Abstract

Purpose

Given the significance of the US Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1 score moving from a 3-digit value to pass/fail, the authors investigated the impact of the change on students’ anxiety, approach to learning, and curiosity.

Method

Two cohorts of pre-clerkship medical students at three medical schools completed a composite of four instruments: the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, the revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire, the Interest/Deprivation Type Epistemic Curiosity Scale, and the Short Grit Scale prior to taking the last 3-digit scored Step 1 in 2021 or taking the first pass/fail scored Step 1 in 2022. Responses of 3-digit and pass/fail exam takers were compared (Mann–Whitney U) and multiple regression path analysis was performed to determine the factors that significantly impacted learning strategies.

Results

There was no difference between 3-digit (n = 86) and pass/fail exam takers (n = 154) in anxiety (STA-I scores, 50 vs. 49, p = 0.85), shallow learning strategies (22 vs. 23, p = 0.84), or interest curiosity scores (median scores 15 vs. 15, p = 0.07). However, pass/fail exam takers had lower deprivation curiosity scores (median 12 vs. 11, p = 0.03) and showed a decline in deep learning strategies (30 vs. 27, p = 0.0012). Path analysis indicated the decline in deep learning strategies was due to the change in exam scoring (β = − 2.0428, p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Counter to the stated hypothesis and intentions, the initial impact of the change to pass/fail grading for USMLE Step 1 failed to reduce learner anxiety, and reduced curiosity and deep learning strategies.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-023-01878-w.

Keywords: USMLE Step 1 examination, Learner anxiety, Curiosity, Learning behaviors

Introduction

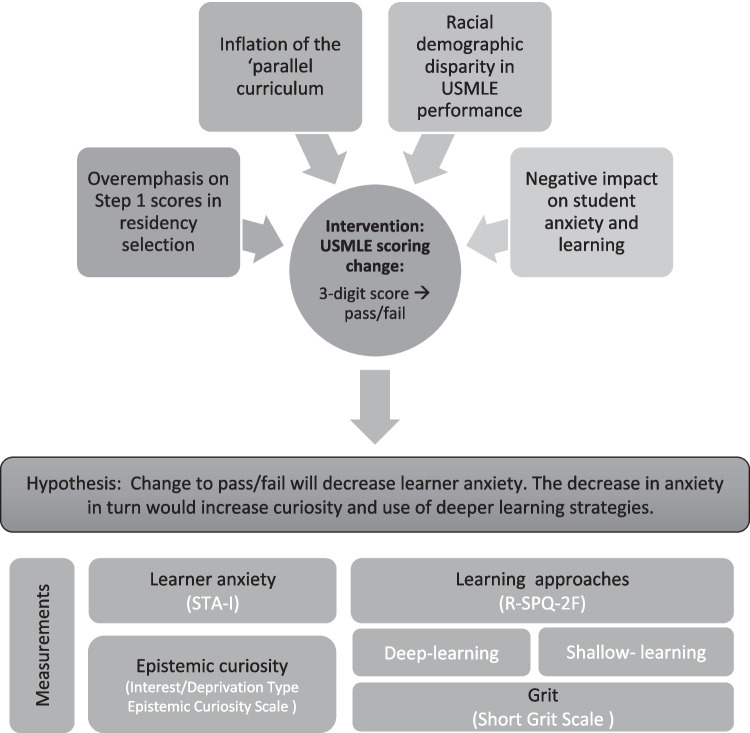

In February 2020, the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) announced the US Medical Licensing Exam (USMLE) Step 1 would change score reporting from a 3-digit value to pass/fail in 2022. This decision was based on findings from the Invitational Conference on USMLE Scoring (InCUS) [1] and was a response to the overemphasis on Step 1 scores in residency screening and selection, the racial demographic disparity in USMLE performance, inflation of the “parallel curriculum,” and negative impact on students’ well-being [2–4] and learning [5]. With approximately half the student population reportedly experiencing burn-out [4] and a third of students experiencing signs of depression or anxiety [6], the shift to pass/fail appeared to have merit. While the long-term and ensuing consequences of this change will become apparent in the future, the immediate impact on learner well-being and learning approaches can be explored now.

