Abstract

Purpose

Limiting family presence runs counter to the family-centred values of Canadian pediatric intensive care units (PICUs). This study explores how implementing and enforcing COVID-19-related restricted family presence (RFP) policies impacted PICU clinicians nationally.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional, online, self-administered survey of Canadian PICU clinicians to assess experience and opinions of restrictions, moral distress (Moral Distress Thermometer, range 0–10), and mental health impacts (Impact of Event Scale [IES], range 0–75 and attributable stress [five-point Likert scale]). For analysis, we used descriptive statistics, multivariate regression modelling, and a general inductive approach for free text.

Results

Representing 17/19 Canadian PICUs, 368 of 388 respondents (94%) experienced RFP policies and were predominantly female (333/368, 91%), English speaking (338/368, 92%), and nurses (240/368, 65%). The mean (standard deviation [SD]) reported moral distress score was 4.5 (2.4) and was associated with perceived differential impact on families. The mean (SD) total IES score was 29.7 (10.5), suggesting moderate traumatic stress with 56% (176/317) reporting increased/significantly increased stress from restrictions related to separating families, denying access, and concern for family impacts. Incongruence between RFP policies/practices and PICU values was perceived by 66% of respondents (217/330). Most respondents (235/330, 71%) felt their opinions were not valued when implementing policies. Though respondents perceived that restrictions were implemented for the benefit of clinicians (252/332, 76%) and to protect families (236/315, 75%), 57% (188/332) disagreed that their RFP experience was mainly positive.

Conclusion

Pediatric intensive care unit-based RFP rules, largely designed and implemented without bedside clinician input, caused increased psychological burden for clinicians, characterized as moderate moral distress and trauma triggered by perceived impacts on families.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12630-023-02547-7.

Keywords: COVID-19/prevention and control, health care personnel, intensive care units, pediatric, visitors to patients

Résumé

Objectif

Limiter la présence de la famille va à l’encontre des valeurs centrées sur la famille des unités de soins intensifs pédiatriques (USIP) canadiennes. Cette étude explore comment la mise en œuvre et l’application des politiques de restriction de la présence familiale liées à la COVID-19 ont eu une incidence sur les cliniciennes et cliniciens des USIP à l’échelle nationale.

Méthode

Nous avons mené un sondage transversal, en ligne et auto-administré auprès des cliniciens et cliniciennes des USIP canadiennes afin d’évaluer leur expérience et opinions sur les restrictions, la détresse morale (thermomètre de détresse morale, intervalle de 0 à 10) et les impacts sur la santé mentale (échelle d’impact des événements [EIE], intervalle de 0 à 75, et le stress qui peut y être attribué [échelle de Likert à cinq points]). Pour l’analyse, nous avons utilisé des statistiques descriptives, une modélisation de régression multivariée et une analyse inductive générale pour le texte libre.

Résultats

Représentant 17/19 USIP canadiennes, 368 des 388 personnes répondantes (94 %) ont vécu des politiques de restriction de la présence familiale et étaient principalement des femmes (333/368, 91 %), anglophones (338/368, 92 %) et infirmières (240/368, 65 %). Le score moyen (écart type [ET]) rapporté de détresse morale était de 4,5 (2,4) et était associé à l’impact différentiel perçu sur les familles. Le score moyen (ET) total de l’EIE était de 29,7 (10,5), ce qui suggère un stress traumatique modéré, 56 % (176/317) des personnes répondantes déclarant une augmentation ou une augmentation significative du stress associé aux restrictions liées à la séparation des familles, au refus d’accès et à la préoccupation pour les impacts familiaux. L’incongruité entre les politiques et les pratiques de restriction des visites familiales et les valeurs des USIP était perçue par 66 % des personnes répondantes (217/330). La plupart (235/330, 71 %) estimaient que leurs opinions n’étaient pas prises en compte lors de la mise en œuvre de politiques. Bien que les répondant·es aient perçu que les restrictions avaient été mises en œuvre dans l’intérêt des cliniciens et cliniciennes (252/332, 76 %) et pour protéger les familles (236/315, 75 %), 57 % (188/332) n’étaient pas d’accord pour dire que leur expérience de la restriction des visites familiales était principalement positive.

Conclusion

Les règles de restriction de la présence familiale dans les unités de soins intensifs pédiatriques, en grande partie conçues et mises en œuvre sans l’avis du personnel clinique au chevet des patient·es, ont entraîné une augmentation du fardeau psychologique pour le personnel clinique, caractérisée par une détresse morale modérée et un traumatisme déclenché par des répercussions perçues sur les familles.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, hospitals around the globe restricted inpatient bedside family presence1–3 to limit viral spread, preserve personal protective equipment, and protect patients and clinicians.2 Most North American pediatric hospitals initially restricted presence to one caregiver,3–6 which addressed some ethical issues from caregiver prohibition during the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic of 2002–2004.7,8 Nonetheless, restricted family presence (RFP) policies represent a significant deviation from the standard of family-centred care (FCC) embraced by most North American children’s hospitals and pediatric intensive care units (PICUs).9

Pediatric intensive care units are a high-stress environment where the majority of pediatric hospital deaths occur.10 Parents, fearing for the life of their child,11 are at risk of trauma12 and in need of care and support from the health care team.13 In PICUs using FCC models, clinicians facilitate family presence and work alongside family members to optimize care of PICU patients.14,15 These humanistic values and interactions improve work satisfaction and decrease clinician burnout.16,17 In this setting, where clinicians value family centredness, RFP policies may result in moral distress.18,19

The experience of restrictions in adult critical care during the COVID-19 pandemic has been explored.20 Within the PICU, one qualitative study found that care provision during the COVID-19 pandemic added stress for clinicians, though it did not focus on the influence of the family presence restrictions.21 To inform future policy and practice, the impact of these policies in a PICU context must be explored to assess the proportionality of the response. This study aimed to explore the impact of RFP policies and practices on PICU clinicians. Our primary objective was to assess the degree of associated moral distress. Secondary objectives were to assess other distress-related mental health impacts associated with restrictions and explore clinician opinions about and experience with RFP policy design and implementation including recommendations for the future.

