Abstract

Kratom, (Mitragyna Speciosa Korth.) is a plant indigenous to Southeast Asia whose leaves are cultivated for a variety of medicinal purposes and mostly consumed as powders or tea in the United States. Kratom use has surged in popularity with the lay public and is currently being investigated for possible therapeutic benefits including as a treatment for opioid withdrawal due to the pharmacologic effects of its indole alkaloids. A wide array of psychoactive compounds are found in kratom, with mitragynine being the most abundant alkaloid. The drug-drug interaction (DDI) potential of mitragynine and related alkaloids have been evaluated for effects on the major cytochrome P450s (CYPs) via in vitro assays and limited clinical investigations. However, no thorough assessment of their potential to inhibit the major hepatic hydrolase, carboxylesterase 1 (CES1), exists. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the in vitro inhibitory potential of kratom extracts and its individual major alkaloids using an established CES1 assay and incubation system. Three separate kratom extracts and the major kratom alkaloids mitragynine, speciogynine, speciociliatine, paynantheine, and corynantheidine displayed a concentration-dependent reversible inhibition of CES1. The experimental values were determined as follows for mitragynine, speciociliatine, paynantheine, and corynantheidine: 20.6, 8.6, 26.1, and 12.5 μM respectively. Speciociliatine, paynantheine, and corynantheidine were all determined to be mixed-type reversible inhibitors of CES1, while mitragynine was a purely competitive inhibitor. Based on available pharmacokinetic data, determined Ki values, and a physiologically based inhibition screen mimicking alkaloid exposures in humans, a DDI mediated via CES1 inhibition appears unlikely across a spectrum of doses (i.e., 2–20g per dose). However, further clinical studies need to be conducted to exclude the possibility of a DDI at higher and extreme doses of kratom and those who are chronic users.

Keywords: CES1, Mitragyna Speciosa, kratom alkaloids, mitragynine

Introduction

Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth.) is a tree indigenous to Southeast Asia where its leaves are cultivated to alleviate exhaustion, partake in recreational activities, increase efficiency while working outside and medicinal purposes such as treating opium addiction [1–5]. Despite its bitter taste, kratom leaves are commonly consumed as a brewed tea, but its leaves can also chewed [1–3]. A 2021 cross sectional study estimated usage of kratom within the previous year to be 0.8% and a life-time prevalence of kratom usage at 1.3% in the U.S. [6]. Kratom is available in several forms (i.e., powder, tablets, tea) and according to a survey of kratom users in the United States (US), the most common ways kratom is consumed is as a powder with a drink, a pure powder or in a pill, and as a self-made tea [7]. Typical doses of kratom range anywhere from 1–8g of powder per dose with most users report taking 1–48 doses per week, suggesting most users consume 1–6 doses per day [7]. Kratom purportedly produces dose-dependent pharmacodynamic effects, wherein low dose (1–5g) users report experiencing stimulant-like effects and moderate to high dose (5–15g) users report experience opioid like effects [8].

Kratom is not a singular chemical entity, rather it is a complex mixture of compounds including a number of psychoactive indole alkaloids that are responsible for its pharmacological effects [8]. There have been over 40 identified kratom alkaloids but some of the most studied are mitragynine, 7-hydroxymitragynine, speciociliatine, corynantheidine, speciogynine, and paynantheine [9]. Of these alkaloids, mitragynine is the predominant alkaloid in kratom extracts at 2% and makes up over 60% of the alkaloid content [9]. Of these alkaloids, mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine are primarily considered the most significant in terms of pharmacological activity. Mitragynine and 7-hydroxymitragynine have displayed varying affinities to the different opioid receptors (i.e., μ- opioid receptor); however, 7-hydroxymitragynine has demonstrated more potent affinities than morphine and mitragynine [10–16].

Hepatic drug metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) include the cytochrome P450s (CYPs), UDP-glucuronyltransferases (UGTs), sulfotransferases and esterases. Carboxylesterase 1 (CES1), a serine hydrolase catalyzes the hydrolysis of numerous xenobiotics and endogenous compounds containing ester, amide and thioester functional groups [17]. CES1 is the most abundant DME in the liver [18,19], and is also expressed in significant amounts in the lungs and kidney [19]. A wide range of therapeutic agents serve as substrates of CES1 including antiplatelet agents (e.g. clopidogrel), antiviral compounds (e.g. oseltamivir), psychostimulants (e.g. methylphenidate) and more [20]. Indeed, there has been extensive in vitro investigations and at least one clinical investigation assessing the impact of CES1 inhibition [21–23]. However, the G143E CES1 loss of function variant has been shown to significantly impact the metabolism and elimination of several medications such as methylphenidate, clopidogrel, oseltamivir, and dabigatran [24–31] and it could be speculated that a potent enough inhibitor of CES1 could result in similar effects.

Kratom and its alkaloids have undergone extensive in vitro evaluation for their inhibition potential against various CYP enzymes and one UGT [32–37]. From these studies, kratom extracts and its major alkaloids, namely mitragynine, principally inhibit CYP2D6 and 3A. Only one clinical study has been conducted assessing the inhibition potential of kratom against CYP3A and CYP2D6 activity in healthy human volunteers [38]. At a 2g dose of kratom, it was found that kratom had no effect on the CYP2D6, but modest inhibitory effects on CYP3A, resulting in an increased AUC and of midazolam [38]. Mitragynine has previously shown to be metabolized by CES1 to a metabolite: 16-COOH mitragynine [39]. While there have been no formal in vitro CES1 inhibition investigations with kratom’s extracts or alkaloids, a study involving the coadministration of kratom and the CES substrate permethrin to adult male rats demonstrated reduced permethrin metabolism and elimination [40]. The present study provided a rigorous in vitro investigation of the ability of kratom extracts and its major alkaloids to inhibit CES1 at physiologically relevant concentrations.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Oseltamivir phosphate (OST) and ritalinic acid was purchased from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI). Oseltamivir carboxylate (OC) was purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals Inc. (North York, ON, Canada). PBS was purchased from Corning (Manassas, VA). Plant material for kratom extract A was provided gratis by the University of Florida Foundation. Plant material for kratom extract B was obtained from gardens of the National Center for Natural Products Research, University of Mississippi, University, MS, USA [41]. Plant material for kratom extract C were provided gratis by a vendor located in Hawaii. Kratom tea was prepared as described previously and was designated extract D [42]. All kratom alkaloids were isolated or synthesized with a purity of >98% as described previously (Fig.1) [42]. All other materials were commercially available chemical reagents of the highest analytical purity.

Figure 1. Kratom alkaloid structures.

