Abstract

Extracellular vesicles, including exosomes, are regularly released by allogeneic cells after transplantation. Recipient antigen-presenting cells (APCs) capture these vesicles and subsequently display donor MHC molecules on their surface. Recent evidence suggests that activation of alloreactive T cells by the so-called cross-dressed APCs plays an important role in initiating the alloresponse associated with allograft rejection. On the other hand, whether allogeneic exosomes can bind to T cells on their own and activate them remains unclear. In this study, we showed that allogeneic exosomes can bind to T cells but do not stimulate them in vitro unless they are cultured with APCs. On the other hand, allogeneic exosomes activate T cells in vivo and sensitize mice to alloantigens but only when delivered in an inflammatory environment.

Keywords: alloantigen, basic (laboratory) research / science, immunobiology, major histocompatibility complex (MHC), T cell biology

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Exosomes are 50–100 nm diameter nanovesicles formed by inward budding of the limiting membrane of late endosomes, which accumulate inside the late endosomes as intraluminal vesicles (ILVs).1 Exosomes are then released by cells following fusion of the endosomal limiting membrane with the plasma membrane.1 They are secreted by virtually all eukaryotic cells and play a key role in intercellular communication through the transport of proteins, mRNA and miRNA.2

Exosomes secreted by bone marrow–derived lymphoid and myeloid cells participate in the development, perpetuation, and regulation of immune responses.1-4 These vesicles influence innate and adaptive immunity through multiple mechanisms, including cell–cell exchange of proteins such as antigens, cytokines, and costimulatory or co-inhibitory immune receptors as well as transfer of miRNA.3 For instance, exosomes are known to transfer antigens and MHC peptide complexes between DCs, thus amplifying antigen presentation to T cells.4 On the other hand, it is still unclear whether these exosomes can behave as antigen-presenting cells (APCs) and activate T cells on their own.

There is accumulating evidence suggesting that exosomes contribute to the immune response to allogeneic transplants.5-8 Exosomes carrying allogeneic MHC molecules are released from skin and organ allografts immediately after transplantation and migrate to the recipient's draining lymphoid organs.5,6 These vesicles are captured by APCs, which display allogeneic MHC molecules on their surface, a phenomenon called MHC cross-dressing.5,6,9 APCs cross-dressed with allogeneic MHC antigens can activate alloreactive T cells both in vitro and in vivo via a process referred to as semidirect allorecognition.10 There is accumulating evidence supporting the view that semidirect allorecognition triggers acute rejection after skin and organ transplantation.10,11 Finally, it is important to note that recent and elegant studies from the F. Lakkis’ laboratory have documented high numbers of donor MHC-cross-dressed cells inside pancreatic islet and heart allografts.12 Whether or not these cells activate alloreactive T cells locally and cause rejection cannot be ruled out.

In the present study, we investigated the antigenicity and immunogenicity of allogeneic exosomes in vitro and in vivo. We observed that allogeneic exosomes expressing MHC class I and II molecules bound to T cells. Nevertheless, they could not stimulate naive or memory alloreactive T cells in vitro on their own. However, in vivo, allogeneic exosomes were immunogenic because they induced a T cell alloresponse and second-set skin graft rejection but only when administered in an inflammatory environment. The significance of these results regarding the role of exosomes in alloimmunity and allograft rejection is discussed.

2 ∣. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 ∣. Isolation and characterization of exosomes

