Abstract

The arsenic resistance (ars) operon from plasmid pKW301 of Acidiphilium multivorum AIU 301 was cloned and sequenced. This DNA sequence contains five genes in the following order: arsR, arsD, arsA, arsB, arsC. The predicted amino acid sequences of all of the gene products are homologous to the amino acid sequences of the ars gene products of Escherichia coli plasmid R773 and IncN plasmid R46. The ars operon cloned from A. multivorum conferred resistance to arsenate and arsenite on E. coli. Expression of the ars genes with the bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase-promoter system allowed E. coli to overexpress ArsD, ArsA, and ArsC but not ArsR or ArsB. The apparent molecular weights of ArsD, ArsA, and ArsC were 13,000, 64,000, and 16,000, respectively. A primer extension analysis showed that the ars mRNA started at a position 19 nucleotides upstream from the arsR ATG in E. coli. Although the arsR gene of A. multivorum AIU 301 encodes a polypeptide of 84 amino acids that is smaller and less homologous than any of the other ArsR proteins, inactivation of the arsR gene resulted in constitutive expression of the ars genes, suggesting that ArsR of pKW301 controls the expression of this operon.

Plasmid-mediated bacterial resistance to arsenic and antimony have been known since the work of Novick and Roth (22) and Hedges and Baumberg (14). Studies on the arsenic resistance operon of Escherichia coli conjugative R-factor plasmid R773, Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258, Staphylococcus xylosus plasmid pSX267, and IncN plasmid R46 revealed that the resistance determinants from these organisms are inducible by arsenate, arsenite, or antimonite. The ars operon carried on R-factor R773 (11, 14) encodes a transport system that extrudes arsenate, arsenite, and antimonite from E. coli cells; lowering the intracellular concentration of toxic anions confers resistance to the anions on E. coli (19, 25, 31). The ars operon of R773 comprises five genes, arsR, arsD, arsA, arsB, and arsC (arsRDABC) (5, 28, 41). The arsR and arsD genes encode two different regulatory proteins (39–41). The arsA and arsB genes encode the subunits of an ATP-driven arsenite pump (8). The ArsA protein is an arsenite-stimulated ATPase that is part of a complex with the membrane-bound ArsB protein (15). ArsB is an intrinsic membrane protein that forms the transmembrane channels through which arsenite ions are extruded from cells. This process is driven by the hydrolysis of ATP (9, 36). In the absence of arsA, the arsB gene product alone provides partial arsenite resistance, most likely by functioning as a secondary uniporter driven by the proton motive force (7, 10). Resistance to arsenate is conferred by the reduction of arsenate to arsenite by the arsC gene product; the resulting arsenite is extruded by the transport system (12, 23). IncN plasmid R46 also carries an ars operon comprising five genes, arsRDABC, which are highly homologous to the ars genes of E. coli plasmid R773. On the other hand, although staphylococcal plasmids pI258 and pSX267 also carry ars operons (17, 26), these operons have only three genes, arsRBC; they lack the arsD and arsA genes. The ars operon cloned from the chromosome DNA of the E. coli K-12 strain consists of arsRBC, as does the staphylococcal ars operon. Recently, Neyt et al. (20) have reported that the ars operon of plasmid pYV of Yersina enterocolitica has four genes, three of which are homologous to the E. coli chromosomal arsRBC genes. The fourth gene, arsH, which is absolutely necessary for arsenic resistance, is not homologous to any other known ars gene.

We isolated a new Acidiphilium species (represented by strain AIU 301) from acid mineral water and identified it as Acidiphilium multivorum (38). Recently, we described the transformation of E. coli with 56-kbp plasmid pKW301, which was isolated from A. multivorum AIU 301 and encodes arsenic resistance (34). In this paper, we describe the DNA sequences of arsenic resistance genes arsRDABC of A. multivorum AIU 301 plasmid pKW301, describe the expression of the ars genes induced by arsenic, and discuss the function of ArsR and ArsD in E. coli.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and plasmids.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth (27). When required, ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and/or arsenite (1 to 15 mM) was added to the medium as indicated below.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli strains | ||

| JM109 | recA1 supE44 endA1 hsdR17 gyrA96 relA1 thi Δ(lac-proAB) | 27 |

| HMS174(DE3) | F−recA hsdR (rk12−mk12+) Rifr (DE3) | 33 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pBluescript | Cloning vector (Ampr) | 27 |

| pET14b | Expression vector (Ampr) | 21 |

| pKW301 | A. multivorum plasmid encoding an arsenic resistance gene | 34 |

| pBKAS | 4.9-kbp KpnI fragment of pKW301 cloned into KpnI site of pBluescript | This study |

| pBASK | KpnI fragment flushed of pKW301 recloned into SmaI site of pBluescript in the same orientation as lacZ | This study |

| p14AS | 4.9-kbp XbaI-XhoI fragment of pBASK cloned into pET14b | This study |

| p14ASΔR | p14AS with frameshift mutation in arsR | This study |

| p14ASΔD | p14AS with frameshift mutation in arsD | This study |

DNA manipulations.

Small- and large-scale preparations of plasmid DNAs from E. coli were obtained by the alkaline lysis method (27). Plasmid pKW301 encoding arsenic resistance was isolated from E. coli JM109(pKW301) by the method of Yano and Nishi (43). The ars operon was cloned from pKW301 into pBluescript II KS+ as follows. pKW301 was digested with KpnI, and the resulting KpnI fragments were ligated into the KpnI site of pBluescript II KS+. The ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli JM109. The transformants were screened for arsenic resistance in LB agar plates containing ampicillin and sodium arsenite (15 mM). Other techniques used for DNA modification have been described previously (27).

