Abstract

Maternal adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) have significant impacts on the next generation with links to negative birth outcomes, impaired cognitive development, and increased socioemotional problems in children. However, not all types or levels of adversity are similarly deleterious and research from diverse contexts is needed to better understand why and how intergenerational transmission of adversity occurs. We examined the role of maternal ACEs on children’s growth, cognitive, and socioemotional development at 36 months postpartum in rural Pakistan. We used data from 877 mother-child dyads in the Bachpan Cohort, a birth cohort study. Maternal ACEs were captured using an adapted version of the ACE-International Questionnaire. Outcomes at 36 months of age included child growth using the WHO growth z-scores, fine motor and receptive language development assessed with the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development, and socioemotional and behavioral development measured with the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Socioemotional and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. To estimate the associations between maternal ACEs and child outcomes, we used multivariable generalized linear models with inverse probability weights to account for sampling and loss to follow-up. Over half of mothers in our sample (58%) experienced at least one ACE. Emotional abuse, physical abuse, and emotional neglect were the most commonly reported ACEs. We found null relationships between the number of maternal ACEs and child growth. Maternal ACEs were associated with higher fine motor and receptive language development and worse socioemotional and behavioral outcomes. Maternal ACE domains had similarly varying relationships with child outcomes. Our findings highlight the complexity of intergenerational associations between maternal ACEs and children’s growth and development. Further work is necessary to examine these relationships across cultural contexts and identify moderating factors to mitigate potential negative intergenerational effects.

Introduction

Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) refer to severely stressful exposures or experiences that occur in childhood, such as abuse, neglect, violence between caregivers, and peer or community violence [1]. The effects of ACEs start early in life and continue throughout the lifecourse, beginning with delayed child development and progressing to poor psychological and physical health outcomes in adulthood [2,3]. ACEs have been linked to numerous adult health outcomes such as cardiometabolic disease, cancer, mortality [4–6], and several negative psychological outcomes including depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety, and suicide [7–10]. Severe early life stressors can lead to observable changes in brain structure and function, which has potentially permanent effects on development [11,12], and can alter physiological systems, such as the stress response axes, immune functioning, and inflammation [13].

While there is considerable evidence of the harmful impact of accumulated ACEs across an individual’s life course, intergenerational effects are an understudied area of concern. The intergenerational transmission of maternal childhood adversity may occur through biological embedding during pregnancy as well as through maternal mental health and parenting-related pathways [13,14]. For example, stress-induced epigenetic alterations during a mother’s childhood can alter the maternal-placental-fetal endocrine, immune, and inflammatory stress biology. Such alterations may lead to biological changes across multiple systems and ultimately affect children’s physical, cognitive, and socioemotional development [15]. A recent study identified a link between maternal ACEs and newborn brain development, which was subsequently associated with negative infant emotionality [16]. Maternal ACEs may also impact the quality of the postnatal environment [14] and, indeed, maternal anxiety, depression, and parenting practices are key mediators between maternal ACEs and child socioemotional development [17–20].

In relation to parental ACEs and early childhood development, the most studied domain is socioemotional development. Worse socioemotional functioning, evident through greater externalizing and internalizing problems, has been shown to exist for children born to mothers with greater exposure to ACEs in high-income countries [17,21–23]. These socioemotional problems include higher anxiety, aggression, hyperactivity, and negative affect in the first three years of life [9,24,25].

Less research has been conducted examining the impact of maternal childhood adversity and the next generation’s physical growth and cognitive development. Examination of the relationship with children’s physical growth is important because linear growth in early childhood is linked to later cognitive and socioemotional development [26,27]. Of the existing research on intergenerational effects, maternal ACEs have been linked to low birth weight and shorter gestational age [28], lower overall development at 12 months [29], lower parental-rated physical health at 18 months [30], and decreased problem solving, gross motor, fine motor, and communication skills at 24 months [31]. All of these studies were conducted in the United States (US) or Canada, and few studies have examined the intergenerational effects of maternal ACE exposure in low- and middle- income countries (LMICs). Addressing ACEs in LMICs is critically important for several reasons: adversity in childhood is more prevalent in LMICs, resources to address ACEs in LMICs are limited, and the majority of the world’s population resides in LMICs [32]. Finally, understanding the intergenerational effects of maternal ACEs across cultural contexts will help to identify vulnerable populations for intervention.

To our knowledge, we are only aware of three studies assessing the intergenerational effects of maternal ACEs in LMICs. In one recent study, researchers reported that maternal ACEs were associated with poor fetal attachment during pregnancy across eight LMICs; however, the effects varied across cultural contexts [33]. Researchers reported positive effect estimates of maternal ACEs on fetal attachment in Jamaica, Pakistan, Philippines, and South Africa, no effect in Sri Lanka, and negative effect estimates in Ghana, Romania, and Vietnam. Two other studies found maternal ACEs were associated with worse socioemotional development among older children (aged 2–18 years) in Kenya [19,20]. The heterogeneity of results from these studies underscore the importance of studying the intergenerational effects of maternal childhood adversity across diverse contexts. These studies also did not investigate how maternal ACEs affected early child growth and development.

The present study examined the role of maternal ACEs in child growth and development at 36 months postpartum in rural Pakistan. Using data on 877 mother-child dyads from a birth cohort, we hypothesized children of mothers with greater exposure to ACEs would experience poorer growth, cognitive development, and worse socioemotional and behavioral outcomes.

Methods

Study population and participants

We used data from the Bachpan Cohort, a birth cohort study based in Kallar Syedan, a rural subdistrict in Rawalpindi, Punjab Province [34,35]. Kallar Syedan has a population of roughly 200,000 people and the average household size is six individuals [36]. Literacy rates for men and women in rural Punjab province are 70% and 53%, respectively. Women in our sample had higher educational attainment compared to the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) rates in rural areas of the Punjab province (50% in our sample achieved secondary school or higher vs. 20% in the DHS) [37].

The Bachpan Cohort is a longitudinal study with an embedded perinatal depression intervention trial. Details on the cohort can be found elsewhere [34,35,38,39]. From 2014–2016, all pregnant women in their third trimester in 40 village clusters were screened for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) [40]. Women who screened positive for depression (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) were invited to participate in the trial and randomized to control or intervention arms. A random sample of women who screened negative for depression (PHQ-9 < 10) were asked to participate in the cohort only portion, which created a population-representative sample. Mother-child dyads were enrolled in their third trimester and followed up at 3, 6, 12, 24, and 36 months postpartum. Participants were allowed to return to the study if the mother and child were still alive and living in the study area. Of the 1,154 women assessed at baseline, 265 were lost to follow-up by 36 months and 12 were missing outcome measurements, resulting in 877 mother-child dyads with complete data.

