Abstract

间质表皮转化因子(mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor, MET)基因改变参与了非小细胞肺癌的增殖、侵袭和转移。MET-酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(tyrosine kinase inhibitors, TKIs)已获批用于MET基因改变的非小细胞肺癌,而这些药物的耐药不可避免。MET-TKIs的分子耐药机制错综复杂,尚不完全清楚。本文主要对这些MET-TKIs的潜在耐药机制进行综述,以期为MET基因改变的患者提供合理的治疗思路。

Keywords: 肺肿瘤, 间质表皮转化因子, 靶向治疗, 耐药, 治疗策略

Abstract

Mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor (MET) gene alterations involve in the proliferation, invasion, and metastasis of non-small cell lung cancer. MET-tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have been approved to treat non-small cell lung cancer with MET alterations, and resistance to these TKIs is inevitable. Molecular mechanisms of resistance to MET-TKIs are completely unclear. The review focused on potential mechanisms of MET-TKIs resistance and therapeutics strategies to delay and prevent resistance.

Keywords: Lung neoplasms, Mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor, Targeted therapy, Drug resistance, Treatment strategy

近年来多个靶向药物获批用于治疗非小细胞肺癌(non-small cell lung cancer, NSCLC),大大延长了患者的生存[1]。间质表皮转化因子(mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor, MET)作为NSCLC的一个重要驱动基因,存在MET基因14号外显子跳跃突变(MET exon 14 skipping mutation, METex14)、MET扩增、过表达、融合和错义突变等多种活化形式[2]。目前多种MET抑制剂获批上市,其发生耐药不可避免,本文将阐述MET酪氨酸激酶受体抑制剂(MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors, MET-TKIs)耐药的机制,并分析其临床对策。

1 MET分子及NSCLC中MET的突变方式

MET属于跨膜受体酪氨酸激酶家族,其基因位于染色体7q21-q31,长度约为125 kb,含有21个外显子[3]。MET与其配体肝细胞生长因子(hepatocyte growth factor, HGF)结合后,形成同源二聚体,使胞内区(Y1234/1235、Y1349/1356)发生磷酸化[4],通过SH2结构域招募下游多种效应分子,进而激活细胞外信号调节激酶/丝裂原活化蛋白激酶(extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen activated protein kinase, ERK/MAPK)、磷脂酰肌醇3-激酶/丝氨酸-苏氨酸蛋白激酶B(phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/protein kinase B, PI3K/AKT)、酪氨酸激酶/信号传导子和转录激活子(Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription, JAK/STAT)和核因子κB(nuclear factor kappa B, NF-κB)等信号通路,调控细胞增殖迁移与浸润、上皮间质转化、血管生成、抗凋亡、细胞干性维持等过程[5]。MET通路存在多种负向调节方式,包括位于14号外显子的Y1003残基介导的泛素化降解[6]、蛋白激酶C(protein kinase C, PKC)介导的S985残基磷酸化负向调节MET活性[7]、Ca2+-丝氨酸激酶相关的负调节机制[8]等。

MET作为癌基因,存在多种变异,参与恶性肿瘤的发生[9]。在NSCLC中,METex14导致MET基因转录后的14号外显子被错误剪接,致使MET稳定性增加并持续激活[10]。METex14在肺腺癌中发生率为3%-4%[11,12],在较罕见的肉瘤样肺癌中发生率较高,为13%-22%[13,⇓-15]。MET扩增(MET amplification, METamp)包括多倍体形成和基因局部扩增两种方式,其中局部扩增具有更高的HGF配体非依赖性[16]。METamp在原发性变异中发生率为2%-5%[17],在表皮生长因子受体-酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(epidermal growth factor receptor-tyrosine kinase inhibitors, EGFR-TKIs)继发性耐药中发生率较高,为5%-20%[18,19]。MET蛋白过表达可由METex14、METamp等多种基因变异引起[20],在NSCLC发生率为35%-72%[17,21]。上述METex14、METamp以及MET过表达均已证实对MET-TKIs敏感。而MET融合(MET fusion)及MET酪氨酸激酶结构域(MET-tyrosine kinase domain, MET-TKD)突变在NSCLC中更为罕见,其中MET融合突变均为个案报道,如MET-KIF5B[22]、MET-STARD3NL[23]、MET-HLA-DRB1[24]、MET-ATXN7L1[25],均对克唑替尼(Crizotinib)治疗产生应答。MET-TKD突变在初治NSCLC患者中比例为0.06%,其中占比最多的为H1094Y[26,27]。

2 MET-TKIs

目前已获批用于肺癌的MET-TKIs依其作用机制可分为:I和II类。I类TKIs结合于MET催化结构域;II类TKIs结合于MET调节性结构域[28,29]。

2.1 I类MET-TKIs

目前获批用于METex14突变的NSCLC抑制剂均为I类MET抑制剂,通过与MET活化环中的Y1230结合,占用ATP结合袋抑制MET活性。Ia类与MET分子为非特异性结合,代表药物为克唑替尼(Crizotinib)。Ib类为MET高选择性抑制剂,有卡马替尼(Capmatinib)、特泊替尼(Tepotinib)、赛沃替尼(Savolitinib)与谷美替尼(Gumarontinib)等[30,31]。

