Abstract

Aim

This study aimed to investigate the association between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and both colorectal adenomatous polyps and non-

adenomatous polyps, in order to provide evidence for the prevention of colorectal cancer (CRC) in patients with NAFLD.

Methods

A retrospective, cross-sectional study was conducted at the First People’s Hospital of Kunshan, Jiangsu, China. The study included 3028 adults who underwent abdominal ultrasonography and colonoscopy over a 5 year period. We compared characteristics among patients with adenomatous polyps, non-adenomatous polyps, and without colorectal polyps using descriptive statistics. Logistic regression analyses were used to detect associations between NAFLD with the prevalence of adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps. NAFLD was determined by abdominal ultrasound. Colorectal polyps were assessed by data in the colonoscopy report and pathology report.

Results

A total of 65% of patients with NAFLD had colorectal polys (52% adenomatous polyps and 13% non-adenomatous polyps), and 40% of patients without NAFLD had polyps (29% adenomatous polyps and 11% non-adenomatous polyps). After adjusting for confounding variables, NAFLD was significantly associated with the prevalence of adenomatous in males and females [odds ratio (OR) = 1.8, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.6–2.2, P < 0.01], but was not associated with non-adenomatous polyps (OR = 1.2, 95% CI:0.9–1.5, P > 0.05).

Conclusion

NAFLD is associated with an increased risk of colorectal adenomatous polyps compared to the absence of polyps, but not associated with an increased risk of non-adenomatous polyps. These results provide important evidence for the prevention of CRC in patients with NAFLD.

Keywords: colorectal adenomatous polyps, colorectal polyps, non-adenomatous polyps, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Introduction

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined as hepatic steatosis without significant use of alcohol and secondary causes of hepatic fat accumulation [1]. It manifests as a continuum of liver abnormalities from nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, and has a variable course and can eventually lead to cirrhosis and liver cancer [1]. There has been a rise in the prevalence of NAFLD, and it is currently estimated to affect approximately 1.7 billion individuals worldwide [2]. NAFLD is known to affect several extra-hepatic organs and regulatory pathways, including colorectal cancer (CRC) [3].

CRC is one of the most common cancers in the Western and Asian countries. According to estimates from GLOBOCAN in 2020, CRC is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and second leading cause of death [4]. The most efficient strategies to reduce the incidence of CRC include identifying risk factors for CRC and performing colonoscopy in high-risk populations. Adenomatous colorectal polyps are considered to be precursors of CRC, but in many cases, they are hard to diagnose at an early stage [5].

Several studies have attempted to identify a connection between colorectal polyps and NAFLD. In a cross-sectional study of 3441 patients who underwent colonoscopy, NAFLD was the most important risk factor for colorectal adenoma in females [odds ratio (OR) = 1.43, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.01–2.03, P < 0.05], but not in males [6]. A systematic review that included 142 387 asymptomatic adults confirmed that NAFLD was associated with an increased risk of colorectal polyps (OR = 1.34; 95% CI: 1.23–1.47), including unclassified colorectal polyps, hyperplastic polyps, adenomas, and cancers) [7]. The study, however, had statistically significant heterogeneity (I² = 67.8%; P < 0.001) However, other studies have reported different findings. Nadege et al. [8] found that there was no difference in the prevalence of colorectal adenomas in patients with and without NAFLD.

Currently, there is no consensus regarding screening for CRC in patients with NAFLD. Therefore, our study aimed to investigate the relationship between NAFLD and both colorectal adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps. We further examined associations between NAFLD and colorectal adenomatous and non-adenomatous polyps in both males and females.

Methods

Patients

The medical records of 5096 adults who had a routine health checkup including abdominal ultrasonography and colonoscopy at the First People’s Hospital of Kunshan, China, from January 2018 to December 2022 were retrospectively reviewed. All patients were evaluated by standard questionnaire and physical examination. This study was approved by the ethical committee of the First People’s Hospital of Kunshan, China. The requirement for informed consent was waived as this was a retrospective study that used de-identified secondary data.

