feb;7(1):S9–12. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198902001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater J., Depue R. A. The contribution of environmental events and social support to serious suicide attempts in primary depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1981 Aug;90(4):275–285. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.90.4.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]