Abstract

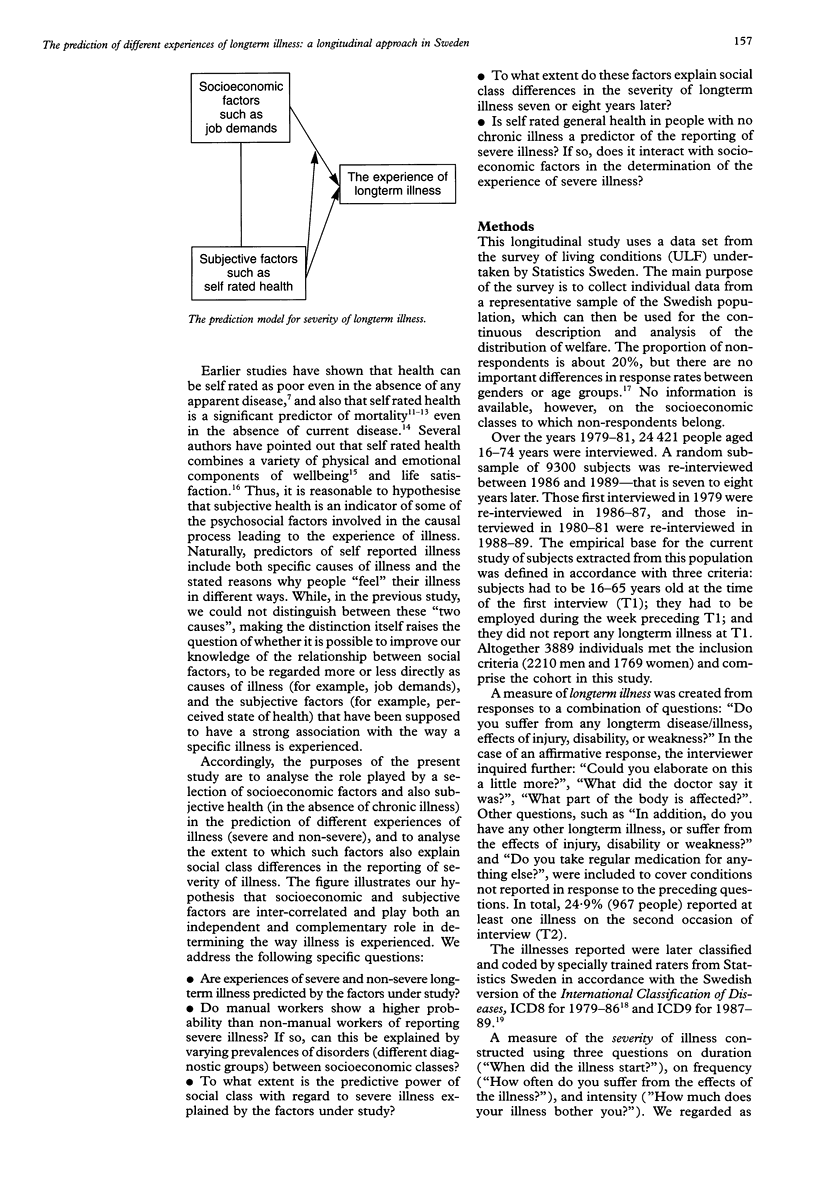

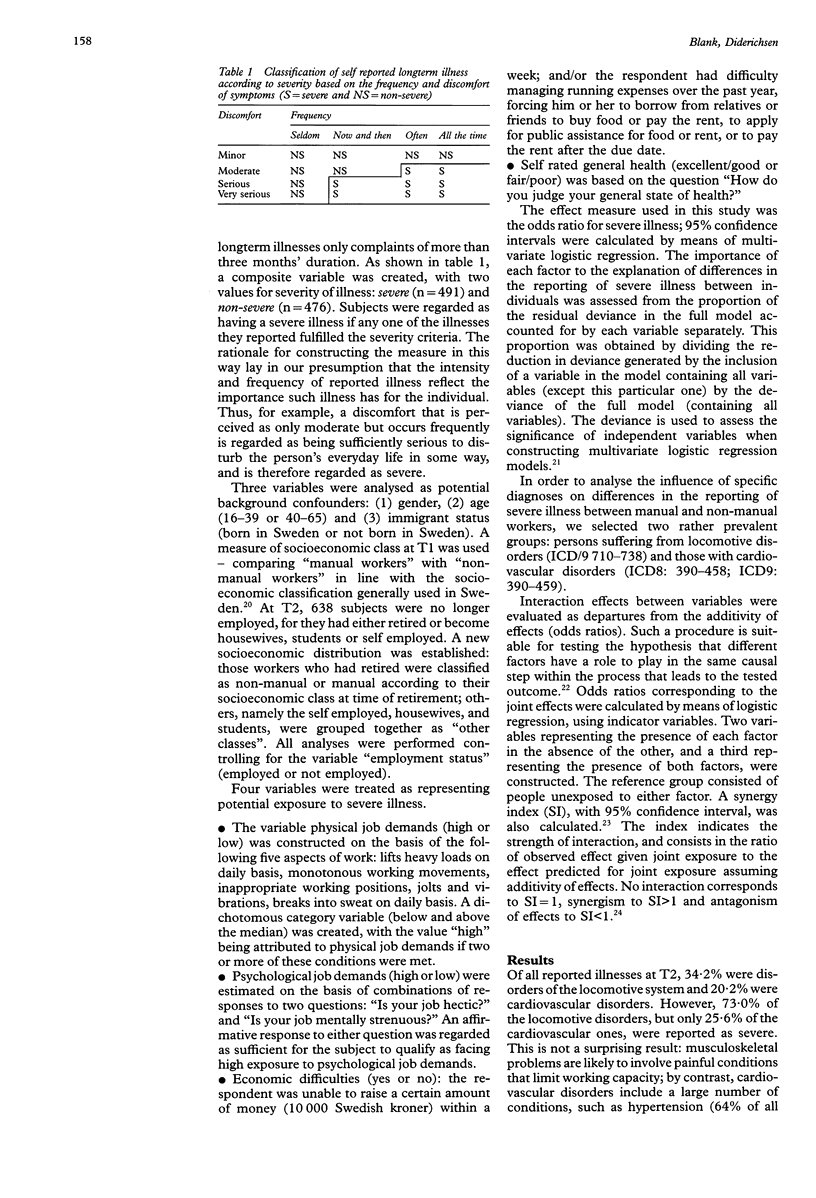

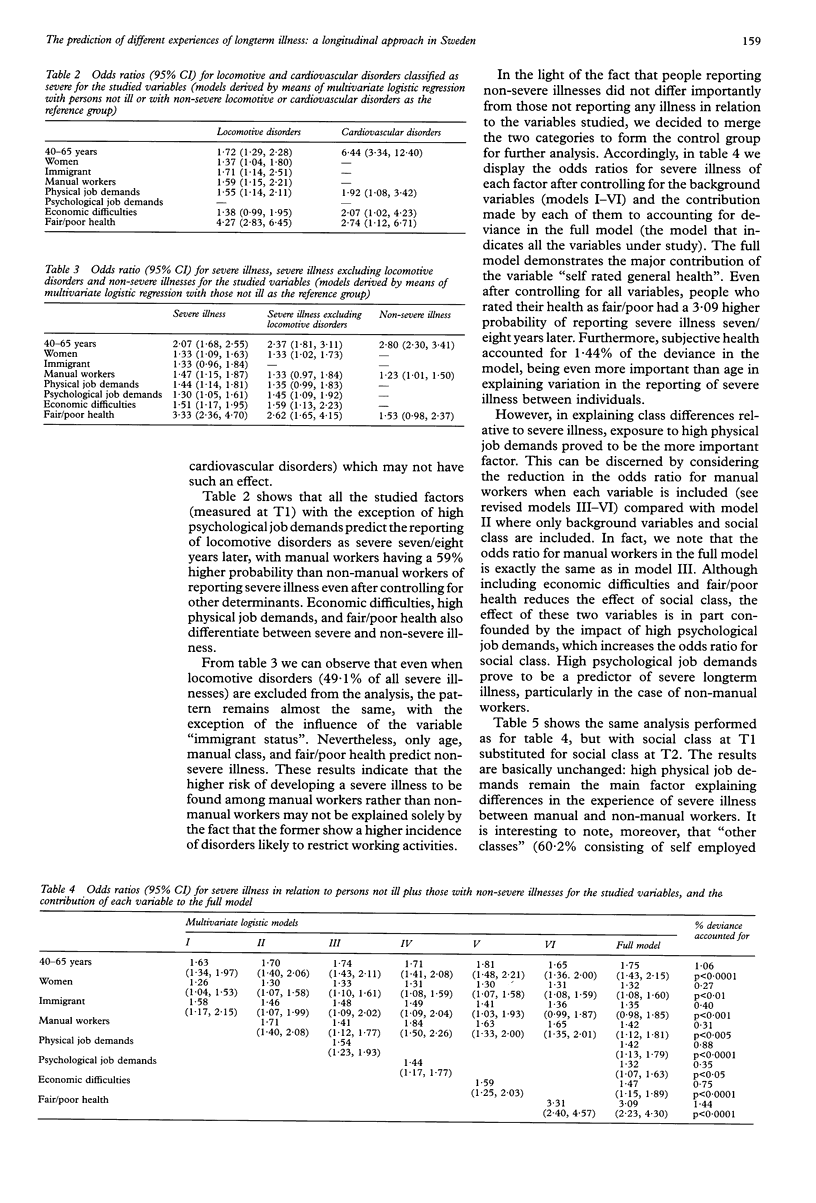

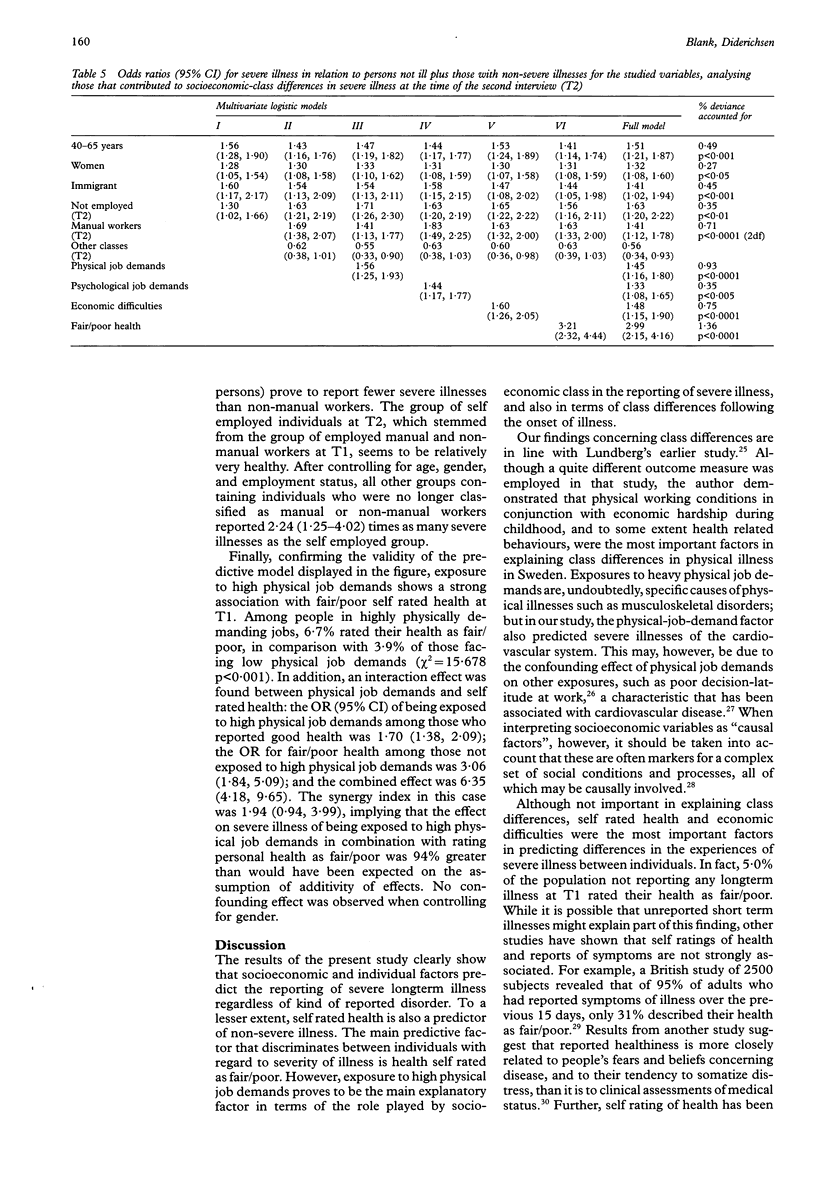

STUDY OBJECTIVE: To analyse the role played by socioeconomic factors and self rated general health in the prediction of the reporting of severe longterm illness, and the extent to which these factors explain social class differences in the reporting of such illness. DESIGN: Analysis of panel data from the survey of living conditions, conducted by Statistics Sweden over the years 1979-81 and 1986-89. SETTING: A random sample of the Swedish population, interviewed in 1979-81 and then re-interviewed in 1986-89. PARTICIPANTS: A representative sample of 3889 employed Swedish people, aged 16-65 years. MAIN RESULTS: Socioeconomic and individual factors predict severe longterm illness regardless of the kind of reported disorder from which the subject suffers. The main predictive factor involved is health self rated as fair/poor, but exposure to high physical job demands proved to be the main explanation of the role played by socioeconomic class. There was a significant interaction effect between self rated general health and physical job demands with regard to the experience of severe illness. CONCLUSIONS: The results of the study strengthen