Abstract

One of the chitinase genes of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, the chitinase C-encoding gene (chiC), was cloned, and the nucleotide sequence was determined. An open reading frame coded for a protein of 430 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 46,680 Da. Alignment of the deduced amino acid sequence demonstrated that ChiC contained three functional domains, the N-terminal domain, a fibronectin type III-like domain, and a catalytic domain. The N-terminal domain (59 amino acids) was similar to that found in the C-terminal extension of ChiA (50 amino acids) of this strain and furthermore showed significant sequence homology to the regions found in several chitinases and cellulases. Thus, to evaluate the role of the domain, we constructed the hybrid gene that directs the synthesis of the fusion protein with glutathione S-transferase activity. Both the fusion protein and the N-terminal domain itself bound to chitin, indicating that the N-terminal domain of ChiC constitutes an independent chitin-binding domain.

Chitin, an insoluble linear β-1,4-linked polymer of N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc), is one of the most abundant polysaccharides in nature. Enormous amounts of chitin are synthesized in the biosphere, and about 1011 metric tons is produced annually in the aquatic biosphere alone. However, there is no substantial accumulation of chitin in ocean sediments (31), because chitinous particles are effectively degraded and catabolized by marine bacteria as soon as they reach the ocean floor (21). Yu et al. (44) pointed out that the oceans would be completely depleted of carbon and nitrogen in a relatively short time if chitin could not be returned to the ecosystem in a biologically usable form. These observations indicate that marine bacteria play an important ecological role in the degradation of chitin in the oceans. However, the genetic and biochemical mechanisms involved in chitin degradation by marine bacteria have not been fully elucidated at the molecular level, although there is a report on the degradation and catabolism of chitin oligosaccharides by Vibrio furnissii (1).

Chitinase (EC 3.2.1.14) and N-acetylglucosaminidase (GlcNAcase) (EC 3.2.1.30) are essential components catalyzing the conversion of insoluble chitin to its monomeric component. These enzymes are found in a wide variety of organisms including bacteria, fungi, insects, plants, and animals, and their corresponding genes have been cloned and characterized. In addition, the three-dimensional structure of chitinase A protein of Serratia marcescens has been determined and the domain structure and two catalytic amino acid residues (Glu and Asp) have been clarified (22).

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 is a gram-negative, flagellated, motile, and aerobic rod-shaped bacterium of marine origin (32). This strain produces at least four different chitinases (ChiA, ChiB, ChiC, and ChiD) and three different GlcNAcases (GlcNAcaseA, GlcNAcaseB, and GlcNAcaseC) in the presence of chitin (unpublished data). Over the last few years, we have purified chitinases and GlcNAcases (33–36) from this strain. Among them, the genes encoding ChiA (truncated form of Chi85) (37), GlcNAcaseB (36), and GlcNAcaseC (35) have been cloned and characterized to clarify the role of individual enzymes in the chitinolytic system of the microorganism. Our final goal is to clarify the relationship between structure and function and the regulatory system of a variety of enzymes involved in the chitin-degrading system of this strain. In this paper, we describe the cloning and sequencing of one of the chitinase genes, chiC gene, from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7. The deduced amino acid sequence of the chitinase was compared with those of closely related chitinases, and the domain structure of ChiC and the role of each domain are discussed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C in Bacto Marine Broth 2216 (Difco) and was used as the source of chromosomal DNA. Escherichia coli JM109 and BL21 were grown at 37°C in Luria broth (LB). For agar medium, LB was solidified with 1.5% (wt/vol) agar (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). For the production of chitin-degrading enzymes, Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C in a medium containing, per liter of artificial seawater (Jamarin S; Jamarin Laboratory, Osaka, Japan), Bacto Peptone (Difco), 5.0 g; Bacto Yeast Extract (Difco), 1.0 g; and powdered chitin from crab shells (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan), 1.0 g.

General recombinant DNA techniques.

Alteromonas chromosomal DNA was isolated as described previously (37). Plasmid DNA from E. coli was purified by an alkali lysis procedure (26) or with a Qiagen kit (Qiagen Inc., Chatsworth, Calif.). Agarose gel electrophoresis, transformation of E. coli and ligation were described by Sambrook et al. (26). Restriction endonucleases were purchased from Toyobo (Tokyo, Japan) or New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, Mass.) and were used as specified by the manufacturer. Chromosomal DNA was partially digested with HindIII and electrophoresed on a 0.6% agarose gel. The fragments in the range of 3 to 5 kb were excised from the gel and were purified with a Sephaglas BandPrep kit (Pharmacia). These were ligated into the dephosphorylated HindIII site of pUC19, and the recombinant plasmids were inserted into competent E. coli JM109. For the screening of chitinase-producing clones, the transformants were spread on LB agar plates containing 0.05% (wt/vol) ethylene glycol chitin, 0.01% (wt/vol) trypan blue, and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml by the method of Ueda et al. (40). The plates were incubated at 37°C overnight. Colonies forming clear halos indicated putative clones containing hybrid plasmids with genomic inserts encoding chitinase activity.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

The nucleotide sequence was determined from both strands by the dideoxy chain termination method (27) with Qiagen purified plasmid DNA and a Thermo Sequenase fluorescently labelled primer cycle sequencing kit (Amersham International plc.). DNA fragments were analyzed on a DNA sequencer (Hitachi SQ3000).

Purification of chitinase C.

Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was grown at 27°C for 16 h, and the residual chitin was isolated from the cells with a no. 1 filter paper (Toyo Roshi Kaisha, Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) and washed several times with 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) containing 1.0 M NaCl. Then the chitinase activity was released from the chitin in the presence of 6 M guanidine hydrochloride and the eluate was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The dialyzate was centrifuged at 24,650 × g at 4°C. The crude chitinase was dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0). The dialyzed solution was applied to a DEAE-Toyopearl 650 M column (1.9 by 45 cm; Tosoh Co., Tokyo, Japan) equilibrated with the same buffer. The column was washed with the buffer (300 ml) and then with a linear gradient of NaCl (0 to 1.0 M) at a flow rate of 24 ml/h. Chitinase C (ChiC) activity was eluted at about 0.55 M NaCl. The active fraction was pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration with a Q 0100 membrane (Advantec). The concentrated sample was applied to a Toyopearl HW column (1.9 by 50 cm; Tosoh Co.) equilibrated with the buffer containing 0.1 M NaCl. For further purification, the active fraction was chromatographed with a linear gradient of NaCl with fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) Resource Q (6 ml; Pharmacia) and a Cosmogel QA column (8 by 75 mm; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan). On the other hand, a chitinase-positive clone, designated pChiC, was cultured to the early stationary phase at 37°C with vigorous shaking. A periplasmic extract of E. coli, in which chitinase activity was located, was prepared by the method of Koshland and Botstein (14). The cloned enzyme was purified by the same method as the native enzyme.

Enzyme assay.

Chitinase activity was measured as described previously (33), with ethylene glycol chitin (Seikagaku Co., Tokyo, Japan) as a substrate. One unit of chitinase was defined as the amount of enzyme that liberated 1 μmol of GlcNAc per min at 60°C. High-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis of the enzymatic digests was carried out as described in a previous paper (33).

N-terminal amino acid sequence and protein assay.

Purified native and cloned ChiC were desalted by centrifugation with Ultracent-10 (Tosoh Co.). These samples were analyzed by an Applied Biosystems model 473A gas-phase sequencer. Protein was assayed by the method of Bradford with bovine serum albumin as a standard (3).

SDS-PAGE.

Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) in a 12.0 or 15.0% gel was done by the method of Laemmli (17). After electrophoresis, the gel was stained with Coomassie brilliant blue G. A molecular weight marker “Daiichi” III (Daiichi Pure Chemicals, Tokyo, Japan) was used as a standard.

Construction of gene fusion.

Two oligonucleotide primers, 5′ GCACTAGCGGTCGACTGTAGCAAC 3′ (24-mer) and 5′ CCCCAAGTCCTCGAGACTAAAGGCA 3′ (25-mer), were synthesized by Kyoto Research Center of Cruachem Co. These primers correspond to bases 280 (sense) and bases 470 (antisense) of the chiC gene, respectively, and are modified to contain SalI and XhoI recognition sites to facilitate cloning in frame into the glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein expression vector pGEX-5X-3 (Pharmacia Biotech). To insert the 5′ region of the chiC gene into the pGEX-5X-3, a 205-bp segment was amplified by PCR with the primers. The PCR mixture consisted of 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3) containing 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 200 mM each deoxynucleotide triphosphate, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase, 0.25 mM primer, and 50 ng of template DNA in a reaction volume of 100 μl. The reaction conditions were as follows: one cycle of 2 min at 95°C for followed by 25 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 2 min at 50°C, and 1 min at 75°C. The amplified DNA was digested with SalI and XhoI and cloned into similarly digested pGEX-5X-3. The nucleotide sequences of the junction between the vector and insert and the whole amplified DNA were confirmed with a Thermo Sequenase cycle-sequencing kit (Amersham International plc.) with fluorescently labelled pGEX 5′ primer. Fusion protein was purified from E. coli BL21 lysate by affinity chromatography with glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Pharmacia Biotech). The purified fusion protein (12 mg) was treated with factor Xa (44 μg) for 12 h at 25°C to obtained the N-terminal domain and dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) for 24 h. The desired protein was purified by HPLC (column, μBandasphere C4, 3.9 by 150 mm; solvent system; linear gradient elution from 0.05% TFA in H2O to 95% CH3CN in 0.05% TFA for 30 min at a flow rate of 1 ml/min; temperature, ambient).

Chitin-binding study.

Binding assays were carried out by adding purified ChiC (6 U) or GST fusion protein (3.5 U) to 20 mg each of chitin, chitosan, and crystalline cellulose (Avicel) in 0.4 ml of 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) in 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes. In adsorption assays of the N-terminal domain itself, 1 mg of chitin was used. Samples were placed on ice for 1 h with mixing every 5 min and then centrifuged at 24,650 × g for 5 min. After filtration with a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane filter, the supernatants of ChiC and the fusion protein were measured for chitinase and GST activity, respectively, and the activity lost from the supernatant was assumed to be the activity bound. GST activity was measured by the GST detection module (Pharmacia Biotech) as specified by the manufacturer. In the case of the N-terminal domain, the unadsorbed-protein concentration, [F], in the supernatant was determined from the absorbance at 280 nm. The extinction coefficient for the N-terminal domain (28,120 M−1 cm −1) was predicted from the tryptophan, tyrosine, and cysteine contents of the protein (7). The bound-protein concentration, [B], was determined from the difference between the initial protein concentration and [F].

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence data reported in this paper will appear in the DDBJ, EMBL and GenBank nucleotide sequence databases under accession no. AB004557.