Exposure

We measured maternal ACEs using an adapted version of the ACE-International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) [41], a self-reported retrospective measure that has been validated in other low-resource contexts (S1 Table) [42,43]. The ACE-IQ was adapted from the original ACE measure developed in the US [44] to include items on peer violence, exposure to collective violence, and witnessing community violence. Due to potential risks to the participant and expected underreporting, we removed the sexual abuse questions. At 36 months postpartum, mothers retrospectively reported their experiences of 12 adverse exposures in childhood.

We operationalized maternal ACEs in multiple ways. We created a continuous score ranging from 0–12. We also generated a categorical variable with the number of experiences (one, two, three, and four or more). Additionally, we created domain-specific indicators for neglect (emotional and physical), household psychological distress (alcohol and/or drug abuser in the household; incarcerated household member; someone depressed, mentally ill, institutionalized or suicidal), home violence (physical abuse; emotional abuse; household member treated violently), and community violence (bullying; community violence; collective violence). For each domain-specific indicator, women received a “Yes” if they experienced any of the ACEs within each domain. Twenty women responded “Do not remember” to some ACE questions and these were recoded as “No” after sensitivity analyses coding these cases as missing did not qualitatively change the results.

Outcomes

Our main outcomes were child growth, fine motor skills, receptive language development, and socioemotional and behavioral outcomes at 36 months. We used the World Health Organization’s international standards to measure physical growth z-scores using length-for-age (LAZ), weight-for-age (WAZ), and weight-for-length (WLZ) [45]. We measured fine motor and receptive language development using the Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSITD), third edition [46]. Scaled scores were calculated using a reference population in the US by the child’s age group; scores range from 1–19 with a mean of 10 and standard deviation of three. The BSITD has been widely used internationally and validated in similar contexts to our study setting [47,48]. Socioemotional development was captured using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire: Socioemotional (ASQ:SE) [49]. The ASQ:SE is a 30-item parent-reported measure, theoretically ranging from 0–270, with higher scores indicating worse child socioemotional development. Behavioral outcomes were assessed using the parent-reported Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) [50]. The SDQ covers 25 questions in five domains: hyperactivity, emotional, conduct, and peer problems, and pro-social behaviors. A total score is calculated by summing the first four domains and theoretically ranges from 0–40, with higher scores indicating worse behavioral outcomes. The ASQ:SE and SDQ are commonly used in LMICs and have been found to be reliable and valid across cultural settings [51,52].

Confounders

We included the following baseline confounders informed by a directed acyclic graph (DAG) [53,54] to estimate the total effect of maternal ACEs on early child growth and development: maternal age, education, and family history of mental illness. We aimed to estimate the total effect of maternal ACEs on child outcomes; therefore, we did not control for potential variables, such as maternal depression or child health, which we identified as mediators using the DAG (S1 Fig). We used maternal education as a proxy for maternal childhood socioeconomic status and operationalized it as a categorical variable (none, primary or middle school, secondary education or higher). We asked mothers to report if anyone in her immediate natal family had an existing mental illness and used it as a proxy for the mother’s family history of mental illness.

Statistical analysis

We constructed multivariable generalized linear models to assess the relationship between maternal ACEs and child growth and development. In addition to confounders, we also included child gender, trial arm, and assessor as auxiliary variables in all models to improve precision [55]. We used cluster robust standard errors to account for clustering by village, and cluster-specific sampling weights to account for unequal sampling probabilities by baseline depression. In a given cluster, all non-depressed women were weighted by the inverse of their sampling fraction (i.e., the proportion that were screened for depression at recruitment and subsequently enrolled), and depressed women were each given a weight of 1. Therefore, non-depressed women were upweighted to account for their lower probability of selection into the study.

To account for informative censoring between baseline and 36 months postpartum, we used stabilized inverse probability of censoring weights (IPCW) [56]. IPCW are estimated as the inverse of the probability that a woman was not censored at 36 months, based on observed characteristics. Women who were not loss to follow-up were upweighted to represent those who were lost to follow-up. In the IPCW model, we included baseline confounders (maternal age, education, and family history of mental illness) and baseline characteristics associated with censoring using a p-value <0.10 (maternal depression, child’s grandmother co-residence, number of people per room, and nuclear vs. joint family), with household asset scores included to increase precision [57]. IPCW were stabilized by using the marginal probability of being observed in the numerator. Sampling weights and IPCW were multiplied to create a final weight used in all models [58]. The final weight was also used to estimate means and frequencies in descriptive tables; numbers were unweighted. Analyses were conducted in Stata 14 and R (4.1.0).

Ethics approval

The Bachpan Cohort study received ethical approval from the institutional review boards at the Human Development Research Foundation (IRB/1017/2021), Duke University, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (#20–1433). Written informed consent, or witnessed informed consent if the participant was illiterate, was obtained before study participation.

Results

Descriptive statistics

There were 877 women and children in our analytic sample (Table 1). After applying weights, on average, women were 27 years old and half had completed secondary school education or higher at baseline. Roughly 28% of mothers were diagnosed with depression at baseline and 9% reported having a family history of mental illness. The majority of households were joint or extended families and 68% of children were co-residing with a grandmother. Almost half of the children were female and mean LAZ and WAZ were -0.99 (SD = 1.10) and -0.96 (SD = 0.99), respectively. Mean fine motor and receptive language scaled scores were slightly higher than the average of 10 (10.43 [2.79]; 11.45 [4.03], respectively). Mean ASQ-SE and SDQ scores were 38.83 (SD = 17.03) and 14.02 (SD = 6.30), respectively.

Table 1. Sample characteristics, Bachpan Cohort, Pakistan, n = 877.

| Mean or N | SD or % | Range | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal characteristics (baseline) | ||||

| Maternal age | 26.60 | 4.29 | 18–45 | |

| Maternal education | ||||

| None | 124 | 13.60 | ||

| Primary or middle school | 338 | 36.27 | ||

| Secondary school or higher | 413 | 50.14 | ||

| Natal family history of mental illness | 95 | 8.93 | ||

| Depression diagnosis (SCID) | 314 | 27.56 | ||

| Household characteristics (baseline) | ||||

| People per room | 2.37 | 1.87 | 0–23 | |

| Nuclear family (vs. joint or extended) | 111 | 13.16 | ||

| Grandmother coresidence | 609 | 68.29 | ||

| Trial arm: Intervention (vs. control) | 426 | 51.68 | ||

| Household assets* | ||||

| Lowest | 165 | 17.58 | ||

| Lower middle | 176 | 18.37 | ||

| Middle | 184 | 19.68 | ||

| Upper middle | 173 | 21.99 | ||

| Highest | 177 | 22.38 | ||

| Child characteristics (36 months) | ||||

| Age (months) | 36.3 | 0.60 | ||

| Gender: Female | 432 | 48.37 | ||

| Length-for-age z-score | -0.99 | 1.10 | -4.59–2.87 | |

| Weight-for-age z-score | -0.96 | 0.99 | -4.64–4.23 | |

| Weight-for-height z-score | -0.61 | 1.12 | -5.08–5.65 | |

| BSITD receptive language scaled score | 10.43 | 2.79 | 5–19 | |

| BSITD fine motor scaled score | 11.45 | 4.03 | 2–19 | |

| ASQ-SE total score | 38.83 | 17.03 | 10–170 | |

| SDQ total difficulties score | 14.02 | 6.30 | 3–34 | |

* Sampling probability and inverse probability weights were used to calculate means, SDs, and percentages.

