Abstract

Despite a clear need for improvement in oral health systems, progress in oral health systems transformation has been slow. Substantial gaps persist in leveraging evidence and stakeholder values for collective problem solving. To truly enable evidence-informed oral health policy making, substantial “know-how” and “know-do” gaps still need to be overcome. However, there is a unique opportunity for the oral health community to learn and evolve from previous successes and failures in evidence-informed health policy making. As stated by the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges, COVID-19 has created a once-in-a-generation focus on evidence, which has fast-tracked collaboration among decision makers, researchers, and evidence intermediaries. In addition, this has led to a growing recognition of the need to formalize and strengthen evidence-support systems. This article provides an overview of recent advancements in evidence-informed health policy making, including normative goals and a health systems taxonomy, the role of evidence-support and evidence-implementation systems to improve context-specific decision-making processes, the evolution of learning health systems, and the important role of citizen deliberations. The article also highlights opportunities for evidence-informed policy making to drive change in oral health systems. All in all, strengthening capacities for evidence-informed health policy making is critical to enable and enact improvements in oral health systems.

Keywords: decision making, evidence-based dentistry, stakeholder participation, citizen science

Why Bother: Tension for Change in Oral Health Systems

The 2021 World Health Organization (WHO) Oral Health Resolution and the subsequent WHO Global Strategy for Oral Health, the FDI Vision 2030 Report, and the Lancet Oral Health Series have been calling for urgent improvements in oral health systems with an overall goal to achieve universal health coverage (UHC) for oral health (Watt et al. 2019; Glick et al. 2021; WHO 2021, 2022a). Given that oral diseases and conditions are largely preventable, stronger emphasis on oral health promotion and oral disease prevention is key to optimize people’s oral health (Watt et al. 2019; Glick et al. 2021; WHO 2021, 2022a). Consequently, the goals set out in the recent WHO Oral Health Action Plan express a clear need for better governance, financial and delivery arrangements, as well as improved implementation strategies within oral health systems; in addition, the cruciality of leveraging evidence to strengthen oral health systems is clearly emphasized (WHO 2023). Note that the WHO (2010) defines a health system as follows:

A health system consists of all the organizations, institutions, resources and people whose primary purpose is to improve health. This includes efforts to influence determinants of health as well as more direct health-improvement activities. The health system delivers preventive, promotive, curative and rehabilitative interventions through a combination of public health actions and the pyramid of health care facilities that deliver personal health care — by both State and non-State actors.

Setting bold goals for oral health systems improvement is important but, how can they actually be achieved? Improving health systems requires a clear understanding of existing problems, identifying options to address them, as well as implementation and evaluation of new approaches with the active participation of multiple stakeholder groups in each of these steps. Until now, however, progress in oral health systems transformation has been very slow (Watt et al. 2019; Listl et al. 2022). There is a lack of a collective problem-solving orientation to leverage evidence for decision making together with citizens/patients, policy makers, service providers, and payers (Listl et al. 2022). To truly approach evidence-informed oral health policy making, substantial “know-how” and “know-do” gaps still need to be overcome.

However, there is a unique opportunity for the oral health community to learn and evolve from previous successes and failures in evidence-informed policy making. Recently, the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges highlighted that COVID-19 has created a once-in-a-generation focus on evidence that has fast-tracked collaboration among decision makers, researchers, and evidence intermediaries; in addition, this has led to a growing recognition of the need to formalize and strengthen evidence-support and evidence-implementation systems (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2022, 2023). For example, the COVID-19 Evidence Network to Support Decision-making (COVID-END) has produced a taxonomy and evidence syntheses to support policy makers, organizational leaders, professionals, and citizens when making decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic (Grimshaw et al. 2020). This also involved an adaptation of the COVID-END taxonomy to the oral health context and an inventory of evidence syntheses with relevance to oral health (Pedra et al. 2021). More generally, however, the oral health field is still lacking a drive for innovative breakthroughs in evidence-informed policy making. By and large, the interface between research and oral health policy making remains unstudied (Verdugo-Paiva et al. 2023).

According to previous work on health care transformation (Plsek 2013), it is pertinent to draw from innovations in other fields when such innovations are not yet present in the field of interest. To this end, the purpose of this article is to highlight recent advancements in evidence-informed policy making (outside the oral health field) and to raise awareness for innovation opportunities to drive positive change in the oral health field. The main focus of this paper is government policy making (not clinical decision making) and specifically government policy making about the health-system arrangements that determine whether the right oral health programs, services, and products get to those who need them. While we emphasize the general relevance of clinical practice guidelines and that their goals should be aligned with overarching policy-making goals, a detailed focus on clinical decision-making processes and clinical practice guidelines is out of the scope of the present article.

Normative Goals and a Taxonomy for (Oral) Health Systems

Normative goals, which are shared by the stakeholders involved in the relevant policy-making context, are an important prerequisite to improving health systems. For example, WHO’s UHC framework is widely used in the global (oral) health policy-making context and seeks to ensure “that all individuals and communities have access to essential, quality health services that respond to their needs and that they can use without suffering financial hardship” (WHO 2023). According to the recent WHO Global Oral Health Status Report, “achieving the highest attainable standard of oral health is a fundamental right of every human being” (WHO 2022b). An example of evolving normative goals is provided by the recent expansion of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Triple Aim (3 aims: improving health outcomes, improving care experiences, keeping per capita costs manageable) beyond a Quadruple Aim (fourth aim: keeping providers engaged) to a Quintuple Aim (fifth aim: advancing health equity) (Berwick et al. 2008; Bodenheimer and Sinsky 2014; Nundy et al. 2022).

