Abstract

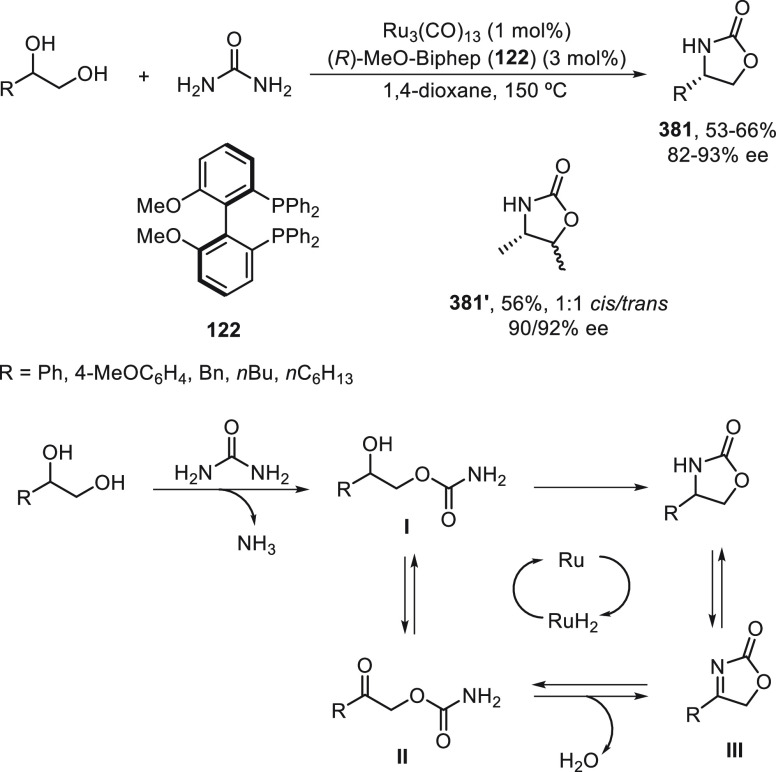

Enantioconvergent catalysis has expanded asymmetric synthesis to new methodologies able to convert racemic compounds into a single enantiomer. This review covers recent advances in transition-metal-catalyzed transformations, such as radical-based cross-coupling of racemic alkyl electrophiles with nucleophiles or racemic alkylmetals with electrophiles and reductive cross-coupling of two electrophiles mainly under Ni/bis(oxazoline) catalysis. C–H functionalization of racemic electrophiles or nucleophiles can be performed in an enantioconvergent manner. Hydroalkylation of alkenes, allenes, and acetylenes is an alternative to cross-coupling reactions. Hydrogen autotransfer has been applied to amination of racemic alcohols and C–C bond forming reactions (Guerbet reaction). Other metal-catalyzed reactions involve addition of racemic allylic systems to carbonyl compounds, propargylation of alcohols and phenols, amination of racemic 3-bromooxindoles, allenylation of carbonyl compounds with racemic allenolates or propargyl bromides, and hydroxylation of racemic 1,3-dicarbonyl compounds.

1. Introduction

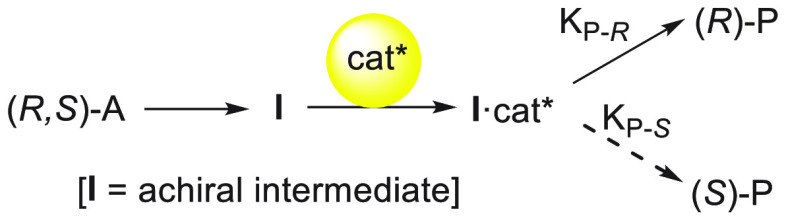

The preparation of enantiopure compounds is a major subject in chemistry. Enantiocatalytic methods are key methodologies nowadays to afford the synthesis of a single enantiomer. Desymmetrization reactions have been extensively applied to achiral or meso-compounds using metal-catalyzed, organocatalyzed, and enzymatic processes.1−19 Conversion of both enantiomers of a racemate into a single enantiomer has been carried out by dynamic kinetic resolutions (DKRs), dynamic kinetic asymmetric transformations (DyKATs), and enantioconvergent processes.20−28 In the case of DKR, the two enantiomers undergo a reversible racemization prior to the selective reaction of one enantiomer with the chiral catalyst, whereas in the DyKATs, the equilibration of both enantiomers is due to the chiral catalyst. In type I DyKATs, both enantiomers are bounded to the catalyst, and these intermediates undergo equilibration, whereas in type II DyKATs, the racemate loses the stereocenter by interaction with the chiral catalyst to form a prochiral intermediate B·cat*. In the case of enantioconvergent reactions, the equilibration is not necessary, and this deracemization methodology does not indicate to control kinetic factors, which are critical in DKRs and DyKATs processes. For enantioconvergent transformations, two enantiomers of the substrate are converted by a stereoablative reaction20 into a prochiral intermediate I that reacts with the chiral catalyst to give one enantiomeric product, for instance, (R)-P (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conversion of racemates into a single enantiomer.

In this Review, we will focus on recent developments of enantioconvergent catalysis for asymmetric transformations. This strategy has become a booming methodology in the last 10 years in asymmetric catalysis mainly under transition metal C–C bond-forming reactions and also under organocatalysis for the preparation of enantioenriched compounds.

2. Enantioconvergent Cross-Couplings

In this Section, C–C bond-forming reactions of alkyl and aryl electrophiles with organometals will be considered. Bond-forming reactions by reaction of alkyl electrophiles with other nucleophiles have been performed in enantioconvergent processes. Reductive cross-electrophile couplings of Csp2–Csp3, Csp3–Csp3, and Csp2–Csp2 under Ni catalysis, as well as photoredox radical coupling, will be included. Cu catalysis under a radical mechanism gives enantioconvergent amination processes.

2.1. Racemic Alkyl Electrophiles with Organometals

Carbon–carbon bond formation under transition-metal-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of acyl and vinyl electrophiles with organometals is an important methodology in organic synthesis.29,30 The development of cross-coupling reactions with alkyl electrophiles, especially secondary systems, was a challenging task because of β-hydride elimination processes31 and has been crucial for asymmetric transformations.32,33 Enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles under Ni catalysis form radicals after the oxidative addition, which react with chiral Ni complexes to form the enantioenriched products.21−25,34−36 In this Section, enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions of secondary alkyl electrophiles with organometals, such as Grignard reagents, organozinc, organoboron, organosilicon, organoindium, organozirconium, organoaluminum, and organotitanium organometallics, will be considered.

2.1.1. Grignard Reagents

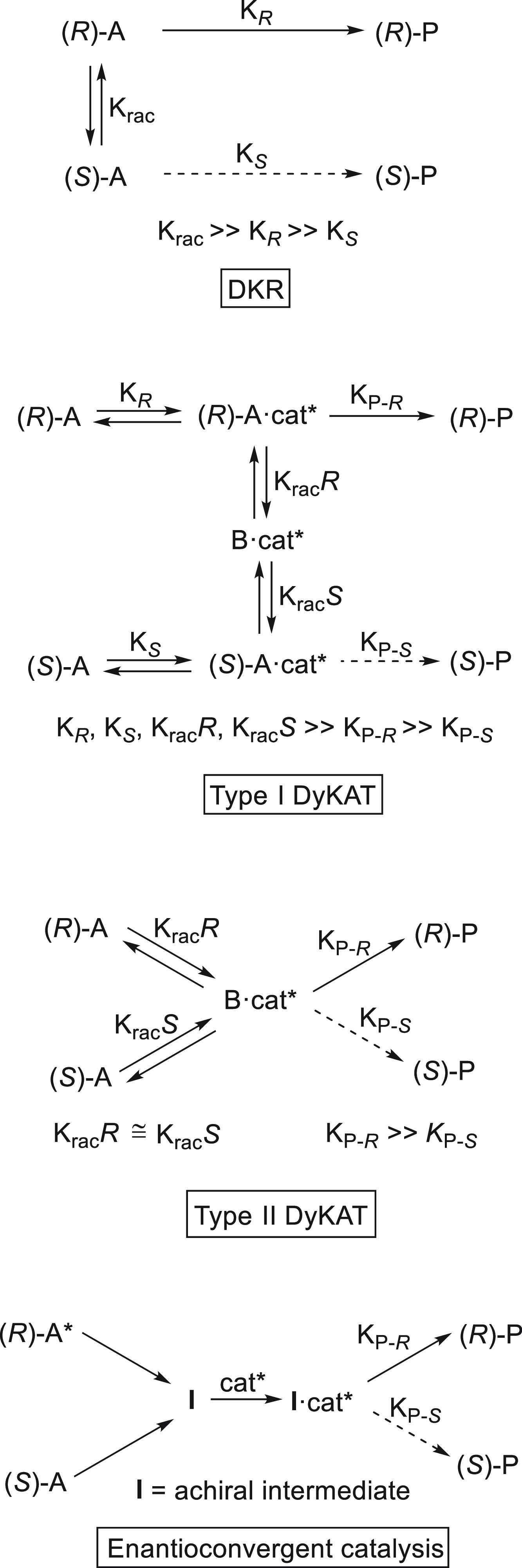

Enantioconvergent Kumada reactions were described for the first time by Lou and Fu.37 Racemic α-bromoketones 1 were coupled with arylmagnesium reagents using chiral nickel/bis(oxazoline) catalyst 2 in dimethoxyethane (DME) at −60 °C (Scheme 1). In the case of alkyl aryl ketones, 7 mol % of NiCl2·glyme and 9 mol % of (R,R)-PhBox (2) were used as catalyst with different arylmagnesium bromides at −60 °C to give the corresponding enantioenriched ketones 3 in good yields (72–91%) and up to 95% ee. When the same reaction conditions were applied to dialkyl ketones 4, ligand 5 gave the best results by working at −40 °C to provide compounds 6 in 70–90% yield and up to 90% ee. Recently, Yin and Fu38 performed mechanistic investigation for the reaction of α-bromo propiophenone with PhMgBr and NiBr2/PhBox as catalyst, thereby establishing that the C–C bond formation process works via a radical chain process. In the proposed catalytic cycle, a nickel radical I abstracts a halogen atom from the α-bromo ketone to generate the radical II and NiBr2(PhBox), which reacts with phenylmagnesium bromide to form intermediate III. Radical II, by reaction with III, gives an organonickel(III) intermediate IV through an out-of-cage pathway. Final reductive elimination of IV affords the coupling product and regenerates the chain-carrying radical I. According to DFT calculations, the coupling between intermediates II and III is the stereochemistry-determining step.

Scheme 1. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Kumada Reactions of α-Bromoketones 1 and 4 with Arylmagnesium Halides.

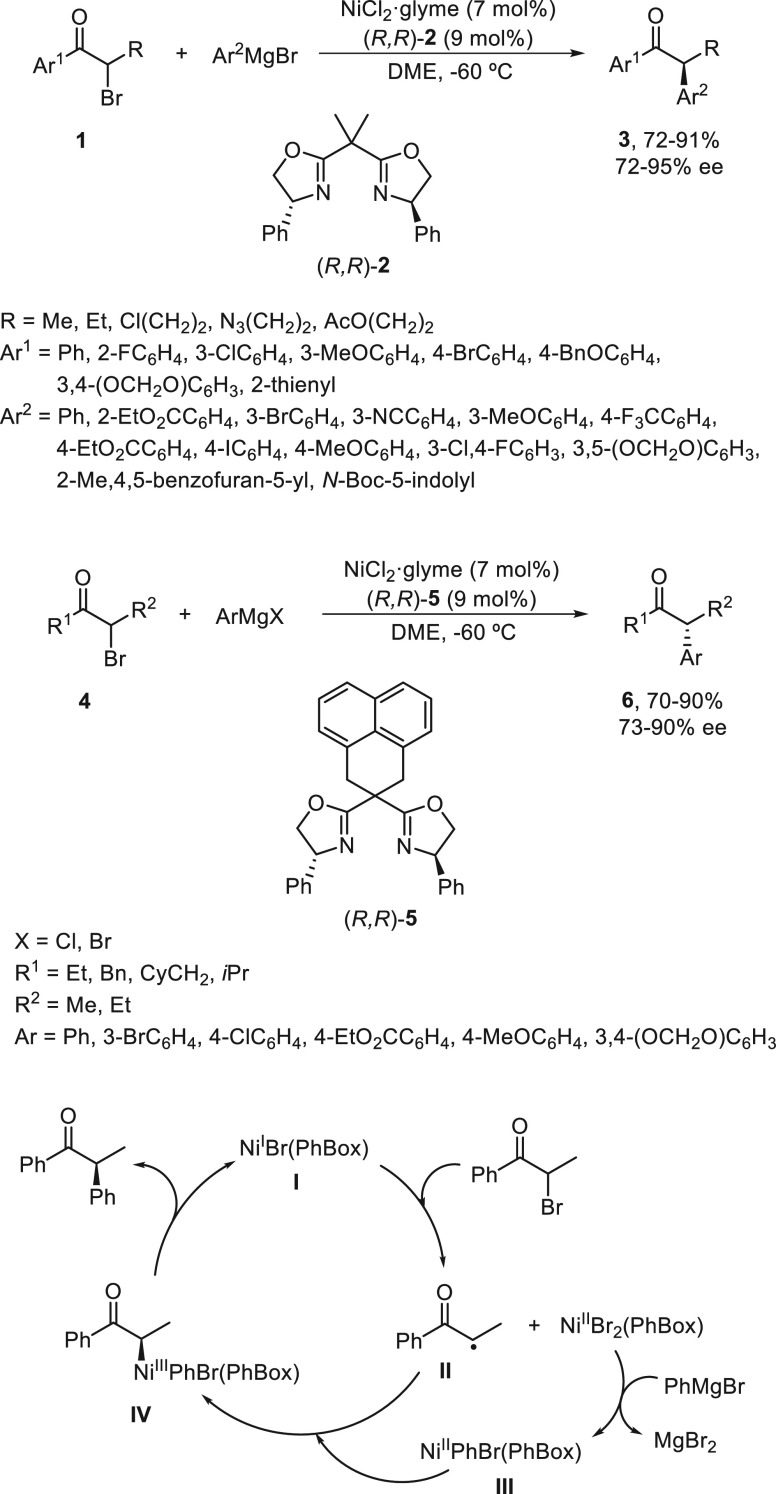

Zhong, Bian, and co-workers39 described the cobalt-catalyzed enantioconvergent Kumada reaction of α-bromo esters 7 using bis(oxazoline) 8 as chiral ligands (Scheme 2). A variety of chiral α-aryl alkanoic esters 9 were prepared using CoI2 (10 mol %) and ligand (R,R)-8 (12 mol %) in THF at −80 °C with good yields (up to 96%) and enantioselectivities (up to 97% ee). This methodology was applied to the synthesis of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) (S)-fenoprofen by Kumada reaction to give ester 10 followed by debenzylation with hydrogen over Pd/C in 92% ee and 70% overall yield. For the total synthesis of (S)-ar-turmerone ester, (R)-11, which was obtained in 88% yield and 93% ee in gram scale, was further transformed in six steps into this sesquiterpene in 92% ee.

Scheme 2. Enantioconvergent Co-Catalyzed Kumada Reactions of α-Bromo Esters 7 with Arylmagnesium Bromide.

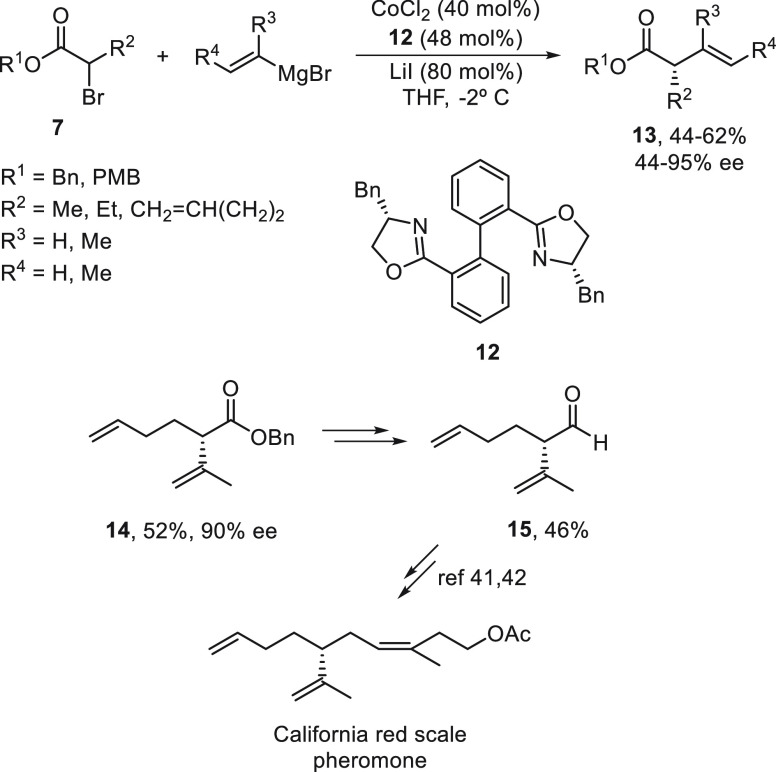

Recently, Zhong’s group40 achieved the Kumada reaction of α-bromo esters 7 with alkenyl Grignard reagents using a cobalt-bis(oxazoline) 12 catalysis to afford highly enantioenriched α-alkyl-β,γ-unsaturated esters 13 (Scheme 3). This enantioconvergent cross-coupling was applied to the formal synthesis of the California red scale pheromone isolated from female Aonidiella aurantia (Maskell). Ester 14 was obtained in 52% yield and 90% ee, and after reduction to the alcohol, oxidation to the aldehyde, and Wittig reaction, (R)-15 was further transformed41,42 into this pheromone. From the radical clock experiments, it could be assumed that this cross-coupling took place via a radical intermediate.

Scheme 3. Enantioconvergent Co-Catalyzed Kumada Reaction of α-Bromo Esters 7 with Alkenyl Grignard Reagents.

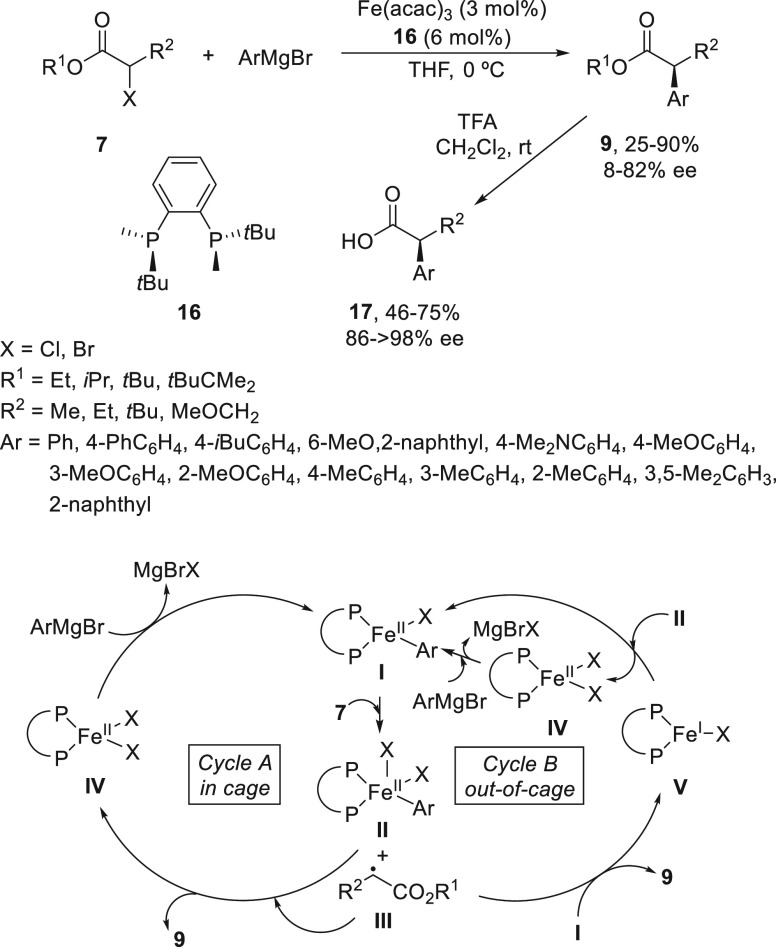

Iron-catalyzed enantioconvergent Kumada reaction of α-chloro and α-bromo alkanoates 7 has been described by Nakamura and co-workers.43 This cross-coupling is catalyzed by Fe(acac)3 and the chiral phosphine (R,R)-BenzP (16) working in THF at 0 °C to give esters 9 in up to 92% yield and 82% ee (Scheme 4). Compounds 9 were readily transformed into the corresponding α-aryl alkanoic acids 17 with up to >98% ee by simple deprotection/recrystallization. Radical probe experiments suggested a catalytic cycle in which the divalent iron species I was generated by partial reduction of Fe(acac)3 by the ligand. This species I abstracts the halogen from the substrate to give the iron species II and radical III. The arylation of intermediate III takes place by the aryl group of the iron species II in the solvent cage to provide the product 9 and the iron complex IV, which undergoes transmetalation with the Grignard reagent to regenerate species I (cycle A). A most favorable alternative process is depicted in cycle B on the basis of a bimetallic mechanism.44 In this out-of-cage mechanism, the radical III escapes from the solvent cage to react with the iron species I to form the coupling product 9 by forming the iron species V. Comproportionation of complexes II and V forms iron(II) species I and IV, or halogen abstraction of V from the α-halo ester 7 forms IV and radical III, which may participate in a chain reaction process.

Scheme 4. Enantioconvergent Fe-Catalyzed Kumada Reactions of α-Chloro and α-Bromo Esters 7 with Arylmagnesium Bromides.

Cross-couplings of α-bromo ketones can be enantioconvergently arylated under Ni/bis(oxazoline) catalysis. This arylation was also performed with α-halogenated esters using arylmagnesium bromides under Co/bis(oxazoline) and by Fe/diphosphine catalysis. Radical processes have been postulated in all these cases.

2.1.2. Organozinc Reagents

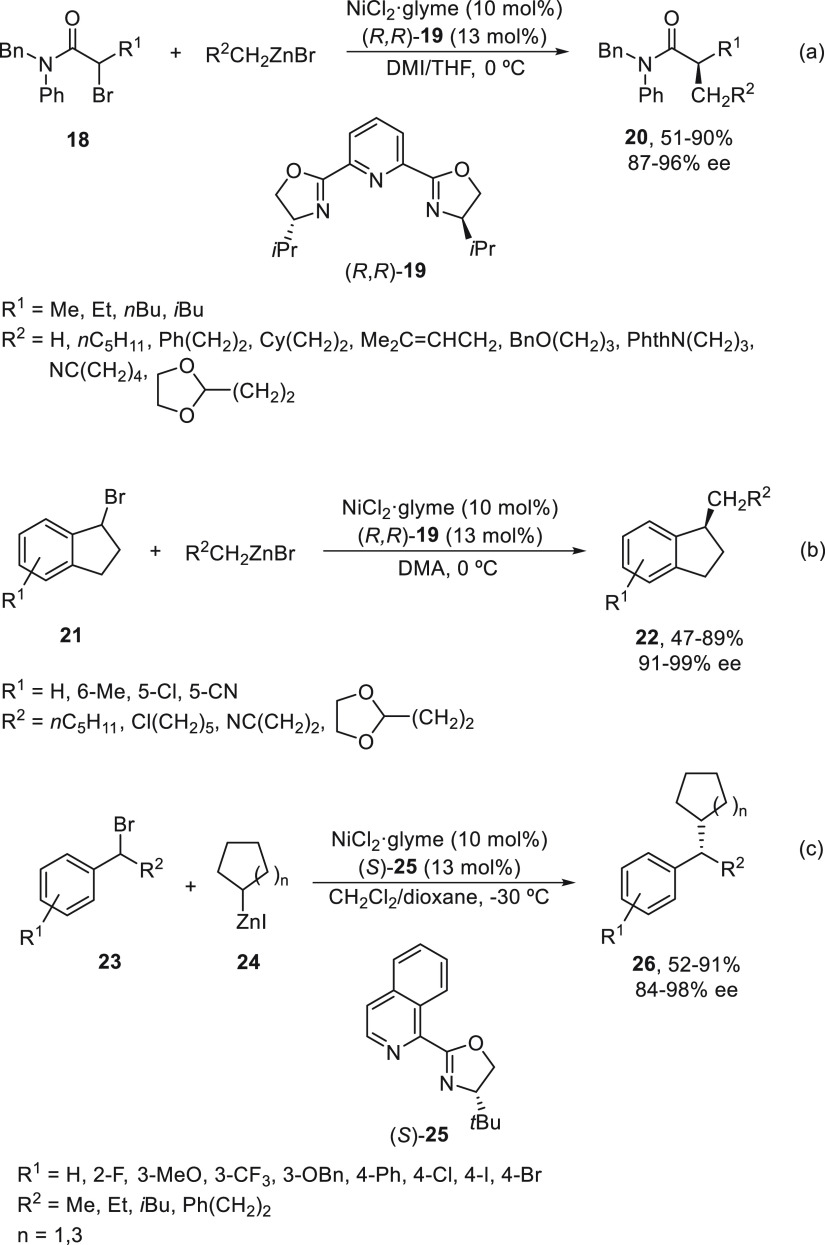

The first advantage in metal-catalyzed enantioconvergent cross-coupling of racemic alkyl electrophiles was performed with organozinc reagents by Fu and co-workers. Using NiCl2·glyme/(R,R)-iPrPyBox (19), α-bromo amides 18 underwent Negishi alkylation with alkylzinc bromides in 1,3-dimethyl-2-imidazolidinone (DMI)/THF at 0 °C to provide products 20 in up to 90% yield (Scheme 5a).45 Secondary benzylic halides, such as bromoindanes 21, reacted with primary alkylzinc bromides to give the corresponding alkylated derivatives 22 using N,N-dimethylacetamide (DMA) as solvent at 0 °C and the same catalyst in up to 89% yield and 99% ee (Scheme 5b).46 Further studies about this sp3–sp3 cross coupling but using secondary alkylzinc iodides 24 showed that an isoquinoline-oxazoline ligand (S)-25 gave the best results for secondary alkyl bromides 23 to afford products 26 in up to 91% yield and 98% ee (Scheme 5c).47

Scheme 5. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of α-Bromo Amides 18 and Benzylic Halides 21 and 23 with Alkylzinc Reagents.

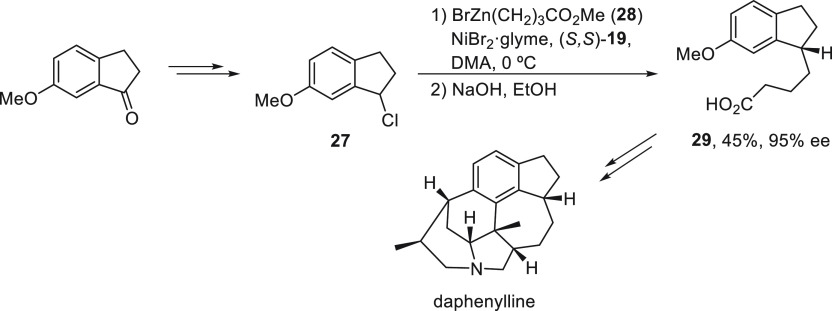

Yokoshima, Fukuyama, and co-workers48 employed this enantioconvergent Negishi reaction in the total synthesis of the alkaloid (−)-daphenylline isolated from the fruit Daphniphyllum longeracemosum.49 The chloroindane 27 reacted with the organozinc reagent 28 using NiBr2·glyme and (S,S)-iPrPyBox (19) as catalyst in DMA at 0 °C to furnish the corresponding acid 29 in 94% ee after hydrolysis and >98% ee after recrystallization of the salt formed with (R)-1-phenylethylamine (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reaction of Chloroindane 27 with Alkylzinc 28.

Mechanistic studies by DFT calculations were performed by Lin and co-workers50 for the Negishi reaction of bromoindoles 21(46) to corroborate the Ni(I)–Ni(III) mechanism containing sequential oxidative addition–reductive elimination, which is more favorable than the Ni(0)–Ni(II) mechanism. In contrast to the calculations of Fu and co-workers38 for the Kumada reaction, in this case, it was suggested that the reductive elimination is the stereochemistry-determining step and not the coupling of the organonickel(II) complex with the organic radical (see Scheme 1).

Fu and co-workers51 obtained poor results when benzylic halides were allowed to react with arylzinc reagents. Instead, racemic benzylic mesylates were efficiently arylated using NiBr2·diglyme (9 mol %) and the bis(oxazoline) (S,S)-31 (Scheme 7). Starting from benzylic alcohols 30 after mesylation, the subsequent Negishi reaction was carried out in a one-pot process to provide 1,1-diarylalkanes 32 up to 98% yield and 95% ee. This method was applied to a gram-scale synthesis of (S)-sertraline tetralone 34 from alcohol 33, a precursor of sertraline hydrochloride (Zoloft, an antidepressant drug).

Scheme 7. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of Benzylic Mesylates with Arylzinc Reagents.

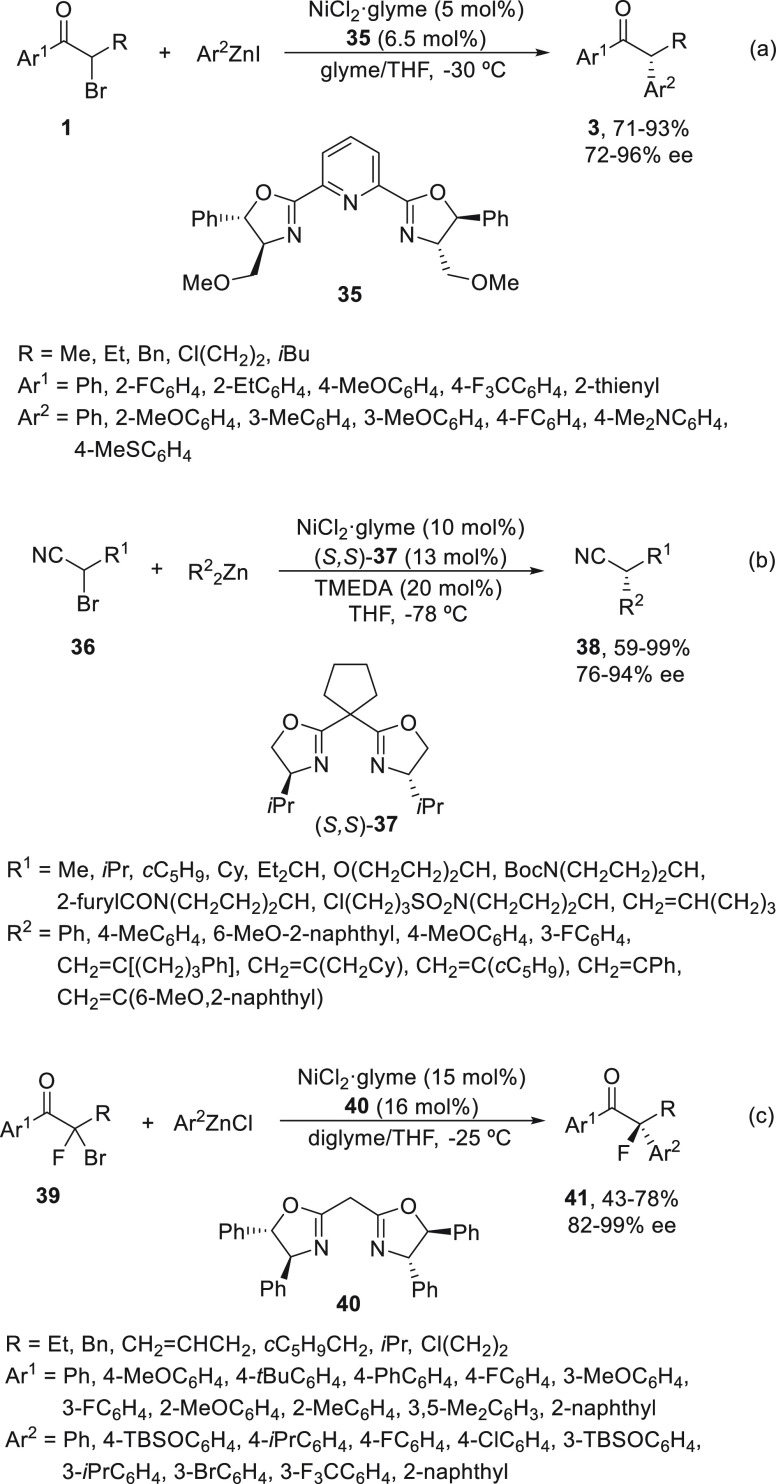

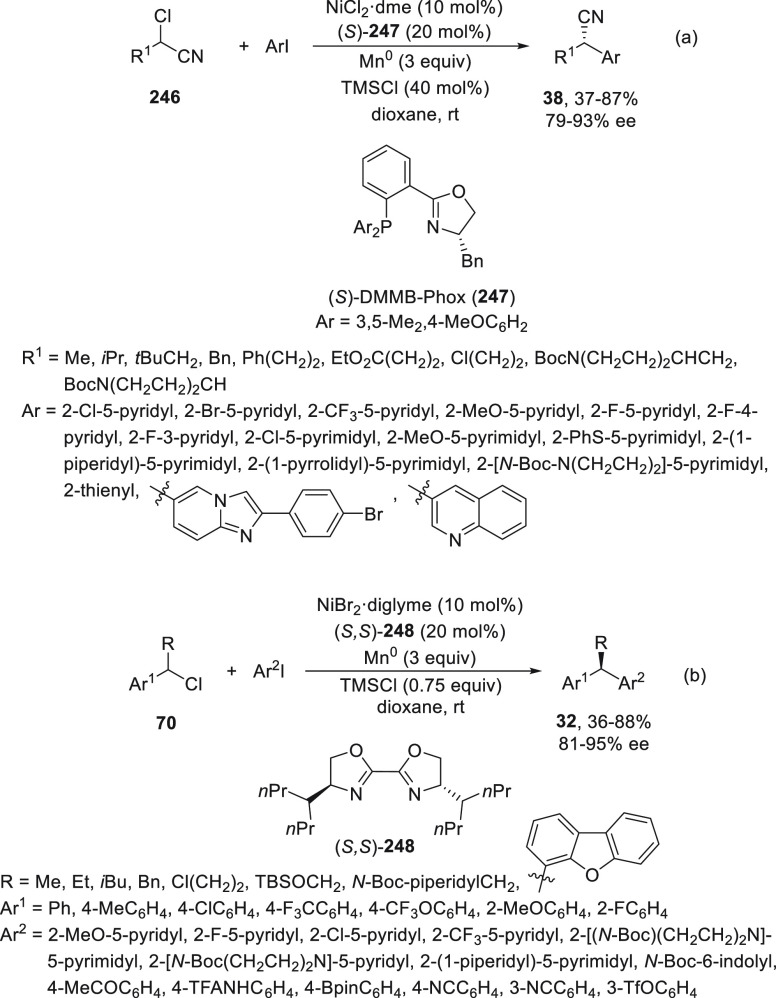

Racemic α-bromo ketones 1 have been arylated to ketones 3 with arylzinc iodides using NiCl2·glyme (5 mol %) and the PyBox ligand 35 with very good yields and enantioselectivities by Fu and co-workers51 (Scheme 8a). If the aryl group of the ketone was bulky, moderate enantioselectivity was observed. The reaction took place under mild reaction conditions with glyme/THF at −30 °C. α-Bromo nitriles 36 underwent enantioconvergent Negishi arylations and alkenylations52 using the PyBox ligand (S,S)-37 in the presence of tetramethylenediamine (TMEDA) (20 mol %) in THF at −78 °C to provide nitriles 38 (Scheme 8b). In this case, substrates prone to undergo cyclization gave acyclic products, which suggests that instead of radical intermediates, this cross-coupling proceeds by conventional oxidative addition. Another case of activated electrophiles is the arylation of α-bromo-α-fluoro ketones 39 using a bis(oxazoline) 40 at −25 °C (Scheme 8c).53 The corresponding tertiary alkyl fluorides 41 were obtained in good yields and high enantioselectivity (up to 99%), which can be further transformed into a variety of organofluorine target molecules.

