Abstract

Feedback from educators to learners is considered an important element of effective learning in medical school. While early studies were focused on the processes of providing feedback, recent work has showed that factors related to how learners receive feedback seems to be equally important. Considering that the literature on this topic is new in medical education, and studies are diverse and methodologically variable, we sought to conduct a scoping review to map the articles on receptiveness to feedback, to provide an overview of its related factors, to identify the types of research conducted in this area, and to document knowledge gaps in the existing literature. Using the Joanna Briggs Institute scoping review methodology, we searched four databases (CINAHL, Ovid, PubMed, and Web of Science) and screened 9120 abstracts, resulting in 98 articles for our final analysis. In this sample, 80% of studies on the feedback receiver were published in the last 10 years, and there is a vast variation in the studies’ methodologies. The main factors that affect medical students’ receptiveness to feedback are students’ characteristics, feedback content, educators’ credibility, and the learning environment. Feedback literacy is a very recent and rarely used term in medical education; therefore, an important area for further investigation. Lastly, we identified some gaps in the literature that might guide future research, such as studying receptiveness to feedback based on academic seniority and feedback literacy’s long-term impacts on learning.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-023-01858-0.

Keywords: Feedback, Medical education, Medical school, Scoping review, Receptiveness to feedback, Feedback literacy

Introduction

Feedback, broadly defined as the information provided to make adjustments in performance, has been extensively studied and long been used in different fields (i.e. education, engineering, music, medicine) [1–4]. In education, feedback seems to have an impact on improving students’ learning; however, the magnitude of this impact cannot be understood uniformly across different fields due to the heterogeneity of types of feedback, effects, and the settings where it occurs [3, 4]. Within medical education, feedback from educators to learners is considered an important and essential element of effective learning in clinical settings [5, 6]. Early studies were focused on the processes of providing feedback (i.e. guiding supervisors on ways to best deliver feedback to learners) [3, 7–9]. Recently, work within this field has expanded to include a focus on the process of receiving feedback, given the recognition that feedback is a complex exchange of information that goes beyond the delivery process [10, 11]. While the process of delivering feedback is essential, receiving feedback, and the context and the culture where the feedback occurs seems to be equally important to optimize the learners’ use of feedback. The learners who receive the feedback must respond to it, and the environment in which the feedback occurs also plays an important role in learning effectiveness [12–15]. Therefore, some current authors have incorporated learners’ receptiveness to feedback into the concept of feedback, and there has been an increase in studies exploring the factors related to it, such as the influences of emotional reactions, educators’ credibility, learners’ self-assessment, learners’ self-esteem, and previous feedback experiences [3, 5, 16–18].

The term “Feedback Literacy” has been used to describe the process in which a learner receives, comprehends, accepts, and makes use of feedback, and is increasingly being adopted within the medical education research field [19–21]. Learners achieve feedback literacy in different ways, depending on the context, curricula, previous feedback experiences, and their own personal characteristics [19]. Some studies outline how to teach feedback literacy to students [19, 20], whereas others identify that activities necessary to support the development of students’ feedback literacy should be part of the curriculum in the early years of a medical educational program [12, 21].

Another current discussion in this field is regarding important elements related to receptiveness to feedback and to the environment where feedback occurs. It is common for medical students to perceive feedback as a top-down process, even when they might have some social power in the clinical learning [22]. While some authors suggest that power asymmetry between learners and instructors can impact feedback [14], others have identified that there are contexts where medical students describe having some social power in the clinical learning environment, and view themselves as active negotiators during the process to improve their clinical learning [22]. These are important observations as it demonstrates, depending on context, that it is possible for medical students to actively engage in and assume ownership of, at least, part of their learning, even in a training environment that is hierarchically organized. Moreover, some studies highlighted how the learning culture influences the receptiveness to feedback by defining the expectations for educators and learners, by establishing rules, and by directing attention toward certain parts of the professional performance [13, 18, 23, 24]. Even when the educator is able to deliver the feedback, and the learner is able to engage with it, the learning culture might impact the result of this interaction. Thus, it is essential to understand how the learning culture in each specific professional context influences the processes of feedback delivery and receipt.

In conclusion, previous studies indicated that it is important to understand the learners’ feedback experiences in each specific learning context, in order to adequately deliver and receive feedback. The learners who receive the feedback must respond to it. Thus, it is important to empower them with skills that help them to take charge of their own learning in order to adapt to the different quality of feedback received. Medical school is a unique context representing one of the medical trainee’s first experiences in the medical field and in the community of practice. The underlying values that shape how feedback is positioned within medicine’s learning culture might be unique and different compared to the later postgraduate years of medical education (i.e. medical residency). Although the delivery of feedback has long been studied, the literature on receptiveness to feedback is new, especially within the medical undergraduate education field. Articles on this topic are diverse and methodologically variable. Moreover, we could not find a scoping review about receptiveness to feedback after a preliminary search on CINAHL and Ovid Databases, even with no restriction regarding geographic location, original language, and date of publication. Therefore, our scoping review intends to map the current literature in medical students’ receptiveness to feedback, to provide an overview of its related factors, to identify the kind of research conducted in this field, and to find gaps in the existing literature to guide future research.

Review Questions

Our scoping review was guided by the primary research question: What is known about undergraduate students’ receptiveness to feedback in medical schools? The sub questions were:

How do undergraduate students perceive the feedback received in medical schools?

What are the factors related to undergraduate students’ receptiveness to feedback while in medical school?

How has feedback literacy been defined and taught in medical schools?

What are the gaps in our knowledge and understanding about undergraduate students’ receptiveness to feedback in medical schools?

Inclusion Criteria

Participants

For this scoping review, we will be focusing on undergraduate medical students enrolled in medical school to best answer our research questions. We used the terms undergraduate students in medical school, undergraduate medical students, and medical students interchangeably to refer to students enrolled in a medical school program to pursue a medical degree. Prior research indicates that maturity plays an important role in receiving feedback [25, 26]. Junior students (i.e. medical students), when compared to seniors (i.e. medical residents), may have a lower capacity to evaluate and change their learning behaviours; therefore affecting their ability to receive, accept, and make use of the feedback received. We therefore chose to focus on undergraduate medical students in order to minimize the maturity gap between learners enrolled in medical school and medical residents, to avoid the differences in pedagogy in other health professions education, and to best understand what is known about the topic specifically in the medical school’s context. If the study included medical students, as well as medical residents or other health professions, it was deemed to meet the inclusion criteria. Studies were excluded if exclusively reporting on a non-medicine trainee population or medical residents.

Concepts

Three core concepts (feedback, receptiveness to feedback, and feedback literacy) were identified and defined to guide us in the extension and breadth of this review.

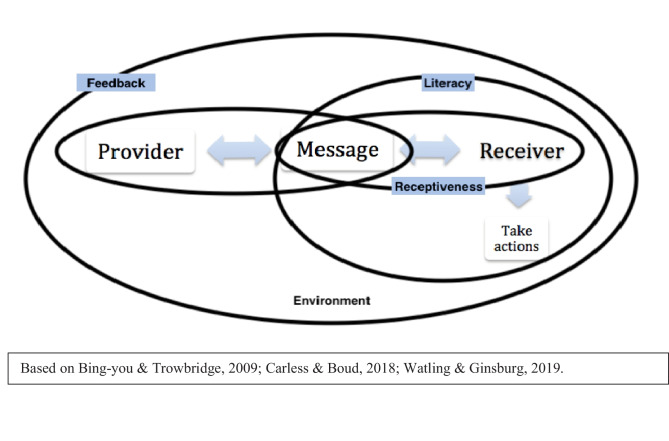

We defined feedback as a complex exchange of information between an educator and a learner that allows the learner to understand how they are performing, and to empower them to develop a plan for improvements [4, 19, 27] This interaction depends on the educator (the feedback provider), the learner (the feedback receiver), and the information exchanged (the message); and this whole process is shaped by the learning environment culture where feedback occurs (i.e. medical schools) [18, 23]. The feedback delivered by physician educators was chosen to minimize the influences in receptiveness to feedback due to the variation in feedback givers’ training, and the differences in pedagogy and clinical supervision in other health professions. Therefore, studies exploring feedback delivered exclusively by other students, residents, patients, or other health professionals were not included in this review.

