Abstract

Objective

Cell sheet transplantation is emerging as an appealing alternative for ischemic heart disease patients as it potentially can increase stem cell viability and retention. But the outcomes and safety of this treatment are still limited in literature and the result varies widely. We conduct a systematic review to look at the efficacy and safety of this promising transplantation method.

Methods

A systematic review was performed according to PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive literature search was undertaken using the PubMed, Scopus, and Embase databases. Articles were thoroughly evaluated and analyzed.

Results

Seven publications about cell sheet transplantation for ischemic heart disease patients were included. The primary outcomes measured were left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and New York Heart Association (NYHA) class. Safety measurement was depicted by cardiac-related readmission and deaths. The follow-up time ranged from 3 to 36 months for clinical outcomes and 8.5 years for safety outcomes. Cell sheet transplantation showed improvement in LVEF and NYHA class in most studies. Cardiac-related readmission and adverse events of cell sheet transplantation range from 0 to 30.4%, all were nonfatal as no cardiac-related death was reported. Patient preoperative status seems can affect the patient’s response to cell sheet therapy.

Conclusion

Cell sheet transplantation can safely improve LVEF and NYHA class in ischemic heart disease patients, even in very low ejection fraction patients with unsuccessful standard therapy before. Further studies with better patient inclusion, larger population, and long-term follow-up required to confirm these results.

Keywords: Cell sheet transplantation, Ischemic heart disease, Outcome, Safety, Stem cell

Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases are the leading cause of death worldwide in the twenty-first century with around one-third of deaths worldwide, and ischemic heart disease (IHD) sitting at the top as the most common [1]. Most known to cause mortality, the morbidity rate of non-fatal IHD is also as high as mortality and causes serious chronic disability that is not only a health problem, but also a socioeconomic problem, as this disease tends to be associated with younger patients of reproductive age these days [2, 3]. Recent improvements in the management of IHD involve not only standard treatments such as risk modification, guided medical therapy, and revascularization, but also rely on newer, more advanced therapies such as organ transplants and stem cell–based therapies [4, 5].

Treatment of heart failure, which occurs as a result of loss of viable myocardial tissue and subsequent tissue remodeling, remains a challenging issue because cardiomyocytes are late-differentiating cells with minimal regenerative capacity despite advances in the standard treatment of IHD [6, 7]. Nowadays—high cost and limited availability—heart transplantation is currently the only treatment option for end-stage heart failure caused by IHD [6, 8]. But the emergence of cellular and biomolecular technologies brought stem cells as one of the most promising treatments for IHD-related heart failure as it overcome the cost and availability issues of the heart transplantation [9]. One of the main problems associated with stem cell therapy in IHD is the method of cell delivery, wherein the common injection delivery methods (intravenous, intramyocardial, or intracoronary) face low cell survival and retention rates in the target area [10, 11]. To solve this, direct transplantation in the targeted area is one of the most feasible solutions [12].

Cell sheet transplantation, an approach based on cell and tissue engineering technology, is attracting much attention as a promising way to improve cell survival and retention [13, 14]. Advances in cardiothoracic and minimally invasive surgery have also supported the development of these cell delivery methods, rather than least invasive injection methods [15]. A large number of pre-clinical and animal studies show promising results from this method, but only a few clinical trials have been conducted [12, 13, 16]. Although still limited, recent research results have revealed mixed but generally encouraging results. However, there are currently few studies examining the clinical outcome and safety of this cell sheet transplantation and it has not yet been thoroughly reviewed [17–21].

The authors believe that it is very important to comprehensively evaluate the clinical results of this promising stem cell delivery method for IHD cases because the trend of stem cell transplantation is getting bigger in this era. We conducted a systematic review of the relevant published clinical literature to reveal the importance of the efficacy and safety of this promising approach. We intend to highlight the critical nature of fundamental knowledge related to stem cell treatment, particularly cell sheet transplantation in IHD in the future to facilitate further research and theory development.

Materials and methods

Eligibility criteria

The studies used in this review were full-text case reports, cohort studies, and clinical trials in patients with IHD who received cell-based therapy by cell sheet transplantation method. Reviews, unpublished articles, letters to the editor, abstracts, and studies not written in English were excluded from this study.

Type of outcome measurement

The primary outcome was measured using the left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and the New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification. We also assessed the safety by measuring cardiac-related readmission (CRA), cardiac-related deaths (CRDs), adverse events (AEs), and serious adverse events (SAEs) during the study follow-up period.

