Abstract

The pathogenic bacterium Campylobacter jejuni has been regarded as endogenously resistant to trimethoprim. The genetic basis of this resistance was characterized in two collections of clinical isolates of C. jejuni obtained from two different parts of Sweden. The majority of these isolates were found to carry foreign dfr genes coding for resistant variants of the dihydrofolate reductase enzyme, the target of trimethoprim. The resistance genes, found on the chromosome, were dfr1 and dfr9. In about 10% of the strains, the dfr1 and dfr9 genes occurred simultaneously. About 10% of the examined isolates were found to be negative for these dfr genes and showed a markedly lower trimethoprim resistance level than the other isolates. The dfr9 and dfr1 genes were located in the context of remnants of a transposon and an integron, respectively. Two different surroundings for the dfr9 gene were characterized. One was identical to the right-hand end of the transposon Tn5393, and in the other, the dfr9 gene was flanked by only a few nucleotides of a Tn5393 sequence. The insertion of the dfr9 gene into the C. jejuni chromosome could have been mediated by Tn5393. The frequent occurrence of high-level trimethoprim resistance in clinical isolates of C. jejuni could be related to the heavy exposure of food animals to antibacterial drugs, which could lead to the acquisition of foreign resistance genes in naturally transformable strains of C. jejuni.

Species of the genus Campylobacter are prevalent pathogens causing acute gastroenteritis in humans (40). Erythromycin, fluoroquinolones, and doxycycline have been used for patients with severe symptoms, relapses, or a prolonged course of Campylobacter infection (18, 25, 43). Trimethoprim, however, has been considered an inefficient antimicrobial agent for the treatment of Campylobacter infections. This was based on earlier observations by Karmali et al. (15) showing that strains of Campylobacter jejuni are endogenously resistant to trimethoprim. All of the more than 50 isolates tested by Karmali et al. were resistant to more than 250 μg, and some to more than 500 μg, of trimethoprim per ml. According to this notion of trimethoprim resistance, trimethoprim at 3 to 5 μg/ml is commonly used in combination with other antibiotics, like vancomycin, bacitracin, and cephalothin, as a selective supplementation for the isolation of C. jejuni from water, stool, food, and other environmental samples. Detailed studies regarding this allegedly intrinsic trimethoprim resistance are lacking.

Trimethoprim exerts its antibacterial action through the selective inhibition of bacterial dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR), which is an essential enzyme in all living cells (11). Endogenous resistance to trimethoprim occurs among some bacterial species, such as lactobacilli, Bacteroides species, Pediococcus cerevisiae, and Clostridium species (37, 38). Purified preparations of DHFR from these species require several-hundredfold-higher trimethoprim concentrations than similar preparations from a susceptible organism, like Escherichia coli, for a 50% inhibition (37, 38). Low-level resistance to trimethoprim was found to develop from a mutational loss in bacteria of the ability to methylate deoxyuridylic acid to thymidylic acid, making them dependent on an external supply of thymine (16). In this situation, the cell can afford to have a relatively large fraction of its DHFR enzyme inactivated by trimethoprim. Trimethoprim resistance could also be explained by the occurrence of a mutational change(s) in the chromosomal dfr gene of pathogenic bacteria, making the enzyme of these strains less susceptible to trimethoprim, as in the case of Streptococcus pneumoniae (1) and Staphylococcus aureus (6). Such changes could be combined with regulatory mutations, leading to cellular overproduction of the resistant enzyme, as detected in the case of trimethoprim-resistant isolates of Haemophilus influenzae (7) and E. coli (9). On the other hand, trimethoprim resistance could be mediated by horizontal genetic exchange, leading to the acquisition of foreign dfr genes expressing drug-resistant variations of DHFR (11, 30). Several dfr genes borne on transposons and integrons and expressing drug-resistant DHFRs are now known (11, 36).

The present study was an attempt to characterize the genetic basis of trimethoprim resistance in two collections of clinical isolates of C. jejuni from two different regions of Sweden. In spite of the fact that trimethoprim is not used in the clinical treatment of Campylobacter infections, further data regarding the details of trimethoprim resistance in C. jejuni might be of interest as a contribution to the general understanding of the pathogenicity of this organism. High-level resistance to trimethoprim in almost 40 clinical isolates of C. jejuni was found to be associated with the acquisition of dfr genes expressing a drug-resistant variant of the target enzyme, DHFR. The most commonly found gene was dfr1 (DHFR gene of type 1 [10, 11]) but another gene, dfr9 (DHFR gene of type 9 [11, 14]), was also detected. These genes were observed to be chromosomally located in the context of remnants of an integron and a transposon, respectively.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Campylobacter strains.