Methods

Study design and ethical considerations

We conducted a self-administered, web-based, anonymous, cross-sectional survey that adhered to the Consensus-based Checklist for Reporting Of Survey Studies (CROSS, see Electronic Supplementary Material [ESM] eAppendix 1).22 This study was approved by the Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Edmonton, AB, Canada; Study ID: PRO 00102535). A letter of information preceded the survey; participation constituted consent to collect and publish data.

Setting and sample

Through nonprobability voluntary response sampling, we invited any clinician who worked in Canadian PICUs between March and June 2020 to participate in either French or English. Clinicians were defined as any PICU professional who worked with patients and their families including, but not limited to, intensivists, nurses, trainees, respiratory therapists (RRTs), social workers, child life specialists, pharmacists, physiotherapists, and unit aides. On 2 October 2020, we emailed the participation invitation to 19 physician leads and 17 operational managers of the 19 administratively distinct Canadian PICUs (within 17 hospitals),6 and requested forwarding to all PICU staff. The invitation included an untraceable web link and printable posters with quick response codes. Three reminder e-mails were sent to PICU leadership at one-month intervals. This recruitment strategy made it impossible to estimate the number to whom the survey was sent and the response rate. Respondents were not prevented from accessing the survey more than once.

Data sources

We designed a questionnaire (ESM eAppendix 2) that addressed five domains: clinician demographics; baseline and pandemic-related family presence and FCC practices; experience and opinion of RFP policy and practice; moral distress; and impact on the clinicians.

The questionnaire was developed by multiprofessional PICU clinicians, administrators, patient partners, clinician researchers, and an epidemiologist following the methodology described by Burns et al.23 Items were generated using: 1) existing literature on family presence, FCC, and moral distress24 and 2) team discussion of personal and professional experiences of clinicians and patient partners.

We used three tools to assess clinician distress associated with RFP policies: the Moral Distress Thermometer (MDT);25 the Impact of Event Scale (IES);26 and the change in perceived stress using a five-point scale (from 1 [significantly decreased] to 5 [significantly increased]). The MDT is a validated single-item visual analog scale that provides a definition and asks participants to rate their moral distress from 0 (no distress) to 10 (worst distress possible).25 The IES26 is a reliable and valid27 15-item scale that assesses intrusive and avoidance responses to traumatic or stressful events. The IES asks respondents to think about and describe a specific situation or event while answering how often they experienced the given symptoms in the last week (not at all = 0, rarely = 1, sometimes = 3, often = 5). The IES may be interpreted as: 0–19 low; 20–29 moderate; and ≥ 30 high responses,28 with a suggested cut-off of 26 for a clinically relevant reaction.29

We also used the PICU-Family Presence Index (PICU–FPI) tool. This is a reliable and valid 20-item tool developed by our team to assess clinician perception of their PICU’s approach to family presence and participation.30 Participants were asked whether each statement applies to their PICU (yes/no) with each statement assigned a score of − 1 (nonfamily centred) or 1 (family centred). Scores range from − 8 to 12 (see ESM eAppendix 3 for tool development and testing).

The survey was pretested (six multidisciplinary PICU clinicians and two PICU family members) with clinical sensibility testing. The revised survey was then pilot tested for readability and flow (five PICU clinicians). The final instrument included 48 closed and seven open-ended questions. It was offered in English and French, and administered using QualtricsXM (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA).

Data analysis

Survey results were cleaned and exported into IBM SPSS for Windows version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Respondents who indicated they did not experience RFP were excluded; their baseline data were compared descriptively with those included in the full analysis. For missing responses due to skip patterns, we used the actual number of responses as the denominator. Attrition was assessed using linear regression analysis. Nominal variables were reported as percentages; ordinal or skewed continuous data as median and interquartile range [IQR]; and normally distributed continuous variables as mean and standard deviation (SD) or, when compared between two groups, as mean and 95% confidence interval (CI). Visual inspection of histograms was used to assess the normal distribution of the data. We used independent samples t test to compare differences in means between two groups, and the independent samples Kruskal–Wallis test to compare medians. One-way ANOVA was used to compare means between more than two groups, with a Tukey Honestly Significant Difference correction applied to multiple comparisons. Univariate regression analysis assessed the correlations of categorical baseline variables with degree of moral distress, perceived stress, and with the IES. All variables with a bivariate association at the P < 0.10 level were subsequently included in the multivariable stepwise linear regression model, with a minimum of ten subjects per independent variable for adequate statistical power in the analysis. Multicollinearity was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor and Tolerance statistic. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Free text answers to open-ended questions were analyzed using the General Inductive Approach described by Thomas.31 One member of the research team with significant qualitative analytic experience who is not a clinician (M. R.) read all responses, generated a coding framework, applied the framework adding codes as needed, then grouped the codes into categories. These were assessed and verified by another team member with qualitative analytic experience (J. R. F.).

Results

Respondent demographics

Three hundred and eighty-eight responses were received from 17 (90%) of 19 Canadian PICUs between 6 October 2020 and 9 February 2021. Of those who responded, 368/388 (95%, 17 PICUs) indicated that they experienced RFP policies and were included in the full analysis. There were no significant baseline differences for respondents not included in the whole analysis (ESM eAppendix 4). Respondents were predominantly female (333/368, 91%), English-speaking (338/368, 92%), and registered nurses (240/368, 65%) (Table 1). Only free-text questions were skipped. For non free-text questions, response attrition was 21.7% and fit a linear model (y = − 5.8x + 366 [R2 = 0.90]).

Table 1.

