Abstract

BACKGROUND

The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor talazoparib demonstrated antitumor activity in patients with advanced breast cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation (gBRCAm).

METHODS

We conducted an open-label phase 3 trial in patients with advanced gBRCAm breast cancer, randomized 2:1 to receive talazoparib (1 mg once daily) or physician’s choice of therapy (capecitabine, eribulin, gemcitabine, or vinorelbine). The primary endpoint was progression-free survival assessed by blinded independent central review.

RESULTS

Of 431 patients randomized, 287 were assigned to receive talazoparib and 144 to physician’s choice. Median (95% CI) progression-free survival was significantly prolonged for talazoparib compared with physician’s choice (hazard ratio = 0.54, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.71; P<0.0001; 8.6 months vs. 5.6 months). Interim median overall survival had a hazard ratio of 0.76, 95% CI: 0.55, 1.06; P=0.105 (51% of projected events). Objective response rate in patients receiving talazoparib improved compared with physician’s choice (talazoparib, 62.6%; PCT, 27.2%; odds ratio = 4.99, 95% CI: 2.93, 8.83; P<0.0001). Hematologic grade 3–4 adverse events, primarily anemia, occurred in 55% and 39% of patients on talazoparib and physician’s choice, respectively; nonhematologic grade 3–4 adverse events occurred in 32% and 38% of patients, respectively. Patient-reported outcomes favored talazoparib; significant overall improvements and significant delays in time to clinically meaningful deterioration in both global health status/quality of life and breast symptoms were observed.

CONCLUSIONS

In patients with advanced gBRCAm breast cancer, single-agent talazoparib demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in progression-free survival versus physician’s choice chemotherapy. Patient reported outcomes were superior with talazoparib. (Funded by Pfizer; EMBRACA ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT01945775).

INTRODUCTION

Cancer cells with deleterious mutations in breast cancer susceptibility genes 1 or 2 (BRCA1/2) are deficient in the DNA double-strand break repair mechanism, leaving these tumors highly dependent on the single-strand break repair pathway, regulated by the enzyme poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP).1–3 In cells with a BRCA1/2 mutation (BRCAmut), inhibition of PARP causes cell death due to accumulation of irreparable DNA damage.1–3 In addition to catalytic inhibition, PARP inhibitors induce PARP trapping at sites of DNA damage. The capacity to trap PARP-DNA complexes varies between PARP inhibitors and is not correlated with PARP catalytic inhibition.4–7 Preclinical models have indicated that trapping PARP on DNA may be more effective at inducing cancer cell death than enzymatic inhibition alone.4–7 Preclinically, talazoparib has been shown to be a very potent PARP inhibitor, with both strong catalytic inhibition (half maximal inhibitory concentration, 4 nM) and a PARP-trapping potential approximately 100-fold greater than that of other PARP inhibitors currently under investigation.5

In a phase 1 study (NCT01286987), talazoparib monotherapy (1 mg once daily) resulted in a 50% response rate and an 86% clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks in 18 patients with germline BRCA1/2 mutation (gBRCAm)-associated advanced breast cancer.8 The most common talazoparib-related adverse events were anemia, thrombocytopenia, and mild-to-moderate fatigue.8

In the ABRAZO phase 2 study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02034916), talazoparib also showed single-agent activity in 2 cohorts of patients with metastatic breast cancer and a gBRCAm: response rate was 21% in patients who had previously responded to platinum chemotherapy and 37% in patients who had received 3 or more prior cytotoxic regimens for advanced breast cancer without prior platinum exposure.9

This phase 3 trial (EMBRACA) compared the efficacy and safety of talazoparib with chemotherapy of physician’s choice for the treatment of locally advanced or metastatic breast cancer in patients with a gBRCAm.

METHODS

Patients

Eligible patients were aged 18 years or older with locally advanced (not amenable to curative therapy) or metastatic breast cancer and a deleterious or suspected deleterious gBRCAm by central testing (BRACAnalysis; Myriad Genetics, Salt Lake City, UT). Patients could have had no more than 3 prior cytotoxic regimens for advanced breast cancer; prior treatment with a taxane and/or anthracycline in any setting was required, unless contraindicated. Prior neoadjuvant or adjuvant platinum-based therapy was permitted provided the patient had a disease-free interval of at least 6 months following the last dose; patients were excluded if they had objective disease progression while receiving platinum chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer (i.e., the patient could not have had progressive disease by RECIST v1.1 within approximately 8 weeks following last dose).

There was no limit on the number of prior hormone therapies for patients with hormone-positive breast cancer. Patients with central nervous system (CNS) metastases were eligible provided they had completed definitive local therapy, had stable CNS lesions on repeat brain imaging, and were receiving low-dose or no glucocorticoids.

