Abstract

Objective:

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is a prevalent psychiatric disorder associated with obesity. Few evidence-based treatments exist for BED, particularly pharmacological options. This study tested the efficacy of naltrexone/bupropion for BED.

Methods:

Randomized double-blind placebo-controlled 12-week trial tested naltrexone/bupropion for BED with and without obesity. Eighty-nine patients (70.8% women, 69.7% White, mean age 45.7, mean BMI 35.1 kg/m2, 77.5% with BMI>30kg/m2) were randomized to placebo (N=46) or naltrexone/bupropion (N=43), with randomization stratified by obesity status and gender; 92.1% completed posttreatment assessments.

Results:

Mixed models of binge-eating frequency revealed significant reductions that did not differ significantly between naltrexone/bupropion and placebo. Logistic regression of binge-eating remission rates revealed that naltrexone/bupropion and placebo did not differ significantly. Obesity status did not predict, nor moderate, binge-eating outcomes considered either continuously or categorically. Mixed models revealed naltrexone/bupropion was associated with significantly greater percent weight loss than placebo. Logistic regression revealed naltrexone/bupropion had significantly higher rates of attaining >5% weight loss than placebo (27.9% vs 6.5%). Obesity status did not predict nor moderate weight-loss outcomes.

Conclusions:

Naltrexone/bupropion did not demonstrate effectiveness for reducing binge eating relative to placebo but showed effectiveness for weight reduction in patients with BED. Obesity status did not predict nor moderate medication outcomes.

Keywords: obesity, binge eating, eating disorders, pharmacotherapy, weight loss, treatment

Introduction

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is defined by recurrent episodes of binge eating (i.e., eating unusually large quantities of food while experiencing a subjective sense of loss-of-control), marked distress regarding the binge eating, and the absence of extreme weight-compensatory or purging behaviors that define bulimia nervosa (1). BED is a prevalent (2,3) and costly (4) public health problem. BED is associated strongly with obesity (2,3), elevated rates of psychiatric and medical comorbidities, and functional impairments (2,3,5), and carries heightened risk for future metabolic (6) and medical conditions (2). Although BED, a psychiatric diagnosis, is associated strongly with obesity (2,3), a medical diagnosis, they have distinct behavioral, psychopathological, and neurobiological characteristics (7).

Research has identified some treatments with efficacy for BED (8), but they all have limitations, and there continues to be a pressing need for additional pharmacological options. Specific psychological treatments, particularly cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy, have strong empirical support for BED (8,9,11). These “specialist” psychological treatments, however, are neither widely available nor frequently sought by patients (10) and even with the leading evidence-based interventions, many patients do not cease binge eating entirely and most do not attain weight loss (11). Although obesity is not a criterion for BED, most treatment-seeking patients with BED have obesity and often desire to also address weight and medical needs (12,13).

Currently, the only medication approved for BED by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) is lisdexamfetamine dimesylate (LDX). Despite binge-eating abstinence rates of 32–40% (14,15), LDX is contraindicated for individuals with histories of substance misuse and has a “limitation of use” that it is not recommended for chronic weight management and its safety and efficacy for individuals with obesity remain unknown. Several other “off-label” medications have yielded statistically significant reductions in binge eating (16) but only topiramate reduced both binge eating and weight (17,18). Unfortunately, topiramate has a high discontinuation rate due to limited tolerability and adverse events (19). Antidepressant medications, particularly serotonin reuptake inhibitors, have received some support, albeit mixed (20,21), for reducing binge eating but their impact on weight is varied and not always favorable.

Although several FDA-approved medications are available for weight management for obesity, to date very little research has examined their utility for BED (7) and available research does not support their effectiveness for treating BED. Orlistat, a lipase inhibitor, when added to CBT, did not enhance binge-eating outcomes although it significantly—albeit modestly—enhanced weight-loss (22). Another FDA-approved anti-obesity medication, naltrexone/bupropion combination (23) with demonstrated efficacy in patients with obesity without BED (24), was recently evaluated in three randomized controlled trials (RCTs) for adults with BED and obesity (25,26,27). Since naltrexone/bupropion has hypothesized effects in regulating food intake and weight based on leptin’s mechanisms of action (28,29), it appears relevant for both BED and obesity. A small pilot RCT for BED with obesity (25) revealed significant reductions in binge-eating frequency that did not differ significantly between naltrexone/bupropion and placebo and that a greater proportion of participants attained weight loss with naltrexone/bupropion than placebo. The second RCT (26) evaluated—using a using a 2×2 balanced factorial design—the effectiveness of naltrexone/bupropion and behavioral therapy, alone and in combination, for BED with obesity. Analyses revealed that naltrexone/bupropion was significantly superior to placebo in binge-eating remission rates but not for binge-eating frequency nor for weight reduction whereas behavioral therapy was significantly superior to no behavior therapy consistently across all binge-eating and weight loss outcomes; no significant interactions of behavioral therapy and medication were observed for any outcomes. The third RCT (27) tested the effectiveness of naltrexone/bupropion maintenance treatment amongst responders to acute treatment for BED. Naltrexone/bupropion following response to acute treatment with naltrexone/bupropion was associated with maintenance of binge-eating remission and low binge-eating frequency and significant additional weight loss whereas placebo following response to acute treatment with naltrexone/bupropion was associated with significantly decreased probability of binge-eating remission, significantly increased binge-eating frequency, and no weight loss.

The dearth of pharmacological treatment options for BED (9), the mixed findings for other medications evaluated for BED (9,20,21), and the mixed findings from recent RCTs testing naltrexone/bupropion for BED (25,26,27) indicate the need for further RCT evaluations of naltrexone/bupropion for BED to replicate and extend the knowledge base. The present study was a randomized 12-week double-blind placebo-controlled trial designed to test the acute effectiveness of naltrexone/bupropion for BED. Although BED and obesity are strongly associated, with even more heightened associations in treatment-seeking persons with BED, obesity is neither a required criterion for BED nor is it always present. Except for some early RCTs for BED (e.g., 20), nearly all RCTs of pharmacological treatments for BED (8) have required overweight/obesity as an eligibility criterion. The present RCT was designed to include patients with BED both with and without obesity to enhance generalizability (i.e., epidemiological studies indicate many people with BED do not have co-existing obesity) (2,3) and to allow for the first examination of whether obesity status predicts or moderates treatment outcomes in patients with BED.

METHODS

This single-site 12-week RCT was conducted April 2018 to April 2022. The protocol was approved by the Yale institutional review board and followed a data safety and monitoring plan with a data safety and monitoring board. Participants provided written informed consent.

