Abstract

Objective:

Engagement in mental health treatment is low, which can lead to poor outcomes. We evaluated the efficacy of offering patients financial incentives to increase their mental health treatment engagement, also referred to as contingency management.

Method:

We meta-analyzed studies offering financial incentives for mental health treatment engagement, including increasing treatment attendance, medication adherence, and treatment goal completion. Analyses were run within a multilevel framework. All study designs were included, and sensitivity analyses were run including only randomized and high-quality studies.

Results:

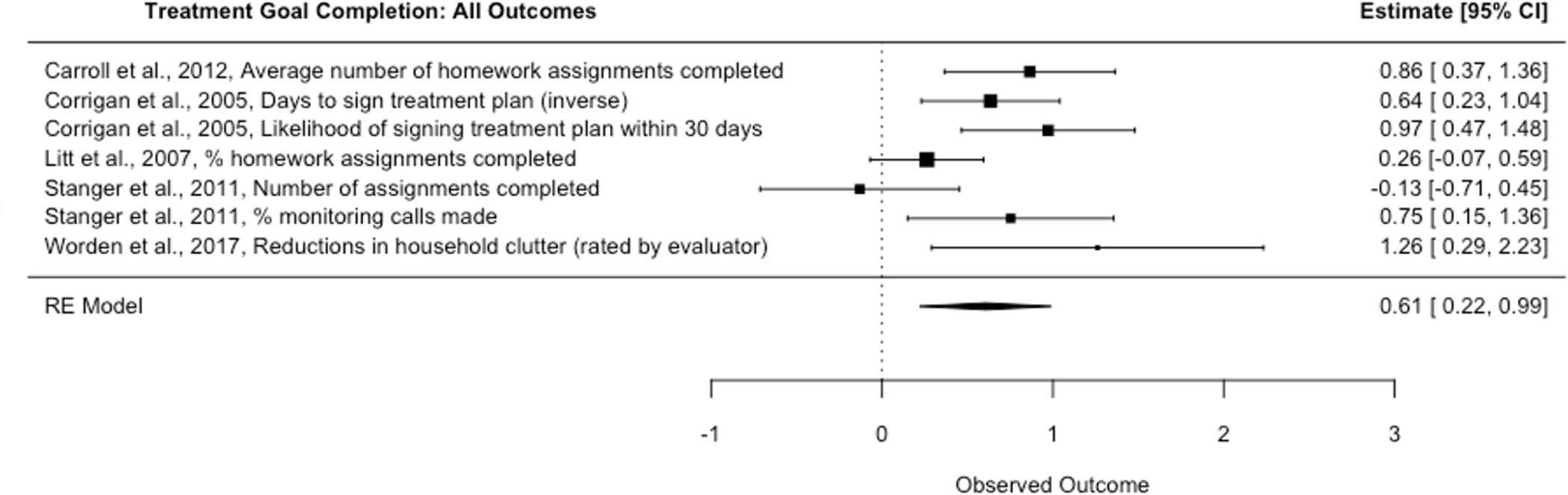

About 80% of interventions incentivized treatment for substance use disorders. Financial incentives significantly increased treatment attendance (Hedges’ g = 0.49, [0.33, 0.64], k = 30, I2 = 83.14), medication adherence (Hedges’ g = 0.95, [0.47, 1.44], k = 6, I2 = 87.73) and treatment goal completion (Hedges’ g = 0.61, [0.22, 0.99], k = 5, I2 = 60.55), including completing homework, signing treatment plans, and reducing problematic behavior.

Conclusions:

Financial incentives increase treatment engagement with medium to large effect sizes. We provide strong evidence for their effectiveness in increasing substance use treatment engagement and preliminary evidence for their effectiveness in increasing treatment engagement for other mental health disorders. Future research should prioritize testing the efficacy of incentivizing treatment engagement for mental health disorders aside from substance use. Research must also identify ways to incentivize treatment engagement that improve functioning and long-term outcomes and address ethical and systemic barriers to implementing these interventions.

Keywords: Financial incentives, contingency management, treatment engagement, treatment attendance, medication adherence

A major challenge in the field of mental health is providing access to evidence-based treatments. Along with systemic barriers to delivering these interventions in community settings, another substantial barrier to improving outcomes is low levels of treatment engagement. Studies have shown that individuals pursuing mental health treatment often do not attend their initial appointments (Fenger et al., 2011), discontinue psychotherapy and medication treatment early (McIvor et al., 2004; Sajatovic et al., 2010), and do not complete homework or other treatment goals (Kazantzis et al., 2005). Overall, only about a third of patients with mental health disorders receive enough treatment for it to be considered minimally adequate (Wang et al., 2005). Low engagement is a particular problem for individuals pursuing mental health treatment versus other types of healthcare (Mitchell & Selmes, 2007). Furthermore, treatments like psychotherapy and psychotropic medications can take weeks or months to provide relief from symptoms, making it challenging for patients to continue to pursue treatment that is not immediately effective.

One method of enhancing individuals’ willingness to engage in treatment (i.e., attend treatment, take medications, or meet treatment goals) involves offering financial incentives for doing so, an approach also referred to as contingency management. Financial incentives provide individuals with short-term rewards to help enhance their motivation to pursue their long-term treatment goals, such as improving symptoms of a disorder by attending therapy, taking medication, or completing homework or other tasks (Vlaev et al., 2019). These immediate rewards can help individuals align their actions more closely with their underlying preferences by helping them avoid the pull of other immediate rewards like saving money or time by not attending treatment (Marteau et al., 2009). Key to the success of these interventions is the identification of a target behavior that can be operationalized and monitored objectively to determine whether incentives should be provided.

Studies have demonstrated that financial incentives increase engagement in a range of treatment programs, including those related to smoking cessation, attendance at vaccination and screening appointments, and weight loss (Ananthapavan et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2014; Sigmon & Patrick, 2012). Research on offering incentives in the context of mental health treatment has focused mostly on targeting abstinence from substances. Several meta-analyses have demonstrated that providing financial incentives for abstinence, which include both cash vouchers and the chance to win prizes, is one of the most effective methods of reducing substance use (Benishek et al., 2014; Lussier et al., 2006).

While individual studies have shown that financial incentives can improve aspects of mental health treatment engagement like attending appointments, taking psychotropic medications, and completing treatment goals, effect sizes vary and null findings are not uncommon (Barton et al., 2020; Sinha et al., 2003). Previous meta-analyses (Table S1) have also found that financial incentives can increase treatment attendance and medication adherence, but these analyses either focused on treatment engagement for physical health conditions or were limited in their conclusions regarding mental health treatment engagement (Bolivar et al., 2021; Dutra et al., 2008; Lussier et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2012; Pfund et al., 2021). These limitations stemmed from aggregating effect sizes across multiple types of interventions instead of focusing on financial incentives (Dutra et al., 2008), not differentiating among individuals receiving treatment for physical versus mental health conditions (Petry et al., 2012), or including only individuals receiving medication treatment for opioid use disorder (Bolivar et al., 2021). Several meta-analyses also included studies in which multiple behaviors were incentivized together (e.g., treatment attendance and abstinence from substances) making it difficult to determine the effectiveness of targeting treatment engagement specifically versus other outcomes (Bolivar et al., 2021; Lussier et al., 2006; Petry et al., 2012; Pfund et al., 2021). As a result, the present meta-analysis is the first to evaluate the efficacy of providing financial incentives specifically for mental health treatment engagement. Moreover, no previous meta-analysis has examined the impact of financial incentives on the completion of treatment goals. Given the novelty of the present analysis, there is minimal overlap between studies included in previous meta-analyses and those included here (Table S1).

One explanation for differences in outcomes across studies relates to differences in each study’s intervention, sample, design, setting, or quality. Previous reviews have identified characteristics of interventions offering financial incentives that increase treatment efficacy, including longer interventions, more incentivized sessions, higher incentives, more immediate reward delivery, non-randomized designs, and higher quality studies (Davis et al., 2016; Ginley et al., 2021; Griffith et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006; Petry, Rash et al., 2012; Pfund et al., 2021). Pfund and colleagues (2021) examined moderators of studies targeting attendance for substance use disorders (k = 10) and found that studies with greater frequencies of incentivized sessions had higher effect sizes. Lussier and colleagues (2006) examined moderators of studies targeting either attendance or medication adherence for substance use disorders (k = 10) and found evidence of higher effect sizes for higher quality studies. We examined moderators of studies incentivizing mental health treatment attendance to help guide future research and implementation efforts by identifying study characteristics associated with increased efficacy.

In the present study, we evaluated the efficacy of using financial incentives to increase mental health treatment engagement, including treatment attendance, medication adherence, and treatment goal completion. We hypothesized that financial incentives would increase treatment attendance and medication adherence. Evaluating the impact of financial incentives on the completion of treatment goals was an exploratory aim, as we were unsure how studies operationalized this outcome. We also tested whether characteristics related to the intervention, sample, treatment setting, and study design moderated outcomes. As moderation analyses included a relatively small number of studies, we also considered this aim exploratory. Based on previous findings, we hypothesized that longer interventions, more incentivized sessions, higher incentives, more immediate reward delivery, non-randomized designs, and higher quality studies would be associated with greater treatment efficacy. Our last, exploratory aim was to assess the impact of offering financial incentives for treatment engagement on mental health symptoms, functioning, and quality of life.

