Abstract

Introduction

The aim of the study was to describe the successful conservative management of diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma (DIR). Identification of RB1 pathogenic variant was done after cell-free DNA (cfDNA) analysis in aqueous humor.

Case presentation

Herein, we report 2 patients with unilateral, non-familial DIR with anterior and posterior involvement. Both patients underwent liquid biopsy for tumor cfDNA analysis in aqueous humor. Treatment consisted of a combination of systemic and intra-arterial chemotherapy, with consecutive intracameral and intravitreal injections of melphalan. One patient also required iodine-125 brachytherapy. In both cases, tumor cfDNA analysis revealed biallelic somatic alterations of the RB1 gene. These alterations were not found in germline DNA. Both patients retained their eyes and had a useful vision after a follow-up of 2 years.

Conclusion

In selected cases, conservative management of DIR is safe and effective. Tumor cfDNA analysis in aqueous humor is an effective technique to disclose RB1 somatic alterations that guide the germline molecular explorations and improve genetic counseling after conservative treatment.

Keywords: Retinoblastoma, Diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma, Conservative treatment, Intracamerular chemotherapy, Intravitreal chemotherapy, Liquid biopsy, Cell-free DNA, Retinoblastoma genetics, RB1 mutation

Introduction

Diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma (DIR) is a rare but insidious clinical presentation of retinoblastoma that accounts for about 2% of patients [1]. This form, often unilateral, affects older children and manifests with thickening and flat infiltration of the retina, tumor vitreous seeding and possibly tumor infiltration of the anterior chamber, cellular pseudo-hypopyon, and iris nodules. This misleading appearance may suggest uveitis and usually delays the diagnosis of retinoblastoma. The standard treatment for DIR has long been enucleation. However, in the era of local and regional therapies, conservative management can be offered [2]. In this article, we describe 2 patients affected by DIR and managed conservatively. Moreover, tumor cell-free DNA (cfDNA) was obtained via an anterior chamber paracentesis and disclosed RB1 somatic pathogenic variants in both cases, using our previously reported molecular method [3]. Briefly, cfDNA analysis was conducted as previously described [3] using a targeted next-generation sequencing panel on the whole coding sequence and exon-intron junctions of the RB1, MED4, MYCN, and TP53 genes, on specific single nucleotide polymorphisms identified as retinoblastoma biomarkers (selected by literature review), and microsatellites at the RB1 locus to detect loss of heterozygosity. The need for IRB approval is not required for this study in accordance with local and national guidelines due to the retrospective nature of this report.

Case Description

Case #1

An 8-year-old boy was referred to our tertiary center on January 2020 for suspicion of DIR of the right eye. The initial diagnosis was herpetic uveitis, unresponsive to corticosteroids and antiviral therapy. At presentation, the patient presented with a pseudo-hypopyon, cellular endothelial precipitates, and elevated intraocular pressure at 35 mm Hg (Fig. 1a). Visual acuity was 20/20. On fundus examination, a diffuse, white infiltration of the ciliary body on 360° and diffuse cellular vitreous seeding were noted without retinal involvement (Fig. 1b). The diagnosis of DIR was confirmed by cytology of the aqueous humor after an anterior chamber paracentesis. High-resolution orbital MRI did not find any intraocular tumor and ruled out extrascleral extension or optic nerve invasion. Anterior chamber optical coherence tomography Visante showed an infiltration of the angle by tumor cells (online suppl. Figure; for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000531233).