Participants

Participants (N=89), recruited via advertisements, were eligible if they met DSM-5-defined (1) BED, were 18–70 years old, with a body mass index (BMI) >21.5 to <50.0. Minimal exclusion criteria comprised clinical issues that dictate need for alternative treatment or represent contraindications to naltrexone/bupropion. Exclusionary criteria included: concurrent treatment for eating/weight disorders, taking contraindicated medications (e.g., opiates), uncontrolled medical conditions or contraindications to naltrexone/bupropion (e.g., seizure history, bulimia nervosa history, cardiovascular disease, psychosis/bipolar disorder, systolic blood pressure>160mmHg, diastolic blood pressure>100mmHg, or heart rate>100 beats/minute), and pregnancy/breastfeeding.

Participants had mean age of 45.7 (SD=13.5) years, 70.8% (N=63) were female, 82.0% (N=73) attended/finished college, and 69.7% (N=62) were White. Mean BMI was 35.1 kg/m2 (SD=6.2); 22.5% (N=20) were categorized without obesity and 77.5% (N=69) with obesity.

Assessments

Assessments were performed by doctoral research-clinicians supervised throughout the study. Primary outcomes (binge-eating, measured weight) and secondary outcomes were assessed using well-established interviews, self-report questionnaires, and laboratory tests that measured specific eating/weight disorder constructs and associated psychological/metabolic variables.

Eating Disorder Examination-Interview (EDE; 16th-edition; 30) was administered to diagnose BED and to assess binge-eating frequency and eating-disorder psychopathology at baseline and post-treatment. The EDE has good reliability in studies with BED (31). In this study, inter-rater (N=40) EDE reliability intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were 0.94 (95% CI 0.89–0.97) for binge-eating frequency and 0.98 (95% CI 0.97–0.99) for global score.

Weight and height were measured at baseline and weight was measured at two weeks, one month, two months, and at the end of treatment (i.e., post-treatment). Fasting cholesterol (total, HDL, and LDL) and glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) were measured at baseline and post-treatment.

A self-report battery comprising well-validated measures was completed at baseline, two weeks, one month, two months, and post-treatment. Beck Depression Inventory-II assesses depression symptoms/levels within the past two weeks (32). Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire measures eating behaviors with three scale scores (cognitive restraint, disinhibition, and hunger); it shows differential responses across treatments (33). Food Craving Inventory assesses cravings for specific foods (34). Power of Food Scale assesses psychological drive to consume (i.e., appetite for, not consumption of) palatable foods (35).

Randomization

Participants were randomized to receive, in double-blind fashion, either placebo or naltrexone/bupropion for 12 weeks. Randomization, stratified by obesity status (yes/no, based on BMI >30kg/m2) and gender, assigned participants to treatments in random blocks of two and four (to obviate secular trends and ensure approximately equal proportions). A biostatistician developed the randomization schedule, which was concealed and administered by the Yale Investigational Drug Service. Placebo was prepared in capsules and matched in frequency and appearance to naltrexone/bupropion by the Yale Investigational Drug Service.

Treatment

Medication (Naltrexone/Bupropion or Placebo).

Naltrexone/bupropion comprised naltrexone-sustained-release (32 mg/day) combined with bupropion-sustained-release (360 mg/day). Participants randomized to naltrexone/bupropion started with an initial dose of 8mg/90mg every morning with weekly dose-escalation over 4 weeks to final dose of 16mg/180mg twice daily (24,26). Placebo was given in two doses taken twice daily, matched in appearance and frequency. Dose down-titration was permitted for side-effects intolerability and for all participants at post-treatment. If patients experienced adverse events and/or could not tolerate the medication, they were withdrawn from medication.

A faculty-level study physician delivered the pharmacotherapy intervention, involving only medication management (compliance, safety, and side-effects) without additional psychotherapeutic interventions, which were proscribed. Medication adherence evaluation and side-effect checklists were performed monthly by a research-clinician. Monthly medication refills were accompanied by re-review of medication compliance and dosing schedules; pill bottles were returned for pill counts at post-treatment.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was based on power calculations using data from RCTs testing behavior therapy for BED (11,12), placebo for BED (14,15) and naltrexone/bupropion for weight-loss (25,26). Although some reported effects sizes were in the medium-to-large ranges, we conservatively powered this RCT to detect medium and clinically meaningful medication effects for primary outcomes. N=90, allocated equally to the treatment conditions, yielded >80% power for medium effect sizes (f=0.30) for main effects at a two-sided alpha threshold of 0.05.

Analyses to compare treatments were intention-to-treat, performed for all randomized patients who attended the first treatment session. Two co-primary outcome variables—binge eating and weight loss—were both analyzed using complementary measures. Binge eating was analyzed as frequency (continuous) and remission (categorical). “Remission” from binge eating was defined as zero episodes during previous 28 days (assessed with EDE) at post-treatment. Missing data were conservatively imputed as failure (non-remission). Weight loss was analyzed as percent change from baseline (continuous) and as attaining >5% weight loss (categorical). The >5% weight loss category is common in obesity (24) and BED (22,26) trials and is associated with health benefits (36). The >5% weight loss category was determined using change in measured weight from baseline; missing data were conservatively imputed as failure to attain 5% category.

Secondary outcomes were eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE Global), depression (BDI-II), eating behavior (TFEQ [Restraint, Disinhibition, and Hunger], FCI, PFS) scores, and cardiometabolic variables (lipid profile, Hb1Ac).

For continuous measures, intention-to-treat analyses used all available data in mixed models without imputation. Variables not conforming to normality were log-transformed. Mixed effects models were fitted with fixed factors including medication (naltrexone/bupropion vs. placebo), time (all relevant time points of baseline, week 2, month 1, month 2, post-treatment), and all possible interactions. In each model, the correlation in the data (i.e., repeatedly measured data within each subject) was modeled by considering different error structures and selecting the best-fitting structure (Schwarz Bayesian Criterion). Statistical testing was performed at 0.05 significance level. For categorical outcomes, logistic regression tested the outcomes at post-treatment. Since randomization was stratified by obesity status, a specified variable of interest as a potential moderator and predictor, analyses first tested whether medication effects were moderated by obesity status. Analyses revealed medication effects were not moderated by obesity status (i.e., interactions with medication were not significant) for any outcomes. Supplemental Table 1 shows primary and secondary clinical measures/outcomes by obesity status across treatments. Accordingly, primary analyses controlled for obesity status (yes/no) by including it as an independent predictor in models evaluating effects of medication (NB versus placebo). Sensitivity analyses restricted to subgroups categorized with and without obesity were performed to explore whether substantively different patterns occurred.