Additional eligibility criteria are provided in the supplement. The study protocol was approved by an independent ethics committee at each site before study initiation, and all enrolled patients provided written informed consent.

Study Design

The EMBRACA study was an open-label, randomized, international phase 3 trial comparing the efficacy and safety of talazoparib to protocol-specified physician’s choice of single agent therapy (capecitabine, eribulin, gemcitabine, or vinorelbine) using a 2:1 randomization in patients with advanced breast cancer (Supplemental Figure S1). Patients were centrally randomized with stratification by number of prior cytotoxic chemotherapy regimens for advanced disease (0 vs. 1 to 3), receptor status (triple-negative vs. hormone receptor–positive), and a history of CNS metastases (yes vs. no). Patients with human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer were not eligible for this trial.

The treatment arm consisted of talazoparib 1 mg orally once daily continuously in the fed or fasting state. Laboratory studies were monitored every 3 weeks with dose hold and dose reductions as outlined in the supplement.

The control arm was protocol-specified chemotherapy (capecitabine, eribulin, gemcitabine, or vinorelbine) in accordance with the institution’s dose and regimen guidelines in 21-day cycles. The choice of drug was determined before randomization for each patient.

Treatment continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, consent withdrawal, or physician decision. Cross-over from the control arm to the experimental arm was not permitted.

The study sponsor designed the protocol in collaboration with the authors. Local site investigators collected the data, which were analyzed by the sponsor. All authors had full access to study data after the primary analysis was conducted. The authors vouch for the accuracy and completeness of the data and for adherence of trial conduct to the study protocol (available at NEJM.org).

Editorial and medical writing support funded by Pfizer Inc. were provided by Edwin Thrower, PhD, Mary Kacillas, and Paula Stuckart of Ashfield Healthcare Communications.

Endpoints and Study Assessments

The primary endpoint was radiographic progression-free survival as determined by blinded independent central review using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors (RECIST) version 1.1. Progression-free survival was defined as time from randomization to the date of first documented radiographic progression per RECIST criteria or the date of death from any cause, whichever occurred first. Patients underwent imaging (computerized tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and nuclear medicine bone scans) at baseline, every 6 weeks until week 30, and then every 9 weeks; with head imaging repeated on-study as clinically indicated and bone scans every 12 weeks. All tumor imaging was centrally reviewed by 2 radiologists, with an adjudication assessment in case of disagreement for progression, per central imaging charter.

Secondary efficacy endpoints included overall survival, objective response rate, clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks (defined as the complete response/partial response/stable disease rate at 24 weeks or more), and duration of response. Following withdrawal from study treatment, patients were followed for survival and poststudy anticancer therapy every 12 weeks.

Safety was assessed by adverse events, concomitant medications, and clinically relevant changes in laboratory values. Adverse events were graded by National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v 4.03.

Patient-reported quality of life (QoL) was measured using the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire QLQ-C30 and the BR23 breast cancer module at baseline, the beginning of each treatment cycle, and end of treatment as supportive secondary endpoints (additional details are provided in the Statistical Analysis Plan v4, pages 29–32). The EORTC QLQ-C30 is a 30-item questionnaire composed of five multi-item functional subscales, three multi-item symptom scales, a global health status (GHS)/QoL subscale, and six single-item symptom scales assessing other cancer-related symptoms. The questionnaire includes 4-point Likert scales with responses from “not at all” to “very much” to assess functioning and symptoms and two 7-point Likert scales for GHS/QoL. The EORTC QLQ-BR23 is a 23-item breast cancer–specific companion module to the EORTC QLQ-C30 that consists of four functional scales and four symptom scales. Responses to all items are converted to a 0 to 100 scale using a standard scoring algorithm. For functional and GHS/QoL scales, higher scores represent a better level of functioning and QoL. For symptom scales, a higher score represents higher symptom severity. Hence, a negative change from baseline in symptom scales reflects an improvement, and a positive change reflects a deterioration. Conversely, a negative change from baseline in functional and GHS/QoL scales reflects a deterioration, and a positive change reflects an improvement. Blood and tumor samples were collected at baseline, and blood samples collected upon progression, in order to identify additional biologic markers that might indicate potential sensitivity or resistance to talazoparib.

