Abstract

Objective

This study aims to evaluate the impact of a primary care nurse practitioner (NP)-led clinic model piloted in British Columbia (Canada) on patients’ health and care experience.

Design

The study relies on a quasi-experimental longitudinal design based on a pre-and-post survey of patients receiving care in NP-led clinics. The prerostering survey (T0) was focused on patients’ health status and care experiences preceding being rostered to the NP clinic. One year later, patients were asked to complete a similar survey (T1) focused on the care experiences with the NP clinic.

Setting

To solve recurring problems related to poor primary care accessibility, British Columbia opened four pilot NP-led clinics in 2020. Each clinic has the equivalent of approximately six full-time NPs, four other clinicians plus support staff. Clinics are located in four cities ranging from urban to suburban.

Participants

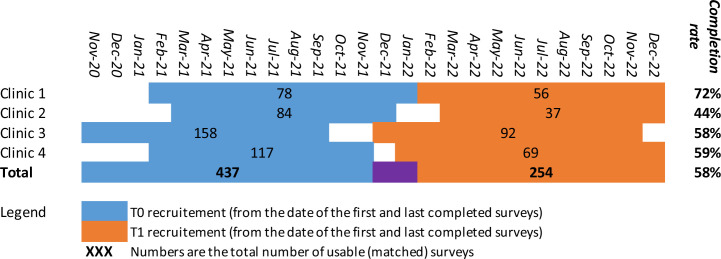

Recruitment was conducted by the clinic’s clerical staff or by their care provider. A total of 437 usable T0 surveys and 254 matched and usable T1 surveys were collected.

Primary outcome measures

The survey instrument was focused on five core dimensions of patients’ primary care experience (accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, responsiveness and outcomes of care) as well as on the SF-12 Short-form Health Survey.

Results

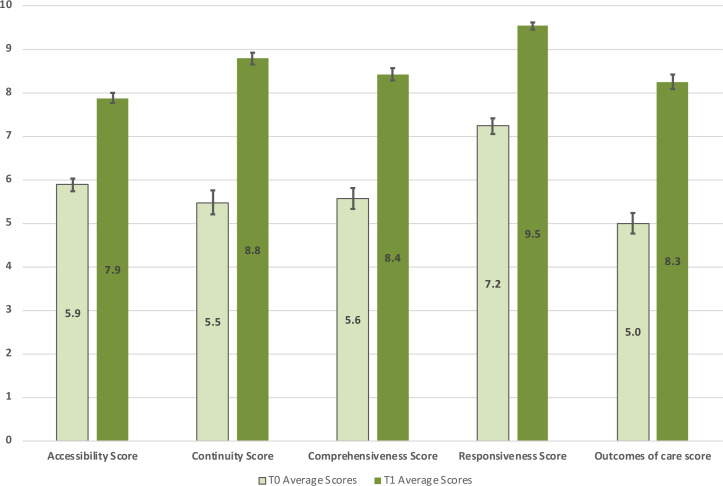

Scores for all dimensions of patients’ primary care experience increased significantly: accessibility (T0=5.9, T1=7.9, p<0.001), continuity (T0=5.5, T1=8.8, p<0.001), comprehensiveness (T0=5.6, T1=8.4, p<0.001), responsiveness (T0=7.2, T1=9.5, p<0.001), outcomes of care (T0=5.0, T1=8.3, p<0.001). SF-12 Physical health T-scores also rose significantly (T0=44.8, T1=47.6, p<0.001) but no changes we found in the mental health T scores (T0=45.8, T1=46.3 p=0.709).

Conclusions

Our results suggest that the NP-led primary care model studied here likely constitutes an effective approach to improve primary care accessibility and quality.

Keywords: GENERAL MEDICINE (see Internal Medicine), Health Services Accessibility, Health policy, Primary Health Care

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This study evaluates the impact of a primary care nurse practitioner-led clinic model piloted in British Columbia (Canada) on patients’ health and care experience.

The study rests on a pre-and-post survey without a control group therefore the differences observed could be caused by external factors.

Data collection took place between 2020 and 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Only four nurse-practitioner primary care clinics exist and participation in the survey was voluntary and uncompensated limiting the number of respondents.

