Abstract

The present study aimed to histologically clarify the regional specificity of the mucosal enteric glial cells (mEGCs) in the rat intestine with serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF-SEM). SBF-SEM analysis with the ileum, the cecum and the descending colon revealed that mEGC nuclei were more abundant in the data stacks from the apical portion of the villus and the lateral portion of the crypt of the ileum. mEGCs exhibited a high rate of coverage over the nerve bundle around the lateral portion of the ileal crypt, but showed an extremely low level of coverage in the luminal portion of the cecum. These findings evidenced regional differences in the localization of mEGCs and in their sheath structure in the rat intestine.

Keywords: enteric glial cell, enteric nervous system, rat, serial block-face scanning electron microscopy

Enteric glial cells (EGCs) are an important component of the enteric nervous system (ENS), the specific nervous system in the animal intestine. EGCs are thought to play a role in maintaining the epithelial barrier, and they participate in the neurotransmission and regulation of intestinal motility (reviewed in [10]). Indeed, EGCs express nerve growth factor [25] and seem able to detect glutamate [20], acetylcholine, and serotonin [3]. The glial fibrillary acidic protein dependent ablation of EGCs results in the inflammation of the small intestine [6], thus revealing the necessity of EGCs for intestinal homeostasis. In several studies, EGCs exhibited heterogenetic populations that could be divided into several subtypes [4, 11]. Among them, EGCs in the myenteric plexus have been well studied and found to possess oval or elongated nuclei, with conspicuous heterochromatin and cellular processes ensheathing the outer aspect of the nerve bundle, as revealed by transmission electron microscopy [7, 9, 14]. Thus, histological investigations of EGCs focused mostly on the myenteric plexus, while the histological characteristics of mucosal EGCs (mEGCs) have been largely unknown.

A recently developed imaging technology called three-dimensional analysis with electron microscopy enables us to easily understand the ultrastructures of animal tissues well. Indeed, using a method for this technology called serial block-face scanning electron microscopy (SBF-SEM), has thus far enabled us to clarify that the micromilieu in the intestinal mucosa differs among regions throughout the intestine [2, 16,17,18,19, 24]. For example, we have clarified that the histological characteristics of fibroblast-like cells, one of the main cell types in the lamina propria, differ among the ileum [17], the cecum, and the descending colon [24]. Moreover, the characteristics of contact between the nerve fibers and various kinds of cells in the intestinal mucosa also are different among the ileum [18], the cecum, and the descending colon [19]. However, the regional differences in mEGCs throughout the intestine have not been clarified. Interestingly, mEGCs also may be affected by microflora, because mEGCs, especially in the intestinal villus, are scarcer in germ-free mice than in conventional mice [12]. Considering that the abundance and composition of indigenous bacteria vary among the segments of the intestine [21, 26, 27], such regional differences in bacteria-derived stimulation may lead to the regional specificity of mEGCs throughout the intestine. Therefore, the present study aimed to clarify the regional specificity of mEGCs in the rat intestine by using SBF-SEM.

A total of 9 male Wistar rats aged 7 weeks (Japan SLC Inc., Hamamatsu, Japan) were maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions in individual ventilated cages (Sealsafe Plus; Tecniplast S.p.A., Buguggiate, Italy) with controlled temperature (23 ± 2°C) and humidity (50 ± 10%) on a 12/12 hr light/dark cycle at the Kobe University Life-Science Laboratory. They were permitted free access to water and food (Lab RA-2; Nosan Corp., Yokohama, Japan). This experiment was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (permission numbers: 25-06-01 and 30-05-01). All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution (the Kobe University Animal Experimentation Regulations). We focused on the three different regions, the ileum, the cecum, and the descending colon, in this study because the other types of cells in the mucosa, such as fibroblast-like cells [17, 24] and the nerve network [18, 19], exhibited the regional differences among these three regions. The data stacks obtained from SBF-SEM in our previous studies [17,18,19, 24] were reused in the present study (Supplementary Fig. 1). Therefore, the experimental procedures for acquiring the data stacks with SBF-SEM were similar to those previously described. The observation conditions in each tissue block were as follows: acceleration voltage, 1.2–1.5 kV; probe current, 100–164 pA; size in pixels, 8,192 × 8,192; X-Y resolution, 6.0–7.2 nm × 6.0–7.2 nm; slice pitch, 100 nm; slice number, 392 or more (Table 1). Each data stack was aligned using Fiji [22] or DigitalMicrograph software (Gatan, Abingdon, UK). Alignment analyses for some of the data stacks were conducted after binning. All nerve bundles, each mEGC, and each mECG nucleus observed in these aligned data stacks were three-dimensionally reconstructed using the IMOD program [15].

