Abstract

Introduction

Atezolizumab + bevacizumab showed survival benefit in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) versus sorafenib in the Phase III IMbrave150 study. This exploratory analysis examined the prognostic impact of a baseline albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score.

Methods

Patients with treatment-naïve unresectable HCC, ≥1 measurable untreated lesion, and Child-Pugh class A liver function were randomized 2:1 to receive atezolizumab 1,200 mg + bevacizumab 15 mg/kg every 3 weeks or sorafenib 400 mg twice daily. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were assessed in the intention-to-treat population by ALBI/modified (m)ALBI grade. Time to deterioration (TTD; defined as time to 0.5-point increase from the baseline ALBI score over 2 visits or death) of liver function and safety were investigated.

Results

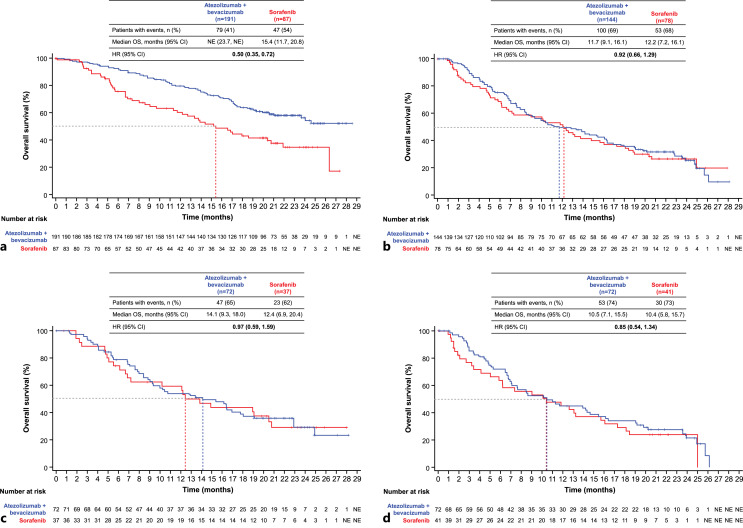

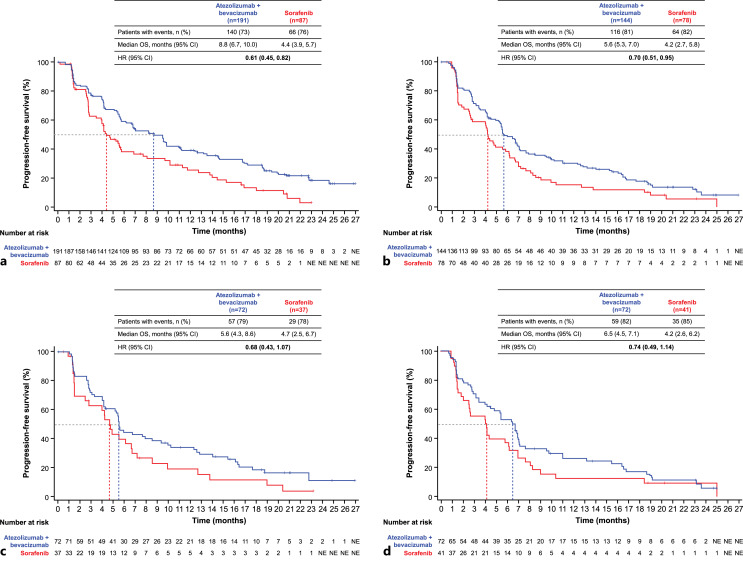

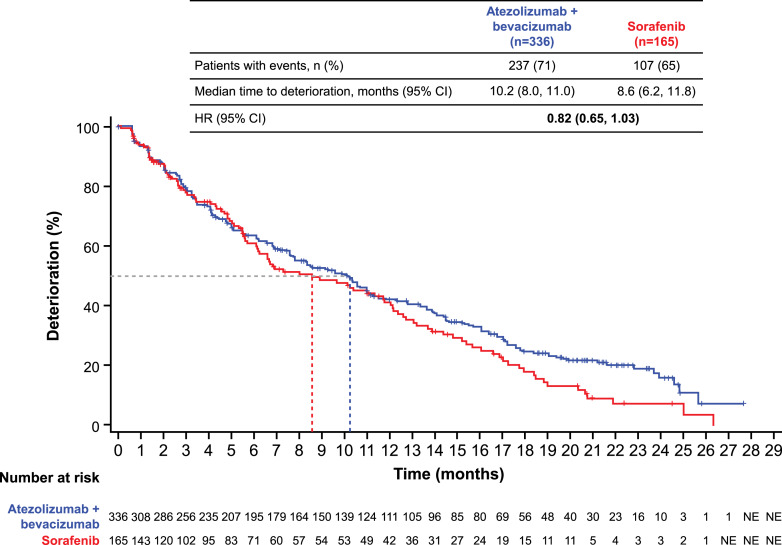

Of 501 enrolled patients, 336 were randomized to receive atezolizumab + bevacizumab (ALBI grade [G] 1: n = 191; G2: n = 144 [mALBI G2a: n = 72, G2b: n = 72]; missing ALBI grade: n = 1) and 165 to sorafenib (ALBI G1: n = 87; G2: n = 78 [mALBI G2a: n = 37; G2b: n = 41]). Median follow-up was 15.6 months. OS and PFS improved with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with ALBI G1 (OS HR: 0.50 [95% CI: 0.35, 0.72]; PFS HR: 0.61 [95% CI: 0.45, 0.82]). In patients with ALBI G2 or mALBI G2a or G2b, PFS was numerically longer with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib, but no OS benefit was seen. Median TTD in the intention-to-treat population was 10.2 months (95% CI: 8.0, 11.0) with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 8.6 months (95% CI: 6.2, 11.8) with sorafenib (HR: 0.82 [95% CI: 0.65, 1.03]). Safety profiles of atezolizumab and bevacizumab were consistent with previous analyses, regardless of ALBI grade.

Conclusion

ALBI grade appeared to be prognostic for outcomes with both atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib treatment in patients with HCC. Atezolizumab + bevacizumab preserved liver function for a numerically longer duration than sorafenib.

Keywords: Albumin-bilirubin grade, Atezolizumab, Bevacizumab, Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma

Introduction

Liver cancer is one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality worldwide, with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) comprising 75–85% of liver cancer cases [1]. In untreated patients, the prognosis for patients with advanced HCC is poor, with a median overall survival (OS) of 9 months [2]. Sorafenib was the historic standard of care for first-line (1L) treatment of advanced unresectable HCC [3] until the emergence of treatment options including lenvatinib and the combination of atezolizumab (an anti-programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) monoclonal antibody) and bevacizumab (an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor monoclonal antibody) (atezolizumab + bevacizumab) [4, 5].

In the primary analysis of the Phase III IMbrave150 study (NCT03434379), statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvements were observed with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib in both co-primary endpoints (OS and progression-free survival [PFS]) [5]. Based on these data, atezolizumab + bevacizumab has been approved globally in >85 countries for the treatment of patients with unresectable HCC who have not received prior systemic therapy [6, 7]. Additionally, the treatment benefit with atezolizumab + bevacizumab over sorafenib was maintained with 12 months of additional follow-up (median follow-up duration, 15.6 months). Median OS was 19.2 months with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 13.4 months with sorafenib [8].