We defined receptiveness to feedback as how medical students perceive the feedback received, how they react to it (i.e. emotionally), and how they decode and appraise the information [6, 19]. We did not consider a student’s receptivity to feedback and the learning environment as two separate components; instead, the learning environment was considered part of one of the factors affecting receptivity. Therefore, studies exploring the feedback learning culture were considered in this review when associated with receptiveness to feedback.

Lastly, we defined feedback literacy as the process which learners receive, comprehend, accept, and make use of feedback [20, 21]. In our view, feedback literacy goes beyond receptiveness to feedback because it involves taking actions. Therefore, feedback literacy is a broader and more recent term in the field of medical education that includes 'receptiveness to feedback'. After consultation with the health science librarian involved in this project, we concluded that we should include both concepts (receptiveness to feedback and feedback literacy) so we would not exclude articles published before the term feedback literacy has been defined in medical education, nor we would exclude articles that use the term feedback literacy as a way to discuss receptiveness to feedback.

The Fig. 1 illustrates our three main concepts and the interactions among the educator (the feedback provider), the learner (the feedback receiver), the information exchanged (the message), and the learning environment.

Fig. 1.

Representation of our three main core concepts: feedback, receptiveness to feedback, and feedback literacy

Context

We included studies that recruited participants from or were conducted within the context of a medical school, including different learning contexts such as classrooms, laboratories, and clinical settings. The environment where learning occurs influences the receptiveness to feedback, and that a unique learning culture exists that is inherent to medical education [10, 18]. Therefore, we decided to exclude studies that exclusively reported on another setting than the medical schools, so we could focus on the medical learning context.

Following recommendations of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Manual for Evidence Synthesis, there was no restriction regarding geographic location and original language to avoid limitations in answering our research questions [28].

Types of Sources

As recommended by the JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis [28], our scoping review considered all studies designs among peer-reviewed publications, including systematic reviews, meta-analysis, quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods approach, letters and opinions. We followed JBI recommendation to not restrict the type of source because the literature on receptiveness to feedback is new within the medical undergraduate education field, so we believe it was important to map all the evidence.

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the JBI methodology for scoping reviews [28]. As part of the process for developing the review protocol, consultations were completed with all the authors of this article, and the protocol items were discussed before starting the search for sources of information.

Scoping Review Rationale

The JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis recommends that scoping reviews should be used to examine the extension or breadth of a topic in the literature, to map and summarize research findings, and to identify gaps that could be used to inform future research [28]. Therefore, scoping reviews are especially useful for examining emerging topics and less specific questions. In contrast to systematic reviews for example, scoping reviews do not aim at assessing the quality of the evidence; thus, an appraisal of studies methodological limitations or risk of bias is, usually, not performed.

Considering the broad nature of our main research question and that the literature on receptiveness to feedback is new within the medical undergraduate education field, a scoping review is the most suitable methodology to achieve the study objectives. We aim at examining the extension of this topic, to map and summarize our findings following our research sub questions, and to identify gaps in the literature to inform future researches in the medical education field.

Search Strategy

We followed the three-step strategy described by the JBI methodology [28]. We aimed at being as comprehensive as possible by locating both published and unpublished studies. In consultation with a health science librarian at McMaster University (Canada), we defined concepts and chose keywords for searching the articles. See Supplementary file I – Concepts and Keywords. Next, we defined the databases (CINAHL and Ovid Databases) for the initial search based on the librarian suggestions and a limited search using our concepts and keywords. We also looked at the text words contained in the title and abstracts of relevant articles to ensure the concepts and keywords where in alignment with the objectives of our scoping review. Based on the results of this initial search, we decided to expand the full search using two other databases (PubMed and Web of Science). Lastly, we checked the reference lists of the articles selected from full-text to include additional sources. We did not limit our search by language or dates to minimize limitations in answering our research questions. Our search was conducted between September and December 2021.

Source of Evidence Screening and Selection

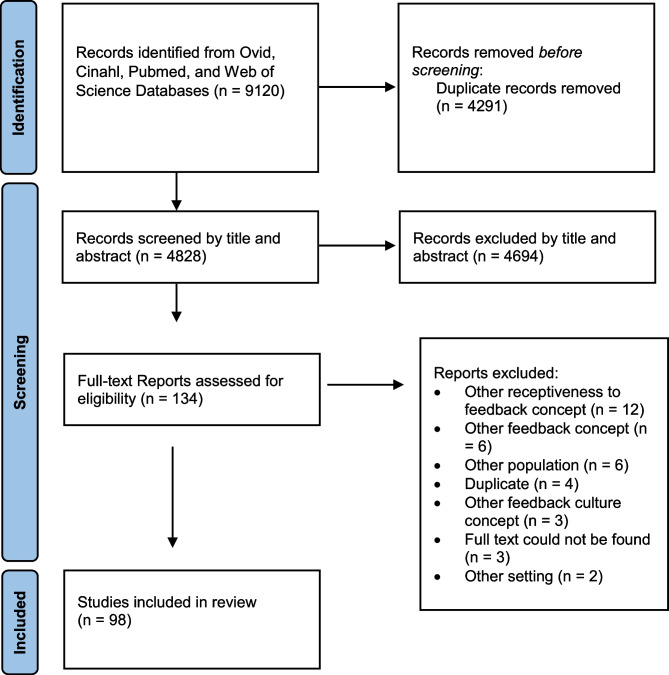

We used Covidence, a web-based software review tool that facilitates the process of screening, selection, and data extraction. First, a pilot process was conducted with five reviewers (LC, CT, DW, AR, AH). Fifty abstracts were randomly selected using the concepts and keywords defined. The reviewers were asked to screen the titles and abstracts. We had 4 conflicts (8%), which was considered acceptable. Next, we searched the initial databases (CINAHL and Ovid Databases) for titles and abstracts using the concepts and keywords. After removing the duplicates, we found 3074 abstracts to be screened. Then, we searched the two other databases (PubMed and Web of Science), and we added 1754 abstracts, after removing the duplicates. Therefore, a total of 4828 abstracts were selected for the screening process. The first author (LC) and one independent reviewer (CT, DV, AR, or AH) screened all of the abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. We try to resolve the conflicts through discussions among the reviewers. If the conflict was not resolved, the vote of a third reviewer was taken into consideration. One hundred thirty-four full-texts were selected and assessed for eligibility by the first author (LC) and one independent reviewer (CT, DV, AR, or AH) using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We had eight conflicts that were resolved by a third reviewer. At the end, 98 full articles were included for data extraction. The reasons for exclusion were: different concepts other than the ones defined for this study, different population or setting, and duplicates. There were no full texts for three of the abstracts because they were published only as abstracts (i.e. research forum). See Supplementary file II for the complete list of sources excluded following full-text review with primary reasons for exclusion.

The results of the search and the study inclusion process is presented in a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses extension for scoping review [29]. See Supplementary file III.