Prominent kratom alkaloids and metabolites with their respective molecular weights employed in inhibition studies.

Preparation of CES1 Wildtype Cell S9 fractions.

The preparation of CES1 wildtype S9 fractions has been previously described [24]. In brief, wild type CES1 was cultured from human embryonic kidney cells (Flp-In-293; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s Medium with 10% FBS, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1% Pen-Strep, and 100 μg/mL hygromycin. After visual inspection confirmed at least 80% confluence, the cells were promptly harvested and suspended in PBS. To free the enzyme from the membrane, collected cells were sonicated and subsequently centrifuged for 30 min at 9000g and 4°C. CES1 S9 fractions were collected by obtaining the resulting supernatant from centrifugation and transferring it to 1.5 mL Protein Lobind tubes (Eppendorf Tubes®). Total protein concentrations were quantified utilizing a Pierce BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific) and S9 fractions were stored in a −70°C freezer until use.

CES1 Substrate Metabolism.

The antiviral drug, oseltamivir phosphate (OST), is an established CES1 probe substrate that has been utilized in previous studies [21,22,43,44]. Through CES1-mediated hydrolysis, OST is converted to oseltamivir carboxylate (OC), its active moiety (Fig.2). A final reaction volume of 100 μL in 2 mL centrifuge tubes was kept on ice, minimizing spontaneous OST hydrolysis to OC, and contained varying amounts of OST and S9, which were both separately prepared using a 50 mM phosphate buffer solution. After preparation, to initiate the reaction of OST to OC, all 2 mL centrifuge tubes were placed in a 37°C water bath and incubated for a designated period. As determined previously, subsequent studies demonstrated linearity of product formation over a designated enzyme concentration range (0–80 μg/mL) and a designated incubation time range (10–20 min). For all subsequent inhibition studies, an enzyme concentration of 20 μg/mL and incubation time of 15 min were employed [21,22]. To terminate the reaction, samples were removed and immediately placed on ice followed by the addition of a 4-fold volume of stop solution that consisted of acetonitrile and internal standard (50 nM ritalinic acid). To separate out the protein, samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 16,100g and 4°C. The resulting supernatant was gathered (50 μL) and was further diluted with a 3-fold volume of a solution containing 50% water and 50% acetonitrile and 1% formic acid, which was transferred to glass inserts in vials for liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis described below.

Figure 2. Absorption and metabolism of CES1 substrate oseltamivir phosphate.

Conversion of OST to OC in liver hepatocytes after an oral administration of oseltamivir.

Preparation of kratom extracts and alkaloids for subsequent inhibition studies.

All investigated kratom extracts and alkaloids were provided initially as powders in amber tubes. Extracts A, B, and C were determined to be soluble in ethanol, while extract D was determined to be soluble in water. 500 μL of appropriate solvent was added and samples were vortex-mixed for a minimum of 10 min. After vortex-mixing, all extracts were withdrawn using a glass needle equipped with a 0.22 μm nylon filter to remove the insoluble plant fibers from each extract. Due to ethanol’s known ability to inhibit CES1 [45], 200 μL of each ethanolic extract were placed in separate amber centrifuge tubes and were dried using a gentle stream of nitrogen. After the ethanol was evaporated to dryness, 200 μL of DMSO was added to reconstitute the extracts which were promptly vortex-mixed for 1 min. A comprehensive assessment of major alkaloid content of each extract can be found in Supplemental Table 1. All kratom alkaloids and 16-COOH mitragynine were determined to be soluble in DMSO. 500 μL of DMSO was added to each kratom alkaloid powder and samples were promptly vortex-mixed for at least 10 min.

Screening of select kratom extracts and kratom alkaloids for inhibition of CES1.

An initial screen of four select kratom extracts designated as extracts: A, B, C, and D, major kratom alkaloids, and 16-COOH mitragynine (a metabolite of mitragynine) were investigated for their inhibitory potential of CES1. All extracts and alkaloids were dissolved in DMSO, while extract D was dissolved in water. The extracts and alkaloids were screened at 3 different concentrations (extracts: 1, 10 and 100 μg/mL; alkaloids and metablite: 1, 10, and 100 μM). A final 100 μL reaction mixture containing 200 μM OST and 1% solvent was incubated as described previously. 10 μM of betulinic acid and 3.18 μM of cannabidiol in DMSO served as positive controls. CES1 activity in the presence of each kratom extract or alkaloid were quantified relative to a negative control containing only 1% solvent, which was expressed as a percentage.

Finally, a concentration response curve was generated for kratom extracts and alkaloids that displayed a >50% inhibition of CES1. Each kratom extract (0–128 μg/mL) and kratom alkaloid (0–128 μM) were individually incubated with CES1 S9, 200 μM OST, with 1% DMSO comprising of the final reaction mixture (100 μL). Negative controls contained only 1% DMSO. All samples were incubated as previously described and analyzed by LC-MS/MS as described below.

Assessment of Time-Dependent Inhibition of CES1 by select kratom extracts and select kratom alkaloids.

Each extract or alkaloid that had their concentration response curve evaluated, was also evaluated as a possible time-dependent inhibitor of CES1. Each kratom extract (0–128 μg/mL) and kratom alkaloid (0–128 μM) were individually preincubated for 30 min only with CES1 S9 fractions. The preincubation group contained 0.5% final concentration of kratom extracts or alkaloids dissolved in DMSO that were added to a phosphate buffer solution with only CES1 S9. The no preincubation group contained 0.5% DMSO that was added to a phosphate buffer solution with CES1 S9 fractions and was simultaneously preincubated. Upon completion of a 30 min incubation, samples were removed from the incubator and cooled on ice. A 0.5% final concentration of kratom extract or alkaloid in DMSO was added to the no preincubation group, while 0.5% final concentration DMSO was added to the preincubation group achieving a 1% final concentration of DMSO among both groups. Substrate was subsequently added resulting in a final 100 μL reaction mixture containing 200 μM OST, 1% DMSO, kratom extract or alkaloid, and CES1 S9. All samples proceeded through the incubation process and were terminated with stop solution as described above and underwent LC-MS/MS evaluation.

In Vitro Inhibition Study of Select Kratom Alkaloids.

For all alkaloids that achieved an of < 50 μM, the inhibition constant (Ki) and type of reversible inhibition was determined. Substrate concentrations ranging from 0 to 10,000 μM were used along with kratom alkaloid concentrations of 0 to 100 μM. The total reaction volume was 100 μL containing 1% DMSO, while the negative control contained 1% DMSO only. All reactions proceeded through the incubation system described above. All samples were kept on ice prior to the incubation period to minimize premature product formation of OC. All reactions were terminated with stop solution and all samples underwent LC-MS/MS evaluation.