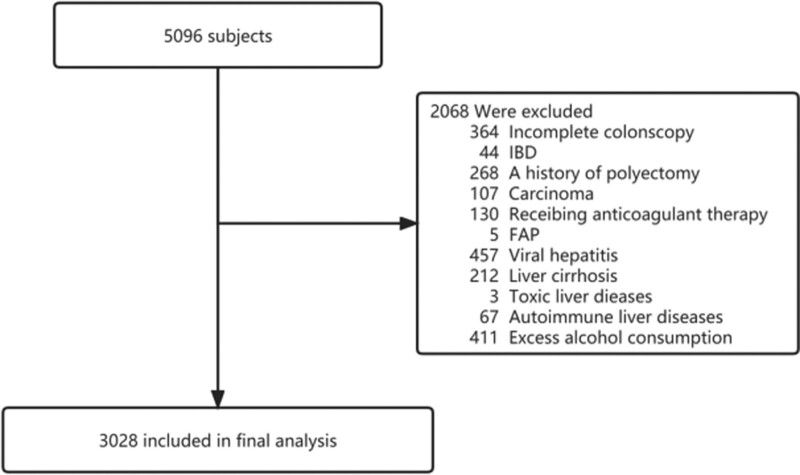

In total, 2068 patients were excluded based on the following reasons: incomplete colonoscopy, inflammatory bowel disease, a history of polypectomy, carcinoma, receiving anticoagulant therapy, familial adenomatous polyposis, viral hepatitis, liver cirrhosis, toxic and autoimmune liver diseases, and excess alcohol consumption (>140 g/week for men; >70 g/week for women). A flow diagram of patient inclusion and exclusion is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of patient inclusion and exclusion. FAP, familial adenomatous polyposis; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease.

Laboratory examination

In all patients, a venous blood sample was collected from the antecubital vein in the morning after fasting for more than 12 h. The white blood cell (WBC) count was measured using a Sysmex XN blood cell analyzer. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), uric acid (UA), and glucose (GLU) levels were measured using routine enzymatic methods with a VITROS 5600 Integrated System.

Colonoscopy and pathological examination

All patients received a bowel preparation before colonoscopy with polyethylene glycol electrolyte powder. Colonoscopies were performed using an OLYMPUS290 colonoscopy system (Tokyo, Japan) by experienced gastroenterologists with more than 5 years of experience performing colonoscopies. A complete colonoscopy examination was defined as the colonoscope reaching the cecum. Colonoscopy features recorded included the absence or presence of polyps. All polyps were biopsied or removed and histologically assessed by experienced pathologists according to the WHO criteria. Based on colonoscopy and pathological findings, patients were divided into 3 groups: polyp-free group, adenomatous polyps, and non-adenomatous polyps.

Abdominal ultrasound

Liver ultrasound was performed with a GE Health LOGIQ P9 color ultrasound machine, and was performed by an experienced sonographer who was blinded to patient colonoscopy and laboratory results. The diagnosis of NAFLD was made according to 2010 guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of NAFLD on the basis of 4 known criteria: (1) The echo intensity of the liver is greater than that of the renal echo intensity; (2) Near field echo dense enhancement and far-field attenuation; (3) The structure of intrahepatic ducts not being clear; and (4) Mild or moderate swelling of the liver.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.6.2. Demographic data and risk factors for colorectal polyps were presented as mean ± SD, or count (percentage). Continuous variables were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test, and categorical variables were compared using Fisher’s exact test. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to analyze risk factors for the prevalence of adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps. A value of P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 2068 of the 5709 patients identified were excluded and 3028 were included in the analysis (Fig. 1).

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Among the 3028 patients, 1109 individuals (36.6%) were diagnosed with adenomatous polyps, while 323 individuals (10.7%) had non-adenomatous polyps. Compared to patients without polyps, patients with adenomatous polyps were older and predominantly male. They exhibited lower ALT levels, and higher levels of TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, UA, and GLU. The frequency of NAFLD was higher in patients with colorectal adenomatous polyps (Table 1). Compared to the polyp-free group, individuals with non-adenomatous polyps were predominantly male. They exhibited lower AST levels, while displaying higher levels of TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, UA, and GLU. Notably, the frequency of NAFLD in patients with non-adenomatous polyps was not higher than in the polyp-free group. Notably, the frequency of NAFLD in patients with non-adenomatous polyps was not higher than the polyp-free group (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects according to colonoscopic findings

| Characteristic | Colonoscopic findings of 3028 subjects | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyp-free | Adenomatous polyps | P-value vs. polyp-free | Non-adenomatous polyps | P-value vs. polyp-free | |