Scheme 8. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of α-Bromo Ketones 1, α-Bromo Nitriles 36, and α-Bromo-α-fluoro Ketones 39 with Aryl and Alkenylzinc Reagents.

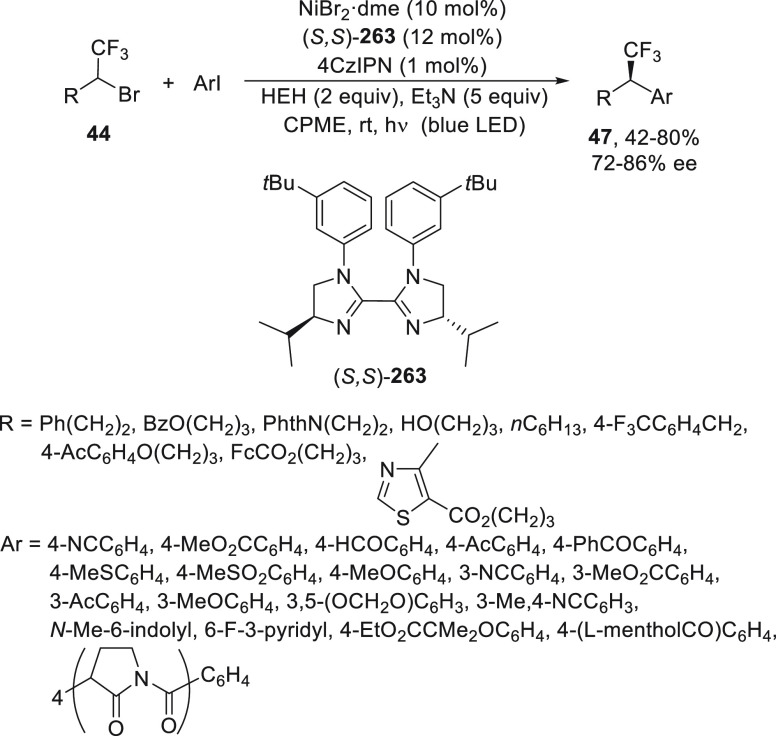

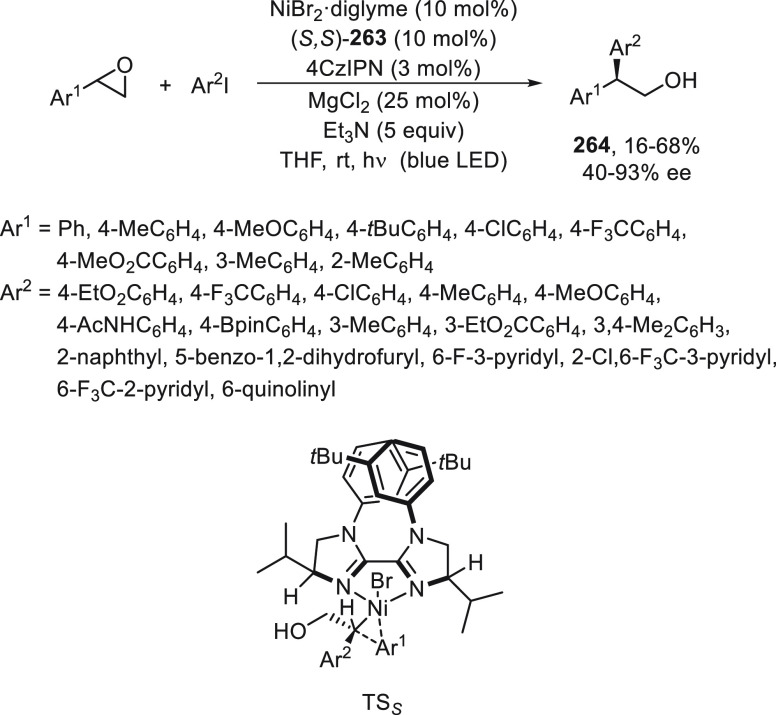

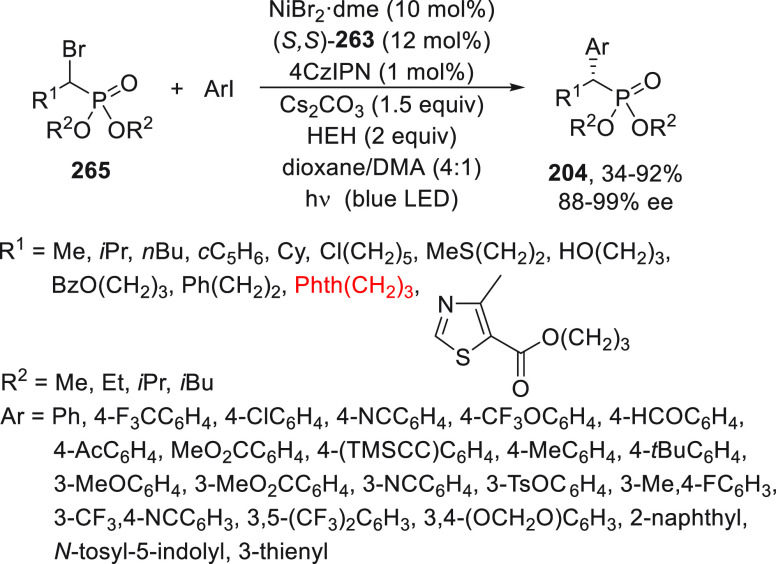

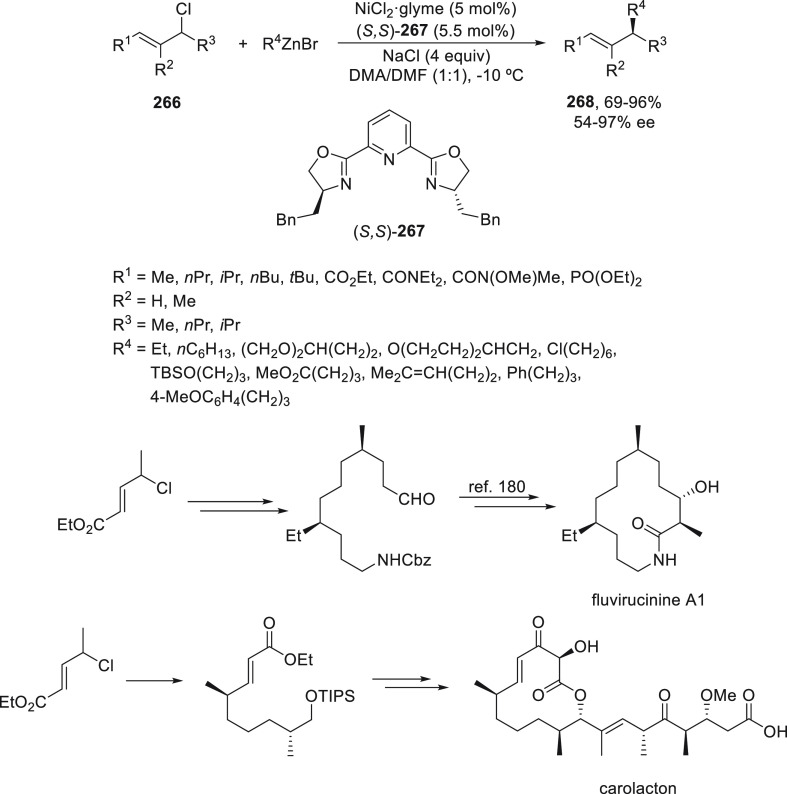

Fu and co-workers54,55 studied the enantioconvergent Negishi reaction of unactivated alkyl electrophiles, such as α-bromo sulfonamides 42(54) and sulfones 43,54 as well as CF3-substituted alkyl bromides 44(55) (Scheme 9). In all cases, NiCl2·glyme/(S,S)-PhBox (2) was used as catalyst at −20 °C with very good enantioselectivity. Sulfonamides 45 and sulfones 46 were obtained by arylation of the starting bromo derivatives 42 and 43, respectively (Scheme 9a).55 Experimental mechanistic studies provided evidence for a radical intermediate that has a sufficient lifetime to escape from the solvent cage and to cyclize onto a pendant olefin. Trifluoromethyl-substituted secondary alkyl bromides 44 were transformed into compounds 47 by reaction with arylzinc chlorides in very good yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 9b).55 It is noteworthy that the Ni catalyst was able to differentiate between a CF3 and an alkyl substituent in the asymmetric cross-coupling.

Scheme 9. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of α-Bromoalkyl Sulfonamides 42 and Sulfones 43, as Well as CF3–Substituted Alkyl Bromides 44 with Arylzinc Reagents.

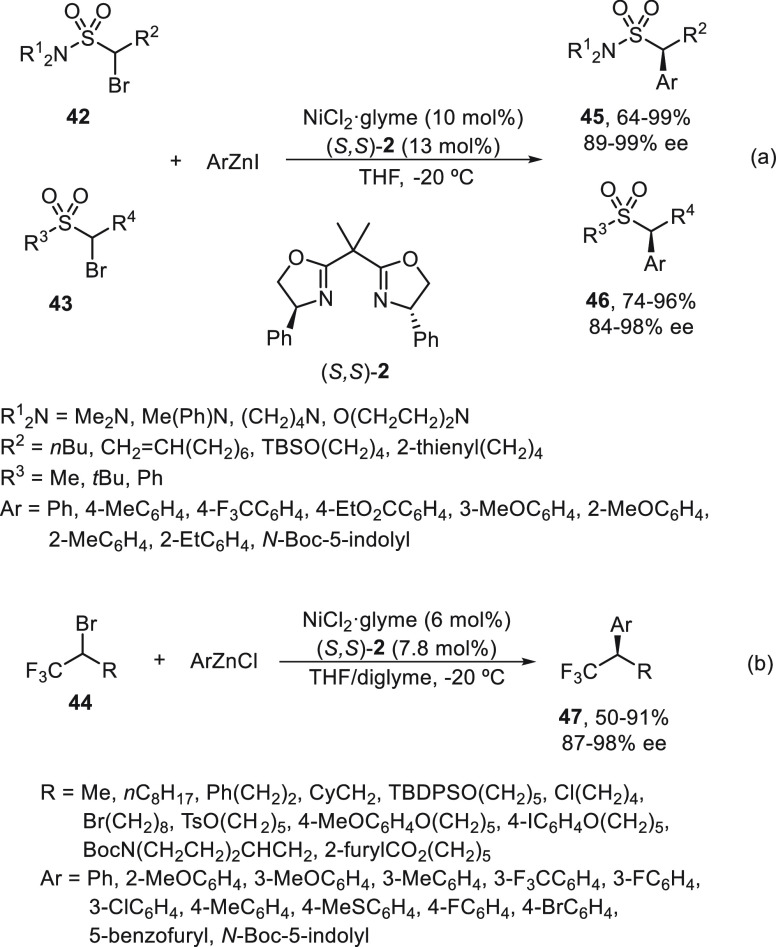

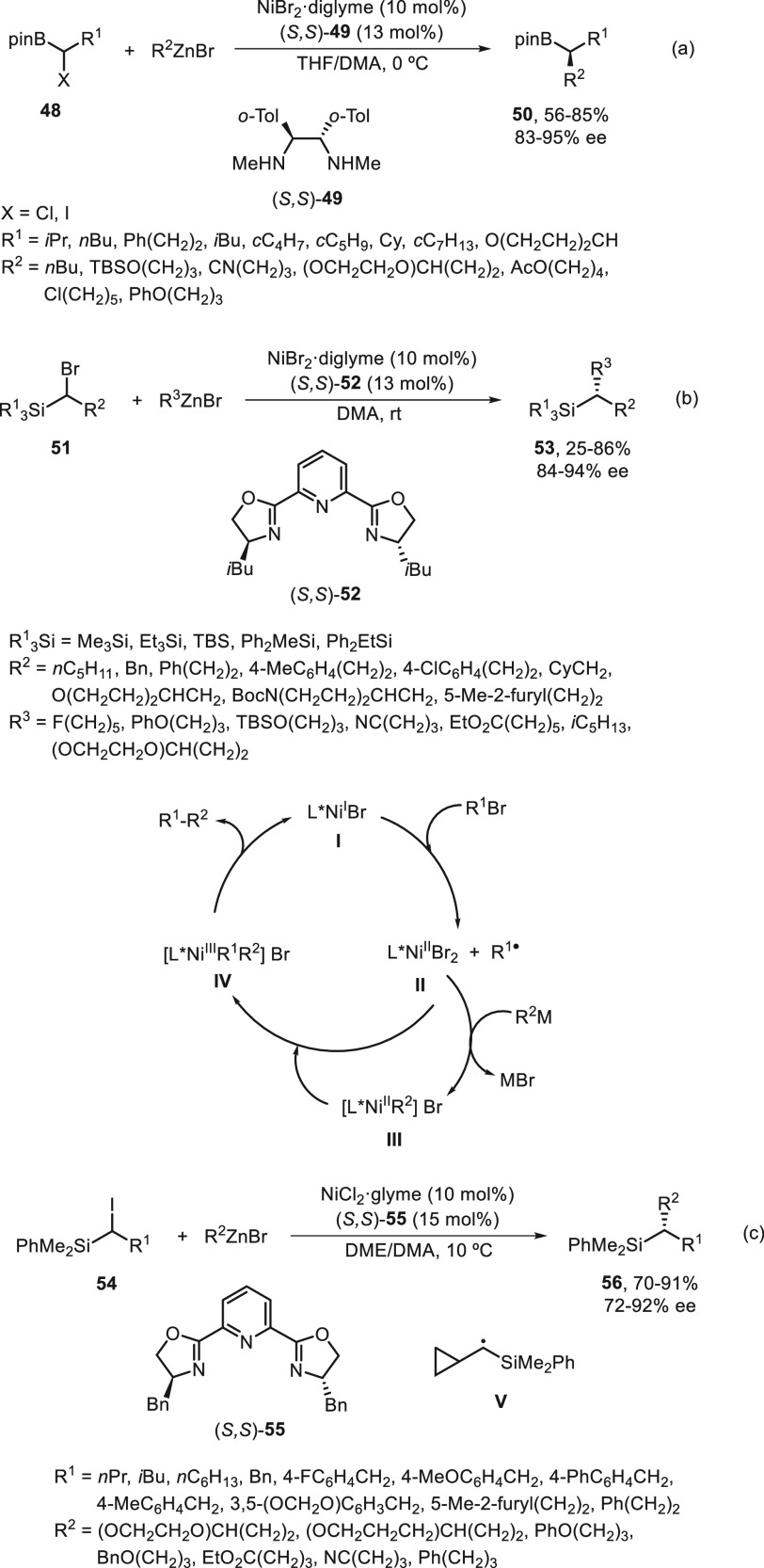

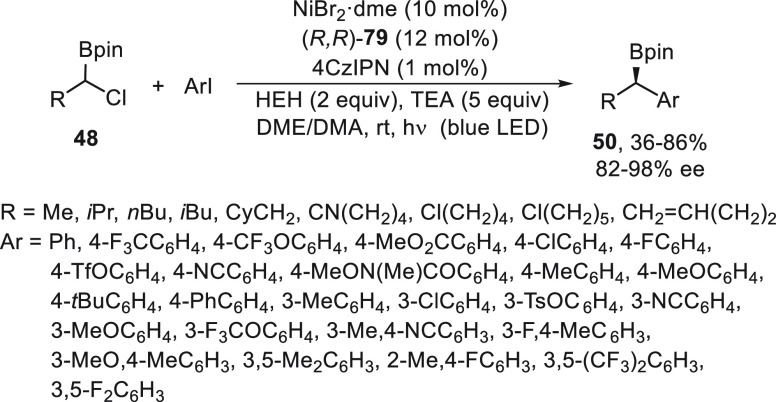

Enantioconvergent substitution reactions of α-haloboronates56 and α-halosilanes57 with alkylzinc reagents catalyzed by nickel have been carried out by Fu and co-workers. Enantioenriched alkylboronate esters are powerful building blocks in synthesis because of the facile transformation of C–B bonds into C–heteroatom bonds in a stereospecific manner. Using racemic α-haloboronates 48, enantioconvergent alkylation with alkylzinc reagents took place under NiBr2·diglyme/(S,S)-diamine 49 catalysis to furnish enantioenriched alkylboronates 50 (Scheme 10a).56 This alkyl–alkyl cross-coupling was carried out under mild reaction conditions THF/DMA at 0 °C and was compatible with different functional groups working with good yields and enantioselectivities. Several transformations to other families of enantioenriched compounds by C–C, C–N, C–halogen, and C–O bond formation were performed with little or no erosion in enantiomeric excess. Because of the synthetic interest of enantioenriched silanes, especially in medicinal chemistry,58−60 Matier, Fu, and Schwarzwalder57 studied the enantioconvergent cross-coupling of α-bromosilanes 51 with alkylzinc reagents in the presence of NiBr2·diglyme/bis(oxazoline) 52 (Scheme 10b). This alkylation proceeded at room temperature in DMA to give enantioenriched organosilanes 53 in moderate to good yields and up to 94% ee. Experiments with an enantioenriched α-bromosilane indicate that racemization occurred under the standard conditions, thereby confirming that the C–Br cleavage is reversible in discarding a DKR. In the proposed mechanism based on ESI-MS analysis and EPR spectrum, the Ni complex III is the predominant resting state during the catalytic cycle in which intermediates I–IV are involved. A consecutive publication of Oestreich and co-workers61 about the enantioconvergent alkylation of racemic α-iodosilanes 54 with alkylzinc bromides used similar reaction conditions (Scheme 10c). In this case, NiCl2/(S,S)-BnPyBox (55) was used as catalyst in a 5:2 mixture of DME/DMA at 10 °C to form the enantioenriched silanes 56 in high yield and slightly lower enantioselectivity. Control experiments with R1 = cyclopropyl revealed a radical clock mechanism supporting the intermediacy of a silicon-stabilized radical V.

Scheme 10. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of α-Haloboronates 48 and α-Halosilanes 51 and 54 with Alkylzinc Bromides.

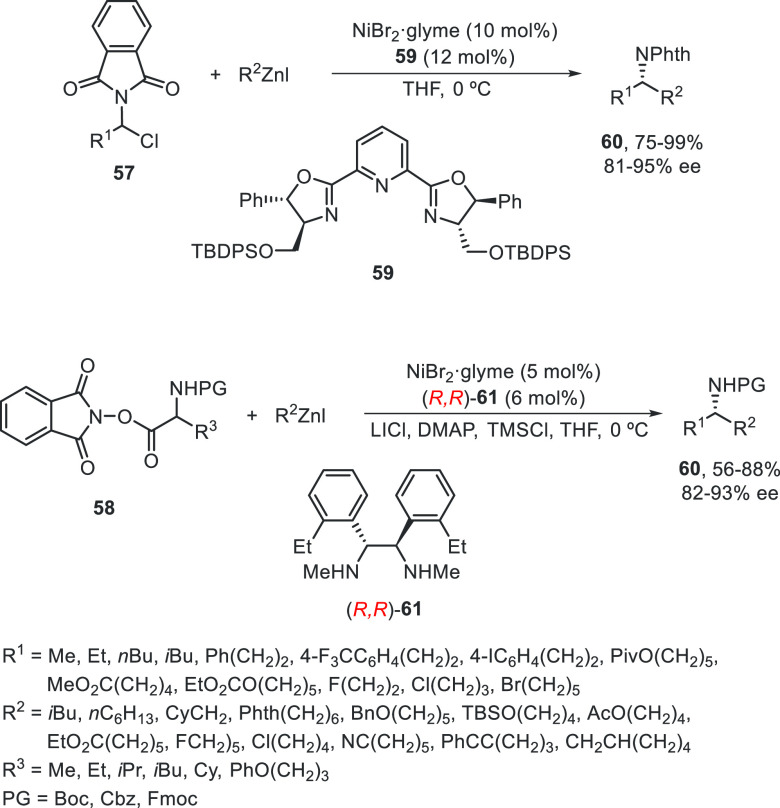

Enantioconvergent synthesis of amines has been achieved by Fu and co-workers using α-phthalimido alkyl chlorides 57 or N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHP) esters 58 of protected α-amino acids as electrophiles.62 Primary amines protected as phthalimides 57 reacted with alkylzinc iodides using NiBr2/bis(oxazoline) 59 as catalyst to provide protected dialkyl carbinamines 60 in good yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 11). In the case of redox-active NHP esters 58, a decarboxylative coupling with alkylzinc iodides takes place in the presence of NiBr2/diamine 61 as catalyst to afford N-protected dialkyl carbinamines 60 in good yields and enantioselectivities.

Scheme 11. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reaction of α-Phthalimido Alkyl Chlorides 57 or N-Hydroxyphthalimide Esters 58 of Protected α-Amino Acids with Alkylzinc Iodides.

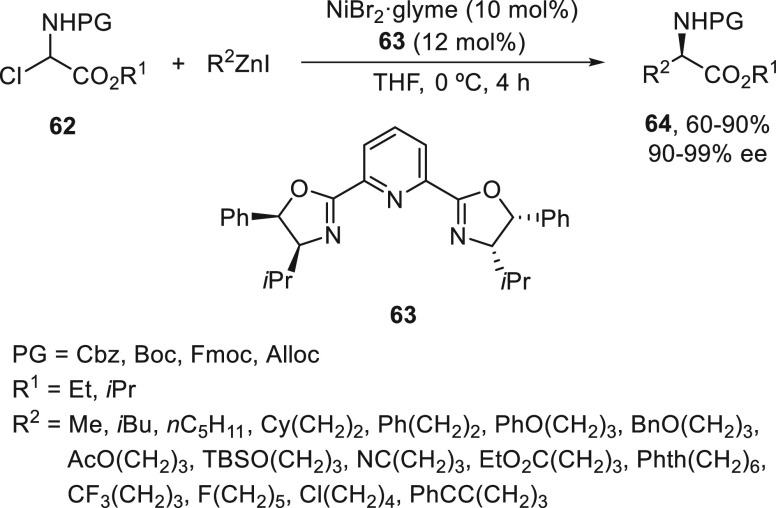

Recently, Fu and co-workers63 applied the Ni-catalyzed enantioconvergent Negishi reaction to the synthesis of α-amino acids. Starting from N-protected α-chloro glycinates 62,64 the alkylation with alkylzinc iodides (1:1.1 molar ratio) using NiBr2·glyme/bis(oxazoline) 63 as catalyst in THF at 0 °C furnished protected α-amino acids 64 in good yields (60–90%) and excellent enantioselectivities (up to 99%) (Scheme 12). These couplings were achieved under mild reaction conditions and are tolerant of air, moisture, and a wide variety of functional groups, and have been applied to the synthesis of intermediates en route to bioactive compounds in gram scale.

Scheme 12. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of α-Chloro Glycinates 62 with Alkylzinc Iodides.

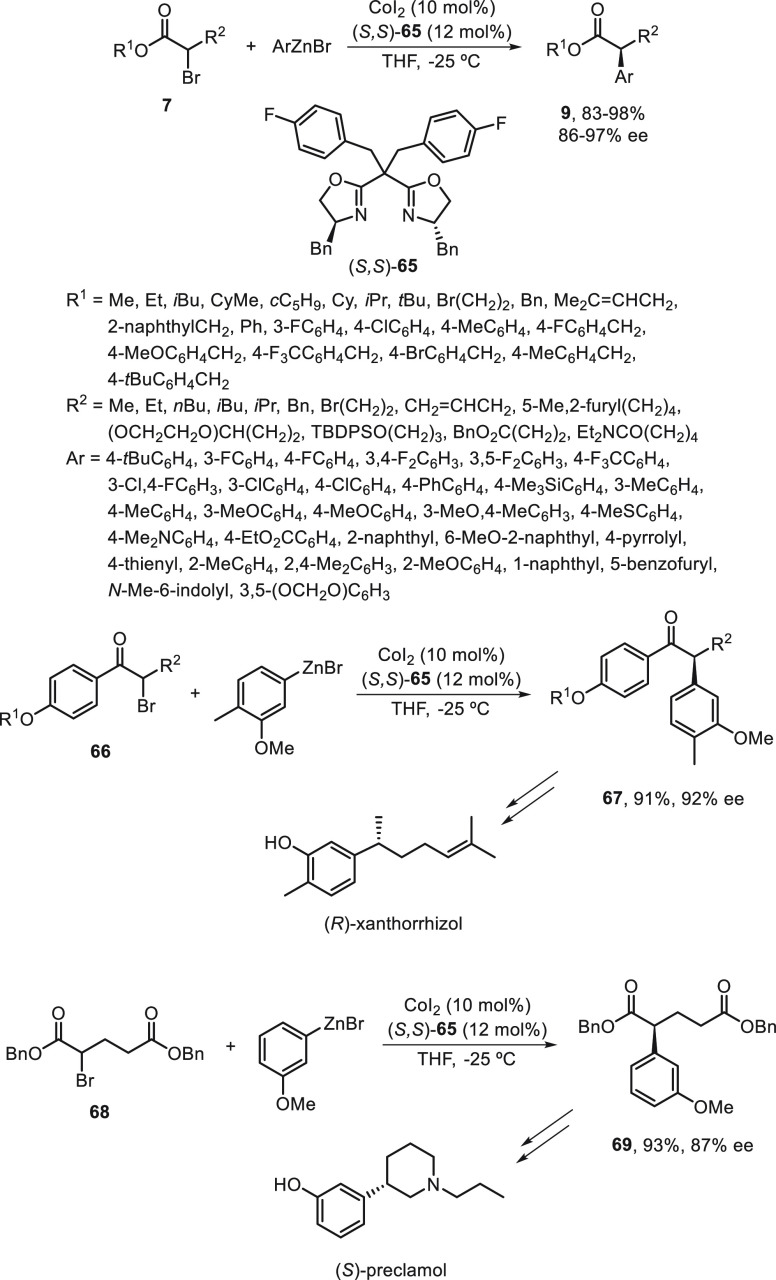

Cobalt-catalyzed enantioconvergent cross-couplings of racemic α-bromo esters 7 with arylzinc reagents, previously described with arylmagnesium reagents (Scheme 2),38 have been performed by Bian and co-workers.65,66 Differently substituted α-bromo esters 7 reacted with arylzinc bromides using CoI2/bis(oxazoline) (S,S)-65 as chiral catalyst in THF at 25 °C to provide compounds 9 in very good yields and ee (Scheme 13). They used radical probes 7 bearing a cyclopropyl and 4-pent-en-1-yl substituents to demonstrate the radical pathway of this Co-catalyzed Negishi reaction. This process was applied in gram scale to the synthesis of the sesquiterpene (R)-xanthorrhizol isolated from Curcuma xanthorrhiza Roxb. rhizome, which has anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and antiestrogenic properties. In this case, the reaction of ester 66 with 4-methyl-3-methoxyphenylzinc bromide gave ester 67 with 91% yield and 92% ee, which is the key precursor of (R)-xanthorrizol. The same group has performed the enantioselective synthesis of (S)-predamol, a central dopamine receptor agonist via a Co-catalyzed enantioconvergent Negishi reaction (Scheme 13).66 The α-bromo ester 68 was allowed to react with 3-methoxyphenylzinc bromide under the previously described reaction conditions to provide 69, a key precursor of (S)-preclamol.

Scheme 13. Enantioconvergent Co-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of α-Bromo Esters 7 with Arylzinc Bromides.

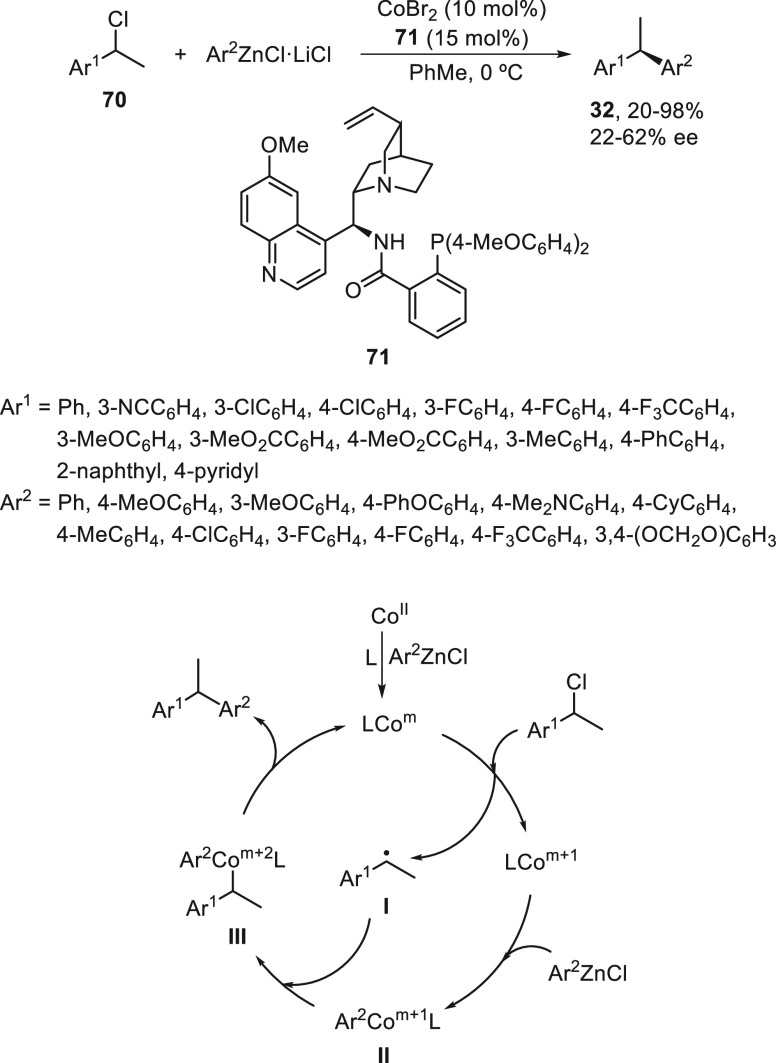

A Negishi C(sp3)–C(sp2) cross-coupling of racemic benzyl chlorides 70 with arylzinc reagents has been carried out under Co catalysis by Gu, Liu, and co-workers.67 In this case, a chiral monodentate anionic ligand 71 and CoBr2 were used as catalysts in toluene at 0 °C to give 1,1-diarylethanes 32 in up to 98% yield and moderate ee (Scheme 14). According to experimental studies, a radical mechanism has been proposed. The CoII is reduced by the arylzinc reagent to the active catalytic species LCoIII, which undergoes an electron-transfer reaction with the benzyl chloride to generate a benzylic radical I and the LCom+1 species. Subsequent transmetalation between the LCom+1 species and the arylzinc reagent provides complex II, which recombines with the benzyl radical I to deliver complex III. Final reductive elimination of III furnished the coupling product and regenerated the catalyst.

