Abstract

Introduction

Treatment satisfaction in diabetes management is vital to achieving long-term clinical outcomes. This analysis evaluated treatment satisfaction among patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) after 52 weeks of treatment with once-weekly tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg) compared with dulaglutide 0.75 mg.

Methods

This exploratory analysis of the phase 3 SURPASS J-mono trial assessed treatment satisfaction using the Japanese translation of the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire status (DTSQs) and change versions (DTSQc). Subgroup analyses were post hoc and conducted for the DTSQc overall treatment satisfaction score based on age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), sex (male or female), baseline body mass index (BMI; < 25 or ≥ 25 kg/m2), and baseline glycated hemoglobin (≤ 8.5% or > 8.5%).

Results

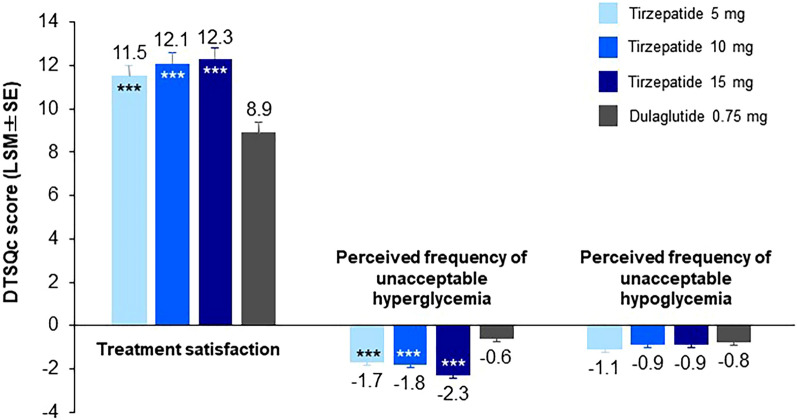

Baseline DTSQs scores were similar among patients across all treatment arms. Overall, trends showed higher satisfaction among patients who received any tirzepatide dose compared with those who received dulaglutide after 52 weeks of treatment. Mean overall DTSQc treatment satisfaction scores at week 52 were significantly higher with tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg versus dulaglutide 0.75 mg (11.5, 12.1, and 12.3, respectively, vs 8.9; P < 0.001). The DTSQc perceived frequency scores for unacceptable hyperglycemia were significantly lower with tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg versus dulaglutide 0.75 mg (− 1.7, − 1.8, and − 2.3, respectively, vs − 0.6; P < 0.001), while scores for unacceptable hypoglycemia were similar across all treatment arms, ranging from − 0.8 to − 1.1. Subgroup analyses showed increased treatment satisfaction with tirzepatide compared with dulaglutide in the < 65 years (P < 0.001) and baseline BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 subgroups (P < 0.01 or < 0.001) and similar treatment satisfaction across treatment arms in the ≥ 65 years and BMI < 25 kg/m2 subgroups.

Conclusion

Patients with T2D reported higher treatment satisfaction with once-weekly tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg) compared with dulaglutide 0.75 mg after 52 weeks of treatment.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03861052.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13300-023-01485-3.

Keywords: Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, Dulaglutide, Japan, Quality of life, Tirzepatide, Type 2 diabetes

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Clinical trial findings have demonstrated greater improvements in glycemic control and body weight reductions in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D) treated with tirzepatide in comparison to dulaglutide. |

| Patient-reported outcomes, such as treatment satisfaction, are important in evaluating the overall benefit of therapies, with a high level of treatment satisfaction more likely to result in greater treatment adherence and reduced long-term diabetes-related complications. |

| Using the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire, this study aimed to evaluate treatment satisfaction among Japanese patients with T2D after 52 weeks of treatment with once-weekly tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg) compared with dulaglutide 0.75 mg. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Among Japanese patients with T2D, overall treatment satisfaction was significantly higher after 52 weeks of treatment with once-weekly tirzepatide compared with dulaglutide. |

| Increased treatment satisfaction was also observed among dulaglutide-treated patients, despite no significant weight loss observed in this treatment arm, suggesting that treatment satisfaction was influenced primarily by improvements in glycemic control among Japanese patients with T2D. |

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a long-term condition that requires daily management of blood glucose levels, with the goal of maintaining quality of life and life expectancy at a level comparable to that of healthy individuals by preventing the onset and progression of serious complications [1]. The importance of treatment satisfaction in diabetes management is well reported and vital to achieving long-term clinical outcomes [2–5].