| N (%) | 1596 (52.7) | 1109 (36.6) | 323 (10.7) | ||

| Male | 809 (50.7) | 720 (64.2) | <0.001 | 199 (61.6) | <0.001 |

| Age (yr) | 53.1 ± 15.5 | 56.6 ± 11.5 | <0.001 | 53.2 ± 12.7 | 0.980 |

| WBC (*109/L) | 5.8 ± 2.0 | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 0.007 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 0.144 |

| ALT (U/L) | 27.9 ± 49.1 | 24.8 ± 26.3 | <0.001 | 27.1 ± 19.7 | <0.001 |

| AST (U/L) | 25.6 ± 35.9 | 22.6 ± 12.1 | 0.217 | 23.5 ± 9.4 | 0.015 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.4 ± 1.2 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.7 ± 1.4 | 0.001 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.3 ± 1.1 | 4.7 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 4.6 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.6 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | 2.8 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 0.004 |

| UA (mmol/L) | 307.9 ± 91.2 | 331.4 ± 88.9 | <0.001 | 328.6 ± 87.9 | <0.001 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 1.3 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | <0.001 | 5.5 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| NAFLD (%) | 835 (52.3) | 742 (66.9) | <0.001 | 184 (57.0) | 0.127 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GLU, glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; UA, uric acid.

NAFLD is associated with the prevalence of adenomatous polyps but not non-adenomatous polyps

As shown in Table 2, we found that NAFLD was an independent risk factor for colorectal adenomatous polyps, but not for non-adenomatous polyps, when compared to the polyp-free group. In model I, multinomial logistic regression analysis demonstrated that subjects with NAFLD had a higher prevalence of adenomatous polyps (OR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.6–2.2, P < 0.0001) compared to those without NAFLD. In model II and model III, after adjusting for age, sex, TG, TC, LDL-C, and HDL-C, the adjusted ORs for adenomatous polyps remained significantly increased in subjects with NAFLD (OR = 1.9, 95% CI: 1.6–2.2, P < 0.0001; OR = 1.6, 95% CI: 1.3–1.9, P < 0.0001). However, our multivariate analysis demonstrated no significant association between NAFLD and non-adenomatous polyps (Table 2).

Table 2.

Adjusted ORs and 95%CIs for the occurrence of adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps in relation to NAFLD based on multinomial logistic regression

| Variable | Model I | Model II | Model III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Adenomatous polyps | ||||||

| NAFLD | 1.8 (1.6–2.2) | <0.0001 | 1.9 (1.6–2.2) | <0.0001 | 1.6 (1.3–1.9) | <0.0001 |

| Non-adenomatous polyps | ||||||

| NAFLD | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 0.1272 | 1.2 (1.0–1.6) | 0.0984 | 1.0 (0.8–1.3) | 0.8134 |

Model I is non-adjusted. Model II is adjusted for age and sex. Model III is adjusted for age, sex, TG, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C.

Characteristics in males and females

The characteristics of males and females were examined with respect to laboratory studies, NAFLD, and colorectal polyps (Table 3). Among males, there were no significant differences in WBC count or ALT and AST levels between those with colorectal adenomatous polyps (all, P > 0.01) and those without. However, patients with colorectal adenomatous polyps tended to be older and had higher levels of TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, UA, and GLU, compared to those without polyps. Similarly, patients with non-adenomatous polyps had higher levels of TG, TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, and UA, compared to patients without polyps.

Table 3.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the subjects in males and females according to colonoscopic findings

| Characteristic | Polyp-free | Adenomatous | P-value vs. polyp-free | Non-adenomous | P-value vs. polyp-free |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | |||||

| N | 809 | 720 | 199 | ||

| Age (yr) | 51.7 ± 16.6 | 55.9 ± 11.8 | <0.001 | 52.5 ± 13.5 | 0.562 |

| WBC (*10^9/L) | 6.1 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 0.719 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 0.741 |

| ALT (U/L) | 30.7 ± 45.8 | 26.8 ± 27.9 | 0.468 | 29.2 ± 20.0 | 0.010 |

| AST (U/L) | 25.1 ± 15.8 | 22.9 ± 10.3 | 0.765 | 23.3 ± 8.4 | 0.280 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.5 ± 1.5 | 1.7 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 1.8 ± 1.6 | 0.006 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.0 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 0.9 | <0.001 | 4.4 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | <0.001 | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 0.004 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | <0.001 | 1.3 ± 0.3 | 0.002 |

