Abstract

Objective

Stigma is a common problem among patients having breast cancer. However, the concept of stigma is vague and not specifically described or clearly defined in the literature. The lack of description or definition has further limited stigma research among patients having breast cancer. Therefore, this study aimed to clarify and analyze the concept of stigma in patients with breast cancer.

Methods

Walker and Avant's concept analysis method was applied to analyze the connotation of stigma in patients with breast cancer. PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CNKI, Wanfang, VIP, and SinoMed databases were searched from inception until May 31, 2023.

Results

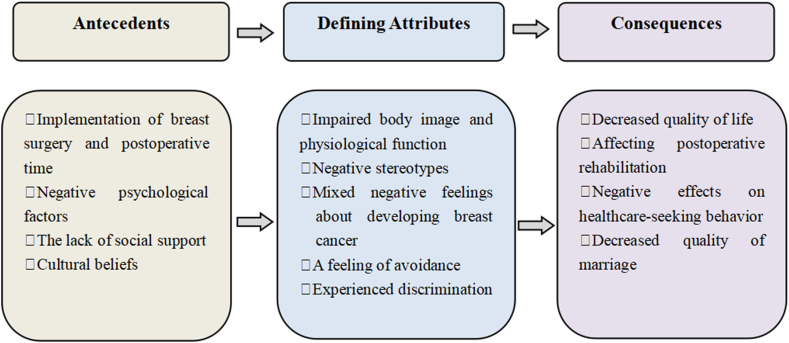

Five stigma-related attributes of patients having breast cancer were identified: (1) impaired body image and physiological function; (2) negative stereotypes; (3) mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer; (4) a feeling of avoidance; (5) experienced discrimination. Antecedents included the implementation of breast surgery and postoperative time, negative psychological factors, lack of social support, and cultural beliefs. This stigma among patients having breast cancer had significant negative effects on their quality of individual life and marriage, postoperative rehabilitation, and healthcare-seeking behavior.

Conclusions

The concept analysis results clarified the concept of stigma in patients with breast cancer and provided theoretical guidance for the development of the conceptual model of stigma in these patients. What is more, it offered a theoretical basis for future studies related to the development of stigma assessment tools for breast cancer patients and for devising nursing intervention strategies.

Keywords: Breast cancer, Stigma, Concept analysis, Nursing

Introduction

According to the Global Cancer Statistics 2020, the incidence rate of female breast cancer has increased swiftly in recent years, with breast cancer becoming the leading contributor to the global cancer incidence rate in 2020.1 The advancement of medical technology has resulted in the prolongation of the survival of breast cancer patients (BCPs), with the 5- and 10-year overall survival rates being 92.5% and 83.0%, respectively.2

However, the disease itself and treatment have made BCPs undergo various physiological–psychological–social problems. Surgery and other treatment could result in breast loss, surgical scar, hair loss, menopausal-like syndrome, and osteoporosis.3, 4, 5, 6 For example, breast loss damages women's external image of beauty. Besides, the destruction of reproductive capacity by treatment for breast cancer affects women's self-identity in society. BCPs also face discrimination from the public because of their illness, such as experiencing exclusion, alienation, and work discrimination. These problems induce BCPs to develop a strong sense of stigma, which further creates major obstacles in their psychologies, emotions, and personalities.7 Approximately 76.7% and 8.7% of the BCPs experienced moderate and high levels of stigma,8 which affected their postoperative rehabilitation, and reduced their quality of individual life and marriage.9

Stigma was derived from the Greek word “stizein”, which meant tattoo and informed others by marking them on slaves or traitors. With the gradual deepening of the study in stigma, researchers found that stigma existed in patients with mental illness and AIDS and began to conduct more in-depth studies of stigma in mental illness and AIDS.10,11 In recent years, due to the increasing incidence of breast cancer, the destruction of treatment methods and the emphasis on mental health construction, more and more researchers have paid attention to the stigma of BCPs and made preliminary study.7,9,12 Most of the studies focused on the exploration of influencing factors and the investigations of the current status, while the research on the concept of stigma in BCPs was relatively few.8,9 To the best of our knowledge, yet no unified or accurate definition is evident at home and abroad.13,14 The definition of stigma among BCPs in relevant literature was mostly developed on the concept of stigma, which was a general and vague concept, lacking a systematic analysis of the concept, and its occurrence and development process were still unclear.12,15 Besides, the differences and connections between stigma in BCPs and stigma in other diseases are still uncomprehending.16 So we could not identify or distinguish the attributes, antecedents, and consequences of stigma in BCPs, which caused us to fail to accurately recognize stigma characteristics in BCPs.

The aim of this study was to conduct a concept analysis of stigma in BCPs to provide a greater understanding of this phenomenon in BCPs and further develop a operational definition of the concept, identifying its attributes, antecedents, and consequences. Better identification of stigma in BCPs is critical to improving clinical care and health outcomes. It is beneficial to identify the stigma characteristics of BCPs in time and offer new insights into the construction of stigma intervention for BCPs to reduce the level of stigma. In addition, it can also provide a useful basis for the development and evaluation of stigma scales in BCPs to accurately measure the level of stigma in BCPs.