The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (status version; DTSQs) is a patient-reported outcome (PRO) tool used to assess patients’ satisfaction with their diabetes treatment, which includes questions related to perceived frequencies of unacceptable hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia [6, 7]. The DTSQ has been widely translated, including in Japanese [8], and is internationally validated and officially approved by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the International Diabetes Federation [9]. The DTSQ change version (DTSQc) is used to assess a patient’s change in treatment satisfaction relative to a predefined time point (e.g., at the start of a clinical trial) rather than absolute treatment satisfaction [10]. Findings from numerous studies that have measured differences in the DTSQs and DTSQc between treatments suggest meaningful and clinically relevant distinctions [2, 11].

Tirzepatide is a glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide/glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist approved for the treatment of T2D in the USA, Europe, and Japan [12–14] and is under investigation for chronic weight management. The global phase 3 SURPASS clinical trials have demonstrated that treatment with tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg), either as monotherapy or in addition to other antihyperglycemic medications, results in clinically meaningful improvements in glycemic control and body weight reduction in patients with T2D [15–19]. Two phase 3 clinical trials conducted in Japan (SURPASS J-mono and SURPASS J-combo) demonstrated the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide in patients with T2D [20, 21]. SURPASS J-mono compared the efficacy and safety of once-weekly tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg) with dulaglutide 0.75 mg, a once-weekly GLP-1 receptor agonist. After 52 weeks of treatment, tirzepatide was superior to dulaglutide and demonstrated dose-dependent and statistically significant reductions in glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c; mean reduction of − 2.4% to − 2.8% vs − 1.3% with dulaglutide) and body weight (mean reduction of − 7.8% to − 13.9% vs − 0.7% with dulaglutide) [21]. To expand on these findings and how they relate to patients’ treatment experience, this exploratory evaluation of the SURPASS J-mono trial aimed to assess treatment satisfaction among Japanese patients with T2D using the DTSQ.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This was an exploratory evaluation of treatment satisfaction using data from the SURPASS J-mono clinical trial, a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled, parallel-group phase 3 trial in Japanese patients with T2D, which assessed the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg) compared with dulaglutide 0.75 mg over 52 weeks. The study methods and main outcomes of the trial have been previously published [21]. In brief, participants were Japanese adults aged ≥ 20 years with a T2D diagnosis (WHO classification); were naïve to oral antihyperglycemic medication (OAM) or receiving OAM monotherapy (with the exception of thiazolidinedione) and willing to discontinue the OAM during an 8-week washout period; and had a stable weight (± 5%) for at least 3 months prior to visit 1, a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 23 kg/m2 at visit 1, and an HbA1c ≥ 7.0% to ≤ 10.0% at visits 1 and 2 (for OAM-naïve patients) or ≥ 6.5% to ≤ 9.0% at visit 1 and ≥ 7.0% to ≤ 10.0% at visit 2 (for patients discontinuing OAM). Patients were excluded if they had a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes or a history of any injectable therapy use for T2D, acute or chronic pancreatitis, acute or chronic hepatitis, or diabetic retinopathy requiring acute treatment.

The study was approved by an independent ethical review board at each site and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences international ethical guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent before study participation. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03861052).