Data Extraction

The first author (LC) and three volunteer students (CT, DV, and AR) extracted the data from the articles included in this scoping review using the Covidence web-based software. We developed a data extraction template that was discussed with the volunteer students and all the authors of this scoping review before starting the extraction process. The template was not modified after the process of extracting data started. The data extracted included specific details about the characteristics of the studies (i.e. country where the study was conducted, year, type of article, methodology, aim of the study, population, context, data collection method, study intervention), definition of the concepts being considered in this study (i.e. feedback, receptiveness to feedback, culture of feedback), the feedback provider, the type of feedback (i.e. written, oral, computer), the focus of the feedback (i.e. communication skills, procedure skills), how the impact of the feedback was evaluated (i.e. learners’ reaction, difference in learning), the medical students’ overall perceptions about the feedback received (i.e. positive, negative, neutral), the factors that influence the receptiveness to feedback and the learning culture of the receptiveness to feedback, the definition of feedback literacy, how feedback literacy has been taught in medical schools, and the gaps in the topic that were suggested by the authors of the included articles. Data were extracted directly from the articles using passages quoted from the text. See Supplementary File IV - Data Extraction Instrument Template. Conflicts were all resolved through discussions among the reviewers.

Data Analysis and Presentation

Results were classified under main conceptual categories: how medical students see feedback, factors related to receptiveness to feedback, how feedback literacy has been defined and taught in the medical undergraduate program, and the gaps in the literature. Moreover, since this is a new topic in the literature, we presented the number of sources of evidence published in each year, and we mapped the type of studies and methodologies used and the countries where studies were conducted. For each category reported, a clear explanation was provided. A descriptive summary accompanied the charted results to describe how the results are related to the review objectives and research question.

We conducted two separate directed content analysis [30] of the studies included in this scoping review in order to better answer our two sub questions 1. How do medical students perceive the feedback received in medical schools? 2. What are the factors related to medical students’ receptiveness to feedback? We chose the directed content analysis approach because we used prior knowledge and research about the phenomenon to make predictions about our variables of interest. We based our analysis on previous studies that explored: the type (i.e. constructive, specific), the structure (i.e. oral, written), and the timing of feedback; some factors related to receptiveness to feedback (i.e. emotional reactions, educators’ credibility, learners’ self-assessment, learners’ self-esteem); and the influence of the context and the culture where the feedback occurs [6, 7, 19, 26, 27, 31].

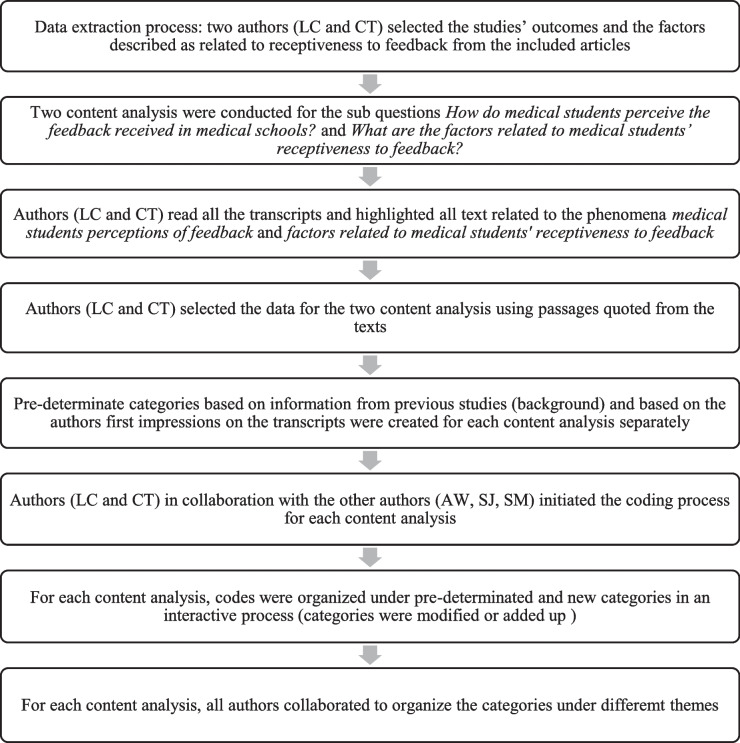

Using only the texts selected in the data extraction phase, two of the authors (LC and CT) highlighted and extracted all text related to the phenomena (medical students perceptions of feedback and factors related to medical students' receptiveness to feedback) for each of the sub questions separately. The data for the content analysis was extracted using passages quoted from the texts. For example, the quote “We conclude that the positively framed feedback group was more satisfied (…) than the group in the negatively framed condition” was extracted from the article by van de Ridder et al. [32] to answer the sub question What are the factors related to medical students’ receptiveness to feedback? Then, the authors (LC and CT) in collaboration with the other authors (AW, SJ, SM) initiated the coding process for each content analysis. Next, we defined the predetermined categories for each sub question. The predetermined categories were based on information from previous studies (background) and our first impressions on the transcript. The pre-categories will be described below in the Results section. We used an unconstrained matrix of analysis, meaning that the predetermined categories were modified or added up as the interactive process of coding continued. [33] For each content analysis, codes were organized under predetermined and new categories. Lastly, we analyzed the results of the coding process, and organized all the categories in different themes in order to express underlying meanings found in two or more categories. See Fig. 2 for Directed content analysis approach diagram and Supplementary file V for examples of data analysis from text quotes to codes.

Fig. 2.

Directed content analysis approach diagram. Diagram based on Hsieh and Shannon [35]. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288

Trustworthiness of the findings was enhanced by providing a detailed description of the analysis process, close supervision of the whole process by all the authors, and engagement of a panel of experts that supported category production and coding issues [34, 35].

Results

A total of 98 articles were included in the scoping review, after excluding 36 articles that did not meet our inclusion criteria, were duplicates, or unobtainable. See Fig. 3 – PRISMA flow diagram. A complete list of included articles can be found in the Supplementary file VI.

Fig. 3.

PRISMA flow diagram

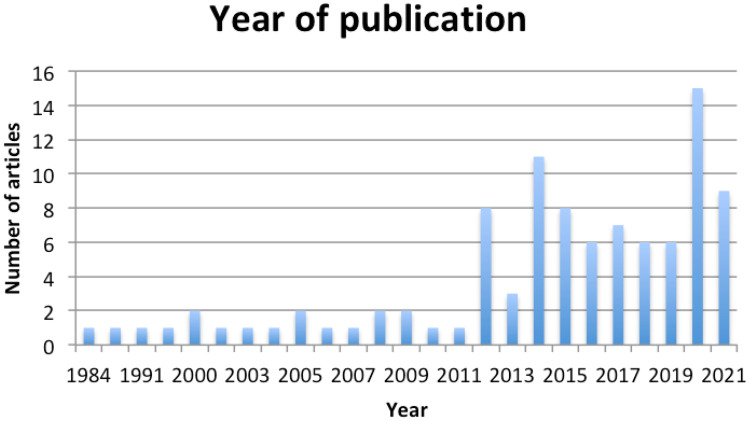

Characteristics of the Articles

Publication on the topic of receptiveness to feedback in medical school has increased in the last 10 years. See Fig. 4 – Year of Publication. These results reinforce our initial findings that current authors have incorporated learners’ receptiveness to feedback into the concept of feedback, and there has been an increase in studies exploring the factors related to it.

Fig. 4.

Year of Publication

In alignment with our inclusion criteria for participants (medical students) and setting (medical schools), we found that most articles were published in journals focused on health sciences education, and more specifically, medical education.

When looking at the country in which the study was conducted, most studies were completed with samples of participants from: United States (30 articles), followed by Canada (17 articles), and then England (11 articles). Most studies were conducted in North America (47 articles), followed by Europe (25 articles), and then Asia (17 articles). Only a small number of additional studies were conducted in Oceania [12, 20, 36, 36–39], Africa [40, 41], and South America [42]. All studies but one were conducted and published in English; the exception [43] was published in Korean but translated to English by one of the reviewers (LC).