Statistical Analyses

We determined that a total of 288 progression events or deaths following enrollment of 429 patients would provide a power of 90% (at a 2-sided alpha level of 0.05) to show a statistically significant difference in progression-free survival between the talazoparib group and the chemotherapy group, with a targeted hazard ratio of 0.67. To maintain the overall 2-sided type I error rate at 0.05, the analyses for the primary endpoint (progression-free survival) and key secondary endpoint (overall survival) were protected under a multiplicity adjustment schema using gate-keeping methodology. Additional details of the multiplicity adjustment methodology are described in the Statistical Analysis Plan v4 (pages 17–18; available at NEJM.org). Efficacy analyses were performed using the intent-to-treat population. Progression-free survival was analyzed using a stratified log-rank test (using stratification factors as randomized), summarized with the use of Kaplan-Meier methods. We estimated stratified hazard ratios (HRs) with 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) using a stratified Cox proportional hazard model, with stratification factors as randomized. Subgroup analyses were performed and are detailed in the supplementary appendix.10,11 Prespecified patient-reported outcome analyses included: 1) Overall mean change from baseline (estimated using the longitudinal mixed effects model); and 2) Time to clinically meaningful deterioration (analyzed using a stratified log-rank test, summarized using Kaplan-Meier methods). Clinically meaningful deterioration in Global Health Status/QoL was defined as the time from randomization to the first observation with a ≥10-point decrease and no subsequent observations with a <10-point decrease from baseline; deterioration in breast symptoms scale was defined as the time from randomization to the first observation with a ≥10-point increase and no subsequent observations with a <10-point increase from baseline.12

RESULTS

Patients

Patients were randomized at 145 sites in 16 countries from October, 2013, to April, 2017. A total of 431 patients were included in the intent-to-treat population. Of these, 287 were assigned to receive talazoparib and 144 to receive chemotherapy (capecitabine [44%]; eribulin [40%]; gemcitabine [10%]; vinorelbine [7%]); eighteen patients randomized to chemotherapy withdrew consent without being treated versus one patient in the talazoparib arm (Supplemental Figure S2). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics (ITT Population).

| TALA (N = 287) | Overall PCT (N = 144) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, median (range), y | 45 (27.0–84.0) | 50 (24.0–88.0) |

| <50 y, No. % | 182 (63.4) | 67 (46.5) |

| Female, % | 98.6 | 97.9 |

| ECOG PS 0 / 1 / 2, % | 53.3 / 44.3 / 2.1 | 58.3 / 39.6 / 1.4 |

| Stage of breast cancer | ||

| Locally advanced, No. % | 15 (5.2) | 9 (6.3) |

| Metastatic, No. % | 271 (94.4) | 135 (93.8) |

| Measurable disease by investigator, No. (%) | 219 (76.3) | 114 (79.2) |

| History of CNS metastases, No. (%) | 43 (15.0) | 20 (13.9) |

| Visceral disease, No. (%) | 200 (69.7) | 103 (71.5) |

| Hormone receptor status, No. (%) | ||

| TNBC | 130 (45.3) | 60 (41.7) |

| HR+ | 157 (54.7) | 84 (58.3) |

| BRCA status, No. (%)a | ||

| BRCA1+ | 133 (46.3) | 63 (43.8) |

| BRCA2+ | 154 (53.7) | 81 (56.3) |

| Disease-free interval (initial diagnosis to aBC) <12 months, No. (%) | 108 (37.6) | 42 (29.2) |

| Prior adjuvant/neoadjuvant therapy, No. (%) | 238 (82.9) | 121 (84.0) |

| No. of prior hormonal therapy-based regimens (for patients with HR+ BC), median (range) | 2.0 (0–6) (n = 157) |

2.0 (0–6) (n = 84) |

| Prior platinum therapy, No. (%) | 46 (16.0) | 30 (20.8) |

| Prior cytotoxic regimens for aBC, No. (%) | ||

| 0 | 111 (38.7) | 54 (37.5) |

| 1 | 107 (37.3) | 54 (37.5) |

| 2 | 57 (19.9) | 28 (19.4) |

| ≥3 | 12 (4.2) | 8 (5.6) |

Abbreviations: aBC = advanced breast cancer; BRCA = breast cancer susceptibility gene; CNS = central nervous system; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; ITT = intent-to-treat; HR = hormone receptor; PCT = physician’s choice of therapy; TALA = talazoparib; TNBC = triple-negative breast cancer.

Only 10 patients (6 and 4 patients in the talazoparib and control arms, respectively) were identified as having a suspected deleterious mutation. The remainder who underwent MYRIAD assessment carried a known pathogenic variation.

