Abstract

Interactions between gut microbiome and host immune system are fundamental to maintaining the intestinal mucosal barrier and homeostasis. At the host-gut microbiome interface, cell wall-derived molecules from gut commensal bacteria have been reported to play a pivotal role in training and remodeling host immune responses. In this article, we review gut bacterial cell wall-derived molecules with characterized chemical structures, including peptidoglycan and lipid-related molecules that impact host health and disease processes via regulating innate and adaptive immunity. Also, we aim to discuss the structures, immune responses, and underlying mechanisms of these immunogenic molecules. Based on current advances, we propose cell wall-derived components as important sources of medicinal agents for the treatment of infection and immune diseases.

Keywords: gut commensal bacteria, peptidoglycan, lipid-related molecules, immune responses

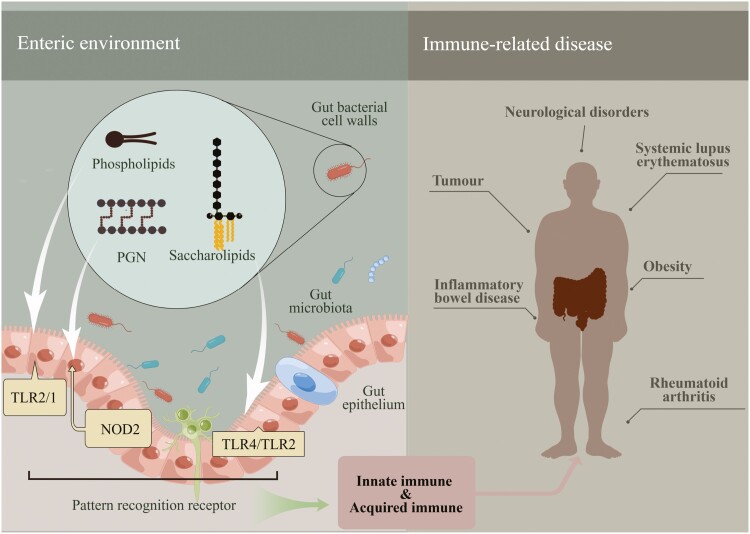

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

In the past decades, growing evidences have demonstrated that gut microbiota has profound influences on human health (Schroeder and Bäckhed, 2016; Krautkramer et al., 2021). The co-evolution of host and gut microbiome has led to a mutually beneficial consortium with a finely tuned immune system (Cebra, 1999). Gut microbiome and host immunity (especially gut mucosal immunity) interacts in a complex, dynamic, and environmentally dependent manner (Mallott and Amato, 2021). Alterations in gut microbiota have been identified in many immune-related diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (Yang and Cong, 2021; Jiang et al., 2022). It has been reported that the diversity of gut microbiome in IBD patients is decreased relative to the healthy subjects in the case cohort-based studies, with the phylum Firmicutes declining and Proteobacteria (especially Enterobacteriaceae) expanding (Jacobs et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2021). As to RA, the segmented filamentous bacteria was shown to trigger disease by inducing the differentiation and migration of intestinal T-follicle-assisted cells to the systemic lymphoid sites (Teng et al., 2016). On the other hand, the gut bacterium Parabacteroides distasonis was found to alleviate RA by suppressing T helper 17 (Th17) cells differentiation and promoting macrophage M2 polarization through bile acid metabolism (Sun et al., 2023). In SLE patient, the ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes in gut is significantly lower than that of healthy controls (Choi et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2021). In addition, the gut Lactobacillus have been reported to be associated with the remission of SLE (Zhang et al., 2014).

Gut microbiota is able to regulate intestinal innate and adaptive immune responses via immunorecognition receptors and immune cell populations [T cells, B cells, dendritic cells (DCs), and macrophages] (Alexander et al., 2014; Hou et al., 2022). The innate immune system which is the first line of gut defense against pathogenic infection maintains the intestinal homeostasis (Hoffmann et al., 1999). The pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) expressed in intestinal epithelial cells significantly affect the host innate immune responses by recruiting gut microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs). To date, PRRs including toll-like receptors (TLRs), C-type lectin receptors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors (NLRs), retinoic acid-inducible gene-like receptors, absent in melanoma 2 (AIM2)-like receptors (ALR), and dectin1/2 receptors have been identified (Nenci et al., 2007; Palm and Medzhitov, 2009; Nigro et al., 2014). In the adaptive immune, Th17 cells that are abundant in the intestinal lamina propria were demonstrated preventing invasions of pathogens by expressing the retinoic acid receptor (RAR)-related orphan receptor (ROR)γ transcription factor and producing cytokines interleukin (IL)-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 (Ivanov et al., 2006). These cytokines enable epithelial cells to generate antimicrobial peptides (AMPs), and thus enhancing the tight junctions (Ivanov et al., 2008; Weaver et al., 2013).

Interactions between gut microbiome and host largely depend on microbial metabolites which are involved in signal transduction, regulation of metabolism and immune, and development of nervous system (Aron-Wisnewsky et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021; Spindler et al., 2022; Chen et al., 2023). Notably, gut microbes-derived molecules that are constantly secreted or degraded in enteric cavity play critical roles in balancing the host immune response (Smith et al., 2013). Therefore, it is important to investigate the structural features of gut microbe-derived metabolites and their unique physiological activities. In this review, we summarize recent studies on gut bacterial cell wall-derived immunogenic molecules with characterized chemical structures, including peptidoglycan (PGN) and lipid-related molecules (Fig. 1) that shape innate and adaptive immune responses in the background of health and diseases.

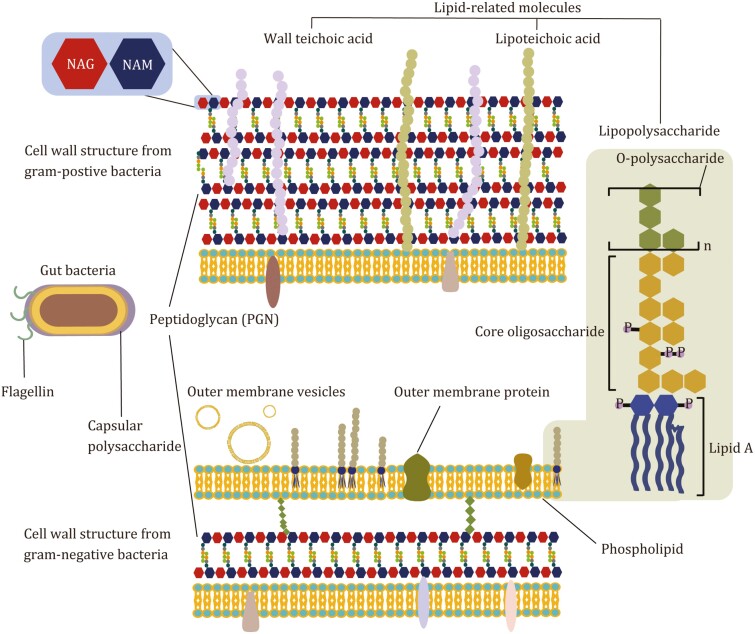

Figure 1.