Learner well-being is comprised of many elements, both positive and negative, that ultimately define the ability of an individual to cope (or thrive) in their environment [7]. One major negative contributor to learner well-being is anxiety, and although this can originate from a number of sources in the pre-clerkship years, Step 1 is reportedly a major anxiety-provoking experience [2]. High levels of anxiety diminish goal-directed attention and concentration, memory, and perceptual-motor function [8] — all of which are critical for effective learning, preparation for high-stakes evaluations, and clinical practice [8]. In the context of undergraduate medical education, the impact of anxiety and heightened stress on learning strategies may manifest as superficial or shallow learning [9] or potentially decreased curiosity. When engaging in shallow learning, many students employ strategies like mnemonics, highlighting, and note-taking to learn vocabulary and essential content. By contrast, when students commit to deep learning, they employ self-regulation strategies such as content synthesis, elaborative interrogation, and metacognition [10]. The transition to shallow learning strategies is driven by fear of failure and is a coping strategy with the short-term goal of passing assessments [11]. However, shallow learning hampers development of a cognitive schema of sustained connections essential for lifelong learning [12].

Conversely, a deep learning approach is associated with genuine curiosity and better academic outcomes [13, 14]. Curiosity is at the heart of medical education, but unfortunately, so is learner anxiety [6, 9]. With anxiety’s detrimental impact on learner curiosity, the Step 1 transition to pass/fail might afford the opportunity to re-engage curiosity about medical knowledge. Epistemic curiosity, defined as “the desire to know” [15], impacts student behavior when setting goals, and helps determine the level of effort learners are willing to expend in attaining those goals. Reducing anxiety’s deleterious effect on curiosity (and well-being) may promote a deeper, more curious learner and have a positive impact on the profession [16].

The antithesis of anxiety is “grit,” defined as “the perseverance to achieve long-term goals” [17, 18]. High levels of grit are associated with lower anxiety and burn-out [18, 19] (Fig. 1) as well as higher levels of well-being [19], self-regulated learning, and academic performance [20, 21]. While higher levels of grit correlate with increased performance [22], it also fosters mastery-oriented learning. Although an indicator of inherent resilience [19, 23], accounting for grit is important when determining the impact of anxiety.

Fig. 1.

Summary of the study design and rationale. The change to a pass/fail would decrease student anxiety, increasing curiosity, and result in deeper learning strategies. Grit was measured as a covariant given its influence on several of these factors. STA-I, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory; R-SPQ-2F, revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire

The positive impact of the transition to pass/fail in pre-clerkship grading (e.g., learner well-being, reduced anxiety) indicated that the change to pass/fail in STEP1 would also have positive implications [24]. This, and the intentions of INCUS, prompted us to consider the following hypothesis supported by a framework adapted from LePine et al. [25] (Fig. 1): Students who will take USMLE Step 1 reported as pass/fail will be less anxious, thereby more curious and engage in deeper learning processes. To test this, we assessed medical students’ anxiety, learning approaches, and curiosity, prior to taking a 3-digit scored Step 1 and prior to taking a pass/fail Step 1.

Methods

Participants and Learning Environments

We invited participation from two medical school classes: 2023 (the last to take the 3-digit scored Step 1) and 2024 (the first to take a pass/fail graded Step 1). Invitees studied at one of three schools (sample of convenience): Zucker School of Medicine (ZSOM; 100 students/class), Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine (VTCSOM; 42 students/class), and Tulane University School of Medicine (TUSOM; 190 students/class). The study was approved with waived written consent by the Virginia Tech IRB (Protocol #21-241) and VT approval was accepted by the IRBs at ZSOM and TUSOM.