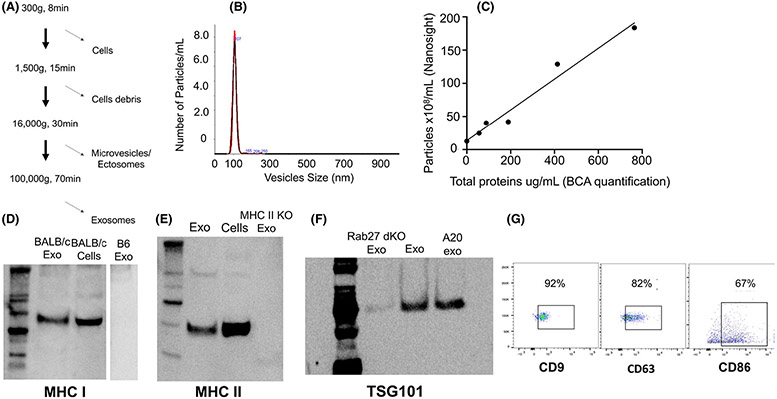

Exosomes were generated from spleen APCs as previously described.13 Briefly, spleen cells were cultured for 24 h, and exosomes were collected by a series of centrifugations as follows: cells were pelleted at 300 g for 8 min, and cell debris was removed at 1500 g for 15 min. Big vesicles were eliminated by ultracentrifugation at 16.000 g for 30 min, and lastly, the supernatant was centrifuged at 100 000 g for 70 min to collect exosomes (Figure 1A). The number of exosomes was assessed by nanoparticle tracking analysis, a technique combining light scattering and Brownian motion to detect particles in suspension. The total protein quantity was determined by Pierce BCA Protein Assay (Thermofisher) (Figure 1A,B). As shown in Figure 1C, there was a direct relationship between the number of vesicles and the protein content of the vesicle preparation. To confirm that the vesicles were exosomes, they were analyzed by western blot for expression of the exosome-specific markers CD9, CD63, and TSG101. Finally, the presence of antigen-presenting MHC class I and II proteins and the costimulatory receptor CD86 was evaluated by flow cytometry (Figure 1D-G).

FIGURE 1.

Exosome isolation, quantification, and characterization. (A) To isolate exosomes from culture media, cells were eliminated at 300 g for 8 min, cell debris was removed at 1500 g for 15 min, and microvesicles were pelleted after centrifugation at 16 000 g for 30 min. Lastly, exosomes were collected after a 70-min centrifugation at 100 000 g. (B) Exosomes were counted and sized using Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA). (C) Panel C shows the linear relationship between the protein content of exosomes measured with a BCA protein assay and the number of vesicles determined using NTA. (D) MHC I Kd from BALB/c mice was detected on BALB/c exosomes and cells by western blot but was absent from negative control B6 (Kb) exosomes. (E) MHC II molecules were detected on exosomes and cells using western blot, and control exosomes were obtained from MHC II KO cells. (F) The exosomal marker TSG101 was detected by western blotting of exosome preparations from BALB/c cells, A20 B cell lymphoma cells, and control Rab27a/b double KO cells, which do not secrete exosomes. (G) The expression of exosomal surface protein markers (CD9 and CD63) as well as the costimulation marker CD86 were detected by FACS (using exosomes previously captured with beads covered with anti-CD9 antibodies)

2.2 ∣. Antigen cross-dressing and exosome-binding assays

T cells were isolated from mouse spleen, purified using a CD3-negative selection kit (Miltenyi) and cultured for 4 h with allogeneic exosomes (0, 25, 50, or 100 ug) in AIMV medium. T cell binding was assessed using flow cytometry. The cells were labeled with fluorescent antibodies directed against H-2 Kb (AF6-88.5 Biolegend), H-2Kd (SF1-1.1 Biolegend), I-Ab (AF6-120.1 Biolegend), I-Ad (AMS-32.1 eBioscience), as described elsewhere.6 Briefly for IFC acquisition of cells was performed with the ImageStream instrument (Amnis EMD Millipore), using low-speed fluidics, at 40× magnification. Data analysis was performed using IDEAS 6.1 image processing and statistical analysis software (Amnis EMD Millipore). 3 × 105 leukocytes were analyzed per organ and time point.

2.3 ∣. T cell ELISPOT assays

Alloresponses by T cells were measured as previously described.14 Briefly, 96-well ELISPOT plates (Polyfiltronics, Rockland, MA) were coated with an anti-γIFN capture mAb (R4-6A2) in PBS overnight. Half a million T cells per well were cultured for 24 hours with irradiated allogeneic cells (direct alloresponse) (5 × 105 cells/well). After washing, a biotinylated anti-γIFN detection antibody (XMG 1.2) was added overnight. The plates were developed, and the resulting spots were counted and analyzed on a computer-assisted ELISA spot image analyzer (C.T.L.).

2.4 ∣. Skin transplantation

Full-thickness skin grafts (2 × 3 cm) were placed on the recipients’ flank area according to a technique described elsewhere.15

2.5 ∣. Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using STATView software (Abacus Concepts, Inc.) and Graphpad Prism, version 5.0b. p-values were calculated using paired t-test. p-values <.05 were considered statistically significant.