Abbreviations: Bayley Scales of Infant and Toddler Development (BSITD); Ages and Stages Questionnaire-Socioemotional (ASQ-SE); Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)

* Principal components analysis was used to create an asset index and then operationalized as quintiles.

After applying weights, over 58% of women (n = 512) experienced at least one ACE (Table 2). Among the 12 ACE questions, emotional abuse (n = 290, 32%), physical abuse (n = 206, 23%), emotional neglect (n = 131, 15%), and witnessing a household member being treated violently (n = 128, 15%) were the most common. With respect to ACE domains, more than one in three women were exposed to violence in their childhood home (n = 344, 39%) and one in five experienced emotional or physical neglect during their childhood (n = 170, 19%). Roughly 16% (n = 141) experienced family psychological distress. Community violence was far less common (n = 63, 6.9%).

Table 2. Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences (n = 877)*.

| N | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of ACEs | |||

| None | 363 | 41.49 | |

| 1 | 235 | 26.86 | |

| 2 | 137 | 15.66 | |

| 3 | 81 | 9.26 | |

| 4 or more | 59 | 6.74 | |

| Neglect | |||

| Physical neglect | 49 | 5.60 | |

| Emotional neglect | 131 | 14.97 | |

| Family psychological distress | |||

| One or no parents, parental separation or divorce | 96 | 10.97 | |

| Alcohol/drug abuser in the household | 23 | 2.63 | |

| Someone chronically depressed, mentally ill | 21 | 2.40 | |

| Incarcerated household member | 16 | 1.83 | |

| Home violence | |||

| Household member treated violently | 128 | 14.63 | |

| Physical abuse | 206 | 23.54 | |

| Emotional abuse | 290 | 33.14 | |

| Community violence | |||

| Bullying | 12 | 1.37 | |

| Community violence | 59 | 6.74 | |

| Collective violence | 4 | 0.46 | |

| ACE domains ** | |||

| Neglect | 170 | 19.43 | |

| Family psychological distress | 141 | 16.11 | |

| Home violence | 344 | 39.31 | |

| Community violence | 63 | 7.20 | |

| Mean | SD | ||

| Total number of ACEs (range: 0–10) | 2.37 | 1.38 | |

* Sampling probability weights and inverse probability weights were used.

** Domains were binary categories describing experience of any individual ACEs.

We highlight the effects of maternal ACEs on child growth and development below. Full estimates and precision are presented in S2 and S3 Tables.

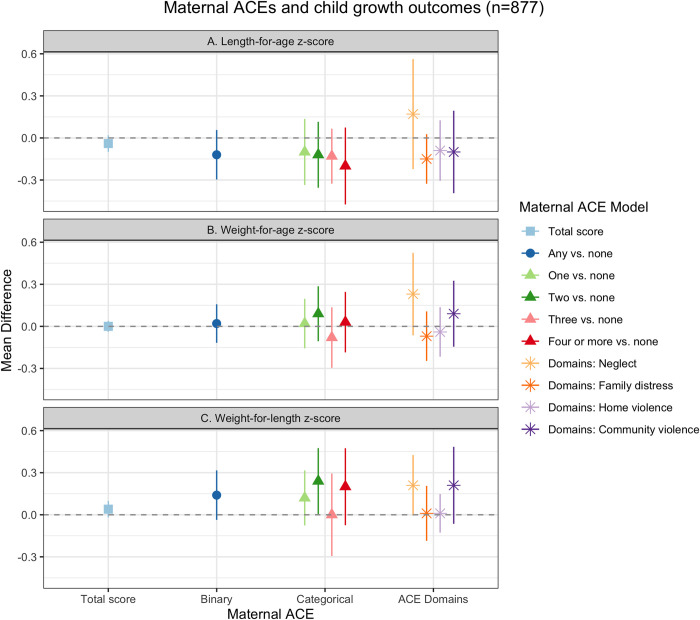

Growth outcomes

We found cross-sectional associations between maternal ACEs and child growth z-scores (Fig 1, S2 Table). There were small, negative relationships between maternal ACEs and child LAZ (Fig 1A). We found a small, negative stepwise trend between categorical maternal ACEs and child LAZ. Compared to no maternal ACEs, the mean difference of having an additional maternal ACE on child LAZ became stronger as the number of ACEs increased, with one maternal ACE associated with a 0.10 standard deviation (SD) decrease in child LAZ (95% CI: -0.34, 0.14) and four or more maternal ACEs associated with a 0.20 SD decrease in child LAZ (95% CI: -0.48, 0.09). Maternal childhood exposure to neglect was associated with a 0.17 SD increase in child LAZ (95% CI: -0.23, 0.56), controlling for other ACE domains. Family distress and community violence had small, negative associations with child LAZ (Fig 1A) (Family distress: MD = -0.15 (95% CI: -0.32, 0.03); Community violence: MD = -0.10 (95% CI: -0.40, 0.21).

Fig 1. Maternal ACEs and child growth, Bachpan Cohort, Pakistan (n = 877).

We used weighted generalized linear models with cluster robust standard errors. Sampling and inverse probability censoring weights were combined. All models controlled for baseline maternal age, maternal education, trial arm, assessor, and child gender.

We found largely null relationships between maternal ACEs and child WAZ (Fig 1B); however, neglect was associated with a 0.23 SD increase in WAZ, controlling for other ACE domains (95% CI: -0.07, 0.53). Maternal ACEs and child WLZ had small positive associations (Fig 1C). Any maternal ACE compared to none was associated with a 0.14 SD increase in WLZ (95% CI: -0.03, 0.31). There was no clear stepwise trend between categorical maternal ACEs and WLZ; however, four or more maternal ACEs were associated with a 0.20 SD higher WLZ (95% CI: -0.08, 0.48). Maternal childhood exposure to neglect and community violence were also each associated with a 0.21 increase in child WLZ (95% CI: -0.02, 0.44; 95% CI: -0.07, 0.50, respectively).

