Abstract

The analysis of circulating tumor cells and tumor-derived materials, such as circulating tumor DNA, circulating miRNAs (cfmiRNAs), and extracellular vehicles provides crucial information in cancer research. CfmiRNAs, a group of short noncoding regulatory RNAs, have gained attention as diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. This review focuses on the discovery phases of cfmiRNA studies in breast cancer patients, aiming to identify altered cfmiRNA levels compared to healthy controls. A systematic literature search was conducted, resulting in 16 eligible publications. The studies included a total of 585 breast cancer cases and 496 healthy controls, with diverse sample types and different cfmiRNA assay panels. Several cfmiRNAs, including MIR16, MIR191, MIR484, MIR106a, and MIR193b, showed differential expressions between breast cancer cases and healthy controls. However, the studies had a high risk of bias and lacked standardized protocols. The findings highlight the need for robust study designs, standardized procedures, and larger sample sizes in discovery phase studies. Furthermore, the identified cfmiRNAs can serve as potential candidates for further validation studies in different populations. Improving the design and implementation of cfmiRNA research in liquid biopsies may enhance their clinical diagnostic utility in breast cancer patients.

Keywords: breast cancer, microRNA, miRNA, serum, plasma, high throughput techniques

1. Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) constitute a class of small RNA molecules that are naturally present and have been conserved over evolutionary history [1]. These single-stranded RNA molecules do not participate in the encoding of proteins and typically consist of 19 to 25 nucleotides [1]. A collection of around 2650 distinct mature microRNA sequences is documented in miRNA libraries [1]. Functionally, miRNAs play a critical role as post-transcriptional regulators, influencing gene expression across various tissues and developmental stages. They accomplish this by engaging in precise interactions within intricate regulatory networks [2].

Due to their limited binding region between miRNA and mRNA, a single miRNA has the capacity to target multiple specific mRNAs, thereby exerting influence across diverse pathways [2]. Given their diverse functions, miRNAs possess the ability to regulate various pathways associated with cellular activities and intercellular communication. These pathways encompass processes such as cellular growth, specialization, replication, and programmed cell death [3].

Approximately half of the genetic codes responsible for miRNAs in humans are situated within regions of the genome that are linked to cancer or at chromosomal sites prone to fragility and instability [4].

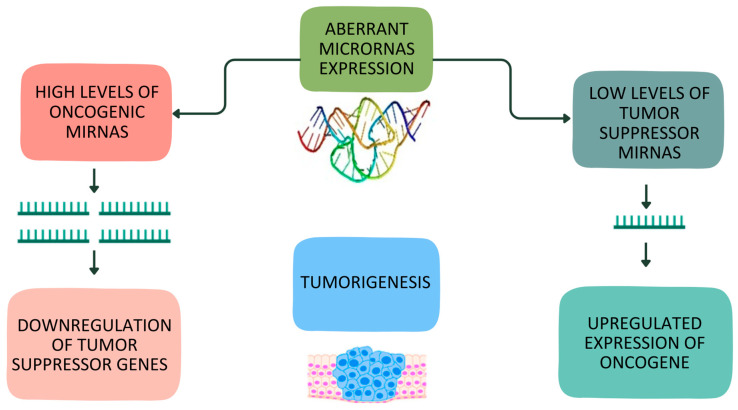

In breast cancer, as in numerous other cancer types, the onset of abnormal cell behavior leads to uncontrolled proliferation. This proliferation is driven by genetic modifications that influence cellular growth regulatory mechanisms. The miRNAs associated with this disease can be classified into two categories: oncogenic miRNAs (known as oncomiRs) and tumor suppressor miRNAs (referred to as tsmiRs) [1]. OncomiRs are generally upregulated in breast cancer and function by suppressing the expression of potential tumor-suppressing genes [5]. Conversely, tsmiRs hinder the expression of oncogenes that contribute to the formation of breast tumors [5]. Consequently, decreased expression of tsmiRs can lead to the initiation of breast malignancy [5]. Figure 1 offers an overview of the specific regulatory roles of miRNAs in breast cancer.

Figure 1.

Overview of regulatory role of oncogenic and tumor suppressor miRNAs in breast cancer.

These regulatory networks encompass several fundamental aspects of cancer biology, including the maintenance of growth signals that promote proliferation, the achievement of replicative immortality, the initiation of invasion and metastasis, the resistance to programmed cell death and apoptotic responses, the stimulation of new blood vessel formation (angiogenesis), the activation of cellular metabolism and energy processes, and the facilitation of immune evasion by cancer cells [5]

Liquid biopsy provides important information on the analysis of circulating tumor cells and circulating tumor-derived materials, such as circulating tumor DNA, circulating miRNAs (cfmiRNAs), and extracellular vesicles [6].

In particular, cfmiRNAs have been extensively investigated as diagnostic biomarkers, other than as biomarkers for prognosis and therapy response. CfmiRNAs constitute a group of short, noncoding regulatory RNAs that modulate gene expression at the post transcriptional level [7]. Cell-free circulating microRNAs likely released from cells in lipid vesicles, microvesicles, or exosomes have been detected in peripheral blood circulation [8].

Usually, the study design of research works on biomarkers consists of a first phase generally regarded as a discovery phase, followed by a validation phase [9].

The discovery phase typically involves exploration carried out with high-throughput laboratory techniques to select a pool of candidates [10]. The objective is to identify a short list of promising cfmiRNAs associated with disease for further investigation. The discovery research poses considerable challenges, due to the large number of biomarkers being investigated, the typical weakness of signals from individual markers, and the frequent presence of strong noise due to experimental effects [10]. The validation study is a key step for translating laboratory findings into clinical practice; furthermore, this is heavily conditioned by the short list of biomarkers selected in the discovery phase [10].

While evolving molecular technologies in discovery studies have generated plenty of omics data, identification success has been very limited considering the reduced number of cfmiRNAs that have reached clinical use [11].