Both VTCSOM and ZSOM deliver content in a problem-based curricular format while TUSOM uses a systems-based active lecture approach. At all programs, both cohorts of students had a minimum of 6-weeks dedicated study time prior to taking their Step 1 exam. Similar resources for exam preparation across programs included vouchers for Comprehensive Basic Science Self Assessments, access to learning support specialists, faculty, and peer tutors. Students at VTCSOM and ZSOM also had university-provided access to UWorld Question banks; TUSOM provided voluntary, faculty led preparation sessions.

Assessment of Learning Approaches, Anxiety, Curiosity, and Grit

Participants anonymously completed the following instruments: (1) the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STA-I) [26] to assess the level of anxiety, (2) the revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire (R-SPQ-2F) [27] to determine approach and depth of learning, (3) the Interest(I)/Deprivation(D) Type Epistemic Curiosity Scale [13], (4) the Short Grit Scale [17]. Grit was measured as a covariable for inclusion in the multiple regression path analysis as it impacts anxiety and burn-out [18, 19] well-being [19], self-regulated learning, and academic performance [20, 21]. Epistemic curiosity was divided into I and D components. I-type curiosity is driven by the personal satisfaction of gaining new knowledge and is associated with mastery-oriented (deep) learning [13, 14]. Alternatively, D-type curiosity manifests as a judicious and immediate approach to address the discomfort associated with a gap in knowledge [13, 28]. Both types of curiosity are associated with deep learning approaches [29].

The class of 2023 was invited to participate in the study during the spring of 2021, prior to taking the last 3-digit scored Step 1. The class of 2024 was invited to participate in the study during the spring of 2022, prior to taking the first pass/fail graded Step 1. Invitations were sent via email to all members of each class with a reminder sent a week later. Survey instructions were intentionally general so as not to bias participant response, stating only “Thank you for choosing to participate in this research study to gain a better understanding of the impact of Pass/Fail grading on the STEP 1 exam. This study will extend the current body of knowledge of information that influenced the change to this exam.” Survey responses were stored on a secure drive at VTCSOM.

Analysis

The final scores for each of the four survey responses were calculated as previously described [13, 17, 26, 27] for each participant. The Short Grit and STA-I surveys generated single values for grit and anxiety, respectively, whereas the R-SPQ-2F survey generated measures of both deep and shallow learning strategies and the Interest/Deprivation Type Epistemic Curiosity Scale generated values for interest curiosity (I-type) and deprivation curiosity (D-type).

Prior to pooling data from the participating schools, any effect of the school the participants attended on each collected survey response was assessed using a Kruskal–Wallis test (critical value < 0.05, corrected for multiple comparisons). Collated scores from each class, for each instrument, were compared using Mann–Whitney U tests.

Pooled data from both classes was assessed to determine whether Grit scores correlated with perceived anxiety, curiosity, or learning strategies (Spearman’s ranked correlation coefficient). For outcome factors (deep and shallow learning strategies) that demonstrated inter-class differences, a path (multiple regression) analysis [30] was performed to determine the impact (magnitude and direction) of explanatory variables (grit, anxiety, I- and D-curiosity). Because an association between grit and anxiety has been documented [31], an a priori interaction between these two variables was included in the regression model.

Results

The aggregate survey response rate was 37% (n = 86 3-digit scored; n = 154 pass/fail scored exam). Individual program survey responses were Tulane 3-digit scored = 24, Tulane pass/fail scored = 61, VTCSOM 3-digit scored = 21, VTCSOM pass/fail scored = 26, Zucker 3-digit scored = 49, and Zucker pass/fail scored = 67. There was no effect (Kruskal–Wallis) of school on grit (p = 0.630), anxiety (p = 0.898), I-type curiosity (p = 0.789), D-type curiosity (p = 0.975), deep learning strategies (p = 0.589), or shallow learning strategies (p = 0.077). Median instrument scores (range and IQR) for each instrument are shown for both classes in Fig. 2. There was no statistical difference in grit (p = 0.22), anxiety (p = 0.85), or I-type curiosity (p = 0.07) between 3-digit and pass/fail exam takers. However, compared to students taking a 3-digit scored Step 1 exam, students taking a pass/fail scored Step 1 showed significantly lower levels of deep learning (p = 0.0012) and D-type curiosity (p = 0.03). Correlation analysis between grit and the responses to the other instruments confirmed previous findings, summarized in Table 1, showing grit was inversely correlated with anxiety and shallow learning (p < 0.0001) [21, 31] and directly correlated with both types of curiosity and deep learning approaches [29, 32] (p < 0.0001). Anxiety was inversely correlated with use of deep learning strategies (Spearman r = − 0.257, p < 0.001) but was not correlated with the adoption of shallow learning strategies (Spearman r = 0.079, p = 0.119).

