Abstract

BACKGROUND

Thermo-expandable urethral stent (Memokath 028) implantation is an alternative treatment for older patients with lower urinary tract symptoms and benign prostatic obstruction. Following prostatic urethral stent implantation, minor complications such as urinary tract infection, irritative symptoms, gross hematuria, and urethral pain have been observed; however, there are no reports of life-threatening events. Herein, we report a critical case of Fournier’s gangrene that occurred 7 years after prostatic stenting.

CASE SUMMARY

An 81-years-old man with benign prostatic hyperplasia (volume, 126 ccs; as measured by transrectal ultrasound) had undergone insertion of a thermo-expandable urethral stent (Memokath 028) as he was unfit for surgery under general anesthesia. However, the patient had undergone a suprapubic cystostomy for recurrent acute urinary retention 4 years after the insertion of prostatic stent (Memokath 028). We had planned to remove the Memokath 028; however, the patient was lost to follow-up. The patient presented to the emergency department 3 years after the suprapubic cystostomy with necrotic changes from the right scrotum to the right inguinal area. In digital rectal examination, tenderness and heat of prostate was identified. Also, the black skin color change with foul-smelling from right scrotum to right inguinal area was identified. In computed tomography finding, subcutaneous emphysema was identified to same area. He was diagnosed with Fournier’s gangrene based on the physical examination and computed tomography findings. In emergency room, Fournier’s gangrene severity index value is seven points. Therefore, he underwent emergent extended surgical debridement and removal of the Memokath 028. Broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics were administered and additional necrotic tissue debridement was performed. However, the patient died 14 days after surgery due to multiorgan failure.

CONCLUSION

If Memokath 028 for benign prostatic hyperplasia is not working in older patients, its rapid removal may help prevent severe complications.

Keywords: Urethral stents, Minimally invasive surgery, Complication, Fournier’s gangrene, Benign prostatic hyperplasia, Case report

Core Tip: Herein, we report a life-threatening complication occurring several years after Memokath 028 implantation in an older and frail patient with benign prostatic hyperplasia for the first time. Memokath 028 is a permanent stent, but the long-term indwelling of Memokath 028 which is not working can be caused to acute bacterial prostatitis and epididymitis because of urinary tract infection. Eventually, our report reveals that Fournier’s gangrene associated with genitourinary organ infection such as acute bacterial prostatitis and epididymitis may occur in elderly unless the stent is removed. This report provides a good example of the management of patients with permanent or temporary prostatic stents for benign prostatic hyperplasia.

INTRODUCTION

Bladder outlet obstruction (BOO) associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is a common cause of lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS). In men, the incidence of BOO with BPH increases with age, affecting up to 80% of men by 70 years of age[1]. Currently, the surgical treatment options for BPH vary among patients with BPH refractory to medical therapy[2]. Minimally invasive surgery (MIS) for patients with BPH has recently been developed[3].

Prostatic urethral stenting is an MIS technique used to treat BPH. This has evolved with the development of materials, procedures, shapes, and plasticity[4]. Memokath 028 (Pnn Medical, Denmark) is a non-epithelializing thermo-expandable prostatic urethral stent made of nickel and titanium[5]. In a previous study, Memokath 028 implantation reduced the International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS) and improved uroflowmetry parameters[6]. It is also a feasible option for frail and older patients with refractory to medical treatment of BPH who are contraindicated for first choice of BPH surgery, such as transurethral resection of the prostate (TURP) or Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate under general or spinal anesthesia[7,8].

Some cases of minor complications following Memokath 028 implantation have been reported[9]. However, to our knowledge, there are no reports of fatal complications of Memokath 028 implantation. Herein, we report a critical case of Fournier’s gangrene (FG) in a patient who had undergone Memokath 028 insertion for BPH.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

An 88-year-old man presented to the emergency room with a complaint of a skin color change in the right scrotal area for 1 d.

History of present illness

The patient had right scrotal pain and swelling for 1 wk before presenting with a red skin color change in the right scrotal area. The patient was initially administered oral fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin) in accordance with epididymitis for seven days, but the symptoms was aggravated, and skin color was changed from red to black with foul-smelling.