Method

We evaluated the impact of financial incentives on each type of outcome (i.e., attendance, medication adherence, and treatment goal completion) separately and did not combine them. Moderators were only examined for attendance outcomes as too few studies assessed medication adherence and treatment goal completion. We defined mental health treatment as treatment for any disorder included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV or DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As we were interested in mental health treatment engagement overall, we included individuals with mental health disorders of any age and background. Included interventions offered financial rewards for mental health treatment engagement compared to a control group not receiving rewards contingent on behavior. All study designs were included, but analyses were rerun including only randomized and only high-quality studies. Main outcomes included the target behavior measured objectively or verified using objective measures. For treatment goal completion, we included studies that targeted activities consistent with meeting treatment goals, including completing homework or other assignments, showing reductions in problematic behavior, or committing to treatment plans. Secondary outcomes included assessments of mental health symptoms, functioning, or quality of life.

Literature Search

We searched PubMed and PsycInfo databases using terms related to financial incentives, treatment engagement, and mental health disorders from inception through October 2020 (the original search was conducted in October 2019 and updated in October 2020). The following search terms were used: (Abstract/Title: incentiv* OR cash OR money OR token* OR payment* OR voucher* OR contingency management OR prize*) AND (Abstract/Title: complian* OR adhere* OR attend* OR medication* OR therap* OR appointment*) AND (All text: psychiatr* OR mental health OR mental illness OR substance). A sample search string is included in the supplemental materials (Object S1). Articles were restricted to English. We also identified relevant meta-analyses and reviews using the same search terms along with Abstract/Title: review* OR meta analysis OR meta-analysis OR meta analyses OR meta-analyses. We hand-searched relevant meta-analyses and reviews for articles missed by searching databases.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Participants

No restrictions were made based on age or type of mental health disorder. To include studies conducted in community settings, we included studies in which participants were being treated for a disorder (e.g., cocaine use disorder) even if an official diagnosis was not confirmed.

Interventions

We included interventions that aimed to increase engagement in mental health treatment using financial rewards, defined as rewards with monetary value. Studies in which financial rewards were provided along with non-financial rewards (e.g., public praise) were included. Engaging in treatment included increasing attendance, medication adherence, or treatment goal completion. Studies only offering research-related payments were excluded. Studies were also excluded if they only provided incentives in the form of methadone take-home doses, access to paid work or work training, or vouchers to cover treatment expenses (e.g., transportation to the clinic), as these are not typically considered financial rewards. Studies could target treatment engagement along with another outcome (e.g., abstinence) as long as it was possible to isolate the effects of targeting engagement. For example, a study including a control (no-incentive) group, a group provided incentives for attendance, and a group provided incentives for abstinence would be included, but we would only include groups relevant to our analysis (i.e., the control group and group provided incentives for attendance).

Study Designs

All study designs, including between-subjects and within-subjects designs, were included. We aimed to be as inclusive as possible, as many studies testing financial rewards use within-subjects or historical control group designs, particularly those conducted in clinic or community settings. To ensure that our results were not biased by the inclusion of non-randomized studies, we recalculated effect sizes using only studies with between-subjects, randomized designs. As few studies included long-term follow-ups, we only examined end-of-treatment outcomes. We also excluded studies in which participants were treatment providers, family members, or support persons and not patients. Finally, we excluded studies in which multiple people (e.g., multiple family members) or behaviors (e.g., attending treatment and receiving vaccines) were incentivized together and not in separate treatment groups, as this did not allow us to isolate the effects of targeting treatment engagement.

Control Groups

Control groups could not administer a different type of contingent reward (e.g., rewards for abstinence). However, studies in which both groups received contingent rewards (e.g., methadone take-home doses) but the intervention group also received rewards for treatment engagement were included as long as we could isolate the effect of targeting engagement (i.e., one group provided incentives for engagement and another did not). Two studies included groups given alternative treatments (i.e., reduction of logistic barriers and motivational interviewing) in addition to control groups (Corrigan & Bogner, 2005; Corrigan et al., 2007). One study (Marcus et al., 2020) included a de-escalating financial incentives group in addition to a control group (Table S2). For these studies we included the control groups, but not the groups given alternative treatments as these were neither control groups nor intervention groups. We excluded the de-escalating financial incentives group as this incentive structure differed from all other studies providing fixed or escalating incentives, and also did not qualify as a control group.

Outcomes

Main outcomes included objective measures of the target behavior, including self-reports supported by objective measures. For attendance studies, outcomes included attendance verified by clinicians, researchers, or supervised sign-in sheets. For medication adherence studies, outcomes included supervised ingestion or injection of medications, as well as adherence measured with smart pill bottles. For treatment goal completion studies, outcomes included clinician ratings of homework completion, signing of treatment plans, and reductions in problematic behaviors (i.e., hoarding levels measured by a blind evaluator), based on the activities targeted by studies that were consistent with meeting treatment goals.

Secondary outcomes were measures of mental health symptoms, functioning, or quality of life, which we refer to as symptom and functional outcomes. We did not conduct an independent search for papers with these outcomes and included them only if they were presented in otherwise eligible papers. We included two types of outcomes and analyzed them separately so that analyses included measures comparable to one another. The first were validated self- or clinician-rated measures of mental health symptoms, functioning, or quality of life, excluding those developed for the specific study or clinic without evidence of reliability or validity from the study itself or previous studies. The second were objective measures of substance use derived from toxicology screens; included studies all used urine toxicology screens. We analyzed toxicology screen data only for attendance studies as this information was included in only two medication adherence and treatment goal completion studies, respectively, and we did not run analyses with fewer than four studies. We excluded measures consisting only of patient estimates of instances of substance use, as these measures varied widely across studies and evidence of reliability or validity was typically not presented.

Selection and Coding of Studies

Two authors reviewed the first 350 titles and abstracts to achieve reliability (κ = .83, 95% CIs [.70, .96] and then one of these authors reviewed the remaining titles and abstracts. Full texts were reviewed by both authors, and conflicts were resolved via consensus. Articles describing relevant parent studies, protocols, or feasibility analyses were included and the main outcome paper was identified or the authors were contacted to help identify it. Articles presenting information from the same study were linked together and all information, including graphs, were used for coding. For articles that did not include enough information to calculate effect sizes for main or secondary outcomes, we contacted the authors to request this information. Eight studies were excluded as they did not include enough information to calculate effect sizes (Table S3). We requested data from 14 authors and 6 provided data (43% response rate).

Article Characteristics and Study Quality

Two authors developed a coding manual and coded a subset of studies (k = 23) to achieve reliability. Reliability was calculated using Krippendorff’s alpha (Hayes & Krippendorff, 2007), an interrater reliability coefficient that accommodates categorical and continuous outcomes, as well as missing data (Hallgren, 2012). Krippendorff’s alpha ranged from .84 [95% CI = .56, 1.0] to 1.0 [95% CI = .10, 1.0] and averaged .96. Subsequently, one of these authors coded the study and discussed challenging decisions with the other author. We coded characteristics related to studies’ intervention, sample, design, and setting (see Table 1 for a full list and description).

Table 1.

Description of Study Characteristics Coded and Included in Moderation Analyses

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Basic information: | |

| Author; Description; Publication year* | Publication year of the main outcome paper |

|

| |

| Sample characteristics | |

|

| |

| Sample size | Total sample size included in the intervention and control groups |

| Mean age* | For all participants |

| Sex* | Proportion female vs. male for all participants |

| Race and ethnicity* | Proportion minority vs. White for all participants |

| Type of psychiatric disorder* | Substance use disorder vs. not (emotional disorder, psychotic disorder, or other). If participants with two disorders were included, the study was categorized based on the disorder targeted in the intervention. |

| Meets criteria for psychiatric disorder* | Whether the sample met full criteria for a psychiatric disorder (DSM or ICD) or was assumed to have a disorder based on participation in a treatment program |

|

| |

| Intervention characteristics | |

|

| |

| Randomized vs. non-randomized design* | Randomized included randomized controlled trials (including cluster randomization) and controlled clinical trials |

| Between- vs. within-subjects design* | Between vs. within-subjects design overall, as well as between-subjects designs with concurrent control groups vs. between-subjects design with historical control groups vs. within-subjects designs |

| Type of control group* | Active (the only difference between groups was the financial incentive; includes historical controls) vs. non-active (the treatment group received an intervention that the control group did not receive in addition to the financial incentive, like case management) |

| Control group received contingent rewards* | Studies in which both groups received contingent rewards (e.g., methadone take-home doses), but the intervention group also received rewards for psychiatric treatment engagement vs. studies in which the control group did not receive any contingent rewards |

| Length of treatment, in weeks* | Number of weeks that the intervention involving financial incentives lasted, not including follow-up assessments |

| Number of incentivized sessions* | Number of sessions or assessments that included the opportunity to receive an incentive |

| Community study vs. not*a | Studies in clinics or community settings vs. studies for which research participants were recruited |

|

| |

| Incentive characteristics | |

|

| |

| Type of incentive* | Vouchers incentives (distributed every time the target behavior was achieved) vs. lottery-style incentives (participants were given the chance to win incentives every time the target behavior was achieved) |

| Schedule of reinforcement*a | Fixed rewards (participants were given the same reward each time they completed the behavior) vs. escalating rewards (participants were given rewards of increasing value when they completed the behavior more than once) |

| Coupons vs. gift cards* | Money/store coupons vs. items/item-specific gift cards |

| Total value of money or prizes* | Total value of money or prizes that participants could win if they showed perfect adherence |

| Average value of money or prizes won* | Average value of money or prizes that participants actually received |

| Immediate vs. delayed reinforcement* | Incentives received on the same day as the target behavior was completed vs. not always on the same day |

|

| |

| Study quality | |

|

| |

| Overall study quality* | Overall risk of bias based on the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies |

| Information received from authors* | Studies for which authors provided data vs. all other studies |

Note. Two characteristics included in the protocol were not coded or analyzed as moderators. Rate of attrition was not possible to code for studies that incentivized attendance, as reducing attrition was the focus of the intervention and attrition rates differed substantially by group. It was also not possible to analyze studies that were published vs. non-published dissertations as we only included one non-published dissertation.