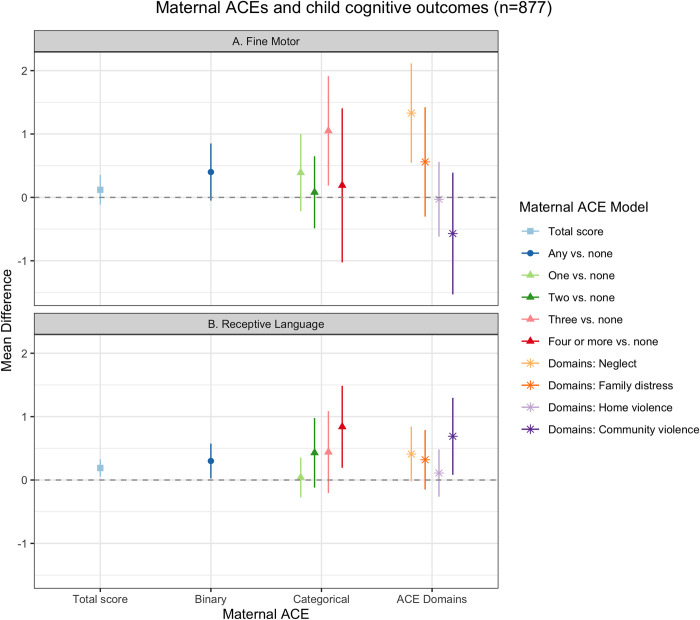

Fine motor and receptive language outcomes

We found positive associations between maternal ACEs and children’s fine motor and receptive language scores (Fig 2, S3 Table). Any maternal experience of ACEs was associated with a 0.40-point increase in child fine motor scores (95% CI: -0.07, 0.87) compared to no maternal ACE. There was no clear stepwise trend in categorical maternal ACE exposure and fine motor scores (Fig 2A); however, we found small positive associations between mothers experiencing one ACE (versus none) and three ACEs (versus none) and child fine motor scores (One maternal ACE: MD = 0.39 (95% CI: -0.22, 1.01); Three maternal ACEs: MD = 1.05 (95% CI: 0.15, 1.94)). Maternal childhood experiences of neglect and family distress were associated with higher child fine motor scores (Neglect: MD = 1.33 (95% CI: 0.52, 2.14); Family distress: MD = 0.56 (95% CI: -0.32, 1.44)) (Fig 2A). Community violence was associated with lower fine motor scores (MD = -0.57 (95% CI: -1.56, 0.42).

Fig 2. Maternal ACEs and child fine motor and receptive language development, Bachpan Cohort, Pakistan (n = 877).

We used weighted generalized linear models with cluster robust standard errors. Sampling and inverse probability censoring weights were combined. All models controlled for baseline maternal age, maternal education, trial arm, assessor, and child gender.

Similar to the fine motor results, we found positive associations between maternal ACE and child receptive language skills. Any maternal ACE was associated with a 0.30-point increase in receptive language scores (95% CI: 0.02, 0.59), compared to no maternal ACE. We saw a small stepwise trend between categorical maternal ACEs and child receptive language scores; there was no association with one maternal ACE, but an increasingly small positive association with two, three, and four or more ACEs, with four or more maternal ACEs associated with a 0.84-point increase in scores (95% CI: 0.16, 1.51) (Fig 2B). Controlling for the other ACE domains, we found positive, but small independent associations between neglect, family distress, and home violence and receptive language scores (Neglect: MD = 0.41 (95% CI: -0.04, 0.86); Family distress: MD = 0.32 (95% CI: -0.17, 0.82); Community violence: MD = -0.73 (95% CI: 0.09, 1.38)) (Fig 2B). Home violence was not associated with children’s fine motor or receptive language scores.

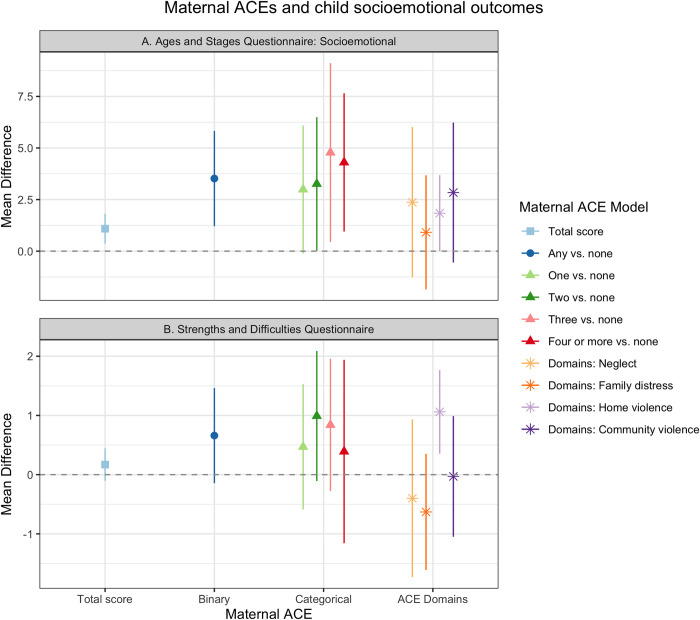

Socioemotional outcomes

We found that maternal ACEs were associated with higher ASQ:SE and SDQ scores for children, which suggests worse child socioemotional and behavioral development (Fig 3, S3 Table). Compared to children of mothers who experienced no ACE, children whose mothers experienced any ACE scored 3.52 points higher on the ASQ:SE (Fig 3A, 95% CI: 1.14, 5.90). Categorical maternal ACEs (one, two, three, and four or more) were associated with increasingly higher ASQ:SE scores compared to no maternal ACE (Fig 3A). One maternal ACE exposure was associated with a 2.99-point increase in ASQ:SE (95% CI: -0.21, 6.18) and four or more ACEs associated with a 4.30-point increase (95% CI: 0.84, 7.75). Maternal experience of all four domains (neglect, family distress, home violence, and community violence) were associated with roughly 1–3 points higher ASQ:SE scores (Fig 3A); however, our estimates were imprecise as indicated by the wide confidence intervals with confidence limit differences ranging from 3.79 to 7.53.

Fig 3. Maternal ACEs and child socioemotional and behavioral outcomes, Bachpan Cohort, Pakistan (n = 877).

We used weighted generalized linear models with cluster robust standard errors. Sampling and inverse probability censoring weights were combined. All models controlled for baseline maternal age, maternal education, trial arm, assessor, and child gender.

We found a similar effect of maternal ACEs on SDQ; however, the results were attenuated compared to ASQ:SE. Any maternal ACE was associated with a 0.66-point increase in SDQ scores compared to no ACE (Fig 3B, 95% CI: -0.17, 1.50). We found a small increasing pattern between categorical maternal ACEs and SDQ scores (Fig 3B). Maternal childhood experience of home violence was associated with 1.06-point increase in children’s SDQ scores (Fig 3B, (95% CI: 0.32, 1.80), while neglect and family distress had small negative associations with child SDQ scores (Neglect: MD = -0.40 (95% CI: -1.77, 0.97); Family distress: MD = -0.63 (95% CI: -1.64, 0.39)).

Discussion

The goal of our study was to estimate the relationships between maternal ACEs and child development at 36 months of age. Over half of the mothers in our sample in rural Pakistan experienced at least one ACE. Maternal ACEs were not strongly associated with child growth z-scores. We found an unexpected relationship between maternal ACEs and child fine motor and receptive language development, where maternal childhood experience of adversity was associated with more positive child development. Maternal ACEs were associated with worse child socioemotional and behavioral outcomes.