There was a vast variation in study methodologies. Most articles were original articles (79 articles), followed by review articles (12 articles), letters and opinions (5 articles), and commentaries (2 articles). Forty-two studies included some kind of intervention, such as feedback training/workshops for learners, a different feedback format (encounter cards, video records), or specific tasks (peg transfer in surgery box, surgical knot). With respect to design, of those articles that included an evaluation or research component, designs included cross-sectional studies (23 articles), different approaches for qualitative studies (24 articles), or review articles (12 articles) [44]. Two studies were classified as unknown methodologies because neither we could identify the methodology used nor the authors of the study mentioned it. It is out of the scope of this review to assess the quality of the studies. The data collection of choice was mostly survey (33 articles) used in cross-sectional and mixed-method approaches, followed by individual interviews (11 articles) and focus group (8 articles) used in qualitative studies. See Table 1 – Studies’ Map

Table 1.

Studies’ Map

| Journal of Publication | Number of articles |

|---|---|

| Medical Education | 16 |

| Medical Teacher | 13 |

| Academic Medicine | 7 |

| Advances in Health Sciences Education | 7 |

| Others | 48 |

| Origin of Studies (by Continent) | Number of articles |

| North America | 47 |

| Europe | 25 |

| Asia | 17 |

| Oceania | 6 |

| Africa | 2 |

| South America | 1 |

| Methodology | Number of articles |

| Quantitative Studies - Observational | 26 |

| Cross-sectional | 23 |

| Cohort | 3 |

| Qualitative Studies | 24 |

| Qualitative study (design not specified) | 11 |

| Grounded Theory | 10 |

| Exploratory Qualitative | 1 |

| Interpretive Description | 1 |

| Qualitative Description | 1 |

| Reviews | 12 |

| Review (design type not specified) | 8 |

| Scoping review | 2 |

| Thematic review | 1 |

| Narrative review | 1 |

| Mixed Methods | 9 |

| Quantitative Studies - Experimental | 9 |

| Randomized controlled trial | 7 |

| Time-series repeated-measures | 1 |

| Experimental (not specified) | 1 |

| Quantitative Studies - Quasi-experimental | 8 |

| Quasi-experimental (not specified) | 7 |

| Static-group comparison design | 1 |

| Letters/Commentary | 7 |

| Unknown | 2 |

aStudy’s methodology classified according to the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine University of Oxford’s directions

Population and Context

The population of most studies was medical students exclusively, without including other type of learners (80 articles). There was a large variation in the number of participants across studies (from 7 to 520 participants). This was expected due to the variation in methodologies. Most studies were situated in medical schools, exclusively (83 articles). Other populations and contexts included, in addition to medical school and students, were: midwifery, veterinary, and nursing programs, medical residents, and practicing physicians.

Feedback Mapping

In most studies, the feedback was provided exclusively by a physician (71 articles). When looking at the type of feedback that has been studied, most articles explored written and oral feedback combined (20 articles), followed by exclusively oral (20 articles) or written (15 articles) feedback. The type of feedback provided was not specified in 33 articles. Most studies focused on analysing the feedback given regarding clinical skills (i.e. history and physical examination, diagnosis, and treatment), or a combination of clinical skills and communication skills (i.e. communication with patients). Only five studies focused on analysing the feedback given in classrooms. Lastly, the impact on learners of the feedback received was mostly analysed through learners’ perceptions (e.g. whether the feedback received motivated them to improve their skills). See Table 2 – Feedback Mapping

Table 2.

Feedback Mapping

| Feedback Provider | Number of Articles |

|---|---|

| Exclusively Physician | 71 |

| Physician and Self-reflection | 6 |

| Physician and Residents/Student | 9 |

| Educators (not specified) | 3 |

| Combination (physicians, residents, students, self-reflection, and/or other health professionals) | 9 |

| Type of Feedback | Number of Articles |

| Not specified | 33 |

| Written and Oral | 26 |

| Oral | 20 |

| Written | 15 |

| Combination of the types above | 4 |

| Focus of the feedback | Number of Articles |

| Clinical skills | 32 |

| Not specified | 29 |

| Communication and Clinical skills | 10 |

| Communication skills, Procedural skills, and Clinical skills | 8 |

| Communication skills | 5 |

| Procedural skills | 5 |

| Assessments | 4 |

| Othersa | 5 |

| Feedback Evaluation | Number of Articles |

| Learners' perceptions | 59 |

| Not specified | 16 |

| Learners' reactions combined with Difference in learning (pre-post tests) and/or Changes in behaviour (pre-post perceptions) | 23 |

aOthers: biochemistry, case presentations, and Problem-Based Learning (PBL) sessions.

Factors Related to Medical Students’ Receptiveness to Feedback

Our content analysis resulted in eight pre-determinated categories (i.e. emotional reactions, maturity, feedback content, timing, ways to deliver, type of feedback, credibility, and environment) that were modified or added up as the interactive process of coding continued. We started with eight pre-determinated categories: emotional reactions (e.g. distress, fear, relief), maturity, feedback content (e.g. constructive, detailed, positive, focused), timing (e.g. immediate, timely, during), ways to deliver (e.g. one-on-one, triangulation, standardize), type of feedback (e.g. oral, written), credibility, and environment (e.g. supportive, comfortable, safe). Students’ characteristics was added to include codes related to students’ characteristics related to learning motivation that could affect receptiveness to feedback (e.g., autonomy, confidence, engagement, mindset, initiative). Abilities for students’ self-assessment was considered a separate category due to the number of codes related to students’ abilities to evaluate themselves (e.g., self-awareness, self-efficacy, self-perception, self-reflection). Impact of the feedback means areas where the feedback would have an impact, for example impact on students’ overall performance, non-technical skills only, changes in behaviour, or learning in general. Students’ perceptions of the feedback include codes representing whether students perceive the feedback, the way it was given to them, as important for their learning (e.g. feedback recognition, feedback expectations). Credibility was one of the pre-determinated categories split in two: feedback credibility (e.g. feedback based on direct observation, number of observations), and the feedback giver’s credibility (e.g. educator-student relationship, tutors engagement, trustworthiness, and whether feedback was given by a physician, medical student, or other health professional). Environment was another category split in two: learning environment (e.g. supportive, safe, healthy) and the culture of the country (e.g. social hierarchy, gender barrier). Lastly, we decided to add two categories related more specifically to the term feedback literacy: decoding feedback messages (e.g. feedback awareness, feedback language, being able to recognize the feedback) and seeking feedback (e.g. requesting feedback, student empowerment). At the end, we developed 376 codes that were grouped into 16 categories. The categories were then organized into five themes. Our themes were based on our core concepts of receptiveness to feedback and feedback literacy, and focused on the receiver (i.e. learner), the message (i.e. feedback information), and the feedback environment. See Table 3 - Factors related to medical students’ receptiveness to feedback

Table 3.

Factors related to medical students’ receptiveness to feedback

| THEMES and CATEGORIES |

|---|

| 1. Factors related to the students themselves |

|

a) Students’ characteristics (10.1%) b) Abilities for students’ self-assessment (7%) c) Students’ emotional reactions to feedback (3.7%) d) Students’ maturity (2.1%) |

| 2. Factors related to the feedback |

|

a) Feedback content (23.4%) b) Impact of the feedback (5.9%) c) Feedback credibility (5.6%) d) Timing of feedback (5.2%) e) Way feedback is delivered (5%) f) Type of feedback (4%) g) Students’ perceptions of the feedback (2.1%) |

| 3. Students’ perceptions of the feedback giver |

| a) Feedback giver’s credibility (12.5%) |

| 4. Factors related to the environment where feedback occurs |

|

a) Learning environment (4.2%) b) Culture of the country (2.4%) |

| 5. Factors related to feedback literacy |

|

a) Decoding feedback messages (3.7%) b) Seeking feedback (3%) |

aThe number in parenthesis refers to the percentage of codes for each category.