Efficacy

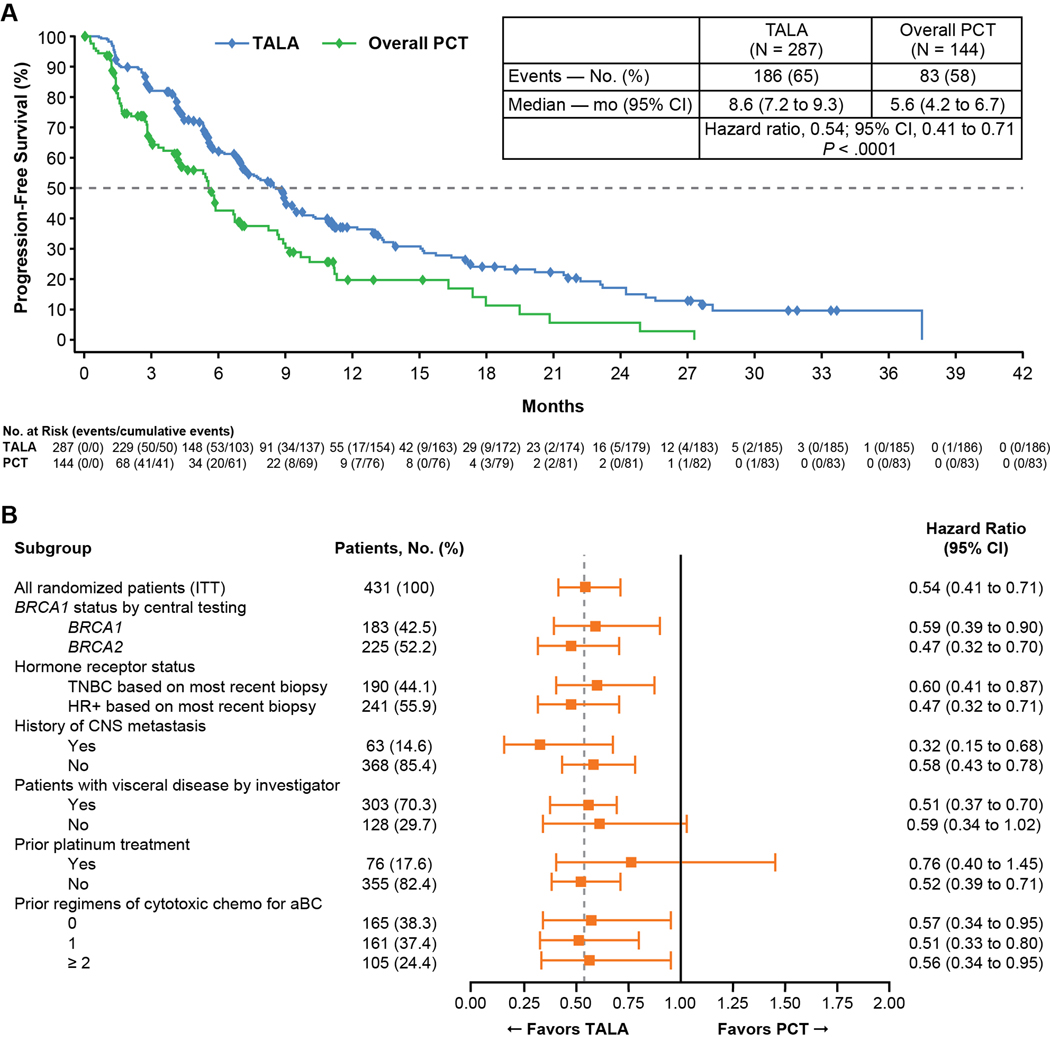

Median duration of follow-up for progression-free survival was 11.2 months by reverse Kaplan-Meier estimate. The primary endpoint (radiographic progression-free survival) was assessed after 269 blinded independent central review-confirmed progression events or deaths. Patients randomized to talazoparib versus chemotherapy had a median (95% CI) progression-free survival of 8.6 (7.2, 9.3) months versus 5.6 (4.2, 6.7) months (Figure 1A); the HR was 0.54 (95% CI: 0.41, 0.71, P<0.0001). The percentage of patients without progression by independent review or death at 1 year was 37% versus 20% for the talazoparib and chemotherapy groups, respectively. The HR for progression-free survival based on investigator assessment was identical to independent review (0.54 [95% CI: 0.42, 0.69]). Subgroup analysis of the talazoparib arm versus the chemotherapy arm is provided in Figure 1B. All clinically relevant subgroups demonstrated a reduction in the risk of progression in the talazoparib arm versus the control arm, with use of prior platinum resulting in the only 95% CI whose upper bound exceeded 1.0.

Figure 1. Progression-Free Survival: (A) Talazoparib versus Physician’s Choice of Therapy by BICR; (B) Subgroup Analysis.

