Abstract

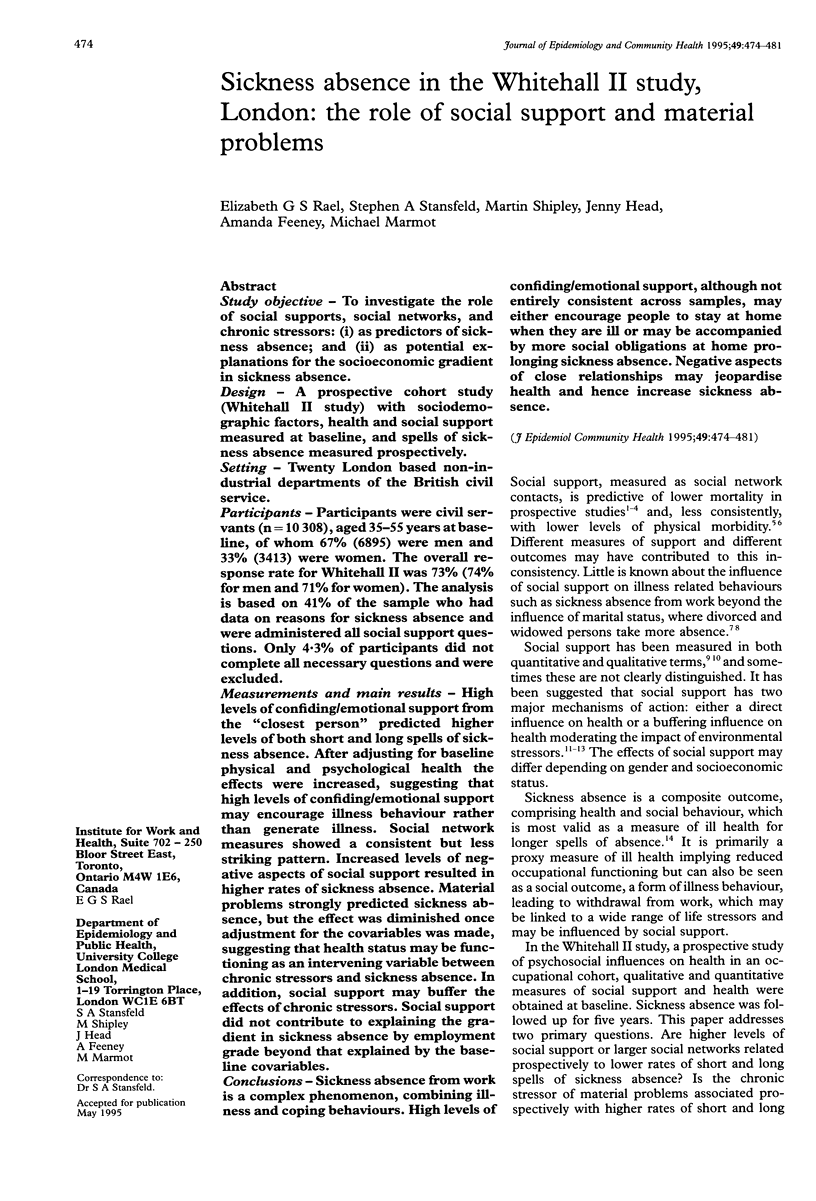

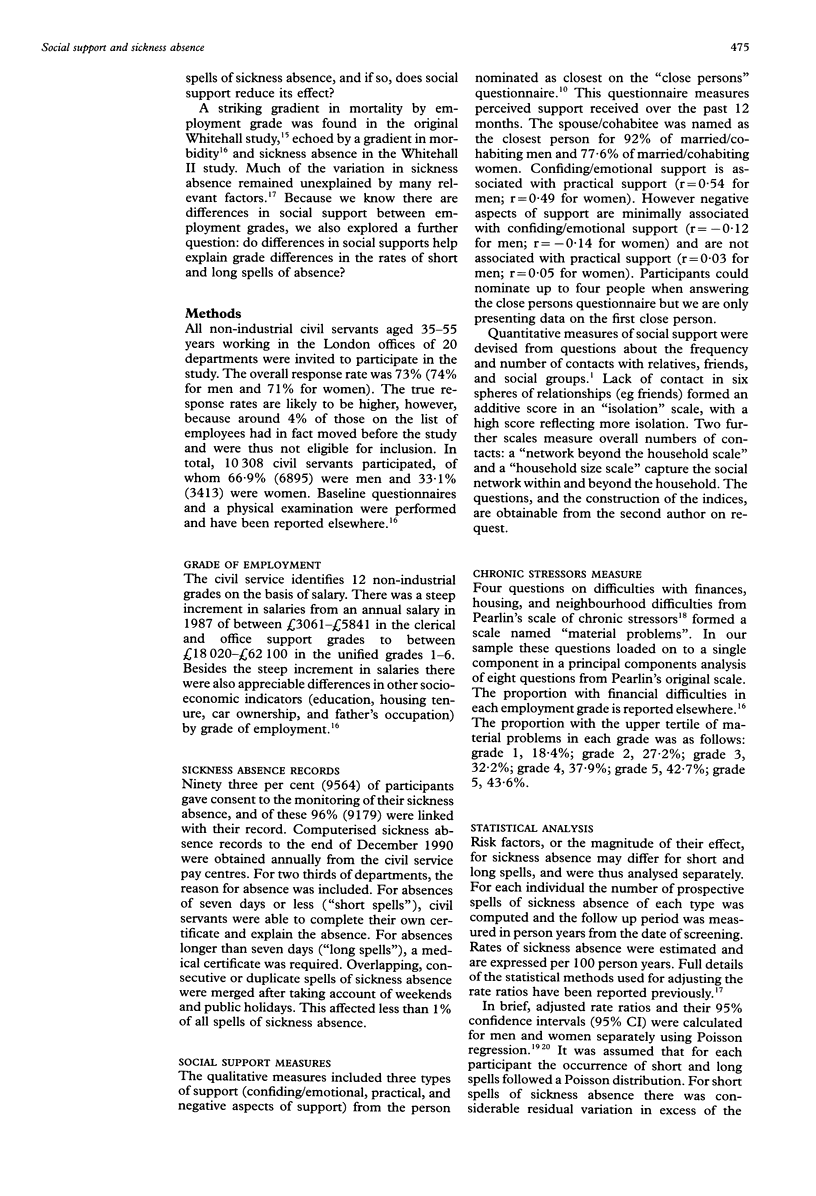

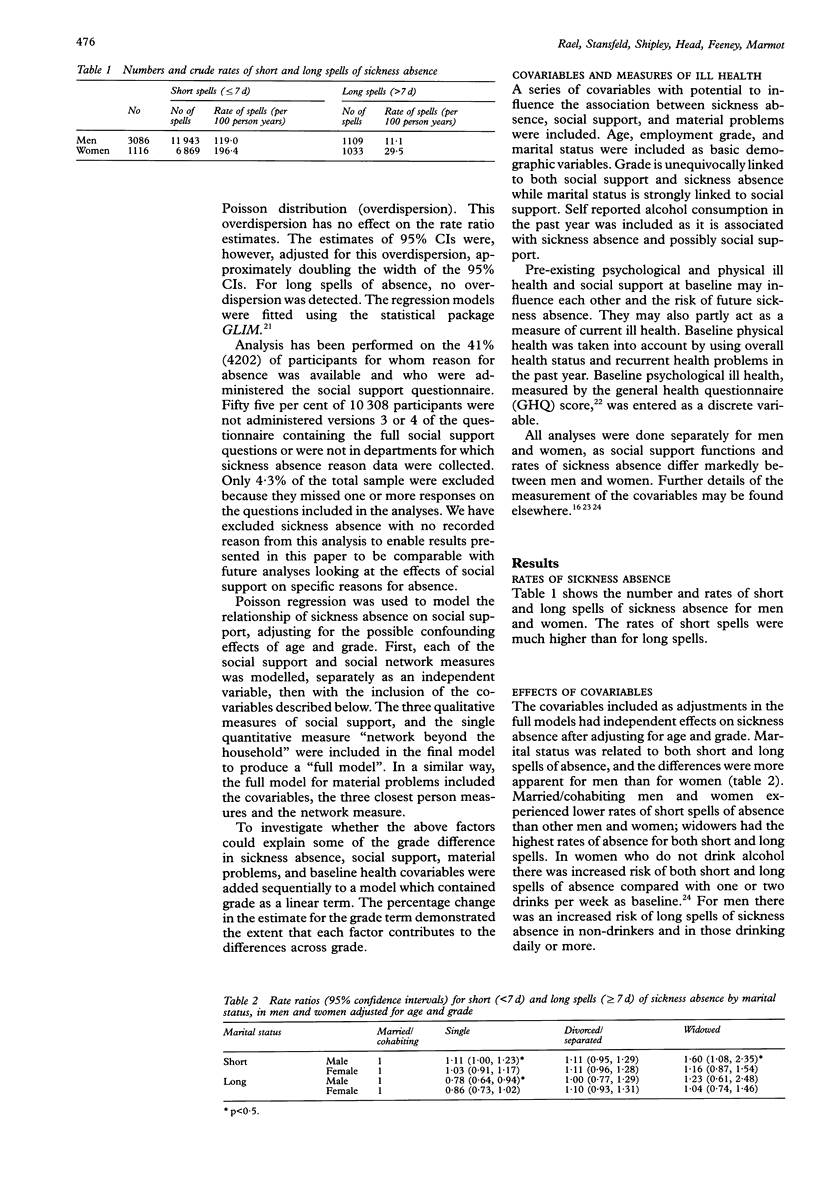

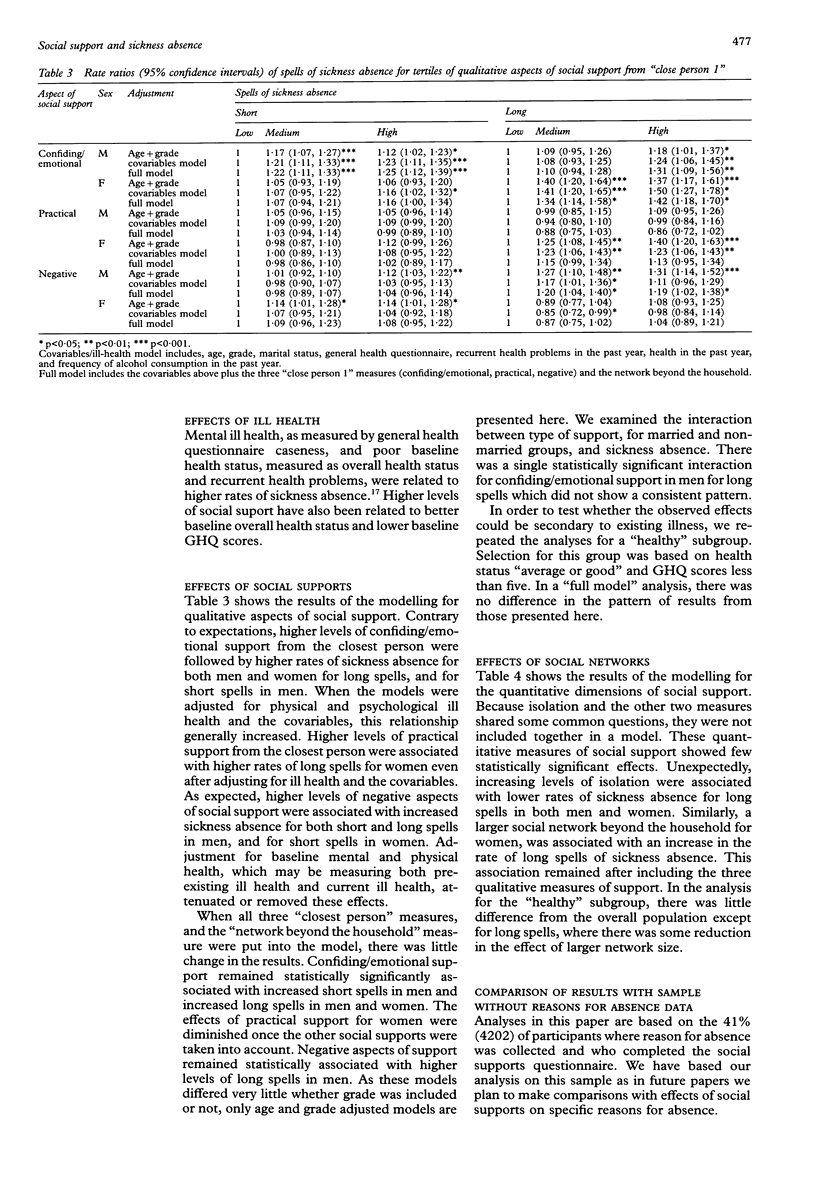

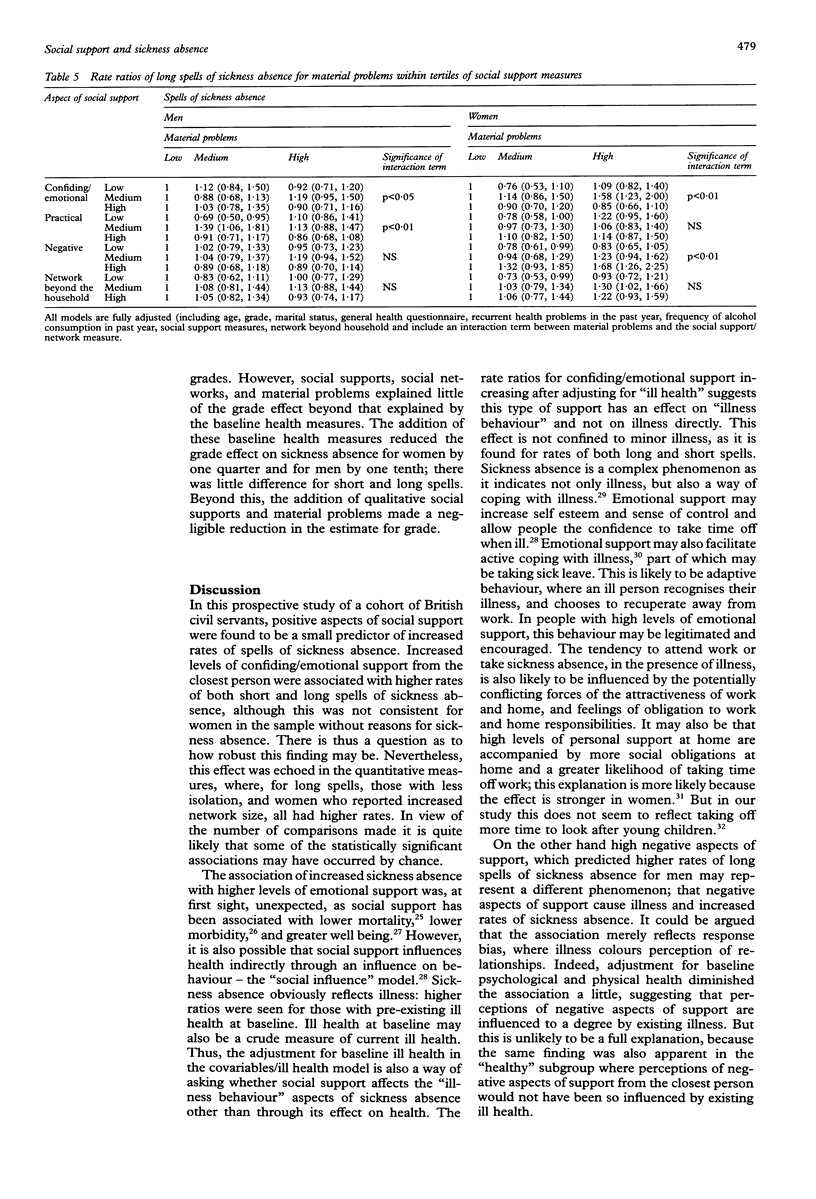

STUDY OBJECTIVE--To investigate the role of social supports, social networks, and chronic stressors: (i) as predictors of sickness absence; and (ii) as potential explanations for the socioeconomic gradient in sickness absence. DESIGN--A prospective cohort study (Whitehall II study) with sociodemographic factors, health and social support measured at baseline, and spells of sickness absence measured prospectively. SETTING--Twenty London based non-industrial departments of the British civil service. PARTICIPANTS--Participants were civil servants (n = 10,308), aged 35-55 years at baseline, of whom 67% (6895) were men and 33% (3413) were women. The overall response rate for Whitehall II was 73% (74% for men and 71% for women). The analysis is based on 41% of the sample who had data on reasons for sickness absence and were administered all social support questions. Only 4.3% of participants did not complete all necessary questions and were excluded. MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS--High levels of confiding/emotional support from the "closest person" predicted higher levels of both short and long spells of sickness absence. After adjusting for baseline physical and psychological health the effects were increased, suggesting that high levels of confiding/emotional support may encourage illness behaviour rather than generate illness. Social network measures showed a consistent but less striking pattern. Increased levels of negative aspects of social support resulted in higher rates of sickness absence. Material problems strongly predicted sickness