3 ∣. RESULTS

3.1 ∣. Exosomes bind to T lymphocytes

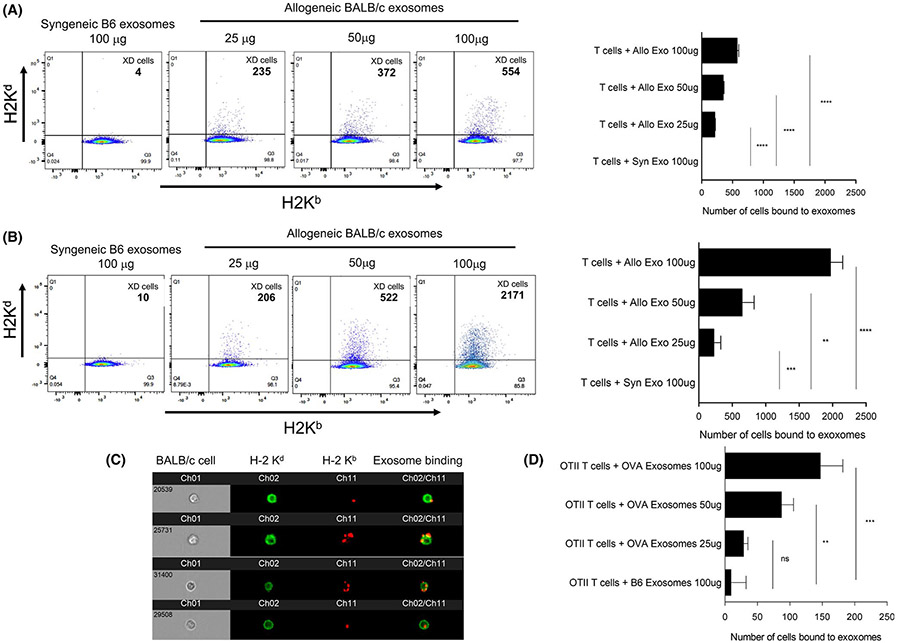

It is well established that exosomes bind and are regularly taken up by phagocytes, including macrophages and dendritic cells.16 This process is mediated via different mechanisms involving surface receptors such as adhesion molecules, tetraspanins, lectins, and phosphatidyl serine binding to lipid-binding proteins.16 On the other hand, whether exosomes bind to lymphocytes has not been thoroughly investigated. To address this question, exosomes were isolated from the spleen of BALB/c (H-2d) or C57Bl/6 (B6, H-2b) mice, counted, and characterized, as described in the Methods section and Figure 1. Exosomes were then placed in culture for 4 hours (time needed to reach maximum binding, Figure S1) with purified T or B lymphocytes derived from a naïve or an allosensitized B6 mouse. The binding of exosomes was assessed via the presence of allogeneic Kd MHC class I on the surface of lymphocytes measured by FACS and imaging flow cytometry as previously described.6 Transfer of MHC through cell–cell contact between BALB/c B cells and B6 T cells was measured as a positive control (Figure S2). Syngeneic B6 exosomes were used as a negative control. We observed that exosomes bound to naïve T cells in a dose-dependent fashion (Figure 2A). The binding of exosomes to T cells was confirmed by microscopic observations obtained using imaging flow cytometry (Figure 2C). It is noteworthy that while MHC class I transfer was also observed with B cells from naive mice, it was nearly 10 times higher than that detected with their T cell counterparts (Figure S3). Next, we evaluated whether allospecific memory T cells had a higher ability to bind allogeneic exosomes. To test this, B6 mice were grafted with a BALB/c skin patch, and their splenic T cells isolated 30 days posttransplant. As shown in Figure 2B, markedly enhanced exosome binding was observed with these T cells.

FIGURE 2.