Liver function of patients at baseline is known to affect HCC prognosis [9, 10]. Methods to assess liver function include the Child-Pugh (CP) class and the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) grade. The ALBI grade is an evidence-based method of assessing liver function that relies only on serum bilirubin and albumin levels and has demonstrated performance similar to or better than the CP class [11]. In addition, prognostic scoring with the ALBI grade is more objective than with the CP class, which includes subjective assessment of factors such as the severity of ascites and encephalopathy [12]. The ALBI grade also provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage and CP class [13, 14] and has been shown to perform as well as CP class when integrated into Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer staging [15].

However, the major limitation of the ALBI grading system is that ALBI grade 2 includes a large proportion (≈60%) of patients who have a wide range of hepatic reserve function. To ensure a more homogenous population within each grade, a modified ALBI (mALBI) grade that divides the ALBI grade into 4 levels, instead of 3, was proposed in 2017 based on the results of a nationwide survey of 46,681 patients conducted by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan [16]. Patients with ALBI grade 2 were separated into two subgrades (mALBI grades 2a and 2b), enabling a more precise classification of hepatic functional reserve [17, 18]. mALBI grades 2a and 2b were separated using a cutoff value of −2.27 for the ALBI score based on the indocyanine green retention test. The mALBI grading system showed better prognostic and predictive value across various treatment options compared with ALBI grading [17, 18].

Multiple recent studies have validated the ability of the ALBI grade to predict the prognosis of patients with HCC following initial resection [19–21]. Baseline ALBI grade was also shown to be prognostic in patients with advanced HCC who received 1L sorafenib [22, 23] or lenvatinib [24]. Furthermore, ALBI grade at sorafenib discontinuation could identify a subset of patients with prolonged hepatic reserve stability, which may allow for improved patient selection for second-line therapies [25].

The impact of baseline ALBI/mALBI grade on outcomes in patients with unresectable HCC receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab has yet to be established. Here, we report an exploratory analysis of the IMbrave150 study that examined outcomes by mALBI grade at baseline. The change in ALBI score during the course of treatment was also investigated.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

This post hoc analysis explored the impact of baseline ALBI/mALBI grade on outcomes of patients enrolled in the global, multicenter, open-label, randomized Phase III IMbrave150 study (ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT03434379). Details of study design, eligibility criteria, and outcome measures were previously reported [5, 8] and are summarized in online supplementary Figure S1 (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000529996). Briefly, eligible patients were aged 18 years or older with locally advanced or metastatic and/or unresectable HCC, had an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0 or 1, CP class A liver function, and had not previously received systemic therapy for liver cancer [5]. Key exclusion criteria included a history of autoimmune disease, coinfection with hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus (HCV), and untreated or incompletely treated esophageal or gastric varices with bleeding or high risk of bleeding.

Patients were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive either 1,200 mg of atezolizumab plus 15 mg/kg of bevacizumab intravenously every 3 weeks or 400 mg of sorafenib orally twice daily. Treatment was given until loss of clinical benefit as determined by the investigator after an integrated assessment of radiographic and biochemical data and clinical status (e.g., symptomatic deterioration such as pain secondary to disease) or unacceptable toxicity [5]. If patients transiently or permanently discontinued either atezolizumab or bevacizumab because of an adverse event (AE), single-agent therapy was allowed if the patient was experiencing clinical benefit. Dose modifications were permitted in the sorafenib arm but not in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm.

Tumors were assessed by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging at baseline, every 6 weeks until week 54, and then every 9 weeks thereafter. Safety was continuously evaluated by recording vital signs and clinical laboratory test results and assessing the incidence and severity of AEs according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.0 [5].

Outcomes

The co-primary endpoints were OS (defined as time from randomization to death from any cause) and PFS (defined as time from randomization to disease progression per independent review facility-assessed Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (IRF-RECIST) version 1.1 or death from any cause, whichever occurred first) [5]. Secondary efficacy endpoints included objective response rate (ORR, defined as the percentage of patients with a confirmed complete or partial response) per IRF-RECIST 1.1; time to deterioration in liver function (TTD, defined as the time to a 0.5-point increase from baseline in ALBI score maintained over 2 visits, or death); and change in mean ALBI scores from baseline. Results from the primary and 12-month updated analyses of these efficacy endpoints have been reported previously [5, 8].

Statistical Analysis

Details of the statistical methods used in the IMbrave150 study were previously described [5, 8]. Briefly, efficacy was assessed in the intention-to-treat population, which included all patients who were randomly assigned to treatment, and in subgroups that were based on baseline demographics and disease characteristics. Median OS and PFS, together with 95% CIs, for each treatment arm were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method. The Cox proportional-hazards model was used to estimate hazard ratios, with corresponding 95% CI. All hazard ratios are unstratified. The Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test was used to compare both treatment arms in terms of the confirmed response rates among patients with measurable disease at baseline. Patients who had received ≥1 dose of study treatment were included in the safety-evaluable population.

Albumin and bilirubin levels were measured at each visit until the time of deterioration (defined as a 0.5-point increase from baseline in ALBI score maintained over 2 visits or death). ALBI scores were determined by the following calculation: (log10 bilirubin [in µmol/L] × 0.66) + (albumin (in g/L) × −0.085). ALBI grades 1, 2, and 3 are defined as ALBI scores of ≤ −2.60, > −2.60 to ≤ −1.39, and >−1.39, respectively [11]. mALBI grades are defined in the same manner as ALBI grades, except that ALBI grade 2 is further divided into mALBI grade 2a (defined as an ALBI score of > −2.60 to ≤ −2.27) and mALBI grade 2b (defined as an ALBI score of > −2.27 to ≤ −1.39) [11, 17]. Efficacy was assessed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and safety in the safety-evaluable population by mALBI grade.

Results

Patients

In IMbrave150, 501 patients were enrolled, randomized into the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm (336 patients) or the sorafenib arm (165 patients), and included in the ITT population (online suppl. Fig. S2). Of these, 500 patients had available baseline ALBI data; 1 patient in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm had missing baseline ALBI data and was excluded from this analysis. Among patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab, 191 (57%) were classified as ALBI grade 1, and 144 (43%) were ALBI grade 2 (mALBI grade 2a: 72 [21%]; mALBI grade 2b: 72 [21%]). For patients receiving sorafenib, 87 (53%) were ALBI grade 1, and 78 (47%) were ALBI grade 2 (mALBI grade 2a: 37 [22%]; mALBI grade 2b: 41 [25%]). None of the patients in either arm were grade 3 at baseline. In both arms, a greater percentage of patients with ALBI grade 2 (mALBI grade 2a or 2b) were from the rest of the world (including Japan) than from Asia (excluding Japan) and had varices (Table 1). Additionally, a greater percentage of patients with ALBI grade 1 had HCC caused by the hepatitis B virus, an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0, and CP class A5 compared with patients with ALBI grade 2 in both arms.

Table 1.

