Abstract

Background

Brief interventions involve a time‐limited intervention focusing on changing behaviour. They are often motivational in nature using counselling skills to encourage a reduction in alcohol consumption.

Objectives

To determine whether brief interventions reduce alcohol consumption and improve outcomes for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital inpatient units.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Drug and Alcohol Group Register of Trials (March 2011) the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library March 2011), MEDLINE January 1966‐March 2011, CINAHL 1982‐March 2011, EMBASE 1980‐March 2011 and www.clinicaltrials.gov to April 2011 and performed some relevant handsearching.

Selection criteria

All prospective randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials were eligible for inclusion. Participants were adults and adolescents (16 years or older) admitted to general inpatient hospital care for any reason other than specifically for alcohol treatment and received brief interventions (of up to 3 sessions) compared to no or usual care.

Data collection and analysis

Three reviewers independently selected the studies and extracted data. Where appropriate random effects meta‐analysis and sensitivity analysis were performed.

Main results

Forteen studies involving 4041 mainly male participants were included. Our results demonstrate that patients receiving brief interventions have a greater reduction in alcohol consumption compared to those in control groups at six month, MD ‐69.43 (95% CI ‐128.14 to ‐10.72) and nine months follow up, MD ‐182.88 (95% CI ‐360.00 to ‐5.76) but this is not maintained at one year. Self reports of reduction of alcohol consumption at 1 year were found in favour of brief interventions, SMD ‐0.26 (95% CI ‐0.50 to ‐0.03). In addition there were significantly fewer deaths in the groups receiving brief interventions than in control groups at 6 months, RR 0.42 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.94) and one year follow up, RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.91). Furthermore screening, asking participants about their drinking patterns, may also have a positive impact on alcohol consumption levels and changes in drinking behaviour.

Authors' conclusions

The main results of this review indicate that there are benefits to delivering brief interventions to heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards in terms of reduction in alcohol consumption and death rates. However, these findings are based on studies involving mainly male participants. Further research is required determine the optimal content and treatment exposure of brief interventions within general hospital settings and whether they are likely to be more successful in patients with certain characteristics.

Plain language summary

Brief interventions for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards

Heavy or dangerous patterns of drinking alcohol can lead to accidents, injuries, physical and psychiatric illnesses, frequent sickness, absence from employment and social problems. Long term alcohol consumption has harmful effects on almost all organs of the body, particularly the brain and gastro‐intestinal system. Healthcare professionals have the opportunity to ask people about how much alcohol they drink and offer brief interventions to heavy drinkers. These brief interventions involve a time limited intervention focusing on changing behaviour. They range from a single session providing information and advice to one to three sessions of motivational interviewing or skills‐based counselling involving feedback and discussion on responsibility and self efficacy. Different health professionals who do not require to be alcohol specialists may give the intervention. Admission to hospital as an inpatient, in general medical wards and trauma centres, provides an opportunity whereby heavy alcohol users are accessible, have time for an intervention, and may be made aware of any links between their hospitalisation and alcohol. The review authors identified 14 randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials involving 4041 mainly male adults (16 years or older) identified as heavy drinkers in hospital, mainly in the UK and USA.

The main results of this review indicate that there are benefits to delivering brief interventions to heavy alcohol users in general hospital. Our results demonstrate that patients receiving brief interventions have a greater reduction in alcohol consumption compared to those in control groups at six month and nine month follow up but this is not maintained at one year. In addition there were significantly fewer deaths in the groups receiving brief interventions than in control groups at 6 months and one year. However, these findings are based on studies involving mainly male participants. Furthermore screening, asking participants about their drinking patterns, may also have a positive impact on alcohol consumption levels and changes in drinking behaviour and this is an area that requires further investigation.

Further research is required determine the optimal content and treatment exposure of brief interventions within general hospital settings and whether they are likely to be more successful in patients with certain characteristics.

Background

Description of the condition

Around two billion people world wide consume alcoholic beverages and over 76 million people have alcohol use disorders (Lancet 2009). Alcohol is responsible for about 2.3 million premature deaths world wide (Cherpitel 2009). Sufficient evidence exists to indicate that alcohol is a significant threat to world health, with dangerous patterns of heavy drinking existing in most countries. Hazardous and harmful use of alcohol is a major contributing factor of ill health globally through alcohol dependence, liver cirrhosis, cancers and injuries and to others through dangerous actions of those intoxicated such as drink driving and violence or through the impact of drinking on fetus and child development (WHO 2011). World wide alcohol is linked to 2.5 million deaths (3.8% of total) per annum with global alcohol consumption continuing to increase (WHO 2008).Clinical and epidemiological studies report a relationship between heavy drinking and certain clinical presentations such as injuries, physical and psychiatric illnesses, frequent sickness, absence from employment and social problems. The consequences of harmful alcohol use is a major concern to health care services with approximately 4.5% of the global burden of disease and injury attributable to alcohol (WHO 2011). During peak times around 41% of all attendees at UK Accident & Emergency departments test positive for alcohol consumption (Dobson 2003). In the UK the number of alcohol‐attributable hospital admissions for 2005‐2006 was 909 per 100,000 men and 510.4 per 100,000 women (NICE 2008).

Levels of heavy alcohol consumption have been widely defined into three categories: hazardous drinking, harmful drinking and alcohol dependence determined by the amount of alcohol consumed, together with the physical and psychological consequences (Kaner 2007). A large proportion of alcohol attributed morbidity and mortality in a population is as a result of large numbers of people with hazardous and harmful consumption (Freemantle 1993). Binge drinking is defined as an episode of excessive drinking primarily with the intention of becoming intoxicated (Renaud 2001). There is currently no consensus world wide on how many drinks consist of a 'binge'. Binge drinking is considered harmful, regardless of a person's age, and there have been calls for healthcare professionals to give increased attention to their patients drinking habits, especially binge drinkers. In the USA, the term is often taken to mean consuming five or more standard drinks (male), or four or more drinks (female), in about two hours for a typical adult (Moreira 2009). In the United Kingdom, binge drinking is defined as drinking more than twice the daily limit, that is, drinking eight units (64 grams) or more for men or six units (48 grams) or more for women on one occasion (Stephans 2008).

Long term alcohol consumption has a harmful effect on almost all organs of the body, particularly the brain and gastro‐intestinal system (Hillman 2003). Alcohol consumption has also been linked with injuries and morbidity sustained through motor vehicle crashes, falls, drowning, fires, burns and violence. Alcohol is estimated to contribute to 20‐30% worldwide oesophageal cancer, liver cancer, cirrhosis of the liver, homicide and epilepsy (WHO 2010). Its consumption is causally linked to a problems, including health issues and lower life expectancy, reduced workplace productivity, accidents, drink driving, violence and other forms of crime (Collins 2008). It is estimated that each alcoholic negatively affects an average of four other people(Scottish Government 2008).

The world's highest alcohol consumption levels are found in the developed world, including western and eastern Europe, but alcohol consumption is increasing rapidly in Africa and Asia (WHO 2011). The annual cost of alcohol abuse to the NHS in the UK is around £1.7 billion, incurring more direct costs to health, social and criminal justice systems than drug misuse, alzheimer's disease, schizophrenia or stroke, (AMS 2004). In Australia alcohol has been defined as a serious problem whose social costs in 2004/05 have been estimated to be over $15 billion (Australian Government 2008) . Alcohol dependence and alcohol related diagnosis have been rising among patients discharged from General Hospitals (Scottish Executive 2003; Williams 2010). Unhealthy alcohol misuse is increasingly common in medical inpatients (Williams 2010).