T cell binding to exosomes. (A) Spleen T cells from naive B6 mice were cultured for 4 hours with BALB/c exosomes (time necessary to reach maximum MHC cross-dressing, as shown in Figure S1). The binding of exosomes was assessed by the presence of BALB/c H-2 Kd MHC class I molecules on B6 cells by FACS. The left panel shows a representative plot obtained with different quantities of allogeneic exosomes: 25 μg, 50 μg, and 100 μg, corresponding to 109, 2 × 109, and 4 × 109 vesicles. Syngeneic B6 exosomes (100 μg) were used as negative controls. The right panel shows the mean number of T cells bound to exosomes ±SD with 3–5 mice tested individually. (B) Spleen T cells were isolated from B6 mice transplanted with a BALB/c skin graft 30 days prior to coculture with BALB/c exosomes at different concentrations. Binding of exosomes to T cells was tested by FACS as described for panel (A). (C) Representative microscopic images obtained using imaging flow cytometry with B6 exosomes (expressing Kb, red) bound to BALB/c T cells (expressing Kd, green) are shown. (D) OT-II TCR transgenic T cells, which recognize the ovalbumin (OVA) peptide bound to Ad MHC class II were cultured for 4 hours with different quantities of exosomes secreted by spleen cells derived from mAct-OVA transgenic mice (OVA exosomes). The binding of exosomes to OT-II T cells was evaluated by FACS through the expression of Kb-SIINFEKL OVA peptide complex with the mAb 25-D1.16. The results are expressed as number of OT-II T cells bound to OVA exosomes ±SD obtained in 3 separate experiments. For panels (B)-(D), 3 × 105 cells were tested per time point. p-values: * p < .05, ** p < .005, *** p < .0005, and **** p < .00005

Next, we further tested the ability of exosomes to bind to T cells using T cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice. T cells were isolated from the spleen of B6 OT-II TCR transgenic mice whose CD4+ T cells recognize chicken ovalbumin (OVA) peptide 323–339 (OVA 323–339) bound to Ab MHC class II molecules. B6 OT-II T cells were cultured for 4 hours with exosomes from spleen cells derived from either wildtype (wt) B6 mice or B6 mAct-OVA transgenic mice (B6-OVA exosomes), which ubiquitously express the OVA gene under control of the actin promoter. The binding of exosomes to T cells was detected by FACS via the presence of MHC class I Kb bound to OVA SIINFEKL peptide on T cells using a monoclonal antibody, 25-D1.16. As shown in Figure 2D, OVA-exosomes bound to OT-II T cells in a dose-dependent manner. No binding was detected with wt B6 exosomes. On the other hand, OVA-exosomes used at the highest dose (100 ug) bound poorly to B6 Tea TCR transgenic T cells, whose TCR is specific for the same Ab MHC class II molecules but bound to another peptide, MHC Eα 52–68 (57 ± 9 bound cells). Altogether, these results show that exosomes bind to T cells and suggest that this process relies at least partially on their TCR recognition of MHC-peptide antigen complexes.

3.2 ∣. Exosomes do not activate T cells unless bound to antigen-presenting cells

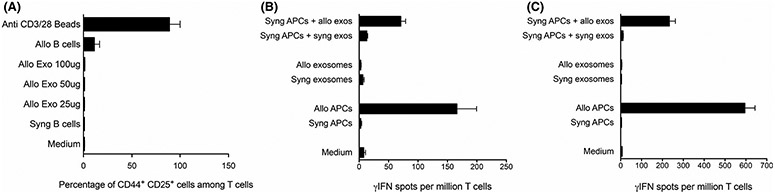

Next, we investigated whether binding of exosomes to T cells leads to their activation. To test this, B6 splenic T cells were isolated and cultured with allogeneic BALB/c exosomes for 24 hours. T cells were then tested by FACS for their surface expression of early activation markers CD25 and CD44. As expected, activation with allogeneic B cells (mixed lymphocyte reaction) and polyclonal stimulation with beads coated with anti-CD3/CD28 mAbs increased both the expression of CD25 and CD44 by T cells, whereas syngeneic B cells did not. In contrast, allogeneic exosomes failed to elicit a similar response. Likewise, allogeneic exosomes did not stimulate T cells isolated from mice sensitized to alloantigens with a previous skin allograft (Figure 3A). On the other hand, B6 APCs displaying on their surface B6 H-2d MHC molecules acquired after exposure to BALB/c exosomes (MHC cross-dressed cells) triggered CD25 and CD44 expression by T cells (semidirect alloresponse).

