Abstract

Of all complications from central venous catheters (CVC) in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients, catheter-related bloodstream infection (CRBSI) is one of the most devastating consequences. The option of catheter salvage is not an effective measure with metastatic infections. However, in patients with severe vasculopathy and/or near end-stage vascular disease, preservation of the venous access should be given utmost importance as the luxury of utilizing another vascular site is markedly limited. Providing adequate renal replacement therapy in this group of patients can be remarkably challenging for nephrologists. We are presenting an ESRD patient with advanced vascular disease who developed metastatic CRBSI with worsening uremia who was successfully converted from intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) to peritoneal dialysis (PD). Our rationale was to minimize repeated intravascular procedures coupled with the presence of another intravascular device. This has led to a complete resolution of persistent bacteremia, with a steady improvement in the uremic state. Conversion from IHD to PD for persistent bacteremia with metastatic complications was seldom addressed in literature. In the absence of a significant contraindication to PD, it can be considered as a valid alternative possibility in order to interrupt this viscous cycle, especially in vasculopathic patients.

Keywords: End-stage renal disease, Catheter-related bloodstream infection, Intermittent hemodialysis, Peritoneal dialysis, Renal replacement therapy, Acute kidney injury, Intensive care unit, Emergency department

Introduction

Among several patient groups utilizing emergency department (ED) services, end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients are evaluated 4–6-fold higher than the national mean rates [1], with the presence of a catheter as hemodialysis access being the strongest predictor for using ED resources. With cardiovascular disease being the top cause of morbidity and mortality in ESRD patients, infections rank as the second leading cause of death in ESRD patients. The primary cause for most of these infections is catheter-related bloodstream infections (CRBSI). CRBSI constitutes a significant cause of hospitalization and mortality in intermittent hemodialysis (IHD) patients, reported from the literature ranging between 6% and 34% [2].

The prevalence of atherosclerotic vascular disease in ESRD is around 25–30% [3]. In addition to traditional risk factors, the presence of central venous catheters (CVCs) contributes to excessive oxidative stress and thereby leads to accelerated atherosclerosis and mortality [4]. It is quite hard-won to start and keep any vascular access in these patients, without intercurrent complications (poor blood flows with inadequate uremic control and infections).

Peritoneal dialysis (PD) is another form of continuous or extracorporeal renal replacement therapy. PD was initially used in the 1920s to treat acute kidney injury (AKI), but it was not revisited until 1946, when it became a life-saving dialytic modality [5]. Contemporary reviews have shown an effective direct start of PD without the requirement for transitory vascular access [6]. However, emphasizing the option of PD in such clinical settings may be met with a lack of experience among the newer generation of nephrologists, as most encounters with prevalent dialysis patients involve IHD rather than PD, thus creating a façade of no options but to pursue IHD in sick patients. The CARE Checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see https://doi.org/10.1159/000531094).

Case Presentation

A 70-year-old African-American male with a history of ESRD on (IHD) for about 5 years came to ED because of fever, headaches, chills, and nausea. Comorbid conditions included non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, hypertension, severe peripheral arterial disease, recurrent vascular access thrombosis, and symptomatic bradyarrhythmia requiring a permanent implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (AICD). Due to the long vintage on IHD, and multiple dialysis catheters, his upper half central veins were considered significantly stenotic or completely occluded, with the right femoral being the last patent vein available for cannulation. His home medications included aspirin, calcium acetate, carvedilol, cinacalcet, insulin, warfarin, gabapentin, simvastatin, and esomeprazole.

Vital signs upon arrival to ED were a temperature of 105 Fahrenheit (40.50 Celsius), blood pressure of 108/51 mm Hg, heart rate of 114 beats per minute, regular, respiratory rate of 14 per minute, and oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. On physical examination, he was alert, cooperative, and oriented, with no rash or finger clubbing. Lungs were clear to auscultation, and there was no erythema, tenderness, or fluctuation over the AICD site. The cardiovascular examination revealed regular heart sounds and no gallop rhythm. However, he had an audible grade 2/6 late diastolic murmur best heard at the right upper sternal border, with no pericardial rub, organomegaly, or peripheral edema. A local exam of the right femoral cuffed catheter revealed minimal erythema, but no warmth, tenderness, or discharge could be appreciated over the subcutaneous tunnel or the exit sit, respectively.

Initial laboratory findings: sodium of 135 mmol/L, potassium of 4.8 mmol/L, chloride of 96 mmol/L, bicarbonate of 23 mmol/L, blood urea nitrogen of 68 mg/dL, and creatinine of 11.12 mg/dL. In addition, lactic acid was 1.7 mmol/L, international normalized ratio 2.57, white blood cells of 10.8 k/mm3, hemoglobin 8.6 gm/dL, hematocrit 25.5%, and a platelets’ count of 79 k/mm3.

