Abstract

Child abuse and neglect (CAN) medical experts provide specialized multidisciplinary care to children when there is concern for maltreatment. Their clinical notes contain valuable information on child- and family-level factors, clinical concerns, and service placements that may inform the needed supports for the family. We created and implemented a coding system for data abstraction from these notes. Participants were 1,397 children ages 0–17 years referred for a consultation with a CAN medical provider at an urban teaching and research hospital between March 2013 and December 2017. Coding themes were developed using an interdisciplinary team-based approach to qualitative analysis, and descriptive results are presented using a developmental-contextual framework. This study demonstrates the potential value of developing a coding system to assess characteristics and patterns from CAN medical provider notes, which could be helpful in improving quality of care and prevention and detection of child abuse.

Keywords: child maltreatment, health professionals, qualitative research, medical aspects

Introduction

Child maltreatment is a common, serious, and costly problem in the United States, with 7.1 million children referred to Child Protective Services in 2020 (USDHHS, 2022). Child maltreatment is more likely to occur when a family’s stressors and risks outweigh their supports and protective factors (Belsky, 1993). Examining these factors in context is crucial. A developmental-contextual approach to the ecology of child maltreatment considers the interaction of multiple factors at multiple contextual levels (e.g., developmental, demographic, immediate-situational) that may increase the likelihood of child abuse and neglect (Belsky, 1993; Bronfenbrenner, 1979). Approaching the problem of child maltreatment with a developmental-contextual ecological approach and an understanding of the individual- and family-level risk and protective factors involved allows medical providers a broader view of families’ experiences. It also enables them to engage with other services in a collaborative, multi-system response.

Given the potential serious long-term effects, children who are suspected to have been maltreated require specialized, multidisciplinary care that takes contextual factors into consideration. In their efforts to perform medical evaluations for concerns of child maltreatment, child abuse and neglect (CAN) medical providers elicit social history and risk factors in addition to past medical and family history and presenting issues. Evaluations usually include obtaining histories from the child’s caregiver/s who report on social drivers of health, family and caregiver networks, family medical history, and risk factors such as interpersonal violence, criminal justice system involvement, and substance use. Additional histories may also be provided by social workers and law enforcement if they are involved. During outpatient visits, the child also undergoes a diagnostic interview. Child abuse and neglect (CAN) medical providers perform medical record reviews and physical examinations for children referred for abuse and neglect concerns, including laboratory tests, radiographic tests, and photo documentation as needed. They also provide referrals to other pediatric subspecialties such as mental health, community support, and prevention programs. CAN medical providers participate in multidisciplinary teams which may include community agencies investigating and managing abuse and neglect cases. They may also be asked to provide expert testimony (Block & Palusci, 2006). Additionally, CAN medical clinics develop and coordinate care plans for children and their families to mitigate factors that can contribute to poor outcomes.

Increasingly, this information from medical evaluations is being captured within electronic health records (EHR). These clinical notes are a rich source of information on child- and family-level factors and social drivers that may directly contribute to both the incidence of maltreatment and treatment outcomes. Such information could be extremely helpful in improving quality of care and prevention and detection of child abuse. However, given the intended purpose of these notes, it can be difficult to derive discrete data elements in a consistent and reliable manner.

Limited research has thoroughly examined the notes documented in CAN medical clinics. One such effort examined inpatient medical notes from children younger than five years who had sustained one of three specific injury types that could be suspicious for physical abuse (traumatic brain injury, long bone fracture, and skull fracture) (Olson et. al., 2018). Through qualitative content analysis, the researchers found rich social histories contained in the 730 sets of inpatient medical consultation notes provided by 32 board-certified pediatricians from 23 child abuse programs in the United States. This study provides an example of the utility of coding CAN medical provider notes, but it is limited in the scope of developmental stages and types of maltreatment it examined.

The purpose of the current study was to create a coding system for record abstraction and examination of comprehensive CAN clinician notes. We evaluated over 1,400 children and adolescents 0–17 years of age who were assessed at a hospital-based CAN clinic, including both inpatient and outpatient records, and all types of suspected maltreatment (i.e., physical, sexual, emotional, and medical abuse; neglect). The information in the notes was gathered through interviews by the care team using a structured template, but the notes themselves were stored without any structure in place to allow for data to be easily extracted. Here, we provide a detailed description of our protocol and considerations for developing and implementing a coding system designed to assess case characteristics, such as training and supervising coders to obtain the optimal data. We present baseline descriptive data to demonstrate the utility of variables extracted from both structured EHR data and clinical notes. Finally, we provide recommendations for further research using these methods.

Methods

Participants

The sample used in this study includes children ages 0–17 years who were referred for an inpatient or outpatient consultation with a CAN medical provider between March 13, 2013, and December 1, 2017. We use the term “focal child” to denote the index child participant referred for consultation. Because children are likely to receive care within the county in which they live, we limited our sample to children who resided in the same county as the hospital at the time of the visit.

Data

Data for this study were derived from the EHR of an urban teaching and research hospital in the Southeastern United States utilizing the hospital’s secure protected analytic workspace in which sensitive EHR data can be stored and analyzed. This hospital has a CAN medical evaluation clinic for patients who are suspected to have experienced child abuse and/or neglect. We use the term “child abuse and neglect (CAN) medical providers” because our team includes child abuse pediatricians and other advanced practice providers such as nurse practitioners specializing in the care of children who have experienced maltreatment (Herold et al., 2018), as well as social workers employed by this clinic and/or Child Protective Services (CPS). The university health system institutional review board (IRB) approved this study for research purposes. We also obtained a signed research collaboration agreement from CPS that states that the data are approved for use under the oversight of the university health system IRB.