Description of the intervention

Health professionals working in general hospital environments have regular contact with individuals who abuse alcohol. Research suggests that a high number of patients who attend general hospitals experience alcohol related problems, often unrelated to the conditions with which they attend for treatment (Saunders 1999; Watson 2000). Traditionally interventions were offered only when individuals were diagnosed as alcohol dependent, though recent evidence has suggested possible benefits from intervening earlier using screening and brief interventions (Nilsen 2008b; Wilk 1997). For health care professionals there is now much more expectation for them to identify and provide interventions when alcohol consumption exceeds recommended limits, where there is increased risk of physical, psychological and social harm (Nilsen 2008a). Opportunities exist for health care professionals to routinely ask about alcohol consumption levels as part of their assessment, and offer brief interventions to those exceeding safe levels of alcohol consumption. An important element of brief interventions are that they can be delivered by non‐specialist staff. Due to the minimal time taken to deliver a brief intervention and the simple training required to up skill health professionals in this area brief interventions are not resource intensive with admission to hospital cited as a potentially opportune time for intervention for those whose alcohol consumption exceeds safe recommended limits (Williams 2010). A brief intervention generally consists of between one and four short 5‐20 minute counselling sessions with a trained health care worker for example a nurse, occupational therapist, physician, psychologist or social worker.

Brief interventions are targeted at non‐treatment seeking, non‐alcohol dependent hazardous and harmful drinkers and are intended as an early intervention (Nilsen 2010). Brief interventions consist of more than just advice on reducing alcohol consumption and focus more personally on the individual drawing on theories from person centred counselling and social psychology being motivational in nature through focusing on the benefits and drawbacks of behaviour change (McQueen 2006). They involve a time limited intervention and can range from five to ten minutes of information and advice to two or more sessions of motivational interviewing or counselling (Alcohol Concern 2001). Previous work has evaluated a range of interventions categorised as brief interventions, with six key elements of brief interventions being widely summarised under the acronym FRAMES: feedback, responsibility, advice, menu of strategies, empathy and self efficacy originally described by (Bien 1993; Miller 1994).

Brief interventions are important for non‐dependent heavy alcohol users in primary care where they have been shown to reduce total alcohol consumption, and binge drinking in hazardous drinkers for up to one year SIGN 2003. This is particularly important in limiting the progression of alcohol related pathologies such as alcohol dependence and limiting the damage that prolonged heavy drinking has to physical and mental health.

Why it is important to do this review

A Cochrane review has indicated benefits from brief interventions in primary care (Kaner 2007) but the effectiveness of brief intervention in hospital inpatient environments remained unclear. Admission to hospital represents an opportunity where by heavy alcohol users are accessible, have time for an intervention and may be made aware of any links between their hospitalisation and alcohol (Saitz 2007). The acute post traumatic period may act as a catalyst for change representing a teachable moment to encourage heavy alcohol users to change (Soderstrom 2007; Sommers 2006). A previous review and meta‐analysis of brief interventions in the general hospital setting found evidence for effectiveness to be inconclusive (Emmen 2004). This review is justified as the accumulation of fresh evidence through the inclusion of a further nine studies. If health professionals are to implement such interventions into practice then evidence on it's effectiveness and long term benefits is required.

Objectives

To determine whether brief interventions reduce alcohol consumption and improve outcomes for heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital inpatient units not specifically for alcohol treatment. Specific questions to be answered:

Do brief interventions with heavy alcohol users admitted to general hospital wards:

Impact on alcohol consumption levels?

Improve quality of life and ability to function in society i.e. social relationships, employment, education?

Lead to a reduction in hospital re‐admission rates, and or alcohol related injuries i.e. falls, violence, suicide and motor vehicle accidents?

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All prospective randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials which provided an appropriate control arm including assessment only (screening) or treatment as usual including provision of leaflets (on which to base comparisons) were eligible for inclusion. Studies with two or more active intervention arms when compared with a control arm were included. Studies without a control arm were not included.

Types of participants

We considered trials that included adults and adolescents (people 16 years and older) admitted to general inpatient hospital care for any reason other than specifically for alcohol treatment, where inclusion criteria for the study identified participants as regularly consuming alcohol above the recommended safe weekly/daily amounts for the country in which the study took place i.e. (ICAP 2003).

For the purposes of this review general hospital wards were taken to include all hospital inpatient units that were not identified as psychiatric or addiction services. This covered a broad range of possible presenting problems and treatment environments. All participants received usual treatment for their presenting medical condition.

Types of interventions

A brief intervention was defined as a single session or up to three sessions involving an individual patient and health care practitioner comprising information and advice, often using counselling type skills to encourage a reduction in alcohol consumption and related problems.

Control groups were defined as assessment only (screening) or treatment as usual including provision of leaflets.

The following comparison have been considered

(1) Brief intervention(s) versus control (assessment/no‐intervention or standard treatment)

Originally in the protocol it was stated that we would include a comparison of brief interventions versus extended psychological intervention. The search strategy identified only one such study within the general hospital setting (Soderstrom 2007). Based on feedback from the review group it was deemed appropriate to exclude this study.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

To be eligible for inclusion studies must have measured alcohol consumption by:

self report data (e.g. number of drinks per drinking day, average consumption and or number of drinking occasions per specified time period obtained through interview, drinking diary, alcohol consumption tests e.g. FAST (Hodgson 2002), AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test WHO 1989), MAST (Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test Selzer 1971).

laboratory markers e.g. blood or saliva alcohol consumption tests

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included:

Hospital re‐admission rates

Mortality rates

Alcohol related injuries

Quality of life (using standardised tools)

Reduction in sickness absence from work related tasks including paid employment, voluntary work, education

Reduction in adverse legal events as a consequence of alcohol i.e. violence, driving offences.

Need for institutional care

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Library (March 2011), which includes the Cochrane Drug and Alcohol Group Register of Trials, MEDLINE (January 1966‐March 2011), CINAHL (1982‐March 2011) and EMBASE (1980‐June 2008). See Appendix 1, Appendix 2, Appendix 3, Appendix 4 with the detailed search strategies.

Searching other resources

Hand searching of relevant journals not included in the Cochrane library was also undertaken together with the register of clinical trials and conference abstracts to locate any additional studies.We hand searched two journals (Addiction, Alcohol and Alcoholism). Unpublished reports, abstract, brief and preliminary reports were considered for inclusion on the same basis as published reports.

We searched: 1) the reference lists of all relevant papers to identify further studies. 2) some of the main electronic sources of ongoing trials (National Research Register, meta‐Register of Controlled Trials; Clinicaltrials.gov) 3) conference proceedings likely to contain trials relevant to the review. We contacted investigators seeking information about unpublished or incomplete trials.

All searches included non‐English language literature and studies with English abstracts were assessed for inclusion. When considered likely to meet inclusion criteria, studies were translated.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Pairs of authors read all titles/and or abstracts resulting from the search process and eliminated any obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained full copies of the remaining potentially relevant studies. Pairs of authors acting independently classified these as clearly relevant that is, met all inclusion criteria therefore include, or clearly irrelevant therefore exclude, or insufficient information to make a decision, whereby contact was made with the authors for further information to aid the decision process. Decisions were based on inclusion criteria outlined i.e. types of studies, types of participants, interventions and outcome measures used. Differences in opinion were resolved through consensus or referral to a third author. Studies formally considered are listed and reasons for exclusion given in the characteristics of excluded studies.

Data extraction and management

Three authors independently extracted data from published sources using a piloted data recording form. Data extraction forms were piloted using a representative sample of studies and inter‐rater reliability was checked for the recording of outcome data and quality assessment and appropriate changes made to the data collection form. Where differences in data extracted occurred this was resolved through discussion, decisions that could not easily be resolved were referred to a fourth author. Where required additional information was obtained through collaboration with the original authors.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias as described in chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 5.0.1 (Higgins 2008) was used for assessing risk of bias in studies. This two part tool addresses five specific domains, sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, with the first part describing what was supposed to have happened in the study and the second assigning a judgement in relation to the risk of bias for that study. Three authors independently assessed the following: sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, blinding of participant and outcome assessor. The first part of the tool involves describing what was reported to have happened in the study. The second part of the tool involves assigning a judgement, in terms of "low ", "high" or unclear, relating to the risk of bias for that entry. Criteria indicated by the handbook and adapted to the addiction field were used to make these judgements see Appendix 5. Any disagreement between authors was resolved by discussion, including input from a third independent reviewer if required.