Introduction

The lack of timely access to primary care services has been a significant problem across Canada for decades. Nearly one in seven Canadians had reported not having a regular healthcare provider in 20191 and, in 2020, 40% reported having an avoidable emergency department visit because of the lack of primary care options.2 Available indicators, such as the proportion of the Canadian population without a primary care provider, also suggest the situation has significantly worsened since the COVID-19 pandemic.3 4

Increased reliance on non-physicians such as registered nurses (RNs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) has long been documented as a way to improve primary care access.5–10 In Canada, NPs are RNs but with a broader scope of practice including the ability to autonomously diagnose, prescribe and monitor treatments, and refer patients to medical specialists, as well as having a specialised master-level or doctorate-level training.11

Several models have been used to integrate NPs into primary care delivery. The model with the highest disruption potential12 to the current primary care landscape is called the NP-led clinic.13 These clinics have NPs as the central professional on an interdisciplinary team providing the full scope of primary care services to a panel of patients.5 14 The NP-led clinic model has consistently been found to be effective and efficient in meeting the primary care needs of a general population.8–10 15–20

Despite the strength and abundance of evidence supporting the NP-led model, its implementation in Canada has been limited and patchy. In 2020, in response to the widespread need for primary care and the successful advocacy from its NP association,21 British Columbia (BC), 1 of Canada’s 10 provinces, opened 4 pilot NP-led clinics. The BC model was named NP primary care clinic (NP-PCC).

The aim of this study was to evaluate the impact of NP-PCCs on patient-reported health and experience of the first cohorts of rostered patients.

Methods

Background

The pilot NP-PCCs are located in four cities ranging from core urban to suburban. Three of the NP-PCC clinics are located on Vancouver Island and one on the BC mainland. All four clinics opened in 2020 (between June and October). From the onset, the clinics were tasked with providing comprehensive primary care services to the general population from formally defined catchment areas who were without a primary care provider. The rostering goal for all clinics was set at 6800 patients, or 1000 patients per NP, after 3 years of operation by the BC Ministry of Health (MoH). Patients are formally rostered to the clinic as well as informally attached to a specific NP within the clinic. The scope of practice of primary care NPs in BC is large and allows them to autonomously provide the full spectrum of primary care services to all ages from birth to death. Medical specialists are consulted when a patient’s healthcare needs to fall outside of the NP scope of practice. Due to very high demand, all four clinics used patient waitlists or random draws as a part of their attachment processes. The clinics are funded to have the equivalent of six full-time primary care NPs, one social worker, one mental health counsellor or clinician, two RNs, one clinic manager and four medical office assistants at the end of the 3 years implementation period. Clinics are funded by the BC MoH and have a self-appointed board of directors and managerial autonomy.22

Study design

The study relies on a quasi-experimental, longitudinal design based on a pre-and-post survey of patients receiving care in one of the four NP-PCCs. The prerostering survey (time 0 or T0) asked respondents to describe their care experience during the 2 years preceding being rostered to an NP-PCC as well as their current health. Approximately 1 year later, patients were asked to complete a second (time 1 or T1) similar survey, this time focused on their care experience as an NP-PCC patient. The design was adapted from previous work done by the same team.14 23 24

Patient and public involvement

The study is focused on patients’ health and care experience as reported by patients. The instruments used were developed in previous projects and no patient or public involvement took place this time. Results will be disseminated to patients through the clinics.

Participant recruitment

For the T0 recruitment, all patients newly rostered to one of the clinics were given an information sheet about the project by the clinic’s clerical staff or by their care provider. The information sheet included a link to a consent form and online survey instrument hosted on the University of Victoria Survey Monkey platform. The survey asked patients to provide their government-issued personal health number (PHN). The PHNs of patients who completed the T0 survey were shared with the clinics’ clerical staff who made a note in the clinics’ electronic health record system. About a year later during a subsequent visit to the clinic, those same patients were provided with an invitation to complete the T1 survey. Email invitations were also sent by the clinics to patients identified as having completed the T0 survey. Data collection periods varied slightly from site to site (see online supplemental appendix figure 1) but, overall, the T0 period ran from November 2020 to January 2022 and the T1 period ran from December 2021 to December 2022.

bmjopen-2023-072812supp001.pdf (214.5KB, pdf)