Respondent demographics

| Data element | Respondents |

|---|---|

| Profession, n/total N (%) | |

| Consultant physician | 31/368 (8%) |

| PICU fellow/clinical associate/nurse practitioner | 12/368 (3%) |

| Registered nurse | 240/368 (65%) |

| Registered respiratory therapist | 52/368 (14%) |

| Social worker | 7/368 (2%) |

| Other health care professionals (occupational therapy, physiotherapy, child life, unit aide, clinical leader, ward clerk) | 26/368 (7%) |

| Geographic location,† n/total N (%) | |

| Atlantic | 27/368 (7%) |

| Quebec | 55/368 (15%) |

| Ontario | 146/368 (40%) |

| Prairie | 120/368 (33%) |

| British Columbia | 20/368 (5%) |

| Years of experience | |

| < 1 | 16/368 (4%) |

| 1–5 | 112/368 (30%) |

| 5.1–10 | 84/368 (23%) |

| > 10 | 156/368 (42%) |

| Gender, n/total N (%) | |

| Woman | 333/366 (91%) |

| Language in which survey completed, n/total N (%) | |

| English | 338/368 (92%) |

| French | 30/368 (8%) |

Only respondents who indicated that they had worked in the PICU during the period of restricted family presence policies and practices

†Atlantic provinces = Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Newfoundland and Labrador; Prairie provinces = Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta

Mental health impacts

Moral distress

The mean (SD) MDT rating that respondents associated with RFP policies and practices was 4.5 (2.4) out of a possible 10 (n = 307). The bivariate relationship between each of the measures of distress (moral distress, IES, and perceived change in stress) and respondent demographic, impact, and experience variable are outlined in Table 2 and Fig. 1. The results of the multivariable stepwise linear regression models for moral distress, IES, and perceived change in stress are reported in Table 3.

Table 2.

Associations between demographic and dichotomous variables and measures of clinician distress

| Moral distress (range 0–10) | Impact of Event Scale (range 0–45) | Perceived change in stress (1 = significant decrease, 3 = no change, 5 = significant increase) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | n | mean (95% CI) | P value | n | mean (95% CI) | P value | n | mean (95% CI) | P value |

| Female | 274 | 4.6 (4.3 to 4.8) | 0.04 | 260 | 30.0 (28.6 to 31.3) | 0.09 | 283 | 3.4 (3.3 to 3.5) | 0.37 |

| Male | 32 | 3.7 (2.9 to 4.6) | 30 | 26.5 (22.4 to 30.6) | 32 | 3.2 (2.9 to 3.6) | |||

| Role | n | mean (95% CI) | significance | n | mean (95% CI) | significance | n | median (IQR) | P value |

| Staff MD | 28 | 4.6 (3.7 to 5.5) |

r = 0.042 Adjusted r = 0.026 |

27 | 24.6 (20.7 to 28.5) |

r = 0.07 Adjusted r = 0.053 |

28 | 4 (3 to 4) | > 0.05 for all |

| RN | 204 | 4.4 (4.1 to 4.8) | P = 0.02 | 196 | 30.4 (29.0 to 31.8) | P = 0.001 | 212 | 4 (3 to 4) | |

| RRT | 39 | 3.7 (3.0 to 4.4) | 35 | 31.9 (28.5 to 35.3) | 40 | 3 (3 to 4) | |||

| Social worker | 6 | 5.5 ( 3.6 to 7.4) | 6 | 30.3 (22.1 to 38.5) | 6 | 4 (3 to 5) | |||

| Trainee/NP/CA | 12 | 5.2 (3.8 to 6.5) | 11 | 19.4 (13.3 to 25.4) | 9 | 4 (3 to 4) | |||

| Other | 18 | 5.9 (4.8 to 7.0) | 15 | 32.1 (26.9 to 37.3) | 18 | 4 (4 to 4) | |||

| Years of experience | n | mean (95% CI) | significance | n | mean (95% CI) | significance | n | mean (95% CI) | significance |

| < 1 | 13 | 5.0 (3.7 to 6.3) |

r = 0.03 Adjusted r = 0.02 |

13 | 29.3 (23.6 to 35.1) |

r = 0.004 Adjusted r = − 0.007 |

14 | 3.1 (2.6 to 3.2) | rs = − 0.004 |

| 1 to 5 | 89 | 4.8 (4.3 to 5.3) | P = 0.02 | 86 | 29.7 (27.5 to 32.0) | 0.79 | 93 | 3.4 (3.2 to 3.6) | P = 0.95 |

| 5.1 to 10 | 70 | 4.9 (4.3 to 5.4) | 63 | 30.8 (28.2 to 33.4) | 72 | 3.5 (3.3 to 3.7) | |||

| > 10 | 135 | 4.0 (3.6 to 4.4) | 128 | 29.2 (27.3 to 31.0) | 137 | 3.4 (3.2 to 3.5) | |||

| RFP increased my workload | n | mean (95% CI) | P value | n | mean (95% CI) | P value | n | mean (95% CI) | P value |

| Yes | 115 | 5.5 (5.1 to 5.9) | < 0.001 | 107 | 31.6 (29.7 to 33.6) | < 0.001 | 116 | 4.0 (3.8 to 4.1) | < 0.001 |

| No | 192 | 3.9 (3.5 to 4.2) | 183 | 28.6 (27.0 to 30.1) | 200 | 3.1 (2.9 to 3.2) | |||

| Differential impact on some families | n | mean (95% CI) | P value | n | mean (95% CI) | P value | n | mean (95% CI) | P value |

| Yes | 192 | 4.9 (4.6 to 5.2) | < 0.001 | 185 | 29.9 (28.4 to 31.4) | 0.30 | 199 | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.6) | 0.01 |

| No | 103 | 3.7 (3.3 to 4.2) | 97 | 28.6 (26.4 to 30.7) | 108 | 3.2 (3.0 to 3.4) | |||

CA = clinical associate; CI = confidence interval; MD = medical doctor; NP = nurse practitioner; r = Pearson correlation coefficient; RFP = restricted family presence; RN = registered nurse; RRT = registered respiratory therapist; rs = Spearman’s rho