Medical Notes

Medical notes were recorded by expert CAN medical providers during consultations at the time of the child’s medical evaluation. Notes were generated during clinic office visits and through hospital consults. When available, the notes included information that previously existed in patients’ EHR prior to the medical evaluation for maltreatment, such as previous diagnoses and hospital stays. The sources of additional information in the notes varied by case and could include any combination of responses regarding family medical and social history gathered through a semi-structured narrative interview guided by a clinic template. Questions asked during the medical evaluation included evidence-based developmental-contextual factors that have been identified as common contributors to child maltreatment. Reporters could include any combination of caregivers, social workers, and law enforcement. In addition, each clinic visit includes a diagnostic interview for any referred focal child who is over the age of three years and verbal, which begins with questions to gain an understanding of the child’s development and capability for an interview. A trained licensed clinical social worker conducts the interview using the RADAR interview technique (Recognizing Abuse Disclosure types and Responding; Everson et al., 2014) derived from the National Institute of Child Health and Development (NICHD) Investigative Interview Protocol (Lamb et al., 2007).

CPS and/or law enforcement involvement varies by case; either agency may or may not be involved before, during, or after an evaluation takes place. In cases in which CPS and/or law enforcement request a medical evaluation be performed at the clinic, it is common that CPS and/or law enforcement have already initiated an investigation. When a child is referred from another source, such as a community provider, law enforcement and/or CPS involvement may vary at the time the child is referred. CAN providers complied with all state reporting statutes to CPS and/or law enforcement when concerns for abuse/neglect rose to a level indicated by the statute. See below for more detailed descriptions of the possible sources of information for each factor.

Episodes

We defined the unit of analysis as an episode, with each episode including all notes related to one incident of suspected maltreatment for a focal child, even if these notes related to multiple healthcare encounters. Encounters for the same medical record number that occurred within 60 days of each other were assumed to be related to the same incident. Approximately 10 percent of episodes had more than one encounter. For episodes with more than one encounter, the mean number of encounters was 2.1 (SD=0.31). The mean number of days between the first and second encounter in an episode was 21.3 days (SD=20.1). Episodes were categorized as inpatient only, inpatient with outpatient clinic follow-up, and outpatient clinic only.

Chart Abstraction Codes and Procedures

Coding Scheme Development

Using an interdisciplinary team-based approach to qualitative conceptual content analysis, the development of a codebook for chart abstraction was led by a pediatrician specializing in child abuse and neglect and a researcher with a Master of Social Work (MSW). The basic structure we used for organizing codebooks allowed for flexibility throughout the coding process that facilitates coder training (MacQueen et al., 1998). First, the researcher reviewed 100 clinic visit notes to develop initial coding themes with consultation from the child abuse pediatrician. Two additional coders then joined the researcher and pediatrician through an iterative process to identify codes for analysis to examine the occurrence of selected terms in the data. When they reached a point that no new themes were identified, the codebook was developed to specify coding decisions, alleviate ambiguity, and ensure inter-coder reliability.

Coder Training.

A team of 11 coders including doctoral- and masters-level researchers (n = 6), medical students (n = 4), and a research assistant (n = 1) were trained. Training included orientation to the coding manual and definitions, NVivo and REDCAP demonstrations, and completing the coding of a sample case. Following the training, to ensure consistency, each coder completed a training set of 15 cases and compared them to the “gold standard” master set coded by the researcher with an MSW and the child abuse pediatrician. Coders were required to reach greater than 90% agreement with the master set during training and review any errors with master coders before initiating abstraction of the full dataset.

Notes were initially coded in NVivo Pro databases (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018). These data were then extracted into a secure REDCap database (Harris et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2009), where coders flagged any question or potential coding discrepancy. Comments and questions captured within REDCap were addressed by the MSW, data analyst, or pediatrician as needed. The coding team met regularly to discuss any uncertainties, questions, and issues that arose, and they updated the codebook based on any decisions made. This process facilitated a better means for quantitative analysis and allowed for a comparison between coding within REDCap (Harris et al., 2019; Harris et al., 2009) and NVivo (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018). It took about 5–20 minutes to abstract a clinical note, depending on its length. In an effort to reduce any potential secondary trauma from reading reports of alleged child maltreatment, coders were asked to only code reports for a maximum of two hours per day based on recommendations for researchers to plan a workload to allow space and time in between exposure to traumatic materials (Coles et al., 2010). This restriction was also intended to promote accuracy by avoiding coding fatigue.

Analysis of Interrater Agreement

Eleven raters reviewed the same 15 clinical notes and coded each variable in a note. Then we compared the coding by each coder with a “gold standard” and calculated a Gwet’s AC1 agreement coefficient (Gwet, 2014) for each variable. We averaged the 11 coders’ Gwet’s AC1 coefficients for a variable to derive a final interrater agreement coefficient for that variable. Interrater agreement is defined as “the propensity for two or more raters to independently classify a given subject into the same predefined category” (Klein, 2018). Compared to the widely used Cohen’s Kappa coefficient (Cohen, 1960), Gwet’s AC1 statistic is less sensitive to the balance or imbalance in marginal distributions and more consistent with the proportion of agreement. This statistic accounts for both the number of rating categories and the frequency of use of each rating category by the raters. We used the -kappaetc- command in STATA 16.0 (StataCorp, 2019) to calculate this coefficient.