Another stepping stone for (oral) health systems improvement is a common understanding of the various health system components. This ensures a comprehensive overview of alternative health systems intervention points, underpins meaningful dialogues between the stakeholders involved, and helps to identify the right type of evidence needed to inform health policy making. Table 1 provides a taxonomy that distinguishes between governance arrangements, financial arrangements, delivery arrangements, and implementation strategies within (oral) health systems (Lavis 2022):

Table 1.

Taxonomy of Governance, Financial and Delivery Arrangements, and Implementation Strategies within (Oral) Health Systems.

| Governance Arrangements | Financial Arrangements | Delivery Arrangements | Implementation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Policy authority

• Centralization/decentralization of policy authority • Accountability of the state sector’s role in financing and delivery • Stewardship of the non–state sector’s role in financing and delivery • Decision-making authority about who is covered and what can or must be provided to them • Corruption protections Organizational authority • Ownership • Management approaches • Accreditation • Networks/multi-institutional arrangements Commercial authority • Licensure and registration requirements • Patents and profits • Pricing and purchasing • Marketing • Sales and dispensing • Commercial liability Professional authority • Training and licensure requirements • Scope of practice • Setting of practice • Continuing competence • Quality and safety • Professional liability • Strike/job action Consumer and stakeholder involvement • Consumer participation in policy and organizational decisions • Consumer participation in system monitoring • Consumer participation in service delivery • Consumer complaints management • Stakeholder participation in policy and organizational decisions (or monitoring) |

Financing systems

• Taxation • Social health insurance • Community-based health insurance • Community loan funds • Private insurance • Health savings accounts (Individually financed) • User fees • Donor contributions • Fundraising Funding organizations • Fee-for-service (funding) • Capitation (funding) • Global budget • Case-mix funding • Indicative budgets (funding) • Targeted payments/penalties (funding) Remunerating providers • Fee-for-service (remuneration) • Capitation (remuneration) • Salary • Episode-based payment • Fundholding • Indicative budgets (remuneration) • Targeted payments/penalties (remuneration) Purchasing products and services • Scope and nature of insurance plans • Lists of covered/reimbursed organizations, providers, services and products • Restrictions in coverage/reimbursement rates for organizations, providers, services and products • Caps on coverage/reimbursement for organizations, providers, services and products • Prior approval requirements for organizations, providers, services and products • Lists of substitutable services and products Incentivizing consumers • Premium (level and features) • Cost sharing • Health savings accounts (third-party contributions) • Targeted payments/penalties (incentivizing consumers) |

How care is designed to meet consumers’ needs

• Availability of care • Timely access to care • Culturally appropriate care • Case management • Package of care/care pathways/disease management • Group care By whom care is provided • System— need, demand, and supply • System—recruitment, retention, and transitions • System—performance management • Workplace conditions—provider satisfaction • Workplace conditions—health and safety • Skill mix—role performance • Skill mix—role expansion or extension • Skill mix—task shifting/substitution • Skill mix—multidisciplinary teams • Skill mix—volunteers or caregivers • Skill mix—communication and case discussion between distant health professionals • Staff—training • Staff—support • Staff—workload/workflow/intensity • Staff—continuity of care • Staff/self—shared decision making • Self-management Where care is provided • Site of service delivery • Physical structure, facilities, and equipment • Organizational scale • Integration of services • Continuity of care • Outreach With what supports is care provided • Health record systems • Electronic health record • Other ICT that support individuals who provide care • ICT that support individuals who receive care • Quality monitoring and improvement systems • Safety monitoring and improvement systems |

Consumer-targeted strategies

• Information or education provision • Behavior change support • Skills and competencies development • (Personal) support • Communication and decision-making facilitation • System participation Provider-targeted strategies • Educational material • Educational meeting • Educational outreach visit • Local opinion leader • Local consensus process • Peer review • Audit and feedback • Reminders and prompts • Tailored intervention • Patient-mediated intervention • Multi-faceted intervention Organization-targeted strategies |

|

Note that the described health-system arrangements and implementation strategies can be operationalized through 4 types of policy instruments: • legal instruments (acts and regulations, self-regulation regimes, and performance-based regulations) • economic instruments (e.g., taxes and fees, public expenditure and loans, public ownership, insurance schemes, and contracts) • voluntary instruments (e.g., standards and guidelines and both formalized partnerships and less formalized networks) • information and education instruments Given that the appropriateness of particular legal and economic instruments varies by political system, it is recommended to focus on arrangements and strategies, not legal and economic instruments |

Adapted from: Lavis (2022). ICT, integrated care teams.

Governance arrangements characterize who can make what decisions in the health system (i.e., policy authority, organizational authority, professional authority, and consumer and stakeholder involvement).

Financial arrangements characterize the raising of revenues, funding of organizations, remunerating providers, purchasing of products and services, and incentivizing consumers.

Delivery arrangements characterize how care is designed, by whom care is provided, where care is provided, and with what support care is provided.

Implementation strategies that are targeted at consumers, providers, or organizations.

Taxonomies are instrumental to drive positive change in (oral) health systems, and the taxonomy presented here (see Table 1) may serve as lever to engage policy makers, citizens, and other actors to operationalize health systems such that the right (oral) health programs, services, and products get to those who need them.