Hospital Course

Based on the clinical picture on the first presentation, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotics coverage, including cefepime and vancomycin, was started at once after sending blood for cultures from the peripheral and right femoral catheter ports, followed by transfer to the intensive care unit for close monitoring. Later work-up revealed the following: CT scan of the head as well as a chest x-ray was essentially unremarkable. CSF examination was negative, and two sets of blood cultures have grown methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), cuffed catheter tip was negative on cultures. A transthoracic echocardiogram was concerning for an echogenic tricuspid valve mass. Trans-esophageal echocardiography confirmed tricuspid valve infectious endocarditis and AICD pocket infection. Subsequently, antibiotics were changed to ampicillin, vancomycin, and cefepime. A day later the AICD was removed, and the tunneled catheter was exchanged over a guidewire with a new catheter at the same femoral site as the patient did not have an alternative vein for cannulation. Despite exchange of the dialysis catheter and removal of the AICD and debridement of its pocket, the patient continued to spike a fever with blood cultures persistently positive for MRSA. Based on this, a decision was made to exchange the cuffed catheter with a temporary non-cuffed catheter to help frequent changes every 48 h. However, his general condition started taking a steep downhill course with worsening delirium, associated with deterioration of the hemodynamic status, dictating initiation of intravenous fluids and vasopressors’ support.

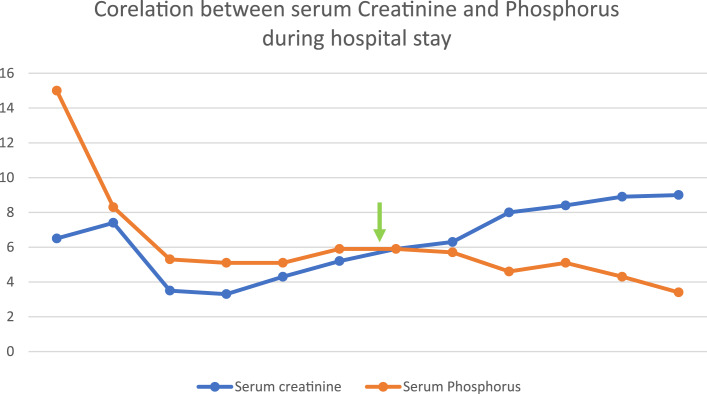

Given his persistent metastatic infection and to minimize the presence of intravascular devices, a decision was made to remove the right femoral catheter and transition him to PD. A peritoneal catheter was inserted in less than 48 h. The initial PD plan was that of gradual escalation of both volume and frequency of exchanges over a 72-h period to minimize leaks and infections. This was well-tolerated, with a substantial improvement in his overall clinical status including mentally and hemodynamically with resolution of fever. Plasma biochemistry has also improved with a remarkable change in the earlier uremic status (Fig. 1; Table 1). Intravenous daptomycin was continued for a total of 6 weeks. Eventually, the patient was discharged to a long-term nursing facility on long-term chronic manual ambulatory PD.

Fig. 1.

The trend of renal functions during the hospital stays. Arrow indicates the initiation of peritoneal dialysis.

Table 1.

Blood cultures result during the hospital stay

| Blood culture gram-positive cocci | Catheter tip culture | |

|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | Positive | |

| Day 2 | Positive | |

| Day 3 | Positive | |

| Day 4 | Positive | |

| Day 5 | Negative | |

| Day 6 | Positive | |

| Day 7 | Positive | |

| Day 8 | Positive | |

| Day 9 | Positive | |

| Day 10 | Positive | |

| Day 11 | Positive | |

| Day 12 | Negative | Negative |

| Day 13 | Negative | |

| Day 15 | Negative | |

| Day 16 | Negative | |

| Day 17 | Negative | Negative |

| Day 20 | Negative | |

| Day 21 | Negative |

Discussion

Dialysis catheter-related infections are generally divided into exit site, tunnel-related, and CRBSI. Exit site infection is characterized by erythema, tenderness, induration, or exudate within 2 cm from the exit site. Tunnel infection is characterized by erythema, tenderness, and induration/or fluctuation overlying the subcutaneous tunnel tract (which extends for ≥2 cm [about 0.79 in] from the exit site). Tunnel infection is perilous because of the arduousness in treating as antibiotics cannot perforate because of biofilm.