RESULTS

Randomization and Participant Characteristics

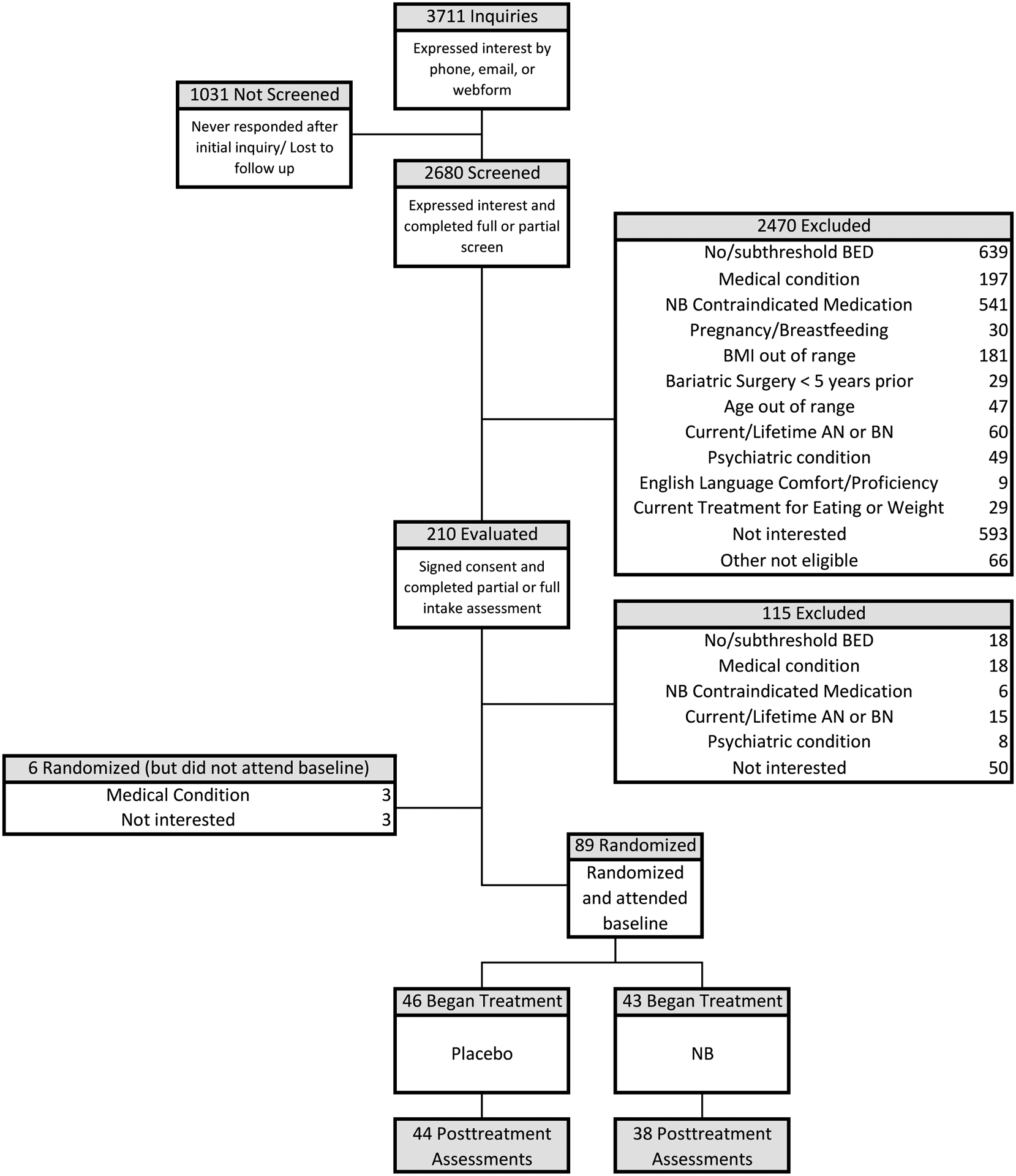

Figure 1 (CONSORT) summarizes participant flow. Of 2680 respondents screened, 210 consented and were evaluated for eligibility, and 89 were randomized and attended baseline. Of the 89 participants, N=46 received placebo and N=43 received naltrexone/bupropion. Post-treatment assessments were obtained for 91.2% (82/89) of participants. Table 1 describes participants’ sociodemographic characteristics.

Figure 1. Participant flow throughout the study.

AN = anorexia nervosa; BN = bulimia nervosa; BED = bingeeating disorder; NB=naltrexone/bupropion; BMI = body mass index.

*Psychiatric condition: participants reporting serious mental illness such as psychosis, bipolar disorder, and current substance use disorder were excluded.

Of the 89 participants, 69 were categorized with obesity and 20 were categorized without obesity. Of the 69 participants with obesity, 36 received placebo and 33 received NB, and of the 20 participants categorized without obesity, 10 received placebo and 10 received NB.

TABLE 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics overall and across treatment conditions.

| Overall | Placebo | NB | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=89 | n=46 | n=43 | |||||||

| Age, N, M (SD) | 89 | 45.67 | 13.50 | 46 | 46.02 | 13.16 | 43 | 45.30 | 14.01 |

| Sex, n, % | |||||||||

| Male | 24 | 27% | 13 | 28.3% | 11 | 25.6% | |||

| Female | 63 | 70.8% | 33 | 71.7% | 30 | 69.8% | |||

| Transgender | 2 | 2.2% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 4.7% | |||

| Race, n, % | |||||||||

| White | 62 | 69.7% | 31 | 67.4% | 31 | 72.1% | |||

| Asian | 3 | 3.4% | 2 | 4.3% | 1 | 2.3% | |||

| Black | 17 | 19.1% | 10 | 21.7% | 7 | 16.3% | |||

| Multiracial | 5 | 5.6% | 3 | 6.5% | 2 | 4.7% | |||

| Other | 2 | 2.2% | 0 | 0% | 2 | 4.7% | |||

| Ethnicity, n, % | |||||||||

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 83 | 93.3% | 43 | 93.5% | 40 | 93% | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 6 | 6.7% | 3 | 6.5% | 3 | 7% | |||

| Sexual Orientation, n, % | |||||||||

| Heterosexual | 80 | 89.9% | 42 | 91.3% | 38 | 88.4% | |||

| Gay or Lesbian | 3 | 3.4% | 1 | 2.2% | 2 | 4.7% | |||

| Bisexual | 6 | 6.7% | 3 | 6.5% | 3 | 7% | |||

| Education, n, % | |||||||||

| High School | 16 | 18% | 8 | 17.4% | 8 | 18.6% | |||

| Some college | 34 | 38.2% | 20 | 43.5% | 14 | 32.6% | |||

| College | 16 | 18% | 4 | 8.7% | 12 | 27.9% | |||

| Post college | 23 | 25.8% | 14 | 30.4% | 9 | 20.9% | |||

Note: M = mean. SD = standard deviation. N = number. BED = binge-eating disorder.

NB = naltrexone/bupropion. Overall, 20 of the 89 participants were categorized with obesity; of the 69 participants with obesity, 36 received placebo and 33 received NB, and of the 20 participants categorized without obesity, 10 received placebo and 10 received NB.