Procedures and Outcomes

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1:1 ratio to receive tirzepatide 5, 10, or 15 mg or dulaglutide 0.75 mg. Randomization was stratified on the basis of patients’ baseline HbA1c (≤ 8.5% or > 8.5%), baseline BMI (< 25 or ≥ 25 kg/m2), and need for OAM washout (yes or no). The study comprised a 4-week (for OAM-naïve patients) or 10-week (≥ 8-week washout for patients discontinuing OAM) screening/lead-in period, followed by a 52-week treatment period and a 4-week safety follow-up period. During the treatment period, patients received tirzepatide or dulaglutide once weekly by subcutaneous injection. The tirzepatide dose was initiated at 2.5 mg, increased by 2.5 mg every 4 weeks until the assigned dose was reached, and then maintained for the remainder of treatment.

Treatment satisfaction was a secondary outcome of the trial and was assessed using the Japanese translation of the DTSQ [8]. Two DTSQ versions were used to assess treatment satisfaction: the DTSQs at baseline and the DTSQc at weeks 40 and 52 and in cases of early termination [9, 10].

The DTSQ is a self-administered PRO instrument comprising eight items, which are conceptually similar for the DTSQs and DTSQc versions. Each item of the DTSQs is assessed on a 7-point Likert scale (0 to 6). For six of the eight items (items 1 [satisfaction with current treatment], 4 [convenience], 5 [flexibility], 6 [understanding of diabetes], 7 [recommend treatment to others], and 8 [willingness to continue]), scores range from 0 (very dissatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied) [6]. These scores are summed to provide a composite measure of overall treatment satisfaction, ranging from 0 to 36, with higher scores indicating greater satisfaction. Items 2 and 3 of the DTSQs are used to individually measure the perceived frequency of unacceptable hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, respectively, with scores ranging from 0 (none of the time) to 6 (most of the time). The DTSQc has different response options from those of the DTSQs to produce a measure of the change from baseline in satisfaction rather than absolute satisfaction [10]. Each item of the DTSQc assesses change from baseline on a 7-point scale. Scores for DTSQc item 1 and items 4 to 8 range from − 3 (much less now) to + 3 (much more now), with overall treatment satisfaction scores (sum of scores on item 1 and items 4 through 8) ranging from − 18 to + 18 (higher scores represent greater satisfaction). Possible DTSQc scores for items 2 and 3 (perceived frequency of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia, respectively) range from − 3 (much less of the time now) to + 3 (much more of the time now).

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed on the modified intention-to-treat population of the efficacy analysis set, which included all randomly assigned patients who received at least one dose of study drug and excluded data after initiation of rescue antihyperglycemic medication or permanent study drug discontinuation. For the DTSQs, descriptive statistics are provided at baseline for the perceived hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia items and the six-item overall treatment satisfaction score. For the DTSQc, the proportion of responses (− 3 to + 3) for each item was summarized by treatment arm.

Treatment comparisons of least-squares means (standard error) of scores at week 52 were made between the tirzepatide and dulaglutide arms using a mixed model for repeated measures with treatment, visit, treatment-by-visit interaction, baseline HbA1c (≤ 8.5% or > 8.5%), baseline BMI (< 25 or ≥ 25 kg/m2), and need for OAM washout (yes or no) as fixed effects and baseline measurement as a covariate. An unstructured covariance matrix was used as the model of intrapatient variability.

Subgroup analyses were conducted for the DTSQc overall treatment satisfaction score at week 52, based on age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), sex (male or female), baseline BMI (< 25 or ≥ 25 kg/m2), and baseline HbA1c (≤ 8.5% or > 8.5%), using an analysis of covariance model. The model included the same fixed effects and covariate as those used for the main analysis.

Analyses were conducted at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The DTSQ analyses were prespecified; however, all subgroup analyses were conducted post hoc. No multiplicity adjustment was conducted for the DTSQc.

Results

Baseline Demographics and Characteristics

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics were well balanced across treatment arms, with males comprising 75.6% of all patients (Table 1). The overall mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of patients was 56.6 (10.3) years, with 75.2% of patients aged < 65 years and 24.8% aged ≥ 65 years. Patients had an overall mean (SD) BMI of 28.1 (4.4) kg/m2, with 25.3% and 74.7% of patients included in the BMI < 25 kg/m2 and ≥ 25 kg/m2 subgroups, respectively. The overall mean (SD) HbA1c among patients was 8.18% (0.9%), with 68.1% and 31.9% of patients included in the HbA1c ≤ 8.5% and > 8.5% subgroups, respectively.