History of past illness

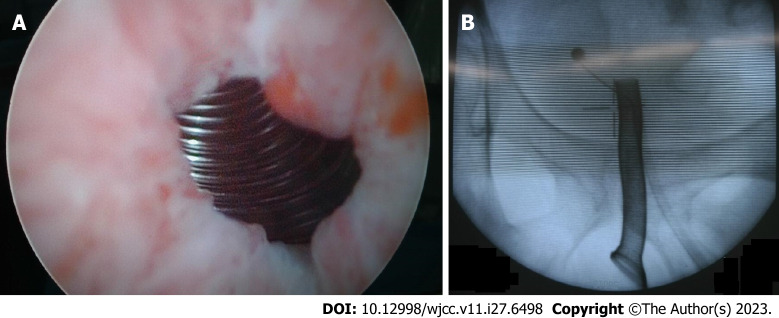

Seven years prior, the patient had visited the urology department for voiding dysfunction. The patient had a-blocker (silodosin 8 mg daily) and 5 alpha reductase inhibitor (finasteride once daily) for several years, but voiding symptom was aggravated. The total IPSS score was 26, and the Quality of Life (QoL) score was 5. On uroflowmetry, the maximal flow rate (Qmax) was 6.5 mL/sec, voiding volume was 182 mL, and residual urine volume was 258 mL. The prostate volume was 126 cc on transrectal ultrasonography. He was diagnosed with refractory to medical therapy for LUTS with BOO and we planned a TURP. However, he was not suited for surgery under general anesthesia because of a high (grade III) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score: History of non-ST elevated myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), cerebrovascular accident, and poor-controlled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Also, the spinal anesthesia cannot be performed in this patient because of spinal stenosis as consultation of anesthesiologist. Therefore, we decided MIS under local anesthesia (intraurethral lidocaine injection before procedure and analgesic injection intravenously during procedure) and implanted a thermo-expandable urethral stent (Memokath 028) (Figure 1). Six months after surgery, the Qmax was 14.8 mL/sec and the residual urine volume was 85 mL. Thereafter, he did not visit our urology department. The patient had undergone a suprapubic cystostomy 4 years after the initial surgery at a local medical center nearby his hometown, because the prostatic stent was not working.

Figure 1.

The insertion of thermo-expandable prostatic stent (Memokath 028) in cystoscopy and C-arm view. A: Cystoscopy; B: C-arm view.

Personal and family history

No relevant personal or family history was identified.

Physical examination

On physical examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 110/70 mmHg, heart rate was 90/min, body temperature was 36.0°C, and oxygen saturation was 96% in room air. The skin color change indicated necrosis and ranged from the right lower abdomen to the right scrotum (Figure 2). The left lower abdomen, left scrotum, and penis were normal. In digital rectal examination, the tenderness and heat of entire prostate was identified.

Figure 2.

The initial finding of necrotic skin lesion in right scrotum and inguinal area.

Laboratory examinations

The levels of several serum inflammatory markers were elevated. The white blood cell count was 13.62 /uL, C-reactive protein level was 23.79 mg/dL, procalcitonin level was 7.12 ng/mL, serum lactate level was 3.5 mmol/L, serum creatinine level was 2.47 mg/dL, and serum glucose level was 133 mg/dL. In urine analysis, pyuria was identified (many/high power field) and Enterobactor cloacae was isolated in urine and blood culture (Table 1). The antibiotics susceptibility of microorganisms was described in Table 1. The Fournier’s gangrene severity index value was seven points: serum potassium level was 5.5 (1 point), serum creatinine level was 2.47 (3 point), and serum bicarbonate level was 16.3 (3 point).

Table 1.

The result of initial isolated microorganism and antibiotics susceptibility in urine, blood, wound, and prostatic stent specimen

|

Bacteria spp.

|

Antibiotics

|

Titer

|

Susceptibility

|

| Enterobacter cloacae | Ampicillin | ≥ 32 | R |

| Amoxicillin/Clavulanic acid | ≥ 32 | R | |

| Cefoxitin | ≥ 64 | R | |

| Ceftazidime | ≥ 64 | R | |

| Aztreonam | 32 | R | |

| Imipenem | ≤ 0.25 | S | |

| Amikacin | ≤ 2 | S | |

| Gentamicin | ≤ 1 | S | |

| Ciprofloxacin | ≥ 4 | R | |

| Piperacillin/Tazobactam | 32 | I | |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | ≥ 320 | R | |

| Cefepime | ≥ 64 | R | |

| Cefotaxime | ≥ 64 | R | |

| Cefazolin | ≥ 64 | R | |

| Ertapenem | ≤ 0.5 | S | |

| Tigecycline | 2 | S |

R: Resistant; S: Susceptible; I: Intermediate.