在一项II期GEOMETRY mono-1多中心研究[32]中,卡马替尼在初治METex14阳性的晚期NSCLC患者中客观缓解率(objective response rate, ORR)达68%,中位缓解持续时间(median duration of response, mDoR)为12.6个月,中位无进展生存期(median progression-free survival, mPFS)为12.4个月,在经治患者中ORR为41%。而在METamp(拷贝数≥10)初治NSCLC患者中的ORR为40%,在经治患者中ORR为29% 。VISION研究[33]中,特泊替尼在METex14阳性的初治或经治NSCLC患者中的ORR为45%,mDoR为11.1个月,mPFS为8.9个月,且安全可耐受。赛沃替尼是我国首个获批的MET抑制剂,在II期临床研究(NCT02897479)[34]中,赛沃替尼治疗METex14阳性的不可切除或转移性肺肉瘤样癌或其他类型NSCLC的ORR为49.2%,且表现出良好的安全性和耐受性。谷美替尼于2023年3月8日获批上市,用于治疗具有METex14突变的局部晚期或转移性NSCLC。在GLORY研究[31]中,整体患者的ORR为66%,mPFS为8.5个月,在初治和经治患者中分别为11.7和7.6个月。

Ia类代表药物克唑替尼结合MET溶剂前沿的G1163残基发挥作用,G1163R突变可导致克唑替尼耐药,对Ib类抑制剂敏感,这也是克唑替尼疗效逊于Ib类MET-TKIs的原因之一。克唑替尼目前批准用于治疗间变性淋巴瘤激酶(anaplastic lymphoma kinase, ALK)、c-ros肉瘤致癌因子-受体酪氨酸激酶(ROS proto-oncogene 1, receptor tyrosine kinase, ROS1)突变阳性的局部晚期或转移性NSCLC。在PROFILE 1001临床研究[35]中,克唑替尼用于METex14阳性的NSCLC患者ORR为32%,mDoR为9.1个月,mPFS为7.3个月,疗效低于高选择性MET-TKIs。同样,克唑替尼对于METamp患者的疗效也非常有限[36,37]。

2.2 II类MET-TKIs

相较于Ib类MET-TKIs的高选择性,II类TKIs为ATP竞争性的、多靶点的小分子TKIs[30],包括卡博替尼(Cabozantinib)、美乐替尼(Merestinib)、格来替尼(Glesatinib)和福瑞替尼(Foretinib)。卡博替尼为多靶点广谱TKIs,作用位点包括MET、血管内皮生长因子受体(vascular endothelial growth factor receptor, VEGFR)、ROS1、RET等,对METex14患者有一定疗效[38]。美乐替尼(LY2801653)作用靶点包括MET、RON、FLT3、ROS1、MERTK、AXL等多个受体酪氨酸激酶,II期临床研究正在进行(NCT02920996)。格来替尼(MGCD265)是MET、AXL、血小板衍生生长因子受体(platelet-derived growth factor receptor, PDGFR)家族等多靶点的抑制剂,已在I期临床研究中证实针对MET变异NSCLC患者中的ORR为30.0%[39]。福瑞替尼(GSK1363089)是MET、AXL、VEGFR等多靶点的抑制剂,在携带胚系MET突变的晚期乳头状肾癌中的ORR达到50%[40],在NSCLC中的疗效尚待证实。

3 MET-TKIs耐药机制

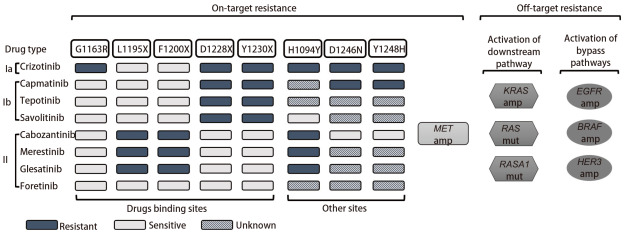

近年来多个MET-TKIs研发上市,使许多MET基因改变的NSCLC患者获得生存获益,但在治疗中仍会发生原发性和继发性耐药。原发性耐药通常指MET改变的患者对MET-TKIs无法产生初始治疗应答,在卡马替尼、特泊替尼和赛沃替尼治疗中的发生率为4%-19.2%[32,34,41]。一项回顾性研究[42]发现,65例METex14阳性NSCLC的耐药患者,3例在治疗前即存在PIK3CA共突变,均在初次疗效评价时出现疾病进展。因此推测,旁路或下游途径存在激活变异是导致原发性耐药的主要机制。继发性耐药通常表现为患者对MET-TKIs治疗产生治疗应答数月或数年后出现进展,目前被认为是TKIs治疗的最大挑战。按照发生机制的不同,继发性耐药通常被分为MET依赖型耐药与非MET依赖型耐药(图1)。MET依赖型约占1/3[26],包括MET的二次突变、MET基因扩增等。非MET依赖型耐药指MET下游信号的活化和旁路途径的激活等。

图1. MET-TKIs的获得性耐药分为MET依赖型耐药机制与非MET依赖型耐药机制。MET依赖型耐药包括MET分子的二次点突变与MET扩增。非MET依赖型耐药包括了MET下游通路与旁路信号通路的激活。谷美替尼因上市时间短无相关报道。.