Fig. 2.

Grit, anxiety, learning approaches, and curiosity prior to taking a 3-digit or pass/fail Step 1. Survey responses to the Short Grit, STA-I, R-SPQ-2F, and I-D Curiosity scales by medical students about to take numeric scored — or pass/fail Step 1 exam. Median values are shown and labelled with interquartile range (boxes) and ranges (whiskers). *Significant difference (one-tailed, Mann–Whitney U)

Table 1.

Cross-correlates for grit, anxiety, learning approaches, and curiosity

| Cross correlates | r value | p value |

|---|---|---|

| GRIT vs. STA-I | −0.243 | 0.000104 |

| GRIT vs. R-SPQ-2F DEEP | 0.348 | 0.00000003 |

| GRIT vs. R-SPQ-2F Shallow | −0.262 | 0.00002892 |

| GRIT vs. I-Curiosity | 0.3274 | 0.00000019 |

| GRIT vs. D-Curiosity | 0.214 | 0.00057275 |

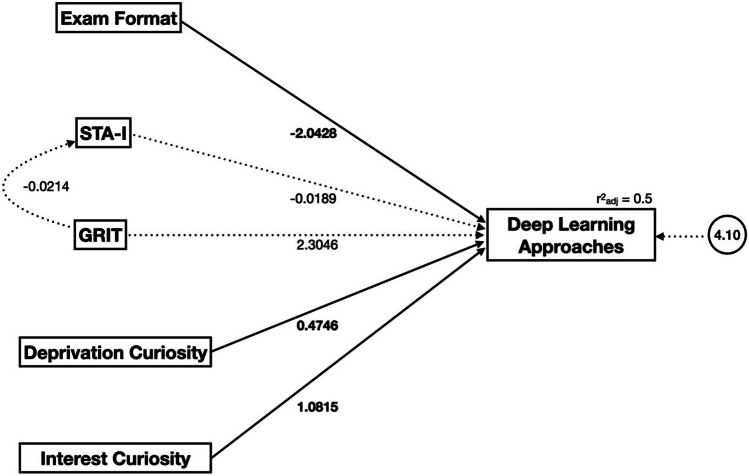

The decline in deep learning approaches observed with pass/fail exam takers compared to 3-digit exam takers was analysed further using path analysis (Fig. 3). The model developed used exam format, anxiety, grit, and both forms of curiosity as explanatory variables and accounted for the known interaction of grit and anxiety, adapted from Richards et al. [14]. The adjusted r2 of the model was 0.5. Exam format had a relatively large (β = − 2.0428) negative impact on deep learning that was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Both I- and D-type curiosity had direct effects on deep learning approaches (β = 1.0815 and 0.4746 respectively) that were significant (p < 0.05). There was no significant impact of either grit (p = 0.333) or anxiety (p = 0.915). When the same model was used to describe shallow learning approaches, the adjusted r2 was 0.145 (see Supplemental Fig. 1).

Fig. 3.

