Abstract

Environmental Justice (EJ) communities may experience barriers that can prevent soil monitoring efforts and knowledge transfer. To address this gap, this study compared two analytical methods: portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (pXRF, less time and costs) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS, “gold standard”). Surface soil samples were collected from yards and gardens in three counties in Arizona, USA (N=124) and public areas in Troy, New York, USA (N=33). Statistical calculations, i.e., two-sample t-tests, Bland-Altman plots, and a two-way ANOVA indicated no significant difference for As, Ba, Ca, Cu, Mn, Pb, and Zn concentrations except for Ba in the two-sample t-test. Iron, Ni, Cr, and K were statistically different for Arizona soils and V, Ni, Fe and Al concentrations were statistically different for New York soils. To assess the degree of contamination, a pollution load index (PLI), enrichment factors (EF), and geo-accumulation index () were calculated for both methods using U.S. Geological Survey soils data. The PLI were >1, indicating pollution across the two states. Between pXRF and ICP-MS, the and EF in Arizona had similar degree of soil contamination for most elements except Zn in garden and Pb in yard, respectively. In New York, the of As, Cu, and Zn differed by an order of magnitude between the two methods. The results of this study demonstrate that pXRF is a reliable method for the inexpensive and rapid analysis of As, Ba, Ca, Cu, Mn, Pb, and Zn. Thus, EJ communities may use pXRF to screen large numbers of soil samples for several environmentally relevant contaminants to protect environmental public health.

Keywords: Metal(loid)s, Portable X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (pXRF), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), Pollution load index, Enrichment factor, Geo-accumulation index, Soil monitoring

1. Introduction

Urbanization and industrial activities have increased the amounts of released contaminants and potential exposure routes for communities. These contaminants can accumulate in soil and impact human and ecological health. Mining for example, provides society with needed elements, but also serves as a primary source of heavy metal (HM) pollution (Fashola et al., 2016; Zhuang et al., 2009). In mineral-rich areas the soil environment may be naturally rich in or become a repository of inorganic contaminants diffused and emitted from nearby mining activities (Tepanosyan, et al., 2018). Exposure to heavy metals and metalloids can cause chronic health problems at low concentrations (Wragg, 2013; Haidar et al., 2023), such as learning disabilities, kidney dysfunction, endocrine disruption, and damage the nervous system (Gorini et al., 2014; Paschoalini et al., 2019). Arsenic, Cr and Ni are categorized as carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, and Pb as a probable carcinogen (Kim et al., 2015; U.S.EPA IRIS, 2021, U.S.EPA IRIS, 2022); exposure to any concentration of Pb is unsafe (World Health Organization, 2019). Heavy metal exposure threatens humans, animals, and the ecosystems; HM are taken up by crops, ingested, and can bioaccumulate over time in organisms (Gitet et al., 2016), leading to behavioral disruption, infertility problems, and in severe cases, death (Hejna et al., 2018). In addition, metal(loid)s alter soil microbial communities and reduce vegetative coverage in terrestrial ecosystems by causing morphological abnormalities in plants (Tiwari & Lata, 2018; Amari et al., 2017) and limiting the microbial metabolism (Wang et al., 2020). Rural and urban communities have initiated agri-food systems like organic farming to maintain a sustainable food source (Measham, 2010) and use regional resources such as soil, land, and water. Therefore, the concerns about mining activities impacting food safety have increased because HM accumulation jeopardizes rural soils and the well-being of local and indigenous communities living nearby mining sites (Haddaway et al., 2019; Gibson & Klinck, 2005). To protect ecosystem and human health, an affordable monitoring technique is needed to detect metal(loid) concentrations in areas impacted by industrial and resource extraction waste sites.

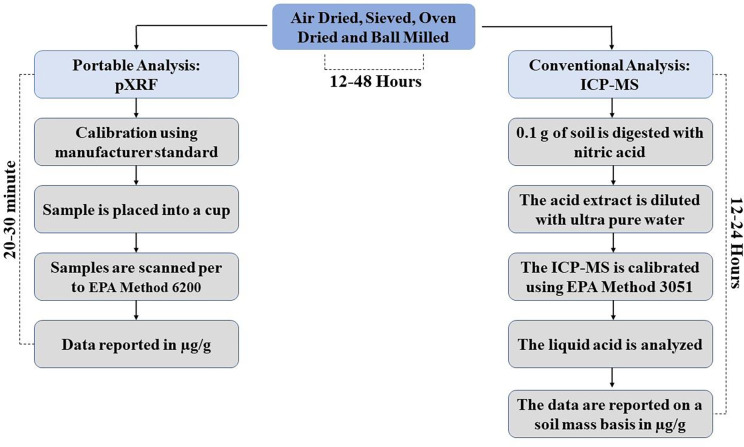

Due to cost, time, and access, currently, “gold standard” metal(oid)s soil methods of analysis are generally not available (Marguí, et al., 2013), especially to those who need it most. These methodologies include a lengthy acid digestion process and analysis via flame atomic absorption spectroscopy (FAAS), inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometry (ICP-OES), and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (Figure 1). A low-cost alternative is the portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF), which has proven to be a multi-elemental technique that can be applied in-situ with minimally processed samples to delineate heavily contaminated zones (Weindorf et al., 2013). Although the pXRF offers a rapid, lower-cost tool to screen soil and sediments for metal(loid)s; how does it compare to the laboratory “gold standards? As a case in point, the Center for Disease Control’s Agency for Toxic Substances (ATSDR) recommends using a pXRF for Soil Screening, Health, Outreach, and Partnership (soilSHOP) events designed to provide community members with free soil screenings (ATSDR, n.d.), but currently only recommends using the pXRF for lead. This is a missed opportunity to identify other possible soil contaminants and protect community health.

Figure 1.

Soil Sample preparation and analysis comparison between pXRF and conventional analyses of ICP-MS. Note with ICP-MS, laboratory wait time and data report back to end-user will add additional time.

This study aims to assess whether the pXRF can serve as a reliable instrument to accurately determine lead, arsenic and other heavy metal concentrations in residential soils. Soils metal(loid) concentrations measured by ICP-MS and pXRF were statistically compared to determine the pXRF reliability in environmental assessments and provide an alternative detection method from the costly chemical analysis. Therefore, the insights gained from this comparison will provide a deeper understanding of the pXRF’s performance and reliability to serve as a tool for local communities to improve human and soil health.

2. Methods

2.1. Study and site description

This study is part of the University of Arizona Gardenroots project (https://gardenroots.arizona.edu/), which assesses residential environmental quality of communities neighboring resource extraction activities through a co-created citizen/community science design (Ramírez-Andreotta et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2015; Sandhaus et al., 2019; Manjón et al., 2020; Zeider et al., 2023). The research focuses on three counties in Arizona, USA, which are Apache, Cochise, and Greenlee, and the city of Troy in New York, USA.

Over 90 local community members were trained on how to properly collect garden and yard soil samples and 124 soil samples were submitted by Arizona community members. Arizona has nine abandoned hazardous or uncontrolled Superfund sites recognized as National Priorities List (NPL) by the U.S.EPA (Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, ADEQ, 2022). Apache and Greenlee do not have any superfund sites; however, they are home to 12 active mines (Richardson et al., 2019). The largest copper mining operation in North America is the Morenci mine in Greenlee County. The surrounding area is known to have high concentration of As, Cr, Cu, Pb, Mn, and Ni (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2020). The Apache, Cochise, and Greenlee counties are rural communities and have a population of 65,623, 126,050, and 9,404, respectively (U.S. Census Bureau, 2019). The percentage of individual older than 65 in Apache (16.9%,), Cochise (23.8%), and Greenlee (12.9%) and the poverty per person in Apache and Cochise is higher than the national poverty rate in the USA at 28.4% and 17.1%, respectively (Census Bureau, 2022a; 2019; U.S. Census Bureau, 2022b; 2019; U.S. Census Bureau, 2022c). Apache has an annual precipitation of 10.55 inches and a mean annual temperature of 52 °F; Cochise receives 14 inches of precipitation per year with an annual average temperature of 63.1 °F; Greenlee has a mean annual rain of 16 inches and an average annual temperature of 59 °F (NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, 2022).

Thirty-three soil samples were collected from Troy, New York. Troy is considered an urban city with a population of 50,760 (Census Bureau, 2021). The city has an annual rain and a mean temperature of 41 inches and 47 °F, respectively. Although there is no mining project nearby the city, still, many superfund sites were recognized by the U.S.EPA in Albany County such C&F Plating Company, Inc., which highlights the predicament of having potential released contaminants such copper in the region (U.S.EPA, n.d.c). In this context, Troy has high potential exposure to lead paint coming from housing units built before 1960; medium to high potential chemical accident management plan in some part of the city; high hazardous waste proximity which account to hazardous waste facilities in a 5 km radius (U.S.EPA, 2015).

2.2. Soil collection and field sampling

The Gardenroots participants were trained in sample collection protocols from their gardens and yards; the first is described as an area used to grow edible and ornamental plants, whereas yard is considered as native and unamended land where children’s practice physical activity and outdoor play. The participants picked six sampling spots arranged as a grid pattern in the garden area, close to growing spots of vegetables and other edible plants. The topsoil layer (6 inches) was loosened, homogenized, and then placed in a labeled 2-gallon bucket. The samples were mixed thoroughly in the bucket and separated into two labeled brown papers with the participant number and date of collection, then placed in a plastic bag (Zip bag). The participants chose the spots where they often play or walk for the yard samples. For yard soils, the same procedure was applied, using a different bucket. All samples were stored in a refrigerator immediately after collection, then transferred with dry ice into an insulated foam kit to process for expedited shipping. The same procedure was followed to collect soil samples from Troy, New York.