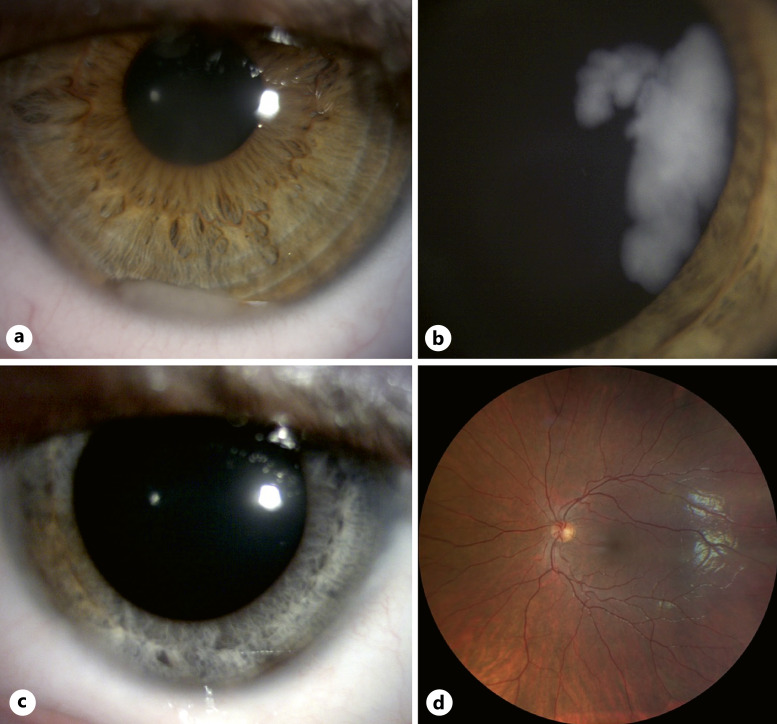

Fig. 1.

DIR with anterior involvement in an 8-year-old boy. a Anterior segment at diagnosis showing an inferior cellular pseudo-hypopyon. b Wide-field fundus color photograph at diagnosis showing diffuse tumoral infiltration of the peripheral retina and ciliary body. c Anterior segment photograph taken 2 years after the last treatment received showing diffuse iris discoloration. d Normal wide-field fundus photograph 2 years after the last treatment received.

Staging of this case was group E according to the International Retinoblastomaclassification (IRC) [4], and stage cT3b according to the 8th AJCC classification [5]. After discussion with the parents and our tumor board, an attempt at conservative management was decided. To reduce the risk of metastasis, the child received systemic intravenous chemotherapy according to our protocol for intermediate risk (due to anterior chamber infiltration) with 2 cycles of etoposide and carboplatin followed by 2 cycles of carboplatin [6]. In addition, he received local treatments consisting of weekly intracameral chemotherapy (ICC) (0.3 mg/mL; 0.06 mg) and intravitreal chemotherapy (IVitC) (0.3 mg/mL; 0.06 mg) with melphalan for a total of 8 injections, according to our previously reported protocol [7]. In order to control a residual tumor at the pars plana, two additional sessions of cryotherapy were performed, combined with two monthly intra-arterial injections of melphalan (5 mg).

The aqueous humor retrieved during the IVitC was used for tumor cfDNA analysis. Before injection, 0.1 mL of aqueous humor was collected via a paracentesis followed by a triple cryo of the needle tract, as already published [2, 7]. Briefly, cfDNA analysis was conducted as previously described [3] using a targeted next-generation sequencing panel on the whole coding sequence and exon-intron junctions of the RB1, MED4, MYCN, and TP53 genes, on specific single nucleotide polymorphisms identified as retinoblastoma biomarkers (selected by literature review), and microsatellites at the RB1 locus to detect loss of heterozygosity. A somatic large deletion of exons 3–27 and loss of heterozygosity of the RB1 gene were identified. These alterations were not found on germline DNA in two separate samples (peripheral blood and buccal mucosa).

At the most recent visit on July 2022, 2 years after treatment termination, no active tumor was visualized, either in the anterior or posterior segments. Best-corrected visual acuity of the left eye was 20/20. The only marked adverse effect of the treatments was sectorial iris atrophy with discoloration of the iris stroma (Fig. 1c). The fundus was normal (Fig. 1d) and the patient was alive without metastasis.

