Abstract

The ovarian circadian clock plays a regulatory role in the avian ovulation-oviposition cycle. However, little is known regarding the ovarian circadian clock of geese. In this study, we investigated rhythmic changes in clock genes over a 48-h period and identified potential clock-controlled genes involved in progesterone synthesis in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. The results showed that BMAL1, CRY1, and CRY2, as well as 4 genes (LHR, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B) involved in progesterone synthesis exhibited rhythmic expression patterns in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells over a 48-h period. Knockdown of BMAL1 decreased the progesterone concentration and downregulated STAR mRNA and protein levels in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. Overexpression of BMAL1 increased the progesterone concentration and upregulated the STAR mRNA level in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. Moreover, we demonstrated that the BMAL1/CLOCK complex activated the transcription of goose STAR gene by binding to an E-box motif. These results suggest that the circadian clock is involved in the regulation of progesterone synthesis in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells by orchestrating the transcription of steroidogenesis-related genes.

Key words: goose, circadian clock, BMAL1, STAR, granulosa cell

INTRODUCTION

Organisms on Earth produce a rhythm with a 24-h cycle to adapt to day-night variations in the environment, which is known as the circadian rhythm. Circadian rhythms are driven by circadian clocks. Circadian clocks are cell-autonomous molecular oscillators that pervade a wide range of physiological, metabolic, and behavioral processes. The suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus is the central clock in mammals (Mohawk et al., 2012). Unlike mammals, avian circadian rhythms are regulated by 3 separate center clocks located in the retina, pineal gland, and SCN of the hypothalamus (Cassone, 2014). It is now known that circadian clocks are localized in central tissues as well as in peripheral tissues such as livers (Tahara and Shibata, 2016), kidneys (Firsov and Bonny, 2018), and ovaries (Sellix and Menaker, 2010). The central and peripheral circadian clocks mutually orchestrate diurnal rhythms of various physiological and behavioral processes.

In mammals, circadian clocks consist of a highly conserved set of genes, collectively referred to as “clock genes.” The core mechanism of circadian clocks relies on the interlocked transcriptional-translational feedback loops of clock genes (Cox and Takahashi, 2019). Circadian Locomotor Output Cycles Kaput (CLOCK) and brain and muscle ARNT-like protein 1(BMAL1) genes are primary drivers of positive regulation. The CLOCK/BMAL1 complex activates the transcription of Period (PER) and Cryptochrome (CRY) by binding to the E-box motifs present in their promoters. PER and CRY act as negative regulators. They dimerize and translocate to the nucleus, where they repress transcription by interacting directly with CLOCK/BMAL1. The CLOCK/BMAL1 complex is released from feedback inhibition until the PER/CRY complex is degraded. The molecular mechanisms underlying circadian rhythms are highly conserved between mammalian and avian species (Cassone, 2014). Avian circadian clock genes exhibit rhythmic expression in the central tissues (hypothalamus and pineal gland) and peripheral tissues (liver, ovary, uterus, and pancreas) (Tischkau et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2016, 2022, 2023; Song et al., 2023).

The ovulation and oviposition behaviors in poultry are characterized by pronounced circadian rhythms (Silver, 1986; Nakao et al., 2007). Oviposition usually occurs 15 to 30 min before ovulation. The ovulation-oviposition cycle in chickens and quails is 24 to 27 h (Nakao et al., 2007), whereas it is approximately 48 h in geese (Qin et al., 2013). The ovulation of the largest (F1) preovulatory follicle in avian ovaries is triggered by a pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) surge caused by the positive feedback of progesterone (Johnson et al., 1985). Progesterone is predominantly synthesized in the granulosa layer of F1. Previous studies in quail and chickens have indicated that the ovarian circadian clock is involved in regulating the avian ovulation-oviposition cycle (Nakao et al., 2007; Yoshikawa et al., 2009; Tischkau et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2017). However, little is known regarding the ovarian circadian clock of laying geese. In the present study, we investigated rhythmic changes in clock genes over a 48-h period and identified potential clock-controlled genes involved in progesterone synthesis in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval

Animal experiments were approved by the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences Experimental Animal Ethics Committee and performed according to the Regulations for the Administration of Affairs Concerning Experimental Animals (Decree No. 63 of the Jiangsu Academy of Agricultural Sciences, July 8, 2014).