2.3. Soil pH and texture analysis

All soil samples from Troy, New York were analyzed for particle size and pH. A fisher XL-20 meter was used to measure pH value after calibration with three buffer values of 4,7, and 10. The procedure starts by adding 10 grams of dried soil from each sample into the vial that has 20 millimeters of 18 Mega ohm water. The vials were placed in the shaker for 30 minutes. The electrode prob was placed into the stirring samples (approximately 2 cm deep) to measure the pH. Throughout the process, the prob was rinsed and recalibrated after every 5 measurements. To determine sand, silt and clay size fractions in soils, the hydrometer method and triangle of textural classification were applied as per the USDA soil classification system (USDA, 1999).

2.4. ICP-MS Soil Analysis

All samples were air-dried for 24–96 hours, sieved to 2 mm diameter, then oven-dried for a constant mass at 105°C (VWR, gravity convection oven), ball milled to 80–100 μm (SPEX SamplePrep, 8000D), and stored in paper envelopes until analyzed. Each sample went through a microwave acid digestion process using the modified method of U.S. EPA Method 3051; 1 ml of concentrated nitric acid (Omni race HNO3, EMD Chemicals) was reacted with 0.1 g of the sieved soil for one hour at room temperature, then 1 mL of ultrapure water (18 MOhm) was added. The samples were sealed to run at high pressure and temperature via microwave digestion (CEM Model MARS6 microwave, Matthews, North Carolina). Each batch had a National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST SRM 2711a Montana II soil) control sample. ICP-MS quantifiable detection limits for each element are provided in Table 1. Arizona soil samples were analyzed for Be, Na, Mg, Al, K, Ca, Ti, Mn, Cu, Co, Zn, As, Pb, Cr, Se, Mo, Ag, Cd, Sn; and New York soil samples for As, Ni, V, Cu, Cr, Al, Fe, Zn, Pb, and Mn. Moreover, concentrations below the detection limit were considered equal to half the method detection limit in reporting the soil elemental content.

Table 1.

Limits of detection for pXRF (DELTA Premium, DP-6000) and ICP-MS (ppm/µg g−1). The ICP-MS methodological limit of detection (MDL) for each element was calculated based on the instrument detection limit after applying the dilution factor.

| pXRF * | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Element | As | Ni | Ca | Cu | Cr | Ba | Fe | K | Pb | Mn | Zn |

| LOD | 1–3 | 4–10 | 10–35 | 2–6 | 2–9 | 15–30 | 5–20 | 20–50 | 1–4 | 3–7 | 1–3 |

| ICP-MS | |||||||||||

| Element | As | Ni | Ca | Cu | Cr | Ba | Fe | K | Pb | Mn | Zn |

| MDL | 0.027 | 0.067 | 1.140 | 0.030 | 0.021 | 0.002 | 0.034 | 4.206 | 0.004 | 0.006 | 0.023 |

Limit of detections for soils and the geochemical modes (Olympus Corporation, n.d.c).

2.5. pXRF Soil Elemental Analysis

The pXRF instrument (DELTA Premium Handheld XRF) used in this study was purchased from OLYMPUS, USA, and consisted of a 40kV tube and large-area silicon drift detector used mainly for detecting low levels of trace elements in soil and mining (Olympus Corporation, n.d.). The pXRF instrument is also equipped with optimized beam settings of 4W x-ray tube and 200 μA current, a rechargeable Li-ion battery, and automatic barometric pressure correction.

Prior to soil analysis, the internal X-ray stability was monitored per the guided manual by calibrating the lowest energy electron shell (Fe K-α) of 316 stainless steel coins before each run, which helps measure the count of the elements based on their oxide weight proportion. For quality assurance and control prior to usage, quality control and assurance, a SiO2 blank and NIST standard measurements were taken prior to sample analyses. Table 1 shows the manufacture’s LODs in part per million or microgram per kilogram (ppm, μg g−1) in the operational setting “geochemistry” and was used for calibrating the pXRF. DELTA PC Software configured the calibration modeling and beam operation to enhance data analysis. The general procedure followed the U.S.EPA Method 6200 intrusive analysis (U.S.EPA, 2007), and the Center for Disease Control/Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry’s (ATSDR) soilSHOP protocol (ATSDR, 2022).

As done for ICP-MS analysis, Arizona’s soil samples were sieved, dried, and balled milled then analyzed via pXRF; whereas Troy’s Soil samples were only sieved and dried for the analysis. All the soil samples were analyzed in the laboratory by trained technicians using the pXRF, Gardenroots samples were screened for 19 elements, whereas Troy samples were screened for only 10 elements. All soil samples were individually stored in 6.5 × 5.9-inch Ziplock bags. Each sample was screened for 90 seconds at 3 discrete locations, ensuring the soil in the Ziplock bag is at least 1-inch thick at each screening point. If there was a high variation >20% between the three values, additional screenings were conducted to ensure the accurate measurement for each soil sample. Lastly, the average of the three screening results was calculated and recorded with the corresponding sample number in the logbook.

2.6. Data Analysis Methods

To validate the pXRF methodology, a series of statistical analyses were conducted between pXRF and ICP-MS measurements for each element of concern in this study, and the unit expressed in (μg g−1). The following ICP-MS below detection limits elements Mo, Co, Se, Ag, Sn, and Sb were excluded from the analysis. All statistical procedures used in this study were conducted via R-studio version 4.1.1, Adobe Photoshop version 22.4.2 and Microsoft excel 2016. Using mean concentration of each metal(loid)s, a two-sample t-test was performed first to test the null hypothesis that the average concentration of each metal(loid) concentration was the same for both methods. If the probability values were not significantly different (p > 0.05), then there is no variation effect observed between the two method’s elemental concentration.

Next, an intraclass correlation (ICC) was also performed as another approach to quantify the similarity between the two methods. A high ICC coefficient (close to 1) suggests high similarity between methods whereas a low ICC value (close to 0) indicates elemental concentrations were different depending on the method utilized, thus measuring the linear relationship between two continuous variables, where each concentration is scaled by mean and standard deviation.

To further compare the two methods and where one technique is considered the “gold standard”, in this case, ICP-MS, a Bland-Altman analysis was conducted to assess how similar the pXRF is to the ICP-MS. The x-axis represents the mean of each element for both methods and the y-axis represent the difference between the sampling method concentrations (Giavarina, 2015). Each plot has the average concentration represented as a horizontal line. The upper and lower lines represent the limits of agreement, meaning that if the differences are normally distributed, 95% of the data should be between these limits.

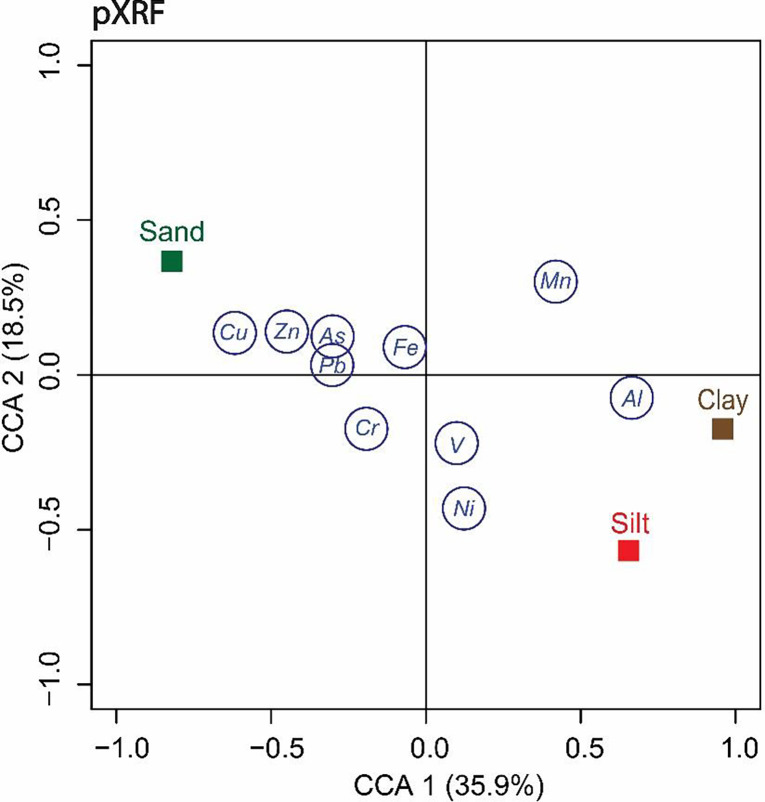

Based on the findings of the two-sample t-test and interclass correlation coefficients, a post-hoc testing using Tukey’s HSD for two-factor ANOVA was applied to the Arizona’s soil to further understand the variability of the pXRF data. It was hypothesized that soil amendment (unamended, yard and amended, garden) would contribute to the disparity in elemental concentration. To determine whether soil texture influenced pXRF performance, a Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) was conducted (Hardoon et al., 2004). The analysis describes the association between two data matrices which are soil texture and elemental concentrations by measuring the linear relationship while preserving the main facets of the correlation.