Patient demographics according to baseline ALBI/mALBI grade

| ALBI grade 1 | ALBI grade 2 | mALBI grade 2a | mALBI grade 2b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atezolizumab + bevacizumaba (n = 191) | sorafenib (n = 87) | atezolizumab + bevacizumaba (n = 144) | sorafenib (n = 78) | atezolizumab + bevacizumaba (n = 72) | sorafenib (n = 37) | atezolizumab + bevacizumaba (n = 72) | sorafenib (n = 41) | |

| Age, median (range), years | 62 (27–88) | 64 (33–81) | 64.5 (26–87) | 67.5 (37–87) | 64 (35–87) | 68 (37–87) | 66 (26–86) | 67 (45–84) |

| Male, n (%) | 156 (82) | 75 (86) | 120 (83) | 62 (79) | 60 (83) | 29 (78) | 60 (83) | 33 (80) |

| Geographic region,bn (%) | ||||||||

| Asia, excluding Japan | 97 (51) | 45 (52) | 36 (25) | 23 (29) | 22 (31) | 8 (22) | 14 (19) | 15 (37) |

| Rest of world, including Japanc | 94 (49) | 42 (48) | 108 (75) | 55 (71) | 50 (69) | 29 (78) | 58 (81) | 26 (63) |

| ECOG PS, n (%)b | ||||||||

| 0 | 130 (68) | 58 (67) | 79 (55) | 45 (58) | 42 (58) | 24 (65) | 37 (51) | 21 (51) |

| 1 | 61 (32) | 29 (33) | 65 (45) | 33 (42) | 30 (42) | 13 (35) | 35 (49) | 20 (49) |

| CP class, n (%) | ||||||||

| A5 | 165 (87) | 74 (85) | 74 (51) | 47 (60) | 51 (71) | 31 (84) | 23 (32) | 16 (39) |

| A6 | 24 (13)d | 13 (15) | 69 (48) | 31 (40) | 21 (29) | 6 (16) | 48 (67)e | 25 (61) |

| BCLC stage, n (%) | ||||||||

| A | 6 (3) | 4 (5) | 2 (1) | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 0 |

| B | 27 (14) | 11 (13) | 24 (17) | 14 (18) | 11 (15) | 5 (14) | 13 (18) | 9 (22) |

| C | 158 (83) | 72 (83) | 118 (82) | 62 (79) | 61 (85) | 30 (81) | 57 (79) | 32 (78) |

| AFP ≥400 ng/mL, n (%)b | 67 (35) | 32 (37) | 59 (41) | 29 (37) | 28 (39) | 10 (27) | 31 (43) | 19 (46) |

| Presence of EHS, MVI, or both, n (%)b | 149 (78) | 69 (79) | 108 (75) | 51 (65) | 58 (81) | 24 (65) | 50 (69) | 27 (66) |

| EHS | 128 (67) | 52 (60) | 83 (58) | 41 (53) | 48 (67) | 21 (57) | 35 (49) | 20 (49) |

| MVI | 65 (34) | 41 (47) | 63 (44) | 30 (38) | 32 (44) | 11 (30) | 31 (43) | 19 (46) |

| Varices, n (%) | ||||||||

| Present | 35 (18) | 19 (22) | 54 (38) | 24 (31) | 21 (29) | 10 (27) | 33 (46) | 14 (34) |

| Treated | 12 (6) | 7 (8) | 24 (17) | 16 (21) | 10 (14) | 4 (11) | 14 (19) | 12 (29) |

| HCC etiology, n (%)f | ||||||||

| HBV | 109 (57) | 48 (55) | 55 (38) | 28 (36) | 29 (40) | 15 (41) | 26 (36) | 13 (32) |

| HCV | 41 (21) | 14 (16) | 31 (22) | 22 (28) | 15 (21) | 5 (14) | 16 (22) | 17 (41) |

| Nonviral | 41 (21) | 25 (29) | 58 (40) | 28 (36) | 28 (39) | 17 (46) | 30 (42) | 11 (27) |

| Prior local therapy for HCC, n (%) | 99 (52) | 49 (56) | 62 (43) | 36 (46) | 32 (44) | 20 (54) | 30 (42) | 16 (39) |

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer stage; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; EHS, extrahepatic spread; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; mALBI, modified ALBI; MVI, macrovascular invasion.

a1 patient in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm in the intention-to-treat population had missing ALBI data.

bPer electronic case report form, not interactive voice/web response system.

cRest of the world includes the USA, Australia, and Japan.

dPrecise numeric scores for 2 patients in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm who were in class A on the CP scale were not available.

eData are not included for 1 patient in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm whose classification was B7.

fFor patients whose cause of HCC was multifactorial as assessed by the investigator, the viral cause was prioritized over nonviral causes to define the primary etiology of the patient.

In the ALBI grade 1 subgroup, macrovascular invasion (MVI) occurred in fewer patients in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm (34%) than in the sorafenib arm (47%). In the mALBI grade 2a subgroup, there were also imbalances between treatment arms in patients who were CP class A5 (71% with atezolizumab + bevacizumab vs. 84% with sorafenib) or A6 (29 vs. 16%); had alpha-fetoprotein levels ≥400 ng/mL (39 vs. 27%); had extrahepatic spread, MVI, or both (81 vs. 65%); and presence of MVI (44 vs. 30%). Among patients with mALBI grade 2b, a greater percentage in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm was from the rest of the world (81 vs. 63% in the sorafenib arm), had varices present at baseline (46 vs. 34%), and had nonviral HCC etiology (42 vs. 27%).

Efficacy

At the data cutoff of August 31, 2020, the median follow-up duration was 15.6 months overall (interquartile range (IQR), 6.4–21.3), 17.6 months in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm (IQR, 8.0–21.9), and 10.4 months in the sorafenib arm (IQR, 4.7–20.3). Median OS in patients with ALBI grade 1 was not estimable (NE; 95% CI: 23.7, NE) with atezolizumab + bevacizumab compared with 15.4 months (95% CI: 11.7, 20.8) with sorafenib (HR: 0.50; 95% CI: 0.35, 0.72) (Fig. 1). In patients with ALBI grade 2, median OS was 11.7 months (95% CI: 9.1, 16.1) with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 12.2 months (95% CI: 7.2, 16.1) with sorafenib (HR: 0.92; 95% CI: 0.66, 1.29). In the mALBI grade 2a subgroup, median OS was 14.1 months (95% CI: 9.3, 18.0) with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 12.4 months (95% CI: 6.9, 20.4) with sorafenib (HR: 0.97; 95% CI: 0.59, 1.59). Patients with mALBI grade 2b who received atezolizumab + bevacizumab had a median OS of 10.5 months (95% CI: 7.1, 15.5) compared with 10.4 months (95% CI: 5.8, 15.7) in those who received sorafenib (HR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.54, 1.34).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of OS by ALBI/mALBI grade. Kaplan-Meier estimates of OS in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib arms by ALBI/mALBI grade: ALBI grade 1 (a), ALBI grade 2 (b), mALBI grade 2a (c), and mALBI grade 2b (d). ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; mALBI, modified ALBI; NE, not estimable; OS, overall survival.

Median PFS per IRF-RECIST 1.1 in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup was 8.8 months (95% CI: 6.7, 10.0) in patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 4.4 months (95% CI: 3.9, 5.7) in those receiving sorafenib (HR: 0.61; 95% CI: 0.45, 0.82) (Fig. 2). In the ALBI grade 2 subgroup, median PFS was 5.6 months (95% CI, 5.3, 7.0) with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 4.2 months (95% CI: 2.7, 5.8) with sorafenib (HR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.51, 0.95). Median PFS in patients with mALBI grade 2a was 5.6 months (95% CI: 4.3, 8.6) with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 4.7 months (95% CI: 2.5, 6.7) with sorafenib (HR: 0.68; 95% CI: 0.43, 1.07). In the mALBI grade 2b subgroup, median PFS was 6.5 months (95% CI: 4.5, 7.1) in patients who received atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus 4.2 months (95% CI: 2.6, 6.2) in those who received sorafenib (HR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.49, 1.14).

Fig. 2.