Moderator was not specified in the protocol and emerged as a potentially important characteristic during the coding of studies

Included in moderation analyses

Two authors coded study quality for all studies using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies and resolved conflicts via consensus. We chose this tool because it can be used across randomized and non-randomized studies (Thomas et al., 2004). The Quality Assessment Tool includes ratings of selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals/dropouts, and gives higher ratings to studies with randomized designs (see Table S7). This widely used tool’s reliability, as well as its content and construct validity, have been established (Armijo-Olivo et al., 2012; Jackson & Waters, 2005). To ensure that results were not biased by the inclusion of studies of varying quality, we recalculated effect sizes using only studies rated as high quality (Thomas et al., 2004).

Effect Sizes

Two authors coded all effect sizes. For main outcomes, all non-overlapping effect sizes directly related to the target behavior were included in analyses using a multilevel framework. When effect sizes overlapped (e.g., number of counseling sessions attended and total number of sessions attended), we chose the most comprehensive effect size (e.g., total number of sessions attended). When necessary, we pooled effect sizes to arrive at a comprehensive effect size (e.g., pooling results for months 1, 2, and 3; Table S2). We also ran analyses including only outcome measures consistent across studies (referred to as primary outcome measures), excluding studies that did not provide these measures (Table S2, “Effect Size Designation”). For attendance studies, primary outcome measures included number of sessions/days attended or attendance rates. For medication studies, primary measures included number of doses taken or medication adherence rates. We did not run this analysis for treatment goal completion studies, as we would have only been able to include three studies.

We excluded studies that only provided non-parametric effect size data (i.e., median and interquartile ranges; Businelle et al., 2009; Ramo et al., 2015; Ramo et al., 2018), as when data are presented as such it suggests that distributions are skewed and that effect sizes cannot be analyzed parametrically (Higgins, Li & Deeks, 2020). We contacted these authors but did not get additional information because the authors could not access the study data or did not respond.

Analyses

Converting Effect Sizes

We converted all effect sizes to Hedges’ g, which represents standardized mean differences and is a version of Cohen’s d corrected for small sample bias. According to recent recommendations (Lakens, 2013), we used formulas for Hedges’ gs for between-subjects designs and Hedges’ gav for within-subjects designs, which allows for the comparison of effect sizes across these designs. For between-subjects designs, we calculated Hedges’ gs using post-test means and SDs (or SEs) from the treatment and control groups for continuous outcomes. We converted binary outcomes (provided as proportions), t-values from between-samples t-tests, odds ratios, and Cohen’s d values provided in the text to Hedges’ gs (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). For studies with cluster randomized designs (Metrebian et al., 2021; Priebe et al., 2013), we adjusted Hedges’ gs using the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) provided in the text (Higgins, Eldridge, & Li, 2020). For within-subject designs, we calculated Hedges’ gav using pre-test and post-test means and SDs (or SEs) for continuous outcomes (Lakens, 2013; Goulet-Pelletier & Cousineau, 2018) and converted binary outcomes (provided as proportions) to Hedges’ gav (Borenstein et al., 2009). Effect sizes were converted when necessary such that positive values always represent effects that benefited the intervention group or period compared to the control group or baseline period (Tables S2, S4, and S5).

Main Analyses

For a summary of analyses, see Table 2. For each group of studies (attendance, medication adherence, and goal completion) we ran four sets of analyses: 1) Using all non-overlapping outcomes provided; 2) Using primary outcome measures common across all studies (one effect size per study; studies without primary outcome measures were excluded – see Effect Sizes); 3) Using only randomized studies; (4) Using only high-quality studies (Thomas et al., 2004). All analyses were run using random effect models with restricted maximum likelihood estimation. For analyses including multiple, dependent effect sizes we used 3-level models, with effect sizes nested within studies. For analyses with one effect size per study we used a typical 2-level meta-analytic framework in which participants are nested within studies (Harrer et al., 2019).

Table 2.

Summary of effect sizes

| Outcomes (number of studies) | Levels | Number of studies | Number of effect sizes | Hedges’ g | Standard Error | 95% CI | P | Q | Total I2 (%) | Level 2 I2 (%) | Level 3 I2 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Attendance | |||||||||||

| All outcomes (1) | 3 | 30 | 65 | 0.49* | 0.08 | 0.33, 0.64 | <.001 | 299.88, p <.001 | 83.14 | 18.64 | 64.50 |

| Primary outcomes (2) | 2 | 24 | 24 | 0.53* | 0.09 | 0.34, 0.72 | <.001 | 114.06, p <.001 | 80.83 | ||

| Primary, no outlier (3)a | 2 | 23 | 23 | 0.49* | 0.09 | 0.31, 0.67 | <.001 | 88.10, p < .001 | 77.18 | ||

| Only randomized studies (4) | 3 | 16 | 34 | 0.52* | 0.11 | 0.29, 0.74 | <.001 | 213.88, p < .001 | 86.36 | 29.37 | 56.99 |

| Only high-quality studies (5) | 3 | 21 | 48 | 0.51* | 0.09 | 0.33, 0.69 | <.001 | 257.03, p < .001 | 84.16 | 24.03 | 60.13 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Medication adherence | |||||||||||

| All outcomes (6) | 3 | 6 | 14 | 0.95* | 0.22 | 0.47, 1.44 | <.001 | 65.01, p < .001 | 87.73 | 16.87 | 70.56 |

| Primary outcomes (7) | 2 | 6 | 6 | 0.89* | 0.29 | 0.33, 1.45 | .002 | 43.56, p < .001 | 89.48 | ||

| Only high-quality studies (8) | 3 | 5 | 12 | 0.83* | 0.22 | 0.35, 1.31 | .003 | 52.64, p < .001 | 86.57 | 22.69 | 63.89 |

| Only randomized studies | All studies were randomized | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Treatment Goal Completion | |||||||||||

| All outcomes (9) | 3 | 5 | 7 | 0.61* | 0.16 | 0.22, 0.99 | .008 | 14.97, p = .021 | 60.55 | 60.55 | 0.00 |

| Primary outcomes | Not analyzed – only 3 studies | ||||||||||

| Only randomized studies | Not analyzed – only 3 studies | ||||||||||

| Only high-quality studies | Not analyzed – only 3 studies | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Symptom and functional outcomes | |||||||||||

| Attendance, survey (10) | 3 | 6 | 16 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.00, 0.20 | .060 | 6.93, p = .960 | 0.00 | ||

| Attendance, toxicology (11) | 3 | 6 | 10 | 0.23 | 0.10 | −0.01, 0.46 | .054 | 8.49, p = .486 | 36.15 | 0.00 | 36.15 |

| Medication adherence, survey (12) | 3 | 4 | 10 | 0.18 | 0.20 | −0.27, 0.63 | .393 | 23.26, p = .006 | 78.43 | 0.00 | 78.43 |

| Goal completion (13) | 3 | 4 | 14 | −0.02 | 0.08 | −0.19, 0.15 | .791 | 16.07, p = .245 | 23.52 | 23.52 | 0.00 |

Note. CI = confidence intervals. Q = Cochran’s Q test for heterogeneity. Total I2 = for 3-level models, the proportion of total variance attributed to within- and between-study variance. For 2-level models, the proportion of total variance attributed to between-study variance. Level 2 I2 = proportion of variance attributed to within-study variance (effect sizes within studies) for 3-level models; Level 3 I2 = proportion of variance attributed to between-study variance (effect sizes across studies) for 3-level models. All outcomes = models all non-overlapping outcomes provided in the studies; Primary outcomes = models used the one primary outcome measure common across all studies; Only randomized studies = models included only between-subjects designs in which participants were randomized to conditions. Survey = studies that assessed symptom or functional outcomes with self-reported or clinician-rated measures. Toxicology = studies that assessed substance use with urine toxicology screens. Toxicology screen analyses were not run for medication adherence or goal completion outcomes as there were too few studies (< 4) in these categories.

Kidorf et al., 2009 emerged as an outlier in model 2

p < .01

Three studies presenting attendance outcomes included two sub-studies describing different sites (Walker et al., 2010), phases (Prendergast et al., 2015), or participants (Sigmon & Stitzer, 2005). To evaluate the need to account for shared variance across these sub-studies, we ran 4-level models nesting effect sizes within sub-studies, and sub-studies within studies for models 1, 4, and 5 (Table 2). We then ran 3-level models excluding the nesting of sub-studies within studies (i.e., considering the effect sizes for each sub-study as different effect sizes of one overall study) and compared the 4-level and 3-level models with ANOVAs. For model 2, we used the same method to compare a 3-level model nesting sub-studies within studies and a 2-level model without this nesting. As all ANOVAs clearly indicated that the models with fewer levels fit the data best (all ps = 1.00), we present results of the models with fewer levels, in which effect sizes were nested within the overall study without accounting for shared variance among effect sizes related to a particular sub-study. As Models 2 and 3, which include primary effect sizes, could only accommodate one effect size per study, we randomly selected one sub-study for each of the three relevant studies (the same across models; Table S2). We did not pool effect sizes because the effect sizes differed across sub-studies and could not be combined.

Outliers

To identify outliers, we calculated Cooks’ distance and DFBETA values for each model. Cook’s distance is a measure of influential data points that calculates the impact of each effect size when deleted from the analysis (Cook, 1977). DFBETA is another measure of influential data points that calculates the difference in model coefficients when each study is included versus excluded in the model (Belsley et al., 1980). The only outlier was identified as such by both indices and we present effect sizes including and excluding this outlier (Table 2).

