Abstract

The oxazolidinones represent a new class of antimicrobial agents which are active against multidrug-resistant staphylococci, streptococci, and enterococci. Previous studies have demonstrated that oxazolidinones inhibit bacterial translation in vitro at a step preceding elongation but after the charging of N-formylmethionine to the initiator tRNA molecule. The event that occurs between these two steps is termed initiation. Initiation of protein synthesis requires the simultaneous presence of N-formylmethionine-tRNA, the 30S ribosomal subunit, mRNA, GTP, and the initiation factors IF1, IF2, and IF3. An initiation complex assay measuring the binding of [3H]N-formylmethionyl-tRNA to ribosomes in response to mRNA binding was used in order to investigate the mechanism of oxazolidinone action. Linezolid inhibited initiation complex formation with either the 30S or the 70S ribosomal subunits from Escherichia coli. In addition, complex formation with Staphylococcus aureus 70S tight-couple ribosomes was inhibited by linezolid. Linezolid did not inhibit the independent binding of either mRNA or N-formylmethionyl-tRNA to E. coli 30S ribosomal subunits, nor did it prevent the formation of the IF2–N-formylmethionyl-tRNA binary complex. The results demonstrate that oxazolidinones inhibit the formation of the initiation complex in bacterial translation systems by preventing formation of the N-formylmethionyl-tRNA–ribosome–mRNA ternary complex.

The oxazolidinones represent a new synthetic class of antibacterial agents with activity against gram-positive organisms (1). Studies have shown that the oxazolidinones linezolid and eperezolid are active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, and vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium (7, 14, 15, 18, 28). Linezolid is entering phase III clinical testing as a therapeutic agent that is effective against skin and skin structure infections, bacteremia, and pneumonia caused by gram-positive pathogenic bacteria.

The antimicrobial activities of the oxazolidinones were first described by scientists at E. I. Dupont de Nemours & Co., Inc. (4, 26). It was demonstrated that the oxazolidinone DuP-721 inhibited protein synthesis in live bacteria (5), but cell-free translation was not affected (6). However, recent studies have shown that linezolid and eperezolid are potent inhibitors of cell-free translation and that the ability to demonstrate inhibition was dependent upon the concentration of mRNA (25). It was also determined that eperezolid did not inhibit the formation of N-formylmethionyl-tRNA (tRNAfMet), elongation, or termination reactions of bacterial translation (17, 25). Linezolid was not active against clinical isolates of Escherichia coli (MICs, >128 μg/ml), but for strains whose cell walls were made permeable through mutagenesis (25) or genetic knockout of the AcrAB efflux pump (3), the linezolid MICs were 4 μg/ml.

The activity of linezolid against multidrug-resistant gram-positive pathogens suggests that this compound has unique mechanisms of action. Our current findings present direct evidence that oxazolidinones inhibit the initiation of protein synthesis by preventing the formation of the tRNAfMet-mRNA-70S (or 30S) subunit ternary complex.

(This study was presented in part at the 37th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 28 September to 1 October 1997.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and buffers.

Streptomycin, kasugamycin, alumina, and E. coli tRNA were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, Mo.). Linezolid was prepared as described earlier (1) and was dissolved in deionized water at concentrations up to 2 mM before it was added to initiation complex reactions. [3H]tRNAfMet (9.7 Ci/mmol) was purchased from New England Nuclear Life Sciences Products (Boston, Mass.), and [35S]tRNAfMet was synthesized as described by Ganoza et al. (9). AUG was synthesized by the method of Nielson et al. (20). The oligoribonucleotide used in the S. aureus initiation complex assays had the sequence 5′-rGGGAAUUCGGAGGUUUAAAAAUGGGUAAA-3′ and was purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, Iowa). l-[35S]methionine (1,000 Ci/mmol) was purchased from Amersham Corp. (Arlington Heights, Ill.). The compositions of the buffers used in this study were as follows: buffer A, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 30 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM dithiothreitol (DTT); buffer B, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 M NH4Cl, and 1 mM DTT; buffer C, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5 M NH4Cl, and 1 mM DTT.