DNA sequencing.

DNA sequencing of both strands of pBASK was performed by using a Taq cycle sequencing kit (Epicenter Technologies), appropriate dye primers, and a series of subclones with a model 4000L automated DNA sequencer (Licor).

Identification of the ars gene products.

The ars genes were expressed by the T7 RNA polymerase-promoter system (35). pET14b, p14AS, p14ASΔR, and p14ASΔD were each transformed into E. coli HMS174(DE3) bearing the T7 RNA polymerase gene (λ DE3 lysogen) for expression of target proteins. Cells bearing each plasmid were grown at 37°C overnight in LB medium containing ampicillin. Each culture was diluted 100-fold into prewarmed fresh LB medium containing ampicillin alone or ampicillin and sodium arsenite (5 mM) and grown at 37°C. When the A600 of the culture reached 0.8 to 1.0, 1.0 mM isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactoside (IPTG) was added to the culture to induce gene expression, and cultivation was continued for an additional 2 h. Cells were pelleted by centrifugation and dissolved in a loading buffer for sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) (27). Total proteins were analyzed on a 10 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gel (ATTO Co., Tokyo, Japan).

Frameshift mutation of the arsR and arsD genes.

A frameshift mutation was introduced into the arsR or arsD gene of p14AS. The arsR gene includes a unique AflII site, and the arsD gene includes a unique EcoT22I site. p14AS was digested with AflII or EcoT22I, and the recessed or protruding 3′ ends were filled or removed by a T4 DNA polymerase reaction in the presence of deoxynucleoside triphosphates (Takara Shuzo Co., Kyoto, Japan), followed by intramolecular ligations, to produce plasmid p14ASΔR or p14ASΔD. As a result, the arsR and arsD genes contained a frameshift mutation in the 6th and 66th codons, respectively. The mutated genes produced truncated ArsR and ArsD proteins having 7 and 81 amino acid residues, respectively.

Arsenite sensitivity test.

The growth of E. coli strains harboring different plasmids was determined in the presence of arsenite as follows. Overnight cultures (2 ml) of the transformants were inoculated in 100 ml of fresh LB medium containing 10 or 30 mM sodium arsenite in 500-ml flasks and incubated at 37°C with shaking. At 1-h intervals, samples (1 ml) were taken, and the A600 was measured after 10-fold dilution with fresh medium that resulted in an A600 of 0.5 or less.

Isolation of RNA.

ISOGEN reagent (Nippon Gene Co., Tokyo, Japan), was used according to the manufacturer’s directions to isolate total cellular RNA from cells of E. coli JM109(pBASK) grown with 5 mM sodium arsenite. RNA was suspended in ethanol and stored at −70°C until use.

Primer extension analysis.

A primer, 5′-ATTGCCAGATGACGGGAGAT-3′, corresponding to a region within the coding sequence of arsR, was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (Amersham) and used for a primer extension analysis. Total RNA was mixed with the end-labeled primer, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and SuperscriptII RNaseH− reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies, Inc.) and incubated at 42°C for 50 min. The primer extension product was separated on a 6% polyacrylamide gel. A size ladder produced by a dideoxy sequencing reaction of plasmid pBASK with the primer used for the primer extension reaction was used to measure the length of the primer extension product. This sequencing reaction was performed by using a BcaBEST dideoxy sequencing kit (Takara Shuzo) and [α-33P]dCTP (NEN).

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence reported in this paper has been deposited in the DDBJ, EMBL, and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB004659.

RESULTS

Cloning of the ars operon from pKW301.

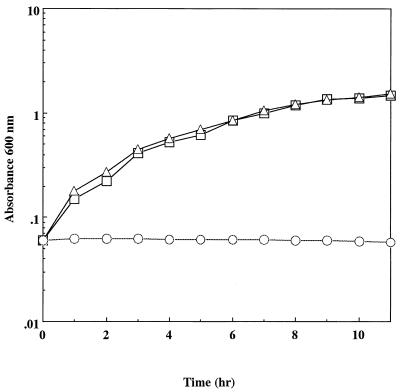

KpnI fragments of pKW301 were ligated to the KpnI site of pBluescript II KS+, and the ligation mixture was used to transform E. coli JM109. Transformants obtained in this way were screened for resistance to sodium arsenite. As a result, an E. coli transformant with arsenic resistance was selected and was shown to carry a recombinant plasmid, designated pBKAS, containing the 4.9-kbp KpnI fragment. This fragment was also found in plasmids from E. coli with arsenic resistance. Plasmid pBKAS conferred resistance to sodium arsenite on E. coli JM109, and the resistance level of E. coli JM109(pBKAS) was as high as that of E. coli JM109(pKW301); i.e., both strains were capable of growing in the presence of 30 mM sodium arsenite (Fig. 1). These results suggested that the 4.9-kbp KpnI fragment from pKW301 contained a complete set of arsenic resistance genes.

FIG. 1.

Growth of E. coli JM109, E. coli JM109(pBKAS), and E. coli JM109(pKW301) in the presence of sodium arsenite. E. coli JM109 (○), E. coli JM109(pBKAS) (□), and E. coli JM109(pKW301) (▵) were cultivated in LB medium containing 30 mM sodium arsenite at 37°C, and the A600 was measured periodically.