Case #2

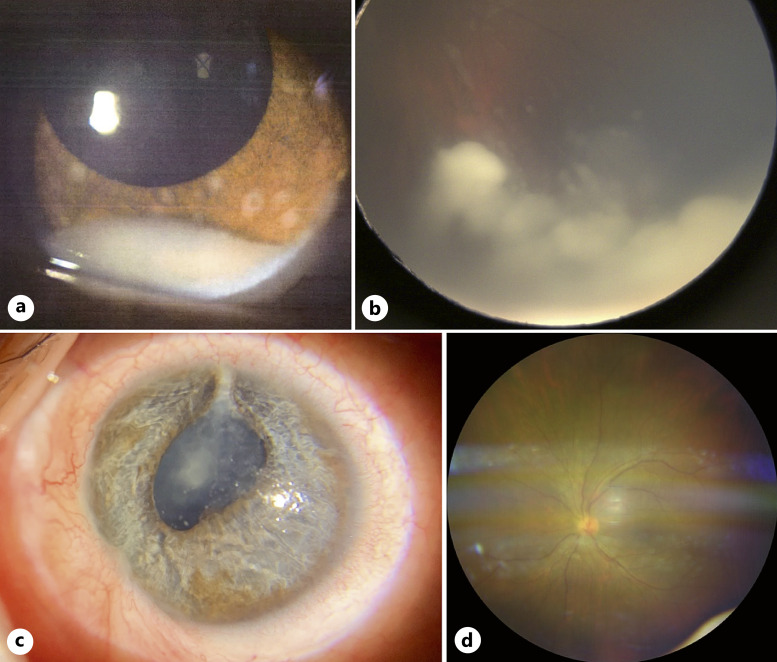

A 7-year-old girl was referred on July 2020 for suspicion of unilateral DIR of the left eye after unsuccessful treatment of presumed hypertensive uveitis. On examination, a cellular pseudo-hypopyon was noted, associated with iris nodules and elevated intraocular pressure at 33 mm Hg (Fig. 2a). On fundus examination, there was significant cellular infiltration of the vitreous as well as infiltration of the temporal peripheral retina and ciliary body (Fig. 2b). DIR was clinically suspected and confirmed by aqueous humor cytology. At diagnosis, 0.1 mL of aqueous humor was collected for cytology, followed by a triple cryo of the needle tract. High-resolution MRI did not objectify a calcified mass or extrascleral/optic nerve invasion. This eye was categorized as group E of the IIRC [4] and cT3b of the 8th AJCC staging system [5]. Because of the good visual potential of the affected eye, we decided in agreement with the parents to attempt conservative treatment. The treatment was started with intravenous chemotherapy according to our institutional protocol based on risk stratification [6], with 2 cycles of etoposide and carboplatin, followed by 2 cycles of carboplatin. Local treatment consisted of a combination of ICC (0.3 mg/mL; 0.06 mg) and IVitC of melphalan (0.3 mg/mL; 0.06 mg). A total of 9 ICC and 9 IVitC of melphalan were administered. Brachytherapy with iodine-125 plaque (45 Gy at 6 mm) was used to cure the remaining retinal infiltration in the inferior quadrant. Yet, she presented a relapse in the superior quadrant prompting to switch to intra-arterial injections of melphalan (5 mg, 4 monthly injections), allowing satisfactory tumor control. Finally, she received 2 intravenous injections of cyclophosphamide and vincristine in order to decrease the risk of metastatic relapse. RB1 gene analysis was performed on tumor cfDNA from 0.1 mL of aqueous humor obtained during the IVitC procedures. Two RB1 pathogenic variants were found: c.1498 + 1G>A, (49,20%; 2502X) on intron 16 and c.2359C>T, p.(Arg787*) (45,94%; 2684X) on exon 23. Both pathogenic variants were not found in two separate samples (peripheral blood and buccal mucosa), demonstrating that they were somatic. During follow-up, the main complications that developed were superior sectorial iris atrophy and a cataract (Fig. 2c), that was removed successfully by standard phacoemulsification procedure with intraocular lens implantation, 2 years after the last treatment received. At the last visit on December 2022, 26 months after the last treatment received, the patient was alive without metastasis, and left eye’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/100. No active tumor was visualized, neither in the anterior nor posterior segment (Fig. 2d).