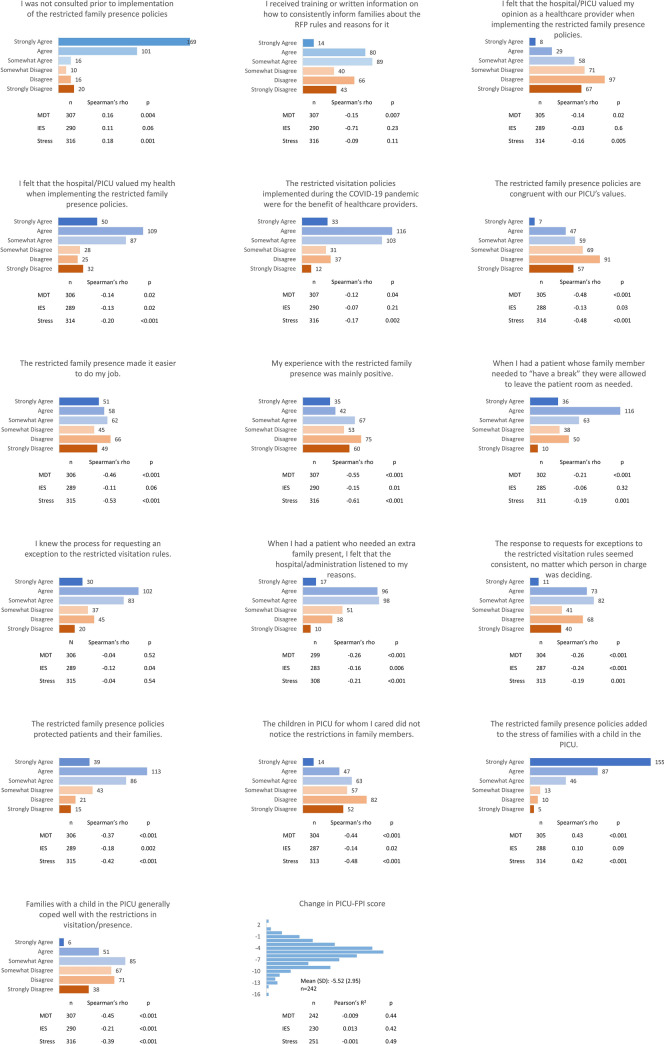

Fig. 1.

Categorical responses and associations with measures of distress

Table 3.

Stepwise multivariable linear regression models

| Outcome | Independent variables found to be statistically significant and included in the final model | Unstandardized Beta (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Moral distress (n = 242) |

RFP was congruent with PICU values | −0.32 (−0.54 to −0.09) | 0.01 |

| Families coped well with RFP | −0.40 (−0.59 to −0.20) | < 0.001 | |

| RFP made the job easier | −0.19 (−0.37 to −0.01) | 0.04 | |

| RFP increased workload | 0.57 (0.02 to 1.12) | 0.04 | |

| RFP added stress to families | 0.24 (0.05 to 0.43) | 0.01 | |

| Felt hospital/PICU valued clinician health with RFP policies | −0.19 (−0.35 to −0.02) | 0.03 | |

| Perceived that some families were differentially impacted | 0.88 (0.38 to 1.38) | 0.001 | |

|

Impact of event scale (n = 230) |

Felt exemption process consistent | −0.88 (−1.72 to −0.04) | 0.04 |

| PICU subspecialty trainee or clinical associate | −10.32 (−16.55 to −4.10) | < 0.001 | |

| Attending physician | −5.99 (−10.32 to −1.68) | 0.01 | |

| Families coped well | −1.00 (−1.92 to −0.09) | 0.03 | |

|

Stress (n = 251) |

RFP made the job easier | −0.18 (−0.25 to −0.11) | < 0.001 |

| RFP increased workload | 0.54 (0.32 to 0.77) | < 0.001 | |

| RFP was congruent with PICU values | −0.08 (−0.17 to 0.01) | 0.09 | |

| Families coped well with RFP | −0.09 (−0.17 to −0.01) | 0.02 | |

| RFP added stress to families | 0.091 (0.02 to 0.17) | 0.02 | |

| Felt hospital/PICU valued clinician health with RFP policies | −0.076 (−0.14 to −0.007) | 0.03 |

CI = confidence interval; PICU = pediatric intensive care unit; RFP = restricted family presence

Mean moral distress was higher in females (4.6; 95% CI, 4.3 to 4.8 vs 3.7; 95% CI, 2.9 to 4.6; P = 0.04). When adjusted for multiple comparisons, moral distress differed by profession only between “other professionals” and RRTs (mean, 5.9; 95% CI, 4.8 to 7.0 vs 3.7; 95% CI, 3.0 to 4.4, respectively; P = 0.01), and did not differ significantly by years of experience. In the multivariable analysis, increased moral distress was associated with perceptions of differential impact of RFP on some families, increased stress for families, and increased workload. Less moral stress was associated with the beliefs that RFP 1) decreased workload, 2) was congruent with PICU values, 3) meant the hospital and PICU valued clinician health, and 4) helped families cope well with restrictions.

When respondents were asked to share any additional comments, thoughts, or experiences related to moral distress, 19 of the 97 free-text responses addressed the theme of “end-of-life care.” Conversely, eight participants identified distress related to aggressive or noncompliant family members and four from lax rules or enforcement.

Impact of event scale

The mean (SD) total IES score associated with RFP was 29.7 (10.5) (n = 290), consistent with a moderate degree of distress.28 We identified seven categories of events or experiences that respondents described as impactful (Table 4). The most frequently reported category (39%) was “concern about the impact on family”, followed by “nonfamily-centred end-of-life situations” (29%).

Table 4.