Measuring Heterogeneity

To measure heterogeneity among effect sizes, we used Cochrane’s Q test and the I2 statistic. A significant Q test indicates that effect sizes differ significantly across studies, although this test can be underpowered when the number of included studies is low (West, 2010). I2 quantifies the extent of heterogeneity across studies. When I2 is 0%, variability is due to chance. I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% suggest low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins & Thompson, 2002). For 2-level models, we provide one I2 value representing heterogeneity across studies (Table 2). For 3-level models, we provide two I2 values – level 2 I2 represents the proportion of variance attributed to within-study variance (effect sizes within studies) and level 3 I2 represents proportion of variance attributed to between-study variance (effect sizes across studies).

Moderators

Study characteristics included in moderator analyses were specified in the protocol and are described in Table 1. We only analyzed moderators for studies targeting attendance given the small number of studies targeting medication adherence and treatment goal completion. Moderators were tested using mixed effect models.

Publication Bias

Publication bias was assessed using a funnel plot and Egger’s test of funnel plot asymmetry (Egger, 1997). A funnel plot plots the standard error for each study against the study’s effect size. Evidence of potential publication bias would appear as an asymmetrical distribution of studies towards the bottom, righthand side of the plot indicating increased publication of studies with small samples and positive effects. Egger’s test formally assesses for funnel plot asymmetry by quantifying the relationship between effect size and sampling variance. As it is not recommended to use these methods with fewer than 10 studies (Page et al., 2020), we only examined publication bias in studies targeting attendance. We used primary attendance outcomes (Table 2, model 3) so that effect sizes would be similar across studies and because it is not possible to include multiple, dependent effect sizes in these analyses.

Transparency and Openness

We follow PRISMA and MARS reporting guidelines (Applebaum et al., 2018), report sample sizes for included studies, exclusion criteria, and study measures analyzed. Data is provided at https://osf.io/ar9mv/?view_only=b7f833436a224514950e2bf7b98b2ee5. Analyses were conducted in R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, 2020); we used the “esc” package to convert effect sizes and the “metafor” package for all other analyses. Our protocol was preregistered on PROSPERO (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=162751); it was submitted it on December 17th 2019, prior to screening records, and published in its original form on April 28, 2020.

Results

Description of Studies

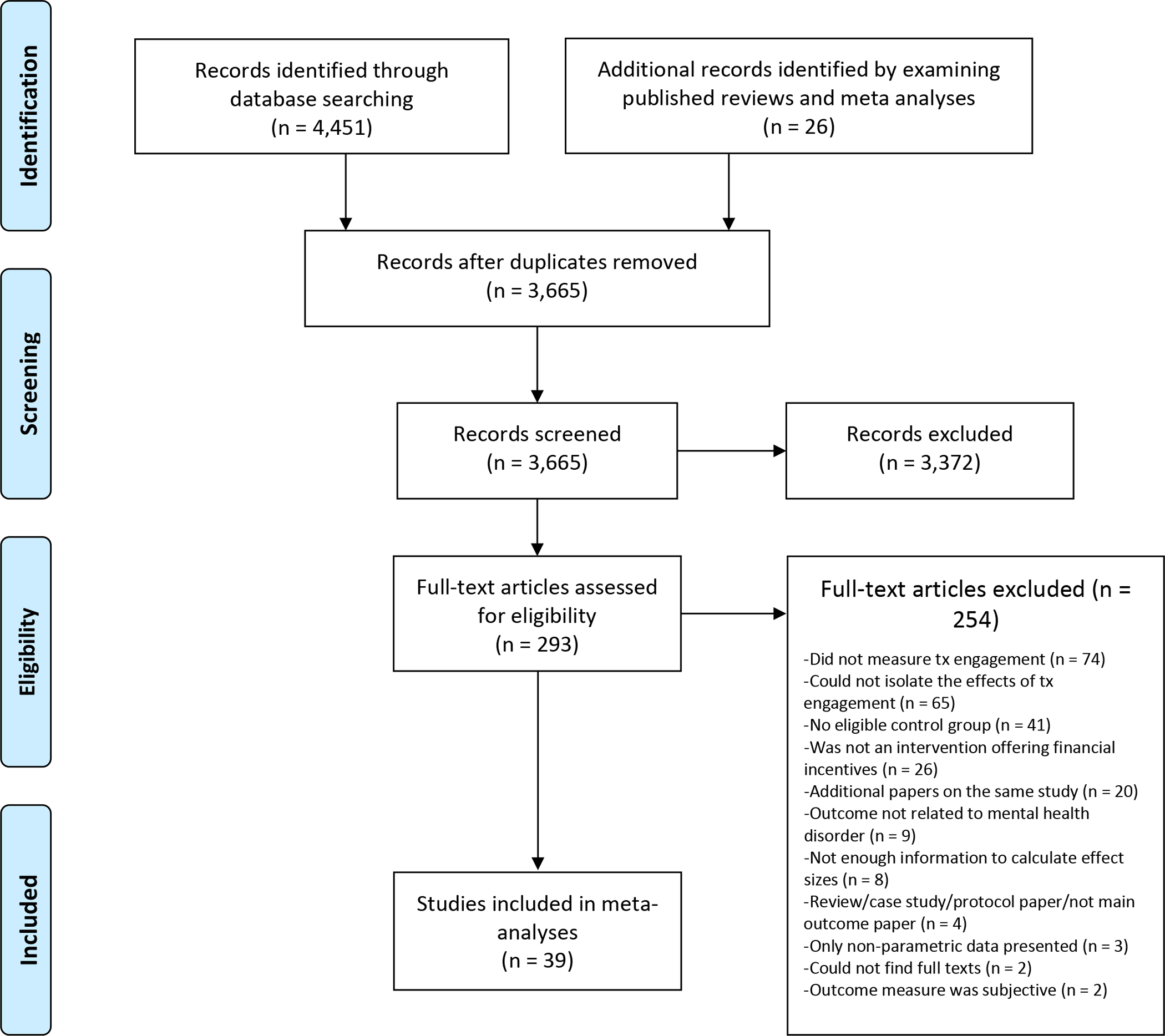

We included a total of 39 studies (Figure 1). These included 30 studies targeting treatment attendance (total N = 4,397): one study also included a separate medication adherence outcome and two studies included separate treatment goal completion outcomes (Table S2). There were six medication adherence studies (total N = 586) and five treatment goal completion studies (total N = 375), plus one that only included secondary outcome measures (Petry et al., 2006) for a total of six. The number of randomized studies included were 16 for treatment attendance, 6 for medication adherence, and 3 for goal completion outcomes. The largest number of studies previously included in a meta-analysis was 5 (Pfund et al., 2021; Table S1).

Figure 1. PRISMA diagram of study selection.

Note. Tx = treatment

We obtained effect size information from authors for 5 studies (2 for main outcomes and 3 for symptom and functional outcomes; Tables S2 and S4). Of the 39 included studies, 31 (79%) incentivized engagement in treatment for substance use disorders (Table S2). Studies only received strong (k = 29) or moderate (k = 10) quality ratings. Across studies, 47.9% of participants were female (SD = 27.5%) and 49.4% were from racial or ethnic minority groups (SD = 29.5%); the average age was 37.33 years old (SD = 6.70). Interventions lasted an average of 15.53 weeks (SD = 19.28), included 17.65 incentivized sessions (SD = 17.67), and offered incentives worth a maximum of $303 (SD = $346) per participant (Table S2).