Fig. 2.

DIR with anterior involvement in a 7-year-old girl. a Anterior segment at diagnosis showing a cellular pseudo-hypopyon. b Wide-field color fundus photograph showing diffuse infiltrating whitish masses in the peripheral inferior quadrant. c Anterior segment photograph taken 16 months after the last treatment received showing cataract, sectorial iris atrophy, and posterior synechiae, before cataract extraction and intraocular lens implantation procedure that was uneventful. d Normal wide-field color fundus photograph 20 months after the last treatment.

Discussion

The diffuse infiltrating presentation of retinoblastoma is rare and accounts for 2% of retinoblastoma diagnoses, according to a series of 34 cases by Shields et al. [1]. Those children, often older, present most frequently with unilateral involvement [8]. Among the 32 cases described by Shields et al., clinical findings in the anterior segment included tumor seeds on the corneal endothelium (24%), cornea stromal edema (9%), pseudo-hypopyon (32%), hyphema (9%), iris neovascularization (50%), and iris tumor nodules (18%). Posterior segment findings included extensive vitreous tumor seeds (91%), vitreous hemorrhage (24%), and diffuse retinal infiltration in all cases [1]. According to the authors, these cases were classified as “high-grade retinoblastoma” and enucleation was recommended in most instances. However, in the current era of expanded conservative therapeutic armamentarium, Stathopoulos et al. [2] showed recently that globe salvage could be achieved in 1 out of 3 patients for whom conservative treatment combining ICC was attempted. Involvement of the anterior segment in the 2 cases reported here, classifies their disease as group E of the IIRC and cT3b of the 8th AJCC staging. Therefore, in order to drastically reduce the risk of metastatic relapse, systemic chemotherapy consisting of 2 cycles of intravenous etoposide + carboplatin followed by 2 additional cycles of carboplatin, was associated with local treatments. The combination of ICC and IVT was well tolerated. Complications were limited to iris atrophy in the first patient and cataract formation in the second patient, who had also been treated with iodine-125 plaque brachytherapy. After a 2-year follow-up, both patients presented at the most recent visit in complete remission without local (ocular or orbital) nor distant relapse. Visual acuity was preserved at 20/20 in case #1 but limited to 20/100 in case #2. Close follow-up was maintained because of a single case with late relapse reported by Stathopoulos et al. [2]. Tumor cfDNA analysis in aqueous humor allowed in these 2 cases to identify the 2 somatic “hits” and to rule out any germline genetic predisposition, which gives important information for genetic counseling. Although retinoblastoma developing at older ages is often non-hereditary, diffuse retinoblastoma has been exceptionally reported as hereditary [9–11]. Regarding our 2 cases, the absence of the RB1 germline pathogenic variant confirmed that the cases were not predisposed to secondary primary tumors such as sarcoma and cutaneous melanoma, and their siblings are released from a follow-up by iterative ocular fundus that is performed under general anesthesia in young children. In both cases, no amplification of MYCN was identified. A gene panel including RB1 and MYCN was analyzed by enrichment with SureSelect XT HS2 (Agilent) capture probes and sequencing on NextSeq 500 (Illumina), as previously described [3]. Briefly, the in-house bioinformatics pipeline included an alignment on the hg19 human genome with BWA, variant calling with VarScan2 and annotation with ANNOVAR for point mutations, and a count matrix (bed-tools) of depth of coverage for copy number variants.

Interestingly, Kletke et al. [12] recently reported the case of a 13-year-old girl with anterior retinoblastoma, who also managed conservatively with a 28-month follow-up without relapse. The initial diagnosis was also hypertensive uveitis, yet cytology evaluation was unconclusive, but retinoblastoma could be ascertained by tumor cfDNA analysis from aqueous humor.