A Physiological Concentration Screen of a Mixture of Major Kratom Alkaloids for Inhibition of CES1.

A screen against CES1 activity was performed using a mixture of select kratom alkaloids that approximated the relative systemic concentrations reported in a recent human pharmacokinetic (PK) study [46]. Using the available median determined after a 2g dose of kratom [40], a kratom alkaloid mixture dissolved in DMSO was made comprising of 15.8% mitragynine, 9.9% speciogynine, 59.4% speciociliatine, 11.78% paynantheine, and 3.1% 7-hydroxymitragynine. This concentration approximated the relative abundance of the alkaloids reflected in systemic concentrations. A final mixture concentration of 81.9 nM mitragynine, 51.4 nM speciogynine, 308 nM speciociliatine, 61.1 nM paynantheine, and 16.1 nM 7-hydroxymitragynine was achieved in the reaction mixture containing a final volume of 100 μL with 1% solvent as described previously. Keeping the proportions constant, the kratom alkaloid mixture was concentrated at 2.5 times, 4 times, 7.5 times, and 10 times the initial kratom alkaloid content (Supplemental Table 2). Negative controls contained only 1% DMSO and 10 μM of montelukast in DMSO served as a positive control. As described previously, all reactions proceeded through the incubation process, were terminated, and analyzed by LC-MS/MS evaluation.

LC-MS/MS Analysis.

All analysis was performed by a high-performance liquid chromatography system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) coupled to an AB Sciex API 3000 Triple-Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) equipped with a Heated-Source-Induced-Disassociation device (HSID, Ionics, Concord, ON, Canada) and equipped with Analyst 1.4.2 software. To achieve chromatographic separation, a C18 reverse-phase analytic column (Aqua, 50 × 2.0 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA) was used. A gradient mobile phase consisting of 0.1% formic acid in water (aqueous phase) and methanol (organic phase) at a flow rate of 0.25 mL/min was used as previously described [21,22]. The gradient method began by delivering 90% aqueous phase and 10% organic phase, which was held for 2 min. After 2 min there was a gradual delivery change to 10% aqueous phase and 90% organic phase for 4 min. At 6 min, the delivery reverted to 90% aqueous phase and 10% organic phase and was held for 5 min resulting in a run time of 11 min. All mass spectrometric analysis was performed in positive mode with electrospray ionization, and the mass transitions of the mass/charge ratios were for OC and ritalinic acid were respectively as follows: 285.3 → 138.3 and 220.2 → 84.1 (Supplemental Fig.1).

Data Analysis.

Each assay had control reaction solutions containing only OST and phosphate buffer solution to properly account for OST’s ability to form OC through spontaneous hydrolysis as reported previously [21,22]. All assay systems appropriately accounted for formation of spontaneous product by subtracting the average spontaneous formation of OC from each sample’s reported OC formation, allowing for determination of OC formed through CES1 catalyzed hydrolysis.

All experimental results represent the mean of triplicate samples (± S.D.), and a one-tailed t test was performed to determine statistical significance () when CES1 activity was reduced below the negative control (p < 0.05) unless otherwise stated.

A nonlinear regression analysis with the modified Hill equation (Eq.1) was performed to quantify the results for all conducted concentration response curves and time-dependent assays:

| [Eq.1] [21,22]. |

represents the ratio of metabolite formation of remaining enzyme activity in comparison to each groups’ respective controls containing only DMSO and is plotted as a ratio relative to a control containing DMSO only, represents the maximal inhibitory percentage, [] represents inhibitor concentration for kratom extract (μg/mL) or kratom alkaloid (μM), represents the half-maximal inhibitory concentration for kratom extract (μg/mL) or kratom alkaloid (μM), and b represents a shaping exponent. All parameters determined from Eq. 1 were used in Eq. 2 to determine the for kratom extract (μg/mL) or kratom alkaloid (μM), which represents the inhibitor concentration that achieves a reduction in 50% of enzyme activity:

| [Eq.2]. |

Another nonlinear regression analysis was conducted using a modified mixed competitive-noncompetitive inhibition Michaelis-Menten model designed to evaluate the reversible in vitro inhibition of CES1 by select kratom alkaloids is displayed by Eq.3:

| [Eq.3]. |

represents substrate concentration of OST (μM), represents the concentration of kratom alkaloid (μM), and represents OC formation velocity expressed as nmol/min/mg protein, as determined via LC-MS/MS analysis. Using Eq. 3 the following parameters were determined: (Michaelis-Menten constant (μM)), (maximum reaction velocity (nmol/min/mg protein), (inhibition constant (μM)), and (reversible inhibition type), where equal to 1 (noncompetitive inhibition), approaching infinity (competitive inhibition), and between 1 and infinity (mixed-type inhibition). All used definitions and interpretations of the enzyme kinetics and enzyme inhibition have largely been adapted from Segel [47] and previously employed to evaluate inhibitors of CES1 [21,22].

Software.

All data was stored and quantified using Excel version 16.66.1 for Mac (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). All data was processed via nonlinear regression analysis along with graph visualization through GraphPad Prism version 10.0.2 for macOS (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Screening of select kratom extracts and major kratom alkaloids.