Table 1. Number of nuclei of mucosal enteric glial cells (mEGCs) in each data stack.

| Region | Portion | Data stack | Slice number | Number of mEGC nuclei | Rat # |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ileum | IVA | 1 | 623 | 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 533 | 2 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 580 | 1 | 3 | ||

| IVB | 1 | 600 | 0 | 4 | |

| 2 | 520 | 0 | 2 | ||

| 3 | 800 | 0 | 3 | ||

| ICL | 1 | 558 | 3 | 5 | |

| 2 | 672 | 3 | 6 | ||

| 3 | 653 | 1 | 3 | ||

| ICB | 1 | 600 | 1 | 1 | |

| 2 | 451 | 0 | 5 | ||

| 3 | 659 | 0 | 6 | ||

| Cecum | Lu | 1 | 392 | 0 | 7 |

| 2 | 521 | 0 | 8 | ||

| 3 | 810 | 0 | 9 | ||

| ICB | 1 | 746 | 0 | 7 | |

| 2 | 773 | 1 | 8 | ||

| 3 | 504 | 0 | 9 | ||

| 3′ | 669 | 0 | 9 | ||

| DC | Lu | 1 | 501 | 0 | 7 |

| 2 | 601 | 0 | 8 | ||

| 3 | 672 | 1 | 9 | ||

| ICB | 1 | 814 | 1 | 7 | |

| 2 | 776 | 0 | 8 | ||

| 3 | 651 | 0 | 9 | ||

IVA, apical portion of intestinal villus; IVB, basal portion of intestinal villus; ICL, lateral portion of intestinal crypt; Lu, luminal side; DC, descending colon.