FIGURE 3.

In vitro activation of T cells by exosomes. (A) B6 spleen T cells were cultured with different quantities of allogeneic BALB/c exosomes for 24 hours (Allo Exo: 25 μg, 50 μg, and 100 μg, corresponding to 109, 2 × 109 and 4 × 109 vesicles). Cells were then washed, and expression of early surface activation markers CD25 and CD44 was tested by FACS. Positive controls included beads coated with anti-CD3 and CD28 mAbs and allogeneic BALB/c B cells (Allo B cells, MLR). Negative controls included T cells cultured with syngeneic B6 B cells (Syn B cells) or with medium alone. (B) T cells isolated from the spleen of naive BALB/c mice were stimulated for 48–72 hours in vitro with B6 allogeneic exosomes (Allo exosomes) or BALB/c cells cross-dressed with B6 exosomes. Negative controls included BALB/c T cells cultured with syngeneic BALB/c exosomes or BALB/c APCs cross-dressed or not with syngeneic BALB/c exosomes or medium alone. Positive controls included T cells from naive BALB/c mice cultured with B6 antigen-presenting cells (primary MLR). T cell activation was tested using a γIFN ELISPOT assay. (C) T cells were isolated from the spleen of BALB/c mice transplanted 30 days earlier with a B6 skin allograft. The T cells were stimulated in vitro and tested by ELISPOT for their γIFN secretion, as described in panel B. in B and C. The mean numbers of γIFN-producing cells per 106 T cells ±SD are shown. Three to five mice were individually tested

Next, allogeneic B6 exosomes and cells were tested for their ability to elicit in vitro γIFN cytokine production by T cells from naive BALB/c mice or BALB/c mice previously sensitized to alloantigens by a B6 skin allograft, using an ELISPOT assay. As expected, BALB/c T cells produced γIFN after co-culture with allogeneic (B6) but not syngeneic (BALB/c) B6 APCs, a phenomenon referred to as a direct alloresponse (Figure 3B).14 In contrast, allogeneic exosomes failed to stimulate γIFN production by T cells, whereas BALB/c APCs cross-dressed with allogeneic MHC via exosome exposure triggered γIFN secretion by T cells (semidirect alloresponse). Similar patterns of response but higher frequencies of γ-IFN spots were obtained with T cells from BALB/c mice that have been previously sensitized to alloantigens by a B6 skin allograft (Figure 3C). Altogether, these results demonstrate that allogeneic exosomes cannot activate naive or memory T cells in vitro unless they transfer their MHC molecules to APCs.

3.3 ∣. Allogeneic exosomes are immunogenic in vivo when present in an inflammatory environment

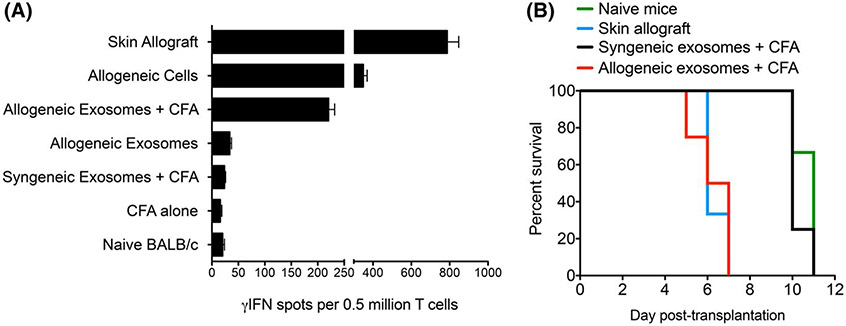

We next investigated whether allogeneic exosomes could trigger a T cell response in vivo. BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 109 B6 exosomes either alone or along with complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA). At day 10 postimmunization, spleen T cells were isolated and tested for their γIFN production after 48-h restimulation in vitro with irradiated B6 APCs using an ELISPOT assay, as previously described (direct alloresponse). Naïve BALB/c mice, mice injected with CFA alone, and mice injected with syngeneic BALB/c exosomes + CFA were tested as negative controls. BALB/c transplanted with a B6 skin allograft or injected with whole B6 allogeneic splenocytes were tested as positive controls. As shown in Figure 4A, high frequencies of γIFN-producing T cells were detected in mice sensitized with a B6 skin graft or B6 spleen cells. Very few spots (< 20) were observed with T cells from naïve mice or mice injected with CFA alone or syngeneic exosomes with CFA. Most importantly, T cells from mice injected with allogeneic exosomes + CFA produced γIFN, whereas those from mice injected only with allogeneic exosomes did not.