Note that the type of evidence needed to inform policy making (health systems level) is typically distinct from the type of evidence needed for clinical decision making (clinical provider/patient level). While government policy making is concerned with the health-system arrangements that determine whether the right (oral) health programs, services, and products get to those who need them, clinical decision making is concerned with point-of-care choices about specific clinical interventions and treatment products for individual patients. Both types of decision making play an important role, and their goals should be aligned. For example, it seems plausible that the needs-based planning of the oral health workforce (a policy-making task that is also crucial in relation to achieving UHC) should consider the resources required to provide patient care according to clinical practice guidelines (Birch et al. 2021). At the same time, clinical practice guidelines need to be articulated in alignment with overarching policy-making goals, for example, that (oral) health care should be safe, effective, efficient, and equitable. While a detailed focus on clinical practice guidelines is out of the scope of the present article (see above), the general relevance of clinical practice guidelines and their alignment with policy-making goals is emphasized (Frantsve-Hawley et al. 2022).

Matching Evidence and Decision Making: Context Is Everything

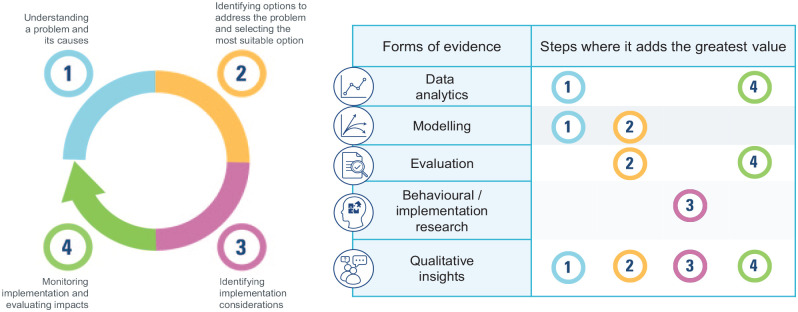

Decision-making processes can generally be broken down into 4 consecutive steps (see Fig. 1, left panel): (1) understanding a problem and its causes, (2) identifying options to address the problem and selecting the most suitable option, (3) identifying implementation considerations, and (4) monitoring implementation and evaluating impacts (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023).

Figure 1.

Stepwise decision-making process (left panel); matching evidence and decision-making steps (right panel). Adapted from Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges (2023).

Challenges in decision making can arise from misalignments in the demand and supply of evidence (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023). On the evidence-demand side, decision makers request evidence to address concrete context-specific questions. On the evidence-supply side, actors can have different forms of evidence available (e.g., data analytics, modeling, evaluation, behavioral/implementation research, qualitative insights). At the interface between the evidence-demand and the evidence-supply sides, fragmented requests and responses can complicate decision making. To respond to decision makers’ questions, the right mix of forms of evidence needs to be matched with the right step in the decision-making process (see Fig. 1, right panel; Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023).

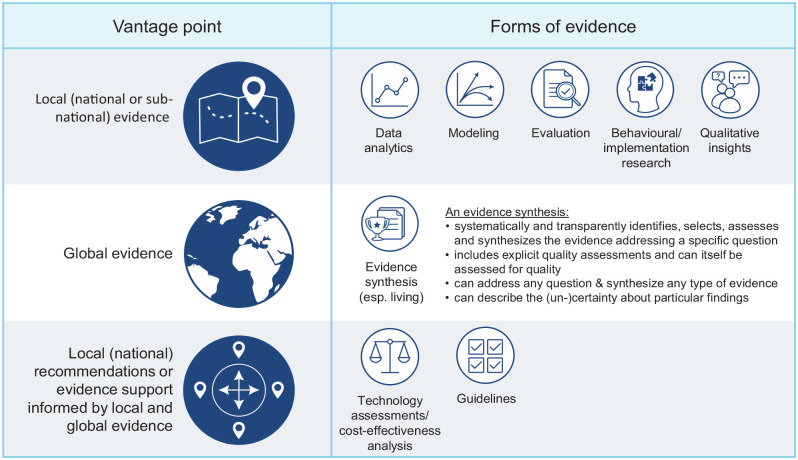

Because local evidence (i.e., what has been learned in a country or region) typically provides a different information value than global evidence (i.e., what has been learned from around the world, including how it varies by groups and contexts), there is an important role for evidence support and evidence implementation systems to combine both local evidence and global evidence (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023). Combining the best of 2 worlds (local and global evidence), evidence support and evidence implementation systems are geared to provide context-specific answers to concrete questions from decision makers. Guidelines and technology assessments/cost-effectiveness analyses are typical types of evidence that integrate both local and global evidence (see Fig. 2). The Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges highlights the formalization and strengthening of country-level evidence-support and evidence-implementation systems and—more generally—the enhancement of the global evidence architecture as key priorities to address societal challenges (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2022, 2023).

Figure 2.

Evidence support systems combine local and global evidence. Adapted from Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges (2023).

