Abstract

Endowing three-dimensional (3D) displays with flexibility drives innovation in the next-generation wearable and smart electronic technology. Printing circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) materials on stretchable panels gives the chance to build desired flexible stereoscopic displays: CPL provides unusual optical rotation characteristics to achieve the considerable contrast ratio and wide viewing angle. However, the lack of printable, intense circularly polarized optical materials suitable for flexible processing hinders the implementation of flexible 3D devices. Here, we report a controllable and macroscopic production of printable CPL-active photonic paints using a designed confining helical co-assembly strategy, achieving a maximum luminescence dissymmetry factor (glum) value of 1.6. We print customized graphics and meter-long luminous coatings with these paints on a range of substates such as polypropylene, cotton fabric, and polyester fabric. We then demonstrate a flexible textile 3D display panel with two printed sets of pixel arrays based on the orthogonal CPL emission, which lays an efficient framework for future intelligent displays and clothing.

Printing processable circularly polarized luminescence materials on stretchable panels enables flexible 3D displays.

INTRODUCTION

Three-dimensional (3D) displays offer a window for modern electronics, enabling working on scientific visualization, medical imaging, virtual prototyping, human entertainment experience, and so on (1–3). In particular, endowing these panels with flexible form factors provides opportunities for wearable, mobile, and smart electronic displays—to realize immersive human-machine interactions (4–8). In traditional 3D stereoscopic displays, two different images are presented in two different eyes using linear-polarized light with mutually perpendicular polarization directions while causing limited viewpoints and poor contrast (9, 10).

Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL)—generated from chiral materials—provides a helping hand using its optical rotation characteristic to improve contrast and reduce perceptual distortion in rigid 3D panels (11–15). Printing CPL materials on moving, deformable, and free-form surfaces serves to fabricate large-scale and high-performance integral imaging 3D displays (16–19); however, CPL-based flexible 3D screens have not been achieved because it is challenging to obtain printability coupled with strong CPL characteristics using current CPL-active structures (20, 21).

Chiral liquid crystals (CLCs), a kind of quasi-1D photonic crystals, are widely used in imaging and display fields (22, 23). Benefiting from their fantastic light manipulation capabilities and outstanding compatibility, CLCs coupled with emitters have been demonstrated to realize CPL with luminescence dissymmetry factor (glum) values beyond 10−1 magnitude based on formed helical structures (24–26). However, current CPL-active CLC materials are limited to the mobile phase and need to be sandwiched as layered devices or confined into a cell structure, preventing the practice for flexible 3D displays (27–29). Thus, printable CLC-composed CPL materials are highly desired.

Here, we report a printable CLC-based CPL case using a designed confining helical co-assembly strategy. We encapsulate the CLC precursors into a polymer shell to form solid-state CPL-active photonic paints (CPL-PPs) that exhibit intense CPL emission with a maximum glum value of 1.6, showing an advancement in both performance and processability. Furthermore, we demonstrate flexible full-color 3D imaging displays using two groups of pixel arrays with orthogonal CPL emission by dispensing printing synthesized stable CPL-PPs, meeting a new mindset for next-generation flexible 3D display devices (30–32).

RESULTS

Encapsulation of CPL materials using a confining helical co-assembly strategy

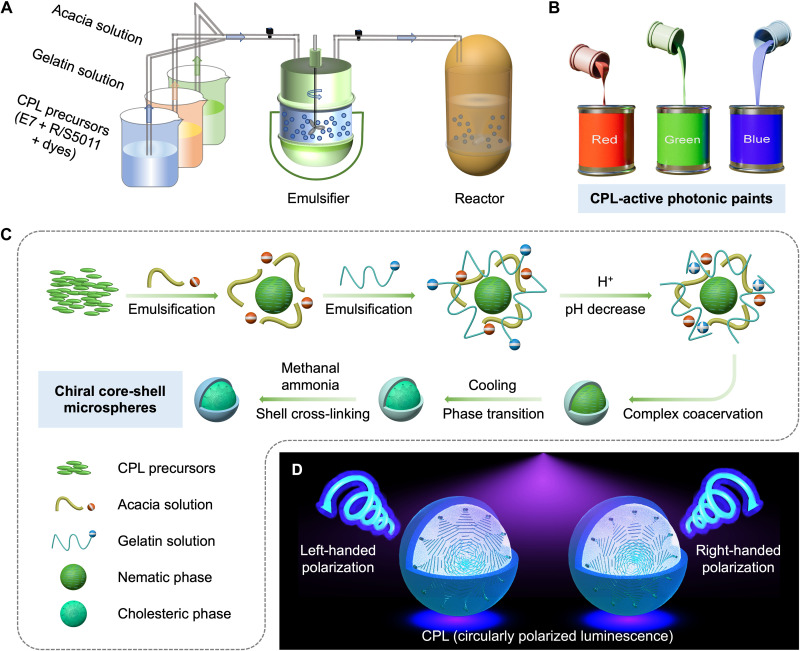

To prepare CPL-PPs, we initiated by noting that CLC and dyes in the core must be uniformly assembled to form a spiral superstructure to ensure intense CPL and that the fluidity of the obtained CPL structures must be limited. We therefore proposed a confining helical co-assembly strategy, whereby the CLC precursor mixture was emulsified and subsequently coacervated with gelatin and acacia aqueous solution before being crosslinked for future off-line processing into structurally colored CPL-PPs with intense CPL emission (Fig. 1). Specifically, we chose S5011 and R5011 chiral dopants with high helical twisting power to twist the nematic liquid crystal host E7 with a wide temperature range into helical superstructures (fig. S1 and table S1). Fluorescent dyes with good compatibility and CLCs are incorporated to achieve CPL with the opposite handedness of helical superstructures because of the photonic bandgap (PBG) effect (fig. S2). We then achieved the CLC droplet dispersion using natural polymer acacia and gelatin as the emulsifier and controlling the pH, which allows the gelatin-acacia coacervates to cover the CLC droplets. After emulsification and coacervation, gelatin reacts with formaldehyde to produce amine aldehyde condensation, and gelatin molecules are crosslinked into a network structure to form a firm shell. CPL-PPs were obtained after further centrifugation and purification under the ambient condition.