Our content analysis results support past findings that experiences of receiving feedback are influenced by multiple factors acting at multiple different levels from individual to environmental [6, 15, 16, 45]. The category Factors related to the feedback content received the greatest number of codes. According to our content analysis results, students receive feedback better when it is constructive, detailed, specific, and with suggestions for improvement. Inherent to our findings, the feedback giver’s credibility plays an important role in feedback receptivity. Feedback giver’s credibility was associated with a sense of trust, caring, and long-term relationship with students. Additionally, credibility was related to the quality of feedback (i.e. feedback was reassuring, and based on multiple and directed observations,). Moreover, under the category Students’ characteristics, we found that confidence, engagement, mindset, and self-motivation were elements frequently mentioned.

When looking at the codes associated to the environment where feedback occurs, we noticed that some of them referred to the learning environment (i.e. supportive, comfortable, and safe), and others were related to the culture of the country. We considered the culture of the country where the feedback occurs as a separate factor because we found some studies addressing the fact that the country cultural aspects per se may influence how feedback is perceived [46–48]. For example, it seems that in countries with larger power distance and lower individualism (i.e. Indonesia), feedback initiated by the supervisor (instead of the student) seems to be more acceptable than in countries with lower power distance and higher individualism culture (i.e. Netherlands) [46]. Other examples of culture differences between countries that could influence receptivity to feedback are the uncertainty avoidance (how the society deals with unpredictable situations), masculinity (gender role divisions), and long-term orientation (whether people focus efforts on the present or future) [46, 47]. Lastly, following the recent literature in feedback literacy, our content analysis identified factors related to Decoding feedback messages, such as recognizing the feedback and the feedback language, and participating in feedback literacy workshops. Additionally, being able to seek for feedback and feel empowered also seems to improve students’ receptivity to feedback.

Medical Students’ Perceptions of Feedback in Medical School

Most studies reported that the learners have a positive perception of the feedback received (61 articles). Only five studies reported that the learners have a negative perception. However, we have to take into consideration that the students’ perceptions were mostly influenced by the studies’ interventions that improved receptivity to feedback (e.g. workshops, lessons, technology tools). Our directed content analysis resulted in 6 pre-determinated categories (i.e. positive, negative, neutral, credible, useful, and helpful) that were modified or added up as the interactive process of coding continued. We eliminated four pre-determinated categories (neutral, credible, useful, and helpful). The pre-determine category positive perceptions was divided in three categories: positive feelings (e.g., encouraging, helpful, useful), positive content (e.g., constructive, effective, instructive), and positive timing (e.g., frequent, regular, timely). Negative perceptions was also divided in three categories: negative feelings (e.g. uncomfortable, intimidated, insulting), negative content (e.g. unspecific, undetailed, unclear), and negative timing (e.g. irregular, limited, scarce). We added two new categories based on students’ overall perception of the quality (e.g. positive, negative, varied) and the process (e.g. one-way, monologue, passive) of the feedback. At the end, we developed 126 codes that were grouped into 8 categories. The categories were then organized into three themes to reflect the medical students’ perceptions of feedback in medical schools. Perceptions of feedback are related to our core concept of receptiveness to feedback. See Table 4 - Medical students’ perceptions of feedback in medical school

Table 4.

Medical students’ perceptions of feedback in medical school

| THEMES and CATEGORIES |

|---|

| 1. Students’ Positive Perceptions |

|

a) Positive Feelings (25.4%) b) Positive Content (15.8%) c) Positive Timing (12%) |

| 2. Students’ Negative Perceptions |

|

a) Negative Content (14.2%) b) Negative Timing (7.1%) c) Negative Feelings (4.8%) |

| 3. Overall Perception |

|

a) Quality (15%) b) Process (5.5%) |

aThe number in parenthesis refers to percentage of codes for each category.

The category with the most number of codes was Students’ positive feelings towards the feedback received. These codes showed that learners perceive feedback as positive when they feel encouraged, helped, and they feel that the feedback is useful. On the other hand, the Negative feelings category shows that the learners perceive feedback as negative when they feel uncomfortable, intimidated, or insulted. Students also have a positive perception of the feedback depending on its content and whether it is constructive, effective, and instructive (Positive content category), as opposed to feedback that is unspecific, undetailed, and unclear (Negative content category). Moreover, the timing when feedback is given seems to influence students’ perceptions. Our codes showed that feedback that is frequent, regular, and timely was associated with positive perceptions (Positive timing category), while feedback that is irregular, limited, and infrequent was related to negative perceptions (Negative timing category). Lastly, our results included the categories Quality and Process. Our codes showed that the quality of the feedback received is an important factor in students’ perceptions about it, but we couldn’t identify how the quality would influence the medical student’s perceptions (i.e. positively, negatively) because the studies either provided different specifications for the term quality or they did not specified it at all. Moreover, most studies described feedback as a one-way process, and this way of process seems to influence negatively students’ perceptions of the feedback received, reinforcing previous findings in the literature [16, 49, 50].

Feedback Literacy

Only four studies defined feedback literacy, and they were all articles published within 2017 and 2020 [20, 25, 51, 52], reinforcing our findings that feedback literacy is a very recent term in medical education. We found four studies that described how feedback literacy has been taught in medical schools [20, 25, 53, 54]. They were all pilot studies in which the interventions included workshops from educators to students (one of them combined to reflective logs), or longitudinal coaching. However, two of these studies did not provide a definition for the term feedback literacy, although the interventions were done to help students to receive and make use of feedback [53, 54]. Overall, students that participated in these programs seemed more engaged in seeking and receiving feedback, were more aware of the feedback received, and had an increase in self- perceived confidence and skill in accepting and acting on feedback.

Gaps Described in the Literature

When looking at the data by year of publication, we noticed that more gaps were identified after 2010. This was not a surprise, considering the increase in publication about receptiveness to feedback in the last 10 years. Moreover, before 2010, articles focused their recommendations on investigating feedback provider characteristics or feedback content to improve feedback effectiveness. After 2010, authors started to suggest further research to study the feedback receiver characteristics, the students’ actions due to the feedback received, the relationship between educator and learner, and the context or culture influences. This change in gaps in the reviewed literature suggests a shift of research focus from providing feedback to receiving feedback and the role of the environment in learning effectiveness. However, most gaps are focused on one element of the feedback concept (i.e. provider, or the message, or the receiver, or the feedback actions, or the environment). Only more recently, some authors started to suggest that further investigations should focus on the relationships between provider, receiver, and environment at the same time in order to get a more complete understanding of the feedback process. Some authors identified gaps in methods and methodologies. They suggested a need for more rigorous methodologies, more qualitative methods of data collection and analysis (i.e. focus group, interviews, content analysis), and more quantitative studies that are not observational ones (e.g. randomized educational trials). These needs were supported by our results since we identified that most studies were cross-sectional ones, and little was described about the qualitative studies designs and reviews’ approaches. For an overall view of our results, we summarized the gaps in the literature according to the elements described in our core concept of feedback (i.e. provider, the message, receiver, actions taken, and environment). See Table 5 – Summarized gaps by feedback concept elements.

Table 5.