Search methods and identification of studies

Information sources

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis guidelines [22]. Literature was obtained by searching the PubMed, Scopus, and Embase electronic databases in January–February 2022. We apply language restrictions to our searches; only articles in English were selected. No publication time limit was enforced in our review. We have registered our studies at PROSPERO with registration number CRD42023399899.

Search protocol

The research questions were constructed using a patient/population, intervention, comparison, and outcome (PICO) model. A predefined PICO framework was used to select relevant studies for inclusion in the review. The following keywords were used to search all trial registers and databases: (“sheet”) AND (“transplantation” OR “application” OR “implantation”) AND (“cardiac” OR “cardiac” OR “myocardial” OR “cardiomyopathy”).

Data collection and analysis

All search records were filtered by title and abstract. Three authors Ahmad Muslim Hidayat Thamrin (AMHT), Tri Wisesa Soetisna (TWS), and Hari Hendarto (HH) independently assessed studies based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies with irrelevant titles were excluded, followed by studies with irrelevant abstracts. Non-English publications were automatically excluded. Full-text articles, including case reports, cohort studies, and clinical trials, that met the eligibility criteria were then assessed by all authors. Details regarding the causes of exclusion were recorded and reported. A flowchart of the study selection processes is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines flowchart

Data extraction and management

Three authors (AMHT, TWS, HH) independently extracted data from tabulations containing information on patient preoperative characteristics, treatment, study quality, and outcomes [23]. Details regarding the author, year of publication, study design, total patients involved, assignments of intervention and control groups, comorbidities, medications received, previous interventions, type and dose of cells used, transplantation method, concomitant/control treatment, follow-up duration, primary outcome based on the predetermined primary parameters (LVEF and NYHA class), and safety outcome (CRA, CRD, AE, SAE) were summarized in a table for qualitative analysis. For measured outcomes (LVEF, NYHA class), we also extracted or reanalyzed the mean difference between the experimental and control groups, and also between the baseline and post-transplantation as reported by the study authors. For CRA, CRD, and AE, we extracted the number of events in each group and measured their incidence. Three review authors (AMHT, TWS, HH) entered all data into Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.4 [24].

Assessment of study quality and risk of bias in included studies

Each author independently assessed the risk of bias in each study included in the systematic review using criteria outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Review of Interventions for nonrandomized studies, referred to as Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Intervention Studies (ROBINS-I) for nonrandomized studies and Risk of Bias 2 for randomized studies [23]. The results of each interpreter’s assessment were then discussed by all authors. The risk of bias table and summary aspects of bias from the included studies were used to interpret the results of the systematic review considering the overall risk of bias assessment [25, 26].

Results

A total of 537 studies were identified and screened. Of these, 24 studies were assessed for eligibility, and 7 were included in the systematic review. A summary of the characteristics of patients in the included studies is shown in Table 1. A summary of the results of each study is shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Summary of the studies included in the systematic review

| Author(s) | Study design |

Number of patients |

Group | Age (years) | Comorbid(s) (%) | Medication(s) (%) | Previous intervention (%) | Cell sheet type | Number of sheets and cells | Transplantation method | Concomitant/control treatment | Follow-up length | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Imamura et al. 2015 [17] | NRCT | 28 | 7 (exp) | 56 ± 13 | HT (42.9), DM (42.9), dyslipidemia (85.7) |

ACEI/ARB (85.7) β-blocker (100) Diuretic (85.7) Antiplatelet (85.7) |

PCI (85.7) CABG (85.7) PCI/CABG (100) CRT (14) |

Autologous myoblast (TCD-51073), |

5 sheets; 3 × 108 |

Thoracotomy, sheets transplanted over infarct area in anterior and lateral wall of left ventricle | None |

6 months (clinical) 1 year (safety) |

Significant LVEF dan NYHA class improvement compared to control group |

| 21 (cont) | 56 ± 13 | NA (matched) | NA (matched) | NA (matched) | CRT | ||||||||

| Sawa et al. 2015 [19] | NRCT | 7 | 7 (exp) | 56 ± 13 | HT (42.9), DM (42.9), dyslipidemia (85.7) |