Path diagram of the relationships between deep learning approaches and exam format (3-digit score or pass/fall), anxiety (STA-I), grit, deprivation curiosity, and interest curiosity of second year medical students prior to taking either a 3-digit scored or pass/fail Step 1 exam (n = 240). Significant paths and their b coefficients are in bold; nonsignificant paths are dashed. The model has an adjusted r.2 of 0.5 and includes a constant (shown in the circle)

Discussion

In changing Step 1 score reporting to pass/fail, the USMLE responded to recommendations in an effort to curtail the “Step 1 climate” [1, 33]. While many of the speculated impacts will take years to evaluate, this study demonstrates that the initial impact on anxiety, learning strategies, and curiosity with this cohort is contrary to our original hypothesis. Instead, our data better reflect the pre-change perspective of medical students that anxiety would not be mitigated [33–36]. More importantly, these data suggest the shift to pass/fail was associated with a decreased deprivation-driven (D-type) curiosity and negatively impacted deep learning approaches in our learner population. These outcomes are also counter to the reduced anxiety and increased intrinsic learning approaches observed after intramural implementation of pass/fail grading in undergraduate medical education [24, 37].

Continued Anxiety

Why would the changes to a national standardized exam fail to ease anxiety in this set of learners? While the degree of anxiety in the two classes was the same, we did not ask about the source of anxiety, and we speculate that it is likely different for each cohort [38]. Indirectly related to the change to pass/fail is an immediate period of uncertainty regarding what metric(s) will replace the numeric score in residency directors’ selection criteria. Although learners taking a pass/fail exam were relieved of the pressure of attaining a high numeric Step 1 score, they may exhibit a “fear of the unknown” [39] surrounding the speculation of how the change in scoring may impact the residency selection process [34, 40–43]. The predicted change in emphasis by residency directors to clerkship grades and/or the still numerically scored Step 2CK [44] may be the next distraction. If so, the intended mitigation of anxiety by changing to pass/fail may only emerge as the priorities of residency directors becomes clearer in future years calling for the need for continued monitoring.

Change in Learning Approaches

The intricate connections between learning approaches and curiosity in medical education are largely unexplored, but all are inversely influenced by learner anxiety [31, 45, 46]. While levels of anxiety could still be reduced as the consequences of the change to pass/fail on residency selection unfold, we postulate that our findings regarding learning approaches may be more persistent and potentially impactful. Our path analysis suggests that although I- and D-curiosity still promoted deep learning strategies as previously shown [29, 32], the negative impact of the change to pass/fail in our cohorts was larger and led to a net decrease in this approach. Our data are consistent with previous studies with grit being directly correlated with deep learning and inversely correlated with anxiety [31, 47] and shallow learning [9]. However, while the path analysis shows a large regression coefficient for grit and deep learning approaches (Fig. 3), it was not statistically significant, suggesting other factors need to be considered. We suggest that this can also, in part, be attributed to the learners’ re-prioritizing their efforts toward successful residency placement.

Deemphasizing Step 1 could contribute to diminished focus on medical knowledge [24] as the change to pass/fail affords students the choice to focus on external achievements (e.g., research projects, community service) to strengthen their residency applications. Consequently, the diminished deep learning approaches observed in this study could be attributed to distraction and re-prioritization, rather than anxiety (consistent with the path analysis model). Although we have treated D-type curiosity as an inherent characteristic, curiosity has previously been shown to be impacted by pre-clinical education [46]. The small but significant decline in D-type curiosity might be also attributed to re-prioritization as students are more tolerant of not knowing basic science content. It has already been suggested that current constructs of medical education are not optimized to support curiosity [46] and this change may contribute to this phenomenon. As curiosity has been touted as essential to the practice of medicine [48], this finding is of concern and continued monitoring will be critical.

Unlike our suggestion that the mitigation of anxiety may come with more confidence in knowing the expectations of residency directors, the same may not be true for deep learning of medical knowledge. If the criteria for a successful residency application no longer include evidence of sustained medical knowledge, the motivation to adopt deep learning strategies may continue to decline. Although only addressing the immediate impact of the transition to pass/fail, our data could therefore signal the onset of a trend, rather than an aberration at the point of transition.