Bacterial strains and media.

E. coli MRE600 (ATCC 29417) and S. aureus RN4220 (16) were grown in Lennox L Broth (Gibco BRL, Gaithersburg, Md.) at 37°C. Alternatively, E. coli MRE600 cells were obtained from the University of Alabama Fermentation Facility, Birmingham.

Preparation of E. coli 70S ribosomes.

Ribosomes were prepared by the method of Rheinberger et al. (22). Fifty grams (wet weight) of frozen MRE600 cells was mixed with an equal weight of alumina, and the cells were lysed at 0°C by grinding with a mortar and pestle. Fifty milliliters of buffer A containing 1 μg of DNase (RNase-free; Worthington, Freehold, N.J.) per ml was added and the suspension was stirred for 20 min. The alumina, unbroken cells, and cellular debris were removed by two centrifugations at 10,000 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was centrifuged again for 30 min at 30,000 × g, and the upper two-thirds of the resulting supernatant was centrifuged again at 30,000 × g for 16 h (S30 extract). The ribosome pellet was suspended in buffer B and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min, and the clear supernatant was centrifuged at 105,000 × g for 4 h. The pelleted ribosomes were washed twice more in buffer C while maintaining the ribosomes at 5 to 10 mg/ml (14.4 A260 units = 1 mg/ml), suspended in buffer A at 80 to 100 mg of ribosomes per ml, and stored at −80°C.

Preparation of E. coli ribosomal subunits.

Ribosomal subunits were prepared as described by Staehelin and Maglott (27), with the following modifications. The S30 extract was prepared as described above by using MRE600 mid-logarithmic-phase cells, and the 30S subunits were stored in liquid nitrogen.

Preparation of S. aureus ribosomes.

S. aureus cells (50 g [wet weight]) were resuspended in 100 ml of lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM NaCl, 2 mg of lysostaphin per ml, 10,000 U of DNase I [Boehringer Mannheim, Indianapolis, Ind.]) and incubated for 1 h in a 37°C water bath. β-Mercaptoethanol was added to a final concentration of 5 mM, and the lysed cells were centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min to remove unbroken cells and cell fragments. The supernatant was centrifuged at 30,000 × g, and the resulting supernatant was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 16 h to pellet the ribosomes. The ribosome pellet was resuspended in buffer B and was again centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 16 h. The pellet was resuspended in buffer A, applied to linear 5 to 40% (wt/vol) sucrose gradients prepared in buffer A, and centrifuged for 16 h in a Beckman SW28 rotor. Gradients were fractionated; and the 70S ribosomes were pooled, pelleted at 300,000 × g for 5 h, and resuspended in buffer A before they were stored at −80°C.

Initiation factor assays.

Initiation factors were assayed as described by Hershey et al. (13). Complexes between IF2 and tRNAfMet were formed in the reaction mixtures (final volume, 65 μl) containing 190 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 19 mM MgCl2, 3.8 mM DTT, 1.9 mM GTP, 540 mM NH4Cl, 5 pmol of IF2, and 2 μl of [35S]tRNAfMet (10,000 dpm). Duplicate reaction mixtures were incubated for 10 min at 37°C, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 1 ml ice-cold buffer A containing 1% glutaraldehyde. Complexes were trapped on Millipore HA filters (pore size, 0.45 μm), washed with 50 ml of buffer A containing 1% glutaraldehyde, and counted after the addition of liquid scintillation fluid.

Synthesis of [32P]mRNA for ribosome binding studies.