Scheme 14. Enantioconvergent Co-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of Benzyl Chlorides 70 with Arylzinc Reagents.

As a summary of this Section 2.1.2, nickel-catalyzed enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions allow the C–C bond formation between activated secondary alkyl electrophiles and alkyl or arylzinc reagents to form enantioenriched compounds mainly using mono- and bis(oxazolines) as chiral ligands. In some cases, this Negishi reaction can be also performed under cobalt catalysis. The most favorable mechanism involves the formation of an alkyl radical, which reacts with the chiral organonickel or cobalt intermediates through an out-of-cage pathway to afford the coupling product by final reductive elimination.

2.1.3. Organoboron Reagents

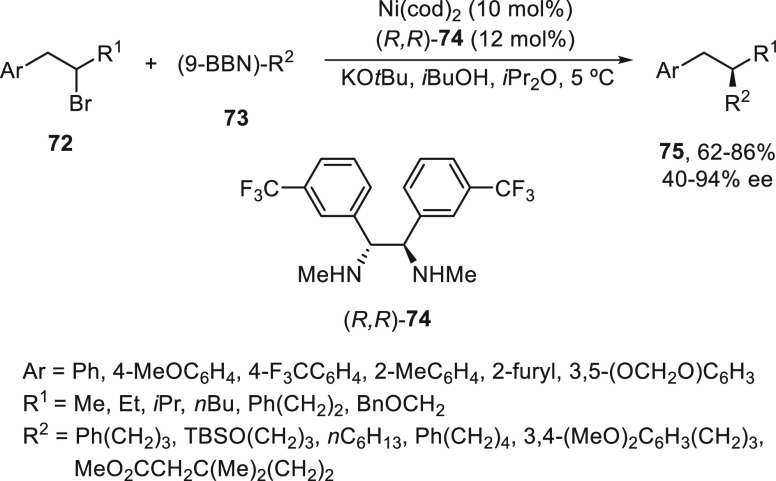

Nickel-catalyzed Suzuki cross-couplings of alkyl halides and alkylboronic acids were first described by Zhou and Fu.68 On the basis of the cross-coupling of unactivated alkyl halides with alkylboranes using trans-N,N′-dimethyl-1,2-cyclohexanediamine,69 Saito and Fu70 performed an enantioconvergent version of this alkyl–alkyl Suzuki reaction using a chiral diamine as ligand. Homobenzylic bromides 72 reacted with alkyl-(9-BBN) 73 using Ni(cod)2/(R,R)-74 as catalyst to give products 75 in good yields (up to 86%) and ee (up to 94%) (Scheme 15). This method was applied to the arylation of racemic α-chloro- and α-bromo amides in which a modest kinetic resolution of the α-chloro amide was observed.71

Scheme 15. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of Homobenzylic Bromides 72 with Alkylboranes 73.

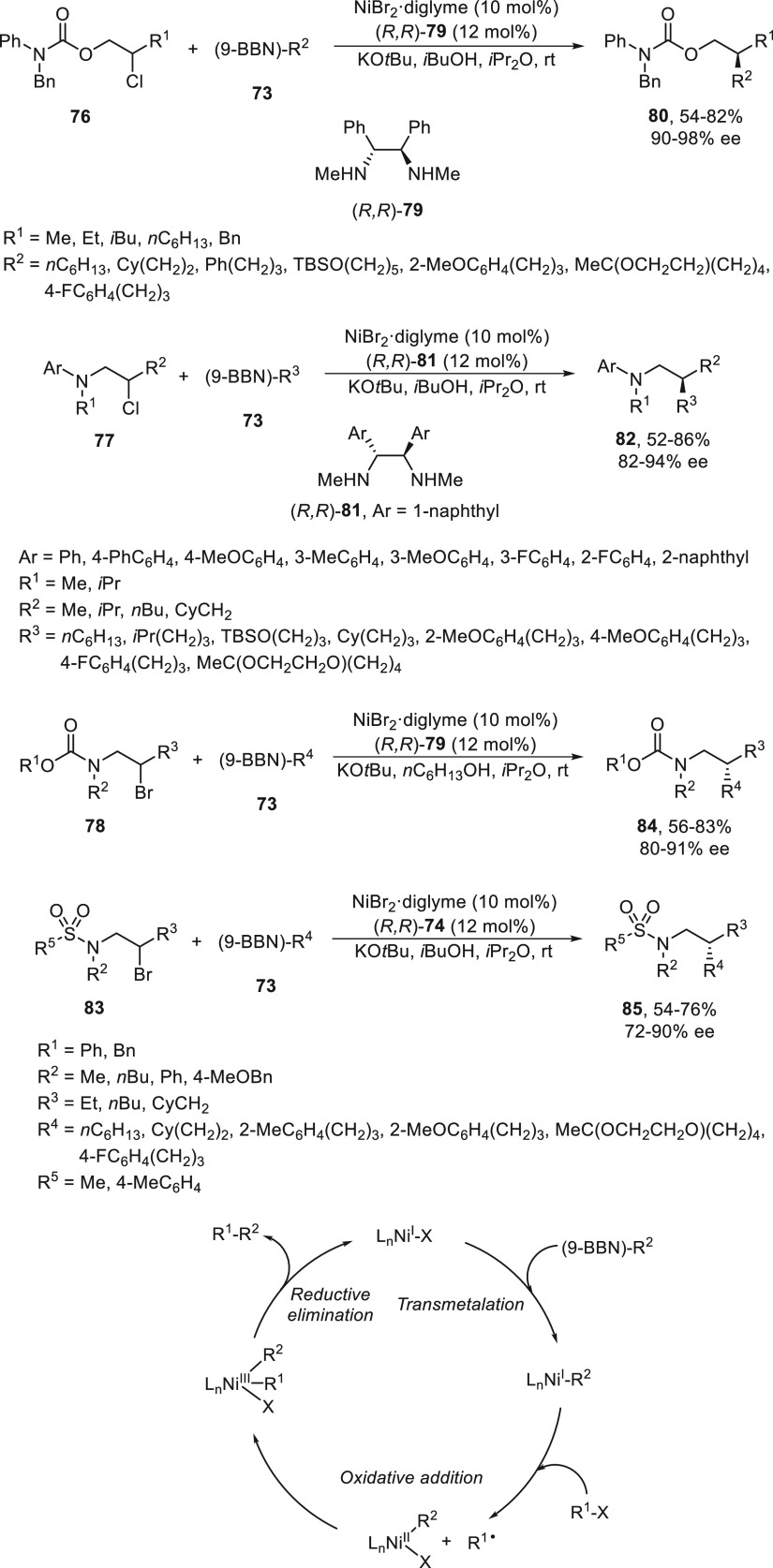

Subsequent studies on enantioconvergent alkyl–alkyl Suzuki reactions by Fu and co-workers were performed with acylated halohydrins 76,72 β-halo alkylanilines 77,73 and N-protected β-bromo alkylamines 78(74) (Scheme 16). In all these cases, the presence of a directing group, which likely interacts with the chiral catalyst, is essential for the high enantioselectivity observed with these unactivated secondary alkyl halides. Acylated halohydrins 76 and alkylboranes 73 reacted in the presence of NiBr2/diamine (R,R)-79 as catalyst, which provided products 80 in up to 82% yield and high enantioselectivity (90–98% ee).72 β-Chloro alkylanilines 77 reacted with boranes 73 using NiBr2/diamine 81 as catalyst to give enantioenriched β-alkylanilines 82 up to 86% yield and up to 94% ee.73 In the case of N-protected β-bromo alkylamines 78 or 83 bearing a carbonate or a sulfonamide group, respectively, the alkylation with boranes 73 was performed with NiBr2 and diamine 79 or 74 as chiral ligands to furnish products 84 or 85, respectively. Experimental evidence showed that the alkyl group of the organoborane is transferred to the reaction product with retention of the configuration consistent with transmetalation with retention. Therefore, the structural integrity for the Ni–R2 bond is maintained during the catalytic cycle depicted in Scheme 16.

Scheme 16. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of β-Halogenated Compounds: Reaction of Acylated Halohydrins 76, β-Chloro Alkylanilines 77, and N-Protected β-Bromoalkylamines 78 and 83 with Alkylboranes 73.

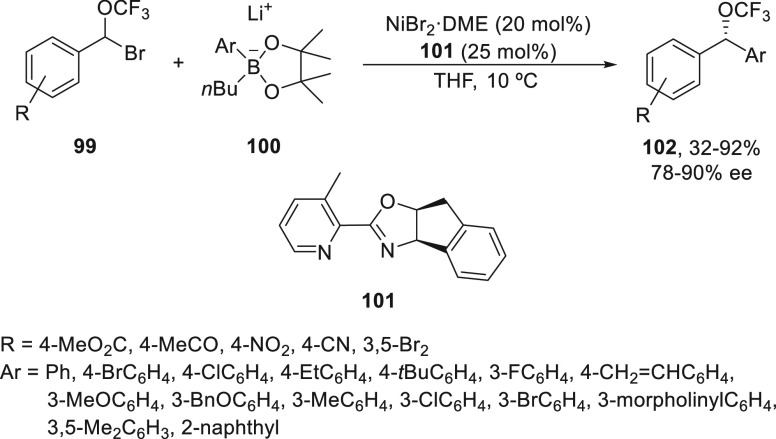

The sulfone group directed the Ni-catalyzed Suzuki reaction at the γ-position of sulfonamide 86 and sulfones 87 under the reaction conditions indicated for sulfonamides 83 (Scheme 16).74 This enantioconvergent γ-alkylation took place with γ-halo carboxamides 88 using NiBr2/diamine (R,R)-79 as catalyst.75 In the case of sulfonamide 86, product 89 was obtained in 78% yield and 85% ee, and sulfones 87 provided compounds 90 in 75–84% yields and 87–90% ee (Scheme 17).74 Carboxamides 88 bearing a bromo or chloro substituents at the γ-position afforded, by reaction with boranes 73, the corresponding cross-coupling products 91 in good yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 17).75

Scheme 17. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of γ-Halogenated Sulfonamide 86, Sulfones 87, and Carboxamides 88 with Alkylboranes 73.

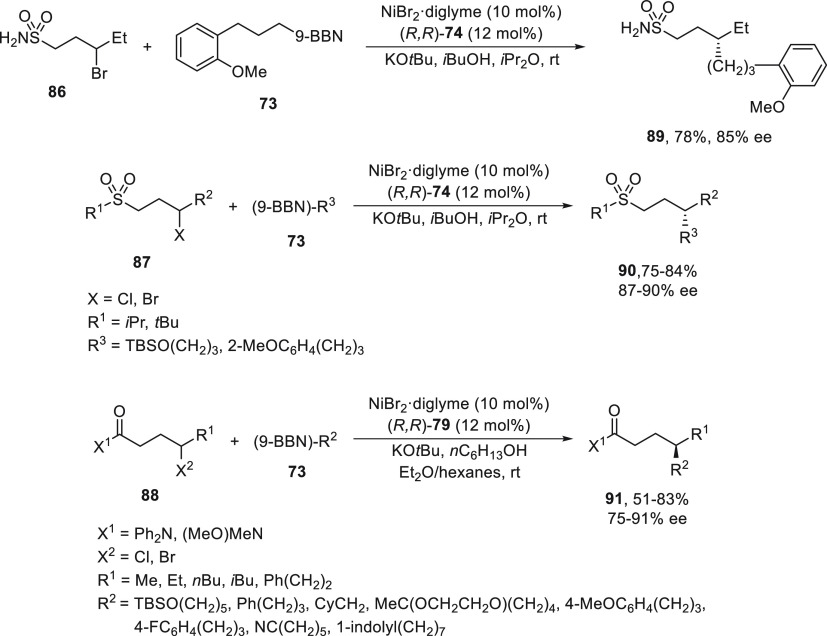

Gandelman and co-workers76,77 described the enantioconvergent synthesis of secondary alkyl fluorides by Suzuki cross-coupling of 1-fluoro-1-haloalkanes with alkylboranes 73. 1-Bromo-1-fluoro-2-arylethanes 92 were alkylated using NiCl2/diamine 93 as catalyst to give products 94 up to 81% yield and up to 99% ee (Scheme 18). Under these reaction conditions, fluorobromoalkanes bearing different directing groups, such as ketones 95, provided chiral δ- and ε-fluoroalkanes 96 after alkylation. 1-Bromo-1-fluoroalkanes bearing a sulfonamide-directing group 97 gave γ-fluorosulfonamides 98 after enantioconvergent cross-coupling with alkylboranes 73 with modest yield and up to 91% ee.

Scheme 18. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of 1-Halo-1-fluoroalkanes 92, 95, and 97 with Alkylboranes 73.

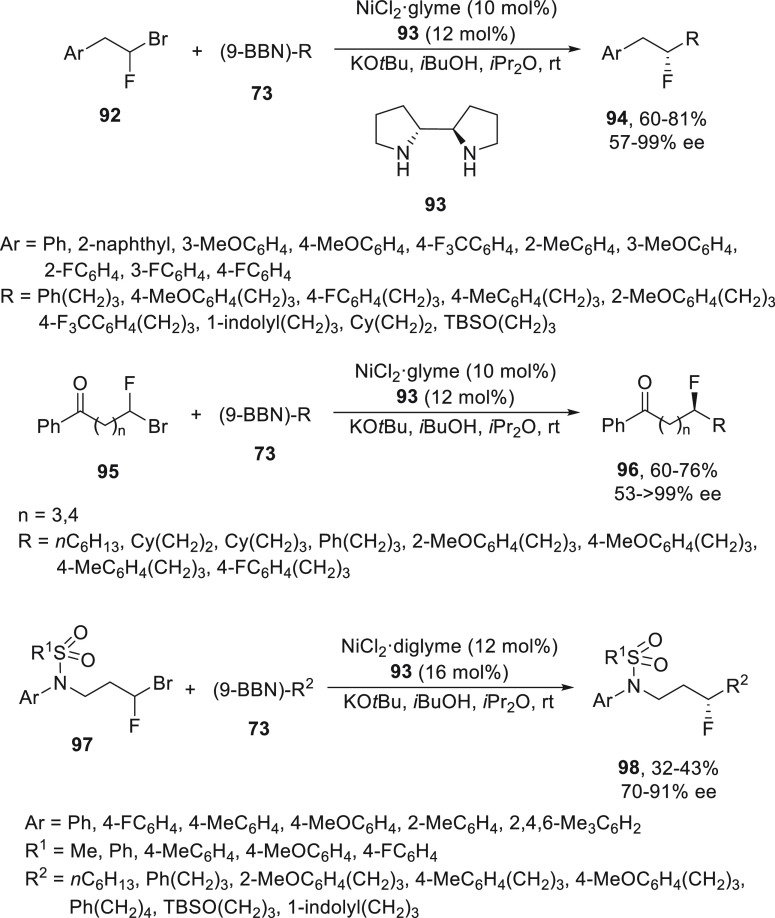

Starting from racemic α-bromobenzyl trifluoromethyl ethers 99, Shen and co-workers78 performed the enantioconvergent cross-coupling with aryl pinacol boronates 100 to form α-trifluoromethoxy-substituted diaryl methanes 102 (Scheme 19). The reaction took place under mild reaction conditions using NiBr2/oxazoline 101 as catalyst to afford products 102 with good yields and up to 90% ee. However, other organometals, such as phenylmagnesium bromide or diphenylzinc, gave compounds 102 with lower yields due to the side reactions of these Lewis acidic organometals with products 102. Several functional groups are tolerated under these reaction conditions, and the reaction can be easily scaled up to grams.

Scheme 19. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of α-Bromobenzyl Trifluoromethyl Ethers 99 with Aryl Pinacol Boronates 100.

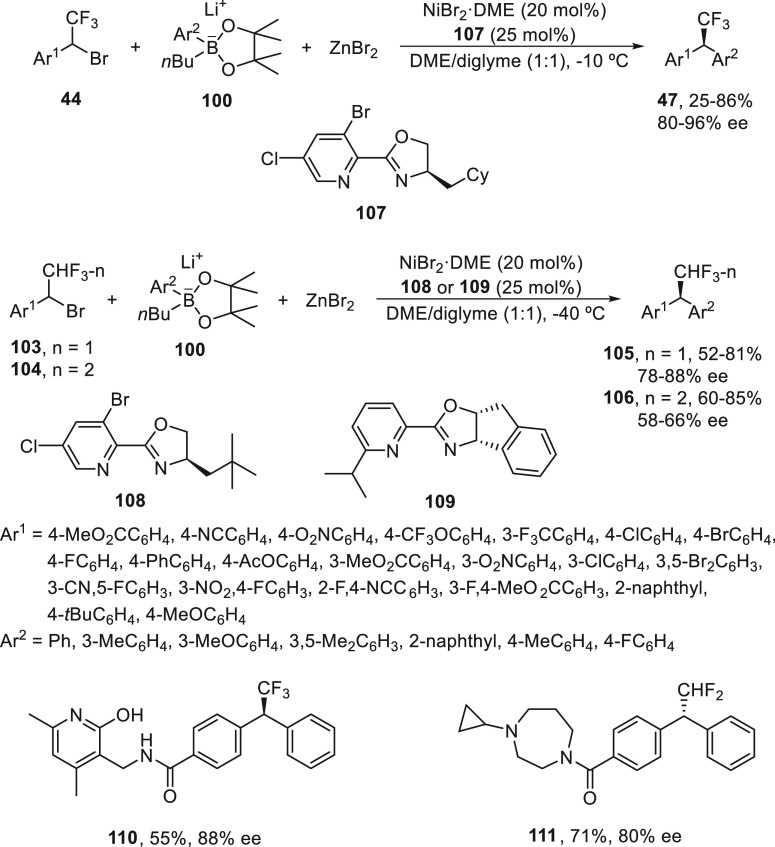

The same group79 has developed an enantioconvergent acylation of secondary α-bromobenzyl trifluoro-/difluoro-/monofluoromethanes 44/103/104 with dilithium aryl zincates, [Ar2ZnBr]Li, generated in situ from lithium organoborates 100 and ZnBr2 (Scheme 20). The use of lithium aryl zincates facilitates the transmetalation step of this nickel-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction, thereby allowing the synthesis of enantioenriched benzhydryl fluoroalkene derivatives 47, 105, and 106 using NiBr2·DME and a pyridine-oxazoline ligand 107 for trifluoromethyl substrates 44, 108 for difluoromethyl compounds 103, and ligand 109 for fluoromethyl reagents. This procedure was applied to the synthesis of 110, a trifluoromethylated mimic of an inhibitor for the histone lysine methyltransferase enhancer of zeste homologue 2 (EZH2)80 in 55% overall yield and with 88% ee. A difluoromethylated compound 111, which is a mimic of histamine H3 receptor,81 was prepared in 71% overall yield and with 80% ee.

Scheme 20. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Arylation of Fluorinated Benzylic Bromides 44, 103, and 104 with Lithium Organoboronates 100 and ZnBr2.

For the cross-coupling of fluorinated secondary benzyl bromides 112, Shen and co-workers82 also employed in situ generated lithium aryl zincates but under cobalt catalysis. In this case, CoBr2·DME and bis(oxazoline) (S,S)-113 were used as chiral catalysts under mild reaction conditions to provide fluorinated diarylmethane derivatives 114 in up to 92% ee (Scheme 21). This methodology was applied to the synthesis of compounds 115 and 116, which are fluorinated mimics of EZH2,80 respectively. Compound 117, a key intermediate of a fluorine-substituted analogue of Lilly’s mGlu 2 receptor potentiators, which is a compound for the treatment of migraine headaches,83 was prepared in 84% yield with 84% ee.

Scheme 21. Enantioconvergent Co-Catalyzed Arylation of Fluorinated Secondary Benzyl Bromides 112 with Lithium Aryl n-Butyl Pinacol Boronates 100 and ZnBr2.

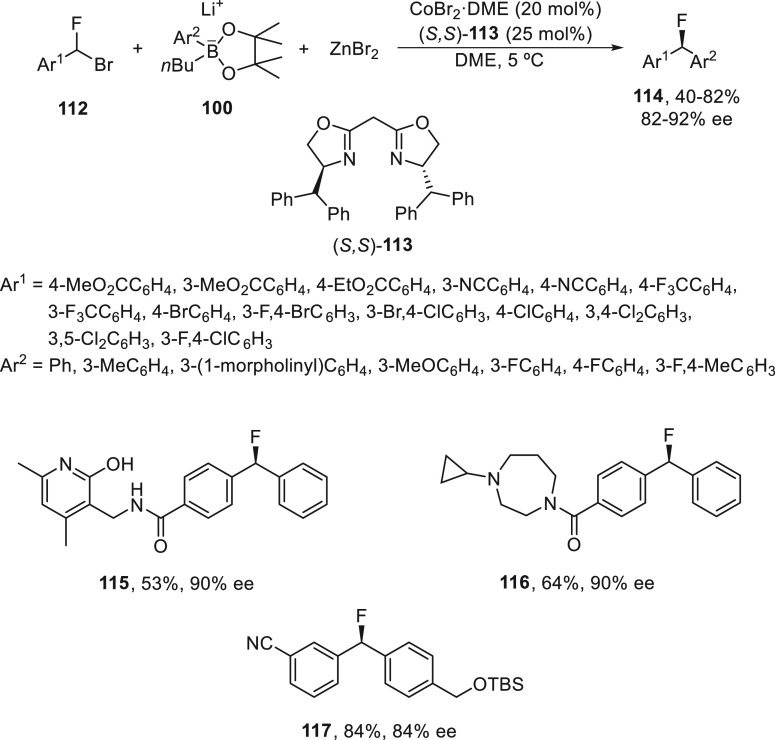

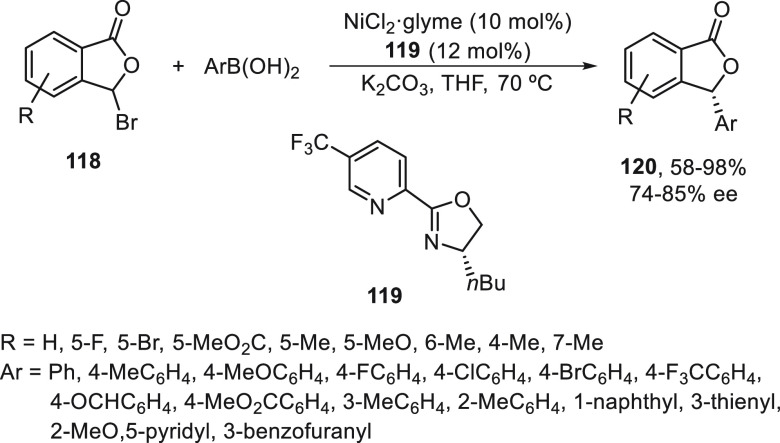

Enantioconvergent Suzuki reactions of 3-bromophthalides 118 with arylboronic acids was recently reported by Zhang, Feng, and co-workers.84 Cross-coupling with arylboronic acids took place using NiCl2/oxazoline 119 as catalyst and K2CO3 as base in THF at 70 °C to give chiral 3-arylphthalides 120 with good yields and up to 85% ee (Scheme 22).

Scheme 22. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction of 2-Bromophthalides 118 with Arylboronic Acids.

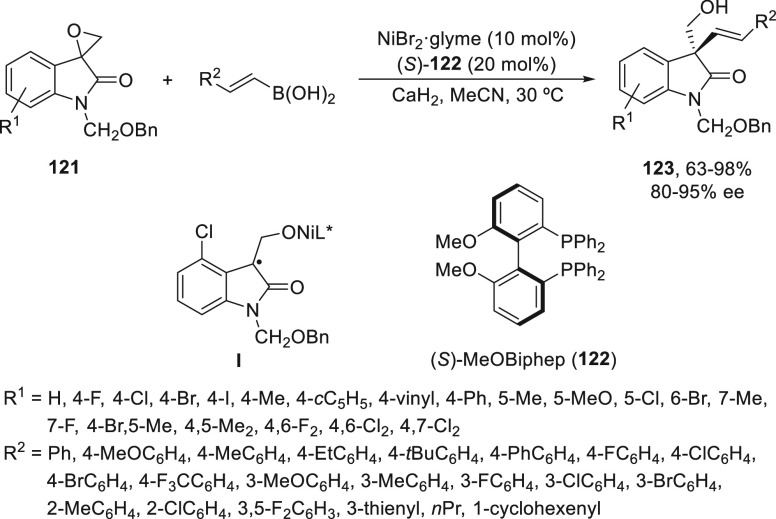

In general, the alkyl electrophiles of these Suzuki reactions are secondary, which give rise to chiral tertiary carbon stereocenters. Recently, Zhang and co-workers85 reported a Ni-catalyzed enantioconvergent coupling of epoxides 121 with alkenylboronic acids. These racemic spiroepoxyindoles 121 afforded chiral oxindoles 123 bearing quaternary carbon stereocenters using NiBr2/(S)-MeOBiphen (122) as catalyst (Scheme 23). In this case, CaH2 was used as base, and MeCN was used as solvent at 30 °C to give products 123 with good yields and enantioselectivities. It has been proposed that the formation of a stabilized tertiary radical intermediate I by a single-electron transfer mechanism is formed during the oxidative addition step.

Scheme 23. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of Spiroepoxyindoles 121 with Alkenylboronic Acids.

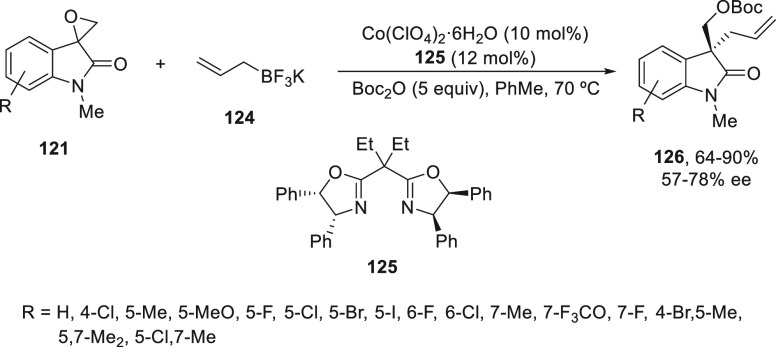

The same group performed this ring-opening reaction of spiroepoxyindoles 121 with allylboron reagents under Co(II) catalysis.86 Potassium allyltrifluoroborate (124) reacted with epoxides 121 using Co(ClO4)2/bis(oxazoline) 125 in the presence of di-tert-butyl dicarbonate (Boc2O) in order to avoid the coordination of the alcohol from the ring-opening product with the chiral catalyst. Chiral oxindoles 126 were obtained with yields of 64–90% and up to 78% ee (Scheme 24).

Scheme 24. Enantioconvergent Co-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of Spiroepoxyoxindoles 121 with Potassium Allyltrifluoroborate 124.

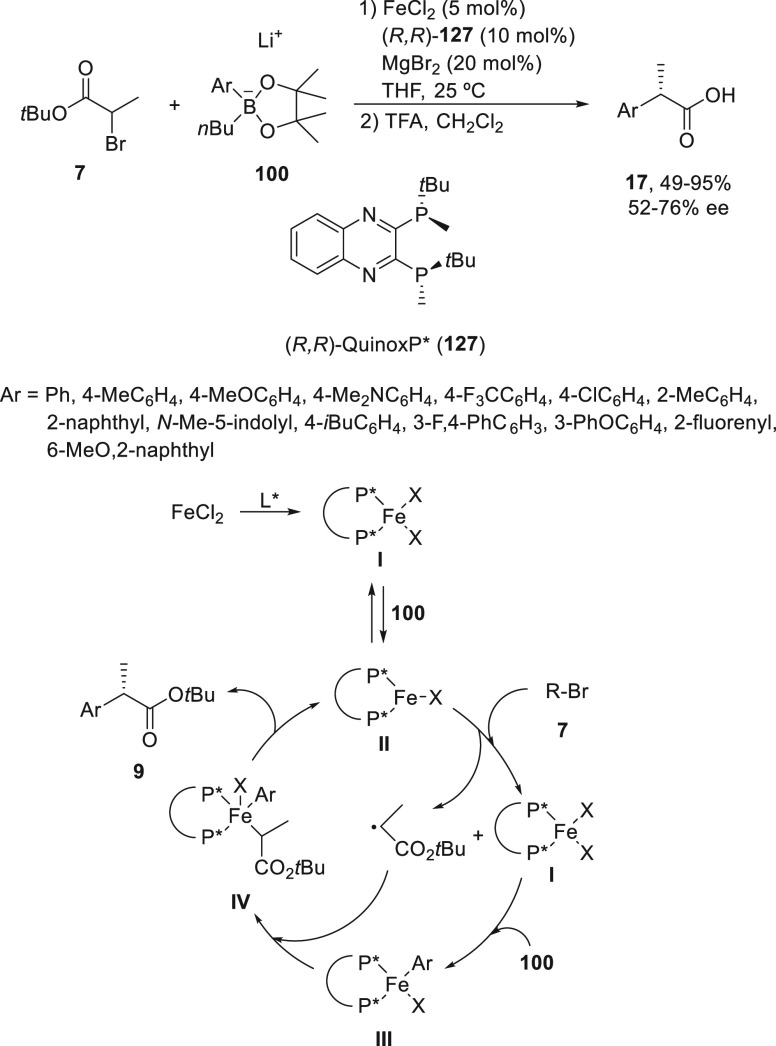

Nakamura and co-workers87 have described the enantioconvergent iron-catalyzed Suzuki reaction of tert-butyl α-bromopropionates 7, which was previously described with Grignard reagents43 (Scheme 4). In this case, lithium aryl pinacol boronates 100 were used as coupling partners, and FeCl2/(R,R)-QuinoxP* (127) was used as catalyst to provide, after TFA hydrolysis of the corresponding esters 9, enantioenriched α-arylpropionic acids 17 with good yields and moderate enantioselectivities (Scheme 25). As mentioned before, α-arylpropionic acids are well-known nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). A plausible mechanism based on experimental and theoretical studies is depicted in Scheme 25. Transmetalation of complex I (LFeCl2) with the boron reagent and subsequent reductive elimination gave the active species II. This intermediate abstracts the bromine atom from compound 7 to generate the corresponding alkyl radical, which recombines with complex III generated by transmetalation of I with the boron reagent 100 to produce intermediate IV. Final reductive elimination of complex IV affords the expected product.

Scheme 25. Enantioconvergent Fe-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction of t-Butyl α-Bromopropionate 7 with Lithium Aryl Pinacol Boronates 100.

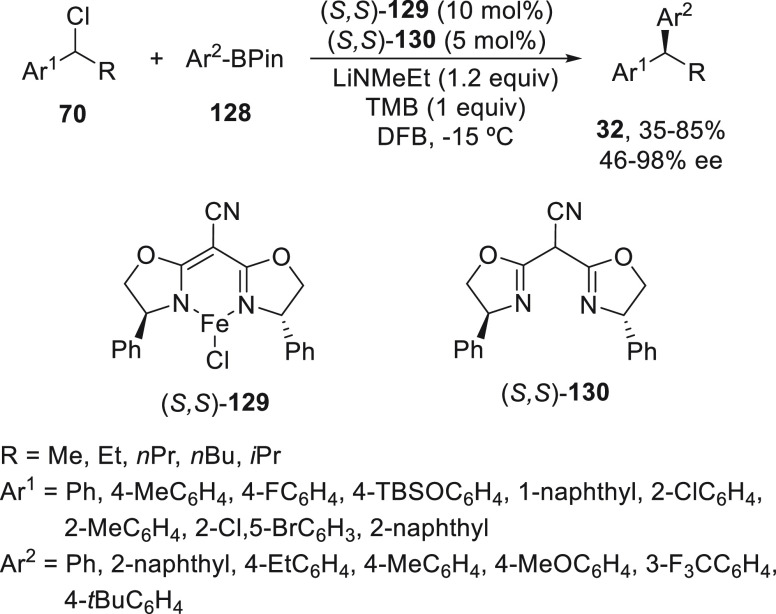

Enantioenriched 1,1-diarylalkanes 32 have been prepared by enantioconvergent Suzuki reaction of benzylic chlorides 70 with arylboronic pinacol esters 128 using cyano[bis(oxazoline)]iron(II) chloride complex 129 and the ligand 130 as catalyst (Scheme 26).88 This cross-coupling took place under mild reaction conditions in the presence of 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene (TMB) as a stoichiometric additive, LiNMeEt as base, and 1,2-difluorobenzene (DFB) as solvent at −15 °C. Products 32 were obtained with moderate to good yields and enantioselectivities.

Scheme 26. Enantioconvergent Iron-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of Benzylic Chlorides 70 with Arylboronic Pinacol Esters 128.