Fig. 1. Large-scale synthesis of CPL-PPs.

(A) Flow chart showing the process to prepare CPL-PPs. (B) RGB CPL-PPs. (C) Schematic summarizing the preparation of chiral core-shell microspheres: The CPL precursors composed of E7 liquid crystals, R/S5011 chiral dopants, and dyes were emulsified successively with acacia solution and gelation solution. Then the coacervation reaction occurred when reducing the pH of the system, and the microspheres precipitated. Cooling promotes the phase transition of CLC, and gelatin molecules are crosslinked into a network structure to firm the shell. (D) Schematic illustration of materials and the left- or right-handed CPL emitted from as-prepared microspheres upon ultraviolet (UV) irradiation.

We show an example, proving that the synthesis of CPL-PPs is controllable and macroscopic (Fig. 2A). We tuned the precursors and fabricated left- and right-handed red, green, blue (RGB) CPL-PPs (Fig. 2B and fig. S3) in which the diameter of the microspheres was concentrated ca. 15 μm (Fig. 2C). Fluorescence microscopy confirmed the uniform and bright luminescence of a single microsphere (fig. S4). Polarized optical microscopy (POM) images of the CPL-PPs showed a Maltese cross pattern with characteristic stripes (33), indicating that the CLC cores have a centrosymmetric parallel orientation with a radially distributed helical axis (Fig. 2D). Under ultraviolet (UV) light irradiation, these RGB CPL-PPs exhibited corresponding bright photoluminescence regardless of the helical superstructures (Fig. 2E and fig. S5). Moreover, we demonstrated cyan-, pink-, and yellow-emissive CPL-PPs by mixing two kinds of CPL-PPs (B + G, B + R, and G + R) (Fig. 2, F to H). Notably, we also achieved standard white-emissive CPL-PPs with a CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram coordinate value of (0.33, 0.33) by blending three kinds of CPL-PPs (Fig. 2I). We calculated the chromaticity for these CPL-PPs and plotted them on the CIE 1931 chromaticity diagram (Fig. 2J). The chromaticity of the primary color RGB defines a triangle area. According to Glassman’s law, all colors can be obtained by mixing RGB colors in an appropriate proportion (34).

Fig. 2. Characterization of CPL-PPs.

(A) Photographs of prepared CPL-PPs. Bottle volume, 1000 ml. Scale bar, 4 cm. (B) Photographs showing right- and left-handed RGB-emissive CPL-PPs. Scale bar, 4 cm. (C) Bright-field optical microscopy image of the typical CPL-PPs sample in transmission mode. Scale bar, 100 μm. (D) Bright-field optical microscopy images in reflection mode (the top row) and corresponding POM images of microspheres (the bottom row), from left to right are left-handed red emissive, right-handed red emissive, left-handed green emissive, right-handed green emissive, left-handed blue emissive, and right-handed blue emissive, respectively. Scale bars, 3 μm. (E) Corresponding PL spectra of the CPL-PPs in (B). a.u., arbitrary units. (F to I) Cyan-emissive (F), pink-emissive (G), yellow-emissive (H), and white-emissive (I) CPL-PPs obtained by mixing two or three kinds of CPL-PPs (B + G, B + R, G + R, and B + G + R, respectively). Insets showing their photographs under 365 nm UV irradiation. Scale bars, 1 cm. (J) CIE 1931 chromaticity coordinates of different emissions of CPL-PPs, which are (0.16, 0.05) for blue emission, (0.18, 0.62) for green emission, (0.52, 0.46) for red emission, and (0.33, 0.33) for white emission, respectively. (K) FTIR spectra of the CLC core, polymer shell, and CPL-PPs. (L) Thermogravimetry–differential scanning calorimetry (TG-DSC) curves of the CPL-PPs between 30° and 800°C in a nitrogen atmosphere. (M) DSC curves of heating-cooling cycles of the CPL-PPs between 0° and 100°C in a nitrogen atmosphere.

Figure 2K shows the Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) of CPL-PPs, the individual polymer shells, and the corresponding CLC cores. The strong peaks at 3298 cm−1 (O─H and N─H bonds) and 1636 cm−1 (C═O bond) are assigned to the CPL-PPs and polymer shells, while the adsorption peak at 2225 cm−1 (C≡N bond) is only assigned to the CLC cores, which evidences that the packaged shell has no effect on the cholesteric helicoid distorted in space. The thermogravimetry (TG) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) curves of the CPL-PPs are depicted in Fig. 2L. There are two pyrolytic stages that can be ascribed to water loss on the surface of CPL-PPs at approximately 30° to 150°C and thermal decomposition of the CLC cores and polymer shells in the temperature range of 150° to 800°C, respectively. Figure 2M shows an obvious endothermic peak in the DSC curve of CPL-PPs upon heating, and the peak at approximately 53.8°C reveals the anisotropy-isotropic phase transition, which is consistent with the phase transition temperature of the CLC cores (fig. S6). It also shows a similar isotropic-anisotropy phase transition upon the cooling process, and it is basically coincident with the temperature upon heating. No other endothermic peaks below 100°C were observed, indicating that the polymer shells are stable below 100°C.

Bright CPL with high glum values from CPL-PPs

To study the chirality of CPL-PPs, we first tested their circular dichroism (CD) spectra, which displayed the positive and negative signals (fig. S7). The reflection color of CPL-PPs arises from the Bragg reflection and CD properties brought by their periodic helical superstructures (35). For example, right-handed CPL-PPs can selectively reflect right-handed circularly polarized light because the propagation of light with wavelengths located in the PBG is forbidden, whereas left-handed circularly polarized light is transmitted and vice versa. Meanwhile, because of the forbidden nature of CPL-PPs within the PBG, they can emit CPL that is opposite to their spiral superstructures.