Twenty-one clinical isolates of C. jejuni from the bacteriological laboratory of the Department of Infectious Diseases, Uppsala University, were used in this study (Table 1). For comparison, a collection of 20 clinical isolates of C. jejuni from another part of Sweden (Department of Clinical Bacteriology, Göteborg University) was also analyzed. These strains were considered unrelated, because they were isolated from patients returning from travel abroad and presenting symptoms of disease.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the investigated clinical strains of C. jejuni isolated in Uppsala, Sweden

| Isolate | Resistance marker(s)a | Trimethoprim resistance gene(s)b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tp Su | dfr1 |

| 2 | Tp Ap Dc | dfr1 |

| 3d | Tp Su | dfr1 |

| 4 | Tp Ap | dfr9 and dfr1 |

| 5 | Tp | dfr1 |

| 6d | Tp Ap | dfr9 and dfr1 |

| 7 | Tp Su | dfr1 |

| 8 | Tp Ap | dfr1 |

| 9 | Tp Dc | dfr1 |

| 10 | Tp Dc | dfr9 and dfr1 |

| 11 | Tp Dc | dfr1 |

| 12 | Tp Ap Dc | dfr1 |

| 13c | Tp | dfr9 |

| 14 | Tp Ap Dc Na Su | dfr1 |

| 15d | Tp Ap Dc Na Su | dfr1 |

| 16 | Tp Ap | dfr1 |

| 17 | Tp Dc Su | dfr9 |

| 18 | Tp Ap | dfr9 |

| 19c | Tp Ap Dc | dfr9 and dfr1 |

| 20c | Tp Ap Dc | dfr9 |

| 21 | Tp Ap Dc | dfr1 |

Abbreviations: Tp, trimethoprim; Ap, ampicillin; Dc, doxycycline; Na, nalidixic acid; Su, sulfonamide. Resistance markers of the investigated strains were determined with commercially available disks. In the case of trimethoprim, MICs for different isolates were determined by the agar dilution method as described previously (15).

Trimethoprim resistance gene(s) found to occur on the chromosomes of the strains and characterized by the PCR amplification method as described in Results and Discussion.

Clinical isolate of C. jejuni from which the trimethoprim resistance gene dfr9 was cloned for further characterization.

Clinical isolate of C. jejuni from which the trimethoprim resistance gene dfr1 was cloned for further characterization.

Antibiotic susceptibility testing.

Ten different antimicrobial agents on disks (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden) were used for susceptibility testing as described previously (42). Cultures of C. jejuni for this purpose were prepared by inoculating four or five colonies of each isolate into 5 ml of brucella broth supplemented with ferrous sulfate, sodium metabisulfite, and sodium pyruvate to obtain a final concentration of 0.05% of each supplement and then were incubated at 42°C in the presence of 7% CO2 with Campylobacter gas-generating kits (BBL Microbiology Systems, Cockeysville, Md.) until the desired turbidity was attained. The turbidity of the broth was equivalent to that of a standard prepared by adding 0.5 ml of 1.17% (wt/vol) barium chloride dihydrate solution to 99.5 ml of 0.36 N sulfuric acid (42). Samples were swabbed onto the surfaces of Iso-Sensitest plates (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom) so that an even distribution of the inoculum was obtained. Then, the inoculated plates with the antibiotic disks were incubated for 24 h at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions as described above. Zone sizes were interpreted according to the guidelines of the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (19).

Determination of trimethoprim MICs.

The agar dilution method was used as described previously (15). Trimethoprim was obtained from Wellcome, London, United Kingdom. The inoculated plates were incubated at 42°C under microaerophilic conditions and read after 48 h to determine MICs.

Plasmid DNA isolation procedures.

Strains of C. jejuni were screened for plasmid DNA content by the method of Birnboim and Doly (3).

Genomic DNA preparation.

Chromosomal DNA was prepared according to the method described by Pitcher et al. (22).

Transformation.

A modification of the method of Rådström et al. (23) was used. For the transformation, one of the C. jejuni strains which is susceptible to low levels of trimethoprim (50 μg/ml) and does not carry either the dfr1 or the dfr9 gene was used as a recipient. Two loopfuls of a 24-h culture of the recipient strain on brucella agar were suspended in 1 ml of 50 mM CaCl2 solution and incubated on ice for 20 min. Then, 50 μl of the recipient suspension was mixed with 0.2 μg of the chromosomal DNA extracted from highly trimethoprim-resistant C. jejuni strains (isolates 2, 3, 5, 13, 16, and 19 [Table 1]). A negative control containing the recipient cells only was also included and treated in the same way as the samples. All samples were immediately incubated at 42°C in a water bath for 3 min. Then, each sample was applied on a section of a brucella agar plate and incubated for 4 h at 42°C in a microaerophilic atmosphere. After incubation, the bacterial growth in each case was scraped and suspended in 100 μl of phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). The suspension was then spread with and without dilution on the surface of an Iso-Sensitest agar plate containing 300 μg of trimethoprim per ml. In each case, 50 μl containing 0.2 μg of the corresponding donor DNA without any recipient cells was also spread on a trimethoprim-containing plate (300 μg/ml) as a second negative control. Then, the inoculated plates were incubated at 42°C for 48 h microaerophilically.