3.1 MET依赖型耐药机制

已知MET D1228、Y1230、G1163、L1195、F1200等位点的突变以及MET基因扩增,参与了MET-TKIs的获得性耐药。这些突变位点常参与MET-TKIs与MET分子的结合。Ib类高选择性MET-TKIs的主要耐药突变位点为D1228X与Y1230X[43]。其中Y1230是Ib类TKIs与MET结合的重要氨基酸残基,而D1228参与MET激酶与ATP的结合[44]。Ia类药物克唑替尼耐药突变包括了D1228X与Y1230X[43]。克唑替尼同时需要与溶剂前沿残基G1163结合发挥抑制作用[44],因此克唑替尼的耐药突变还包括G1163X[43]。

II类MET-TKIs的耐药突变有L1195X和F1200X[43]。II类MET-TKIs与非活化的MET分子的结合,位于ATP结合疏水口袋附近的L1195与F1200残基发挥了重要作用[28,43]。

在临床实践中,建议MET-TKIs耐药后进行二次活检及第二代测序技术(next-generation sequencing, NGS)检测,了解耐药机制,寻找个体化的治疗方案。Recondo等[26]报道了3例携带METex14的NSCLC患者应用克唑替尼耐药后分别检测出D1228H、D1228N、Y1230C突变,另有1例患者应用克唑替尼耐药后在血浆中检测出G1163R、D1228H/N、Y1230H/S、L1195V共突变。1例患者应用卡马替尼耐药后出现D1228N突变。除上述耐药突变位点外,H1094Y、Y1248H、D1246N也可能参与了MET依赖型耐药。1例应用格来替尼进展后出现H1094Y、L1195V共突变。2例MET过表达的NSCLC患者分别应用克唑替尼和卡马替尼,进展后分别出现Y1248H、D1246N突变[45]。

在体外研究[28,43]中,已证实的耐药突变还包括G1090A(I类耐药)、V1092I/L(Ia类耐药)、D1133V(II类耐药)。MET 14号外显子等位基因扩增也是MET-TKIs的潜在耐药机制。1例METamp患者应用格来替尼后出现17个MET 14号外显子等位突变,更换为克唑替尼后MET扩增至47个[26]。

MET基因改变是EGFR-TKIs治疗的耐药机制之一,MET-TKIs与EGFR-TKIs联合治疗可作为二线方案。一项回顾性研究[27],对20例二线应用MET-TKIs联合EGFR-TKIs治疗的NSCLC患者出现耐药后再次进行NGS,发现L1195V(4例)、D1228H(8例)/N(15例)/Y(2例)、Y1230C(2例)/H(3例)、ALK融合(1例)、BRAF突变(3例),其中部分为共突变,另有1例出现D1228_M1229delinFL突变,推测MET-TKIs作为二线治疗的耐药机制更为复杂,可能由多种机制共同构成,尚需进一步研究证实。

3.2 非MET依赖型耐药机制

非MET依赖型耐药机制主要指不依赖于MET分子活化而导致的信号转导异常,可大致分为MET下游通路的异常激活(如与RAS/MAPK通路、PI3K/AKT通路有关的变异)和旁路途径的过度激活[如EGFR、靶向人表皮生长因子受体2/3(human epidermal growth factor receptor 2/3, HER2/3)、鼠类肉瘤病毒癌基因同源物B1(v-raf murine sar-coma viral oncogene homolog B1, BRAF)的扩增激活]。在20例经MET-TKIs治疗的METex14阳性NSCLC患者中,有9例(45%)分别出现KRAS扩增、KRAS点突变以及EGFR、HER3、BRAF扩增[26]。Guo等[46]报道了33%(5/15)经MET-TKIs治疗的患者发生MET非依赖性耐药,包括了KRAS扩增和点突变、RASA1突变以及EGFR扩增。目前针对MET非依赖型耐药机制的研究主要通过对MET-TKIs耐药患者的血液或组织学样本进行DNA或RNA水平检测来进行,因此表观遗传水平、蛋白表达水平的变异尚不能明确,尚有25%-47%的患者无法明确耐药机制[26,46]。Ia类克唑替尼应用于ALK融合突变阳性的NSCLC患者后可能出现P-糖蛋白(P-glycoprotein, P-gp)过表达,导致药物转运异常产生耐药[47,48]。因此推测药物转运异常也是MET-TKIs耐药机制之一。组织学类型转化是EGFR-TKIs治疗后耐药的机制之一[49],目前尚未有MET-TKIs治疗耐药后出现组织学类型转化的病例报道。