Table 1.

Demographic and baseline characteristics

| Tirzepatide 5 mg (n = 159) | Tirzepatide 10 mg (n = 158) | Tirzepatide 15 mg (n = 160) | Dulaglutide 0.75 mg (n = 159) | Total (N = 636) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 56.8 (10.1) | 56.2 (10.3) | 56.0 (10.7) | 57.5 (10.2) | 56.6 (10.3) |

| < 65, n (%) | 120 (75.5) | 123 (77.8) | 124 (77.5) | 111 (69.8) | 478 (75.2) |

| ≥ 65, n (%) | 39 (24.5) | 35 (22.2) | 36 (22.5) | 48 (30.2) | 158 (24.8) |

| Male, n (%) | 113 (71.1) | 119 (75.3) | 132 (82.5) | 117 (73.6) | 481 (75.6) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.6 (5.4) | 28.0 (4.1) | 28.1 (4.4) | 27.8 (3.7) | 28.1 (4.4) |

| < 25, n (%) | 37 (23.3) | 42 (26.6) | 42 (26.3) | 40 (25.2) | 161 (25.3) |

| ≥ 25, n (%) | 122 (76.7) | 116 (73.4) | 118 (73.8) | 119 (74.8) | 475 (74.7) |

| HbA1c, % | 8.18 (0.9) | 8.19 (0.9) | 8.19 (0.9) | 8.15 (0.9) | 8.18 (0.9) |

| ≤ 8.5%, n (%) | 108 (67.9) | 106 (67.1) | 109 (68.1) | 110 (69.2) | 433 (68.1) |

| > 8.5%, n (%) | 51 (32.1) | 52 (32.9) | 51 (31.9) | 49 (30.8) | 203 (31.9) |

Data are shown as mean (standard deviation), unless otherwise indicated, for all randomized patients

HbA1c glycated hemoglobin

Baseline DTSQs scores were similar across the tirzepatide 5-, 10-, and 15-mg arms and the dulaglutide 0.75-mg arm. Patients had a mean (SD) treatment satisfaction score on the DTSQs of 23.6 (6.3). The DTSQs mean (SD) perceived frequency scores for unacceptable hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia among patients were 3.0 (1.9) and 0.5 (1.1), respectively.

Study Completion and Treatment Adherence

Overall, 96.7% of patients completed the study. The proportion of patients who completed the study was similar across treatment arms: 97.5%, 95.6%, and 96.9% for tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg, respectively, and 96.9% for dulaglutide 0.75 mg. Overall treatment adherence was high (98.3% of patients overall) and similar across treatment arms, with 98.1%, 97.5%, 98.1%, and 99.4% of patients who received tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg, respectively, achieving treatment adherence.

Treatment Satisfaction Outcomes

The proportion of responses for each score on the eight items of the DTSQc after 52 weeks of treatment with tirzepatide 5, 10, or 15 mg or dulaglutide 0.75 mg is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Proportion of responses for each score on DTSQc items at week 52. The proportion of responses for each score on the 8 items of the DTSQc after 52 weeks of treatment with TZP 5, 10, or 15 mg or Dula 0.75 mg is shown for the modified intent-to-treat population (efficacy analysis set). For DTSQc item 1 and items 4 through 8 (a–f), change from baseline was assessed on a 7-point scale ranging from − 3 (much less now) to + 3 (much more now). DTSQc items 2 and 3 (g–h) were scored on a scale ranging from − 3 (much less of the time now) to + 3 (much more of the time now). DTSQc Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (change), Dula dulaglutide, TZP tirzepatide

With possible scores ranging from − 3 to + 3 on individual items, most responses for item 1 and items 4 through 8 of the DTSQc were in the positive range across all treatment arms (for both tirzepatide and dulaglutide), indicating that patients were more satisfied with their treatment at week 52. For item 2 (perceived frequency of unacceptable hyperglycemia), most responses were in the negative range, indicating a perceived improvement in hyperglycemic control. For item 3, most responses were 0 or in the negative range, indicating no change or an improvement from baseline in patients’ perceived frequency of unacceptable hypoglycemia.