Granulosa Cell Isolation

Granulosa layers were collected from the 3 largest preovulatory follicles (F1–F3) of a laying Yangzhou goose for each experiment as described previously (Chen et al., 2020). All experiments were repeated 3 times. After washing with precooled phosphate-buffered saline, granulosa layers were pooled and incubated with 0.1% collagenase II (Gibco, Waltham, MA) for 15 min at 37°C. Collagenase was inactivated by adding Medium 199 (M199; Gibco) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The dispersed solution was filtered through a 70-μm cell strainer. Granulosa cells were precipitated by centrifugation and resuspended in M199 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Cell number and viability were estimated using trypan blue staining.

Granulosa Cell Synchronization

Purified goose granulosa cells were plated in 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) and cultured with M199 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, confluent granulosa cells were synchronized using 100 nM dexamethasone (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) for 2 h in serum-free M199 containing 1% penicillin-streptomycin. The medium was then replaced with M199 containing 5% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin. Samples were collected every 4 h for 48 h (3 replicates for each time point). Cell culture media were collected for hormone measurements. Cells were harvested using Buffer RL plus 1% β-mercaptoethanol (supplied in the RNAprep Pure Tissue Kit; Tiangen, Beijing, China) for RNA isolation.

Construction of Plasmids pcDNA3.1-BMAL1 and pcDNA3.1-CLOCK

The coding sequence of goose BMAL1 (NW_025927712) was synthesized de novo and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector between BamHI and EcoRI sites. The coding sequence of goose CLOCK (NW_025927882) was synthesized de novo and subcloned into the pcDNA3.1(+) vector between BamHI and XhoI sites. The recombinant plasmids were confirmed through sequencing and enzymatic digestion.

BMAL1 Overexpression in Granulosa Cells

Purified goose granulosa cells were plated in 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) and cultured with M199 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with M199 containing 5% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 1 μg of either pcDNA3.1(+) empty vector or recombinant plasmid pcDNA3.1-BMAL1, diluted in Opti-MEM medium, was transfected into granulosa cells using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA), according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h, cell culture media were collected for hormone measurements, and cells were harvested for RNA isolation. Meanwhile, cells were collected into RIPA lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) for protein isolation. Six replicates were set for each treatment.

Small Interfering RNA Transfection

An effective small interfering RNA (siRNA) targeting goose BMAL1 mRNA and a negative control (NC) siRNA were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The RNA oligonucleotide sequences are listed in Table S1. Purified goose granulosa cells were plated in 12-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well) and cultured with M199 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with M199 containing 5% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin and 20 pmol of each siRNA, diluted in Opti-MEM medium, was transfected into granulosa cells using Lipofectamine 3000 reagent, according to the manufacturer's protocol. After 24 h, cell culture media were collected for hormone measurements, and cells were harvested for RNA isolation or protein isolation. Six replicates were set for each treatment.

Cell Proliferation

Purified goose granulosa cells were plated in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells per well) and performed in parallel with treatments used in BMAL1 overexpression and siRNA transfection experiments. After 24 h, granulosa cells proliferation was assessed using a CCK-8 kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Absorption was measured at 450 nm to determine the effect of treatment on cell proliferation. Twelve replicates were set for each treatment.

Construction of STAR Promoter and E-Box Mutation

A 1,000-bp sequence upstream of ATG in the promoter region of goose STAR (NW_025927830) was synthesized and subcloned into the pGL3-Basic vector between KpnI and HindIII sites. The resulting plasmid was named pGL3-STAR. A plasmid containing the mutated E-box (GGACCT) was constructed using the same method and named pGL3-STAR-mut.

Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

The Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cell line was used. Cells were plated in 96-well plates (2 × 104 cells/well) and cultured in F-12K medium (Invitrogen) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, the medium was replaced, and 100 ng of plasmid DNA mixture was added to each well using the Lipofectamine 3000 reagent. Plasmids pGL3-STAR or pGL3-STAR-mut were cotransfected with either pcDNA3.1-BMAL1 (10 ng) and pcDNA3.1-CLOCK (10 ng) expression vectors or with pcDNA3.1 empty vector. Cells were also cotransfected with the internal control pRL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid. Transcriptional activity was determined 24 h after transfection using the Dual-Glo Luciferase Assay System and GloMax-Multi Detection System (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity in each well. Three replicates were set for each treatment.