One of the reasons behind this phenomenon is the lack of adequate study designs in the discovery phase research [12]. Furthermore, several studies analyze candidate cfmiRNAs selected from a search on previous literature, thereby amplifying the problems that may have arisen due to a suboptimal discovery phase.

The search for cfmiRNAs to use as diagnostic biomarkers in breast cancer is very active. Several reviews and meta-analyses have been published on the predictive role of cfmiRNAs in breast cancer diagnosis [13,14,15,16,17]. Nevertheless, all of them were based on validation phases of the study or on studies on candidate cfmiRNAs.

This review aims to identify the altered levels of circulating microRNA in breast cancer patients compared to healthy controls, including only the discovery phases of the study. This can be of great usefulness for the progression of this research field, allowing the selection of candidate cfmiRNAs to be investigated in new case–control studies.

2. Materials and Methods

We have registered the protocol of this review in the international database of prospective registered systematic reviews (PROSPERO 2022; CRD42023399977). The workflow and methodology were based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analyses of Diagnostic Test Accuracy (PRISMA-DTA) guidelines [18].

2.1. Publication Search

We capitalized on a previous literature review conducted by our group, in which we conducted searches on PubMed, Cochrane Library, EMBASE, Google Scholar, and NCBI PubMed Central to select appropriate studies [13] (the previous review was updated to 31 December 2022).

The search was performed using the following keywords as a search strategy: ((Circulating) AND (microRNA OR miRNA) AND (breast AND Cancer)) NOT (cells) NOT (tissue) AND ((English [Filter]) AND (Humans [Filter]) AND (“31 December 2022” [Date—Release])). Additionally, other studies were identified through the references in previously selected publications.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In the systematic review, we considered all studies that fulfilled the following requirements: (1) inclusion of both patients with BC and healthy controls; (2) measurement of cfmiRNA levels in serum, plasma, or blood; and (3) presence of a discovery phase that used high throughput techniques, including studies with an agnostic genome-wide design.

Studies were excluded if they were candidate cfmiRNA studies, reviews, meta-analyses, letters, commentaries, or conference abstracts or if they were duplications of previous publications or written in languages other than English.

2.3. Data Extraction

Adhering to the inclusion criteria, the primary authors (L.P. and C.S.) independently gathered the relevant data. In the event of any disagreements, consensus was reached through discussion. The extracted data included first author’s name and reference, country, sample size, biological sample type (plasma, serum, or blood), cfmiRNAs, AUC value (95% CI), fold change (95% CI), and expression (upregulation or downregulation).

2.4. Quality Assessment

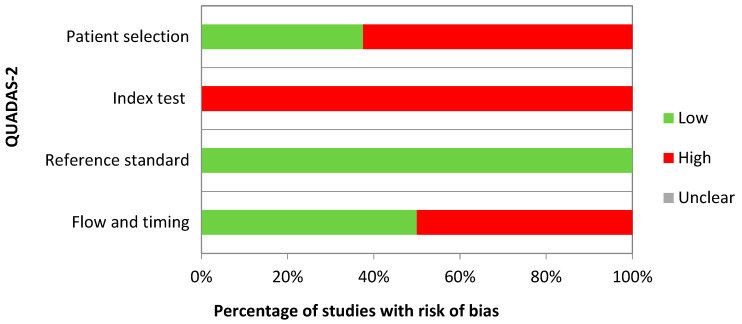

All studies included in the review underwent independent evaluation for quality by two reviewers, L.P. and C.S. They utilized the revised Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool (QUADAS-2) [19] to assess potential biases in four critical domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The agreement percentage between the two reviewers was calculated for each variable in QUADAS-2. Any discrepancies in coding or QUADAS-2 assessments were resolved through consensus discussions.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

We used STATA17.0 software to perform the statistical analyses. Pyramid plots were chosen to illustrate descriptive statistics on the directions of microRNA expression; sample subgroups were created to compare cfmiRNA expressions in different biological samples (serum and plasma).

3. Results

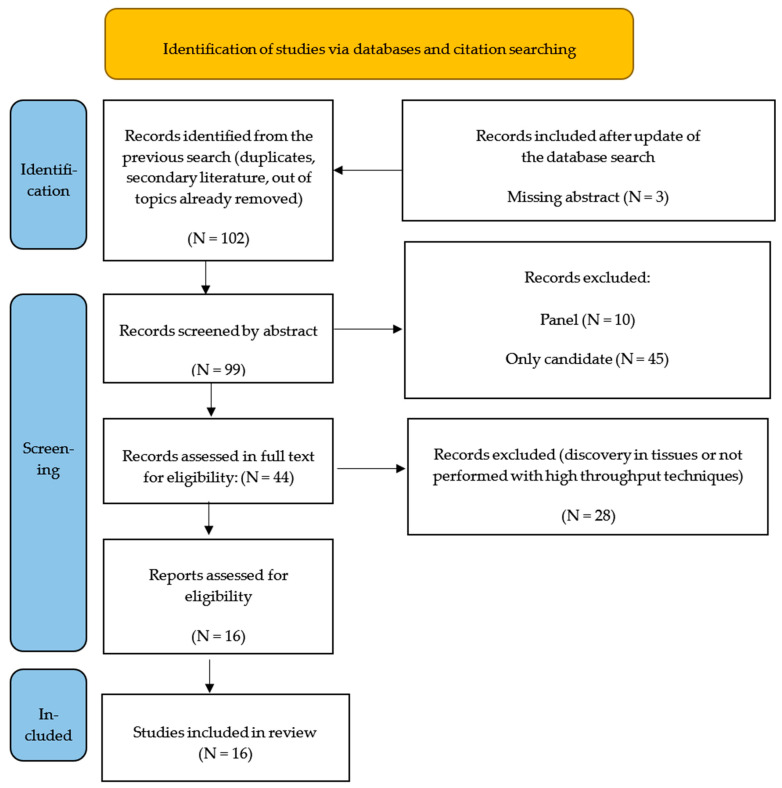

We took advantage of a previous literature review performed by our group, where from a total of 308 initially identified records, we excluded 206 records for several reasons (duplicates, secondary literature, being off topic, etc.) (see [13] for details). In total, 102 papers were considered in the screening stage for a manual review of titles and abstracts; 3 papers were excluded because the abstract was not available in English. After carefully examining the abstracts and, when useful, the full texts, an additional group of 83 publications were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e., the discovery phase was performed only in tissues, or the discovery technique was not of a high-throughput type). Ultimately, this review included 16 publications [19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. Figure 2 illustrates the flowchart depicting the paper exclusion process.