The one-step PCR procedure described by Sandhu et al. (24) was used to synthesize a 200-bp mRNA with a defined sequence. Four adjacent oligonucleotide primers with short overlaps were annealed to each other and were subjected to PCR. The primer sequences were as follows (primer sequences are 5′ to 3′): primer 1, GGGAATTCGCAGGTTTAAAAATGAAAGGTAAAGGTAAAGGTAAA; primer 2, GGTGGTGGCCTGGGCAAAGGTAAAGGT; primer 3, AAAGGT AAAAAAGGTAAAGGTAAAGGTAAAAAAGGTAAAAAAGGTAAAGG TGGTGGTTAATAAAAAAAATAAAAAG; and primer 4, CTAGAGGATCCTTTTTATTTTTTTATTAACCACCAC. Primers 1 and 2 were annealed to the sequence 5′-ACCTTTTTTACCTTTACCTTTACCTTTTTTACCTTTTTTACCTTTACCTTTACCTTATCCTTTACCTTTGCCCAGGCCAC-3′. Primer 3 was annealed to the sequence 5′-ACCTTTGCCCAGGCCACCACCTTTACCTTTTTTACCTTTTTTACCTTTACCTTCACC-3′, and primer 4 was annealed to primer 3. Extension by PCR resulted in the asymmetric synthesis of intermediates which annealed to each other, thereby priming the synthesis of a double-stranded DNA template. This template was subsequently used to produce an mRNA with the sequence 5′-GGGAAUUCGGAGGUUUAAAAAUG-(GGUAAA)33UAAUAA-3′ (the Shine-Dalgarno sequence and the AUG start codon are underlined). The coding sequence contained Gly (GGU) and Lys (AAA) codons followed by tandem stop codons. [32P]mRNA was transcribed with a Ribomax kit (Promega, Madison, Wis.) and either [32P]CTP or [32P]GTP. RNA was isolated by phenol extraction and chromatography through a Quick Spin G-25 column (Boehringer Mannheim).

Binding of labeled synthetic mRNA to ribosomes.

Binding of 32P-labeled synthetic mRNA was carried out for 15 min at 24°C in duplicate 50-μl reaction mixtures containing 200 to 400 μg of 70S ribosomes, 20 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM DTT, 80 mM NH4Cl, and 1 μl (16,000 dpm) of 32P-labeled mRNA. Duplicate reactions were terminated by the addition of 1 ml of ice-cold buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 20 mM MgCl2, and 100 mM NH4Cl. The mRNA-ribosome complex was then trapped on Millipore HA filters, and the radioactivity was counted after the addition of scintillation fluid.

E. coli initiation complex assay with AUG.

E. coli 70S ribosomes (10 pmol) were incubated with [35S]tRNAfMet (45,000 dpm) in 20-μl reaction mixtures containing 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 3 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NH4Cl, 4 mM DTT, 0.05 mM spermine, 2 mM spermidine, and 0.25 μg of the AUG trinucleotide. Duplicate reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 10 min, and the reactions were stopped by the addition of 2 ml of cold buffer A. Complexes were filtered through Millipore filters (pore size, 0.45 μm) and washed with 50 ml of buffer A, and the radioactivity was counted after the addition of scintillation fluid.

S. aureus initiation complex assay.

S. aureus 70S ribosomes (10 pmol) were incubated with 9 pmol of [3H]tRNAfMet in duplicate 100-μl reaction mixtures containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MgCl2, 30 mM NH4Cl, 1 mM DTT, and 100 pmol of oligoribonucleotide (5′-rGGGAAUUCGGAGGUUUAAAAAUGGGUAAA-3′). The incubation temperature, incubation time, and filter assay were as described above for E. coli complexes formed with AUG.

Isolation of initiation factors.

Initiation factors were isolated as described by Hershey et al. (13), as modified by Ganoza et al. (8). IF1, IF2, and IF3 were stored in liquid N2.

Initiation complex assay with defined mRNA.