Across all DTSQc items, trends showed higher satisfaction among patients who received any tirzepatide dose compared with those who received dulaglutide. Mean overall DTSQc treatment satisfaction scores at week 52 were statistically significantly higher among patients who received tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg compared with those who received dulaglutide 0.75 mg (11.5, 12.1, and 12.3, respectively, vs 8.9; P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The DTSQc perceived frequency scores for unacceptable hyperglycemia were significantly lower among patients who received tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg compared with those who received dulaglutide 0.75 mg (− 1.7, − 1.8, and − 2.3, respectively, vs − 0.6; P < 0.001; Fig. 2). The DTSQc perceived frequency scores for unacceptable hypoglycemia were similar across all tirzepatide dose groups and the dulaglutide arm, ranging from − 0.8 to − 1.1 (Fig. 2). The observed improvements in treatment satisfaction, as well as improvements in the perceived frequency of unacceptable hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia, were consistent at week 40 and week 52 across all treatment arms (Table S1 in the supplementary material). The proportion of responses at baseline (DTSQs) and week 52 (DTSQc) are outlined in Fig. S1 in the supplementary material. There was no obvious correlation between treatment satisfaction (DTSQc total score) and change from baseline in HbA1c or body weight because of a ceiling effect (Fig. S2).

Fig. 2.

Mean DTSQc scores at week 52 for the modified intent-to-treat population (efficacy analysis set). Data are shown as LSM (SE). The overall treatment satisfaction score represents the sum of the scores on item 1 and items 4 through 8 of the DTSQc, with possible total scores ranging from − 18 to + 18 (higher scores represent greater satisfaction). Possible scores for perceived frequency of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia range from − 3 (much less of the time now) to + 3 (much more of the time now). Treatment comparisons at week 52 were made between tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg using a mixed model for repeated measures. ***P < 0.001 vs dulaglutide 0.75 mg. DTSQc Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (change), LSM least-squares mean, SE standard error

In the subgroup analyses, the mean overall DTSQc treatment satisfaction scores at week 52 in the male and female subgroups and baseline HbA1c (≤ 8.5% or > 8.5%) subgroups were generally similar to those in the overall study population. Treatment satisfaction scores were significantly higher among patients who received tirzepatide compared with those who received dulaglutide, with the exception of the tirzepatide 5-mg arm in the female and HbA1c > 8.5% subgroups (Fig. 3). Significantly better treatment satisfaction was also observed with tirzepatide compared with dulaglutide in the < 65 years subgroup (P < 0.001) and the baseline BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 subgroup (P < 0.01 or P < 0.001), whereas similar treatment satisfaction was observed across treatment arms in the ≥ 65 years and BMI < 25 kg/m2 subgroups.

Fig. 3.

Mean DTSQc treatment satisfaction scores for subgroups at week 52. Mean DTSQc scores at week 52 for the modified intent to treat population (efficacy analysis set) are shown for the subgroup analyses, including a age (< 65 and ≥ 65 years), b sex, c baseline BMI (< 25 and ≥ 25 kg/m2), and d baseline HbA1c (≤ 8.5% and > 8.5%). Data are shown as LSM (SE). The overall treatment satisfaction score represents the sum of the scores on item 1 and items 4 through 8 of the DTSQc, with possible total scores ranging from − 18 to + 18 (higher scores represent greater satisfaction). Treatment comparisons at week 52 were made between tirzepatide 5, 10, and 15 mg and dulaglutide 0.75 mg using an analysis of covariance model. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 vs dulaglutide 0.75 mg. BMI body mass index, DTSQc Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (change), HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, LSM least-squares mean, SE standard error

Discussion

The SURPASS J-mono and SURPASS J-combo trials established the efficacy and safety of tirzepatide in Japanese patients with T2D [20, 21]. In the current exploratory analysis of the SURPASS J-mono trial, we build upon these findings by reporting multiple domains of treatment satisfaction, further supporting the value of tirzepatide treatment in this patient population.