FIGURE 4.

In vivo T cell sensitization and second set skin allograft rejection induced by allogeneic exosomes. (A) BALB/c mice were injected intraperitoneally with 109 allogeneic B6 exosomes alone or with CFA. Ten days later, spleen T cells were tested by ELISPOT for their secretion of γIFN on 48–72 hours restimulation in vitro with allogeneic-irradiated B6 APCs (mixed lymphocyte reaction). Positive controls included BALB/c mice that had received a B6 skin allograft or had been injected with B spleen cells. Negative controls included naive BALB/c mice and BALB/c mice injected with CFA only. Results are expressed as the number of γIFN spots per 0.5 million cells ± SD, obtained with 3–5 mice tested individually. (B) BALB/c mice were first injected intraperitoneally with 109 allogeneic B6 exosomes along with CFA. Skin allografts were rejected within 8–10 days. Thirty-two days later, these mice received a B6 skin allograft and were monitored daily for rejection (red line). Naïve BALB/c mice (first set rejection) (green line) and mice formerly injected with syngeneic BALB/c exosomes and CFA (black line) were tested as negative controls for second set rejection. BALB/c mice that had received a first B6 skin allograft were tested as positive controls for second set rejection (blue line). Three to four mice were tested in each group. Results are expressed as percentage graft survival over time after skin transplantation

Finally, BALB/c mice were injected with either allogeneic B6 exosomes or syngeneic BALB/c exosomes along with CFA. Thirty-two days later, these mice received a B6 skin allograft and were monitored daily for rejection. Naïve mice were tested as negative controls and BALB/c mice having received a first B6 skin allograft were tested as positive controls. Naïve mice and mice injected with syngeneic exosomes rejected their allograft within 10–12 days posttransplant (Figure 4B). On the other hand, BALB/c mice previously injected with allogeneic exosomes or transplanted with a B6 skin patch had an accelerated rejection of B6 skin allografts (5–7 days, p < .01), a phenomenon called second set allograft rejection (Figure 4B).

4 ∣. DISCUSSION

Binding of extracellular vesicles to cells, involves various surface receptors such as adhesion molecules, tetraspanins, lectins, and phosphatidyl serine.16 Depending on the cell type, exosomes can remain attached to the plasma membrane and participate in antigen presentation or fuse with the membrane and release their intraluminal content or be fully internalized through the endosomal pathway and undergo either recycling or degradation.3,16

Seminal studies by Lechler et al. have documented the ability of APCs cross-dressed with allogeneic MHC molecules to activate alloreactive T cells in vitro and in vivo via the semidirect pathway.17-19 In 2016, several studies provided strong evidence suggesting that the semidirect antigen presentation pathway rather than passenger leukocytes was the driving force behind activation of alloreactive T cells of skin- and heart-transplanted mice.5-7 These studies also showed that MHC cross-dressing occurred through capture of donor exosomes by recipient APCs.5,6 Altogether, these observations suggested that donor exosomes released after transplantation contribute to acute rejection by eliciting semidirect T cell alloresponses. However, due to the lack of suitable methods to prevent exosome release or MHC cross-dressing of recipient APCs, this remains to be proven. Other studies have documented the role of MHC cross-dressing in allograft tolerance. Burlingham's group recently reported that DCs displaying allogeneic MHC molecules acquired from exosomes expressing PDL-1 or IL-35 are involved in T cell regulation associated with maternal microchimerism and donor-specific transfusion.20,21 In addition, A. Thomson's group provided evidence of the role of recipient DCs, cross-dressed with donor MHC class I and PDL-1, in tolerance of liver allografts.22 Taken together, these studies showed that exosomes released by allografts influence the outcome of alloimmunity toward rejection or tolerance through MHC cross-dressing. On the other hand, whether or not allogeneic exosomes can bind on their own to alloreactive T cells and activate them independently of cross-dressing has not been fully investigated.