Measures of treatment effect

Where available and appropriate, quantitative data for the outcomes listed in the inclusion criteria are presented in the analysis tables (1.1 to 1.13). Where studies reported standard errors of the means (SEMs), standard deviations were obtained by multiplying standard errors of means by the square‐root of the sample size. For each trial, relative risk and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for dichotomous outcomes, and weighted mean differences (WMD) and 95% confidence intervals calculated for continuous outcomes (reporting mean and standard deviation or standard error of the mean). Standardised mean differences (SMD) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated when combining results from studies using different ways of measuring the same concept. Change scores have been reported separately as these cannot be incorporated into meta analyses of standardised mean differences.

For each study reporting quantity of alcohol consumed in a specific time period data was converted into grams per week using either the conversion factor reported in the paper or appropriate to the country where the trial took place (Miller 1991). Months were converted to weeks by multiplying 52/12.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between comparable trials was tested using a standard chi‐squared test and considered statistically significant at P < 0.1 after due consideration of the value of I squared.

Data synthesis

Where possible, we pooled results of similar studies, for continuous and dichotomous outcomes. Due to the nature of this review there was some degree of heterogeneity in the type of interventions offered, outcome measures reported and methodological quality therefore it was inappropriate to combine studies

Where appropriate, results of comparable groups of studies were pooled using the fixed effect model and 95% confidence intervals calculated. In the presence of heterogeneity the results of comparable groups of trials were pooled using the random effect model and 95% confidence intervals calculated.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was undertaken using random effects model when there was substantial heterogeneity P < 0.1 after due consideration of the value of I squared. Studies were removed if they included additional follow up care or group data was removed when initial analysis included pooled data from two groups. Due to the small number of studies included in each meta‐analysis it was not possible to conduct a sensitivity analysis based on method of randomisation, concealment of allocation, intention to treat analysis and blinding of assessors and types of treatment provided i.e. content, number and length of session, and number of patients involved.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

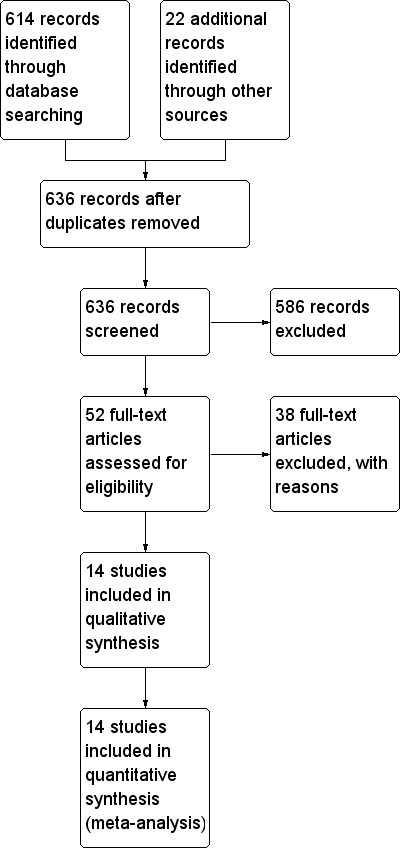

The electronic searching resulted in 614 potentially relevant studies which were screened by reviewing titles and abstracts An additional 22 potentially relevant studies were located through searching reference lists of included and excluded studies and handsearching relevant journal. Three authors (JM, LA, DM) eliminated 586 obviously irrelevant studies based on titles and where available abstracts, leaving 52 potentially relevant studies. Four independent authors (JM, LA, DM, FC) read the abstracts and full text for these 52 studies of these 38 were excluded Figure 1.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

14 relevant studies were identified as eligible to be included in this review (Antti‐Poika 1988; Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Gentilello 1999; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; Liu 2011; McManus 2003; McQueen 2006; Saitz 2007; Schermer 2006; Sommers 2006;Tsai 2009; Watson 1999.

Data from 14 studies are included in this review involving 4041 participants at entry. Descriptions of included studies can be found in Characteristics of included studies.

Countries where the studies were conducted Four studies took place in the United States (Gentilello 1999; Saitz 2007; Schermer 2006; Sommers 2006) five in the United Kingdom (Chick 1985; Holloway 2007; McManus 2003; McQueen 2006; Watson 1999) one in Australia (Heather 1996), one in Germany (Freyer‐Adam 2008), two in Tiawan (Liu 2011; Tsai 2009) and one in Finland (Antti‐Poika 1988).

Settings Six of the studies took place in general medical wards (Chick 1985, Freyer‐Adam 2008, Holloway 2007; McQueen 2006; McManus 2003; Saitz 2007), three in trauma centres (Gentilello 1999; Schermer 2006; Sommers 2006), two in a range of settings (Heather 1996; Watson 1999), one in a medical/surgical unit (Liu 2011; Tsai 2009) and one in an Orthopaedic and Trauma Centre (Antti‐Poika 1988).

Screening Seven studies used established alcohol screening tools such as the Short Michigan Alcoholism Screening Test (SMAST), Fast Alcohol Screening Tool (FAST), CAGE or AUDIT or other set criteria list (Antti‐Poika 1988; Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Gentilello 1999; McQueen 2006; Saitz 2007; Tsai 2009). Four used self reported alcohol consumption (Freyer‐Adam 2008; Heather 1996; McManus 2003; Watson 1999. One study used a retrospective drinking diary Holloway 2007, and one used a blood alcohol content greater than or equal to 10mg/dl following motor vehicle collision Sommers 2006. Control Control groups received usual care Antti‐Poika 1988; Chick 1985; Gentilello 1999; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; McManus 2003; Liu 2011; McQueen 2006Schermer 2006; Sommers 2006;Tsai 2009; Watson 1999;). One study provided usual care, screening and feedback on this (Saitz 2007). Brief intervention Brief interventions consisted of all, or any, of the following: self efficacy enhancement, skills based counselling, brief motivational counselling, brief advice, education leaflets, telephone calls, feedback letter. Ten studies evaluated a single brief intervention lasting between 15‐60 minutes (Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; Gentilello 1999; McQueen 2006; Saitz 2007; Schermer 2006; Tsai 2009; Watson 1999). Three studies evaluated two brief intervention sessions (Liu 2011; McManus 2003; Sommers 2006). One study evaluated two brief interventions delivered in hospital and follow up at outpatient clinic (Antti‐Poika 1988).

Intervention delivery Brief interventions were delivered by a variety of different health professionals, counsellors and social care workers. In five studies brief interventions were delivered by nurses (Chick 1985; Holloway 2007; Sommers 2006; Tsai 2009; Watson 1999). In a further three studies the intervention was delivered by a range of professionals a psychologist (Gentilello 1999), occupational therapists (McQueen 2006), alcohol counsellor (McManus 2003) and social workers (Liu 2011). The remaining five studies reported that individuals from more than one professional group delivered the intervention (Freyer‐Adam 2008), nurse and physicians (Antti‐Poika 1988), psychology graduate and nurse (Heather 1996), trained counsellor and PhD psychology students (Saitz 2007) and trauma surgeon or social worker (Schermer 2006).

Excluded studies

Of the possibly relevant studies identified 38 were excluded. Reasons for exclusion are summarised in the Characteristics of excluded studies table.

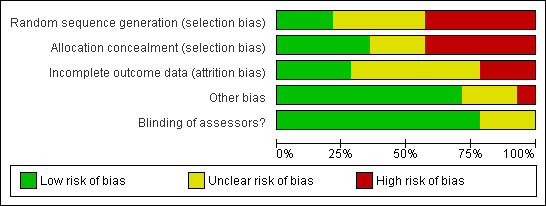

Risk of bias in included studies

Details of how and why the authors rated the included studies on the following criterion are provided in the Characteristics of included studies. Figure 2 provides a summary of overall risk of bias in the 14 studies as high, low or unclear. Figure 3 provides details of the judgments about each methodological quality item for each study.