ACEI/ARB (85.7) β-blocker (100) Diuretic (85.7) Antiplatelet (85.7) |

PCI (85.7) CABG (85.7) PCI/CABG (100) CRT (14) |

Autologous myoblast (TCD-51073) |

5 sheets; 3 × 108 |

Thoracotomy, sheets transplanted over infarct area in anterior and lateral wall of left ventricle | None | 1 year (clinical and safety) | Significant LVEF dan NYHA class improvement. Shares patient dataset with Imamura et al. (2015) |

| Miyagawa et al. 2017 [21] | NRCT | 15 | 15 (exp) | 52.6 ± 15.4 |

HT (66.7) DM (33.3) Dyslipidemia (73.3) |

ACEI (66.7) ARB (33.3) β-blocker (100) Diuretic (100) Antiplatelet (80) |

PCI (66.7) CABG (40) CRT (13.3) ICD (20) |

Autologous skeletal myoblast | 3–4 layers | Thoracotomy, sheets transplanted over infarct area in anterior and lateral wall of left ventricle | None | 1 year | Significant LVEF, LVEDD, NYHA, and BNP improvement |

| Yoshida et al. 2018 [27] | CR | 1 | 1 (exp) | 25 | NA | NA | Revascularization therapy (not mentioned) | Autologous skeletal myoblast |

5 sheets; 3 × 108 |

Thoracotomy, sheets transplanted over infarct area in anterior and lateral wall of left ventricle | None | 2 year | LVEF improves 17%, moving distance on transplanted area increased remarkably |

| Yamamoto et al. 2019 [28] | CR | 1 | 1 (exp) | 22 | Infective myocarditis | NA |

MVR CABG |

Autologous skeletal myoblast |

6 sheets, 4 layers; 3.6 × 106 |

Thoracotomy, sheets transplanted over infarct area in anterior and lateral wall of left ventricle | None | 3 year | Clinical symptoms significantly improved consistently for 36 months without LVAD or organ transplant |

| Kainuma et al. 2021 [20] | NRCT | 23 | 23 (exp) | 56 ± 14 |

HT (70) DM (30) Dyslipidemia (83) |

ACEI (63) ARB (22) β-Blocker (100) Diuretic (78) |

PCI (70) CABG (30) CRT (13) ICD (17) |

Autologous skeletal myoblast | 3.7 ± 1.7 × 108 | Thoracotomy, sheets transplanted over infarct area in anterior and lateral wall of left ventricle | None | 6 months (clinical) and up to 8.5 years (safety) | Significant improvement of LVEF, LVEDD, NYHA, BNP after 1 year. Shares patient dataset with Miyagawa et al |

| Nummi et al. 2021 [18] | NRCT | 12 | 6 (exp) | 65.99 ± 1.85 |

HT (100) DM (33) Dyslipidemia (100) |

ACEI/ARB (100) β-Blocker (83) Diuretic (50) Antiplatelet (100) |

PCI (17) | Autologous cardiac microtissue |

Single sheet; 9.76 × 106 |

Thoracotomy (during CABG), sheet transplanted over infarct area | CABG |

3 months (clinical) 1 year (safety) |

Significant improvement of infarction area thickness and thinnest wall thickness compared to control group |

| 6 (cont) | 72 ± 3.12 |

HT (83) DM (67) Dyslipidemia (67) |

ACEI/ARB (83) β-Blocker (67) Diuretic (33) Antiplatelet (100) |

None | CABG |

ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, BNP B-type natriuretic peptide, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, Cont control, CR case report, CRT cardiac resynchronization therapy, DM diabetes mellitus, Exp experimental, HT hypertension, LVAD left ventricular assist device, LVEDD left ventricle end diastolic diameter, MVR mitral valve replacement, NA not available, NRCT non-randomized clinical trial, PCI percutaneous intervention, NYHA New York Heart Association

Table 2.

Outcomes of study included in systematic review

| Study | Group (n) | LVEF (%) | NYHA class | Clinical safety | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before (mean ± SD) |

After (mean ± SD) |

P-value | Change (mean ± SD) |

P-value (between group) |

Before (mean ± SD) |

After (mean ± SD) |

P-value | Change (mean ± SD) |

P-value (between group) |

CRA (%) | CRD (%) | Other AE (%) | ||

| Imamura et al. 2015 [17] |

Exp (7) |

26 ± 4 | 33 ± 5 | 0.001 | 7.1 ± 2.8 | < 0.001 | 3 ± 0 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.005 | − 1.1 ± 0.7 | < 0.001 | 2/7 (28.6) | 0/7 (0) | NA |

|

Cont (21) |

24 ± 10 | 23 ± 12 | NS | − 1 ± 5.5 | 3 ± 0 | 3.2 ± 0.4 | 0.02 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 8/21 (38.1) |

7/21 (33.3) |

NA | |||

| Sawa et al. 2015 [19] |

Exp (7) |

26 ± 4 | 33 ± 5 | 0.001 | 7.1 ± 2.8 | – | 3 ± 0 | 1.9 ± 0.7 | 0.005 | − 1.1 ± 0.7 | – |