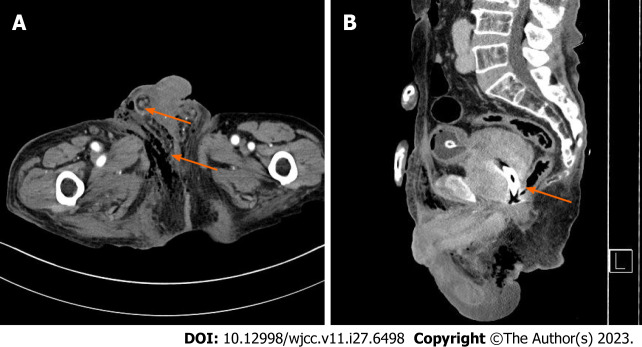

Imaging examinations

The abdominal-pelvic enhanced computed tomography revealed emphysematous changes and inflammatory infiltration in the right inguinal, suprapubic, scrotal, and perineal regions (Figure 3). In addition, the prostatic urethral stent was observed in the enlarged prostate (Figure 3). There was no abscess formation or emphysematous change in prostate and urethra.

Figure 3.

The initial computed tomography of this patient. A: Showed the emphysematous and inflammatory change in right scrotum and perineum (arrow); B: Revealed the thermo-expandable prostatic stent (Memokath 028) in huge prostate (arrow).

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

The final diagnosis was Fournier’s gangrene with acute prostatitis.

TREATMENT

The broad-spectrum antibiotics was started before surgical treatment: meropenem (0.5 g twice daily), vancomycin (1 g twice daily), and clindamycin 0.6 g thrice daily) were administered intravenously. After then, necrotic tissues with foul-smelling fluid throughout the right inguinal region, scrotum, and perineum were excised, and right orchiectomy was performed urgently due to necrotic change of right spermatic cord and epididymis. We performed culture swab in open wound; the Memokath 028 stent was removed simultaneously using cystoscopy (Figure 4). In cystoscopy, there was no necrotic change of urothelium in bladder, prostate, and urethra. However, the erythematous change of prostatic urethra was identified after removal of prostatic stent. We also performed culture swab in prostatic stent. The result of whole isolated microorganism was described in Table 1. In operative situation, the patient’s vital sign was unstable (persisted low blood pressure and tachycardia), therefore extended surgical debridement was incompletely conducted. After surgery, the patient’s condition worsened, and he was promptly admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) for management. Mechanical ventilation, broad-spectrum antibiotics administration, and total parenteral nutrition were required in the ICU. Same administration of broad-spectrum antibiotics before surgical treatment were performed postoperatively. Hemodialysis was initiated on postoperative day 1 due to the shutdown of urine output. Because of incomplete surgical debridement, necrotic tissues were additionally debrided several times postoperatively. The result of follow culture in urine and wound was negative. As a result of culture, the antibiotics was not changed as consultation of infectious disease center. However, despite the intensive management, the patient’s condition did not improve and elevated liver enzyme and bilirubin level were identified on postoperative 12 d. Also, total platelet count was gradually decreased (23000/L on postoperative 13 d) and prothrombin time and international normalized ratio was also prolonged. Finally, he died on postoperative 14 d.

Figure 4.

The gross findings after emergent surgical drainage of Fournier’s gangrene in right inguinal, scrotum, and perineum.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

On postoperative day 14, the patient died due to multiorgan failure.