Abbreviations: aBC = advanced breast cancer; CI = confidence interval; HR+ = hormone receptor positive; PCT = physician’s choice of therapy; PR = partial response; TALA = talazoparib; TNBC = triple-negative breast cancer

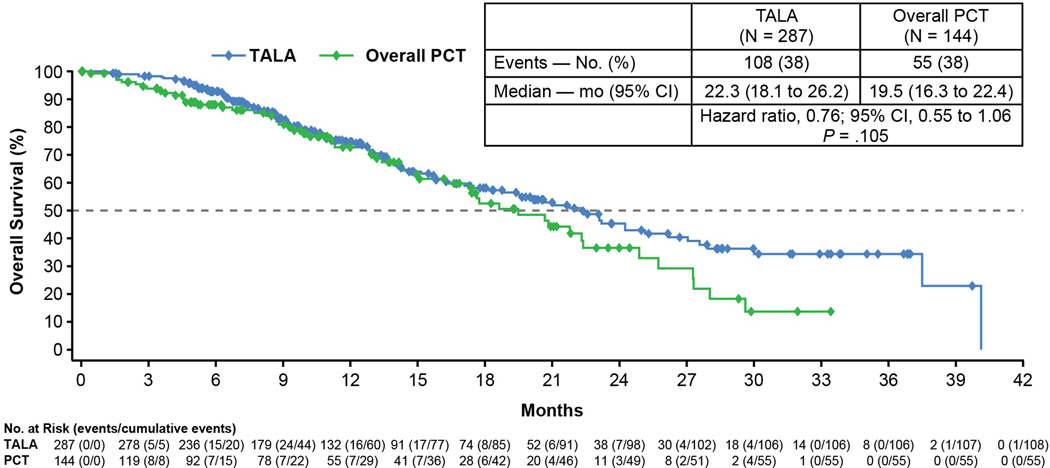

At the time of the primary analysis, 163 patients had died (108 in the talazoparib arm; 55 in the PCT arm). The median (95% CI) overall survival was 22.3 months (18.1, 26.2) in the talazoparib group and 19.5 months (16.3, 22.4) in the chemotherapy group (HR was 0.76; 95% CI: 0.55, 1.06, P=0.105) (Figure 2). Anticancer therapy post-study was received by 62% and 68% of patients for talazoparib and chemotherapy, respectively. Use of platinum therapy was similar in the 2 arms (approximately one-third of patients received either carboplatin or cisplatin post-study); however, the control arm had higher usage of a PARP inhibitor (18% vs. <1%) post study.

Figure 2. Interim Overall Survival Analysis.

CI = confidence interval; PCT = physician’s choice of therapy; TALA = talazoparib

The response rate (95% CI) by investigator was 62.6% (55.8, 69.0) for patients treated with talazoparib and 27.2% (19.3, 36.3) for those receiving chemotherapy, with 5.5% of patients in the talazoparib arm experiencing a complete response compared with zero in the chemotherapy arm (Table 2). Median time to response was 2.6 months for the patients in the talazoparib arm and 1.7 months for chemotherapy. Response rate by subgroup is provided in Supplemental Table S2.

Table 2.

Secondary and Exploratory Efficacy Endpoints.

| TALA | Overall PCT | |

|---|---|---|

| Best overall response (measurable disease) a | n = 219 | n = 114 |

| Complete response, No. (%) | 12 (5.5) | 0 |

| Partial response, No. (%) | 125 (57.1) | 31 (27.2) |

| Stable disease, No. (%) | 46 (21.0) | 36 (31.6) |

| Nonevaluable, No. (%) | 4 (1.8) | 19 (16.7) |

| Objective response by investigator (measurable disease) a | n = 219 | n = 114 |

| ORR, % (95% CI) | 62.6 (55.8, 69.0) | 27.2 (19.3, 36.3) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI); 2-sided P valueb | 4.99 (2.9, 8.8); P<0.0001 | |

| Clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks (CBR24; ITT) | n = 287 | n = 144 |

| CBR24, % (95% CI) | 68.6 (62.9, 74.0) | 36.1 (28.3, 44.5) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI); 2-sided P valueb | 4.28 (2.69, 6.83); P<0.0001 | |

| DOR by investigator (subgroup with objective response) | n = 137 | n = 31 |

| Median (IQR), mo | 5.4 (2.8–11.2) | 3.1 (2.4–6.7) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; CBR24 = Clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks; DOR = duration of response; ITT = intent to treat; IQR = interquartile range; ORR = overall response rate; RECIST = Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors; TALA = talazoparib.

Per RECIST version 1.1, confirmation of complete response or partial response was not required.

CMH=Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel.

The clinical benefit rate at 24 weeks was 68.6% and the median response duration was 5.4 months (Table 2; Figure S3) for patients treated with talazoparib compared with 36.1% and 3.1 months for chemotherapy. (Table 2; Figure S3).