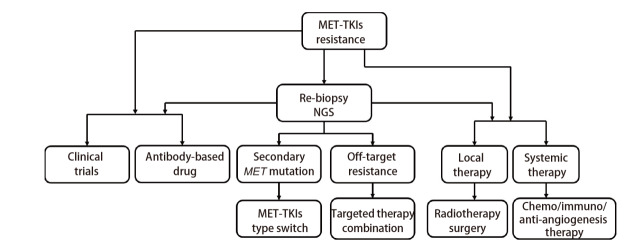

4 MET-TKIs耐药后治疗策略

发生MET-TKIs耐药后,通过二次活检及NGS明确耐药机制,是选择后续治疗方案的重要依据。对于NGS可明确的耐药机制,可寻求靶向治疗或联合靶向治疗。对于机制未明的疾病进展,则需要进行其他局部治疗或全身治疗。下面分别从靶向治疗策略及其他治疗策略讨论MET-TKIs耐药后的治疗选择。

4.1 靶向治疗策略

20%-35%的患者进行耐药后分子诊断可能发现MET依赖型耐药机制[26,46]。其中,约有1/3的MET依赖型机制导致的耐药可通过I/II类MET-TKIs序贯治疗解决,但临床证据有限[26,50,51]。如前所述,I/II类MET-TKIs诱导的耐药突变发生于不同位点,为I/II类MET-TKIs序贯治疗提供了分子基础[43]。I/II类MET-TKIs序贯应用可克服耐药首先在2017年被提出[44]。而后许多研究[43,52,53]通过体外或体内研究证实了序贯治疗的有效性。D1228H/N、Y1230C/H/S为常见Ib类MET-TKIs的特征性耐药突变,可尝试II类MET-TKIs治疗。G1163R为Ia类克唑替尼的特征性耐药突变,对Ib类(卡马替尼、赛沃替尼)和II类(美乐替尼)MET-TKIs为敏感突变[43]。对于II类MET-TKIs的耐药突变L1195F/V与F1200I/L,换用I类MET-TKIs可抑制肿瘤生长[43,52]。在一项II期临床研究[54]中,部分克唑替尼治疗后的METex14阳性NSCLC患者换用卡马替尼治疗后有一定临床获益,ORR为13%(2/15),疾病控制率(disease control rate, DCR)为80%(12/15)。Bahcall等[50]报道了1例MET D1228V导致的克唑替尼耐药,在应用卡博替尼后再次获得缓解。Klempner等[55]报道了携带METex14的NSCLC患者应用克唑替尼进展后换用卡博替尼后继续获益。

对于Y1248H、D1246N、H1094Y突变,也有体内外研究证实序贯治疗的有效性。Y1248H、D1246N分别出现在I类克唑替尼、卡马替尼治疗后,体外实验[45]证实其对II类TKIs敏感。1例具有METex14合并MET C526F突变的NSCLC患者应用克唑替尼进展后D1246N突变,更换为卡博替尼后再次达到部分缓解[56]。H1094Y产生于II类MET-TKIs格来替尼治疗后,并经体外实验证实对Ib类赛沃替尼敏感[26]。

尚有部分MET依赖型耐药不能通过序贯治疗克服。如D1228A/Y在体外研究[43]中证实对I/II类MET-TKIs均耐药。耐药共突变,如D1228H/N、Y1230H/S与L1195V和G1163R共突变在1例克唑替尼耐药患者的血浆样本中检测到[26],对治疗选择提出新挑战。对于MET扩增导致MET-TKIs耐药的患者,序贯MET-TKIs治疗无效[26]。对于上述耐药机制,也可尝试MET单抗或EGFR/c-MET双特异性抗体。在I期CHRYSTALIS研究[57]中,19例经MET-TKIs治疗后的NSCLC患者应用埃万妥单抗(Amivantamab)治疗,ORR为21%(4/19),临床获益率为57.9%(11/19)。MET单抗Sym-015用于既往应用过MET-TKIs的NSCLC患者DCR为60%,mPFS为5.4个月[58]。

非MET依赖型耐药机制可通过MET-TKIs与靶向其他靶点的药物联合应用来克服。对于下游RAS/MAPK通路激活,体外实验[59]已经证实,MET-TKIs联合MEK抑制剂能够抑制携带METex14-KRAS G12D共突变细胞的生长。对于下游PI3K/AKT通路的激活,临床前研究[42]已证实联合应用MET-TKIs与PI3K抑制剂的有效性。旁路途径激活,如EGFR扩增、HER2扩增、BRAF扩增,同样可通过靶向联合治疗克服。对于EGFR扩增导致的MET-TKIs耐药,EGFR/c-MET双特异性抗体埃万妥单抗具有一定疗效[60,⇓-62]。针对HER2扩增或BRAF扩增,联合应用MET-TKIs与相应靶向药物理论上能够产生疗效。