Cloning of the trimethoprim resistance gene.

Genomic DNA from clinical isolates of C. jejuni was digested with different restriction enzymes (Boehringer, Mannheim, Germany), such as PstI, HindIII, Sau3A, and BamHI. Restriction digests were carried out according to the supplier’s instructions. DNA fragments in each case were ligated into a similarly cleaved cloning vector, pUC19 (27). Ligation was performed in 50 mM Tris hydrochloride (pH 7.5)–10 mM magnesium chloride–10 mM dithiothreitol–1 mM ATP–1 mg of bovine serum albumin per ml–2 U of T4 DNA ligase (New England BioLabs, Inc., Beverly, Mass.). The ligation mixtures were incubated at 16°C for 12 h. Competent E. coli (DH5α) was obtained for transformation as described by Dagert and Ehrlich (5). Selection of the transformants was performed on Iso-Sensitest agar plates (Oxoid) containing both ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and trimethoprim (20 μg/ml). Ampicillin was from Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.

Identification of the dfr9 and dfr1 genes in clinical isolates of C. jejuni by PCR.

PCRs were performed in a total volume of 50 μl containing the following: one of the oligonucleotide primer pairs (50 pmol of each primer), P1-P2 or P3-P4, with restriction enzyme sites at the ends (Table 2); dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP at 200 μM each; 1× reaction buffer (50 mM potassium chloride, 10 mM Tris hydrochloride [pH 8.3], 1 mM magnesium chloride); and 1.25 U of Taq polymerase (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.). The template for PCR was prepared by suspending a loopful of each isolate, which had been growing on a petri dish, in 500 μl of sterile water, followed by boiling for 10 min and centrifugation for 8 min. Twenty μl of the supernatant was used in the amplification procedure described above. Thirty cycles of amplification were performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). Each cycle consisted of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 55°C for 1 min, and then extension at 72°C for 2 min. A positive control and a negative control were included in each PCR run. The amplified PCR products (398 bp from the dfr9 gene and 254 bp from the dfr1 gene) were analyzed by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels. Products of PCR were purified as described previously (20) and digested with EcoRI and BamHI, generating fragments which were cloned into M13mp18 or M13mp19 (dfr9) or pUC18 or pUC19 (dfr1) as described previously (27).

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide PCR primers used in this study

| Oligonucleotide primera | Sequenceb | Position | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | 5′-ATGAATTCCCGTGGCATGAACCAGAAGAT-3′ | 65–85 (dfr9) | 14 |

| P2 | 5′-ATGGATCCTTCAGTAATGGTCGGGACCTC-3′ | 464–444 (dfr9) | 14 |

| TN1 | 5′-CTGAATTCTGGAAACTCGTATCTGAGGTC-3′ | 425–445 (dfr9) | 14 |

| TN2 | 5′-ATGGATCCGGTCCAATCGCAGATAGAAG-3′ | 786–767 (strA) | 4 |

| TN3 | 5′-CCGAATTCCTTGCCTTCTATCTGCG-3′ | 761–778 (strA) | 4 |

| TN4 | 5′-CTGGATCCGCGAAATCCTACGCTAA-3′ | 61–41 (IRR-5393c) | 4 |

| TN5 | 5′-CAGAATTCGGAATCCTACGCTAAGGC-3′ | 23–40 (IRL-5393d) | 4 |

| TN6 | 5′-TCGGATCCCAAGCCATGATCGAGCGCCA-3′ | 2386–2405 (tnpA) | 4 |

| P3 | 5′-ACGGATCCTGGCTGTTGGTTGGACGC-3′ | 117–134 (dfr1) | 32 |

| P4 | 5′-CGGAATTCACCTTCCGGCTCGATGTC-3′ | 371–354 (dfr1) | 32 |

These oligonucleotides were synthesized by Scandinavian Gene Synthesis, Köping, Sweden.

A restriction enzyme site (EcoRI or BamHI) was added to the 5′ end of each primer to enable subsequent cloning of the PCR product into a similarly cleaved cloning vector for sequencing analysis.

IRR-5393, right inverted repeat of Tn5393.

IRL-5393, left inverted repeat of Tn5393.

Characterization of the genetic organization of the dfr9 gene on the chromosome of C. jejuni.