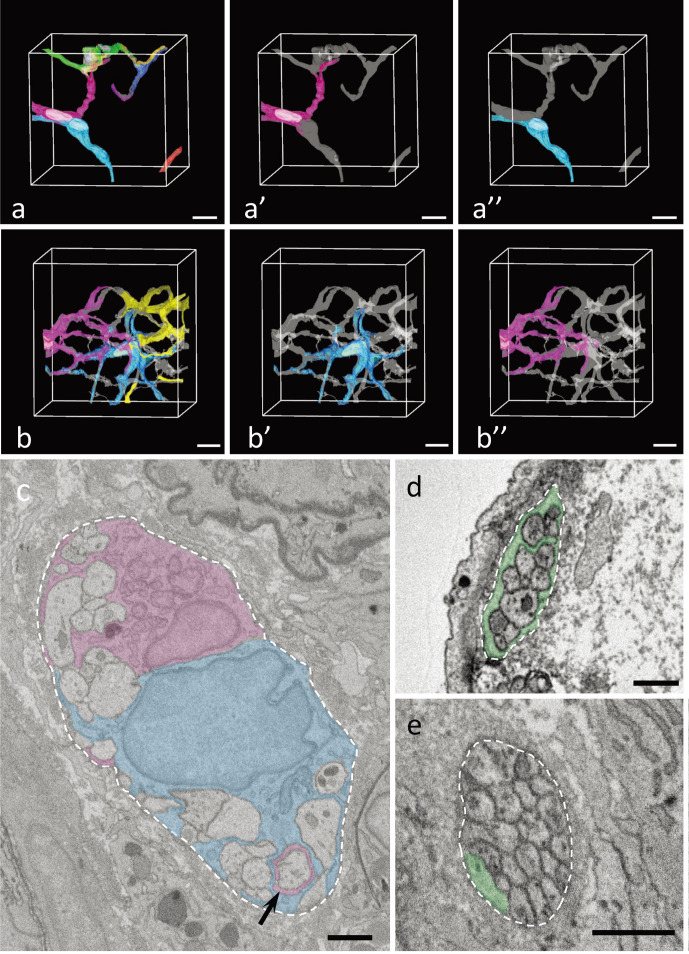

SBF-SEM analysis revealed that mEGCs were found as a structural component of nerve bundles and extended the cellular process along the nerve network (Fig. 1). The nuclei of mEGCs in the lamina propria were abundant in the data stacks from the apical portion of the intestinal villus and the lateral portion of the intestinal crypt of the ileum, while scarce in the data stack around the crypt base in all regions and on the luminal side of the descending colon (Table 1). Nuclei of mEGCs were not detected in the data stacks from the basal portion of the intestinal villus of the ileum or on the luminal side of the cecum (Table 1). One primary cilium was found to extend from near the centrioles of all mEGCs analyzed in the present study (Supplementary Fig. 2), similar to fibroblast-like cells in the previous study [24], although that was only slightly exserted from the cellular surface. The extension of the cellular process from mEGCs into the epithelium and the contact with enteroendocrine cells, both of which is reported in the mouse small intestine [5], was never found in the present study despite careful observation.

Fig. 1.

a: Three-dimensional images of the nerve bundle (gray) and each mucosal enteric glial cell (mEGC) (magenta, yellow, green, blue etc.) in the lateral portion of the intestinal crypt in the ileum. Bar=10 μm. A part of individual mEGCs are shown in panels 1a’–a”. b: Three-dimensional images of the nerve bundle (gray) and mEGCs (blue, magenta and yellow) in the apical portions of an intestinal villus in the ileum. The cellular bodies from two mEGCs whose nuclei are at least partially included in the data stack are shown as blue and magenta, whereas the cellular processes from the mEGCs whose nuclei are not included in the data stack are collectively shown as yellow. Bar=10 μm. Individual mEGC are shown in panels 1b’–b”. c: Ultrastructural image of two mEGCs sheathing a nerve bundle. The magenta mEGC is the same cell as that shown in panel 1a’, and the blue mEGC is the same cell as that shown in panel 1a”. A cellular process from one mEGC (magenta) extends into the sheath structure of another mEGC (blue) (arrow). Bar=1 μm. d, e: Ultrastructural image of a nerve bundle with mEGCs (green). mEGCs sheathe the entire region of a nerve bundle around the lateral portion of the intestinal crypt (d), but hardy sheathe it in the apical portion of the intestinal villus (e). Bar=1 μm. a–e: Three rats were used to analyze each region, as shown in Table 1.

