Abstract

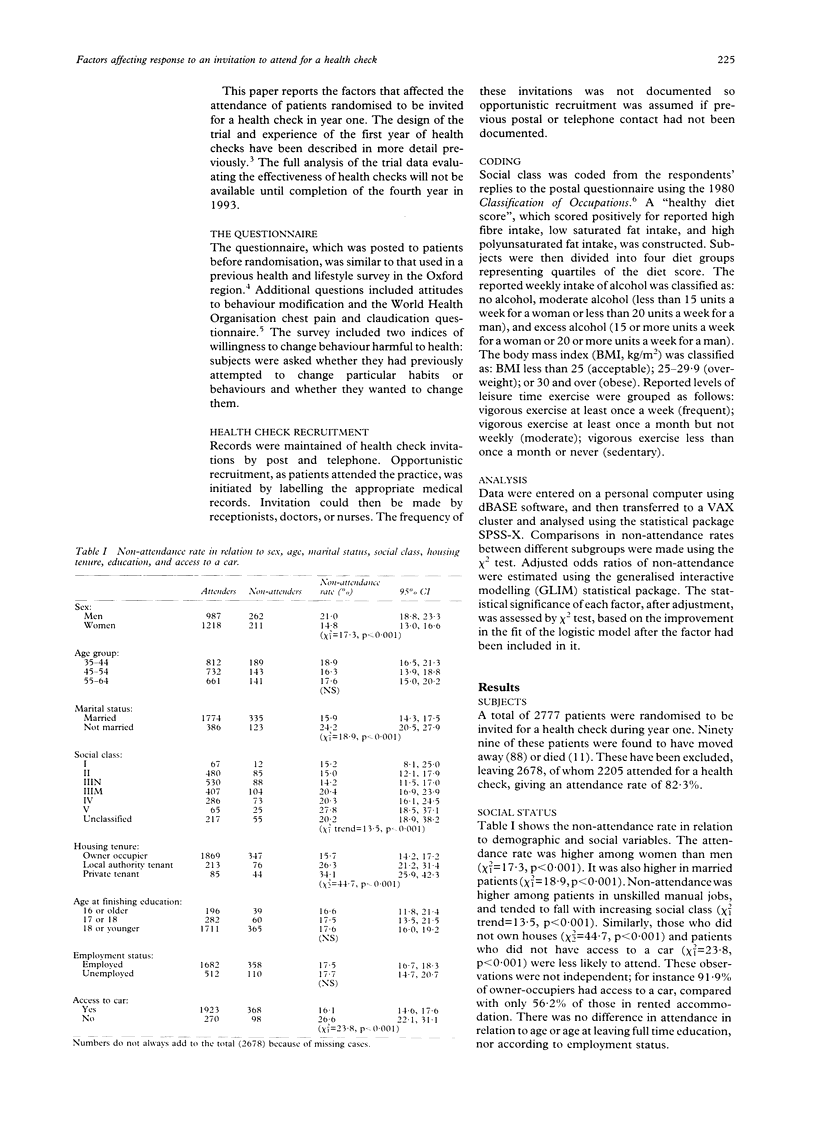

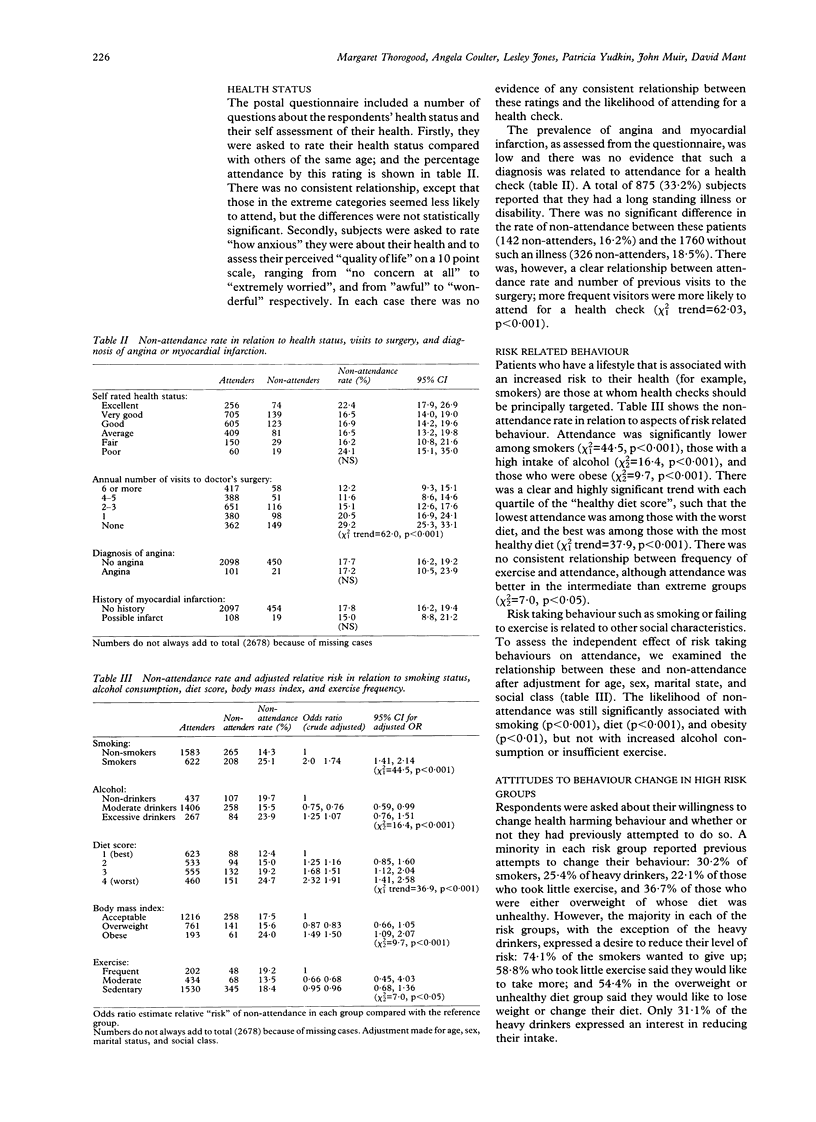

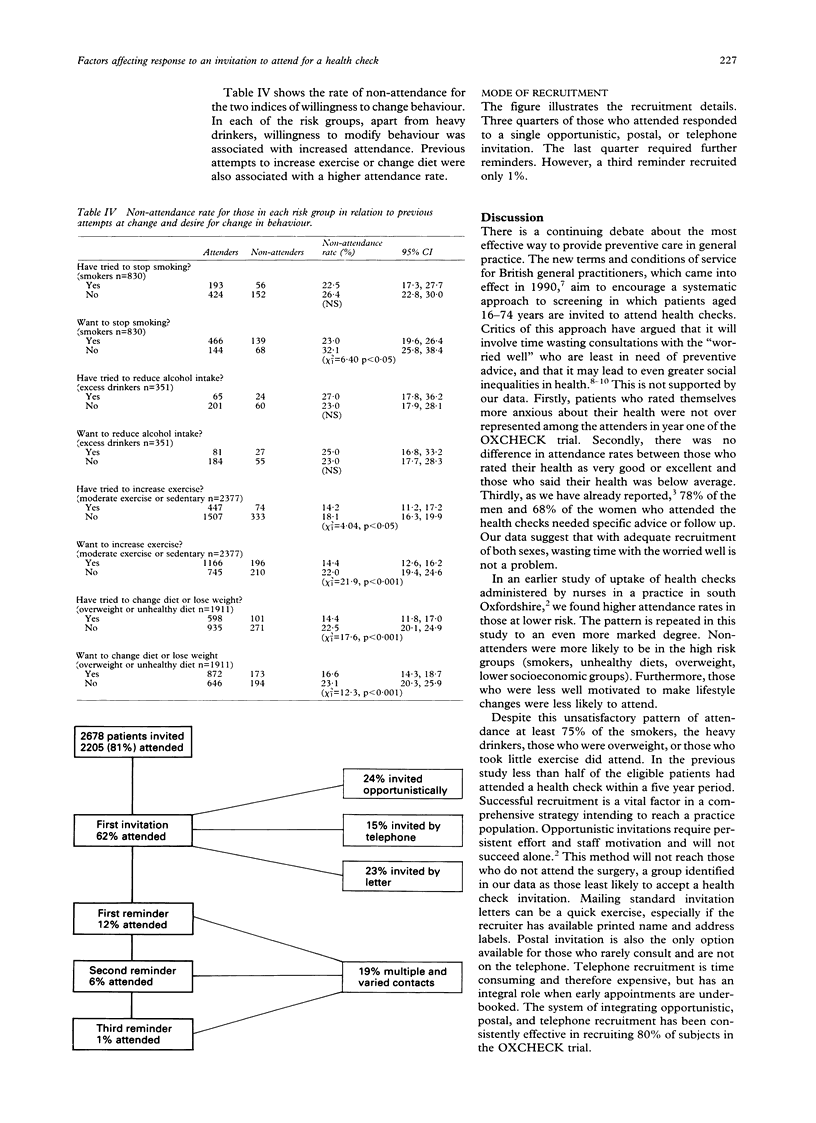

OBJECTIVE--To describe the characteristics of general practice patients who fail to respond to an invitation to attend for a health check, in relation to demographic variables, risk factor status, health status, and attitudes to behaviour modification. DESIGN--Postal questionnaire before invitation to attend a health check and subsequent record of attendance. SETTING--Five urban general practices in Bedfordshire, UK. SUBJECTS--A total of 2678 patients aged 35-64 years were invited for a health check in 1989-90. RESULTS--The number of patients who did not attend was low overall but was higher among men than women (21 v 15%, p < 0.001), and in unmarried than married patients (24 v 16%, p < 0.001). Failure to attend was also higher among people in manual than in non-manual occupations (21 v 15%, p < 0.001), in people living in rented accommodation than in homeowners (29 v 16%, p < 0.001), and in those without access to a car than in car users (27 v 16%, p < 0.001). There was no difference in non-attendance rate according to age at completion of full time education. After adjustment for age, sex, marital state, and social class, the odds ratio for non-attendance was 1.74 (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.41, 2.14) for smokers; 1.07 (95% CI 0.76, 1.51) for heavy drinkers; 1.91 (95% CI 1.41, 2.58) for those with a less healthy diet; and 1.50 (95% CI 1.09, 2.07) for those who were obese. Patients who had visited their general practice more frequently and those who indicated a willingness to change their behaviour were significantly more likely to attend the health check. CONCLUSIONS--Health check attendance was lowest among patients who rarely attended the surgery and those who reported higher risk behaviour. Attendance was not, however, confined to the 'worried well'. Equal numbers of those with and without chest pain attended, as did at least three quarters of those in each risk group. This high rate of attendance reflects the time and effort invested in systematic recruitment. The development of a robust recruiting strategy is essential if substantial numbers, and particularly those at highest risk, are to be reached.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Coulter A. Lifestyles and social class: implications for primary care. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1987 Dec;37(305):533–536. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullard E., Fowler G., Gray M. Promoting prevention in primary care: controlled trial of low technology, low cost approach. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987 Apr 25;294(6579):1080–1082. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6579.1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart J. T., Thomas C., Gibbons B., Edwards C., Hart M., Jones J., Jones M., Walton P. Twenty five years of case finding and audit in a socially deprived community. BMJ. 1991 Jun 22;302(6791):1509–1513. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6791.1509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh G. N., Channing D. M. Narrowing the health gap between a deprived and an endowed community. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Jan 16;296(6616):173–176. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6616.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pill R., French J., Harding K., Stott N. Invitation to attend a health check in a general practice setting: comparison of attenders and non-attenders. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1988 Feb;38(307):53–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waller D., Agass M., Mant D., Coulter A., Fuller A., Jones L. Health checks in general practice: another example of inverse care? BMJ. 1990 Apr 28;300(6732):1115–1118. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6732.1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]