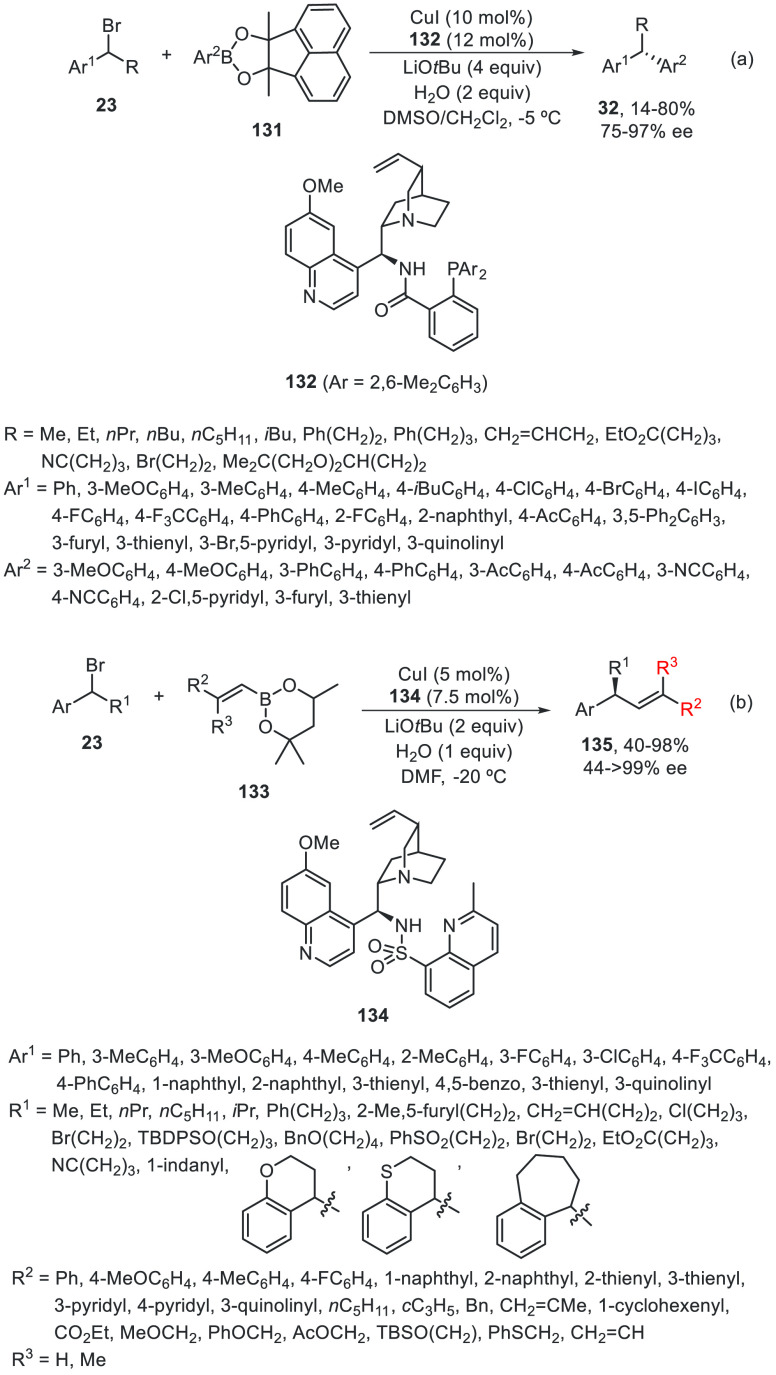

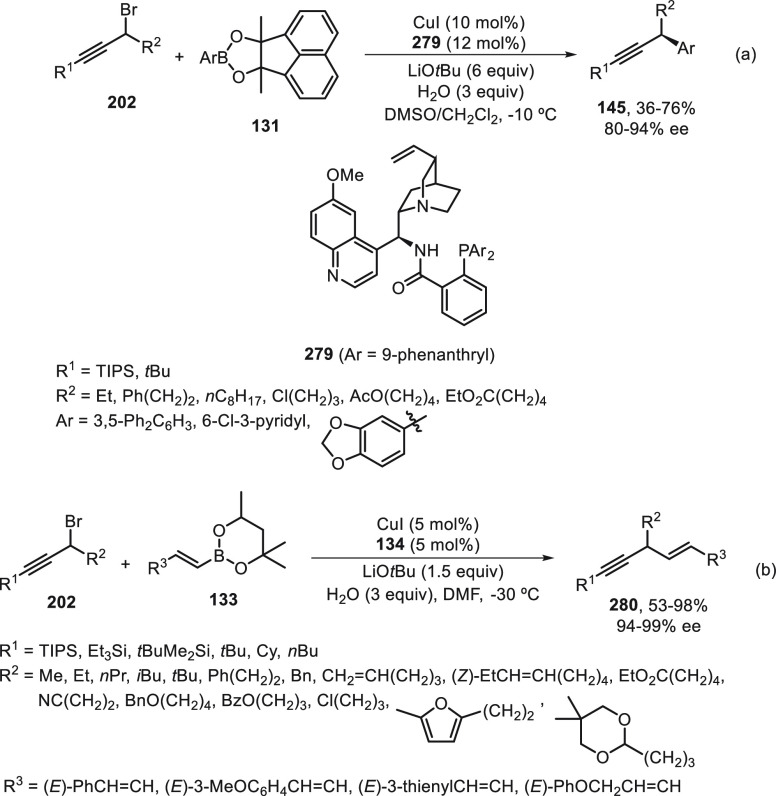

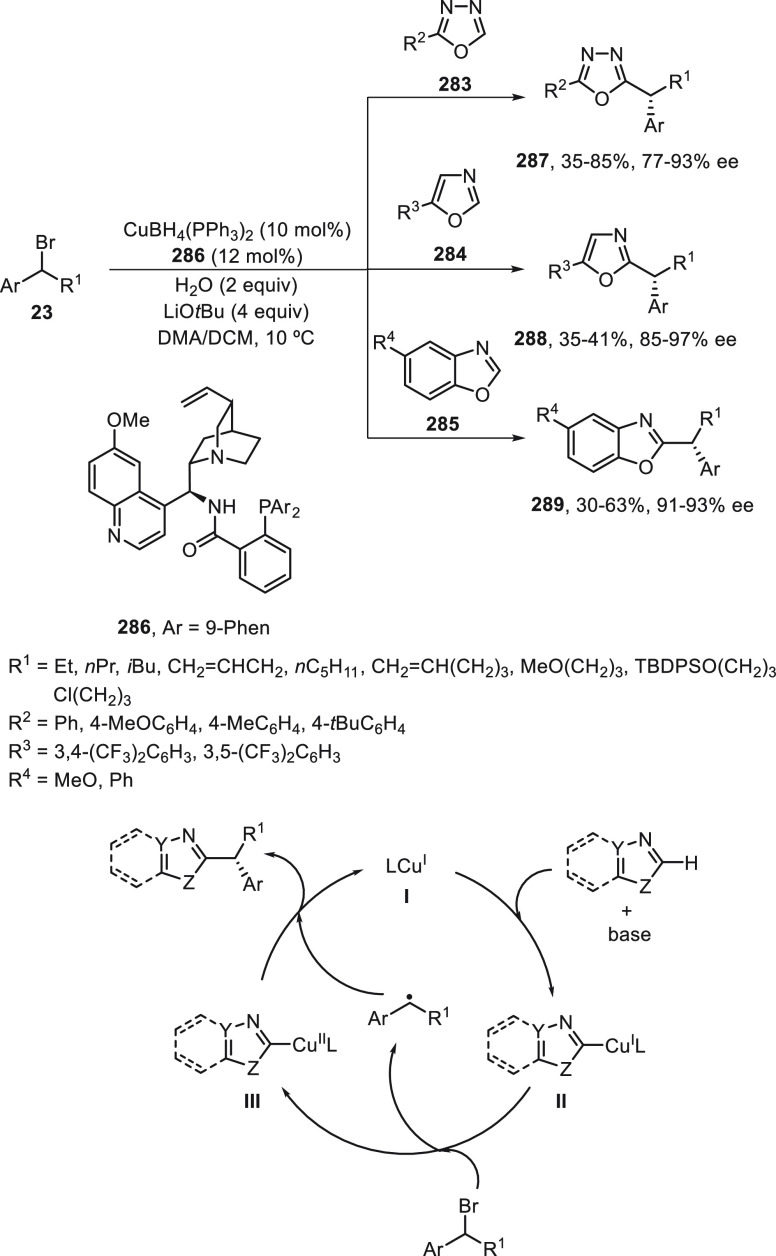

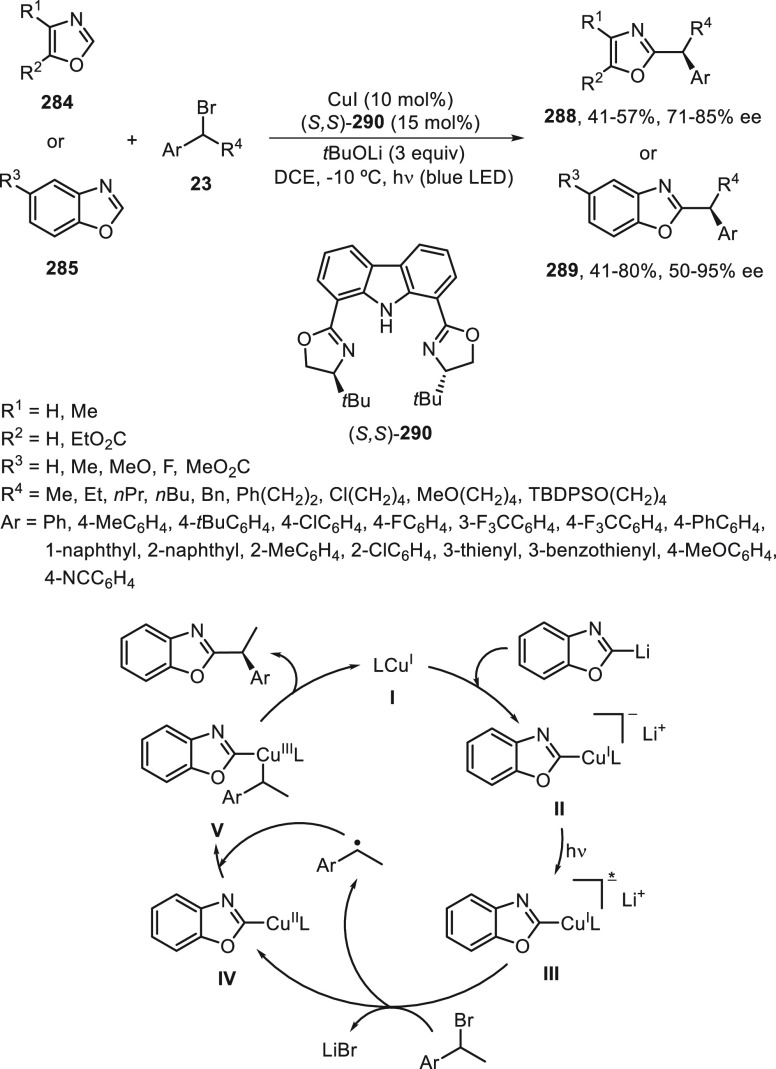

Li, Liu, and co-workers89,90 have developed the Cu-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical Suzuki C(sp3)–C(sp2) cross-coupling. Benzylic bromides 23 have been allowed to react with cyclic B(mac)-derived boronate esters 131 using CuI/N,N,P-ligand 132 as the catalyst to provide enantioenriched 1,1-diarylalkanes 32 in up to 80% yield and 97% ee (Scheme 27a).89 When alkenyl methylpentanediol(mp)-derived boronate esters 133 were used as organometals for the Suzuki cross-coupling with benzylic bromides, CuI/N,N,N-ligand 134 was the best catalyst and gave products 135 in up to 98% yield and up to >99% ee (Scheme 27b).90 In this hemilabile N,N,N-ligand 134, the presence of a methyl group at the ortho position of the sulfonamide quinoline moiety increases the enantioselectivity by steric hindrance probably by elongation of the Cu–N bond. These cross-couplings were also performed with propargyl bromides (see Section 4). Mechanistic studies revealed a radical process depicted in Scheme 27. The CuI complex undergoes a transmetalation process with the boronate ester to give intermediate I, which undergoes a single electron reduction with the benzylic bromide to deliver a radical II and the CuII complex III. Final reaction of these intermediates II and III forms the coupling product and regenerates the catalyst. In the case of alkenylboronates cross-coupling, DFT calculations supported tentatively the favorable transition state (TS) to explain the absolute configuration of the products.

Scheme 27. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of Benzylic Bromides 23 with Aryl and Alkenyl Boronates 131 and 133, Respectively.

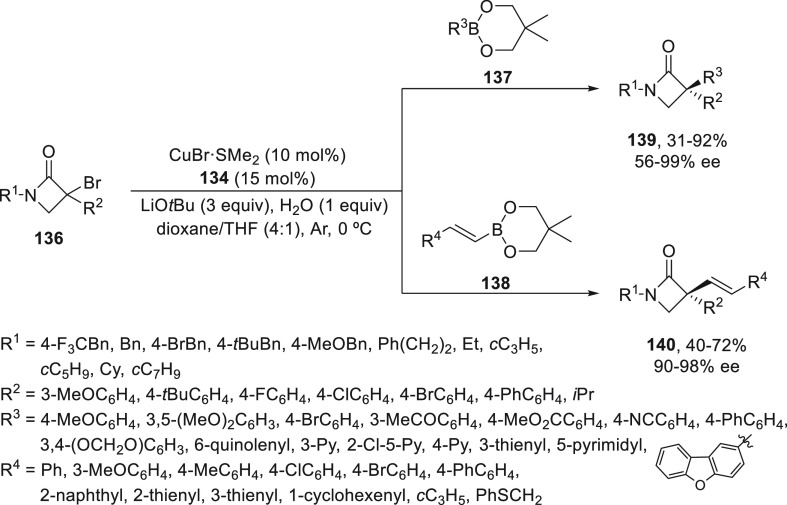

Recently, the same group91 performed a copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical C(sp3)–C(sp2) cross-coupling of α-bromo-β-lactams 136 with aryl and alkenyl organoboronate esters 137 and 138 (Scheme 28). In this case, the hemilabile N,N,N-ligand 134 gave products 139 and 140 with a quaternary stereocenter in up to 99% ee. The best results were obtained with neopentyl glycol (neop)-derived aryl-derived aryl and alkenyl boronate esters in the LiOtBu (3 equiv)/H2O (1 equiv) system at 0 °C under an argon atmosphere and using a 4/1 mixture of 1,4-dioxane/THF. Experimental radical trap experiments corroborate the formation of an alkyl radical, which is formed because of the enhanced reducing capability of the Cu(I) catalyst bearing this type of electron-donating ligand.

Scheme 28. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Suzuki Reaction of α-Bromo-β-lactams 136 with Aryl and Alkenyl Boronates 137 and 138, Respectively.

Alkyl organoboranes reacted with unactivated secondary alkyl bromides and chlorides bearing a directing group at the α- to ε-position under Ni/chiral diamines catalysis. Boronates and boronic acids have been used for C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond-forming reactions with oxazolines or diphosphines as chiral catalysts. Cobalt, iron, and copper complexes catalyzed the cross-coupling of epoxides and activated bromides with boronates. In all cases, enantioconvergent transformations take place under mild reaction conditions by intermediacy of a radical derived from the electrophile.

2.1.4. Organosilicon Reagents

An enantioconvergent nickel-catalyzed Hiyama cross-coupling reaction can be performed with activated 2,6-di-tert-butyl-4-methylphenyl (BHT) α-bromo esters 7 and organosilanes. Fu and co-workers92 reported this C(sp3)–C(sp2) bond formation using NiCl2/diamine (S,S)-79 as catalyst and aryl or alkenyltrimethoxysilanes to give esters 9 with good yields and up to 99% ee (Scheme 29). This Hiyama reaction took place at room temperature in dioxane promoted by tetrabutylammonium triphenyldifluorosilicate (TBAT) as fluoride activator.

Scheme 29. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Hiyama Reactions of α-Bromo Esters 7 with Aryl or Alkenylsiloxanes.

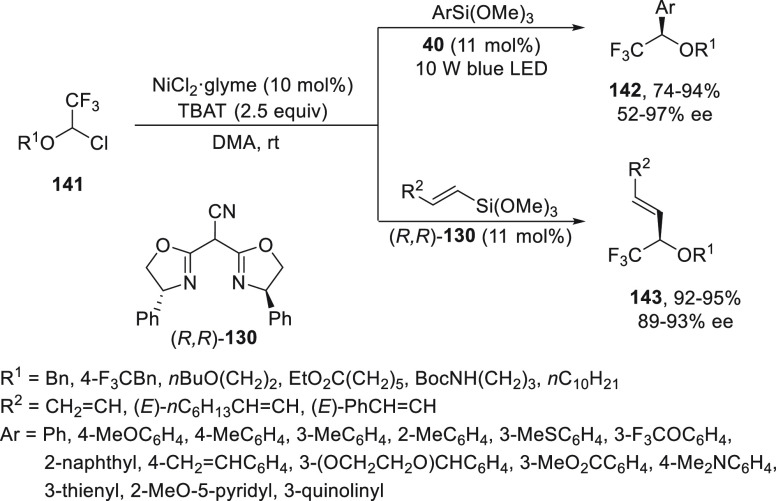

Varenikov and Gandelman93 applied the enantioconvergent Hiyama reaction for the synthesis of enantioenriched α-trifluoromethyl ethers 142 and 143, precursors of α-trifluoromethyl alcohols. Cross-couplings of different α-chloro-α-trifluoromethyl methyl ethers 141 with aryl siloxanes were performed under NiCl2/bis(oxazoline) 40 catalysis and irradiated in darkness with a white or blue LED lamp, which significantly accelerated the process, to provide compounds 142 with very good yields and up to 98% ee (Scheme 30). When alkenyl siloxanes were used as nucleophiles, bis(oxazoline) (R,R)-130 gave compounds 143 in up to 93% ee. The authors presume that the photoinduction facilitates the oxidative addition of electrophile 141 to an excited Ni(I) catalytic species, which likely takes place by radical mechanism, as has been proposed by Fu and co-workers.94 In the case of alkyl ethers, the arylation needed longer reaction times. Presumably, the oxidative addition is the rate-limiting step, and the lower the LUMO of the electrophile, the faster the single-electron transfer (SET) from the catalyst occurs.

Scheme 30. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Hiyama Reactions of α-Chloro-α-trifluoromethyl Methyl Ethers 141 with Aryl or Alkenyl Siloxanes.

Enantioconvergent Hiyama reactions can be performed under Ni catalysis with diamines or bis(oxazolines) as chiral ligands and TBAT as fluoride activator. Activated alkyl bromides and chlorides underwent cross-coupling reaction with aryl or alkenyl siloxanes.

2.1.5. Other Organometals

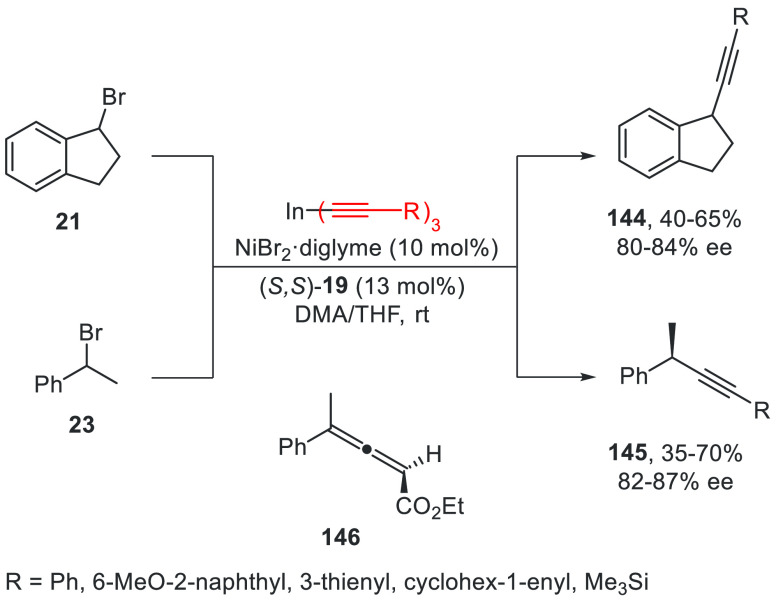

In 2008, Sarandeses and co-workers95 reported the enantioconvergent Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of trialkynylindium reagents with secondary benzylic bromides 21 and 23 using (S,S)-iPr-Pybox (19) as a chiral ligand (Scheme 31). This alkynylation reaction took place in moderate to good yields and up to 87% ee working at room temperature during 140 h and in a 1:1 mixture of DMA/THF. In the case of products 144, the absolute configuration was not determined. Compounds 145 were obtained without isomerization of the triple bond except in the case of ethyl propiolate, which afforded the allene 146 in 30% yield and 77% ee.

Scheme 31. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Secondary Benzyl Bromides 21 and 23 with Alkynylindium Reagents.

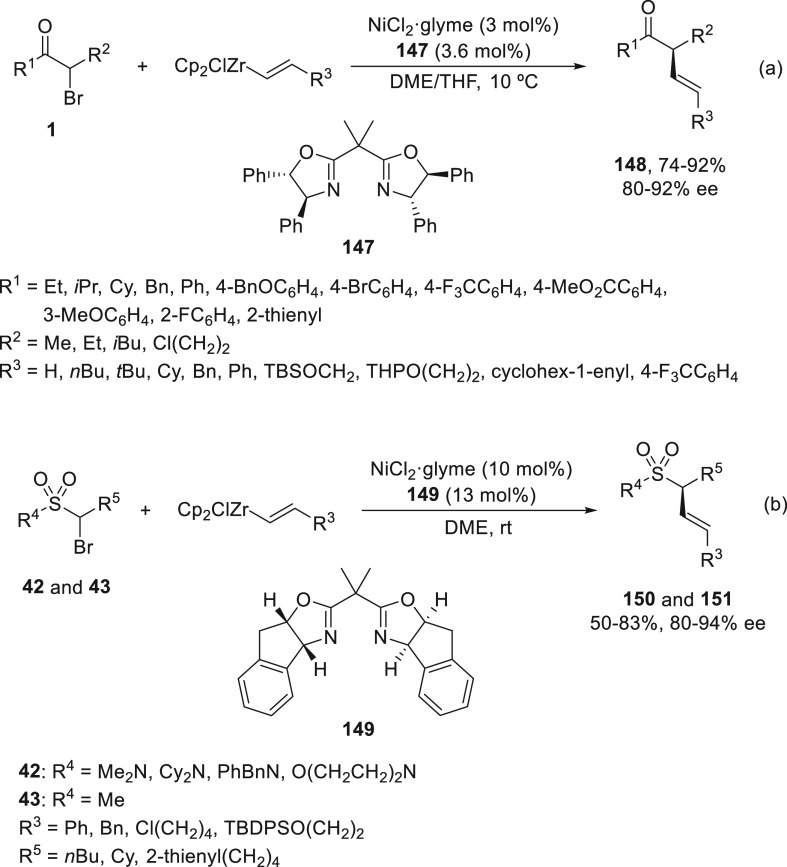

Enantioconvergent and stereospecific Ni-catalyzed alkenylations with organozirconium reagents were described by the Fu group.54,96,97 Initial results were carried out with activated secondary alkyl bromides 1 using (−)-bis(oxazoline) 147 as a chiral ligand under smooth reaction conditions. α-Substituted β,γ-unsaturated ketones 148 were obtained in very good yields and ee with low catalyst loading to keep the (E)-configuration of the starting alkenylzirconium reagent (Scheme 32a). This alkenylation was applied to the cross-coupling of α-bromo sulfonamides 42 and sulfone 43 (R4 = Me; R5 = Cy) with alkenylzirconium reagents using, in this case, ligand 149 to furnish allylic sulfonamides 150 and sulfone 151, respectively (Scheme 32b). In both cases, bis(oxazoline) 149 was the suitable chiral to give the corresponding products in good yields and enantioselectivities.

Scheme 32. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of α-Bromo Ketones 1 and α-Bromo Sulfonamides 42 and Sulfones 43 with Alkenylzirconium Reagents.

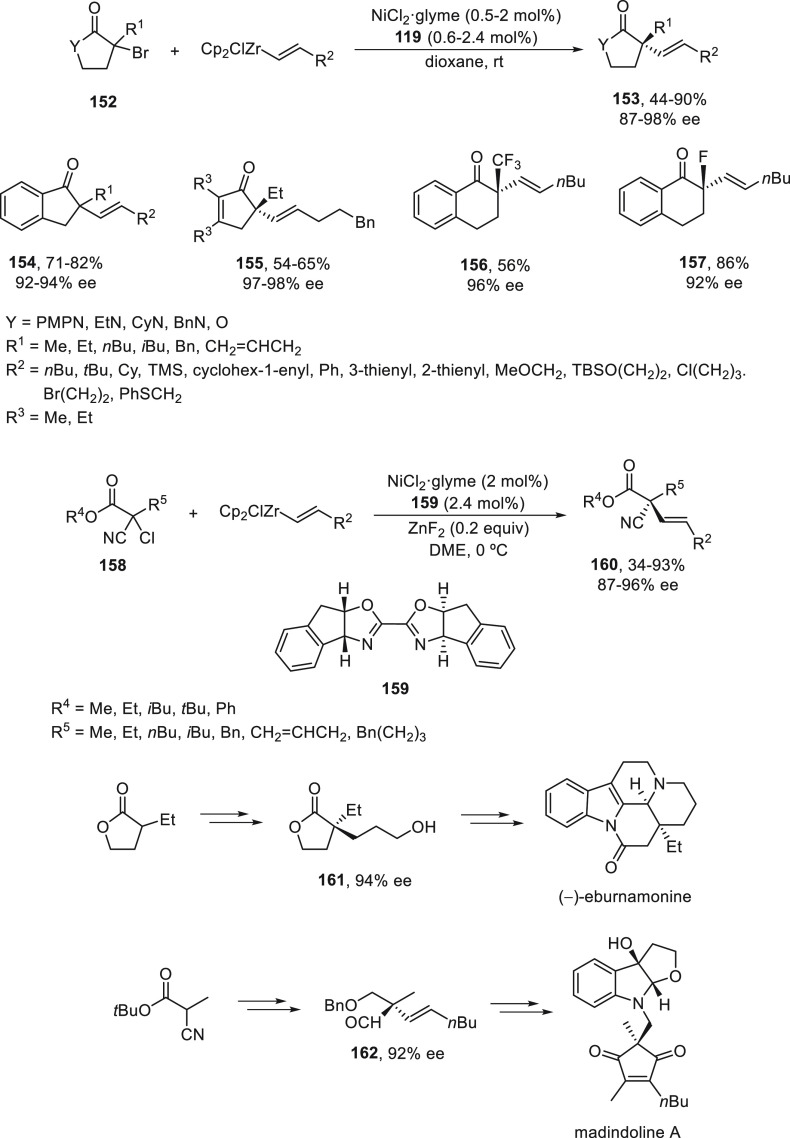

Recently, alkenylzirconium reagents have been used as appropriate nucleophiles for the enantioconvergent challenging alkenylation of activated tertiary alkyl halides.97 Cyclic and acyclic tertiary α-halo carbonyl compounds 152 and 158 reacted with alkenylzirconium reagents to afford enantioenriched α,α-disubstituted products 153–157 and 159, respectively (Scheme 33). For cyclic systems 152, NiCl2/oxazoline 119 was used as catalyst to provide α-alkenylated products 153–157 in good yields and enantioselectivities. In the case of α-chloro-α-cyano esters 158, NiCl2/bis(oxazoline) 159 was the preferred catalyst, and ZnF2 (0.2 equiv) was used as additive to afford product 160, also with good yields and enantioselectivities. As in the case of secondary halides, mechanistic experimental studies suggested the formation of radical intermediates. This method was applied to the formal total synthesis of bioactive natural products, such as (−)-eburnamonine and madindoline A, through the corresponding key intermediates 161 and 162, respectively. Lactone 161 was prepared from racemic 3-ethyloxolan-2-one in four steps with 94% ee, which was previously transformed into the alkaloid (−)-eburnamonine.98 Madindoline A, an inhibitor of interleukin 6, has been previously prepared from aldehyde 162,99 which was prepared in five steps in 92% ee starting from tert-butyl α-cyano propionate.

Scheme 33. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Tertiary Alkyl Halides 152 and 158 with Alkenylzirconium Reagents.

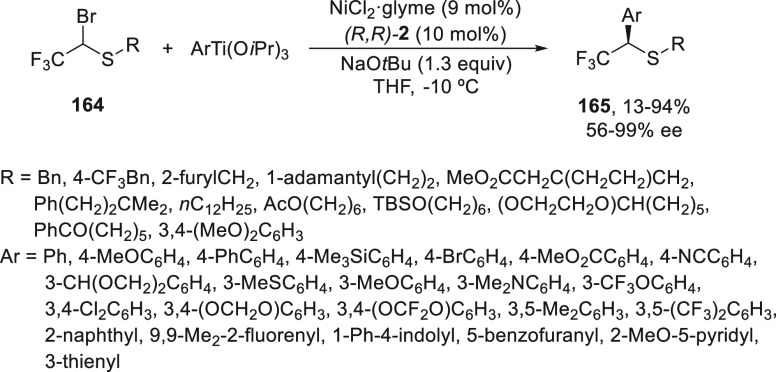

Alkenyl and alkynylaluminum reagents have been employed as nucleophiles in enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions with secondary benzylic bromides 23 by Zhou and co-workers.100 The alkynylation reaction took place using NiBr2/(R,R)-iPr-Pybox (19) as catalyst in a 1:1 mixture of THF/DMA at room temperature to give products 145 with good yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 34). However, the alkenylation reaction was carried out under Pd catalysis using (R)-Binap as chiral ligand in THF at −35 °C to provide enantioenriched aryl alkenes 163 with moderate yields and up to 99% ee.

Scheme 34. Enantioconvergent Ni- and Pd-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of Secondary Benzylic Bromides 23 with Alkynyl and Alkenylaluminum Reagents, Respectively.

Organotitanium reagents possess a lower nucleophilicity than organomagnesium ones, which allows a greater functional group tolerance, and have higher transmetalation rates than organozinc compounds. Varenikov and Gandelman101 employed for the first time these organometals in asymmetric cross-coupling reactions devoted to the synthesis of enantioenriched α-trifluoromethyl thioethers 165. Initial studies about the enantioconvergent Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of α-trifluoromethyl-α-bromomethyl thioethers 164 with aryltrimethoxysilanes gave poor results. However, aryltianium(IV) compounds, prepared by mixing Ti(OiPr)4 with arylmagnesium bromides in the presence of NaOtBu, formed titanate complexes able to react with thioethers 164 using NiCl2/PhBox [(R,R)-2] as catalyst in THF at −10 °C to provide a wide range of products 165 in moderate to good yields and high enantioselectivities (Scheme 35).

Scheme 35. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of α-Trifluoromethyl-α-bromomethyl Thioethers 164 with Aryltitanium(IV) Reagents.

In summary of this Section 2.1 about enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles with organometals, organozinc or organoboron reagents have been largely employed mainly under Ni catalysis and oxazolines or 1,2-diamines as chiral ligands, respectively. For alkenylation reactions, alkenylzirconium reagents using Ni/bis(oxazoline) as catalyst gave the best results, even with tertiary alkyl bromides. In the case of alkynylation reactions of benzylic bromides, alkynylindium and aluminum reagents under Ni catalysis have been successfully used.

2.2. Racemic Alkyl Electrophiles with Other Non-Metallic Nucleophiles

In this Section, enantioconvergent alkylation with alkyl halides of heteroatom-based nucleophiles, such as amines, other carbon nucleophiles, and borylations, mainly under Cu catalysis, will be considered.

2.2.1. Nitrogen Nucleophiles

Direct substitution reactions of alkyl electrophiles by nitrogen nucleophiles via SN1 or SN2 processes suffer from many limitations with regard to scope and/or stereoselectivity. Catalytic processes were developed for aryl electrophiles, such as the copper-catalyzed Ullmann reaction and the palladium-catalyzed Buchwald-Hartwig reaction, that achieved a broad scope for C–N formation. The coupling of alkyl halides with amines was achieved by Peters, Fu, and co-workers102 under the combined action of light and copper catalysis. Then, the same group34,103,104 developed challenging enantioconvergent N-alkylations by racemic secondary and tertiary alkyl halides in the presence of light and a chiral copper catalyst. Initial studies were performed with tertiary α-chloro amides 166 and carbazoles and indoles as nitrogen nucleophiles using CuCl/monodentate phosphine 167, LiOtBu as base, and visible light irradiation (blue LED) in toluene at −40 °C (Scheme 36).103 The resulting N-alkylated carbazoles and indoles 168 and 169 were obtained in good yields and enantioselectivities. Experimental and theoretical studies support the proposed catalytic cycle for this enantioconvergent N-alkylation.104 Two key intermediates, the copper(II) metaloradical IV and the tertiary α-amide organic radical R•, have been characterized by EPR and DFT calculations. These two radicals are combined to furnish the C–N coupling in 77% yield and 55% ee. DFT calculations reckon that the organic radical is resistant to radical–radical homocoupling and, therefore, accessible as a free radical in solution. In this detailed pathway, the previously characterized complex I serves as a photoreductant via excitation to II, which reacts with the electrophile to give the radical R• and intermediate III. After ligand substitution by a second carbazolide ligand and loss of one ligand (L), the characterized intermediate IV is formed. Coordination of the radical R• with IV gives intermediate V, which forms the product regenerating the complex I upon binding L.