Analysis of PFS by ALBI/mALBI grade. Kaplan-Meier estimates of PFS per IRF-RECIST 1.1 in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib arms by ALBI/mALBI grade: ALBI grade 1 (a), ALBI grade 2 (b), mALBI grade 2a (c), and mALBI grade 2b (d). ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; IRF-RECIST, independent review facility-assessed Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours; NE, not estimable; mALBI, modified ALBI; PFS, progression-free survival.

In patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab, confirmed ORR per IRF-RECIST 1.1 was 32% (n = 58) in those with ALBI grade 1 and 27% (n = 39) in those with ALBI grade 2 (30% (n = 21) and 25% (n = 18) in those with mALBI grades 2a and 2b, respectively) (Table 2). Confirmed ORR per IRF-RECIST 1.1 in patients receiving sorafenib was 6% (n = 5) for those with ALBI grade 1 and 17% (n = 13) for those with ALBI grade 2 (11% [n = 4] for mALBI grade 2a and 23% [n = 9] for mALBI grade 2b). The difference in ORR between the atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib arms was 26% (95% CI: 16, 35) in patients with ALBI grade 1 and 10% (95% CI: −2, 23) in those with grade 2 (mALBI grade 2a, 19% [95% CI: 2, 36]; mALBI grade 2b, 3% [95% CI: −16, 21]).

Table 2.

Clinical response as per IRF-RECIST 1.1 by ALBI/mALBI grade

| ALBI grade 1 | ALBI grade 2 | mALBI grade 2a | mALBI grade 2b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 183) | sorafenib (n = 83) | atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 142) | sorafenib (n = 76) | atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 70) | sorafenib (n = 36) | atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 72) | sorafenib (n = 40) | |

| Confirmed ORR, n (%) (95% CI), %a |

58 (32) (25, 39) |

5 (6) (2, 14) |

39 (27) (20, 36) |

13 (17) (9, 27) |

21 (30) (20, 42) |

4 (11) (3, 26) |

18 (25) (16, 37) |

9 (23) (11, 38) |

| CR, n (%) | 18 (10) | 0 | 7 (5) | 1 (1) | 4 (6) | 0 | 3 (4) | 1 (3) |

| PR, n (%) | 40 (22) | 5 (6) | 32 (23) | 12 (16) | 17 (24) | 4 (11) | 15 (21) | 8 (20) |

| SD, n (%) | 85 (46) | 44 (53) | 59 (42) | 25 (33) | 30 (43) | 15 (42) | 29 (40) | 10 (25) |

| DCR, n (%) | 143 (78) | 49 (59) | 98 (69) | 38 (50) | 51 (73) | 19 (53) | 47 (65) | 19 (48) |

| PD, n (%) | 34 (19) | 21 (25) | 29 (20) | 19 (25) | 15 (21) | 10 (28) | 14 (19) | 9 (23) |

| Not evaluable, n (%) | 3 (2) | 5 (6) | 5 (4) | 9 (12) | 1 (1) | 4 (11) | 4 (6) | 5 (13) |

| Missing, n (%) | 3 (2) | 8 (10) | 10 (7) | 10 (13) | 3 (4) | 3 (8) | 7 (10) | 7 (18) |

ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; CI, confidence interval; CR, complete response; DCR, disease control rate; IRF-RECIST, independent review facility-assessed Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours; mALBI, modified ALBI; ORR, objective response rate; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease.

aOnly patients with measurable disease at baseline were included in the analysis of ORR.

CR was achieved in 18 (10%) and 7 (5%) patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab with ALBI grades 1 and 2, respectively. In the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm, 4 patients (6%) with mALBI grade 2a and 3 patients (4%) with mALBI grade 2b achieved CR. Among those receiving sorafenib, CR was achieved in 0 patients with ALBI grade 1 and 1 patient (1%) with ALBI grade 2 (0 patients with mALBI grade 2a and 1 patient (3%) with mALBI grade 2b).

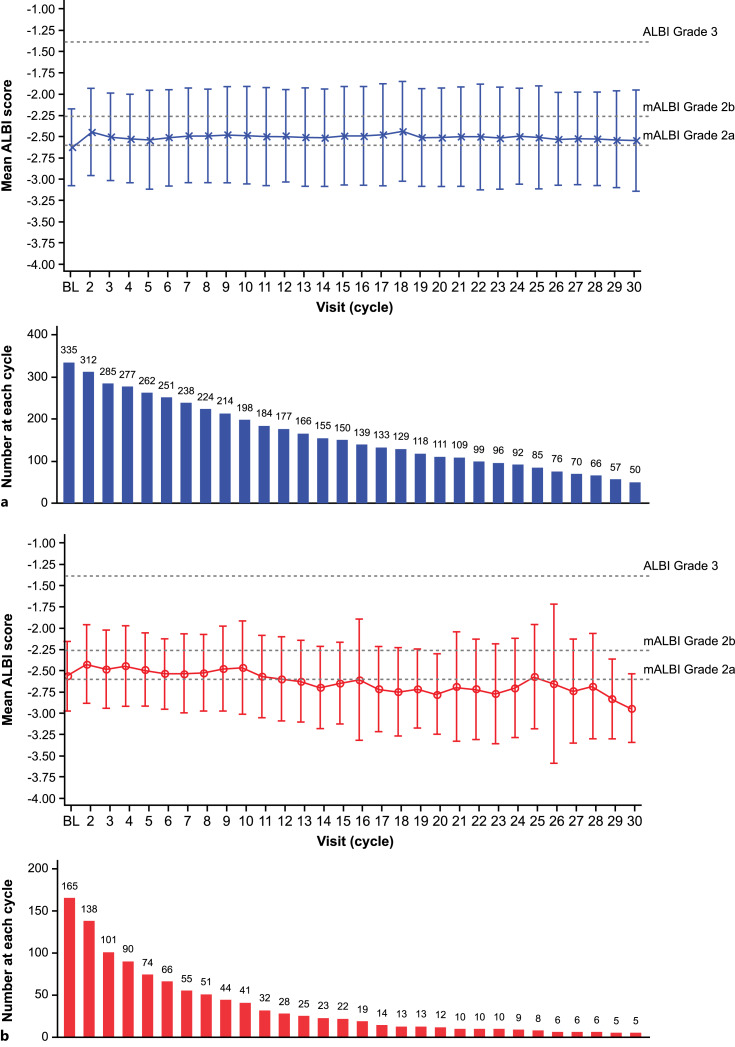

The median ALBI scores were −2.68 (range, −3.8 to −1.5) in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm (n = 336) and −2.64 (range, −3.4 to −1.4) in the sorafenib arm (n = 165) at baseline. The mean ALBI score was generally maintained at ALBI grade 2a from baseline to the last available ALBI measurement in both the atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib arms (Fig. 3). The median ALBI score at progression was −2.42 (range, −3.5 to −0.2) among patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab and −2.46 (range, −3.5 to −0.6) among those receiving sorafenib. The median TTD was 10.2 months (95% CI: 8.0, 11.0) in those receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab compared with 8.6 months (95% CI: 6.2, 11.8) in those receiving sorafenib (HR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.65, 1.03) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Change in mean ALBI score from baseline in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab (a) and sorafenib (b) arms. Error bars represent standard deviation. Dashed lines represent ALBI score cutoffs for each ALBI grade/mALBI grade. Mean ALBI score at disease progression was −2.32 (SD, 0.64) in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm and −2.34 (SD, 0.59) in the sorafenib arm. ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; BL, baseline; SD, standard deviation.

Fig. 4.

Time to deterioration in liver function in the ITT population. CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; ITT, intention to treat, NE, not estimable.