Conclusion

Conservative management of DIR with anterior chamber involvement, based on combined systemic and local chemotherapy – with intracameral and intravitreal injections – is a therapeutic option that proved safe and efficient in these 2 cases. Analysis of tumor cfDNA from aqueous humor also proved a robust method that may be used as diagnostic tool in case of nonconclusive cytology and allowed to identify RB1 somatic alterations in the context of eye preservation. It gives important information for genetic counseling: the absence of predisposition to secondary primary tumors for the cases and the release of ophthalmologic surveillance for the siblings.

Statement of Ethics

Ethical approval is not required for this study in accordance with local or national guidelines due to the retrospective nature of this report. Institutional written informed consent was obtained from the parent/legal guardian of the 2 patients for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors declare that no funding was received for this study.

Author Contributions

Nathalie Cassoux, Alexandre Matet, Denis Malaise, Jessica Le Gall, Lisa Golmard, Livia Lumbroso, Liesbeth Cardoen, Paul Freneaux, Francois Doz, and Yassine Bouchoucha claim to have contributed to the conception or design of the work; or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, draft the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content; give their final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Funding Statement

The authors declare that no funding was received for this study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Shields CL, Ghassemi F, Tuncer S, Thangappan A, Shields JA. Clinical spectrum of diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma in 34 consecutive eyes. Ophthalmology. 2008 Dec;115(12):2253–8. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stathopoulos C, Moulin A, Gaillard MC, Beck-Popovic M, Puccinelli F, Munier FL. Conservative treatment of diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma: optical coherence tomography-assisted diagnosis and follow-up in three consecutive cases. Br J Ophthalmol. 2019 Jun;103(6):826–30. 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Le Gall J, Dehainault C, Benoist C, Matet A, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Aerts I, et al. Highly sensitive detection method of retinoblastoma genetic predisposition and biomarkers. J Mol Diagn. 2021;23(12):1714–21. 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2021.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Shields CL, Mashayekhi A, Au AK, Czyz C, Leahey A, Meadows AT, et al. The International Classification of Retinoblastoma predicts chemoreduction success. Ophthalmology. 2006 Dec;113(12):2276–80. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Amin MB, Edge SB; American Joint Committee on Cancer . AJCC cancer staging manual. [cited 2019 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319406176. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6. Matet A, Gauthier A, Cardoen L, Golmard L, Malaise D, Biewald E, et al. Advanced intraocular unilateral retinoblastoma: non-conservative management. ERN PaedCan European Standard Clinical Practice Guidelines; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cassoux N, Aerts I, Lumbroso-Le Rouic L, Freneaux P, Desjardins L. Eye salvage with combination of intravitreal and intracameral melphalan injection for recurrent retinoblastoma with anterior chamber involvement: report of a case. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2017;3(2):129–32. 10.1159/000452305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Traine PG, Schedler KJ, Rodrigues EB. Clinical presentation and genetic paradigm of diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma: a review. Ocul Oncol Pathol. 2016 Apr;2(3):128–32. 10.1159/000441528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Crosby MB, Hubbard GB, Gallie BL, Grossniklaus HE. Anterior diffuse retinoblastoma: mutational analysis and immunofluorescence staining. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009 Aug;133(8):1215–8. 10.5858/133.8.1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kao LY. Diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma: an inherited case. Retina. 2000;20(2):217–9. 10.1097/00006982-200002000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schedler KJE, Traine PG, Lohmann DR, Haritoglou C, Metz KA, Rodrigues EB. Hereditary diffuse infiltrating retinoblastoma. Ophthalmic Genet. 2016 Jan;37(1):95–7. 10.3109/13816810.2014.921315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kletke SN, Soliman S, Racher H, Mallipatna A, Shaikh F, Mireskandari K, et al. Atypical anterior retinoblastoma: diagnosis by aqueous humor cell-free DNA analysis. Ophthalmic Genet. 2022 Nov;43(6):862–5. 10.1080/13816810.2022.2141800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.