Nucleotide sequence of the ars genes.

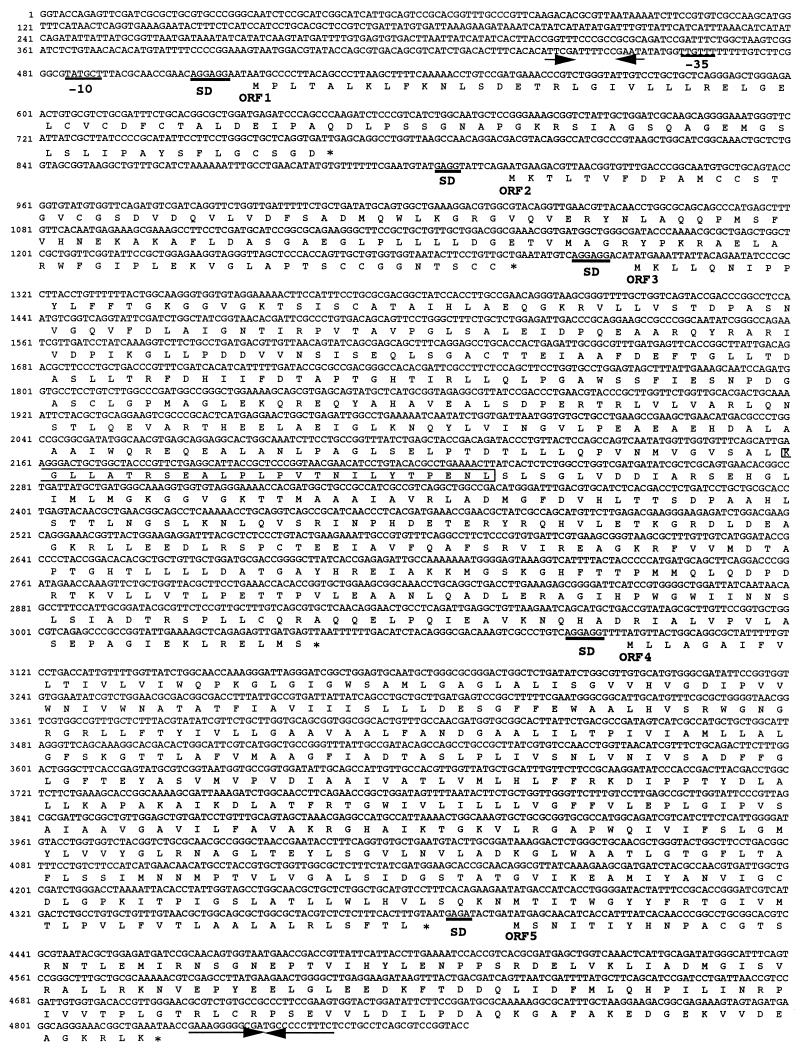

The nucleotide sequence of the 4.9-kbp KpnI fragment cloned into pBluescript II KS+ is shown in Fig. 2. This sequence comprises 4,879 nucleotides and contains five open reading frames (designated ORF1 to ORF5), which are oriented in the same direction and followed (2 bp downstream from the stop codon of ORF5) by a 23-bp palindromic sequence. This palindrome, corresponding to an mRNA hairpin structure with a ΔG of −30.1 kcal/mol, may function as a transcription terminator. These open reading frames encode proteins that belong to five families of well-known proteins involved in arsenic resistance, the ArsR, ArsD, ArsA, ArsB, and ArsC families. Such proteins are known to be encoded by operons present on either plasmids or the chromosome DNA in bacteria. The highest degree of similarity was observed with the corresponding proteins encoded by E. coli plasmid R773 and IncN plasmid R46.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the ars determinants of A. multivorum. The amino acid sequences of the putative gene products are shown below the DNA sequence. Stop codons are indicated by asterisks. Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequences are underlined. Inverted repeats are indicated by arrows. The linker sequence is enclosed in a box. The putative −10 and −35 region promoter sequences are underlined.

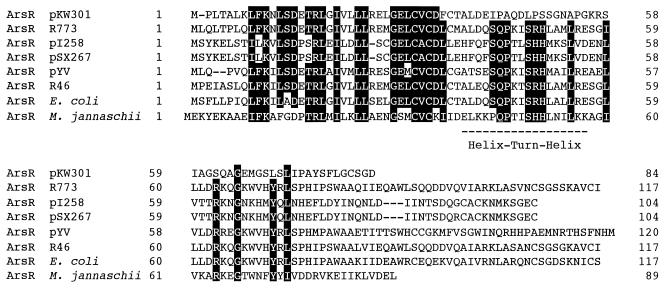

ORF1 (arsR), starting at position 515 and ending at position 769, comprises 255 bp, corresponding to 84 amino acids (Fig. 2). The ORF1 product is a homolog of the ArsR regulators from E. coli plasmid R773 (39), IncN plasmid R46 (1), Y. enterocolitica plasmid pYV (20), staphylococcal plasmids pI258 (17) and pSX267 (26), E. coli chromosome DNA (4), and Methanococcus jannaschii (2). However, the similarity is limited to the first 33 amino acids (69 to 82% identity), and there is no similarity between the C-terminal regions of A. multivorum ArsR and the other ArsR proteins (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Alignment of the ArsR family of metalloregulatory proteins. Amino acids which are conserved in at least six of the eight sequences are highlighted. The dashes indicate gaps that were included to improve alignment. The location of the putative helix-turn-helix DNA-binding motif is indicated by a dashed line. The ArsR proteins of plasmids pKW301, R773 (28), pI258 (17), pSX267 (26), pYV (20), and R46 (1) and of chromosome DNAs of E. coli (4) and M. jannaschii (2) are shown.