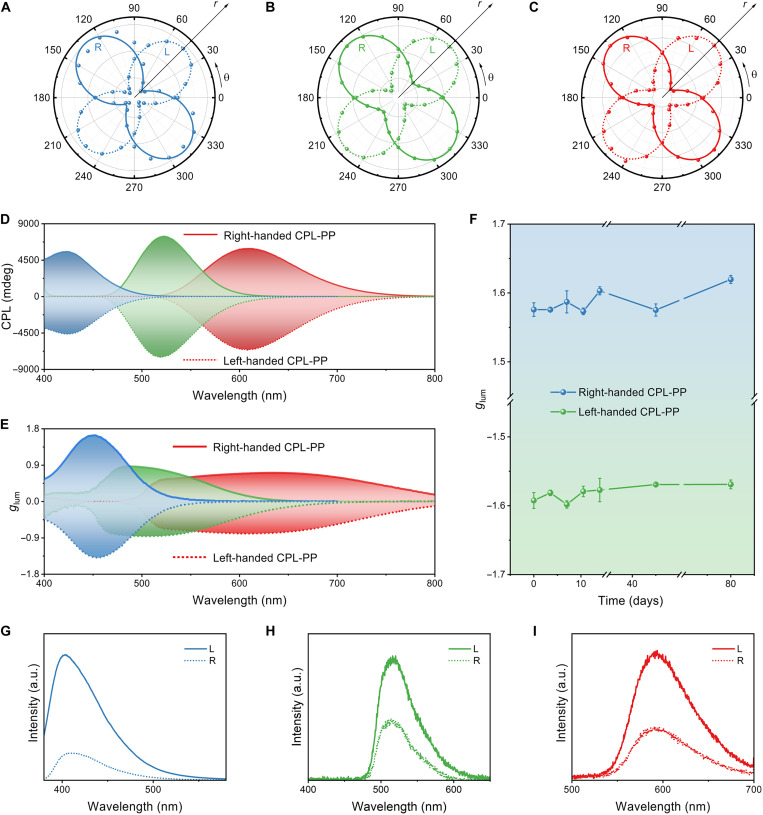

To corroborate the CPL characteristic from the CPL-PPs, we first used a rotated analyzer, and the optical path is shown in fig. S8, of which the intensity of transmitted light passing through a quarter-wave plate (QWP) is recorded. The QWP can convert CPL emitted from CPL-PPs to linear-polarized light, which can be facilely examined by a linear analyzer. As shown in Fig. 3 (A to C), the left- and right-handed CPL emitted by CPL-PPs with RGB color emissions were converted into linear-polarized light with an orthogonal polarization plane, and the results showed excellent circular polarization characteristics of the emissions from the CPL-PPs. Furthermore, we qualified the CPL performance of the CPL-PPs using a CPL spectrometer under the ambient condition, in which the excitation light was provided by a Xe lamp equipped with a monochromator. Strong mirror-symmetric CPL responses appeared near the PL peaks of dyes with a negative sign for left-handed CPL-PPs and a positive sign for right-handed CPL-PPs (Fig. 3D and fig. S9), resulting from suppression of the CPL component with the same handedness as the chiral medium helix. The CPL-PPs achieved |glum| values up to 1.6 (Fig. 3E), which was due to the uniform morphology of dye-doped CLCs in the CPL-PPs to ensure a highly ordered helical arrangement and prominent PBG of CLCs, and then CLCs and dyes in the CPL-PPs can be well coupled.

Fig. 3. CPL performance.

(A to C) Emission intensity of blue-emissive (A), green-emissive (B), and red-emissive (C) CPL-PPs as a function of polarization angle, where θ represents the transmission angle and r refers to the transmittance. (D) CPL spectra of red-, green-, and blue-emissive CPL-PPs. The solid (dashed) curves correspond to right (left)-handed materials. (E) Calculated glum values corresponding to (D). (F) glum evolution of blue-emissive CPL-PPs under ambient atmosphere for 80 days. Error bars correspond to the SD of three measurements. (G to I) Photoluminescence spectra of the right-handed blue-emissive (G), green-emissive (H), and red-emissive (I) CPL-PPs measured through left-handed (solid line) and right-handed (dashed line) circular polarization filters, respectively.

Our prepared CPL-PPs showed an advance compared to the reported CPL-active materials in terms of both performance and processability (fig. S10 and table S2). Moreover, we placed the samples under the ambient condition to evaluate the long-term stability of CPL-PPs and found that the glum was retained for over 80 days (Fig. 3F). It is noted that the phase transition affected the properties of CLCs within our CPL-PPs, and the CPL performance decreased slightly with the increase of temperature, which was ascribed to the decreased overlap of the dye emission with the PBG of the CLCs (fig. S11). We then verified the CPL effect by the luminescence spectra through left- and right-handed circular polarized filters, the CPL of the same handedness can pass through, and the CPL of the opposite handedness is forbidden, the spectrum showing obvious differences (Fig. 3, G to I, and fig. S12). From this perspective, these as-fabricated CPL-PPs are considered to be ideal candidates to print orthogonal CPL pixel arrays for flexible 3D displays.

Writability and printability of CPL-PPs

The fluidic nature of CPL-PPs and their adhesion can be used to produce large-scale customized graphics or coatings on various substrates via printing. We used the optimized CPL-PPs to directly write the text “CPL” on a polypropylene plate using dispensing printing (Fig. 4A). As expected, the structural colors are not dependent on the angle of the text and it emits bright circularly polarized fluorescence under UV light irradiation (Fig. 4B). In addition, printing does not have strict requirements on the surface smoothness of materials. It can also be extended to flexible substrates (fig. S13), enabling direct writing on the cotton fabric (Fig. 4C) or polyester (PET) fabric (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4. Printing CPL-PPs to form circularly polarized luminous patterns.

(A) Dispenser for direct pattern writing with a moving nozzle. (B to D) “CPL” patterns on different substrates: from the rigid polypropylene plate (B) to flexible cotton fabric (C) and flexible PET fabric (D). Scale bars, 1 cm. (E and F) Spray printing of CPL-PPs on PET substrates observed under natural light (E) and upon 365-nm UV irradiation (F). Scale bars, 1 cm. (G and H) Emission intensity of left-handed (left column) and right-handed (right column) red-emissive luminous fabrics as a function of polarization angle, where θ is the transmission angle and r is the transmittance (G). The results evidencing the circular polarization characteristic of luminescence is maintained after spray printing (H). (I) Photograph of a 1.5-m-long luminous textile printed by CPL-PPs. (J) Photographs of the luminous fabrics after exposure in the acid solution, pure water, basic solution, and n-hexane solution for 7 days, respectively. Scale bar, 5 mm.