Instruments

The patient reported experience from being rostered in an NP-PCC were measured according to five core dimensions of primary care experience: accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, responsiveness and outcomes of care. Those dimensions have been extensively discussed and conceptualised in the literature.25–27 The definition of accessibility rests on Donabedian’s seminal work,28 as the fit between the structures of production, on one hand, and society’s needs and their geographic distribution, on the other. It is operationalised here as the patient’s perception that they can access healthcare services without undue constraints. Continuity is defined, based on the work of Haggerty et al,29 as the fact that a patient is treated by the same professional or the same team over time (relational continuity) and that different services are harmoniously integrated with each other (management continuity). Comprehensiveness encompasses two dimensions that make up the scope of patient management: considering all of a patient’s needs and providing a complete basket of services.14 30 Responsiveness is defined here as the convergence between the patients’ expectations regarding non-technical elements of the care and what the clinic offers in practice.27 Finally, what is described as outcomes of care relates to the patients’ perception that the care received had a positive impact on their health.31

The five dimensions described above were measured using a survey instrument adapted from the one developed by Pineault et al31 32 which was in turn an expanded version of two well-validated pre-existing instruments: the Primary Care Assessment Survey33 and the Primary Care Assessment Tool.34 Details on the phrasing of the survey questions and computation of scores can be found elsewhere.24 32 Each score is measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 10. For each score, missing values were processed according to the rules established for that instrument.24 32 In addition to the patient-focused indicators described above, we also measured respondents’ general health status using the SF-12 Short-form Health Survey.35 The SF-12 instrument provides a physical health score and a mental health score, both measured on a scale ranging from 0 to 100 and calibrated at 50 for the average US adult population. The surveys relied on a branching logic (the questions a given respondent will see depend on their previous answers) but overall, the T0 survey included 89 questions and the T1 survey 59 questions.

Sample and procedures

At the end of the data collection period, patients’ PHNs were used to individually match T0 and T1 survey answers. Survey answers that could not be matched (missing or divergent PHN) were removed from the database. In the same way, missing data either at T0 or T1 for any given score led to the removal of those responses in the computation of mean scores and differences. Scores were computed in Microsoft Excel.

There were 437 usable T0 surveys and 254 matched and usable T1 surveys (see figure 1). The representativeness of the survey respondents as compared with the population of the clinics’ catchment areas as well as to the clinics’ rosters was analysed at the end of T0 data collection and results have been published elsewhere.36 For all sociodemographic variables tested, the clinics’ patients were similar to the population of the catchment areas except for an over-representation of children at the two clinics with an NP whose practice was focused on paediatric care. The comparison of the clinics’ patients with T0 respondents showed no major differences. At the end of the data collection period, we also used descriptive and inferential statistics on sociodemographic information to assess the risk of attrition bias. For categorical data, we used χ2 tests based on the actual T1 number of respondents per category and expected T1 numbers based on T0 proportions. Age was assessed both as a categorical variable based on 10-year age groups and by a t-test of the mean. Those tests were done in MS Excel.

Figure 1.

Recruitment periods, number of participants and completion rates per sites.

Primary outcomes were analysed using paired t-tests of the mean (T1–T0) on each of the five scores related to the core dimensions of patients’ primary care experiences as well as for the mental and physical health scores. Computations were done in IBM SPSS (V.26).

Results

The overall response rate of the T1 survey from T0 respondents was 58% (individual clinics rate varied from 44% to 72%). The χ2 tests conducted showed no significant indication of an attrition bias in the core sociodemographic variables captured by the survey (see online supplemental appendix table 1)

The main finding from the longitudinal analysis of patients’ experience of care is that there was a large increase in the scores for all dimensions measured (see figure 2). Patient perceptions of accessibility, continuity, comprehensiveness, responsiveness and that the care received made a difference on their health were significantly higher compared with the period preceding their rostering in the clinic. Probabilities from the paired t-test of the mean are below 0.001 for all five dimensions (see online supplemental appendix table 2).

Figure 2.

Patient experience of care scores (error bars=95% CI).