2.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Allocation

Sequence generation Sequence generation/randomisation was deemed to be adequate in two studies using computer generated codes, off site data management or opaque sealed envelopes (Gentilello 1999; Liu 2011; Tsai 2009). In five studies the method of randomisation was unclear (Antti‐Poika 1988,McQueen 2006, Saitz 2007, Schermer 2006 and Sommers 2006). Five studies used either a block design whereby alternate wards acted as control or intervention site, this was rotated in a random pattern in four studies and in one the control and intervention ward remained static (Chick 1985; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; McManus 2003; Watson 1999). One study used time frame (date of admission) as the method of group allocation (Freyer‐Adam 2008).Therefore six studies were judged at high risk of selection bias because of inadequate sequence generation method.

Allocation concealment Allocation concealment was judged to be adequate in six studies (Gentilello 1999; Liu 2011; McQueen 2006; Saitz 2007; Schermer 2006; Tsai 2009). Inadequate allocation concealment was found in six studies (Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; McManus 2003; Watson 1999). Allocation concealment was unclear in two studies (Antti‐Poika 1988; Sommers 2006).

Blinding

Due to the nature of this intervention it is not possible to blind participants or staff providing the intervention. It is however possible to blind outcome assessors. In 11 studies the outcome assessors were blinded to the nature of the groups (Chick 1985; Gentilello 1999; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; Liu 2011; McManus 2003; McQueen 2006; Saitz 2007; Sommers 2006; Tsai 2009; Watson 1999). It was unclear in two studies Antti‐Poika 1988 and Schermer 2006 and in one study only 62% had a different assessor at follow up (Freyer‐Adam 2008).

Incomplete outcome data

Three of the 14 studies reported that an intention to treat analysis was undertaken (Holloway 2007; Liu 2011; Saitz 2007). In one study intention to treat was not appropriate as this study reported on police driving citation records and had no loss to follow up (Schermer 2006). Five trials did not use an intention to treat analysis (Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; McQueen 2006; Sommers 2006; Tsai 2009). In the remaining five studies it was unclear whether an intention to treat analysis was undertaken (Antti‐Poika 1988; Gentilello 1999; Heather 1996; McManus 2003; Watson 1999).

Other potential sources of bias

In one study Antti‐Poika 1988 the control and intervention groups were not similar at baseline in relation to mean alcohol consumption. In one study there were more medical patients than in other groups (Tsai 2009). No additional sources of bias were identified for the remaining 12 studies. It was not possible to look for the impact of risk of bias by sensitivity analysis due to limited number of comparable studies included in this review.

Effects of interventions

1 Brief intervention vs control (Figure 1.1 ‐ 1.10)

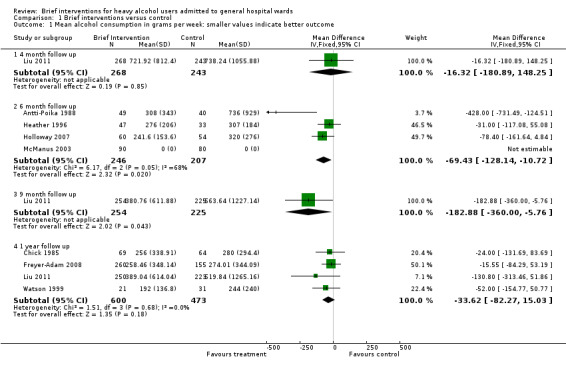

1.1 and 1.2 Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week and sensitivity analysis Eight studies involving 2196 participants at entry presented data on mean alcohol consumption in grams per week at four, six or nine months or one year follow up. One study reported outcomes at four and nine months (Liu 2011), four studies reported outcomes at six months (Antti‐Poika 1988; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; McManus 2003) and four studies reported outcomes at one year (Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Liu 2011; Watson 1999). Meta‐analysis of weighted mean differences showed a significant difference at six months follow up MD ‐69.43 (95% CI ‐128.14 to ‐10.72) and at nine months follow up MD ‐182.88 (95% CI ‐360.00 to ‐5.76) in favour of the brief intervention but no significant difference at one year follow up MD ‐33.62 (95% CI ‐82.27 to 15.03). For all seeAnalysis 1.1

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 1 Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week: smaller values indicate better outcome.

However there was significant heterogeneity I2=68%, P=0.05 in the four studies with outcomes at six months (Antti‐Poika 1988; Heather 1996; Holloway 2007; McManus 2003), therefore a sensitivity analysis was undertaken excluding (Antti‐Poika 1988) as this study included additional follow up care and assessors were not blinded. The result become not statistically significant but a trend MD ‐55.49 (95% CI ‐115.33 to 4.35), was observed towards consuming less grams of alcohol per week in those receiving the brief intervention compared with those in the control group. SeeAnalysis 1.2.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 2 Sensitivity analysis: Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week: smaller values indicate better outcome.

Furthermore in the original analysis of one year follow up we pooled data from two groups in one study Freyer‐Adam 2008 we therefore undertook a sensitivity analysis removing the physician delivered intervention group, the result did not change and there was still no significant difference between the groups MD ‐36.31(95% CI ‐86.64 to 14.01). SeeAnalysis 1.2.

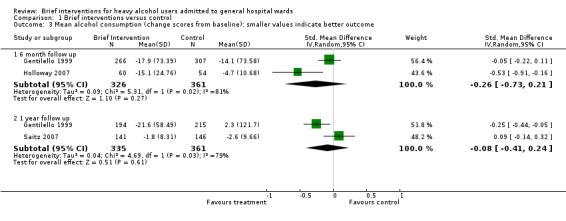

1.3 Mean alcohol consumption per week (change scores from baseline) Three studies involving 1318 participants at entry presented change score data on mean alcohol consumption per week. Two studies presented change scores at six month follow up Gentilello 1999; Holloway 2007 and two studies at one year follow up Gentilello 1999; Saitz 2007. Meta‐analysis using random effects model of standardised mean differences showed no significant difference at six months between brief intervention and control groups SMD ‐0.26 (95% CI ‐0.73 to 0.21). A meta‐analysis of standardised mean differences at one year follow up showed no significant difference between the groups SMD ‐0.08 (95% CI ‐0.41 to 0.24). For both seeAnalysis 1.3.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 3 Mean alcohol consumption (change scores from baseline): smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.4 Self reports of alcohol consumption methods of alcohol consumption (using outcome tools and face to face interviews) Three studies involving 603 participants at entry presented self reports of alcohol consumption, FAST (McQueen 2006), AUDIT (Tsai 2009), and face to face interviews (Heather 1996). Standardised mean difference at follow up points of 3 and 6 months showed no significant difference between control and brief intervention. However there was a significant difference at one year follow up with a reduction in participants' self report of alcohol consumption in the brief intervention group, SMD ‐ 0.26 (95% CI ‐0.50 to ‐0.03), seeAnalysis 1.4).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 4 Self reports of alcohol consumption (smaller values indicate better outcome).

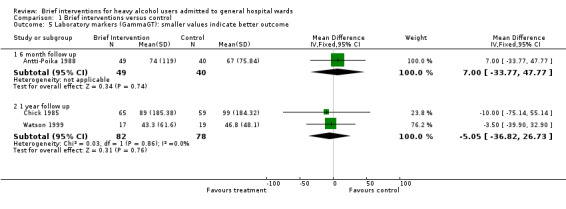

1.5 Laboratory markers (GammaGT) Three studies involving 426 participants at entry presented Gamma GT results Antti‐Poika 1988; Chick 1985; Watson 2000, with follow up points of six months Antti‐Poika 1988 and one year Chick 1985; Watson 1999. Meta‐analysis of weighted mean difference showed no significant difference between control and brief intervention. Six month follow up WMD 7.00 (95% CI ‐34 to 48), one year follow up, WMD ‐5.05 (95% CI ‐37 to 27), seeAnalysis 1.5.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 5 Laboratory markers (GammaGT): smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.6 Number of binges Only one study involving 341 participants at entry presented data on number of binges (Saitz 2007), no significant differences in number of binges was observed between control and brief intervention groups RR 0.99 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.19), seeAnalysis 1.6.