MET抗体偶联药物(antibody-drug conjugate, ADC)类药物已进入临床研究阶段,Teliso-V已获得美国食品药品监督管理局(Food and Drug Administration, FDA)突破性认定,用于含铂治疗后进展的晚期MET阳性、EGFR野生型NSCLC患者[63]。Ib期研究入组了20例经MET-TKIs治疗进展的患者,疗效尚在观察中。

4.2 局部或其他全身治疗策略

在临床应用中,部分靶向治疗患者的进展表现为寡进展。可尝试在继续接受MET-TKIs治疗的基础上联合局部治疗[64]。寡进展通常被定义为出现在一处或有限数量器官的小病灶转移,且患者整体病情控制稳定,反映肿瘤存在异质性[65]。已有临床研究[66,67]证实立体定向放疗用于寡进展的驱动基因阳性的NSCLC患者可改善其PFS。对于孤立的脑实质转移或进展,继续MET-TKIs治疗基础上联合立体定向放疗或手术治疗也能够使患者获益。对于脑多个病灶转移或进展,可考虑全颅放疗,也可选择更高血脑屏障透过率的药物[68]。

25%-47%的患者无法经二次活检及NGS明确耐药机制,或虽可明确耐药机制但无对应靶向治疗方案。对于这部分患者,如出现明显症状、广泛的疾病进展,应进行含铂双药化疗、免疫治疗、抗血管治疗或联合治疗。MET变异发生率较低,相关报道较少。在EGFR-TKIs治疗后进展的患者中,细胞毒药物因杀伤肿瘤细胞的作用机制与TKIs治疗不同,能在TKIs耐药后发挥抗肿瘤作用[69]。相较于驱动基因阴性的NSCLC患者,携带METex14的NSCLC患者通常具有更高水平的程序性死亡配体1(programmed death ligand 1, PD-L1)表达。METex14患者中PD-L1高表达的比例为84%,而野生型患者PD-L1高表达比例为59%[11]。但对于MET-TKIs耐药NSCLC患者而言,单纯应用免疫检查点抑制剂(immune checkpoint inhibitors, ICIs)疗效有限,可考虑免疫联合化疗及抗血管治疗[70]。对于ICIs与MET-TKIs联合治疗的安全性及有效性仍需要进一步探讨[33]。图2展示了MET-TKIs耐药后的治疗选择。

图2. MET-TKIs耐药后治疗决策的流程图.

5 总结与展望

MET突变是具有靶向治疗价值的致癌驱动基因,随着近年来的临床前和临床研究已经证实了HGF-MET通路在多种恶性肿瘤,特别是NSCLC中的重要性及治疗潜力。但MET-TKIs靶向治疗后发生获得性耐药是不可避免的。近年来分子诊断技术不断发展,MET-TKIs治疗失败后可能的耐药分子机制已进行了初步的探索,如MET点突变、METamp、旁路途径激活等导致耐药,仍有部分患者无法通过分子诊断明确耐药机制。对于MET-TKIs耐药后的治疗策略,需要对患者的体能状态(performance status, PS)评分、进展状态、耐药机制、既往治疗经过及安全性等方面进行综合考量。目前可选择的治疗策略包括更换MET-TKIs类型、靶向联合治疗、局部治疗、化学治疗或±ICIs、±抗血管等治疗模式。寻求临床研究对MET-TKIs耐药的患者也是一个很好的选择。新一代的MET-TKIs研发同样重要,通过分子诊断明确耐药机制并对TKIs类药物进行更新,改善患者临床获益。同时也期待MET-ADC、双特异性抗体等其他治疗药物有新的临床研究数据报道。