Methods

In this study, we analyzed the concept of stigma in BCPs by adopting Walker and Avant's concept analysis method,17 which consists of the following 8 steps: (1) select a concept; (2) determine the aims or purposes of analysis; (3) identify all applications of the concept; (4) determine the defining attributes of the concept; (5) identify a model case; (6) identify or construct borderline, related and contrary cases; (7) determine antecedents and consequences; (8) define empirical referents. Walker and Avant's concept analysis is the most common method of concept analysis, which is systematic and with clear and explicit steps specified in the analysis. This process contributes to clarifying the prevalent and ambiguous concepts and distinguishing between the defining and irrelevant attributes of a concept; hence, the researcher could elicit its operational definition.17

Literature search and data analysis

A search of electronic databases was conducted by using PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, CNKI(China National Knowledge Infrastructure), Wanfang (Wanfang Data in China), VIP (China Science and Technology Journal Database), and SinoMed (Chinese Biomedical Literature Database) from the inception of databases until May 31, 2023. The literature search was conducted by using a combination of MeSH terms and free-text terms, as given below: “breast neoplasm” OR “breast cancer” OR “breast tumor” OR “breast carcinoma” OR “breast malignancy”, “stigma” OR “social stigma” OR “shame”. We also conducted a manual search by examining the reference lists to identify the additional literature that could be included. The inclusion criteria for the literature were as follows: (1) the object of study was a female BCP; (2) the main content of research was the stigma of BCP, which involved the concept contents, attributes, antecedents, consequences, and assessment tools of stigma in BCPs. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) unoriginal research (eg, review or commentary); (2) non-Chinese and English literature; (3) unavailability of full-text literature. The literature screening and analysis were conducted independently by two reviewers in accordance with the inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria. If they did not reach an agreement after discussion, a third person was consulted to make a comprehensive judgment.

Search outcome

In total, 1212 studies (443 in Chinese and 769 in English) were identified. All literature was imported into Endnote, 798 studies remained after removing the duplicates. Subsequently, a manual search was conducted by examining the reference lists and 2 additional English studies were included. 162 studies were left after screening the titles and abstracts of the articles, and 36 studies were included after reading the full text, which included 19 Chinese studies and 17 English studies. Overall, 36 studies were included in this concept analysis. The flow diagram of the literature search is depicted in Fig. 1. Each paper we included would be analyzed to extract antecedents, attributes, and consequences associated with breast cancer stigma. A summary of the studies included and their main features are presented in Table 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of literature.

Table 1.

Main characteristics of the studies identified.

| No. | Author (year) | Defining attributes | Antecedents | Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Wang S (2015) | Negative consciousness; discrimination; exclusion | Psychological factors; social support; history of chronic diseases | Decreased quality of life; hindering rehabilitation |

| 2 | Xie X (2020) | Social discrimination; social isolation; shame; impaired body image | Surgical method; social support | Affecting disease treatment; decreased quality of life |

| 3 | Zheng XN et al (2014) | Concealment of the disease; depression; self-abasement; shame; resistance | Social support | Decreased quality of life; hindering rehabilitation |

| 4 | Li YF et al (2017) | Body changes; feeling more different experiences; fear of illness disclosure; | Surgical method | Decreased quality of life; affecting rehabilitation |

| 5 | Zheng CX (2020) | Concealment the experience of disease; depression; shame; self-accusation; low self-esteem | Surgical method; postoperative time; self-concealment; future view of the quality of life | Decreased quality of life; affecting prognosis |

| 6 | Zhao YQ (2022) | Anxiety; choosing to escape; fright; self-abasement; lacking of self-identification; social withdrawal; concealment of the disease; paying too much attention to others' thoughts | Type of operation | Hindering rehabilitation |

| 7 | Zheng CX et al (2018) | Social discrimination; body image changes | Type of operation; postoperative time | Decreased quality of life; affecting rehabilitation; |

| 8 | Chen Y et al (2020) | Negative psychological experience; impaired self-image | Surgical method | Affecting physical and mental health |

| 9 | Hu LL et al (2022) | Body image changes | Postoperative time | Hindering the disease recovery; affecting daily life |

| 10 | Xiao HM et al (2021) | Body changes; negative feeling of stigma; discrimination; inequality | Surgical method | Hindering healthcare-seeking behavior |

| 11 | He DM et al (2020) | Destroying role self-identity; self-negative marks; shame; discrimination; sensitivity; fragility; social avoidance | Social support | Affecting the physical and mental health; hindering healthcare-seeking behavior; lower marriage expectations |

| 12 | Kong RH et al (2017) | The inner feeling of shame | Postoperative time; surgical method | Decreased quality of life; hindering rehabilitation |

| 13 | Wei Y et al (2020) | Impaired body image; feeling discriminated; | Coping style | Affecting the mental state; hindering postoperative rehabilitation |

| 14 | Li YF (2017) | Impaired physical integrity; destroying the unique symbols of women; social exclusion; discrimination; stigma; hiding symptoms; avoidance | Social support; surgical method | Affecting engagement in treatment and nursing |

| 15 | Kong RH (2015) | Avoiding intimate behavior; concealing the damaged body; low self-esteem; self-isolation; social exclusion; distress; lower self-image level; estrangement; avoiding disclosure | Postoperative time; level of self-esteem; social support; couple attitude; surgical method | Decreased quality of life |

| 16 | He DM (2020) | Social anxiety disorder; sexual dysfunction; self-image disorder; anxiety; disappointment; fright; discrimination; self-accusation; isolation | Surgical method; postoperative time; coping style; personality | Sexual dysfunction; decreased quality of life; hindering healthcare-seeking behavior |

| 17 | Bai H (2019) | Shame; loss of female characteristics; self-doubt; self-denial; estrangement; exclusion; work discrimination; social withdrawal | Family support; cultural belief | Decreased quality of life |

