Abstract

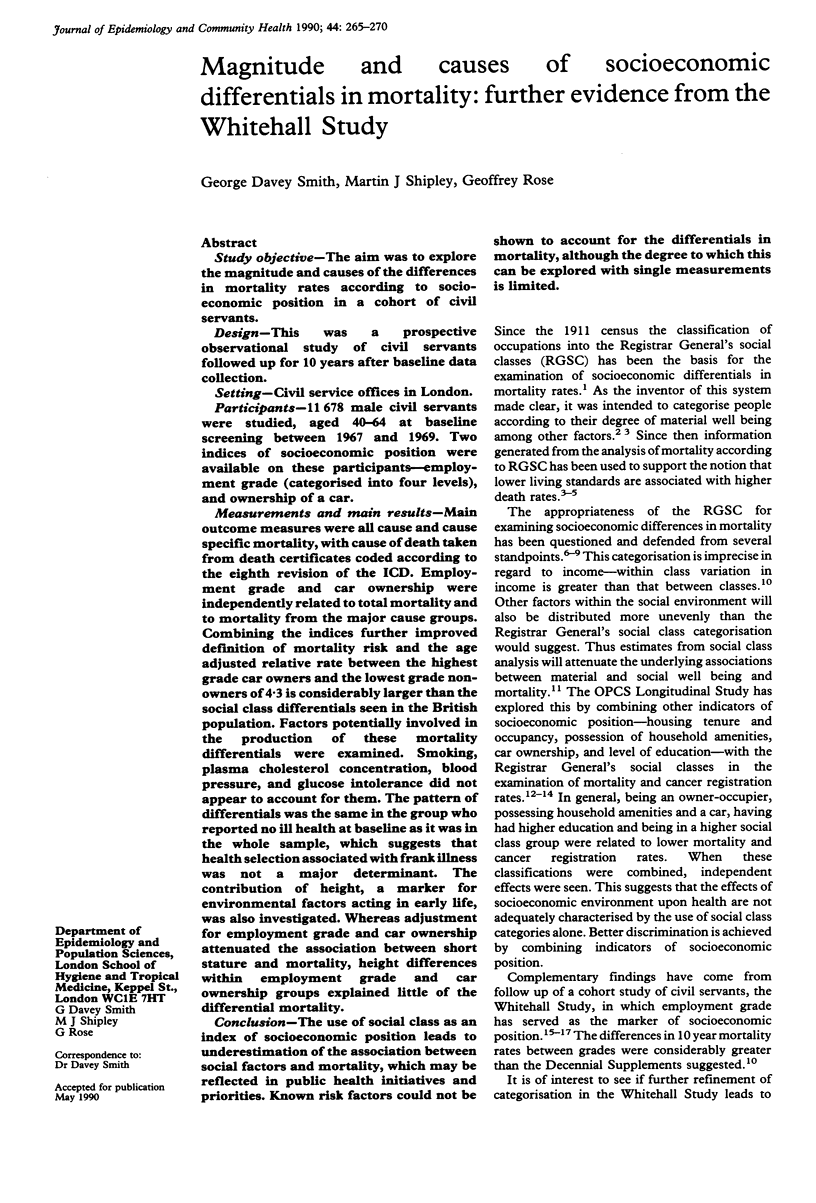

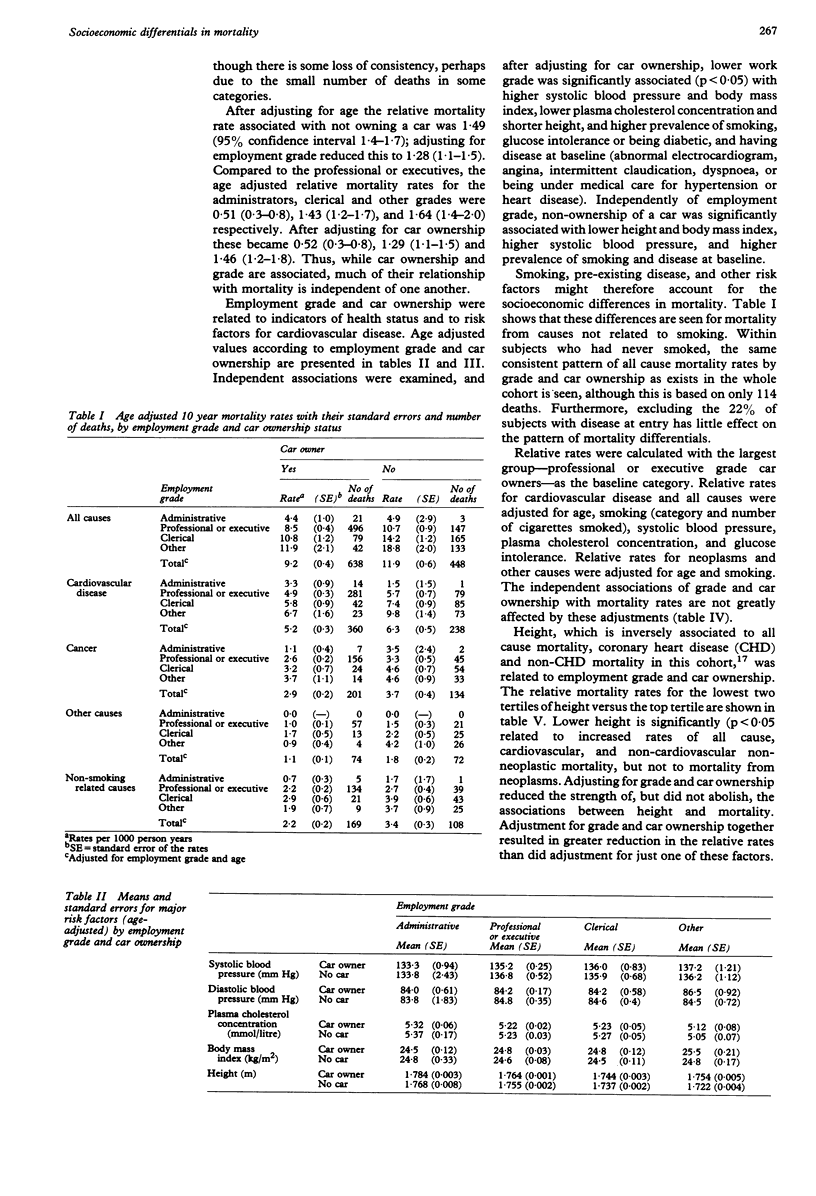

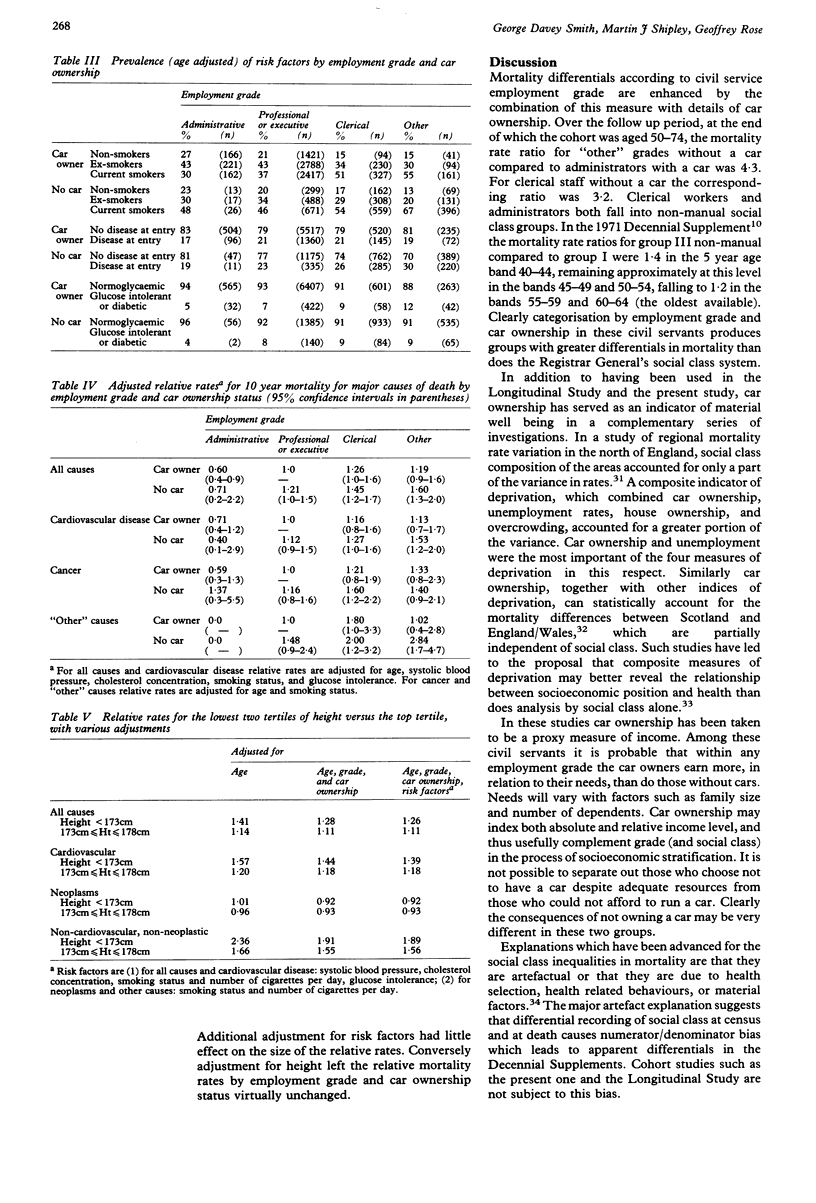

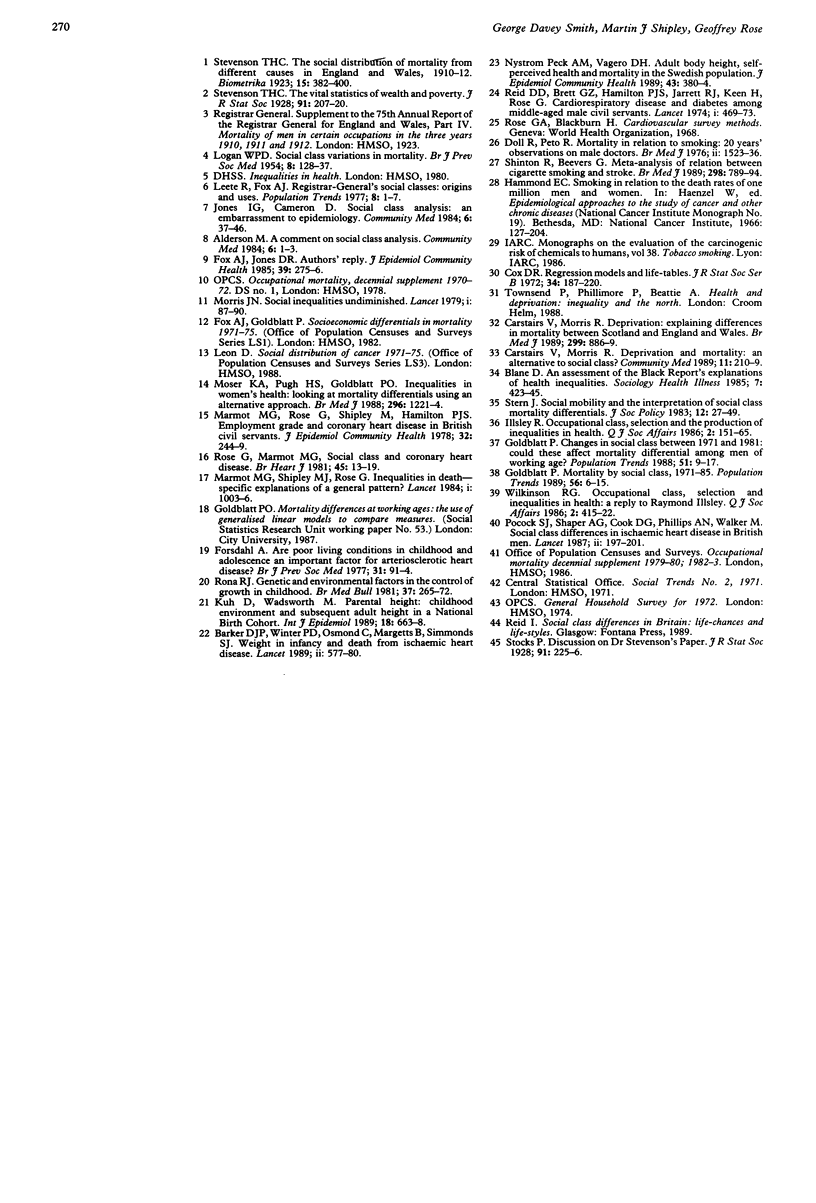

STUDY OBJECTIVE--The aim was to explore the magnitude and causes of the differences in mortality rates according to socioeconomic position in a cohort of civil servants. DESIGN--This was a prospective observational study of civil servants followed up for 10 years after baseline data collection. SETTING--Civil service offices in London. PARTICIPANTS--11,678 male civil servants were studied, aged 40-64 at baseline screening between 1967 and 1969. Two indices of socioeconomic position were available on these participants--employment grade (categorised into four levels), and ownership of a car. MEASUREMENTS AND MAIN RESULTS--Main outcome measures were all cause and cause specific mortality, with cause of death taken from death certificates coded according to the eighth revision of the ICD. Employment grade and car ownership were independently related to total mortality and to mortality from the major cause groups. Combining the indices further improved definition of mortality risk and the age adjusted relative rate between the highest grade car owners and the lowest grade non-owners of 4.3 is considerably larger than the social class differentials seen in the British population. Factors potentially involved in the production of these mortality differentials were examined. Smoking, plasma cholesterol concentration, blood pressure, and glucose intolerance did not appear to account for them. The pattern of differentials was the same in the group who reported no ill health at baseline as it was in the whole sample, which suggests that health selection associated with frank illness was not a major determinant. The