Exosomes derived from professional APCs such as DCs, macrophages, and B cells display MHC–peptide complexes and costimulatory molecules (CD80 and CD86) on their surface.2 This suggests that they could bind and activate T cells via their TCR in an antigen-specific fashion. In support of this view, Raposo et al. formerly showed that vesicles released by EBV-transformed B cells cultured with a mycobacterial antigen stimulated MHC class II-restricted T cells in vitro.23 In addition, Quasi et al. have shown that exosomes loaded with OVA 323–339 peptides as well as exosomes derived from DCs pulsed with OVA proteins can activate DO11.10 CD4+ TCR transgenic T cells in vitro.24 In contrast, studies by Thery et al. showed that exosomes derived from H-Y+ male DCs could not activate CD4+ Marylin TCR transgenic T cells specific for an H-Y peptide.4 In the present study, we evaluated the ability of allogeneic exosomes to elicit a T cell response in vitro and in vivo. First, we showed that exosomes could bind directly to T cells in vitro. Our results using TCR transgenic T cells support the view that exosome binding was TCR-mediated. Next, we showed that although allogeneic exosomes displayed both allogeneic MHC class II and costimulatory molecules, they were unable to activate naive or memory T cells in vitro. On the other hand, APCs pulsed with the same allogeneic exosomes induced potent alloreactive T cell responses. These results corroborate previous observations by Thery et al. showing that APCs expressing MHC-H-Y peptide complexes acquired from H-Y+ exosomes could activate anti-H-Y CD4+ Marylin T cells, while H-Y+ exosomes alone could not.4 Likewise, H Vincent-Schneider et al. reported that exosomes bearing HLA DR1-HA 306–318 MHC peptide complexes needed dendritic cells to stimulate specific T cells.25 The apparent discrepancy between these studies may be explained by the fact that the number of allogeneic MHC-peptide complexes and costimulatory receptors present on exosomes naturally produced by APCs may be insufficient to reach the threshold necessary for T cell activation. In addition, lack of T cell activation by exosomes may be due to their inability to secrete cytokines such as IL-1, a key cytokine in APC-mediated antigen-specific T cell activation via the CD3-TCR complex.

Finally, we showed that injection of mice with the same allogeneic exosomes triggered inflammatory T cell responses in vivo and caused second set allograft rejection, but only when exosomes were delivered with CFA. We surmise that innate inflammation caused by CFA promoted donor MHC cross-dressing of APCs and subsequent activation of alloreactive T cells. In the absence of inflammation, it is conceivable that direct binding of allogeneic exosomes to T cells could suppress the T cell response either by competing with APCs through occupation of the TCR or even by delivering signals leading to anergy or cell death. This hypothesis is supported by the studies of Peche et al. showing that administration of allogeneic exosomes to rodents along with short-term anti-inflammatory treatment led to long-term survival of kidney allografts.26 Therefore, a better understanding of the mechanisms by which allogeneic exosomes influence T cell alloimmunity may lead to the design of novel tolerance strategies in transplantation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the NIH to Gilles Benichou, NIH R21AI100278, and NIH R01DK115618. Aurore Prunevieille was supported by a fellowship from the Ministère français de I'Enseignement et de la Recherche.

Funding information

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, Grant/Award Number: R01DK115618 and R21AI100278