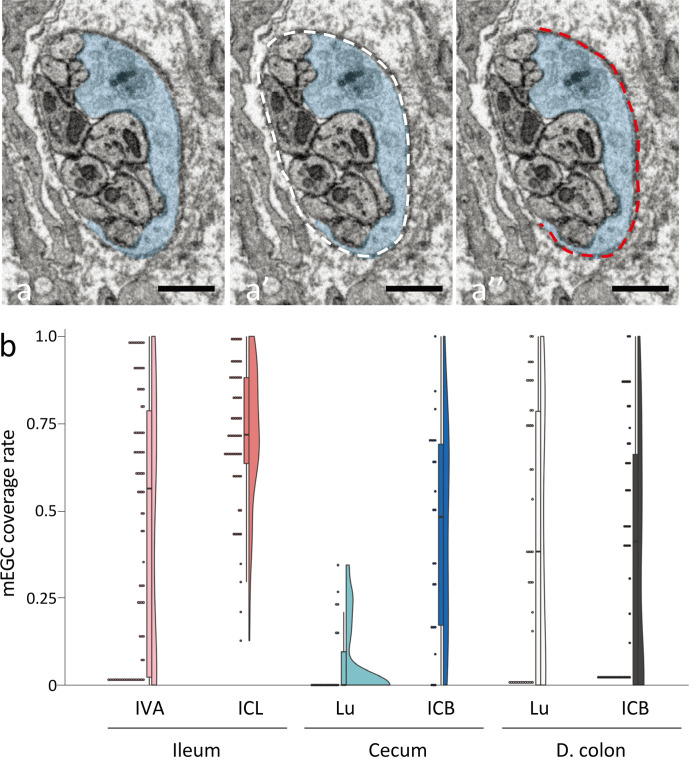

mEGCs sheathed entire of nerve bundles rather than individual fibers (Fig. 1c, 1d). Overlapping regions were found between those sheath structures from two mEGCs neighboring each other, and it was also found, though rarely, that a cellular process from one mEGC extended into the sheath structure of a neighboring mEGC (Fig. 1c). The formation of a sheath by mEGCs was incomplete especially in the peripheral region of their cellular processes in all data stacks. In the ileum, the nerve bundle in the apical portion of the intestinal villus contained a region with scarce or no mEGCs sheath (Fig. 1e), whereas these regions seemed to be fewer around the lateral portion of the intestinal crypt (Fig. 1d). Observation of each data stack in which multiple mEGCs were contained revealed that the territory of the sheath structure from an mEGC were usually overlapped with that from a neighboring mEGC around the lateral portion of the ileal crypt (Supplementary Fig. 3). However, in the nerve bundle of the apical portion of the intestinal villus, such overlaps in sheath structures were occasionally absent, leading to the observation of nerve bundles without the sheath structure of mEGCs in that area (Supplementary Fig. 3). Then, we next tried to quantitatively investigate the regional difference in mEGC coverage rate of nerve bundles in each region. After selecting two or more images from parts containing one or more nerve bundle in each data stack at 10 μm intervals, the mEGC coverage rate of the nerve bundle was measured in all cross sections of each nerve bundle contained in each chosen image with Fiji [22] (Fig. 2a). One of the data stacks in the luminal side of the descending colon and one of those in the crypt base of the descending colon were excluded from this measurement because they weren’t sufficiently in focus to trace the outlines of mEGCs. The results was showed by the combination graph of scatter chart, box plot and violin plot, which was made with the modified code of geom_flat_violin.R (https://gist.github.com/dgrtwo/eb7750e74997891d7c20). As the result of this histological measurement, the nerve bundle with scarce or no mEGCs sheath were more abundant in the apical portion of intestinal villus in the ileum than the lateral portion of the intestinal crypt in the ileum (Fig. 2b). Furthermore, the mEGC coverage level in the luminal side of the cecum was extremely low compared to the other regions, so a large part of each nerve bundle was not sheathed by mEGCs there (Fig. 2b). The mEGC coverage level in the descending colon showed no distinguishing features, and was somewhat similar to that in the apical portion of intestinal villus in the ileum (Fig. 2b). Individual differences among rats in this histological measurement were small in any region (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Fig. 2.

a: Method to calculate the coverage rate of a nerve bundle by mucosal enteric glial cells (mEGCs; blue). After tracing the cellular bodies and the cellular processes of all mEGCs (blue) in the data stacks, both the length of the entire circumference in each cross section of a nerve bundle (a’, white dashed line) and the length of coverage by mEGCs (a”, red dashed line) are measured with Fiji. The coverage rate by mEGCs in the nerve bundle is calculated by dividing the length of coverage by mEGCs (a”, red dashed line) by the length of the entire circumference (a’, white dashed line). Bar=1 μm. b: Distribution of the mEGC coverage rate in each cross section of a nerve bundle in the apical portion of the intestinal villus (IVA), around the lateral portion of the intestinal crypt (ICL) of the ileum, in the luminal side of the mucosa (Lu), around the crypt base (ICB) in the cecum or the descending colon (D. colon). a, b: Data stacks from three rats were used to calculate the coverage rate in the ileum and the cecum, whereas data stacks from two rats were used to calculate the coverage rate in the descending colon, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 4.