Complexes were formed in a 20-μl volume with 4 pmol of either 70S or 30S ribosomes, 4 pmol of the appropriate initiation factor(s), 4 pmol of unlabeled synthetic mRNA, [35S]tRNAfMet (18,000 dpm [30S] or 4,500 dpm [70S]), 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 3 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NH4Cl, 4 mM DTT, 0.05 mM spermine, and 2 mM spermidine. Duplicate reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 15 min, the reactions were stopped with 1 ml of ice-cold buffer A, and the complex was trapped on Millipore HA filters as described above.

RESULTS

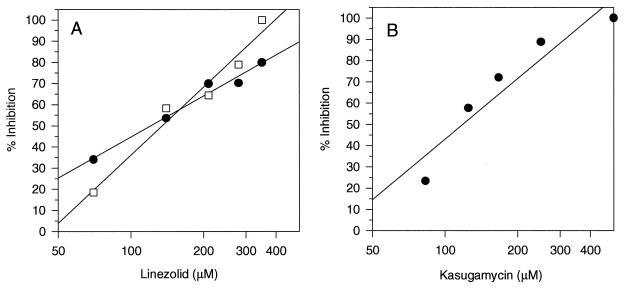

Initiation of translation requires the formation of a ternary complex between tRNAfMet, the 30S or the 70S subunit, and mRNA. This initiation complex can be assayed by measuring the binding of radiolabeled tRNAfMet to either the 30S or the 70S subunit. Figure 1A shows that in the presence of the initiation factors IF1, IF2, and IF3, linezolid had 50% inhibitory concentrations (IC50s) of 110 μM (37 μg/ml) and 130 μM (44 μg/ml) for E. coli 30S and 70S initiation complex formation, respectively. The integrity of the assay was confirmed by demonstrating that kasugamycin was inhibitory to 70S initiation complex formation, with an IC50 of 154 μM (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

(A) Linezolid inhibition of E. coli initiation complexes formed in the presence of IF1, IF2, IF3, and the defined mRNA described in Materials and Methods. Either 30S (•) or 70S (□) initiation complexes were formed by using stoichiometric amounts of each initiation factor and the appropriate ribosomal subunit. The complexes were allowed to form for 10 min at 37°C. (B) Kasugamycin inhibition of E. coli 70S initiation complex formation.

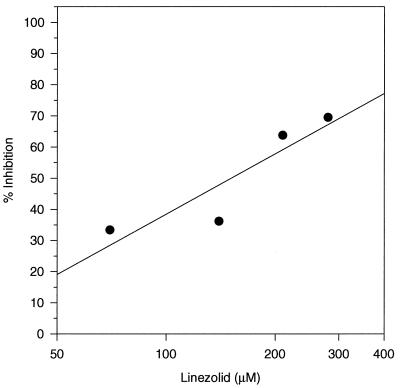

Oxazolidinone inhibition of initiation complex formation was studied further with S. aureus 70S ribosomes (Fig. 2). With a truncated mRNA, an IC50 value of 116 μM was obtained for linezolid. These reactions were performed in the absence of initiation factors and with salt-washed 70S ribosomes.

FIG. 2.

Inhibition of S. aureus 70S translation initiation complex formation by linezolid. [3H]tRNAfMet binding to 70S ribosomal subunits was measured in the presence of the defined oligoribonucleotide described in Materials and Methods. Complexes were allowed to form for 10 min at 37°C.

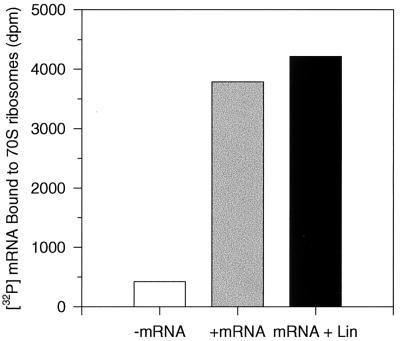

Formation of the ternary initiation complex of tRNAfMet-ribosome-mRNA requires that both the initiator tRNA and mRNA bind to their respective sites on the ribosome and that they form codon-anticodon hydrogen bonds with each other (10, 12). The ability of linezolid to disrupt initiation complex formation by inhibiting the binding of mRNA to the ribosome was examined. Figure 3 shows that 200 μM linezolid did not inhibit the binding of a 200-bp synthetic mRNA to the ribosome.