DISCUSSION

FG is a necrotizing fasciitis that involves the perineal, perianal, or genital areas[10]. FG can progress rapidly and cause sepsis, multiorgan failure, and even death. The treatment of FG involves emergency extended surgical debridement and the use of extended broad-spectrum antibiotics[11,12]. Despite a combination of well-timed surgical and medical treatments, the mortality rate associated with FG is high[13]. The fatality rates of FG were reported to be approximately 16% and 8.8% in the 1900s and the 2000s, respectively[14]. El-Qushayri et al[15] demonstrated that the comorbid risk factors for mortality in FG were diabetes, heart disease, renal failure, and kidney disease. Sugihara et al[13] reported that old age, sepsis, and a broad range of FG debridement were associated with a high mortality rate. The cause of death in FG has been associated with sepsis and multiorgan failure[15]. Herein, although the patient had well-controlled diabetes mellitus (HbA1c level was 6.0), he was diagnosed NSTEMI before several years and acute renal injury was diagnosed in emergency room.

As mentioned earlier, prostatic stents for LUTS with BOO have been developed over several decades and their application is feasible in frail and older men who are contraindicated for conventional BOO surgery[7,8]. Perry et al[6] reported the long-term outcomes of older patients who underwent Memokath 028 placement for LUTS with BOO. This previous study demonstrated that Memokath 028 was a valuable treatment option for frail and older patients who could not undergo surgery. In our case, the patient was 81 years old when the insertion of prostatic stent (Memokath 028) was conducted and not suited for surgery because of a high ASA score; grade III, one or more severe systematic disease (poor-controlled COPD). Although the prostate volume was large (approximately 126 ccs), the IPSS and uroflowmetry parameters improved after Memokath 028 implantation. In addition, no aggravation of symptoms was observed during the follow-up period after surgery.

Meanwhile, the rate of complications following Memokath 028 placement was shown to be low in previous studies. Lee et al[7] reported that 3 of their 15 patients experienced minor complications after Memokath 028 implantation, such as dysuria and perineal discomfort. In a study on the 8-year outcomes of Memokath 028 implantation, the majority of complications were minor, such as migration, pain, or incontinence[6]. Severe and fatal complications after Memokath 028 implantation have not been reported in previous studies. Herein, we report a life-threatening complication that occurred several years after Memokath 028 insertion for the first time. Based on this result, we investigated that whether Memokath 028 is directly associated with FG or not.

First, same bacteria (Enterobacter cloacae) was isolated in urine, blood, wound, and prostatic stent. Also, acute prostatitis was diagnosed by digital rectal examination. In operation field, right spermatic cord and epididymis were changed to necrosis with foul-smelling fluid. Meanwhile, Igawa et al[16] demonstrated that urethral catheterization was associated with epididymitis. Based on these results, we hypothesized that the bacteria in Memokath 028 may be caused acute prostatitis and right epididymitis and necrotic change of right spermatic cord and epididymis was occurred as time passed.

Second, our patient had undergone a suprapubic cystostomy for acute urinary retention in a local urologic clinic nearby hometown 4 years after the insertion of the prostatic stent. Memokath 028 had not been working after 4 years of the insertion of prostatic stent. The suprapubic cystostomy was traditionally performed for management of acute bacterial prostatitis[17]. Nevertheless, acute prostatitis was diagnosed in our patient. Based on this result, Memokath 028 may be lead to acute prostatitis despite the suprapubic cystostomy which one of the treatment for acute bacterial prostatitis. Many studies on the efficacy of the Memokath 028 have reported that it is a permanent stent, and only minor complications occur during the indwelled state. To prevent severe complications, such as urosepsis or FG, we believe that the Memokath 028 stent should have been removed when the patient had undergone the suprapubic cystostomy. In addition, with the development of anesthetic techniques and MIS for BPH, other MIS techniques, such as anatomical endoscopic enucleation of the prostate or robot-assisted simple prostatectomy, may have been effective in this patient who had a large prostate volume exceeding 100 ccs.

CONCLUSION

Although most complications after Memokath implantation 028 for BPH are minor, life-threatening complications, such as FG, can occur in older and frail patients. To avoid severe complications, when Memokath 028 is not working, its rapid removal may be helpful in older and frail patients.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the legal representative of the patient for the publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: All the authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to disclose.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Peer-review started: May 3, 2023

First decision: July 17, 2023

Article in press: August 29, 2023

Specialty type: Urology and nephrology

Country/Territory of origin: South Korea

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Augustin G, Croatia; Hrgovic Z, Germany; Taskovska M, Slovenia S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

Contributor Information

Hee Chang Jung, Department of Urology, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu 42415, South Korea.