| 18 | Solikhah S et al (2020) | Feelings of fear; shame; stereotypes of culture and beliefs; concealment and confidentiality | Support of family and friends; financial barriers | Delaying breast cancer screening behavior |

| 19 | Suwankhong D et al (2016) | Fatigue; changes in body appearance; social avoidance; self-isolation; sadness; shame; loneliness; hiding operative site; avoiding talking about their condition; embarrassment; decreased sexual function; stereotypes | Type of operation | Decreased quality of life; destroying the sexual relationships of couples |

| 20 | Sprung BR et al (2011) | Concealment of the disease; misery; fear; depression | Spousal support | Marriage dissatisfaction |

| 21 | Laza-Vásquez C et al (2021) | Misery; impaired image; concealment of the disease; hiding their impaired body; decreased sexual function | Not mentioned | Destroying sex life |

| 22 | Warmoth K et al (2017) | Embarrassment; shame; barriers to expressing emotions; concealment of breast cancer diagnosis; negative emotions; stereotype of cancer meant death; labeling “tainted” and “less desirable”; avoidance | Social support; mental factor | Hindering rehabilitation |

| 23 | Wu I et al (2020) | Concealment of the disease; social isolation; fear; hiding their feelings; anxiety; stereotypes of “breast cancer is a infectious disease”, “cancer lead to death” and “cancer is a result of bad karma” | Specific beliefs about cancer | Decreased quality of life; sleep disorder |

| 24 | Yeung N et al (2019) | Negative stereotype of “cancer is contagious”; prejudice; internalizing feelings of stigma | Cultural belief; time after diagnosis | Decreased quality of life |

| 25 | Zamanian H et al (2022) | Impaired body image | Coping strategy | Losing the meaning of life; affecting social activities; decreased quality of life |

| 26 | Pakseresht S et al (2021) | Fear; anxiety | Complication; nature of the disease | Delaying the screening of breast cancer; affecting daily life; preventing the completion of treatment |

| 27 | Mansoor T et al (2020) | Impaired self-image; fear; stereotypes; isolation; concealment of the disease; self-deprecation; social dysfunction; vulnerability | Cultural taboo | Affecting daily life |

| 28 | Jin R et al (2021) | Appearance changes; social exclusion; self-accusation; stereotype of “cancer is a infectious disease”; social isolation | Cultural background; social support; coping style; self-efficacy | Sleep disorder; unsatisfactory sex life; hindering rehabilitation; delaying treatment |

| 29 | Wong C et al (2019) | Negative stereotype; social exclusion | Cultural and religious beliefs | Decreased quality of life |

| 30 | Meacham E et al (2016) | Shame; fright; self-accusation; isolation; social exclusion; misery | Social support; treatment cost; prognosis of the disease | Fear of breast cancer screening; hindering treatment and nursing |

| 31 | Chu Q et al (2021) | Depression; internalizing shame; stereotype of “cancer is a contagious disease or death sentence” | Cultural belief | Decreased quality of life |

| 32 | Tripathi L et al (2017 | Misery; low self-esteem; low woman's sense of identity | Nature of the disease; surgical method | Not mentioned |

| 33 | Jiang F et al (2022) | Low self-esteem; self-image disorder | Spousal support; breast reconstruction; coping style | Decreased quality of life |

| 34 | Ao YT (2023) | Shame; impaired body; apprehensive | Spousal support | Hindering treatment and rehabilitation |

| 35 | Zangeneh S et al (2023) | Impaired sexual health; disappointed; sexual shame; gender stereotypes; sexually incompetent | Cultural beliefs | Decreased quality of marriage |

| 36 | Melhem SJ et al (2023) | Avoided; dreaded; helpless; impaired body; weak; tired; alienation; confidentiality | Spousal support; sociocultural factors | Decreased quality of life; impacting psychological health |

Results

Use of the concept

Definition of stigma in the dictionary

The Cambridge International Dictionary of English describes stigma as “a deep feeling that other people do not respect you or have a good opinion of you”.18 The Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines stigma as “a mark of disgrace or discredit” or “bodily marks resembling the wounds of the crucified Christ”.19 Another meaning of the word “stigma” can be found in the Oxford American Dictionary, where it refers to “a bad reputation that something has because a lot of people have a set idea that it is wrong, often unfairly”.20 Despite the different definitions, a common notion is that stigma is a bad situation, where people are treated specially.

Definition of stigma in literature

The sociologist Goffman21 was the first to propose the concept of stigma in 1963. He defined it as a crucial attribute of tarnishing one's reputation, which could turn a normal person into a stained and degraded person. Thereafter, different understandings of the concept of stigma were formed in different disciplines. For example, in the field of sociology, Link et al22 believed that stigma could be categorized into five components on the basis of labeling theory: labeling, stereotypes, separation, loss of status, and discrimination. In psychology, Corrigan10 proposed that stigma could be categorized as public stigma and self-stigma. Moreover, the author indicated that self-stigma is a social-cognitive process that includes cues, stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination. In the nursing field, Phillips23 proposed that stigma is a social interaction that occurs between a marked and an unmarked person. A person can be marked by any abnormal situation (eg, disease, race, or sexual orientation). In cross-disciplinary and cross-disease research, Stangl et al24 constructed a health stigma and discrimination framework. According to this framework, stigma can be classified into experienced stigma, internalized stigma, perceived stigma, anticipated stigma, and secondary stigma.