Purified goose granulosa cells were plated in 96-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) and cultured in M199 containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. After 24 h, the medium was replaced with M199 containing 5% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, and cells were performed in parallel with treatments used in the CHO cell culture in replicates of 3. Transcriptional activity was determined 24 h after transfection.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction

RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis, and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) were performed as described previously (Chen et al., 2020). Primers were obtained from our previous study (Chen et al., 2020), including glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), LH receptor (LHR ), Steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR ), cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (CYP11A1), and 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD3B). Other primers were designed using the Oligo 7 software, as shown in Table S2. Relative mRNA levels were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001).

Hormone Measurements

Progesterone concentrations in cell culture media were determined by ELISA as described previously (Yan et al., 2022).

Immunoblotting

Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE under denaturing conditions, and then transferred onto the PVDF membrane. The membrane was blocked in Tris buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) with 5% dry milk, and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, the membrane was incubated for 2 h at room temperature with a goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:1,000; Beyotime). Protein bands were detected using a chemiluminescence system and quantified by densitometry using Image J software. The polyclonal rabbit anti-STAR antibody was made in a rabbit against the recombinant goose STAR protein (XP_013049898) and purified by antigen-affinity chromatography as described previously (Chen et al., 2022). The GAPDH (D16H11) Rabbit mAb was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Differences were analyzed using 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test. An independent sample t test was used to compare 2 groups. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 26. Circadian rhythmicity of gene expression was detected using CosinorOnline program (https://cosinor.online/app/cosinor.php), and the period was set at 48 h.

RESULTS

Rhythmic Changes of Clock Genes in Goose Ovarian Preovulatory Granulosa Cells

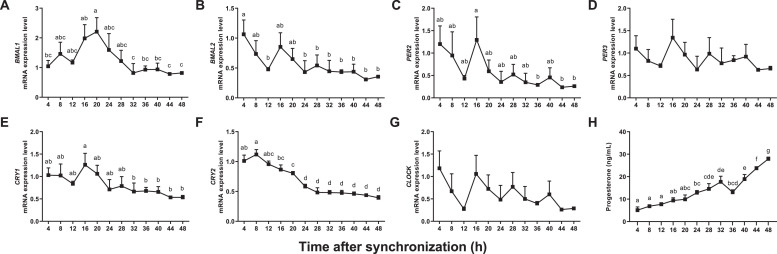

The mRNA levels of 7 clock genes were determined in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells over a 48-h period. After the synchronization treatment, the mRNA level of BMAL1 increased gradually to a peak and then decreased to the initial level (Figure 1A). The mRNA levels of BMAL2, PER2, PER3, CRY1, and CLOCK showed a similar decrease and increase, and then decreased and remained at a lower level (Figure 1B–F and G). The mRNA level of CRY2 decreased over time and then remained low (Figure 1F). The rhythmic characteristics of all clock genes are summarized in Table 1. The mRNA levels of BMAL1, CRY1, and CRY2 showed pronounced circadian rhythms (P < 0.05). The peak value is at 18.07, 14.88, and 11.72 h for BMAL1, CRY1, and CRY2 genes, respectively.

Figure 1.

Changes of mRNA levels of clock genes (BMAL1, BMAL2, PER2, PER3, CRY1, CRY2, and CLOCK) (A–G) and progesterone concentrations (H) in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells synchronized with dexamethasone. a–g represent a significant difference among the means (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Rhythmic characteristics of clock genes and steroidogenic enzyme genes in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells.

| Genes | Mesor | Amplitude | Acrophase (h) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMAL1 | 1.25 | 0.55 | 18.07 | 0.00 |