2/7 (28.6) |

0/7 (0) |

1 colon cancer (14) |

| Miyagawa et al. 2017 [21] |

Exp (15) |

26.7 ± 8 | 30.7 ± 10 | < 0.01 | 4 ± 5.6 | – | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | < 0.05 | − 1 ± 0.4 | – | 0/15 (0) | 0/15 (0) | None |

| Yoshida et al. 2018 [27] |

Exp (1) |

20 | 37 | – | 17 | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0/1 (0) | 0/1 (0) | None |

| Yamamoto et al. 2019 [28] |

Exp (1) |

12 | 32.8 | – | 20.8 | – | 3 | 1 | – | 2 | – | 0/1 (0) | 0/1 (0) | None |

| Kainuma et al. 2021 [20] |

Exp (23) |

26 ± 6 | 29 ± 9 | < 0.05 | 3 ± 5.2 | – | 2,9 ± 0.5 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 | 0.9 ± 0.1 | – | 7/23 (30.4) | 0/23 (0) | 4 non-CRD (17.4) |

| Nummi et al. 2021 [18] |

Exp (6) |

46.1 ± 18.1 | 48.8 ± 21.9 | NA | 2.7 ± 10.8 | 0.85 | 2.4 ± 1 | 2.4 ± 1 | NS | 0 | NA | 0/6 (0) | 0/6 (0) | 1 sternal infection (16.7) |

| Cont (6) | 38 ± 13.3 | 41.7 ± 10.5 | NA | 3.7 ± 6.2 | 2.6 ± 1 | 2 ± 0 | NA | − 0.6 ± 0.6 | 2/6 (33.3) |

1/6 (16.7) |

2 leg graft wound infection (33.3) | |||

| Total | Exp | 9/53 (17) | 0/53 (0) | 6/46 (13) | ||||||||||

| Cont | 10/27 (37) | 8/27 (29.6) | 2/6 (33.3) | |||||||||||

AE adverse events, Cont control, CRA cardiac-related readmission, CRD cardiac-related death, Exp experimental, NA not available, NS not significant.

P-values in bold are statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05)

Demographic, preoperative, and intraoperative characteristics of the studies

A total of 87 patients, 60 patients in the treatment group, and 27 patients in the control group were enrolled in 7 studies [17–21, 27, 28]. Five NRCTs and two case reports were included. The mean age of the patients was over 50 years, varying from 20 to 75 years [17–21, 27, 28]. Studies reported a mean preoperative LVEF of 12–46.1%, with almost all studies, enrolled patients with an ejection fraction (EF) < 35% as the experimental group, except Nummi, et al. (15% < EF < 50%) [17–21, 27, 28].

The most common comorbidities reported in patients include hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and dyslipidemia, ranging from 30 to 100%, and almost all studies report more than half of their patients have at least 2 co-morbidities [17–21, 28]. Almost all of these patients were also receiving anti-hypertensive drugs with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin receptor blocker, B-blocker, diuretic, or other drug [17–21]. Antiplatelets were also administered in almost all patients ranging from 80 to 100% between studies [17–19, 21]. Most of the patients in each study had undergone revascularization therapy (PCI or CABG) except in the study by Nummi et al. in which patients from the experimental and control groups underwent CABG, together with cell sheet transplantation in the experimental group [17–21, 27, 28].

Almost all studies used autologous skeletal myoblasts as stem cells and all patients in the treatment group underwent thoracotomy as a method of transplantation [17–21, 27, 28]. Almost all studies used multiple sheets of cells (3–6 layers each, 5–6 sheets) with an average of 3–3.7 × 108 total cells transplanted [17–21, 27, 28]. Cells were transplanted into infarcted areas on the anterior and lateral walls of the left ventricle [17–21, 27, 28]. The standard treatment for the control group was CRT and CABG from two studies [17, 18]. Only the study by Nummi et al. used a single sheet with approximately 9.76 × 106 cells transplanted to the infarct area and the patient undergoing concurrent CABG [18]. The follow-up period varied from 3 months to 8.5 years [17–21, 27, 28].

Primary outcome

Almost all studies reported a significant increase in the percentage of LVEF after cell sheet transplantation (P < 0.05) [17, 19–21, 27, 28]. The study by Nummi et al. also reported an increase but did not report significance [18]. The study by Imamura et al. showed a significant difference in LVEF changes between the experimental and control groups (P < 0.001) [17]. In contrast, a study by Nummi et al. showed no significant difference between groups in changes in LVEF (P = 0.85) [18].