Overall, the DTSQc treatment satisfaction scores after 52 weeks were significantly greater among patients who received treatment with tirzepatide (5, 10, or 15 mg) than with dulaglutide 0.75 mg. The DTSQc perceived frequency score of unacceptable hyperglycemia was significantly lower across all tirzepatide treatment arms compared with that of dulaglutide, while the perceived frequency score of unacceptable hypoglycemia was similar across tirzepatide and dulaglutide arms. Furthermore, treatment satisfaction was generally higher with tirzepatide treatment, or comparable with that of dulaglutide, in subgroup analyses by patient age (< 65 or ≥ 65 years), sex, baseline BMI (< 25 or ≥ 25 kg/m2), and baseline HbA1c (≤ 8.5% or > 8.5%).

Patient satisfaction is an important outcome in drug treatment, with greater treatment satisfaction associated with better treatment compliance and improved persistence [22]. In a recent report of patients with T2D in Japan, increased treatment satisfaction (as measured by the DTSQ) was highly correlated with an increase in treatment motivation [23].

Tirzepatide PROs have been described in the global SURPASS clinical trial program. In a subset of patients from the SURPASS-2 and SURPASS-3 trials, tirzepatide treatment was reported as being meaningful, with significant positive impacts on quality of life [24]. In the SURPASS-3 trial, the DTSQc total score was significantly higher for all tirzepatide doses compared with that for insulin degludec, indicating a greater improvement in treatment satisfaction [25]. In addition, the self-reported DTSQc score for perceived frequency of unacceptable hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia was significantly lower with tirzepatide 15 mg and 5 mg, respectively, compared with insulin degludec [25]. In pooled analyses of the SURPASS 1–5 trials, greater improvements in PROs were observed among patients who achieved larger reductions in HbA1c and body weight [26, 27]. Specifically, a greater improvement from baseline in DTSQc scores was observed among patients with a ≥ 2% decrease in HbA1c levels and ≥ 20% weight loss [26, 27].

In the dulaglutide treatment arm, 50–63% of patients reported a rating of 2 or 3 (much more satisfied) on the DTSQc treatment satisfaction items, even though no significant weight reductions were observed in this cohort [21]. This is consistent with our previous report that showed 67.0% of patients who received dulaglutide achieved an HbA1c < 7.0% [21]. For the tirzepatide treatment arms, where significant weight reductions were observed after 52 weeks of treatment [21], more than 80% of patients reported a rating of 2 or 3 on the DTSQc treatment satisfaction items. It is difficult to ascertain any significant differences between the DTSQc scores among the three tirzepatide dose groups, and it also remains unclear whether further reductions in HbA1c and body weight may contribute to further improvements in DTSQc responses.

Results from the subgroup analyses showed no significant differences in DTSQc scores between the tirzepatide and dulaglutide arms among patients aged ≥ 65 years and those with a BMI < 25 kg/m2. However, treatment satisfaction was higher among patients aged < 65 years and those with a BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2. Satisfaction with weight loss also appears to be higher in these populations of younger patients and those with a higher BMI. Of note, Japanese patients with T2D, in general, are leaner than Western patients; hence, weight reduction is not a specific consideration in this population with a relatively leaner body mass.

This analysis has some limitations. First, there were a small number of patients in some subgroups of the analyses of treatment satisfaction by background characteristics. Second, in the SURPASS J-mono trial, dulaglutide was administered at a dose of 0.75 mg in accordance with the Japan label. Hence, the comparisons reported between tirzepatide and dulaglutide in this analysis may not extrapolate to higher doses of dulaglutide. Thirdly, as this analysis was performed in patients who completed study treatment, it is difficult to evaluate if adverse events had an impact on treatment satisfaction. In addition, there are general limitations of the DTSQ, including the subjective nature of some factors. Of note, treatment satisfaction may be higher in clinical trial settings compared with real-world data because of potentially higher treatment adherence among patients enrolled in clinical trials.