| BMAL2 | 0.56 | 0.18 | 11.89 | 0.14 |

| PER2 | 0.58 | 0.32 | 11.74 | 0.09 |

| PER3 | 0.86 | 0.10 | 16.73 | 0.54 |

| CRY1 | 0.81 | 0.25 | 14.88 | 0.01 |

| CRY2 | 0.67 | 0.31 | 11.72 | 0.00 |

| CLOCK | 0.60 | 0.16 | 15.20 | 0.48 |

| LHR | 0.65 | 0.55 | 13.52 | 0.00 |

| STAR | 2.59 | 1.62 | 26.88 | 0.00 |

| CYPLLA1 | 0.45 | 0.47 | 11.38 | 0.00 |

| HSD3B | 2.00 | 1.98 | 15.99 | 0.00 |

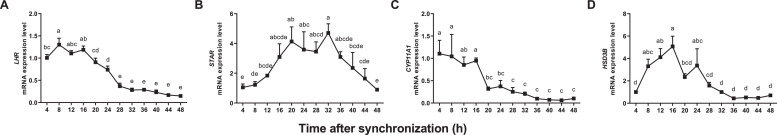

Rhythmic Changes of Progesterone and Genes Involved in Its Synthesis in Goose Ovarian Preovulatory Granulosa Cells

Progesterone concentrations and mRNA levels of 4 genes involved in progesterone synthesis were determined in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells over a 48-h period. After the synchronization treatment, the progesterone concentration increased gradually over time, except that there was a transient decrease at 36 h (Figure 1H). There was no circadian rhythm observed in progesterone concentrations. The mRNA levels of LHR and CYP11A1 decreased over time and then remained at lower levels (Figure 2A and C). The mRNA level of STAR increased gradually to a peak and then decreased to the initial level (Figure 2B). The change in HSD3B mRNA level was similar to that of STAR, except that the peak of the former was earlier than that of STAR (Figure 2D). The rhythmic characteristics of these 4 genes are summarized in Table 1. The mRNA levels of all genes showed pronounced circadian rhythms (P < 0.05). The amplitudes of STAR and HSD3B were higher than those of LHR and CYP11A1. The peak value is at 13.52, 26.88, 11.38, and 15.99 h for LHR, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B, respectively.

Figure 2.

Changes of mRNA levels of LHR, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B genes (A–D) in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells synchronized with dexamethasone. a–e represent a significant difference among the means (P < 0.05).

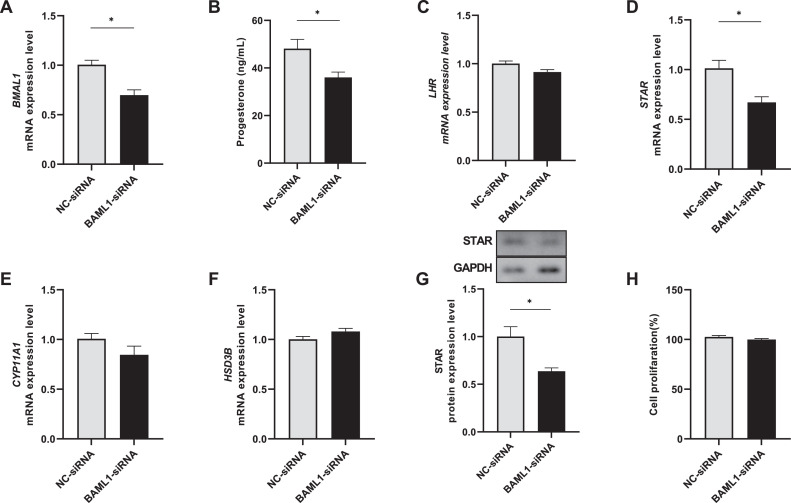

Effect of BMAL1 Knockdown on Progesterone, Gene Expression, and Cell Proliferation in Goose Ovarian Preovulatory Granulosa Cells

Compared with the NC siRNA, the targeted siRNA showed a significant silencing effect on the BMAL1 mRNA level in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells (Figure 3A). Knockdown of BMAL1 significantly decreased the progesterone concentration (Figure 3B) and downregulated the STAR mRNA level, but it did not affect mRNA levels of LHR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B (Figure 3C, E, and F). The STAR protein level was downregulated corresponding to its mRNA level (Figure 3G). The granulosa cell proliferation was not affected following BMAL1 knockdown (Figure 3H).

Figure 3.

Effect of BMAL1 knockdown (A) on progesterone (B), gene expression (C–G), and cell proliferation (H) in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. BMAL1-siRNA represents the siRNA targeting goose BMAL1; NC-siRNA represents the negative control siRNA. * represents a significant difference between the 2 groups (P < 0.05).