RESULTS

Cloning and nucleotide sequence of chiC gene.

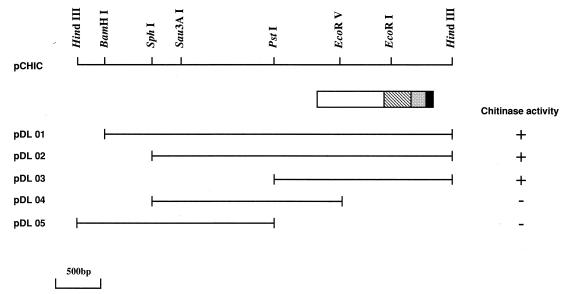

A gene library of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 was screened for the expression of chitinase. From 2,000 transformants, three chitinase-positive clones were shown to have chitin-degrading ability. One was the chiA gene, which has been reported formerly (37), and the others contained the same 4.2-kb HindIII insert. A restriction map of the cloned gene is shown in Fig. 1. To determine the coding region for the enzyme, various subclones were prepared and expression of chitinase in E. coli was determined by the formation of clear halos around the colonies. These results indicated that the coding region for the chitinase gene was on the 1.9-kb PstI-HindIII fragment.

FIG. 1.

Restriction maps of the cloned gene and the domain structure of ChiC. The transformants carrying the plasmids with appropriate deletions were transferred to an LB agar plate containing 0.05% glycol chitin, 0.01% trypan blue, and 100 μg of ampicillin per ml. Production of chitinase was judged by the formation of clear halos around the colonies. +, visible halo; −, no halo. The box indicates the coding sequence and the domain structure of ChiC. ▪, signal peptide; ░⃞, chitin-binding domain; ▧, fibronectin type III-like domain; □, catalytic domain.

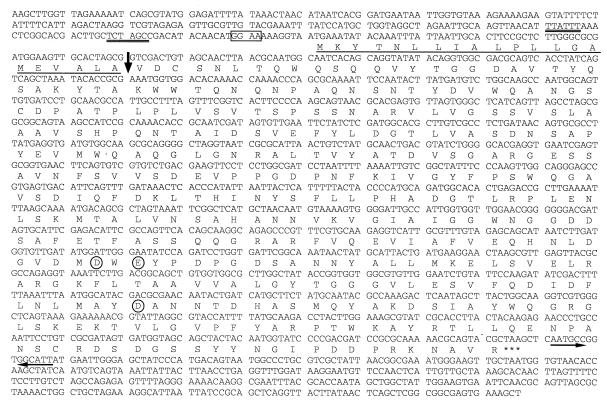

The nucleotide sequence of chiC gene and the deduced amino acid sequence are presented in Fig. 2. A single open reading frame of 1,290 bp coding for 430 amino acids was identified starting from the first ATG. A putative signal sequence of 21 amino acids is present with a predicted cleavage site after Ala-21. N-terminal sequences of the native and cloned chitinases perfectly matched the sequence starting from Val-22 of the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the chiC gene, indicating that the cleavage site occurred between Ala-21 and Val-22. The deduced mature protein consequently has a length of 409 amino acids with a calculated molecular weight of 44,452. This value is in good agreement with those of the purified native and cloned enzymes, with a molecular mass of 45 kDa (Fig. 3). The potential ribosome-binding sequence for the chiC gene, GGAA, was found upstream the start codon, although this sequence is not perfectly complementary to the 3′ end of the 16S rRNA of E. coli (28). DNA sequence containing an AT-rich region, characteristic of the promoter sequence, was found upstream of the ribosome binding site. The inverted repeat, which was composed of a 6-bp stem and a loop of 3 bases, was located downstream of the chitinase terminal codon (TAA). This sequence is a putative rho-independent transcription terminator.

FIG. 2.

Nucleotide sequence of the chiC gene. The putative ribosome-binding site (GGAA) is boxed. The −10 and −35 regions of a possible promoter sequence are double-underlined. The deduced amino acid sequence of ChiC is given below the nucleotide sequence. The N-terminal sequences of the native and cloned ChiC are underlined. The signal peptide cleavage site is shown by an arrow. The amino acid residues which seem to be essential for chitinase activity are circled. The stop codon is indicated by asterisks. The inverted repeat sequence is indicated by facing arrows with solid lines.

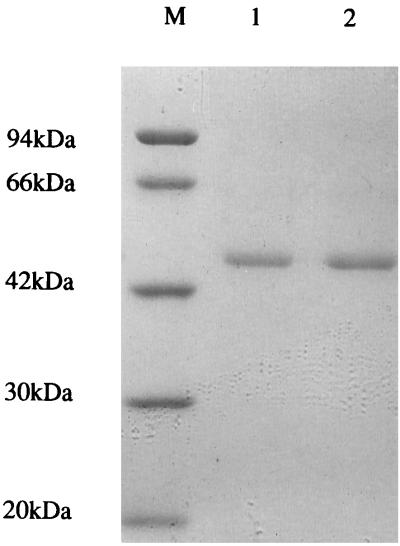

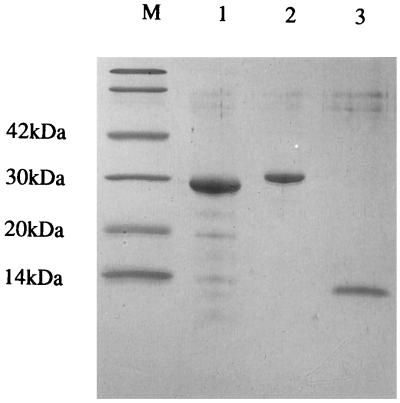

FIG. 3.