Summarized gaps by feedback concept elements

| Provider | Message | Receiver | Actions | Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Follow-up studies on faculty development Feedback content when giving feedback Comparison with performance standards Tutors practices based on gender, attendance of faculty development workshops, academic qualifications, and perceptions of the value of feedback. |

Positive versus negative messages Technology useful for giving and receiving feedback easily Efficient methods of written feedback Effectiveness of written summary of the feedback discussion To investigate the content of feedback and its relation with the perceived instructiveness of feedback |

Different year groups Student’s perception Emotional responses Self-Regulation Theory, and differences in the receipt and use of feedback. Feedback-seeking behaviors of students Difference by medical specialty and professions Recognition of the feedback provided Feedback negative impact on students Students’ perceptions of feedback providers characteristics related to feedback acceptance Credibility of feedback Influences in trainees’ response Feedback and self-esteem Interventions for receptivity to feedback |

Making use of feedback Decision to develop from the feedback The impact of goal setting and other aspects of self-regulated learning Feedback and trainees’ future performance Long-term efficacy and effects of feedback Impact of the feedback Guidance on how to utilize the feedback Using feedback episodes in their future learning Moving from novice to expert: responsibility for learning Supporting their use of feedback. |

Changes in the learning culture and effect on the quality of feedback Workplaces and their influence on feedback Cultural factors and hierarchical system of medical education Assessment and improvement of culture of feedback in an organization Elements of effective feedback in different cultures Elements of open and safe interaction in the feedback conversation Effects of context on feedback incorporation Influences of culture in implementing feedback processes in different countries Influence of culture on the process and acceptance of feedback |

| Relationship provider-receiver-environment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tutors/students perspectives at the same time Feedback from students to faculty to understand feedback conversation A need for better and complete understanding of the process of giving, receiving, interpreting, and using feedback as a basis for real progress toward entrustment decisions Educational alliances Relationship (educator and learner) and the conditions that facilitate effective and meaningful evaluation |

Discussion

Our results highlighted that research focusing on the feedback receiver is very recent in the medical education field. In a scoping review on feedback in general, Bing-You et al. [55] analysed data from 1980 to 2015, and they found that 52% of the articles were published between 2010 and 2015. Their scoping review was different from ours, since it included a broader topic, population, and setting, different search terms and search years, and they excluded non-English articles and the grey literature. Still, our results not only reinforced that publication in this topic has increased in the last ten years, but also supported their findings in feedback mapping and studies’ methodology. We found a vast variation in studies’ methodologies, an abundance of observational descriptive studies (e.g. survey, qualitative), and a lack of experimental studies. Therefore, most studies gave us an overall picture of what is happening within our phenomenon of study (e.g. medical students’ perceptions of the feedback received) and provided associations, but not causal relationships (e.g. the factors associated to medical students’ receptiveness to feedback). It was out of the scope of our review to assess the quality of the studies, and it was not our intention to dismiss any methodology based on quality of evidence. However, it seems that many articles did not follow a rigorous methodology, since many studies did not specify the approach used or only mentioned the analysis method of choice (e.g. content analysis, review). Among the 12 review articles, only two described a rigorous process of data searching and study methodology [55, 56]. Long et al. [56] looked at factors that could affect the credibility of assessment and assessment-generated feedback, and Bing-You et al. [55] conducted a scoping review about feedback for learners in general. Moreover, even though we did not restrict our search by geographic location and language, our results showed that most studies were done in North America. As some of these studies pointed out, the culture of a country seems to affect how medical students receive feedback; therefore, further analysis of studies from outside North America could give us new perspectives on how to manage this phenomenon [46, 48, 50].

Thinking of the factors that affect medical student’s receptiveness to feedback, our content analysis showed that students’ characteristics (e.g., confidence and mindset), feedback content (e.g. constructive, detailed), and feedback provider’s credibility seems to be important. Exploring the students’ characteristics to successfully use feedback, Garino [57] found that students with strong self-regulated learning traits and a growth mindset have more adaptive learning behaviours, and are better able to understand what needs to be done, creates a learning plan, and implemented it; therefore, making better use of the feedback received. Regarding feedback content, some authors showed medical students prefer positive messages and value compliments [58, 59]. However, it seems that student satisfaction is not an accurate measure of quality of feedback; therefore, skills improvements might be more related to constructive feedback. Moreover, student seniority in the programme appears to play a role in students’ perceptions of the purpose of feedback [60]. Thus, junior students value positive and written feedback, while senior students value specific and constructively critical feedback. Looking at our codes related to credibility, as a factor that influences medical students’ receptiveness to feedback, our data supported previous results that feedback is perceived as credible when it involves a certain number of direct observations, and when it is delivered by a credible person (i.e. long term and engaged educator) [31, 61]. Bakke et al. [25] discussed how longitudinal coaching relationships could enhance the feedback provider and feedback’s credibility by promoting frequent and regular interactions, more direct observations, and more interactive discussions. Moreover, in a scoping review about factors affecting credibility of assessment-generated feedback in medical education, Long et al. [56] also suggested that students value feedback given by a trusting and long-term supervisor, as well as, a standardized process with clear purpose. Lastly, our content analysis also highlighted the importance of the culture of the environment where feedback occurs, as discussed in previous researched [10, 23, 31]. Under the category of Learning environment, we found codes such as safe, non-critical, and supportive, endorsing Ramani et al. [23, 62] strategies to improve the learning culture that included establishing a safe and just learning environment. We were also able to find codes related to the Culture of the country. As suggested by Suhoyo et al. [46], cultural aspects may influence receptiveness to feedback; therefore, one model of feedback does not necessarily translate to another country.

Regarding the medical students’ perceptions of feedback in medical school, our content analysis of the articles revealed that students have a positive perception expressed by positive feelings towards the feedback received (e.g. reassuring, encouraging), and when feedback was given through positive messages (e.g. constructive, instructive) in a timely manner. Moreover, the students overall perception of the quality of the feedback was positive. However, these students’ perceptions were mostly related to the studies’ results, which usually included an intervention to improve receptivity to feedback. Still, as described by Duijn et al. [63], students feel that feedback is meaningful when it is instructive, provided immediately after the observed activity, and based on multiple observations from the same supervisor. In a previous study, Greenberg [64] also described that medical students rated the amount and quality of feedback received as high, with most students reporting that the feedback was timely, reinforcing and corrective, and few students reporting it as demeaning and abusive. Additionally, our results showed that negative perceptions were related to an unclear, unspecific, limited, and insufficient feedback, as well as an uncomfortable and intimidated feeling.

Our search for the term feedback literacy in medical schools indicated that this is a very recent and rarely used term in the medical education field. In 2018, Carless and Boud [19] developed a consistent definition of this term, given it was increasingly being introduced into medical education articles [19, 20, 25, 52]. Carless & Boud defined student feedback literacy as ‘the understandings, capacities and dispositions needed to make sense of information and use it to enhance work or learning strategies’ [19 p.1316]. They proposed a framework to underpin students’ feedback literacy that involved appreciating feedback, making judgments, managing affect, and taking actions. In our scoping review, we found four articles that used the term feedback literacy as defined by Carless & Boud, and three studies that proposed programs to promote feedback-literate medical students [12, 20, 25]. Bakke et al. [25] used Carless & Boud definition to support their findings about the positive effects of longitudinal coaches on how medical students conceptualize and engage in feedback discussions. Noble et al. [20] discussed the benefits of their feedback literacy programs for health students using Carless & Boud’s framework. Moreover, McGinness et al. [12] suggested an interactive one-off feedback workshop that helped students to have a more active role in the feedback process based on some of Carless & Boud’s concepts. These studies reported that it is possible to develop programs that could enhance learners’ appreciation to feedback, increase learners’ productive participation in the feedback process and the frequency of feedback seeking by students, and help students to be more aware of possible strategies to acting on feedback.