Safety

The safety-evaluable population included 329 patients in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm and 156 patients in the sorafenib arm. The median duration of atezolizumab treatment was 10.4 months (range, 0–28) and 6.1 months (range, 0–26) in the ALBI grade 1 and 2 groups, respectively (Table 3). Patients in the mALBI grade 2a and 2b groups received atezolizumab for a median duration of 6.9 months (range, 0–26) and 4.3 months (range, 0–24), respectively. The median duration of bevacizumab treatment was 9.6 months (range, 0–28) in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup and 4.9 months (range, 0–25) in the ALBI grade 2 subgroup (mALBI grade 2a: 5.1 months [range, 0–25] and grade 2b: 4.7 months [range, 0–24]). Sorafenib treatment was administered for a median of 2.9 months (range 0–25) in patients with ALBI grade 1 and 2.8 months (range, 0–21) for ALBI grade 2 (mALBI grade 2a: 1.9 months [range, 0–21]; grade 2b: 2.8 months [range, 0–21]).

Table 3.

Safety summary by ALBI/mALBI grade

| ALBI grade 1 | ALBI grade 2 | mALBI grade 2a | mALBI grade 2b | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 189)a | sorafenib (n = 81)a | atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 140)a | sorafenib (n = 75)a | atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 71)a | sorafenib (n = 37)a | atezolizumab + bevacizumab (n = 69)a | sorafenib (n = 38)a | |

| Treatment duration, median (range), months | Atezolizumab 10.4 (0–28) Bevacizumab 9.6 (0–28) |

2.9 (0–25) | Atezolizumab 6.1 (0–26) Bevacizumab 4.9 (0–25) | 2.8 (0–21) | Atezolizumab 6.9 (0–26) Bevacizumab 5.1 (0–25) |

1.9 (0–21) | Atezolizumab 4.3 (0–24) Bevacizumab 4.7 (0–24) |

2.8 (0–21) |

| All-grade AE, any cause, n (%) | 185 (98) | 79 (98) | 137 (98) | 75 (100) | 70 (99) | 37 (100) | 67 (97) | 38 (100) |

| Treatment-related all-grade AE | 169 (89) | 75 (93) | 115 (82) | 73 (97) | 61 (86) | 36 (97) | 54 (78) | 37 (97) |

| Grade 3/4 AE, n (%)b | 122 (65) | 47 (58) | 85 (61) | 42 (56) | 46 (65) | 21 (57) | 39 (57) | 21 (55) |

| Treatment-related grade 3/4 AEb | 90 (48) | 37 (46) | 53 (38) | 35 (47) | 27 (38) | 21 (57) | 26 (38) | 14 (37) |

| Serious AE, n (%) | 79 (42) | 22 (27) | 81 (58) | 29 (39) | 38 (54) | 12 (32) | 43 (62) | 17 (45) |

| Treatment-related serious AE | 41 (22) | 10 (12) | 35 (25) | 15 (20) | 12 (17) | 5 (14) | 23 (33) | 10 (26) |

| Grade 5 AE, n (%) | 7 (4) | 3 (4) | 16 (11) | 6 (8) | 5 (7) | 2 (5) | 11 (16) | 4 (11) |

| Treatment-related grade 5 AE | 2 (1)c | 0 | 4 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1)d | 0 | 3 (4)e | 1 (3)f |

| AE leading to withdrawal from any component, n (%) | 33 (17) | 7 (9) | 39 (28) | 11 (15) | 18 (25) | 5 (14) | 21 (30) | 6 (16) |

| AE leading to dose interruption of any study treatment, n (%) | 122 (65) | 28 (35) | 73 (52) | 40 (53) | 37 (52) | 19 (51) | 36 (52) | 21 (55) |

| AE leading to dose modification of sorafenib, n (%)g | 0 | 30 (37) | 0 | 28 (37) | 0 | 14 (38) | 0 | 14 (37) |

AE, adverse event; ALBI, albumin-bilirubin; mALBI; modified ALBI.

aSafety-evaluable population.

bHighest grade experienced.

cGastrointestinal hemorrhage (n = 1) and subarachnoid hemorrhage (n = 1).

dPneumonia (n = 1).

eAbnormal hepatic function (n = 1), liver injury (n = 1), and gastric ulcer perforation (n = 1).

fHepatic cirrhosis (n = 1).

gNo dose modification was allowed for atezolizumab or bevacizumab.

In patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab, all-grade treatment-related AEs (TRAEs) occurred in 169 (89%) and 115 (82%) patients with ALBI grades 1 and 2, respectively (Table 3). In the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm, 61 patients (86%) with mALBI grade 2a and 54 (78%) with mALBI grade 2b had all-grade TRAEs. These TRAEs were of grade 3/4 severity in 90 patients (48%) in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup, 53 (38%) in the ALBI grade 2 subgroup, 27 (38%) in the mALBI grade 2a subgroup, and 26 (38%) in the mALBI grade 2b subgroup. Grade 5 TRAEs occurred in 2 patients (1%) with ALBI grade 1 (gastrointestinal hemorrhage [n = 1] and subarachnoid hemorrhage [n = 1]) and 4 patients (3%) with ALBI grade 2, including 1 (1%) with mALBI grade 2a (pneumonia) and 3 (4%) with mALBI grade 2b (abnormal hepatic function [n = 1], liver injury [n = 1], and gastric ulcer perforation [n = 1]).

In patients receiving sorafenib, TRAEs of any grade occurred in 75 (93%) patients with ALBI grade 1 and 73 (97%) patients with ALBI grade 2 (mALBI grade 2a: 36 [97%]; mALBI grade 2b: 37 [97%]). These events were of grade 3/4 severity in 37 patients (46%) in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup and 35 patients (47%) in the ALBI grade 2 subgroup (mALBI grade 2a: 21 [57%]; mALBI grade 2b: 14 [37%]). Grade 5 TRAEs occurred in 0 patients with ALBI grade 1 and 1 (1%) patient with ALBI grade 2 (mALBI grade 2b [hepatic cirrhosis]).

The most common grade 3/4 AEs in patients who received atezolizumab + bevacizumab were hypertension (ALBI grade 1, 37 patients [20%]; grade 2, 19 patients [14%]) and aspartate aminotransferase increase (ALBI grade 1, 14 patients [7%]; grade 2, 12 patients [9%] [online suppl. Table S1]. In the sorafenib arm, the most common grade 3/4 AEs were hypertension (ALBI grade 1, 13 patients [16%]; grade 2, 6 patients [8%]) and palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome (ALBI grade 1, 8 patients [10%]; ALBI grade 2, 5 patients [7%]). Common grade 3/4 AEs in patients with baseline mALBI grades 2a and 2b are reported in online supplementary Table S1.

In the ALBI grade 1 subgroup, 37% (n = 70) of patients in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm and 54% (n = 47) of patients in the sorafenib arm received subsequent systemic treatments for HCC (online suppl. Table S2). Of the patients who were ALBI grade 2, 35% (n = 50) and 50% (n = 39) received subsequent systemic treatments for HCC in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib arms, respectively. Subsequent systemic treatments in patients with baseline mALBI grades 2a and 2b are reported in online supplementary Table S2.

Discussion

In this post hoc exploratory analysis of the IMbrave150 study, ALBI grade appeared to be prognostic for outcomes with both atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib treatment. Consistent benefits in terms of OS, PFS, and ORR were observed with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients who had ALBI grade 1 at baseline. For ALBI grade 2, efficacy results were not as consistent and may be reflective of smaller numbers of patients and imbalances in prognostic factors.