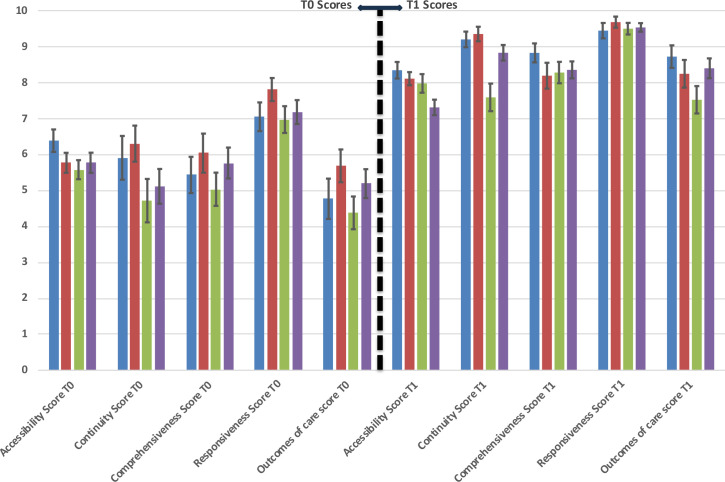

There was some intersite variability in prescores and postscores but the overall trend of significant improvements remains (see figure 3). All dimensions of patients’ primary care experiences vastly improved at all four sites. The pre–post differences for individual clinics are again significant (p<0.01) for all dimensions (see online supplemental appendix table 2).

Figure 3.

Patient experience of care scores per clinic (error bars=95% CI).

The composite experience of care scores also aligns with individual survey questions focused on similar constructs. For example, the proportion of respondents reporting unmet needs (based on the question, ‘In the last year, did you feel the need to see a doctor or another health professional for a health problem, but didn’t see one’) sharply decreased between T0 and T1. The overall proportion of patients reporting unmet needs at T0 was 60% (ranging from 45% to 67%). At T1 that proportion was down to 19% (ranging from 4% to 33%). As the question is not specific to primary care, challenges in access to specialist physicians or other services in each area should be considered in the interpretation of those scores.

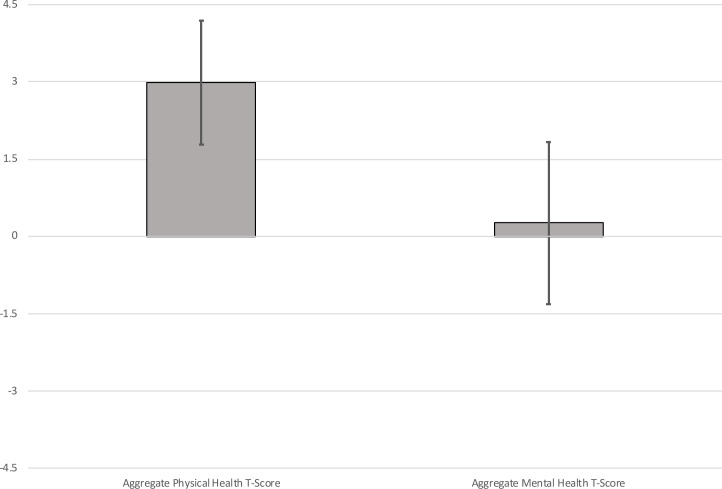

Regarding respondents’ health condition as measured by the SF-12 instruments, our results show an overall improvement in the physical health scores (rising from 44.8 at T0 to 47.6 at T1 p<0.001) and no change in the mental health score (from 45.8 at T0 to 46.3 at T1 p=0.709) (see figure 4 and online supplemental appendix table 3).

Figure 4.

Differences in SF-12 scores (T1–T0) error bars=95% CI. SF-12, Short-form Health Survey.

When analysed on a site-by-site basis, the trend of a significant improvement in the SF-12 physical health score persists. The data show a significant difference (at alpha 0.05) in pre-and-post physical health scores at three of the four clinics. Given the low number of responses (df ranging from 32 to 69), this trend is interesting.

When the matched T1–T0 differences in physical health scores are plotted in relation to the T1–T0 differences in mental health scores, it creates a scatter plot with four quadrants. The upper right quadrant contains respondents who reported both improved physical and mental health. The lower left quadrant contains respondents who reported both decreased physical and mental health. The two other quadrants correspond to people reporting improvements in one area and a decrease in the other. Overall, the figure shows that the improvement in the average physical health score is a product of both more people on the right on the graph (62% of respondents reported an improvement in their physical health) and the fact their average score difference is higher in absolute value (+7.6) as compared with respondents with a negative physical health score difference (−5.1). No such pattern exists for the mental health score differences (top vs bottom of figure 5)

Figure 5.