Figure 2.

Flow chart of identification, screening, and eligibility of the included studies (identification in [13]).

Table 1 provides a summary of the key features of these studies. This review encompassed a total of 585 breast cancer (BC) cases and 496 healthy controls. Among the included studies, only 1 out of 16 had more than 100 BC cases [24]. The studies were conducted in various countries, including China (N = 3), the USA (N = 3), Germany (N = 2), Italy (N = 1), Ireland (N = 1), Denmark (N = 1), the Czech Republic (N = 1), Australia (N = 1), Singapore (N = 1), Malaysia (N = 1), and Saudi Arabia (N = 1). Notably, most of the studies focused on a white European population (N = 6), while the remaining studies predominantly focused on Asiatic (N = 6) or mixed U.S. or Australian populations (N = 4). This supports the evidence that Black and Hispanic populations were relatively limited in the context of microRNA and breast cancer research.

Table 1.

General features of the studies included in the systematic review on the role of microRNA in breast cancer diagnosis.

| First Author, Year | Country | Specimen Source | Lab Technique | Case–Control Size | QUADAS-2 Domains with Risk of Bias | Applied Multiple Testing Correction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Germany | Blood | Geniom Biochip miRNA homo sapiens | 48/57 | Index test | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| Wu Q, 2012 [21] | China | Serum | Life Technologies SOLiD™ sequencing base miRNA expression profiling | 13/10 | Patient selection, Index test | Not applied |

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Singapore | Serum | Agilent Human miRNA microarray | 32/22 | Patient selection, Index test, Flow and timing | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Germany | Plasma | TLDA human MicroRNA Cards A v2.1 and B v2.0 | 10/10 | Patient selection, Index test | Benjamini–Hochberg * |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | USA | Plasma | TLDA human MicroRNA Cards A v2.1 and B v2.0 | 5/5 | Patient selection, Index test | Not applied |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | USA | Serum | Affimetrix GeneChip miRNA 2.0 array | 205/205 | Index test | Not applied |

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Denmark | Serum | Exiqon microRNA panel (miRCURY) | 48/24 | Index test | Bonferroni * |

| McDermott AM, 2014 [27] | Ireland | Blood | TLDA human MicroRNA Cards A v2.1 and B v2.0 | 10/10 | Index test | Not applied |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | USA | Plasma | Exiqon microRNA panel (miRCURY) | 52/35 | Index test, Flow and timing | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Australia | Serum | TLDA human MicroRNA Cards A and B v3.0 | 39/10 | Patient selection, Index test, Flow and timing | Bonferroni |

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Italy | Plasma | Agilent Human miRNA microarray | 18/18 | Patient selection, Index test, Flow and timing | Not applied |

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | China | Plasma | Exiqon microRNA panel (miRCURY) | 5/5 | Patient selection, Index test, Flow and timing | Not applied |

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | China | Serum | Serum-direct multiplex qRT-PCR (SdM-qRT-PCR) | 25/20 | Patient selection, Index test, Flow and timing | Bonferroni, Benjamini–Hochberg |

| Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Saudi Arabia | Blood | Agilent Human miRNA microarray | 23/9 | Patient selection, Index test, Flow and timing | Benjamini–Hochberg |

| Jusoh A, 2021 [34] | Malaysia | Plasma | Qiagen miScript miRNA PCR Array | 8/9 | Index test, Flow and timing | Not applied |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Czech Republic | Plasma | TLDA human MicroRNA Cards A v2.1 and B v2.0 | 7/7 | Patient selection, Index test | Benjamini–Hochberg |

Regarding the types of samples, some studies used serum (N = 6), while others used plasma (N = 7) or whole blood (N = 3).

The 17 studies included in the review employed different panels of microRNA assays: the TLDA human micro RNA cards (N = 5) was the most popular, followed by Exiqon microRBA panel miRCURY (N = 3) and Agilent Human microarray (N = 3).

The sixth column of Table 1 presents the QUADAS domains for which a potential risk of bias was identified in each study.

The quality assessment using the QUADAS-2 tool showed that the included studies had low applicability but a high risk of bias (Figure 3). A higher risk of bias was observed in many studies across the QUADAS-2 domains of patient selection, index testing, and flow and timing (respectively, 62.5%, 100%, and 50% of studies with a risk of bias). Patient selection involves detailing the methods of selecting patients, while index testing pertains to how the cfmiRNA analysis was conducted and interpreted, standard of reference assesses the accuracy of disease status classification, and flow and timing refer to the time interval and any interventions before cfmiRNA analysis. Indeed, several studies lacked sufficient detail on the patient selection process, such as whether cases consisted of consecutive patients or controls originated from the same population that produced the cases. Furthermore, there was insufficient information on the timing of biological sample retrieval, such as whether it occurred at diagnosis, before or after surgery, or during chemotherapy. The breast cancer diagnosis was histologically confirmed in all the studies, indicating a low risk of bias in the reference standard domain. In the category of the index test, some studies failed to mention whether a threshold was pre-specified.

Figure 3.

Quality assessment with the QUADAS-2 tool [18].

Furthermore, the authors of 9 out 16 studies applied a multiple testing correction in the cfmiRNA selection (mostly the Benjamini–Hochberg False Discovery Rate method), Moreover, Cuk et al. [23] and Kodhal et al. [26] also performed the adjustment for multiple comparisons, considering unadjusted p values for cfmiRNA selection in the validation phase.