Conclusion

In this exploratory analysis of the SURPASS J-mono trial, treatment satisfaction after 52 weeks of treatment was higher with once-weekly tirzepatide (5, 10, and 15 mg) compared with dulaglutide 0.75 mg. Increased treatment satisfaction was also observed among patients who received dulaglutide 0.75 mg, despite no significant weight loss observed in this treatment arm, suggesting that treatment satisfaction was influenced primarily by improved glycemic control among Japanese patients with T2D. A high level of treatment satisfaction may translate into clinically meaningful improvements with reduced long-term diabetes-related complications.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for participating in the SURPASS J-mono trial.

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

Project management support was provided by Aki Yoshikawa and Megumi Katoh from Eli Lilly Japan K.K. Medical writing (Lisa Cossens) and editing (Adrienne Schreiber) were provided by Syneos Health and funded by Eli Lilly Japan and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation.

Author Contributions

Hitoshi Ishii was involved in data analysis and interpretation. Tomonori Oura and Masakazu Takeuchi were involved in study conception and design and data analyses and interpretation. All authors were involved in the critical review of the manuscript. All authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Manuscript development including the journal’s Rapid Service were funded by Eli Lilly Japan and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation.

Data Availability

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data-sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data-sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Hitoshi Ishii has received honoraria from Eli Lilly Japan, Novo Nordisk Pharma Ltd., Merck & Co., Inc., and Sumitomo Pharma Co., Ltd. Tomonori Oura and Masakazu Takeuchi are employees of Eli Lilly Japan K.K. and minor shareholders of Eli Lilly and Company.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by an independent ethical review board at each site and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki 1964 and its later amendments and the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences international ethical guidelines. All patients provided written informed consent before study participation. The study was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03861052). Eli Lilly and Company obtained permission to use the DTSQs and DTSQc for the purposes of this study.

References

- 1.Araki E, Goto A, Kondo T, et al. Japanese Clinical Practice Guideline for Diabetes 2019. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11(4):1020–1076. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies M, Speight J. Patient-reported outcomes in trials of incretin-based therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2012;14(10):882–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2012.01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cobden DS, Niessen LW, Barr CE, Rutten FF, Redekop WK. Relationships among self-management, patient perceptions of care, and health economic outcomes for decision-making and clinical practice in type 2 diabetes. Value Health. 2010;13(1):138–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2009.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Speight J, Holmes-Truscott E, Hendrieckx C, Skovlund S, Cooke D. Assessing the impact of diabetes on quality of life: what have the past 25 years taught us? Diabet Med. 2020;37(3):483–492. doi: 10.1111/dme.14196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradley C, Eschwège E, de Pablos-Velasco P, et al. Predictors of quality of life and other patient-reported outcomes in the PANORAMA multinational study of people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(2):267–276. doi: 10.2337/dc16-2655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saisho Y. Use of Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire in diabetes care: importance of patient-reported outcomes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(5):947. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15050947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Perri M., 3rd A systematic review of patient-reported satisfaction with oral medication therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes. Value Health. 2018;21(11):1346–1353. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishii H, Bradley C, Riazi A, Barendse S, Yamamoto T. The Japanese version of the Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire (DTSQ): translation and clinical evaluation. J Clin Exp Med. 2000;192:809–814. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley C, Gamsu DS. Guidelines for encouraging psychological well-being: report of a Working Group of the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe and International Diabetes Federation European Region St Vincent Declaration Action Programme for Diabetes. Diabet Med. 1994;11(5):510–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1994.tb00316.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradley C. Diabetes treatment satisfaction questionnaire. Change version for use alongside status version provides appropriate solution where ceiling effects occur. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(3):530–532. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.3.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bradley C, Plowright R, Stewart J, Valentine J, Witthaus E. The Diabetes Treatment Satisfaction Questionnaire change version (DTSQc) evaluated in insulin glargine trials shows greater responsiveness to improvements than the original DTSQ. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:57. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves novel, dual-targed treatment for type 2 diabetes. 2022. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-novel-dual-targeted-treatment-type-2-diabetes. Accessed 22 May 2023.