FIG. 3.

Lack of effect of linezolid on mRNA binding to ribosomes. (A) Purified E. coli 70S ribosomes and [32P]mRNA (defined sequence of 200 bp) were incubated for 15 min at 24°C in the presence or absence of 200 μM linezolid (Lin) before trapping the complex on nitrocellulose filters.

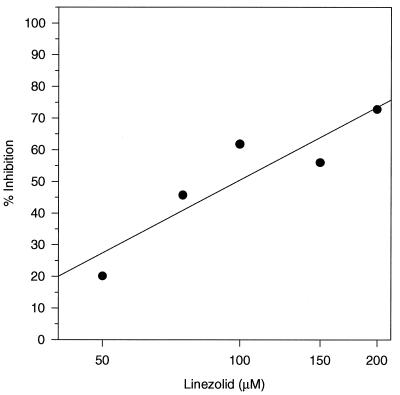

Initiation factors IF1, IF2, and IF3 play important roles in the initiation of translation in bacteria. The tRNAfMet is bound by IF2 and is delivered to the 30S subunit joining IF1, IF3, and the mRNA as part of the initiation complex. Linezolid did not inhibit formation of the IF2-tRNAfMet complex when either 5 or 0.5 pmol of E. coli IF2 was used (Table 1). The role of initiation factors in the mechanism of action of linezolid was further investigated by forming E. coli 70S ribosome initiation complexes in the absence of any of the three factors. Figure 4 demonstrates that an IC50 of 152 μM was obtained for linezolid under these conditions.

TABLE 1.

Effect of linezolid on IF2-tRNAfMet binary complex formationa

| Sample | Concn (μM) | dpm obtained with IF2 at the following concn:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 pmol | 5 pmol | ||

| Control | 0 | 851 | 10,426 |

| Linezolid | 200 | 765 | 12,980 |

Duplicate reaction mixtures containing either 0.5 or 5 pmol of purified E. coli IF2 and 10,000 dpm of [35S]tRNAfMet were incubated for 10 min at 37°C and were trapped on Millipore filters as described in Materials and Methods.

FIG. 4.

Effect of linezolid on E. coli 70S initiation complexes formed in the absence of initiation factors with the triplet codon AUG used as the source of mRNA. Initiation complex formation was as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

Initial studies by Eustice et al. (5) demonstrated that the oxazolidinone DuP-721 inhibited protein synthesis in whole cells, but subsequent studies failed to show that cell-free translation was targeted by this class of antibacterial agents (6). Interest in this class of compounds waned as DuP-721 did not advance in clinical trials. The synthesis of U-100592 (eperezolid) and U-100766 (linezolid) by Brickner et al. (1) and the demonstration of their favorable activity profiles in vitro and in vivo against multidrug-resistant gram-positive pathogens (7, 14, 15, 18, 28) have resulted in renewed interest in the oxazolidinones. Recent mechanism-of-action studies have shown that eperezolid and linezolid do not inhibit the synthesis of tRNAfMet, elongation, or termination reactions of translation (25). Oxazolidinones compete with chloramphenicol and lincomycin for binding to the 50S subunit (17), but neither elongation nor the synthesis of the first peptide bond between tRNAfMet and puromycin is inhibited.