SDS-PAGE of the cloned and native chitinases. Lane M contains molecular size standards: phosphorylase b (94 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), ovalbumin (42 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), and trypsin inhibitor (20.1 kDa). Lanes 1 and 2 correspond to the native ChiC from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 and the cloned ChiC, respectively.

Domain structure of ChiC.

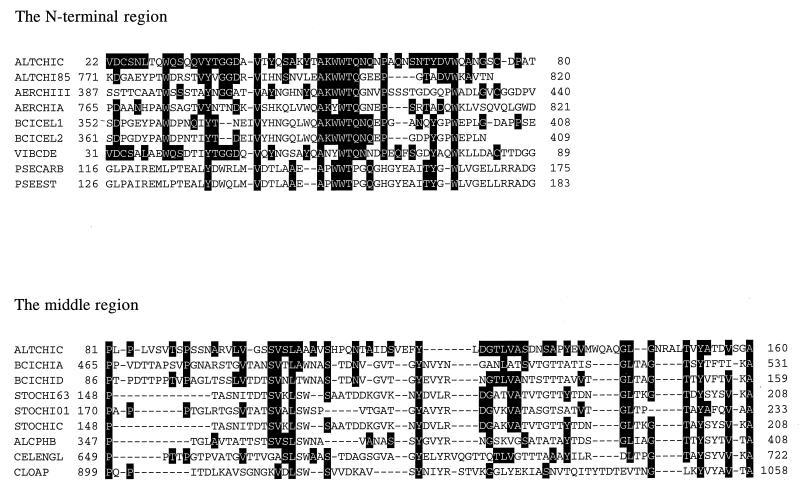

Computer analysis with the deduced mature amino acid sequence of ChiC revealed interesting features consisting of three discrete domains (Fig. 1). Interestingly, the N-terminal region of ChiC (residues 22 to 80) was similar to that found in the C-terminal extension of ChiA (residues 771 to 820) of this strain (37) and, furthermore, showed significant sequence homology to the regions found in chitinase II (residues 387 to 440) from Aeromonas sp. strain 10S-24 (40), chitinase A (residues 765 to 821) from Aeromonas caviae (29), two cellulases (residues 352 to 408 and residues 361 to 409) from the alkalophilic Bacillus sp. strain N-4 (6), chitodextrinase (residues 31 to 89) from Vibrio furnissii (11), carboxylesterase (residues 116 to 175) from Pseudomonas fluorescens (12), and esterase (residues 126 to 183) from Pseudomonas sp. strain LS107d2 (18) (Fig. 4). In particular, six continuous amino acids (A-K-W-W-T-Q) and four amino acid residues (W, Y, V, and P) were well conserved in Alteromonas chitinases (ChiA and ChiC), Aeromonas chitinase II, and Bacillus cellulases that degrade insoluble polysaccharides such as chitin or cellulose.

FIG. 4.

Alignment of the N-terminal and middle regions of ChiC with those of other enzymes. The sequences of the N-terminal and middle regions of ChiC (ALTCHIC) are aligned with those of Alteromonas chitinase 85 (ALTCHI85), Aeromonas chitinase II (AERCHIII), Aeromonas chitinase A (AERCHIA), Bacillus cellulase 1 (BCICEL1), Bacillus cellulase 2 (BCICEL2), Vibrio chitodextrinase (VIBCDE), Pseudomonas carboxyesterase (PSECARB), Pseudomonas esterase (PSEEST), Bacillus chitinase A (BCICHIA), Bacillus chitinase D (BCICHID), Streptomyces chitinase 63 (STOCHI63), Streptomyces exochitinase (STOCHI01), Streptomyces chitinase C (STOCHIC), Alcaligenes poly-3-hydroxybutyrate depolymerase (ALCPHB), Cellulomonas endoglucanase B (CELENGL), and Clostridium α-amylase–pullulanase (CLOAP). Identical amino acids are indicated by white on black.

The middle region (residues 81 to 160) showed similarity to the fibronectin type III-like sequences found in chitinases A and D from Bacillus circulans (41, 42), chitinase 63 from Streptomyces plicatus (24), exochitinase from S. olivaceoviridis (2), chitinase C from S. lividans (5), poly-3-hydroxybutyrate depolymerase from Alcaligenes faecalis (25), CenB from Cellumonas fimi (19), and α-amylase-pullulanase from Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum (20) (Fig. 4).

The C-terminal region (residue 161 to 430) showed similarity to catalytic domains of chitinases which belong to family 18 including fungus, animal, and bacterial chitinases as well as plant chitinases of classes III and V. In particular, the region showed high sequence similarity to Manduca sexta chitinase (54.4% identity) (15), Serratia marcescens chitinase B (46.7% identity) (8), Streptomyces plicatus endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (40.9% identity) (23), and Brugia malayi chitinase (35.9% identity) (4). In this region, two aspartic acids and glutamic acid essential for the activity of ChiA of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 (39) or chitinase A1 of B. circulans (43), which are highly conserved in bacterial chitinases, fungal chitinases, and class III and V chitinases of higher plants were found. Furthermore, two amino acid residues corresponding to Asp-391 and Glu-315 of chitinase A of S. marcescens (22) involved in the acid-base catalysis of chitin were also found. Thus, the region was considered to be a catalytic domain of ChiC. We could not find out the typical linker sequences, such as serine- and proline-rich linker sequence, between the above-mentioned domains.