Safety

Common adverse events included anemia, fatigue, and nausea for the talazoparib arm and nausea, fatigue, and neutropenia for the chemotherapy arm (Table 3). Grade 3 or 4 hematologic adverse events occurred in 55% patients on talazoparib versus 38% of patients on chemotherapy, whereas grade 3 nonhematologic adverse events occurred in 32% of patients on talazoparib versus 38% of patients on chemotherapy. The majority of nonhematologic adverse events in the talazoparib arm were grade 1 in severity. Adverse events resulting in discontinuation occurred in 5.9% versus 8.7% of patients receiving talazoparib versus chemotherapy, respectively. Adverse events resulting in dose modification occurred in 66% versus 60% of patients receiving talazoparib versus chemotherapy, respectively. The most common adverse events leading to dose modification in the talazoparib arm were anemia, neutropenia, and thrombocytopenia, whereas in the chemotherapy arm, they were neutropenia, palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia, nausea, and diarrhea. For patients who had at least one hematological adverse event, an analysis of dose modification over time was performed, comparing month 1, 2, 3, 4–6, 7–12, and >12 months. By months 4–6 following the first dose of talazoparib, approximately half of patients had experienced at least one dose interruption or dose reduction (Supplemental Table S3). Serious adverse events related to study drug were reported in 9% of patients for both talazoparib and chemotherapy, with anemia being the most common for talazoparib and neutropenia for chemotherapy. One case of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) occurred in a 59-year-old female patient on the chemotherapy arm who received capecitabine. This patient was randomized on 26 August 2014 and was diagnosed with acute promyelocytic leukemia on 12 March 2015. The patient had been diagnosed with breast cancer in 1993, experienced relapses in 2007, 2010, and 2014 and had been treated with multiple courses of radiation therapy and chemotherapy. One drug-related death was observed in each arm: veno-occlusive disease in the talazoparib arm as diagnosed by the trial site, noted on imaging without biopsy evidence or classical signs and one patient with sepsis in the chemotherapy arm. No clinically significant cardiovascular toxicity was observed. Hepatic toxicity was more common in the chemotherapy group (9% vs. 20% for talazoparib and chemotherapy, respectively).

Table 3.

Adverse Events.

| TALA (n = 286) | Overall PCT (n = 126) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event (AE), No. (%) | 282 (98.6) | 123 (97.6) | ||||||

| Seriousa | 91 (31.8) | 37 (29.4) | ||||||

| Serious and drug related | 26 (9.1) | 11 (8.7) | ||||||

| Grade 3 or 4 serious | 73 (25.5) | 32 (25.4) | ||||||

| Resulting in permanent drug discontinuation | 17 (5.9) | 11 (8.7) | ||||||

| Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |||||

| Hematologic b | ||||||||

| Patients with ≥1 hematologic AE, No. (%) | 140 (49.0) | 17 (5.9) | 29 (23.0) | 19 (15.1) | ||||

| Anemia | 110 (38.5) | 2 (0.7) | 5 (4.0) | 1 (0.8) | ||||

| Neutropenia | 51 (17.8) | 9 (3.1) | 25 (19.8) | 19 (15.1) | ||||

| Thrombocytopenia | 32 (11.2) | 10 (3.5) | 2 (1.6) | 0 | ||||

| Leukopenia | 18 (6.3) | 1 (0.3) | 8 (6.3) | 3 (2.4) | ||||

| Lymphopenia | 9 (3.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.8) | ||||

| Febrile neutropenia | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | ||||

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |

| Nonhematologic c | ||||||||

| Patients with ≥1 nonhematologic AE, No. (%) | 91 (31.8) | 48 (38.1) | ||||||

| Fatigue | 84 (29.4) | 55 (19.2) | 5 (1.7) | 0 | 33 (26.2) | 17 (13.5) | 4 (3.2) | 0 |

| Nausea | 97 (33.9) | 41 (14.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 34 (27.0) | 23 (18.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0 |

| Headache | 66 (23.1) | 22 (7.7) | 5 (1.7) | 0 | 20 (15.9) | 7 (5.6) | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Alopecia | 65 (22.7) | 7 (2.4) | 0 | 0 | 25 (19.8) | 10 (7.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Vomiting | 45 (15.7) | 19 (6.6) | 7 (2.4) | 0 | 14 (11.1) | 13 (10.3) | 2 (1.6) | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 50 (17.5) | 11 (3.8) | 2 (0.7) | 0 | 14 (11.1) | 12 (9.5) | 7 (5.6) | 0 |

| Constipation | 44 (15.4) | 18 (6.3) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 16 (12.7) | 11 (8.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Decreased appetite | 44 (15.4) | 16 (5.6) | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 19 (15.1) | 8 (6.3) | 1 (0.8) | 0 |

| Back pain | 36 (12.6) | 17 (5.9) | 7 (2.4) | 0 | 12 (9.5) | 6 (4.8) | 2 (1.6) | 0 |

| Dyspnea | 28 (9.8) | 15 (5.2) | 7 (2.4) | 0 | 12 (9.5) | 4 (3.2) | 3 (2.4) | 0 |

| Palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome | 3 (1.0) | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 12 (9.5) | 13 (10.3) | 3 (2.4) | 0 |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 1 (0.3) | 5 (1.7) | 0 | 1 (0.8) | 5 (4.0) | 5 (4.0) | 0 |