Mothers most commonly reported experiences of emotional abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect, or seeing a household member treated violently during their childhood. The prevalence of any maternal ACEs in our sample (58%) was lower than in other LMICs using the same measure (ACE-IQ, roughly 80% in Saudi Arabia, Vietnam, Tunisia, and Lebanon) [59]. Other studies in Pakistan have also reported lower levels of ACEs. For example, one study of Pakistani university students found the mean number of ACEs among women was 0.40 (SD = 0.92) [60], compared with our mean of 2.37 (SD = 1.38). The authors of that study emphasized that in a collectivist and conservative context like Pakistan, the role of the family is critical even throughout adulthood, making it especially difficult to disclose sensitive topics, such as child maltreatment and family distress. Another study of pregnant women in Pakistan reported a similar mean number of maternal ACEs in Pakistan (3.07, SD = 2.37) as our study (2.37, SD = 1.38) [33]. This study also found a wide range of mean ACEs across eight LMICs (from 2.54 in Vietnam to 6.42 in South Africa) [33], thus underscoring the importance of examining diverse cultural and contextual factors when assessing ACEs. Specific to measurement, another reason for the low prevalence of ACEs in our study may be due to our exclusion of the sexual abuse questions, given potential risks to participants and expected underreporting of disclosure. Cross-country variation in the mean number of reported ACEs may therefore be due to both differential reporting and true variation in ACE exposures.

In our study, maternal ACEs were not strongly associated with child growth outcomes at 36 months. If a key mechanism through which maternal ACEs influence growth is through the intrauterine environment in pregnancy [13,14], it is possible that any such effects would be observed closer to birth. The potential negative effects of maternal ACEs on children’s physical development could have also been remedied through moderating factors, such as improved nutrition and catch-up growth [61]. During the first three years of life, other external factors might also have stronger influences on child growth. In low-resource contexts, other forms of early life adversity not captured by ACEs, such as extreme poverty, may have a greater effect on children’s physical development than maternal ACEs [62]. Future studies examining these potential mediators between maternal ACEs and child growth would help identify possible intergenerational pathways.

Notably, maternal ACEs were associated with higher children’s fine motor and receptive language scores. There is limited literature examining the intergenerational transmission of maternal ACEs on children’s overall developmental outcomes. Existing research from high-income countries are mixed. In two studies from the US and Canada, maternal ACEs were associated with worse overall development and greater risk of developmental delay [29,31], while another US study found no relationship between maternal ACEs and child development [63]. We found no prior study investigating maternal ACEs and overall child development in LMICs. While more research is needed to replicate these findings, life history evolution theory may help to explain the positive relationship between maternal ACEs and better child development. Life history theory suggests that individuals who are exposed to harsh or unpredictable environments (e.g. poverty, exposure to violence, harsh parenting) develop faster life history strategies in order to adapt and survive in such stressful environments [64,65]. Existing evidence demonstrates that parents with ACEs were less emotionally available and engaged in harsh discipline with their children [66]. While outside the scope of this study, future studies should examine the relationship between maternal ACEs and parenting behaviors, such as maternal responsivity and quality of the home environment.

Related, post-traumatic growth may also help explain a positive relationship between maternal ACEs and better child development. Post-traumatic growth is defined as a positive psychological change following traumatic events [67–69]. Prior work has found that individuals who experience past adversity have increased empathy and altruism for others [70–72]. In support of this hypothesis, Brown et al (2021) found a positive effect of maternal ACEs on fetal attachment among Pakistani mothers, although they did not examine child development. Importantly, the exact mechanisms through which this would be linked to improved developmental outcomes remains unknown. Assessing the ways in which post-traumatic growth among mothers who experienced ACEs affects health and social behaviors across the lifecourse would be invaluable.

In contrast to the findings with overall development, maternal ACEs were associated with worse child socioemotional development and behavioral outcomes in our sample. This finding is consistent with the existing literature. In a systematic review, authors found maternal ACEs were associated with child externalizing behavior problems and the majority of included studies found relationships with child internalizing problems [73]. Similar results have been found in Kenya among older aged children (2–18 years) [19,20]. These links can potentially be explained through both biological and psychological pathways. Potential biological mechanisms suggest maternal experience of childhood adversity may influence maternal HPA-axis functioning during pregnancy, leading to changes in the gestational environment and the development of fetal stress response systems [74,75]. The hormonal changes during pregnancy may, in turn, influence the woman’s mental health and health behaviors [76,77], which can then affect infant stress regulation and behavioral difficulties [78]. Psychosocial mechanisms posit that maternal ACEs can lead to poor attachment and development of healthy relationships between mothers and children [73]. Mothers who experience childhood trauma may be predisposed to mental health conditions such as anxiety or depression, and poor maternal mental health has been linked to increased parenting stress, impaired mother-child interactions, and harsher maternal parenting practices [79]. Furthermore, in the context of LMICs, economic and parenting resources may be scarce, which can exacerbate stress in the home environment. This, in turn, may lead to suboptimal caregiving (lack of warmth and responsiveness) and ultimately, worse child socioemotional development and behavior outcomes.

Finally, maternal ACE domains (Neglect, Family distress, Home violence, and Community violence) had varying relationships with child development. Maternal childhood exposure to neglect was associated with better child growth, fine motor, and receptive language development, but worse child socioemotional development. Maternal childhood experience of family distress, home violence, and community violence had varied relationships with child outcomes. It is important to note that deprivation (absence of cognitive and social inputs) and threat (presence of threatening experiences) likely have distinct influences on neural development [80], and research has shown differential impacts on cognitive and emotional outcomes in children as well as pregnant women [81–83]. As previously mentioned, post-traumatic growth and compensatory parenting practices may help to explain the positive relationships of past maternal neglect on her own child’s outcomes [67,68,84]. Positive experiences, such as supportive relationships and prosocial activities, can help to mitigate the impact of ACEs by serving as a promotive resilience factor [84]. Prior research demonstrates that adults who had positive childhood experiences are more likely to have resilient functioning and more compensatory behaviors (e.g. less harsh parenting attitudes, greater affection) even if they experienced ACEs [85–89]. Mothers who experienced neglect in their childhood and had positive experiences concurrently or later in childhood may develop resiliency and in turn provide more resources and improved parenting for their children. Future research in LMICs should focus on identifying differential impacts of ACE domains on the next generation and examine whether and how positive experiences can mitigate the intergenerational transmission.

Although such explorations are beyond the scope of the current paper, important factors, such as maternal depression and parenting practices, may mediate the relationship between maternal ACEs and child outcomes. Previous work from our group demonstrated that ACEs were associated with greater depressive symptoms and major depressive episodes [90]. Studies in Kenya found that maternal mental health mediated the relationship between maternal ACEs and child mental health problems [19,20]. A study among pregnant mothers across eight LMICs found prenatal depression fully mediated the effect of maternal ACEs on fetal attachment using the full sample [33]. However, at the country-level, direct effects varied; in Vietnam, maternal ACEs directly and negatively affected fetal attachment and maternal prenatal depression did not mediate the relationship [33]. Other caregivers, such as fathers and grandmothers, are also important to consider. Their contributions may buffer any negative effects of maternal ACEs on children by improving maternal social support.