For example, countries around the world are increasingly rethinking their health benefit packages to help achieve UHC. The first-ever development of “best buy” interventions on oral health for inclusion in an updated WHO Global Health Action Plan for the prevention and control of NCDs (Appendix 3) is important progress toward achieving UHC (WHO 2021, 2023). But concrete implementation of such interventions still requires policy adoption on the country level. To this end, national health technology assessment (HTA) bodies can leverage evidence-informed deliberative processes (EDP) to enhance legitimate health benefit package design based on deliberation between stakeholders to identify, reflect, and learn about the meaning and importance of values and to interpret available evidence on these values (Oortwijn et al. 2021). Clinical practice guidelines provide a relevant information source to inform such processes. The EDP approach distinguishes 6 practical steps of an HTA process based on observed practices of HTA bodies around the world (Oortwijn et al. 2021):

Installing an advisory committee

Defining decision criteria

Selecting health technologies for HTA

Scoping, assessment, and appraisal (for every health technology)

Communication and appeal

Monitoring and evaluation

The EDP approach also provides recommendations on how 4 elements of legitimacy can be implemented in each of these steps (Oortwijn et al. 2021). First, the core element of EDPs is stakeholder involvement ideally operationalized through stakeholder participation with deliberation. Such stakeholder involvement ensures that all relevant values are considered. Second is evidence-informed evaluation, which allows for the use of research evidence and contributions from stakeholders in terms of their experiences and judgments when further evidence is unavailable. This ensures that relevant evidence is considered. Third, transparency ensures that the deliberative processes, including their objectives, modes of stakeholder involvement, and the decision reached and its related argumentation, is explicitly described and made publicly available. Fourth is appeal, which ensures that a decision can be challenged and revised if new information or insights become available (Oortwijn et al. 2021).

Learning (Oral) Health Systems

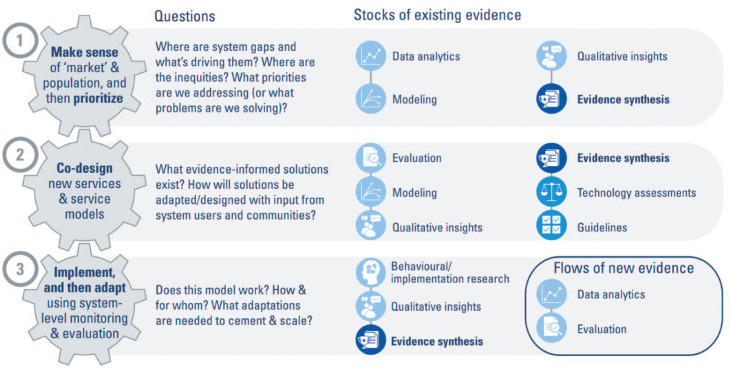

(Oral) health systems can also be strengthened through the use and generation of evidence in cycles of rapid “learning and improving” (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023). Thereby, 3 iterative steps can be distinguished in which such “learning and improving” can take place while using stocks of existing evidence in various forms and producing flows of new evidence (see Fig. 3):

Figure 3.

Learning (oral) health systems evolve from iterative steps of learning and improvement. Adapted from Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges (2023).

Step 1 seeks to “make sense and prioritize” health system gaps, using evidence to provide a birds-eye view.

Step 2 serves to co-design new services and care models, drawing on a wide variety of forms of evidence.

Step 3 implements the new service/care model, applying existing evidence to optimize the implementation while also creating flows of new evidence through monitoring and evaluation.

Over time, iterative journeys through the above steps 1 to 3 can create momentum for a learning (oral) health system, that is, the combination of a health system and a health research system that, at all levels, is anchored on patients’ needs, values, perspectives, and aspirations; driven by timely data and evidence; supported by appropriate decision supports, aligned governance, financial and care-delivery arrangements; and enabled with a culture of and competencies for rapid learning and improvement.

Engaging Citizens for (Oral) Health Systems Improvement

In its most recent update, the Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges emphasizes the relevance of putting evidence at the center of everyday life, that is, turning the focus to citizens as the very people whom policy makers, organizational leaders, professionals, and those working in multilateral organizations are meant to serve (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023). The opportunities of engaging citizens for (oral) health systems improvement are vast (Listl et al. 2022). For example, the Evidence-informed Policy Network has successfully demonstrated how citizen engagement can help to strengthen health systems (Macaulay et al. 2022). Other opportunities for citizen engagement include research priority setting together with citizens (e.g., James Lind Alliance 2018), problem solving in poorer and marginalized groups (Institute of Medicine 1997), HTA processes (Oortwijn et al. 2020), and leveraging patient-reported (oral) health outcomes for quality improvement (Bombard et al. 2018). Not least, the widening use of patient-facing apps and artificial intelligence substantiates the relevance of maximizing the benefits of digital health solutions and minimizing their harms for citizens (Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges 2023).

Opportunities for Evidence-Informed Policy Making to Drive Change in Oral Health Systems

Oral health systems can benefit enormously from better harnessing of evidence and stakeholder values. Windows of opportunity exist across the full array of health system levers (see Table 1): governance arrangements (policy authority, organizational authority, professional authority, consumer and stakeholder involvement), financial arrangements (raising of revenues, funding of organizations, provider remuneration, purchasing of products and services, consumer incentivization), delivery arrangements (how care is designed, by whom care is provided, where care is provided, with what support care is provided), and implementation strategies (targeted at consumers, providers, organizations) (Lavis 2022).