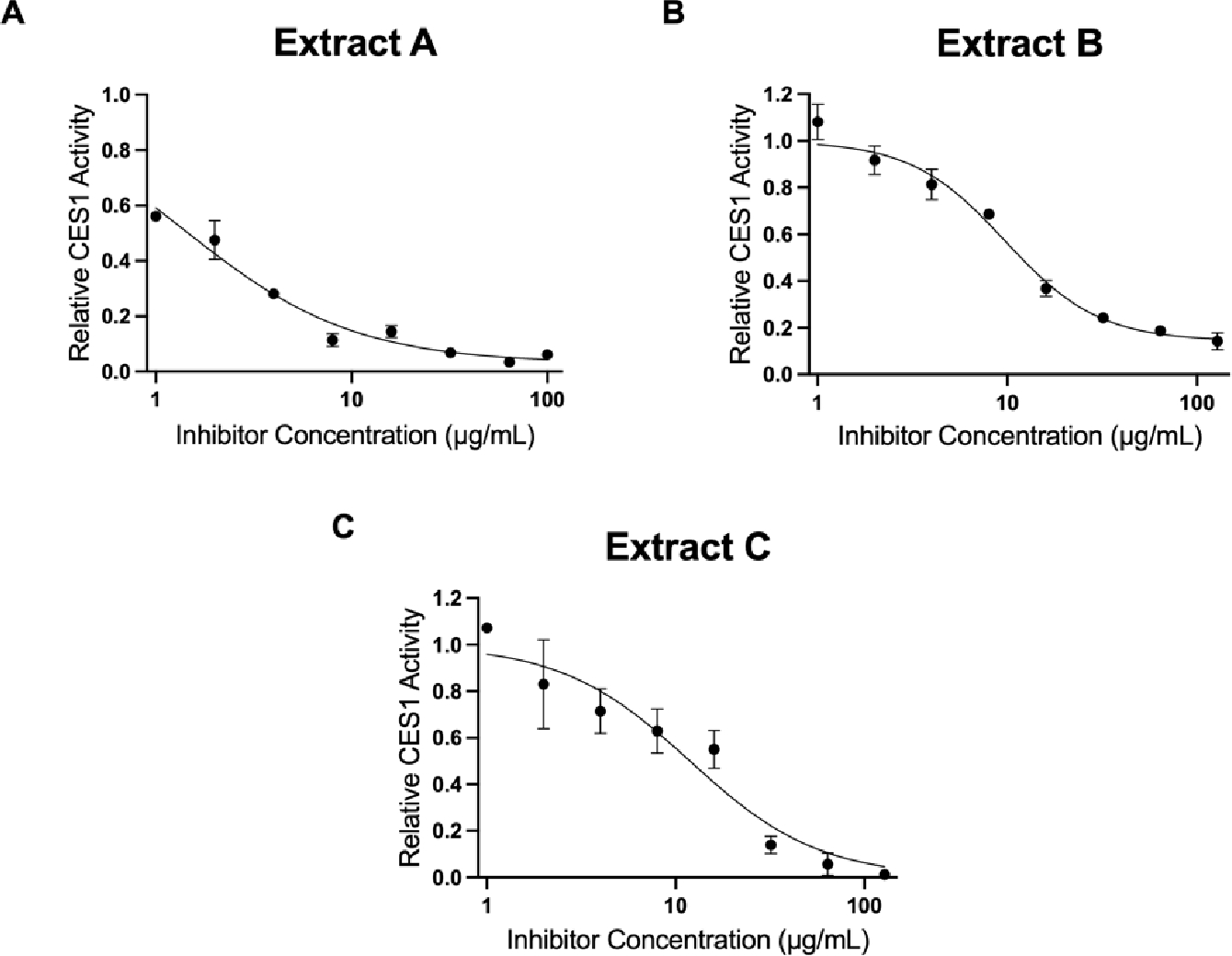

The initial screen of extracts and alkaloids demonstrated that at select concentrations most were capable of inhibiting CES1 by more than 50%, except for for extract D, 7-hydroxymitragynine and 16-COOH mitragynine which did not undergo further analysis (Supplemental Figure 2 and 3). For all kratom extracts and alkaloids that displayed >50% inhibition of CES1 activity, it was determined that further evaluation of the concentration response against CES1 activity was warranted. At increasing concentrations of extracts and individual alkaloids, an increased reduction in CES1 activity was observed (Fig.3, Fig.4). The respective for extract A, B, and C were as follows: 1.46, 11.8, and 11.9 μg/mL. The respective for the major alkaloids of mitragynine, speciociliatine, paynantheine, speciogynine, and corynantheidine were as follows: 38.9, 18.1, 32.9, 54.3 and 32.3 μM.

Figure 3. Concentration response curves for select kratom extracts: A) Extract A, B) Extract B, C) Extract C.

Extracts (0–128 μg/mL) were added to the incubation mixture containing 200 μM OST (substrate) and CES1 S9 containing 1% DMSO in the final incubation mixture. All extracts demonstrated concentration dependent inhibition of CES1. The respective for extract A, B, and C were as follows: 1.46, 11.8, and 11.9 μg/mL.

Figure 4. Concentration response curves for select kratom alkaloids: A) mitragynine, B) speciociliatine, C) paynantheine, D) speciogynine, E) corynantheidine.

Individual alkaloid (0–128 μM) was added to the incubation mixture containing 200 μM OST (substrate) and CES1 S9 containing 1% DMSO in the final incubation mixture. All alkaloids demonstrated concentration dependent inhibition of CES1. The respective for the major alkaloids of mitragynine, speciociliatine, paynantheine, speciogynine, and corynantheidine were as follows: 38.9, 18.1, 32.9, 54.3 and 32.3 μM.

Select Kratom Extracts and Alkaloids Demonstrate Reversible Inhibition of CES1 OST hydrolysis.

A direct comparison between the determined for both groups allowed for determination of type of inhibition. All assessed kratom extracts and major alkaloids had ratios greater than 0.5, indicating the introduction of a 30 min preincubation phase demonstrated no marked increase of inhibition potency and it was determined that there was no display of any time dependent inhibition, or irreversible inhibition (Supplemental Fig.4 and 5, Table 1 and 2). Due to the absence of irreversible inhibition, the four alkaloids that displayed values less than 50 μM (mitragynine, speciociliatine, paynantheine, and corynantheidine) were further evaluated as reversible inhibitors of CES1 activity.

TABLE 1.

Preincubation effect with each select kratom extract on CES1 activity

| Select kratom extracts | Group | (pg/mL) | Fit (r2) | Statistical comparison (p value) | Ratio of Preincubation to No Preincubation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extract A | Preincubation | 1.16 ± 0.126 | 0.984 | 0.458 | 0.796 |

| No preincubation | 1.46 ± 0.187 | 0.956 | |||

| Extract B | Preincubation | 32.5 ± 3.96 | 0.879 | 0.0344 | 2.75 |

| No Preincubation | 11.8 ± 1.02 | 0.973 | |||

| Extract C | Preincubation | 30.8 ± 3.14 | 0.960 | 0.00260 | 2.58 |

| No preincubation | 11.9 ± 2.70 | 0.922 |

TABLE 2.

Preincubation effect with each select kratom alkaloid on CES1 activity

| Kratom alkaloids | Group | (μM) | Fit (r2) | Statistical compariso n (p value) | Ratio of Preincubation to No Preincubation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitragynine | Preincubation | 33.8 ± 5.47 | 0.882 | 0.976 | 0.868 |

| No preincubation | 38.9 ± 16.30 | 0.762 | |||

| Speciociliatine | Preincubation | 21.4 ± 2.48 | 0.975 | 0.143 | 1.18 |

| No Preincubation | 18.1 ± 4.00 | 0.941 | |||

| Paynantheine | Preincubation | 45.6 ± 14.1 | 0.915 | 0.381 | 1.38 |

| No preincubation | 32.9 ± 7.20 | 0.829 | |||

| Speciogynine | Preincubation | 66.2 ± 29.0 | 0.868 | 0.147 | 1.22 |

| No preincubation | '54.3 ± 15.5 | 0.807 | |||

| Corynantheidine | Preincubation | 32.0 ± 5.37 | 0.920 | 0.237 | 0.993 |

| No preincubation | 32.3 ± 3.64 | 0.975 |

In Vitro Characterization and Quantification of Reversible Inhibition Potential of our Kratom Alkaloids.