Results

Demographics

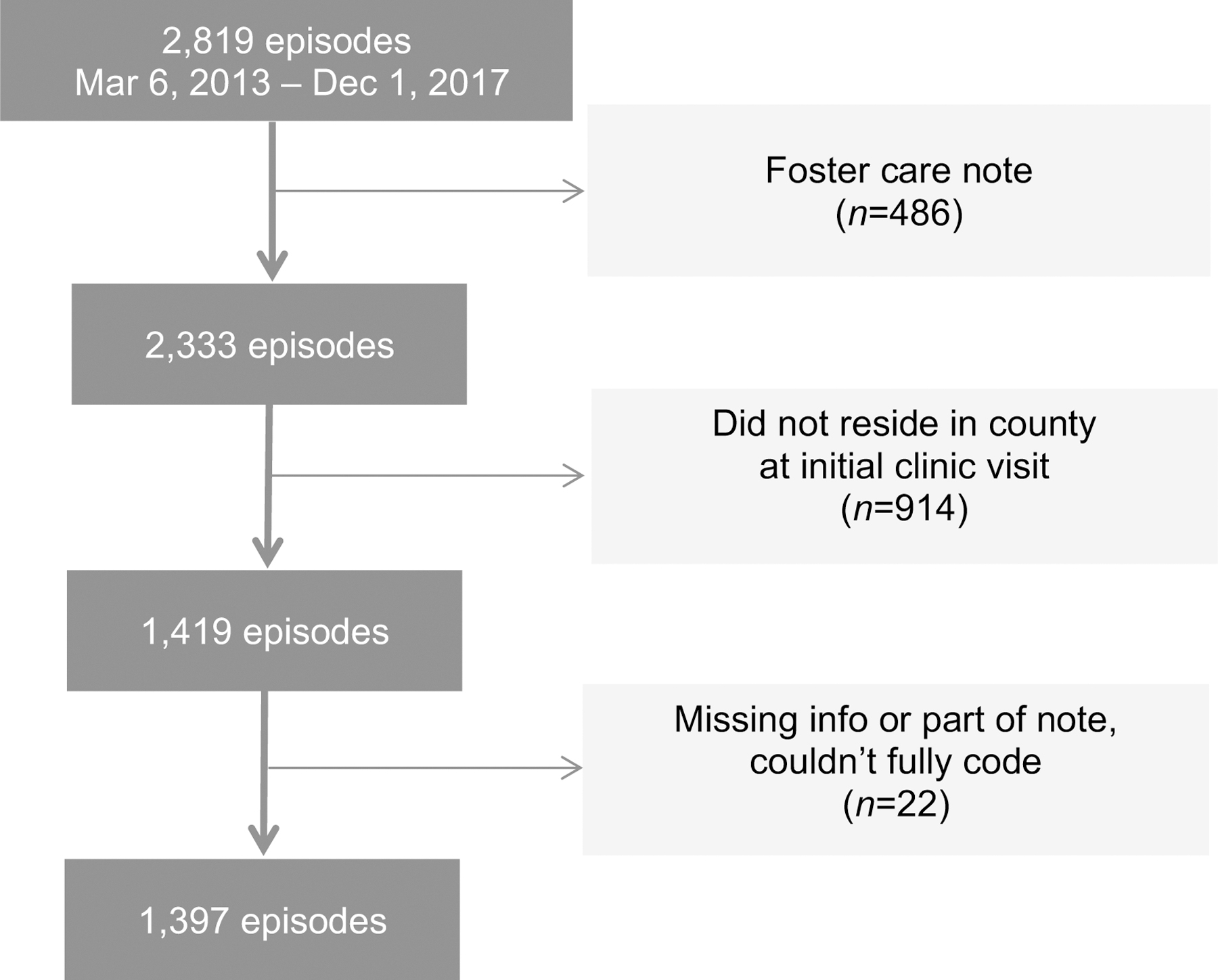

Age, sex, and race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic Black, Non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, and Other and unknown), and health insurance type (Medicaid and others) of the focal child were coded from the child’s electronic health record. Our sample included 1,397 unique identifiable children (see Figure 1 for flow diagram). Table 1 presents the distribution of child demographic characteristics. There were more girls (61.7%) than boys (38.3%). Non-Hispanic Black children were represented at a higher proportion (57.3%) than Hispanic (21.5%) or non-Hispanic White children (13.9%). The youngest children (ages 0–3) made up 27% of the sample. Most children (70.7%) were insured by Medicaid. More girls were in the 12–17 years group (80.0%) than in the other two age groups (54.4% for 0-3-year-olds and 57.5% for 4-11-year-olds). In addition, a lower percentage of children 12–17 years old (64.0%) were enrolled in Medicaid than other age groups (78.4% for 0-3-year-olds and 69.6% for 4-11-year-olds).

Figure 1.

Sample Flow Diagram

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristics | Child Total (N = 1,397) | 0–3 years (n = 375, 26.8%) | 4–11 years (n = 708, 50.7%) | 12–17 years (n = 314, 22.5%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | 0.000 | ||||

| Male | 535 (38.3) | 171 (45.6) | 301 (42.5) | 63 (20.1) | |

| Female | 862 (61.7) | 204 (54.4) | 407 (57.5) | 251 (80.0) | |

|

| |||||

| Race | 0.036 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 800 (57.3) | 219 (58.4) | 394 (55.7) | 187 (59.6) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 194 (13.9) | 64 (17.1) | 94 (13.3) | 36 (11.5) | |

| Hispanic | 300 (21.5) | 60 (16.0) | 171 (24.2) | 69 (22.0) | |

| Other and Unknown | 103 (7.4) | 32 (8.5) | 49 (6.9) | 22 (7.0) | |

|

| |||||

| Insurance type | 0.000 | ||||

| Medicaid | 988 (70.7) | 294 (78.4) | 493 (69.6) | 201 (64.0) | |

| All others | 409 (29.3) | 81 (21.6) | 215 (30.4) | 113 (36.0) | |

Note. P value for χ2 tests; percentages are in parentheses.

Codes

The averaged Gwet’s AC1 agreement coefficients for each code ranged from 0.41 to 1.00, which fell within the “moderate” to “almost perfect” agreement categories based on criteria developed by prior research (Landis & Koch, 1977). Interrater agreement coefficients for variables on social risk factors and level of clinical concerns ranged from 0.84 to 0.99. Among all the variables, over 50% were coded as not present because we collected various information from the notes, much more than we presented in this study. For example, our codes include risk factors and service placement/recommendation for siblings, family members, or others, which were mostly coded as not present, and thus had a high agreement coefficient of 1.00. However, when excluding the variables which had averaged interrater agreement coefficients of 1, among the rest of the variables, 95.6% had an averaged coefficient over 0.8 (almost perfect) and 98.8% over 0.6 (substantial). Categories that were coded for fewer than ten cases are not shown in any table to protect identifiable data as mandated by the IRB.