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 6 Number of binges: smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.7 Heavy drinking episodes (days per week)

One study (Liu 2011) involving 616 participants presented data on this outcome at four, nine and 12 months follow up. Significant differences were observed in favour of the brief intervention group at all time points, MD ‐0.56 (95% CI ‐1.02 to ‐0.10); MD ‐0.78 (95% CI ‐1.32 to ‐0.24); MD ‐0.71 (95% CI ‐1.26 to ‐0.16) days per week respectively, seeAnalysis 1.7

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 7 Heavy drinking episodes (days per week): smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.8 and 1.9 Death and sensitivity analysis Nine studies reported death involving a total of 3256 participants at entry. Follow up at 3 months McQueen 2006; 4 months Liu 2011; 6 months Gentilello 1999; McManus 2003; Sommers 2006; Tsai 2009, 9 months Liu 2011 and follow up at one year Chick 1985; Freyer‐Adam 2008; Gentilello 1999; Liu 2011; Saitz 2007; Sommers 2006; Tsai 2009; There were no significant differences in number deaths between control and brief intervention at three, four or nine months follow up. However there was a significant difference at 6 months, RR 0.42 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.94) and one year, RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.91) with less deaths in the brief intervention groups than control groups. For all seeAnalysis 1.8.

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 8 Death: smaller values indicate better outcome.

In the original analysis of one year follow up we pooled data from two groups in one study Freyer‐Adam 2008 we therefore undertook a sensitivity analysis removing the physician delivered intervention group there was still a significant difference between the groups, RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.96) with less deaths in the brief intervention group than control group, seeAnalysis 1.9.

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 9 Sensitivity analysis: Death: smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.10 Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week restricted to studies including only men Four studies included men only (Antti‐Poika 1988; Chick 1985; Heather 1996; Liu 2011) involving a total of 1066 participants. Meta‐analysis of these studies for data at four, six and twelve months follow up showed no significant difference between brief intervention and control with substantial heterogeneity between studies. However there was a significant difference at nine months follow up, MD ‐182.88 (95% CI ‐360.00 to ‐5.76) grams per week in favour of brief intervention but this was data from only one study (Liu 2011), seeAnalysis 1.10.

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 10 Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week restricted to studies including only men: smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.11 Driving Offences One study involving 126 participants presented data on number of driving offences within a three year follow up period (Schermer 2006). This showed promising but not statistically significant reduction in driving offences in favour of those who received brief intervention , RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.22 to 1.19), seeAnalysis 1.11.

1.11. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 11 Driving offences within 3 years: smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.12 Number of days hospitalised in previous 3 months

One study (Liu 2011) involving 616 participants presented data on this outcome at four, nine and 12 months follow up. No significant differences were observed at any time point, seeAnalysis 1.12.

1.12. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 12 Number of days hospitalised in previous 3 months: smaller values indicate better outcome.

1.13 A&E visits in previous 3 months

One study (Liu 2011) involving 616 participants presented data on this outcome at four, nine and 12 months follow up. No significant differences were observed at any time point, seeAnalysis 1.13.

1.13. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Brief interventions versus control, Outcome 13 A&E visits in previous 3 months: smaller values indicate better outcome.

Discussion

Summary of main results

This systematic review assessed the effectiveness of brief interventions on alcohol consumption and other outcomes (death, driving offences, number of days hospitalised, accident and emergency visits and laboratory markers i.e. Gamma GT), for adults with heavy alcohol use admitted to general hospital wards not specifically for alcohol treatment. Fourteen studies involving 4041 participants were included.

Our primary outcome measure was alcohol consumption. A meta‐analysis of four studies showed a significant difference in favour of brief interventions in the reduction of alcohol consumption at six month follow up, MD ‐69.43 (95% CI ‐128.14 to ‐10.72). A sensitivity analysis (one study was removed due to methodological heterogeneity) also demonstrated a trend in this direction but the result become not statistically significant, MD ‐55.49 (95% CI ‐115.33 to 4.35). There was also a significant difference in favour of the brief intervention group based on the results of one study for alcohol consumption at nine months follow up. However there was no significant difference between the groups at one year follow up. Furthermore there was a significant difference in self reports of reduction of alcohol consumption at one year in favour of brief interventions, SMD ‐0.26 (95% CI ‐0.50 to ‐0.03), but there was no significant difference between the groups at 3 or 6 months.There was a statistically significant outcome in favour of the brief intervention group in relation to heavy drinking episodes in days per week at four months, MD ‐0.56; (95% CI ‐1.02 to ‐0.10), nine months MD ‐0.78 (95% CI ‐1.32 to ‐0.24) and one year follow up MD ‐0.71 (95% CI ‐1.26 to ‐0.16) though this was based on the results of one study. Again based on the results of one study the findings were statistically significant for number of heavy drinking episodes per week at four months MD ‐0.56 (95% CI ‐1.02 to ‐0.10), nine months MD ‐0.78 (95% CI ‐1.32 to ‐0.24) and one year MD ‐0.71 (95% CI ‐1.26 to ‐0.16) in favour of the brief interventions group.

There was also statistically significant differences for death rates at 6 months RR 0.42 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.94) and one year follow up RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.40 to 0.91) in favour of those who received the brief intervention. A sensitivity analysis ‐ removing the physician delivered intervention group from one study ‐ also demonstrated statistically significant difference RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.96) in favour of brief interventions.

However there were no significant differences between brief interventions and control groups at any time points for; alcohol consumption based on change scores from baseline, laboratory markers (GammaGT), number of binges, driving offences within 3 years, or for studies including only men mean alcohol consumption in grams per week. These findings are in line with other reviews of brief interventions in primary care primary care (Bertholet 2005; Kaner 2007) and hospital settings (Emmen 2004). The absence for any change in laboratory markers (GammaGT) could be due to the fact that such tests do not show moderate reduction in alcohol consumption and appear to lack sensitivity for non alcohol dependent hazardous and harmful drinkers.

Secondary outcome measures of interest considered whether brief interventions improve quality of life and ability to function in society i.e. social relationships, employment, education and reduce alcohol related injuries (e.g. falls violence, suicide and motor vehicle accidents). Apart from one study (Schermer 2006) which reported on driving offences none of the studies specifically measured these secondary outcomes.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Study Participants The studies used a variety of methods to identify heavy alcohol users such as FAST, AUDIT, CAGE, retrospective drinking diaries, number of standard drinks per week. There was no consistency across the studies in baseline consumption levels for participants to be included. Seven of the fourteen studies attempted to exclude alcohol dependent participants through excluding those known to addiction services, evidence of chronic physical alcohol problems, those deemed to be alcohol dependent by medical staff or scoring positive for dependence on Short Form Alcohol Dependence data questionnaire. In the remaining six studies one intentionally included alcohol dependent participants with the remaining studies reporting no upper limit in terms of alcohol consumption with hazardous, harmful and dependent alcohol drinkers all being included. Brief interventions have been reported to be ineffective with alcohol dependent individuals (Bertholet 2005) though there is ongoing debate within the field. It is therefore anticipated that the inclusion of alcohol dependent participants in six out of 14 studies included in this review may have impacted upon the results. Whilst the authors of this review did consider conducting a sensitivity analysis based on the information contained in the studies alcohol dependence was difficult to definitively define. However further updates of this review should consider this aspect as more studies become available.

Four studies included male participants only (Antti‐Poika 1988; Chick 1985; Heather 1996Liu 2011) with the remaining ten studies having a higher percentage of male participants typically around 80%. The Cochrane review on brief interventions in primary care reports that brief interventions reduced the quantity of alcohol consumed per week in men, but not women (Kaner 2007). However, no conclusions on gender effect can be drawn from our review.