Main Outcomes

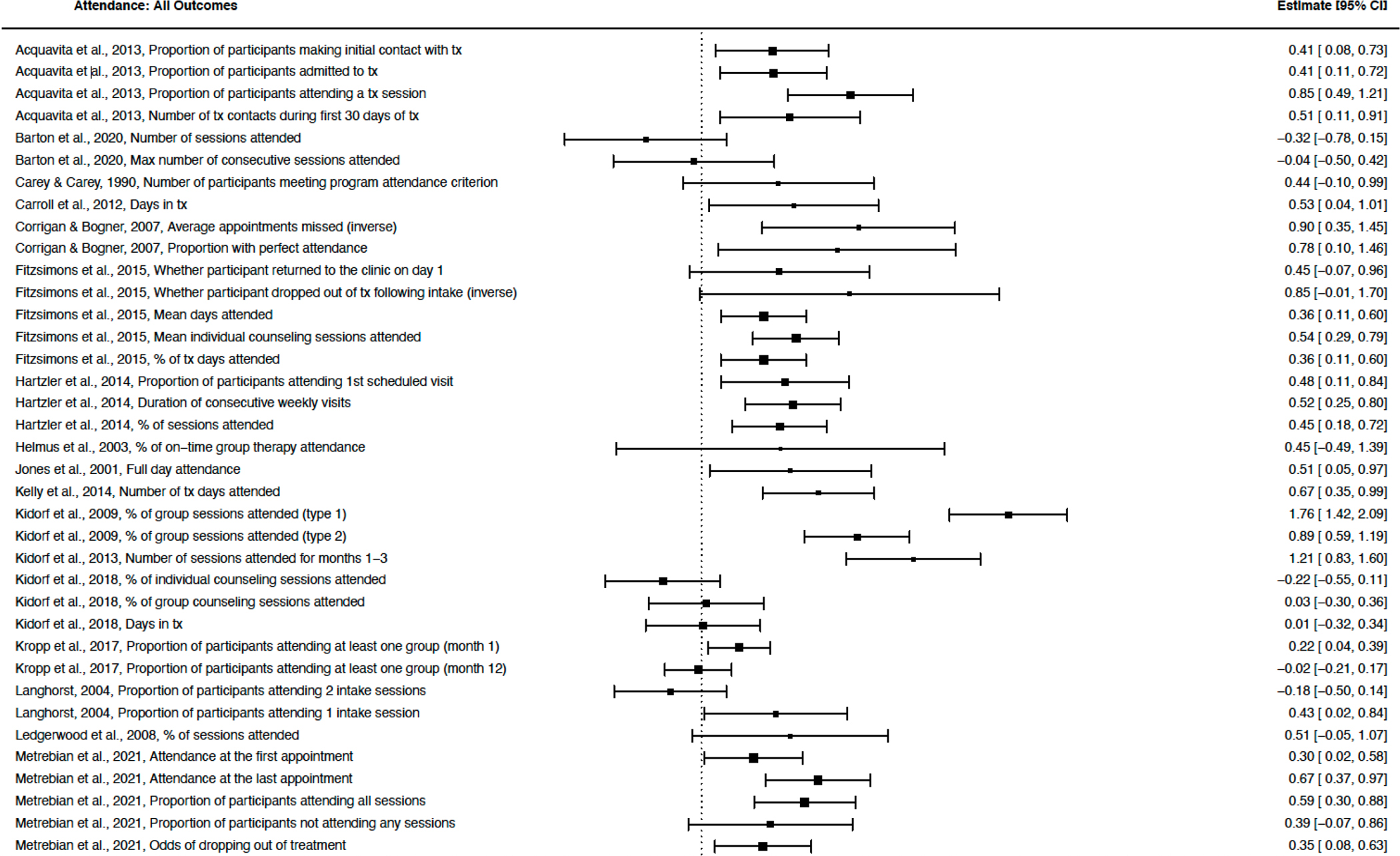

Financial incentives increased mental health treatment attendance (Figure 2) with a moderate effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.49, p < .001, 95% CI [0.33, 0.64], k = 30, I2 = 83.14; Table 2, Model 1). Most studies incentivized treatment attendance for substance use disorders (k = 26), with a minority focusing on treatment for other mental health disorders (k = 4; Table S2). This effect was similar when including only primary outcomes (0.49, p < .001, 95% CI [0.31, 0.67], k = 23, I2 = 77.18; Figure S1), only randomized studies (0.52, p < .001, 95% CI [0.29, 0.74], k = 16, I2 = 86.36), and only high-quality studies (0.51, p < .001, 95% CI [0.33, 0.69], k = 21, I2 = 84.16; Table 2, Models 3–5). In primary outcome analyses (Table 2, Model 2), Kidorf et al., 2009 emerged as an outlier. This randomized study was rated as high quality and included a large sample (N = 188). For Model 2, we pooled effect sizes from two different types of group sessions (type 1: Hedges’ g = 1.76, SE = 0.17; type 2: Hedges’ g = 0.89, SE = .15). This effect size may be particularly large because of the low rate of treatment attendance in the control group (only 6% of sessions were attended). Regardless, effect sizes were similar with this study included (0.53) and excluded (0.49).

Figure 2.

Attendance: All Outcomes

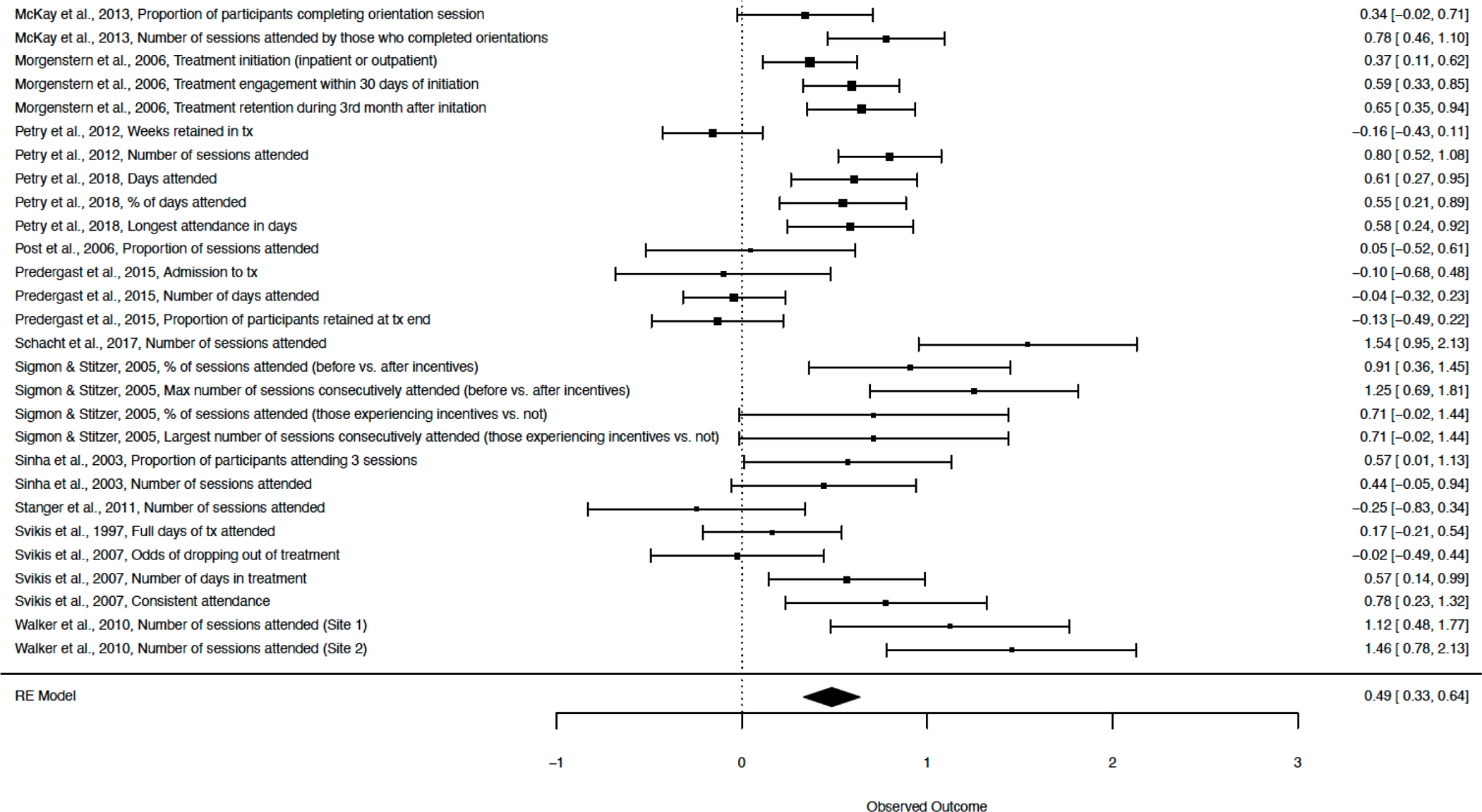

Financial incentives also increased medication adherence with a large effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.95, p < .001, 95% CI [0.47, 1.44], k = 6, I2 = 87.73; Figure 3) that remained large when only primary outcomes (Hedges’ g = 0.89, p = .002, 95% CI [0.33, 1.45], k = 6, I2 = 89.48; Figure S2) and high-quality studies were included (Hedges’ g = 0.83, p = .003, 95% CI [0.35, 1.31], k = 5, I2 = 86.57; Table 2, Models 6–8). Studies incentivized medications for substance use disorders (k = 3), schizophrenia spectrum disorders (k = 2), and depression (k = 1). All medication adherence studies were randomized, but effect sizes should be interpreted with caution given the small number of studies analyzed.

Figure 3.

Medication: All Outcomes

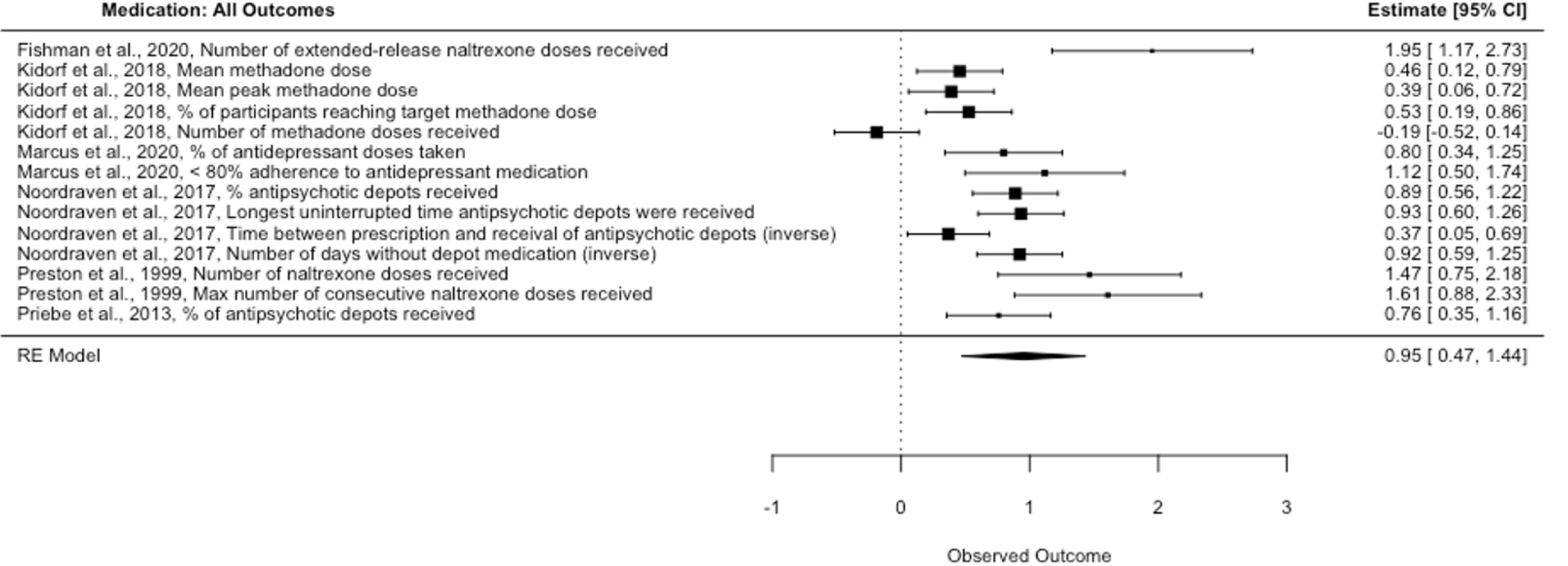

Financial incentives also improved treatment goal completion (Figure 4) with a moderate to large effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.61, p = .008, 95% CI [0.22, 0.99], k = 5, I2 = 60.55; Table 2, Model 9). Studies targeted homework completion (k = 3), signing of treatment plans (k = 1), and reductions in problematic behavior (reductions in clutter for hoarding disorder, rated by a blinded evaluator, k = 1). Studies incentivized treatment for substance use disorders (k = 4) and hoarding disorder (k = 1). This effect size should also be interpreted with caution given the exploratory nature of this analysis and because few studies were included. We did not analyze primary outcomes, randomized studies, or high-quality studies for this outcome, as there were too few studies to do so.