There was no difference in the degree of shallow learning approaches between 3-digit and pass/fall exam takers in the studied populations, and our path analysis model for deep learning strategies did not hold true for shallow learning (explaining only 14.5% of variance, Supplemental Fig. 1). The lack of impact on shallow learning seems somewhat at odds with the decline in deep learning, but this may be due to shallow learning strategies having already been adopted prior to the transition of exam grading format (i.e., by 3-digit and pass/fail exam takers alike). The phenomenon of the parallel curriculum and use of external, third-party resources specific to Step 1 exam success (rather than long-term, deep learning) had been established prior to changes in Step 1 [49, 50]. The multiple-choice format encourages memorization of medical knowledge rather than the curious exploration of relevant topics [29, 33, 51], and the transition to pass/fail grading may perpetuate this use of shallow learning approaches.

Strengths and Limitations

The current study presented results consistent with previous findings [38] and begin to describe the impact of the Step 1 scoring change, but limitations should be considered.

The study cohort is a relatively small sample of undergraduate medical students and there is a noted difference in response rates between classes (for which we have been unable to formulate a viable explanation). Responses to all four surveys were independent of which school participants attended (despite the schools’ varying curricula and matriculants), suggesting that these findings may represent a more generalizable change. Our data only represents the immediate response and our continued data collection and inclusion of more schools (Phase 2) will be important to see if this trend persists. Phase 2 of this study has begun, includes more participating schools, and will allow us to glean insights into how the change in Step 1 scoring influenced student perceptions of the residency application process. Like the change in Step 1 grading, there has been much speculation about how this will change program directors’ approach to the residency applicant selection [52–54], consequently the impact on the learner should continue to be investigated.

The path analysis model explained 50% of the variance in deep learning approaches (adjusted r2 = 0.5). However, our model includes complex behaviors and characteristics. For example, although we measured anxiety, we did not ask participants to attribute their anxiety to any particular source (i.e., taking a 3-digit graded exam, or applying for residency without having taken one). It is very possible that other explanatory variables missing from our model, such as participant demographics and the changing influence of the COVID-19 pandemic (e.g., student well-being and changes in teaching modalities), may contribute to the unexplained variance. Given the complexity of intrinsic and extrinsic variables involved, our model is robust and sufficient to describe a moderate effect but continued and more focused data collection will improve our understanding of the impact from the change to pass/fail.

Conclusions

Although the impetus behind the policy change was multifaceted, reducing student anxiety was a major goal. Our early data suggests this attempt did not result in reduced anxiety; rather, it may have encouraged reliance on less effective learning strategies and reduced curiosity. Taking these early data into consideration, the medical education community should remain vigilant in monitoring the impact on learner well-being in considering some of the potential consequences of this programmatic change. In the long term, as more certainty about the residency application criteria is established and there is less “unknown” to fear, it will be important to track student learning approaches. The commonalities between a psychologically healthy physician and medical student are many [55], and negative impacts to early medical education will likely be perpetuated in the professional, clinical environment. Finally, the potential, long-term de-prioritizing of medical knowledge by undergraduate learners should be carefully monitored and the need to re-imagine both the delivery and assessment of basic sciences should be considered.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dani Backus and Dr. Aubrey Knight for their project assistance, Drs. Richard Schwartzstein and Jed Gonzalo for their insightful comments, and Dr. Allison Tegge for statistical consultation and data review.

Funding

This project was funded in part by the Virginia Tech Center for Teaching and Learning.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The study was approved on March 9, 2021, by the Virginia Tech Internal Review Board (IRB), Protocol #21-241. It was deemed exempt under 45 CFR 46.104(d) category 2(i). VT approval was accepted by the IRBs at ZSOM and TUSOM.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Barone MA, et al. Summary report and preliminary recommendations from the Invitational Conference on USMLE Scoring (InCUS), in Invitational Conference on USMLE Scoring (InCUS) Burlington, VT. 2019;p. 20.