The emergence of the WHO Resolution on Oral Health (WHO 2021) provides insights into the high-level (global) policy-making dynamics and pieces of evidence that were instrumental in the recent recognition of oral health as a pressing issue on the global health policy agenda. In 2021, the foundational WHO Resolution on Oral Health (WHO 2021) was endorsed by the WHO Executive Board and approved by the World Health Assembly. To substantiate the urgency to act on oral heath, the WHO Resolution on Oral Health drew from evidence on the worldwide disease burden of oral conditions (GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators 2018; GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators 2020; IARC 2020), the global economic burden due to poor oral health (Righolt et al. 2018), absenteeism at school and the workplace due to poor oral health (Peres et al. 2019), and associations of poor oral health with other conditions such as, for example, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases (Seitz et al. 2019). Eventually, the WHO Resolution paved the way for the subsequent approval of the WHO Oral Health Strategy (WHO 2022a) and the WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan (WHO 2023).

The current WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan (WHO 2023) describes targets to achieve UHC for oral health and to reduce the oral disease burden by 2030 (see overview in Table 2), which could be operationalized through evidence-informed policy-making processes as outlined in the sections above. Such processes could drive positive change in oral health governance (e.g., strengthening the capacity of oral health units at ministries of health), (oral) health promotion and oral disease prevention (e.g., policies and regulations to limit free sugars intake), health workforce models (e.g., integrated care teams with new mixes of oral health professionals and other health professionals), oral health care (e.g., agreement on national UHC benefit packages and the related development of “best buy” interventions for oral health), creating and updating oral health national guidelines, oral health information systems (e.g., integration of dental and medical patient records), and oral health research agendas (e.g., national oral health research priorities to focus on public health and population-based interventions with a clear focus on knowledge translation). As such, the goals described in the WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan provide normative directionality that can be leveraged through evidence-informed policy making toward positive change in oral health systems.

Table 2.

WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan (WHO 2023): Levers for Evidence-Informed Policy Making.

|

Overarching global targets:

UHC for oral health: By 2030, 75% of the global population will be covered by essential oral health care services to ensure progress toward UHC for oral health. Reduce oral disease burden: By 2030, the global prevalence of the main oral diseases and conditions over the life course will show a relative reduction of 10%. | |

|---|---|

| Strategic Objectives | Global Targets |

| Oral health governance: Improve political and resource commitment to oral health, strengthen leadership, and create win-win partnerships within and outside the health sector. |

National leadership for oral health: By 2030, 80% of countries will have an operational national oral health policy, strategy, or action plan and dedicated staff for oral health at the Ministry of Health. Environmentally sound practices: By 2030, 90% of countries will have implemented 2 or more of the recommended measures to phase down dental amalgam in line with the Minamata Convention on Mercury or will have phased it out. |

| Oral health promotion and oral disease prevention: Enable all people to achieve the best possible oral health and address the social and commercial determinants and risk factors of oral diseases and conditions. |

Reduction of sugar consumption: By 2030, 70% of countries will have implemented a tax on sugar-sweetened beverages. Optimal fluoride for population oral health: By 2030, at least 50% of countries will have national guidance to ensure optimal fluoride delivery for the population. |

| Health workforce: Develop innovative workforce models and revise and expand competency-based education to respond to population oral health needs. | Innovative workforce model for oral health: By 2030, at least 50% of countries will have an operational national health workforce strategy that includes workforce trained to respond to population oral health needs. |

| Oral health care: Integrate essential oral health care and ensure related financial protection and essential supplies in primary health care. |

Oral health in primary care: By 2030, 80% of countries will have oral health care services available in primary care facilities of the public health sector. Essential dental medicines: By 2030, at least 50% of countries will have included the WHO essential dental medicines in the national essential medicines list. |

| Oral health information systems: Enhance surveillance and health information systems to provide timely and relevant feedback on oral health to decision makers for evidence-based policy making. | Integrated oral health indicators: By 2030, 75% of countries will have included oral health indicators in their national health information systems in line with the monitoring framework of the global oral health action plan. |

| Oral health research agendas: Create and continuously update context and needs-specific research that is focused on the public health aspects of oral health. | Research in the public interest: By 2030, at least 20% of countries will have a national oral health research agenda focused on public health and population-based interventions. |

Further examples illustrate the relevance and recent progress toward evidence-informed (oral) health policy making:

Policy makers’ perceived barriers and facilitators in the use of research evidence in oral health policies and guidelines: In light of the largely unstudied interface between research and oral health policy making, a recent study protocol describes a qualitative research approach to assess policy makers’ perceived needs, barriers, and facilitators in using research evidence to inform policies in oral health (Verdugo-Paiva et al. 2023).

Better financing models for oral health systems: Major challenges exist in the financing arrangements for oral health systems. Although largely preventable, oral diseases affect about half of the population and are the third most expensive diseases to treat in the EU (Listl et al. 2019, 2021). In deviation from the UHC goal, many people cannot afford to access essential oral health care (Thomson et al. 2019). To address this complex systems problem, the EU-funded PRUDENT (Prioritization, incentives and Resource use for sUstainable DENTistry) project aims to develop and implement an innovative and context-adaptive framework to optimize financing models for oral health systems (Listl et al. 2023a). Using a mixed-methods research approach, PRUDENT aims to (1) co-develop oral health systems performance indicators and implement them in a Europe-wide monitoring framework, (2) conduct real-world and lab experiments to identify improved financing mechanisms for oral health systems, and (3) leverage regulatory learning, needs-adaptive resource planning, and deliberative priority setting to optimize the financing within oral health systems. The knowledge gained will be compiled into policy briefs and decision aid tools for concretely actionable and context-adaptive improvement of financing arrangements in oral health systems (Listl et al. 2023a).