Perhaps the most helpful contribution from our scoping review to the literature around this topic is the gaps we were able to identify. This is important to guide future researches and move the ongoing feedback discussion forward. Our results endorsed the shifting in the focus of the studies, from processes with respect to provide feedback to receiving the feedback and the role of the environment. This is a valuable finding because it shows that medical education researchers have started moving away from the limited definition of feedback that focus mostly on the feedback provider and the way the message is delivered. However, receptivity to feedback is still a very recent area of study in medical education; therefore, it seems that there is still room to explore further the students’ perceptions of feedback, their reactions to it, how they decode and appraise the information, and the actions they take. More specifically, when thinking about feedback from the receiver’s perspective, our content analysis results showed that receptiveness to feedback could be studied depending on the learners’ academic years (junior and senior years), medical specialties, different feedback providers (i.e. health professionals, residents, peers, and patients), and feedback characteristics (i.e. content and type). Moreover, feedback literacy is indeed a new concept in medical education, and a better understanding of how students recognize and use the feedback provided, and the impact of this feedback in future performances might help us to develop programs to guide medical students in achieving feedback literacy. Many questions about how the learning environment and culture influence the receptiveness to feedback in medical schools are still not answered, especially aspects related to feedback acceptance, feedback seeking, and how the environment could be a barrier for students to take control of their own learning. Lastly, there is a call for more rigorous and well-designed studies in medical education assessing the various aspects of feedback, particularly non-observational quantitative studies and qualitative approaches.

Limitations

Our scoping review has some limitations inherent in this type of methodology. Usually, scoping reviews are not designed to assess studies’ methodological limitations, risk of bias, or the studies’ quality; therefore, our scoping review is not intended to provide clinical guidelines or policy-making recommendations. Instead, we aimed at providing an overview of the topic, examining how research has been conducted on the medical education field, and to identify some knowledge gaps. Additionally, scoping reviews can omit relevant sources of information because it relies on a screening process and on the information being available. For example, our scoping review did not include books, even though we haven’t considered it an exclusion criterion, and we might have left out some relevant articles in the topic because they did not meet our inclusion criteria. We also excluded articles in which feedback was exclusively provided by non-physicians, potentially having some impact on our conclusions. Moreover, our content analysis showed that students’ perceptions towards the feedback received were mostly positive. However, the analysis was mainly related to the studies’ results, and usually these studies included an intervention to improve receptivity to feedback. Lastly, although we have not limited our search based on language or country of origin, all our articles, but one, were in English, and most of them from North America due to the databases we chose to use for this review.

Conclusion

The findings of our scoping review add to the literature by mapping the studies in medical students’ receptiveness to feedback, endorsing some existing knowledge, and providing gaps to guide future research. Our results showed that research focusing on the feedback receiver is very recent in the medical education field, there is a vast variation in studies’ methodologies, and most studies were conducted in North America and Europe. Looking at the factors that affect medical student’s receptiveness to feedback, it seems that students’ characteristics, feedback content, feedback giver’s credibility, the learning environment, and the culture of the country are important elements that should be considered in research about this phenomenon. Regarding medical students’ perceptions of feedback in medical school, we found that most learners had a positive perception expressed by positive feelings and positive messages. Additionally, our search showed that feedback literacy is a very recent and rarely used term in the medical education field; therefore an important area for further investigations. Lastly, we were able to identify many gaps in the literature that will be very helpful to guide future researches, such as studying receptiveness to feedback based on academic seniority, the influence of the workplaces, multisite trials, and feedback literacy long-term impacts on learning.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Devon Wilton, Amrik Randhawa, and Angela Horyacheva for their contributions during the title and abstract screening process, and Amy Keuhl for her administrative work and guidance throughout the study. This article is part of L.C.’s PhD thesis in Health Research Methodology at McMaster University.

Declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable for scoping review methodology.

Conflicts of Interest

There is no conflict of interest in this project.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Archer J. State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med. Educ. 2010;44:101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ende J. Feedback in Clinical Medical Education. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1983;250(6):777–781. doi: 10.1001/jama.1983.03340060055026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kluger AN, Denisi A. The Effects of Feedback Interventions on Performance: A Historical Review, a Meta-Analysis, and a Preliminary Feedback Intervention Theory. Psychol. Bull. 1996;9(2):254–284. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wisniewski B, Zierer K, Hattie J. The Power of Feedback Revisited: A Meta-Analysis of Educational Feedback Research. Front. Psychol. 2020;10(January):1–14. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urquhart LM, Rees CE, Ker JS. Making sense of feedback experiences: A multi-school study of medical students’ narratives. Med. Educ. 2014;48(2):189–203. doi: 10.1111/medu.12304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watling CJ, Ginsburg S. Assessment, feedback and the alchemy of learning. Med. Educ. 2019;53(1):76–85. doi: 10.1111/medu.13645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cantillon P, Sargeant J. Giving feedback in clinical settings. BMJ. 2008;337:a1961. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hattie J, Timperley H. The power of feedback. [References] Rev. Educ. Res. 2007;77(1):16–7. doi: 10.3102/003465430298487. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schartel S. Giving feedback - an integral part of education. Best Pr. Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2012;26(1):77–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2012.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harrison CJ, Könings KD, Dannefer EF, Schuwirth LWT, Wass V, van der Vleuten CPM. Factors influencing students’ receptivity to formative feedback emerging from different assessment cultures. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2016;5(5):276–284. doi: 10.1007/S40037-016-0297-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CPM, Vanstone M, Lingard L. Understanding responses to feedback: The potential and limitations of regulatory focus theory. Med. Educ. 2012;46(6):593–603. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04209.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McGinness HT, Caldwell PHY, Gunasekera H, Scott KM. An educational intervention to increase student engagement in feedback. Med. Teach. 2020;42(11):1289–1297. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1804055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramani S, Post SE, Könings K, Mann K, Katz JT, van der Vleuten C. ‘It’s Just Not the Culture’: A Qualitative Study Exploring Residents’ Perceptions of the Impact of Institutional Culture on Feedback. Teach. Learn. Med. 2017;29(2):153–161. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2016.1244014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rees CE, et al. Power and resistance in feedback during work-integrated learning: contesting traditional student-supervisor asymmetries. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020;45(8):1136–1154. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1704682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urquhart LM, Ker JS, Rees CE. Exploring the influence of context on feedback at medical school: a video-ethnography study. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 2018;23(1):159–186. doi: 10.1007/s10459-017-9781-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bing-You R, Varaklis K, Hayes V, Trowbridge R, Kemp H, McKelvy D. The feedback tango: An integrative review and analysis of the content of the teacher learner feedback exchange. Acad. Med. 2018;93(4):657–662. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telio S, Ajjawi R, Regehr G. The ‘educational Alliance’ as a Framework for Reconceptualizing Feedback in Medical Education. Acad. Med. 2015;90(5):609–614. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watling C, Driessen E, Vleuten CPM, Vanstone M, Lingard L. Beyond individualism: professional culture and its influence on feedback. Med. Educ. 2013;47(6):585–594. doi: 10.1111/medu.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carless D, Boud D. The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2018;43(8):1315–1325. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noble C, et al. ‘It’s yours to take’: generating learner feedback literacy in the workplace. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 2020;25(1):55–74. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09905-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tripodi N, Feehan J, Wospil R, Vaughan B. Twelve tips for developing feedback literacy in health professions learners. Med Teach. 2020;0(0):1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Vanstone M, Grierson L. Medical student strategies for actively negotiating hierarchy in the clinical environment. Med. Educ. 2019;53(10):1013–1024. doi: 10.1111/medu.13945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramani S, Könings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Meaningful feedback through a sociocultural lens. Med. Teach. 2019;41(12):1342–1352. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1656804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watling CJ, Ajjawi R, Bearman M. Approaching culture in medical education: Three perspectives. Med. Educ. 2020;54(4):289–295. doi: 10.1111/medu.14037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bakke BM, Sheu L, Hauer KE. Fostering a Feedback Mindset: A Qualitative Exploration of Medical Students’ Feedback Experiences with Longitudinal Coaches. Acad. Med. 2020;95(7):1057–1065. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bing-you RG, Trowbridge RL. Why Medical Educators May Be Failing at Feedback. JAMA - J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2009;302(12):1330–1331. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Archer JC. State of the science in health professional education: Effective feedback. Med. Educ. 2010;44(1):101–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P, Munn Z, Tricco AC, Khalil H. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis, M. Z. Aromataris E, Ed. JBI. 2020.