Using nonlinear regression analysis from the modified Michaelis Menten model of [Eq.3], both the extent and type of inhibition each of the investigated kratom alkaloids exhibited with CES1 was determined (Fig.5). Each data point represents samples done in duplicate (±S.D.) with each alkaloid Michaelis Menten plot run in triplicate. The values for mitragynine, speciociliatine, paynantheine, and corynantheidine were 20.6, 8.6, 26.1, and 12.5 μM respectively (Table 3). The order of the inhibition potency in vitro for each kratom alkaloid is as follows: speciociliatine > corynantheidine > mitragynine > paynantheine. Speciociliatine, paynantheine and corynantheidine demonstrated a mixed competitive-noncompetitive inhibition of CES1 activity, while mitragynine that displayed a pure competitive inhibition of CES1 activity (Table 3).

Figure 5. The kinetic analysis for each kratom alkaloid A) mitragynine, B) speciociliatine, C) paynantheine, D) corynantheidine in a CES1 in vitro system.

Varying concentrations of kratom alkaloid (μM) and OST (μM) were incubated with CES1 S9. Each graph represents 1 of the 3 curves generated curves. Velocity of the reaction (nmol/min/mg protein) represents the marker used to determine CES1 activity.

TABLE 3.

Parameter estimates of in vitro kratom alkaloid inhibition studies on CES1 activity

| Kratom Alkaloids | (μM) | (μM) | (nmol/min/mg protein) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitragynine | 2702 ± 601.7 | 20.62 ± 5.471 | ∞ | 224.2 ± 24.37 |

| Speciociliatine | 1869 ± 400.1 | 8.580 ± 3.093 | 2.817 ± 1.666 | 210.5 ± 41.43 |

| Paynantheine | 2555 ± 835.3 | 26.08 ± 7.337 | 8.439 ± 6.336 | 232.2 ± 18.38 |

| Corynantheidine | 1997 ± 639.8 | 12.49 ± 5.621 | 8.767 ± 2.734 | 232.2 ± 37.80 |

Utilizing nonlinear regression analysis by the modified Michaelis-Menten equation in [Eq.3], all relevant parameter estimates were obtained. Each value represents the mean estimated parameter and S.D. with triplicate experiments.

A Physiological Concentration Screen of Select Kratom Alkaloids Displays Only Minor Inhibition of CES1.

Using a reported median value after a 2g (low dose) of kratom to approximate a physiological achievable mixture to examine in vitro [46] (Supplemental Table 2), CES1 activity was only reduced by 3% (not statistically significant) relative to a negative control (Fig.6). When keeping the proportions similar but increasing the overall concentration 2.5 and 4-fold we observed an 11% reduction in CES1 activity that was statistically significant and when increasing to 7.5 and 10-fold we observed 22% and 27% reduction in CES1 activity respectively (p-value < 0.05) (Fig.6).

Figure 6. Physiologically based kratom alkaloid screen against CES1 activity.

Each bar represents the remaining CES1 activity relative to a negative control with no inhibitor (Dashed line N.C.). The positive control (Dashed line P.C.) was 10 μM of montelukast dissolved in DMSO. A mixture of select kratom alkaloids were dissolved in DMSO and were screened at varying concentrations. (*) indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05) when CES1 activity was reduced below control.

Discussion

Select kratom extracts and major indole alkaloids displayed varying degrees of CES1 inhibition in vitro. Extracts A, B, and C demonstrated a concentration dependent inhibition of CES1 activity. It can be appreciated that extract A, which displayed the most potent inhibition of CES1 activity also contained more mitragynine, paynantheine, speciociliatine, speciogynine, and corynantheidine content relative to the other extracts (Supplemental Table 1). Most major kratom alkaloids, such as mitragynine, also displayed a concentration dependent inhibition of CES1 activity. Kratom extracts A, B, and C and individual kratom alkaloids did not demonstrate any irreversible inhibition of CES1, as an introduction of a 30 min preincubation period with the extracts or alkaloids and enzyme did not demonstrate a marked increase in inhibition potency. The order of reversible CES1 inhibition potency for the individual kratom alkaloids were as follows: speciociliatine > corynantheidine > mitragynine > paynantheine, as determined by the modified Michaelis-Menten model. The type of inhibition of each of the alkaloids was determined from that same model which demonstrated speciociliatine, paynantheine and corynantheidine as mixed competitive-noncompetitive inhibitors of CES1 activity, and mitragynine as a purely competitive inhibitor of CES1 activity. Finally, using a mixture of kratom alkaloids approximating the relative abundance of each in systemic concentrations from a clinical study, each mixture had minimal impacts on CES1 activity with a 10-fold concentration at most having only mild inhibitory effects on CES1 activity.

While kratom use by the public has expanded dramatically and there is keen research interest in its potential clinical utility, there are still very few human studies that characterize the PK of the major kratom alkaloids after a dose of standardized kratom [38,46,48]. While these studies are largely in agreement with each other, there are limitations regarding the potential impact chronic usage as well as the impact of extreme daily doses. Especially since kratom users in the U.S. have reported taking significantly higher amounts per dose (i.e. >8g) and more than 6 doses per day [7]. A case series involving 28 patients with kratom use disorder reported the highest reported dose being 850g a day [49]. Outside of toxicology reports, there is a paucity of PK data for kratom at exposures over 2g a dose [50]. At a 2g dose, the highest measured was speciociliatine at 0.308 μM, while all other alkaloids did not achieve a higher than 0.100 μM [46]. If taking a 20g dose (10-fold higher than the customary low dose), alkaloid exposures of a 10-fold increase might be expected, but even if that held true, the highest achieved would be speciociliatine at 3.08 μM and all other alkaloids having of less than 1 μM. Comparing that with the Ki values obtained in Table 3, speciociliatine had the most potent at 8.6 μM, which is over 2-fold the anticipated of a 20g dose. Achieving this level of exposure may not inhibit enough CES1 to have a meaningful clinical effect, as the 10-fold mixture in the physiologically based screen only impaired CES1 function by 27% (Fig.6). Although no data was available for corynantheine and speciogynine did not meet criteria for further evaluation, similar profiles to the other three evaluated kratom alkaloids with PK data are anticipated.