The authors employed very heterogeneous criteria to select interesting cfmiRNAs for inclusion in the validation phase of their study. Godfrey et al. [24] and Shin et al. [32] focused on those demonstrating statistical significance in the discovery phase (p < 0.05). Schrauder et al. [20] selected the 25 top hits from statistically significant cfmiRNAs (p < 0.05). Chan et al. [22] chose cfmiRNAs with statistical significance (p < 0.05) excluding those with collinearity. Cuk et al. [23], Shen et al. [28], Zearo et al. [29], Zhang et al. [30], and Hamam et al. [33] used both statistical significance (all p < 0.05 except for Zearo p < 0.01) and fold change (generally FC > 2) as selection criteria. Ng et al. [25] and Jusoh et al. [34] opted for cfmiRNAs with a fold change greater than 2, while Ferracin et al. [31] selected those with the highest fold changes in plasma and serum. Wu et al. [21] focused exclusively on up-regulated cfmiRNAs (and showed them in a table) but validated only cfmiRNAs with the same pathway in serum and tissue. McDermott et al. [27] used the ANN data mining algorithm to identify cfmiRNAs with detectable and altered expression in patients. Záveský et al. [35] chose those with a Ct value exceeding 40, and finally, Kodahl et al. [26] performed automatic selection using component-wise likelihood-based boosting.

Table 2 shows the results of the studies included in this review.

Table 2.

Summary of the results of the studies included in the systematic review on the role of cfmiRNAs in breast cancer diagnosis. (For cfmiRNAs analyzed in Schrauder et al. [20], Chan et al. [22], Cuk at al. [23], Kodhal et al. [26], Shen et al. [28], Zearo et al. [29], Zhang et al. [30], Hamam et al. [33], and Záveský et al. [35], adjusted p value were reported. Only cfmiRNAs that demonstrated statistical significance in the discovery phase have been included in the table. However, for Cuk et al. [23] and Kodhal et al. [26], non-significant adjusted p-values were reported since the authors considered unadjusted statistically significant p-values during the selection for the validation phase. About Záveský et al. [35], we decided to include all the miRNAs with a Ct-cutoff < 35, and to minimize data loss, we also added all the miRNAs that had not already been included with a Ct cut-off ≤ 40).

| MIR | First Author, Year | Specimen Source | Direction | AUC | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 7 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 16 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | down | <0.05 | ||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.001 | ||

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.038 | ||

| 17 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.001 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.017 | ||

| 21 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | up | |||

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | down | <0.05 | ||

| 22 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| Jusoh A, 2021 [34] | Plasma | up | 0.83 | 0.020 | |

| 24 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.65 | 0.023 |

| Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | |||

| 25 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| 28 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.005 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.85 | <0.001 | |

| 93 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 95 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.023 | |

| 96 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.008 | |

| 100 | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.79 | 0.003 |

| 101 | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.024 | |

| 103 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 107 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.68 | 0.041 |

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.013 | ||

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | up | 0.006 | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.87 | <0.001 | |

| 126 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.77 | <0.001 | |

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 127 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.459 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.75 | <0.001 | |

| 128 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.010 | |

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.039 | ||

| 134 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.044 | |

| Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.042 | ||

| 136 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| 139 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | down | 0.320 | |

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | down | 0.623 | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.79 | <0.001 | |

| 140 | Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 141 | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.89 | 0.027 |

| 142 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.001 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.82 | <0.001 | |

| 143 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | down | 0.073 | ||

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | down | <0.05 | ||

| 144 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | down | 0.94 | <0.001 | |

| 145 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.036 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | |||

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | down | <0.001 | ||

| Jusoh A, 2021 [34] | Plasma | up | 0.82 | 0.040 | |

| 149 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.030 | |

| 150 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.033 | ||

| 151 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.030 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.88 | <0.001 | |

| 152 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.75 | 0.002 |

| 154 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| 155 | Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | 0.008 | |

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.017 | ||

| 182 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.71 | 0.008 |

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.009 | ||

| 183 | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.79 | 0.003 |

| 184 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.332 | |

| 185 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | down | <0.05 | ||

| 186 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 188 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.004 | |

| 190 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.459 | |

| 191 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.018 | ||

| 192 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 194 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | down | 0.81 | 0.002 | |

| 195 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.007 | |

| 202 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.72 | 0.020 |

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | down | 0.005 | ||

| 205 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.011 | |

| 206 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | down | 0.320 | |

| 210 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.044 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| 214 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.017 | ||

| 221 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.84 | <0.001 |

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | down | <0.05 | ||

| 222 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.020 | ||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 223 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | <0.001 | ||

| 296 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 320 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | ||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 324 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | ||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.88 | <0.001 | |

| 326 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.88 | <0.001 |

| 328 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.80 | <0.001 | |

| 330 | Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.017 | |

| 331 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.71 | 0.006 |

| 335 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.74 | 0.040 |

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.009 | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.73 | 0.006 | |

| 338 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | <0.001 | |

| 339 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.021 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.76 | <0.001 | |

| 342 | Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | up | <0.05 | ||

| 363 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.003 | |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.030 | ||

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.011 | ||

| 365 | Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | down | 0.006 | |

| 374 | Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.022 | |

| 375 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | down | 0.74 | 0.003 |

| 378 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.013 | |

| 382 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.72 | <0.001 |

| 409 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.332 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.78 | <0.001 | |

| 421 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.009 | |

| 423 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.82 | <0.001 | |

| 424 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.322 | |

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.86 | 0.002 | |

| Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.044 | ||

| 425 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.020 | |

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | up | 0.119 | ||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | up | |||

| 429 | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 451 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.002 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| 454 | Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 483 | Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | 0.016 | |

| Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.038 | ||

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.004 | ||

| 484 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.008 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.84 | <0.001 | |