Treatment exposure Brief interventions were delivered by a number of different professionals ranging from physicians, nurses, psychologists, psychology students, occupational therapists and social workers. There is no evidence to suggest the outcomes were different depending on who delivered the intervention with an important element of brief interventions being that they can be delivered by non‐specialist staff. There was some clinical heterogeneity between the trials in terms of the characteristics of brief interventions (number of sessions, duration). One study (Antti‐Poika 1988a) was classified as higher intensity based on the number of sessions spent counselling participants in the intervention group. This study showed a greater reduction in alcohol consumption than trials with a less intensive treatment exposure. However these results should be interpreted with caution as they are based on one small study (N=120) and it should also be noted that the assessor was not blinded which may have led to bias. These findings fit with the earlier systematic review on brief interventions in primary care (Kaner 2007) which found weak evidence that a greater length of time spent counselling patients may result in greater reduction in alcohol consumption. The structure and content of brief interventions requires further research to evaluate effectiveness for hospital inpatients.

It is acknowledged that there are two categories of brief interventions, simple advice and extended brief interventions (Raistrick 2006). Some studies included in this review would fit clearly into these categories but due to the limited number of studies with comparable outcomes a sub group analysis was not possible. Should further studies emerge during the updating of this review it would be important to consider undertaking a comparison of simple advice versus extended brief interventions. This has been identified as being a pressing issue in this field of research.

Within the studies included in this review it is acknowledged that there are differences in control groups – some studies had usual care, some gave a leaflet (which could be seen as advice) and some gave feedback on the results. Some of the studies included in this review reported a reduction in alcohol consumption even in the control group.The impact of screening should also be considered as the phenomenon of assessment (or screening) reactivity appears well‐recognised in the alcohol field (Kypri 2007; McCambridge 2008; Ogborne 1988). Screening involves asking participants about their drinking patterns and this may have influenced drinking behaviour in the short term as may the provision of a health education leaflet or feedback on the results of screening. This view has also been acknowledged by Kaner 2007 'Effectiveness of Brief Interventions in Primary Care' which suggests that screening may impact on alcohol consumption and is an area that requires further investigation. However there are alternative explanations for example, regression to the mean or merely the fact that the participants were admitted to hospital . With the potential that admission to hospital acted as a catalyst for individuals to review and change their alcohol consumption.

Length of follow‐up The period of time between the delivery of brief interventions and follow up assessment ranged from three months to three years. Four studies reported outcomes following six months and six reported outcomes at one year. The results of this review demonstrate a significant difference in favour of brief interventions in the reduction of alcohol consumption at six month and nine month follow up, but there was no significant difference between the groups at one year follow up. However there was a significant difference in self reports of reduction of alcohol consumption at 1 year in favour of brief interventions. T

Completeness and applicability of evidence The 14 studies included in this review were all written in English and originated mainly from America (N=5) and the United Kingdom (N=4). This may limit the applicability of the evidence to these healthcare systems and social environments. However evidence suggests that alcohol consumption levels have been identified as more prevalent in Western Europe and America (Leon 2006). The majority of the participants in the studies were male and four studies only included men, in the remaining ten studies the participants were mixed but predominately 80% were male. This may limit the generalizability of the results to female heavy alcohol users. It is also important to note that the largest multi‐national study into brief interventions (WHO 1996) was not included in this review; it included participants from a variety of primary care settings in addition to general hospital, it was not possible to separate the data to include only participants from general hospital.

Quality of the evidence

Fourteen studies were included in this review seven of which were randomised control trials. Of the remaining seven, one was a cluster randomised control trial and six studies were controlled clinical trials. Lack of adequate allocation concealment is associated with bias (Moher 1998; Schulz 1995) therefore the impact of this on results should be considered. In seven studies the participants were not randomised to control or brief intervention groups and it is unlikely that allocation up to the point of assignment was concealed. Whilst the methodological quality of the included studies was mixed the nature of brief interventions is subject to several potential methodological limitations. Due to the nature of this intervention i.e. individualised brief interventions it was not possible to blind the participants. Though blinding of outcome assessors was possible however outcome assessors were blinded in only nine studies.This is of major concern because most of the outcomes considered by the studies were subjective. Contamination between control and intervention participants may also have introduced the possibility of performance bias. However current evidence suggests that only adequate randomisation, allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessor will influence effect size (Higgins 2008).

There was also methodological heterogeneity in terms of the types of outcomes reported for self reported alcohol consumption and laboratory markers used which meant meta‐analysis for these outcomes was limited.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Emmen 2004 focused specifically on general hospital settings identifying eight studies and concluded that the evidence for brief interventions in a general hospital setting for problem drinkers was still inconclusive. Our review has identified 14 studies and includes data up to 2011. Emmen 2004 also included four studies which were excluded from our review as the interventions did not fit with our definition of brief interventions (two as the brief intervention took place in an outpatient clinic, one as it was an audio‐visual presentation rather than a face to face brief intervention and one as it was a confrontational interview to try and persuade alcohol abusers to accept treatment).

The Cochrane systematic review (Kaner 2007) which relates to brief interventions in primary care included a meta‐analysis of 21 trials and reports strong evidence in favour of brief interventions. Both the review in primary care and the current review suggest that screening alone may result in reduced alcohol consumption and make recommendations to investigate this further.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

The main results of this review indicate that there are benefits to delivering brief interventions to heavy alcohol users in general hospital. Our results demonstrate that patients receiving brief interventions have a greater reduction in alcohol consumption compared to those in control groups at six month and nine month follow up but this is not maintained at one year. In addition there were significantly fewer deaths in the groups receiving brief interventions than in control groups at 6 months and one year. However, these findings are based on studies involving mainly male participants. Furthermore screening, asking participants about their drinking patterns, may also have a positive impact on alcohol consumption levels and changes in drinking behaviour.

Implications for research.

The effect of brief interventions for heavy alcohol users in general hospitals requires further investigation to determine the optimal content of brief intervention and treatment exposure and whether they are likely to be more successful in patients with certain characteristics. To facilitate meta‐analysis, future research should utilise primary outcome measures such as alcohol consumption reporting in either units or grams of alcohol consumed or changes in alcohol consumption from baseline. Surveillance post intervention should be at least one year. Future studies in this area should consider the CONSORT statement as a guide for both designing and reporting (www.consort‐statement.org). Reporting should include the method of randomisation, the use of blinded assessors, and an intention to treat analysis and data presented as means and standard deviations for continuous measures or number of events and total numbers analysed for dichotomous measures. Future trials are required to add to the evidence base for brief interventions in general hospital. In addition research should consider the impact of screening and where possible investigate the effect on both males and females. Recent debates within the brief interventions field have also focused on wether brief interventions delivered within general hospital are more effective in certain populations such as young people or women or those with an alcohol attributed admission Saitz 2009; Williams 2010.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 17 September 2015 | Amended | Contact details updated. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 2, 2005 Review first published: Issue 3, 2009

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 July 2011 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | new citation because of new search, new studies, background emended |

| 12 May 2011 | New search has been performed | Three additional studies included. Background information, results, discussion and conclusions updated. Changes to findings. |

| 6 November 2008 | New search has been performed | Data added into studies awaiting assessment, track changes accepted, references checked info on results for driving offences added |

| 16 June 2008 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment |

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Claire Ritchie Occupational Therapy Manager for her support during this process, Lynn Legg for comments and advice on drafting the protocol. Roberto Mollica for reviewing and commenting on the draft protocol and Simona Vecchi for assistance with the search strategy together with support and advice on the review process. Fiona Cooper for assisting in identifying studies for inclusion. We wish to thank NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde occupational therapy department and Partnerships in Care (Ayr Clinic) for their continued support and Charlotte Boulnois hospital librarian for help with locating articles.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Cochrane Library search strategy

MeSH descriptor Alcohol Drinking explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Alcohol‐Related Disorders explode all trees