Purification of ChiC.

To clarify the role of ChiC in the chitinolytic system of Alteromonas sp. strain O-7, we purified the enzyme. The enzyme was not detected in the culture supernatant after 16 h of cultivation of the strain, whereas the enzyme activity existed in a conjugated state in the chitin molecule. However, after 2 days of growth, chitin was completely degraded and ChiC was not found in the culture supernatant. Therefore, we determined that the suitable condition for purification of ChiC was 16 h of cultivation at 27°C. To release ChiC bound to the chitinous substrate, the chitin was treated with low-salt buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, [pH 8.0]), high-salt buffer containing 1 M NaCl, water, or 6 M guanidine hydrochloride. Of these, only guanidine hydrochloride eluted the enzyme effectively from the chitin. The eluate was dialyzed several times against 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) at 4°C to renature the proteins. The supernatant of the dialyzate was applied to a DEAE-Toyopearl column and was separated into two peaks; one was eluted at about 0.4 M NaCl, and the other was eluted at about 0.55 M NaCl. The first peak contained 65-kDa chitinase (ChiA), 35-kDa chitinase (ChiB), and 30-kDa chitinase (ChiD), and the second peak contained 45-kDa chitinase (ChiC) (data not shown). The fraction containing ChiC was further purified by gel filtration chromatography and FPLC. The cloned enzyme was purified from the periplasmic space of E. coli carrying the chiC gene by the same procedure as the native enzyme. These enzymes showed a single band on SDS-PAGE, and their molecular sizes were 45 kDa (Fig. 3). N-terminal sequences of the native and cloned enzymes were found to be identical (V-D-X-S-N-L-T-Q-W-Q-S-Q-Q-V-Y-T-G-G-, where X is an unidentified amino acid). This sequence is in good agreement with the sequence deduced from the nucleotide sequence chiC gene. The optimum pH and temperature of ChiC (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer) were 8.0 and 60°C, respectively. The temperature optima of chitinases isolated from mesophilic bacteria usually fall into the range of 50 to 60°C. HPLC analysis revealed N,N′-diacetylchitobiose as a major product and N-acetylglucosamine and N,N′,N"-triacetylchitotriose as minor products of hydrolysis of colloidal chitin. ChiC hydrolyzed chitooligosaccharides from the trimer to the hexamer to give N,N′-diacetylchitobiose as the main product, but it did not further hydrolyze N,N′-diacetylchitobiose. Furthermore, the relative rate of ChiC hydrolysis of chitooligosaccharides from trimer to hexamer was examined. ChiC rapidly hydrolyzed the trimer, and its level showed a tendency to decrease with an increase in the degree of polymerization. The relative rates of ChiC hydrolysis of chitotriose, chitotetraose, chitopentaose, and chitohexaose were 100, 46, 27, and 15, respectively.

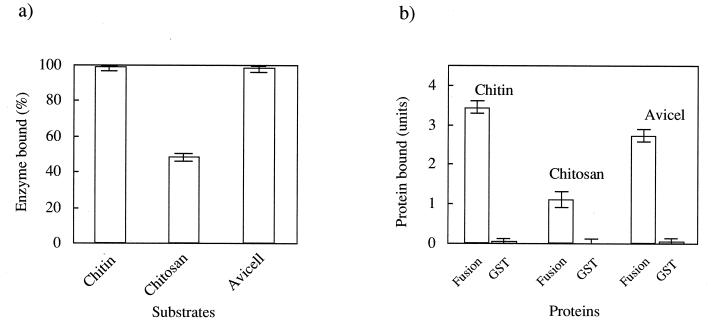

Binding of ChiC to polysaccharides.

ChiC adhered strongly to chitin after secretion from Alteromonas cells. To assess whether the binding of the enzyme to chitin is specific, the capacity of ChiC to bind polysaccharides such as chitin, chitosan, and Avicel was evaluated. The enzyme bound to chitin and Avicel to the same extent, although the enzyme bound much less strongly to chitosan, as shown in Fig. 5. These results indicate that the binding of ChiC has a relatively broad affinity for insoluble polysaccharides.

FIG. 5.

Binding assays of ChiC and GST fusion protein. (a) Binding of ChiC to chitin, chitosan, and Avicel. (b) Binding of GST fusion protein to chitin, chitosan, and Avicel. Data are from five independent experiments; standard errors are indicated by vertical lines.

Construction of fusion protein.