Atezolizumab + bevacizumab also showed improved efficacy compared with sorafenib, as seen by improvements in PFS per IRF-RECIST 1.1 in the ALBI grade 1 and grade 2 subgroups. In the mALBI grade 2a and 2b subgroups, there was a trend toward improved PFS with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib despite imbalances in patient characteristics. Notably, TTD of liver function was numerically longer with atezolizumab + bevacizumab than with sorafenib. Overall, these analyses provide further support for atezolizumab + bevacizumab as the standard of care for patients with previously untreated, unresectable HCC [26, 27].

A more in-depth analysis of OS suggests that the lack of significant survival benefit with atezolizumab + bevacizumab in the mALBI grade 2a and 2b subgroups may not truly represent the lack of benefit with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib treatment. Imbalances in multiple baseline prognostic factors were observed between treatment arms in this retrospective analysis. In the mALBI grade 2a subgroup, these imbalances include CP class A6, presence of MVI, presence of EHS, and alpha-fetoprotein ≥400 ng/mL. In the mALBI grade 2b subgroup, there were imbalances in the presence of varices, treatment of varices, and incidence of nonviral and HCV etiology of HCC. Many of these are known poor prognostic factors for OS [28–30], which may have reduced OS in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab group with baseline mALBI grade 2a and 2b.

Median OS with sorafenib was 15.4 months in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup and 12.2 months in the ALBI grade 2 subgroup in this analysis. The median OS with sorafenib in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup was similar to those reported in the ALBI grade 1 subgroup of the sorafenib arm in the REFLECT study (14.6 months) and in a pooled analysis of the SHARP and Asia Pacific trials (14.0 months) [24, 29]. However, median OS with sorafenib was 7.7 months (95% CI: 6.1, 10.2) in the ALBI grade 2 subgroup of the REFLECT study and 6.4 months in a pooled analysis of the SHARP and Asia Pacific trials [24, 29]. These inter-trial comparisons should be interpreted with caution due to differences in baseline populations and study designs across trials.

Overall, the findings of the current study are consistent with previous studies that showed that the baseline ALBI grade could predict the prognosis of patients with advanced HCC who received sorafenib [22, 23] or lenvatinib [24]. In addition, patients with baseline ALBI grade 1 had longer OS than those with ALBI grade 2 after treatment with second-line cabozantinib or ramucirumab in the CELESTIAL and REACH/REACH2 trials, respectively [31, 32]. Collectively, these results suggest that ALBI scores are prognostic for treatment outcomes across the landscape of systemic therapies, with a better prognosis in those with baseline ALBI grade 1. These results suggest that the maintenance of liver function is essential to allow patients to derive a greater benefit from systemic therapies.

In this analysis, ORR by IRF-RECIST 1.1 was in the range of 25–32% in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm, regardless of ALBI/mALBI grade. Improved ORRs were observed in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab arm compared with the sorafenib arm in patients with ALBI grade 1 and in patients with mALBI grade 2a, but not in patients with ALBI grade 2 or mALBI grade 2b. However, ORR in the mALBI grade 2b subgroup may have been influenced by the small sample size and baseline imbalances in known prognostic factors such as the presence of varices and HCV etiology.

Improved ORRs were observed in patients with better baseline liver function in this study, similar to the trends seen in the REFLECT and CheckMate 040 trials [24, 33]. ORR was higher in patients with baseline ALBI grade 1 than in those with grade 2 after treatment with either lenvatinib or sorafenib in the REFLECT trial [24]. In the CheckMate 040 study, patients with CP class A had higher ORR than those with CP class B after treatment with nivolumab [33]. Thus, the ORR and PFS data from this analysis further suggest that ALBI/mALBI grading at baseline may be predictive for outcomes after immune therapy.

Atezolizumab + bevacizumab was also able to preserve liver function throughout the follow-up period. Mean ALBI scores remained stable at mALBI grade 2a from baseline to the end of treatment with atezolizumab + bevacizumab, with a slight increase in mean ALBI score observed during cycles 2 and 3 of the treatment cycle. The stability of mean ALBI scores through the treatment period and at disease progression indicates the ability of atezolizumab + bevacizumab to preserve liver function. Median TTD was also numerically longer with atezolizumab + bevacizumab than with sorafenib. As mean ALBI scores are not monitored after treatment discontinuation, data on ALBI scores toward the end of the treatment cycle were calculated based on a small percentage of patients and may not be representative of the entire population. However, TTD is independent of the number of patients continuing treatment and therefore may be a better indicator of preserved liver function in the study population than the change in mean ALBI score.

In the sorafenib arm, the reduction in mean ALBI score over time may be due to the small number of patients. Hence, the impact of sorafenib on the liver function based on mean ALBI scores should be interpreted with caution. Further analyses are underway to investigate the liver function after deterioration in the ALBI score.

Other trials evaluating monoclonal antibody treatments have also observed low liver toxicity, similar to the trends observed in this analysis. In CheckMate 459, nivolumab demonstrated better preservation of liver function than sorafenib, as determined by ALBI and CP scores [34]. An analysis of ALBI scores from the REACH/REACH2 trials concluded that the incremental increase in mean ALBI score from baseline to end of treatment was likely due to disease progression and not due to liver toxicity [32].

The safety and tolerability profile of atezolizumab + bevacizumab was consistent with the known safety profiles of each individual drug and with the underlying disease, regardless of mALBI grade. No new or unexpected safety signals were identified for atezolizumab or bevacizumab in this study. Occurrence of TRAEs across all categories (all-grade, grade 3/4, and serious AEs) was similar in the atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib arms across ALBI/mALBI grades. In the CheckMate 040 study, the occurrence of grade 3/4 TRAEs after treatment with nivolumab was also similar in patients with different levels of liver function (23% with CP class A vs. 24% with CP class B) [33]. In contrast, the REFLECT trial showed that treatment-emergent AEs of grade ≥3 occurred more frequently in patients with ALBI grade 2 than in those with ALBI grade 1 after treatment with either lenvatinib (86% with ALBI grade 2 vs. 69% with grade 1) or sorafenib (77% with ALBI grade 2 vs. 62% with ALBI grade 1) [24]. These data suggest that the occurrence of grade 3/4 TRAEs could be affected by liver function when patients are treated with TKIs but not when they are treated with anti-PD-L1/PD-1 antibodies.

In an exploratory analysis of IMbrave150, treatment with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib reduced the risk of deterioration in patient-reported symptom scales, including appetite loss, diarrhea, and fatigue [35], possibly due to the high specificity and affinity of monoclonal antibodies that target molecules with minimal off-target effects. Conversely, tyrosine kinase inhibitors (such as sorafenib, lenvatinib, cabozantinib, and regorafenib) are known to have off-target effects, inhibiting not only VEGFR but also other receptors such as PDGFR, FGFR, and c-kit [36]. These off-target inhibitions are associated with increased toxicity and occurrence of AEs such as fatigue, diarrhea, nausea, anorexia, hand-foot skin reaction, decreased appetite, and hypertension [36–38]. These findings suggest that the improved tolerability of atezolizumab + bevacizumab compared with sorafenib may be due to differences in the mechanism of action of anti-PD-L1/PD-1 inhibitors and TKIs.