Impactful experiences during restricted family presence

| Emergent themes | Frequency (N = 146)† |

Sample quotes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Separating families and denying access | n = 36 | “The most distressing moments were watching the expressions of loved ones of patient[s] told they were restricted from staying during pandemic policies.” (HCP-275) |

| 1a. Access denied after significant travel distance | n = 7 | “Family members of a brain dead [child] who came from a city [> 1,000] km away to say goodbye, denied entry. no excepts (sic) to the rules … Highly distressing to bedside staff.” (HCP-112) |

| 1b. Sibling restrictions | n = 14 | “I also had a patient who was born […] during the pandemic and [whose sibling] did not meet [them] until [they were] FIVE months old!!! [Sibling] literally asked to meet [infant] as a birthday present and cried when [they] finally saw [them] in person. Siblings make a difference in our patient's lives!” (HCP-160) |

| 2. Concern about the impact on family | n = 57 | “Going to work every day and listening to the families was the hardest. They appreciated what we were doing but you could feel their stress and pain. You listened to the mother cry on the phone because she had a cough and worried nobody would hold her baby. You held the child's hand while she cried for her best friend/sister. These moments stay with you, they add to our stress.” (HCP-242) |

| 2a. The lone caregiver staying with the child but lacking support | n = 22 | “Caregivers not having their support people easily present to ease the burden of coping with a child in PICU adds more stress. Parents having to choose who gets to be in and who stays out of the hospital can strain relationships and support systems.” (HCP-263) |

| 2b. Caregiver unable to leave room | n = 8 | “Parents of children who were suspect for having covid (sic), or who were positive, were not allowed to leave the patient room. We provided food for them. We tried to put them in … our rooms that had a shower and a toilet […] Some parents described this as jail. It likely really felt that way.” (HCP-338) |

| 3. Non-family centred end-of-life situations | n = 43 | “There was one end-of-life situation that by the time we got approval for an exception, the patient was no longer lucid. We took away the last time they would speak to their siblings, we took away their eyes being open. We did that.” (HCP-241) |

| 3.a Parent unable to be present for end of life | n = 5 | “Car accident victim passing away without both parents allowed in, early in covid (sic)” (HCP-112) |

| 4. Policies and enforcement felt unjust, unfair, or led to moral distress | n = 23 | “I felt that I was not providing support for the family. And that the policy was causing undue stress for a family that was already going through the most stressful life event of having a critically ill child. It broke my heart and I felt that enforcing the rule made me ‘evil.’” (HCP-68) |

| 5. Non-compliance and aggressive reactions to policy | n = 15 | “After some yelling, [the parent] brought [all the siblings] in without getting permission, which put me in a terrible situation because morally I felt that [they] should be able to do this but knew that the hospital had already said no.” (HCP-56) |

| 6. Generally positive or neutral impact of RFP | n = 13 |

“Compared to the rest of the stressors from COVID-19, this was not the biggest contributor for me personally, though I recognize for families it was a significantly greater stressor.” (HCP-332) "The whole experience of restricted visitation contributed to a sense of tangible safety for everyone, by everyone … staff, families, & caregivers alike. The vast majority of parents/caregivers with whom I engaged stated their acknowledgement and appreciation for the visitation policy.” (HCP-81) |

| 7. Inconsistent policy design and application | n = 10 |

“I found us very inconsistent. One parent could not be here for her child to hear a devastating diagnosis and was told they could join the conversation over the phone. However, we allowed another family to have multiple family members and they were not end of life.” (HCP-132) “And our physician team stretched the rules and allowed all the adults to come in against the policy. Our management team on call messaged me back later and said not to let them in. Morally distressing when the doctors and you are not on the same page.” (HCP-17) |

| 8. General or overall experience | n = 12 | “Not one particular incident but cumulative” (HCP-230) |

Themes and important subthemes emerging from responses to the question: describe the event/experience that will be the basis of your answers about the impact of restricted family presence.

†N = number of participants who answered the question; n refers to the number of respondents who discussed the theme, rather than the number of examples touching on the theme. Some excerpts were co-coded so Σn > N

There was no association between IES score and years of experience, profession overall, or gender. Professionally, the PICU fellow/trainee/clinical associate group (mean, 19.4; 95% CI, 13.3 to 25.4) had significantly lower mean scores than RNs (30.4; 95% CI, 29.0 to 31.8; P < 0.01), RTs (31.9; 95% CI, 28.5 to 35.3; P < 0.01) and other clinicians (32.1; 95% CI, 26.9 to 37.3; P = 0.02), though not than staff MDs (24.6; 95% CI, 20.7 to 28.5; P = 0.71).

General stress

Most respondents (176/317, 56%) indicated an increase/significant increase in stress attributable to RFP; 27% (86/317) indicated no change. Change in stress was not correlated with years of experience, profession, or gender (Table 2).

Examining the relationship between measures of clinician distress, moral distress, and alteration in general stress were strongly correlated (rs = 0.6; P < 0.001).32 The IES scores correlated moderately with moral distress (rs = 0.4; P < 0.001) and weakly with alteration in general stress (rs = 0.2; P < 0.001).

Experience and opinion of restricted family presence policy and practice

The mean (SD) PICU-FPI for the era before the pandemic was 6. 8 (2.4) vs 1.3 (2.8) early in the pandemic, with a mean paired difference of − 5.5 (95% CI, 5.2 to 5.8; P < 0.001) (see ESM eAppendix 4). Responses to experience and opinion questions and their associations with measures of clinician distress are displayed in Fig. 1. Most respondents indicated that they were not consulted prior to implementation. Although most agreed that the hospital and PICU valued their health when implementing the policies (246/331, 74%), 57% (188/332) disagreed that their experience with RFP was mainly positive. Many respondents (198/308, 64%) perceived that RFP policies impacted families differentially (Table 5). While 52% (171/331) of respondents agreed that RFP made their job easier, 37% (121/331) indicated an increased workload (Fig. 2).

Table 5.