ORF2 (arsD), starting at position 916 and ending at position 1,278, encodes a protein of 120 amino acids, which is a homolog of the ArsD regulators. arsD genes have been found in the ars operons of plasmids R773 (41) and R46 (1). The overall sequence identities of R773 and R46 to the ArsD proteins of pKW301 were 86 and 90%, respectively (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the ArsD family of metalloregulatory proteins. Amino acids which are conserved in at least two of the three sequences are highlighted. The ArsD proteins of plasmids pKW301, R773 (41), and R46 (1) are shown.

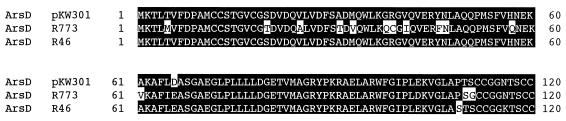

ORF3 (arsA), beginning at position 1,296 and ending at position 3,047, encodes a protein of 583 amino acids, which is a homolog of ArsA. The ArsA protein appears to be a catalytic subunit of the arsenite pump (15). The arsA genes, as well as the arsD genes, have been found exclusively in plasmids R773 and R46. The pKW301 ArsA sequence is 89 and 83% identical to the sequences of R46 and R773, respectively (Fig. 5). The pKW301 ArsA protein consists of two independent domains, which are homologous to each other (33% identity) and are connected by a short linker sequence (18). Each domain contains a canonical P-loop of an ATP-binding motif, as was observed for the ArsA proteins of plasmids R773 (5) and R46 (1). The linker regions separating the N- and C-terminal domains of ArsA of pKW301, R773, and R46 consist of 25 amino acids. These linker sequences exhibit only 20 to 40% identity to each other, although the sequence similarity extends throughout the ArsA proteins.

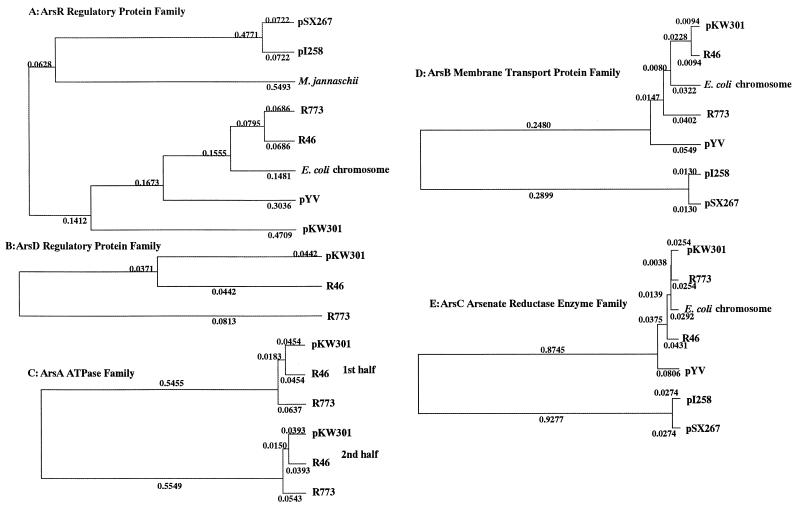

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic trees for ArsR (A), ArsD (B), ArsA (C), ArsB (D), and ArsC (E) proteins. Sequence relationships were determined by using the software of the GENETYX program. The accession numbers for the sequences used to generate the phylogenetic trees are as follows: R773, X16045, U13073, and J02591; R46, U38947; E. coli chromosome, X80057; pYV, U58366; pI258, M86824; pSX267, 80565; and M. jannaschii, L77117, L77118, and L771179.

ORF4 (arsB), starting at position 3,095 and ending at position 4,384, encodes a product of 429 amino acids, which is a homolog of ArsB proteins. The ArsB proteins form the transmembrane channel through which AsO2− ions are pumped across the inner membrane (36). The similarity extends to the proteins of gram-negative bacteria (more than 90% identity) (1, 4, 5, 20) and the proteins of staphylococcal plasmids (58% identity) (17, 26).

ORF5 (arsC) starts at position 4,397, ends at position 4,822, and is followed by the 23-bp palindromic sequence. The 15.8-kDa product (length, 141 amino acids) of ORF5 exhibits 85 to 95% identity to the ArsC proteins from gram-negative bacteria (1, 4, 5, 20), which are arsenate reductases (12). By contrast, this protein exhibits only 22% identity to both of the staphylococcal ArsC proteins (17, 26). The phylogenetic distances between the Ars proteins from A. multivorum and the Ars proteins from other microorganisms are shown in Fig. 5. It is clear that the pKW301 operon is much more similar to the R773 and R46 operons than to the other operons.