Primary Outcomes

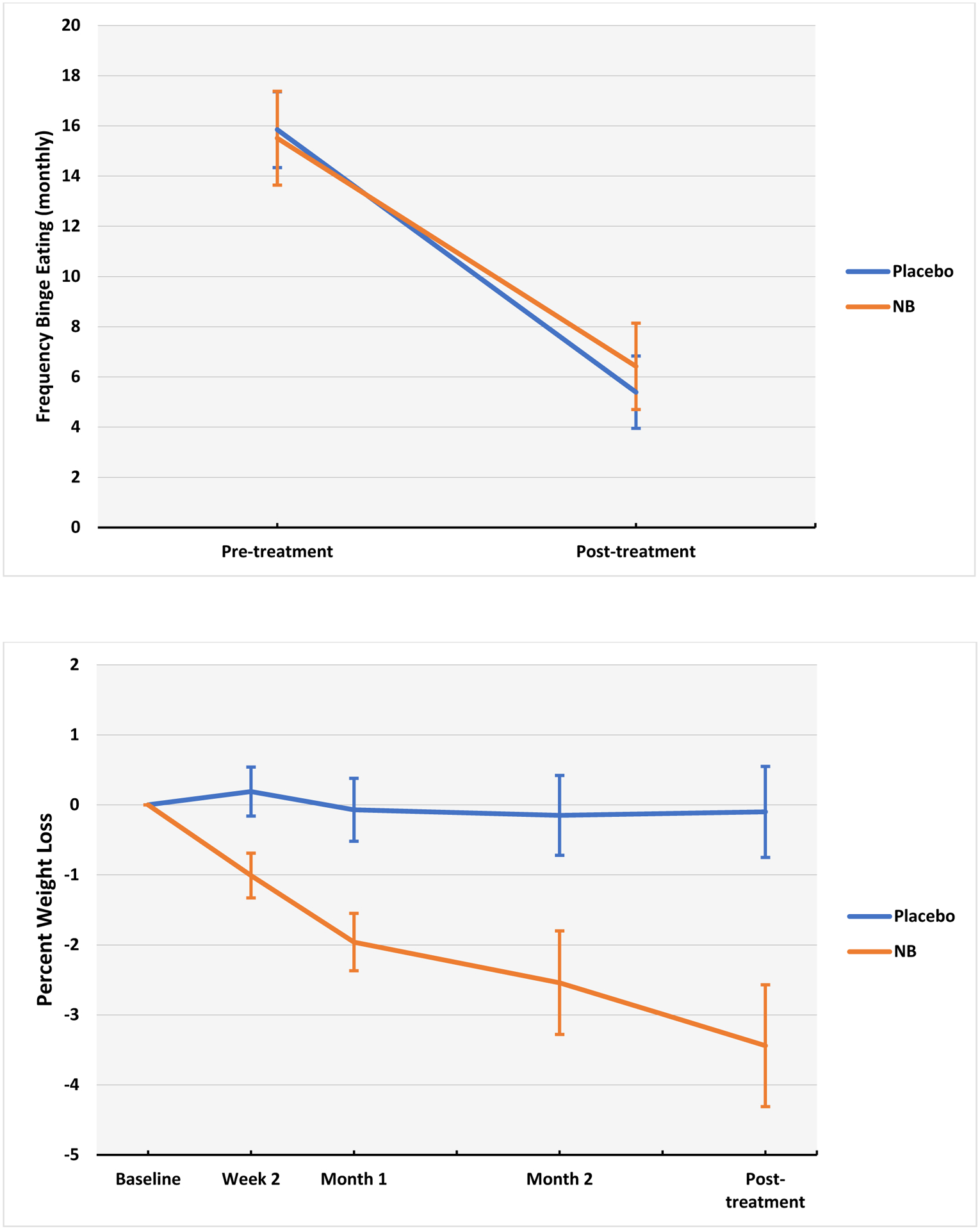

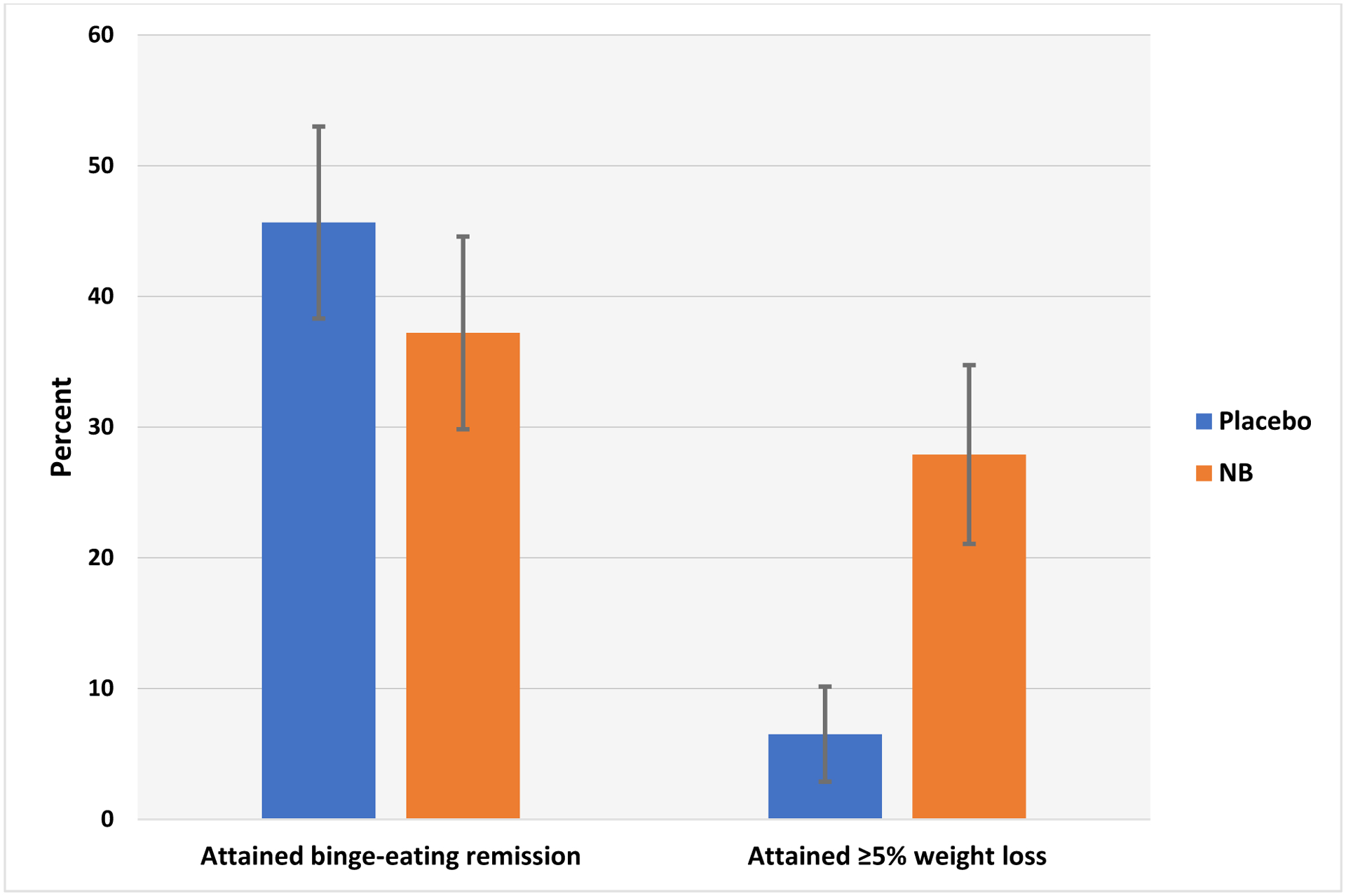

Table 2 summarizes descriptive analyses for the co-primary outcomes (binge-eating and weight-loss; BMI values are presented for descriptive context). Table 3 summarizes test statistics and p-values for all main and interaction effects for the primary outcomes. Figures 2–3 summarize analyses for continuous and categorical variables, respectively.