2.7. Enrichment, Accumulation, and Pollution Comparisons Methods

2.7.1. Enrichment Factor

To evaluate the degree of pollution and whether the pXRF could reliably indicate enrichment, the pXRF and ICP-MS soil data was also used to calculate the enrichment factor. EF describes the presence of an element relative to the reference metric (Bern et al., 2019). The EF was calculated as:

| (1) |

where is the detected metal(loid) mean concentration by pXRF or ICP-MS in units of mg kg−1. The Mn mean concentration detected by the ICP-MS was set as the reference value , except for Mn calculation which has Fe mean concentration as the . All the background concentrations ( and ) were implemented based on element concentrations in soils determined by United States Geological Survey (Table 2, Shacklette and Boerngen, 1984). EF less than one indicate no enrichment; 1 < EF < 3 means a minor enrichment; 3 < EF < 5 describes a moderate enrichment; 5 < EF < 10 explains a moderately severe enrichment; 10 < EF < 25 define a severe enrichment condition; 25 < EF < 50 is very severe enrichment; EF > 50 is extremely severe enrichment (Chen et al., 2007).

Table 2.

Background elemental soil concentrations (µg g−1) for the western conterminous states, USA as originally provided by Shacklette & Boerngen, 1984.

| Elements | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | |

|

| ||||

| As | 0.1 | 97 | 5.5 | 1.98 |

|

| ||||

| Ba | 70 | 5000 | 580 | 1.72 |

|

| ||||

| Cu | 2 | 300 | 21 | 2.07 |

|

| ||||

| Pb | 10 | 700 | 17 | 1.8 |

|

| ||||

| Mn | 30 | 5000 | 380 | 1.98 |

|

| ||||

| Zn | 10 | 2100 | 55 | 1.79 |

2.7.2. Geo-accumulation Index

To determine whether the pXRF could reliably indicate metal accumulation, the Müller, (1969) geo-accumulation index was used. The is described as the following:

| (2) |

Where, is the mean concentration of the measured element by pXRF or ICP-MS and is the geochemical background concentration of the corresponding metal taken from Shacklette and Boerngen, (1984). The approach evaluates the metal contamination through six accumulation grades from, uncontaminated, ); very low and low contaminated ; moderately contaminated ; highly contaminated ; very highly contaminated ; highly to extremely contaminated ; extremely contaminated at (Chen et al., 2007).

2.7.2. Pollution Load Index

Pollution Load Index (PLI) provides a comparative estimate of the levels of HMs using reference values such as those provided by the U.S. Department of the Interior. The PLI helps test the impact of the HM detected by pXRF and ICP-MS on soil micro flora and fauna. To determine whether the pXRF could reliably provide a pollution load index (PLI), defined as the contamination status of each metal in relation to background concentrations at a specific site. A PLI value above 1 indicates soil pollution (Tomlinson et al., 1980). The PLI equation describes the overall risk of metal(loid)s exposures from the soil as the following:

| (3) |

Where is referred as the mean ratio of the concerned metals to their background concentrations taken from United States Geological Survey (Table 2, Shacklette and Boerngen, 1984) and n is the number of total metals.

Descriptive statistics of the metal(loid)s concentrations determined by pXRF and ICP-MS in Arizona and New York soils are presented in table 3. The mean value of each element was used for EF, , and PLI calculations.

Table 3.

Elemental Arizona and New York soil concentrations (µg g−1) determined by pXRF and ICP-MS analysis.

| Arizona | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| ICP-MS (N=124) |

pXRF (N=124) |

|||||||

| Elements | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

|

| ||||||||

| Zn | 13.8 | 1626 | 187.1 | 252.1 | 16.8 | 908.7 | 152.7 | 213.2 |

| Mn | 149.6 | 2493.3 | 478.3 | 287 | 118.7 | 1264 | 511.5 | 240.9 |

| Pb | 4.65 | 498.9 | 56.8 | 93.4 | 5.63 | 436 | 51.4 | 71.5 |

| As | 0.79 | 23.2 | 4.6 | 3.27 | 2.15 | 26.7 | 6.27 | 4.1 |

| Ba* | 24.4 | 1576 | 204.9 | 178.4 | 129.7 | 417 | 253.6 | 55.6 |

| Ca | 1406 | 1.7×105 | 3.5×105 | 2.9×104 | 1277 | 1.5×105 | 2.9×104 | 2.1×104 |

| Cu | 5.78 | 1019 | 105.8 | 174.7 | 6.8 | 1129 | 116.7 | 186 |

| Ni | 2.17 | 51 | 13.8 | 8.2 | 15 | 59.3 | 28.2 | 8.94 |

| Cr | 6.46 | 58.2 | 18.05 | 8.27 | 19 | 79.3 | 37.2 | 12.2 |

| K | 772.9 | 6820 | 3008 | 1186 | 2836 | 2.6×104 | 1.5×104 | 4980 |

| Fe | 2614 | 2.8×104 | 9793 | 3865 | 6838 | 3.5×104 | 1.9×104 | 6012 |

|

| ||||||||

| New York | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| ICP-MS (N=33) |

pXRF (N=33) |

|||||||

|

|

||||||||

| Elements | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | SD |

| Zn | 3.9 | 1008 | 198.3 | 224.6 | 79.7 | 1075 | 264.8 | 262.7 |

| Mn | 47.8 | 3362 | 689.7 | 513.7 | 223.5 | 2773 | 789.5 | 395.7 |

| Pb | 2.1 | 2941 | 227.5 | 520.1 | 21 | 2194 | 249.5 | 482.9 |

| As | 0.9 | 34.7 | 9.8 | 7.96 | 4.58 | 97 | 15.5 | 17.3 |

| Al | 2439 | 3 ×104 | 1.4×104 | 4974 | 3251 | 7148 | 5113 | 840.1 |

| V | 5.9 | 43.9 | 28.1 | 8.2 | 97.4 | 268.4 | 171.4 | 36.4 |

| Cu | 4.1 | 1577 | 86.5 | 264.3 | 11.9 | 218 | 51.5 | 44.4 |

| Ni | 5. | 74 | 24.1 | 11.8 | 13.1 | 64.3 | 29.1 | 10.6 |

| Cr | 40.1 | 217 | 78.5 | 39.7 | 28.5 | 304.1 | 59.9 | 52.2 |

| Fe | 3806 | 7.5×104 | 2.7×104 | 1.1×104 | 2.3×104 | 7.2×104 | 3.3×104 | 9487 |

Barium was only measured in Arizona due to limited number of New York soil samples.

3. Results

3.1. Two-sample t-test, ICC, and R2

Two-sample t-test, cumulative probabilities (p-value), interclass correlation coefficients (ICC), and R2 results for each metal(loid)s are presented in Table 4. Arsenic, Cu, Pb, Mn, and Zn had a p>0.05, indicating a failure to reject the null hypothesis; hence, pXRF and ICP-MS do not produce significantly different measurements. Contrastingly, Ni, Ca, Cr, Fe, and K were rejected by the null hypothesis due to a p<0.05. Calcium was the only metal with a low p-value and a very strong ICC.

Table 4.

Two-sample t-test, interclass correlation coefficients (ICC), and R2 results for each element of interest. Values were obtained using a 95% confidence level and a two-way agreement model. Bolded text indicates statistical significance.

| Arizona | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||

| As | Ni | Ca | Cu | Cr | Ba | Fe | Zn | Pb | Mn | K | |

|

| |||||||||||

| ICC coefficients | 0.87 | 0.29 | 0.87 | 0.98 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.17 | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.64 | 0.02 |

| P-value | 0.45 | 0 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 0 | 0.17 | 0 | 0.24 | 0.97 | 0.33 | 0 |

| T- Statistic | 0.74 | −4.93 | 2.11 | 0.81 | −14.43 | 1.39 | −14.32 | 1.16 | 0.04 | 0.99 | 26.08 |

| R2 | 0.76 | 0.08 | 0.76 | 0.95 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.82 | 0.83 | 0.42 | 0 |

|

| |||||||||||

| New York | |||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||

| As | Ni | V | Cu | Cr | Al | Fe | Zn | Pb | Mn | ||

|

| |||||||||||

| ICC coefficients | 0.54 | 0.52 | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.63 | 0.40 | 0.81 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 0.95 | |

| P-value | 0.11 | 0.22 | 0 | 0.38 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 | 0.31 | 0.90 | 0.47 | |

| T- Statistic | 1.62 | 1.24 | 22.09 | −0.89 | −2.39 | −11.6 | −13.9 | 1 | 0.12 | 0.72 | |

| R2 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.54 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.98 | 0.83 | 0.92 | |

With regards to the Troy, NY soil samples, As, Ni, Cu, Zn, Pb, and Mn had a p>0.05. In contrast, Al, Cr, Fe, and V had a p<0.05, indicating significant mean differences. Iron was the only element with a low p-value and a very strong ICC. In addition, Al had the weakest relation between the two methods, while As, Cr, Ni, and V presented a moderate ICC, followed by Fe and Cu. The strongest correlation was exhibited by Mn, Zn, and Pb.