- 13.European Medicines Agency. Mounjaro. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/mounjaro#:~:text=Mounjaro%20contains%20the%20active%20substance,)%2C%20upper%20arm%20or%20thigh. Accessed 22 May 2023.

- 14.Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency. New drugs approved in FY 2022. https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000263199.pdf. Accessed 17 July 2023.

- 15.Dahl D, Onishi Y, Norwood P, et al. Effect of subcutaneous tirzepatide vs placebo added to titrated insulin glargine on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: the SURPASS-5 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2022;327(6):534–545. doi: 10.1001/jama.2022.0078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenstock J, Wysham C, Frías JP, et al. Efficacy and safety of a novel dual GIP and GLP-1 receptor agonist tirzepatide in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-1): a double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):143–155. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01324-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Del Prato S, Kahn SE, Pavo I, et al. Tirzepatide versus insulin glargine in type 2 diabetes and increased cardiovascular risk (SURPASS-4): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10313):1811–1824. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frías JP, Davies MJ, Rosenstock J, et al. Tirzepatide versus semaglutide once weekly in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2021;385(6):503–515. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2107519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludvik B, Giorgino F, Jódar E, et al. Once-weekly tirzepatide versus once-daily insulin degludec as add-on to metformin with or without SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS-3): a randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398(10300):583–598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01443-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadowaki T, Chin R, Ozeki A, Imaoka T, Ogawa Y. Safety and efficacy of tirzepatide as an add-on to single oral antihyperglycaemic medication in patients with type 2 diabetes in Japan (SURPASS J-combo): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, parallel-group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(9):634–644. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00187-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inagaki N, Takeuchi M, Oura T, Imaoka T, Seino Y. Efficacy and safety of tirzepatide monotherapy compared with dulaglutide in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes (SURPASS J-mono): a double-blind, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2022;10(9):623–633. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(22)00188-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barbosa CD, Balp MM, Kulich K, Germain N, Rofail D. A literature review to explore the link between treatment satisfaction and adherence, compliance, and persistence. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:39–48. doi: 10.2147/PPA.S24752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motoda S, Watanabe N, Nakata S, et al. Motivation for treatment correlating most strongly with an increase in satisfaction with type 2 diabetes treatment. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13(4):709–721. doi: 10.1007/s13300-022-01235-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matza LS, Stewart KD, Landó LF, Patel H, Boye KS. Exit interviews examining the patient experience in clinical trials of tirzepatide for treatment of type 2 diabetes. Patient. 2022;15(3):367–377. doi: 10.1007/s40271-022-00578-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu M, Bray R, Brown K, Fernández Landó L, Rodríguez Á, Boye K. IDF21-0036 Patient-reported outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes treated with tirzepatide or insulin degludec (SURPASS-3) Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2022;186(Suppl 1):109700. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2022.109700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thieu V, Boye KS, Lee C, Sapin H. IDF2022-0371 Decreased HbA1c levels associated with improved patient reported outcomes in T2D patients treated with tirzepatide. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;197(Suppl 1):110304. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boye KS, Thieu V, Lee C, Sapin H. IDF2022-0372 Higher weight loss is associated with improved patient reported outcomes in T2D patients treated with tirzepatide. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2023;197(Suppl 1):110305. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2023.110305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Eli Lilly and Company provides access to all individual participant data collected during the trial, after anonymization, with the exception of pharmacokinetic or genetic data. Data are available to request 6 months after the indication studied has been approved in the US and EU and after primary publication acceptance, whichever is later. No expiration date of data requests is currently set once data are made available. Access is provided after a proposal has been approved by an independent review committee identified for this purpose and after receipt of a signed data-sharing agreement. Data and documents, including the study protocol, statistical analysis plan, clinical study report, and blank or annotated case report forms, will be provided in a secure data-sharing environment. For details on submitting a request, see the instructions provided at www.vivli.org.