The same condition was found in the NYHA functional class, where almost all studies showed significant improvement after cell sheet transplantation (P < 0.05), except the study from Nummi et al. [17–21, 27, 28]. The study by Imamura et al. showed a significant increase in NYHA class in the experimental group compared to the control group (P < 0.001) [17], whereas Nummi et al. showed no difference in the experimental group and slight improvement in the control group (− 0.6 ± 0.6) [18].

A study by Miyagawa et al. reported continuous improvement in LVEF, left ventricular end-diastolic diameter (LVEDD), NYHA class, and plasma BNP level from baseline to 6 months and then all these variables reached statistical significance after 1 year (P < 0.05) [21]. Pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) measurement in 6 months and follow-up also shows significant improvement (P < 0.05) [21].

Kainuma et al. reported a significant sustained increase over time for all of these variables for 3 years of follow-up: LVEF, LVEDD, left ventricular end-systolic diameter, left ventricular end-diastolic volume index, left ventricular end-systolic volume index (LVESVI), NYHA class, level BNP plasma, 6 min walk test, and PVR [20]. These findings were mainly in the responders group, defined by patients whose LVEF improved or remained unchanged at 6 months of follow-up [20]. The responders group, which comprised 70% of the total patients in the study, had significantly larger preoperative left ventricle (LV) and dimensions, and also significantly higher preoperative estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) than the nonresponders group [20].

A study by Nummi et al. showed nonsignificant LVEF and NYHA class improvement after cell sheet transplantation after short, 3 months of follow-up [18]. But it showed significant improvement in infarction area thickness and thinnest wall thickness, even when compared to the control group [18].

Safety measurements

Three studies reported CRA in the experimental group in the follow-up period, ranging from 28.6 to 30.4% and the cumulative incidence rate for all studies was 17% [17, 19, 20]. Two studies reported CRA in the control group with a cumulative event rate of 37% [17, 18]. No CRD was reported in the experimental group, whereas two studies including the control group reported CRD with a cumulative incidence rate of 29.6% [17, 18].

A total of 5 non-CRD were reported in 2 studies [19, 20]. The study from Nummi et al. reported 1 sternal infection in the experimental group and 2 leg graft wound infections in the control group, but none of them required further intervention and were treated only with antibiotics [18]. No lethal arrhythmias were reported in any of the patients [17–21, 27, 28].

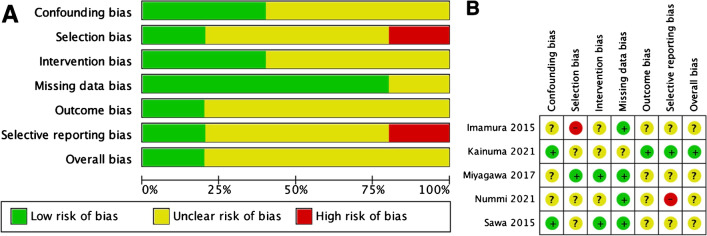

Risk of bias analysis

The assessment of the risk of bias in the included studies was measured by ROBINS-I for non-randomized studies because all included studies were not randomized. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Results of ROBINS-I assessment. A Risk of bias graph: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies using ROBINS-I for nonrandomized studies. B Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study using ROBINS-I for nonrandomized studies. ROBINS-I, Risk of Bias in Nonrandomized Intervention Studies

Discussion

Despite having been approved by the Ministry of Health in Japan for clinical use since 2017, the results of clinical studies of cell sheet transplantation for IHD were still very limited even when we used an extended search strategy [20]. Out of a total of 7 studies, we identified only 5 clinical trials that were eligible for analysis and 2 case reports [17–21, 27, 28]. In addition, this systematic review is the first to characterize the global literature regarding the outcome and safety of cell sheet transplantation in IHD for its use in the clinical setting.

The preclinical characteristics of patients between studies, although varied, did not differ significantly between the experimental and control groups in the two controlled studies [17, 18]. An interesting finding from included studies is that most of the patients included were patients with very low LVEF (< 35%) with a history of revascularization before [17, 19–21]. These patients were patients as “no option” IHD patients who were in actual need of heart transplantation but in the clinical setting, their queue lagged behind younger dilated cardiomyopathy patients [17, 19, 20, 27, 28]. This method can be emerging as a new option for these patients [20, 21].

The results of this study showed promising, safe, and feasible cell sheet transplantation for ischemic heart disease patients [17, 19–21, 27, 28]. LVEF and NYHA class showed significant post-transplantation improvement in almost all studies, even in patients with very low ejection fraction on standard treatment and with a history of previous revascularization (CABG or PCI) [17, 19–21, 27, 28]. This showed that cell sheet transplantation can improve cardiac function and functional outcomes even in IHD patients with end-stage heart failure with unsuccessful standard revascularization therapy [17, 19–21, 27, 28].