Definition of stigma in BCPs in literature

In 1982, Peters-Golden25 first proposed that a sense of stigma exists in BCPs, but he did not provide a specific definition of stigma in his study. As per our understanding, the concept of stigma in BCPs has been relatively poorly described and a clear and uniform definition of stigma in BCPs is lacking.26 Xie15 believed that stigma in BCPs is a disgraceful experience for the patients caused by the modified body image with breast and hair loss. Similarly, Zheng27 proposed that breast cancer stigma is an internal shame experience of BCPs due to illness, which makes BCPs develop feelings of humiliation and guilt. According to the conceptual model of lung cancer-related stigma, Bu et al28 adapted a model of perceived stigma in BCPs to describe the perceived stigma process, including precursors, poor image and esteem, social insulation, limited opportunities, negative changes in identity, and possible responses.

In conclusion, the stigma of BCPs is a complicated process that includes several components, yet the connotation of stigma in BCPs remains unclear. Researchers shared a similar view that the stigma of BCPs was negative feelings of shame and low self-esteem caused by serious changes in body image.15,27 All of these views only highlighted changes in patient's body image and feelings, the influence of social and cultural background on patient were ignored. Moreover, the process, manifestations, and consequences of stigma in BCPs were seldom mentioned. Furthermore, Bu et al28 described the process of stigma in BCPs as a perceived stigma model, which was adapted from the conceptual stigma model of lung cancer. It would be deeply affected by the original lung cancer stigma model and the characteristics of BCPs were not fully considered, lacking systematic research on the stigma of BCPs. These definitions provided references for the analysis of the concept of stigma in BCPs.

Defining attributes

The defining attributes of a concept are the core of concept analysis. They are the most frequently associated features of the concept.17 According to the literature reviewed, the stigma in BCPs has five defining attributes: (1) impaired body image and physiological function; (2) negative stereotypes; (3) mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer; (4) a feeling of avoidance; (5) experienced discrimination (Table 2).

Table 2.

Defining attributes.

| Categories | Subcategories |

|---|---|

| Impaired body image and physiological function | Impaired body image; decreased physiological function |

| Negative stereotypes | Infectious; death; punishment |

| Mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer | Ashamed; low self-esteem; miserable; frightened |

| A feeling of avoidance | Concealment of the disease; concealed emotion; social withdrawal |

| Experienced discrimination | Social discrimination, estrangement, exclusion |

Impaired body image and physiological function

First, impaired body image and physiological function are the most prominent stigma-related attribute in BCPs. Because of surgery and other related treatments, BCPs would experience breast loss, surgical scar, alopecia, blackened and hardened nails, fatigue, decreased sexual desire, sexual dysfunction, and menopausal-like syndrome.3,5,7,15,29,30 Patients usually believe that these symptoms destroy the identity of a traditional female, thereby affecting their external beauty and femininity,26 damaging the normal function of the breast, reducing the hormone level, and finally, causing physiological dysfunction.

Negative stereotypes

Second, several negative public stereotypes are commonly associated with cancer. People consider that “cancer is infectious,”31 “cancer is death,”32 and “cancer is the punishment for the immoral behavior of oneself or ancestors.”8 Because of these aforementioned stereotypes, the public views BCPs through colored glasses. Meanwhile, BCPs may further internalize these negative stereotypes and appear self-denial.

Mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer

The third attribute is mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer. Developing breast cancer is a stressful life event for patients, which results in the generation of stigma and a range of mixed negative emotions. This attribute can also be associated with the particularity of the diseased site and the destructiveness of the surgical methods. The most common negative emotions include ashamed,9,33,34 self-contemptuous,9,35 miserable, and frightened.29,36,37 For example, breast loss and discrimination by others make BCPs feel ashamed and self-contemptuous. Postoperative pain and treatment make BCPs feel miserable. Cancer recurrence and related complications make them frightened. BCPs develop serious psychological problems because of this long-standing stigma. In addition, this stigma can affect postoperative recovery and the quality of life of BCPs as well.9

A feeling of avoidance

The fourth attribute can be defined as a feeling of avoidance that involves concealment of the disease,27,38 concealed passive emotions, and social withdrawal.33,39 The degree of concealment of the disease is closely associated with the surgical approach. Patients who undergo total mastectomy tend to hide the disease and prefer to wear loose clothes.7,40 To keep their family and friends from worrying, BCPs avoid talking to others and actively hide their emotions and feelings, which may result in emotional expression disorder. Regarding their social activity, BCPs often feel uncomfortable with the changes in their body image and the attitude of people around them. Thus, these patients are more likely to reduce or even avoid social activities to conceal their illness and feelings.

Experienced discrimination

The fifth attribute is experienced discrimination. Experienced discrimination includes social discrimination,41 estrangements, and exclusion.36,39 BCPs are easier to be discriminated against and excluded in their daily life, social activities, and work. Fatigue and weakness are always experienced following surgery; therefore, BCPs can only perform some light housework. Some people believe that people develop cancer is a punishment for their immoral behavior42; this belief results in the discrimination and exclusion of patients. BCPs are barely hired by companies because it is generally recognized that these patients may be not qualified to undertake a hectic work schedule.