Yeong Uk Kim, Department of Urology, Yeungnam University College of Medicine, Daegu 42415, South Korea. jojo9174@hanmail.net.

References

- 1.Egan KB. The Epidemiology of Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Associated with Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms: Prevalence and Incident Rates. Urol Clin North Am. 2016;43:289–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2016.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dornbier R, Pahouja G, Branch J, McVary KT. The New American Urological Association Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia Clinical Guidelines: 2019 Update. Curr Urol Rep. 2020;21:32. doi: 10.1007/s11934-020-00985-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Franco JVA, Jung JH, Imamura M, Borofsky M, Omar MI, Escobar Liquitay CM, Young S, Golzarian J, Veroniki AA, Garegnani L, Dahm P. Minimally invasive treatments for benign prostatic hyperplasia: a Cochrane network meta-analysis. BJU Int. 2022;130:142–156. doi: 10.1111/bju.15653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vanderbrink BA, Rastinehad AR, Badlani GH. Prostatic stents for the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Curr Opin Urol. 2007;17:1–6. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3280117747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poulsen AL, Schou J, Ovesen H, Nordling J. Memokath: a second generation of intraprostatic spirals. Br J Urol. 1993;72:331–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1993.tb00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry MJ, Roodhouse AJ, Gidlow AB, Spicer TG, Ellis BW. Thermo-expandable intraprostatic stents in bladder outlet obstruction: an 8-year study. BJU Int. 2002;90:216–223. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2002.02888.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee G, Marathe S, Sabbagh S, Crisp J. Thermo-expandable intra-prostatic stent in the treatment of acute urinary retention in elderly patients with significant co-morbidities. Int Urol Nephrol. 2005;37:501–504. doi: 10.1007/s11255-005-2091-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sethi K, Bozin M, Jabane T, McMullin R, Cook D, Forsyth R, Dodds L, Putra LJ. Thermo-expandable prostatic stents for bladder outlet obstruction in the frail and elderly population: An underutilized procedure? Investig Clin Urol. 2017;58:447–452. doi: 10.4111/icu.2017.58.6.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armitage JN, Rashidian A, Cathcart PJ, Emberton M, van der Meulen JH. The thermo-expandable metallic stent for managing benign prostatic hyperplasia: a systematic review. BJU Int. 2006;98:806–810. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2006.06399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakkarainen TW, Kopari NM, Pham TN, Evans HL. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes. Curr Probl Surg. 2014;51:344–362. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chernyadyev SA, Ufimtseva MA, Vishnevskaya IF, Bochkarev YM, Ushakov AA, Beresneva TA, Galimzyanov FV, Khodakov VV. Fournier's Gangrene: Literature Review and Clinical Cases. Urol Int. 2018;101:91–97. doi: 10.1159/000490108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruketa T, Majerovic M, Augustin G. Rectal cancer and Fournier's gangrene - current knowledge and therapeutic options. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:9002–9020. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i30.9002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugihara T, Yasunaga H, Horiguchi H, Fujimura T, Ohe K, Matsuda S, Fushimi K, Homma Y. Impact of surgical intervention timing on the case fatality rate for Fournier's gangrene: an analysis of 379 cases. BJU Int. 2012;110:E1096–E1100. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eke N. Fournier's gangrene: a review of 1726 cases. Br J Surg. 2000;87:718–728. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2000.01497.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Qushayri AE, Khalaf KM, Dahy A, Mahmoud AR, Benmelouka AY, Ghozy S, Mahmoud MU, Bin-Jumah M, Alkahtani S, Abdel-Daim MM. Fournier's gangrene mortality: A 17-year systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2019.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Igawa Y, Wyndaele JJ, Nishizawa O. Catheterization: possible complications and their prevention and treatment. Int J Urol. 2008;15:481–485. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02075.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinberger M, Cytron S, Servadio C, Block C, Rosenfeld JB, Pitlik SD. Prostatic abscess in the antibiotic era. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:239–249. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]