The mechanism by which cell sheet transplantation improves cardiac and functional outcomes in IHD patients can be seen through several different mechanisms, but each is connected to and supports other mechanisms [17–21, 27, 28]. Like other cell-based therapies, cell sheet transplantation also works primarily by the effect of secreted cytokines [17–21, 27, 28]. There are three main mechanisms of action of cell sheets in an ischemic heart. First, the paracrine effect of cytokines acts on hibernating myocardial tissue in ischemic and peri-ischemic myocardial tissue stimulates repair, inhibiting the process of myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy, then attenuating myocardial remodeling [18, 21, 27]. This leads to left ventricular (LV) reverse remodeling which leads to a global improvement in LV function, reflecting global improvement in the cardiac function [20]. Second, paracrine effects on ischemic and peri-ischemic areas also affect myocardial vessels, which amplifies the microcirculatory angiogenic response (angiogenesis) and also establishes mature myocardial arteries (arteriogenesis), ensuring long-term perfusion control and stability [18, 20, 28]. This ensures long-term, broader LV reverse remodeling, which again leads to global improvement in LV function [17, 18, 20, 28]. Third, cell sheets have advantages in the long-term survival of transplanted cells and engraftment [18, 29, 30]. This leads to a sustained long-term secretion of cytokines, which are postulated to affect diseased pulmonary vessels, by repairing them [20, 21, 28]. This mechanism, together with an increase in LV function that leads to a compensatory decrease in LV, will further reduce PVR and pulmonary hypertension (PH) [17, 18, 20, 21, 28]. As seen in the results of studies including PVR and PH measurement, there was a significant decrease in PVR and PH after sheet cell transplantation even in short-term follow-up (6 months) [20, 21]. The final result, an improvement of the patient’s functional outcome, will be achieved [20, 21]. A summary of the cell sheet mechanisms in improving patient outcomes is illustrated in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

How cell sheet transplants improve patient outcomes. The transplanted cell sheets release cytokines that exert paracrine and endocrine effects [18–21, 27, 28]. Paracrine effects on damaged myocardial tissue lead to tissue repair and reverse remodeling resulting in improved LV function [18, 20, 21, 27]. This is supported by a paracrine effect on cardiac vessels, stimulating angio and arteriogenesis and increasing myocardial tissue perfusion, ensuring continuous LV reverse remodeling [17, 18, 20, 28]. The continuous long-term endocrine effect of cytokines acts on the pulmonary vessels initiating and assisting the repair of diseased pulmonary vessels [21, 28]. This improvement in pulmonary vessels together with improved LV function led to a decrease in PVR and PH which improved the patient's functional outcome [17, 18, 20, 21, 28]. LV, left ventricle; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; PH, pulmonary hypertension; PVR, pulmonary vascular resistance

An interesting finding comes from a study by Nummi et al. who only reported clinical outcome measures after 3 months [18]. Almost all outcome variables showed non-significant differences between the experimental and control groups, but at the tissue-organ level, the thickness of the infarct area and the thickness of the thinnest wall showed a significant increase in the experimental group (cell sheet transplantation + CABG) compared to the control group (CABG only) [18]. These findings showed us that cell sheet transplantation might have insignificant clinical effects in the short term but have significant tissue-organ level effects that may contribute to long-term clinical improvement of IHD patients, as demonstrated in long-term studies [18, 20, 21, 28].

Another interesting result is from a long-term study by Kainuma et al., which gave us new insights about responders and nonresponders on cell sheet transplantation. Approximately 70% of patients who were responders would experience significant sustained improvement in almost all outcome variables over time and nonresponders would not, indicating to us that the criteria for selecting patients who will receive this therapy are important to achieve significant sustained improvement [20]. This study revealed significant differences in preoperative clinical baseline between responders and nonresponders which could be a clue [20]. Two main baseline clinical characteristics differ between responders and non-responders: left ventricular volume and dimensions, shown as LVESVI, and renal failure [20].

The volume and dimensions of the LV, rather than the LVEF, are believed to be determined by the extent of viable myocardial cells [20]. Thus, in nonresponders who have low LVESVI, viable myocardial cells may be too small in number to make an adequate response to the cell sheet transplantation [20, 31, 32]. Kainuma et al. demonstrated that LVESVI 70 ml/m2 was the cutoff point for determining whether a patient would respond to cell sheet transplantation or not [20].