Two pathways may be used to initiate protein synthesis in E. coli (11, 12). In the first pathway, the 30S subunit interacts with the mRNA; in the second pathway, the 30S subunit interacts first with tRNAfMet. Both pathways result in the formation of a preinitiation complex comprising the mRNA, the 30S subunit, and tRNAfMet. In vivo, initiation factors IF1, IF2, and IF3 are essential to this process. They markedly increase the efficiency of formation of each of these pathways and promote the conversion of the preinitiation complex to the postinitiation complex. In this study, linezolid inhibited the formation of E. coli 30S initiation complexes and 70S complexes from either E. coli or S. aureus. Despite the essential function of initiation factors for in vivo translation, they were not required for linezolid to inhibit the initiation complex formation in E. coli. Due to a lack of purified S. aureus initiation factors, their effect on linezolid potency could not be assessed in this study. To our knowledge, this is the first report of initiation complex formation with S. aureus ribosomes.

It is interesting that similar IC50s were obtained for ribosomes from gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria by using either AUG or a 200-bp synthetic mRNA (E. coli) or a truncated mRNA (S. aureus). The truncated mRNA used for S. aureus initiation complex formation was identical to the first 26 bp of the 200-bp synthetic mRNA used for the E. coli studies. The similar potency of linezolid for either of these systems indicates that (i) the length of the mRNA is not critical and at least an AUG is required, (ii) a Shine-Dalgarno sequence may not be essential, and (iii) the binding site for linezolid is conserved in both gram-negative and gram-positive bacterial systems.

After establishing that oxazolidinones inhibited initiation complex formation, further studies were designed to examine the effect of linezolid on isolated initiation events. IF2 forms a binary complex with tRNAfMet, guiding it to the P site of the ribosome where it can bond with the initiation codon of the mRNA (11). High concentrations (200 μM) of linezolid did not inhibit binary complex formation, indicating that the binary complex reaction is probably not the target of oxazolidinones. After IF2 guides initiator tRNA to the P site, an initiation complex can be formed in the presence of mRNA. An mRNA sequence containing a strong Shine-Dalgarno site followed by seven bases, the AUG start codon, and a coding sequence was synthesized. To foster the formation of the initiation complex, the mRNA was constructed so as to minimize the potential secondary structure of the initiation site. With this [32P]mRNA with a defined sequence, it was demonstrated that 200 μM linezolid did not inhibit mRNA binding to ribosomes.

The potencies and mechanisms of action of other drugs which inhibit translation initiation have been examined. Okuyama et al. (21) reported that 30S complexes were inhibited 62% with 100 μM kasugamycin when the random polymer polyAUG was used as the mRNA template and that 70S complex formation was inhibited 100% when the drug was used at 200 μM. Similar results were observed in this study, in which the IC50 of kasugamycin was 154 μM when the same E. coli 70S ribosome preparation for which the linezolid IC50 was 110 μM was used. Translation initiation is a complex, dynamic event involving the interaction of several components (initiation factors, mRNA, ribosome, tRNAfMet) which, upon binding, alter the structure of the ribosome. As a result, as the in vitro assays move away from coupled transcription-translation, the IC50s increase. For example, the linezolid IC50 for coupled transcription-translation is 1.8 μM, the IC50 for translation is 15 μM (25), and the value for 70S initiation complex inhibition is 110 μM (this study). Likewise, at a concentration of 10 μM kasugamycin inhibits f2 phage RNA-directed translation 50% (21), while the IC50 for initiation complex inhibition was 154 μM (this study).

Eustice et al. (6) reported that 100 μM DuP-721 did not inhibit E. coli 70S initiation complex formation. In addition, Burghardt et al. (2) recently reported that 230 μM DuP-721 did not inhibit Staphylococcus carnosus initiation complex formation. While DuP-721 was not tested in this study, we have previously demonstrated that 250 μM DuP-721 was required to achieve only 20% inhibition of cell-free translation (25). Therefore, millimolar concentrations of DuP-721 may be required in vitro in order to inhibit initiation complex formation.