Scheme 36. Enantioconvergent Photoreduced Cu-Catalyzed N-Alkylation of Carbazoles and Indoles with α-Chloro Amides 166.

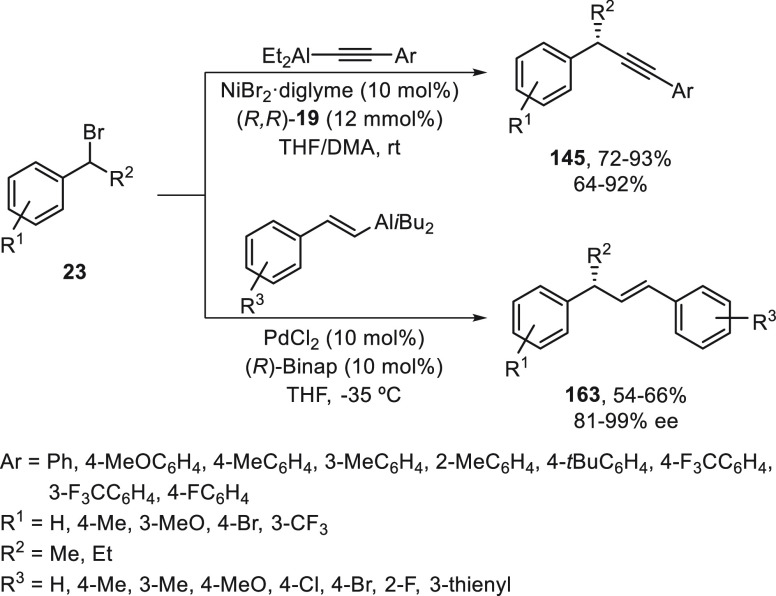

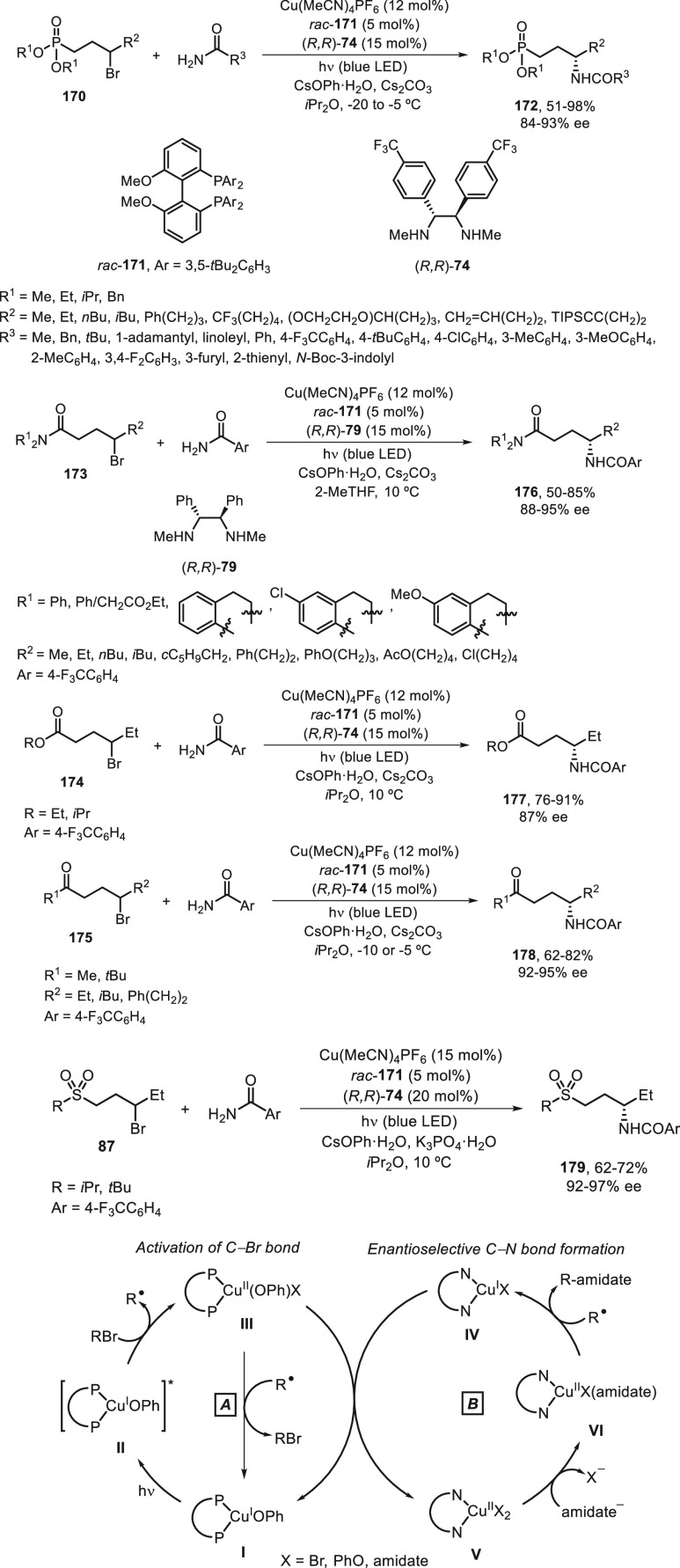

Photoinduced copper-catalyzed amidation of unactivated secondary alkyl halides was initially performed by Peters, Fu, and co-workers with carboxamides105 and carbamates.94 The same group performed an enantioconvergent amidation of racemic secondary alkyl bromides.106 They used a photoinduced copper-catalyzed asymmetric amidation via ligand cooperativity on the basis of three different ligands: a racemic bisphosphine 171, cesium phenoxide, and a chiral diamine (R,R)-79 or (R,R)-74. These ligands assemble in situ to form two distinct catalysts that act cooperatively: a copper/bisphosphine/phenoxide complex I, which serves as photocatalyst, and a chiral copper diamine complex that catalyzes enantioselective C–N bond formation. Alkyl bromides bearing a phosphonoyl group 170 gave γ-aminophosphonic acid derivatives 172 by reaction with carboxamides upon irradiation of the copper-based catalytic system with blue LED lamps in iPr2O at −20 to −5 °C (Scheme 37). Other alkyl bromides 173–175 and 87 bearing Lewis basic functional groups, including γ-bromo amide 173, ester 174, ketone 175 and sulfone 87, provided good enantioselectivity in the nucleophilic substitution reactions and led to products 176–179. The proposed catalytic cycles A and B are based on experimental studies. In cycle A, the photoredox catalyst I gives upon irradiation the excited state of 171·CuIOPh II with a sufficient lifetime to react with the electrophile by an inner-sphere electron-transfer pathway (halogen-atom transfer) to afford the radical R• and intermediate III. Cycle A intersects with cycle B by reaction of intermediate III with the chiral copper complex IV to generate I and V by ligand exchange. Then, a nucleophilic substitution of complex V with the amidate anion leads to complex VI, which reacts with the organic radical R• in an out-of-cage process via coordination of the directing group to CuII followed by C–N bond formation to furnish the product and complex IV.

Scheme 37. Enantioconvergent Photoinduced Cu-Catalyzed N-Alkylation of Carboxamides with γ-Bromo Phosphonates 170, Amides 173, Esters 174, Ketones 175, and Sulfones 87.

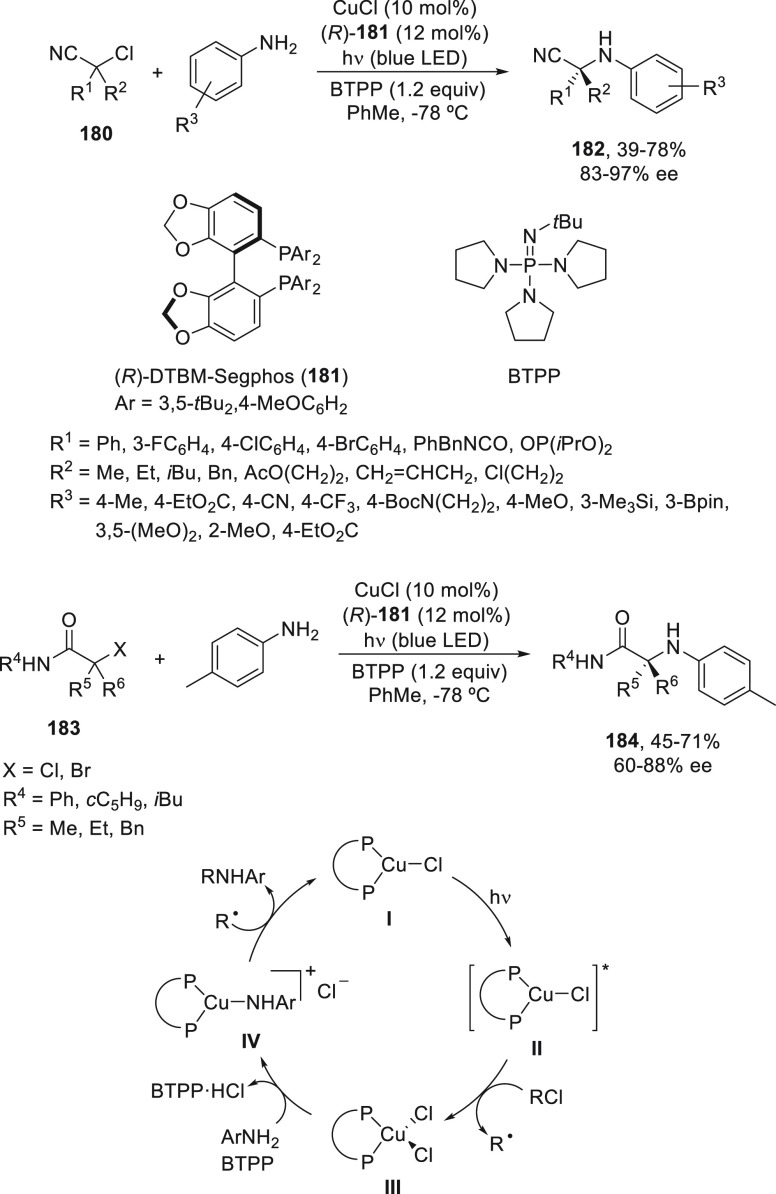

Recently, the same group107 reported the photoinduced copper-catalyzed enantioconvergent alkylation of anilines by activated tertiary α-chloro nitriles 180 (Scheme 38). This substitution reaction took place using CuCl/(R)-DTBM-Segphos (181) as chiral photocatalyst and tert-butylimino-tri(pyrrolidino)phosphane (BTPP) as base in toluene at −78 °C to provide enantioenriched α-amino nitriles 182 with moderate to poor yields and up to 97% ee. Tertiary α-chloro or α-bromo amides 183 gave the corresponding α-amino amides 184 under the same reaction conditions with 45–71% yield and up to 88% ee. Experimental and theoretical studies led to identification of copper-based intermediates, such as the photoreductant L*CuCl (I) and [L*Cu(NHAr)]Cl (IV) as key intermediates. In the proposed catalytic cycle, catalyst I gave intermediate II upon radiation, which abstracts a chlorine atom from the alkyl chloride to form the radical R• and intermediate III. By reaction with the anilido anion intermediate, IV is formed, which reacts with the radical to give the product and regenerates the catalytic complex I.

Scheme 38. Enantioconvergent Photoinduced Cu-Catalyzed N-Alkylation of Anilines with α-Chloro Nitriles 180 and α-Halo Carboxamides 183.

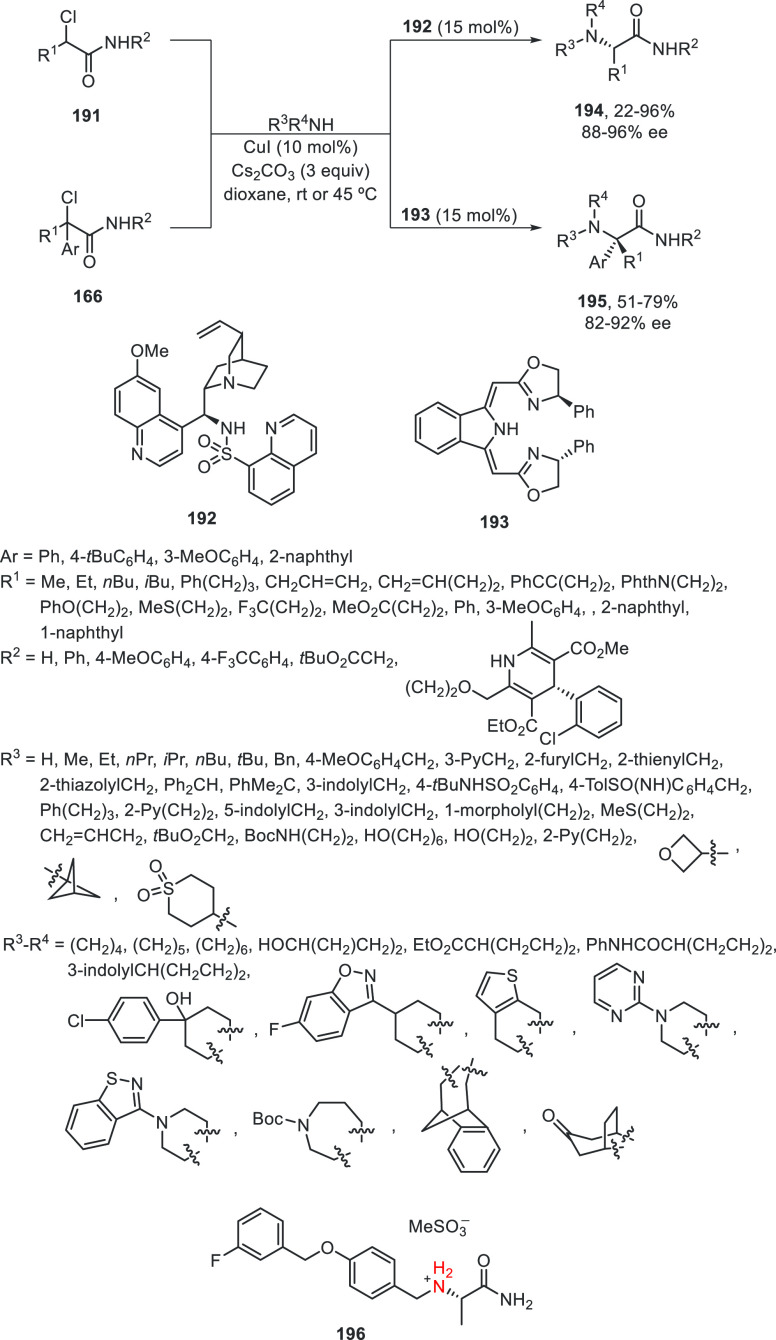

Liu and co-workers108 employed sulfoximines as ammonia surrogates to access α-chiral primary amines. This enantioconvergent Cu-catalyzed radical C–N coupling took place in the absence of light with secondary alkyl halides, such as benzylic bromides 23, α-bromo ketones 1, α-bromo amides 18, and α-bromo nitrile 36, to provide the corresponding N-alkyl sulfoximines 185–188 (Scheme 39). This procedure was carried out under mild thermal conditions using a Cu(I) salt and the bulky N,N,P-ligands 189 or 190 with Cs2CO3 as base in Et2O at room temperature or 0 °C. The authors proposed the formation of complex I able to reduce the alkyl bromide via a single-electron transfer process to generate the alkyl radical R• by an outer-sphere radical substitution to give the product generating the Cu(I) catalyst. Products 185–188 (more than 60 examples) were isolated up to 99% yield and up to >99% ee and were transformed into enantioenriched primary amines by reduction with Mg or with sodium naphthalenide followed by acidic hydrolysis without remarkable losses of enantiopurity. This methodology was applied to the synthesis of commercial drugs, including cinacalcet, dapuxetine, and rivastigmine.

Scheme 39. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed N-Alkylation of Secondary Benzylic Bromides 23, α-Bromo Ketones 1, α-Bromo Amides 18, and α-Bromo Nitrile 36 with Sulfoximines.

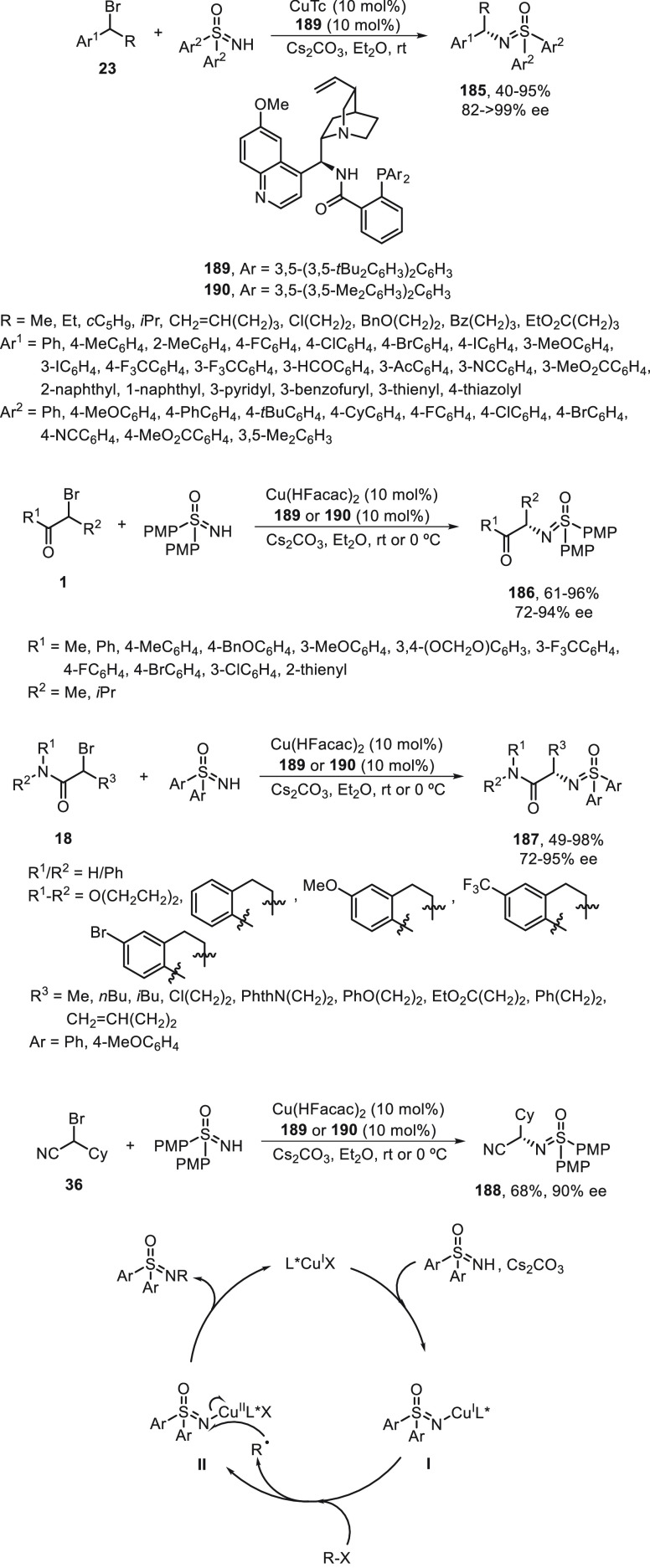

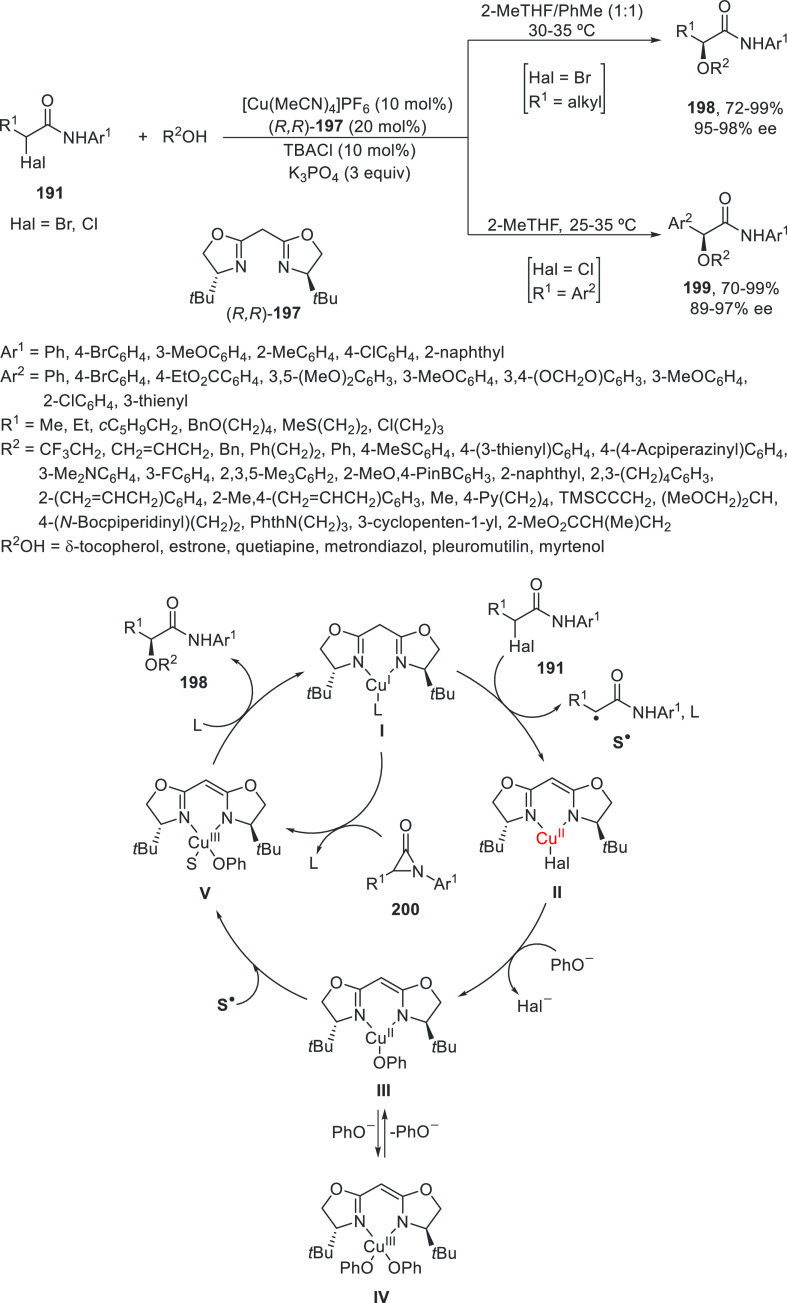

Very recently, Liu and co-workers109 were able to develop the enantioconvergent Cu-catalyzed N-alkylation of aliphatic amines using chiral tridentate anionic ligands 192 and 193. α-Chloro amides 191 and 166 reacted with a wide variety of primary and secondary aliphatic amines, even ammonia (more than 125 examples), to afford α-amino amides 194 and 195, respectively, with 22–99% yields and 88–97% ee (Scheme 40). This procedure was applied to the synthesis of 12 drugs or bioactive molecules, including the anti-Parkinson drug XADAGO 196 with 62% yield and 94% ee. On the basis of experimental studies, the authors proposed the formation of a cuprate intermediate I, which undergoes intramolecular oxidative addition to give II and III in equilibrium. Subsequent outer-sphere amine attack to III delivers IV, which upon ligand exchange with the α-chloro amide forms the N-alkylated product.

Scheme 40. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed N-Alkylation of α-Chloro Amides 191 and 166 with Aliphatic Amines and Ammonia.

Enantioconvergent cross-coupling amination and amidation of alkyl electrophiles has been mainly performed under photoinduced copper-catalyzed conditions and using phosphines as chiral ligands. In the absence of light, sulfoximines and aliphatic amines are able to perform the N-alkylation of activated alkyl bromides under Cu catalysis.

2.2.2. Oxygen Nucleophiles

Cross-coupling reactions between α-bromo amides 191 and alcohols under Cu catalysis were reported by Kürti and co-workers in 2018.110 However, just recently, Chen and Fu111 achieved the enantioconvergent process using Cu(II) and a chiral bis(oxazoline) 197 (Scheme 41). The cross-coupling of α-bromo and α-chloro amides 191 took place with aliphatic alcohols and phenols to efficiently give α-alkoxy amides 198 and 199 in very good yields and with high enantioselectivity. These reaction conditions were also applied to the enantioconvergent alkylation of nitrogen nucleophiles, such as aliphatic primary amines and anilines. Experimental studies support that the process proceeds through a free radical pathway. Thus, Cu(I) complex I reacts with the α-halo amide to give the Cu(II) complex II and the alkyl radical S•. This complex II undergoes ligand substitution with the oxygen nucleophile to provide complexes III and IV. Then, the alkyl radical S• reacts at copper to form organocopper(III) complex V via an out-of-cage pathway. This complex V can also be formed by oxidative addition of the aziridinone 200 to complex I along with complexation of phenol. Reductive elimination determines the stereochemistry and affords the product and complex I.

Scheme 41. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling of α-Halo Amides 191 with Oxygen Nucleophiles.

2.2.3. Phosphorus Nucleophiles

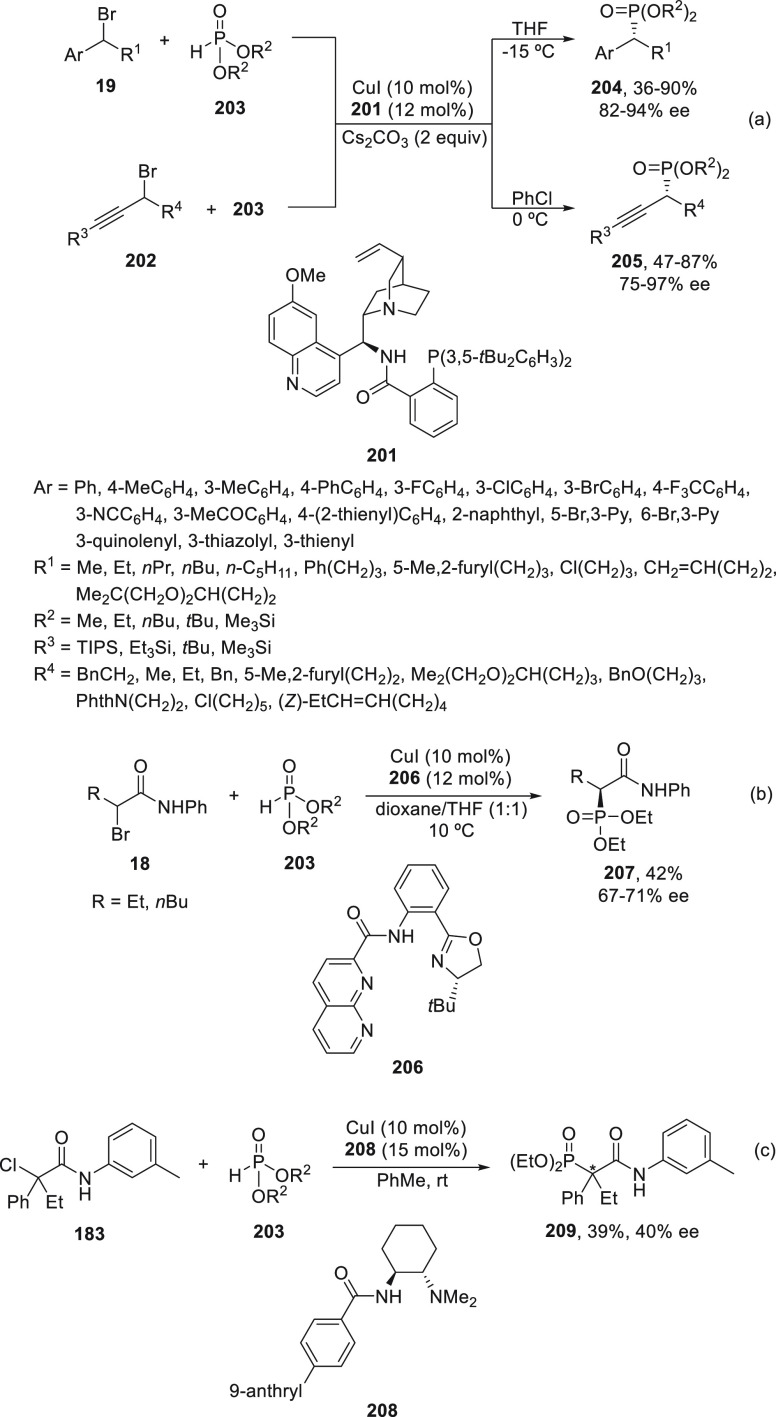

The Michaelis–Becker (M-B) reaction of H-phosphonates with alkyl halides is a direct method for the synthesis of C-phosphonates.112 Only recently, Liu and co-workers113 reported the enantioconvergent copper-catalyzed M-B-type C(sp3)–P cross-coupling reaction. By using the multidentate chiral anionic ligand 201, benzylic bromides 23 and propargylic bromides 202 reacted with H-phosphonates 203 to furnish products 204 and 205, respectively, with remarkable chemo- and enantioselectivity (Scheme 42a). In the case of α-halo carboxamides 18 and 183, ligands 206 and 208 were used, respectively, to provide products 207 and 209 with moderate results (Schemes 42b,c). Concerning the reaction mechanism, a radical trap experiment with TEMPO supports a stereoselective radical pathway over a stereospecific SN2-type process.

Scheme 42. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Michaelis–Becker Reaction of Alkyl Halides with H-Phosphonates.

2.2.4. Other Carbon Nucleophiles

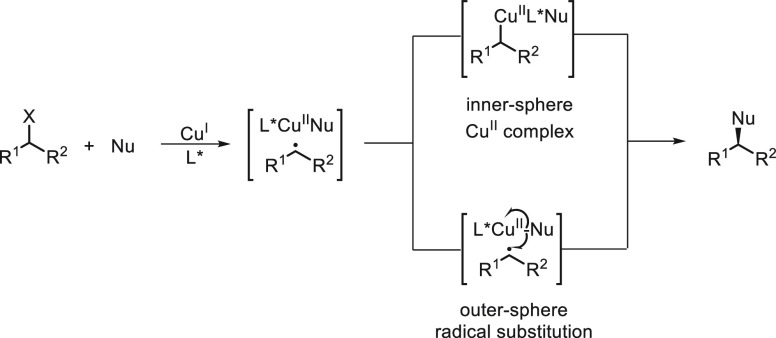

Enantioconvergent cross-coupling of racemic alkyl electrophiles with carbon nucleophiles, such as cyanides, acetylides, and nitronates, by generation of achiral radicals via an inner-sphere single-electron transfer (SET) process with a chiral transition-metal catalyst will be considered. In addition, under photoredox catalysis an outer-sphere SET strategy produces alkyl radicals that by enantioselective radical coupling forms C(sp3)–C bonds. In Scheme 43, the Cu-catalyzed enantioconvergent radical C(sp3)–C cross-coupling reactions of alkyl electrophiles with nucleophiles are depicted.114

Scheme 43. Enantioconvergent Strategy for Cu-Catalyzed Radical C(sp3)–C Cross-Coupling Reactions.