Quality improvement: While the detrimental impacts of compromised quality and safety of oral health care are vast, quality improvement efforts in the oral health field lag behind other fields of medicine (Byrne and Tickle 2019). Drawing from previous evidence from other areas of medicine, successful quality improvement integrates across multiple stakeholders and multiple sectors (Kruk et al. 2018). To this end, the DELIVER (DELiberative ImproVEment of oRal care quality) project aims to enhance the quality of oral care through collective problem identification and problem solving together with policy makers, citizens (including patients), providers, and payers (Listl et al. 2023b). DELIVER co-develops and co-produces innovative quality improvement approaches in 3 phases. The first phase involves situational analysis, consenting of core quality indicators, and development of an EU-wide monitoring framework for the quality of oral health care. The second phase involves in-depth analysis of select quality improvement approaches: (1) quality improvement in dental practices based on Patient Reported Outcome & Experience Measures (PROMs/PREMs) (2) community-based quality improvement for vulnerable groups, and (3) quality-oriented commissioning of oral health services. Finally, in the third phase, the findings from the first and second phases are merged into the DELIVER Quality Toolkit with manuals and digital tools to support the implementation of oral care quality improvement (Listl et al. 2023b).

Policy making to reduce sugar consumption: Dietary sugars are central in the etiology of dental caries, and the WHO Global Oral Health Action Plan states limiting the intake of free sugars as a key goal (Moores et al 2022; WHO 2023). Ample evidence suggests that sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) taxes can reduce sugar consumption (Andreyeva 2022; Hajishafiee et al. 2023). However, a recent synthesis of real-world SSB tax evaluations and policy development case studies highlights that SSB tax policy making depends on various aspects and not just evidence about the (oral) health impacts of SSB tax alone (Hagenaars et al. 2021). Drawing from the Health Policy Triangle framework (Buse et al. 2012), policy content, context, and process (along with the viewpoints of multiple stakeholders) are decisive for SSB tax policy making (Hagenaars et al. 2021). For policy making to reduce sugar consumption, the oral health community can learn important lessons from other areas such as policy making to tackle tobacco use (Hagenaars et al. 2021).

Integration of medical and oral health systems: Leveraging evidence on mutual interdependencies between diabetes and periodontal diseases as well as the impact of periodontal treatment on diabetes-related health care costs (Nasseh et al. 2017; D’Aiuto et al. 2018; Sanz et al. 2018; Choi et al. 2020; Smits et al. 2020; Blaschke et al. 2021), the German Innovation Fund project DigIn2Perio (Digitally Integrated Type-2 Diabetes and Periodontitis Care) evaluates the implementation of a new integrated care model for persons with diabetes and periodontitis. In primary care practices, persons with diabetes are screened for periodontitis risk; in dental practices, persons with periodontitis are screened for diabetes risk. Increased risk scores lead to mutual referrals between primary and oral health care providers and initiation of integrated care pathways (supported by electronic information exchange). Impact and process evaluations will generate a flow of new evidence that can inform policy making about the potential adoption of the new care model as standard care within the statutory health insurance in Germany (DigIn2Perio 2022).

COVID-19 Evidence Network to Support Decision-making (COVID-END): As already mentioned in the beginning of this article, the COVID-END network has produced an oral health inventory that comprises a taxonomy and evidence syntheses most relevant to the types of oral health–related decisions faced by policy makers, organizational leaders, professionals, and citizens during the COVID-19 pandemic. The COVID-END oral health inventory is described as a one-stop shop that provides relevant, scientific evidence-based information in an easy-to-use way about COVID-19, oral health, and health systems. The inventory comprises evidence-based answers about public health measures, the clinical management of COVID-19 and related health issues, health-system arrangements as well as economic and social responses, and dentistry education. These answers are briefing notes summarized from studies such as systematic reviews, meta-analysis, living systematic reviews, rapid reviews, evidence synthesis, scoping reviews, economic analyses, and PROSPERO protocols (Pedra et al. 2021).

The examples above also highlight the important role of public research funding agencies for strengthening capacities for evidence-informed (oral) health policy making.

Call for Action and Next Steps

In this article, we have highlighted the opportunities and challenges for evidence-informed (oral) health policy making to drive positive change in oral health systems. In light of the growing recognition of the relevance of evidence-informed policy making, we call for (oral) health policy makers, the (oral) health research community, public research funding agencies, civil society organizations, (oral) health professionals, and payors to support and embrace the positive evolution of this innovative paradigm at the intersect between research and policy making. Strengthening capacities for evidence-informed health policy making is critical to drive positive change in oral health systems.