Due to the post hoc exploratory design of this analysis, there were a limited number of patients within each ALBI/mALBI subgroup, as well as imbalances between baseline characteristics between subgroups. Hence, results should be interpreted with caution. As only patients with CP class A liver function were included in the IMbrave150 study, this analysis does not reflect a true distribution of ALBI grades in patients with HCC. Liver function was not monitored after the end of treatment as data on mean ALBI scores were only available until discontinuation of treatment in each arm. Thus, it is unclear for how long the preservation of liver function was sustained after treatment discontinuation. The ALBI grading system was used in this analysis because it is more objective than CP class as it does not include subjective assessments of factors such as the severity of ascites and encephalopathy. However, further investigation is needed to determine which liver function assessment is more appropriate in identifying patients who might benefit from 1L treatment with atezolizumab + bevacizumab. Nonetheless, this study sheds light on the impact of baseline ALBI grade on outcomes in patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab or sorafenib.

Conclusion

In this exploratory analysis of IMbrave150, ALBI grade appeared to be prognostic for outcomes with both atezolizumab + bevacizumab and sorafenib treatment for patients with HCC. Median PFS was improved with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with ALBI grade 1 and ALBI grade 2 at baseline. There was a trend toward improved PFS with atezolizumab + bevacizumab in the mALBI grade 2a and mALBI grade 2b subgroups, despite imbalances in patient characteristics. Median OS was improved with atezolizumab + bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with ALBI grade 1 at baseline but not in patients with ALBI grade 2. In addition, TTD of liver function was longer with the use of the combination versus sorafenib, showing the ability of atezolizumab + bevacizumab to preserve liver function during the treatment period. These results support atezolizumab + bevacizumab as the standard of care for patients with previously untreated, unresectable HCC and could be clinically useful in stratifying outcomes for patients receiving atezolizumab + bevacizumab.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients who participated in the trial, the patients’ families, and the investigators and staff at all clinical study sites. Third-party medical writing assistance for this manuscript was provided by Akshaya Srinivasan, PhD, of MediTech Media Ltd.

Statement of Ethics

IMbrave150 was carried out in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study. Protocol approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Ethics Committee (EC) at each site. The first IRB approval for IMbrave150 was granted on December 19, 2017, from the City of Hope National Medical Center, Duarte, CA, USA (IRB No. 20172734; Western Institutional Review Board, Inc., Puyallup, WA, USA), in addition to multiple other EC/IRB approvals obtained across all participating sites in the different countries of enrollment. An independent data monitoring committee reviewed unmasked safety and trial conduct data approximately every 6 months until study unblinding. The study sponsor supplied the study drugs and collaborated with academic authors on the study design, data collection, data analysis, and data interpretation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Masatoshi Kudo reports the following conflicts of interest: honoraria payment to self from Bayer, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Eli Lilly, Eisai, and Takeda; research funding to institution from AbbVie, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., EA Pharma, Eisai, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., GE Healthcare, Gilead Sciences, Otsuka, Sumitomo Dainippon Pharma, Taiho, and Takeda; Editor-in-Chief of Liver Cancer. Richard S. Finn reports the following conflicts of interest: consulting fees to self from AstraZeneca, Bayer, CStone Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Exelixis, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Hengrui, Merck, and Pfizer; research funding to institution from Adaptimmune, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd; Editorial Board Member of Liver Cancer. Ann-Lii Cheng reports the following conflicts of interest: research funding to institution from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Andrew X. Zhu reports the following conflicts of interest: consulting fees to self from Eisai, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., and Sanofi-Aventxis; research funding to the institution from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Michel Ducreux reports the following conflicts of interest: honoraria, consulting fees, or advisory fees to self from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Ipsen, Merck Serono, Pierre Fabre, and Servier; travel support from Bayer, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Servier; speaker bureau participation for Amgen, Bayer, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Ipsen, and Merck Serono; research funding to institution from Bayer and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Peter R. Galle reports the following conflicts of interest: consulting fees to self from Adaptimmune, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Guerbet, Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Sirtex Medical; honoraria payment to self from Adaptimmune, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Guerbet, Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Sirtex Medical; advisory fees to self from Adaptimmune, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Eli Lilly, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Guerbet, Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, and Sirtex Medical; research funding to institution from Bayer and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Naoya Sakamoto reports the following conflicts of interest: honoraria payment to self from AbbVie, Eisai, Gilead Sciences, and Otsuka; research funding to institution from Astellas Pharmaceutical, Bayer, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Daiichi Sankyo, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Gilead Sciences, Otsuka, and Takeda. Naoya Kato reports the following conflicts of interest: honoraria payment to self from Bayer and Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; research funding to institution from Bayer, Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Michitaka Nakano reports the following conflicts of interest: employment by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Jing Jia reports the following conflicts of interest: employment by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Arndt Vogel reports the following conflicts of interest: consulting fees to self from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Böhringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, BTG Limited, Eisai, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Imaging Equipment Ltd. (AAA), Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Servier Laboratories, Sirtex Medical, and Terumo; honoraria payment to self from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Böhringer Ingelheim, Bristol Myers Squibb, BTG Limited, Eisai, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Imaging Equipment Ltd. (AAA), Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Servier Laboratories, Sirtex Medical, and Terumo; travel support from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, and F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.; advisory fees to self from AstraZeneca, Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, BTG Limited, Eli Lilly, Eisai, F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd., Imaging Equipment Ltd. (AAA), Ipsen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Sirtex Medical, Servier Laboratories, and Terumo; research funding to institution from F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd.

Funding Sources

This study was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Third-party medical writing assistance was sponsored by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Author Contributions

Masatoshi Kudo contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, data curation, writing – review and editing, and supervision; Richard S. Finn contributed to conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing – review and editing, and supervision; Ann-Lii Cheng contributed to conceptualization, methodology, validation, data curation, writing – review and editing and supervision; Andrew X. Zhu contributed to validation, investigation, resources, writing – review and editing, and visualization; Michel Ducreux and Peter R. Galle contributed to conceptualization, investigation, and writing – review and editing; Naoya Sakamoto contributed to investigation and writing – review and editing; Naoya Kato contributed to investigation, writing – review and editing, and supervision; Michitaka Nakano contributed to writing – original draft, writing – review and editing, and visualization; Jing Jia contributed to formal analysis and writing – review and editing; Arndt Vogel contributed to conceptualization, visualization, data curation, writing – review and editing, and visualization.

Funding Statement

This study was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd. Third-party medical writing assistance was sponsored by Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.

Data Availability Statement

For eligible studies, qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level clinical data through a data request platform. At the time of writing, this request platform is Vivli (https://vivli.org/ourmember/roche/). For up-to-date details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see https://go.roche.com/data_sharing. Anonymized records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche cannot, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient re-identification. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49. 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Giannini EG, Farinati F, Ciccarese F, Pecorelli A, Rapaccini GL, Di Marco M, et al. Prognosis of untreated hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):184–90. 10.1002/hep.27443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Llovet JM, Ricci S, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, Gane E, Blanc JF, et al. Sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(4):378–90. 10.1056/NEJMoa0708857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kudo M, Finn RS, Qin S, Han KH, Ikeda K, Piscaglia F, et al. Lenvatinib versus sorafenib in first-line treatment of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomised phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10126):1163–73. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–905. 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Tecentriq (atezolizumab) . Prescribing information. South San Francisco (CA): Genentech, Inc; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pharmaceuticals, Medical Devices Agency . Review report (tecentriq) 2020. Available from: https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs/2020/P20200925002/450045000_23000AMX00014_A100_1.pdf.