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 485 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.87 | <0.001 | |

| 486 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 494 | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | ||

| 495 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| 497 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.75 | 0.010 |

| 501 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.023 | |

| 543 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| 564 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.67 | 0.012 |

| 571 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | down | 0.100 | |

| 574 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.027 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| 576 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 584 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.005 | |

| 598 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.020 | |

| 605 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | down | 0.050 | |

| 624 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.027 | |

| 625 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.77 | 0.002 |

| 627 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.030 | |

| 629 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.009 | |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.050 | ||

| 652 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.030 | |

| 660 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.004 | |

| 664 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.050 | |

| 671 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.010 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.029 | ||

| 718 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.77 | 0.004 |

| 744 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.020 | |

| 760 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | down | 0.020 | |

| 762 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.042 | |

| 766 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.011 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.86 | <0.001 | |

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | down | |||

| 801 | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.320 | |

| 874 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.74 | 0.001 |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | |||

| 877 | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.043 | |

| 922 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.65 | 0.030 |

| 1202 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.006 | |

| 1207 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.020 | |

| 1225 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.004 | |

| 1234 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | down | 0.030 | |

| 1290 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.022 | |

| 1323 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.69 | 0.040 |

| 1469 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.68 | 0.008 |

| 1471 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.70 | 0.012 |

| 1827 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.010 | |

| 1914 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.044 | |

| 1915 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.75 | 0.002 |

| 1974 | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.85 | <0.001 |

| 2355 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.73 | 0.004 |

| 3130 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.73 | 0.004 |

| 3136 | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.050 | |

| 3141 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.029 | |

| 3156 | Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | down | ||

| 3186 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.75 | 0.002 |

| 3652 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.044 | |

| 4257 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.65 | 0.040 |

| 4270 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.001 | |

| 4281 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.019 | |

| 4298 | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.035 | |

| 4306 | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.71 | 0.020 |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.030 | ||

| 106a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | |||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.018 | ||

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.038 | ||

| 106b | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.72 | 0.010 |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.017 | ||

| 10a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.029 | ||

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| 10b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 1255a | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | <0.01 | |

| 125a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | up | |||

| 125b | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.017 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.014 | ||

| 130a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.020 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.87 | <0.001 | |

| 130b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.002 | |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.030 | ||

| 133a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | down | 0.479 | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.80 | <0.001 | |

| 133b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 135b | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.87 | <0.001 |

| 146b | Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 148a | Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | ||

| 148b | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.320 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.81 | <0.001 | |

| 15a | Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | up | =1 | |

| 15b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.003 | |

| 181a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.023 | ||

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.050 | ||

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | down | |||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.86 | <0.001 | |

| 181b | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 181c | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.038 | |

| 18a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.004 | |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.040 | ||

| Kodahl AR, 2014 [26] | Serum | up | 0.007 | ||

| 18b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.002 | |

| Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | down | 0.040 | ||

| 193a | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | down | 0.320 | ||

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | down | |||

| 193b | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.80 | 0.002 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.017 | ||

| 196b | Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.041 | |

| 199a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.013 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.84 | <0.001 | |

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | down | <0.05 | ||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.84 | 0.001 | |

| 19a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.016 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.038 | ||

| 200b | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 200c | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| 20a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.017 | ||

| 20b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.001 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.011 | ||

| 23a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 23b | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.76 | 0.009 | |

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | up | <0.05 | ||

| 26a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 26b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.005 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.011 | ||

| 27a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| 27b | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Jusoh A, 2021 [34] | Plasma | up | 0.82 | 0.010 | |

| 29a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.029 | ||

| 29b | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 29c | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.81 | 0.001 | |

| 30a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.029 | |

| 30b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.027 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.76 | <0.001 | |

| 30c | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.77 | <0.001 |

| 30d | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.008 | |

| 30e | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| 320a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Ferracin M, 2015 [31] | Plasma | up | |||

| 320b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| 320d | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | up | 0.040 | |

| 33a | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.79 | <0.001 |

| 34a | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.044 | |

| 374a | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.75 | 0.004 |

| 374b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.007 | |

| 376a | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.386 | |

| 376c | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | up | 0.224 | |

| 449b | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| 516b | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.67 | 0.030 |

| Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.038 | ||

| 519a | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | down | 0.407 | |

| 519c | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.85 | 0.003 |

| 520c | Zhang L, 2015 [30] | Serum | up | 0.80 | 0.003 |

| 526a | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | down | 0.72 | 0.013 |

| 526b | Cuk K, 2013 [23] | Plasma | down | 0.386 | |

| 548b | Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.001 | |

| 548c | Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.035 | |

| 548d | Godfrey AC, 2013 [24] | Serum | down | 0.010 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.002 | ||

| 551a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | down | 0.002 | |

| 642b | Hamam R, 2016 [33] | Blood | up | 0.020 | |

| 92a | Wu Q, 2012 [21] | Serum | up | ||

| Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Shin VY, 2015 [32] | Plasma | up | <0.05 | ||

| 92b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.003 | |

| 99b | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.81 | <0.001 |

| let7a | Schrauder MG, 2012 [20] | Blood | up | 0.65 | 0.030 |

| let-7a | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.005 | |

| let-7b | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| Zearo S, 2014 [29] | Serum | up | <0.001 | ||

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.026 | ||

| let-7c | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.009 | |

| Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | down | 0.038 | ||

| let-7d | Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.89 | <0.001 |

| let-7f | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.016 | |

| Shen J, 2014 [28] | Plasma | up | 0.81 | <0.001 | |

| let-7g | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | 0.002 | |

| Ng E K, 2013 [25] | Plasma | up | |||

| let-7i | Chan M, 2013 [22] | Serum | up | <0.001 | |

| U6 snRNA | Záveský L, 2022 [35] | Plasma | up | 0.004 |

To summarize the results of the studies, we decided not to discriminate between mature miRNAs originating from the opposite arms of the same precursor miRNA (i.e., we did not include suffixes such as ‘−3p’ or ‘−5p’ in the tables and figures).