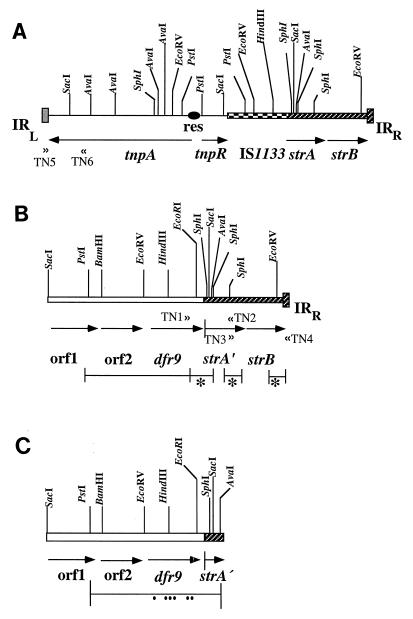

In order to analyze the genetic organization of the dfr9 gene located on the chromosome of C. jejuni, three pairs of PCR primers, TN1-TN2, TN3-TN4, and TN5-TN6, were used (Fig. 1; Table 2). The PCR amplifications were performed in a total volume of 50 μl. The PCR buffer contained 1.5 mM MgCl2. Deoxynucleoside triphosphates were at a concentration of 200 μM each. A total of 1.25 U of Taq polymerase was added to each reaction mixture. The oligonucleotide primers were used at a concentration of 0.5 μM each. The amplification reactions were performed in a DNA thermal cycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus). The PCR protocol consisted of 30 cycles of the following: 1 min of denaturation at 94°C, 2 min of primer annealing at 55°C, and 2 min of extension at 72°C. The cycles were terminated by a final 10-min extension at 72°C. The templates for PCR were prepared as described above. The reaction products were electrophoresed on 1% agarose gels and purified as described previously (20). Digestion with EcoRI and BamHI generated fragments of 1.04 kb (TN1-TN2), 960 bp (TN3-TN4), and 500 bp (TN5-TN6), which were cloned into pUC19 as described previously (27) for subsequent sequencing.

FIG. 1.

Transposon-like surroundings of the dfr9 gene on the chromosome of C. jejuni. (A) Genetic map of Tn5393. The map of Tn5393 was described by Chiou and Jones (4). strA and strB are streptomycin resistance genes, tnpA is a transposase gene, tnpR is a resolvase gene, IS1133 is an insertion element, and TN5 and TN6 are a PCR primer pair used to identify the left-hand part of transposon Tn5393. res, recombination site; IRR and IRL, right and left inverted repeats of the transposon, respectively. (B) Genetic organization of the dfr9 gene in a Tn5393-like structure (C. jejuni isolates 6 and 13). The lines below the genetic map show the sequenced regions. Asterisks indicate that these parts were amplified by PCR and subsequently sequenced. TN1, TN2, TN3, and TN4 are PCR primers designed to characterize the genetic organization of the dfr9 gene on the chromosome of C. jejuni. orf1 and orf2, open reading frames 1 and 2, consisting of 921 and 510 nucleotides, respectively (13); IRR, the right inverted repeat of Tn5393. (C) The dfr9 gene surrounded only by short sequences of Tn5393 (C. jejuni isolate 20). The line below the map represents the sequenced region. Dots below the line indicate the sequence aberrations in the dfr9 gene leading to nonsynonymous substitutions of amino acids as shown in Table 3.

Nucleotide sequencing.

The dideoxynucleotide chain termination method of Sanger et al. was used (28). Single- and double-stranded templates for the reaction were prepared by cloning into either M13mp18 or M13mp19 or either pUC18 or pUC19, respectively, as described previously (27, 45). The universal 17-nucleotide primers specific for M13mp18/19 and pUC19/18 were used as sequencing primers. Single-stranded M13mp18/19 templates for sequencing were extended with Sequenase (United States Biochemical Corporation) as described previously (45). In the case of double-stranded templates, they were prepared for sequencing by the method of Wong et al. (44). For computer analysis of the sequence data, the software from the University of Wisconsin Genetics Computer Group (8) was used.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Antibiotic resistance pattern of the investigated strains.

Investigated strains are presented in Table 1. Resistance traits are defined by the results from antibiotic susceptibility testing as described in Materials and Methods. Some of the tested agents were found to be highly effective against all strains used in this study, as indicated by the diameters of the corresponding inhibition zones (19). These agents include gentamicin, streptomycin, kanamycin, chloramphenicol, and erythromycin. Although nalidixic acid showed high activity against the majority of tested isolates, we have detected two isolates that exhibited marked resistance against it. Our results also indicated the occurrence of sulfonamide resistance among different clinical isolates of C. jejuni. Six of the 21 strains listed in Table 1 were found to be resistant to sulfonamide. About half of the investigated strains also showed resistance to either ampicillin or tetracycline, while 7 of the 21 were found to be resistant to both ampicillin and tetracycline. It ought to be mentioned that during transformation in E. coli, small plasmids mediating both ampicillin and tetracycline resistance in two of the isolates have been detected. These plasmids, which will be investigated further, were 5 to 10 kb in size and expressed both ampicillin and tetracycline resistance in E. coli.

All of the investigated C. jejuni strains were found to be resistant to 500 to 1,000 μg of trimethoprim per ml, with only four exceptions (see below).

Detection of the trimethoprim resistance genes, dfr9 and dfr1, on the chromosome of C. jejuni.