Multivariate analysis performed by Kainuma et al. also revealed that preoperative renal failure was also associated with unsuccessful cell sheet transplantation [20]. Even mild preoperative renal failure or stage 3 chronic kidney disease (eGFR around 60 mg/mmol) was associated with non-responders [20]. This can be caused by two conditions: first, patients with renal failure may fail to fully receive recommended medical therapy postoperatively, and second, patients with renal failure may develop fluid volume overload leading to worsening of heart failure and thus continuing into a vicious cycle of worsening heart and kidney failure [20, 33].

The safety of cell sheet transplantation, measured by cardiac-related readmission, cardiac-related death, and adverse events, had a lower incidence in the experimental group compared to the control group either in each study or cumulatively [17–21, 27, 28]. No cardiac deaths or arrhythmias were reported in experimental groups in all studies demonstrating a very low risk of lethal cardiac events from cell sheet transplantation, and this method can evade the risk of arrhythmias attributed to direct cell injection [17–21, 27, 28]. Imamura et al. concluded that cell sheet transplantation could prevent cardiac death by improving cardiac function and functional outcomes [17]. This gave us a very important stepping stone for future studies that mortality and morbidity are not a cause for concern when these modalities are used in IHD patients. Surely, more clinical trials and long-term assessment reports should confirm these findings.

Limitations

Several limitations apply to our study. This systematic review only included non-randomized clinical trials and case reports due to the limited number of studies completed and the difficult randomized nature of studies. This could change the quality of research in terms of levels in the scientific evidence hierarchy. In addition, the parameters assessed and the follow-up period were inconsistent. Clinical outcomes were investigated in patients in the trials we presented over a period of 3–36 months, and most of the studies only provided data for 3–12 months, which reduces the value of outcome improvement that can be assessed as we have seen that the outcome improvement of successful transplantation can increase over time. In addition, the NYHA class results were clinical outcomes reviewed by medical personnel, implying that subjectivity and inter-examiner variation remains high. This can result in reporting results that do not accurately reflect the actual situation, which can be reduced through additional, more objective clinical investigations.

Conclusion

Despite limited clinical results, cell sheet transplantation can safely improve cardiac function and functional outcome in IHD patients, even at very low ejection fractions with a history of previous unsuccessful standard therapy. Better-designed clinical trials with long-term outcome assessments are needed to confirm these results.

Author contribution

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Ahmad Muslim Hidayat Thamrin, Tri Wisesa Soetisna and Andi Nurul Erisya Ramadhani. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Ahmad Muslim Hidayat Thamrin and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The authors confirm that this research received no external funding.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all the data supporting the findings of this study are currently available in the article.

Declarations

All authors have read, reviewed, and approved the submitted manuscript to be submitted to the Indian Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery; the manuscript is original and has not been submitted elsewhere in part or in whole.

Ethical statement

This study did not use human or animal subject(s), so ethical clearance was not applied to our study.

Informed consent

This study analyzed previously published data and no new patient data was used. As a result, patient consent was deemed waived.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Li Z, Lin L, Wu H, Yan L, Wang H, Yang H, et al. Global, regional, and national death, and disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for cardiovascular disease in 2017 and trends and risk analysis from 1990 to 2017 using the global burden of disease study and implications for prevention. Front Public Health. 2021;9:559751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Gheorghe A, Griffiths U, Murphy A, Legido-Quigley H, Lamptey P, Perel P. The economic burden of cardiovascular disease and hypertension in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:975. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5806-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2022;145:e18-e114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Dababneh E, Goldstein S. Chronic ischemic heart disease selection of treatment modality [Internet]. StatPearls. 2022. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/0. Accessed 15 Feb 2023. [PubMed]