T1–T0 differences in SF-12 scores scatterplot. SF-12, Short-form Health Survey.

Discussion

The main finding from the longitudinal analysis of patients’ reported health and experience of care is that there was a large increase in the scores for all dimensions measured after rostering in an NP-PCC. The improvements observed in patients’ reported health and experiences regarding primary care can be in part explained by the low prerostering (T0) baseline. Other studies that relied on the same instruments24 31 measured higher baseline or control-arm scores. However, the postrostering scores (T1) measured here are similar to what was found for well-established medical clinics in those studies. Both the magnitude of the improvements measured here and the comparison of scores from the NP-PCC model as compared with the ones of large well-established interdisciplinary clinics found in other studies24 suggest that NP-PCCs are an effective model of primary care delivery.

Given the short duration of the longitudinal follow-up conducted here, we were surprised to observe a significant improvement in the physical health as measured by the SF-12 instrument. Informal discussions with NPs working at one of the clinics suggest that the NP-PCCs rostered a large proportion of patients who had been left with unmet need for long periods of time. Our hypothesis is that providing accessible and comprehensive care to those patients might have been enough to cause the observed improvements in physical health. It could also be that, given recovery from mental health condition is usually longer, our study period was too short to catch improvements at that level.

More generally, it might be stressed that the NP-PCC model was, from the onset, based on the assumption those clinics would focus on rostering patients who do not have a regular provider. The survey data confirm most patients did fit that profile and that they faced low accessibility to care as well as generally low quality of care before joining the NP-PCC.36 The proportion of survey respondents reporting unmet needs at T0 (60%) is many times higher than what is observed in other populations. In 2022, 7.7% of people in BC and 7.2% in Canada declared they did not get care when they had needs37 while the European Union average for medical care was at 4.8%.38

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, it rests on a quasi-experimental design based on a pre-and-post survey without a control group. As such there is a risk that external factors explain the differences observed here. The most notable external factor is that the data collection took place between 2020 and 2022, during the COVID-19 pandemic. To control for some biases, the prerostering survey questions were edited to ask respondents about the care they received during the ‘last 2 years’ therefore including one prepandemic year. This phrasing is likely to have overinflated T0 scores as compared with what they would have been if those patients had to seek care outside of the NP-PCCs at that time. It might also be worth mentioning that all available indicators suggest that the primary care delivery capacity in BC sharply declined throughout the data collection period.39 Both the phrasing of the T0 survey and the context during data collection are likely to have had a negative impact on T1–T0 score differences making the magnitude of the differences observed here even more interesting.

Second, privacy and confidentiality considerations prevented the matching of T0 respondents with clinic’s patient rosters and made it impossible to compute a response rate for the ‘pre’ component of the survey. A descriptive and comparative analysis of T0 respondents published elsewhere36 suggest they were generally representative of the total clinic roster population. However, a sampling bias cannot be excluded given the methods used here. The survey instrument was only available in English which could cause a bias. However, the proportion of respondents who declared speaking another language at home or being born abroad was similar to the general population of the catchment area. We want to mention that the limited number of respondents is explained mostly by the fact only four NP-PCC clinics exist and that participation in the survey was voluntary and uncompensated.

Conclusion

Our findings show that offering people who were relying on low continuity, low comprehensiveness services, such as medical walk-in clinics, access to an NP-led alternative dramatically improves their care experience. All five dimensions of care measured are positively affected, and our results suggest that being followed in an NP-PCC could lead to gains in patients’ overall physical health. The patients’ primary care experience scores measured in our study favourably compare to the ones measured in well-established interdisciplinary and medical clinics.24

The international literature on NPs autonomously working as main providers of primary care suggests that it is a viable model.10 As such, our findings are well aligned with the large body of evidence showing that NP-led primary care is equivalent or better than average available medical care.8 10 15 40 By showing interesting outcomes of the NP-PCC model in BC, this study also suggests that NP-led models work in many different jurisdictions and contexts.