In order to characterize the high level of trimethoprim resistance in the collected isolates, determinants from the clinical strains of C. jejuni (Table 1) were cloned on a plasmid vector (pUC19). Six of the investigated strains were found to produce trimethoprim-resistant transformants of E. coli. These were found to be resistant to 1,000 μg of trimethoprim per ml.

On the basis of sequencing data, the resistance determinants isolated by molecular cloning in isolates 3, 6, and 15 (Table 1) showed identity to the dfr1 gene (10, 29). The dfr1 gene cloned from isolates 6 and 15 was furthermore found to be inserted in a cassette-like manner (33). The surroundings of the cloned dfr1 cassette from isolate 15 showed several integron-like features, such as the occurrence of the GTTAA sequence flanking the dfr1 gene. It is known that the sequence GTTPuPu serves as the target for the site-specific recombination involved in the insertion and excision of gene cassettes into an integron context (24). In addition, we have detected a short, imperfect, inverted repeat element at the 3′ end of the cloned gene, which represents another essential feature of the gene cassettes known as the 59-base element (24). The detected 59-base element was found to be identical to that of the Tn7 dfr1 cassette (32).

Corresponding cloning experiments with isolates 13, 19, and 20 (Table 1) and subsequent sequencing showed that the trimethoprim resistance determinants cloned from these strains are homologous to the dfr9 gene. This gene was earlier characterized as a trimethoprim resistance gene in swine isolates of E. coli (12, 14). It has so far not been detected in any other organism. The trimethoprim resistance determinant originating from C. jejuni isolate 20 was selected for further characterization. In this case, the resistance determinant mediating trimethoprim resistance was found on an 8-kb PstI fragment of chromosomal DNA. A similar fragment was also found for isolates 13 and 19. Part of the fragment originating from C. jejuni isolate 20 was subcloned as a PstI-BamHI fragment of about 4 kb. Both clones were found to mediate resistance to trimethoprim (1,000 μg/ml) in an E. coli host. The 32P-labelled (Multiprime kit; Amersham, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) 4-kb PstI-BamHI fragment was used as a probe in a Southern blot hybridization experiment and was found to hybridize to a fragment of about 8 kb in a PstI digest of chromosomal DNA from isolate 20 (data not shown). A smaller BamHI-EcoRI subclone (1.2 kb) was prepared and was found to mediate a high level of trimethoprim resistance (1,000 μg/ml) in E. coli, and by nucleotide sequence analysis, it was found to be identical to the dfr9 gene, with nine exceptions. These nine nucleotide differences are listed in Table 3. Six of them were found to result in amino acid changes.

TABLE 3.

Nucleotide and amino acid discrepancies in the sequence of the dfr9 gene in isolate 20

| Amino acid positiona | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change |

|---|---|---|

| 34 | AAA→AAG | None |

| 92 | TTC→TTG | F→L |

| 124 | ACT→ACC | None |

| 127 | CAG→CTG | Q→L |

| 138 | TTA→TTT | L→F |

| 139 | TCC→TTC | S→F |

| 175 | CCC→CAC | P→H |

| 176 | ACA→ACT | None |

| 177 | TGT→CGT | C→R |

Numbering of amino acids according to reference 14.

The 21 clinical isolates of C. jejuni (Table 1) were analyzed by PCR for the presence of the trimethoprim resistance genes, dfr9 and dfr1. Two pairs of PCR primers were designed according to the published sequence of the dfr9 (14) and dfr1 (10) genes (see Materials and Methods). Of the 21 isolates of C. jejuni listed in Table 1, 8 gave the expected product of 399 bp with the primers specific for the dfr9 gene (P1 and P2 [Table 2]). The amplified products in all of these cases were cloned into the M13mp18 or M13mp19 vector for subsequent characterization. Sequence analysis of the cloned PCR products confirmed the specificity of the PCR amplification, and the products showed a high degree of similarity with the earlier published sequence of the dfr9 gene (14). The most commonly found trimethoprim resistance gene among the investigated strains was dfr1, however. The expected product of 254 bp was detected in 17 of the 21 strains examined with specific primers P3 and P4 (Table 2). In 10 of these cases, the identity with dfr1 was determined by sequence analysis of the amplified product after its cloning into the pUC18 or pUC19 vector. In the majority of cases (Table 1), either dfr9, dfr1, or both were detected as the trimethoprim resistance determinants.

For comparison, another collection of clinical isolates of C. jejuni from a different geographical area was investigated. Among these strains also, the dfr1 gene was found by PCR to be the predominant trimethoprim resistance gene (13 positive cases of 20). The occurrence of the dfr9 gene was also frequent (11 of 20 cases). Both genes, dfr1 and dfr9, were detected in 8 of the 20 strains. On the other hand, four isolates showed negative results when tested for dfr1 and dfr9. These isolates were found to be susceptible to either 50 or 100 μg of trimethoprim per ml, thus showing a marked difference in their trimethoprim resistance level compared to the other isolates examined in this study. This lower but still relatively high resistance to trimethoprim could be due to an unknown gene of foreign origin or to characteristics of the endogenous DHFR target gene. One of these more susceptible isolates was transformed to a higher level of trimethoprim resistance (300 μg/ml) by the genomic DNA extracted from highly resistant strains that carry either the dfr1 or the dfr9 gene or both (isolates 2, 3, 5, 13, 16, and 19 [Table 1]). The resulting transformants were also found to grow in the presence of 500 μg of trimethoprim per ml.