Strengths and limitations

Our study had several strengths. We used standard, validated measures of child outcomes that have been previously used in our study context. Moreover, we estimated the total effect of maternal ACEs on the next generation’s development as opposed to controlling for potential mediators, such as adult socioeconomic status or depression status, which may lead to biased estimates. Our study also had limitations that require discussion. First, although we used the ACE-IQ to capture maternal ACEs, it is a retrospective measure, which is vulnerable to recall bias. In the context of this study, it may be that depressed women are more likely to report ACEs in order to understand their depressive symptoms, resulting in potential differential misclassification. Moreover, the ACE-IQ may not fully measure adversities during childhood in this context. Second, while we controlled for maternal childhood SES and maternal family history of mental illness, we used proxies (maternal education and natal family mental illness history, respectively), and residual confounding is possible. Third, 265 women and children were lost to follow-up at 36 months postpartum; however, we used stabilized IPCW to account for informative censoring. Finally, there may be unmeasured confounders that affect this relationship, such as how mothers were raised (i.e., the caregiving practices of the mother’s parents).

Conclusion

Our findings suggest the intergenerational transmission of childhood adversity is complex and may differentially influence physical, cognitive, and socioemotional domains of child development. To improve child health and development, it is necessary to understand maternal life histories, including her childhood experiences, rather than only capturing her experiences during pregnancy and postpartum. Future work should examine the intergenerational relationship of childhood adversity across cultural contexts in order to understand specific risk and protective factors and develop tailored interventions. Identifying moderating factors, such as promoting maternal responsive caregiving and improving maternal social support via other caregivers, can help inform strategies to disrupt the intergenerational cycle of adversity that is responsive to traumatic histories.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DTA)