| UA (mmol/L) | 344.5 ± 89.8 | 361.4 ± 81.8 | <0.001 | 362.9 ± 81.9 | 0.003 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 1.4 | 5.5 ± 1.3 | 0.003 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 0.073 |

| NAFLD | 406 (50.2) | 483 (67.1) | <0.001 | 115 (57.8) | 0.054 |

| Females | |||||

| N | 787 | 389 | 124 | ||

| Age (yr) | 54.6 ± 14.1 | 58.0 ± 10.8 | <0.001 | 54.3 ± 11.3 | 0.962 |

| WBC (*10^9/L) | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 5.5 ± 1.7 | 0.163 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 0.624 |

| ALT (U/L) | 25.1 ± 52.0 | 21.0 ± 22.7 | 0.018 | 23.8 ± 18.9 | 0.032 |

| AST (U/L) | 26.1 ± 46.9 | 22.1 ± 14.9 | 0.589 | 23.9 ± 11.0 | 0.049 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.3 ± 0.9 | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 0.002 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.201 |

| TC (mmol/L) | 4.5 ± 1.0 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | <0.001 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.7 ± 0.8 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.4 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.015 | 1.5 ± 0.3 | 0.004 |

| UA (mmol/L) | 270.5 ± 76.2 | 275.3 ± 73.0 | 0.297 | 273.4 ± 66.5 | 0.259 |

| GLU (mmol/L) | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 5.4 ± 0.9 | <0.001 | 5.4 ± 1.0 | 0.027 |

| NAFLD | 429 (54.5) | 259 (66.6) | <0.001 | 69 (55.6) | 0.814 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; GLU, glucose; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; NAFLD, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; UA, uric acid.

Females with colorectal adenomatous polyps were older and had higher TG, TC, LDL-C, and GLU levels. However, in females, only TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C levels were significantly different between patients with non-adenomatous polyps and those without polyps. Notably, the frequency of NAFLD was not different in males or females with non-adenomatous polyps and those without polyps.

We subsequently performed subgroups analysis by major characteristics of the study population. Table 4 presents the analysis of the relationship between NAFLD and the prevalence of both colorectal adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps through sex subgroup analysis in different groups.

Table 4.

Adjusted ORs and 95% CIs for the occurrence of adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps in relation to NAFLD based on multinomial logistic regression according to different-sex group

| Variable | Model I | Model II | Model III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | OR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Males | ||||||

| Adenomatous polyps | ||||||

| NAFLD | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | <0.0001 | 2.0 (1.7–2.5) | <0.0001 | 1.8 (1.4–2.3) | <0.0001 |

| Non-adenomatous polyps | ||||||

| NAFLD | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 0.0550 | 1.4 (1.0–1.9) | 0.0527 | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 0.4145 |

| Females | ||||||

| Adenomatous polyps | ||||||

| NAFLD | 1.7 (1.3–2.1) | <0.0001 | 1.7 (1.3–2.2) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.0–1.8) | 0.0377 |

| Non-adenomatous polyps | ||||||

| NAFLD | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 0.8136 | 1.0 (0.7–1.5) | 0.8233 | 0.8 (0.6–1.3) | 0.4279 |

Model I is non-adjusted. Model II is adjusted for age. Model III is adjusted for age, TG, TC, LDL-C and HDL-C.

The results demonstrated that after adjusting for age, TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C, NAFLD was found to have an independent association with adenomatous polyps in both males and females. In model I, NAFLD was independently related to adenomatous polys in males (OR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.6–2.5, P < 0.0001) and in females (OR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.3–2.1, P < 0.0001). After adjustment for age (model II), associations between NAFLD and adenomatous polyps were noted in males (OR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.7–2.5, P < 0.0001) and in females (OR = 1.7, 95% CI: 1.3–2.2, P < 0.0001). In model III, after controlling for confounding factors such as age, TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C, the association between NAFLD and adenomatous polyps remained statistically significant in males (OR = 1.8, 95% CI: 1.4–2.3, P < 0.0001) and in females (OR = 1.4, 95% CI: 1.0–1.8, P = 0.0377). However, no significant relationship was noted between NAFLD and non-adenomatous polyps (Table 4).