At a more local level, the results analysed here also suggest that BC’s NP-PCC model does produce the results that were hoped for when the model was launched22 and constitutes an effective approach to improve primary care accessibility and quality. More research on the efficiency of such models could play a role in future policy decisions to scale them up.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank Breanna Horne (UVic), Ashleigh Swanson (UVic), Shawna Glassel (NNPBC), Harjot Grewal (NNPBC), Lynn Guengerich (Health Care on Yates), Kari Jonker (Nexus), Lexi Grisdale (Axis) and Liz Gilmour (Flowerstone) for their support in this project.

Footnotes

Twitter: @faussenurse

Contributors: DC, KB and AD designed the study. DC, KB and GKR were involved in data collection. DC ran the computations and analyses and wrote the first draft. DC KB, AD and GR were involved in writing the final manuscript. DC is responsible for the overall content as the guarantor.

Funding: This work was supported, in part, by the non-profit Nurses and Nurse Practitioners of British Columbia (NNPBC) association. No grant number to report.

Competing interests: The authors report no competing interests. KB is a locum NP in one of the clinics in which the study took place.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

No data are available. The nature of the data and conditions set by the University of Victoria Human Research Ethics Board prevent the sharing of the raw data.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Consent obtained directly from patient(s).

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and the study was approved by the University of Victoria Human Research Ethics Board (#20-0324). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.Statistics Canada . Primary health care providers, 2019. Ottawa: Minister of Industry, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.CIHI . Commonwealth fund survey, 2020 [Internet]. 2020. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/en/commonwealth-fund-survey-2020

- 3.Azpiri J. Nearly 60% of British Columbians find it difficult to access a doctor or have no access at all: poll. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duong D, Vogel L. National survey highlights worsening primary care access. CMAJ 2023;195:E592–3. 10.1503/cmaj.1096049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Contandriopoulos D, Brousselle A, Breton M, et al. Nurse practitioners, Canaries in the mine of primary care reform. Health Policy 2016;120:682–9. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heale R, Butcher M. Canada’s first nurse practitioner-led clinic: a case study in Healthcare innovation. Cjnl 2010;23:21–9. 10.12927/cjnl.2010.21939 Available: http://www.longwoods.com/publications/nursingleadership/21928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lovink MH, Persoon A, Koopmans RTCM, et al. Effects of substituting nurse practitioners, physician assistants or nurses for physicians concerning Healthcare for the aging population: A systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs 2017;73:2084–102. 10.1111/jan.13299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin-Misener R, Harbman P, Donald F, et al. Cost-effectiveness of nurse practitioners in primary and specialised ambulatory care: systematic review. BMJ Open 2015;5:e007167. 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poghosyan L, Liu J, Norful AA. Nurse practitioners as primary care providers with their own patient panels and organizational structures: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;74:1–7. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Laurant M, van der Biezen M, Wijers N, et al. Nurses as substitutes for doctors in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2018;7:CD001271. 10.1002/14651858.CD001271.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Nurses Association . Nurse Practitioners. Ottawa, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christensen CM, Grossman JH, Hwang J. The Innovator’s prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care. New-York: Mc Graw Hill, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Christensen C, Grossman J, Hwang J. The Innovator’s Prescription: A Disruptive Solution for Health Care. New-York: McGraw Hill, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Contandriopoulos D, Perroux M, Cockenpot A, et al. Analytical typology of Multiprofessionnal primary care models. BMC Fam Pract 2018;19:44.:44. 10.1186/s12875-018-0731-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greene J. Nurse practitioners provide quality primary care at a lower cost than physicians. Manag Care 2018;27:34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu C-F, Hebert PL, Douglas JH, et al. Outcomes of primary care delivery by nurse practitioners: utilization, cost, and quality of care. Health Serv Res 2020;55:178–89. 10.1111/1475-6773.13246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Randall S, Crawford T, Currie J, et al. Impact of community based nurse-led clinics on patient outcomes, patient satisfaction, patient access and cost effectiveness: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;73:24–33. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dierick-van Daele ATM, Steuten LMG, Metsemakers JFM, et al. Economic evaluation of nurse practitioners versus Gps in treating common conditions. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e28–35. 10.3399/bjgp10X482077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vincent D. Using cost-analysis techniques to measure the value of nurse practitioner care. Int Nurs Rev 2002;49:243–9. 10.1046/j.1466-7657.2002.00140.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poghosyan L, Norful AA, Liu J, et al. Nurse practitioner practice environments in primary care and quality of care for chronic diseases. Med Care 2018;56:791–7. 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prodan-Bhalla N, Scott L. Primary Care Transformation in British Columbia: A New Model to Integrate Nurse Practitioners. Vancouver: British Columbia Nurse Practitionner Association, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 22.British Columbia Ministry of Health . New nurse practitioner primary care clinic opening soon in Victoria. 2020. Available: https://news.gov.bc.ca/releases/2020HLTH0296-001789