In certain circumstances, the criteria for CRBSI might not be typical, and our case is no exception. Experts have suggested an alternative classification system, which categorizes bacteremia as definite, probable, and possibly related to CVC. Microorganisms reach the CVC through the percutaneous route at the time of insertion or a few days afterward or contaminate the catheter hub (and lumen) when the catheter is inserted over a percutaneous guidewire. To precipitate CRBSI, microorganisms must gain access to the extra-luminal or intraluminal surface of the catheter, where they merge with a preexisting biofilm, which is considered as one of the best media for bacterial proliferation [7]. In our patient, catheter removal was not an option, as the lack of other vascular sites was a major limitation which led to frequent exchanges of the catheter. This is only applicable to patients with a reasonable degree of hemodynamic stability. As is well-known, in the febrile hemodynamically unstable patient particularly if there is a suspicion of a metastatic infectious complication urgent removal of the catheter becomes quite mandatory. The need for adequate dialysis to supply sufficient control of clinical uremia cannot be overemphasized. However, an adequately functioning vascular access is the Achilles heel for making dialysis effective and successful. Most ESRD patients suffer from extensive vascular disease, largely multifactorial in nature (coexistent hypertension, PAD, CAD, CVD, anemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism, chronic uremic inflammation, and hyperhomocysteinemia). Due to a strong history of recurrent thrombosis and stenosis, this patient has only one life-saving access. Thus, there is a need to salvage access sites as much as possible, especially in vasculopathic patients [8].

The clinical management of CRBSI is largely based upon experts’ opinion, case series, and reports as well as single-center observational retrospective studies [2]. In a hemodynamically stable patient, with a long vintage on IHD or limited available vascular access sites, catheter salvage might not be an unreasonable therapeutic option [8]. In our patient, reported right femoral site had no clear evidence of infection over the exit site or subcutaneous tunnel. Our patient underwent catheter exchange over a guidewire over the same remaining access site but continued to be febrile with persistent MRSA bacteremia. This was followed shortly by removal of the AICD. Despite the above measures his clinical status continued to deteriorate, leading to the entire removal of the temporary catheter altogether. This was followed by worsening clinical uremia, metabolic acidosis, azotemia, and hyperphosphatemia, leading to consideration of an urgent alternative mode of RRT that does not involve access to his vascular system (Fig. 1). Following insertion of the Tenhoff’s catheter and urgent conversion to PD, his blood cultures have become negative and plasma biochemistry improved steadily mirrored by a major change in his overall uremic status. To our knowledge, and following an extensive literature search, our case being reported might be one of the very few cases reported with a similar scenario. The significance of reporting the successful transition of IHD to PD in such sick patients helps dispel some myths about PD, such as perceived effectiveness and safety in septic patients. The root of such myths is probably related to the growing concerns of lack of preparedness among new nephrology fellowship graduates. In a 2017 survey among new nephrology graduates, nearly half reported needing more PD training.

Lately, there has been an emerging concept of urgent PD for late referral of CKD and AKI patients [9]. Thus, we implemented a similar concept in our patients. We started PD at once to save the patient after placing a PD catheter rather than waiting a traditional period of 2 weeks. The traditional waiting period has been recommended to minimize the risk of catheter-related complications, specifically pericatheter or incisional leaks, and allow for the training of patients before they start PD at home.

A traditional waiting period around 2 weeks reduces these complications and prevents catheters from spontaneous migration. Usage of lower fill volumes while keeping the patient supine mitigates some of these problems. Few studies assessed catheter problems such as malfunction, migration, poor draining, and or primary failure [10]. Strikingly, these complexities were overseen conservatively without surgery or substitution. Poulsen and Ivarsson demonstrated that those total mechanical complications occurred significantly more in urgent-start than conventional start PD [11]. In ESRD patients on PD, conversion to HDx is not an uncommon practice, with the commonest causes being fungal, recurrent bacterial peritonitis, sclerosing peritonitis, and peritoneal membrane failure. However, the reverse is true in our reported case, caused by worsening clinical uremia, and persistent bacteremia with life-threatening metastatic complications.

The International Society of Peritoneal Dialysis (ISPD) published consensus guidelines about acute PD catheter insertion and PD prescription regimens for AKI [12]. We used this regimen for our patients: utilizing low volume, short, and frequent cycles. Compared with elective PD initiation, urgent-start PD needs a lot of commitment infrastructure and surgical backup. Hospitals should have a mechanism for rapid PD catheter placement, early initiation of PD therapy with a modified prescription, adequate staffing, nursing, and adequate space.