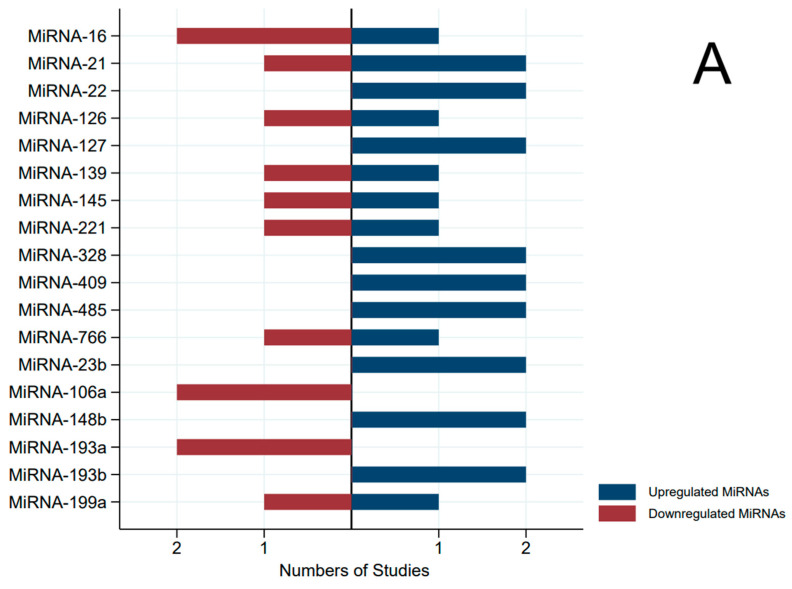

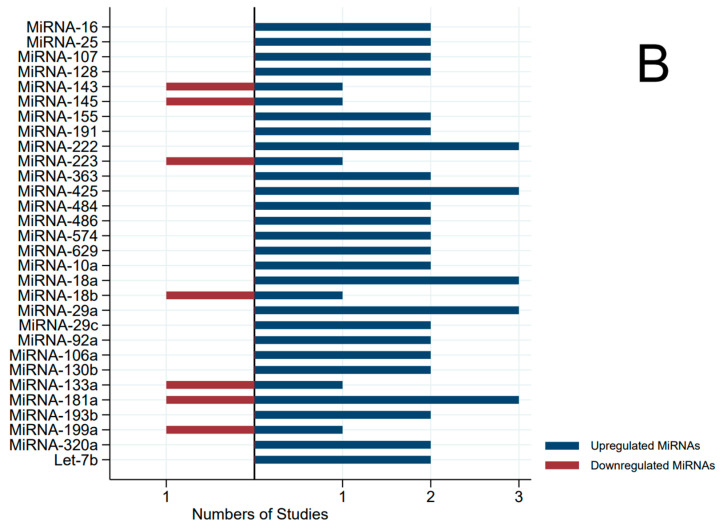

The most interesting miRNAs that appear to be cfmiRNAs deserving validation in further studies are MIR16, MIR145, MIR106a, MIR193b, and MIR199a. In fact, these specific cfmiRNAs emerged in at least two independent papers for each sample type, both in serum and plasma studies as potential candidates for validation studies (Figure 4). Moreover, only MIR193b showed a coherent direction among the cases and controls.

Figure 4.

Pyramidal graph of the direction of miRNA expression (microRNA concentration in breast cancer cases versus controls) by type of specimens (only microRNAs that were analyzed in two or more independent studies). (A) Plasma; (B) serum.

The data in McDermott [27] were not included in Table 2 due to the lack of information on the direction, AUC, and p-value. Suffixes such as ‘−3p’ or ‘−5p’ are not considered in the cfmiRNA description.

The two cfmiRNAs that were selected as the most interesting in terms of coherence among studies in the previous metanalyses (MIR21 and MIR155) [13,14] emerged as statistically significant in the discovery phases only in plasma or serum, respectively.

Forty-two other cfmiRNAs other than MIR21 and MIR155 showed statistically significant different concentrations between the BC cases and healthy controls in at least two studies.

Unfortunately, the considered articles do not provide adequate data to draw a metanalysis forest plot.

4. Discussion

In a previous paper by our group, we conducted a systematic review of clinical studies on cfmiRNAs for the diagnosis of BC [13]. The review encompassed all studies that validated or analyzed candidate genes. In that study, we found a lack of consistency in the circulating cfmiRNAs identified across various studies. Similar results have been described in previous reviews [14,15,16,17].

This lack of replication among studies could be attributed to several factors, such as variations in the methods used for selecting cfmiRNAs, the absence of standardized techniques (including differences in sample collection and preservation, laboratory methodologies, cfmiRNA measurement and normalization, and cut-off values), inconsistent patient selection, limited cfmiRNA abundance, small sample sizes, and inadequate statistical analysis.

Recognizing the discovery phase as a potential contributor to inconsistency in the results, we performed a review of the studies that involved a discovery phases. The aim of the present work was to describe and resume the results of discovery phase studies to find the most promising cfmiRNAs that could be replicated in future candidate cfmiRNA studies. Furthermore, we will try to at least explain the lack of reproducibility of the previous candidate studies.

In general, the accurate quantification of cfmiRNAs in body fluids poses several challenges due to their low abundance and small size. This is particularly challenging for discovery studies that, in order to detect large numbers of cfmiRNAs simultaneously, use microarray profiling, quantitative RT-PCR profiling, or targeted assays of specific cfmiRNAs.

The most common biofluids used for cfmiRNA analysis are whole blood, serum, and plasma. Moreover, using the same sample type, different methods of sample preparation, anticoagulation, centrifugation, and storage properties, especially if the same high-throughput technique were used, contributed to variability and inconsistencies between reported results.

Another critical step in discovery studies is normalization, which contributes to the heterogeneity of the results. Deng et al. proposed a solution to the normalization issue which might produce more consistent results [36]; however, very few studies applied this method.

Furthermore, the same normalization issue was encountered in the collection of fold changes; they could not be compared as they were constructed using different methods, resulting in varying normalizations with the 2-delta method [37], percentage variations, and concentration ratios.