- 29.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, Moher D, Peters MD, Horsley T, Weeks L, Hempel S. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual. Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CPM, Lingard L. Learning culture and feedback: An international study of medical athletes and musicians. Med. Educ. 2014;48(7):713–723. doi: 10.1111/medu.12407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van de Ridder JMM, Peters CMM, Stokking KM, de Ru JA, ten Cate OTJ. Framing of feedback impacts student’s satisfaction, self-efficacy and performance. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 2015;20(3):803–816. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9567-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korstjens I, Moser A. Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. part 2: Context, research questions and designs. Eur. J. Gen. Pract. 2017;23(1):274–279. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tracy SJ. Qualitative quality: Eight a"big-tent" criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qual. Inq. 2010;16(10):837–851. doi: 10.1177/1077800410383121. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bleasel J, Burgess A, Weeks R, Haq I. Feedback using an ePortfolio for medicine long cases: Quality not quantity. BMC Med. Educ. 2016;16(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0801-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Preston R, Gratani M, Owens K, Roche P, Zimanyi M, Malau-Aduli B. Exploring the Impact of Assessment on Medical Students’ Learning. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020;45(1):109–124. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1614145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ryan A, et al. Tensions in post-examination feedback: information for learning versus potential for harm. Med. Educ. 2017;51(9):963–973. doi: 10.1111/medu.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Molloy E, Ajjawi R, Bearman M, Noble C, Rudland J, Ryan A. Challenging feedback myths: Values, learner involvement and promoting effects beyond the immediate task. Med. Educ. 2020;54(1):33–39. doi: 10.1111/medu.13802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Abraham RM, Singaram VS. Barriers and promotors in receptivity and utilization of feedback in a pre-clinical simulation based clinical training setting. Bangladesh J. Med. Sci. 2021;20(3):594–607. doi: 10.3329/bjms.v20i3.52802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abraham RM, Singaram VS. Third-year medical students’ and clinical teachers’ perceptions of formative assessment feedback in the simulated clinical setting. African J. Heal. Prof. Educ. 2016;8(1):121. doi: 10.7196/AJHPE.2016.v8i1.769. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kuhlmann Lüdeke A, Guillén Olaya JF. Effective Feedback, An Essential Component of all Stages in Medical Education. Univ Médica. 2020;61(3).

- 43.Kim J-Y, et al. What kind of feedback do medical students want? Korean J. Med. Educ. 2014;26(3):231–234. doi: 10.3946/kjme.2014.26.3.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine University of Oxford. “Study designs,” University of Oxford, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/ebm-tools/study-designs. Accessed: 30-Mar-2022.

- 45.McGinness HT, Caldwell PHY, Gunasekera H, Scott KM. An educational intervention to increase student engagement in feedback. Med. Teach. 2020;42(11):1289–1297. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1804055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Suhoyo Y, Van Hell EA, Prihatiningsih TS, Kuks JBM, Cohen-Schotanus J. Exploring cultural differences in feedback processes and perceived instructiveness during clerkships: Replicating a Dutch study in Indonesia. Med. Teach. 2014;36(3):223–229. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2013.853117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Haqwi AI, Al-Wahbi AM, Abdulghani HM, van der Molen HT. Barriers to feedback in undergraduate medical education male students’ perspective in central Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2012;33(5):557–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Areemit RS, Cooper CM, Wirasorn K, Paopongsawan P, Panthongviriyakul C, Ramani S. Hierarchy, ‘Kreng Jai’ and Feedback: A Grounded Theory Study Exploring Perspectives of Clinical Faculty and Medical Students in Thailand. Teach. Learn. Med. 2021;33(3):235–244. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2020.1813584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ramani S, Könings KD, Mann KV, Pisarski EE, Van Der Vleuten CPM. About politeness, face, and feedback: Exploring resident and faculty perceptions of how institutional feedback culture influences feedback practices. Acad. Med. 2018;93(9):1348–1358. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suhoyo Y, et al. Influence of feedback characteristics on perceived learning value of feedback in clerkships: does culture matter? BMC Med. Educ. 2017;17(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0904-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bowen L, Marshall M, Murdoch-Eaton D. Medical Student Perceptions of Feedback and Feedback Behaviors Within the Context of the ‘educational Alliance’. Acad. Med. 2017;92(9):1303–1312. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molloy E, Boud D, Henderson M. Developing a learning-centred framework for feedback literacy. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2020;45(4):527–540. doi: 10.1080/02602938.2019.1667955. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matthews A, et al. Receiving real-time clinical feedback: A workshop and oste assessment for medical students. Adv. Med. Educ. Pract. 2020;11:861–867. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S271623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bing-You RG, Bertsch T, Thompson JA. Coaching Medical Students in Receiving Effective Feedback. Teach. Learn. Med. 1998;10(4):228–231. doi: 10.1207/S15328015TLM1004_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bing-You R, Hayes V, Varaklis K, Trowbridge R, Kemp H, McKelvy D. Feedback for Learners in Medical Education: What is Known? A Scoping Review. Acad. Med. 2017;92(9):1346–1354. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Long S, Rodriguez C, St-Onge C, Tellier PP, Torabi N, Young M. Factors affecting perceived credibility of assessment in medical education: A scoping review, no. 0123456789. Springer Netherlands. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Garino A. Ready, willing and able: a model to explain successful use of feedback. Adv. Heal. Sci. Educ. 2020;25(2):337–361. doi: 10.1007/s10459-019-09924-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Boehler ML, et al. An investigation of medical student reactions to feedback: A randomised controlled trial. Med. Educ. 2006;40(8):746–749. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02503.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van De Ridder JMM, Berk FCJ, Stokking KM, Ten Cate OTJ. Feedback providers’ credibility impacts students’ satisfaction with feedback and delayed performance. Med. Teach. 2015;37(8):767–774. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.970617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Murdoch-Eaton D, Sargeant J. Maturational differences in undergraduate medical students’ perceptions about feedback. Med. Educ. 2012;46(7):711–721. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watling C. Cognition, culture, and credibility: deconstructing feedback in medical education. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2014;3(2):124–128. doi: 10.1007/S40037-014-0115-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramani S, Könings KD, Ginsburg S, van der Vleuten CPM. Twelve tips to promote a feedback culture with a growth mind-set: Swinging the feedback pendulum from recipes to relationships. Med. Teach. 2019;41(6):625–631. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1432850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duijn CCMA, Welink LS, Mandoki M, ten Cate OTJ, Kremer WDJ, Bok HGJ. Am I ready for it? Students’ perceptions of meaningful feedback on entrustable professional activities. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2017;6(4):256–264. doi: 10.1007/S40037-017-0361-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Greenberg L. Medical students’ perceptions of feedback in a busy ambulatory setting: a descriptive study using a clinical encounter card. South Med J. 2004;97(12). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.