As determined by this evaluation, a typical 2g low dose of kratom consumed as a tea is not anticipated to precipitate a DDI with any CES1 substrate medications. Indeed, there could be some pause for concern for DDIs at higher doses of kratom and for chronic users of kratom, but without proper PK data it is challenging to anticipate plasma concentrations of alkaloids at extreme and prolonged exposures of kratom. Based on the predicted data for kratom alkaloids at higher doses ranging from 5 to 20g, a clinically relevant DDI through CES1 is not anticipated like the lower 2g dose.

There are several limitations with the evaluation of the commercially available kratom extracts. First, while kratom is a complex mixture, alkaloid content is only 2%, which does not exclude the possibility of other contents within the extracts inhibiting CES1. Second, despite dissolving the extract powder in ethanol initially and redissolving in DMSO, there is a possibility of invisible aggregates due to insolubilities that could interfere with enzyme analysis of the extract. Finally, there is no consensus method for preparing kratom extracts making it difficult to compare these specific formulations to other assessments. Other limitations exist with this work that are typical for in vitro botanical studies [51]. One such limitation is the evaluation of the bioavailability of the individual kratom alkaloids. All available PK data in humans involves dosing with an extract containing all alkaloids and not the pure kratom alkaloids alone. Other limitations that exist for this evaluation are variability in extract composition and possible concerns over product adulteration [42,52,53]. Lastly, the formation of metabolites of kratom and their potential influence on CES1 was not evaluated in this study [39,54–56].

In summary, kratom and its major alkaloids display an in vitro concentration dependent inhibition of CES1. Further, with available PK data and these experimentally determined data, a typical low dose (2g) of kratom as a tea would have no anticipated DDI with CES1 substrate medications.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Kratom extracts and its major alkaloids demonstrate a reversible inhibition of carboxylesterase 1, in vitro.

Using kratom products and medications metabolized by carboxylesterase 1 are unlikely to precipitate drug-drug interactions.

To exclude drug interaction risk, clinical pharmacokinetic studies with kratom at higher and chronic usage are warranted.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD093612) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (UG3DA048353 and R01DA047855). We would like to acknowledge Abhisheak Sharma MPharm, PhD for providing technical input related to kratom extracts and alkaloids used in this investigation.-We would like to acknowledge student interns Anna Waizenegger and Cosima Erhard for their contributions to the project. Figure 2 was partly created by use of Servier Medical Art templates, provided by Servier, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unimported License; https://smart.servier.com.

Nonstandard abbreviations:

reversible inhibition type indicator

- b

shaping exponent utilized in Modified Hill equation

- CES1

carboxylesterase 1

maximum plasma concentration

- DDI

drug-drug interaction

- DME

drug-metabolizing enzymes

- IC

half-maximal inhibitory concentration

concentration at which an inhibitor can achieve 50% of enzyme activity

maximal percentage of inhibition

inhibition constant

Michaelis-Menten constant

- OC

oseltamivir carboxylate

- OST

oseltamivir phosphate

- PBS

Phosphate buffered saline

the ratio of metabolite formation with inhibitor to control without inhibitor as determined by the Modified Hill equation