Table 2.

Primary clinical measures and outcomes by treatment conditions.

| Placebo (n=46) | NB (n=43) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| EDE Binge Eating | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 15.85 | 10.26 | 43 | 15.51 | 12.25 |

| Post-Treatment | 44 | 5.39 | 9.56 | 38 | 6.42 | 10.61 |

| Change | 44 | −10.86 | 10.91 | 38 | −9.58 | 11.99 |

| Weight (kg) | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 98.00 | 19.24 | 43 | 103.03 | 24.63 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 96.57 | 19.03 | 36 | 99.75 | 24.25 |

| Change | 43 | −0.23 | 4.02 | 36 | −3.61 | 5.12 |

| % Change | 43 | −0.10 | 4.24 | 36 | −3.44 | 5.24 |

| Weight (pounds) | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 216.06 | 42.42 | 43 | 227.14 | 54.31 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 212.89 | 41.96 | 36 | 219.91 | 53.46 |

| Change | 43 | −0.50 | 8.86 | 36 | −7.97 | 11.28 |

| % Change | 43 | −0.10 | 4.24 | 36 | −3.44 | 5.24 |

| BMI | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 34.71 | 5.99 | 43 | 35.90 | 6.25 |

| Post-treatment | 43 | 34.26 | 5.65 | 36 | 34.64 | 6.36 |

| Change | 43 | −0.10 | 1.49 | 36 | −1.19 | 1.82 |

Note: Binge eating (frequency during previous 28 days) and percent weight loss were the

pre-specified co-primary outcomes.

EDE = Eating Disorder Examination Interview; BMI = body mass index; NB = naltrexone/bupropion;

N = number; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

Table 3.

Analytic model findings for primary outcomes.

| Continuous outcomes | ||

|---|---|---|

| Model effect | Binge Eating Frequency (EDE Interview) | Percent Weight Loss |

| MED | F(1,86)=0.05, p=0.83 | F(1,84)=11.3, p=0.001 |

| Time | F(1,86)=131.5, p<0.0001 | F(3,229)=7.43, p<0.0001 |

| MED*Time | F(1,86)=0.59, p=0.44 | F(3,229)=3.26, p=0.02 |

| Obesity | F(1,86)=0.87, p=0.35 | F(1,84)=0.36, p=0.55 |

| Categorical outcomes | ||

| Model effect | Attaining Binge-Eating Remission at Posttreatment | Attaining ≥5% Weight Loss from Baseline |

| MED | Χ2(1)=0.63, p=0.43 | Χ2(1)=6.30, p=0.01 |

| Obesity | Χ2(1)=1.37, p=0.24 | Χ2(1)=3.06, p=0.08 |

Note: Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) Interview administered at pre-treatment and post-treatment;

Weight measured pre-treatment, monthly throughout treatment, and post-treatment;

MED = naltrexone/bupropion versus placebo; Obesity = obesity status (non-obese, obese);

Time = assessment timepoints; continuous outcomes analyzed using mixed models on

log-transformed data; binary outcomes analyzed using logistic regression.

Figure 2. Primary continuous outcomes (binge-eating frequency and % weight loss) across treatments.

Figure 2-A (top panel) caption.

Frequency of binge eating during the last 28 days assessed using the Eating Disorder Examination-Interview. N=89. Naltrexone/bupropion and placebo conditions did not differ significantly. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Figure 2-B (bottom panel) caption.

Percent weight loss (from baseline) calculated using measured values at baseline, measured monthly during treatment, and measured at post-treatment. N=89. Naltrexone/bupropion (NB) was associated with significantly greater percent weight loss than placebo (p values were significant at all time points, ranging from p=0.02 (week 2) to p=0.0007 (posttreatment)). Error bars indicate standard errors. NB = naltrexone/bupropion

Figure 3. Primary categorical outcomes (binge-eating remission and 5% weight loss) across treatments.

Left side shows binge-eating remission rates at posttreatment for naltrexone/bupropion (NB) and placebo treatment conditions. Remission rates are defined as zero episodes of binge eating during the last 28 days assessed using the Eating Disorder Examination-Interview. The rates are based on the intention-to-treat sample (N=89) with any missing data imputed as failure to remit. Naltrexone/bupropion and placebo conditions did not differ significantly. Error bars indicate standard errors.

Right side shows proportion of patients attaining 5% weight loss or greater (from baseline) calculated using measured values at post-treatment. The frequencies are based on the intention-to-treat sample (N=89) with any missing data imputed as failure to attain 5% weight loss. Naltrexone/bupropion (NB) was associated with significantly higher rates of attaining 5% weight loss than placebo (p=0.01). Error bars indicate standard errors.

Binge-eating Outcomes

Figure 2 shows binge-eating frequency (episodes/past month) at pre- and post-treatment. Mixed models of binge-eating frequency (Table 3) revealed significant main effect of time (F(1,86)=131.5, p<0.0001) but no significant interaction between medication and time (F(1,86)=0.59, p=0.44), and no significant main effects of medication (F(1,86)=0.05, p=0.83) or of obesity status (F(1,86)=0.87, p=0.35).

Figure 3 illustrates binge-eating remission rates at post-treatment across treatments. Logistic regression revealed remission rates did not differ significantly between placebo (45.7%; N=21/46) and naltrexone/bupropion (37.2%; N=16/43) nor did obesity status show a significant main effect (Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses restricted to those with (N=69) and without obesity (N=20) converged in terms of non-significant statistical findings and pattern of binge-eating outcomes (Supplemental Table 1).

Weight Loss Outcomes

Figure 2 summarizes percent weight loss throughout the course of treatments and Table 2 shows weight values at baseline and post-treatment, and changes. Mixed models of percent weight loss (Table 3) revealed a significant medication-by-time (F(3,229)=3.26, p=0.02), significant main effect of time (F(3,229)=7.43, p<0.0001), significant main effect of medication (F(1,84)=11.3, p=0.001), but not significant main effect of obesity status (F(1,84)=0.36, p=0.55). Medication-by-time interaction was explained by significant reductions in weight across time among participants receiving naltrexone/bupropion (F(3,229)=9.59, p<0.0001), compared to no significant change among those receiving placebo (F(3,229)=0.54, p=0.66).