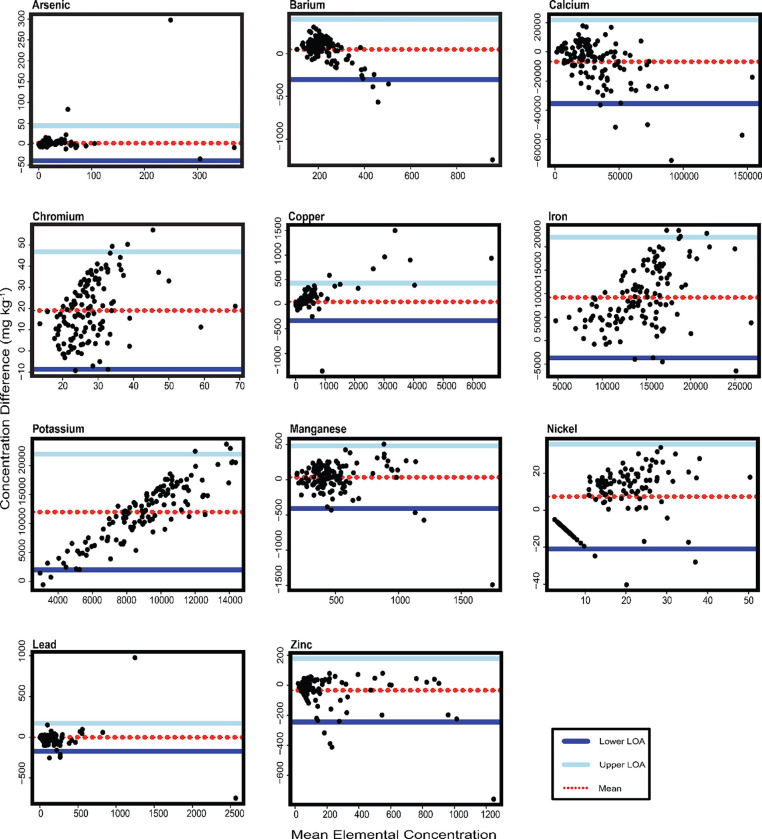

3.2. Bland-Altman and Tukey test analysis

Figure 2 shows the Bland-Altman plots for each element measured in Arizona soil samples. In general, points located around the mean line indicate no systematic biases, while points close to one of the LoA lines indicates a bias toward one method over the other. Elements with points scattered around the middle line, such as Zn, indicate no bias toward one method over the other, meaning they are similar; however, the pXRF slightly underestimates the Zn concentration. In Ca, Ba, and Cu, most points are scattered in the middle withfew points are located outside the LoA which can be due to higher concentration in one method than the other or an error in measuring. Further, the pXRF slightly overestimated the concentrations of Ba and Cu and slightly underestimated the Ca concentration. The lower and upper LoA explain the correlation strength between the two methods. A wide LoA range suggests a weak agreement as in Fe and Cr. A narrower LoA range indicates a more robust agreement as represented in Pb, Cu, As. Mn, although a few more points are in the upper LoA, explaining the slight overestimation by the pXRF. Points that form a straight line indicate a slight variation in means between the sampling methods and points scatter to form a sloped-like line, i.e., K and Ni, present a high variation between the two methods; hence, pXRF exceedingly overestimated K concentration.

Figure 2.

Bland-Altman plots for each element measured in Arizona soil samples. The x-axis represents the mean value of both methods, and the y-axis indicates the differences between their measurements. The upper and lower limits of agreement (LoA) indicate the range in which 95% of the values from the dataset lie. The LoA is the mean difference ± 1.96 multiply by the standard deviation of the differences.

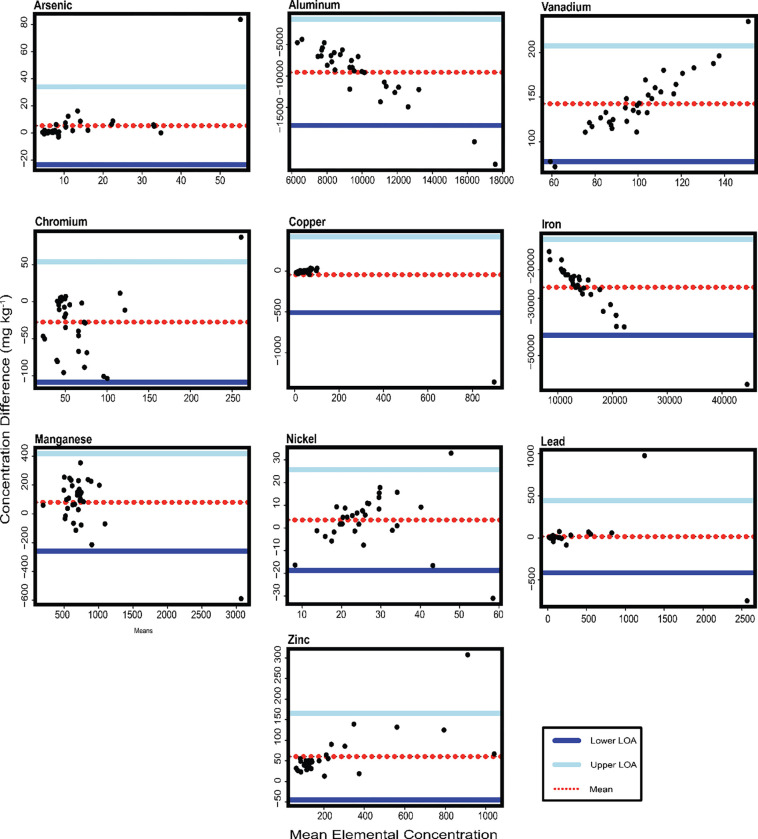

Figure 3 shows the Bland-Altman plots for each element measured in New York soil samples. In New York, Pb and Cu points were scatting around the mean line, suggesting no bias toward one method over the other. Zn and As points are close to the middle and the lower LoA, representing a slight overestimation for As concentration in pXRF. The slight proportional difference in Zn means values increased the LoA between the two measurements. Accordingly, the lower concentration data are closer to each other through the pXRF measurements, which was the reason for the slight Zn overestimation. A negative slope line was formed in Fe and Al, indicating a high variation between the two methods, and possibly explained by the greater pXRF measurements when compared to ICP-MS. Further, points that formed a positive slope and scatter away from the mean line also stipulated high variation, possibly explained by overestimated pXRF concentration; e.g., Ni. Finally, Mn and Cr had the points distributed within the LoA, demonstrating a robust agreement for Mn and to a lesser extent for Cr.

Figure. 3.

Bland-Altman plots for each element measured in New York soil samples. Bland-Altman plots for each element measured in Arizona soil samples. The x-axis represents the mean value of both methods, and the y-axis indicates the differences between their measurements. The upper and lower limits of agreement (LoA) indicate the range in which 95% of the values from the dataset lie. The LoA is the mean difference ± 1.96 multiply by the standard deviation of the differences.

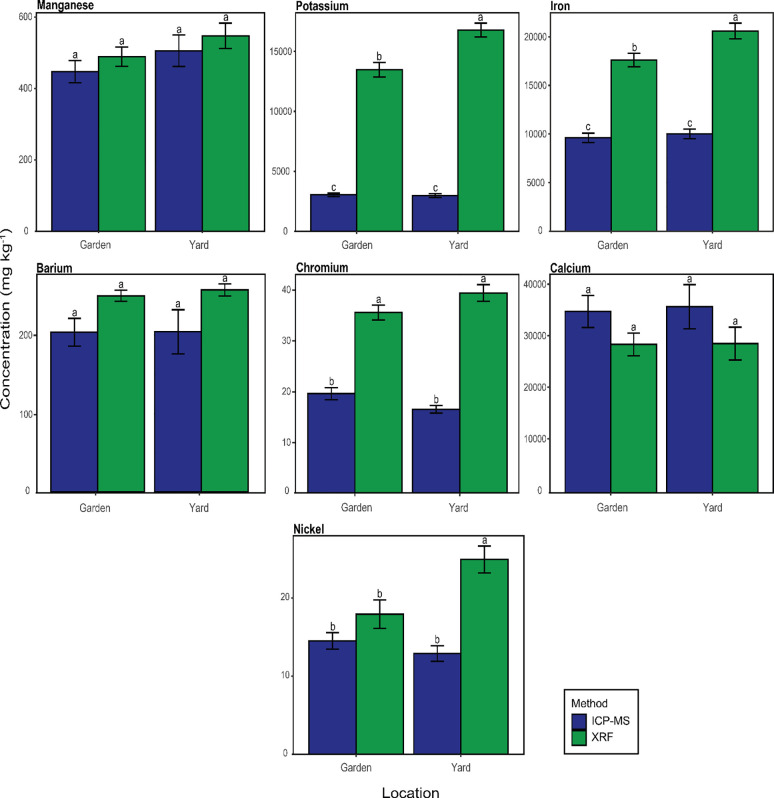

When element failed at least one of the statistical analyses listed above, the Arizona samples were divided by “garden and “Yard” and the average concentration by method were compared using a post-hoc Tukey’s HSD for a two-way ANOVA. Cr, Fe, and K concentrations in yard and garden soils differed significantly, for both methods, with yard soils being greater than the garden. Ni was significantly higher in the yard for pXRF and had no different variation in the garden site. Ca and Ba concentrations were not significantly different by site type or methods.