PCT = physician’s choice of therapy; TALA = talazoparib; Data are No. (%). AE grades are evaluated based on National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.03. Patients with multiple AEs are counted once for each preferred term, system organ class, and overall. AEs with action taken of permanent discontinuation are taken from the AE electronic case report form.

“Serious” defined as any AE that results in death, is considered life-threatening or medically important, results in hospitalization/prolonged hospitalization or persistent/significant disability/incapacity, or is a congenital anomaly/birth defect.

The category of thrombocytopenia incudes reports of thrombocytopenia and decreased platelet count. The category of neutropenia includes reports of neutropenia, decreased neutrophil count, and neutropenic sepsis. The category of anemia includes reports of anemia and decreased hemoglobin. No cases of acute myeloid leukemia/myelodysplastic syndrome were reported in the talazoparib arm; 1 case was reported for a patient receiving capecitabine.

All AEs in ≥20% of patients or grade 3–4 AEs in ≥2.4% of patients. For these selected toxicities, no grade 4 AEs were reported in either arm.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

A statistically significant improvement in the estimated overall mean change from baseline in global health scale/quality of life (GHS/QoL) (per European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer quality of life questionnaire [EORTC QLQ-C30]) (95% CI) was documented for the talazoparib arm compared with a statistically significant deterioration in the chemotherapy arm (3.0 [95% CI: 1.2, 4.8] vs. −5.4 [−8.8, −2.0]; P<0.0001). A statistically significant delay was observed in the time to clinically meaningful deterioration in GHS/QoL favoring talazoparib (Figure S4). In addition, talazoparib resulted in a statistically significant improvement in the estimated overall mean change from baseline in breast symptoms scale (per EORTC QLQ-BR23) compared with non-significant change in the chemotherapy arm (−5.1 [95% CI: −6.7, −3.5] vs. −0.1 [−2.9, 2.6]; P=0.002). (Figure S5).

DISCUSSION

The EMBRACA trial is a controlled phase 3 clinical trial conducted in patients with advanced breast cancer that expresses a gBRCAm comparing a PARP inhibitor, talazoparib, to chemotherapy. Talazoparib resulted in a 46% reduction in the risk of progression or death by blinded central review (HR 0.54, 95% CI: 0.41, 0.71), with a doubling of the response rate (62.6% talazoparib vs. 27.2% PCT). All clinically relevant subgroups in the progression-free survival analysis favored talazoparib.

All secondary efficacy endpoints favored talazoparib over chemotherapy, including response rate and duration. Time-to-event endpoints (progression-free and overall survival, response duration, and time to clinical deterioration in QoL) were all superior with talazoparib. A subset of patients showed long-lasting responses to talazoparib. This was not seen with chemotherapy. Correlative studies on archival tumor specimens and blood will investigate whether a biologic signature can predict these exceptional responders. This trial was prospectively designed to detect an improvement in overall survival; interim survival data are promising although survival data are immature. This is encouraging given that approximately one-third of patients received subsequent platinum (both arms), and 18% of patients received a subsequent PARP inhibitor (control arm).

In the OlympiAD trial, olaparib also demonstrated an improvement in progression-free survival (HR 0.58, 95% CI: 0.43, 0.80).13 Baseline characteristics differed in the study populations: EMBRACA included patients with locally advanced breast cancer, a higher proportion of patients naïve to cytotoxic chemotherapy for advanced breast cancer as well as a higher proportion of patients with hormone receptor-positive disease.

It is important to note both the qualitative and quantitative differences in safety comparing talazoparib to standard breast cancer chemotherapy. Most grade 3–4 toxicities associated with the use of talazoparib were hematologic laboratory abnormalities and not associated with substantial clinical sequelae or resulting in drug discontinuation. In both patient-reported GHS/QoL and breast symptoms scale, statistically significant overall improvements and statistically significant delays in the times to clinically meaningful deterioration were noted. It remains important to note that we are highlighting an improvement of only 3 months. Much more progress is needed.