Often, we see a frequent conversion from PD to hemodialysis. However, reverse conversion from hemodialysis to PD is much less commonly seen in practice. Evidence from literature supports that cardiovascular problems, hemodynamic intolerance, vascular problems, and the personal choice of a patient are the leading causes of transfer. Cardiovascular disease is one of the major reasons for conversion [13].

Conclusion

Treating CRBSI in an ESRD patient with vasculopathy is a therapeutic intricacy for all healthcare professionals and paramedical staff. Both catheter salvage and catheter vacation should be given top priority in managing these patients. Given the high mortality of CRBSI, there is a great desideratum for evidence-based practice in the clinical management. For efficient RRT, PD is dependably a reinforcement alternative in these group of patients. One should recollect that not all patients were congruous for urgent PD with prompt placement of PD catheter and implementation of urgent PD prescription. Our case stands as exceptional as conversion from IHD to PD in an Intensive care setting was successful. This valuable therapeutic option, which is terribly underutilized by the nephrology community, should be considered, especially in under dire situations when there are not many options available. All health care professionals not limited to nephrologists should be aware of that PD can be considered as a surrogate or back up choice for these patients and can be extended to AKI groups who require RRT in intensive care unit.

Statement of Ethics

This retrospective review of patient data did not require ethical approval in accordance with local/national guidelines. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of the details of their medical case and any accompanying images.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

No funding resources are needed.

Author Contributions

Mohamedanwar Ghandour: wrote the discussion, Ravi K. Themisetty: wrote abstract and introduction, Nashat Imran: did the literature review and wrote up the conclusion, James Sondheimer and Zeenat Y. Bhat: reviewed the article, and Yahya Mohamed Osman-Malik: revised the manuscript.

Funding Statement

No funding resources are needed.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this case report are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Lovasik BP, Zhang R, Hockenberry JM, Schrager JD, Pastan SO, Mohan S, et al. Emergency department use and hospital admissions among patients with end-stage renal disease in the United States. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(10):1563–5. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.4975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Miller LM, Clark E, Dipchand C, Hiremath S, Kappel J, Kiaii M, et al. Hemodialysis tunneled catheter-related infections. Can J Kidney Heal Dis. 2016;3:2054358116669129. 10.1177/2054358116669129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rajagopalan S, Dellegrottaglie S, Furniss AL, Gillespie BW, Satayathum S, Lameire N, et al. Peripheral arterial disease in patients with end-stage renal disease: observations from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS). Circulation. 2006;114(18):1914–22. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.607390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liakopoulos V, Roumeliotis S, Gorny X, Dounousi E, Mertens PR. Oxidative stress in hemodialysis patients: a review of the literature. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2017;2017:3081856. 10.1155/2017/3081856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rebić D, Herenda V. Is peritoneal dialysis a suitable method of renal replacement therapy in acute kidney injury? In: Ekart R, editor. Some special problems in peritoneal dialysis. Rijeka: InTech; 2016. 10.5772/64668. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Casaretto A, Rosario R, Kotzker WR, Pagan-Rosario Y, Groenhoff C, Guest S. Urgent-start peritoneal dialysis: report from a U.S. private nephrology practice. Adv Perit Dial. 2012;28:102–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Böhlke M, Uliano G, Barcellos FC. Hemodialysis catheter-related infection: prophylaxis, diagnosis and treatment. J Vasc Access. 2015;16(5):347–55. 10.5301/jva.5000368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Aslam S, Vaida F, Ritter M, Mehta RL. Systematic review and meta-analysis on management of hemodialysis catheter-related bacteremia. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;25(12):2927–41. 10.1681/ASN.2013091009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alkatheeri AMA, Blake PG, Gray D, Jain AK. Success of urgent-start peritoneal dialysis in a large Canadian renal program. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36(2):171–6. 10.3747/pdi.2014.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Banli O, Altun H, Oztemel A. Early start of CAPD with the Seldinger technique. Perit Dial Int. 2005;25(6):556–9. 10.1177/089686080502500610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Povlsen JV, Ivarsen P. How to start the late referred ESRD patient urgently on chronic APD. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2006;21(Suppl 2):ii56–9. 10.1093/ndt/gfl192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cullis B, Abdelraheem M, Abrahams G, Balbi A, Cruz DN, Frishberg Y, et al. Peritoneal dialysis for acute kidney injury. Perit Dial Int. 2014;34(5):494–517. 10.3747/pdi.2013.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lobbedez T, Crand A, Le Roy F, Landru I, Quéré C, Ryckelynck J-P. Transfer from chronic haemodialysis to peritoneal dialysis. Nephrol Ther. 2005;1(1):38–43. 10.1016/j.nephro.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this case report are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.