Referral Source

The origin of the referral was coded as Child Protective Services (CPS), law enforcement, pediatrician, emergency department, other medical provider, or other. Child Protective Services (CPS) was the most frequent referral source (56.1%), followed by the emergency department (15.8%), pediatricians (12.0%), police (10.9%), hospital referrals (7.7%), and referrals by other medical professionals (2.7%) CPS referrals were the source of over 60% of cases in each of the age groups above three years. The youngest group of children (i.e., 0–3 years of age) were more likely to be referred for evaluation by the emergency department or hospitals compared with older age groups. Descriptive statistics for these codes can be found in supplemental Table S1.

Family Risk Factors and Exposures

Exposures that could affect all members of a family/household were coded for each episode, including housing insecurity, domestic violence, parental criminal justice system involvement, parental substance use, parental mental health, and parental history of victimization/perpetration (see Table 2). The source of this information varies by case and depends on who accompanied the child to the clinic visit. It could include the caregiver, another family member, a foster parent, or CPS worker assigned to the case. When a CPS social worker is involved in the case, their notes may also be shared via consultation to provide a source of information. Overall, 75.9% of the families had at least one risk factor and almost 18% had four or more risk factors. Domestic violence was the most frequently reported risk factor across age groups, with almost half of all cases indicating a history (47.0%). Parental criminal involvement (38.1%) and parental incarceration (15.9%) also affected a substantial number of families. About 26.8% of parents had a reported mental health issue and 28.3% had reported a substance use problem. Parents had a history of victimization in about one quarter of cases (26.1%) and a history of perpetration in 9.5% of cases. Housing insecurity was a risk factor in 7.2% of cases, and 2.4% involved children’s exposure to a known sex offender. Parents of children 0–3 years old more frequently reported housing insecurity and mental health issues than parents of older children, while parents of children 4–11 years old had the highest percentages of domestic violence and criminal involvement among all the cases. The distribution of other risk factors was similar across age groups (see Supplemental Table S2).

Table 2.

Coded Risk Factors and Exposures

| Family Level Risk Factors | Code |

|---|---|

| Domestic violence | Captures focal child’s current and historical exposure to and/or experience with violence in the household |

| Housing insecurity | Captures focal child’s current and historical exposure to and/or experience with housing insecurity |

| Exposure to registered sex offender | Focal child has any exposure to a registered sex offender. Only coded in cases of suspected sexual abuse. |

| Parental incarceration | Jail, state or federal prison incarceration. This code is used when the clinician reports the person had a stay in a jail, prison, or was incarcerated. |

| Parental criminal involvement | Criminal arrests or legal charges that did not lead to incarceration |

| Parental substance use | Reports of use and misuse of substances, including alcohol. Does not include reports of possession/selling/distributing of substances. |

| Parental mental health | Reports of parent’s current and historical mental health concerns. Included all factors listed below as individual level factors, as well as post-partum depression. |

| Parental history of victimization | Reports of parent experiencing maltreatment including physical, emotional, sexual abuse, or neglect. |

| Parental history of perpetration | Report of parent abusing a child physically, emotionally, or sexually. |

| Individual Level Factors | Code |

|

| |

| ADD/ADHD | Coded for presence in the notes |

| Anxiety | Includes panic attacks. Coded for presence in the notes |

| Autism Spectrum Disorder | Coded for presence in the notes for ages 3+ years |

| Bipolar Disorder | Coded for presence in the notes |

| Depression | Coded for presence in the notes |

| Developmental delay | Coded for presence in the notes for ages 3+ years |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder | Coded for presence in the notes |

| Post-traumatic Stress Disorder | Coded for presence in the notes |

| (PTSD) | Coded for presence in the notes |

| Schizophrenia | |

| Substance use | Coded for presence of reports of use and misuse of substances, including alcohol. Does not include reports of possession/selling/distributing of substances. |

| Suicidal behavior | Acute suicidality, suicide precautions. Does not include non-suicidal self-injury. |

| Other mental health concerns | Coded for presence in the notes when clinician reports mental health concerns but does not specify the exact nature of the concern. This code may be used concurrently with specific mental health concerns. |

Individual Mental Health Risk Factors

Mental health disorders were based on clinical notes for the presence of more than 12 types of psychological disorders such as anxiety and depression. For the focal child, mental health diagnoses and substance use could appear as a known diagnosis found in the medical chart, or provided by another professional, or could also be a non-confirmed diagnosis reported by a caregiver. Risk factors were coded as “present” if the above definitions were met by the focal child. See Table 2 for a list of the individual factors coded for the focal child. ADD/ADHD was the most common problem reported for children (10.6%), followed by other mental health concerns (10.4%) and depression (5.9%). Around 27.0% of children had experienced at least one risk factor and 2.7% had four or more risk factors. Children 0–3 years old rarely had documented individual level risk factors, and children 12–17 years old had the highest percentage for all individual risk factors among the three age groups (Supplemental Table S3 presents descriptive statistics for these codes).

Child Protective Services (CPS) Involvement

Notes indicated the focal child’s current or past involvement in CPS, including foster care or kinship care. CPS involvement may be indicated by the referral source, and/or reports from CPS workers. While CAN medical providers do not have access to the CPS system or their ongoing notes, any existing CPS intake reports may be provided along with referral, and CPS workers may provide information via phone or in-person interview. Over half of the children in our sample had an open CPS case that did not involve out-of-home placement at the time of their medical evaluation for maltreatment. About 7.3 percent and 4.8 percent of total cases involved children who were in foster care or kinship care at the time of their evaluation, respectively. Six percent of the children had a history of prior foster or kinship care. Nearly one-third of the children (31.4%) had a prior CPS history other than foster or kinship care. Compared to younger children, older children were more likely to have been in foster care or had a prior CPS history. Descriptive statistics for these codes can be found in Supplemental Table S4.