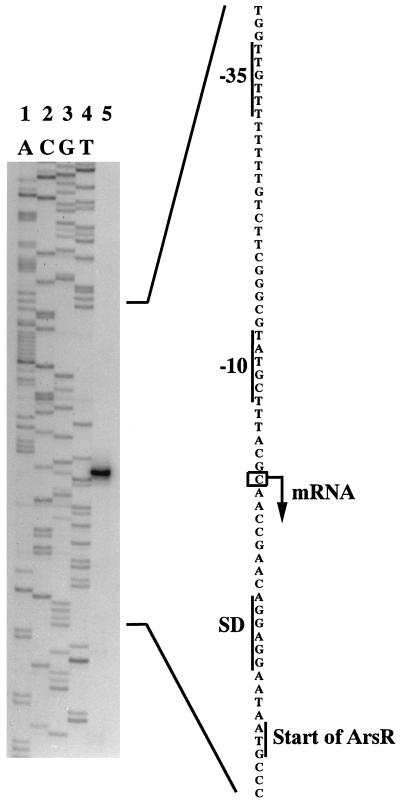

Primer extension mapping of the ars promoter.

In order to determine the location of the ars promoter, the start point of the ars transcript was mapped by performing a primer extension analysis (Fig. 6). One distinct extension product was obtained, and this product corresponded to the C residue at position 496 of the ars sequence. The start point is located nine nucleotides upstream of the Shine-Dalgarno sequence. As shown in Fig. 6, the −10 region (TATGCT) upstream of the transcriptional start is separated from the motif TTGTTT in the −35 region by 16 nucleotides. The region of dyad symmetry is located just upstream of the −35 region (Fig. 2), suggesting that this region may be an operator site. The promoter region was not similar to any other promoter of the ars operons.

FIG. 6.

Primer extension analysis to determine the ars transcriptional start point. Lanes 1 through 4, A-, C-, G-, and T-specific dideoxy sequencing reactions, respectively; lane 5, primer extension product. The corresponding sequence of the coding strand is shown on the right. The Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence, the start codon of arsR, the first nucleotide of the ars transcript, and the −10 and −35 regions of the promoter consensus sequence are indicated.

Studies of expression of the arsRDABC genes in E. coli.

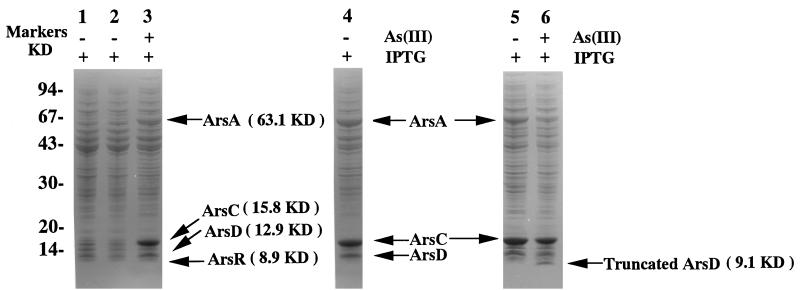

When the arsRDABC genes were transcribed from the intrinsic promoter, the gene products were not detected on an SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie brilliant blue (data not shown). Therefore, we allowed the arsRDABC genes to be expressed with the E. coli expression system based on the T7 RNA polymerase-promoter system (35). The 4.9-kbp XbaI-XhoI fragment from pBASK was inserted into the XbaI-XhoI site of pET14b, which yielded p14AS, in which the ars operon was placed under the control of the T7 promoter. E. coli HMS174(DE3) harboring p14AS was cultivated in the presence or absence of sodium arsenite, and the total proteins were analyzed by using a 10 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gel (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Expression of the A. multivorum ars genes in E. coli under control of the bacteriophage T7 promoter. The plasmids used are listed in Table 1 or described in the text. The gel used was an SDS–10 to 20% polyacrylamide gradient gel. Lane 1, plasmid pET14b without an insert; lanes 2 and 3, p14AS; lane 4, p14ASΔR; lanes 5 and 6, p14ASΔD. The approximate molecular masses of marker proteins (in kilodaltons) are indicated on the left. The arrows indicate the positions of Ars proteins, and the molecular masses calculated from the sequence are indicated in parentheses. KD, kilodalton.

When the transformant carrying the ars genes was cultivated in the presence of sodium arsenite, the ArsD, ArsA, and ArsC proteins were produced in large amounts under the T7 promoter system, and they had apparent molecular weights of 13,000, 64,000, and 16,000, respectively (Fig. 7, lane 3). However, these proteins were not found in the total proteins of E. coli cells grown without sodium arsenite (Fig. 7, lane 2), indicating that they were induced by sodium arsenite. The proteins produced in the presence of sodium arsenite were confirmed to be the arsD, arsA, and arsC gene products by an analysis of their N-terminal amino acid sequences. These results, in combination with the R773 ars operon findings, suggested that ArsR functioned as a repressor protein in E. coli, while ArsR, as well as ArsB, was not overexpressed with the T7 promoter system. Since the smallest protein was detectable in a cell extract of E. coli containing p14AS, but was not detected in a cell extract of E. coli containing p14ASΔR (Fig. 7, lane 4), this protein might be the ArsR protein (Fig. 7, lane 3).

Inactivation of the arsR gene.

To demonstrate that the pKW301 ArsR, which consists of 84 amino acids, is a repressor protein, we constructed p14ASΔR, in which a frameshift mutation was introduced into the 6th codon of arsR. Cells of E. coli HMS174(DE3) harboring p14ASΔR produced ArsD, ArsA, and ArsC in the absence of sodium arsenite (Fig. 7, lane 4), suggesting that the arsR gene of pKW301 encodes a functional repressor protein comprising 84 amino acids and that the expression of the ars genes is controlled by ArsR as an operon.

Inactivation of the arsD gene.