- 6.Yu H, Lu K, Zhu J, Wang J. Stem cell therapy for ischemic heart diseases. Br Med Bull. 2017;121:135–154. doi: 10.1093/bmb/ldw059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hashimoto H, Olson EN, Bassel-Duby R. Therapeutic approaches for cardiac regeneration and repair. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2018;15:585–600. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0036-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jessup M, Drazner MH, Book W, Cleveland JC, Dauber I, Farkas S, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA/ISHLT/ACP advanced training statement on advanced heart failure and transplant cardiology (revision of the ACCF/AHA/ACP/HFSA/ISHLT 2010 Clinical Competence Statement on Management of Patients With Advanced Heart Failure and Cardiac Transplant): a report of the ACC competency management committee. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69:2977–3001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Liu C, Han D, Liang P, Li Y, Cao F. The current dilemma and breakthrough of stem cell therapy in ischemic heart disease. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:636136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Gyöngyösi M, Haller PM, Blake DJ, Rendon EM. Meta-analysis of cell therapy studies in heart failure and acute myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2018;123:301–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Wang Y, Xu F, Ma J, Shi J, Chen S, Liu Z, et al. Effect of stem cell transplantation on patients with ischemic heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:125. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1214-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo R, Morimatsu M, Feng T, Lan F, Chang D, Wan F, et al. Stem cell-derived cell sheet transplantation for heart tissue repair in myocardial infarction. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2020;11:19. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1536-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munderere R, Kim S-H, Kim C, Park S-H. The progress of stem cell therapy in myocardial-infarcted heart regeneration: cell sheet technology. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2022;19:969–986. doi: 10.1007/s13770-022-00467-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuura K, Haraguchi Y, Shimizu T, Okano T. Cell sheet transplantation for heart tissue repair. J Control Release. 2013;169:336–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arjmand B, Abedi M, Arabi M, Alavi-Moghadam S, Rezaei-Tavirani M, Hadavandkhani M, et al. Regenerative medicine for the treatment of ischemic heart disease; status and future perspectives. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:704903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Chang D, Fan T, Gao S, Jin Y, Zhang M, Ono M. Application of mesenchymal stem cell sheet to treatment of ischemic heart disease. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2021;12:384. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02451-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Imamura T, Kinugawa K, Sakata Y, Miyagawa S, Sawa Y, Yamazaki K, et al. Improved clinical course of autologous skeletal myoblast sheet (TCD-51073) transplantation when compared to a propensity score-matched cardiac resynchronization therapy population. J Artif Organs. 2016;19:80–86. doi: 10.1007/s10047-015-0862-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nummi A, Mulari S, Stewart JA, Kivistö S, Teittinen K, Nieminen T, et al. Epicardial transplantation of autologous cardiac micrografts during coronary artery bypass surgery. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:726889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Sawa Y, Yoshikawa Y, Toda K, Fukushima S, Yamazaki K, Ono M, et al. Safety and efficacy of autologous skeletal myoblast sheets (TCD-51073) for the treatment of severe chronic heart failure due to ischemic heart disease. Circ J. 2015;79:991–999. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kainuma S, Miyagawa S, Toda K, Yoshikawa Y, Hata H, Yoshioka D, et al. Long-term outcomes of autologous skeletal myoblast cell-sheet transplantation for end-stage ischemic cardiomyopathy. Mol Ther. 2021;29:1425–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2021.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyagawa S, Domae K, Yoshikawa Y, Fukushima S, Nakamura T, Saito A, et al. Phase I clinical trial of autologous stem cell–sheet transplantation therapy for treating cardiomyopathy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e003918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336–341. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins J, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page M, et al. (eds.). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane; 2020.41-48.

- 24.The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.4. Copenhagen: The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020.

- 25.Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Lo CK-L, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers’ to authors’ assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Yoshida S, Miyagawa S, Toda K, Domae K, Sawa Y. Skeletal myoblast sheet transplantation enhanced regional improvement of cardiac function. Eur Hear J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19:828–829. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jey064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamamoto R, Miyagawa S, Toda K, Kainuma S, Yoshioka D, Yoshikawa Y, et al. Long-term outcome of ischemic cardiomyopathy after autologous myoblast cell-sheet implantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;108:e303–e306. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2019.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shudo Y, Miyagawa S, Fukushima S, Saito A, Shimizu T, Okano T, et al. Novel regenerative therapy using cell-sheet covered with omentum flap delivers a huge number of cells in a porcine myocardial infarction model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;142:1188–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sekine H, Shimizu T, Dobashi I, Matsuura K, Hagiwara N, Takahashi M, et al. Cardiac cell sheet transplantation improves damaged heart function via superior cell survival in comparison with dissociated cell injection. Tissue Eng Part A. 2011;17:2973–2980. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2010.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bonow RO, Maurer G, Lee KL, Holly TA, Binkley PF, Desvigne-Nickens P, et al. Myocardial viability and survival in ischemic left ventricular dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1617–1625. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rizzello V, Poldermans D, Biagini E, Schinkel AFL, Boersma E, Boccanelli A, et al. Prognosis of patients with ischaemic cardiomyopathy after coronary revascularisation: relation to viability and improvement in left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart. 2009;95:1273–1277. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.163972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ronco C, McCullough P, Anker SD, Anand I, Aspromonte N, Bagshaw SM, et al. Cardio-renal syndromes: report from the consensus conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:703–711. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all the data supporting the findings of this study are currently available in the article.