Figure 3 illustrates rates of participants attaining >5% weight loss at post-treatment by treatment condition. Logistic regression revealed that naltrexone/bupropion had significantly higher rates (27.9%; N=12/43) than placebo (6.5%; N=3/46) but obesity status did not show a significant main effect (Table 3).

Sensitivity analyses restricted to those with obesity (N=69) revealed similar statistical findings as for the overall study group for both the percent weight loss and proportion attaining >5% weight loss. For the N=69 with obesity, logistic regression indicated naltrexone/bupropion had significantly higher rates (24.2%; N=8/33) than placebo (2.8%; N=1/36) (X2(1)=4.89, p=0.027; odds ratio=11.2; 95%CI=1.3 – 95.3). Sensitivity analyses for the group without obesity (N=20) revealed a similar pattern of weight outcomes (Supplemental Table 1) but did not approach significance due to limited sample size and power.

No instances of concerning weight losses were observed in those without obesity; no one dropped to our minimal BMI inclusionary criterion, lowest observed BMI at post-treatment was 21.9 (up from 21.7 at baseline), and mean BMI for this group dropped from 27.8 (SD=1.6) to 26.8 (SD=2.2).

Secondary Outcomes

Table 4 shows descriptive statistics for secondary outcomes of eating-disorder psychopathology, depression, eating behaviors, and cardiometabolic variables across treatments. Mixed models revealed no significant medication-by-time effects for any of these secondary variables. Significant time effects (reflecting improvements) were found for eating-disorder psychopathology (EDE global score; F(1,80)=57.4, p<0.0001), depression (BDI-II score; F(3,219)=32.66, p<0.001), and eating behaviors (TFEQ disinhibition [F(3,216)=26.48, p<0.001], TFEQ hunger [F(3,216)=16.93, p<0.001], FCI score [F(3,216)=31.63, p<0.001], and PFS score [F(3,216)=31.63, p<0.001]. No significant time effects for observed for the cardiometabolic variables.

Table 4.

Secondary clinical measures and outcomes by treatment conditions.

| Placebo (n=46) | NB (n=43) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | M | SD | n | M | SD | |

| EDE Global Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 2.28 | 0.92 | 43 | 2.25 | 0.69 |

| Post-Treatment | 44 | 1.72 | 0.88 | 38 | 1.59 | 0.78 |

| Change | 44 | −0.58 | 0.74 | 38 | −0.63 | 0.71 |

| BDI-II Depression Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 15.80 | 8.62 | 43 | 13.37 | 7.96 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 8.67 | 9.14 | 34 | 7.00 | 5.86 |

| Change | 43 | −7.21 | 10.03 | 33 | −6.85 | 8.97 |

| TFEQ Restraint Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 8.35 | 4.56 | 43 | 8.58 | 4.86 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 9.51 | 5.13 | 34 | 9.94 | 4.33 |

| Change | 43 | 1.21 | 4.68 | 33 | 1.58 | 4.43 |

| TFEQ Disinhibition Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 12.91 | 2.62 | 43 | 13.14 | 2.14 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 10.67 | 3.54 | 34 | 10.35 | 3.88 |

| Change | 43 | −2.12 | 3.03 | 33 | −2.82 | 2.97 |

| TFEQ Hunger Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 10.63 | 2.89 | 43 | 9.67 | 2.99 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 8.16 | 3.85 | 34 | 7.29 | 4.12 |

| Change | 43 | −2.65 | 3.37 | 33 | −2.58 | 3.50 |

| FCI Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 1.95 | 0.76 | 43 | 1.71 | 0.46 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 1.43 | 0.61 | 34 | 1.18 | 0.61 |

| Change | 43 | −0.56 | 0.68 | 33 | −0.53 | 0.49 |

| PFS Score | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 46 | 59.02 | 12.59 | 43 | 57.81 | 10.24 |

| Post-Treatment | 43 | 47.09 | 14.96 | 34 | 45.76 | 16.75 |

| Change | 43 | −12.19 | 13.18 | 33 | −11.91 | 12.36 |

| Cholesterol Total | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 44 | 192.34 | 39.53 | 43 | 183.88 | 35.51 |

| Post-Treatment | 39 | 193.28 | 41.34 | 32 | 180.16 | 34.62 |

| Change | 37 | −2.78 | 26.19 | 32 | −6.94 | 21.11 |

| HDL | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 44 | 55.27 | 15.18 | 43 | 53.37 | 13.92 |

| Post-Treatment | 39 | 55.79 | 16.55 | 32 | 54.41 | 13.90 |

| Change | 37 | −0.43 | 11.31 | 32 | 0.09 | 7.34 |

| LDL | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 44 | 114.89 | 28.35 | 43 | 108.12 | 27.33 |

| Post-Treatment | 38 | 115.87 | 33.74 | 32 | 105.50 | 27.25 |

| Change | 36 | −2.00 | 19.90 | 32 | −4.31 | 17.65 |

| Triglycerides | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 44 | 116.43 | 66.25 | 43 | 121.84 | 70.42 |

| Post-Treatment | 39 | 122.79 | 82.57 | 32 | 105.09 | 57.59 |

| Change | 37 | 2.86 | 74.04 | 32 | −20.97 | 46.86 |

| HbA1c | ||||||

| Pre-Treatment | 44 | 5.49 | 0.69 | 42 | 5.37 | 0.48 |

| Post-Treatment | 39 | 5.61 | 0.91 | 32 | 5.39 | 0.54 |

| Change | 37 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 31 | −0.02 | 0.18 |

Note: EDE = Eating Disorder Examination Interview; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; TFEQ =

Three Factor Eating Questionnaire; FCI = Food Craving Inventory; PFS = Power of Food Scale;

HbA1c = glycated hemoglobin A1c (%); NB = naltrexone/bupropion; N = number; M = mean; SD = standard deviation.

DISCUSSION

In this study of adults with BED with and without obesity, naltrexone/bupropion did not demonstrate effectiveness for reducing binge eating relative to placebo but showed effectiveness for weight reduction. Obesity status did not predict nor moderate any of the medication outcomes. Sensitivity analyses restricted to the subgroups with and without obesity found the same pattern of findings.

Although binge-eating frequency reduced significantly during this 12-week RCT (mean reduction of approximately 10 episodes/monthly), naltrexone-bupropion and placebo did not differ significantly. Binge-eating remission rates in this RCT also did not differ significantly between naltrexone/bupropion (37.2%) and placebo (45.7%). A previous RCT (26) found naltrexone/bupropion was superior to placebo in binge-eating remission rates but not binge-eating frequency at posttreatment. Remission rates observed in this RCT are substantially higher than those reported recently for naltrexone/bupropion (18.8%) and placebo (11.8%) in a RCT testing naltrexone/bupropion and behavior therapy for BED in patients with obesity (26). These discrepant findings are puzzling especially considering the striking similarities in the RCTs: both were performed during the same time period (2018–2021), at the same site, by the same investigative team, using the same evaluation methods, and the same treatments. We highlight that high placebo response rates have been reported in pharmacological RCTs for BED (e.g., 37,38); however, reviews of RCTs (8,16) have generally reported variability in placebo responses for BED that—while higher than for other eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa—generally approximate rates reported for other psychiatric disorders such as depression (39).