Abbreviations

- APCs

antigen-presenting cells

- DCs

dendritic cells

- EVs

extracellular vesicles

- ILVs

intraluminal vesicles

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- MHC

major histocompatibility complex

- OVA

ovalbumin

- PD-L1

programmed death-ligand 1

- TCR

T cell receptor

- γIFN

gamma interferon

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by the American Journal of Transplantation.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kowal J, Tkach M, Thery C. Biogenesis and secretion of exosomes. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014;29:116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thery C, Zitvogel L, Amigorena S. Exosomes: composition, biogenesis and function. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(8):569–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gutierrez-Vazquez C, Villarroya-Beltri C, Mittelbrunn M, Sanchez-Madrid F. Transfer of extracellular vesicles during immune cell-cell interactions. Immunol Rev. 2013;251(1):125–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thery C, Duban L, Segura E, Veron P, Lantz O, Amigorena S. Indirect activation of naive CD4+ T cells by dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3(12):1156–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Q, Rojas-Canales DM, Divito SJ, et al. Donor dendritic cell-derived exosomes promote allograft-targeting immune response. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(8):2805–2820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marino J, Babiker-Mohamed MH, Crosby-Bertorini P, et al. Donor exosomes rather than passenger leukocytes initiate alloreactive T cell responses after transplantation. Science Immunology. 2016;1(1):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smyth LA, Lechler RI, Lombardi G. Continuous acquisition of MHC: peptide complexes by recipient cells contributes to the generation of anti-graft CD8+ T cell immunity. Am J Transplant. 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morelli AE, Larregina AT, Shufesky WJ, et al. Endocytosis, intracellular sorting, and processing of exosomes by dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;104(10):3257–3266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Markey KA, Koyama M, Gartlan KH, et al. Cross-dressing by donor dendritic cells after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation contributes to formation of the immunological synapse and maximizes responses to indirectly presented antigen. J Immunol. 2014;192(11):5426–5433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marino J, Paster J, Benichou G. Allorecognition by T Lymphocytes and allograft rejection. Front Immunol. 2016;7:582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harper SJF, Ali JM, Wlodek E, et al. CD8 T-cell recognition of acquired alloantigen promotes acute allograft rejection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(41):12788–12793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hughes AD, Zhao D, Dai H, et al. Cross-dressed dendritic cells sustain effector T cell responses in islet and kidney allografts. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(1):287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thery C, Amigorena S, Raposo G, Clayton A. Isolation and characterization of exosomes from cell culture supernatants and biological fluids. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2006;Chapter 3:Unit 3 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Benichou G, Valujskikh A, Heeger PS. Contributions of direct and indirect T cell alloreactivity during allograft rejection in mice. J Immunol. 1999;162(1):352–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Billingham RE, Medawar PD. The technique of free skin grafting in mammals. J Exp Biol. 1951;28:385. [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Niel G, D'Angelo G, Raposo G. Shedding light on the cell biology of extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2018;19(4):213–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tsang JY, Chai JG, Lechler R. Antigen presentation by mouse CD4+ T cells involving acquired MHC class II:peptide complexes: another mechanism to limit clonal expansion? Blood. 2003;101(7):2704–2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smyth LA, Herrera OB, Golshayan D, Lombardi G, Lechler RI. A novel pathway of antigen presentation by dendritic and endothelial cells: Implications for allorecognition and infectious diseases. Transplantation. 2006;82(1 Suppl):S15–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smyth LA, Afzali B, Tsang J, Lombardi G, Lechler RI. Intercellular transfer of MHC and immunological molecules: molecular mechanisms and biological significance. Am J Transplant. 2007;7(6):1442–1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sullivan JA, Tomita Y, Jankowska-Gan E, et al. Treg-cell-derived IL-35-coated extracellular vesicles promote infectious tolerance. Cell Rep. 2020;30(4):1039–1051 e1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bracamonte-Baran W, Florentin J, Zhou Y, et al. Modification of host dendritic cells by microchimerism-derived extracellular vesicles generates split tolerance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(5):1099–1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ono Y, Perez-Gutierrez A, Nakao T. et al. Graft-infiltrating PD-L1(hi) cross-dressed dendritic cells regulate antidonor T cell responses in mouse liver transplant tolerance. Hepatology. 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raposo G, Nijman HW, Stoorvogel W, et al. B lymphocytes secrete antigen-presenting vesicles. J Exp Med. 1996;183(3):1161–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qazi KR, Gehrmann U, Domange Jordo E, Karlsson MC, Gabrielsson S. Antigen-loaded exosomes alone induce Th1-type memory through a B-cell-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2009;113(12):2673–2683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vincent-Schneider H, Stumptner-Cuvelette P, Lankar D, et al. Exosomes bearing HLA-DR1 molecules need dendritic cells to efficiently stimulate specific T cells. Int Immunol. 2002;14(7):713–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peche H, Renaudin K, Beriou G, Merieau E, Amigorena S, Cuturi MC. Induction of tolerance by exosomes and short-term immuno-suppression in a fully MHC-mismatched rat cardiac allograft model. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(7):1541–1550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.