Cell wall-associated components of gut Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.

Gut microbes-derived immune-regulating molecules

To date, a close and inner linkage between gut microbiota and immunity homeostasis has been identified. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying interactions between gut microbiome and host immunity are not fully clarified. It is essential to elucidate the bacteria-derived signaling molecules and reveal their functions in conferring immune responses. Intestinal epithelia cells can directly interact with the cell wall-associated molecules of gut bacteria, sensing, and transducing signaling pathways to host immunity. Gut bacterial cell wall components are an important source of these immunogenic molecules, including PGN, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), lipoteichoic acid (LTA), phospholipids, etc. The structure of cell wall-associated molecules plays vital roles in addressing the immune-regulatory functions. Here, the representative structures of cell wall-derived immunogenic molecules from gut microbiome are outlined in Fig. 2.

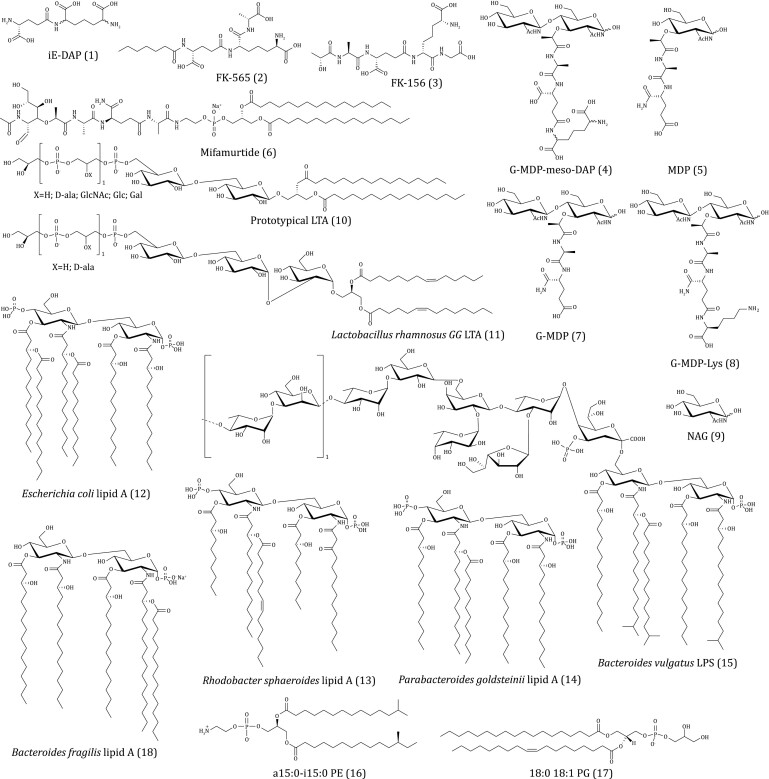

Figure 2.

Representative structures of cell wall-derived immunogenic molecules (compounds 1–18) from gut microbiome.

Production of PGN-derived immune-active molecules by gut microbes

Bacterial PGN that forms a multi-layer reticular macromolecular structure protects bacterial cells against the stress and maintains the tolerance of external environment (Egan et al., 2020). PGN is mainly composed of long polysaccharides chain with repetitive unit structure: N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetyl muramic acid (NAM) (Fig. 1). The NAM is connected with an oligopeptide chain (four to five amino acids) that is further cross-linked with another NAM moiety on the second polysaccharide chains (Vollmer et al., 2008a).

Bacterial PGNs are assembled by glycosyltransferase that polymerizes glycan chains and transpeptidase that catalyzes the peptide cross-linking (Typas et al., 2012). In addition, peptidoglycan hydrolases (PGHs) widely present in bacteria are responsible for the lysis of PGN (Vollmer et al., 2008b) (Fig. 3). The glycan chain of PGN contains two types of glycosidic bonds that are differentially sensitive to glycosidase activity. The β-1, 4-glycosidic bond between NAG and the adjacent NAM is hydrolyzed by N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase, while the lysozymes cleavage the β-1,4-glycosidic bond between NAM and NAG residues by adding water in the glycosidic bond to produce NAM (Callewaert and Michiels, 2010; Egan et al., 2020). Amidase specifically hydrolyzes the amide bond between the first amino acid of the oligopeptide chain and NAM (Charroux et al., 2018). The peptidases are divided into two categories depending on the site of action: carboxypeptidases that remove the C-terminal amino acid of the oligopeptide and endopeptidases that cleft inside the peptide cross-linking. Peptidases are named as DD-, LD-, or DL-peptidases according to the isomers of the two amino acids to be cleaved (Vollmer et al., 2008b). Genes encoding DD-carboxypeptidase are widely distributed in all phyla of gut microbes, while the genes encoding DL-endopeptidases (especially the secreted type) are specifically encoded by gut bacteria in Firmicutes (Erysipelotrichaceae, Lachnospiraceae, and Ruminococcaceae) (Zou et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2022). A large amount of PGN fragments are dynamically and constantly generated from cell walls of the commensal bacteria in gut (Adam et al., 1981; Dworkin, 2014). To determine the level of PGN fragments in gut, approaches using the fluorescence imaging, the PGN-specific labeling probes with modified side chains of d-amino acids, and the monoclonal antibody that targets the conserved minimal immune-stimulatory structures of PGN were successfully developed (Huang et al., 2019; Brown et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020c, Apostolos et al., 2022; Mondragón-Palomino et al., 2022). A recent study, a cell-based detection method using NOD1/2-transfected and nuclear factor kappa-B (NF-κB) luciferase-co-expressed HEK293T cells has been established. The intensity of fluorescence due to the activation of NOD1/2 pathway in the HEK293T cells corresponds to the level of the immune-active PGN molecules (Kim et al., 2019). In addition, the composition of PGN fragments can be studied in vitro by the paper chromatography, the thin layer chromatography, as well as the ultra-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric (UPLC-MS/MS) analysis (Ohya et al., 1993; Whitney et al., 2017). However, to further unveil the functions of PGN-related molecules in gut microbiota, new efficient analysis methods should be developed.

Figure 3.

The cross-linking peptidoglycan (PGN) molecule and the PGN hydrolases responsible for the lysis of PGN. NAG, N-acetylglucosamine; NAM, N-acetylmuramic acid; mDAP, meso-diaminopimelic acid.