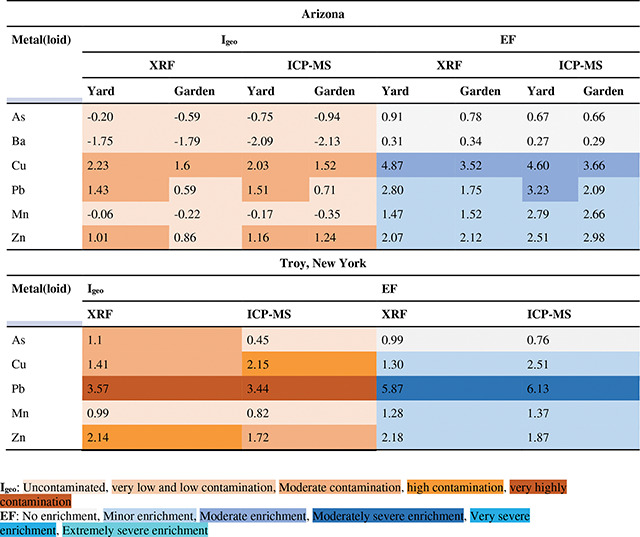

3.3. Geoaccumulation Index, Enrichment Factor, and Pollution Load Index

The and EF values are presented in table 5 for both Arizona and New York. In Arizona, the values of Ba, As, and Mn, for both methods and locations corresponded to uncontaminated soil conditions. Cu had the highest in yard soils followed by Pb and both fell within the range of very low and low contamination. In garden, the ICP-MS had a very low contamination index for Zn (), while presented an uncontaminated status by the pXRF (). Conversely, Zn in pXRF was analogous to ICP-MS and was showing a very low and low contamination in yard soil samples. Overall, the Arizona values for the two methods were similar, except for Zn in garden. and the New York values for the two methods were similar for Pb and Mn. The low As, Cu, and Zn New York values varied by one magnitude of accumulation based on the method.

Table 5.

Arizona and Troy, New York, USA soil geoaccumulation indices () and enrichment factors (EF) by pXRF and ICP-MS method (mean metal(loid) concentrations were used in calculations). A color gradient is used to indicate contamination (orange) and enrichment (blue).

|

The degree of enrichment for As, Ba, Cu, Pb, and Mn were similar in both methods in Arizona, while in yard soil, Pb EF value was slightly higher in ICP-MS than pXRF. The mean EF of soil samples presented no enrichment for Ba and As, minor enrichment for Mn and Zn, and moderate enrichment for Cu in both locations. The latter had showed the highest magnitude of enrichment in Arizona. Similarly, Pb was moderately enriched in the yard samples analyzed via ICP-MS. Conversely, similar degree of enrichment for all the element in New York were observed in both methods as shown in table 5. Here, Pb came up with the highest EF value whereas As showed no enrichment through all soil samples. Mn, Cu, and Zn were mildly enriched across both methods.

Table 6 summarizes the pollution load indices for both Arizona and New York soils by of method. Pollution load indices for As, Ba, Cu, Pb, Zn and Mn in both methods were similar and exceeded average natural background concentrations. In New York, the PLI was found to be higher than Arizona for both methods; therefore, the index has provided summative indication of the overall extent of metal(loid)s pollution presented in soil.

Table 6.

Arizona and Troy, New York, USA soil pollution load indices (PLI) by pXRF and ICP-MS method (mean metal(loid) concentrations were used in calculations). A similar PLI value indicates the reliability of pXRF to closely describe the pollution status.

| Arizona | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| PLI | XRF | ICP-MS | ||

|

|

||||

| Yard | Garden | Yard | Garden | |

|

| ||||

| Value | 1.59 | 1.53 | 1.61 | 1.52 |

| Contamination Status * | Polluted | Polluted | Polluted | Polluted |

|

| ||||

| Troy, New York | ||||

|

| ||||

| PLI | XRF | ICP-MS | ||

|

| ||||

| Value | 2.01 | 2.03 | ||

| Contamination Status | Polluted | Polluted | ||

The pollution index calculation combines all elements and due to this summation, some elements can be responsible for driving the pollution index, such as Zn and Cu. This is apparent in the calculated values where Zn and Cu have a moderate degree of accumulation in Arizona soil. Similarly, Cu is moderately enriched in Arizona soil as indicated in Table 5.

4. Discussion

4.1. Elements with Poor Detection and Accuracy

With regards to the Arizona garden and yard samples, Co, Sb, Mo, Ag, Cd, Sn, and Sb concentrations were below the pXRF detection limits. With regards to Ni, the negative slope seems to be evident in Bland-Altman analysis, indicating a high variation between methods due to overestimation of the metal by pXRF. Additionally, Fe, K, and Cr pXRF concentrations were not correlated with the ICP-MS data. These three elemental concentrations were overestimated by pXRF with yard being noticeably higher than garden, indicating a bias towards pXRF, especially as concentrations increased. This is further supported by the low agreement between the methods (i.e., more outliers are found toward the upper LoA).

Nickel had only one point below LoA (New York) and the overall trend of the pXRF measurements for Ni and V were weakly aligned with the ICP-MS. The Ni values from Arizona and New York behaved differently and this can be linked to the higher Fe concentration. pXRF can have a spectral interferences between Fe, Co, and Ni, specifically if Fe is presented at high concentration, limiting the instrument’s ability to distinguish between the three metals (Zheng et al., 2022; Arthur & Scherer, 2020; U.S.EPA, 2007). The apparent positive slope in Bland-Altman for V has presented a bias toward pXRF. Similarly, Al and Fe had a negative trend; hence, the pXRF has underestimated the metal(loid)s levels as indicated by the higher mean concentration in the Bland-Altman plot.

Spectral interference is a common challenge when it comes to detecting lighter elements and can lower the pXRF performance (Gallhofer & Lottermoser, 2018; Declercq et al., 2019). Al is known to be a light element, making the pXRF prone to detection issues, due to the low spectrum being absorbed before reaching the pXRF detector. This is clearly observed for Al concentration above 10,000 μg g−1 in figure 2.

4.2. Elements with Moderate to Excellent accuracy

The pXRF measurements for As, Cu, Pb, Zn, Mn, and Ba had no significant differences (p >0.05) from the ICP-MS in Arizona soils. The variation in the data distribution, for example, Ba has a low R2, ICC, and high p-values; this phenomenon can be attributed to the decreasing trend in the Bland-Altman plot at concentrations between 320 to 510 μg g−1. The Tukey HSD analysis of both garden and yard data in Arizona had no significant variability of Ba, showing a better agreement between the two methods.

Based on the R2 interpretation the seven metal(loid)s in Arizona can be approximately ranked from highest to lowest methodological agreement: Cu>Pb>Zn>As>Ca>Mn>Ba. Although Ca had a probability of zero, the ANOVA test indicated non-significant results in both garden and yard; and there was a good agreement between the two methods through the Bland-Altman analysis.. pXRF measurements of Pb, As, and Cu were the most closely aligned with those of ICP-MS. In addition, the Bland-Altman and R2 of Zn and Mn had strong agreement and presented ICC of 0.91 and 0.64, respectively.

The slight overestimation of Zn in NY soil through pXRF is possibly related to the calibration mode (Yang et al., 2020) used as well as the higher mean concentration (more than 200 mg kg−1) as determined through Bland-Altman. That’s been said, Zn concentrations were agreeable between methods; best expressed by the R2 and ICC. Based on R2 value in New York, the quantified metal(loid)s can be ranked from the strongest to the lowest as Zn>Mn>Pb>Cu>As. In addition, As came up with the lowest R2, but it did not show a bias pattern for one method over the other and most detections occurred at lower mean concentrations which were close to the Bland-Altman mean line. Moreover, Pb and Cu had the best agreement demonstrated by the points scattered around the Bland-Altman mean line, revealing a very strong pXRF accuracy.

4.3. Challenges associated with select soil properties and the pXRF

With regards to the comparison of yard vs. garden, the application of soil amendments can increase the amount of organic matter and constant irrigation can readily leach available elements throughout the soil horizons. Figure 4 shows the discrepancy between the two methods, where the gardens’ metal(loid)s concentrations are less than yard. Although the result was different between the two sites, here can possibly relate the lower Cr measured by pXRF in garden to soil OM; Ravansari, (2016) observed that the Cr concentration measured by pXRF decreased with the increase in cellulose organic matter fraction (Ravansari, 2016). Additionally, Ravansari and Lemke, (2018) had discussed the concentration deviations presented by pXRF based on the addition of different OM fractions. The attenuation response was elementally dependent on the increase of OM fractions. This scenario was attributed to the mode of calibration and pXRF algorithms and both were built upon the soil metrics provided by the manufactory.

Figure 4.

Bar plots and of mean elemental Arizona garden and yard soil concentrations in by method. The error line in the figure represents the standard deviation. A Tukey’s HSD post-hoc test for a two-factor ANOVA was used; bars with the different letters indicate a significant difference.