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply grateful to the women, children, and communities of the Bachpan cohort. We would also like to thank the team at the Human Development Research Foundation (HDRF) including Rakshanda Liaqat, Tayyiba Abbasi, Maria Sharif, Samina Bilal, Quratul-Ain, Anum Nisar, Amina Bibi, Shaffaq Zufi- qar, Sonia Khan, Ahmed Zaidi, Ikhlaq Ahmad, and Najia Atif for their meaningful contributions to the study’s design and implementation. We also thank the larger Bachpan and SHARE CHILD study teams. We are grateful for Paul Zivich’s advice and guidance for implementing inverse probability weights.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The larger study was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (U19MH95687), and National Institute of Child Health and Development (R01 HD075875). The Carolina Population Center provided training and general support (P2C-HD050924). EOC and KL received training support from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (T32 HD091058). BSS also received training support from the NIH (T32 HL129982). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cprek SE, Williamson LH, McDaniel H, Brase R, Williams CM. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and Risk of Childhood Delays in Children Ages 1–5. Child Adolesc Soc Work J. 2020;37(1):15–24. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shonkoff JP, Garner AS, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of C, Family H, Committee on Early Childhood A, Dependent C, et al. The lifelong effects of early childhood adversity and toxic stress. Pediatrics. 2012. Jan;129(1):e232–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown DW, Anda RF, Tiemeier H, Felitti VJ, Edwards VJ, Croft JB, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of premature mortality. Am J Prev Med. 2009. Nov;37(5):389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.06.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown MJ, Thacker LR, Cohen SA. Association between adverse childhood experiences and diagnosis of cancer. PloS One. 2013;8(6):e65524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakubowski KP, Cundiff JM, Matthews KA. Cumulative childhood adversity and adult cardiometabolic disease: A meta-analysis. Health Psychol Off J Div Health Psychol Am Psychol Assoc. 2018. Aug;37(8):701–15. doi: 10.1037/hea0000637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atzl VM, Narayan AJ, Rivera LM, Lieberman AF. Adverse childhood experiences and prenatal mental health: Type of ACEs and age of maltreatment onset. J Fam Psychol JFP J Div Fam Psychol Am Psychol Assoc Div 43. 2019. Apr;33(3):304–14. doi: 10.1037/fam0000510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman DP, Whitfield CL, Felitti VJ, Dube SR, Edwards VJ, Anda RF. Adverse childhood experiences and the risk of depressive disorders in adulthood. J Affect Disord. 2004. Oct 15;82(2):217–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Letourneau N, Dewey D, Kaplan BJ, Ntanda H, Novick J, Thomas JC, et al. Intergenerational transmission of adverse childhood experiences via maternal depression and anxiety and moderation by child sex. J Dev Orig Health Dis. 2019. Feb;10(1):88–99. doi: 10.1017/S2040174418000648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pournaghash-Tehrani SS, Zamanian H, Amini-Tehrani M. The Impact of Relational Adverse Childhood Experiences on Suicide Outcomes During Early and Young Adulthood. J Interpers Violence. 2019. May 29;886260519852160. doi: 10.1177/0886260519852160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Juster RP, McEwen BS, Lupien SJ. Allostatic load biomarkers of chronic stress and impact on health and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;35(1):2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central role of the brain in stress and adaptation: links to socioeconomic status, health, and disease. Ann N Acad Sci. 2010;1186:190. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05331.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berens AE, Jensen SKG, Nelson CA. Biological embedding of childhood adversity: from physiological mechanisms to clinical implications. BMC Med. 2017. Jul 20;15(1):135. doi: 10.1186/s12916-017-0895-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buss C, Entringer S, Moog NK, Toepfer P, Fair DA, Simhan HN, et al. Intergenerational Transmission of Maternal Childhood Maltreatment Exposure: Implications for Fetal Brain Development. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017. May;56(5):373–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2017.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nelson CA, Bhutta ZA, Harris NB, Danese A, Samara M. Adversity in childhood is linked to mental and physical health throughout life. BMJ. 2020. Oct 28;371:m3048. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Demers CH, Hankin BL, Hennessey EMP, Haase MH, Bagonis MM, Kim SH, et al. Maternal adverse childhood experiences and infant subcortical brain volume. Neurobiol Stress. 2022. Nov 1;21:100487. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2022.100487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooke JE, Racine N, Plamondon A, Tough S, Madigan S. Maternal adverse childhood experiences, attachment style, and mental health: Pathways of transmission to child behavior problems. Child Abuse Negl. 2019. Jul;93:27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shih EW, Ahmad SI, Bush NR, Roubinov D, Tylavsky F, Graff C, et al. A path model examination: maternal anxiety and parenting mediate the association between maternal adverse childhood experiences and children’s internalizing behaviors. Psychol Med. 2021. May 18;1–11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar M, Amugune B, Madeghe B, Wambua GN, Osok J, Polkonikova-Wamoto A, et al. Mechanisms associated with maternal adverse childhood experiences on offspring’s mental health in Nairobi informal settlements: a mediational model testing approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2018. Dec;18(1):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rieder AD, Roth SL, Musyimi C, Ndetei D, Sassi RB, Mutiso V, et al. Impact of maternal adverse childhood experiences on child socioemotional function in rural Kenya: Mediating role of maternal mental health. Dev Sci. 2019. Sep;22(5):e12833. doi: 10.1111/desc.12833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McDonnell CG, Valentino K. Intergenerational Effects of Childhood Trauma: Evaluating Pathways Among Maternal ACEs, Perinatal Depressive Symptoms, and Infant Outcomes. Child Maltreat. 2016. Nov;21(4):317–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559516659556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hetherington E, McDonal S, Tough S. Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) and child development at 5 years. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;24(Supplement_2):e36–e36. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schickedanz A, Halfon N, Sastry N, Chung PJ. Parents’ adverse childhood experiences and their children’s behavioral health problems. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2):e20180023. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-0023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McDonald SW, Madigan S, Racine N, Benzies K, Tomfohr L, Tough S. Maternal adverse childhood experiences, mental health, and child behaviour at age 3: The all our families community cohort study. Prev Med. 2019. Jan;118:286–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Treat AE, Sheffield-Morris A, Williamson AC, Hays-Grudo J. Adverse childhood experiences and young children’s social and emotional development: the role of maternal depression, self-efficacy, and social support. Early Child Dev Care [Internet]. 2019. Jan 1 [cited 2020 Dec 16]; Available from: https://scholars.okstate.edu/en/publications/adverse-childhood-experiences-and-young-childrens-social-and-emot [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sudfeld CR, Charles McCoy D, Danaei G, Fink G, Ezzati M, Andrews KG, et al. Linear Growth and Child Development in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Meta-Analysis. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):e1266. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prado EL, Larson LM, Cox K, Bettencourt K, Kubes JN, Shankar AH. Do effects of early life interventions on linear growth correspond to effects on neurobehavioural development? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2019. Oct 1;7(10):e1398–413. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30361-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith MV, Gotman N, Yonkers KA. Early Childhood Adversity and Pregnancy Outcomes. Matern Child Health J. 2016. Apr;20(4):790–8. doi: 10.1007/s10995-015-1909-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Racine N, Plamondon A, Madigan S, McDonald S, Tough S. Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Infant Development. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172495. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madigan S, Wade M, Plamondon A, Maguire JL, Jenkins JM. Maternal Adverse Childhood Experience and Infant Health: Biomedical and Psychosocial Risks as Intermediary Mechanisms. J Pediatr. 2017. Aug;187:282–289.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Folger AT, Eismann EA, Stephenson NB, Shapiro RA, Macaluso M, Brownrigg ME, et al. Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences and Offspring Development at 2 Years of Age. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20172826. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2826 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mikton C, Butchart A. Current state of the global public health response to child maltreatment and intimate partner violence. In 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brown RH, Eisner M, Walker S, Tomlinson M, Fearon P, Dunne MP, et al. The impact of maternal adverse childhood experiences and prenatal depressive symptoms on foetal attachment: Preliminary evidence from expectant mothers across eight middle-income countries. J Affect Disord. 2021. Dec 1;295:612–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner EL, Sikander S, Bangash O, Zaidi A, Bates L, Gallis J, et al. The effectiveness of the peer-delivered Thinking Healthy PLUS (THPP+) Program for maternal depression and child socioemotional development in Pakistan: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2016. Sep 8;17(1):442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maselko J, Sikander S, Turner E, Bates L, Ahmad I, Atif N, et al. Effectiveness of a peer-delivered, psychosocial intervention on maternal depression and child development at 3 years postnatal: a cluster randomised trial in Pakistan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020. Sep 1;7:775–87. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30258-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Government of Pakistan. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Census. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 37.National Institute of Population Studies, ICF. Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017–18 [Internet]. Islamabad, Pakistan: NIPS/Pakistan and ICF; 2019. Available from: http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR354/FR354.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sikander S, Ahmad I, Bates LM, Gallis J, Hagaman A, O’Donnell K, et al. Cohort Profile: Perinatal depression and child socioemotional development; the Bachpan cohort study from rural Pakistan. BMJ Open. 2019;9(5):e025644. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sikander S, Ahmad I, Atif N, Zaidi A, Vanobberghen F, Weiss HA, et al. Delivering the Thinking Healthy Programme for perinatal depression through volunteer peers: a cluster randomised controlled trial in Pakistan. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019. Feb;6(2):128–39. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30467-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gallis JA, Maselko J, O’Donnell K, Song K, Saqib K, Turner EL, et al. Criterion-related validity and reliability of the Urdu version of the patient health questionnaire in a sample of community-based pregnant women in Pakistan. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5185. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.World Health Organization. Adverse Childhood Experiences International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) [Internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/activities/adverse_childhood_experiences/en/. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kidman R, Smith D, Piccolo LR, Kohler HP. Psychometric evaluation of the Adverse Childhood Experience International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) in Malawian adolescents. Child Abuse Negl. 2019. Jun;92:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.03.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kazeem OT. A Validation of the Adverse Childhood Experiences Scale in Nigeria. Sex Abuse. 2015;7. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, et al. Relationship of Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction to Many of the Leading Causes of Death in Adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998. May 1;14(4):245–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. WHO Child Growth Standards based on length/height, weight and age. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2006. Apr;450:76–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2006.tb02378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bayley N. Bayley Scales of Infant Development-III. Psychological Corporation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pendergast LL, Schaefer BA, Murray-Kolb LE, Svensen E, Shrestha R, Rasheed MA, et al. Assessing development across cultures: Invariance of the Bayley-III Scales Across Seven International MAL-ED sites. Sch Psychol Q. 2018. Dec;33(4):604–14. doi: 10.1037/spq0000264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ranjitkar S, Kvestad I, Strand TA, Ulak M, Shrestha M, Chandyo RK, et al. Acceptability and reliability of the bayley scales of infant and toddler development-III among children in Bhaktapur, Nepal. Front Psychol. 2018;9:1265. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Squires J, Bricker D. Ages & stages questionnaires, (ASQ-3). Parent-Complet Child Monit Syst 3rd Ed Baltim MD Brookes. 2009; [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: a research note. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1997. Jul;38(5):581–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Velikonja T, Edbrooke-Childs J, Calderon A, Sleed M, Brown A, Deighton J. The psychometric properties of the Ages & Stages Questionnaires for ages 2–2.5: a systematic review. Child Care Health Dev. 2017. Jan;43(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Samad L, Hollis C, Prince M, Goodman R. Child and adolescent psychopathology in a developing country: testing the validity of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (Urdu version). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2005;14(3):158–66. doi: 10.1002/mpr.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glymour MM, Greenland S. Causal diagrams. In: Modern Epidemiology. Third. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shrier I, Platt RW. Reducing bias through directed acyclic graphs. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW. Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiol Camb Mass. 2009. Jul;20(4):488–95. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013. Jun;22(3):278–95. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brookhart MA, Schneeweiss S, Rothman KJ, Glynn RJ, Avorn J, Sturmer T. Variable selection for propensity score models. Am J Epidemiol. 2006. Jun 15;163(12):1149–56. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dugoff EH, Schuler M, Stuart EA. Generalizing observational study results: applying propensity score methods to complex surveys. Health Serv Res. 2014. Feb;49(1):284–303. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Solberg MA, Peters RM. Adverse Childhood Experiences in Non-Westernized Nations: Implications for Immigrant and Refugee Health. J Immigr Minor Health. 2020. Feb;22(1):145–55. doi: 10.1007/s10903-019-00953-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bokhari M, Badar M, Naseer U, Waheed A, Safdar F. Adverse Childhood Experiences & Impulsivity in Late Adolescence & Young Adulthood of Students of University of the Punjab Lahore. 2015;14. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pradeilles R, Norris T, Ferguson E, Gazdar H, Mazhar S, Bux Mallah H, et al. Factors associated with catch-up growth in early infancy in rural Pakistan: A longitudinal analysis of the women’s work and nutrition study. Matern Child Nutr. 2019;15(2):e12733. doi: 10.1111/mcn.12733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Engle PL, Black MM. The effect of poverty on child development and educational outcomes. Ann N Acad Sci. 2008;1136:243–56. doi: 10.1196/annals.1425.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown AL, McKenna BG, Cohen MF, Dunlop AL, Corwin EJ, Brennan PA. Maternal childhood adversity and early parenting: Implications for infant neurodevelopment. Int Public Health J. 2018;10(4):445–54. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bjorklund DF, Ellis BJ. Children, childhood, and development in evolutionary perspective. Dev Rev. 2014. Sep 1;34(3):225–64. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quinlan RJ. Human parental effort and environmental risk. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2007. Jan 7;274(1606):121–5. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rowell T, Neal-Barnett A. A Systematic Review of the Effect of Parental Adverse Childhood Experiences on Parenting and Child Psychopathology. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2022. Mar 1;15(1):167–80. doi: 10.1007/s40653-021-00400-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tedeschi RG, Park CL, Calhoun LG. Posttraumatic growth: Positive changes in the aftermath of crisis. Routledge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tranter H, Brooks M, Khan R. Emotional resilience and event centrality mediate posttraumatic growth following adverse childhood experiences. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2021;13(2):165–73. doi: 10.1037/tra0000953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Greenberg DM, Baron-Cohen S, Rosenberg N, Fonagy P, Rentfrow PJ. Elevated empathy in adults following childhood trauma. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0203886. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Staub E, Vollhardt J. Altruism born of suffering: The roots of caring and helping after victimization and other trauma. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(3):267–80. doi: 10.1037/a0014223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vollhardt JR. Altruism Born of Suffering and Prosocial Behavior Following Adverse Life Events: A Review and Conceptualization. Soc Justice Res. 2009. Mar 1;22(1):53–97. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lim D, DeSteno D. Suffering and compassion: The links among adverse life experiences, empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. Emotion. 2016;16(2):175–82. doi: 10.1037/emo0000144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Cooke JE, Racine N, Pador P, Madigan S. Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Child Behavior Problems: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics [Internet]. 2021. Sep 1 [cited 2021 Sep 12];148(3). Available from: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/148/3/e2020044131. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-044131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Monk C, Lugo-Candelas C, Trumpff C. Prenatal Developmental Origins of Future Psychopathology: Mechanisms and Pathways. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2019. May 7;15:317–44. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Thomas JC, Letourneau N, Campbell TS, Giesbrecht GF, Apron Study Team. Social buffering of the maternal and infant HPA axes: Mediation and moderation in the intergenerational transmission of adverse childhood experiences. Dev Psychopathol. 2018. Aug;30(3):921–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Racine N, Devereaux C, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Adverse childhood experiences and maternal anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry. 2021. Jan 11;21(1):28. doi: 10.1186/s12888-020-03017-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Racine N, McDonald S, Chaput K, Tough S, Madigan S. Pathways from Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences to Substance Use in Pregnancy: Findings from the All Our Families Cohort. J Womens Health 2002. 2021. Feb 1. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8632 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Dunkel Schetter C. Psychological Science on Pregnancy: Stress Processes, Biopsychosocial Models, and Emerging Research Issues. Annu Rev Psychol. 2011. Jan 10;62(1):531–58. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.031809.130727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Herba CM, Glover V, Ramchandani PG, Rondon MB. Maternal depression and mental health in early childhood: an examination of underlying mechanisms in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(10):983–92. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30148-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA, Lambert HK. Childhood Adversity and Neural Development: Deprivation and Threat as Distinct Dimensions of Early Experience. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014. Nov;47:578–91. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Machlin L, Miller AB, Snyder J, McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA. Differential Associations of Deprivation and Threat With Cognitive Control and Fear Conditioning in Early Childhood. Front Behav Neurosci. 2019;13:80. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2019.00080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Greene CA, McCoach DB, Briggs-Gowan MJ, Grasso DJ. Associations among childhood threat and deprivation experiences, emotion dysregulation, and mental health in pregnant women. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2021. May;13(4):446–56. doi: 10.1037/tra0001013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Johnson D, Policelli J, Li M, Dharamsi A, Hu Q, Sheridan MA, et al. Associations of Early-Life Threat and Deprivation With Executive Functioning in Childhood and Adolescence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021. Jul 26;e212511. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Narayan AJ, Lieberman AF, Masten AS. Intergenerational transmission and prevention of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Clin Psychol Rev. 2021. Apr 1;85:101997. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.101997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bellis MA, Hughes K, Ford K, Hardcastle KA, Sharp CA, Wood S, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and sources of childhood resilience: a retrospective study of their combined relationships with child health and educational attendance. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5699-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bethell C, Jones J, Gombojav N, Linkenbach J, Sege R. Positive childhood experiences and adult mental and relational health in a statewide sample: Associations across adverse childhood experiences levels. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(11):e193007–e193007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Crouch E, Radcliff E, Strompolis M, Srivastav A. Safe, stable, and nurtured: Protective factors against poor physical and mental health outcomes following exposure to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2019;12(2):165–73. doi: 10.1007/s40653-018-0217-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Morris AS, Hays-Grudo J, Zapata MI, Treat A, Kerr KL. Adverse and Protective Childhood Experiences and Parenting Attitudes: the Role of Cumulative Protection in Understanding Resilience. Advers Resil Sci. 2021. Sep 1;2(3):181–92. doi: 10.1007/s42844-021-00036-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Floyd K, Morman MT. Affection received from fathers as a predictor of men’s affection with their own sons: Tests of the modeling and compensation hypotheses. Commun Monogr. 2000. Dec 1;67(4):347–61. [Google Scholar]

- 90.LeMasters K, Bates LM, Chung EO, Gallis JA, Hagaman A, Scherer E, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and depression among women in rural Pakistan. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DTA)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.