Immunological functions of PGN-derived molecules

Previous studies have demonstrated that the soluble PGN-derived molecules from gut bacteria can act as immune-regulatory factors (Palm and Medzhitov, 2009). According to signaling pathways in immunity, the gut bacterial PGN-derived molecules are identified as activators of the NOD 1/2 receptors of cells. d-isoGlu-meso-diaminopimelic acid (iE-DAP, 1) from the PGNs of the gut commensal Escherichia coli and its chemical derivatives (Fig. 2) including heptanoyl-d-isoGlu-meso-DAP-d-Ala (FK-565, 2), d-lactoyl-l-Ala-d-isoGlu-meso-DAP-Gly (FK-156, 3), and an iE-DAP-derived tripeptide (NAG-NAM-L-Ala-d-isoGlu-meso-DAP, 4) have been confirmed as NOD1 agonists. Among these agonists, iE-DAP induces the secretion of IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α by activation of NOD1 signaling pathway (Chamaillard et al., 2003), while its chemical derivatives FK-156 and FK-565 promote IL-1 secretion (Ahmed and Turk, 1989). FK-565 can promote colorectal cancer development by triggering the NOD1 pathway in tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells (Maisonneuve et al., 2021). iE-DAP-derived tripeptide (4) induces the production of IL-8 in epithelial cells by activation of NOD1/NF-κB pathway (Girardin et al., 2003). Further studies indicate that the meso-DAP containing in the structure of iE-DAP is necessary for the activation of NOD1 (Agnihotri et al., 2011). In addition, the gut bacteria-derived NOD1 activators in plasma contribute to the progression of metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance through production of macrophages-derived chemokine ligand (CXCL) 1 (Cavallari et al., 2017; Chan et al., 2017).

The activation of NOD2 by muramyl dipeptide (MDP, 5) derived from gut bacterial PGN is involved in anti-inflammatory events. It has been verified that the d-isoGln at the end of the peptide in MDP is essential for its specific activation of NOD2 pathway (Griffin et al., 2021). In addition, the phosphorylation of NAG of MDP in vivo by NAG kinase of hosts is necessary for its stimulant activity (Caruso et al., 2014; Stafford et al., 2022). In clinics, the muramyl tripeptide phosphatidyl ethanolamine (mifamurtide, 6) which is a derivative of MDP, acts as an immune modulator in the treatment of infections and cancers (Dvorožňáková et al., 2008). The underlying mechanism of actions for mifamurtide involves the activation of NOD2, which benefit for the gut mucosal immune homeostasis. In recent studies, several new MDP-related molecules with immune modulatory activities have been identified from gut commensal bacteria Enterococcus faecium and Lactobacillus salivarius. The gut commensal E. faecium shows protection against pathogen infections and enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of anti-programmed death (PD)-L1 in the melanoma model (Pedicord et al., 2016; Rangan et al., 2016), which is further demonstrated to rely on the expression an endopeptidase (the secreted antigen A, SagA) that cleaves the peptide bond of PGN. Furthermore, the activation of the MDP-regulated NOD2 pathway in the innate immune response is confirmed. The high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometric (HPLC-MS/MS) analysis indicates the presence of NAG-NAM-l-Ala-d-isoGln (G-MDP, 7) in the PGN fragments of gut E. faecium (Kim et al., 2019). Structural analysis of SagA revealed a NlpC/p60 family peptidase domain, in which the cysteine (C) 443A locus cleaves peptide bonds of d-isoGln and l-Lys to produce immunologically active PGN fragments. In the study of L. salivarius, a MDP analogue NAG-NAM-l-Ala-d-isoGln-l-Lys (G-MDP-Lys, 8) is isolated and demonstrated to alleviate the experimental colitis via activation of the NOD2-mediated signaling (Fernandez et al., 2011). Besides the immune-regulating function, MDP-activated NOD2 signaling is also implicated in the regulation of gut-brain crosstalk, development, and metabolism balance. It has been revealed that the NOD2-expressing GABAergic neurons are involved in the control of body temperature and appetite through sensing MDP from gut microbes (Gabanyi et al., 2022). PGN-derived molecules (MDP and its derivatives) from Lactiplantibacillus plantarumWJL activate intestinal epithelial NOD2 receptor to promote insulin-like growth factor 1 production, contributing to the development of juvenile mice (Schwarzer et al., 2023). MDP and mifamurtide (6) mitigate obesity and insulin resistance via suppressing the interferon regulatory factor 4 (IRF4) due to activation of NOD2, whereas iE-DAP (1) and its derivatives exhibits the opposite effect (Cavallari et al., 2017).

Interestingly, new binding targets have been found for PGN and its fragments in recent works. On Caenorhabditis elegans, the muropeptide from E. coli in gut binds to and acts as an agonist of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) synthase, playing beneficial effects on mitochondrial homeostasis, development, and food behavior in animals (Tian and Han, 2022). The intact PGN (not fragments) from the gut Lactobacillus interacts with the extracellular receptor TLR2 to inhibit IL-12 production in macrophages (Shida et al., 2009). In another work, hexokinase that specifically binds with the PGN-derived NAG (9) can increase NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages, suggesting it as a new innate immune receptor for recognizing (Wolf et al., 2016).

Early studies indicate rich endopeptidases with NlpC/p60 family peptidase-like domain in genomes of the human gut commensal bacteria (Zou et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2022). The HPLC-MS/MS analysis on muropeptides from PGN of gut commensal bacteria also reveals a variety of uncharacterized PGN-derived molecules. Based on these evidences, it can be deduced that the diverse PGHs encoded by gut commensal bacteria could produce a wide variety of PGN fragments. Above all, the structures and biological functions of these PGN-derived molecules need to be further explored.

Immune functions of saccharolipids and phospholipids derived from bacterial cell wall

Gut bacterial cell wall-derived lipid-related molecules include saccharolipids and phospholipids. Saccharolipids from the cell walls of gut microbes include teichoic acid (TA) from Gram-positive bacteria and LPS from Gram-negative bacteria (Shiraishi et al., 2016) (Figs. 1 and 2). The wall-teichoic acid (WTA) not only plays a leading role in the attachment and colonization of commensals, but also contributes in part to the immune regulation of host (Kurokawa et al., 2013). The WAT derived from the intact cell wall of the gut probiotic L. plantarum stimulates IL-12 secretion from macrophages (Kojima et al., 2022). The LTA (10) from probiotics have shown beneficial effects on regulation of immune responses. In early works, LTA from the gut probiotic L. rhamnosus GG (LGGLTA, 11) counteracted ultraviolet (UV) B radiation-mediated immunosuppression and blocked tumor growth (Friedrich et al., 2019), which was ascribed to the increased migration of mesenchymal stem cell onto intestinal epithelial cells through TLR2-chemokine ligand (CXCL) 12 signaling pathway (Riehl et al., 2019); LTA of the probiotic Apilactobacillus kosoi stimulates the secretion of immune globulin A (IgA), neutralizing of toxins and pathogens (Matsuzaki et al., 2022); LTA of the gut commensal Enterococcus faecalis induces autophagy of macrophage cells via inhibiting phosphoinositid-3-kinase (PI3K)/protein kinase B (Akt)/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathway (Lin et al., 2018), and increases the inflammatory response through the production of TNF-α and IL-6 via p38 and extracellular regulated protein kinases (ERK1/2) signaling pathways in bone marrow-derived macrophages (Wang et al., 2019); LTA from the gut commensal Lactobacillus paracasei D3-5 effectively elevates the expression of mucin in mice by regulating TLR-2/p38-MAPK/NF-κB pathway, alleviating the age-related leaky gut and inflammation in mice (Wang et al., 2020b). TLR2 has been verified as the natural receptor of LTA, and activation of TLR2 signaling pathway facilitates secretion of mucin 2 on gut epithelia cells. Currently, only a few of gut bacteria-associated WTA and LTA have been studied for their effects on host. The functions of WTA or LTA from gut commensals with high abundance in the gut microbiota deserve much more attention and researches.