One limitation to this phase 3 trial is the open-label design, necessitated by the mix of oral and intravenous treatment options in the chemotherapy arm. Eighteen patients in the control arm (compared with 1 patient in the talazoparib arm) withdrew consent before the first dose of study drug, leading to censoring for the primary efficacy endpoint. Of note, many of these patients consented to be followed for overall survival; all received further anticancer therapy (including agents that were part of the control arm). To ensure robustness of the results of this open-label trial, the primary analysis was based on blinded independent central review for the intent-to-treat population.

Several studies have evaluated the use of platinum agents in patients with germline BRCA mutations.14,15 Byrski et al reported a response rate of 80% in 20 patients with a BRCA1 mutation treated with cisplatin.14 The TNT trial, reported during the course of EMBRACA, showed an objective response rate of 68% with carboplatin vs. 33% with docetaxel in 43 patients with metastatic triple negative breast cancer and a known BRCA mutation.15 The EMBRACA trial permitted platinum-based agents to be used before study (which occurred in ≈20% of patients) as long as patients had no objective progression by RECIST criteria within 8 weeks of completing platinum therapy or following the trial (which occurred in one-third of patients). The failure to include platinum-based agents as an option in the control is a limitation of this trial, and a head-to-head comparison of a PARP inhibitor to platinum therapy is needed to understand the relative efficacy, toxicity, and effects on patient-reported outcomes. Additionally, the EMBRACA trial did not evaluate the sequencing of PARP and platinum-based drugs after progression on either agent. Future studies are needed to compare platinum-based agents to PARP inhibitors and to compare response rate after progression on each inhibitor class.

In conclusion, talazoparib resulted in a statistically significant prolongation in progression-free survival compared with standard-of-care chemotherapy. Treatment-associated myelotoxicity was managed by dose modifications or delays. Improvements in patient-reported outcomes supported the tolerability of talazoparib. Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was sponsored by Medivation LLC, a Pfizer company. The authors would like to thank the patients and their families/caregivers for their participation, as well as the study centers and patient advocacy groups who supported this study.

Editorial and medical writing support funded by Pfizer Inc. were provided by Edwin Thrower, PhD, and Mary Kacillas of Ashfield Healthcare Communications.

Funding Disclosure

This study was sponsored by Medivation LLC, a Pfizer company.

REFERENCES

- 1.Helleday T. The underlying mechanism for the PARP and BRCA synthetic lethality: clearing up the misunderstandings. Mol Oncol. 2011;5(4):387–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Javle M, Curtin NJ. The potential for poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitors in cancer therapy. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2011;3(6):257–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. PARP inhibitors: Synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science. 2017;355(6330):1152–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murai J, Huang SY, Das BB, et al. Trapping of PARP1 and PARP2 by clinical PARP inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2012;72(21):5588–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murai J, Huang SY, Renaud A, et al. Stereospecific PARP trapping by BMN 673 and comparison with olaparib and rucaparib. Mol Cancer Ther. 2014;13(2):433–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rouleau M, Patel A, Hendzel MJ, Kaufmann SH, Poirier GG. PARP inhibition: PARP1 and beyond. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10(4):293–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shen Y, Rehman FL, Feng Y, et al. BMN 673, a novel and highly potent PARP1/2 inhibitor for the treatment of human cancers with DNA repair deficiency. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19(18):5003–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.de Bono J, Ramanathan RK, Mina L, et al. Phase I, dose-escalation, two-part trial of the PARP inhibitor talazoparib in patients with advanced germline BRCA1/2 mutations and selected sporadic cancers. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(6):620–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turner N, Telli ML, Rugo HR, Mailliez A, Ettl J, Grischke E, Mina LA, Balmana J, Fasching PA, Hurvitz SA, Wardley AW, Chappey C, Verret, Hannah AL, Robson ME Final results of a phase 2 study of talazoparib (TALA) following platinum or multiple cytotoxic regimens in advanced breast cancer patients (pts) with germline BRCA1/2 mutations (ABRAZO). ASCO 2017; 2017; Chicago, Illinois. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haybittle JL. Repeated assessment of results in clinical trials of cancer treatment. Br J Radiol. 1971;44(526):793–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peto R, Pike MC, Armitage P, et al. Design and analysis of randomized clinical trials requiring prolonged observation of each patient. I. Introduction and design. Br J Cancer. 1976;34(6):585–612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robson M, Im SA, Senkus E, et al. Olaparib for metastatic breast cancer in patients with a germline BRCA mutation. N Engl J Med 2017;377(6):523–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Byrski T, Dent R, Blecharz P, et al. Results of a phase II open-label, non-randomized trial of cisplatin chemotherapy in patients with BRCA1-positive metastatic breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res 2012;14:R110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tutt A EP, Tovey H, Cheang MCU, et al. Carboplatin in BRCA1/2-mutated and triple-negative breast cancer BRCAness subgroups: the TNT Trial. Nat Med 2018. Apr 30. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.