Parenting Practices

Caregivers reported on the methods they use when disciplining their children. Removal of privileges was the most frequently used parenting strategy (44.1%), followed by physical discipline (32.1%) and time out (25.4%). Physical discipline (42.9%) and time out (35.3%) were most frequently used among 4-11-year-olds, while removal of privileges (59.5%) was mostly used among the 12-17-year-olds. Descriptive statistics for these codes can be found in Supplemental Table S5.

Maltreatment Type

The CAN clinic identifies all types of child maltreatment. This includes physical abuse, neglect, medical neglect, and emotional abuse. It also encompasses maltreatment that is sexual in nature. Sex-related maltreatment can be further specified as abuse, assault, exploration, and victimization.

Level of Clinical Concern

The role of the CAN medical evaluation clinic is to provide a medical evaluation for children referred for concerns of abuse or neglect. Medical diagnoses, conclusions, and recommendations made for children referred to the clinic are based on the information available at the time of evaluation. Thus, the terminology used for medical conclusions and the guidelines used to determine these conclusions are based on clinical information and scientific data in the field of child abuse and neglect, and do not constitute or equate to legal terminology or conclusions regarding abuse/neglect. The diagnostic categories do not include any custody determinations, which are done by legal entities. The CAN specialty clinic performs a multidisciplinary case conference to peer review each evaluation and determine a diagnosis that describes a level of concern of maltreatment for the child. The CAN medical team, which includes child abuse pediatricians, licensed clinical social workers, and a team nurse practitioner, gathers weekly to discuss important details and determine a medical diagnosis. The goal of case review is to decrease bias and improve standardization of diagnoses. The CAN clinic team uses six levels of medical concern for cases referred for evaluation: clear and confirmed, probable, suspicious, unlikely, unknown, and no concern. Levels of concern are guidelines to promote consistency and high-quality medical evaluations. These guidelines also help inform adherence to mandatory reporting statutes and consistency of medical recommendations. Since they are guidelines, there may be variations depending on individual circumstances. Table 3 displays the diagnostic levels of clinical concern for physical abuse, neglect, and sex-related abuse with brief descriptions of each level. This table is a condensed form of a more complex document used during case review. Supplemental Table S6 presents descriptive statistics for the highest level of clinical concern overall and by type of maltreatment across age groups.

Table 3.

Levels of Clinical Concern Guidelines

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Clear and confirmed | Case history includes verified medical findings of abuse/neglect. |

| Probable | Case history includes information leading to high level of medical concern for possible abuse/neglect of the child. |

| Suspicious | Case history includes information which is medically concerning for abuse/neglect. However, there are factors which limit the ability to raise the level of concern. |

| Unknown | Case history includes information which cannot rule out the possibility of abuse/neglect, and where there are factors that may leave a child at risk for abuse/neglect. |

| Unlikely | Case history includes information which leads to low concern for abuse/neglect. |

| No concern | Case history includes information that leads to no significant medical concern for abuse/neglect. |

Overall, 27.4% of the cases in the sample were classified as “clear and confirmed” maltreatment, and only 5.8% were classified as “unlikely or no” for maltreatment. Children 12–17 years old had the highest percentage evaluated as “clear and confirmed” (35.7%) or “probable” (29.3%), and children 0–3 years old had the highest percentage for “unknown” (32.0%) or “unlikely or no” (9.6%) across age groups.

Physical Abuse.

About 44.3% of the total sample was evaluated for physical abuse, with the youngest children (0–3 years of age) evaluated for physical abuse more frequently than children in older age groups (59.7% of 0-3-year-olds, 39.4% of 4-11-year-olds, and 36.9% of 12-17-year-olds) (see Supplemental Table S5). Among cases evaluated for physical abuse, 21.5% were classified as “clear and confirmed,” with an additional 10.8% classified as “probable,” 29.1% as “suspicious,” and 33.3% as “unknown.” Only 5.3% of cases were deemed to be “unlikely or no.” Proportions of “clear and confirmed” assessments were fairly consistent across age groups but highest for 12-17-year-olds (31.0%). “Suspicious,” “unknown,” and “unlikely or no” conclusions generally decreased with increasing age of the focal child.

Neglect.

Approximately 35.1% of our sample was evaluated for neglect. Over half of the youngest children received evaluations for neglect (51.7%), which was higher than the evaluated older age groups (30.8% for 4–11 and 35.1% for 12–17). Overall, 30.8% of cases evaluated for neglect were assessed as “clear and confirmed” for neglect. Children 0–3 years of age had the highest proportions for “unknown” or “unlikely or no” neglect compared with older age groups.

Sex-related Abuse.

Sexual abuse/assault/exploitation/victimization was evaluated in nearly 60% of all cases, making it the most prevalent form of abuse evaluated in our sample. The youngest children were the group least commonly evaluated for sex-related abuses (35.2% of 0-3-year-olds), while over 70% of the 12-17-year-olds in the sample were evaluated for sex-related abuse. Overall, 15.1% of cases evaluated for sex-related abuse were found “clear and confirmed,” 32.8% were deemed “unknown,” and 7.0% “unlikely or no.” “Clear and confirmed,” “probable,” and “suspicious” cases increased with age, while “unknown” cases tended to decrease with age.

Medical Neglect and Emotional Abuse.

Evaluation of medical neglect and emotional abuse was uncommon, with each coded in fewer than 4% of total cases. About 35.3% of cases evaluated for medical neglect were labeled “clear and confirmed,” and 43.1% “suspicious.” For emotional neglect, 55.9% of cases were deemed “suspicious.” All other cell sizes for medical neglect and emotional abuse were fewer than 11, thus, we are unable to assess age differences.