LPS released into circulation are known as potent inflammation inducers activating TLR4 or inflammatory caspase (caspase-4/5/11)-mediated signaling pathway (Rathinam et al., 2019; de Vos et al., 2022). In some recent works, LPS from gut commensals have been found to induce beneficial immune response in host. The suprarenal and celiac ganglia (SrG-CG) neurons can sense LPS from E. coli (Serotype O55:B5) to up-regulate the expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) that reduce the splenic immune response and inhibit LPS-mediated inflammation (Yu et al., 2022). A penta-acylated LPS (lipid A moiety, 13) from the gut Rhodobacter sphaeroides corrects dysglycemia caused by hexa-acylated LPS (lipid A moiety, 12) from E. coli in lean mice and improves insulin sensitivity in obese mice (Anhê et al., 2021). Another LPS containing five acyl chains from the gut commensal Parabacteroides goldsteinii (lipid A moiety, 14) was deduced to alleviate chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by inhibiting the TLR4 signaling pathway (Lai et al., 2022). The LPS derived from the gut Bacteroides vulgatus (BvLPS, 15) was reported to suppress inflammatory responses in IBD mice by inducing CD11c+ low-reactive semi-maturation of DCs (Steimle et al., 2019). As to its immunological properties, BvLPS induces a synergistic activation of the myeloid differentiation protein-2 (MD-2)/TLR4 and TLR-2-mediated pathway on human macrophages and DCs. The structure of BvLPS is established with five acyl chains, mono-phosphorylated lipid A, and a galactofuranose-containing oligosaccharide chain (Di Lorenzo et al., 2020). Furthermore, the underacylated LPS containing in members of gut order Bacteroidales is found to silence TLR4 signaling (d’Hennezel et al., 2017). Based on these findings, we deduce that the subtle structural variations in LPS from gut commensals lead to different immune-modulating activities. Gut microbes show great potential in biosynthesizing LPS with diverse structure and vital functions in modulating immune response. Much efforts should be made to study the chemical characteristics and bioactivities of these gut microbial LPS in the field of immunity, inflammation, and metabolism.

Phospholipids on bacterial membranes can serve as lipid antigens to regulate innate and adaptive immune response. Recently, the diacyl phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) with two branched chains (anteiso15:0-isoi15:0 PE, 16) was characterized from the gut commensal Akkermansia muciniphila and confirmed to agonize the TLR2/1 heterodimer signaling pathway inducing production of specific proinflammatory cytokines (Bae et al., 2022). It was also found that low doses of a15:0-i15:0 PE “passivate” the activation threshold of DCs and suppress the response to the subsequent LPS immune stimulation (Bae et al., 2022). The CD1 positive antigen-presenting cells have been demonstrated to recognize endogenous and microbial phospholipids and activate specific T cell populations (Van Rhijn et al., 2016; Shahine et al., 2019). In one study, the bacterial membrane phosphatidylglycerol (PG, 17) from Staphylococcus aureus in the gut microbiota and its chemically modified derivative (lysyl-PG) with a lysine head were verified to stimulate tetramer+ CD4+ T cell lines to secrete inflammatory cytokines of type 2 helper T cells (Monnot et al., 2023). In another work, the PE and phosphatidylcholine (PC) from the gut Desulfovibrio piger were found to promote gamma-delta T cell activation in the intestinal cells through CD1d, which further induced IL-17A production and exacerbated hypoxic-induced intestinal injury (Li et al., 2022). In some Gram-negative bacteria, the phospholipid-bound capsules polysaccharides (CPS) are present on the outer membranes (Willis et al., 2013). In the genome of the gut Bacteroides fragile, at least eight different CPS biosynthetic gene clusters are annotated, of which polysaccharide A (PSA) is most expressed one (Chatzidaki-Livanis et al., 2010). The PSA of B. fragilis binds TLR-2/1 heterodimer and Dectin-1 receptors to trigger PI3K/Akt signaling pathway on macrophages and DCs (Erturk-Hasdemir et al., 2019), and shows anti-inflammatory effect via secretion of IL-10 (Ramakrishna et al., 2019). Structure-activity relationship analysis indicates that the lipid of PSA (18) acts as an agonist for TLR-2/1 heterodimers, while the carbohydrate moieties of PSA bind to Dectin-1 (Erturk-Hasdemir et al., 2019). In the future work, the structural features of gut bacterial PE and PC with important immune-modulating activities should be examined to explore structure-activity relationship.

Lipid molecules with different chemical structures from gut bacteria can act as ligands for TLR receptors to modulate downstream immune responses (e.g., LPS for TLR4; LTA for TLR2; PE for TLR2/1). The binding site on the receptor and the recognition pattern between cell wall-derived lipid molecules and the TLR receptors need further investigation, which will enhance our understanding of mechanisms underlying the immune response. In addition, comparing to rich species diversity of gut bacteria, only a small number of lipid-related immunogenic molecules (Saccharolipids and phospholipids) from a few of gut bacteria have been studied, and many issues should be addressed before we can fully understand how lipid-related molecules in gut communicate with the immune system. The first issue is to establish the delicacy lipidomic profiles from all culturable gut microbes and characterize lipid-related immunogenic molecules by liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometric (LC-MS) or liquid chromatography-nuclear magnetic resonance (LC-NMR) analysis with the aid of artificial intelligence algorithms. The second issue is that currently reported immune-modulating effects of gut microbes-derived lipids are mainly obtained by in vitro studies. Taking the complex immune microenvironments and complicated immune regulations into consideration, the efficacies and the related immune-modulating mechanism of gut microbes-derived lipids needs to be further investigated in animal models for different diseases. Importantly, deep researches on lipid-related immunogenic molecules from gut bacterial will provide new strategy for treating infections and immune diseases, as exemplified by the immunoadjuvants developed from LPS (Di Lorenzo et al., 2019).