Discussion

The results of this study showed that NAFLD was significantly associated with the prevalence of colorectal adenomatous polyps as compared to patients without NAFLD. In contrast, there was no association noted between NAFLD and the prevalence of non-adenomatous polyps. In the overall analysis, NAFLD was found to be a risk factor for the prevalence of adenomatous polyps but not for non-adenomatous polyps after adjusting for sex, age, TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C. Subgroup analyses conducted by sex indicated that NAFLD remained a risk factor for adenomatous polyps in both males and females, even after adjusting for age, TG, TC, HDL-C, and LDL-C. However, no significant association was identified between NAFLD and non-adenomatous polyps in either males or females. This study represents the first attempt to investigate the association between ultrasound-diagnosed NAFLD and both colorectal adenomatous and non-adenomatous polyps, in comparison to individuals without polyps.

Previous studies have shown a significant relation between NAFLD and the development of CRC, and also suggest NAFLD should be considered an important factor for determining the need for screening colonoscopy [9–12]. Colorectal polyps, particularly adenomatous polyps (including serrated adenomas), have been shown to be associated with the development of CRC. Thus, it’s important to examine the impact of colorectal adenomatous polyps in patients with NAFLD patients as a prevention for CRC development.

The significant association between NAFLD and colorectal polyps has been recognized by several researchers. Bhatt et al. [13] conducted a retrospective cohort study, and demonstrated that NAFLD was a significant predictor of finding colorectal polyps on colonoscopy (adjusted OR = 2.42; 95% CI: 1.42–4.11; P = 0.001), as well as adenomatous polyps (adjusted OR = 1.95; 95% CI: 1.09–3.48; P = 0.02). However, the relation between NAFLD and non-adenomatous polyps was not examined. Our study offers a more precise elucidation of the association between NAFLD and both colorectal adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps. In a retrospective database study performed in Indonesia, Lesmana et al. [14] examined the data of 138 patients who received a screening colonoscopy and identified that NAFLD was associated with an increased risk of developing any colorectal polyps (adenomatous polyps and non-adenomatous polyps). The disparity in research findings is likely attributable to differences in sample sizes. In addition, Yu et al. [15] conducted a cross-sectional study that included 1538 patients and demonstrated that NAFLD was significantly associated with colorectal polyps, especially multiple polyps, those with a large size, and those with villous features.

NAFLD shares common risk factors with CRC, including central obesity, impaired GLU tolerance, and dyslipidemia [16,17]. The mechanism that links NAFLD to the development of CRC is most likely related to the pro-inflammatory and pro-carcinogenic effect of insulin resistance and the chronic inflammatory status of patients with NAFLD [18,19]. Many studies have indicated that insulin resistance, and similar conditions such as increased levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-1, are related to the risk of CRC [20]. Insulin stimulates the growth of colorectal cells and increases bioactive IGF-1 through regulation of the number of hepatic growth hormone receptors, and reduction of the hepatic secretion of IGF-binding protein 1. Some studies have reported that the levels of plasma inflammatory biomarkers, such as tumor necrosis factor-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and IL-8 are significantly higher in patients with NAFLD than in healthy controls [21]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines can stimulate cell growth, and induce the malignant transformation of cells through regulating immune function [22].

Some studies demonstrated that the association between NAFLD and colorectal adenomas is different in males and females. Seo et al. [6] suggested that NAFLD was significantly associated with a higher risk of colorectal adenomas, and the risk was higher in females than in males. However, Li et al. [23] reported that NAFLD is specifically associated with an increased risk of colorectal adenomatous and hyperplastic polyps in men. In our study, we demonstrated that there was no difference between the association of NAFLD and colorectal adenomatous polyps in males and females. The reasons for different results among studies remain uncertain, but residual confounding by some unmeasured factors may contribute to different results among the studies.

There are several limitations of our study that should be acknowledged. First, the diagnosis of NAFLD was made by ultrasound rather than by liver biopsy. However, the diagnosis of fatty liver based on ultrasound imaging has a sensitivity of 94% and a specificity of 84% [24]. Second, the causality between NAFLD and the risk for colorectal adenomatous is difficult to infer through a cross-sectional study. Third, our study was performed with data from a single center; multi-center research should be performed to confirm the results.