The CCA diagram revealed the correlation between soil texture analysis and pXRF elemental measurements in Troy, New York (Fig. 5). The first two principal dimensions CCA1 and CCA2 explained 35.9% and 18.5 % of the total variance, respectively. A positive correlation was observed between sand and Cu, Zn, As, Pb, and Fe; clay and Al, V, and Ni; Silt and Al, Ni, and V. Here, one is expecting Cr to be positively correlated to soil texture (Kim & Dixon, 2002; Lacroix et al., 2021; Rudzionis et al., 2022), however, due to high Fe concentration, the pXRF efficiency in reporting the actual amount of Cr declines due to a lower absorption edge in energy than the fluorescent peak of Fe (EPA, 2007). Such an effect can be corrected mathematically using fundamental parameter coefficients related to particle size and matrix effects. The consequences of calibrating pXRF by LOD has been widely studied, recent work has shown the disparities in X-ray spectrum for non-quantified elements, necessitating the manual inspection and calibration of the pXRF (Singh et al., 2022). On that account, the attenuation in pXRF measurements caused by OM needs to be further investigated to validate the technique’s calibration, namely in amended soil. Arsenic and Pb have a dependent relationship, high lead soil concentrations will affect the pXRF spectra detection range of As, which is described by the manufacturer as Interference-free detection limits (DLs) (Olympus Corporation, n.d.b.). Here, the L-lines emitted by atoms of Pb overlap with the K-line of As (Gallhofer and Lottermoser, 2018). The pXRF model attempts to automatically correct the As value when Pb is presented in high concentrations; however, in these instances, is critical to manually calibrate the instrument with soil from the targeted region to improve As detection.

Figure. 5.

Canonical Correspondence Analysis Diagram showing the association between soil texture and pXRF elemental concentrations in soil from Troy, New York. Chromium and Manganese were not located in proximity to any soil texture, indicating an unclear association between the pXRF measurement and soil texture.

4.4. The influence of anthropogenic activities

As described in section 2.1, mining activities may have affected some areas of Arizona and releasing heavy metals in and surrounding communities. Some As compounds and ions are distributed in the surrounding environment during smelting and mining the ore, impacting nearby communities, primarily via surface soil deposition, impacting residential areas (Sutherland et al., 2003). Zinc enrichment was observed, indicating anthropogenic activities influencing soil concentrations. This is especially observed in the enrichment analyses conducted with the pXRF garden’s data. The result might be related to the mining industry in Greenlee County, Arizona. Using the U.S.EPA Toxic Release Inventory (U.S.EPA TRI) data set, the risk-screening environmental indicator reported a median released or transferred of 7,199 pounds for Cu, Ni, Pb, and Zn together, this is 24 times higher than the reported state median value (U.S.EPA, 2021). Lead had a different description in Arizona yard than garden in pXRF, and yard in ICP-MS. The discrepancy within the pXRF might be related to different sources of Pb. Troy is an urban area influenced by anthropogenic activity, i.e., roadside soil accumulates Pb due to car exhaust emissions and in general, soils are impacted by the atmospheric deposition of Pb, Pb-based paint, and ongoing industrial activities (Ravansari et al., 2020; Turner and Lewis, 2018; Wang et al. 2006). Arsenic measured by pXRF had a higher magnitude of than ICP-MS in Troy, NY, which may be attributed to the difference in anthropogenic sources since samples were collected across the city. With regards to the PLI it is important to note that the metal(loid)s measured in this study may be naturally occurring due to local geologic conditions where formed soils may have naturally elevated levels of certain metal(loid)s.

5. Conclusion

The elevated accumulation rate of metal(loid)s in soils presents a potential risk to human health, especially when little attention is given to soil health as related to local geology and the potential impact of anthropogenic activities. This calls for raising community awareness and increasing capacity to take appropriate environmental monitoring measures. This effort requires a method like the pXRF that is viable for use, relatively low cost, and user-friendly.

The assessment of 19 elements divided between Arizona and New York highlighted the pXRF reliability to measure As, Pb, Cu, Zn, Ca, Ba and Mn. The dynamic statistical approach employed in this study demonstrated a correlation between pXRF and ICP-MS measurements. The discrepancies in the agreement between the two methods can be minimized by properly calibrating the instrument based on the area of interest’s soil matrix. Moreover, the evidence and observation from other studies had previously reported the pXRF failures based on spectra interference between non-quantified metal(loid)s, like Ni and Fe. Similarly, pXRF had failed to detect Al and presented a significant variance compared to ICP-MS due to its light atomic weight.

The proposed study is building upon the Gardenroot project methodology (Ramírez-Andreotta et al., 2015), which works alongside local communities near resource extraction sites to build human capacity, increase our understanding of their surrounding environment, and provide public health intervention and prevention practices to mitigate/minimize metal(loid) exposures and risk. Here, the data was governed by the resources available such as community participation. Since efforts focused on exposure science public health prevention/intervention strategies, other variables like pH, OM, and PSD were not determined. Future efforts should include more soil biogeochemical analyses and pre-calibration techniques to further tease out the disparities between pXRF and the gold standard, ICP-MS to extend the application of pXRF device. Regardless, this study highlights the pXRF reliability to measure As, Ba, Ca, Cu, Mn, Pb, and Zn indicating its utility in community soil monitoring efforts.

Acknowledgements

A special thank you to all the Gardenroots participants and the following University of Arizona Cooperative Extension County offices: Cochise (Susan Pater, Josh Sherman), Greenlee (Kim McReynolds, Bill Cook), and Apache (Mike Hauser). A massive thank you to Mely Bohlman for assisting in the soil pXRF analysis. We would like to thank Shana Sandhaus for supporting multiple project activities which enabled this research, Rob Root, and our colleagues in the Integrated Environmental Science and Health Risk Laboratory for their support throughout this process.

Financial Support

We would like to thank the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Research Program (P42ES04940), Center for Environmentally Sustainable Mining initiated by the Water, Environmental, and Energy Solutions – Technology Research Initiative Fund Water Sustainability Program, and U.S. National Science Foundation, Grant No. 1922257. We are also grateful for student support provided by the Kuwait Institute for Scientific Research.

Footnotes

Competing Interests

No competing interests to report.

Data Availability

Datasets can be requested from the corresponding author.

References

- ADEQ. (n.d.). Apache Powder Company | Site History. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, USA. Retrieved from https://azdeq.gov/apache-powder-company-site_history (accessed 1 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- ADEQ. (2021a). Iron King Mine and Humboldt Smelter | Site History. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, USA. Retrieved from https://www.azdeq.gov/IronKingMine/SiteHistory (accessed 29 April 2022). [Google Scholar]

- ADEQ. (2021b). Superfund Alternative Site | ASARCO Hayden Plant. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, USA. Retrieved from http://azdeq.gov/node/1871 (accessed 1 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- ADEQ. (2022). What is a Superfund Site?. Arizona Department of Environmental Quality, USA. Retrieved from https://azdeq.gov/NPL_Sites (accessed 30 April 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Amari T., Ghnaya T., & Abdelly C. (2017). Nickel, cadmium and lead phytotoxicity and potential of halophytic plants in heavy metal extraction. South African Journal of Botany, 111, 99–110. 10.1016/j.sajb.2017.03.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Amlal F., Drissi S., Makroum K., Dhassi K., Er-rezza H., & Aït Houssa A. (2020). Influence of soil characteristics and leaching rate on copper migration: column test. Heliyon, 6(2), e03375–e03375. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03375 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur R., & Scherer P. (2020). Application of total reflection X-Ray fluorescence spectrometry to quantify cobalt concentration in the presence of high iron concentration in biogas plants. Spectroscopy Letters, 53(2), 100–113. 10.1080/00387010.2019.1700526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ATSDR. (2022). soilSHOP Toolkit. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, Atlanta, Georgia, USA. Retrieved from https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/soilshop/index.html (accessed 12 March 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Bartuska A. M., and Ungar I. A. 1980. ELEMENTAL CONCENTRATIONS IN PLANT TISSUES AS INFLUENCED BY LOW pH SOILS. Plant and Soil, 55(1), 157–161. 10.1007/BF02149720 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bern C., Walton-Day K., & Naftz D. L. (2019). Improved enrichment factor calculations through principal component analysis; examples from soils near breccia pipe uranium mines, Arizona, USA. Environmental Pollution (1987), 248, 90–100. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.01.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borch T., Kretzschmar R., Kappler A., Cappellen P. V., Ginder-Vogel M., Voegelin A., & Campbell K. (2010). Biogeochemical Redox Processes and their Impact on Contaminant Dynamics. Environmental Science & Technology, 44(1), 15–23. 10.1021/es9026248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campillo-Cora C., Rodríguez-González L., Arias-Estévez M., Fernández-Calviño D., & Soto-Gómez D. (2021). Influence of physicochemical properties and parent material on chromium fractionation in soils. Processes, 9(6), 1073. 10.3390/pr9061073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caporale A., Adamo P., Capozzi F., Langella G., Terribile F., & Vingiani S. (2018). Monitoring metal pollution in soils using portable-XRF and conventional laboratory-based techniques: Evaluation of the performance and limitations according to metal properties and sources. The Science of the Total Environment, 643, 516–526. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.06.178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C., Kao C.-M., Chen C.-F., & Dong C.-D. (2007). Distribution and accumulation of heavy metals in the sediments of Kaohsiung Harbor, Taiwan. Chemosphere (Oxford), 66(8), 1431–1440. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2006.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- City of Troy - Planning Department, (n.d.). REALIZE TROY COMPREHENSIVE PLAN. Department of State with funds provided under Title 11 of the Environmental Protection Fund. Retrieved from https://www.troyny.gov/AgendaCenter/ViewFile/ArchivedAgenda/_04062023-209 (accessed 19 March 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Das S., Jean J.-S., Kar S., & Chakraborty S. (2013). Effect of arsenic contamination on bacterial and fungal biomass and enzyme activities in tropical arsenic-contaminated soils. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 49(6), 757–765. 10.1007/s00374-012-0769-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Matos A., Fontes M. P. F., da Costa L. M., & Martinez M. A. (2001). Mobility of heavy metals as related to soil chemical and mineralogical characteristics of Brazilian soils. Environmental Pollution (1987), 111(3), 429–435. 10.1016/S0269-7491(00)00088-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq Y., Delbecque N., De Grave J., De Smedt P., Finke P., Mouazen A. M., Nawar S., Vandenberghe D., Van Meirvenne M., & Verdoodt A. (2019). A comprehensive study of three different portable XRF scanners to assess the soil geochemistry of an extensive sample dataset. Remote Sensing (Basel, Switzerland), 11(21), 2490. 10.3390/rs11212490 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ettler V., Tomášová Z., Komárek M., Mihaljevič M., Šebek O., & Michálková Z. (2015). The pH-dependent long-term stability of an amorphous manganese oxide in smelter-polluted soils: Implication for chemical stabilization of metals and metalloids. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 286, 386–394. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.01.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkhondeh T., Samarghandian S., & Azimi-Nezhad M. (2019). The role of arsenic in obesity and diabetes. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 234(8), 12516–12529. 10.1002/jcp.28112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fashola M., Ngole-Jeme V. M., & Babalola O. O. (2016). Heavy metal pollution from gold mines: Environmental effects and bacterial strategies for resistance. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(11), 1–1. 10.3390/ijerph13111047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallhofer D., & Lottermoser B. G. (2018). The influence of spectral interferences on critical element determination with portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF). Minerals (Basel), 8(8), 320. 10.3390/min8080320 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giavarina D. (2015). Understanding Bland Altman analysis. Biochemia Medica, 25(2), 141–151. 10.11613/BM.2015.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G., & Klinck Jason. (2005). Canada’s Resilient North: The Impact of Mining on Aboriginal Communities. Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health, (3), 116–139. [Google Scholar]