- 2.Tackett S, et al. Student well-being during dedicated preparation for USMLE Step 1 and COMLEX Level 1 exams. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):16–16. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-03055-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dyrbye LN, et al. Medical school strategies to address student well-being: a national survey. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):861–868. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dyrbye LN, et al. A multi-institutional study exploring the impact of positive mental health on medical students’ professionalism in an era of high burnout. Acad Med. 2012;87(8):1024–1031. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825cfa35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Humphrey HJ, Woodruff JN. The pass/fail decision for USMLE Step 1-next steps. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2022–2023. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Quek TT, et al. The global prevalence of anxiety among medical students: a meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(15). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Dunn LB, Iglewicz A, Moutier C. A conceptual model of medical student well-being: promoting resilience and preventing burnout. Acad Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):44–53. doi: 10.1176/appi.ap.32.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward PJ. Influence of study approaches on academic outcomes during pre-clinical medical education. Med Teach. 2011;33(12):e651–e662. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.610843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cipra C, Muller-Hilke B. Testing anxiety in undergraduate medical students and its correlation with different learning approaches. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0210130. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0210130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hattie JAC, Donoghue GM. Learning strategies: a synthesis and conceptual model. NPJ Sci Learn. 2016;1:16013. doi: 10.1038/npjscilearn.2016.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newble DI, Entwistle NJ. Learning styles and approaches: implications for medical education. Med Educ. 1986;20(3):162–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1986.tb01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schumacher DJ, Englander R, Carraccio C. Developing the master learner: applying learning theory to the learner, the teacher, and the learning environment. Acad Med. 2013;88:1635–1645. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a6e8f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Litman JA. Interest and deprivation factors of epistemic curiosity. Personality Individ Differ. 2008;44(7):1585–1595. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2008.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richards JB, Litman J, Roberts DH. Performance characteristics of measurement instruments of epistemic curiosity in third-year medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2013;23(3):355–363. doi: 10.1007/BF03341647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlyne DE. A theory of human curiosity. Br J Psychol. 1954;45(3):180–191. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8295.1954.tb01243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chou CM, Kellom K, Shea JA. Attitudes and habits of highly humanistic physicians. Acad Med. 2014;89(9):1252–1258. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duckworth A, Gross JJ. Self-control and grit: related but separable determinants of success. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2014;23(5):319–325. doi: 10.1177/0963721414541462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isenberg GA, et al. The relationship between grit and selected personality measures in medical students. Int J Med Educ. 2020;11:25–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Lee DH, Reasoner K, Lee D. Grit: what is it and why does it matter in medicine? Postgrad Med J. 2023;15;99(1172):535–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Jumat MR, et al. Grit protects medical students from burnout: a longitudinal study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20(1):266. doi: 10.1186/s12909-020-02187-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller-Matero LR, et al. Grit: a predictor of medical student performance. Educ Health (Abingdon) 2018;31(2):109–113. doi: 10.4103/efh.EfH_152_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park D, et al. Fostering grit: perceived school goal-structure predicts growth in grit and grades. Contemp Educ Psychol. 2018;55:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee D, et al. The relationships between grit, burnout, and demographic characteristics in medical students. Psychol Rep. 2022; Apr 14:332941221087899. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Wilkinson T. Pass/fail grading: not everything that counts can be counted. Med Educ. 2011;45(9):860–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LePine JA, LePine MA, Jackson CL. Challenge and hindrance stress: relationships with exhaustion, motivation to learn, and learning performance. J Appl Psychol. 2004;89:883–891. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.89.5.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brenneisen Mayer F, et al. Factors associated to depression and anxiety in medical students: a multicenter study. 2016;16(1):472–6920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Biggs JC. The revised two-factor Study Process Questionnaire: R-SPQ-2F. Br J Educ Psychol. 2001;71:133–149. doi: 10.1348/000709901158433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lauriola M, et al. Epistemic curiosity and self-regulation. Personality Individ Differ. 2015;83:202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2015.04.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Binu KG, et al. Influence of epistemic curiosity on the study approaches of first year engineering students. Procedia Comput Sci. 2020;172:443–451.