maximum velocity of a reaction

Footnotes

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Suwanlert S, A study of kratom eaters in Thailand, United Nations : Office on Drugs and Crime. (1975). //www.unodc.org/unodc/en/data-and-analysis/bulletin/bulletin_1975-01-01_3_page003.html (accessed January 26, 2023). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Grewal KS, The Effect of Mitragynine on Man, British Journal of Medical Psychology. 12 (1932) 41–58. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1932.tb01062.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Grewal KS, Observations on the pharmacology of mitragynine, Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. (1932) 251–271. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Assanangkornchai S, Muekthong A, Sam-angsri N, Pattanasattayawong U, The Use of Mitragynine speciosa (“Krathom”), an Addictive Plant, in Thailand, Substance Use & Misuse. 42 (2007) 2145–2157. 10.1080/10826080701205869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Vicknasingam B, Narayanan S, Beng GT, Mansor SM, The informal use of ketum (Mitragyna speciosa) for opioid withdrawal in the northern states of peninsular Malaysia and implications for drug substitution therapy, International Journal of Drug Policy. 21 (2010) 283–288. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Schimmel J, Amioka E, Rockhill K, Haynes CM, Black JC, Dart RC, Iwanicki JL, Prevalence and description of kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) use in the United States: a cross-sectional study, Addiction. 116 (2021) 176–181. 10.1111/add.15082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Grundmann O, Patterns of Kratom use and health impact in the US—Results from an online survey, Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 176 (2017) 63–70. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Prozialeck WC, Jivan JK, Andurkar SV, Pharmacology of Kratom: An Emerging Botanical Agent With Stimulant, Analgesic and Opioid-Like Effects, Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 112 (2012) 792–799. 10.7556/jaoa.2012.112.12.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Eastlack SC, Cornett EM, Kaye AD, Kratom-Pharmacology, Clinical Implications, and Outlook: A Comprehensive Review, Pain Ther. 9 (2020) 55–69. 10.1007/s40122-020-00151-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Matsumoto K, Mizowaki M, Suchitra T, Murakami Y, Takayama H, Sakai S, Aimi N, Watanabe H, Central antinociceptive effects of mitragynine in mice: contribution of descending noradrenergic and serotonergic systems, European Journal of Pharmacology. 317 (1996) 75–81. 10.1016/S0014-2999(96)00714-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Matsumoto K, Hatori Y, Murayama T, Tashima K, Wongseripipatana S, Misawa K, Kitajima M, Takayama H, Horie S, Involvement of μ-opioid receptors in antinociception and inhibition of gastrointestinal transit induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, isolated from Thai herbal medicine Mitragyna speciosa, European Journal of Pharmacology. 549 (2006) 63–70. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Matsumoto K, Horie S, Ishikawa H, Takayama H, Aimi N, Ponglux D, Watanabe K, Antinociceptive effect of 7-hydroxymitragynine in mice: Discovery of an orally active opioid analgesic from the Thai medicinal herb Mitragyna speciosa, Life Sciences. 74 (2004) 2143–2155. 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Matsumoto K, Horie S, Takayama H, Ishikawa H, Aimi N, Ponglux D, Murayama T, Watanabe K, Antinociception, tolerance and withdrawal symptoms induced by 7-hydroxymitragynine, an alkaloid from the Thai medicinal herb Mitragyna speciosa, Life Sciences. 78 (2005) 2–7. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Thongpradichote S, Matsumoto K, Tohda M, Takayama H, Aimi N, Sakai S, Watanabe H, Identification of opioid receptor subtypes in antinociceptive actions of supraspinally-admintstered mitragynine in mice, Life Sciences. 62 (1998) 1371–1378. 10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Horie S, Koyama F, Takayama H, Ishikawa H, Aimi N, Ponglux D, Matsumoto K, Murayama T, Indole Alkaloids of a Thai Medicinal Herb, Mitragyna speciosa, that has Opioid Agonistic Effect in Guinea-Pig Ileum, Planta Med. 71 (2005) 231–236. 10.1055/s-2005-837822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Váradi A, Marrone GF, Palmer TC, Narayan A, Szabó MR, Le Rouzic V, Grinnell SG, Subrath JJ, Warner E, Kalra S, Hunkele A, Pagirsky J, Eans SO, Medina JM, Xu J, Pan Y-X, Borics A, Pasternak GW, McLaughlin JP, Majumdar S, Mitragynine/Corynantheidine Pseudoindoxyls As Opioid Analgesics with Mu Agonism and Delta Antagonism, Which Do Not Recruit β-Arrestin-2, J Med Chem. 59 (2016) 8381–8397. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Wang D, Zou L, Jin Q, Hou J, Ge G, Yang L, Human carboxylesterases: a comprehensive review, Acta Pharm Sin B. 8 (2018) 699–712. 10.1016/j.apsb.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].He B, Shi J, Wang X, Jiang H, Zhu H-J, Label-Free Absolute Protein Quantification with Data-Independent Acquisition, J Proteomics. 200 (2019) 51–59. 10.1016/j.jprot.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Basit A, Neradugomma NK, Wolford C, Fan PW, Murray B, Takahashi RH, Khojasteh SC, Smith BJ, Heyward S, Totah RA, Kelly EJ, Prasad B, Characterization of Differential Tissue Abundance of Major Non-CYP Enzymes in Human, Mol. Pharmaceutics. 17 (2020) 4114–4124. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.0c00559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xu J, Qiu J-C, Ji X, Guo H-L, Wang X, Zhang B, Wang T, Chen F, Potential Pharmacokinetic Herb-Drug Interactions: Have we Overlooked the Importance of Human Carboxylesterases 1 and 2?, Curr Drug Metab. 20 (2019) 130–137. 10.2174/1389200219666180330124050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Qian Y, Wang X, Markowitz JS, In Vitro Inhibition of Carboxylesterase 1 by Major Cannabinoids and Selected Metabolites, Drug Metab Dispos. 47 (2019) 465–472. 10.1124/dmd.118.086074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Melchert PW, Qian Y, Zhang Q, Klee BO, Xing C, Markowitz JS, In vitro inhibition of carboxylesterase 1 by Kava (Piper methysticum) Kavalactones, Chem Biol Interact. 357 (2022) 109883. 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.109883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Markowitz JS, Faria LD, Zhang Q, Melchert PW, Frye RF, Klee BO, Qian Y, The Influence of Cannabidiol on the Pharmacokinetics of Methylphenidate in Healthy Subjects, MCA. 5 (2022) 199–206. 10.1159/000527189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhu H-J, Patrick KS, Yuan H-J, Wang J-S, Donovan JL, DeVane CL, Malcolm R, Johnson JA, Youngblood GL, Sweet DH, Langaee TY, Markowitz JS, Two CES1 gene mutations lead to dysfunctional carboxylesterase 1 activity in man: clinical significance and molecular basis, Am J Hum Genet. 82 (2008) 1241–1248. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Lewis JP, Horenstein RB, Ryan K, O’Connell JR, Gibson Q, Mitchell BD, Tanner K, Chai S, Bliden KP, Tantry US, Peer CJ, Figg WD, Spencer SD, Pacanowski MA, Gurbel PA, Shuldiner AR, The functional G143E variant of carboxylesterase 1 is associated with increased clopidogrel active metabolite levels and greater clopidogrel response, Pharmacogenet Genomics. 23 (2013) 1–8. 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32835aa8a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhang Q, Melchert PW, Markowitz JS, In vitro evaluation of the impact of Covid-19 therapeutic agents on the hydrolysis of the antiviral prodrug remdesivir, Chem Biol Interact. 365 (2022) 110097. 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.110097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Zhu H-J, Markowitz JS, Activation of the Antiviral Prodrug Oseltamivir Is Impaired by Two Newly Identified Carboxylesterase 1 Variants, Drug Metab Dispos. 37 (2009) 264–267. 10.1124/dmd.108.024943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Tarkiainen EK, Backman JT, Neuvonen M, Neuvonen PJ, Schwab M, Niemi M, Carboxylesterase 1 Polymorphism Impairs Oseltamivir Bioactivation in Humans, Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 92 (2012) 68–71. 