- Gitet H., Hilawie M., Muuz M., Weldegebriel Y., Gebremichael D., & Gebremedhin D. (2016). Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in crop plants grown near Almeda Textile Factory, Adwa, Ethiopia. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 188(9), 500–500. 10.1007/s10661-016-5511-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorini F., Muratori F., & Morales M. A. (2014). The Role of Heavy Metal Pollution in Neurobehavioral Disorders: a Focus on Autism. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1(4), 354–372. 10.1007/s40489-014-0028-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haddaway N., Cooke S. J., Lesser P., Macura B., Nilsson A. E., Taylor J. J., & Raito K. (2019). Evidence of the impacts of metal mining and the effectiveness of mining mitigation measures on social-ecological systems in Arctic and boreal regions: A systematic map protocol. Environmental Evidence, 8(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s13750-019-0152-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haidar Z., Fatema K., Shoily S. S., & Sajib A. A. (2023). Disease-associated metabolic pathways affected by heavy metals and metalloid. Toxicology Reports, 10, 554–570. 10.1016/j.toxrep.2023.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardoon D., Szedmak S., & Shawe-Taylor J. (2004). Canonical Correlation Analysis: An Overview with Application to Learning Methods. Neural Computation, 16(12), 2639–2664. 10.1162/0899766042321814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejna G., Gottardo D., Baldi A., Dell’Orto V., Cheli F., Zaninelli M., & Rossi L. (2018). Review: Nutritional ecology of heavy metals. Animal (Cambridge, England), 12(10), 2156–2170. 10.1017/S175173111700355X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine P.M., Stewart M. A., Barnett M. O., Basta N. T., Brooks S. C., Fendorf S., & Mehlhorn T. L. (2013). Influence of Soil Geochemical and Physical Properties on Chromium(VI) Sorption and Bioaccessibility. Environmental Science & Technology, 47(19), 11241–11248. 10.1021/es401611h [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Kim Y. J., & Seo Y. R. (2015). An Overview of Carcinogenic Heavy Metal: Molecular Toxicity Mechanism and Prevention. Journal of Cancer Prevention, 20(4), 232–240. 10.15430/jcp.2015.20.4.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.G., & Dixon J. B. (2002). Oxidation and fate of chromium in soils. Soil Science and Plant Nutrition (Tokyo), 48(4), 483–490. 10.1080/00380768.2002.10409230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix E., Cauzid J., Teitler Y., & Cathelineau M. (2021). Near real-time management of spectral interferences with portable x-ray fluorescence spectrometers: Application to sc quantification in nickeliferous laterite ores. Geochemistry : Exploration, Environment, Analysis, 21(3). 10.1144/geochem2021-015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen K., McLellan E., Metzger D. S., Kegeles S., Strauss R. P., Scotti R., Blanchard L., & Trotter Robert T II. (2001). What Is Community? An Evidence-Based Definition for Participatory Public Health. American Journal of Public Health (1971), 91(12), 1929–1938. 10.2105/AJPH.91.12.1929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamindy-Pajany Y., Sayen S., Mosselmans J. F. W., & Guillon E. (2014). Copper, Nickel and Zinc Speciation in a Biosolid-Amended Soil: pH Adsorption Edge, μ-XRF and μ-XANES Investigations. Environmental Science & Technology, 48(13), 7237–7244. 10.1021/es5005522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marguí E., Dalipi R., Sangiorgi E., Bival Štefan M., Sladonja K., Rogga V., & Jablan J. (2022). Determination of essential elements (Mn, Fe, Cu and Zn) in herbal teas by TXRF, FAAS and ICP-OES. X-Ray Spectrometry, 51(3), 204–213. 10.1002/xrs.3241 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire C., & Robinett D. (2003). Soil survey of Cochise County, Arizona: Douglas-Tombstone part. Natural Resources Conservation Service, U.S. Dept. of Agriculture., Agricultural Experiment Station, University of Arizona., Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Squire G.R., & Robinson G. M. (2009). Sustainable Rural Systems. Sustainable Agriculture and Rural Communities. Experimental Agriculture, 45(3), 379. 10.1017/S0014479709007753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Müller G. (1969). Index of Geoaccumulation in Sediments of the Rhine River. GeoJournal, 2, 108–118. [Google Scholar]

- NCSS, (2006). LUZENA SERIES. National Cooperative Soil Survey, USA. Retrieved from https://casoilresource.lawr.ucdavis.edu/sde/?series=LUZENA#osd (accessed 30 April 2022). [Google Scholar]