In conclusion, our results clearly demonstrated that NAFLD is associated with the development of colorectal adenomatous polyps in males and females, but is not associated with an increased risk of non-adenomatous polyps. The findings provide new insight into the prevention of CRC in NAFLD patients.

Footnotes

Yingxue Yang and Yajie Teng contributed equally to the writing of this article and should be regarded as co-first authors.

References

- 1.Friedman SL, Neuschwander-Tetri BA, Rinella M, Sanyal AJ. Mechanisms of NAFLD development and therapeutic strategies. Nat Med 2018; 24:908–922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cai J, Zhang XJ, Li H. Progress and challenges in the prevention and control of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Med Res Rev 2019; 39:328–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vanni E, Marengo A, Mezzabotta L, Bugianesi E. Systemic complications of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: when the liver is not an innocent bystander. Semin Liver Dis 2015; 35:236–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021; 71:209–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fearon ER, Vogelstein B. A genetic model for colorectal tumorigenesis. Cell 1990; 61:759–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo JY, Bae JH, Kwak MS, Yang JI, Chung SJ, Yim JY, et al. The risk of colorectal adenoma in nonalcoholic or metabolic-associated fatty liver disease. Biomedicines 2021; 9:1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen W, Wang M, Jing X, Wu C, Zeng Y, Peng J, et al. High risk of colorectal polyps in men with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 35:2051–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Touzin NT, Bush KN, Williams CD, Harrison SA. Prevalence of colonic adenomas in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2011; 4:169–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang X, Wong VW, Yip TC, Tse YK, Liang LY, Hui VW, et al. Colonoscopy and risk of colorectal cancer in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a retrospective territory-wide cohort study. Hepatol Commun 2021; 5:1212–1223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee JM, Park YM, Yun JS, Ahn YB, Lee KM, Kim DB, et al. The association between nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and esophageal, stomach, or colorectal cancer: National population-based cohort study. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0226351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamaguchi M, Hashimoto Y, Obora A, Kojima T, Fukui M. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease with obesity as an independent predictor for incident gastric and colorectal cancer: a population-based longitudinal study. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2019; 6:e000295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang YJ, Bang CS, Shin SP, Baik GH. Clinical impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on the occurrence of colorectal neoplasm: propensity score matching analysis. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0182014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhatt BD, Lukose T, Siegel AB, Brown RS, Jr, Verna EC. Increased risk of colorectal polyps in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease undergoing liver transplant evaluation. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2015; 6:459–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lesmana CRA, Pakasi LS, Sudoyo AW, Krisnuhoni E, Lesmana LA. The clinical significance of colon polyp pathology in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and its impact on screening colonoscopy in daily practice. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 2020:6676294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu X, Xie L, Zhou Y, Yuan X, Wu Y, Chen P. Patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease may be a high-risk group for the development of colorectal polyps: a cross-sectional study. World Acad Sci J 2020; 2. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giovannucci E. Metabolic syndrome, hyperinsulinemia, and colon cancer: a review. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86:s836–s842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siddiqui AA. Metabolic syndrome and its association with colorectal cancer: a review. Am J Med Sci 2011; 341:227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foltyn W, Kos-Kudla B, Strzelczyk J, Matyja V, Karpe J, Rudnik A, et al. Is there any relation between hyperinsulinemia, insulin resistance and colorectal lesions in patients with acromegaly? Neuro Endocrinol Lett 2008; 29:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong VW, Hui AY, Tsang SW, Chan JL, Tse AM, Chan KF, et al. Metabolic and adipokine profile of Chinese patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 4:1154–1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kasprzak A. Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) signaling in glucose metabolism in colorectal cancer. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22:6434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Day CP. From fat to inflammation. Gastroenterology 2006; 130:207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong Y, Gao H, Qi Q, Liu X, Li J, Gao J, et al. High fat diet, gut microbiome and gastrointestinal cancer. Theranostics 2021; 11:5889–5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li Y, Liu S, Gao Y, Ma H, Zhan S, Yang Y, et al. Association between NAFLD and risk of colorectal adenoma in Chinese Han population. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2019; 7:99–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mendler MH, Bouillet P, Le Sidaner A, Lavoine E, Labrousse F, Sautereau D, et al. Dual-energy CT in the diagnosis and quantification of fatty liver: limited clinical value in comparison to ultrasound scan and single-energy CT, with special reference to iron overload. J Hepatol 1998; 28:785–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]