Author Contributions

S. Listl, R. Baltussen, J.N. Lavis, contributed to data conception and design, drafted and critically revised the manuscript; A. Carrasco-Labra, F.C. Carrer, contributed to data conception and design, critically revised the manuscript. All authors gave their final approval and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: A. Carrasco-Labra  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3546-3526

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3546-3526

F.C. Carrer  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3745-2759

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3745-2759

References

- Andreyeva T, Marple K, Marinello S, Moore TE, Powell LM. 2022. Outcomes following taxation of sugar-sweetened beverages: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 5(6):e2215276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. 2008. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 27(3):759–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch S, Ahern S, Brocklehurst P, Chikte U, Gallagher J, Listl S, Lalloo R, O’Malley L, Rigby J, Tickle M, et al. 2021. Planning the oral health workforce: time for innovation. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 49(1):17–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaschke K, Hellmich M, Samel C, Listl S, Schubert I. 2021. The impact of periodontal treatment on healthcare costs in newly diagnosed diabetes patients: evidence from a German claims database. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 172:108641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. 2014. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 12(6):573–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, Onate K, Denis JL, Pomey MP. 2018. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 13(1):98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buse K, Mays N, Walt G. 2012. The health policy framework. In: Buse K, Mays N, Walt G, editors. Making health policy. Berkshire (UK): Open University Press. p. 4–19. [Google Scholar]

- Byrne M, Tickle M. 2019. Conceptualising a framework for improving quality in primary dental care. Br Dent J. 227(10):865–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi SE, Sima C, Pandya A. 2020. Impact of treating oral disease on preventing vascular diseases: a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis of periodontal treatment among patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 43(3):563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Aiuto F, Gkranias N, Bhowruth D, Khan T, Orlandi M, Suvan J, Masi S, Tsakos G, Hurel S, Hingorani AD, et al.; TASTE Group. 2018. Systemic effects of periodontitis treatment in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 12 month, single-centre, investigator-masked, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 6(12):954–965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DigIn2Perio. 2022. Digitally integrated type-2 diabetes and periodontitis care [accessed 2023 Jan 31]. https://innovationsfonds.g-ba.de/projekte/neue-versorgungsformen/digin2perio-digital-integrierte-versorgung-von-diabetes-mellitus-typ-2-und-parodontitis.508.

- Frantsve-Hawley J, Abt E, Carrasco-Labra A, Dawson T, Michaels M, Pahlke S, Rindal DB, Spallek H, Weyant RJ. 2022. Strategies for developing evidence-based clinical practice guidelines to foster implementation into dental practice. J Am Dent Assoc. 153(11):1041–1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. 2018. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 392(10159):1789–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators. 2020. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease 2017 Study. J Dent Res. 99(4):362–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick M, Williams DM, Ben Yahya I, Bondioni E, Cheung WWM, Clark P, Jagait CK, Listl S, Mathur MR, Mossey P, et al. 2021. Vision 2030: delivering optimal oral health for all. Geneva: FDI World Dental Federation; [accessed 2023 Jun 20]. https://www.fdiworlddental.org/vision2030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges. 2022. The evidence commission report: a wake-up call and path forward for decision-makers, evidence intermediaries, and impact-oriented evidence producers. Hamilton (Canada): McMaster Health Forum; [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://www.mcmasterforum.org/networks/evidence-commission. [Google Scholar]

- Global Commission on Evidence to Address Societal Challenges. 2023. Evidence commission update 2023: strengthening domestic evidence-support systems, enhancing the global evidence architecture, and putting evidence at the centre of everyday life. Hamilton (Canada): McMaster Health Forum; [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://www.mcmasterforum.org/networks/evidence-commission/domestic-evidence-support-systems. [Google Scholar]

- Grimshaw JM, Tovey DI, Lavis JN, on behalf of COVID-END. 2020. COVID-END: an international network to better co-ordinate and maximize the impact of the global evidence synthesis and guidance response to COVID-19. In: Collaborating in response to COVID-19: editorial and methods initiatives across Cochrane. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12(suppl 1):4–8 [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD202002/full. [Google Scholar]

- Hagenaars LL, Jeurissen PPT, Klazinga NS, Listl S, Jevdjevic M. 2021. Effectiveness and policy determinants of sugar-sweetened beverage taxes. J Dent Res. 100(13):1444–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajishafiee M, Kapellas K, Listl S, Pattamatta M, Gkekas A, Moynihan P. 2023. Effect of sugar-sweetened beverage taxation on sugars intake and dental caries: an umbrella review of a global perspective. BMC Public Health. 23(1):986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IARC International Agency for Research on Cancer. Global Cancer Observatory. Lip, oral cavity, December 2020. [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://gco.iarc.fr/today/data/factsheets/cancers/1-Lip-oral-cavity-fact-sheet.pdf

- Institute of Medicine. 1997. Improving health in the community: a role for performance monitoring. Washington (DC): National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James Lind Alliance. 2018. Priority setting partnerships: oral and dental health [accessed 2023 Jun 20]. http://www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/priority-setting-partnerships/oral-and-dental-health/.

- Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, Adeyi O, Barker P, Daelmans B, Doubova SV, et al. 2018. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 6(11):e1196–e1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavis JN. 2022. Health systems evidence: taxonomy of governance, financial and delivery arrangements, and implementation strategies within health systems. Hamilton (Canada): McMaster Health Forum; [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default-source/resources/16_hse_taxonomy.pdf?sfvrsn=281c55d5_7. [Google Scholar]