Figure 4.

Treatment Goal Completion: All Outcomes

Secondary Symptom and Functional Outcomes

Secondary outcomes related to symptoms and functioning included (1) self- or clinician-rated measures of mental health symptoms, functioning, and quality of life, and (2) measures of substance use based on urine toxicology screens (Tables S4–S5 and Figures S4–S8). Few studies included these measures (k = 4–6 per outcome). Financial incentives targeting treatment attendance marginally improved self- or clinical-rated measures with a small effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.10, p = .060, 95% CI [0.00, 0.20], k = 6, I2 = 0.00; Table 2, Model 10 and Figure S4). Post-hoc analyses, based on observations of effect sizes (Figure S4), showed that when excluding measures assessing substance use symptoms, treatment attendance significantly improved symptom and functional outcomes (Hedges’ g = 0.15, p = .027, 95% CI [0.02, 0.27], k = 5, I2 = 0.00; Figure S5). Financial incentives targeting treatment attendance also marginally improved substance use measures based on urine toxicology screens with a small effect size (Hedges’ g = 0.23, p = .054, 95% CI [−0.01, 0.46], k = 6, I2 = 36.15; Table 2, Model 11 and Figure S6). Financial incentives for medication adherence and treatment goal completion did not significantly improve self- or clinician-rated measures (Hedges’ g = −0.02 – 0.18, both p < .792; Table 2 Models 12 and 13 and Figures S7–S8). We did not examine substance use based on urine toxicology screens for medication adherence or goal completion outcomes as there were too few studies in these categories.

Heterogeneity

All models showed evidence of significant heterogeneity across effect sizes (all Q > 14.96, all p < .022), with the exception of three symptom and functional outcome models (Table 2, Models 10, 11, and 13). I2 statistics for models with significant heterogeneity indicated high heterogeneity levels (61%–89%). For 3-level models, there tended to be greater heterogeneity across studies (Level 3 I2 in Table 2) than across effect sizes within the same study (Level 2 I2), with the exception of studies targeting treatment goal completion (Models 9 and 13). In these models, heterogeneity was present across effect sizes (24–61%) but not across studies (0%), likely because of the limited variability across studies and the large variability across effect sizes in Stanger et al., 2011 (Figure 4) and Petry et al., 2006 (Figure S8).

Moderators and Publication Bias

None of the study characteristics tested moderated the effect of financial incentives on treatment attendance (all F < 3.61, all p > .062, k = 18–30; Table S6). The funnel plot (Figure S3) did not show evidence of publication bias, a conclusion that was supported by a non-significant Egger’s test (z = 0.51, p = .610). The horizontal, symmetrical scatter of studies in the funnel plot indicates heterogeneity of effect sizes across studies (Sterne et al., 2011), but no relationship between effect sizes and measures of variance (standard errors).

Discussion

We evaluated the efficacy of using financial incentives to improve mental health treatment engagement in 39 studies, of which 79% incentivized engagement in treatment for substance use disorders. Consistent with our hypotheses, financial incentives increased treatment attendance (Hedges’ g = 0.49) and medication adherence (Hedges’ g = 0.95). As an exploratory aim, we assessed the impact of financial incentives on treatment goal completion. We found that incentives increased this outcome as well (Hedges’ g = 0.61), which was operationalized as targeting homework completion, committing to treatment plans, and showing reductions in hoarding behavior. Effect sizes were very similar when restricting to outcome measures common across studies and to only randomized and high-quality studies.

Secondarily, we found that targeting treatment attendance marginally improved self-reported or clinician-rated symptom and functional outcomes (mental health symptoms, functioning, or quality of life; Hedges’ g = 0.10, p = .060) and substance use measures based on urine toxicology screens (Hedges’ g = 0.23, p = .054). Targeting medication adherence and treatment goal completion, however, did not improve symptom or functional outcomes (Hedges’ g = −0.02 – 0.18). Contrary to our hypotheses, we found no significant moderators of studies targeting treatment attendance. While no evidence for publication bias in studies targeting treatment attendance emerged, we did not test for publication bias or moderators in studies targeting medication adherence or treatment goal completion because there were too few studies.

Relationship to Previous Research

Main Outcomes

Our findings confirm those of previous meta-analyses showing that offering financial incentives can promote changes in behavior, including abstaining from substances, quitting smoking, and attending health screening appointments (Davis et al., 2016, Lee et al., 2014; Sigmon & Patrick, 2012). We also extend the findings of meta-analyses demonstrating that providing financial incentives increases treatment attendance for individuals receiving medication for opioid use disorder (Bolivar et al., 2021) and treatment for substance use disorders (Lussier et al., 2006; Pfund et al., 2021) in two important ways. First, while previous meta-analyses were limited to 10 or fewer studies, we included 30 studies and showed that effect sizes were essentially unchanged when restricting to only randomized or high-quality studies. Effect sizes in previous analyses ranged from small (Lussier et al., 2006) to large (Bolivar et al., 2021), but we found evidence for a moderate effect most comparable to Pfund et al. (2021). Second, while all previous meta-analyses included studies in which multiple behaviors were incentivized together, we included only those studies for which it was possible to isolate the effect of incentivizing treatment attendance. Therefore, this is the first meta-analysis to demonstrate that incentivizing treatment attendance specifically improves this outcome.

The present meta-analysis also extends the findings of previous meta-analyses showing that offering financial incentives increases medication adherence for individuals receiving medication for opioid use disorder (Bolivar et al., 2021), treatment for substance use disorders (Lussier et al., 2006), or treatment for any medical or mental health condition (Petry et al., 2012). The large effect we found is most comparable to the one presented in Petry et al. (2012) versus the moderate effects presented in Bolivar et al. (2021) and Lussier et al. (2006). We add to these findings by synthesizing the results of studies incentivizing medication adherence for psychotic disorders (k = 2) and depression (k = 1) in addition to substance use disorders (k = 3). Additionally, while all included studies were randomized, we found that the effect of incentives on medication adherence remained large when including only high-quality studies. As stated above, unlike previous studies, our inclusion criteria also enabled us to show that targeting medication adherence specifically improves this outcome.

Finally, this is the first study to show that it may be effective to provide incentives for achieving treatment goals, including completing homework, committing to treatment plans, and showing reductions in problematic behavior. Importantly, as most studies included in our analyses targeted treatments for substance use disorders, we can conclude that financial incentives are effective for increasing engagement in substance use treatment and that there is preliminary evidence of their effectiveness for increasing engagement in treatment for other mental health disorders, pending further research.

Secondary Symptom and Functional Outcomes

We are unaware of a meta-analysis that examined the impact of financial incentives on self-reported or clinician-rated symptom and functional outcomes. By contrast, our results align with those of a previous meta-analysis demonstrating that targeting treatment attendance for substance use disorders improves substance use as measured by urine toxicology screens (Pfund et al., 2021). While both studies found evidence for small effects, ours were marginally significant and those in Pfund et al. (2021) were significant. Overall, our observation of null to small effects that were marginally or not significant is not surprising, as studies have found that when financial incentives are provided, the greatest change is observed for the targeted outcome (e.g., attendance) rather than for non-targeted outcomes like symptoms or functioning (Petry et al., 2006). Additionally, a study showing that targeting attendance led to improvements in patients with lower severity, but not higher severity symptoms suggests that sample or intervention characteristics may moderate changes in symptom or functional outcomes (Petry, Barry et al., 2012). Moreover, as only a minority of studies included assessments of symptoms or functioning, it is challenging to determine the effect of treatment on these outcomes.

In addition to findings related to symptoms and functioning, there is conflicting evidence about whether the effect of financial incentives on abstinence and other outcomes (e.g., physical activity) lasts beyond the point at which incentives are withdrawn (Benishek et al., 2014; Davis et al., 2016; Ginley et al., 2021), a question we were unable to address in our analysis. This research suggests that more permanent changes in outcomes, and in symptom and functional outcomes, may require longer periods of reinforcement, a more gradual or explicit transition to naturally occurring reinforcers (e.g., social support), or additional interventions to improve symptom and functional outcomes (Benishek et al., 2014; Ginley et al., 2021; Noordraven, Wierdsma et al., 2017). Taken together, these findings indicate a need to better understand the conditions under which providing incentives for mental health treatment engagement leads to improvements in symptoms and functioning, as well as long-term improvements in outcomes.

Moderators

We did not replicate findings from previous meta-analyses that reported larger effect sizes in studies with longer interventions, more incentivized sessions, higher incentives, more immediate reward delivery, and non-randomized designs, as well as those of higher quality (Davis et al., 2016; Ginley et al., 2021; Griffith et al., 2000; Lussier et al., 2006; Petry, Rash et al., 2012; Pfund et al., 2021). Our findings of significant heterogeneity across studies and no significant effects of moderators suggests that we did not account for all relevant moderators in our analysis.