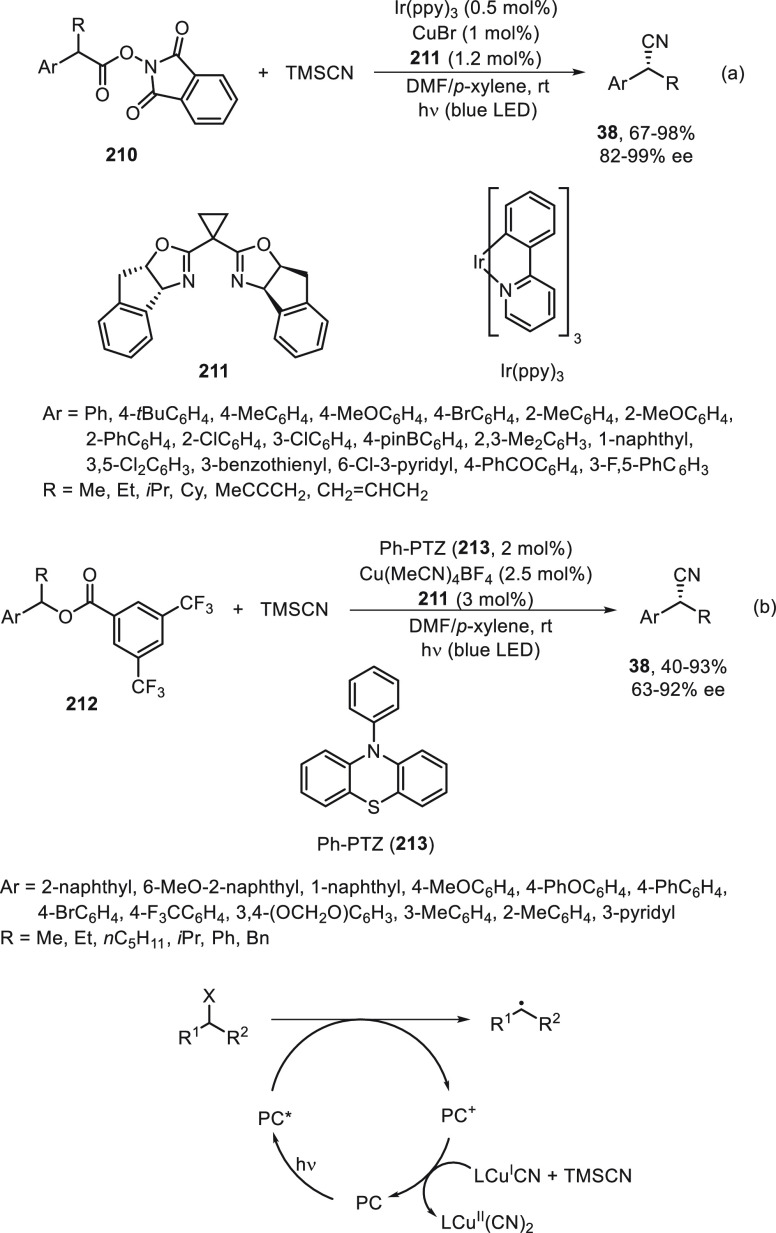

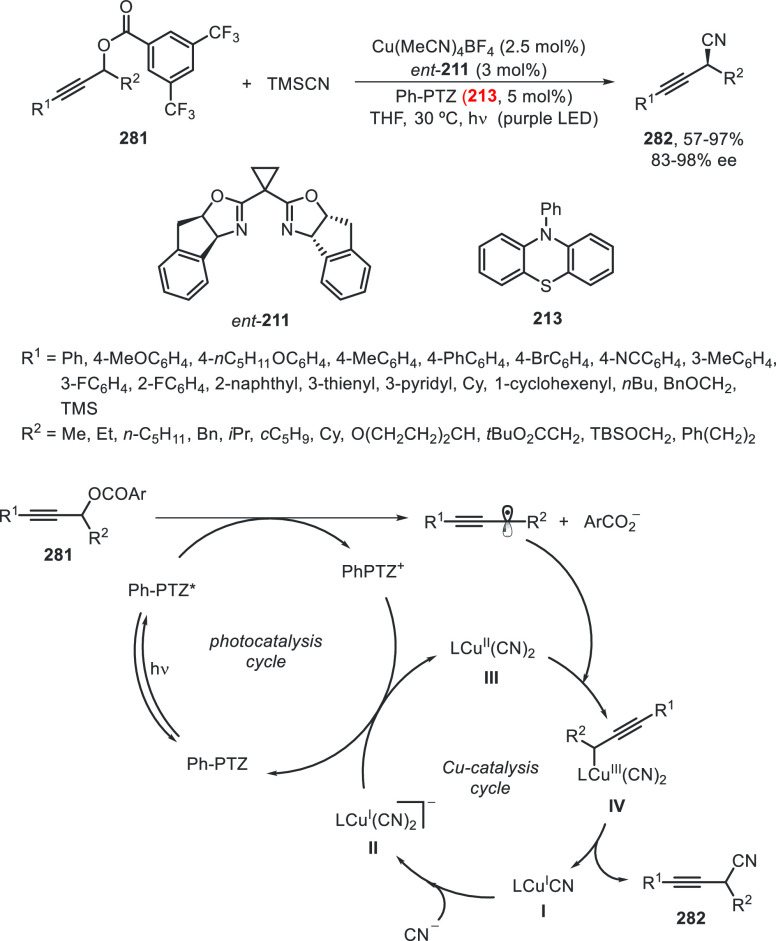

Concerning cyanation reactions, for the synthesis of enantioenriched benzylic nitriles, two types of enantioconvergent photocatalyzed cross-couplings have been reported, either starting from carboxylic acid derivatives 210(115) or benzylic alcohol esters 212.116 Liu and co-workers115 performed decarboxylation of N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHP) esters 210 in the presence of trimethylsilyl cyanide (TMSCN) to give the corresponding benzylic nitriles 38 in up to 98% yield and 99% ee (Scheme 44a). This process was carried out using Ir(ppy)3 as photocatalyst under blue LED irradiation and CuBr/bis(oxazoline) 211 as chiral metal catalyst. Conversely, Xiao and co-workers116 started from 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzoyl esters 212, which by reaction with TMSCN afforded the corresponding nitriles 38 in up to 93% yield and 92% ee (Scheme 44b). In this case, an organic photocatalyst Ph-PTZ (213) and Cu(MeCN)4BF4/bis(oxazoline) 211 as chiral metal catalyst were used. In a simplified catalytic cycle to explain the initiation of these reactions, starting compounds 210 and 212 gave benzylic radicals by photocatalytic decarboxylation and deoxygenation, respectively, by transfer of one electron of the excited photocatalyst (PC*). This PC* can oxidize L*CuICN to form L*CuIICN, which reacts with TMSCN to form L*CuII(CN)2. Subsequent combination of the benzylic radical with the active species L*CuII(CN)2 by an outer-sphere radical substitution would provide the coupling product 38.

Scheme 44. Enantioconvergent Photocatalyzed Cu-Catalyzed Cyanation of Esters 210 and 212 with TMSCN.

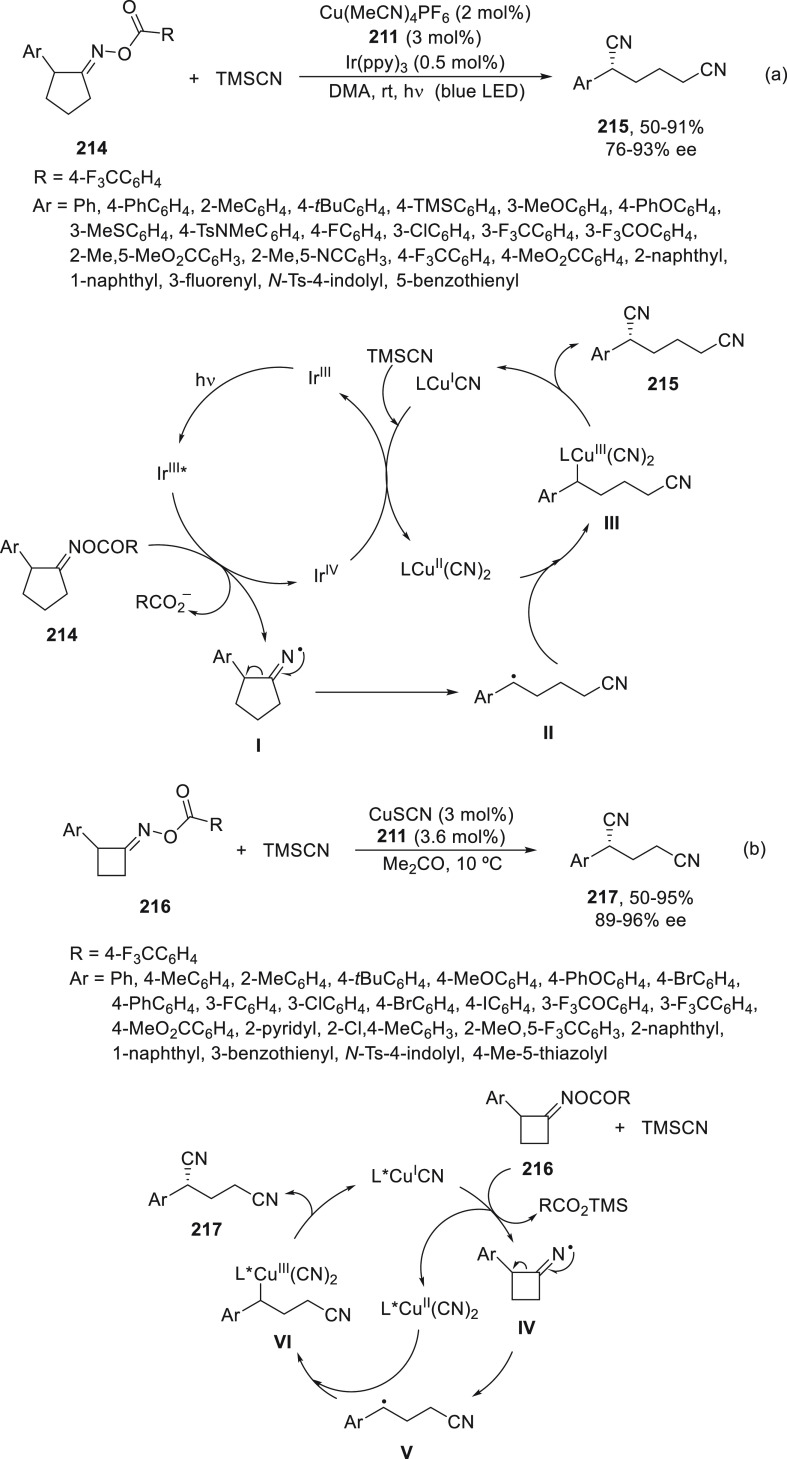

Wang and co-workers117 employed the dual photoredox/copper catalysis for the enantioconvergent ring-opening cyanation of cyclopentanone oxime esters 214 with TMSCN to access enantioenriched 1,6-dinitriles 215 in high yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 45a). This process is based on the iminyl radical-mediated ring-opening of cyclic oxime derivatives by cleavage of the C–C single bond via β-scission reported by Zard and co-workers.118 Alternatively, cyclobutanone oxime esters 216 were transformed into enantioenriched 1,5-dinitriles 217 only under copper catalysis, presumably because of the higher strain release of four-membered ring than cyclopentanones (Scheme 45b).119 In both cases, bis(oxazoline) 211 was used as chiral ligand. In the proposed mechanism based on experimental studies, in the catalytic cycle for cyclopentanone oxime esters 214, a SET process between the oxime and the excited state of photocatalyst Ir(III)* provided iminyl radical I and the Ir(IV) species, which oxidized L*CuICN to L*CuII(CN)2 by reaction with TMSCN. Intermediate I generates by C–C bond cleavage the benzylic radical II, which is trapped by L*CuII(CN)2 to deliver intermediate III. Final reductive elimination of III gives the desired product 215 and regenerates the catalyst. For the cyclobutanone oxime esters 216, an initial SET process with L*CuICN in the presence of TMSCN affords L*CuII(CN)2 and iminyl radical IV, which evolves to radical V by C–C bond cleavage. Radical V reacts with L*CuII(CN)2 to give species VI followed by reductive elimination to provide dinitrile 217 and the catalyst L*CuICN.

Scheme 45. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Cyanation of Cyclopentanone and Cyclobutanone Oxime Esters 214 and 216 with TMSCN to Give Dinitriles 215 and 217.

Xiao, Chen, and co-workers120 independently reported the cyanation of cyclopentanone oxime esters 214 under dual photoredox and Cu catalysis using the reaction conditions depicted in Scheme 44b. In this case, they used a 2 × 3 W purple LED and DMA as solvent at 30 °C to provide dinitriles 215 with 75–99% yield and 81–94% ee.

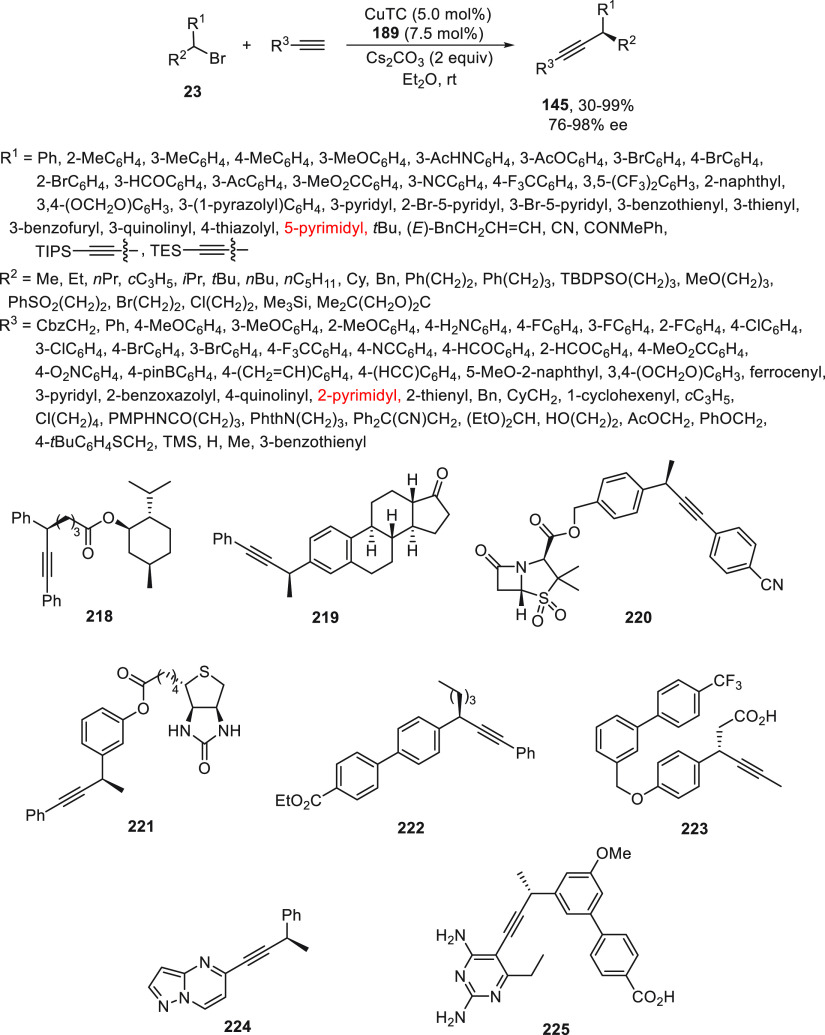

Enantioconvergent C(sp3)–C(sp) cross couplings of secondary alkyl halides with alkynes have been developed by Liu and co-workers121 under CuTC (TC = thiophene-2-carboxylate) catalysis. This radical process needed the strong donating multidentate ligand developed by Dixon et al.122 (189) to enhance the reducing capability of the Cu catalyst, as well as to suppress the Glaser homocoupling.114,121 Benzylic bromides 23 reacted with terminal aromatic and aliphatic acetylenes, including acetylene, itself, using Cs2CO3 as base in ethyl ether at room temperature to provide products 145 (>120 examples) with good yields and enantioselectivities (Scheme 46). Synthetic applications of these transformations employed the core of several bioactive molecules, such as l-menthol, estrone, sulbactam, biotin, and a mesogenic compound 218–222. In addition, they prepared chiral alkyne drug leads, such as 223 (AMG 837), a G-protein coupled receptor GPR40 agonist, and 224, a patented mGluR modulator. They also prepared a dihydrolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitor UCP1172 225 for drug-resistant bacteria treatment and other bioactive molecules. The reaction possibly proceeds by formation of the alkynylcopper(I) complex I, which undergoes a SET process with the racemic alkyl bromide to afford the radical species, and the CuII intermediate II. Subsequent coupling of both species delivers the coupling product and releases the catalyst.

Scheme 46. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Reaction of Secondary Benzylic Bromides 23 with Acetylenes.

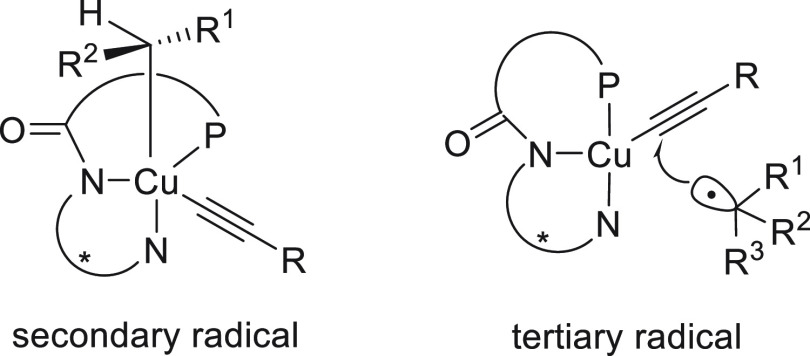

For the Cu-catalyzed enantioconvergent C(sp3)–C(sp) cross-coupling of tertiary electrophiles with alkynes, Liu and co-workers123 have developed tailor-made N,N,N-ligands on the basis of mechanistic studies. DFT calculations revealed that the coupling of the tertiary alkyl radical and the alkynyl group proceeded via an outer-sphere radical substitution-type C–C bond-formation pathway (Figure 2). However, the secondary alkyl radical is involved in the reductive elimination from an inner-sphere Cu(III) intermediate formed upon radical trapping121 (Figure 2). The enantiodetermining transition states in the outer-sphere C–C bond-formation mechanism are less organized, and therefore, an appropriate ligand should favor the accommodation of the sterically bulky tertiary radical.

Figure 2.

TSs for the Cu-catalyzed cross-coupling of secondary and tertiary radicals with acetylenes.

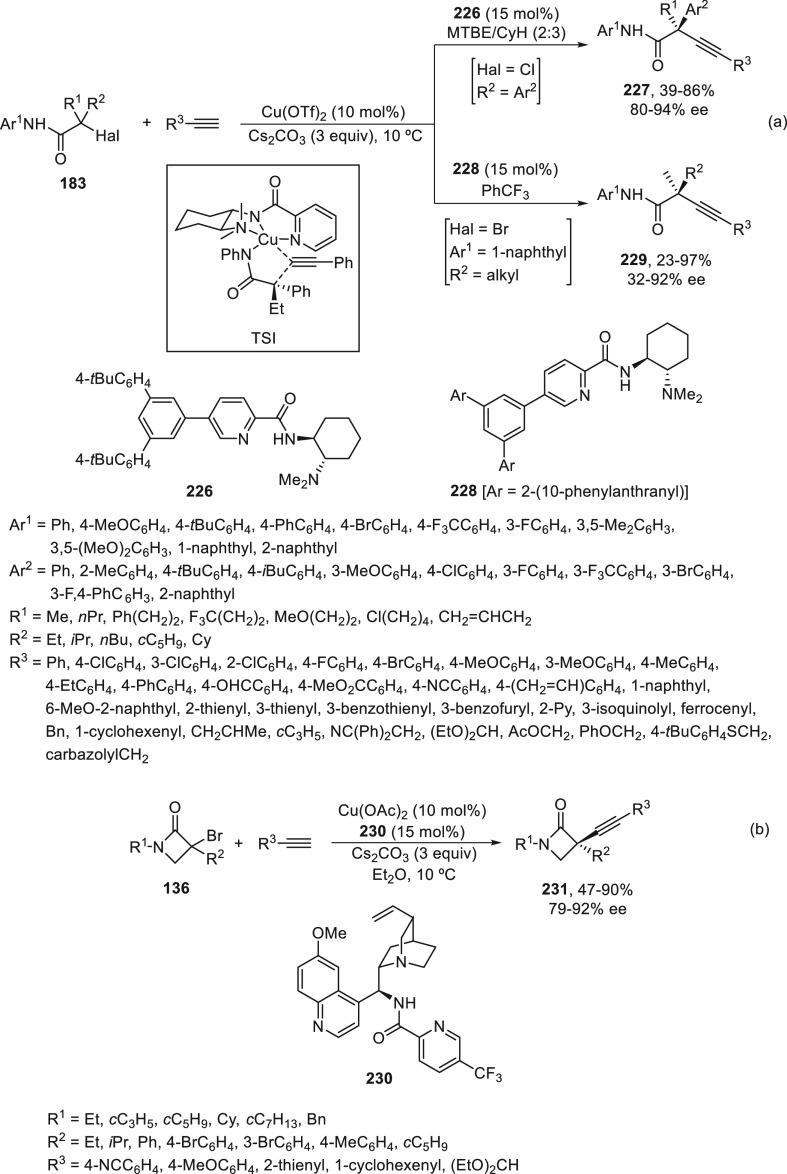

In the case of the cross-coupling of α-chloro amides 183 bearing an aryl group at the α-position, ligand 226 was the most efficient and afforded products 227 in 39–86% yields with 80–94% ee (Scheme 47a).123 α-Bromo amides 183 with two alkyl groups at the α-position were cross-coupled with terminal acetylenes in the presence of ligand 228 to provide products 229 in 23–67% yields with 32–92% ee (Scheme 47a). Cross-coupling of α-bromo-β-lactams 136 with terminal acetylenes was achieved using the chiral ligand 230 to furnish products 231 in good yields (47–90%) with 79–92% ee (Scheme 47b). DFT calculations explained the efficient enantiodiscrimination on the basis of the enantiodetermining outer-sphere radical group transfer pathway (see, TS).

Scheme 47. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Sonogashira–Hagihara Reaction of Tertiary α-Halo Amides 183 and 136 with Acetylenes.

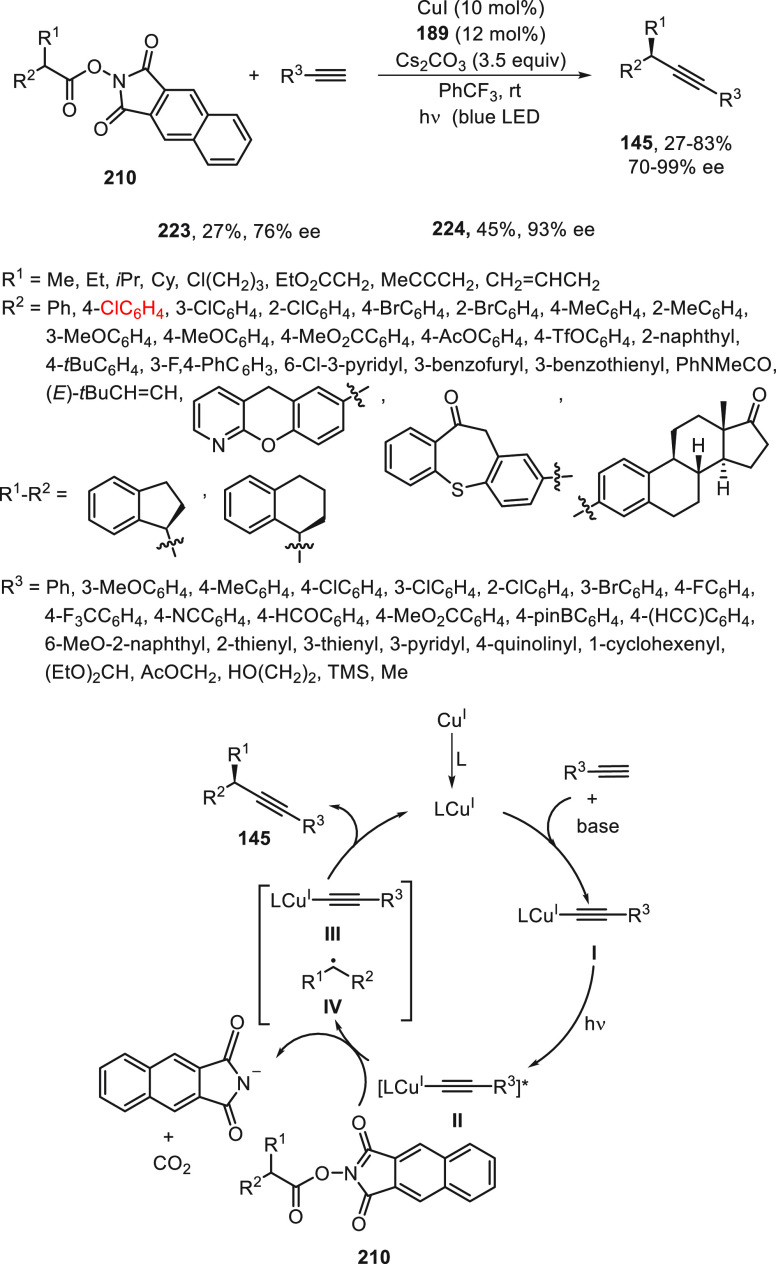

The same group124 performed the enantioconvergent radical decarboxylative C(sp3)–C(sp) cross-coupling by reaction of NHP-esters 210 with terminal alkynes. This photoinduced copper-catalyzed alkynylation of esters 210 as radical precursors used the anionic chiral multidentate N,N,P-ligand 189 for the enantiocontrol over prochiral radical intermediates to avoid their homodimerization. Because of the use of stable and easily available NHP-type esters 210, a broader substrate scope compared with their alkyl halide counterparts 23 was observed, which gave products 145 in moderate to good yields and excellent enantioselectivities (Scheme 48). In addition, a tandem one-pot procedure was developed starting from carboxylic acids, which were esterified and then, without purification, submitted to the standard asymmetric radical decarboxylative alkynylation. On the basis of experimental studies, a possible catalytic cycle was proposed. Thus, intermediate I was excited to give complex II, which transfers one electron to NHP-type ester 210 to deliver the CuII-complex III. The formed anionic radical of ester 210 undergoes a radical decarboxylation to generate the radical intermediate IV. Finally, C(sp3)–C(sp) bond formation with III provides the final product 145 and regenerates the catalyst L*CuI complex.

Scheme 48. Enantioconvergent Photocatalytic and Copper-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Alkynylation of Esters 210.

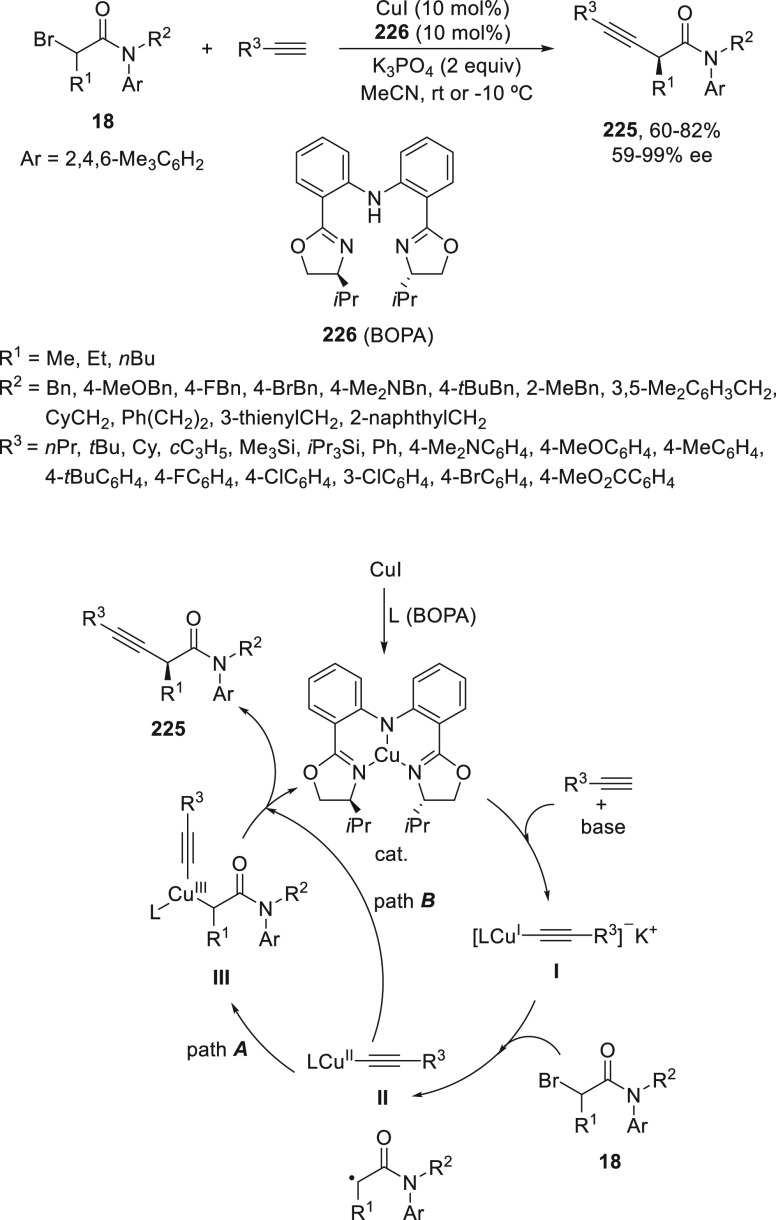

Zhang and co-workers125 reported an enantioconvergent Cu-catalyzed alkynylation reaction of α-bromo amides 18 with terminal alkynes to provide β,γ-alkynyl amides 225 (Scheme 49). They used as anionic chiral ligand114 a bis(oxazoline) diphenylanaline 226 (BOPA) containing a central anionic nitrogen σ-donor and two lone pair donors from the oxazoline units reported by Nakada et al.,126 whereas simple chiral bis(oxazoline) ligands are not effective in this cross-coupling reaction. Racemic α-bromo amides bearing a 2,4,6-trimethyphenyl group at the nitrogen are critical for good stereocontrol to give products 225 with good yields and high enantioselectivities. The authors proposed two possible pathways involving either an inner-sphere CuIII complex III, which undergoes reductive elimination to generate the product (path A), or the radical undergoes direct out-of-cage bond formation with the CuII species II to furnish the product (path B).

Scheme 49. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Sonogashira–Hagihara Reaction of α-Bromo Amides 18 with Acetylenes.

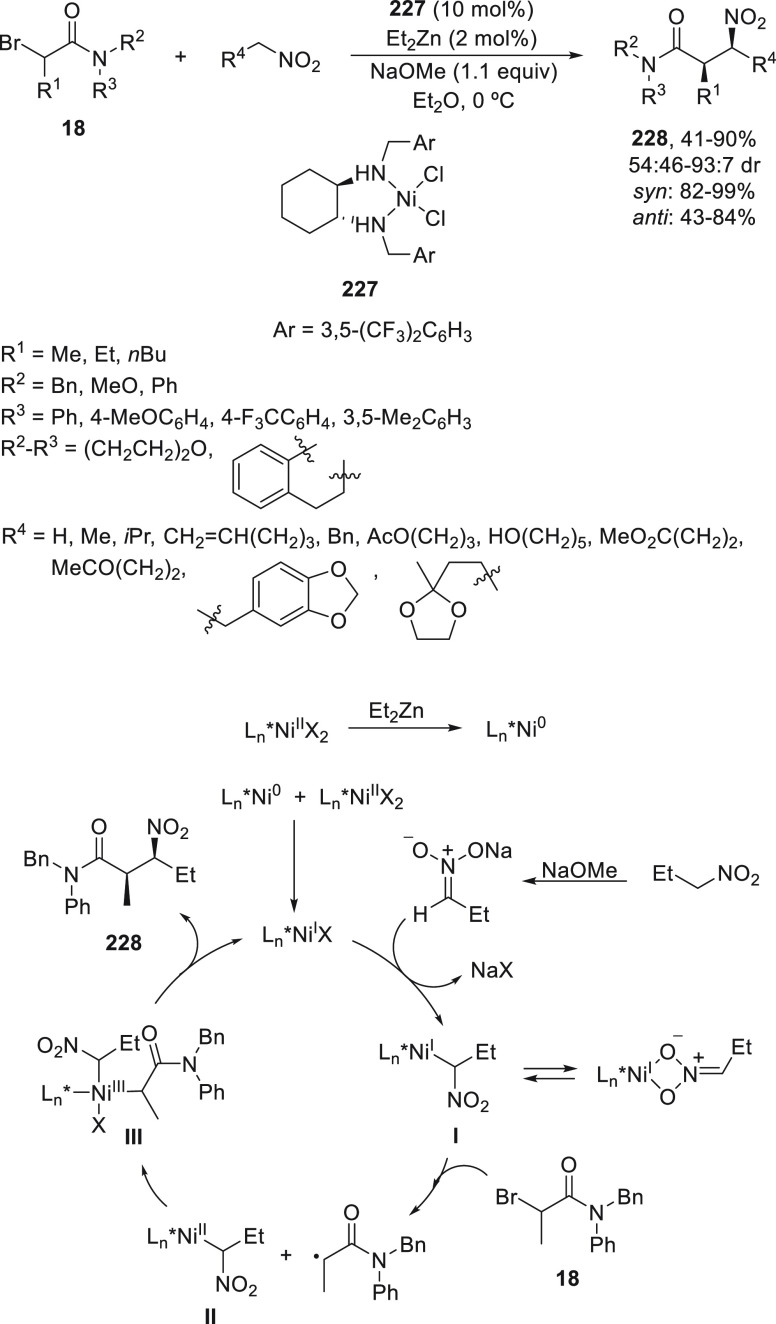

Enantioconvergent alkylation of nitroalkanes with racemic α-bromo amides 18 has been carried out under asymmetric Ni catalysis by Watson and co-workers.127 They employed the Ni-precatalyst 227 (10 mol %), Et2Zn (2 mol %) as in situ reductant, and NaOMe (1.1 equiv) as base in ethyl ether at 0 °C to provide β-nitro amides 228 mainly as syn diastereomers (Scheme 50). In the proposed mechanism, initial reduction of NiII to Ni0 followed by comproportionation with the excess of NiII complex 227 results in a NiI catalyst. Simultaneous deprotonation of the nitroalkane by NaOMe gives a nitronate anion, which undergoes anion exchange with the NiI complex to result in intermediate I. This Ni nitronate reacts with the α-bromo amide via a stepwise oxidative addition to form the NiII intermediate II and subsequently with the radical to form the NiIII species III. Reductive elimination of III provides the product and regenerates the catalyst.

Scheme 50. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Reaction of α-Bromo Amides 18 with Nitroalkanes.

For the enantioconvergent decarboxylative cyanation of esters, a cooperative photoredox and copper/bis(oxazoline) catalysis produces enantioenriched benzylic nitriles. Iminyl-radical-triggered C–C bond cleavage of cyclohexanone oxime esters under Cu/bis(oxazoline) catalysis gave chiral 1,6- and 1,5-dinitriles. In the case of alkynylation reactions of benzylic bromides or NHP esters under Cu catalysis, the presence of a chiral multidentate N,N,P-ligand was crucial. Alkynylation reaction under Cu catalysis of α-bromo amides also needs a multidentate anionic N,N,N-ligand. Alkylation of nitroalkanes with α-bromo amides has been performed with NiCl2 and Et2Zn as reductant using a chiral 1,2-diamine ligand. In all these processes, radical intermediates are involved.

