Abstract

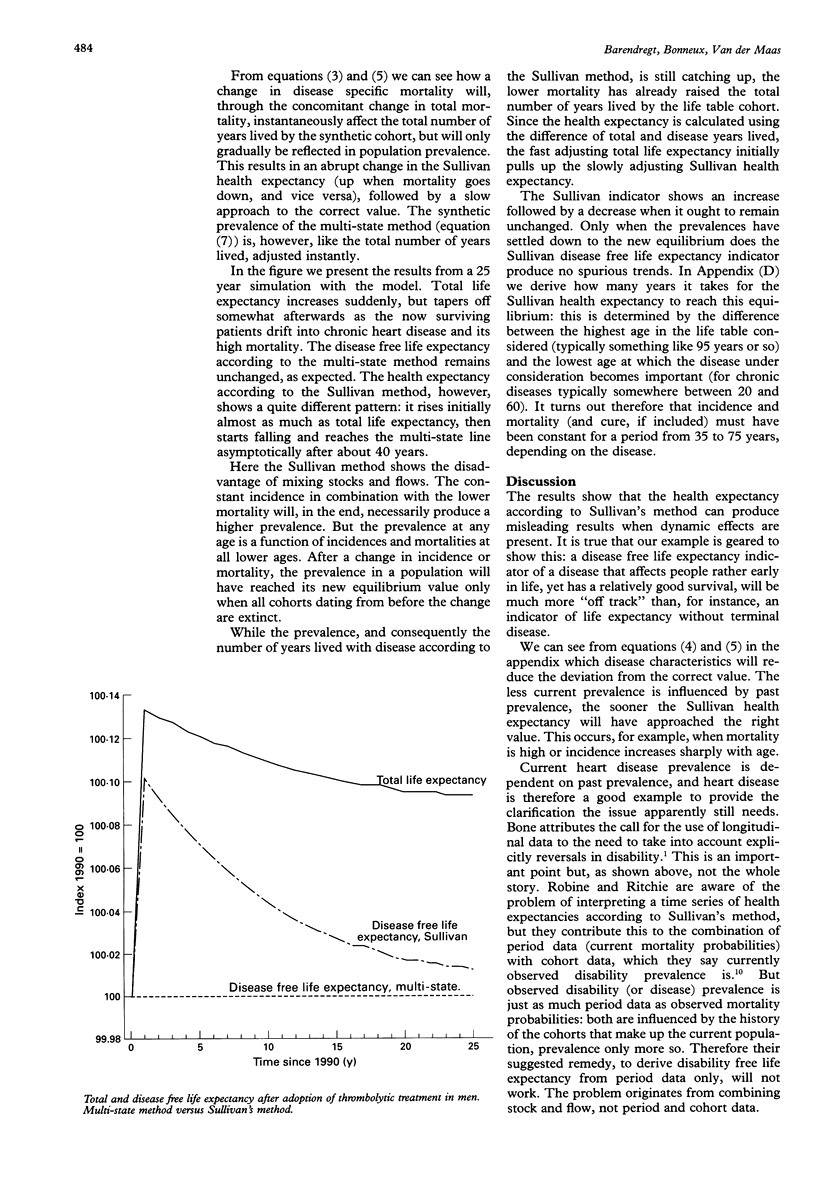

STUDY OBJECTIVE--Health expectancy is an increasingly used indicator of population health status. It collapses both mortality and morbidity into a single indicator, and is therefore preferred to the total life expectancy index for populations with low mortality but high morbidity rates. Three methods of calculation exist: the Sullivan, double decrement, and multi-state methods. This report aims to describe their relative advantages and limitations when used to monitor changes in population health status over time. DESIGN--The differences between the three methods are explained. Using a dynamic model of heart disease, the effect of the introduction of thrombolytic treatment on the survival of patients with acute myocardial infarction is calculated. The resulting changes in health expectancy are calculated according to the Sullivan and multi-state methods. MAIN RESULTS--As opposed to the double decrement and the multi-state methods, the Sullivan method produces spurious trends in health expectancy in response to the change in survival. CONCLUSIONS--Estimates of health expectancy in a dynamic situation can be very misleading when based on the Sullivan method, with its attractively moderate data requirements. The multi-state method, which requires longitudinal studies of population health status, is often indispensable.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bone M. R. International efforts to measure health expectancy. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1992 Dec;46(6):555–558. doi: 10.1136/jech.46.6.555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneux L., Barendregt J. J., Meeter K., Bonsel G. J., van der Maas P. J. Estimating clinical morbidity due to ischemic heart disease and congestive heart failure: the future rise of heart failure. Am J Public Health. 1994 Jan;84(1):20–28. doi: 10.2105/ajph.84.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries J. F. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1980 Jul 17;303(3):130–135. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198007173030304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketley D., Woods K. L. Impact of clinical trials on clinical practice: example of thrombolysis for acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1993 Oct 9;342(8876):891–894. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91945-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine J. M., Michel J. P., Branch L. G. Measurement and utilization of healthy life expectancy: conceptual issues. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70(6):791–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robine J. M., Ritchie K. Healthy life expectancy: evaluation of global indicator of change in population health. BMJ. 1991 Feb 23;302(6774):457–460. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6774.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan D. F. A single index of mortality and morbidity. HSMHA Health Rep. 1971 Apr;86(4):347–354. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinstein M. C., Coxson P. G., Williams L. W., Pass T. M., Stason W. B., Goldman L. Forecasting coronary heart disease incidence, mortality, and cost: the Coronary Heart Disease Policy Model. Am J Public Health. 1987 Nov;77(11):1417–1426. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.11.1417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]