We then chose PET fabric with high strength and good elasticity as the flexible substrate, and we exhibited typical RGB-emissive circularly polarized luminous textiles using spray printing (Fig. 4, E and F). The excitation-emission matrix spectra of these luminous textiles demonstrated that RGB fluorescence can be achieved with the same excitation range, and spray printing does not affect the luminous properties of the CPL-PPs on the fabric (fig. S14). The polarization state of emissions from luminous fabrics is a crucial characteristic for further applications. Similarly, we proved the circular polarization characteristic of fabric luminescence by converting the CPL to linear polarization light and then detecting the polarization direction (Fig. 4, G and H). Furthermore, we produced a circularly polarized luminous textile with considerable sizes over 150 cm by 40 cm on a flexible fabric substrate using the same method (Fig. 4I). The typical top-view scanning electron microscopy images reveal that the CPL-PPs are evenly coated on the fabric, which contributes to the uniform luminescence (fig. S15). Thus, the uniform luminous intensity with a circular polarization state indicates that these fabrics are well suited for making large-area luminous and display textiles at scale.

The as-made CPL-PPs showed good resistance to chemical and mechanical treatments, which was significant for luminous coatings. In the durability test, we soaked typical CPL-PPs in the acidic solution, basic solution, pure water, and n-hexane, respectively, for over 7 days, and the micromorphology after each test was found to be similar to that of the primary samples (fig. S16). We also evaluated the coating stability of the luminous fabrics and found no obvious changes in the luminescence spectra after durability examinations (Fig. 4J and fig. S17).

Flexible 3D display with printed orthogonal CPL matrix

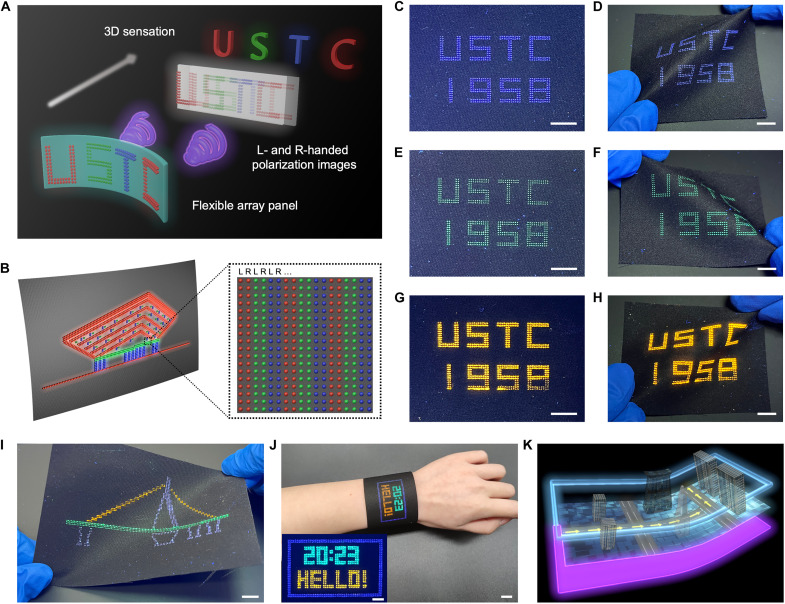

Last, the industrial relevance of this scalable production of CPL-PPs is illustrated by further processing the water-dispersible paints into orthogonal pixel arrays that can be used as flexible 3D display panels. This addresses the current limitations, in terms of both the machinability and the high-quality CPL needed, for these materials to be used for flexible 3D displays. Figure 5A illustrates the basic principle that after passing through polarized glasses, images with orthogonal states of left- and right-handed circular polarization are separated to enter the left and right eyes. Once humans’ left and right eyes receive these two slightly different images, the brain can fuse these images to extract depth information for a single percept, thus forming a 3D sensation. Accordingly, we designed flexible self-emissive display panels composed of two sets of full-color pixel arrays on flexible PET fabric substrates, where each adjacent left- and right-handed pixels function as a microunit to render two different images with orthogonal circular polarization states for the left and right eyes (Fig. 5B). Through a circularly polarized filter, CPL with the same rotation is allowed to pass through, while the opposite CPL is prohibited from passing through; thus, the pixel arrays with different rotations exhibited color saturation or elimination, which can be distinguished by naked eyes (fig. S18). Therefore, these CPL-PPs are considered to be ideal candidates to prepare flexible 3D display panels.

Fig. 5. Flexible 3D display based on printed orthogonal CPL matrix.

(A) Fabrication strategy of the flexible 3D display. Left- and right-handed polarization images can be achieved from flexible array panels with printed CPL-active orthogonal matrix. Through a polarization glass, the two images enter the left and right eyes, respectively, and the brain can fuse the two images into 3D sensation. (B) Schematic diagram of a flexible array panel, containing pixelated CPL arrays obtained by printing CPL-PPs on the flexible substrates. (C to H) Photographs of “USTC 1958” patterns obtained by alternately printing left- and right-handed CPL-PPs with RGB emissions on PET fabrics. Observed under natural light [(C), (E), and (G)] and under UV irradiation [(D), (F), and (H)]. Scale bars, 1 cm. (I) Photograph of the bent flexible 3D display panel based on the orthogonal CPL matrix while a pattern was displayed on it. Scale bar, 1 cm. (J) Photograph of a wearable watch-like flexible 3D display wearing on the wrist. Scale bar, 1 cm. Inset photograph showing the display panel. Scale bar, 5 mm. (K) Conceptual image of a wearable 3D display device, demonstrating the stereoscopic navigation information that is displayed on the smart wear.

During the dispensing printing process, left- and right-handed CPL-PPs were alternately printed into left and right parts as individual pixels to form a display panel (fig. S19). By selectively printing distinct CPL-PPs on PET fabrics, we fabricated various luminous arrays with the same “USTC 1958” patterns (Fig. 5, C, E, and G), and multicolor images of these fabricated patterns were observed in the far field by naked eyes. We demonstrated the flexible display performance by bending the panels, and the bent panels showed bright and uniform emission across the entire luminous area (Fig. 5, D, F, and H). Furthermore, inspired by the outstanding performance of patterned multicolor arrays, we achieved a suspension bridge pattern based on such a left- and right-handed luminous RGB pixel array on a flexible substrate (Fig. 5I), which manifests the applicability of random arrays based on CPL as self-emissive full-color panels for flexible 3D display.