Groups perceived to have been differentially impacted by restricted family presence policies and practices by bedside PICU health care providers

| Category | Frequency N = 183 |

|---|---|

| Medical conditions and prognosis | 84 |

| Chronic and long-stay patients | 42 |

| End-of-life | 25 |

| New diagnosis, particularly cancer | 12 |

| Severe acute illness and trauma patients | 11 |

| Family structure and age | 83 |

| Families with multiple children | 33 |

| Single parents | 22 |

| Families with newborns | 14 |

| Families with extended family involvement | 14 |

| Divorced or separated parents | 12 |

| Factors related to parents | 35 |

| Parents without a support person | 16 |

| COVID-19 isolation requirements/can’t leave room | 15 |

| Family member intersectionality (e.g., race, language, disability, socioeconomic status) | 32 |

| Families with first language different from institution’s | 10 |

| Family from out of town | 29 |

Subcategories reported where frequency ≥ 10

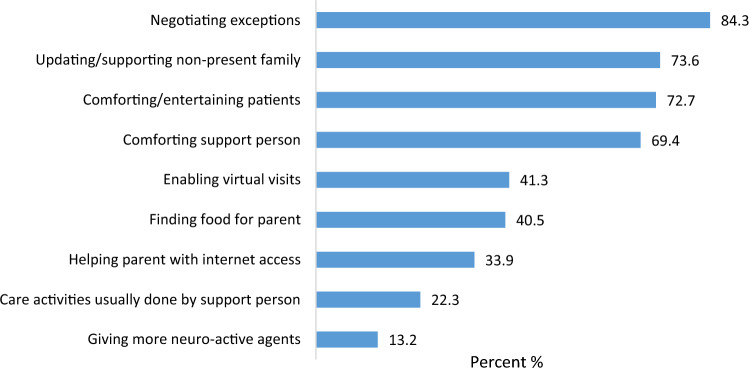

Fig. 2.

Care elements resulting in an increase in workload. Only respondents who indicated an increase in workload due to restrictions in family presence (n = 121, 36.6%). Total > 100% as respondents checked all that applied.

When invited to provide free-text comments on policies, 38 of 164 respondents indicated appreciation for restrictions for reasons beyond infection control; 12 perceived that restrictions should be more strictly enforced, particularly for patients with infectious symptoms.

When asked what future family presence policies should look like, respondents provided answers that fit into three themes: 1) policy priorities (n = 35) including a need to balance competing priorities, maintain FCC, and ensure policy flexibility; 2) policy development (n = 120) that includes stakeholder, and particularly PICU frontline clinician, input and must address the clinician’s opinion that both parents should be present; and 3) policy implementation (n = 84), which must involve clear communication of consistent rules with provisions for enforcement that maintain a therapeutic relationship, additional sources of support for families, and transparent processes for granting rules exceptions. See ESM eAppendix 5 for themes, subthemes, and exemplar quotes.

Discussion

Although Canadian PICUs did not implement the restrictions barring all family presence seen in adult intensive care units (ICUs),6 this study showed that clinicians nonetheless experienced moral distress as a result of RFP policies. Policies and practices were perceived to be implemented without clinician input, to violate PICU values, and to result in decreased family-centredness of care. Although some respondents appreciated having fewer family member interactions, most experienced increased psychological burden associated with denying family access to critically ill children, separating families, and isolating family members from supports. Drawing on their frontline experiences, respondents expressed that future family presence policies should be consistent, developed with stakeholder input, clearly communicated, enable at least two caregivers at once, and provide transparent processes for compassionate rule exceptions.

A recent systematic review addressing RFP impacts identified ten adult and no pediatric ICU studies.33 The authors described similar clinician impacts to those herein: moral distress, distress around end-of-life situations, and positive responses to limitation of occupational COVID-19 exposure. Unique to pediatrics, PICU clinicians witnessed trauma in the lone parent coping with their child’s critical illness and felt that family-centred values were threatened. Although other PICU-based studies have examined general sources of COVID-19-related clinician stress,21 the present study examined the effects of RFP policies specifically and its findings raise red flags about the potential for traumatic impact within the interprofessional clinical team.

Moral distress occurs when an individual feels they know the ethically correct course of action, but feel powerless to enact it.34 Participants experienced a moderate degree of moral distress, similar to studies of PICU nurses and physicians facing challenging clinical scenarios like treatment futility, perceived powerlessness, and inadequate team communication during baseline operations.35 Multiple organizational factors may affect the risk for moral distress such as relationships with management and care processes.36 Thus, it is relevant that participants who felt heard by management and those who perceived congruence with PICU values experienced less moral distress. Notably, nurses usually experience higher moral distress than staff physicians during routine operations,37 but it did not differ significantly in this setting. As decisions related to RFP were made by administrators outside the PICU,6 both nurses and physicians were placed in the same powerless situation of “moral hazard,” congruent with adult ICU studies,38 with attendant risks of moral injury, depersonalization, and abandonment of the profession.18,39

Most respondents reported an IES score > 26, a cited indication for psychological referral.29 For comparison, the mean (SD) for individuals experiencing cancer has been reported as 31.5 (17.8)40 and median [IQR] for otolaryngology physicians in high COVID-19 prevalence regions as 17.0 [5.0–28.0].41 The most commonly cited impactful events were those counter to key elements of FCC9,13 and PICU values. Pediatric intensive care unit trainees/fellows/clinical associates/nurse practitioners had lower mean IES scores than other professions except staff physicians. This is consistent with studies comparing distress for physicians and nurses during an epidemic-pandemic42 and may have been influenced by decisional capacity and ability to leave the bedside.43 Nevertheless, predictions of human reactions are complex and identified factors will only explain a portion of the clinician distress.

Restrictions did not significantly increase most clinicians’ workload as it did for their adult counterparts.44 Increases were experienced mostly to negotiate and advocate for policy exceptions for end-of-life care2 and beyond, with resulting suggestions to formalize an equitable exceptions process for future policy. We postulate that the absolute PICU-FPI change from prepandemic to pandemic did not correlate with the degree of moral distress, stress, or traumatic stress because individuals experienced stress from limitations to presence and family centredness irrespective of the degree of change. We hypothesize that the weak correlation between IES scores and perceived change in stress was because IES examines current symptoms of avoidance and intrusion related to one event while our stress measure asked participants to reflect on change in stress from RFP in its entirety. It is possible that distress may have waned at the time of survey completion.