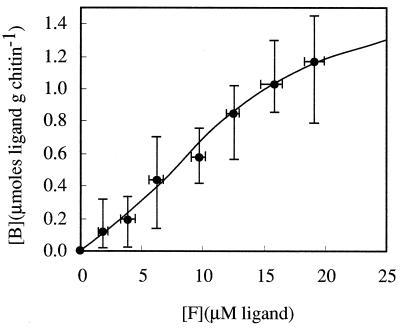

Judging from the relationship between the domain structure and function of each domain, it seems most probable that the 59-residue N-terminal domain is involved in chitin binding of ChiC. To evaluate the role of the N-terminal domain of ChiC, expression of the gene for the noncatalytic domain as a fusion protein in E. coli was performed. The hybrid gene produced a fusion protein with the domain coding sequence subcloned in frame after the 3′ end of the coding sequence of GST protein (Mr, 27,000). The fusion protein with a molecular weight of 34,000 that exhibited GST activity was purified by single-step affinity chromatography with glutathione-Sepharose 4B (Fig. 6). When the protein (3.5 U) was incubated with chitin, chitosan, and Avicel, 3.4, 1.1, and 2.7 U of GST activity were retained by the polysaccharides, respectively (Fig. 5). In contrast, when GST alone was incubated with these polysaccharides, no GST activity was retained. Furthermore, the adsorption of the N-terminal domain itself to chitin was performed (Fig. 7). It was confirmed that the domain also bound to chitin. The adsorption of the domain to chitin increased with increasing ratios of the N-terminal domain to chitin; however, saturation of chitin by the N-terminal domain was not attained at the highest polypeptide concentration used in this experiment, indicating a complex interaction of the N-terminal domain with chitin. Repeated washes with low-salt buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 8.0]), high-salt buffer containing 1 M NaCl, or water did not desorb the fusion protein or the N-terminal domain from chitin or Avicel in the same manner as ChiC did. These results indicate that the N-terminal domain of ChiC constitutes an independent chitin-binding domain.

FIG. 6.

SDS-PAGE of GST, GST fusion protein, and the N-terminal region of ChiC. Lane M contains molecular size standards: ovalbumin (42 kDa), carbonic anhydrase (30 kDa), trypsin inhibitor (20 kDa), and lysozyme (14.4 kDa). Lanes 1 to 3 correspond to GST, GST fusion protein, and the N-terminal region of ChiC.

FIG. 7.

Adsorption of the isolated domain to chitin. The figure shows the equilibrium adsorption isotherms ([B] versus [F]). Each datum point is from six independent experiments; standard errors are indicated by vertical bars.

DISCUSSION

We suppose that Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 converts chitin to GlcNAc to utilize chitin as a source of carbon and nitrogen by at least four chitinases (ChiA, ChiB, ChiC, and ChiD) and three GlcNAcases (GlcNAcaseA, GlcNAcaseB, and GlcNAcaseC) with different specificities and modes of action. In this paper, we describe the purification of ChiC from this strain and the isolation and nucleotide sequencing of the encoding gene. The chiC gene encoded a protein consisting of 430 amino acids. Comparison of the deduced amino acid sequence of ChiC with those of other related enzymes revealed that the gene product is composed of three discrete domains: the chitin-binding domain, the fibronectin type III-like domain, and the catalytic domain. The N-terminal 21 amino acid residues showed the typical features of signal peptides, which are composed of a positively charged region, a hydrophobic region, and a signal sequence cleavage site. The N-terminal sequences of the native and cloned ChiC coincided precisely with the sequence starting from Val-22 of the deduced amino acid sequence encoded by the gene. These results indicate that the signal sequence of Alteromonas is recognized by the E. coli secretion machinery and that ChiC is then secreted into the periplasm with the concomitant removal of the signal peptide by E. coli signal peptidase. After secretion to the milieu from the cells, the native ChiC binds to chitin molecules; however, we do not know the mechanism for exporting the chitinase across the outer membrane of Alteromonas.

The sequence consisting of the following 59 amino acid residues showed sequence similarity to the regions found in Aeromonas chitinases (29, 40), Bacillus cellulases (6), and Pseudomonas esterases (12, 18). It is unclear, however, why Pseudomonas esterase, involved in lipolytic spoilage, contains the sequence. Furthermore, the similar domain was also found in the C-terminal region of ChiA of this strain (37). At present, we are investigating whether the domain is also retained in the sequences of ChiB and ChiD. However, the function of the region is unknown. Thus, to evaluate the role of the domain of ChiC, we constructed the hybrid gene directing the synthesis of the fusion protein that exhibited glutathione activity. Both the fusion protein and the N-terminal domain bound not only to chitin but also to Avicel. Chitin and cellulose are structurally similar; however, the mechanism of adsorption to chitin or Avicel is still unknown, but the conservation of aromatic amino acids in the domain, especially the well-conserved tryptophan and tyrosine residues, seems to play crucial roles in binding to the polysaccharides. Chitinases from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (16), tobacco (9), and Bacillus circulans (41, 42) have been shown to contain the chitin-binding domain in their sequences. Furthermore, the N-terminal regions of chitinase C from Streptomyces lividans (5) and of chitinase 63 from S. plicatus (24) were similar to the family II cellulose-binding domains (CBD), which are the most common ancillary domains in cellulases and xylanases, but their affinities for chitin and cellulose have not been experimentally investigated. At present, CBDs are grouped into nine different families based on sequence similarities (30). Comparison of these chitin- or cellulose-binding domains so far reported with that of ChiC revealed no significant similarity. These results indicate that the sequence is probably a novel type of chitin-binding domain or CBD. The hydrolyzing activity of chitinase lacking the C-terminal chitin-binding domain of chitinase A1 from B. circulans was shown to be less than half that of the intact enzyme; in contrast, deletion of the C-terminal chitin-binding domain of Saccharomyces chitinase resulted in an enhanced rate of chitin hydrolysis. In tobacco chitinase, the native form with the chitin-binding domain was about three times more effective than the one without it, although both chitinases were capable of inhibiting the growth of Trichoderma viride. Thus, the functions of the chitin-binding domains seem to be different in individual chitinases. Four chitinases from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 were recovered from chitin, indicating that in an aquatic environment these enzymes probably need to bind to the chitin molecule in order to effectively degrade the substrate and utilize it as a nutrient source. The precise role of the chitin-binding domain of ChiC in chitin degradation remains to be examined by deletion experiments.