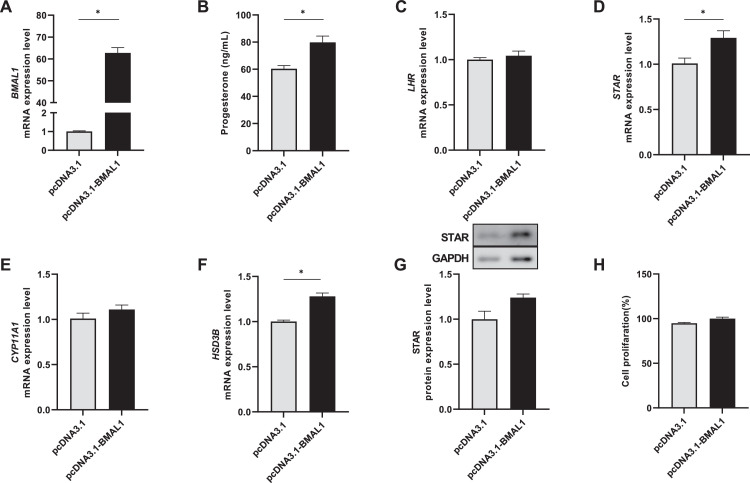

Effect of BMAL1 Overexpression on Progesterone, Gene Expression, and Cell Proliferation in Goose Ovarian Preovulatory Granulosa Cells

The recombinant expression vector pcDNA3.1‐BMAL1 was constructed. The BMAL1 mRNA level was significantly upregulated by transfection with the recombinant plasmid compared with the negative control (vector plasmid) in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells (Figure 4A). Overexpression of BMAL1 significantly increased the progesterone concentration (Figure 4B) and upregulated mRNA levels of STAR and HSD3B, but it did not affect mRNA levels of LHR and CYP11A1 (Figure 4C–F). Correspondingly, the STAR protein level was downregulated but there was no significant difference (Figure 4G). The granulosa cell proliferation was not affected following BMAL1 overexpression (Figure 4H).

Figure 4.

Effect of BMAL1 overexpression (A) on progesterone (B), gene expression (C–G), and cell proliferation (H) in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. * represents a significant difference between the 2 groups (P < 0.05).

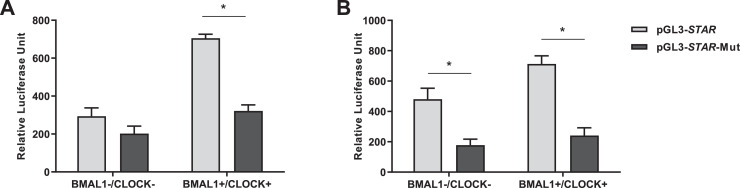

CLOCK/BMAL1 Drives the Transcriptional Activation of Goose STAR

An E-box motif (CACGTG), which is the putative binding site for the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex, was found in the promoter region of the goose STAR gene at position −695 to −700 bp upstream of ATG. To obtain evidence that the CLOCK/BMAL1 complex is involved in the transcription of the goose STAR gene, luciferase assays were conducted in CHO and goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. In CHO cells, the wild-type STAR promoter construct showed increased transcriptional activity in the presence of CLOCK/BMAL1, whereas the mutant STAR promoter construct was not responsive to CLOCK/BMAL1 (Figure 5A). Similar results were observed in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells (Figure 5B). In addition, the transcriptional activity of the mutant STAR promoter construct decreased in the absence of CLOCK/BMAL1.

Figure 5.