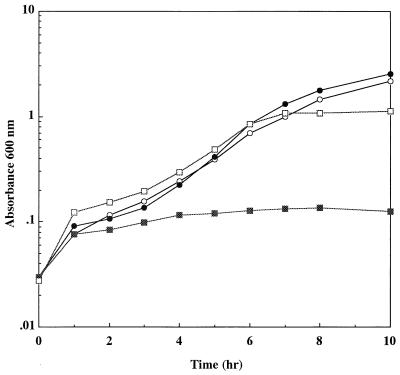

Wu and Rosen (41) reported that in the R773 ars operon, ArsD is a second trans-acting regulator protein and that inactivation of this protein prohibits E. coli carrying the ars operon from growing in medium containing 10 mM sodium arsenite. Recently, Chen and Rosen (6) have demonstrated that ArsD action prevents excess transcription. Therefore, in order to elucidate the function of the pKW301 arsD gene product, a frameshift mutation was introduced into the arsD gene, yielding p14ASΔD. Inactivation of ArsD resulted in overproduction of ArsA, ArsC, and truncated 81-amino-acid ArsD, as reported for R773 (41) (Fig. 7, lane 5 and 6). However, as shown in Fig. 8, E. coli HMS174(DE3) carrying p14ASΔD could grow in medium containing 10 mM sodium arsenite, which is in sharp contrast to the observation described above. These results suggest that overproduction of the ArsB of pKW301 is not as toxic as overproduction of the ArsB of R773.

FIG. 8.

Effect of frameshift mutation of the arsR or arsD gene on arsenic resistance. Cells of E. coli HMS174(DE3) harboring plasmids were grown in LB medium. IPTG (50 μM) and ampicillin were added to the growth medium. Symbols: ○, p14AS; •, p14ASΔR; □, p14ASΔD; ▪, pET14b.

DISCUSSION

The ars operons seem to be divided into three types with respect to gene organization. One type, which is found in the two staphylococcal ars operons and E. coli chromosomal ars operons, is composed of three arsenic resistance genes, arsRBC. The second type, which is found in the ars operons of plasmids R773 and R46 derived from gram-negative bacteria, consist of five genes, arsRDABC. The third type, which has been found recently in a Y. enterocolitica plasmid, absolutely requires the arsH gene for arsenic resistance in addition to arsRBC. The ars genes (arsRDABC) cloned from A. multivorum plasmid pKW301 are similar to the genes cloned from R773 and R46 not only in organization but also in DNA sequences. Knowledge about the mechanism of arsenic resistance has come exclusively from thorough studies on the ars operon of R773.

The latter studies showed that ArsA and ArsB are subunits of an ATP-coupled Ars anion pump, that ArsC is arsenate reductase, and that ArsR and ArsD are trans-acting regulator proteins. The ArsA, ArsB, and ArsC proteins of pKW301 are highly homologous to the corresponding proteins of R773, suggesting that the functions of the former proteins are identical to those of the latter proteins.

On the other hand, ArsR of pKW301 is less similar to the ArsR proteins described previously; i.e., although the region between Leu-13 and Leu-72 of R773 ArsR is conserved in all ArsR proteins except ArsR of pKW301, conservation in pKW301 is restricted to the first half of this region (Fig. 3). ArsR of pKW301, comprising 84 amino acids, is smaller than any other repressor protein of the ars group. Metal-binding sites conserved as “ELCVCDL” and DNA-binding sites conserved as a “helix-turn-helix motif” were predicted for metal-dependent repressors (29, 30). The importance of three Cys residues in the metal-binding motif and a His residue and a Ser residue in the helix-turn-helix motif was shown by an analysis of the arsR mutants of R773 (29, 30). In ArsR of pKW301, the three Cys residues are conserved, but the amino acid sequence of the helix-turn-helix region including the His and Ser residues is not conserved. Nevertheless, it is apparent that this exceptionally small protein can function as a repressor since the expression of the ars genes depended on the presence of sodium arsenite (Fig. 7), and furthermore, inactivation of ArsR by the frameshift mutation abolished the dependence of ars gene expression on arsenite (Fig. 7). The secondary structure of the region of ArsR of pKW301 that corresponds to the DNA-binding sites predicted for other repressor proteins was predicted by the GENETYX program (Software Development Co, Tokyo, Japan) by using the method of Robson (3). The predicted structure tends to form a helix-turn-helix structure (data not shown), despite the low apparent sequence similarity between this region and the corresponding regions in the other repressor protein. Analysis of the nucleotide sequences of the arsR genes from pKW301 and R773 demonstrated a surprising fact: if an adenosine residue at position 636 is deleted from the arsR sequence of pKW301, ORF1, starting at position 515, is extended to position 862 and encodes 116 amino acids. This imaginary product has an overall identity with ArsR of R773 of 86% and contains both metal- and DNA-binding sites that are almost identical to those of R773. However, the nucleotide sequence shown in Fig. 2 was unmistakably confirmed by sequencing both strands of several subclones that contain different inserts carrying the region around position 636. Therefore, we presume that the arsR gene of pKW301, which originally encoded a larger repressor protein, suffered from insertional mutation of a nucleotide. This would have caused the frameshift in the gene, but the resulting small protein retained its function as a repressor since the secondary structure of the DNA-binding site was maintained. This hypothesis is consistent with recently reported evidence showing that approximately 80 N-terminal amino acid residues of the ArsR family are required for the repressor to function (42).