10.1038/clpt.2012.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stage C, Jürgens G, Guski LS, Thomsen R, Bjerre D, Ferrero-Miliani L, Lyauk YK, Rasmussen HB, Dalhoff K, The impact of CES1 genotypes on the pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate in healthy Danish subjects, Br J Clin Pharmacol. 83 (2017) 1506–1514. 10.1111/bcp.13237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Stage C, Dalhoff K, Rasmussen HB, Schow Guski L, Thomsen R, Bjerre D, Ferrero-Miliani L, Busk Madsen M, Jürgens G, The impact of human CES1 genetic variation on enzyme activity assessed by ritalinic acid/methylphenidate ratios, Basic & Clinical Pharmacology & Toxicology. 125 (2019) 54–61. 10.1111/bcpt.13212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shi J, Wang X, Nguyen J-H, Bleske BE, Liang Y, Liu L, Zhu H-J, Dabigatran etexilate activation is affected by the CES1 genetic polymorphism G143E (rs71647871) and gender, Biochemical Pharmacology. 119 (2016) 76–84. 10.1016/j.bcp.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kong WM, Chik Z, Ramachandra M, Subramaniam U, Aziddin RER, Mohamed Z, Evaluation of the effects of Mitragyna speciosa alkaloid extract on cytochrome P450 enzymes using a high throughput assay, Molecules. 16 (2011) 7344–7356. 10.3390/molecules16097344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Hanapi NA, Ismail S, Mansor SM, Inhibitory effect of mitragynine on human cytochrome P450 enzyme activities, Pharmacognosy Res. 5 (2013) 241–246. 10.4103/0974-8490.118806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kamble SH, Sharma A, King TI, Berthold EC, León F, Meyer PKL, Kanumuri SRR, McMahon LR, McCurdy CR, Avery BA, Exploration of cytochrome P450 inhibition mediated drug-drug interaction potential of kratom alkaloids, Toxicol Lett. 319 (2020) 148–154. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2019.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Tanna RS, Tian D-D, Cech NB, Oberlies NH, Rettie AE, Thummel KE, Paine MF, Refined Prediction of Pharmacokinetic Kratom-Drug Interactions: Time-Dependent Inhibition Considerations, J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 376 (2021) 64–73. 10.1124/jpet.120.000270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Lim EL, Seah TC, Koe XF, Wahab HA, Adenan MI, Jamil MFA, Majid MIA, Tan ML, In vitro evaluation of cytochrome P450 induction and the inhibition potential of mitragynine, a stimulant alkaloid, Toxicology in Vitro. 27 (2013) 812–824. 10.1016/j.tiv.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Abdullah NH, Ismail S, Inhibition of UGT2B7 Enzyme Activity in Human and Rat Liver Microsomes by Herbal Constituents, Molecules. 23 (2018) 2696. 10.3390/molecules23102696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Tanna RS, Nguyen JT, Hadi DL, Layton ME, White JR, Cech NB, Oberlies NH, Rettie AE, Thummel KE, Paine MF, Clinical Assessment of the Drug Interaction Potential of the Psychotropic Natural Product Kratom, Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. n/a (n.d.). 10.1002/cpt.2891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Meyer MR, Schütz A, Maurer HH, Contribution of human esterases to the metabolism of selected drugs of abuse, Toxicol Lett. 232 (2015) 159–166. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2014.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Srichana K, Janchawee B, Prutipanlai S, Raungrut P, Keawpradub N, Effects of Mitragynine and a Crude Alkaloid Extract Derived from Mitragyna speciosa Korth. on Permethrin Elimination in Rats, Pharmaceutics. 7 (2015) 10–26. 10.3390/pharmaceutics7020010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].León F, Habib E, Adkins JE, Furr EB, McCurdy CR, Cutler SJ, Phytochemical Characterization of the Leaves of Mitragyna Speciosa Grown in USA, Natural Product Communications. 4 (2009) 1934578X0900400705. 10.1177/1934578X0900400705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Sharma A, Kamble SH, León F, Chear NJ-Y, King TI, Berthold EC, Ramanathan S, McCurdy CR, Avery BA, Simultaneous quantification of ten key Kratom alkaloids in Mitragyna speciosa leaf extracts and commercial products by ultra-performance liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry, Drug Test Anal. 11 (2019) 1162–1171. 10.1002/dta.2604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Liu R, Tam TW, Mao J, Saleem A, Krantis A, Arnason JT, Foster BC, The Effect of Natural Health Products and Traditional Medicines on the Activity of Human Hepatic Microsomal-Mediated Metabolism of Oseltamivir, Journal of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences. 13 (2010) 43–55. 10.18433/J3ZP42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhu H-J, Markowitz JS, Activation of the Antiviral Prodrug Oseltamivir Is Impaired by Two Newly Identified Carboxylesterase 1 Variants, Drug Metab Dispos. 37 (2009) 264–267. 10.1124/dmd.108.024943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Parker RB, Hu Z-Y, Meibohm B, Laizure SC, Effects of alcohol on human carboxylesterase drug metabolism, Clin Pharmacokinet. 54 (2015) 627–638. 10.1007/s40262-014-0226-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Tanna RS, Nguyen JT, Hadi DL, Manwill PK, Flores-Bocanegra L, Layton ME, White JR, Cech NB, Oberlies NH, Rettie AE, Thummel KE, Paine MF, Clinical Pharmacokinetic Assessment of Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa), a Botanical Product with Opioid-like Effects, in Healthy Adult Participants, Pharmaceutics. 14 (2022) 620. 10.3390/pharmaceutics14030620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Segel IH, Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-State Enzyme Systems, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Trakulsrichai S, Sathirakul K, Auparakkitanon S, Krongvorakul J, Sueajai J, Noumjad N, Sukasem C, Wananukul W, Pharmacokinetics of mitragynine in man, Drug Des Devel Ther. 9 (2015) 2421–2429. 10.2147/DDDT.S79658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Broyan VR, Brar JK, Allgaier Tristen S, Allgaier JT, Long-term buprenorphine treatment for kratom use disorder: A case series, Substance Abuse. 43 (2022) 763–766. 10.1080/08897077.2021.2010250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Schmitt J, Bingham K, Knight LD, Kratom-Associated Fatalities in Northern Nevada—What Mitragynine Level Is Fatal?, The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 42 (2021) 341. 10.1097/PAF.0000000000000695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Markowitz JS, Zhu H-J, Limitations of in vitro assessments of the drug interaction potential of botanical supplements, Planta Med. 78 (2012) 1421–1427. 10.1055/s-0032-1315025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Nacca N, Schult RF, Li L, Spink DC, Ginsberg G, Navarette K, Marraffa J, Kratom Adulterated with Phenylethylamine and Associated Intracerebral Hemorrhage: Linking Toxicologists and Public Health Officials to Identify Dangerous Adulterants, J Med Toxicol. 16 (2020) 71–74. 10.1007/s13181-019-00741-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Lydecker AG, Sharma A, McCurdy CR, Avery BA, Babu KM, Boyer EW, Suspected Adulteration of Commercial Kratom Products with 7-Hydroxymitragynine, J Med Toxicol. 12 (2016) 341–349. 10.1007/s13181-016-0588-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Basiliere S, Kerrigan S, CYP450-Mediated Metabolism of Mitragynine and Investigation of Metabolites in Human Urine, Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 44 (2020) 301–313. 10.1093/jat/bkz108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Kruegel AC, Uprety R, Grinnell SG, Langreck C, Pekarskaya EA, Le Rouzic V, Ansonoff M, Gassaway MM, Pintar JE, Pasternak GW, Javitch JA, Majumdar S, Sames D, 7-Hydroxymitragynine Is an Active Metabolite of Mitragynine and a Key Mediator of Its Analgesic Effects, ACS Cent Sci. 5 (2019) 992–1001. 10.1021/acscentsci.9b00141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Kamble SH, Sharma A, King TI, León F, McCurdy CR, Avery BA, Metabolite profiling and identification of enzymes responsible for the metabolism of mitragynine, the major alkaloid of Mitragyna speciosa (kratom), Xenobiotica. 49 (2019) 1279–1288. 10.1080/00498254.2018.1552819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.