By using an assay validated with an antibiotic (kasugamycin) with a defined mechanism of action, this study demonstrates that oxazolidinones inhibit initiation complex formation. This conclusion is further supported by the lack of activity of this class of antibacterial agents against other reactions of translation such as tRNAfMet biosynthesis, as well as elongation and termination (6, 17, 25). It has been reported that linezolid and eperezolid bind to isolated 50S subunits (but not to 30S subunits) and that chloramphenicol and lincomycin compete with this binding (17). However, formation of the tRNAfMet-puromycin peptide bond was not inhibited by these oxazolidinones. Recently, Burghardt et al. (2) reported that DuP-721 inhibited the puromycin-mediated release of tRNAfMet from S. carnosus 70S initiation complexes approximately 50% when 80 μg of DuP-721 per ml (290 μM) was used. While these data indicate very weak inhibition of the peptidyl transferase reaction, taken together with the results of the present study, the collective data suggest that oxazolidinone binding is partitioned between both subunits. The binding of tRNAfMet to the 70S particle occurs through codon-anticodon interactions on the 30S subunit as well as through contacts with the peptidyl transferase region of the 50S particle (23). We postulate that the drug distorts the binding site for the initiator-tRNA which overlaps both ribosomal subunits. Analysis of ribosomes from a laboratory-generated S. aureus isolate resistant to the oxazolidinone eperezolid (19) may provide information regarding the binding site(s) for this new class of antibacterial agents.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mary Meissner for secretarial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. We also thank Susan Poppe and Cheryl Quinn for critical review.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brickner S J, Hutchinson D K, Barbachyn M R, Manninen P R, Ulanowicz D A, Garmon S A, Grega K C, Hendges S K, Toops D S, Zurenko G E, Ford C W. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of U-100592 and U-100766, two oxazolidinone antibacterial agents for the potential treatment of multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacterial infections. J Med Chem. 1996;39:673–679. doi: 10.1021/jm9509556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burghardt H, Schimz K L, Muller M. On the target of a novel class of antibiotics, oxazolidinones, active against multidrug-resistant gram-positive bacteria. FEBS Lett. 1998;425:40–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00194-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buysse J M, Demyan W F, Dunyak D S, Stapert D, Hamel J C, Ford C W. Program and abstracts of the 36th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1996. Mutation of the AcrAB antibiotic efflux pump in Escherichia coli confers susceptibility to oxazolidinone antibiotics, abstr. C-42; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daly J S, Eliopoulos G M, Wiley S, Moellering R C., Jr Mechanism of action and in vitro and in vivo activities of S-6123, a new oxazolidinone compound. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1341–1346. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.9.1341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eustice D C, Feldman P A, Slee A M. Mechanism of action of DuP 721, a new antibacterial agent: effects on macromolecular synthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1988;150:965–971. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(88)90723-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eustice D C, Feldman P A, Zajac I, Slee A M. Mechanism of action of DuP 721: inhibition of an early event during initiation of protein synthesis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:1218–1222. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.8.1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ford C W, Hamel J C, Wilson D M, Moerman J K, Stapert D, Yancey R J, Jr, Hutchinson D K, Barbachyn M R, Brickner S J. In vivo activities of U-100592 and U-100766, novel oxazolidinone antimicrobial agents, against experimental bacterial infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1508–1513. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.6.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ganoza M C, Aoki H, Burkhardt N, Murphy B J. The ribosome as “affinity matrix”: efficient purification scheme for translation factors. Biochimie. 1996;78:51–61. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(96)81329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganoza M C, Barracluogh N, Wong J T. Purification and properties of an N-formylmethionyl-tRNA hydrolase. Eur J Biochem. 1976;65:613–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1976.tb10379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold L. Post-transcriptional regulatory mechanisms in E. coli. Annu Rev Biochem. 1988;57:199–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.57.070188.001215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gualerzi C O, Severini M, Spurio R, La Teana A, Pon C L. Molecular dissection of translation initiation factor IF2. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:16356–16362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gualerzi C O, Teana A L, Spurio R, Canonaco M A, Severini M, Pon C L. Initiation of protein biosynthesis of procaryotes: recognition of mRNA by ribosomes and molecular basis for the function of the initiation factors. In: Hill W E, editor. The ribosome: structure, function, and evolution. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1990. pp. 281–291. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hershey J W B, Yanov J, Fakunding Z. Purification of protein synthesis initiation factors IF1, IF2, and IF3 from Escherichia coli. Methods Enzymol. 1979;60:3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(79)60003-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones R N, Johnson D M, Erwin M E. In vitro antimicrobial activities and spectra of U-100592 and U-100766, two novel fluorinated oxazolidinones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:720–726. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaatz G W, Seo S M. In vitro activities of oxazolidinone compounds U-100592 and U-100766 against Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:799–801. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.3.799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kreiswirth B N, Lofdahl S, Betley M J, O’Reilly M, Shlievert P M, Bergdoll M S, Novick R P. The toxic shock syndrome exotoxin structural gene is not detectably transmitted by prophage. Nature. 1983;305:709–712. doi: 10.1038/305709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin A H, Murray R W, Schaadt R D, Zurenko G E, Dunyak D S, Buysse J M, Marotti K R. The oxazolidinone eperezolid binds to the 50S ribosomal subunit and competes with binding of chloramphenicol and lincomycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2127–2131. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mason E O, Lamberth L B, Kaplan S L. In vitro activities of oxazolidinones U-100592 and U-100766 against penicillin-resistant and cephalosporin-resistant strains of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:1039–1040. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray R W, Schaadt R D, Zurenko G E, Marotti K R. Ribosomes from an oxazolidinone-resistant mutant confer resistance to eperezolid in a Staphylococcus aureus cell-free transcription-translation assay. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:947–950. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.4.947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nielson T, Gregoire R J, Fraser A R, Kofoid E C, Ganoza M C. Synthesis of biologically active portions of an intercistronic region by use of a new 3′-phosphate incorporation method to protect 3′-OH and their binding to ribosomes. Eur J Biochem. 1979;99:489–437. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1979.tb13273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Okuyama A, Machiyama N, Kinoshita T, Tanaka N. Inhibition by kasugamycin of initiation complex formation on 30S ribosomes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1971;43:196–199. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(71)80106-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rheinberger H J, Geigenuller U, Wedde M, Nierhaus K H. Parameters for the preparation of Escherichia coli ribosomes and ribosomal subunits active in tRNA binding. Methods Enzymol. 1988;164:659–662. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(88)64076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Samaha R R, Green R, Noller H F. A base pair between tRNA and 23S rRNA in the peptidyl transferase centre of the ribosome. Nature. 1995;377:309–314. doi: 10.1038/377309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sandhu G S, Aleff R A, Kline B C. Dual asymmetric PCR: one-step construction of synthetic genes. BioTechniques. 1992;12:14–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinabarger D L, Marotti K R, Murray R W, Lin A H, Melchior E P, Swaney S M, Dunyak D S, Demyan W F, Buysse J M. Mechanism of action of oxazolidinones: effects of linezolid and eperezolid on translation reactions. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:2132–2136. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.10.2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slee A M, Wuonola M A, McRipley R J, Zajac I, Zawada M J, Bartholomew P T, Gregory W A, Forbes M. Oxazolidinones, a new class of synthetic antibacterial agents: in vitro and in vivo activities of DuP105 and DuP721. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:1791–1797. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.11.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Staehelin T, Maglott D R. Preparation of Escherichia coli ribosomal subunits active in polypeptide synthesis. Methods Enzymol. 1971;20:449–455. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zurenko G E, Yagi B H, Schaadt R D, Allison J W, Kilburn J O, Glickman S E, Hutchinson D K, Barbachyn M R, Brickner S J. In vitro activities of U-100592 and U-100766, novel oxazolidinone antibacterial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1996;40:839–845. doi: 10.1128/aac.40.4.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]