Constructed cases

Model case

A model case is an example of the application of the concept that demonstrates all the defining attributes of the concept or even constructs by analysts.17 This case described a 44-year-old woman (Mrs. Li) who was diagnosed with breast cancer and accordingly underwent a mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. Because she was ill, the attitude of her neighbors toward her changed dramatically. They did not greet her when they met as well as deliberately avoided and estranged her. Sometimes, she even heard the neighbors and others talking about her in an unfriendly manner (experienced discrimination). For example, “She must have done something bad to get cancer” and “We should stay away from her” (negative stereotypes). After surgery, she was unwilling to have sex with her husband because of the absence of breast and sexual dysfunction. Besides, she often felt weak and she could only lift something light (impaired body image and physiological function). The villagers often pointed at her breast with a discriminatory look and behavior when she passed by, which made her feel ashamed, anguished, and self-abased (mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer). Mrs. Li believed that developing breast cancer was a very humiliating thing, and she was unwilling to tell others about her illness. Gradually, she began to keep her inner feelings to herself and disconnect from her old friends (a feeling of avoidance). The aforementioned case fits all attributes of stigma in BCPs.

Borderline case

Borderline case is an example that presents some defining attributes of the concept but not all of them.17 Mrs. Zhang is a 47-year-old patient who had undergone a mastectomy. After diagnosis with cancer, she began to become taciturn. She did not inform anyone about her illness, except her parents. Since she was ill, she barely participated in any social activity and even rarely contacted her neighbors and friends who used to get along well with her (a feeling of avoidance). Breast loss and other uncomfortable surgery-induced physical symptoms generated negative emotions of inferiority, shame, and agony (mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer). Owing to treatment-related complications such as upper limb lymphedema or fatigue, her arms restricted her from performing light housework and other similar basic activities, which further aggravated the idea that “She was a useless person” (impaired body image and physiological function). Fortunately, her neighbors and friends often visited her after hearing about her sickness. No one exhibited estranged behavior toward her or rejected her. They chatted with her and offered her encouragement and support to help her regain confidence. This case presents some attributes of stigma in BCPs, such as impaired body image and physiological function, mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer, and a feeling of avoidance. However, other attributes of negative stereotypes and experienced discrimination are not recorded.

Related case

Related case is an example that is related to the concept but it does not contain all the defining attributes.17 In this study, the concept of “guilt” is described as the related concept of stigma in BCPs. Mrs. Wang, a 41-year-old woman, was diagnosed with breast cancer and received modified radical mastectomy. She regretted not having the physical examination in time and she thought that this disease must be the result of her bad living habits. Because of her illness, not only was she unable to continue working, but she had to spend a lot of money on her treatment, which made her a burden to her family. In addition, she felt sorry for her family because she did not fulfill her obligations as a mother and wife and she could not take good care of them. She was afraid that her disease would be passed on to her daughter, which brought her guilt. She often felt very depressed and she was not satisfied with her current state. The above case is related to stigma in BCPs but lacks critical attributes of the concept.

Contrary case

Contrary case is an example that does not present any of the defining attributes of the concept.17 Mrs. Lin, a 39-year-old woman, was diagnosed with stage ⅡA breast cancer, for which she received breast-conserving surgery. She was an optimistic person and actively sought related health services. Mrs. Lin was sufficiently confident that she would defeat cancer because her tumor was discovered in the early period and her prognosis was also relatively better. Her friends and colleagues were all concerned about her health and visited her often during her hospitalization. Instead of avoiding them, Mrs. Lin shared her experiences of hospitalization and inner feelings. The aforementioned case presents no attributes of stigma in BCPs.

Antecedents

Antecedents are those events or incidents that must occur or be in place before the occurrence of the concept.17 The antecedents of stigma in BCPs mainly contain four themes. (1) Implementation of breast surgery and postoperative time: studies have shown that the choice of different surgical methods affects the stigma level.43 In other words, the stigma level of patients who have undergone total mastectomy is apparently higher than that of those who have undergone breast-conserving surgery.8,27 Breast-conserving surgery appears to have a protective effect.43 After the operation, the BCPs' stigma changes with the postoperative time, the longer the postoperative time, the higher the patients’ stigma.39,40 (2) Negative psychological factors: low self-efficacy level, pessimism, and coping style of avoidance or submission are considered crucial factors influencing the development of stigma in BCPs.8,36 (3) The lack of social support: past studies have revealed that social support for BCPs is significantly associated with stigma level.8,33 More specifically, BCPs who lack material and spiritual support from family and society are more prone to developing stigma.15 (4) Cultural beliefs: in South Asia, breast cancer is believed to be infectious and hereditary, and it can pass on to the next generation.8 The rooted cultural beliefs usually lead to stigma among BCPs in South Asia.

Consequences

Consequences are those events or incidents that occur because of the occurrence of the concept.17 The four main outcomes of stigma in BCPs are as follows: (1) Decreased quality of life: long-standing stigma severely affects physiological–psychological–social functions and induces anxiety, fatigue, sleep disorder, and social avoidance in BCPs.42 Finally, these would result in lower quality of life in BCPs.44 (2) Affecting postoperative rehabilitation: mix of stigma-associated negative emotions not only reduce treatment enthusiasm among patients but also prevent them from care engagement, which are unfavorable for their postoperative rehabilitation.45 (3) Negative effects on healthcare-seeking behavior: studies have shown that stigma can lead patients to delay treatment and reduce patient compliance with postoperative re-examination.36,46 These behaviors would severely affect the survival rate of BCPs.47 (4) Decreased quality of marriage: stigma caused by breast loss and decreased physiological function further brings about sexual dysfunction, sexual desire disorder, and lower marital expectation.7,39

Empirical referents

Empirical referents are classes or categories of actual phenomena demonstrating the occurrence of the concept itself, which is related closely to the defining attributes.17 Currently, the most commonly used tools for assessing stigma in BCPs are the Social Impact Scale (SIS) and Body Image After Breast Cancer Questionnaire (BIBCQ).