Transcriptional activation of goose STAR gene in CHO cells (A) or goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells (B) by cotransfecting with (+) or without (−) CLOCK and BMAL1 expression vectors. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. * represents a significant difference between the 2 groups (P < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The timing of ovulation in poultry is controlled by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, which is also affected by the circadian rhythm system. The ovarian circadian clock has been documented in many species and its function is related to the timing of gene expression in mature granulosa cells (Sen and Hoffmann, 2020; Li et al., 2023). Geese are characterized by a 48-h period of ovulation-oviposition cycle. In this study, granulosa layers of ovarian preovulatory F1 to F3 follicles were collected from laying geese and cultured for 48 h to determine mRNA levels of 7 clock genes. Previous studies have suggested that avian ovarian clock genes are regulated by pituitary gonadotropins such as LH (Yoshikawa et al., 2009; Tischkau et al., 2011; Li et al., 2014). To determine whether there is a fundamental cell-autonomous oscillator in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells, we did not administer exogenous gonadotropins to cell cultures in this study. It was found that BMAL1, CRY1, and CRY2 genes exhibited pronounced circadian rhythms in expression over the 48-h period, suggesting that there was a fundamental cell-autonomous rhythm of clock genes in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. This result is comparable to the findings that rhythmic expression was observed for BMAL1 and CRY1 over a 24-h period in hen ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells (Li et al., 2014). A previous in vivo study showed that BMAL1 and CRY2 genes exhibit antiphase patterns of rhythmic expression in the granulosa layer of the preovulatory F1 follicle in laying hens (Zhang et al., 2017). However, BMAL1 showed no antiphase pattern of expression with CRY2 gene in this study. This discrepancy in phase alignment may result from differences in species or variability in granulosa cell cultures. Granulosa cells cultured in vitro are not regulated by endocrine factors and the central clock.

In this study, progesterone concentrations and mRNA levels of 4 genes (LHR, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B) involved in progesterone synthesis (Li and Johnson, 1993; Nitta et al., 1993; Johnson et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 2002), were determined in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells over a 48-h period. It was found that the progesterone concentration increased gradually with time and did not show a circadian rhythm. The increased progesterone concentration is also not consistent with the reduced mRNA levels of LHR, STAR, CYP11A1, and HSD3B. Progesterone synthesis is one of the essential physiological functions of avian preovulatory granulosa cells, which is beneficial to cell survival and follicle maturation. It is possible that the progesterone metabolism has not been initiated. Although there was no circadian rhythm in progesterone concentration, all 4 genes involved in progesterone synthesis showed pronounced circadian rhythms in mRNA expression, suggesting that they are potentially clock-controlled genes. Among them, the expression patterns of STAR and HSD3B genes were similar to that of BMAL1, supporting that there is a potential regulatory relationship.

BMAL1 is a core component of the circadian clock, and its deficiency causes reproductive dysfunction in mice (Alvarez et al., 2008; Ratajczak et al., 2009; Boden et al., 2010). A significant reduction in serum progesterone or testosterone levels is observed in BMAL1 knockout mice, which is related to decreased STAR mRNA levels in the ovaries or testes (Alvarez et al., 2008; Boden et al., 2010). An increasing number of in vitro studies show that BMAL1 knockdown downregulates mRNA levels of steroidogenesis-related genes (such as LHR, STAR, CYP11A1, or HSD3B) in granulosa cells and Leydig cells (Chen et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2021). However, the involvement of BMAL1 in the regulation of avian steroid hormone synthesis remains unclear. In this study, BMAL1 knockdown decreased the progesterone concentration and BMAL1 overexpression increased it in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells, suggesting that BMAL1 may be involved in the progesterone synthesis. It was further found that BMAL1 knockdown inhibited the STAR mRNA level and BMAL1 overexpression stimulated it, suggesting that BMAL1 may be involved in progesterone synthesis by regulating the STAR mRNA expression. These results also indicate that BMAL1 has a conserved function in reproductive biology between mammalian and avian species. It was noted that BMAL1 overexpression upregulates the HSD3B mRNA level, but BMAL1 knockdown did not affect it in this study. The granulosa cell proliferation was not affected following BMAL1 knockdown or overexpression.

In this study, the identification of an E-box motif in the promoter region of goose STAR suggested a putative binding site for CLOCK/BMAL1. By a luciferase reporter gene assay, we demonstrated that the wild-type STAR promoter construct showed enhanced transcriptional activity in the presence of CLOCK/BMAL1 in CHO cells, whereas the mutant STAR promoter construct was unresponsive to CLOCK/BMAL1. Similar results were observed in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. These results suggested that STAR is a clock-controlled gene, which is consistent with previous observations describing that there is a direct effect of BMAL1 on STAR expression in quails and mice (Nakao et al., 2007; Alvarez et al., 2008). The STAR expression is necessary for the initiation of progesterone synthesis followed by the preovulatory surge of progesterone. Therefore, the significance of clock-controlled STAR expression in ovarian preovulatory follicles may be related to the timing of their maturation and ovulation. In addition, decreased transcriptional activity of the mutant STAR promoter construct was observed in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells in the absence of CLOCK/BMAL1, which may be attributed to the endogenous CLOCK/BMAL1 complex.