On the basis of these results, it was determined that the dfr1 gene dominates as the trimethoprim resistance trait among the strains. The dfr9 gene, which was detected in about one-third of the isolates examined here, has, with the exception of one isolate from a patient, been found only in porcine isolates of E. coli (12, 14). The acquisition of both the dfr9 and dfr1 genes by the strains of C. jejuni isolated from patients could demonstrate the spread of these genes from domestic animals to humans. A common habitat for Campylobacter and other bacteria is the human or animal gastrointestinal tract (34). Modern husbandry with large stables and many animals creates very large populations of genetically interconnected bacteria, in which very rare recombinational events could come to the surface under the selection pressure of antibacterial drugs like trimethoprim, which is used extensively in swine rearing in Sweden. Strains of Campylobacter have a natural ability for transformation (41). The G-C content (about 40%) of both dfr1 and dfr9 is higher than that of the genome of C. jejuni (2), suggesting that the genes originated in another organism. There are several reasons to suggest that Campylobacter species can take up genes from members of the Enterobacteriaceae family as well as from gram-positive cocci (21, 31, 39). The tetracycline resistance gene tetO, for example, found in Campylobacter coli and C. jejuni, was found most probably to have had its origin in gram-positive cocci (31, 35), and the kanamycin resistance gene observed in Campylobacter was determined to have had its origin in a gram-positive coccus or a strain of Enterobacteriaceae (21, 39).

Genetic organization of the dfr9 gene on the chromosome of C. jejuni.

In earlier observations of dfr9 in isolates of E. coli from swine, the gene was always found to be inserted in an element identical to the right-hand part of transposon Tn5393, characterized by Chiou and Jones (Fig. 1A) (4). The right-hand part of Tn5393 was found to include the streptomycin resistance genes, strA and strB, and a right inverted repeat of 81 bp (Fig. 1A) (4). In the original Tn5393, an insertion element, IS1133, was also observed to be located between the transposition genes and the streptomycin resistance genes (Fig. 1A) (4). In the previously mentioned E. coli isolates, the dfr9 gene was found to be inserted instead of IS1133, but the insertion point differed by 119 nucleotides, causing a truncation of the strA gene and the loss of streptomycin resistance (Fig. 1B) (13).

In order to determine if the dfr9 gene located on the chromosome of C. jejuni had similar surroundings, a PCR approach was used. Three PCR primers were designed on the basis of the published sequence of the dfr9 gene (14), as well as the sequence of Tn5393 (4). One pair of primers were TN1 and TN2, which are located close to the 3′ end of the dfr9 gene (14) and the 3′ end of the strA gene of Tn5393 (4), respectively (Fig. 1B; Table 2). Using this pair, it was possible to detect if the dfr9 gene in C. jejuni was inserted in a Tn5393 structure and at the same point in the strA gene of Tn5393, as previously reported (13, 14). Another PCR primer pair, TN3-TN4, was also designed; the TN3 primer is situated at the 3′ end of the strA gene of Tn5393, while TN4 is located close to the 3′ end of the right inverted repeat of Tn5393 (Fig. 1B) (4). This primer pair was used to ascertain the occurrence of the strB gene and the right inverted repeat of Tn5393 in association with the dfr9 gene. Using these two PCR primer pairs, only two of the eight dfr9-positive strains (isolates 6 and 13) had positive PCR results, while the others were negative. The left-hand part of Tn5393 was sought by using a third primer pair, TN5-TN6 (Fig. 1A; Table 2). The position of TN5 is at the middle of the left inverted repeat of Tn5393, while TN6 is located at nucleotides 2386 to 2405 in the tnpA gene (Fig. 1A; Table 2) (4). In this case, we found that none of the strains carrying dfr9 gave a positive result, indicating that the left part of Tn5393 seemed to be missing. The surroundings of the dfr9 gene on the chromosome of C. jejuni were further characterized by cloning and sequencing the PCR amplification products (see Materials and Methods and the legend to Fig. 1).