This highlights the necessity of standardized statistical analyses during discovery phases, especially when comparing cfmiRNAs concentrations between cases and controls. An illustrative example of the lack of standardization is the observed omission of multiple testing adjustment, a factor that could potentially introduce bias. In fact, implementing a p-value cutoff for candidate selection could introduce inflated effect sizes, thereby potentially distorting results. For this reason, it is essential to strike a careful balance between not adjusting for multiple comparison and diminishing statistical power due to the selection of a reduced number of candidate biomarkers.

Due to the considerable variability in the outcomes of cfmiRNA studies, as described above, consolidating the findings of diverse studies through systematic reviews enables an improvement in the body of evidence. In particular, five cfmiRNAs (MIR16, MIR145, MIR106a, MIR193b, and MIR199a) emerged from the discovery phases both in serum and in plasma in at least two independent papers as potential candidates for validation studies for BC diagnosis. This result is weakened by the fact that these miRNAs except one (MIR193b) showed varying counts between cases and controls, with inconsistent directions across different studies.

In addition to the necessity of conducting well-designed rigorous studies, there exists a critical need to enhance the reporting of scientific research. Checklists designed to assist authors in reporting biomarker studies, such as those provided by the STROBE-ME (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology—Molecular Epidemiology) initiative, could significantly aid in crafting scientific papers with essential information concerning the collection, handling, and storage of biological samples; laboratory methods; the validity and reliability of biomarkers; nuances of study design; and ethical considerations [38].

Accurate and standardized reporting has the potential to greatly contribute to the accumulation of information in systematic reviews, which, in turn, can facilitate the advancement of our understanding of miRNA dynamics and their associations with various cancers.

5. Conclusions

The discovery phases of studies on biomarkers are crucial for identifying interesting signals to translate into clinical diagnostics. The bias encountered in this phase could cause a suboptimal discovery of new candidate biomarkers and could nullify the research effort.

For the aforementioned reason, we express our hope that forthcoming studies on cfmiRNAs that remain a promising biomarker to be implemented in liquid biopsies for BC diagnosis will have robust design and standardized procedures.

Studies including Black or Hispanic populations, other age groups, and patients with other medical conditions should be run. Additionally, it would be beneficial to capitalize on high-throughput laboratory technologies to conduct discovery studies using an appropriate sample size; to adopt a prospective design; and to adhere to standardized protocols for sample preparation, normalization, and data analysis.

Finally, researchers publishing articles on miRNAs and breast cancer should adhere to the STROBE-ME checklist when composing their papers. This approach is poised to significantly enhance the quality of their work and to propel advancements in knowledge within this domain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S., L.D.M. and F.R.; methodology, L.P., V.F., G.M., F.R. and C.S.; validation, C.S., L.D.M. and M.T.G.; formal analysis, L.P., L.M. and A.M.; data curation, L.P., L.M., A.M. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, C.S. and L.P.; writing—review and editing, all authors; supervision, all authors; funding acquisition, C.S. and L.D.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (project n. RF 2018 12366921).