Conclusions and perspectives

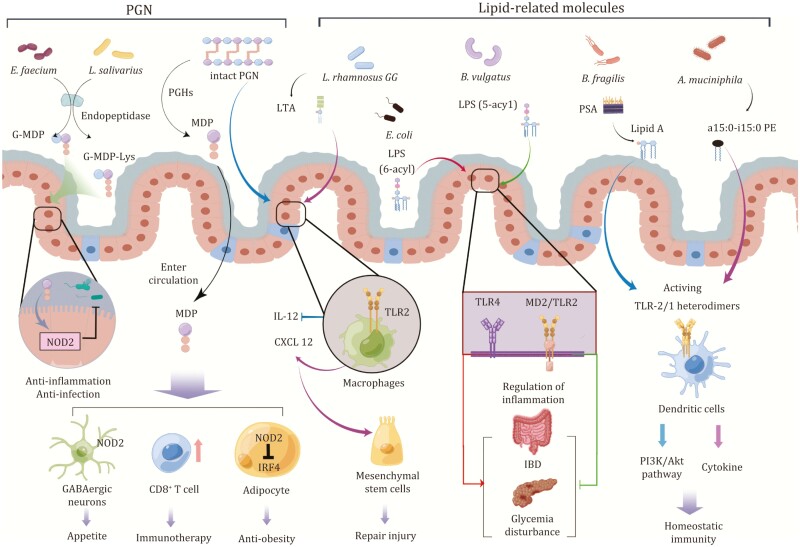

The interaction between the gut microbiome and host immune system has been extensively investigated in the past decades, accumulating much knowledge and insights underlying this important mutual relation (Fig. 4). In this paper, we review how gut microbial cell wall-derived immunogenic molecules including PGN and lipid-related molecules shape innate and adaptive immune responses during disease process. The PGN or PGN derivatives regulate host immune and inflammatory response via binding the intracellular innate immune receptors NOD1/2. The lipids of gut microbes can modulate the innate and adaptive immune response through regulation of the extracellular innate immune receptors-mediated pathway or specific T cell population. However, comparing to the diversity and complexity of gut microbiome, only a small number of gut commensals including A. muciniphila, A. kosoi, B. fragilis, B. vulgatus, P. goldsteinii, E. coli, E. faecium, D. piger, L. paracasei, L. rhamnosus, L. casei, L. plantarum, L. salivarius, N. meningitides, R. sphaeroides, and S. aureus have been explored for immune-active substances (Table 1). Besides immune-modulating molecules reviewed in this work, the cell wall-derived outer membrane (OM) proteins and outer membrane vesicles (OMV) also play regulatory roles in the cross-talking between gut microbiome and host immune system. For instance, The Amuc 1100, an OM protein of A. muciniphila, is demonstrated to improve gut barrier function and alleviate metabolic diseases, which could be related to its activation of the innate immune TLR2 signaling (Plovier et al., 2017). Amuc 1100 also improves colitis-associated colorectal cancer by reducing colorectal infiltrating macrophages and cytotoxic CD8+ T cells (Wang et al., 2020a). In a gut-brain axis study, another OM protein derived from Escherichia coli, OmpF/A, inhibits innate immune signaling through neuropeptides to manipulate digestion in the C. elegans (Geng et al., 2022). The OMV is a lipid-based delivery system for small molecules of the microbiome from bacteria to host cells. There is evidence that the lipids or encapsulated metabolites carried by OMV may contribute to many immunomodulatory properties. The OMV from gut Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron was reported to balance the regulatory DCs responses by stimulating IL-10 in the colonic DCs and IL-6 in the peripheral blood-derived DCs of healthy individuals (Durant et al., 2020). Much attentions and efforts should be paid to immunogenic molecules in the gut microbiota, with emphasis on their structures, immune-regulatory efficacy, and targeting signaling pathways. In addition, there are still large challenges to effectively detect these molecules in gut microbiota and accurately elucidate their structures. Further exploration of these gut microbes-derived immunogenic molecules will promote our understanding of new immune-regulatory mechanisms, which in turn sheds new light on developing clinical therapies for diseases.

Figure 4.

Targets and signaling pathway modulated by gut microbiome-derived immunogenic molecules. The production of G-MDP-Lys and G-MDP by L. salivarius and E. faecium depends on its endopeptidase activity. Both derivatives show anti-inflammatory or anti-infective activity in the intestinal epithelium by triggering NOD2. MDP enters the circulation, contributing to activation of the NOD2 pathway, which regulates appetite via GABAergic neurons; enhances the immunotherapy effect of tumor via CD8+ T cell expansion; reduces weight by inhibiting IRF4. Intact PGN could inhibit IL-12 production by acting on TLR2. For lipid-related molecules, LTA from LGG also stimulates CXCL12 production by binding to TLR2 of macrophages, thereby promoting mesenchymal stem cells to migrate to epithelium for injury repairment. The hexacylated LPS from E. coli is a potent agonist of TLR4, promoting colitis and metabolic disorders, while pentacylated LPS from B. vulgatus have anti-inflammatory activity dependent on MD2/TLR2 and TLR4. For lipids, lipid A from the PSA of B. fragilis triggers PI3K/Akt signaling via a heterodimer of TLR2/1, restoring immune homeostasis. The phospholipid antigen a15:0-i15:0 PE from A. muciniphila binds to the heterodimer of TLR2/1 to regulate the immune response of DCs. Figure 4 is drawn with Figdraw.

Table 1.

Immunogenic compounds derived from PGNs and lipids of gut microbes and their mechanisms of actions.

| Cell wall-derived compounds | Origin | Mechanisms | Models investigated |

|---|---|---|---|

| iE-DAP | Synthesis | NOD1↑ | Macrophages (Chamaillard et al., 2003) |

| FK-156 | Synthesis | IL-1↑ | Macrophages (Ahmed and Turk, 1989) |

| FK-565 | Synthesis | NOD1↑ | CRC mice (Maisonneuve et al., 2021) |

| G-MDP-meso-DAP | N. meningitidis | NOD1↑ | NF-κB reporter HEK293T cells (Girardin et al., 2003) |

| Mifamurtide | Synthesis | NOD2↑ | Clinical study (Dvorožňáková et al., 2008) |

| G-MDP | E. faecium | NOD2↑ | Pathogen-infected mice (Kim et al., 2019) |

| G-MDP-Lys | L. salivarius | NOD2↑ | IBD mice (Fernandez et al., 2011) |

| MDP | Synthesis | NOD2↑ | Older mice (Gabanyi et al., 2022) |

| MDP | Synthesis | NOD2↑/IRF4↓ | Obese mice (Cavallari et al., 2017) |

| Intact PGN | Lactobacillus spp. | TLR2↑ | Peritoneal macrophages (Shida et al., 2009) |

| Muropeptides | E. coli | ATP synthase↑ | Caenorhabditis elegans (Tian and Han, 2022) |

| NAG | S. aureus | Hexokinase↑ | BMDMs (Wolf et al., 2016) |

| WTA | L. plantarum | IL-12↑ | BMDMs (Kojima et al., 2022) |

| LTA | L. rhamnosus GG | TLR2↑ | Radiation-injury (Riehl et al., 2019) |

| LTA | L. paracasei D3-5 | TLR2↑ | Obese mice (Wang et al., 2020b) |

| LTA | A. kosoi | lgA↑ | Murine Peyer’s patch cells (Matsuzaki et al., 2022) |

| LTA | E. faecalis | PI3K/Akt/mTOR↓ | RAW264.7 cell (Lin et al., 2018) |

| LTA | E. faecalis | p38/ERK1/2↑ | BMDMs (Wang et al., 2019) |

| LPS | E. coli | TLR4↑ | IBD mice (Heimesaat et al., 2007) |

| LPS | P. goldsteinii | TLR4↓ | COPD mice (Lai et al., 2022) |

| LPS | B. vulgatus | MD-2/TLR4↑ | IBD mice (Steimle et al., 2019; Di Lorenzo et al., 2020) |

| PSA | B. fragilis | TLR2/1 and Dectin-1↑ | Macrophages (Erturk-Hasdemir et al., 2019) |