In two of the eight dfr9-positive cases (isolates 6 and 13), sequencing showed the dfr9 gene to be inserted at the 5′ end of the strA gene, resulting in a truncated gene, strA′ (Fig. 1B). The point of insertion of the dfr9 gene into the strA gene was found to be the same as that previously described for the dfr9 gene in the E. coli isolates mentioned above (13). In these two isolates, the right-hand part of Tn5393 with its strA′ gene, strB gene, and right inverted repeat could be detected (Fig. 1B). However, the left part of Tn5393 seemed to be missing in these two cases (Fig. 1B), as indicated by the negative result of PCR amplification with the TN5-TN6 primer pair (Table 2). In C. jejuni isolate 20, however, the dfr9 gene was located at the same position as the strA gene, and outside the 3′ end of dfr9, a small piece of the truncated strA gene could be identified, including nucleotide 263 according to the published sequence of Tn5393 (4). Beyond nucleotide 263 of the strA gene, the sequence was completely different from that of Tn5393. Neither the strB gene nor the right inverted repeat of Tn5393 could be detected, indicating that the dfr9 gene in this case has only a short piece of the Tn5393-like sequence represented by a few nucleotides of the strA gene outside its 3′ end (Fig. 1C).

We concluded that the dfr9 gene observed on the chromosome of isolates of C. jejuni was located in a configuration identical to that seen earlier in porcine isolates of E. coli (13), i.e., inserted close to the 5′ end of the strA gene in the right-hand half of Tn5393 (Fig. 1B) (4). The recombination phenomenon observed by Richardson and Park (26) could possibly be involved in the insertion of this fragment into the chromosome of C. jejuni after natural transformation. In one of the cases studied, the dfr9 gene had only a small piece of Tn5393 at its 3′ end (Fig. 1C) and not the entire right half of the transposon.

In one of the identified dfr9 genes, nucleotide changes leading to amino acid changes were observed (Table 3). This could imply that the dfr9 gene in this case had existed in the chromosome for a long time, and as a result, a number of amino acid changes had occurred, reflecting the instability of the C. jejuni genome. None of the detected amino acid substitutions was involved in the binding of trimethoprim to the DHFR enzyme (17).

The characterization of C. jejuni as a human pathogen is relatively recent. This bacterium has been shown to be highly adaptable because of its natural transformation ability (41). The acquisition of foreign genes mediating trimethoprim resistance could be a reflection of that ability and also of the heavy use of this drug in agriculture.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully thank Carl Påhlson and Eva Sjögren for kindly providing the clinical isolates of C. jejuni used in this study. We also thank Göte Swedberg for helpful discussion and critical reading of this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian P V, Klugman K P. Mutations in the dihydrofolate reductase gene of trimethoprim-resistant isolates of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2406–2413. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.11.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belland R J, Trust T J. Deoxyribonucleic acid sequence relatedness between thermophilic members of the genus Campylobacter. J Gen Microbiol. 1982;128:2515–2522. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-11-2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birnboim H C, Doly J. A rapid alkaline extraction procedure for screening recombinant plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1979;7:1513–1523. doi: 10.1093/nar/7.6.1513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiou C-S, Jones A L. Nucleotide sequence analysis of a transposon (Tn5393) carrying streptomycin resistance genes in Erwinia amylovora and other gram-negative bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:732–740. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.3.732-740.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dagert M, Ehrlich S D. Prolonged incubation in calcium chloride improves the competence of Escherichia coli cells. Gene. 1979;6:23–28. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(79)90082-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dale G E, Broger C, D’Arcy A, Hartman P G, DeHoogt R, Jolidon S, Kompis I, Labhadt A M, Langen H, Locher H, Page M G, Stuber D, Then R L, Wipf B, Oefner C. A single amino acid substitution in Staphylococcus aureus dihydrofolate reductase determines trimethoprim resistance. J Mol Biol. 1997;266:23–30. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de Groot R, Campos J, Moseley S L, Smith A L. Molecular cloning and mechanism of trimethoprim resistance in Haemophilus influenzae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:477–484. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.4.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flensburg J, Sköld O. Massive overproduction of dihydrofolate reductase in bacteria as a response to the use of trimethoprim. Eur J Biochem. 1987;162:473–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb10664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fling M E, Richards C. The nucleotide sequence of the trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase gene harboured by Tn7. Nucleic Acids Res. 1983;11:5147–5158. doi: 10.1093/nar/11.15.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huovinen P, Sundström L, Swedberg G, Sköld O. Trimethoprim and sulfonamide resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:279–289. doi: 10.1128/aac.39.2.279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansson C, Franklin A, Sköld O. Spread of a newly found trimethoprim resistance gene, dhfrIX, among porcine isolates and human pathogens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1992;36:2704–2708. doi: 10.1128/aac.36.12.2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jansson, C., V. Rehbinder, A. Franklin, and O. Sköld. 1997. Unpublished data.