mEGCs migrate to the intestinal mucosa after birth, and stimulation from microflora stimulates this, at least in the mouse small intestine [12]. In the present study, mEGCs were more abundantly localized around the crypt orifices in the ileum, whereas they were quite scarce in the luminal side of the cecal mucosa. This finding suggested that there are mechanisms to delicately regulate the localization and abundance of mEGCs in each region of the rat intestine. The molecular mechanism underlying glial migration remains largely unclear. Researches using oligodendrocyte precursor cells have suggested that netrin and semaphorin 3A (SEMA3A) act as repulsion signals, whereas platelet-derived growth factor α and SEMA3F act as attraction signals, at least for oligodendrocyte precursor cells [8, 23]. In mice, a strong expression of SEMA3A is reported to be observed in the cecum at 11.5 days of embryonic age [1]. This high expression of SEMA3A might be involved in the lack of mEGCs in the cecal mucosa, although the regional differences in SEMA3A expression have been not clarified in adult or neonatal rats. Further study will be needed to investigate the mechanism(s) underlying regional differences in mEGC development.

Ultrastructural studies of glial cells in the myenteric plexus of the ileum and colon of guinea pig have been reported [7, 9], while the detailed ultrastructure, including the sheath structure, of mEGCs has not been clarified yet. To the best our knowledge, the present study is the first to quantitatively investigate the sheath structure of mEGCs in any animal species. SBF-SEM analysis in the present study revealed that the coverage rate is lower in the apical portion of ileal villus than around the lateral portion of ileal crypt. Indeed, most parts of the nerve bundles around the lateral portion of the ileal crypt were accompanied by the sheath structure of mEGCs because the territories of the sheath structures from neighboring mEGCs were usually overlapped with each other, whereas the nerve bundles without the sheath structure were found in the apical portion of the ileal villus. These findings lead us to hypothesize that neighboring mEGCs might interact with each other to regulate the level of sheath structure in nerve bundles in each portion of the intestine. Moreover, the sheath structures formed by mEGCs were extremely incomplete in the luminal side of the cecum. Neurotransmission in the peripheral autonomic nervous system is believed to occur through a diffusion process from swollen structures along the nerve fibers called varicosities, rather than through synapses [13]. Therefore, a sheath structure left incomplete by mEGCs might lead to effective neurotransmission through diffusion. Moreover, in our previous studies, we clarified that the nerve fibers are in contact with more abundant cells in the apical portions of intestinal villi than around the crypt using same data stacks of SBF-SEM [18], and that the nerve fibers are widely in contact with fibroblast-like cells and macrophages in the luminal side of the cecum [19]. Thus, the coverage level by mEGCs seems to inversely correlate with the abundance of contact between nerve fibers and various types of cells (e.g. fibroblast-like cells and macrophage) in the lamina propria. Given that the nerve fibers in the luminal side of the rat cecum were frequently in contact with immune cells, especially macrophages [19], the lack of sheath structure by mEGCs there might contribute to the active regulation of immune cells by the nervous system. These findings suggest that the analysis of sheath structures formed by mEGCs in nerve bundles would be important in order to interpret the neurotransmission manner in the intestinal mucosa.