absence, but the effect was diminished once adjustment for the covariables was made, suggesting that health status may be functioning as an intervening variable between chronic stressors and sickness absence. In addition, social support may buffer the effects of chronic stressors. Social support did not contribute to explaining the gradient in sickness absence by employment grade beyond that explained by the baseline covariables. CONCLUSIONS--Sickness absence from work is a complex phenomenon, combining illness and coping behaviours. High levels of confiding/emotional support, although not entirely consistent across samples, may either encourage people to stay at home when they are ill or may be accompanied by more social obligations at home prolonging sickness absence. Negative aspects of close relationships may jeopardize health and hence increase sickness absence.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andrews G., Tennant C., Hewson D., Schonell M. The relation of social factors to physical and psychiatric illness. Am J Epidemiol. 1978 Jul;108(1):27–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman L. F., Syme S. L. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: a nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. Am J Epidemiol. 1979 Feb;109(2):186–204. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D. G. Social support and mortality in an elderly community population. Am J Epidemiol. 1982 May;115(5):684–694. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broadhead W. E., Kaplan B. H., James S. A., Wagner E. H., Schoenbach V. J., Grimson R., Heyden S., Tibblin G., Gehlbach S. H. The epidemiologic evidence for a relationship between social support and health. Am J Epidemiol. 1983 May;117(5):521–537. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassel J. The contribution of the social environment to host resistance: the Fourth Wade Hampton Frost Lecture. Am J Epidemiol. 1976 Aug;104(2):107–123. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier A., Luce D., Blanc C., Goldberg M. Sickness absence at the French National Electric and Gas Company. Br J Ind Med. 1987 Feb;44(2):101–110. doi: 10.1136/oem.44.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988;7(3):269–297. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.7.3.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Wills T. A. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985 Sep;98(2):310–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlay-Jones R. A., Burvill P. W. Contrasting demographic patterns of minor psychiatric morbidity in general practice and the community. Psychol Med. 1978 Aug;8(3):455–466. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700016135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard J. H., Pope C. R. The quality of social roles as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Soc Sci Med. 1993 Feb;36(3):217–225. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(93)90005-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan C. J., Moos R. H. Personal and contextual determinants of coping strategies. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987 May;52(5):946–955. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.52.5.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson T. P. Mental health, social relations, and social selection: a longitudinal analysis. J Health Soc Behav. 1991 Dec;32(4):408–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kristensen T. S. Sickness absence and work strain among Danish slaughterhouse workers: an analysis of absence from work regarded as coping behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(1):15–27. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90122-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh J. P. Employee and job attributes as predictors of absenteeism in a national sample of workers: the importance of health and dangerous working conditions. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(2):127–137. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90173-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., North F., Feeney A., Head J. Alcohol consumption and sickness absence: from the Whitehall II study. Addiction. 1993 Mar;88(3):369–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Smith G. D., Stansfeld S., Patel C., North F., Head J., White I., Brunner E., Feeney A. Health inequalities among British civil servants: the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 1991 Jun 8;337(8754):1387–1393. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93068-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M., Feeney A., Shipley M., North F., Syme S. L. Sickness absence as a measure of health status and functioning: from the UK Whitehall II study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995 Apr;49(2):124–130. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North F., Syme S. L., Feeney A., Head J., Shipley M. J., Marmot M. G. Explaining socioeconomic differences in sickness absence: the Whitehall II Study. BMJ. 1993 Feb 6;306(6874):361–366. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6874.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth-Gomér K., Johnson J. V. Social network interaction and mortality. A six year follow-up study of a random sample of the Swedish population. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(10):949–957. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90145-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. I., Schooler C. The structure of coping. J Health Soc Behav. 1978 Mar;19(1):2–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbach V. J., Kaplan B. H., Fredman L., Kleinbaum D. G. Social ties and mortality in Evans County, Georgia. Am J Epidemiol. 1986 Apr;123(4):577–591. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld S. A., Smith G. D., Marmot M. Association between physical and psychological morbidity in the Whitehall II Study. J Psychosom Res. 1993 Apr;37(3):227–238. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(93)90031-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansfeld S., Marmot M. Deriving a survey measure of social support: the reliability and validity of the Close Persons Questionnaire. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Oct;35(8):1027–1035. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90242-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syme S. L. Social epidemiology and the work environment. Int J Health Serv. 1988;18(4):635–645. doi: 10.2190/LLYB-QCND-G5VB-JP9Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoits P. A. Conceptual, methodological, and theoretical problems in studying social support as a buffer against life stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1982 Jun;23(2):145–159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welin L., Tibblin G., Svärdsudd K., Tibblin B., Ander-Peciva S., Larsson B., Wilhelmsen L. Prospective study of social influences on mortality. The study of men born in 1913 and 1923. Lancet. 1985 Apr 20;1(8434):915–918. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91684-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]