- 23.Contandriopoulos D, Duhoux A, Roy B, et al. Integrated primary care teams (IPCT) pilot project in Quebec: a protocol paper. BMJ Open 2015;5:e010559. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duhoux A, Dufour É, Sasseville M, et al. Rethinking primary care delivery models: can integrated primary care teams improve care experience Int J Integr Care 2022;22:8.:8. 10.5334/ijic.5945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haggerty JL, Burge F, Beaulieu M-D, et al. Validation of instruments to evaluate primary Healthcare from the patient perspective: overview of the method. Healthc Policy 2011;7(Spec Issue):31–46. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Levesque J-F, Descôteaux S, Demers N, et al. Measuring Organizational Attributes of Primary Healthcare: A Scanning Study of Measurement Items Used in International Questionnaires Montréal: Unité Évaluation de l’organisation des soins et services, Direction de l’analyse et de l’Évaluation des systèmes de soins et services. INSPQ, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pineault R, Levesque J-F, Roberge D, et al. L'Accessibilité et La Continuité des services de Santé: une Étude sur La Première Ligne au Québec: rapport de Recherche. Longueuil: Centre de Recherche de l’Hôpital Charles LeMoyne, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988;260:1743–8. 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Haggerty J, Burge F, Pineault R, et al. Managementcontinuity from the patient perspective: comparison of primary Healthcare evaluation instruments.Healthcare policy. Hcpol 2011;7(SP):139–53. 10.12927/hcpol.2011.22709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Haggerty J, Beaulieu M-D, Pineault R, et al. Comprehensiveness of care from the patient perspective: comparison of primary Healthcare evaluation instruments. Hcpol 2011;7:154–66. 10.12927/hcpol.2011.22708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pineault R, Borgès Da Silva R, Provost S, et al. Impacts of Québec primary Healthcare reforms on patients’ experience of care, unmet needs, and use of services. Int J Family Med 2016;2016:8938420. 10.1155/2016/8938420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haidar OM, Lamarche PA, Levesque J-F, et al. The influence of individuals’ Vulnerabilities and their interactions on the assessment of a primary care experience. Int J Health Serv 2018;48:798–819. 10.1177/0020731418768186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The primary care assessment survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care 1998;36:728–39. 10.1097/00005650-199805000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shi L, Starfield B, Xu J. Validating the adult primary care assessment tool. J Fam Pract 2001;50:161–71. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JEJ, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of Reliability and validity. Med Care 1996;34:220–33. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Contandriopoulos D, Bertoni K, Horne B, et al. A descriptive analysis of the previous care experiences of patients being Rostered in BC’s new nurse-practitioner primary care clinics. Nurse Practitioner Open Journal 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Statistics Canada . Table 13-10-0836-01 unmet health care needs by sex and age group. 2022. Available: https://www150-statcan-gc-ca.ezproxy.library.uvic.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310083601

- 38.Eurostat . Unmet health care needs Statistics (2022): Eurostat. 2022. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Unmet_health_care_needs_statistics#Unmet_needs_for_health_care

- 39.Xu X. Nearly 900,000 British Columbians don’t have a family doctor, leaving walk-in clinics and ERS swamped. The Globe and Mail 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mundinger MO, Kane RL, Lenz ER, et al. Primary care outcomes in patients treated by nurse practitioners or physicians: A randomized trial. JAMA 2000;283:59–68. 10.1001/jama.283.1.59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2023-072812supp001.pdf (214.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

No data are available. The nature of the data and conditions set by the University of Victoria Human Research Ethics Board prevent the sharing of the raw data.