((alcohol*) near/2 (abuse or use* or disorder* or consumption or drink*))

alcohol*

(#1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4)

MeSH descriptor Nursing Care explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Patient Care explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Hospital Units explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Hospitals explode all trees

MeSH descriptor Inpatients explode all trees

inpatient*

hospital*

MeSH descriptor Patient Admission explode all trees

(#6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13)

(#5 AND #14)

brief near/2 intervention

MeSH descriptor Psychotherapy, Brief explode all trees

counselling

counseling

(#16 OR #17 OR #18)

(#15 AND #20)

(#21), from 2008 to 2011

Appendix 2. PubMed search strategy

Subject specific

Alcohol‐Related Disorders[Mesh]

((alcohol) and (abuse or misuse* or disorder* or drink* or consumption *))

((hazard* or risk or heav*) AND (drink*))

#1 or #2 or #3

"Patient Care"[MeSH]

"Patient Admission"[Mesh]

Inpatients[MeSH]

Hospitals[MeSH]

Hospital* or inpatient*

#5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9

"brief intervention*"

"alcohol reduction"

“alcohol intervention”

“early intervention”

“minimal intervention”

counselling or counseling

#11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16

randomized controlled trial[pt]

controlled clinical trial[pt]

Random*[tiab]

placebo[tiab]

drug therapy [sh]

trial [tiab]

groups [tiab]

#18 or #19 or #20 or #21 or #22 or #23 or #24

animals [mh] NOT humans [mh]

#25 NOT #26

#4 AND #10 AND #17 AND #27

Appendix 3. CINAHL search strategy via EBSCO

(MH "Alcohol‐Related Disorders+")

TX ((alcohol) and (abuse or misuse* or disorder* or drink* or consumption *))

TX ((hazard* or risk or heav*) AND (drink*))

S1 or S2 or S3

(MH "Acute Care")

(MH "Inpatients")

TX inpatient*

(MH "Hospitals+")

(MH "Hospital Units+")

TX hospital

TX Hospital*

(MH "Patient Admission")

S5 or S6 or S7 or S8 or S9 or S10 or S11 or S12

TX "brief intervention"

TX counselling or TX counseling

TX “alcohol reduction”

TX “alcohol intervention”

TX “early intervention”

TX “minimal intervention”

S14 or S15 or S16 or S17 or S18 or S19

S4 and S13 and S20

MW randomi* or TI randomi* or AB randomi* or IN randomi*

MW Clin* or TI Clin* or AB Clin* or IN Clin*

MW trial* or TI trial* or AB trial* or IN trial

S23 and S24

(MH "Single‐Blind Studies")

(MH "Double‐Blind Studies")

(MH "Triple‐Blind Studies")

S26 or S27 or S28

MW singl* or TI singl* or AB singl* or IN singl*

MW doubl* or TI doubl* or AB doubl* or IN doubl*

MW tripl* or TI tripl* or AB tripl* or IN tripl*

MW trebl* or TI trebl* or AB trebl* or IN trebl*

MW mask* or TI mask* or AB mask* or IN mask*

MW blind* or TI blind* or AB blind* or IN blind*

S34 or S35

S30 or S31 or S32 or S33

(MH "Crossover Design")

MW crossover or AB crossover or TI crossover or IN crossover

MW allocate* or AB allocate* or TI allocate* or IN allocate*

MW assign* or AB assign* or TI assign* or IN assign*

S40 or S41

MW random* or TI random* or IN random* or AB random*

S42 and S43

(MH "Random Assignment")

(MH "Clinical Trials+")

S22 or S25 or S26 or S27 or S28 or S29 or S30 or S31 or S32 or S33 or S36 or S37 or S38 or S39 or S44 or S45 or S46

S21 and S47

Appendix 4. EMBASE search strategy

1. alcohol abuse:MESH 2. ((alcohol) and (abuse or use* or disorder*)) 3. alcohol* 4. 1 or 2 or 3 5. exp Emergency Care/ 6. (acute and care) 7. exp hospital patient/ 8. inpatient* 9. exp Hospital/ or Hospital* 10. (patient and Admission) 11. exp Nursing Care/ 12. 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 13. "brief intervention" 14. random* 15. placebo* 16. ((singl* or doubl* or trebl* or tripl*) and (blind* or mask*)) 17. (crossover*) 18. exp randomized controlled trial 19. exp phase‐2‐clinical‐trial 20. exp phase‐3‐clinical‐trial 21. exp double blind procedure 22. exp single blind procedure 23. exp crossover procedure 24. exp Latin square design 25. exp PLACEBOS 26. exp multicenter study 27. 14/26 OR 28. 4 and 12 and 13 and 27 29. limit 28 to human

Appendix 5. Criteria for risk of bias assessment

| Item | Judgment | Description |

| random sequence generation (selection bias) | low risk | The investigators describe a random component in the sequence generation process such as: random number table; computer random number generator; coin tossing; shuffling cards or envelopes; throwing dice; drawing of lots; minimization |

| high risk | The investigators describe a non‐random component in the sequence generation process such as: odd or even date of birth; date (or day) of admission; hospital or clinic record number; alternation; judgement of the clinician; results of a laboratory test or a series of tests; availability of the intervention | |

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information about the sequence generation process to permit judgement of low or high risk | |

| allocation concealment (selection bias) | low risk | Investigators enrolling participants could not foresee assignment because one of the following, or an equivalent method, was used to conceal allocation: central allocation (including telephone, web‐based, and pharmacy‐controlled, randomisation); sequentially numbered drug containers of identical appearance; sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes. |

| high risk | Investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignments because one of the following method was used: open random allocation schedule (e.g. a list of random numbers); assignment envelopes without appropriate safeguards (e.g. if envelopes were unsealed or nonopaque or not sequentially numbered); alternation or rotation; date of birth; case record number; any other explicitly unconcealed procedure. | |

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk This is usually the case if the method of concealment is not described or not described in sufficient detail to allow a definite judgement | |

| blinding of outcome assessor (detection bias) |

low risk |

No blinding of outcome assessment, but the review authors judge that the outcome measurement is not likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; Blinding of outcome assessment ensured, and unlikely that the blinding could have been broken |

| high risk | No blinding of outcome assessment, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding; Blinding of outcome assessment, but likely that the blinding could have been broken, and the outcome measurement is likely to be influenced by lack of blinding |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk; | |

| incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) For all outcomes except retention in treatment or drop out |

low risk |

No missing outcome data; Reasons for missing outcome data unlikely to be related to true outcome (for survival data, censoring unlikely to be introducing bias); Missing outcome data balanced in numbers across intervention groups, with similar reasons for missing data across groups; For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on the intervention effect estimate; For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes not enough to have a clinically relevant impact on observed effect size; Missing data have been imputed using appropriate methods All randomised patients are reported/analysed in the group they were allocated to by randomisation irrespective of non‐compliance and co‐interventions (intention to treat) |

| high risk | Reason for missing outcome data likely to be related to true outcome, with either imbalance in numbers or reasons for missing data across intervention groups; For dichotomous outcome data, the proportion of missing outcomes compared with observed event risk enough to induce clinically relevant bias in intervention effect estimate; For continuous outcome data, plausible effect size (difference in means or standardized difference in means) among missing outcomes enough to induce clinically relevant bias in observed effect size; ‘As‐treated’ analysis done with substantial departure of the intervention received from that assigned at randomisation; |

|

| Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit judgement of low or high risk (e.g. number randomised not stated, no reasons for missing data provided; number of drop out not reported for each group); | |

| Other bias | low risk | The study appears to be free of other sources of bias. |

| high risk | There is at least one important risk of bias. For example, the study:

|

|

| Unclear risk | There may be a risk of bias, but there is either:

|

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Brief interventions versus control.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week: smaller values indicate better outcome | 8 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 1.1 4 month follow up | 1 | 511 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐16.32 [‐180.89, 148.25] |

| 1.2 6 month follow up | 4 | 453 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐69.43 [‐128.14, ‐10.72] |