Naltrexone/bupropion demonstrated effectiveness relative to placebo for acute weight reduction. In this 12-week RCT, naltrexone/bupropion was associated with significantly greater weight loss than placebo (mean of approximately 3.4% weight loss versus 0.1%, respectively) and with significantly greater proportion of attaining >5% weight loss (27.9% vs 6.5%, respectively). A previous RCT testing naltrexone/bupropion—which observed roughly comparable percent weight loss findings and proportions attaining >5% weight loss (18.8% for naltrexone/bupropion versus 11.8% for placebo)—found that naltrexone/bupropion was not statistically superior to placebo. The weight losses observed in the present and previous (26) RCTs are more modest than the roughly 6.1% reported in the longer 24-week RCTs testing naltrexone/bupropion for obesity in patients without BED (24). Since this trial’s duration was half the duration of the previous obesity trials (24), the weight loss of ~3.4%, which is approximately half of 6.1% makes sense; visual inspection of the weight loss curve in Figure 1 suggests that the participants had not yet attained weight nadir or plateau.

Studies are needed to assess longer-term weight trajectories and outcomes in patients with BED treated with medications as the current literature comprises mostly brief acute trials (16). Newly approved medications for chronic weight management, such as semaglutide—which has resulted in larger weight losses than previous weight-loss medications alongside significant improvements in cardiometabolic variables (40)—should also be evaluated for BED. This is an important avenue for research given the strong association between BED and obesity and the well-established challenge in achieving weight loss in this specific patient group (8). While a previous RCT reported no significant interaction effects for combining naltrexone/bupropion with behavioral therapy (26), a synergistic effect might occur when combined with evidence-based psychological interventions with different therapeutic mechanisms such as cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy which reduce binge eating but not weight (9,11,20,41). Future research should examine clinical and metabolic predictors and moderators of response to naltrexone/bupropion (and to other active medications), and of psychological versus pharmacological approaches, which may ultimately guide rational matching of patients to specific treatments and inform models of the mechanisms of change (7).

At a broader level, these findings regarding the effectiveness of naltrexone/bupropion for weight loss in patients with BED are also relevant in light of criticisms voiced by some groups that addressing excess weight in people with BED is contraindicated because of potential to cause harm, such as triggering eating disorders. Cardel and colleagues (13,42), in their evidence-based commentaries, cogently addressed the “false dichotomy” between reducing eating-disorder risk and treating obesity. In contrast to concerns that addressing obesity might serve only to stigmatize people with higher BMIs and to foster eating disorders, systematic reviews of the evidence base indicate that reductions in eating-disorder psychopathology occur during and following behavioral weight management interventions with few instances of eating-disorder symptoms developing (43). The present study testing naltrexone/bupropion and the recent RCT testing naltrexone/bupropion and behavioral therapy for BED (26) converge with previous rigorous trials testing behavioral weight loss for BED (11,41,44) in documenting reductions in binge eating and associated eating-disorder psychopathology.

This study’s findings should be considered within the context of methodological strengths and limitations. Study strengths include double-blinded pharmacotherapy delivered by an expert physician, independent assessments performed reliably by doctoral research-clinicians using well-validated measures, minimal exclusionary criteria to enhance generalizability, and excellent (i.e., 91.2%) retention rates. This RCT was one of the very few to enroll patients with BED without obesity and the first to be able formally to explore obesity status as a predictor and moderator of pharmacological outcomes.

Several study limitations are noteworthy. The findings may not generalize to people with BED who seek treatment in different clinical settings (than an academic medical school research program setting) or for different medical or psychiatric priorities, or to people with different sociodemographic/clinical characteristics. Alternatively, we employed relatively few exclusionary criteria to broaden generalizability and our study compared naltrexone/bupropion to placebo with minimal clinical management without any additional psychotherapeutic or nutritional interventions which reflect “clinical reality” in many busy clinical settings. The study group was 71% female, 70% White [19% Black], 90% heterosexual, and 82% with at least some college-level education. Thus, while relatively diverse compared to the treatment literature for BED (45), the diversity was limited overall and precluded analysis of specific needs and outcomes of different minority groups. The sample size had limited power to detect smaller magnitude effects of medication and of main and interaction effects of obesity status on the outcomes. Finally, the findings pertain only for acute outcomes following brief 12-week treatments (i.e., reflective of the modal length of pharmacological literature for BED, which is roughly half the length of the obesity RCT literature) and longer-term and maintenance studies (27) are needed to address questions regarding relapse.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance Questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Few evidence-based treatments exist for binge-eating disorder, particularly pharmacological options.

Most evidence-based treatments for binge-eating disorder do not produce weight loss among individuals with co-existing obesity.

What are the new findings in your manuscript?

Naltrexone/bupropion did not demonstrate effectiveness for reducing binge eating but showed effectiveness for weight reduction in patients with binge-eating disorder.

Obesity status did not predict nor moderate medication outcomes in patients with binge-eating disorder.

How might your results change the direction of research or the focus of clinical practice?

Future research should test effective anti-obesity medications combined with cognitive-behavioral therapy, which reduces binge eating but not weight.

Future research should investigate predictors/moderators of responses to pharmacological versus psychological approaches to guide rational matching of patients with binge-eating disorder to specific treatments.

Funding:

National Institutes of Health grant R01 DK112771 (Grilo and McKee), K23 DK115893 (Lydecker) and UL1 TR001863. The funding agency (National Institutes of Health and the Public Health Service) played no role in the content of this paper.

Footnotes

Clinicaltrials.gov registration: NCT03539900

Potential Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest relative to this study. Dr. Grilo reports broader interests, which did not influence this research, including Honoraria for lectures, and Royalties from Guilford Press and Taylor & Francis Publishers for academic books. Dr. Jastreboff reports broader interests, which did not influence this study, including serving on Scientific Advisory Boards for to Amgen, AstraZeneca, BioHaven Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Intellihealth, Novo Nordisk, , Pfizer, Rhythm Pharmaceuticals, Scholar Rock, Structure Therapeutics, Terns Pharmaceuticals, Weight Watchers International, and Zealand Pharma A/S.

Data Sharing:

De-identified data will be provided in response to reasonable written request to achieve goals in an approved written proposal (from non-commercial academic researchers).