Recommendations

This code indicates whether families received recommendations for additional services from which the focal child or family members may benefit following the focal child’s CAN clinic visit. CAN medical providers may recommend multiple services for the same individual, so all recommendations were coded separately for both focal child and other individual family members. Codes in this category include therapeutic trauma-informed mental health services, CPS report, developmental evaluation, domestic violence counseling, individualized education plan (IEP), parenting classes, parenting coordinator, parent-child interaction therapy, speech assessment, substance abuse counseling, and other. See Table 4 for descriptions of each recommendation code. General mental health service was the most common service recommendation for focal children (42.9%). Therapeutic trauma-informed mental health service was the next most common recommendation (22.6%). Eight percent of children were referred for child-family evaluations, followed by “other” recommendations (9.2%), such as referral to a subspecialty provider. Adolescents 12–17 years of age were more frequently referred for therapeutic trauma-informed mental health services, CPS reports, and general mental health services than children in the younger age groups. Children 0–3 years of age were more likely to be recommended to developmental evaluation and speech assessment compared to children in older age groups (See Supplemental Table S7).

Table 4.

CAN Provider Recommendation Codes

| Service Recommendations | Description |

|---|---|

| Therapeutic trauma-informed mental health services | Specialized services provided by an expert who is certified/licensed in specific trauma therapy techniques, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy |

| Child-Family Evaluation | Brief, specialized forensic evaluation in cases that have not been determined through the standard CPS investigation or CME. |

| Child Medical Evaluation | Recommend a medical consultation performed by a qualified medical expert rostered with the state Child Medical Evaluation Program to assist with determining the most appropriate medical diagnoses and treatment plan for a child when it is suspected that child is being abused or neglected by a caretaker. Usually recommended for siblings or other children in the home. |

| CPS report | File a report with CPS if one has not already been filed. |

| Developmental evaluation | Assessment of various aspects of the focal child’s functioning, including areas such as cognition, communication, behavior, social interaction, motor and sensory abilities, and adaptive skills. |

| Domestic violence counseling | Specialized counseling/therapy from a qualified professional who has training and experience treating individuals who experience(d) intimate partner violence. |

| General mental health services | Any mental health services provided by a licensed provider for a specific age group. |

| Individual Education Program (IEP) | Coordinating with a team of individuals from various educational disciplines to create a plan to ensure that a child with an identified disability receives specialized instruction and services. |

| Parenting coordinator | A neutral third-party who helps parents involved in high-conflict custody cases make day-to-day decisions |

| Parent Child Interaction Therapy | Evidence-based behavior parent training treatment for young children with emotional and behavioral disorders. PCIT places emphasis on improving the quality of the parent-child relationship and changing parent-child interaction patterns. |

| Speech assessment | Recommend assessment to establish whether a child has any specific speech, language, or potential communication disorders. |

| Substance abuse counseling | Services provided by a qualified professional trained and experienced in providing support to patients suffering from drug or alcohol dependency and educating families in the best ways to help in the recovery process. |

| Other | Recommendations that do not have an existing recommendation code |

Discussion

Child abuse and neglect medical providers who perform medical evaluations assess multiple factors across multiple contextual levels and conduct multi-disciplinary peer review of cases to determine the level of clinical concern for maltreatment. In this study, we report the development of a coding system to extract information from child abuse and neglect medical evaluation clinic notes. Using the system developed by an interdisciplinary team to capture individual and family-level risk factors, our coders’ agreement coefficients were moderate to high overall, ranging from 0.41 to 1.00. This study demonstrates the development and implementation of the coding system and highlights the potential value of extracting variables to assess case characteristics and patterns from medical provider notes. Data collected in this manner, while effortful and time-consuming, can provide a better understanding of child maltreatment incidence, the associated risk factors, and service provision in the medical settings, and inform future research about the feasibility of using such information in child maltreatment prevention and treatment.

Assessing aggregate information coded from medical provider notes provides a useful overview of trends in cases evaluated for child abuse and neglect, as demonstrated by previously published studies that have similarly extracted information from child abuse pediatrician (CAP) case notes. Coded data have been used by researchers to identify different notetaking approaches used by CAPs (Keenan & Campbell, 2015), to provide descriptive data on the incidence of child abuse and neglect cases and subsequent interventions in the Netherlands (Teeuw et al., 2017), to investigate legal consequences of child abuse (Hendrix et al., 2020), and to describe medical consultations by CAPs in a hospital setting in the U.S. (Hicks et al., 2020; Johnson et al., 2021). While previous studies were conducted primarily by medical professionals, our interdisciplinary team included diverse perspectives from researchers in health policy, public health, social work, and developmental psychology, in addition to medical providers. Our study builds upon previous work by including a substantial number of adolescent cases, taking a developmental-contextual risk and resilience approach, and including measures of cumulative risk at the individual and family level. In addition, this is the first study, to our knowledge, that includes detailed information on the development and implementation of the coding system used to extract data from CAN medical evaluation notes. We hope that by documenting our process and the coding materials, it will enable future research teams to use these methods and reduce costs and time for conducting related research.

Like previous studies in the U.S., the expert panel of CAN medical providers in the current study rated fewer than half of total referred cases as clear and confirmed or probable for any type of maltreatment. The overall proportion of confirmed/probable cases in our study (33%) was slightly lower than a previous study of a hospital-based child abuse pediatrics consultation service that rated 40% of nonsexual abuse cases as “definite/likely abuse” (Hicks et. al., 2020). Another study examined child maltreatment allegations from a child advocacy center whose multidisciplinary team included a child abuse pediatrician and found that 28% of cases evaluated received a clinical diagnosis of child maltreatment (Hendrix et al., 2020). Variability across different medical centers in terms of percentage of cases assessed to have a low versus high likelihood of abuse has been previously documented, as potential reasons for this variability are discussed by Johnson et al. (2022). In the current study, there were very few cases assessing medical neglect or emotional abuse, which were not examined in the studies above.