the hypothesis that manual workers are not only more exposed to causes of illness that have important individual and social consequences, but also to the personal factors that determine different experiences of illness. Interaction between these two kinds of factors (job demands and self rated health) suggests that socioeconomic and individual factors play different but complementary roles in the causal process leading to the experience of severe longterm illness.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barsky A. J., Cleary P. D., Klerman G. L. Determinants of perceived health status of medical outpatients. Soc Sci Med. 1992 May;34(10):1147–1154. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90288-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. Evidence on inequality in health from a national survey. Lancet. 1987 Jul 4;2(8549):30–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)93062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Health Illn. 1982 Jul;4(2):167–182. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.ep11339939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrity T. F., Somes G. W., Marx M. B. Factors influencing self-assessment of health. Soc Sci Med. 1978 Mar;12(2A):77–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L., Angel R. J. Self-rated health and mortality in the NHANES-I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Public Health. 1990 Apr;80(4):446–452. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.4.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R., Baker D., Marxer F., Ahlbom A., Theorell T. Job decision latitude, job demands, and cardiovascular disease: a prospective study of Swedish men. Am J Public Health. 1981 Jul;71(7):694–705. doi: 10.2105/ajph.71.7.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman A., Eisenberg L., Good B. Culture, illness, and care: clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research. Ann Intern Med. 1978 Feb;88(2):251–258. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-88-2-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg O. Causal explanations for class inequality in health--an empirical analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32(4):385–393. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90339-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macintyre S. The patterning of health by social position in contemporary Britain: directions for sociological research. Soc Sci Med. 1986;23(4):393–415. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(86)90082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossey J. M., Shapiro E. Self-rated health: a predictor of mortality among the elderly. Am J Public Health. 1982 Aug;72(8):800–808. doi: 10.2105/ajph.72.8.800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okun M. A., Stock W. A., Haring M. J., Witter R. A. Health and subjective well-being: a meta-analysis. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1984;19(2):111–132. doi: 10.2190/QGJN-0N81-5957-HAQD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmore E., Luikart C. Health and social factors related to life satisfaction. J Health Soc Behav. 1972 Mar;13(1):68–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothman K. J., Greenland S., Walker A. M. Concepts of interaction. Am J Epidemiol. 1980 Oct;112(4):467–470. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson W. D. Statistical analysis of case-control studies. Epidemiol Rev. 1994;16(1):33–50. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R. J., Noh S. Physical disability and depression: a longitudinal analysis. J Health Soc Behav. 1988 Mar;29(1):23–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dalen H., Williams A., Gudex C. Lay people's evaluations of health: are there variations between different subgroups? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1994 Jun;48(3):248–253. doi: 10.1136/jech.48.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]