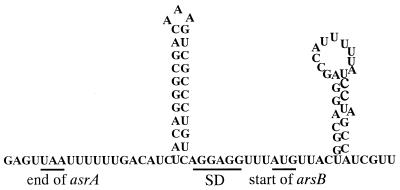

ArsD of R773 sets the maximal level of ars expression in order to prevent the arsB gene from being overexpressed. Overproduction of ArsB was shown to have a deleterious effect on E. coli cells. Inactivation of the arsD gene in R773 by a frameshift mutation in the 66th codon made E. coli cells carrying unmodified arsA and arsB sensitive to arsenic salts because of the deleterious effect of ArsB overproduction. By contrast, E. coli cells carrying a frameshift in the same position of arsD of pKW301 grew well in the presence of 10 mM sodium arsenite. The difference in the effects of the arsD mutations may be explained by a difference in the expression levels of the arsB genes. The arsB gene product could not be detected in E. coli carrying pKW301 ars genes by SDS-PAGE, although ArsD, ArsA, and ArsC were overproduced (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 9, two potential secondary structures were observed around the initiation codon of the arsB mRNA, and these structures had calculated free energies of formation of −27.4 and −20.2 kcal/mol. Either one of these structures at the 5′ end of arsB may reduce the synthesis of this membrane protein at the translational level, as predicted for R773 (24). An alternative function of ArsD was suggested by Fig. 7. Inactivation of ArsD also resulted in overexpression of the ars genes of pKW301, suggesting that ArsD in addition to ArsR is necessary for regulating the expression of this operon.

FIG. 9.

Sequence and potential secondary structure of the translational initiation regions of the arsB mRNA. The termination codon (UAA) of the arsA gene, the putative ribosome-binding site, and the AUG codon of the arsB gene are indicated. SD, Shine-Dalgarno sequence.