The present study provided important data and hypotheses as discussed above, though some points remain unsolved. The number of mEGCs detected in the data stacks of the large intestine was quite low, so we could not sufficiently clarify the regional differences in the cellular morphology of mEGCs. The range that can be analyzed with SBF-SEM is usually narrower than those of light microscopy, including fluorescence microscopy and scanning laser microscopy. Therefore, light microscopy with EGC-specific labeling technology [4] might be better for elucidating regional differences in the cellular morphology of mEGCs. Another unresolved point is that we could not elucidate the spatial relationship between the sheath structure by mEGCs and the position of varicosity or the quantity of vesicles in each nerve fiber because of the following difficulties. First, these data stacks obtained by SBF-SEM included too many nerve fibers to be analyzed. Second, we took the wide images to broadly analyze the regional difference in mEGCs, but the image resolution resulting from this strategy was insufficient to count vesicles in the nerve fibers throughout the data stacks, as there is a trade-off between the data size in each image and its resolution. Further study using images with higher magnification will be needed to clarify the relationships between the sheath structures of mEGCs and varicosities or vesicles in nerve fibers.

In conclusion, the present study revealed regional differences in the localization of mEGCs and in the sheath structures they form in the rat intestine. The results suggested that the micromilieu in the cecal mucosa is clearly unique in that mEGCs are scarce. The present results emphasize the importance of understanding the histological features of mEGCs in order to elucidate the mechanisms of action in the mucosal nerve network.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest associated with this manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grants (nos. JP16K18813, JP16H06280 (Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas–Platforms for Advanced Technologies and Research Resources “Advanced Bioimaging Support”), and JP20K15902) and by the Cooperative Study Program (20-229) of the National Institute for Physiological Sciences.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson RB, Bergner AJ, Taniguchi M, Fujisawa H, Forrai A, Robb L, Young HM. 2007. Effects of different regions of the developing gut on the migration of enteric neural crest-derived cells: a role for Sema3A, but not Sema3F. Dev Biol 305: 287–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arai M, Mantani Y, Nakanishi S, Haruta T, Nishida M, Yuasa H, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N, Kitagawa H. 2020. Morphological and phenotypical diversity of eosinophils in the rat ileum. Cell Tissue Res 381: 439–450. doi: 10.1007/s00441-020-03209-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boesmans W, Cirillo C, Van den Abbeel V, Van den Haute C, Depoortere I, Tack J, Vanden Berghe P. 2013. Neurotransmitters involved in fast excitatory neurotransmission directly activate enteric glial cells. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25: e151–e160. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boesmans W, Lasrado R, Vanden Berghe P, Pachnis V. 2015. Heterogeneity and phenotypic plasticity of glial cells in the mammalian enteric nervous system. Glia 63: 229–241. doi: 10.1002/glia.22746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohórquez DV, Samsa LA, Roholt A, Medicetty S, Chandra R, Liddle RA. 2014. An enteroendocrine cell-enteric glia connection revealed by 3D electron microscopy. PLoS One 9: e89881. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bush TG, Savidge TC, Freeman TC, Cox HJ, Campbell EA, Mucke L, Johnson MH, Sofroniew MV. 1998. Fulminant jejuno-ileitis following ablation of enteric glia in adult transgenic mice. Cell 93: 189–201. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81571-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook RD, Burnstock G. 1976. The ultrastructure of Auerbach’s plexus in the guinea-pig. II. Non-neuronal elements. J Neurocytol 5: 195–206. doi: 10.1007/BF01181656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fruttiger M, Karlsson L, Hall AC, Abramsson A, Calver AR, Boström H, Willetts K, Bertold CH, Heath JK, Betsholtz C, Richardson WD. 1999. Defective oligodendrocyte development and severe hypomyelination in PDGF-A knockout mice. Development 126: 457–467. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.3.