Clinical Implications

The present study adds to a growing body of work demonstrating that financial incentives effectively improve the targeted outcome. Unfortunately, while financial incentives are well established as a strategy to promote abstinence from substances and are gaining recognition as a method of enhancing physical health behavior change, few studies have tested financial incentives as a method of improving treatment engagement for mental health disorders aside from substance use. This is problematic, as individuals with mental health disorders demonstrate particularly low levels of treatment engagement and could benefit substantially from interventions that provide additional motivation to initiate and continue treatment.

The papers included in our analysis suggest multiple ways that financial incentives may be utilized to enhance mental health treatment engagement. Incentives can be used at the start of treatment to improve attendance for initial or intake sessions (Fitzsimons et al., 2015) or for preliminary treatment goals like signing a treatment plan (Corrigan & Bogner, 2005). They can reduce rates of treatment discontinuation for psychotherapy in individual (Schacht et al., 2017) or group (Hartzler et al., 2014) formats, and also for case management (Morgenstern et al., 2006). Financial incentives may also improve medication adherence for psychosis (Noordraven, Wierdsma et al., 2017), depression (Marcus et al., 2020) or substance use (Preston et al., 1999). Finally, participation in treatment can be encouraged by targeting homework completion (Stanger et al., 2011) or clinician-rated symptom improvement (Worden et al., 2017). While these interventions have the potential to improve mental health treatment engagement, symptom improvement is determined by multiple, complex factors and improving attendance, medication adherence, or even treatment goal completion may not lead to clinically significant change.

Generalizability of Results

Our meta-analysis included studies with diverse samples, treatment settings, and study designs. The included studies were significantly limited, however, in that most of them provided incentives for engaging in treatment for substance use disorders. Therefore, the extent to which our results generalize to non-substance using samples is unknown. Future research should focus on testing the extent to which financial incentives improve engagement in treatment for mental health disorders aside from substance use, and whether intervention efficacy depends on either demographic characteristics or disorder type.

Barriers to Implementation

In addition to the limited research on disorders aside from substance use, there are several other barriers to offering financial incentives for mental health treatment engagement in real-world settings, including: (1) ethical questions, (2) the potential of financial incentives to undercut individuals’ intrinsic motivation to engage in treatment, and (3) difficulties funding these interventions. We briefly review these issues below.

Ethical Concerns

Providing financial incentives for treatment engagement brings up ethical concerns such as whether the practice could be coercive, undermine a patient’s autonomy, change the patient-provider relationship, or reinforce differences among patients with and without financial resources (Marteau et al., 2009; Priebe et al., 2010). One particular concern with incentives for psychotropic medication adherence is that the incentive could change the patient’s risk/benefit calculation and lead them to minimize or underreport side effects or other negative consequences of taking medication (Noordraven, Schermer et al., 2017; Priebe et al., 2010). Interestingly, studies that have evaluated providers’ and patients’ perceptions of interventions offering financial incentives for treatment attendance and medication adherence that have been implemented found high levels of acceptability (Desrosiers et al., 2019; Noordraven, Schermer et al., 2017). Moreover, acceptability tends to improve once it is clear that the intervention is effective (Desrosiers et al., 2019; Giles et al., 2015). Studies have also found that patient-provider relationships can actually improve when financial incentives are offered, likely due to the patient’s increased treatment engagement (Noordraven, Schermer et al., 2017).

Researchers have made several recommendations to minimize ethical concerns for programs offering financial incentives. Participation must be truly voluntary and not result from a patient’s financial need (Giles et al., 2015). Additionally, incentives should be low enough so that patients are not coerced into treatment and made available to all patients regardless of their baseline level of adherence to ensure that they are distributed equitably (Noordraven, Schermer et al., 2017; Priebe et al., 2010). Finally, additional research is needed to further clarify ways to increase the acceptability of these interventions for both providers and patients.

Intrinsic Motivation

Researchers and clinicians have also raised concerns that financial incentives for treatment engagement may undermine individuals’ intrinsic motivation to engage in treatment, particularly once incentives are removed. The impact of rewards on individuals’ subsequent motivation has been examined extensively in the fields of education and economics, and rewards have been found to decrease intrinsic motivation when initial levels of the behavior are high and when there is a conflict of interest between the people involved (Promberger & Marteau, 2013). Studies have not found that patients refuse to engage in treatment following the withdrawal of financial incentives (Benishek et al., 2014; Ginley et al., 2021). Moreover, a recent study found that patients’ intrinsic motivation for treatment did not decrease after they received financial incentives for taking antipsychotic medication (Noordraven et al., 2018a), indicating that financial incentives are unlikely to reduce individuals’ intrinsic motivation for treatment. However, interventions may best be framed as a way to help individuals achieve the level of engagement that they want for themselves but have difficulty attaining, as opposed to the offer of a bribe or payment for attaining a particular outcome (Promberger & Marteau, 2013).

Cost Effectiveness

Another concern relates to the cost of financial incentives (Priebe et al., 2010). Studies examining the cost-effectiveness of offering incentives for treatment engagement have focused on improving medication adherence and have reached different conclusions; one found that this intervention did not increase overall healthcare costs (Henderson et al., 2015), while the other found that it did (Noordraven et al., 2018b). Research on the cost effectiveness of incentivizing other outcomes, like opioid use (Fairley et al., 2021) smoking cessation (van den Brand et al., 2019), and HIV viral suppression (Adamson et al., 2019), have found that these interventions are cost effective in the long term. Interventions utilizing financial incentives may have greater value when their effects are evaluated over longer periods of time and when factors such as individuals’ potential work productivity or criminal justice costs are considered (Adamson et al., 2019; Fairley et al., 2021; Noordraven et al., 2018b). In general, the cost-effectiveness of these interventions depend on contextual factors such as the treatment setting, type of disorder, targeted behavior, and value of incentives (Vlaev et al., 2019). Future research to better understand the contribution of these factors would help clarify the conditions under which offering incentives for treatment engagement is both effective and cost-effective.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has multiple strengths. First, we examined several outcomes, including interventions aimed at improving attendance, medication adherence, and treatment goal completion. Second, we found very similar results when analyses included multiple effect sizes per study compared to when they included only effect sizes common across studies. Results were also similar when analyses included only randomized designs and only high-quality studies. Third, we included only studies that enabled us to isolate the efficacy of targeting mental health treatment engagement versus other outcomes, ensuring that our results reflect the impact of providing incentives for treatment engagement specifically. Fourth, included studies were all of moderate to high quality and there was no indication of publication bias.

Our results should be considered within the context of several limitations, however. First, as most studies included in our analyses targeted treatment for substance use disorders, the extent to which our findings apply to other mental health disorders is unclear. Second, several of our analyses included a small number of studies. Due to the few studies that provided incentives for medication adherence and treatment goal completion, we were unable to examine publication bias or moderators for these outcomes. Relatedly, we included both randomized and non-randomized studies so that our results would be as generalizable as possible. Although our results remained the same with only randomized studies included, the inclusion of non-randomized studies remains a methodological limitation. Third, we included studies targeting treatment goal completion as an exploratory aim and individual study outcomes were diverse (e.g., homework completion, reduction in problematic behaviors), indicating that this effect size should be considered preliminary. Fourth, some studies were excluded because they did not provide enough data to calculate effect sizes (k = 8; Table S3) or because their data were presented in non-parametric forms (k = 3; see Methods). Fifth, only one dissertation met our inclusion criteria, raising the possibility that we excluded other unpublished studies. Finally, we were only able to analyze end-of-treatment outcomes and are therefore unable to comment on the long-term efficacy of financial incentives on treatment engagement.

Regardless of these limitations, this study is the first to show that financial incentives improve engagement in treatment for substance use disorders and may also improve engagement in treatment for other mental health disorders. Researchers and clinicians are encouraged to consider the benefits of these interventions, as well as the need for future research testing incentives in the context of treatment for mental health disorders aside from substance use and investigating how these interventions can be implemented in the most effective, enduring, and ethical manner.

Supplementary Material

Public health significance:

This study shows that it is effective to offer people seeking substance use treatment, and potentially also those seeking treatment for other mental health disorders, financial incentives to encourage them to attend treatment, take medication, and meet treatment goals.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs (Dr. Khazanov). It was also provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs Clinical Science Research and Development Service (grant IK2CX001501 to Dr. Boland). The Office of Academic Affiliations had no role in the study design, collection, analysis or interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication. The views expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the United States Government or the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Footnotes

The authors report no direct conflicts of interest. Michael Thase, MD, also reports no direct conflicts of interest, but discloses the following activities with commercial entities over the past three years: 1) he has received fees as a consultant or advisor from Acadia, Allergan, Axsome, Boehringer Ingelheim, Clexio Biosciences, H. Lundbeck A/S, Jazz, Janssen (Johnson & Johnson), Merck, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sage, Seelos, Sunovion, and Takeda; 2) his program has received funds for research support from Acadia, Allergan, AssureRx Health, Axsome, Intracellular, Janssen (Johnson & Johnson), Merck, Otsuka, and Takeda; and 3) his spouse, Dr. Diane Sloan, is a vice president of Open Health, Ltd., which does business with a number of pharmaceutical companies.

Appendix

No other studies using the same dataset are published, in press, or under review.