SIS

The SIS was developed by Fife48 and Wright to measure the stigma level in patients with AIDS and cancer. This 24-item scale consists of four dimensions: social rejection, financial insecurity, internalized shame, and social isolation. This scale has a total Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.95, and the correlation coefficient of each dimension ranges from 0.28 to 0.66. Two attributes, namely “a feeling of avoidance” and “experienced discrimination,” are covered by this scale. However, attributes such as “impaired body image and physiological function,” “negative stereotypes,” and “mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer” are missing in this tool. Therefore, this scale may not comprehensively assess the stigma level in BCPs.

BIBCQ

The BIBCQ was developed by Baxer49 to assess the stigma level in BCPs who underwent different surgeries (breast-conserving surgery or total mastectomy). BIBCQ is a 53-item questionnaire with six dimensions, with Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.77–0.87 and intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.77–0.85. This tool evaluates body image, physiological function, and experienced discrimination. Other attributes such as “negative stereotypes,” “mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer,” and “a feeling of avoidance” are not assessed by BBCIQ.

Discussion

In this study, we determined the five defining attributes and clarified antecedents, consequences, cases, and empirical referents associated with stigma in BCPs. Based on the results of the concept analysis, the operational definition of stigma in BCPs refers to “a state in which BCPs experience damaged body image, decreased physical function, public stereotypes, and further develop mixed negative feelings. These experiences and feelings will lead them to experience discrimination, conceal illness, hide emotions, and avoid social activity.” A concept diagram of stigma in BCPs was constructed to manifest this definition, exhibiting influential relationships among attributes, antecedents, and consequences (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Concept diagram of the stigma in BCPs. BCPs, breast cancer patients.

This study identified four main antecedents of stigma in BCPs: the implementation of breast surgery and postoperative time, negative psychological factors, the lack of social support, and cultural beliefs. Among them, the implementation of breast surgery especially the mastectomy is a key factor associated with stigma in BCPs.8,27 Although modified radical mastectomy has been developed, some patients still need to undergo total mastectomy. Therefore, for one thing, medical technology needs to be further advanced to reduce the damage to patients' body image caused by surgery, and for another, the preoperative stigma risk should be considered and intervened before surgery.

The present study revealed that stigma in BCPs includes some common attributes of the stigma associated with other diseases and distinctive attributes. The common attributes of stigma are “negative stereotypes,” “a feeling of avoidance,” and “experienced discrimination,” which are the manifestations of disease stigma. In addition, “impaired body image and physiological function” is the most prominent attribute of stigma in BCPs, which is not observed in studies on patients with mental illness or HIV. Subcategories within the “mixed negative feelings” attribute differed from attribute of stigma identified in patients with diabetes or other illnesses. In other words, mixed negative emotions in BCPs are derived from disease specificity, impaired body image, social prejudice, and fear of cancer. These mixed negative emotions are mainly manifested as fear, shame, inferiority, and misery. For example, the negative emotions of diabetes patients are embarrassment, regret, and self-blame for failing to control their diet and exercise. According to the existing literature, negative emotions associated with diabetes patients have not been reported in BCPs. In general, when compared to the other disease stigma, the five pivotal attributes proposed in this study could help healthcare professionals better comprehend and identify stigma in BCPs.

This study identified four adverse influences of stigma in BCPs: decreased quality of life, affecting postoperative rehabilitation, negative effects on healthcare-seeking behavior, and decreased quality of marriage. These findings suggest that the long-existing stigma results in serious consequences and injuries in BCPs. So healthcare professionals must attach more importance to stigma among BCPs during nursing practice and administer the corresponding interventions in time.

Implications

The concept analysis results in the study provide theoretical support for constructing a conceptual model of stigma in BCPs. The existing stigma models are mainly universal models or models for particular diseases. Scholars have applied universal or particular disease stigma models to BCPs, and inapplicable problems are encountered in the research practice. Take Bu et al28 for example, who constructed a model of perceived stigma for BCPs based on the model of perceived lung cancer stigma. There are some similarities in the stigma concept of different diseases, but different disease sites induce different stigma manifestations and processes. The content of this model was relatively general and broad and only added a structure of “poor image esteem” in the perceived stigma, while the other contents were not revised. Thus it might not be applicable to fully explain the process of stigma in BCPs. As observed in our analysis, because of the specificity of stigma in BCPs, the antecedents, attributes, experiences, and consequences associated with stigma in BCPs were not accurately reflected in the universal or other particular disease stigma model.

The study results also provide a theoretical basis for the development and evaluation of tools for assessing stigma in BCPs. Clarifying the attributes and operational definition of the concept are the basis for developing assessment tools that can accurately evaluate stigma in BCPs. Most existing stigma assessment tools are adapted from mental illness stigma tools and these stigma scales do not fully reflect attributes of stigma in BCPs.50,51 Although Bu et al28 developed a specific scale to measure the stigma of BCPs, they did not propose any explicit operational definition of stigma in BCPs and lacked an in-depth understanding of the concept. What is more, factor analyses showed that there were missing dimensions in this measure and it did not sufficiently reflect the multidimensional construct of stigma in BCPs, probably because of the unclear definition of the concept. Specifically, this scale was mainly based on the perspective of patients' self-perception of stigma, which included the dimensions of “self-image impairment”, “social isolation”, “discrimination”, and “internalized stigma”. These dimensions were consistent with the attributes of “impaired body image”, “experienced discrimination”, and “a feeling of avoidance” proposed in our study, but the other main attributes of “impaired physiological function”, “negative stereotype”, and “mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer” were not presented in the content of the scale. Therefore, these existing scales might not fully and accurately reflect the concept of stigma in BCPs.