The high mean scores reported for mental wellbeing indices are worrisome. Provisions are needed to support clinicians in managing the psychological burden associated with implementing policies and practices that are counter to clinician-identified PICU values.39 Involving frontline clinicians in future policy development and implementation is feasible and was desired by respondents, and may be an essential preventative action to ensure a stable and healthy workforce.45

Our results are limited by the inability to estimate the size of the interprofessional PICU workforce, with a resulting unknown response rate. There is a risk of response bias, whereby respondents who had the most impactful experiences were the most likely to reply, and of recall bias with responses impacted by recent events or by attenuation of memories and emotions over time or clinicians’ overall mental health during the pandemic. Our survey showed significant attrition, which may be related to its length and requests for free-text responses. As respondents had unrestricted access to the survey, it is possible that some answered the survey more than once, and that respondents who opened the survey multiple times without completing it may have inflated attrition. Although restrictions to presence were implemented globally,3 the cultural and social contexts of our findings may not be generalizable outside North America. Finally, we sought perceptions and opinions from early in the pandemic when restrictions were the most severe; accordingly, these results do not represent policy evolution throughout the pandemic.

Study strengths include the use of validated tools and rigorous survey development methodology with a multidisciplinary team that included patient partners and hospital leadership. The sample had robust geographic representation including most Canadian PICUs and units operating in French and English, and respondents showed both negative and affirmative policy impressions.

Conclusions

Restricted family presence policies in Canadian PICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic increased stress and resulted in mental health impacts on clinicians, including moderate levels of moral distress and trauma-associated distress. Restrictions to family presence place the wellbeing and functioning of the multidisciplinary team at risk. Ensuring policies are consistent and developed with frontline clinician input may decrease negative effects on clinicians.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (PDF 487 KB)

eAppendix 1 A Consensus-based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). eAppendix 2 RFP-PICU Healthcare Provider IMPACT Survey. eAppendix 3 Pediatric Intensive Care Unit-Family Presence Index (PICU-FPI). eAppendix 4 Comparison of demographics for respondents who experienced restrictions and were included in the complete analysis and those who did not experience restrictions and were not included in the full analysis. Demographic variables are consolidated to preserve cell sizes ≥ 5. eAppendix 5 PICU clinician opinions about future policy*. *Response to question: for future pandemic waves, what should go into a policy related to family visitation and presence in the PICU?

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Jennifer R. Foster, Laurie A. Lee, and Daniel Garros conceived of the study. Jennifer R. Foster, Laurie A. Lee, Daniel Garros, Jamie A. Seabrook, Corey Slumkoski, Martha Walls, Laura J. Betts, Stacy A. Burgess, and Neda Moghadam and the CCCTG designed the study and questionnaire. Daniel Garros, Jennifer R. Foster, and Laurie A. Lee acquired and cleaned the data. Jamie A. Seabrook, Jennifer R. Foster, Laurie A. Lee, and Molly Ryan performed the data analysis. All team members participated in data interpretation. All authors including members of the CCCTG reviewed and provided substantial input to the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Mlle. Marie-Dominique Léger RN, Mr. Marco Arquilla, and Mme. Cathy Frechette RN for providing survey translation/back translation; Mr. Marc Hall for creating the online version of the survey, and Dr. Karen Choong MD MSc and Dr. Stephana Moss PhD for their critical review of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This study was supported by a grant from IWK Health (#1025925) and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (funding reference number, 174916). The funding agencies were not involved in the design, data collection and analysis, manuscript writing, or decisions to publish the scientific work. No honoraria, grants, or payments were received to perform the research or produce the manuscript.

Prior conference presentations

Portions of this manuscript have been previously presented in abstract form at the 11th Congress of the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies (12–16 July 2022, Cape Town, South Africa).

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Patricia S. Fontela, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hafner K. 'A heart-wrenching thing’: hospital bans on visits devastate families, 2020. Available from URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/29/health/coronavirus-hospital-visit-ban.html (accessed March 2023).