- 14.Jansson C, Sköld O. Appearance of a new trimethoprim resistance gene, dhfrIX, in Escherichia coli from swine. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1991;35:1891–1899. doi: 10.1128/aac.35.9.1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karmali M A, De Grandis S, Fleming P C. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Campylobacter jejuni with special reference to resistance patterns of Canadian isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981;19:593–597. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.King C H, Shlaes D M, Dul M J. Infection caused by thymidine-requiring, trimethoprim-resistant bacteria. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;18:79–83. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.1.79-83.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews D A, Bolin J T, Burridge J M, Fliman D J, Volz K M, Kaufman B T, Beddell C R, Champness J N, Stammers D K, Kraut J. Refined crystal structures of Escherichia coli and chicken liver dihydrofolate reductase containing bound trimethoprim. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:381–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McNoulty C A M. The treatment of Campylobacter infections in man. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1987;19:281–284. doi: 10.1093/jac/19.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards. Performance standards for antimicrobic disk susceptibility tests. Vol. 1. 1981. pp. 141–156. . Approved standard. National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards, Villanova, Pa. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Öfverstedt L G, Hammarström K, Balgobin N, Hjertén S, Pettersson U, Chattopadyaya J. Rapid and quantitative recovery of DNA fragments from gels by displacement electrophoresis (isotachophoresis) Biochim Biophys Acta. 1984;782:120–126. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(84)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ouellette M, Gerbaud G, Lambert T, Courvalin P. Acquisition by a Campylobacter-like strain of aphA-1, a kanamycin resistance determinant from members of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1021–1026. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.7.1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pitcher D G, Saunders N A, Owen R J. Rapid extraction of bacterial genomic DNA with guanidium thiocyanate. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1989;8:151–156. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rådström P, Fermér C, Kristiansen B-E, Jenkins A, Sköld O, Swedberg G. Transformational exchanges in the dihydropteroate synthase gene of Neisseria meningitidis: a novel mechanism for acquisition of sulfonamide resistance. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:6386–6393. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.20.6386-6393.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Recchia G D, Hall R M. Gene cassettes: a new class of mobile element. Microbiology. 1995;141:3015–3027. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-12-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reina J, Borrell N, Serra A. Emergence of resistance to erythromycin and fluoroquinolones in thermotolerant Campylobacter strains isolated from feces, 1987–1991. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:1163–1166. doi: 10.1007/BF01961137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richardson P T, Park S F. Integration of heterologous plasmid DNA into multiple sites on the genome of Campylobacter coli following natural transformation. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:1809–1812. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.5.1809-1812.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simonsen C C, Chen E Y, Levinson A D. Identification of the type I trimethoprim-resistant dihydrofolate reductase specified by the Escherichia coli R-plasmid R483: comparison with procaryotic and eucaryotic dihydrofolate reductases. J Bacteriol. 1983;155:1001–1008. doi: 10.1128/jb.155.3.1001-1008.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sköld O, Widh A. A new dihydrofolate reductase with low trimethoprim sensitivity induced by an R-factor mediating high resistance to trimethoprim. J Biol Chem. 1974;249:4324–4325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sougakoff W, Papadopoulou B, Nordmann P, Courvalin P. Nucleotide sequence and distribution of gene tetO encoding tetracycline resistance in Campylobacter coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1987;44:153–159. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sundström L, Sköld O. The dhfrI trimethoprim resistance gene of Tn7 can be found at specific sites in other genetic surroundings. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990;34:642–650. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.4.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sundström L, Rådström P, Swedberg G, Sköld O. Site-specific recombination promotes linkage between trimethoprim and sulphonamide resistance genes. Sequence characterization of dhfrV and sulI and a recombination active locus of Tn21. Mol Gen Genet. 1988;213:191–201. doi: 10.1007/BF00339581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor D E, Courvalin P. Mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter species. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1107–1112. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.8.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor D E, Garner R S, Allan B J. Characterization of tetracycline resistance plasmids from Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1983;24:930–935. doi: 10.1128/aac.24.6.930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Then R L. History and future of antimicrobial diamino-pyrimidines. J Chemother. 1993;5:361–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Then R L, Angehrn P. Low trimethoprim susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria due to insensitive dihydrofolate reductases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1979;15:1–6. doi: 10.1128/aac.15.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Then R L, Riggenbach H. Dihydrofolate reductases in some folate-requiring bacteria with low trimethoprim susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1978;14:112–117. doi: 10.1128/aac.14.1.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Trieu-Cuot P, Gerbaud G, Lambert T, Courvalin P. In vivo transfer of genetic information between gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria. EMBO J. 1985;4:3583–3587. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Walker R I, Caldwell M B, Lee E C, Guerry P, Trust T J, Ruiz-Palacios G M. Pathophysiology of Campylobacter enteritis. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:81–94. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.1.81-94.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Taylor D E. Natural transformation in Campylobacter species. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:949–955. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.949-955.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Washington J A., II . Antimicrobial susceptibility tests of bacteria. In: Washington II J A, editor. Laboratory procedures in clinical microbiology. New York, N.Y: Springer; 1974. pp. 297–300. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Williams D, Schorling J, Barrett L J, Orgel I, Koch R, Shields D S, Guerrant R L. Early treatment of Campylobacter jejuni enteritis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1989;33:248–250. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.2.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wong W M, Au D M Y, Lam V M S, Tam J W O, Cheng L Y L. A simplified and improved method for the efficient double-stranded sequencing of mini-prep plasmid DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:5573. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.18.5573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]