The ars operon of pKW301 isolated from the gram-negative bacterium A. multivorum is, on the whole, quite similar to the ars operons of plasmids R773 and R46, both of which are related to gram-negative bacteria. Given the phylogenetic distance between the gene products of the ars operons of A. multivorum AIU 301 and those of E. coli (Fig. 5), such a similarity suggested that the genes had been exchanged between these bacteria. The question arose as to which organism was the donor. An answer might be obtained by analyzing the codon usage of the two genes studied and comparing them with the codon usage prevailing in both organisms (37). Unfortunately, only one gene has been characterized from Acidiphilium sp. (16). Another possibility is to use the G+C content as a criterion, as described previously for endoglucanases (13). The G+C content of the A. multivorum AIU 301 chromosome is 67 mol% (38), while the G+C content of the E. coli chromosome is approximately 50 mol% (32). The G+C content of the pKW301 ars operon is 51 mol%, a value similar to the G+C contents of the E. coli chromosome (4), R773 (5, 28, 41), and R46 (1). In contrast, the G+C content of the A. multivorum AIU 301 chromosome (67 mol%) is much higher than the G+C content of the ars operon of pKW301. Hence, it is tempting to speculate that the ars operon was recently acquired by A. multivorum AIU 301 from E. coli. This speculation is supported by the observation that the codon usage of the ars operon of pKW301 is somewhat similar to the codon usage of the ars operon of R773 and the codon usage of the prevailing ars operon in E. coli. However, the DNA sequence outside the coding region (i.e., the promoter-operator site) is not homologous to the sequences of the corresponding regions of the E. coli chromosome, R773, and R46. Furthermore, an insertional frameshift mutation was predicted to be present in the pKW301 arsR gene. Therefore, it is likely that the ars operon of pKW301 arose from E. coli but acquired its distinct regulatory regions and proteins by an evolutionary process to more efficiently control the expression of the ars genes in A. multivorum. Regulation of expression of the pKW301 ars operon by ArsR and ArsD remains to be studied.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank S. Karita for assistance in amino acid sequence analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bruhn D F, Li J, Silver S, Roberto F, Rosen B P. The arsenical resistance operon of IncN plasmid R46. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;139:149–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08195.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, Kerlavage A R, Dougherty B A, Tomb J-F, Adams M D, Reich C I, Overbeek R, Kirkness E F, Weinstock K G, Merrick J M, Glodek A, Scott J L, Geoghagen N S M, Weidman J F, Fuhrmann J L, Nguyen D, Utterback T R, Kelley J M, Peterson J D, Sadow P W, Hanna M C, Cotton M D, Roberts K M, Hurst M A, Kaine B P, Borodovsky M, Klenk H-P, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Woese C R, Venter J C. Complete genome sequence of the methanogenic archaeon, Mehtanococcus jannaschii. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantor C R, Schimmel P R. Biophysical chemistry, part III. The behavior of biological macromolecules. New York, N.Y: W. H. Freeman & Co.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlin A, Shi W, Dey S, Rosen B P. The ars operon of Escherichia coli confers arsenical and antimonial resistance. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:981–986. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.4.981-986.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen C-M, Misra T, Silver S, Rosen B P. Nucleotide sequence of the structural genes for an anion pump; the plasmid-encoded arsenical resistance operons. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:15030–15038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Y, Rosen B P. Metalloregulatory properties of the ArsD repressor. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14257–14262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dey S, Rosen B P. Dual mode of energy coupling by the oxanion-translocating ArsB protein. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:385–389. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.2.385-389.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dey S, Dou D, Rosen B P. ATP-dependent arsenite transport in everted membrane vesicles of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25442–25446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dey S, Dou D, Tisa L S, Rosen B P. Interaction of the catalytic and the membrane subunits of an oxanion-translocating ATPase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:418–424. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dou D, Dey S, Rosen B P. A functional chimeric membrane subunit of an ion-translocating ATPase. Antonie Leewenhoek. 1994;65:359–368. doi: 10.1007/BF00872219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elek S D, Higney L. Resistance typing—a new epidemilogical tool; application to Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 1970;3:103–110. doi: 10.1099/00222615-3-1-103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gladysheva T B, Oden K L, Rosen B P. Properties of the arsenate reductase of plasmid R773. Biochemistry. 1994;33:7287–7293. doi: 10.1021/bi00189a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guiseppi A, Aymeric J L, Cami B, Barras F, Creuzet N. Sequence analysis of the cellulase-encoding celY gene of Erwinia chrysanthemi: a possible case of interspecies gene transfer. Gene. 1991;106:109–114. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90573-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hedges R W, Baumberg S. Resistance to arsenic compounds conferred by a plasmid transmissible between strains of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1973;115:459–460. doi: 10.1128/jb.115.1.459-460.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu C M, Rosen B P. Characterization of the catalytic subunit of an anion pump. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:17349–17354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inagaki K, Tomono J, Kishimoto N, Tano T, Tanaka H. Cloning and sequence of the recA gene of Acidiphilium facilis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:4149. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.17.4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ji G, Silver S. Regulation and expression of the arsenic resistance operon from Staphylococcus aureus plasmid pI258. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3684–3694. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3684-3694.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kaur P, Rosen B P. Identification of the site of α-[32P]ATP adduct formation in the ArsA protein. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6456–6461. doi: 10.1021/bi00187a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mobley H L T, Rosen B P. Energetics of plasmid-mediated arsenate resistance in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6119–6122. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Neyt C, Iriarte M, Thi V H, Cornelis G R. Virulence and arsenic resistance in yersiniae. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:612–619. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.612-619.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Novagen, Inc. Novagen catalog. Madison, Wis: Novagen, Inc.; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novick R P, Roth C. Plasmid-linked resistance to inorganic salts in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:1335–1342. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.4.1335-1342.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oden K L, Gladysheva T B, Rosen B P. Arsenate reduction mediated by the plasmid-encoded ArsC protein is coupled to glutathione. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:301–306. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Owolabi J B, Rosen B P. Differential mRNA stability controls relative gene expression within the plasmid-encoded arsenical resistance operon. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2367–2371. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.5.2367-2371.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosen B P, Borbolla M G. A plasmid-encoded arsenite pump produces resistance in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984;124:760–765. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)91023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosenstein R, Peschel P, Wieland B, Götz F. Expression and regulation of the Staphylococcus xylosus antimonite, arsenite, and arsenate resistance operon. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:3676–3683. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.11.3676-3683.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 28.San Francisco M J D, Hope C L, Owolabi J B, Tisa L S, Rosen B P. Identification of the metalloregulatory element of the plasmid-encoded arsenical resistance operon. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:619–624. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.3.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shi W, Wu J, Rosen B P. Identification of a putative metal binding site in a new family of metalloregulatory proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19826–19829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shi W, Dong J, Scott R A, Kzenzenko M Y, Rosen B P. The role of arsenic-thiol interactions in metalloregulation of the ars operon. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:9291–9297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.16.9291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silver S, Budda K, Leahy K M, Shaw W V, Hammond D, Novick R P, Willsky G R, Malamy M H, Rosenberg H. Inducible plasmid-determined resistance to arsenate, arsenite, and antimony(III) in Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1981;146:983–996. doi: 10.1128/jb.146.3.983-996.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Staley J T, Bryant M P, Pfennig N, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 3. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Studier F, Mottaft B A. Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J Mol Biol. 1986;189:113–130. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90385-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki K, Wakao N, Sakurai Y, Kimura T, Sakka K, Ohmiya K. Transformation Escherichia coli with a large plasmid of Acidiphilum multivorum AIU 301 encoding arsenic resistance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:2089–2091. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.5.2089-2091.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tabor S, Richardson C C. A bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase/promoter system for controlled exclusive expression of specific genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:1074–1078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.4.1074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tisa L S, Rosen B P. Molecular characterization of anion pump: the ArsB protein is the membrane anchor for the ArsA protein. J Biol Chem. 1991;265:190–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van V F, Boyen A, Glansdorff N. On interspecies gene transfer: the case of the argF gene of Escherichia coli. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1988;139:493–496. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(88)90111-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wakao N, Nagasawa N, Matsuura T, Matsukura H, Matsumoto T, Hiraishi A, Sakurai Y, Shiota H. Acidiphilium multivorum sp. nov., an acidophilic chemoorganotrophic bacterium from pyrtic acid mine drainage. J Gen Appl Microbiol. 1994;40:143–159. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu J H, Rosen B P. The ArsR protein is trans-acting regulatory protein. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:1331–1336. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu J H, Rosen B P. Metalloregulated expression of the ars operon. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:52–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu J H, Rosen B P. The arsD gene encodes a second transacting regulatory protein of the plasmid-encoded resistance operon. Mol Microbiol. 1993;8:615–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu C, Rosen B P. Dimerization is essential for DNA binding and repression by the ArsR metalloregulatory protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:15734–15738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.15734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yano K, Nishi T. pKJ, a naturally occurring conjugative plasmid coding for toluene degradation and resistance to streptomycin and sulfonamides. J Bacteriol. 1980;143:552–560. doi: 10.1128/jb.143.2.552-560.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]