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

- 1.Loh H.Y., Norman B.P., Lai K.S., Rahman N.M.A.N.A., Alitheen N.B.M., Osman M.A. The Regulatory Role of MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:4940. doi: 10.3390/ijms20194940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catalanotto C., Cogoni C., Zardo G. MicroRNA in control of gene expression: An overview of nuclear functions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17:1712. doi: 10.3390/ijms17101712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy K.B. MicroRNA (miRNA) in cancer. Cancer Cell Int. 2015;15:38. doi: 10.1186/s12935-015-0185-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Melo S.A., Esteller M. Dysregulation of microRNAs in cancer: Playing with fire. FEBS Lett. 2011;585:2087–2099. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.08.009. Erratum in FEBS Lett. 2021, 595, 2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang W., Luo Y.P. MicroRNAs in breast cancer: Oncogene and tumor suppressors with clinical potential. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2015;16:18–31. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1400184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strati A., Markou A., Kyriakopoulou E., Lianidou E. Detection and Molecular Characterization of Circulating Tumour Cells: Challenges for the Clinical Setting. Cancers. 2023;15:2185. doi: 10.3390/cancers15072185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cuk K., Obernosterer G., Leuschner P.J., Alenius M., Martinez J. Post-transcriptional regulation of microRNA expression. RNA. 2006;12:1161–1167. doi: 10.1261/rna.2322506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hamam R., Hamam D., Alsaleh K.A., Kassem M., Zaher W., Alfayez M., Aldahmash A., Alajez N.M. Circulating microRNAs in breast cancer; novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8:e3045. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y. Study Design Considerations for Cancer Biomarker Discoveries. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2018;3:282–289. doi: 10.1373/jalm.2017.025809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin L.-X., Levine D.A. Study design and data analysis considerations for the discovery of prognostic molecular biomarkers: A case study of progression free survival in advanced serous ovarian cancer. BMC Med. Genom. 2016;9:27. doi: 10.1186/s12920-016-0187-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diamandis E.P. Cancer biomarkers: Can we turn recent failures into success? J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2010;102:1462–1467. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djq306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pepe M.S., Li C.I., Feng Z. Improving the quality of biomarker discovery research: The right samples and enough of them. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2015;24:944–950. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-14-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Padroni L., De Marco L., Dansero L., Fiano V., Milani L., Vasapolli P., Manfredi L., Caini S., Agnoli C., Ricceri F., et al. An Epidemiological Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis on Biomarker Role of Circulating MicroRNAs in Breast Cancer Incidence. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023;24:3910. doi: 10.3390/ijms24043910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bahramy A., Zafari N., Rajabi F., Aghakhani A., Jayedi A., Khaboushan A.S., Zolbin M.M., Yekaninejad M.S. Prognostic and diagnostic values of non-coding RNAs as biomarkers for breast cancer: An umbrella review and pan-cancer analysis. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023;10:1096524. doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2023.1096524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen T.H.N., Nguyen T.T.N., Nguyen T.T.M., Nguyen L.H.M., Huynh L.H., Phan H.N., Nguyen H.T. Panels of circulating microRNAs as potential diagnostic biomarkers for breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2022;196:1–15. doi: 10.1007/s10549-022-06728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sehovic E., Urru S., Chiorino G., Doebler P. Meta-analysis of diagnostic cell-free circulating microRNAs for breast cancer detection. BMC Cancer. 2022;22:634. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09698-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dabi Y., Bendifallah S., Suisse S., Haury J., Touboul C., Puchar A., Favier A., Daraï E. Overview of non-coding RNAs in breast cancers. Transl. Oncol. 2022;25:101512. doi: 10.1016/j.tranon.2022.101512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath T.A., Alabousi M., Skidmore B., Korevaar D.A., Bossuyt P.M.M., Moher D., Thombs B., McInnes M.D.F. Recommendations for reporting of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of diagnostic test accuracy; a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2017;6:194. doi: 10.1186/s13643-017-0590-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whiting P.F., Rutjes A.W., Westwood M.E., Mallett S., Deeks J.J., Reitsma J.B., Leeflang M.M., Sterne J.A., Bossuyt P.M., QUADAS-2 Group QUADAS-2: A revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2011;155:529–536. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schrauder M.G., Strick R., Schulz-Wendtland R., Strissel P.L., Kahmann L., Loehberg C.R., Lux M.P., Jud S.M., Hartmann A., Hein A., et al. Circulating micro-RNAs as potential blood-based markers for early stage breast cancer detection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e29770. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Q., Wang C., Lu Z., Guo L., Ge Q. Analysis of serum genome-wide microRNAs for breast cancer detection. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2012;413:1058–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan M., Liaw C.S., Ji S.M., Tan H.H., Wong C.Y., Thike A.A., Tan P.H., Ho G.H., Lee A.S. Identification of circulating microRNA signatures for breast cancer detection. Clin. Cancer Res. 2013;19:4477–4487. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cuk K., Zucknick M., Heil J., Madhavan D., Schott S., Turchinovich A., Arlt D., Rath M., Sohn C., Benner A., et al. Circulating microRNAs in plasma as early detection markers for breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer. 2013;132:1602–1612. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Godfrey A.C., Xu Z., Weinberg C.R., Getts R.C., Wade P.A., DeRoo L.A., Sandler D.P., Taylor J.A. Serum microRNA expression as an early marker for breast cancer risk in prospectively collected samples from the Sister Study cohort. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R42. doi: 10.1186/bcr3428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ng E.K., Li R., Shin V.Y., Jin H.C., Leung C.P., Ma E.S., Pang R., Chua D., Chu K.M., Law W.L., et al. Circulating microRNAs as specific biomarkers for breast cancer detection. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e53141. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kodahl A.R., Lyng M.B., Binder H., Cold S., Gravgaard K., Knoop A.S., Ditzel H.J. Novel circulating microRNA signature as a potential non-invasive multi-marker test in ER-positive early-stage breast cancer; a case control study. Mol. Oncol. 2014;8:874–883. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2014.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDermott A.M., Miller N., Wall D., Martyn L.M., Ball G., Sweeney K.J., Kerin M.J. Identification and validation of oncologic miRNA biomarkers for luminal A-like breast cancer. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen J., Hu Q., Schrauder M., Yan L., Wang D., Medico L., Guo Y., Yao S., Zhu Q., Liu B., et al. Circulating miR-148b and miR-133a as biomarkers for breast cancer detection. Oncotarget. 2014;5:5284–5294. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zearo S., Kim E., Zhu Y., Zhao J.T., Sidhu S.B., Robinson B.G., Soon P.S. MicroRNA-484 is more highly expressed in serum of early breast cancer patients compared to healthy volunteers. BMC Cancer. 2014;14:200. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-14-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L., Xu Y., Jin X., Wang Z., Wu Y., Zhao D., Chen G., Li D., Wang X., Cao H., et al. A circulating miRNA signature as a diagnostic biomarker for non-invasive early detection of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 2015;154:423–434. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3591-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ferracin M., Lupini L., Salamon I., Saccenti E., Zanzi M.V., Rocchi A., Da Ros L., Zagatti B., Musa G., Bassi C., et al. Absolute quantification of cell-free microRNAs in cancer patients. Oncotarget. 2015;6:14545–14555. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shin V.Y., Siu J.M., Cheuk I., Ng E.K., Kwong A. Circulating cell-free miRNAs as biomarker for triple-negative breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;112:1751–1759. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hamam R., Ali A.M., Alsaleh K.A., Kassem M., Alfayez M., Aldahmash A., Alajez N.M. microRNA expression profiling on individual breast cancer patients identifies novel panel of circulating microRNA for early detection. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:25997. doi: 10.1038/srep25997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jusoh A.R., Mohan S.V., Ping T.L., Bin T.A., Din T., Haron J., Romli R.C., Jaafar H., Nafi S.N., Salwani T.I., et al. Plasma Circulating Mirnas Profiling for Identification of Potential Breast Cancer Early Detection Biomarkers. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2021;22:1375–1381. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2021.22.5.1375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Záveský L., Jandáková E., Weinberger V., Minář L., Hanzíková V., Dušková D., Faridová A., Turyna R., Slanař O., Hořínek A., et al. Small non-coding RNA profiling in breast cancer: Plasma U6 snRNA, miR-451a and miR-548b-5p as novel diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022;49:1955–1971. doi: 10.1007/s11033-021-07010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Deng Y., Zhu Y., Wang H., Khadka V.S., Hu L., Ai J., Dou Y., Li Y., Dai S., Mason C.E., et al. Ratio-based method to identify true biomarkers by normalizing circulating ncRNA sequencing and quantitative PCR Data. Anal. Chem. 2019;91:6746–6753. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b00821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallo V., Egger M., McCormack V., Farmer P.B., Ioannidis J.P., Kirsch-Volders M., Matullo G., Phillips D.H., Schoket B., Stromberg U., et al. STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology—Molecular Epidemiology STROBE-ME: An extension of the STROBE statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2011;64:1350–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2011.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.