The next domain consisting 100 amino acids showed similarity to the fibronectin type III sequence. The cell-binding domain of fibronectin has been the most extensively studied region among the many sites in extracellular matrix protein. This region consists of repeating units approximately 90 amino acid residues in length, termed fibronectin type III repeats (13). Comparison of the fibronectin type III domain of ChiC with those of other microbial carbohydrases showed conservation of several amino acid residues such as Pro, Leu, Tyr, and Ala. The type III domain of chitinase A1 did not affect the chitin-binding activity, but the colloidal chitin-hydrolyzing activity decreased (43). Similarly, regardless of the existence of the type III domain, the poly-3-hydroxybutyrate depolymerase with a deletion of approximately 60 amino acids from the C terminus (perhaps a substrate-binding domain) was shown to lose substrate-binding capability and activity against insoluble substrates (25). In contrast, chitinases from Streptomyces erythraeus (10) and S. thermoviolaceus (38) consist of only the catalytic domain. Taking the results together, the type III module is not essential for chitinase activity and chitin binding. Therefore, the precise function of the type III module remains unclear in spite of its wide distribution in baterial carbohydrases, although functions such as binding to other proteins involved in chitin degradation systems or the cell might be presumed.

The last domain at the C terminus of ChiC showed sequence homology to the catalytic domain of chitinases which belong to family 18 of glycosyl hydrolases. The multiplicity of the chitinases from Alteromonas sp. strain O-7 is generated by a combination of multiple genes (at least four genes [unpublished data]). ChiC showed no significant homology to ChiA except for the two small catalytic regions conserved from prokaryote to eukaryote. Furthermore, enzymatic properties, such as pH and temperature optima, and substrate specificities are significantly different between ChiA and ChiC (33). In particular, ChiA displayed slow and detectable activity with (GlcNAc)3, but ChiC most rapidly hydrolyzed the chitooligosaccharide trimer to a hexamer. These results suggest that these enzymes function cooperatively in the chitin degradation system of this strain.