2.2.5. Boron Reagents

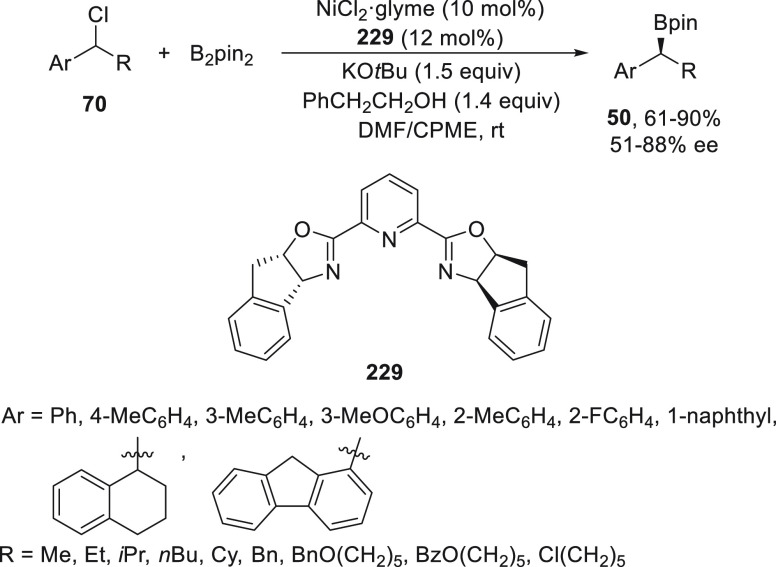

Concerning borylation of alkyl halides under metal catalysis, Miyaura borylation provided C–B bond formation to give alkylboranes. Dunik and Fu128 reported the Ni-catalyzed cross-coupling reaction of primary, secondary, and tertiary alkyl halides with diboron reagents. The resulting boronic esters can be aminated, hydroxymethylated, and arylated. Enantioenriched alkylboron compounds were converted with high retention of the configuration.129 Enantioconvergent Ni-catalyzed borylation of racemic secondary benzylic chlorides 70 was described by Fu and co-workers.130 The corresponding benzylic boronic esters 50 were obtained with good yields and enantioselectivities using NiCl2/bis(oxazoline) 229 as catalyst and B2pin2 as borylating reagent (Scheme 51). The authors demonstrated that enantioenriched benzylic chlorides do not undergo racemization under these reaction conditions. In the proposed mechanism, a radical pathway128 analogous to that described for the Kumada and Negishi reactions (see Section 2.1) was suggested.

Scheme 51. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Miyaura Borylation of Benzylic Chlorides 70.

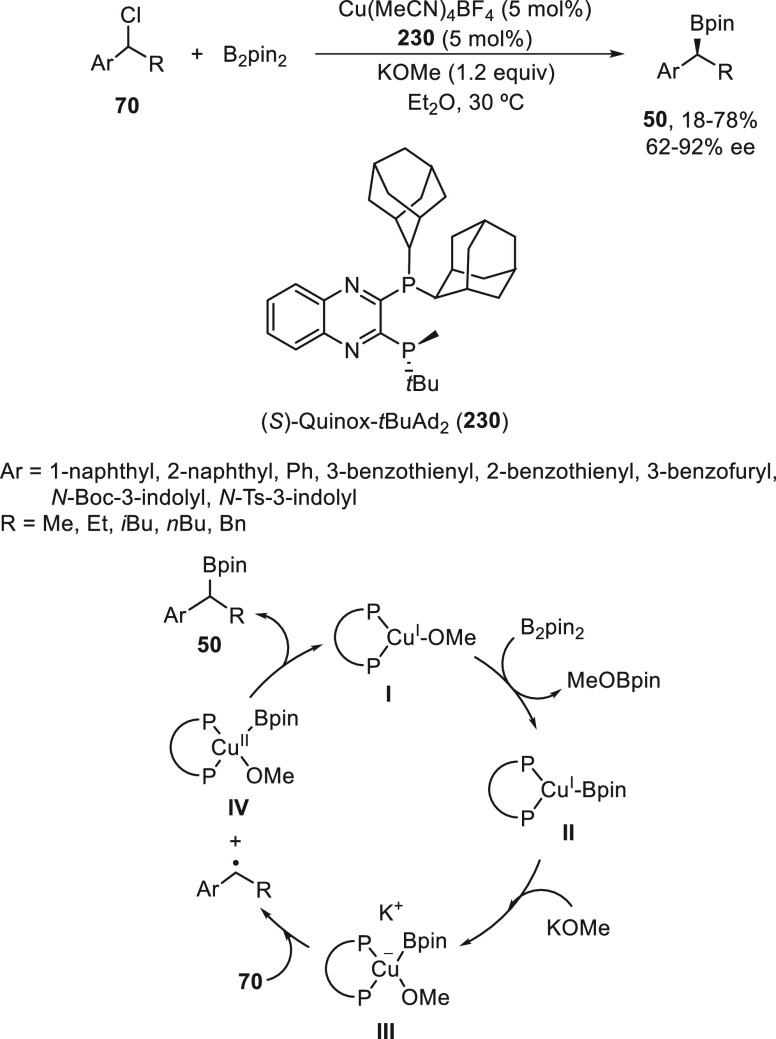

The copper(I)-catalyzed enantioconvergent borylation of racemic benzylic chlorides 70 with B2pin2 has been reported by Ito and co-workers.131 Boronic esters 50 resulted in moderate to good yields and enantioselectivities using Cu(MeCN)4BF4/bisphosphine (S)-quinox-tBuAd2230 as chiral catalyst (Scheme 52). Mechanistic studies on copper(I)-catalyzed borylation reactions have led to a plausible catalytic cycle that involves a radical intermediate.131,132 Catalyst I reacts with B2pin2 to give the borylcopper(I) species II, which reacts with KOMe to provide cuprate III. SET from III to benzylic chloride generates the benzylic radical and the Cu(II) species IV. Subsequent enantioselective borylation of the radical by intermediate IV furnishes the product 50 and regenerates the catalyst I.

Scheme 52. Enantioconvergent Cu-Catalyzed Miyaura Borylation of Benzylic Chlorides 70.

2.3. Racemic Alkylmetals with Electrophiles

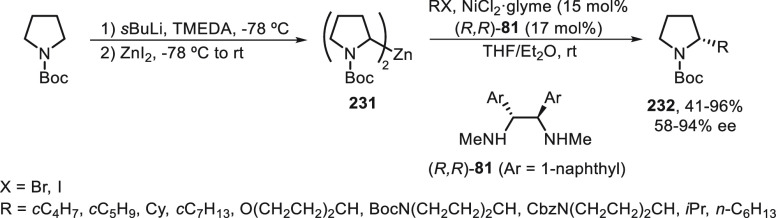

Enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions for C(sp3)–C bond formation can be also performed through an umpoled strategy using racemic secondary alkyl metals. The first reverse polarity process was described by Kumada and co-workers133 using a racemic benzylic Grignard reagent (PhCHMeMgCl) and vinyl bromide as reaction partners and Ni complexes of chiral (aminoalkylferrocenyl)phosphines to generate enantioenriched 3-methylallylbenzene. Fu and co-workers134 performed the enantioconvergent Negishi reaction of α-zincated N-Boc-pyrrolidine 231 with alkyl halides under NiCl2/diamine 81 catalysis (Scheme 53). The resulting enantioenriched α-alkyl-N-Boc-pyrrolidines 232 were obtained with good yields when alkyl iodides were employed as electrophiles (50–96%), with lower yields with alkyl bromides (41–80%), and with good enantioselectivities, in general.

Scheme 53. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reactions of Racemic α-Zincated N-Boc-pyrrolidine 231 with Alkyl Halides.

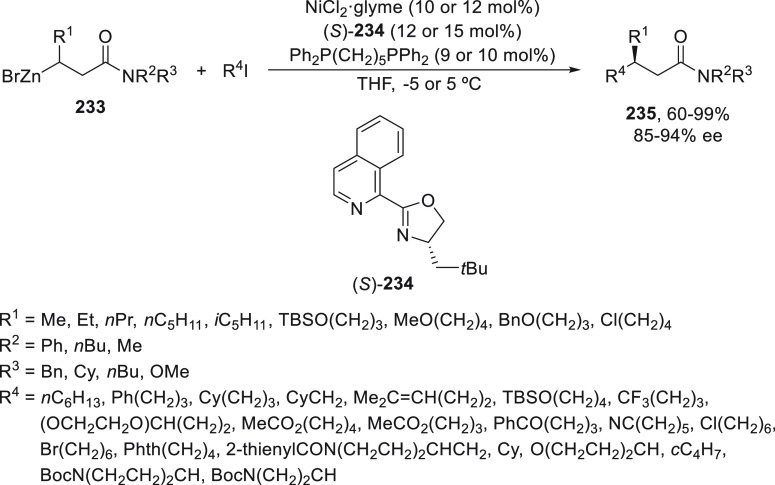

The same group recently reported135 this type of cross-coupling reaction using β-zincated amides 233 and a broad range of alkyl iodides (Scheme 54). The chiral catalyst NiCl2/isoquinoline-oxazoline 234 gave products 235 with good yield and ee. The reaction with primary alkyl groups was performed with 10 mol % of NiCl2 and 12 mol % of ligand at −5 °C, whereas secondary alkyl iodides needed a higher loading, 12 mol % NiCl2, and 15 mol % ligand at 5 °C.

Scheme 54. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reaction of Racemic β-Zincated Amides 233 with Alkyl Iodides.

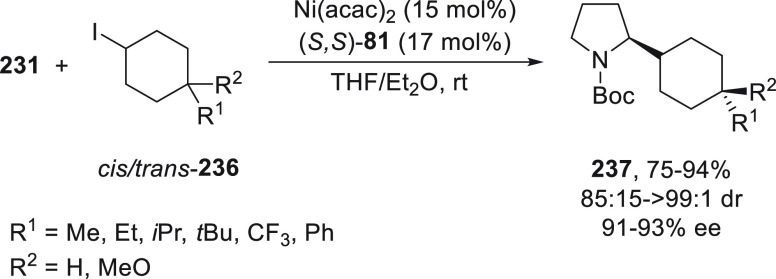

Doubly enantioconvergent cross-coupling of racemic alkyl nucleophiles and electrophiles was also described by Fu and co-workers.136 Vicinal stereocenters are generated with very good stereoselectivity when α-zincated N-Boc-pyrrolidine 231 was allowed to react with 4-substituted cyclohexyl iodides 236 under Ni catalysis (Scheme 55). This Negishi reaction proceeds with good yields to give products 237 with good ee and diastereoselectivity, and it also proceeds with 4,4-disubstituted and 3,5-disubstituted cyclic iodides. With respect to the new C–C bond, the chiral catalyst controls the stereochemistry of the stereocenter in the nucleophile, and the substrate controls the stereochemistry of the stereocenter generated in the electrophile.

Scheme 55. Doubly Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Negishi Reaction of α-Zincated N-Boc-pyrrolidine 231 with Racemic Alkyl Electrophiles 236.

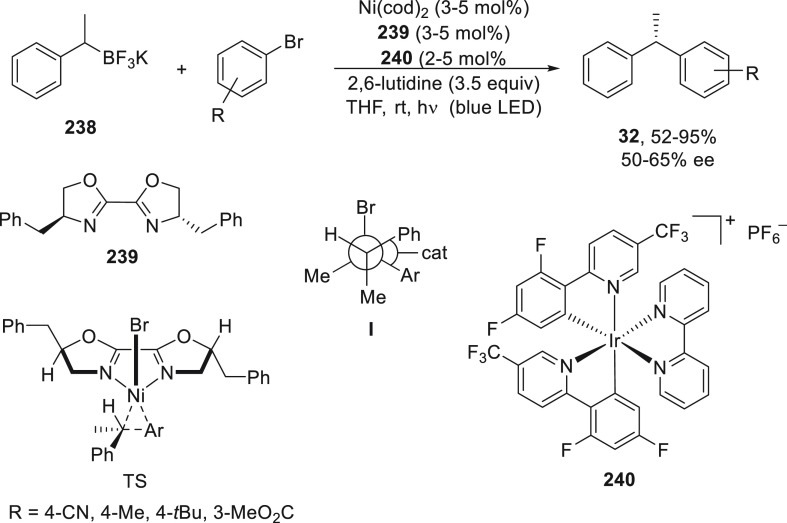

The first enantioconvergent Suzuki reaction of racemic alkylboron reagents with aryl halides was described by Molander and co-workers.137−139 Because of the slow rate of transmetalation of inactivated alkylboron, a photocatalyst 240 and nickel/bis(oxazoline) 239 as dual catalysts enable the cross-coupling of potassium alkyltrifluoroborate 238 with aryl bromides to afford enantioenriched diaryl ethanes 32 in moderate enantioselectivity (Scheme 56). On the basis of DFT calculations, it was proposed to be a DKR of a Ni(III) intermediate wherein the stereodetermining step is the reductive elimination.139 In the lower energy diastereomeric TS, the gauche-like interactions (I) along the forming C–C bond are avoided by rotation of the α-methylbenzyl group.

Scheme 56. Enantioconvergent Photocatalytic and Ni-Catalyzed Suzuki Reactions of Potassium Alkyltrifluoroborate 238 with Aryl Bromides.

In comparison with enantioconvergent cross-coupling reactions of racemic alkyl halides with nucleophiles, only secondary racemic alkylzinc reagents react with electrophiles in an enantioconvergent manner under Ni catalysis. However, other racemic organometals, such as organoboron reagents, equilibrate under the reaction conditions. Recently, another strategy has involved Ni-catalyzed double enantioconvergent cross-coupling of racemic secondary alkylzincs with racemic secondary alkyl electrophiles to generate two stereocenters.

2.4. Reductive Cross-Couplings

An alternative strategy for enantioconvergent C–C bond formation between one electrophile and one organometallic partner is the cross-electrophile coupling reaction.140,141 This reductive cross-coupling (RCC) reaction has been carried out mainly under Ni catalysis between C(sp3) and C(sp2) electrophiles in the presence of a terminal reductant and alternatively under photoredox catalysis. Enantioconvergent related processes, such as decarboxylative cross-coupling reactions and acyl cross-coupling reactions, will be also considered.

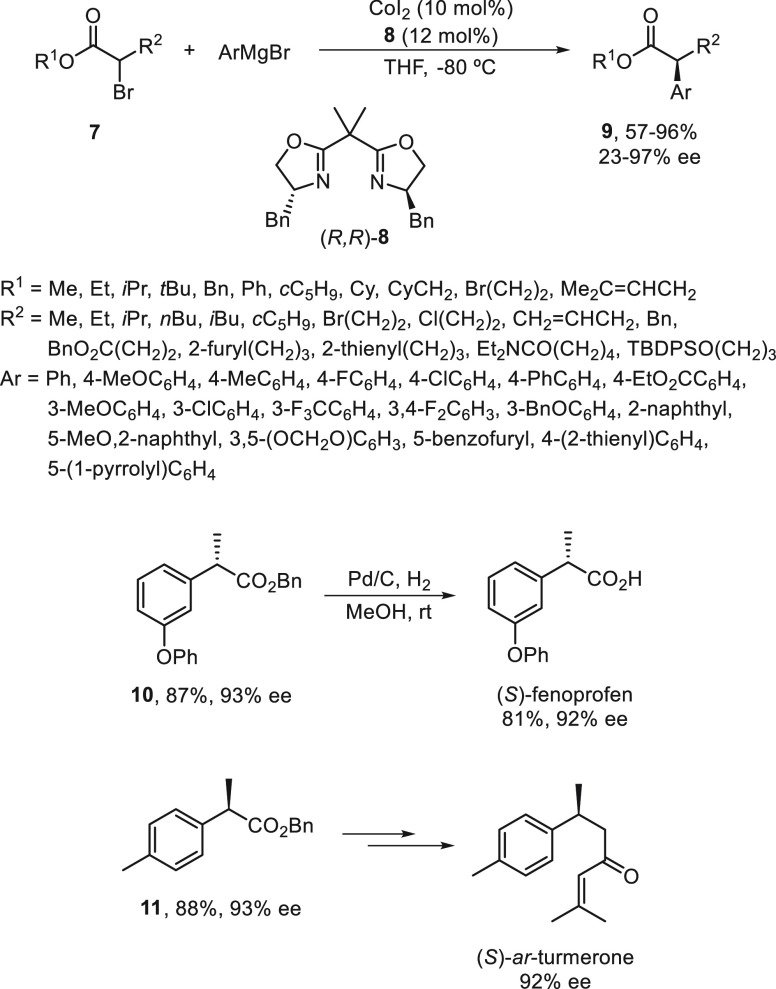

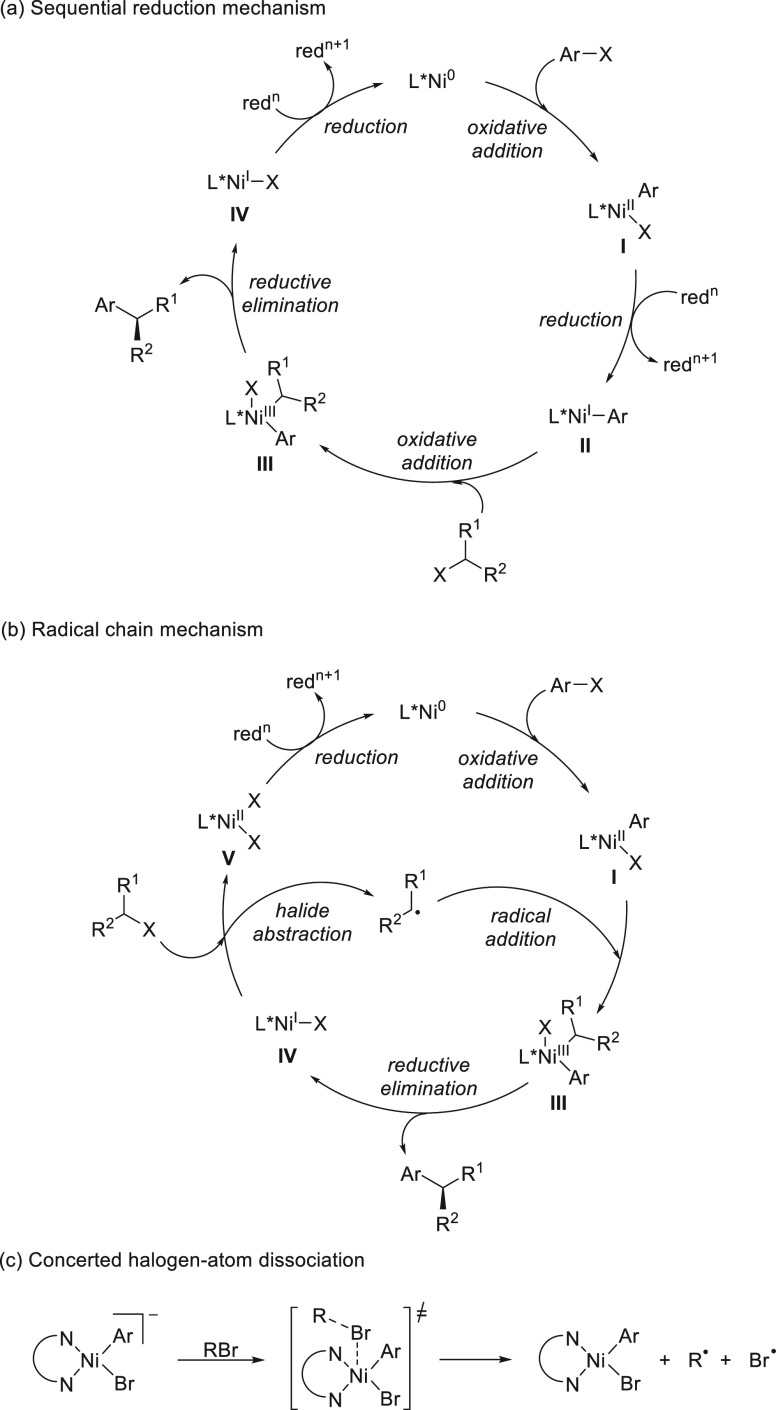

Initial studies on a possible mechanism for conventional RCC reactions are based on a sequential reduction mechanism (Figure 3a) and on a radical chain mechanism (Figure 3b).142,143 In the sequential reduction mechanism, the C(sp2) electrophile undergoes oxidative addition to Ni(0) preferentially to give the Ni(II) complex I, which is then reduced by a metal reductant to Ni(I) intermediate II. This complex II reacts with the C(sp3) electrophile to give the Ni(III) intermediate III, which after reductive elimination provides the enantioenriched product and the Ni(I) complex IV that, after reduction, regenerates the Ni(0) catalyst. In the radical mechanism, intermediate I is formed similarly, which reacts with the alkyl radical to give the Ni(III) complex III, precursor of the final product. Subsequent reductive elimination of III also generates intermediate IV, which undergoes halide abstraction from the alkyl halide to generate the radical and intermediate V. Final reduction of V regenerates the Ni(0) catalyst.

Figure 3.

Proposed mechanisms for conventional reductive cross-coupling reactions.

Diao and co-workers144 recently reported electroanalytical and theoretical studies to elucidate the Ni-mediated radical formation in cross-electrophile coupling reactions. Cyclic voltammetry studies on (bpy)Ni(Mes)Br revealed that instead of outer-sphere electron transfer or two-electron oxidative addition pathways, by using (bpy)Ni catalyst proposed for the halogen-atom abstraction pathway, the inner-sphere electron transfer concerted with halogen-atom dissociation (Figure 3c).

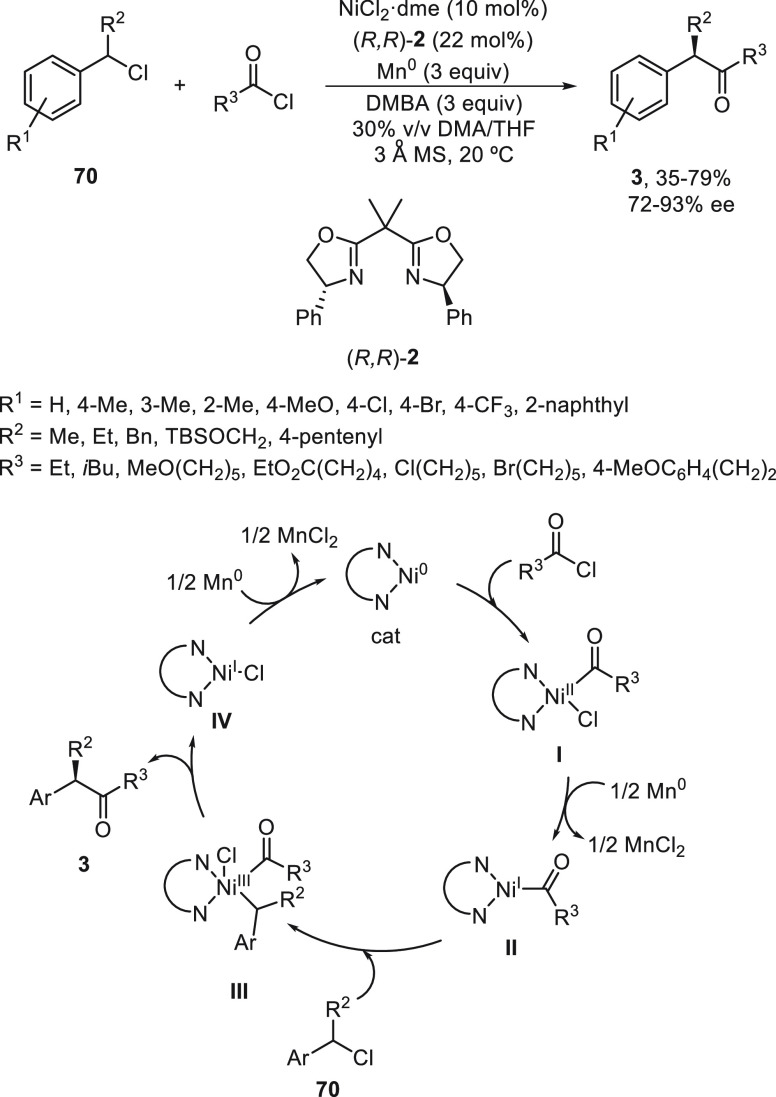

Reisman and co-workers145 reported in 2013 the enantioconvergent acyl cross-coupling of benzylic chlorides 70 with acyl chlorides using NiCl2/bis(oxazoline) Ph-Box (R,R)-2 as catalysts and Mn(0) as the terminal reductant (Scheme 57). The corresponding enantioenriched α-substituted ketones 3 were obtained with moderate to good yields and enantioselectivities in a mixture of THF/DMA and in the presence of dimethylbenzoic acid (DMBA) as additive in order to suppress homocoupling of the benzylic chloride. In the proposed mechanism, intermediate I results from the oxidative addition of the acid chloride, which could be reduced by Mn(0) to give the Ni(I)-acyl species II. Subsequent oxidative addition of a benzyl chloride 70 by a radical process generates the Ni(III) complex III, which undergoes reductive elimination to give intermediate IV and the ketone.

Scheme 57. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Acyl Cross-Coupling of Benzylic Chlorides 70.

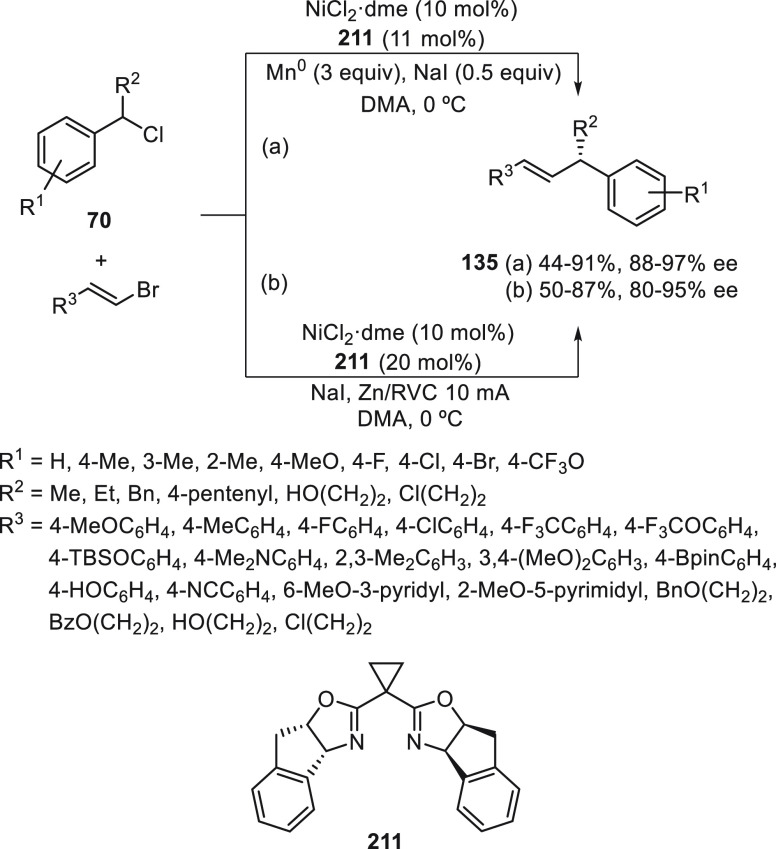

The same group reported the enantioconvergent RCC of benzylic chlorides 70 with alkenyl bromides under NiCl2/bis(oxazoline) 211 and Mn(0) as terminal reductant (Scheme 58a).146 In this case, NaI was an important additive improving the yield of products 135 and decreasing the formation of the dibenzyl homodimer. NaI has been suggested to accelerate the electron-transfer between Mn(0) and Ni or by in situ formation of iodide electrophiles.147 Alkenes 135 were obtained with good yields and enantioselectivities. This process can be driven electrochemically to avoid the use of metal powder as reducing agent.148,149 The corresponding products 135 resulted in up to 87% yield and up to 95% ee (Scheme 58b). Reticulated vitreous carbon (RVC) was used as the cathode, and Zn was used as the sacrificial anode in an undivided cell.148

Scheme 58. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Cross-Coupling of Benzylic Chlorides 70 with Alkenyl Bromides.

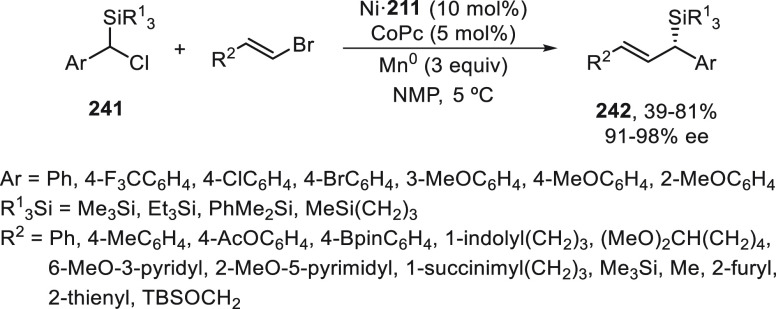

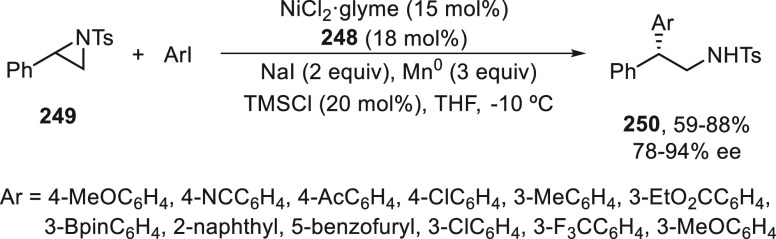

By Ni-catalyzed RCC, Reisman and co-workers150 performed the synthesis of enantioenriched allylic silanes 242 from chloro(arylmethyl)silanes 241 and alkenyl bromides (Scheme 59). In this case, a cobalt phthalocyanine (CoPc) was required for efficient coupling of these bulky benzylic silanes, presumably to favor radical formation.151 This RCC took place in the presence of NiCl2/bis(oxazoline) 211 and Mn(0) as terminal reductant in NMP at 5 °C to provide allylic silanes 242 in moderate to good yields and high enantioselectivities. Stereospecific transformations of these products were applied to the synthesis of (+)-tashiromine.

Scheme 59. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed RCC of Chloro(arylmethyl)silanes 241 with Alkenyl Bromides.