| a15:0-i15:0 PE | A. muciniphila | TLR2/1↑ | DCs (Bae et al., 2022) |

| PG | S. aureus | CD4 + T cell↑ | Atopic dermatitis (Monnot et al., 2023) |

| PE and PC | D. piger | γδ T cells↑ | Hypoxia-injury (Li et al., 2022) |

The importance of gut microbiome in remodeling immune responses has been widely recognized, only a small number of gut bacteria-derived immunogenic molecules have been studied. With the development of cultureomics methods and the optimization of anaerobic fermentation, more immunogenic molecules of gut commensals can be characterized. In addition, flow cytometry-click chemistry coupling methods could also enable us to identify gut bacterial community with specific cell wall-derived molecules (Tei and Baskin, 2022). Moreover, advances in bioinformatics analysis and genome manipulation realize the design and generation of live biotherapeutic products by expressing gut microbiome-derived immunogenic molecules in the probiotic strains including E. coli Nissle 1917 and L. plantarum. To increase our insights into the gut microbiome-host interaction, gene deletion and hetero-expression methods should be expanded to other important taxa including Lactobacillus, Akkermansia, and Bifidobacteria in human gut microbiome. Taken together, with more key functions of gut microbial cell wall-derived molecules being demonstrated, their biosynthesis, metabolisms, bioactivities, and mechanism of actions should be taken into consideration in studies of gut microbiota–host interactions.

Acknowledgements

The work was financially supported by a grant from National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFA1304200).

Glossary

Abbreviations

- Akt

protein kinase B

- AMPs

antimicrobial peptides

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- CD

cluster of differentiation

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPS

capsules polysaccharides

- CXCL

chemokine ligand

- DCs

dendritic cells

- ERK

extracellular regulated protein kinases

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- G-MDP

NAG-NAM-L-Ala-D-isoGln

- G-MDP-Lys

NAG-NAM-L-Ala-d-isoGln-l-Lys

- HPLC-MS/MS

high-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- iE-DAP

d-isoGlu-meso-DAP

- IgA

immune globulin A

- IL

interleukin

- IRF

interferon regulatory factor 4

- LC-MS

liquid chromatograph-mass spectrometry

- LC-NMR

liquid chromatography-nuclear magnetic resonance

- LGG

Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- LTA

lipoteichoic acid

- MAMPs

microbe-associated molecular patterns

- MD-2

myeloid differentiation protein-2

- MDP

muramyl dipeptide

- meso-DAP

meso-diaminopimelic acid

- mTOR

mammalian target of rapamycin

- NAG

N-acetylglucosamine

- NAM

N-acetylmuramic acid

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa-B

- NLRs

NOD-like receptors

- NOD

nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain

- NPY

neuropeptide Y

- OM

outer membrane

- OMV

outer membrane vesicles

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PD-L1

programmed death-L1

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PG

phosphatidylglycerol

- PGHs

peptidoglycan hydrolases

- PGN

peptidoglycan

- PI3K

phosphoinositid-3-kinase

- PRRs

pattern recognition receptors

- PSA

polysaccharide A

- RA

rheumatoid arthritis

- RORγt

RAR-related orphan receptor γ transcription factor

- SagA

secreted antigen A

- SLE

systemic lupus erythematosus

- TA

teichoic acid

- Th17

T helper 17

- TLRs

toll-like receptors

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- UPLC-MS/MS

ultra-performance liquid chromatography with tandem mass spectrometry

- UV

ultraviolet

- WTA

wall-teichoic acid

Contributor Information

Ruopeng Yin, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Tao Wang, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Huanqin Dai, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Junjie Han, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Jingzu Sun, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Ningning Liu, CAS Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Microbiology and Immunology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China.

Wang Dong, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Jin Zhong, State Key Laboratory of Microbial Resources, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100101 Beijing, China.

Hongwei Liu, State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China; Savaid Medical School, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China.