To demonstrate the wearability, we showed a wearable 3D display based on the textile platform, and the textile 3D display was realized as a soft and comfortable watch-like panel wearing on the wrist, which can program time, letters, and other arbitrary information at will (Fig. 5J). We created a conceptual design for wearable textile 3D displays that have the potential to dynamically display stereoscopic information once combined with backlight and smart devices, function as smart wear with intelligent applications such as 3D addressing and navigation, and be premium clothing (Fig. 5K). In short, these flexible 3D display panels formed by printing CPL-PPs on the fabric provide a demonstration for next generation of flexible 3D display devices.

DISCUSSION

In this work, we report a confining helical co-assembly strategy for the large-scale production of CPL-PPs by encapsulating dye-doped CLCs in polymer shells. The as-prepared CPL-PPs achieved the glum value up to 1.6 and satisfactory stability over 80 days. This paint can be used for printing customized graphics or coatings with circular polarization characteristics on various substrates, such as flexible PET fabrics. We thereafter demonstrated a flexible 3D display via printing CPL-PPs as display panels that comprised an orthogonal CPL matrix. Furthermore, we presented a wearable 3D display device and conceptually designed a smart wear that can dynamically display stereoscopic information. It is expected that the fabricated flexible and wearable 3D display panel will enable a new mindset for next-generation display and illumination devices.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The nematic liquid crystal host E7 (n = 1.747, Tc = 60°C) and the chiral dopants R/S5011 were purchased from Shijiazhuang Yesheng Chemical Technology Co. Ltd. The fluorescent dyes 4-(dicyanomethylene)-2-methyl-6-(4-dimethylaminostyryl)-4H-pyran (DCM, 95%), coumarin 7 (C7, 98%), and 7-hydroxy-4-(trifluoromethyl)coumarin (CouOH, 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Gelatins, chloroform, and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, 98%) were purchased from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co. Ltd. Arabic gum (mpa·s, 60 to 100), acetic acid (99%), and formaldehyde solution (37 to 40% in water) were purchased from Adamas-Beta. All chemical reagents were used as received without further purification.

Preparation of the CPL precursors

First, we prepared left- and right-handed CLCs by mixing E7 with chiral dopants S5011 and R5011, respectively. A series of chiral dopants with weight ratios of 2.3, 2.8, and 3.3 weight % (wt %) were added to tune the PBG of CLCs to the red, green, and blue regions, respectively. The red-, green-, or blue-emissive dyes DCM, C7, and CouOH were added to the CLCs with the corresponding PBG with doping concentrations of 1 wt %, respectively. Nematic liquid crystals, chiral dopants, and dyes were dispersed in chloroform with ultrasonic treatment for 5 min, and the CLC mixture was obtained after evaporating the solvent in a drying box.

Large-scale production of the CPL-PPs

We first dissolved the arabic gum and the gelatin in water with heating at 60°C for 2 hours to prepare the acacia solution and the gelatin solution with concentrations of 2.0 wt %. We then homogenized the obtained CPL precursors with acacia solution for 30 min at 60°C using a high-speed emulsifier (IKA T18, Germany) to make the CLC emulsion (weight ratio of the CPL precursors: 2.0 wt % acacia solution = 1: 25). The same amount of 2.0 wt % gelatin solution was added, and emulsification was continued for 30 min. Then, the pH value of the emulsion was adjusted to 4 by dripping acetic acid solution and kept for 1 hour to induce coacervation. Subsequently, the coalesced emulsion was cooled to 0°C, and formaldehyde solution was added and maintained for 30 min. The pH value was adjusted to 8.5 by adding sodium hydroxide to promote the crosslinking of gelatin and arabic gum with vigorous stirring. The chiral core-shell microspheres can be obtained after three dispersions in deionized water and centrifugation, and the CPL-PPs are obtained by dispersing the microspheres in water.

Preparation of the printed patterns with CPL characteristics

We used a pneumatic extrusion-type microelectronic printer (MP1100, Prtronic, China) with programmable control of temperature and pressure to perform pattern printing. The as-obtained CPL-PPs were placed in a 5.0-ml syringe barrel with a nozzle with an inner diameter of 160 μm. We first adhered the printing substrates, including polypropylene plates, cotton fabrics, and PET fabrics, to the printer plane with a 10.0 wt % polyvinyl alcohol aqueous solution, and the release amount of CPL-PPs was precisely controlled by adjusting the printing speed and pressure. All patterns can be freely customized by the drawing software that comes with the printer. We also prepared large-scale luminous coatings with circular polarization characteristics by spray printing CPL-PPs onto PET fabric substrates using a pneumatic spray gun (SEBA W-71, Japan).

Fabrication of textile 3D display panels

The pixelated orthogonal CPL arrays were fabricated by sequentially printing RGB CPL-PPs as individual pixels at specific positions in flexible PET fabric substrates according to the designed patterns. The detailed printing process is similar to that described above. The left- and right-handed CPL-PPs were alternately printed into the left and right parts of one unit, respectively.

Characterizations

Reflectance and fluorescence spectra were measured with a ultraviolet/visible/near infrared spectrometer (Shimadzu, 3700 DUV) and a fluorescence spectrometer (Hitachi, F-4700), respectively. CD and CPL spectra were measured on a JASCO J-1500 spectrophotometer and a JASCO CPL-300 spectrophotometer, respectively. Bright-field optical microscopy and POM images were recorded on an upright materials microscope (Mshot MP41). Fluorescence microscopy images were obtained using an upright fluorescence microscope (Olympus, BX53) under the excitation of a mercury lamp. The FTIR spectrum was measured with an FTIR microscope (Nicolet iN10MX). The TG-DSC curve and DSC curves were recorded on a thermogravimeter (TA Discovery TGA) and a differential scanning calorimeter (Shimadzu, DSC-60), respectively. Scanning electron microscopy images were obtained by using a field emission scanning electron microanalyzer (Zeiss Supra 40 scanning electron microscope at an acceleration voltage of 1.5 kV). The circular polarization characteristic of each emission of RGB CPL-PPs and printed patterns on PET fabrics was demonstrated by converting CPL to linearly polarized light using a quarter-wave slice (QWP, 350 to 850 nm; Thorlabs), and then, the direction of linear polarization was discriminated by a rotating polarizer (400 to 700 nm; Thorlabs).