References

- Acquavita SP, Stershic S, Sharma R, & Stitzer M (2013). Client incentives versus contracting and staff incentives: How care continuity interventions in substance abuse treatment can improve residential to outpatient transition. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 45(1), 55–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adamson B, El-Sadr W, Dimitrov D, Gamble T, Beauchamp G, Carlson JJ, Garrison L, & Donnell D (2019). The cost-effectiveness of financial incentives for viral suppression: HPTN 065 study. Value in Health, 22(2), 194–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Ananthapavan J, Peterson A, & Sacks G (2018). Paying people to lose weight: The effectiveness of financial incentives provided by health insurers for the prevention and management of overweight and obesity - a systematic review. Obesity Reviews, 19(5), 605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum M, Cooper H, Kline RB, Mayo-Wilson E, Nezu AM, & Rao SM (2018). Journal article reporting standards for quantitative research in psychology: The APA Publications and Communications Board task force report. American Psychologist, 73, 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armijo-Olivo S, Stiles CR, Hagen NA, Biondo PD, & Cummings GG (2012). Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(1), 12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton RM, Malte CA, & Hawkins EJ (2020). Smoking cessation group attendance in a substance use disorder clinic: A look at contingency management and other factors to maximize engagement. Journal of Social Work Practice in the Addictions, 20(1), 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Belsley DA, Kuh E, & Welsch RE (1980). Regression diagnostics: Identifying influential data and sources of collinearity. Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Benishek LA, Dugosh KL, Kirby KC, Matejkowski J, Clements NT, Seymour BL, & Festinger DS (2014). Prize-based contingency management for the treatment of substance abusers: A meta-analysis. Addiction, 109(9), 1426–1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolívar HA, Klemperer EM, Coleman SR, DeSarno M, Skelly JM, & Higgins ST (2021). Contingency management for patients receiving medication for opioid use disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA psychiatry, 78(10), 1092–1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, & Rothstein HR (2009). Converting among effect sizes. Introduction to meta-analysis, 45–49. [Google Scholar]

- Businelle MS, Rash CJ, Burke RS, & Parker JD (2009). Using vouchers to increase continuing care participation in veterans: Does magnitude matter? The American Journal on Addictions, 18(2), 122–129. doi: 10.1080/10550490802545125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, & Carey MP (1990). Enhancing the treatment attendance of mentally ill chemical abusers. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 21(3), 205–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Nich C, Lapaglia DM, Peters EN, Easton CJ, & Petry NM (2012). Combining cognitive behavioral therapy and contingency management to enhance their effects in treating cannabis dependence: Less can be more, more or less. Addiction, 107(9), 1650–1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook RD (1977). Detection of influential observation in linear regression. Technometrics, 19(1), 15–18. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, & Bogner J (2007). Interventions to promote retention in substance abuse treatment. Brain Injury, 21(4), 343–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, Bogner J, Lamb-Hart G, Heinemann AW, & Moore D (2005). Increasing substance abuse treatment compliance for persons with traumatic brain injury. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 19(2), 131–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis DR, Kurti AN, Skelly JM, Redner R, White TJ, & Higgins ST (2016). A review of the literature on contingency management in the treatment of substance use disorders, 2009–2014. Preventive Medicine, 92, 36–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desrosiers JJ, Tchiloemba B, Boyadjieva R, & Jutras-Aswad D (2019). Implementation of a contingency approach for people with co-occurring substance use and psychiatric disorders: Acceptability and feasibility pilot study. Addictive Behaviors Reports, 10, 100223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutra L, Stathopoulou G, Basden SL, Leyro TM, Powers MB, & Otto MW (2008). A meta-analytic review of psychosocial interventions for substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry, 165(2), 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, & Minder C (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairley M, Humphreys K, Joyce VR, Bounthavong M, Trafton J, Combs A, ... & Owens DK (2021). Cost-effectiveness of treatments for opioid use disorder. JAMA Psychiatry, 78(7), 767–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenger M, Mortensen EL, Poulsen S, & Lau M (2011). No-shows, drop-outs and completers in psychotherapeutic treatment: Demographic and clinical predictors in a large sample of non-psychotic patients. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 65(3), 183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fishman M, Wenzel K, Vo H, Wildberger J, & Burgower R (2021). A pilot randomized controlled trial of assertive treatment including family involvement and home delivery of medication for young adults with opioid use disorder. Addiction, 116(3), 548–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzsimons H, Tuten M, Borsuk C, Lookatch S, & Hanks L (2015). Clinician-delivered contingency management increases engagement and attendance in drug and alcohol treatment. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 152, 62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles EL, Robalino S, Sniehotta FF, Adams J, & McColl E (2015). Acceptability of financial incentives for encouraging uptake of healthy behaviours: A critical review using systematic methods. Preventive Medicine, 73, 145–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginley MK, Pfund RA, Rash CJ, & Zajac K (2021). Long-term efficacy of contingency management treatment based on objective indicators of abstinence from illicit substance use up to 1 year following treatment: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 89(1), 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goulet-Pelletier J-C, & Cousineau D (2018). A review of effect sizes and their confidence intervals, Part I: The Cohen’s d family. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 14(4), 242–265. [Google Scholar]

- Griffith JD, Rowan-Szal GA, Roark RR, & Simpson DD (2000). Contingency management in outpatient methadone treatment: A meta-analysis. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 58(1–2), 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallgren KA (2012). Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: An overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 8(1), 23–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrer M, Cuijpers P, & Ebert D (2019). Doing meta-analysis in R.

- Hartzler B, Jackson TR, Jones BE, Beadnell B, & Calsyn DA (2014). Disseminating contingency management: Impacts of staff training and implementation at an opiate treatment program. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 46(4), 429–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes AF, & Krippendorff K (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. [Google Scholar]

- Helmus TC, Saules KK, Schoener EP, & Roll JM (2003). Reinforcement of counseling attendance and alcohol abstinence in a community-based dual-diagnosis treatment program: A feasibility study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(3), 249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Knapp M, Yeeles K, Bremner S, Eldridge S, David AS, O’Connell N, Burns T, & Priebe S (2015). Cost-effectiveness of financial incentives to promote adherence to depot antipsychotic medication: Economic evaluation of a cluster-randomised controlled trial. PLOS One, 10(10), e0138816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Eldridge S, & Li T (2020). Chapter 23: Including variants on randomized trials. In Higgins et al. (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. Cochrane. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Li T, & Deeks JJ (2020). Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, & Welch VA (Eds), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1. Cochrane. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, & Thompson SG (2002). Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson N, & Waters E (2005). Criteria for the systematic review of health promotion and public health interventions. Health Promotion International, 20(4), 367–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Haug N, Silverman K, Stitzer M, & Svikis D (2001). The effectiveness of incentives in enhancing treatment attendance and drug abstinence in methadone-maintained pregnant women. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 61(3), 297–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazantzis N, Lampropoulos GK, & Deane FP (2005). A national survey of practicing psychologists’ use and attitudes toward homework in psychotherapy. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 742–748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly TM, Daley DC, & Douaihy AB (2014). Contingency management for patients with dual disorders in intensive outpatient treatment for addiction. Journal of Dual Diagnosis, 10(3), 108–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, Brooner RK, Leoutsakos J-M, & Peirce J (2018). Treatment initiation strategies for syringe exchange referrals to methadone maintenance: A randomized clinical trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 187, 343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidorf M, King VL, Neufeld K, Peirce J, Kolodner K, & Brooner RK (2009). Improving substance abuse treatment enrollment in community syringe exchangers. Addiction, 104(5), 786–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropp F, Lewis D, & Winhusen T (2017). The effectiveness of ultra-low magnitude reinforcers: Findings from a “real-world” application of contingency management. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 72, 111–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langhorst DM (2003). The relative contribution of client and program factors influencing early substance abuse treatment retention for women and men. [Doctoral Dissertation, Virginia Commonwealth University]. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global. [Google Scholar]

- Lakens D (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgerwood DM, Alessi SM, Hanson T, Godley MD, & Petry NM (2008). Contingency management for attendance to group substance abuse treatment administered by clinicians in community clinics. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 41(4), 517–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee R, Lee R, Cui RR, Cui RR, Muessig KE, Muessig KE, . . . Tucker JD (2014). Incentivizing HIV/STI testing: A systematic review of the literature. AIDS and Behavior, 18(5), 905–912. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0588-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsey MW, & Wilson DB (2001). Practical meta-analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Litt MD, Kadden RM, Kabela-Cormier E, & Petry N (2007). Changing network support for drinking: Initial findings from the network support project. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 542–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lussier JP, Heil SH, Mongeon JA, Badger GJ, & Higgins ST (2006). A meta-analysis of voucher-based reinforcement therapy for substance use disorders. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 101(2), 192–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus SC, Reilly ME, Zentgraf K, Volpp KG, & Olfson M (2020). Effect of escalating and deescalating financial incentives vs usual care to improve antidepressant adherence: A pilot randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marteau TM, Ashcroft RE, & Oliver A (2009). Using financial incentives to achieve healthy behaviour. BMJ, 338, b1415–b1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIvor R, Ek E, & Carson J (2004). Non-attendance rates among patients attending different grades of psychiatrist and a clinical psychologist within a community mental health clinic. Psychiatric Bulletin, 28(1), 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- McKay JR, Van Horn DHA, Lynch KG, Ivey M, Cary MS, Drapkin ML, Coviello DM, & Plebani JG (2013). An adaptive approach for identifying cocaine dependent patients who benefit from extended continuing care. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(6), 1063–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metrebian N, Weaver T, Goldsmith K, Pilling S, Hellier J, Pickles A, ... & Strang J (2021). Using a pragmatically adapted, low-cost, contingency management intervention to promote heroin abstinence in individuals undergoing treatment for heroin use disorder in UK drug services (PRAISE): A cluster randomised trial. BMJ Open, just accepted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell AJ, & Selmes T (2007b). Why don’t patients attend their appointments? Maintaining engagement with psychiatric services. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 13(6), 423–434. [Google Scholar]

- Morgenstern J, Blanchard KA, McCrady BS, McVeigh KH, Morgan TJ, & Pandina RJ (2006). Effectiveness of intensive case management for substance-dependent women receiving temporary assistance for needy families. American Journal of Public Health, 96(11), 2016–2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]