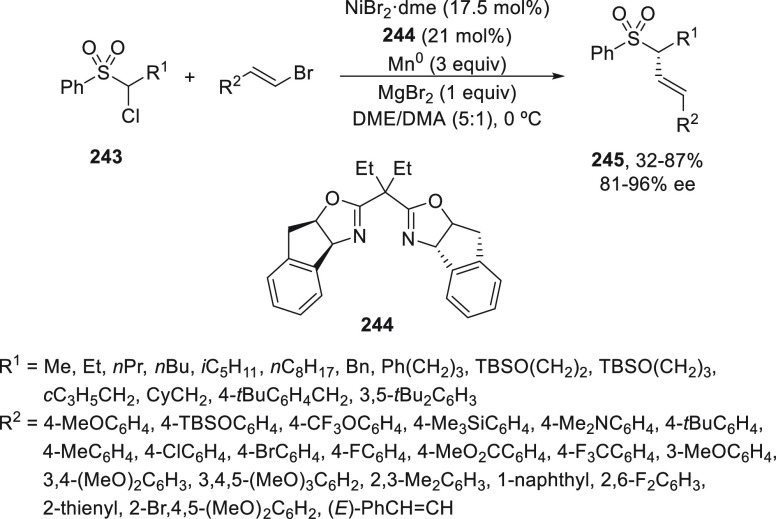

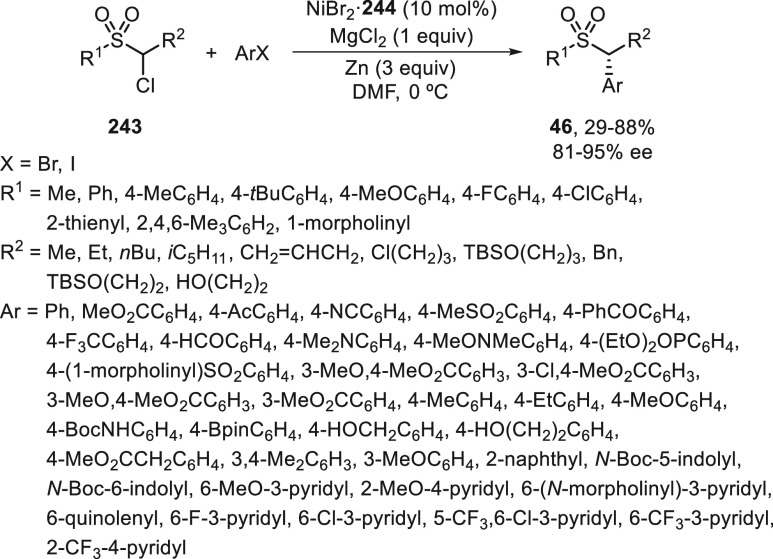

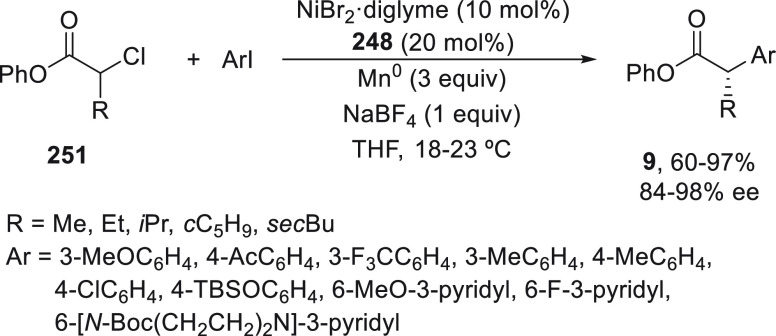

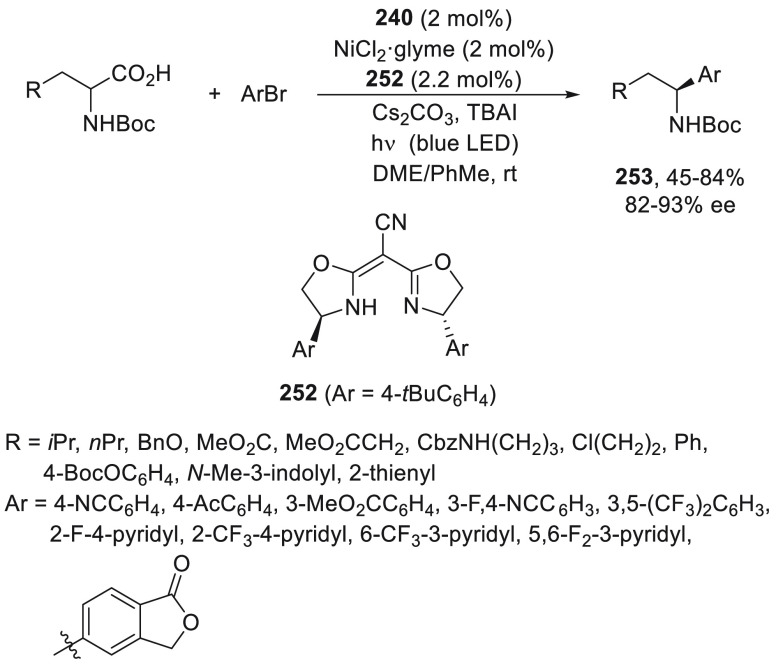

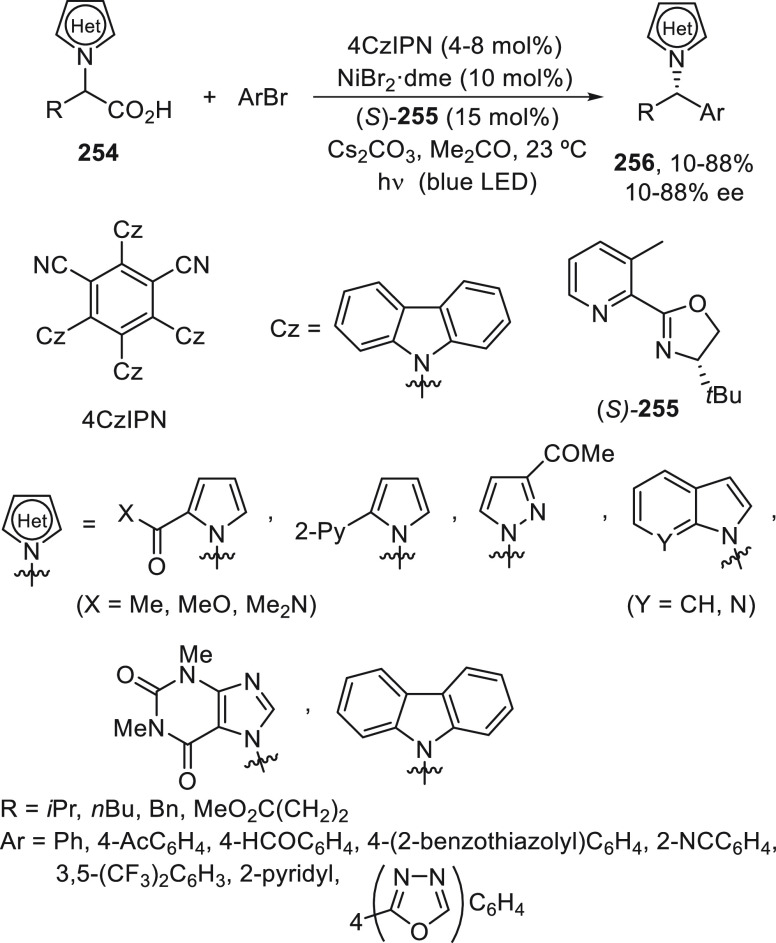

Recently, Sun, Wu, and co-workers152 reported the enantioconvergent reductive alkenylation of α-chloro sulfones 243 under NiBr2/bis(oxazoline) 244 catalysis, Mn as reductant, and MgBr2 as additive (Scheme 60). The resulting enantioenriched allylic sulfones 245 were isolated in up to 87% yield and up to 96% ee and involved radical intermediates.

Scheme 60. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed RCC of α-Chloro Sulfones 243 with Alkenyl Bromides.

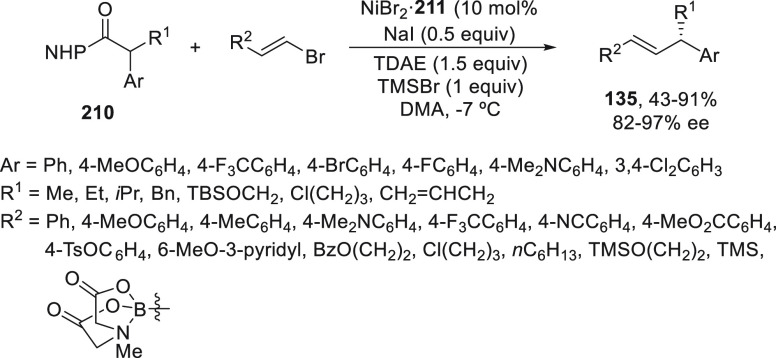

Enantioconvergent reductive alkenylation of N-hydroxyphthalimide (NHP) esters 210 with alkenyl bromides have been carried out by Reisman and co-workers (Scheme 61).153 These esters 210 underwent decarboxylation to generate the corresponding benzylic radicals, which by cross-coupling with alkenyl bromides and using the complex NiBr2/bis(oxazoline) 211 as catalyst furnished enantioenriched alkenes 135 in up to 91% yield and up to 97% ee. The reaction uses tetrakis(N,N-dimethylamino)ethylene (TDAE) as a terminal organic reductant instead of a large excess of metal(0), TMSBr, and NaI as additives. This procedure is an alternative to the use of benzylic chlorides,146 which could be difficult to prepare or unstable, but still gives similar enantioselectivities. According to experimental data, the corresponding mechanism proceeds through a cage-escaped radical.

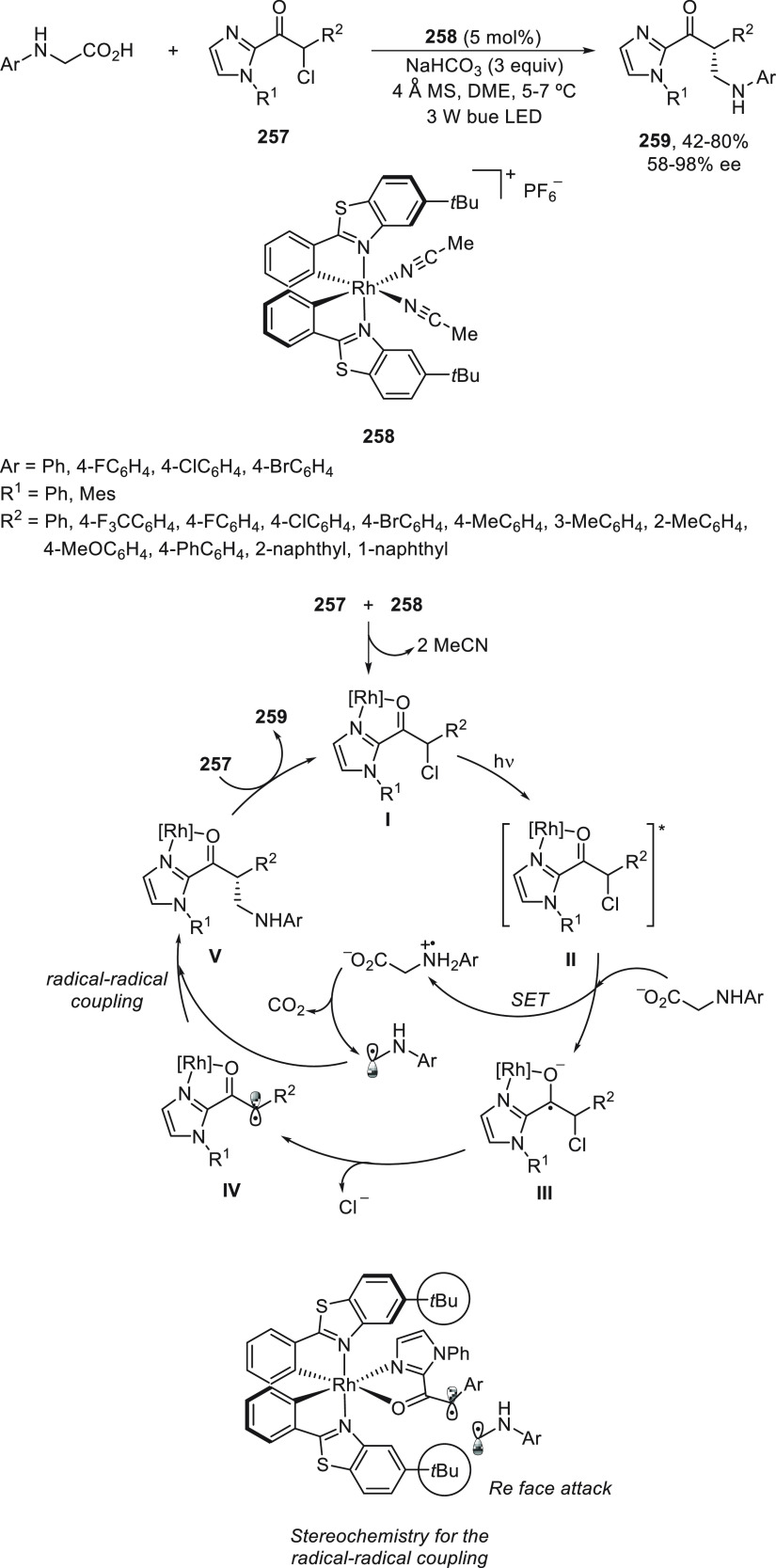

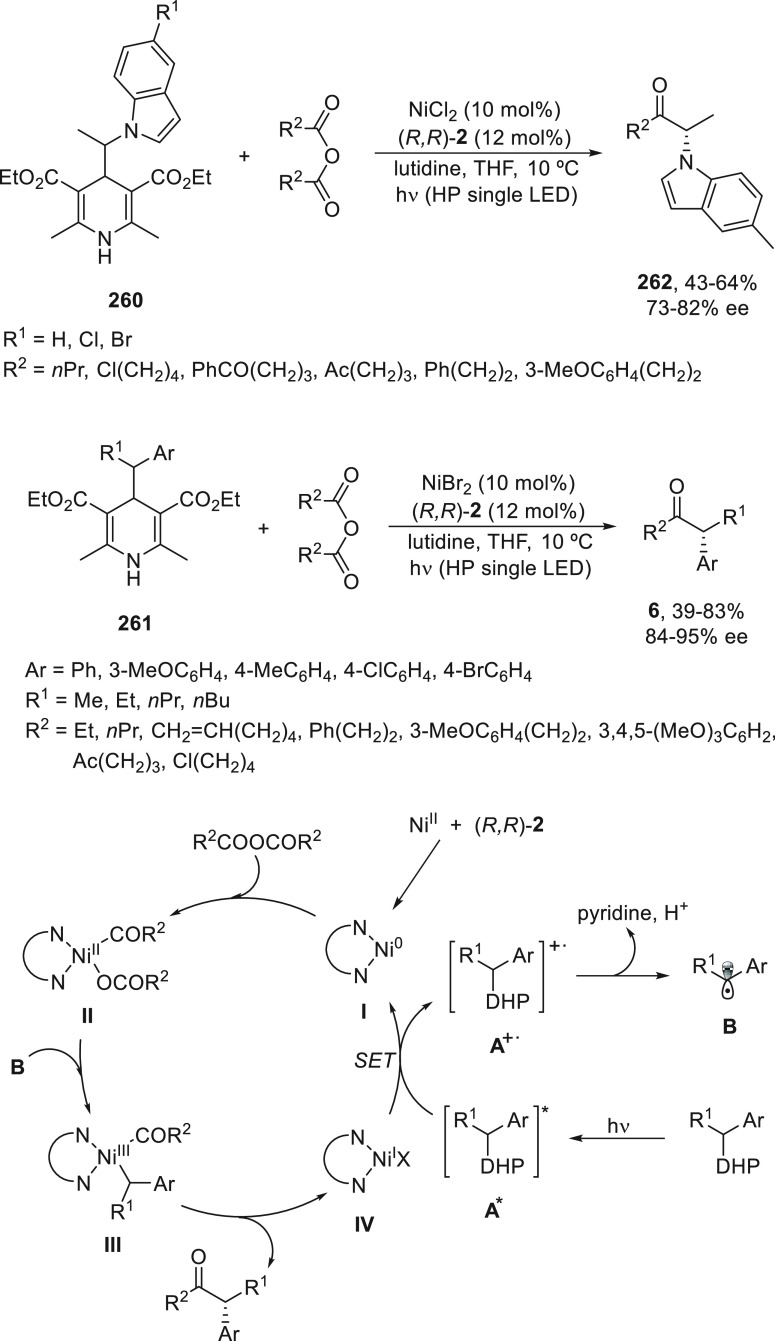

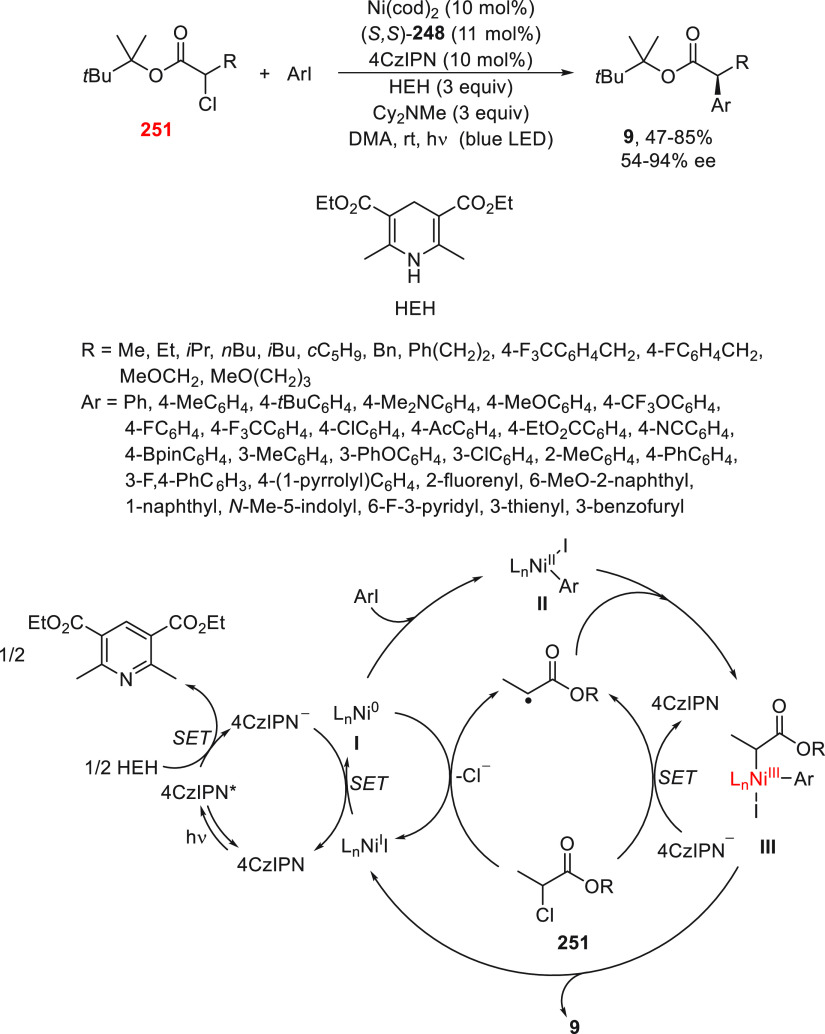

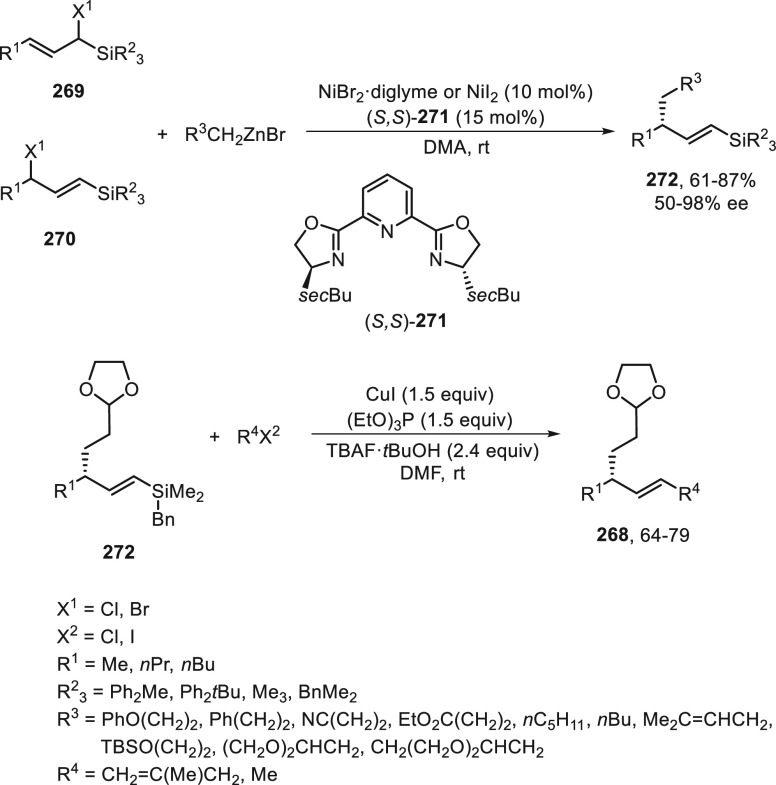

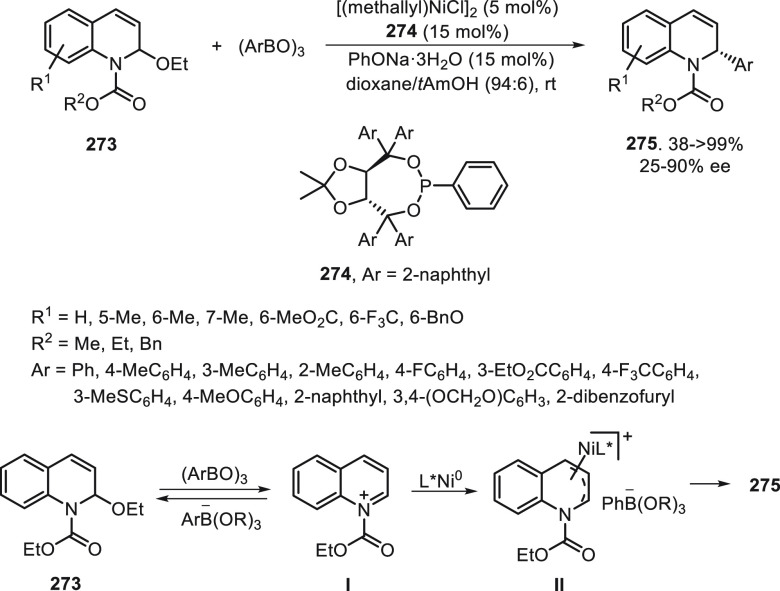

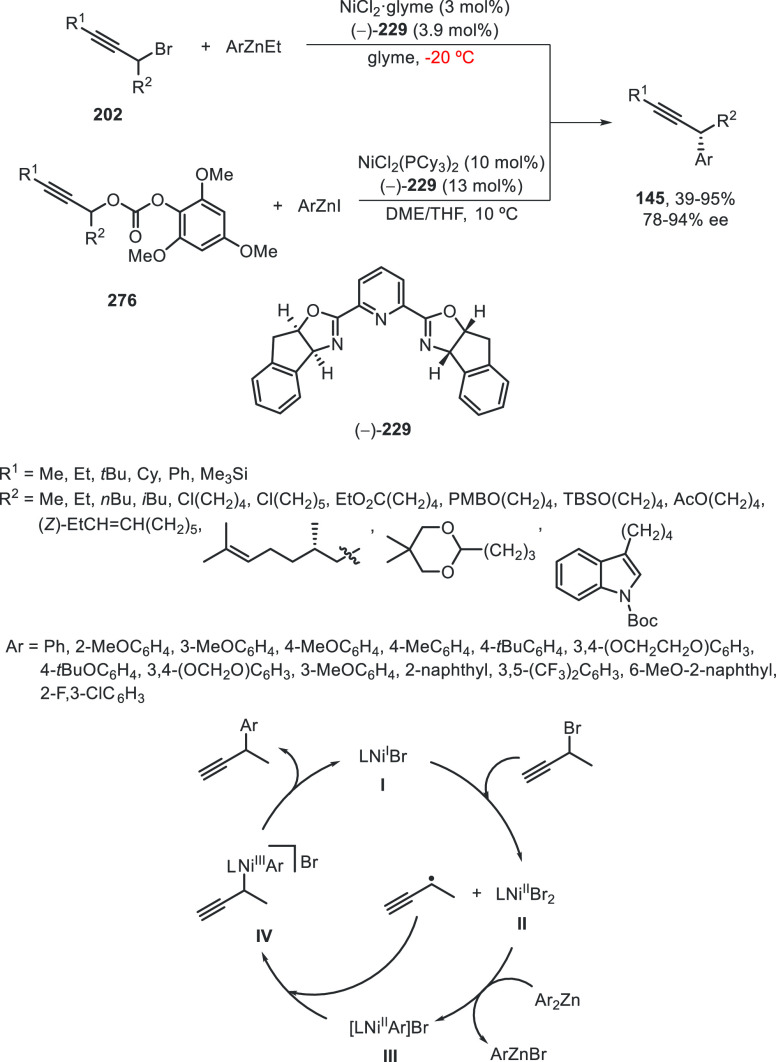

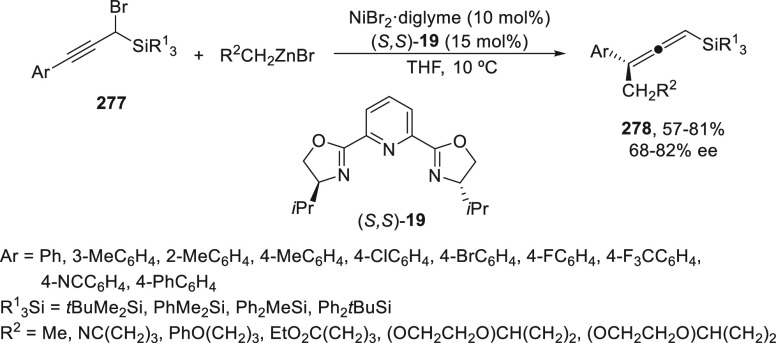

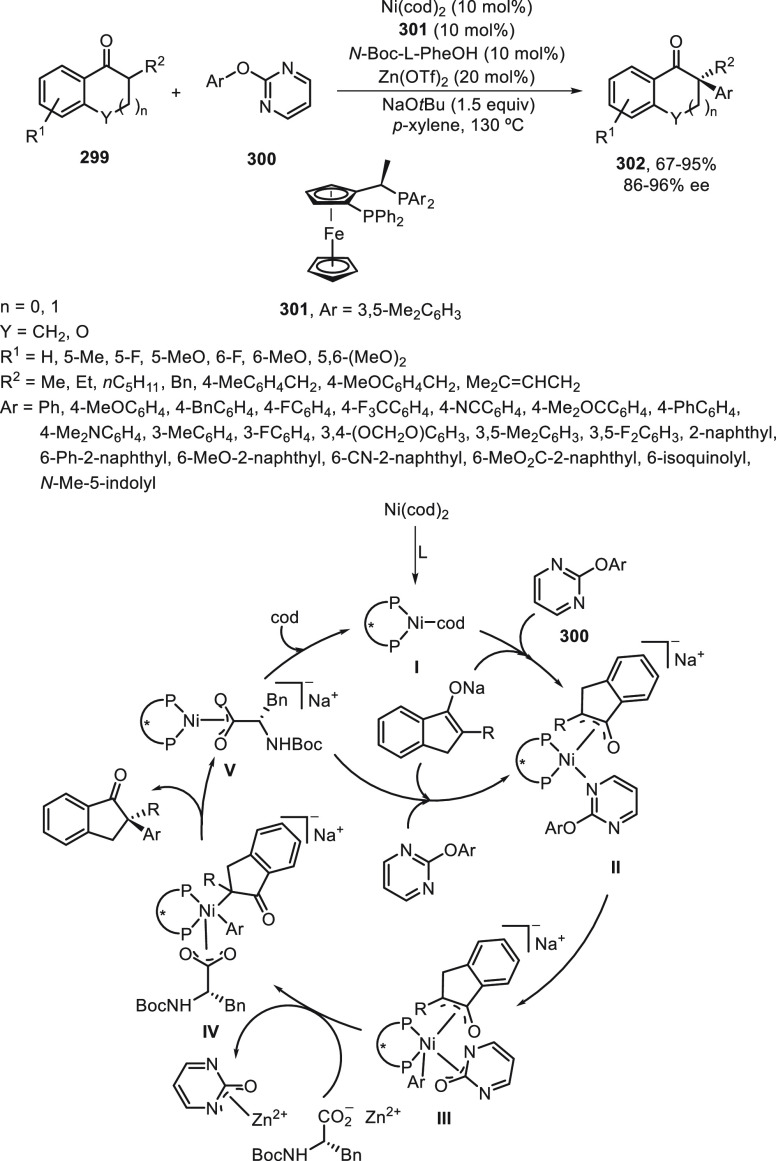

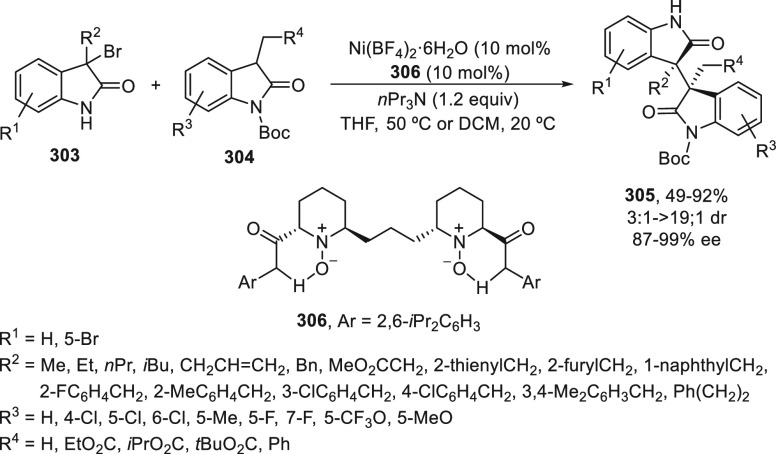

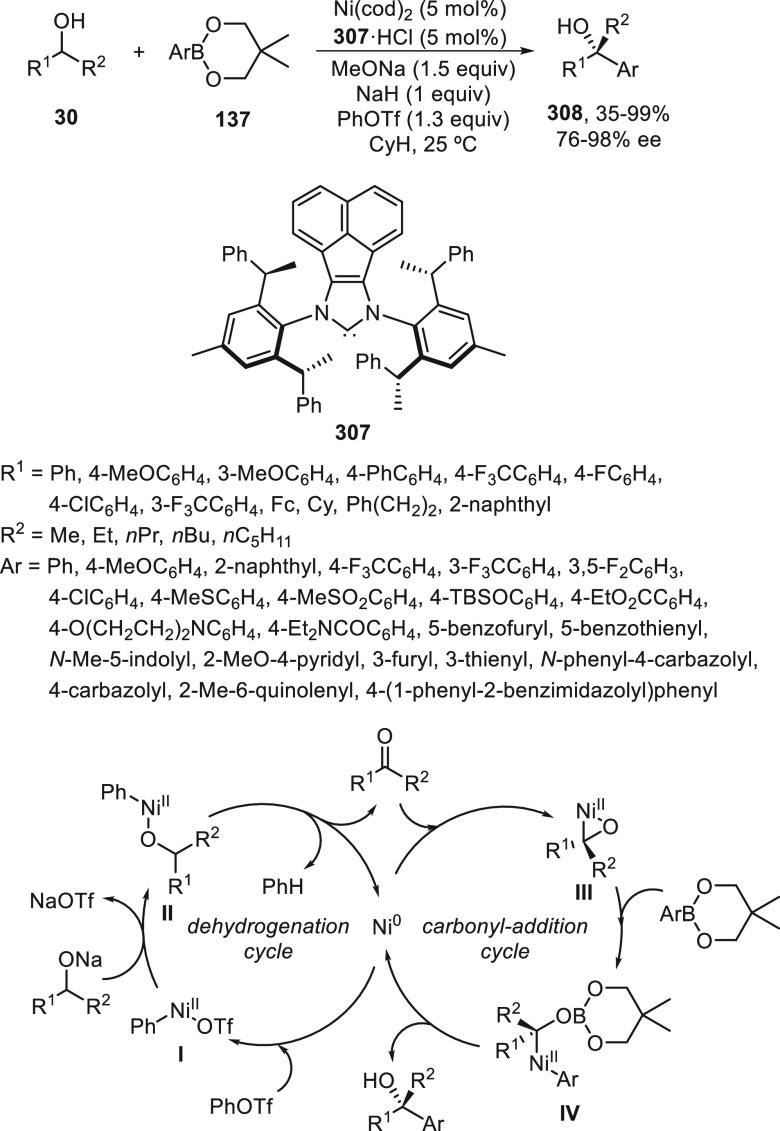

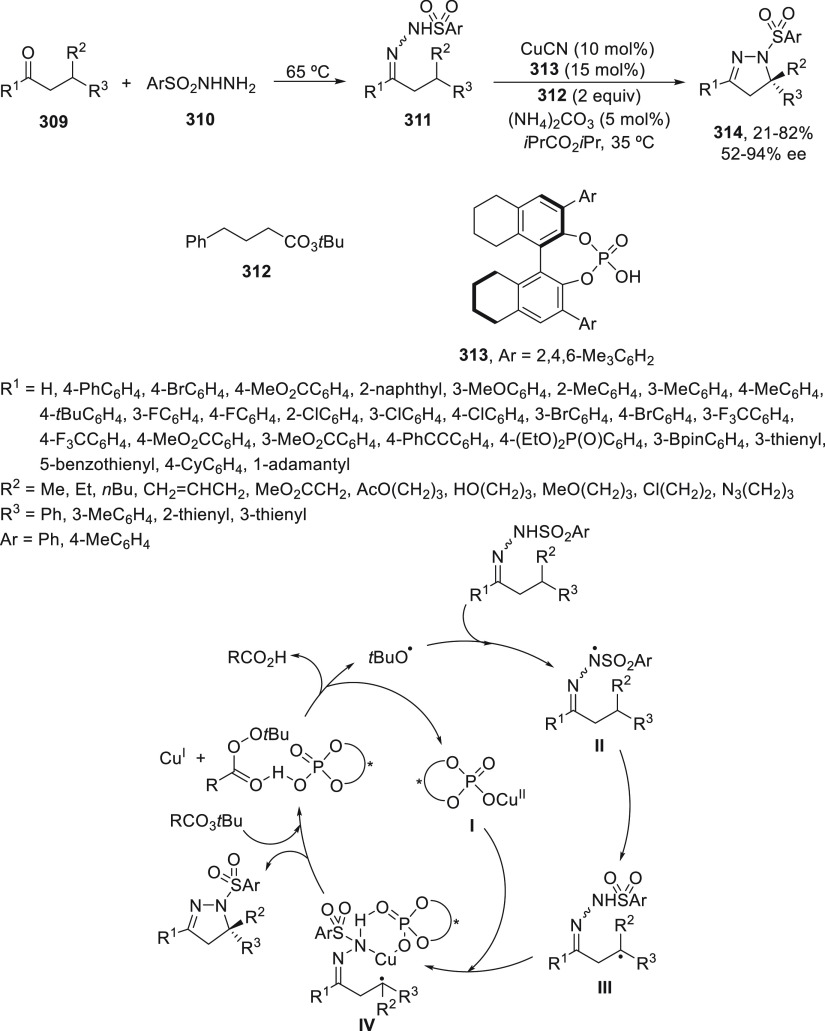

Scheme 61. Enantioconvergent Ni-Catalyzed Reductive Decarboxylative Cross-Coupling of N-Hydroxyphthalimide Esters 210 with Alkenyl Bromides.