The results of the concept analysis provide a reference for the subsequent construction of nursing intervention strategies in BCPs. The five attributes determined in this study can serve as a basis for interventions. These findings can facilitate our understanding of how to reduce the stigma level in BCPs by rebuilding their body image, offering them psychological support therapy, and raising awareness among the public.

Limitations

Due to the low incidence and particularity of male breast cancer, the objects included in the literature were all female BCPs. Therefore, the definition of the concept may not apply to male BCPs. Most of the studies included in the present work were investigative, with very few qualitative studies. The understanding of patients’ true inner thoughts might not be adequately comprehensive, which made the concept of stigma in BCPs not abundant enough. Therefore, more qualitative studies are warranted for the in-depth exploration of stigma among BCPs from a multidimensional perspective. The results from cross-sectional studies have demonstrated that the stigma level is different at different stages. More numbers of longitudinal studies are required to delineate the development trajectory of stigma in BCPs.

Conclusions

On the basis of the concept analysis of stigma in BCPs, we identified five crucial attributes, namely “impaired body image and physiological function,” “negative stereotypes,” “mixed negative feelings about developing breast cancer,” “a feeling of avoidance,” and “experienced discrimination”. This concept analysis provides healthcare professionals with a better understanding of stigma in BCPs. Moreover, it allows them to accurately and timely identify BCPs who are experiencing higher levels of stigma and administer appropriate interventions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Deqin Huang for her guidance and support in the Methodology and Writing – Review & Editing of this paper.

CRediT author statement

Jieming Wu: Conceptualization, Investigation, Data Curation, Formal analysis, Writing – Original Draft. Ni Zeng: Investigation, Data Curation, Writing – Original Draft. Liping Wang: Methodology, Resources, Writing – Review & Editing. Liyan Yao: Data Curation, Formal analysis, Supervision. All authors had full access to all the data in the study, and the corresponding authors had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. The corresponding authors attest that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

This study was supported by Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. LY18H160061). The funders had no role in considering the study design or in the collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or decision to submit the article for publication.

Ethics statement

Not required.

Data availability statement

Data available on request from the authors.