- 2.Moss SJ, Krewulak KD, Stelfox HT, et al. Restricted visitation policies in acute care settings during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Crit Care. 2021;25:347. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03763-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camporesi A, Zanin A, Kanaris C, Gemma M, Soares Lanziotti V. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on pediatric intensive care units (PICUs) visiting policies: a worldwide survey. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2021;11:e2020000786. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1739263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vance AJ, Duy J, Laventhal N, Iwashyna TJ, Costa DK. Visitor guidelines in US children’s hospitals during COVID-19. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11:E83–E89. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-005772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahoney AD, White RD, Velasquez A, Barrett TS, Clark RH, Ahmad KA. Impact of restrictions on parental presence in neonatal intensive care units related to coronavirus disease 2019. J Perinatol. 2020;40:36–46. doi: 10.1038/s41372-020-0753-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Foster JR, Lee LA, Seabrook JA, et al. Family presence in Canadian PICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods environmental scan of policy and practice. CMAJ Open. 2022;10:E622–E632. doi: 10.9778/cmajo.20210202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koller DF, Nicholas DB, Goldie RS, Gearing R, Selkirk EK. When family-centered care is challenged by infectious disease: pediatric health care delivery during the SARS outbreaks. Qual Health Res. 2006;16:47–60. doi: 10.1177/1049732305284010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rogers S. Why can’t I visit? The ethics of visitation restrictions - lessons learned from SARS. Crit Care. 2004;8:300–302. doi: 10.1186/cc2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davidson JE, Aslakson RA, Long AC, et al. Guidelines for family-centered care in the neonatal, pediatric, and adult ICU. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:103–128. doi: 10.1097/ccm.0000000000002169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roth A, Rapoport A, Widger K, Friedman JN. General paediatric inpatient deaths over a 15-year period. Paediatr Child Health. 2017;22:80–83. doi: 10.1093/pch/pxx005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jee RA, Shepherd JR, Boyles CE, Marsh MJ, Thomas PW, Ross OC. Evaluation and comparison of parental needs, stressors, and coping strategies in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2012;13:166–172. doi: 10.1097/pcc.0b013e31823893ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stremler R, Haddad S, Pullenayegum E, Parshuram C. Psychological outcomes in parents of critically ill hospitalized children. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;34:36–43. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards C, Starks H, O’Connor MR, Doorenbos AZ. Elements of family-centered care in the pediatric intensive care unit: an integrative review. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2017;19:238–246. doi: 10.1097/njh.0000000000000335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denis-Larocque G, Williams K, St-Sauveur I, Ruddy M, Rennick J. Nurses’ perceptions of caring for parents of children with chronic medical complexity in the pediatric intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2017;43:149–155. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2017.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uhm JY, Kim HS. Impact of the mother–nurse partnership programme on mother and infant outcomes in paediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2019;50:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2018.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley L, Christian M, Gaiteiro R, Parshuram CS, Watson S, Dryden-Palmer K. The relationship between pediatric critical care nurse burnout and attitudes about engaging with patients and families. Can J Crit Care Nurs. 2019;30:22–28. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chou CM, Kellom K, Shea JA. Attitudes and habits of highly humanistic physicians. Acad Med. 2014;89:1252–1258. doi: 10.1097/acm.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall MF, Epstein EG. Moral hazard and moral distress: a marriage made in purgatory. Am J Bio. 2016;16:46–48. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2016.1181895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tedesco B, Borgese G, Cracco U, Casarotto P, Zanin A. Challenges to delivering family-centred care during the Coronavirus pandemic: voices of Italian paediatric intensive care unit nurses. Nurs Crit Care. 2021;26:10–12. doi: 10.1111/nicc.12578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Brien JM, Bae FA, Kawchuk J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 visitor restrictions on healthcare providers in Canadian intensive care units: a national cross-sectional survey. Can J Anesth. 2022;69:278–280. doi: 10.1007/s12630-021-02139-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balistreri K, Lim P, Tager J, et al. “It has added another layer of stress”: COVID-19’s impact in the PICU. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11:e226–e234. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2021-005902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sharma A, Minh Duc NT, Lam Thang TL, et al. A consensus-based checklist for reporting of survey studies (CROSS) J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36:3179–3187. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06737-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burns KEA, Duffett M, Kho ME, et al. A guide for the design and conduct of self-administered surveys of clinicians. CMAJ. 2008;179:245–252. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller L, Richard M, Krmpotic K, et al. Parental presence at the bedside of critically ill children in the pediatric intensive care unit: a scoping review. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;181:823–831. doi: 10.1007/s00431-021-04279-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wocial LD, Weaver MT. Development and psychometric testing of a new tool for detecting moral distress: the moral distress thermometer. J Adv Nurs. 2013;69:167–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horowitz M, Wilner N, Alvarez W. Impact of event scale: a measure of subjective stress. Psychosom Med. 1979;41:209–218. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundin EC, Horowitz MJ. Impact of event scale: psychometric properties. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:205–209. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richmond TS, Kauder D. Predictors of psychological distress following serious injury. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:681–692. doi: 10.1023/a:1007866318207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sterling M. The impact of event scale (IES): commentary. Aust J Physiother. 2008;54:78. doi: 10.1016/s0004-9514(08)70074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee L, Seabrook J, Garros D, et al. Parent/carer presence on medical ward rounds: opinions of parents/carers and healtchare staff in tertiary paediatric critical care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2022; 23. 10.1097/01.pcc.0000901152.16312.10

- 31.Thomas DR. A General inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27:237–246. doi: 10.1177/1098214005283748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iness AN, Abaricia JO, Sawadogo W, et al. The effect of hospital visitor policies on patients, their visitors, and health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Am J Med. 2022;135:1158–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2022.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall MF, Epstein EG. Moral hazard and moral distress: a marriage made in purgatory. Am J Bioeth. 2016;16:46–48. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2016.1181895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wocial L, Ackerman V, Leland B, et al. Pediatric ethics and communication excellence (PEACE) rounds: decreasing moral distress and patient length of stay in the PICU. HEC Forum. 2017;29:75–91. doi: 10.1007/s10730-016-9313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wall S, Austin WJ, Garros D. Organizational influences on health professionals’ experiences of moral distress in PICUs. HEC Forum. 2016;28:53–67. doi: 10.1007/s10730-015-9266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prentice T, Janvier A, Gillam L, Davis PG. Moral distress within neonatal and paediatric intensive care units: a systematic review. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:701–708. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2015-309410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Azoulay E, Cariou A, Bruneel F, et al. Symptoms of anxiety, depression, and peritraumatic dissociation in critical care clinicians managing patients with COVID-19 a cross-sectional study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202:1388–1398. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2568oc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dean W, Talbot SG, Caplan A. Clarifying the language of clinician distress. JAMA. 2020;323:923–924. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.21576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salsman JM, Schalet BD, Andrykowski MA, Cella D. The impact of events scale: a comparison of frequency versus severity approaches to measuring cancer-specific distress. Psychooncology. 2015;24:1738–1745. doi: 10.1002/pon.3784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Civantos AM, Byrnes Y, Chang C, et al. Mental health among otolaryngology resident and attending physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: national study. Head Neck. 2020;42:1597–1609. doi: 10.1002/hed.26292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Preti E, Di Mattei V, Perego G, et al. The psychological impact of epidemic and pandemic outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review of the evidence. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2020;22:43. doi: 10.1007/s11920-020-01166-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dryden-Palmer K, Moore G, McNeil C, et al. Moral distress of clinicians in Canadian pediatric and neonatal ICUs. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020;21:314–323. doi: 10.1097/pcc.0000000000002189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mehta S, Machado F, Kwizera A, et al. COVID-19: a heavy toll on health-care workers. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9:226–228. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00068-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Garros D, Austin WJ, Carnevale FA. Moral distress in pediatric intensive care. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:885–886. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file1 (PDF 487 KB)

eAppendix 1 A Consensus-based Checklist for Reporting of Survey Studies (CROSS). eAppendix 2 RFP-PICU Healthcare Provider IMPACT Survey. eAppendix 3 Pediatric Intensive Care Unit-Family Presence Index (PICU-FPI). eAppendix 4 Comparison of demographics for respondents who experienced restrictions and were included in the complete analysis and those who did not experience restrictions and were not included in the full analysis. Demographic variables are consolidated to preserve cell sizes ≥ 5. eAppendix 5 PICU clinician opinions about future policy*. *Response to question: for future pandemic waves, what should go into a policy related to family visitation and presence in the PICU?