Acknowledgments

We thank J.-W. Liu and H. Wang at the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) for the help in materials printing, F. Fan and R. Liu at USTC for the circular polarization characteristic test, and M. Ma group at USTC for the CD test. We thank J. Zhou at the Instruments Center for Physical Science of USTC for the temperature-dependent reflection spectra test. This work was partially carried out at the USTC Center for Micro and Nanoscale Research and Fabrication, and we thank Y. Li for the help on micro/nano fabrication and characterization.

Funding: This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant 2021YFA1500400); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 22071226, U1932213, 22271265, and 22101270); the New Cornerstone Investigator Program; the Hundred Talent Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant KJ2060007002); the Collaborative Innovation Program of Hefei Science Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant 2022HSC-CIP016); the Funding of University of Science and Technology of China (grants KY2060000168, YD2060002013, KY2060000198, and KY2060000235); the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grants 2018YFE0202201 and 2021YFA0715700); and the University Synergy Innovation Program of Anhui Province (grant GXXT-2019-028).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: T.Z. and S.-H.Y. Methodology: M.Zhang, Q.G., Y.Z., S.Z., Z.T., S.J., and M.Zhu. Investigation: M.Zhang, Q.G., Y.W., and G.L. Visualization: M.Zhang and Z.L. Funding acquisition: T.Z. and S.-H.Y. Project administration: T.Z. and S.-H.Y. Supervision: T.Z. and S.-H.Y. Writing—original draft: M.Zhang and Q.G. Writing—review and editing: T.Z. and S.-H.Y.

Competing interests: T.Z. and M.Zhang are inventors on patent applications (CN114907864A and CN116107099A) submitted by the University of Science and Technology of China that cover CPL-active liquid crystal microcapsules and flexible 3D display panel. All other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S19