- 8. Cheng AL, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Updated efficacy and safety data from IMbrave150: atezolizumab plus bevacizumab vs. sorafenib for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(4):862–73. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Raoul JL, Bruix J, Greten TF, Sherman M, Mazzaferro V, Hilgard P, et al. Relationship between baseline hepatic status and outcome, and effect of sorafenib on liver function: SHARP trial subanalyses. J Hepatol. 2012;56(5):1080–8. 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D’Avola D, Granito A, Torre-Aláez M, Piscaglia F. The importance of liver functional reserve in the non-surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2022;76(5):1185–98. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Johnson PJ, Berhane S, Kagebayashi C, Satomura S, Teng M, Reeves HL, et al. Assessment of liver function in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a new evidence-based approach-the ALBI grade. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(6):550–8. 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kudo M. Albumin-bilirubin grade and hepatocellular carcinoma treatment algorithm. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(3):185–8. 10.1159/000462199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Michitaka K, Toyoda H, Tada T, Ueki H, et al. Usefulness of albumin-bilirubin grade for evaluation of prognosis of 2,584 Japanese patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(5):1031–6. 10.1111/jgh.13250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pinato DJ, Sharma R, Allara E, Yen C, Arizumi T, Kubota K, et al. The ALBI grade provides objective hepatic reserve estimation across each BCLC stage of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):338–46. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chan AWH, Kumada T, Toyoda H, Tada T, Chong CCN, Mo FKF, et al. Integration of albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score into Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) system for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31(7):1300–6. 10.1111/jgh.13291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hiraoka A, Michitaka K, Kumada T, Izumi N, Kadoya M, Kokudo N, et al. Validation and potential of albumin-bilirubin grade and prognostication in a nationwide survey of 46,681 hepatocellular carcinoma patients in Japan: the need for a more detailed evaluation of hepatic function. Liver Cancer. 2017;6(4):325–36. 10.1159/000479984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hiraoka A, Kumada T, Tsuji K, Takaguchi K, Itobayashi E, Kariyama K, et al. Validation of modified ALBI grade for more detailed assessment of hepatic function in hepatocellular carcinoma patients: a multicenter analysis. Liver Cancer. 2019;8(2):121–9. 10.1159/000488778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kudo M. Newly developed modified ALBI grade shows better prognostic and predictive value for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2022;11(1):1–8. 10.1159/000521374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Cho WR, Hung CH, Chen CH, Lin CC, Wang CC, Liu YW, et al. Ability of the post-operative ALBI grade to predict the outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative surgery. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7290. 10.1038/s41598-020-64354-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Luo HM, Zhao SZ, Li C, Chen LP. Preoperative platelet-albumin-bilirubin grades predict the prognosis of patients with hepatitis B virus-related hepatocellular carcinoma after liver resection: a retrospective study. Medicine. 2018;97(12):e0226. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lin CY, Lin CC, Wang CC, Chen CL, Hu TH, Hung CH, et al. The ALBI grade is a good predictive model for very late recurrence in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing primary resection. World J Surg. 2020;44(1):247–57. 10.1007/s00268-019-05197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kuo YH, Wang JH, Hung CH, Rau KM, Wu IP, Chen CH, et al. Albumin-bilirubin grade predicts prognosis of HCC patients with sorafenib use. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32(12):1975–81. 10.1111/jgh.13783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abdel-Rahman O. Impact of baseline characteristics on outcomes of advanced HCC patients treated with sorafenib: a secondary analysis of a phase III study. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2018;144(5):901–8. 10.1007/s00432-018-2610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Vogel A, Frenette C, Sung M, Daniele B, Baron A, Chan SL, et al. Baseline liver function and subsequent outcomes in the phase 3 REFLECT study of patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2021;10(5):510–21. 10.1159/000516490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pinato DJ, Yen C, Bettinger D, Ramaswami R, Arizumi T, Ward C, et al. The albumin-bilirubin grade improves hepatic reserve estimation post-sorafenib failure: implications for drug development. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(5):714–22. 10.1111/apt.13904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bruix J, Chan SL, Galle PR, Rimassa L, Sangro B. Systemic treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: an EASL position paper. J Hepatol. 2021;75(4):960–74. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Llovet JM, Villanueva A, Marrero JA, Schwartz M, Meyer T, Galle PR, et al. Trial design and endpoints in hepatocellular carcinoma: AASLD Consensus Conference. Hepatology. 2021;73(Suppl 1):158–91. 10.1002/hep.31327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ducreux M, Zhu AX, Cheng A-L, Galle PR, Ikeda M, Nicholas A, et al. IMbrave150: exploratory analysis to examine the association between treatment response and overall survival (OS) in patients (pts) with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) treated with atezolizumab (atezo) + bevacizumab (bev) versus sorafenib (sor). J Clin Oncol. 2021;39(15_Suppl l):4071. 10.1200/jco.2021.39.15_suppl.4071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bruix J, Cheng AL, Meinhardt G, Nakajima K, De Sanctis Y, Llovet J. Prognostic factors and predictors of sorafenib benefit in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of two phase III studies. J Hepatol. 2017;67(5):999–1008. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Giannini EG, Risso D, Testa R, Trevisani F, Di Nolfo MA, Del Poggio P, et al. Prevalence and prognostic significance of the presence of esophageal varices in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4(11):1378–84. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Miksad R, Cicin I, Chen Y, Klumpen H, Kim S, Lin Z, et al. Outcomes based on albumin‐bilirubin (ALBI) grade in the phase 3 CELESTIAL trial of cabozantinib versus placebo in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Ann Oncol. 2019;30:iv134. 10.1093/annonc/mdz154.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kudo M, Galle PR, Brandi G, Kang YK, Yen CJ, Finn RS, et al. Effect of ramucirumab on ALBI grade in patients with advanced HCC: results from REACH and REACH-2. JHEP Rep. 2021;3(2):100215. 10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kudo M, Matilla A, Santoro A, Melero I, Gracián AC, Acosta-Rivera M, et al. CheckMate 040 cohort 5: a phase I/II study of nivolumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma and Child-Pugh B cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2021;75(3):600–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sangro B, Park J, Finn R, Cheng A, Mathurin P, Edeline J, et al. LBA-3 CheckMate 459: long-term (minimum follow-up 33.6 months) survival outcomes with nivolumab versus sorafenib as first-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2020;31:S241–2. 10.1016/j.annonc.2020.04.078. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Galle PR, Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Zhu AX, Kim TY, et al. Patient-reported outcomes with atezolizumab plus bevacizumab versus sorafenib in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (IMbrave150): an open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(7):991–1001. 10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00151-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ivy SP, Wick JY, Kaufman BM. An overview of small-molecule inhibitors of VEGFR signaling. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6(10):569–79. 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gadaleta RM, Moschetta A. Dark and bright side of targeting fibroblast growth factor receptor 4 in the liver. J Hepatol. 2021;75(6):1440–51. 10.1016/j.jhep.2021.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rimassa L, Danesi R, Pressiani T, Merle P. Management of adverse events associated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors: improving outcomes for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;77:20–8. 10.1016/j.ctrv.2019.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

For eligible studies, qualified researchers may request access to individual patient-level clinical data through a data request platform. At the time of writing, this request platform is Vivli (https://vivli.org/ourmember/roche/). For up-to-date details on Roche’s Global Policy on the Sharing of Clinical Information and how to request access to related clinical study documents, see https://go.roche.com/data_sharing. Anonymized records for individual patients across more than one data source external to Roche cannot, and should not, be linked due to a potential increase in risk of patient re-identification. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.