- NOAA National Centers for Environmental information, 2022. Climate at a Glance: County Mapping. Retrieved from https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag/county/mapping/2/tavg/202103/12/value (accessed 30 April 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Olympus Corporation, n.d.a. DELTA Premium Handheld XRF Analyzer. Retrieved from https://www.olympus-ims.com/en/delta-premium/ (accessed 20 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Olympus Corporation, n.d.b. XRF Technology for Analysis of Arsenic and Lead in Soil. Retrieved from https://www.olympus-ims.com/en/applications/xrf-technology-analysis-arsenic-lead-soil (accessed 28 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Olympus Corporation, n.d.c. DELTA Handheld XRF Limits of Detection (LODs) for Geochemical Analyzers. Retrieved from https://www.olympus-ims.com/en/xrf-analyzers/handheld/ (accessed 28 July 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Paschoalini A.L., Savassi L. A., Arantes F. P., Rizzo E., & Bazzoli N. (2019). Heavy metals accumulation and endocrine disruption in Prochilodus argenteus from a polluted neotropical river. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 169, 539–550. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2018.11.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez-Andreotta M., Brusseau M. L., Artiola J., Maier R. M., & Gandolfi A. J. (2015). Building a co-created citizen science program with gardeners neighboring a superfund site: The Gardenroots case study. International Public Health Journal, 7(1), 139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramírez-Andreotta M., Walls R., Youens-Clark K., Blumberg K., Isaacs K. E., Kaufmann D., & Maier R. M. (2021). Alleviating Environmental Health Disparities Through Community Science and Data Integration. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 5. 10.3389/fsufs.2021.620470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravansari. (2016). Portable x-ray fluorescence measurement viability in organic rich soils: pXRF response as a function of organic matter presence. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Ravansari R., & Lemke L. D. (2018). Portable X-ray fluorescence trace metal measurement in organic rich soils; pXRF response as a function of organic matter fraction. Geoderma, 319, 175–184. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2018.01.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ravansari R., Wilson S. C., & Tighe M. (2020). Portable X-ray fluorescence for environmental assessment of soils: Not just a point and shoot method. Environment International, 134, 105250. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravansari R., Wilson S. C., & Tighe M. (2020). Portable X-ray fluorescence for environmental assessment of soils: Not just a point and shoot method. Environment International, 134, 105250. 10.1016/j.envint.2019.105250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson C.A., Swartzbaugh L., Evans T., & Conway F.M. (2019). Directory of Active Mines in Arizona: FY 2019. Arizona Geological Survey Open-File Report-19-04, 12 pages. Interactive Arizona Mines Map. Retrieved from https://tinyurl.com/AZ-ActiveMinesMap (accessed 15 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Rudzionis Z., Navickas A. A., Stelmokaitis G., & Ivanauskas R. (2022). Immobilization of Hexavalent Chromium Using Self-Compacting Soil Technology. Materials, 15(6), 2335. 10.3390/ma15062335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhaus S., Kaufmann D., Ramirez-Andreotta M.D., 2019. Public Participation, Trust and Data Sharing: Gardens as Hubs for Citizen Science and Environmental Health Literacy Efforts. International Journal of Science Education. Part B. Communication and Public Engagement, 9(1), 54–71. 10.1080/21548455.2018.1542752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhaus S., Kaufmann D., & Ramirez-Andreotta M. (2019). Public participation, trust and data sharing: gardens as hubs for citizen science and environmental health literacy efforts. International Journal of Science Education. Part B. Communication and Public Engagement, 9(1), 54–71. 10.1080/21548455.2018.1542752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shacklette H., & Boerngen J. G. (1984). Element concentrations in soils and other surficial materials of the conterminous United States (Vol. 1270). United States Department of the Interior, Geological Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Weindorf D. C., Man T., Aldabaa A. A. A., & Chakraborty S. (2014). Characterizing soils via portable X-ray fluorescence spectrometer; 3, Soil reaction (pH). Geoderma, 232–234, 141–147. 10.1016/j.geoderma.2014.05.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh P., Datta M., Ramana G. V., Gupta S. K., & Malik T. (2022). Qualitative comparison of elemental concentration in soils and other geomaterials using FP-XRF. PloS One, 17(5), e0268268–e0268268. 10.1371/journal.pone.0268268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockmann U., Jang H. J., Minasny B., & McBratney A. B. (n.d.). The Effect of Soil Moisture and Texture on Fe Concentration Using Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometers. In Digital Soil Morphometrics (pp. 63–71). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-28295-4_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland. (2003). Lead in grain size fractions of road-deposited sediment. Environmental Pollution (1987), 121(2), 229–237. 10.1016/S0269-7491(02)00219-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepanosyan G., Sahakyan L., Belyaeva O., Asmaryan S., & Saghatelyan A. (2018). Continuous impact of mining activities on soil heavy metals levels and human health. The Science of the Total Environment, 639, 900–909. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian K., Huang B., Xing Z., & Hu W. (2018). In situ investigation of heavy metals at trace concentrations in greenhouse soils via portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 25(11), 11011–11022. 10.1007/s11356-018-1405-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S., & Lata C. (2018). Heavy metal stress, signaling, and tolerance due to plant-associated microbes: An overview. Frontiers in Plant Science, 9, 452–452. 10.3389/fpls.2018.00452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson D.L., Wilson J. G., Harris C. R., & Jeffrey D. W. (1980). Problems in the assessment of heavy-metal levels in estuaries and the formation of a pollution index. Helgoländer Meeresuntersuchungen, 33(1–4), 566–575. 10.1007/BF02414780 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turekian K., & Wedepohl K. H. (1961). Distribution of the elements in some major units of the Earth’s crust. Geological Society of America Bulletin, 72(2), 175–191. 10.1130/0016-7606(1961)72[175:DOTEIS]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A., & Lewis M. (2018). Lead and other heavy metals in soils impacted by exterior legacy paint in residential areas of southwest England. The Science of the Total Environment, 619–620, 1206–1213. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.11.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2019. ACS Demographics and Housing Estimates, 2015–2020 American Community Survey 5-year estimates. Retrieved from https://data.census.gov/cedsci/table?q=Arizona,%20arizona&tid=ACSDP5Y2019.DP05&hidePreview=%20false (accessed 3 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2022. Apache County, Arizona - U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/apachecountyarizona (accessed 2 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2021. Troy city, New York- U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/troycitynewyork/PST045221 (accessed 4 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of the Interior, 2020. Trustees Settle Natural Resource Damage Claims Arising from Hazardous Substances Releases at Morenci Mine, Greenlee County, Arizona. Retrieved from https://www.doi.gov/restoration/news/Morenci-Mine-CD-entered-06-29-2012 (accessed 2 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, n.d.a. Superfund Site: STATE OF MAINE MINING CO TOMBSTONE, AZ. Retrieved from https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/CurSites/csitinfo.cfm?id=0900631 (accessed 1 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, n.d.b. Superfund Site: ASARCO HAYDEN PLANT HAYDEN, AZ. Retrieved from https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0900497#bkground (accessed 5 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, n.d.c. Superfund Site: C & F PLATING CO INC ALBANY, NY. Retrieved from https://cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/CurSites/csitinfo.cfm?id=0204500 (accessed 5 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, 2015. EJSCREEN Data−−2015 Public Release. EPA’s Environmental Justice Screening and Mapping Tool. Retrieved from https://edg.epa.gov/metadata/catalog/search/resource/details.page?uuid=%7BB6FE56EE-3D28-4B5C-ABF0-D3B0B9E9DF87%7D (accessed 27 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, 2007. SW-846 Test Method 6200: Field Portable X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry for the Determination of Elemental Concentrations in Soil and Sediment 2015. EJSCREEN Data−−2015 Public Release. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sw-846-test-method-6200-field-portable-x-ray-fluorescence-spectrometry-determination (accessed 25 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- U.S.EPA, 2021. The Toxics Release Inventory Facility Report. RSEI Pounds Comparison. Retrieved from https://enviro.epa.gov/enviro/rsei.html?facid=85540PHLPS4521U (accessed 22 March 2023). [Google Scholar]

- US EPA IRIS, 2021. Arsenic. Inorganic CASRN 7440–38-2 | DTXSID4023886. Retrieved from https://cfpub.epa.gov/ncea/iris2/chemicallanding.cfm?substance_nmbr=278#:~:text=Cancer%20Assessment&text=Also%2C%20increased%20mortality%20from%20multiple,weight%2Dof%2Devidence%20narrative (accessed 17 August 2023). [Google Scholar]

- US EPA IRIS, 2022. Lead and Compounds (Inorganic). CASRN 7439–92-1. Retrieved from https://iris.epa.gov/ChemicalLanding/&substance_nmbr=277 (accessed 17 August 2023). [Google Scholar]

- USDA, (n.d.). Web soil survey. Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. Retrieved from https://websoilsurvey.sc.egov.usda.gov/App/WebSoilSurvey.aspx (accessed 5 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- USDA, 1999. Soil taxonomy: A basic system of soil classification for making and interpreting soil surveys (2nd ed., Agriculture handbook (United States. Department of Agriculture). Washington, DC: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. 436. Retrieved from https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/soils/survey/class/taxonomy/ (accessed 3 May 2022). [Google Scholar]

- Vogt, United States. Soil Conservation Service, & University of Arizona. Agricultural Experiment Station. (1980). Soil survey of San Simon area, Arizona: parts of Cochise, Graham, and Greenlee Counties. U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service. [Google Scholar]

- Walser G. (2002). Economic impact of world mining (IAEA-CSP−−10/P). International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Retrieved from https://inis.iaea.org/search/search.aspx?orig_q=RN:33032900 [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Qin Y., & Chen Y.-K. (2006). Heavy meals in urban roadside soils, part 1: effect of particle size fractions on heavy metals partitioning. Environmental Geology (Berlin), 50(7), 1061–1066. 10.1007/s00254-006-0278-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weindorf D., Paulette L., & Man T. (2013). In-situ assessment of metal contamination via portable X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy; Zlatna, Romania. Environmental Pollution (1987), 182, 92–100. 10.1016/j.envpol.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2019). Lead Poisoning and Health. World Health Organization. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lead-poisoning-and-health (accessed 20 August 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Wragg J. (2013). Soils and Human Health - edited by Brevik E.C. & Burgess L.C[Review of Soils and Human Health - edited by Brevik, E.C. & Burgess, L.C]. European Journal of Soil Science, 64(5), 731–731. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 10.1111/ejss.12070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y., Tong X., & Zhang Y. (2020). Spatial Variability of Soil Properties and Portable X-Ray Fluorescence-quantified Elements of typical Golf Courses Soils. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 519–519. 10.1038/s41598-020-57430-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong R., & Phadungchewit Y. (1993). pH influence on selectivity and retention of heavy metals in some Clay soils. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 30(5), 821–833. 10.1139/t93-073 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Young K., Evans C. A., Hodges K. V., Bleacher J. E., & Graff T. G. (2016). A review of the handheld X-ray fluorescence spectrometer as a tool for field geologic investigations on Earth and in planetary surface exploration. Applied Geochemistry, 72, 77–87. 10.1016/j.apgeochem.2016.07.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zeider K, Manjón I, Betterton EA, Saez AE, Sorooshian A, Ramírez-Andreotta MD. 2023. Backyard aerosol pollution monitors: Foliar surfaces, dust enrichment, and factors influencing foliar retention. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 195, 1200. 10.1007/s10661-023-11752-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng N., Wang Z., Zhao F., Li H., He H., Wang G., & Sheng H. (2022). Determining Chromium, Iron, and Nickel in a Nickel-Based Alloy by X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy. In Spectroscopy (Vol. 37, Issue 2, pp. 20–25). Intellisphere, LLC. 10.56530/spectroscopy.bt3486o3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W., Han G., Liu M., & Li X. (2019). Effects of soil pH and texture on soil carbon and nitrogen in soil profiles under different land uses in Mun River Basin, Northeast Thailand. PeerJ (San Francisco, CA), 2019(10), e7880–e7880. 10.7717/peerj.7880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang P., McBride M. B., Xia H., Li N., & Li Z. (2009). Health risk from heavy metals via consumption of food crops in the vicinity of Dabaoshan mine, South China. The Science of the Total Environment, 407(5), 1551–1561. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2008.10.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets can be requested from the corresponding author.