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

参 考 文 献

- 1. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, et al. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin, 2022, 72(1): 7-33. doi: 10.3322/caac.21708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Van Der Steen N, Giovannetti E, Pauwels P, et al. cMET exon 14 skipping: from the structure to the clinic. J Thorac Oncol, 2016, 11(9): 1423-1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sierra JR, Tsao MS. . c-MET as a potential therapeutic target and biomarker in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol, 2011, 3(1 Suppl): S21-S35. doi: 10.1177/1758834011422557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Owusu BY, Galemmo R, Janetka J, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor, a key tumor-promoting factor in the tumor microenvironment. Cancers (Basel), 2017, 9(4): 35. doi: 10.3390/cancers9040035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Scagliotti GV, Novello S, von Pawel J. . The emerging role of MET/HGF inhibitors in oncology. Cancer Treat Rev, 2013, 39(7): 793-801. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sacco JJ, Clague MJ. . Dysregulation of the Met pathway in non-small cell lung cancer: implications for drug targeting and resistance. Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2015, 4(3): 242-252. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2218-6751.2015.03.05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Santarpia M, Massafra M, Gebbia V, et al. A narrative review of MET inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. Transl Lung Cancer Res, 2021, 10(3): 1536-1556. doi: 10.21037/tlcr-20-1113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gandino L, Munaron L, Naldini L, et al. Intracellular calcium regulates the tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the MET oncogene. J Biol Chem, 1991, 266(24): 16098-16104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Koch JP, Aebersold DM, Zimmer Y, et al. MET targeting: time for a rematch. Oncogene, 2020, 39(14): 2845-2862. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1193-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lu X, Peled N, Greer J, et al. MET exon 14 mutation encodes an actionable therapeutic target in lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res, 2017, 77(16): 4498-4505. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-16-1944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lee JK, Madison R, Classon A, et al. Characterization of non-small-cell lung cancers with MET exon 14 skipping alterations detected in tissue or liquid: clinicogenomics and real-world treatment patterns. JCO Precis Oncol, 2021, 5: PO. 21.00122. doi: 10.1200/po.21.00122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Le X, Hong L, Hensel C, et al. Landscape and clonal dominance of co-occurring genomic alterations in non-small-cell lung cancer harboring MET exon 14 skipping. JCO Precis Oncol, 2021, 5: PO. 21.00135. doi: 10.1200/po.21.00135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schrock AB, Frampton GM, Suh J, et al. Characterization of 298 patients with lung cancer harboring MET exon 14 skipping alterations. J Thorac Oncol, 2016, 11(9): 1493-1502. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Liu X, Jia Y, Stoopler MB, et al. Next-generation sequencing of pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinoma reveals high frequency of actionable MET gene mutations. J Clin Oncol, 2016, 34(8): 794-802. doi: 10.1200/jco.2015.62.0674 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vuong HG, Ho ATN, Altibi AMA, et al. Clinicopathological implications of MET exon 14 mutations in non-small cell lung cancer - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lung Cancer, 2018, 123: 76-82. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Onozato R, Kosaka T, Kuwano H, et al. Activation of MET by gene amplification or by splice mutations deleting the juxtamembrane domain in primary resected lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol, 2009, 4(1): 5-11. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181913e0e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Salgia R. . MET in lung cancer: biomarker selection based on scientific rationale. Mol Cancer Ther, 2017, 16(4): 555-565. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-16-0472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yu HA, Suzawa K, Jordan E, et al. Concurrent alterations in EGFR-mutant lung cancers associated with resistance to EGFR kinase inhibitors and characterization of MTOR as a mediator of resistance. Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(13): 3108-3118. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-2961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Schoenfeld AJ, Chan JM, Kubota D, et al. Tumor analyses reveal squamous transformation and off-target alterations as early resistance mechanisms to first-line osimertinib in EGFR-mutant lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2020, 26(11): 2654-2663. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-19-3563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guo R, Berry LD, Aisner DL, et al. MET IHC is a poor screen for MET amplification or MET exon 14 mutations in lung adenocarcinomas: data from a tri-institutional cohort of the lung cancer mutation consortium. J Thorac Oncol, 2019, 14(9): 1666-1671. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.06.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ichimura E, Maeshima A, Nakajima T, et al. Expression of c-met/HGF receptor in human non-small cell lung carcinomas in vitro and in vivo and its prognostic significance. Jpn J Cancer Res, 1996, 87(10): 1063-1069. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1996.tb03111.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Riedel R, Fassunke J, Tumbrink HL, et al. Resistance to MET inhibition in MET-dependent NSCLC and therapeutic activity after switching from type I to type II MET inhibitors. Eur J Cancer, 2023, 179: 124-135. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2022.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Plenker D, Bertrand M, de Langen AJ, et al. Structural alterations of MET trigger response to MET kinase inhibition in lung adenocarcinoma patients. Clin Cancer Res, 2018, 24(6): 1337-1343. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-3001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kim P, Jia P, Zhao Z. . Kinase impact assessment in the landscape of fusion genes that retain kinase domains: a pan-cancer study. Brief Bioinform, 2018, 19(3): 450-460. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Zhu YC, Wang WX, Xu CW, et al. Identification of a novel crizotinib-sensitive MET-ATXN7L 1 gene fusion variant in lung adenocarcinoma by next generation sequencing. Ann Oncol, 2018, 29(12): 2392-2393. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdy455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Recondo G, Bahcall M, Spurr LF, et al. Molecular mechanisms of acquired resistance to MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors in patients with MET exon 14-mutant NSCLC. Clin Cancer Res, 2020, 26(11): 2615-2625. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-19-3608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yao Y, Yang H, Zhu B, et al. Mutations in the MET tyrosine kinase domain and resistance to tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. Respir Res, 2023, 24(1): 28. doi: 10.1186/s12931-023-02329-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Roskoski R Jr. . Classification of small molecule protein kinase inhibitors based upon the structures of their drug-enzyme complexes. Pharmacol Res, 2016, 103: 26-48. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gherardi E, Birchmeier W, Birchmeier C, et al. Targeting MET in cancer: rationale and progress. Nat Rev Cancer, 2012, 12(2): 89-103. doi: 10.1038/nrc3205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chu C, Rao Z, Pan Q, et al. An updated patent review of small-molecule c-Met kinase inhibitors (2018-present). Expert Opin Ther Pat, 2022, 32(3): 279-298. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2022.2008356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yu Y, Zhou J, Li X, et al. Gumarontinib in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring MET exon 14 skipping mutations: a multicentre, single-arm, open-label, phase 1b/2 trial. EClinicalMedicine, 2023, 59: 101952. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wolf J, Seto T, Han JY, et al. Capmatinib in MET exon 14-mutated or MET-amplified non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(10): 944-957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Le X, Sakai H, Felip E, et al. Tepotinib efficacy and safety in patients with MET exon 14 skipping NSCLC: outcomes in patient subgroups from the VISION study with relevance for clinical practice. Clin Cancer Res, 2022, 28(6): 1117-1126. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-21-2733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lu S, Fang J, Li X, et al. Once-daily savolitinib in Chinese patients with pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas and other non-small-cell lung cancers harbouring MET exon 14 skipping alterations: a multicentre, single-arm, open-label, phase 2 study. Lancet Respir Med, 2021, 9(10): 1154-1164. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(21)00084-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Drilon A, Clark JW, Weiss J, et al. Antitumor activity of crizotinib in lung cancers harboring a MET exon 14 alteration. Nat Med, 2020, 26(1): 47-51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0716-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Landi L, Chiari R, Tiseo M, et al. Crizotinib in MET-deregulated or ROS1-rearranged pretreated non-small cell lung cancer (METROS): a phase II, prospective, multicenter, two-arms trial. Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 25(24): 7312-7319. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-19-0994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Moro-Sibilot D, Cozic N, Pérol M, et al. Crizotinib in c-MET- or ROS1-positive NSCLC: results of the AcSé phase II trial. Ann Oncol, 2019, 30(12): 1985-1991. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang SXY, Zhang BM, Wakelee HA, et al. Case series of MET exon 14 skipping mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancers with response to crizotinib and cabozantinib. Anticancer Drugs, 2019, 30(5): 537-541. doi: 10.1097/cad.0000000000000765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kollmannsberger C, Hurwitz H, Bazhenova L, et al. Phase I study evaluating glesatinib (MGCD265), an inhibitor of MET and AXL, in patients with non-small cell lung cancer and other advanced solid tumors. Target Oncol, 2023, 18(1): 105-118. doi: 10.1007/s11523-022-00931-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Choueiri TK, Vaishampayan U, Rosenberg JE, et al. Phase II and biomarker study of the dual MET/VEGFR2 inhibitor foretinib in patients with papillary renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol, 2013, 31(2): 181-186. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.43.3383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Paik PK, Felip E, Veillon R, et al. Tepotinib in non-small-cell lung cancer with MET exon 14 skipping mutations. N Engl J Med, 2020, 383(10): 931-943. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Jamme P, Fernandes M, Copin MC, et al. Alterations in the PI3K pathway drive resistance to MET inhibitors in NSCLC harboring MET exon 14 skipping mutations. J Thorac Oncol, 2020, 15(5): 741-751. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2020.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fujino T, Kobayashi Y, Suda K, et al. Sensitivity and resistance of MET exon 14 mutations in lung cancer to eight MET tyrosine kinase inhibitors in vitro. J Thorac Oncol, 2019, 14(10): 1753-1765. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Reungwetwattana T, Liang Y, Zhu V, et al. The race to target MET exon 14 skipping alterations in non-small cell lung cancer: the why, the how, the who, the unknown, and the inevitable. Lung Cancer, 2017, 103: 27-37. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Li A, Yang JJ, Zhang XC, et al. Acquired MET Y1248H and D1246N mutations mediate resistance to MET inhibitors in non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(16): 4929-4937. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-16-3273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Guo R, Offin M, Brannon AR, et al. MET exon 14-altered lung cancers and MET inhibitor resistance. Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 27(3): 799-806. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-20-2861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tang SC, Nguyen LN, Sparidans RW, et al. Increased oral availability and brain accumulation of the ALK inhibitor crizotinib by coadministration of the P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) and breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) inhibitor elacridar. Int J Cancer, 2014, 134(6): 1484-1494. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Katayama R, Sakashita T, Yanagitani N, et al. P-glycoprotein mediates ceritinib resistance in anaplastic lymphoma kinase-rearranged non-small cell lung cancer. EBioMedicine, 2016, 3: 54-66. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Oser MG, Niederst MJ, Sequist LV, et al. Transformation from non-small-cell lung cancer to small-cell lung cancer: molecular drivers and cells of origin. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 16(4): e165-e172. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(14)71180-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bahcall M, Sim T, Paweletz CP, et al. Acquired METD1228V mutation and resistance to MET inhibition in lung cancer. Cancer Discov, 2016, 6(12): 1334-1341. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.Cd-16-0686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Remon J, Hendriks LEL, Mountzios G, et al. MET alterations in NSCLC-current perspectives and future challenges. J Thorac Oncol, 2023, 18(4): 419-435. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.10.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Engstrom LD, Aranda R, Lee M, et al. Glesatinib exhibits antitumor activity in lung cancer models and patients harboring MET exon 14 mutations and overcomes mutation-mediated resistance to type I MET inhibitors in nonclinical models. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(21): 6661-6672. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-17-1192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fujino T, Suda K, Koga T, et al. Foretinib can overcome common on-target resistance mutations after capmatinib/tepotinib treatment in NSCLCs with MET exon 14 skipping mutation. J Hematol Oncol, 2022, 15(1): 79. doi: 10.1186/s13045-022-01299-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dagogo-Jack I, Moonsamy P, Gainor JF, et al. A phase 2 study of capmatinib in patients with MET-altered lung cancer previously treated with a MET inhibitor. J Thorac Oncol, 2021, 16(5): 850-859. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2021.01.1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Klempner SJ, Borghei A, Hakimian B, et al. Intracranial activity of cabozantinib in MET exon 14-positive NSCLC with brain metastases. J Thorac Oncol, 2017, 12(1): 152-156. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.09.127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Jin W, Shan B, Liu H, et al. Acquired mechanism of crizotinib resistance in NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping. J Thorac Oncol, 2019, 14(7): e137-e139. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Krebs MG, Spira AI, Cho BC, et al. Amivantamab in patients with NSCLC with MET exon 14 skipping mutation: Updated results from the CHRYSALIS study. J Clin Oncol, 2022, 40(16_suppl): 9008. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2022.40.16_suppl.9008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Camidge DR, Janku F, Martinez-Bueno A, et al. Safety and preliminary clinical activity of the MET antibody mixture, Sym 015 in advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients with MET amplification/exon 14 deletion (METAmp/Ex14∆). J Clin Oncol, 2020, 38(15_suppl): 9510. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.9510 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Suzawa K, Offin M, Lu D, et al. Activation of KRAS mediates resistance to targeted therapy in MET exon 14-mutant non-small cell lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2019, 25(4): 1248-1260. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-18-1640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science, 2007, 316(5827): 1039-1043. doi: 10.1126/science.1141478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wu YL, Zhang L, Kim DW, et al. Phase Ib/II study of capmatinib (INC280) plus gefitinib after failure of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor therapy in patients with EGFR-mutated, MET factor-dysregulated non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2018, 36(31): 3101-3109. doi: 10.1200/jco.2018.77.7326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Moores SL, Chiu ML, Bushey BS, et al. A novel bispecific antibody targeting EGFR and cMet is effective against EGFR inhibitor-resistant lung tumors. Cancer Res, 2016, 76(13): 3942-3953. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-15-2833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Camidge DR, Morgensztern D, Heist RS, et al. Phase I study of 2- or 3-week dosing of telisotuzumab vedotin, an antibody-drug conjugate targeting c-Met, monotherapy in patients with advanced non-small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2021, 27(21): 5781-5792. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-21-0765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Piper-Vallillo AJ, Sequist LV, Piotrowska Z. . Emerging treatment paradigms for EGFR-mutant lung cancers progressing on osimertinib: a review. J Clin Oncol, 2020: Jco1903123. doi: 10.1200/jco.19.03123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tumati V, Iyengar P. . The current state of oligometastatic and oligoprogressive non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Dis, 2018, 10(Suppl 21): S2537-S2544. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2018.07.19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Campo M, Al-Halabi H, Khandekar M, et al. Integration of stereotactic body radiation therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors in stage IV oncogene-driven lung cancer. Oncologist, 2016, 21(8): 964-973. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Franceschini D, De Rose F, Cozzi S, et al. The use of radiation therapy for oligoprogressive/oligopersistent oncogene-driven non small cell lung cancer: State of the art. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol, 2020, 148: 102894. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2020.102894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hart CD, De Boer RH. . Profile of cabozantinib and its potential in the treatment of advanced medullary thyroid cancer. Onco Targets Ther, 2013, 6: 1-7. doi: 10.2147/ott.S27671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. White MN, Piotrowska Z, Stirling K, et al. Combining Osimertinib with chemotherapy in EGFR-mutant NSCLC at progression. Clin Lung Cancer, 2021, 22(3): 201-209. doi: 10.1016/j.cllc.2021.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Reck M, Mok TSK, Nishio M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab and chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (IMpower150): key subgroup analyses of patients with EGFR mutations or baseline liver metastases in a randomised, open-label phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med, 2019, 7(5): 387-401. doi: 10.1016/s2213-2600(19)30084-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]