- 30.Richards JB, Litman JA, Roberts DH. Performance characteristics of measurement instruments of epistemic curiosity in third-year medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2013;23:355–363. doi: 10.1007/BF03341647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Musumari PM, et al. Grit is associated with lower level of depression and anxiety among university students in Chiang Mai, Thailand: a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(12):e0209121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0209121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilliard RI. How do medical students learn: medical student learning styles and factors that affect these learning styles. Teach Learn Med. 1995;7(4):201–210. doi: 10.1080/10401339509539745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen DR, et al. Student perspectives on the “Step 1 Climate” in preclinical medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):302–304. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Girard AO, et al. US medical student perspectives on the impact of a pass/fail USMLE Step 1. J Surg Educ. 2022;79(2):397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mott NM, Kercheval JB, Daniel M. Exploring students’ perspectives on well-being and the change of United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1 to pass/fail. Teach Learn Med. 2021;33(4):355–365. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2021.1899929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cangialosi PT, et al. Medical students’ reflections on the recent changes to the USMLE Step exams. Acad Med. 2021;96(3):343–348. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller BM, et al. Can a pass/fail grading system adequately reflect student progress? Virtual Mentor. 2009;11(11):842–851. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2009.11.11.ccas2-0911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baniadam K, et al. The impact on medical student stress in relation to a change in USMLE Step 1 examination score reporting to pass/fail. Med Sci Educ. 2023;33:401–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Blamoun J, Hakemi A, Armstead T. Perspectives on transitioning Step 1 of the United States Medical Licensing Examination to a pass/fail scoring model: defining new frameworks for medical students applying for residency. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2021;12:149–154. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S296286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pascarella L. USLME Step 1 scoring system change to pass/fail-perspective of a clerkship director. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(12):1096–1098. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salehi PP, Azizzadeh B, Lee YH. Pass/fail scoring of USMLE Step 1 and the need for residency selection reform. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2021;164(1):9–10. doi: 10.1177/0194599820951166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Willett LL. The impact of a pass/fail Step 1 — a residency program director’s view. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(25):2387–2389. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2004929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pontell ME, et al. The change of USMLE Step 1 to pass/fail: perspectives of the surgery program director. J Surg Educ. 2021;78(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2020.06.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kracaw RA, et al. Predicting United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 2 clinical knowledge scores from previous academic performance measures within a longitudinal interleaved curriculum. Cureus. 2021;13(9):e18143. doi: 10.7759/cureus.18143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shih AF, Maroongroge S. The importance of grit in medical training. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(3):399. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00852.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sternszus R, Saroyan A, Steinert Y. Describing medical student curiosity across a four year curriculum: an exploratory study. Med Teach. 2017;39(4):377–382. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2017.1290793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salles A, Cohen GL, Mueller CM. The relationship between grit and resident well-being. Am J Surg. 2014;207(2):251–254. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adashi EY, Ahmed AH, Gruppuso PA. The importance of being curious. Am J Med. 2019;132(6):673–674. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coda JE. Third-party resources for the USMLE: reconsidering the role of a parallel curriculum. Acad Med. 2019;94(7):924. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burk-Rafel J, Santen SA, Purkiss J. Study behaviors and USMLE Step 1 performance: implications of a student self-directed parallel curriculum. Acad Med. 2017;92(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 56th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S67-S74. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Scouller K. The influence of assessment method on students’ learning approaches: multiple choice question examination versus assignment essay. High Educ. 1998;35(4):453–472. doi: 10.1023/A:1003196224280. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Choudhary A, et al. Impact of pass/fail USMLE Step 1 scoring on the internal medicine residency application process: a program director survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(8):2509–2510. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05984-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deitte LA, et al. The pass/fail United States Medical Licensing Examination Step 1: impact on radiology residency selection. J Am Coll Radiol. 2021;18(3 Pt A):435–37. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Drake E, Phillips JP, Kovar-Gough I. Exploring preparation for the USMLE Step 2 exams to inform best practices. PRiMER. 2021;5:26. doi: 10.22454/PRiMER.2021.693105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–529. doi: 10.1111/joim.12752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.