References

- 1.Sung H., Ferlay J., Siegel R.L., et al. Global cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA A Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mo M., Yuan J., Zhou C., et al. Changing long-term survival of Chinese breast cancer patients—experience from a large single institution hospital based cancer registry with 35 thousand patients. China Oncol. 2020;30(2):90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mansoor T., Abid S. Negotiating femininity, motherhood and beauty: experiences of Pakistani women breast cancer patients. Asian J Wom Stud. 2020;26(4):485–502. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu L.L., Jiang X.L., Peng W.X., et al. Longitudinal analysis of symptom clusters in chemotherapy patients after breast cancer surgery. Journal of Nursing science. 2022;37(20):23–27. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gan L., Fang Q. Status and influencing factors of sexual dysfunction in young breast cancer patients during endocrine therapy. Chin J of Oncol Prev and Treat. 2022;14(5):558–564. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao Y.F. Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine; 2021. Analysis of the Factors Affecting the Quality of Life of Breast Cancer Patients Treated with Endocrine Therapy and Clinical Observation of the Intervention Effect of Shugan Jianpi Decoction [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suwankhong D., Liamputtong P. Breast cancer treatment: experiences of changes and social stigma among Thai women in Southern Thailand. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39(3):213–220. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin R., Xie T., Zhang L., et al. Stigma and its influencing factors among breast cancer survivors in China: a cross-sectional study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;52 doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2021.101972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng X.N., Yang X.X., Ou Z.X. Investigation of the illness stigma after breast modified radical mastectomy. Med Innov China. 2014;11(27):69–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corrigan P. How stigma interferes with mental health care. Am Psychol. 2004;59(7):614–625. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.7.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herek G.M., Capitanio J.P., Widaman K.F. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the United States: prevalence and trends, 1991-1999. Am J Publ Health. 2002;92(3):371–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tripathi L., Datta S.S., Agrawal S.K., et al. Stigma perceived by women following surgery for breast cancer. Indian J Med Paediatr Oncol. 2017;38(2):146–152. doi: 10.4103/ijmpo.ijmpo_74_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lan Y.T., Han J.M. Research progress on stigma of patients after radical breast cancer mastectomy. Psychol Mag. 2022;17(4):238–240. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pakseresht S., Tavakolinia S., Leili E.K. Determination of the association between perceived stigma and delay in help-seeking behavior of women with breast cancer. Mædica. 2021;16(3):458–462. doi: 10.26574/maedica.2021.16.3.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xie X.W. Yanbian University; 2020. Study on the relationship between body image level, Social Support and Stigma in Patients with Breast Cancer After Surgery [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X.X., Jiang P. Tools for stigma assessment in breast cancer patients. Modern Clin Nurs. 2022;21(2):76–81. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Walker L.O., Avant K.C. 6th ed. Pearson; New York: 2019. Strategies for Theory Construction in Nursing. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Susan A.M., Ann F., Guy J., et al. Shanghai Foreign Language Edication Press; Shanghai: 1997. Cambridge International Dictionary of English. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merriam W.I. World Publishing Corporation; Beijing: 1994. The Merriam Webster Dictionary. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhao C.L., Chen M.S., Ma L.M. The Commercial Press; Beijing: 2015. Oxford American Dictionary for Learners of English. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goffman E. Englewood Cliffs:Prentice-Hall; 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link B.G. Stigma: many mechanisms require multifaceted responses. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2001;10(1):8–11. doi: 10.1017/s1121189x00008484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Phillips K.D., Moneyham L., Tavakoli A. Development of an instrument to measure internalized stigma in those with HIV/AIDS. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2011;32(6):359–366. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2011.575533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stangl A.L., Earnshaw V.A., Logie C.H., et al. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: a global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):31. doi: 10.1186/s12916-019-1271-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters-Golden H. Breast cancer: varied perceptions of social support in the illness experience. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(4):483–491. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang S. China Medical University; 2015. A Study on the Influencing Factors of Stigma Among Patients with Breast Cancer [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng C.X. Southern Medical University; 2020. Investigation of Stigma of Postoperative Patients with Breast Cancer and Effert of Expressive Writing Intervention [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bu X., Li S., Cheng A., et al. Breast cancer stigma scale: a reliable and valid stigma measure for patients with breast cancer. Front Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.841280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laza-Vásquez C., Rodríguez-Vélez M.E., Lasso Conde J., et al. Experiences of young mastectomised Colombian women: an ethnographic study. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition) 2021;31(2):107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zangeneh S., Savabi-Esfahani M., Taleghani F., et al. A silence full of words: sociocultural beliefs behind the sexual health of Iranian women undergoing breast cancer treatment, a qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31(1) doi: 10.1007/s00520-022-07502-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yeung N., Lu Q., Mak W. Self-perceived burden mediates the relationship between self-stigma and quality of life among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(9):3337–3345. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4630-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang K., Yang J. Special groups of stigma and its hidden consequences——take patients with breast cancer and cervical cancer as an example. Social Sci Heilongjiang. 2019;(5):91–97. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Warmoth K., Cheung B., You J., et al. Exploring the social needs and challenges of Chinese American immigrant breast cancer survivors: a qualitative study using an expressive writing approach. Int J Behav Med. 2017;24(6):827–835. doi: 10.1007/s12529-017-9661-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levin-Dagan N., Baum N. Passing as normal: negotiating boundaries and coping with male breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 2021;284 doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao Y.Q. Qingdao University of Science and Technology; 2022. Case Study of Rational Emotive Therapy in Female Breast Cancer Patients' Stigma [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meacham E., Orem J., Nakigudde G., et al. Exploring stigma as a barrier to cancer service engagement with breast cancer survivors in Kampala, Uganda. Psycho Oncol. 2016;25(10):1206–1211. doi: 10.1002/pon.4215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sprung B.R., Janotha B.L., Steckel A.J. The lived experience of breast cancer patients and couple distress. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2011;23(11):619–627. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2011.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solikhah S., Matahari R., Utami F.P., et al. Breast cancer stigma among Indonesian women: a case study of breast cancer patients. BMC Wom Health. 2020;20(1):1–116. doi: 10.1186/s12905-020-00983-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.He D.M., Hu J.P., Gao Q., et al. Stigma of patients after radical mastectomy from the phenomenological perspective. Modern Clin Nurs. 2020;19(10):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kong R.H. Shandong University; 2015. The Status and Influencing Factors of Stigma in Young Patients with Breast Cancer [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xiao H.M., Zhou X.Y., Zhang X.J., et al. Influencing factors of stigma in breast cancer patients after operation and its relationship with self-esteem, quality of life and psychosocial adaptability. Prog Mod Biomed. 2021;21(23):4522–4526. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wu I., Tsai W., McNeill L.H., et al. The associations of self-stigma, social constraints, and sleep among Chinese American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28(8):3935–3944. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y., Huang B.F., Su X.N. Study on the effect of different surgical methods on the stigma and self-image of breast cancer patients. Chin Foreign Med Res. 2020;18(32):28–30. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zamanian H., Amini-Tehrani M., Jalali Z., et al. Stigma and quality of life in women with breast cancer: mediation and moderation model of social support, sense of coherence, and coping strategies. Front Psychol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.657992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li Y.F. Hunan Normal University; 2017. A Study of Stigma and its Influencing Factors in Patients with Breast Cancer after Operation [dissertation] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Espina C., McKenzie F., Dos-Santos-Silva I. Delayed presentation and diagnosis of breast cancer in African women: a systematic review. Ann Epidemiol. 2017;27(10):659–671. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2017.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gangane N., Anshu, Manvatkar S., et al. Prevalence and risk factors for patient delay among women with breast cancer in rural India. Asia Pac J Publ Health. 2016;28(1):72–82. doi: 10.1177/1010539515620630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fife B.L., Wright E.R. The dimensionality of stigma: a comparison of its impact on the self of persons with HIV/AIDS and cancer. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(1):50–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Baxter N.N., Goodwin P.J., Mcleod R.S., et al. Reliability and validity of the body image after breast cancer questionnaire. Breast J. 2006;12(3):221–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Link B.G. Understanding labeling effects in the area of mental disorders: an assessment of the effects of expectations of rejection. Am Socio Rev. 1987;52(1):96–112. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wahl O.F. Mental health consumers' experience of stigma. Schizophr Bull. 1999;25(3):467–478. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request from the authors.