To situate our findings in a developmental-contextual framework (Belsky, 1993), we presented the results by age group (0-3-year-olds, 4-11-year-olds, and 12-17-year-old adolescents.) We found that relative to older children in our sample, a higher proportion (over half) of children aged 0–3 years were evaluated for physical abuse and neglect, whereas fewer than half of the children in the older groups were evaluated for these types of maltreatment. Notes for young children also documented several risk factors, such as housing insecurity and mental health issues, at proportions higher than those observed among older children. The youngest children also had the highest percentages for a clinical concern of “unknown” or “unlikely or no” across all types of maltreatment. Children under age four are particularly vulnerable to experiencing maltreatment as they rely on caregivers to provide nearly all their needs (Conrad‐Hiebner et al., 2019). Young children are unable to protect themselves and are largely unable to communicate concerns of physical injuries or neglect to an adult. Thus, young children represent a disproportionate percentage of victims and a unique population for early identification and prevention of maltreatment efforts. On the other hand, the adolescents in the 12–17 age group were evaluated most frequently for sex-related abuse and had the highest proportions of clear and confirmed sex-related abuse. This mirrors research indicating that the risk of child sexual abuse increases with age, particularly in adolescence (Putnam, 2003), with a rise in victimization with each additional year from 15 to 17 (Finkelhor et al., 2014). Further, unlike young children, adolescents can vocalize concerns, and to some extent, advocate for their own needs.

Most of the individual-level risk factors coded from medical providers’ notes did not apply to the children under age four (e.g., ADHD, anxiety, depression, substance use). Individual risk factors were most commonly coded for adolescents. One in five adolescents had a reported diagnosis of ADHD, which is higher than the 13.6% national prevalence for 12-17-year-olds (Danielson et al., 2021). Depression and anxiety typically increase with age (Ghandour et al., 2019), and the prevalence of depression (20%) in our adolescent sample is much higher than that in the general population of children (4.9%) aged 6–17 years (Bitsko et al., 2018). Further, anxiety has usually been found to be more prevalent than depression (Bitsko et al., 2018; Ghandour et al., 2019), while we found contrary results. Sixteen percent of adolescents’ case notes also mentioned suicidal behavior. Overall, the 12-17-year-old group had the greatest number of individual risk factors. Future research should focus on adolescence as a particular time of mental health risks among those who have experienced maltreatment.

Family-level risk factors were less dependent on a child’s age than child-level risk factors. We found that almost half (47%) of all children had a history of domestic violence in the home. Parental history of victimization, parent mental health issues, and parent substance use were risk factors present in about a quarter of cases. The notes documented multiple family risk factors more often than individual factors. Consistent with prior studies, cases with a high concern for maltreatment often presented with family-level risk factors, including a history of experiencing domestic violence, parental mental health issues, parental history of victimization, and parental substance use (Coulter & Mercado-Crespo, 2015; Dubowitz et al., 2011; Kelley et al., 2015; Victor et al., 2018). These risk factors often co-occur in a family and may cumulatively contribute to children’s adverse outcomes (Horwitz et al., 2011; Patwardhan et al., 2017).

An understanding of the contextual information related to potential incidents of abuse or neglect is crucial when researching, diagnosing, and treating child maltreatment. It is important to note, however, that there is some evidence that inclusion of social information may influence medical diagnosis in child maltreatment cases. Keenan et al. (2017) found that the presence of social risk factors when evaluating injuries influenced child abuse consultants’ diagnosis of abuse among poor and minority children, especially in ambiguous cases. Similarly, Olson et al. (2018) found that child abuse clinicians’ consultation notes detail a rich social history that includes many domains of the child and families’ social ecology; however, information recorded was not always related to known population risk indicators (e.g., negative impression of caregivers). In both studies the authors suggested that uniform reporting styles and tools such as checklists and peer review show promise in minimizing bias, but continued research is warranted to understand how child abuse medical providers use information on patients’ social history and circumstances to understand and document their findings. In our study, non-Hispanic Black children were disproportionately represented in referrals to the clinic, and future research should investigate underlying reasons for this disproportionality with an eye toward understanding if and how implicit biases and systemic inequities may be driving these patterns. CAN medical providers conducted multidisciplinary case conferences for peer review on each evaluation, which should help reduce bias in diagnoses by standardizing the process for all patients. Examining CAN medical providers’ notes through qualitative data mining may aid the development of a best practice model for managing and documenting child abuse and neglect consultations, including reduction of bias.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, data were from only one clinical setting. Because the process whereby medical providers take family history may differ across practice settings (Johnson et al., 2021), the available information may differ by clinician. Second, the information gathered relied on intake interviews between providers and caregivers or children, and thus depended on the quality of communication and documentation in medical consultation notes. This may be subject to respondents’ willingness to share and their awareness of the child’s exposures. Thus, the absence of documented recording of social histories (e.g., history of parental childhood victimization, use of physical discipline, etc.) does not necessarily indicate the child’s family did not experience certain adversities. Third, the timing of an issue (historical and/or ongoing) and the exact nature of how affected a child was by various adversities were unclear. For example, a parent may have substance use issues and may vary in the amount of contact with the child. Similarly, a parent may have varying levels of criminal involvement—which vary in how it affects the child’s environment. Finally, a limitation is that the clinical concern guidelines used by the CAN medical providers in this study have not been validated. The guidelines are used to guide the provision of care and resources, to facilitate discussion to mitigate bias and be consistent, and as internal continuous quality improvement, but validity testing has not yet been done.

Conclusions

Hand coding notes from child abuse and neglect clinic evaluations revealed information that medical providers may use to inform their care of children, and which may be amenable to service provision, including caregiver needs and behaviors (e.g., substance use, mental health, parenting style) and family factors (e.g., criminal involvement, housing insecurity) that are risks for maltreatment (Hunter & Flores, 2021). Medical systems can work with families and community partners to address social drivers of health and risk factors for experiencing maltreatment, although we must take care not to conflate family needs and risk factors with child maltreatment (Keenan et al., 2017).

Child abuse pediatricians and other medical providers working with children and families should consider upgrading their documentation to include flowsheets or data input areas that facilitate data extraction. Research should continue to examine how medical providers use this information, with a priority to reducing any biases. Framing these data within a developmental-contextual lens has potential to promote partnership between health systems, community partners, and families. In aggregate, this information might inform the underlying needs of families and better position communities and health care systems to address them.