REFERENCES

- 1.American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Chiu WT, et al. : The prevalence and correlates of binge eating disorder in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Biol Psychiatry 2013;73:904–914 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udo T, Grilo CM: Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5-defined eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Biol Psychiatry 2018;84:345–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Streatfeild J, Hickson J, Austin SB, et al. : Social and economic cost of eating disorders in the United States: evidence to inform policy. Int J Eat Disord 2021;54:851–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Udo T, Grilo CM: Psychiatric and medical correlates of DSM-5 eating disorders in a nationally representative sample of adults in the United States. Int J Eat Disord 2019;52:42–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudson JI, Lalondie JK, Coit CE, et al. : Longitudinal study of the diagnosis of components of the metabolic syndrome in individuals with binge-eating disorder. Am J Clin Nutr 2010:91:1568–1573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boswell RG, Potenza MN, Grilo CM: The neurobiology of binge-eating disorder compared with obesity: implications for differential therapeutics. Clin Ther. 2021;43:50–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilbert A, Petroff D, Herpertz S, et al. : Meta-analysis of the efficacy of psychological and medical treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019;87:91–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grilo CM. Psychological treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2017; 78:20–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coffino JA, Udo T, Grilo CM: Rates of help-seeking in U.S. adults with lifetime DSM-5 eating disorders: Prevalence across diagnoses and sex and ethnic/racial differences. Mayo Clin Proc 2019;94:1415–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson GT, Wilfley DE, Agras WS, et al. : Psychological treatments of binge eating disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:94–101 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reas DL, Masheb RM, Grilo CM: Appearance vs. health reasons for seeking treatment among obese patients with binge eating disorder. Obes Res 2004;12:758–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cardel MI, Newsome FA, Pearl RL, Ross KM, Dillard JR, Miller DR, et al. Patient centered care for obesity: how health care providers can treat obesity while actively addressing weight stigma and eating disorder risk. J Acad Nutr Diet 2022;122:1089–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McElroy SL, Hudson JI, Mitchell JE, et al. : Efficacy and safety of lisdexamfetamine dimesylate for treatment of adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:235–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McElroy SL, Hudson J, Ferreira-Cornwell M, et al. : Lisdexamfetamine dimesylate for adults with moderate to severe binge-eating disorder: Results of two pivotal phase 3 randomized controlled trials. Neuropsychopharm 2016;41:1251–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McElroy SL: Pharmacologic treatments for binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2017;78S1:14–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McElroy SL, Arnold LM, Shapira NA, et al. : Topiramate in the treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2007;160:255–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Claudino AM, de Oliveira IR, Appolinario JC, et al. : Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of topiramate plus cognitive-behavior therapy in binge-eating disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:1324–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McElroy SL, Shapira NA, Arnold LM, Keck PE, Rosenthal NR, Wu SC, et al. Topiramate in the long-term treatment of binge eating disorder associated with obesity. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:1463–1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT: Efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy and fluoxetine for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled comparison. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:301–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ricca V, Mannucci E, Mezzani B, Moretti S, Di Bernardo M, Bertelli M, et al. Fluoxetine and fluvoxamine combined with individual cognitive-behavioral therapy in binge eating disorder: a one-year follow-up study. Psychother Psychosom. 2001;70:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Salant SL: Cognitive behavioral therapy guided self-help and orlistat for the treatment of binge eating disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1193–1201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA: Naltrexone extended-release plus bupropion extended-release for treatment of obesity. JAMA, 2015;313:1213–1214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. : Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multi-centre randomized double-blind placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2010;376:595–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grilo CM, Lydecker JA, Morgan PT, et al. : Naltrexone + bupropion combination for the treatment of binge-eating disorder with obesity: a randomized controlled pilot study. Clin Ther 2021;43:112–122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grilo CM, Lydecker JA, Fineberg SK, et al. : Naltrexone plus bupropion combination medication and behavior therapy, alone and combined, for binge-eating disorder: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry 2022;179:927–937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grilo CM, Lydecker JA, Gueorguieva R: Naltrexone plus bupropion combination medication maintenance treatment for binge-eating disorder following successful acute treatments: randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Psychol Med 2023:1–10 (early online) 10.1017/S0033291723001800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Billes SK, Greenway FL: Combination therapy with naltrexone and bupropion for besity. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2011;12:1813–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cowley MA, Smart JL, Rubinstein M, et al. : Leptin activates anorexigenic POMC neurons through neural network in the arcuate nucleus. Nature 2001;411(6836):480–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, O’Connor M: Eating Disorder Examination (16.0D). In Fairburn CG. Cognitive Behavior Therapy and Eating Disorders. NY: Guilford Press, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Lozano-Blanco C, et al. : Reliability of the Eating Disorder Examination in patients with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2004;35:80–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Steer R, Garbin M: Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: 25 years of evaluation. Clin Psychol Rev 1998;8:77–100 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stunkard AJ, Messick S: The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition, and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985;29:71–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White MA, Grilo CM: Psychometric properties of the Food Craving Inventory among obese patients with binge eating disorder. Eat Behav 2005;6:239–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cappelleri JC, Bushmakin AG, Gerber RA, et al. : Evaluating the Power of Food Scale in obese subjects and a general sample of individuals: development and measurement properties. Int J Obesity 2009;33:913–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wing RR, Lang W, Wadden TA, et al. : Benefits of modest weight loss in improving cardiovascular risk factors in overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1481–1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stunkard AJ, Berkowitz R, Tanrikut C, Reiss E, Young L. d-fenfluramine treatment of binge eating disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:1455–1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jacobs-Pilipski MJ, Wilfley DE, Crow SJ, et al. Placebo response in binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord 2007;40:204–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Walsh BT, Seidman SN, Sysko R, Gould M. Placebo response in studies of major depression. JAMA 2002;287:1840–1847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wadden TA, Bailey TS, Billings LK, et al. Effect of subcutaneous semaglutide vs placebo as an adjunct to intensive behavioral therapy on body weight in adults with overweight or obesity: The STEP 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2021;325:1403–1413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grilo CM, Masheb RM, Wilson GT, et al. : Cognitive-behavioral therapy, behavioral weight loss, and sequential treatment for obese patients with binge-eating disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Consult Clin Psychol 2011;79:675–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cardel MI, Newsome FA, Pearl RL, Ross KM, Dillard JR, Hayes JF, Wilfley D, Kell PK, Dhurandhar EJ, Balantekin KN. Authors’ response. J Acad Nutr Diet 2023;123:400–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jebeile H, Libesman S, Melville H, Low-wah T, Dammery G, Seidler A., et al. Eating disorder risk during behavioral weight management in adults with overweight or obesity: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Obesity Rev. 2023;e13561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grilo CM, White MA, Masheb RM, et al. : Randomized controlled trial testing the effectiveness of adaptive “SMART” stepped-care treatment for adults with binge-eating disorder comorbid with obesity. Am Psychologist 2020;75:204–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lydecker JA, Gueorguieva R, Masheb RM, White MA, Grilo CM. Examining race as a predictor and moderator of treatment outcomes for binge-eating disorder: analysis of aggregated randomized controlled trials. J Consult Clin Psychol 2019;87:530–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

De-identified data will be provided in response to reasonable written request to achieve goals in an approved written proposal (from non-commercial academic researchers).