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gabella G. 1972. Fine structure of the myenteric plexus in the guinea-pig ileum. J Anat 111: 69–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grubišić V, Gulbransen BD. 2017. Enteric glia: the most alimentary of all glia. J Physiol 595: 557–570. doi: 10.1113/JP271021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hanani M, Reichenbach A. 1994. Morphology of horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-injected glial cells in the myenteric plexus of the guinea-pig. Cell Tissue Res 278: 153–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00305787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kabouridis PS, Lasrado R, McCallum S, Chng SH, Snippert HJ, Clevers H, Pettersson S, Pachnis V. 2015. Microbiota controls the homeostasis of glial cells in the gut lamina propria. Neuron 85: 289–295. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.12.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kandel ER, Schwartz JH, Jessel TM. 2000. Principles of Neural Science, 4th ed., McGraw-Hill, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Komuro T, Bałuk P, Burnstock G. 1982. An ultrastructural study of neurons and non-neuronal cells in the myenteric plexus of the rabbit colon. Neuroscience 7: 1797–1806. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90037-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. 1996. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol 116: 71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mantani Y, Haruta T, Nakanishi S, Sakata N, Yuasa H, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N. 2021. Ultrastructural and phenotypical diversity of macrophages in the rat ileal mucosa. Cell Tissue Res 385: 697–711. doi: 10.1007/s00441-021-03457-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantani Y, Haruta T, Nishida M, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N, Kitagawa H. 2019. Three-dimensional analysis of fibroblast-like cells in the lamina propria of the rat ileum using serial block-face scanning electron microscopy. J Vet Med Sci 81: 454–465. doi: 10.1292/jvms.18-0654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakanishi S, Mantani Y, Haruta T, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N. 2020. Three-dimensional analysis of neural connectivity with cells in rat ileal mucosa by serial block-face scanning electron microscopy. J Vet Med Sci 82: 990–999. doi: 10.1292/jvms.20-0175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakanishi S, Mantani Y, Ohno N, Morishita R, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N. 2023. Histological study on regional specificity of the mucosal nerve network in the rat large intestine. J Vet Med Sci 85: 123–134. doi: 10.1292/jvms.22-0433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nasser Y, Keenan CM, Ma AC, McCafferty DM, Sharkey KA. 2007. Expression of a functional metabotropic glutamate receptor 5 on enteric glia is altered in states of inflammation. Glia 55: 859–872. doi: 10.1002/glia.20507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakata N, Mantani Y, Nakanishi S, Morishita R, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N. 2022. Histological study of diurnal changes in bacterial settlement in the rat alimentary tract. Cell Tissue Res 389: 71–83. doi: 10.1007/s00441-022-03626-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, Tinevez JY, White DJ, Hartenstein V, Eliceiri K, Tomancak P, Cardona A. 2012. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spassky N, de Castro F, Le Bras B, Heydon K, Quéraud-LeSaux F, Bloch-Gallego E, Chédotal A, Zalc B, Thomas JL. 2002. Directional guidance of oligodendroglial migration by class 3 semaphorins and netrin-1. J Neurosci 22: 5992–6004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-14-05992.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tamura S, Mantani Y, Nakanishi S, Ohno N, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N. 2022. Region specificity of fibroblast-like cells in the mucosa of the rat large intestine. Cell Tissue Res 389: 427–441. doi: 10.1007/s00441-022-03660-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.von Boyen GB, Steinkamp M, Reinshagen M, Schäfer KH, Adler G, Kirsch J. 2006. Nerve growth factor secretion in cultured enteric glia cells is modulated by proinflammatory cytokines. J Neuroendocrinol 18: 820–825. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2006.01478.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamamoto K, Qi WM, Yokoo Y, Miyata H, Udayanga KGS, Kawano J, Yokoyama T, Hoshi N, Kitagawa H. 2009. Histoplanimetrical study on the spatial relationship of distribution of indigenous bacteria with mucosal lymphatic follicles in alimentary tract of rat. J Vet Med Sci 71: 621–630. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yokoo Y, Miyata H, Udayanga KGS, Qi WM, Takahara E, Mantani Y, Yokoyama T, Kawano J, Hoshi N, Kitagawa H. 2011. Immunohistochemical and histoplanimetrical study on the spatial relationship between the settlement of indigenous bacteria and the secretion of bactericidal peptides in rat alimentary tract. J Vet Med Sci 73: 1043–1050. doi: 10.1292/jvms.11-0114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.