contribution of height, a marker for environmental factors acting in early life, was also investigated. Whereas adjustment for employment grade and car ownership attenuated the association between short stature and mortality, height differences within employment grade and car ownership groups explained little of the differential mortality. CONCLUSION--The use of social class as an index of socioeconomic position leads to underestimation of the association between social factors and mortality, which may be reflected in public health initiatives and priorities. Known risk factors could not be shown to account for the differentials in mortality, although the degree to which this can be explored with single measurements is limited.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alderson M. A comment on social class analysis. Community Med. 1984 Feb;6(1):1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker D. J., Winter P. D., Osmond C., Margetts B., Simmonds S. J. Weight in infancy and death from ischaemic heart disease. Lancet. 1989 Sep 9;2(8663):577–580. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90710-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs V., Morris R. Deprivation and mortality: an alternative to social class? Community Med. 1989 Aug;11(3):210–219. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a042469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs V., Morris R. Deprivation: explaining differences in mortality between Scotland and England and Wales. BMJ. 1989 Oct 7;299(6704):886–889. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6704.886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsdahl A. Are poor living conditions in childhood and adolescence an important risk factor for arteriosclerotic heart disease? Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977 Jun;31(2):91–95. doi: 10.1136/jech.31.2.91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond E. C. Smoking in relation to the death rates of one million men and women. Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 1966 Jan;19:127–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones I. G., Cameron D. Social class analysis--an embarrassment to epidemiology. Community Med. 1984 Feb;6(1):37–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuh D., Wadsworth M. Parental height: childhood environment and subsequent adult height in a national birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Sep;18(3):663–668. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.3.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOGAN W. P. Social class variations in mortality. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1954 Jul;8(3):128–137. doi: 10.1136/jech.8.3.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Rose G., Shipley M., Hamilton P. J. Employment grade and coronary heart disease in British civil servants. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Dec;32(4):244–249. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.4.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marmot M. G., Shipley M. J., Rose G. Inequalities in death--specific explanations of a general pattern? Lancet. 1984 May 5;1(8384):1003–1006. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N. Social inequalities undiminished. Lancet. 1979 Jan;1(8107):87–90. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(79)90073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser K. A., Pugh H. S., Goldblatt P. O. Inequalities in women's health: looking at mortality differentials using an alternative approach. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Apr 30;296(6631):1221–1224. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6631.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck A. M., Vågerö D. H. Adult body height, self perceived health and mortality in the Swedish population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1989 Dec;43(4):380–384. doi: 10.1136/jech.43.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock S. J., Shaper A. G., Cook D. G., Phillips A. N., Walker M. Social class differences in ischaemic heart disease in British men. Lancet. 1987 Jul 25;2(8552):197–201. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90774-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid D. D., Brett G. Z., Hamilton P. J., Jarrett R. J., Keen H., Rose G. Cardiorespiratory disease and diabetes among middle-aged male Civil Servants. A study of screening and intervention. Lancet. 1974 Mar 23;1(7856):469–473. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(74)92783-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rona R. J. Genetic and environmental factors in the control of growth in childhood. Br Med Bull. 1981 Sep;37(3):265–272. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.bmb.a071713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G., Marmot M. G. Social class and coronary heart disease. Br Heart J. 1981 Jan;45(1):13–19. doi: 10.1136/hrt.45.1.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinton R., Beevers G. Meta-analysis of relation between cigarette smoking and stroke. BMJ. 1989 Mar 25;298(6676):789–794. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern J. Social mobility and the interpretation of social class mortality differentials. J Soc Policy. 1983 Jan;12(1):27–49. doi: 10.1017/s0047279400012289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]