In conclusion, the present study revealed that circadian clock genes and genes involved in progesterone synthesis exhibit rhythmic expression patterns in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. Importantly, we demonstrated that BMAL1 is involved in progesterone synthesis by regulating the transcription of STAR gene. These findings suggest that the circadian clock is involved in the regulation of progesterone synthesis in goose ovarian preovulatory granulosa cells. Further studies are needed to determine that whether the circadian control of progesterone within preovulatory follicles is involved in regulating the ovulation-oviposition cycle in geese.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by Jiangsu Seed Industry Revitalization Project (grant number JBGS[2021]023) and Jiangsu Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Fund (grant number CX (20) 3148).

DISCLOSURES

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in the present study.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found in the online version at doi:10.1016/j.psj.2023.103159.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- Alvarez J.D., Hansen A., Ord T., Bebas P., Chappell P.E., Giebultowicz J.M., Williams C., Moss S., Sehgal A. The circadian clock protein BMAL1 is necessary for fertility and proper testosterone production in mice. J. Biol. Rhythms. 2008;23:26–36. doi: 10.1177/0748730407311254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boden M.J., Varcoe T.J., Voultsios A., Kennaway D.J. Reproductive biology of female Bmal1 null mice. Reproduction. 2010;139:1077–1090. doi: 10.1530/REP-09-0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassone V.M. Avian circadian organization: a chorus of clocks. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2014;35:76–88. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Dai Z.C., Zhu H.X., Lei M.M., Li Y., Shi Z.D. Active immunization against AMH reveals its inhibitory role in the development of pre-ovulatory follicles in Zhedong White geese. Theriogenology. 2020;144:185–193. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Guo R.H., Lei M.M., Zhu H.X., Yan L.Y., Shi Z.D. Research note: development of a sandwich ELISA for determining plasma growth hormone concentrations in goose. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhao L., Kumazawa M., Yamauchi N., Shigeyoshi Y., Hashimoto S., Hattori M.A. Downregulation of core clock gene Bmal1 attenuates expression of progesterone and prostaglandin biosynthesis-related genes in rat luteinizing granulosa cells. Am. J Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2013;304:C1131–C1140. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00008.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox K.H., Takahashi J.S. Circadian clock genes and the transcriptional architecture of the clock mechanism. J Mol. Endocrinol. 2019;63:R93–R102. doi: 10.1530/JME-19-0153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding H., Zhao J., Liu H., Wang J., Lu W. BMAL1 knockdown promoted apoptosis and reduced testosterone secretion in TM3 Leydig cell line. Gene. 2020;747 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2020.144672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firsov D., Bonny O. Circadian rhythms and the kidney. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2018;14:626–635. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.L., Bridgham J.T., Wagner B. Characterization of a chicken luteinizing hormone receptor (cLH-R) complementary deoxyribonucleic acid, and expression of cLH-R messenger ribonucleic acid in the ovary. Biol. Reprod. 1996;55:304–309. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod55.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P.A., Johnson A.L., van Tienhoven A. Evidence for a positive feedback interaction between progesterone and luteinizing hormone in the induction of ovulation in the hen, Gallus domesticus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1985;58:478–485. doi: 10.1016/0016-6480(85)90122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A.L., Solovieva E.V., Bridgham J.T. Relationship between steroidogenic acute regulatory protein expression and progesterone production in hen granulosa cells during follicle development. Biol. Reprod. 2002;67:1313–1320. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod67.4.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Johnson A.L. Regulation of P450 cholesterol side-chain cleavage messenger ribonucleic acid expression and progesterone production in hen granulosa cells. Biol. Reprod. 1993;49:463–469. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod49.3.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Zhang Z., Peng J., Wang Y., Zhu Q. Cooperation of luteinizing hormone signaling pathways in preovulatory avian follicles regulates circadian clock expression in granulosa cell. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2014;394:31–41. doi: 10.1007/s11010-014-2078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Zhang H., Wang Y., Li D., Chen H. Advances in circadian clock regulation of reproduction. Adv. Protein Chem. Struct. Biol. 2023;137:83–133. doi: 10.1016/bs.apcsb.2023.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohawk J.A., Green C.B., Takahashi J.S. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2012;35:445–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-153128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakao N., Yasuo S., Nishimura A., Yamamura T., Watanabe T., Anraku T., Okano T., Fukada Y., Sharp P.J., Ebihara S., Yoshimura T. Circadian clock gene regulation of steroidogenic acute regulatory protein gene expression in preovulatory ovarian follicles. Endocrinology. 2007;148:3031–3038. doi: 10.1210/en.2007-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitta H., Mason J.I., Bahr J.M. Localization of 3 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase in the chicken ovarian follicle shifts from the theca layer to granulosa layer with follicular maturation. Biol. Reprod. 1993;48:110–116. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod48.1.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q., Sun A., Guo R., Lei M., Ying S., Shi Z. The characteristics of oviposition and hormonal and gene regulation of ovarian follicle development in Magang geese. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2013;11:65. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-11-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratajczak C.K., Boehle K.L., Muglia L.J. Impaired steroidogenesis and implantation failure in Bmal1-/- mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150:1879–1885. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellix M.T., Menaker M. Circadian clocks in the ovary. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2010;21:628–636. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2010.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sen A., Hoffmann H.M. Role of core circadian clock genes in hormone release and target tissue sensitivity in the reproductive axis. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2020;501 doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2019.110655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver R. Circadian and interval timing mechanisms in the ovulatory cycle of the hen. Poult. Sci. 1986;65:2355–2362. doi: 10.3382/ps.0652355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song C., Wang Z., Cao J., Dong Y., Chen Y. Role of melatonin in daily variations of plasma insulin level and pancreatic clock gene expression in chick exposed to monochromatic light. Int. J Mol. Sci. 2023;24:2368. doi: 10.3390/ijms24032368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tahara Y., Shibata S. Circadian rhythms of liver physiology and disease: experimental and clinical evidence. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2016;13:217–226. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2016.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tischkau S.A., Howell R.E., Hickok J.R., Krager S.L., Bahr J.M. The luteinizing hormone surge regulates circadian clock gene expression in the chicken ovary. Chronobiol. Int. 2011;28:10–20. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2010.530363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Yin L., Bai L., Ma G., Zhao C., Xiang A., Pang W., Yang G., Chu G. Bmal1 interference impairs hormone synthesis and promotes apoptosis in porcine granulosa cells. Theriogenology. 2017;99:63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y., Zhao L., Li W., Wang X., Ma T., Yang L., Gao L., Li C., Zhang M., Yang D., Zhang J., Jiang H., Zhao H., Wang Y., Chao H.W., Wang A., Jin Y., Chen H. Circadian clock gene BMAL1 controls testosterone production by regulating steroidogenesis-related gene transcription in goat Leydig cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2021;236:6706–6725. doi: 10.1002/jcp.30334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Hu M., Gu L., Lei M., Chen Z., Zhu H., Chen R. Effect of heat stress on egg production, steroid hormone synthesis, and related gene expression in chicken preovulatory follicular granulosa cells. Animals. 2022;12:1467. doi: 10.3390/ani12111467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T., Sellix M., Pezuk P., Menaker M. Timing of the ovarian circadian clock is regulated by gonadotropins. Endocrinology. 2009;150:4338–4347. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Du X., Lai S., Shu G., Zhu Q., Tian Y., Li D., Wang Y., Yang J., Zhang Y., Zhao X. A transcriptome analysis for 24-hour continuous sampled uterus reveals circadian regulation of the key pathways involved in eggshell formation of chicken. Poult. Sci. 2022;101 doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z., Lai S., Wang Y., Li L., Yin H., Wang Y., Zhao X., Li D., Yang M., Zhu Q. Rhythmic expression of circadian clock genes in the preovulatory ovarian follicles of the laying hen. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Li Y., Yuan Y., Wang J., Zhang S., Zhu R., Wang Y., Wu Y., Liao X., Mi J. Reducing light exposure enhances the circadian rhythm of the biological clock through interactions with the gut microbiota. Sci. Total. Environ. 2023;858 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.160041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.C., Wang Y.G., Li L., Yin H.D., Li D.Y., Wang Y., Zhao X.L., Liu Y.P., Zhu Q. Circadian clock genes are rhythmically expressed in specific segments of the hen oviduct. Poult. Sci. 2016;95:1653–1659. doi: 10.3382/ps/pew051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.