| 1.3 9 month follow up | 1 | 479 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐182.88 [‐360.00, ‐5.76] |

| 1.4 1 year follow up | 4 | 1073 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐33.62 [‐82.27, 15.03] |

| 2 Sensitivity analysis: Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week: smaller values indicate better outcome | 7 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 2.1 6 month follow up | 3 | 364 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐55.49 [‐115.33, 4.35] |

| 2.2 1 year follow up | 4 | 997 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐36.31 [‐86.64, 14.01] |

| 3 Mean alcohol consumption (change scores from baseline): smaller values indicate better outcome | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 3.1 6 month follow up | 2 | 687 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.26 [‐0.73, 0.21] |

| 3.2 1 year follow up | 2 | 696 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐0.08 [‐0.41, 0.24] |

| 4 Self reports of alcohol consumption (smaller values indicate better outcome) | 3 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 4.1 3 month follow up | 1 | 27 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.14 [‐0.90, 0.61] |

| 4.2 6 month follow up | 2 | 405 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.04 [‐0.24, 0.15] |

| 4.3 1 year follow up | 1 | 275 | Std. Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.26 [‐0.50, ‐0.03] |

| 5 Laboratory markers (GammaGT): smaller values indicate better outcome | 3 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 5.1 6 month follow up | 1 | 89 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 7.0 [‐33.77, 47.77] |

| 5.2 1 year follow up | 2 | 160 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐5.05 [‐36.82, 26.73] |

| 6 Number of binges: smaller values indicate better outcome | 1 | 287 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.99 [0.83, 1.19] |

| 7 Heavy drinking episodes (days per week): smaller values indicate better outcome | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 7.1 4 months follow up | 1 | 511 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.56 [‐1.02, ‐0.10] |

| 7.2 9 months follow up | 1 | 479 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.78 [‐1.32, ‐0.24] |

| 7.3 12 months follow up | 1 | 473 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | ‐0.71 [‐1.26, ‐0.16] |

| 8 Death: smaller values indicate better outcome | 9 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 8.1 3 month follow up | 1 | 27 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 1.08 [0.07, 15.50] |

| 8.2 4 month follow up | 1 | 520 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.36 [0.07, 1.86] |

| 8.3 6 month follow up | 4 | 1166 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.42 [0.19, 0.94] |

| 8.4 9 month follow up | 1 | 495 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.89 [0.34, 2.33] |

| 8.5 1 year follow up | 7 | 2396 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.60 [0.40, 0.91] |

| 9 Sensitivity analysis: Death: smaller values indicate better outcome | 7 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 9.1 1 year follow up | 7 | 2275 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Random, 95% CI) | 0.61 [0.39, 0.96] |

| 10 Mean alcohol consumption in grams per week restricted to studies including only men: smaller values indicate better outcome | 4 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 10.1 4 month follow up | 1 | 511 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐16.32 [‐180.89, 148.25] |

| 10.2 6 month follow up | 2 | 169 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐201.73 [‐586.96, 183.50] |

| 10.3 9 month follow up | 1 | 479 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐182.88 [‐360.00, ‐5.76] |

| 10.4 1 year follow up | 2 | 606 | Mean Difference (IV, Random, 95% CI) | ‐51.52 [‐144.25, 41.20] |

| 11 Driving offences within 3 years: smaller values indicate better outcome | 1 | 126 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.52 [0.22, 1.19] |

| 12 Number of days hospitalised in previous 3 months: smaller values indicate better outcome | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 12.1 4 months follow up | 1 | 511 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.41 [‐0.46, 1.28] |

| 12.2 9 months follow up | 1 | 479 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.73 [‐0.23, 1.69] |

| 12.3 12 months follow up | 1 | 473 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.56 [‐0.39, 1.51] |

| 13 A&E visits in previous 3 months: smaller values indicate better outcome | 1 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only | |

| 13.1 4 months follow up | 1 | 511 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.03 [‐0.03, 0.09] |

| 13.2 9 months follow up | 1 | 479 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.06 [‐0.00, 0.12] |

| 13.3 12 months follow up | 1 | 473 | Mean Difference (IV, Fixed, 95% CI) | 0.05 [‐0.01, 0.11] |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Antti‐Poika 1988.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | Country of origin: Finland; N=120; Age: 20‐64years; Sex: Male Clinical Setting: Orthopaedic and trauma centre Inclusion criteria: injured patients admitted for >24hours heavy drinkers scoring 7 points or more on SMAST Exclusion: patients with severe injuries e.g. major head injury, interview not possible | |

| Interventions | Intervention delivered by: nurse and physicians Brief intervention group: 2 counselling sessions with a nurse and 1‐3 sessions with a physician plus booklet on how to control drinking (N=60) Control group: Screening but no intervention (N=60) |

|

| Outcomes | Length of follow‐up 6 months 1) Alcohol consumed in the past week 2) Blood tests S‐ASAT, S‐ALAT, S‐GGT obtained at 6 months | |

| Notes | This may be more than a brief intervention as 2 counselling sessions with a nurse and 1‐3 sessions with a physician plus booklet on how to control drinking. | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Mentions randomisation but does not state method used |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information about the allocation concealment process to permit judgement of 'low' or 'high risk' |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Unclear risk | Loss to follow up: 11/60 intervention and 20/60 control group. Not clear if these are taken into account in analysis |

| Other bias | High risk | Groups not similar at baseline mean alcohol consumption in gramme 308 intervention group and 736 control group. Additionally this may be more than a brief intervention as 2 counselling sessions with a nurse and 1‐3 sessions with a physician plus booklet on how to control drinking. |

| Blinding of assessors? | Unclear risk | Does not state assessors were blind |

Chick 1985.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | Coumtry of origin: UK; N=156; Age 16‐65 years; Sex: Male Clinical Setting: General hospital medical wards Inclusion Criteria: patients admitted for >48 hours, who scored positive for 2 or more items on set criteria list Exclusion: no fixed abode, mental state precluding reliable history, terminally ill or already referred to department of Pscychiatry. |

|

| Interventions | Brief intervention delivered by: Nurse Brief Intervention group: one 30‐60 min counselling session with nurse (N=78) Control group: Assessment only (N=78) |

|

| Outcomes | Follow up at 6 and 12 months 1) Mean GGT 2) Absence of alcohol related symptoms 3) Reported consumption fallen by 50% 4) Relatives feedback 5) death at 12 months |

|

| Notes | ||

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Alternate wards rotated between control and intervention |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | High risk | Investigators enrolling participants could possibly foresee assignment as allocation to control or intervention was rotated between wards |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | High risk | Losses to follow up: 14/78 control group and 9/78 intervention group. Not clear if these are taken into account in analysis |

| Other bias | Low risk | no additional sources of bias identified the authors have acknowledged that the groups were not matched for the number of alcohol related problems at intake though this outcome was not specifically reported upon in this review |

| Blinding of assessors? | Low risk | Stated as blind to group |

Freyer‐Adam 2008.

| Methods | CCT | |

| Participants | Country of origin: Germany; N=595; Age: 18‐64years; Sex: Mixed Clinical Setting: General Hospital Inclusion criteria: Scored positive on AUDIT and LAST, admitted to hospital > 24hrs. Exclusion: Patients not cognitively/physically capable and those meeting criteria for alcohol dependence. | |

| Interventions | Brief Intervention delivered by: addiction counsellor, psychologist, social workers and physicians Brief intervention group1: (N=249) 25 minutes counselling adapted to individual circumstances and delivered by addiction counsellor, psychologist, social workers Brief intervention group 2: (N=121) 25 minutes counselling adapted to individual circumstances and delivered by physicians Control: Usual care |

|

| Outcomes | Length of follow‐up 12 months

1) Grams of alcohol per week 2) Death at 12 months |

|

| Notes | Data was presented separately for liaison and physicians groups and as pooled data | |

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | High risk | Randomisation by time frame based on date of admission. Control group recruited first. |