- Listl S, van Ardenne O, Grytten J, Gyrd-Hansen D, Melo P, Nemeth O, Tubert-Jeannin S, Vassallo P, van Veen EB, Vernazza C, Waitzberg R, Winkelmann J, Woods N. 2023. a Prioritization, Incentives and Resource Use for Sustainable Dentistry: the EU PRUDENT project. JDR Clinical and Translational Research. doi: 10.1177/23800844231189485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listl S, Grytten JI, Birch S. 2019. What is health economics? Community Dent Health. 36(4):262–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listl S, Bostanci N, Byrne M, Eigendorf J, van der Heijden G, Lorenz M, Melo P, Rosing K, Vassallo P, van Veen EB. 2023. b. Deliberative Improvement of Oral Care Quality: the Horizon Europe DELIVER project. JDR Clinical and Translational Research. doi: 10.1177/23800844231189484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listl S, Lavis JN, Cohen LK, Mathur MR. 2022. Engaging citizens to improve service provision for oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 100(5):294–294A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Listl S, Quiñonez C, Vujicic M. 2021. Including oral diseases and conditions in universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 99(6):407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay B, Reinap M, Wilson MG, Kuchenmüller T. 2022. Integrating citizen engagement into evidence-informed health policy-making in eastern Europe and central Asia: scoping study and future research priorities. Health Res Policy Syst. 20(1):11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moores CJ, Kelly SAM, Moynihan PJ. 2022. Systematic review of the effect on caries of sugars intake: ten-year update. J Dent Res. 101(9):1034–1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasseh K, Vujicic M, Glick M. 2017. The relationship between periodontal interventions and healthcare costs and utilization. Evidence from an integrated dental, medical, and pharmacy commercial claims database. Health Econ. 26(4):519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. 2022. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. JAMA. 327(6):521–522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oortwijn W, Jansen M, Baltussen R. 2020. Use of evidence-informed deliberative processes by health technology assessment agencies around the globe. Int J Health Policy Manag. 9(1):27–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oortwijn W, Jansen M, Baltussen R. 2021. Evidence-informed deliberative processes for health benefit package design – part II: a practical guide. Int J Health Policy Manag. 11(10):2327–2336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedra RC, Ferreira LCB, Martins R, Bello GV, Carrer FCdA, Cherian SA, Grimshaw J, Moat K, Lavis J. 2021. COVID-END / Covid-19 Evidence Network to support Decision-making / Oral Health: a team of passionate people working to address COVID-19 oral health challenges by an innovative approach. São Paulo (Brazil): EvipOralHealth/University of São Paulo/Pushpagiri College of Dental Sciences; [accessed 2023 Jun 28]. https://www.mcmasterforum.org/docs/default-source/covidend/covid-end-oral-health.pdf?sfvrsn=27b2438_5. [Google Scholar]

- Peres MA, Macpherson LMD, Weyant RJ, Daly B, Venturelli R, Mathur MR, Listl S, Celeste RK, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Kearns C, et al. 2019. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge. Lancet. 394(10194):249–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plsek PE. 2013. Virginia Mason, lean, and innovation. In: Plsek PE, editor. Accelerating health care transformation with lean and innovation: the Virginia Mason experience. Productivity Press. p. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- PRUDENT. 2023. Prioritization, incentives and resource use for sustainable dentistry. doi: 10.3030/101094366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Righolt AJ, Jevdjevic M, Marcenes W, Listl S. 2018. Global-, regional-, and country-level economic impacts of dental diseases in 2015. J Dent Res. 97(5):501–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz M, Ceriello A, Buysschaert M, Chapple I, Demmer RT, Graziani F, Herrera D, Jepsen S, Lione L, Madianos P, et al. 2018. Scientific evidence on the links between periodontal diseases and diabetes: consensus report and guidelines of the Joint Workshop on Periodontal Diseases and Diabetes by the International Diabetes Federation and the European Federation of Periodontology. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 137:231–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seitz MW, Listl S, Bartols A, Schubert I, Blaschke K, Haux C, Van Der Zande MM. 2019. Current knowledge on correlations between highly prevalent dental conditions and chronic diseases: an umbrella review. Prev Chronic Dis. 16:E132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smits KPJ, Listl S, Plachokova AS, Van der Galien O, Kalmus O. 2020. Effect of periodontal treatment on diabetes-related healthcare costs: a retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 8(1):e001666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson S, Cylus J, Evetovitset T. 2019. Can people afford to pay for health care? WHO Regional Office for Europe [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/332516/Eurohealth-25-3-41-46-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

- Verdugo-Paiva F, Bonfill X, Ortuño D, Glick M, Carrasco-Labra A. 2023. Policymakers’ perceived barriers and facilitators in the use of research evidence in oral health policies and guidelines: a qualitative study protocol. BMJ Open. 13(2):e066048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt RG, Daly B, Allison P, Macpherson LMD, Venturelli R, Listl S, Weyant RJ, Mathur MR, Guarnizo-Herreño CC, Celeste RK, et al. 2019. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet. 394(10194):261–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2010. Monitoring the building block of health systems: a handbook of indicators and their measurement strategies [accessed 2023 Jun 20]. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/258734/9789241564052-eng.pdf.

- World Health Organization. 2021. Resolution WHA74/5. Oral health. In: Seventy-fourth World Health Assembly. Geneva, 31 May 2021. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; [accessed 2023 Jun 20]. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA74/A74_R5-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2022. a. Draft global strategy on oral health (WHO WHA 75.10, Add 1, Annex 3). Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organisation; [accessed 2023 Jun 20]. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA75/A75_10Add1-en.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2022. b. Global oral health status report: towards universal health coverage for oral health by 2030. Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; [accessed 2023 Jun 27]. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. 2023. Draft global oral health action plan (2023–2030). Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; [accessed 2023 Jun 20]. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/ncds/mnd/oral-health/eb152-draft-global-oral-health-action-plan-2023-2030-en.pdf?sfvrsn=2f348123_19&download=true. [Google Scholar]