Supplementary Material

Funding/Support:

This study was supported by The Duke Endowment, ABC Thrive Bass Connections, and the Translating Duke Health Children’s Health and Discovery Initiative

Role of Funder/Sponsor:

None of the funders had any role in the design or conduct of this study.

Footnotes

Declarations of interest: None

References

- Belsky J (1993). Etiology of child maltreatment: A developmental-ecological analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 114(3), 413–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Ghandour RM, Blumberg SJ, Visser SN, Perou R, & Walkup JT (2018). Epidemiology and impact of health care provider–diagnosed anxiety and depression among US children. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 39(5), 395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block RW, & Palusci VJ (2006). Child abuse pediatrics: A new pediatric subspecialty. The Journal of Pediatrics, 148(6), 711–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Preventing Child Abuse & Neglect Retrieved November 3, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/fastfact.html

- Cohen J (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 20(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Coles J, Dartnall E, Limjerwala S, S. & Astbury J (2010). Briefing paper: Researcher trauma, safety and sexual violence research. Sexual Violence Research Initiative

- Conrad‐Hiebner A, Wallio S, Schoemann A, & Sprague‐Jones J (2019). The impact of child and parental age on protective factors against child maltreatment. Child & Family Social Work, 24(2), 264–274. [Google Scholar]

- Coulter ML, & Mercado-Crespo MC (2015). Co-occurrence of intimate partner violence and child maltreatment: Service providers’ perceptions. Journal of Family Violence, 30(2), 255–262. [Google Scholar]

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Holbrook JR, Charania SN, Claussen AH, McKeown RE, … Kubicek L (2021). Community-based prevalence of externalizing and internalizing disorders among school-aged children and adolescents in four geographically dispersed school districts in the United States. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 52(3), 500–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubowitz H, Kim J, Black MM, Weisbart C, Semiatin J, & Magder LS (2011). Identifying children at high risk for a child maltreatment report. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(2), 96–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson M, Ragsdale C, & Snider S (2014). RADAR: Child Forensic Interview Pocket Guide Chapel Hill: North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys. [Google Scholar]

- Finkelhor D, Shattuck A, Turner HA, & Hamby SL (2014). The lifetime prevalence of child sexual abuse and sexual assault assessed in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(3), 329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, Ali MM, Lynch SE, Bitsko RH, & Blumberg SJ (2019). Prevalence and treatment of depression, anxiety, and conduct problems in US children. The Journal of Pediatrics, 206, 256–267. e253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwet KL (2014). Handbook of inter-rater reliability: The definitive guide to measuring the extent of agreement among raters Gaithersburg, MD: Advanced Analytics, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L, … Kirby J (2019). The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 95, 103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, & Conde JG (2009). Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 42(2), 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrix AD, Conway LK, & Baxter MA (2020). Legal outcomes of suspected maltreatment cases evaluated by a child abuse pediatrician as part of a multidisciplinary team investigation. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 65(5), 1517–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herold B, Claire KS, Snider S, & Narayan A (2018). Integration of the nurse practitioner into your child abuse team. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 32(3), 313–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks RA, Laskey AL, Harris TL, & Hibbard RA (2020). Consultations in child abuse pediatrics. Clinical Pediatrics, 59(8), 809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz SM, Hurlburt MS, Cohen SD, Zhang J, & Landsverk J (2011). Predictors of placement for children who initially remained in their homes after an investigation for abuse or neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(3), 188–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter AA, & Flores G (2021). Social determinants of health and child maltreatment: A systematic review. Pediatric Research, 89(2), 269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KL, Brown EC, Feldman KW, Qu P, Lindberg DM, & Investigators E (2022). Child abuse pediatricians assess a low likelihood of abuse in half of 2890 physical abuse consults. Child Maltreatment, 10775595211041974. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Keenan HT, & Campbell KA (2015). Three models of child abuse consultations: A qualitative study of inpatient child abuse consultation notes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 53–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan HT, Cook LJ, Olson LM, Bardsley T, & Campbell KA (2017). Social intuition and social information in physical child abuse evaluation and diagnosis. Pediatrics, 140(5): e20171188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Lawrence HR, Milletich RJ, Hollis BF, & Henson JM (2015). Modeling risk for child abuse and harsh parenting in families with depressed and substance-abusing parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 43, 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein D (2018). Implementing a general framework for assessing interrater agreement in stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 18(4), 871–901. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb M, Orbach Y, Hershkowitz I, Esplin P, & Horowitz D (2007). A structured forensic interview protocol improves the quality and informativeness of investigative interviews with children: A review of research using the NICHD Investigative Interview Protocol. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 1201–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, & Koch GG (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen KM, McLellan E, Kay K, & Milstein B (1998). Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. CAM Journal, 10(2), 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Olson LM, Campbell KA, Cook L, & Keenan HT (2018). Social history: A qualitative analysis of child abuse pediatricians’ consultation notes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 86, 267–277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan I, Hurley KD, Thompson RW, Mason WA, & Ringle JL (2017). Child maltreatment as a function of cumulative family risk: Findings from the intensive family preservation program. Child Abuse & Neglect, 70, 92–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Putnam FW (2003). Ten-year research update review: Child sexual abuse. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 42(3), 269–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12) [Computer software] In https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- StataCorp. (2019). Stata Statistical Software: Release 16 [Computer software] In https://www.stata.com

- Teeuw AH, Sieswerda‐Hoogendoorn T, Aaftink D, Burgers IA, Vrolijk‐Bosschaart TF, Brilleslijper‐Kater SN, … van Rijn RR (2017). Assessments carried out by a child abuse and neglect team in an Amsterdam teaching hospital led to interventions in most of the reported cases. Acta Paediatrica, 106(7), 1118–1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. (2022). Child Maltreatment 2020 https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/data-research/child-maltreatment.

- Victor BG, Grogan-Kaylor A, Ryan JP, Perron BE, & Gilbert TT (2018). Domestic violence, parental substance misuse and the decision to substantiate child maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect, 79, 31–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.