Microbial and plant chitinases contain various combinations of discrete functional domains. The elements such as a substrate-binding domain and/or fibronectin type III domain are found in enzymes classified into different families. These events suggest that the enzymes that hydrolyze insoluble polysaccharides such as chitin, cellulose, and xylan appear to have arisen from a limited number of progenitor sequences by fusion and shuffling of domains.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bassler B L, Yu C, Lee Y C, Roseman S. Chitin utilization by marine bacteria: degradation and catabolism of chitin oligosaccharides by Vibrio furnissii. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24276–24286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blaak H, Schnellman J, Walter S, Henrissat B, Schrempf H. Characteristics of an exochitinase from Streptomyces olivaceoviridis, its corresponding gene, putative protein domains and relationship to other chitinases. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:659–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17966.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fuhrmam J A, Lane W S, Smith R F, Piessens W F, Perler F B. Transmission-blocking antibodies recognize microfilarial chitinase in brugian lymphatic filariasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:1548–1552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fujii T, Miyashita K. Multiple domain structure in a chitinase gene (chiC) of Streptomyces lividans. J Gen Microbiol. 1993;139:677–686. doi: 10.1099/00221287-139-4-677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukumori F, Sashihara N, Kudo T, Horikoshi K. Nucleotide sequences of two cellulase genes from alkalophilic Bacillussp. strain N-4 and their strong homology. J Bacteriol. 1986;168:479–485. doi: 10.1128/jb.168.2.479-485.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gill S C, von Hippel P H. Calculation of protein extinction coefficients from amino acid sequence data. Anal Biochem. 1989;182:319–326. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90602-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harpster M H, Dunsmuir P. Nucleotide sequence of the chitinase B gene of Serratia marcescensQMB 1466. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:5395. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.13.5395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iseli B, Boller T, Neuhaus J-M. The N-terminal cysteine-rich domain of tobacco class I chitinase is essential for chitin binding but not for catalytic or antifungal activity. Plant Physiol. 1993;103:221–226. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamei K, Yamamura Y, Hara S, Ikenaka T. Amino acid sequence of chitinase from Streptomyces erythraeus. J Biochem. 1989;105:979–985. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a122791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keyhani N O, Roseman S. The chitin catabolic cascade in the marine bacterium Vibrio furnissii. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y S, Lee H B, Choi K D, Park S, Yoo O J. Cloning of Pseudomonas fluoresecens carboxyesterase gene and characterization of its product expressed in Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1994;58:111–116. doi: 10.1271/bbb.58.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kornblihtt A R, Umezawa K, Vibe P K, Baralle F E. Primary structure of human fibronectin: differential splicing may generate at least 10 polypeptides from a single gene. EMBO J. 1985;4:1755–1759. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03847.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koshland D, Botstein D. Secretion of beta-lactamase requires the carboxy end of the protein. Cell. 1980;20:749–760. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90321-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kramer K J, Corpuz L, Choi H K, Muthukrishnan S. Sequence of a cDNA and expression of the gene encoding epidermal and gut chitinases of Manduca sexta. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;23:691–701. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(93)90043-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuranda M J, Robbins P W. Chitinase is required for cell separation during growth of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19758–19767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature (London) 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McKay D B, Jennings M P, Godfrey E A, MacRae I C, Rogers P J, Beacham I R. Molecular analysis of an esterase-encoding gene from a lipolytic psychrotrophic pseudomonad. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:701–708. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-4-701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meinke A, Braun C, Gilkes N R, Kilburn D G, Miller R C, Jr, Warren R A. Unusual sequence organization in CenB, an inverting endoglucanase from Cellulomonas fimi. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:308–314. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.1.308-314.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melasniemi H, Paloheimo M, Hemio L. Nucleotide sequence of the alpha-amylase-pullulanase gene from Clostridium thermohydrosulfuricum. J Gen Microbiol. 1990;136:447–454. doi: 10.1099/00221287-136-3-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muzzarelli R A A. Advances in N-acetyl-β-d-glucosaminidases. In: Muzzarelli A A, editor. Chitin enzymology. Ancona, Italy: European Chitin Society; 1993. pp. 357–373. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perrakis A, Tews I, Dauter Z, Chet I, Oppenheim A B, Wilson K S, Vorgias C. Crystal structure of a bacterial chitinase at 2.3 A resolution. Structure. 1994;2:1169–1180. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(94)00119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robbins P W, Trimble R B, Wirth D F, Hering C, Maley F, Maley G F, Das R, Gibson B W, Royal N, Biemann K. Primary structure of the Streptomycesenzyme endo-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase H. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:7577–7583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robbins P W, Overbye K, Albright C, Benfield B, Pero J. Cloning and high-level expression of chitinase-encoding gene of Streptomyces plicatus. Gene. 1992;111:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(92)90604-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saito T, Suzuki K, Yamamoto J, Fukui T, Miwa K, Tomita K, Nakanishi S, Odani S, Suzuki J-I, Ishikawa K. Cloning, nucleotide sequence, and expression in Escherichia coli of the gene for poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) depolymerase from Alcaligenes faecalis. J Bacteriol. 1989;171:184–189. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.1.184-189.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shine J, Dargarno L. The 3′ terminal sequence of E. coli16S rRNA: complementarity to nonsense triplets and ribosome binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:1342–1346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.4.1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sitrit Y, Vorgias C E, Chet I, Oppenheim A B. Cloning and primary structure of the chiA gene from Aeromonas caviae. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:4187–4189. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.14.4187-4189.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tomme P, Warren R A J, Gilkes N R. Cellulase degradation by bacteria and fungi. Adv Microb Physiol. 1995;37:1–81. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2911(08)60143-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tracey M V. Chitin. Rev Pure Appl Chem. 1957;7:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujibo H, Yoshida Y, Imada C, Okami Y, Miyamoto K, Inamori Y. Isolation and characterization of a chitin degrading marine bacterium belonging to the genus Alteromonas. Nippon Suisan Gakkaishi. 1991;57:2127–2131. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsujibo H, Yoshida Y, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Purification, properties, and partial amino acid sequence of chitinase from a marine Alteromonassp. strain O-7. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:891–897. doi: 10.1139/m92-145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsujibo H, Fujimoto K, Kimura Y, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Purification and characterization of β-acetylglucosaminidase from Alteromonassp. strain O-7. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1995;59:1135–1136. doi: 10.1271/bbb.59.1135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsujibo H, Fujimoto K, Tanno H, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Gene sequence, purification and characterization of N-acetyl-β-glucosaminidase from a marine bacterium, Alteromonassp. strain O-7. Gene. 1994;146:111–115. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(94)90843-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsujibo H, Fujimoto K, Tanno H, Miyamoto K, Kimura Y, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Molecular cloning of the gene which encodes β-N-acetylglucosaminidase from a marine bacterium, Alteromonassp. strain O-7. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:804–806. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.2.804-806.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsujibo H, Orikoshi H, Tanno H, Fujimoto K, Miyamoto K, Imada C, Okami Y, Inamori Y. Cloning, sequence, and expression of a chitinase gene from a marine bacterium, Alteromonassp. strain O-7. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:176–181. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.1.176-181.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tsujibo H, Endo H, Minoura K, Miyamoto K, Inamori Y. Cloning and sequence analysis of the gene encoding a thermostable chitinase from Streptomyces thermoviolaceusOPC-520. Gene. 1993;134:113–117. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90183-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsujibo H, Orikoshi H, Imada C, Okami Y, Miyamoto K, Inamori Y. Site-directed mutagenesis of chitinase from Alteromonassp. strain O-7. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 1993;57:1396–1397. doi: 10.1271/bbb.57.1396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ueda M, Kawaguchi T, Arai M. Molecualr cloning and nucleotide sequence of the gene encoding chitinase II from Aeromonassp. 10S-24. J Ferment Bioeng. 1994;78:205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watanabe T, Oyanagi W, Suzuki K, Ohnishi K, Tanaka H. Structure of the gene encoding chitinase D of Bacillus circulansWL-12 and possible homology of the enzyme to other prokaryotic chitinases and class III plant chitinases. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:408–414. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.2.408-414.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Watanabe T, Ito Y, Yamada T, Hashimoto M, Sekine S, Tanaka H. The roles of the C-terminal domain and type III domains of chitinase A1 from Bacillus circulansWL-12 in chitin degradation. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:4465–4472. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.15.4465-4472.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watanabe T, Kobori K, Miyashita K, Fujii T, Sakai H, Uchida M, Tanaka H. Identification of glutamic acid 204 and aspartic acid 200 in chitinase A1 of Bacillus circulansWL-12 as essential residues for chitinase activity. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:18567–18572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu C, Lee A M, Bassler B L, Roseman S. Chitin utilization by marine bacteria. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:24260–24266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]