Conflict of interest

R.Y., T.W., H.D., J.H., J.S., N.L., W.D., J.Z., and H.L. declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Adam A, Petit J-F, Lefrancier Pet al. Muramyl peptides: chemical structure, biological activity and mechanism of action. Mol Cell Biochem 1981;41:27–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnihotri G, Ukani R, Malladi SSet al. Structure−activity relationships in nucleotide oligomerization domain 1 (Nod1) agonistic γ-glutamyldiaminopimelic acid derivatives. J Med Chem 2011;54:1490–1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed K, Turk JL, Turk John L.. Effect of anticancer agents neothramycin, aclacinomycin, FK-565 and FK-156 on the release of interleukin-2 and interleukin-1 in vitro. Cancer Immunol Immunother 1989;28:87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander KL, Targan SR, Elson CO.. Microbiota activation and regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev 2014;260:206–220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anhê FF, Barra NG, Cavallari JFet al. Metabolic endotoxemia is dictated by the type of lipopolysaccharide. Cell Rep 2021;36:109691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolos AJ, Chordia MD, Kolli SHet al. Real-time non-invasive fluorescence imaging of gut commensal bacteria to detect dynamic changes in the microbiome of live mice. Cell Chem Biol 2022;29:1721–1728.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron-Wisnewsky J, Warmbrunn MV, Nieuwdorp Met al. Metabolism and metabolic disorders and the microbiome: the intestinal microbiota associated with obesity, lipid metabolism, and metabolic health—pathophysiology and therapeutic strategies. Gastroenterology 2021;160:573–599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bae M, Cassilly CD, Liu Xet al. Akkermansia muciniphila phospholipid induces homeostatic immune responses. Nature 2022;608:168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown AR, Gordon RA, Hyland SNet al. Chemical biology tools for examining the bacterial cell wall. Cell Chem Biol 2020;27:1052–1062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callewaert L, Michiels CW.. Lysozymes in the animal kingdom. J Biosci 2010;35:127–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caruso R, Warner N, Inohara Net al. NOD1 and NOD2: signaling, host defense, and inflammatory disease. Immunity 2014;41:898–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavallari JF, Fullerton MD, Duggan BMet al. Muramyl dipeptide-based postbiotics mitigate obesity-induced insulin resistance via IRF4. Cell Metab 2017;25:1063–1074.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cebra JJ. Influences of microbiota on intestinal immune system development. Am J Clin Nutr 1999;69:1046S1046s–1046S1051S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamaillard M, Hashimoto M, Horie Yet al. An essential role for NOD1 in host recognition of bacterial peptidoglycan containing diaminopimelic acid. Nat Immunol 2003;4:702–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KL, Tam TH, Boroumand Pet al. Circulating NOD1 activators and hematopoietic NOD1 contribute to metabolic inflammation and insulin resistance. Cell Rep 2017;18:2415–2426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charroux B, Capo F, Kurz CLet al. Cytosolic and secreted peptidoglycan-degrading enzymes in drosophila respectively control local and systemic immune responses to microbiota. Cell Host Microbe 2018;23: 215–228.e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzidaki-Livanis M, Weinacht KG, Comstock LE.. Trans locus inhibitors limit concomitant polysaccharide synthesis in the human gut symbiont Bacteroides fragilis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010;107:11976–11980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Xiao Y, Li Det al. New insights into the mechanisms of high-fat diet mediated gut microbiota in chronic diseases. iMeta 2023;2:e69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S-C, Brown J, Gong Met al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis and altered tryptophan catabolism contribute to autoimmunity in lupus-susceptible mice. Sci Transl Med 2020;12:eaax2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- d’Hennezel E, Abubucker S, Murphy LOet al. Total lipopolysaccharide from the human gut microbiome silences toll-like receptor signaling. mSystems 2017;2:e00046–e00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo F, De Castro C, Silipo Aet al. Lipopolysaccharide structures of Gram-negative populations in the gut microbiota and effects on host interactions. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2019;43:257–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lorenzo F, Pither MD, Martufi Met al. Pairing Bacteroides vulgatus LPS structure with its immunomodulatory effects on human cellular models. ACS Cent Sci 2020;6:1602–1616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant L, Stentz R, Noble Aet al. Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron-derived outer membrane vesicles promote regulatory dendritic cell responses in health but not in inflammatory bowel disease. Microbiome 2020;8:88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorožňáková E, Porubcová J, Šnábel Vet al. Imunomodulative effect of liposomized muramyltripeptide phosphatidylethanolamine (L-MTP-PE) on mice with alveolar echinococcosis and treated with albendazole. Parasitol Res 2008;103:919–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin J. The medium is the message: interspecies and interkingdom signaling by peptidoglycan and related bacterial glycans. Annu Rev Microbiol 2014;68:137–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egan AJF, Errington J, Vollmer W.. Regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis and remodelling. Nat Rev Microbiol 2020;18:446–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erturk-Hasdemir D, Oh SF, Okan NAet al. Symbionts exploit complex signaling to educate the immune system. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2019;116:26157–26166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez EM, Valenti V, Rockel Cet al. Anti-inflammatory capacity of selected Lactobacilli in experimental colitis is driven by NOD2-mediated recognition of a specific peptidoglycan-derived muropeptide. Gut 2011;60:1050–1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich AD, Campo VE, Cela EMet al. Oral administration of lipoteichoic acid from Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG overcomes UVB-induced immunosuppression and impairs skin tumor growth in mice. Eur J Immunol 2019;49:2095–2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabanyi I, Lepousez G, Wheeler Ret al. Bacterial sensing via neuronal Nod2 regulates appetite and body temperature. Science 2022;376:eabj3986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao J, Zhao X, Hu Set al. Gut microbial DL-endopeptidase alleviates Crohn’s disease via the NOD2 pathway. Cell Host Microbe 2022;30:1435–1449.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geng S, Li Q, Zhou Xet al. Gut commensal E. coli outer membrane proteins activate the host food digestive system through neural-immune communication. Cell Host Microbe 2022;30:1401–1416.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girardin SE, Boneca IG, Carneiro LAMet al. Nod1 detects a unique muropeptide from Gram-negative bacterial peptidoglycan. Science 2003;300:1584–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin ME, Espinosa J, Becker JLet al. Enterococcus peptidoglycan remodeling promotes checkpoint inhibitor cancer immunotherapy. Science 2021;373:1040–1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimesaat MM, Fischer A, Jahn H-Ket al. Exacerbation of murine ileitis by Toll-like receptor 4 mediated sensing of lipopolysaccharide from commensal Escherichia coli. Gut 2007;56:941–948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA, Kafatos FC, Janeway CAet al. Phylogenetic perspectives in innate immunity. Science 1999;284:1313–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou K, Wu Z-X, Chen X-Yet al. Microbiota in health and diseases. Sig Transduct Target Ther 2022;7:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z, Wang J, Xu Xet al. Antibody neutralization of microbiota-derived circulating peptidoglycan dampens inflammation and ameliorates autoimmunity. Nat Microbiol 2019;4:766–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov II, McKenzie BS, Zhou Let al. The orphan nuclear receptor RORγt directs the differentiation program of proinflammatory IL-17+ T helper cells. Cell 2006;126:1121–1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanov II, Rosa de Frutos L, Manel Net al. Specific microbiota direct the differentiation of IL-17-producing T-helper cells in the mucosa of the small intestine. Cell Host Microbe 2008;4:337–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs JP, Goudarzi M, Singh Net al. A disease-associated microbial and metabolomics state in relatives of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease patients. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol 2016;2:750–766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang S, Chen D, Ma Cet al. Establishing a novel inflammatory bowel disease prediction model based on gene markers identified from single nucleotide variants of the intestinal microbiota. iMeta 2022;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim B, Wang Y-C, Hespen CWet al. Enterococcus faecium secreted antigen A generates muropeptides to enhance host immunity and limit bacterial pathogenesis. eLife 2019;8:e45343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima N, Kojima S, Hosokawa Set al. Wall teichoic acid-dependent phagocytosis of intact cell walls of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum elicits IL-12 secretion from macrophages. Front Microbiol 2022;13:986396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krautkramer KA, Fan J, Bäckhed F.. Gut microbial metabolites as multi-kingdom intermediates. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurokawa K, Jung D-J, An J-Het al. Glycoepitopes of Staphylococcal wall teichoic acid govern complement-mediated opsonophagocytosis via human serum antibody and mannose-binding lectin. J Biol Chem 2013;288:30956–30968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai H-C, Lin T-L, Chen T-Wet al. Gut microbiota modulates COPD pathogenesis: role of anti-inflammatory Parabacteroides goldsteinii lipopolysaccharide. Gut 2022;71:309–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Wang Y, Shi Fet al. Phospholipid metabolites of the gut microbiota promote hypoxia-induced intestinal injury via CD1d-dependent γδ T cells. Gut Microbes 2022;14:2096994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin D, Gao Y, Zhao Let al. Enterococcus faecalis lipoteichoic acid regulates macrophages autophagy via PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2018;498:1028–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Zhao W, Lan Pet al. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel diseases: from pathogenesis to therapy. Protein Cell 2021;12:331–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonneuve C, Tsang DKL, Foerster EGet al. Nod1 promotes colorectal carcinogenesis by regulating the immunosuppressive functions of tumor-infiltrating myeloid cells. Cell Rep 2021;34:108677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallott EK, Amato KR.. Host specificity of the gut microbiome. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021;19:639–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzaki C, Shiraishi T, Chiou T-Yet al. Role of lipoteichoic acid from the genus Apilactobacillus in inducing a strong IgA response. Appl Environ Microbiol 2022;88:e00190–e00122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mondragón-Palomino O, Poceviciute R, Lignell Aet al. Three-dimensional imaging for the quantification of spatial patterns in microbiota of the intestinal mucosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2022;119:e2118483119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnot GC, Wegrecki M, Cheng T-Yet al. Staphylococcal phosphatidylglycerol antigens activate human T cells via CD1a. Nat Immunol 2023;24:110–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert Aet al. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 2007;446:557–561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nigro G, Rossi R, Commere P-Het al. The cytosolic bacterial peptidoglycan sensor Nod2 affords stem cell protection and links microbes to gut epithelial regeneration. Cell Host Microbe 2014;15:792–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohya Y, Nishimoto T, Ouchi T.. Design of d-glucose analogue of MDP/CM-curdlan conjugate and its immunological enhancement activity. Carbohydr Polym 1993;20:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- Palm NW, Medzhitov R.. Pattern recognition receptors and control of adaptive immunity. Immunol Rev 2009;227:221–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Q, Guo F, Huang Yet al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in systemic lupus erythematosus: novel insights into mechanisms and promising therapeutic strategies. Front Immunol 2021;12:799788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedicord VA, Lockhart AAK, Rangan KJet al. Exploiting a host-commensal interaction to promote intestinal barrier function and enteric pathogen tolerance. Sci Immunol 2016;1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plovier H, Everard A, Druart Cet al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurized bacterium improves metabolism in obese and diabetic mice. Nat Med 2017;23:107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishna C, Kujawski M, Chu Het al. Bacteroides fragilis polysaccharide A induces IL-10 secreting B and T cells that prevent viral encephalitis. Nat Commun 2019;10:2153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan KJ, Pedicord VA, Wang Y-Cet al. A secreted bacterial peptidoglycan hydrolase enhances tolerance to enteric pathogens. Science 2016;353:1434–1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathinam VAK, Zhao Y, Shao F.. Innate immunity to intracellular LPS. Nat Immunol 2019;20:527–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehl TE, Alvarado D, Ee Xet al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG protects the intestinal epithelium from radiation injury through release of lipoteichoic acid, macrophage activation and the migration of mesenchymal stem cells. Gut 2019;68:1003–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeder BO, Bäckhed F.. Signals from the gut microbiota to distant organs in physiology and disease. Nat Med 2016;22:1079–1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer M, Gautam UK, Makki Ket al. Microbe-mediated intestinal NOD2 stimulation improves linear growth of undernourished infant mice. Science 2023;379:826–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahine A, Reinink P, Reijneveld JFet al. A T-cell receptor escape channel allows broad T-cell response to CD1b and membrane phospholipids. Nat Commun 2019;10:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shida K, Kiyoshima-Shibata J, Kaji Ret al. Peptidoglycan from Lactobacilli inhibits interleukin-12 production by macrophages induced by Lactobacillus casei through Toll-like receptor 2-dependent and independent mechanisms. Immunology 2009;128:e858–e869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi T, Yokota S, Fukiya Set al. Structural diversity and biological significance of lipoteichoic acid in Gram-positive bacteria: focusing on beneficial probiotic lactic acid bacteria. Biosci Microbiota Food Health 2016;35:147–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, PM, Howitt, MR, Panikov, Net al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic T reg cell homeostasis. Science 2013;341:569–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spindler MP, Siu S, Mogno Iet al. Human gut microbiota stimulate defined innate immune responses that vary from phylum to strain. Cell Host Microbe 2022;30:1481–1498.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford CA, Gassauer A-M, de Oliveira Mann CCet al. Phosphorylation of muramyl peptides by NAGK is required for NOD2 activation. Nature 2022;609:590–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steimle A, Michaelis L, Di Lorenzo Fet al. Weak agonistic LPS restores intestinal immune homeostasis. Mol Ther 2019;27:1974–1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun D, Bai R, Zhou Wet al. Angiogenin maintains gut microbe homeostasis by balancing α-Proteobacteria and Lachnospiraceae. Gut 2021;70:666–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Guo Y, Wang Het al. Gut commensal Parabacteroides distasonis alleviates inflammatory arthritis. Gut 2023;2022:327756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tei R, Baskin JM.. Click chemistry and optogenetic approaches to visualize and manipulate phosphatidic acid signaling. J Biol Chem 2022;298:101810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng F, Klinger CN, Felix KMet al. Gut microbiota drive autoimmune arthritis by promoting differentiation and migration of peyer’s patch T follicular helper cells. Immunity 2016;44:875–888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian D, Han M. Bacterial peptidoglycan muropeptides benefit mitochondrial homeostasis and animal physiology by acting as ATP synthase agonists. Develop Cell 2022;57:361–372.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Typas A, Banzhaf M, Gross CAet al. From the regulation of peptidoglycan synthesis to bacterial growth and morphology. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012;10:123–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rhijn I, van Berlo T, Hilmenyuk Tet al. Human autoreactive T cells recognize CD1b and phospholipids. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2016;113:380–385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W, Blanot D, De Pedro MA.. Peptidoglycan structure and architecture. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008a;32:149–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer W, Joris B, Charlier Pet al. Bacterial peptidoglycan (murein) hydrolases. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008b;32:259–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vos WM, Tilg H, Van Hul Met al. Gut microbiome and health: mechanistic insights. Gut 2022;71:1020–1032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Heng BC, Qiu Set al. Lipoteichoic acid of Enterococcus faecalis inhibits osteoclastogenesis via transcription factor RBP-J. Innate Immun 2019;25:13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Tang L, Feng Yet al. A purified membrane protein from Akkermansia muciniphila or the pasteurised bacterium blunts colitis associated tumourigenesis by modulation of CD8 + T cells in mice. Gut 2020a;69:1988–1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Ahmadi S, Nagpal Ret al. Lipoteichoic acid from the cell wall of a heat killed Lactobacillus paracasei D3-5 ameliorates aging-related leaky gut, inflammation and improves physical and cognitive functions: from C. elegans to mice. GeroScience 2020b;42:333–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yang Q, Du Yet al. Metabolic labeling of peptidoglycan with NIR-II Dye enables in vivo imaging of gut microbiota. Angew Chem Int Ed 2020c;59:2628–2633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver CT, Elson CO, Fouser LAet al. The Th17 pathway and inflammatory diseases of the intestines, lungs, and skin. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis 2013;8:477477512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney JC, Peterson SB, Kim Jet al. A broadly distributed toxin family mediates contact-dependent antagonism between Gram-positive bacteria. eLife 2017;6:e26938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis LM, Stupak J, Richards MRet al. Conserved glycolipid termini in capsular polysaccharides synthesized by ATP-binding cassette transporter-dependent pathways in Gram-negative pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:7868–7873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf AJ, Reyes CN, Liang Wet al. Hexokinase is an innate immune receptor for the detection of bacterial peptidoglycan. Cell 2016;166:624–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Wang K, Wang Xet al. The role of the gut microbiome and its metabolites in metabolic diseases. Protein Cell 2021;12:360–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Cong Y.. Gut microbiota-derived metabolites in the regulation of host immune responses and immune-related inflammatory diseases. Cell Mol Immunol 2021;18:866–877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Xiao K, Chen Xet al. Neuron-derived neuropeptide Y fine-tunes the splenic immune responses. Neuron 2022;110:1327–1339.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Liao X, Sparks JBet al. Dynamics of gut microbiota in autoimmune lupus. Appl Environ Microbiol 2014;80:7551–7560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou Y, Xue W, Luo Get al. 1,520 reference genomes from cultivated human gut bacteria enable functional microbiome analyses. Nat Biotechnol 2019;37:179–185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]