Tables S1 and S2

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.E. Downing, L. Hesselink, J. Ralston, R. Macfarlane, A three-color, solid-state, three-dimensional display. Science 273, 1185–1189 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 2.D. Fattal, Z. Peng, T. Tran, S. Vo, M. Fiorentino, J. Brug, R. G. Beausoleil, A multi-directional backlight for a wide-angle, glasses-free three-dimensional display. Nature 495, 348–351 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.H. Yu, K. Lee, J. Park, Y. Park, Ultrahigh-definition dynamic 3D holographic display by active control of volume speckle fields. Nat. Photon. 11, 186–192 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 4.D. D. Zhang, T. Y. Huang, L. Duan, Emerging self-emissive technologies for flexible displays. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902391 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.X. Shi, Y. Zuo, P. Zhai, J. Shen, Y. Yang, Z. Gao, M. Liao, J. Wu, J. Wang, X. Xu, Q. Tong, B. Zhang, B. Wang, X. Sun, L. Zhang, Q. Pei, D. Jin, P. Chen, H. Peng, Large-area display textiles integrated with functional systems. Nature 591, 240–245 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.R. T. Su, S. H. Park, X. Ouyang, S. I. Ahn, M. C. McAlpine, 3D-printed flexible organic light-emitting diode displays. Sci. Adv. 8, eabl8798 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.J. Kim, H. J. Shim, J. Yang, M. K. Choi, D. C. Kim, J. Kim, T. Hyeon, D. H. Kim, Ultrathin quantum dot display integrated with wearable electronics. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700217 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.S. Liu, K. M. B. Yang, H. Li, X. Tao, Textile electronics for VR/AR applications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2007254 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.D. E. Smalley, E. Nygaard, K. Squire, J. van Wagoner, J. Rasmussen, S. Gneiting, K. Qaderi, J. Goodsell, W. Rogers, M. Lindsey, K. Costner, A. Monk, M. Pearson, B. Haymore, J. Peatross, A photophoretic-trap volumetric display. Nature 553, 486–490 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.H. Urey, K. V. Chellappan, E. Erden, P. Surman, State of the art in stereoscopic and autostereoscopic displays. Proc. IEEE 99, 540–555 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.M. Song, L. Feng, P. Huo, M. Liu, C. Huang, F. Yan, Y. Q. Lu, T. Xu, Versatile full-colour nanopainting enabled by a pixelated plasmonic metasurface. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 71–78 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.M. Schadt, Liquid crystal materials and liquid crystal displays. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 27, 305–379 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 13.L. Z. Feng, J.-J. Wang, T. Ma, Y.-C. Yin, K.-H. Song, Z.-D. Li, M.-M. Zhou, S. Jin, T. Zhuang, F.-J. Fan, M.-Z. Zhu, H.-B. Yao, Biomimetic non-classical crystallization drives hierarchical structuring of efficient circularly polarized phosphors. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.T. T. Zhuang, Y. Li, X. Gao, M. Wei, F. P. García de Arquer, P. Todorović, J. Tian, G. Li, C. Zhang, X. Li, L. Dong, Y. Song, Y. Lu, X. Yang, L. Zhang, F. Fan, S. O. Kelley, S. H. Yu, Z. Tang, E. H. Sargent, Regioselective magnetization in semiconducting nanorods. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 192–197 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Y. L. Li, N.-N. Li, D. Wang, F. Chu, S.-D. Lee, Y.-W. Zheng, Q.-H. Wang, Tunable liquid crystal grating based holographic 3D display system with wide viewing angle and large size. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 1–10 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.L. Mu, M. He, C. Jiang, J. Wang, C. Mai, X. Huang, H. Zheng, J. Wang, X. H. Zhu, J. Peng, Inkjet printing a small-molecule binary emitting layer for organic light-emitting diodes. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 6906–6913 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 17.X. Q. Zhan, F.-F. Xu, Z. Zhou, Y. Yan, J. Yao, Y. S. Zhao, 3D laser displays based on circularly polarized lasing from cholesteric liquid crystal arrays. Adv. Mater. 33, 2104418 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.L. Huang, X. Chen, H. Mühlenbernd, H. Zhang, S. Chen, B. Bai, Q. Tan, G. Jin, K.-W. Cheah, C.-W. Qiu, J. Li, T. Zentgraf, S. Zhang, Three-dimensional optical holography using a plasmonic metasurface. Nat. Commun. 4, 1–8 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 19.T. W. Duan, Y. Y. Zhou, Leveraging hierarchical chirality in perovskite(-inspired) halides for transformative device applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 29, 2200792 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.J. Lv, X. Gao, B. Han, Y. Zhu, K. Hou, Z. Tang, Self-assembled inorganic chiral superstructures. Nat. Rev. Chem. 6, 125–145 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Y. Zhang, S. Yu, B. Han, Y. Zhou, X. Zhang, X. Gao, Z. Tang, Circularly polarized luminescence in chiral materials. Matter 5, 837–875 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 22.X. Zhang, Y. Xu, C. Valenzuela, X. Zhang, L. Wang, W. Feng, Q. Li, Liquid crystal-templated chiral nanomaterials: From chiral plasmonics to circularly polarized luminescence. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 1–29 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.M. J. Zhang, Y. Wang, Y. Zhou, H. Yuan, Q. Guo, T. Zhuang, Amplifying inorganic chirality using liquid crystals. Nanoscale 14, 592–601 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.X. H. Gao, J. Wang, K. Yang, B. Zhao, J. Deng, Regulating the helical chirality of racemic polyacetylene by chiral polylactide for realizing full-color and white circularly polarized luminescence. Chem. Mater. 34, 6116–6128 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 25.X. F. Yang, M. Zhou, Y. Wang, P. Duan, Electric-field-regulated energy transfer in chiral liquid crystals for enhancing upconverted circularly polarized luminescence through steering the photonic bandgap. Adv. Mater. 32, 2000820 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D. X. Han, X. Yang, J. Han, J. Zhou, T. Jiao, P. Duan, Sequentially amplified circularly polarized ultraviolet luminescence for enantioselective photopolymerization. Nat. Commun. 11, 1–8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Z.-L. Gong, X. Zhu, Z. Zhou, S. W. Zhang, D. Yang, B. Zhao, Y. P. Zhang, J. Deng, Y. Cheng, Y. X. Zheng, S. Q. Zang, H. Kuang, P. Duan, M. Yuan, C. F. Chen, Y. S. Zhao, Y. W. Zhong, B. Z. Tang, M. Liu, Frontiers in circularly polarized luminescence: Molecular design, self-assembly, nanomaterials, and applications. Sci. China Chem. 64, 2060–2104 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.C. Yang, B. Wu, J. Ruan, P. Zhao, L. Chen, D. Chen, F. Ye, 3D-printed biomimetic systems with synergetic color and shape responses based on oblate cholesteric liquid crystal droplets. Adv. Mater. 33, 2006361 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.S. Liu, X. Liu, Y. Wu, D. Zhang, Y. Wu, H. Tian, Z. Zheng, W. H. Zhu, Circularly polarized perovskite luminescence with dissymmetry factor up to 1.9 by soft helix bilayer device. Matter 5, 2319–2333 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 30.C. Larson, B. Peele, S. Li, S. Robinson, M. Totaro, L. Beccai, B. Mazzolai, R. Shepherd, Highly stretchable electroluminescent skin for optical signaling and tactile sensing. Science 351, 1071–1074 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.X. Tian, P. M. Lee, Y. J. Tan, T. L. Y. Wu, H. Yao, M. Zhang, Z. Li, K. A. Ng, B. C. K. Tee, J. S. Ho, Wireless body sensor networks based on metamaterial textiles. Nat. Electron. 2, 243–251 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Z. T. Zhang, L. Cui, X. Shi, X. Tian, D. Wang, C. Gu, E. Chen, X. Cheng, Y. Xu, Y. Hu, J. Zhang, L. Zhou, H. H. Fong, P. Ma, G. Jiang, X. Sun, B. Zhang, H. Peng, Textile display for electronic and brain-interfaced communications. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800323 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.T. Yang, D. Yuan, W. Liu, Z. Zhang, K. Wang, Y. You, H. Ye, L. T. de Haan, Z. Zhang, G. Zhou, Thermochromic cholesteric liquid crystal microcapsules with cellulose nanocrystals and a melamine resin hybrid shell. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 14, 4588–4597 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Z. Y. Luo, Y. Chen, S. T. Wu, Wide color gamut LCD with a quantum dot backlight. Opt. Express 21, 26269–26284 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Y. T. Sang, J. L. Han, T. H. Zhao, P. F. Duan, M. H. Liu, Circularly polarized luminescence in nanoassemblies: Generation, amplification, and application. Adv. Mater. 32, 1900110 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.K. Takaishi, K. Iwachido, R. Takehana, M. Uchiyama, T. Ema, Evolving fluorophores into circularly polarized luminophores with a chiral naphthalene tetramer: Proposal of excimer chirality rule for circularly polarized luminescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 15,141, 6185–6190 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.K. Takaishi, S. Hinoide, T. Matsumoto, T. Ema, Axially chiral peri-Xanthenoxanthenes as a circularly polarized luminophore. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 30,141, 11852–11857 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Z. B. Sun, 2, 2′-Diamino-6, 6′-diboryl-1, 1′-binaphthyl: A versatile building block for temperature-dependent dual fluorescence and switchable circularly polarized luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 15,58, 4840–4846 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.L. Fang, M. Li, W. B. Lin, C. F. Chen, Enantiopure (P)-and (M)-3, 14-bis (O-hydroxyaryl) tetrahydrobenzo [5] helicenediols and their helicene analogues: Synthesis, amplified circularly polarized luminescence and catalytic activity in asymmetric hetero-Diels–Alder reactions. Tetrahedron 74, 7164–7172 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 40.K. Kikuchi, J. Nakamura, Y. Nagata, H. Tsuchida, T. Kakuta, T. Ogoshi, Y. Morisaki, Control of circularly polarized luminescence by orientation of stacked π-electron systems. Chem. Asian J. 10,14, 1681–1685 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.J. Kumar, T. Kawai, T. Nakashima, Circularly polarized luminescence in chiral silver nanoclusters. Chem. Commun. 53, 1269–1272 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.L. Yao, G. Niu, J. Li, L. Gao, X. Luo, B. Xia, Y. Liu, P. du, D. Li, C. Chen, Y. Zheng, Z. Xiao, J. Tang, Circularly polarized luminescence from chiral tetranuclear copper(I) iodide clusters. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 1255–1260 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.J. J. Cheng, J. Hao, H. Liu, J. Li, J. Li, X. Zhu, X. Lin, K. Wang, T. He, Optically active CdSe-dot/CdS-rod nanocrystals with induced chirality and circularly polarized luminescence. ACS Nano 12, 5341–5350 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Y. H. Kim, Y. Zhai, E. A. Gaulding, S. N. Habisreutinger, T. Moot, B. A. Rosales, H. Lu, A. Hazarika, R. Brunecky, L. M. Wheeler, J. J. Berry, M. C. Beard, J. M. Luther, Strategies to achieve high circularly polarized luminescence from colloidal organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite nanocrystals. ACS Nano 14, 8816–8825 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.C. Zhang, Z. S. Li, X. Y. Dong, Y. Y. Niu, S. Q. Zang, Multiple responsive CPL switches in an enantiomeric pair of perovskite confined in lanthanide MOFs. Adv. Mater. 34, 2109496 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Y. Ru, L. Sui, H. Song, X. Liu, Z. Tang, S. Q. Zang, B. Yang, S. Lu, Rational design of multicolor-emitting chiral carbonized polymer dots for full-color and white circularly polarized luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 14091–14099 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Y. Ru, B. Zhang, X. Yong, L. Sui, J. Yu, H. Song, S. Lu, Full-color circularly polarized luminescence of CsPbX3nanocrystals triggered by chiral carbon dots. Adv. Mater. 35, (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.X. H. Tang, H. Jiang, Y. Si, N. Rampal, W. Gong, C. Cheng, X. Kang, D. Fairen-Jimenez, Y. Cui, Y. Liu, Endohedral functionalization of chiral metal-organic cages for encapsulating achiral dyes to induce circularly polarized luminescence. Chem 7, 2771–2786 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 49.M. Sugimoto, X. L. Liu, S. Tsunega, E. Nakajima, S. Abe, T. Nakashima, T. Kawai, R. H. Jin, Circularly polarized luminescence from inorganic materials: Encapsulating guest lanthanide oxides in chiral silica hosts. Chem. A Eur. J. 24, 6519–6524 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.T. H. Zhao, J. Han, X. Jin, Y. Liu, M. Liu, P. Duan, Enhanced circularly polarized luminescence from reorganized chiral emitters on the skeleton of a zeolitic imidazolate framework. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 4978–4982 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.K. R. Krishnadas, L. Sementa, M. Medves, A. Fortunelli, M. Stener, A. Fürstenberg, G. Longhi, T. Bürgi, Chiral functionalization of an atomically precise noble metal cluster: Insights into the origin of chirality and photoluminescence. ACS Nano 14, 9687–9700 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.M. H. Zhou, Y. Sang, X. Jin, S. Chen, J. Guo, P. Duan, M. Liu, Steering nanohelix and upconverted circularly polarized luminescence by using completely achiral components. ACS Nano 15, 2753–2761 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.M. C. Xu, C. Ma, J. Zhou, Y. Liu, X. Wu, S. Luo, W. Li, H. Yu, Y. Wang, Z. Chen, J. Li, S. Liu, Assembling semiconductor quantum dots in hierarchical photonic cellulose nanocrystal films: Circularly polarized luminescent nanomaterials as optical coding labels. J. Mater. Chem. C 7, 13794–13802 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Y. Shi, Z. Zhou, X. Miao, Y. J. Liu, Q. Fan, K. Wang, D. Luo, X. W. Sun, Circularly polarized luminescence from semiconductor quantum rods templated by self-assembled cellulose nanocrystals. J. Mater. Chem. C 8, 1048–1053 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 55.S. Kang, G. M. Biesold, H. Lee, D. Bukharina, Z. Lin, V. V. Tsukruk, Dynamic chiro-optics of bio-inorganic nanomaterials via seamless co-assembly of semiconducting nanorods and polysaccharide nanocrystals. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2104596 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.R. Xiong, S. Yu, M. J. Smith, J. Zhou, M. Krecker, L. Zhang, D. Nepal, T. J. Bunning, V. V. Tsukruk, Self-assembly of emissive nanocellulose/quantum dot nanostructures for chiral fluorescent materials. ACS Nano 13, 9074–9081 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.M. C. Xu, X. Wu, Y. Yang, C. Ma, W. Li, H. Yu, Z. Chen, J. Li, K. Zhang, S. Liu, Designing hybrid chiral photonic films with circularly polarized room-temperature phosphorescence. ACS Nano 14, 11130–11139 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.W. Li, M. Xu, C. Ma, Y. Liu, J. Zhou, Z. Chen, Y. Wang, H. Yu, J. Li, S. Liu, Tunable upconverted circularly polarized luminescence in cellulose nanocrystal based chiral photonic films. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 11, 23512–23519 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.R. Kumar, K. K. Raina, Optical and electrical control of circularly polarised fluorescence in CdSe quantum dots dispersed polymer stabilised cholesteric liquid crystal shutter. Liq. Cryst. 43, 994–1001 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 60.C. T. Wang, K. Chen, P. Xu, F. Yeung, H. S. Kwok, G. Li, Fully chiral light emission from CsPbX3 perovskite nanocrystals enabled by cholesteric superstructure stacks. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1903155 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 61.L. J. Chen, C. Hao, J. Cai, C. Chen, W. Ma, C. Xu, L. Xu, H. Kuang, Chiral self-assembled film from semiconductor nanorods with ultra-strong circularly polarized luminescence. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26276–26280 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.X. K. Yang, J. Lv, J. Zhang, T. Shen, T. Xing, F. Qi, S. Ma, X. Gao, W. Zhang, Z. Tang, Tunable circularly polarized luminescence from inorganic chiral photonic crystals doped with quantum dots. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, 202201674 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S19

Tables S1 and S2

References