Abstract

A cold-adapted protease subtilisin was successfully isolated by evolutionary engineering based on sequential in vitro random mutagenesis and an improved method of screening (H. Kano, S. Taguchi, and H. Momose, Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 47:46–51, 1997). The mutant subtilisin, termed m-63, exhibited a catalytic efficiency (expressed as the kcat/Km value) 100% higher than that of the wild type at 10°C when N-succinyl-l-Ala-l-Ala-l-Pro-l-Phe-p-nitroanilide was used as a synthetic substrate. This cold adaptation was achieved with three mutations, Val to Ile at position 72 (V72I), Ala to Thr at position 92 (A92T), and Gly to Asp at position 131 (G131D), and it was found that an increase in substrate affinity (i.e., a decreased Km value) was mostly responsible for the increased activity. Analysis of kinetic parameters revealed that the V72I mutation contributed negatively to the activity but that the other two mutations, A92T and G131D, overcame the negative contribution to confer the 100% increase in activity. Besides suppression of the activity-negative mutation (V72I) by A92T and G131D, suppression of structural stability was observed in measurements of activity retention at 60°C and circular dichroism spectra at 10°C.

Biological systems have evolved over billions of years to perform very specific biological functions within the context of living organisms. From the evolution of natural proteins, we have learned that proteins are highly adaptable, constantly changing biomolecules. Accordingly, we can explore the functions of protein molecules free from the constraints of a living system by mimicking some of the processes of Darwinian evolution in the test tube. We have been attempting to use “evolutionary engineering” to improve enzyme proteins for practical purposes. Evolutionary engineering can be defined as a technological alternative to protein engineering for the creation of desired enzymes based on a Darwinian sequential program of mutagenesis and selection. To date, the pioneering works have concentrated on the application of evolution engineering to the isolation of thermostable enzymes (7, 16) and organic solvent-adapted enzymes (1).

Cold adaptation of enzymes would be an attractive project covering a wide range of applications, e.g., food processing, washing, biosynthetic processes with volatile intermediates, and environmental bioremediation. Very recently, extensive attempts to isolate different types of cold-adapted enzymes from psychrophilic organisms have been made by Gerday and coworkers (2, 3). In contrast, we have initiated for the first time an artificial evolution program for the cold adaptation of subtilisin BPN′, a mesophilic and industrially useful alkaline serine protease. Fortunately, the tertiary structure of subtilisin has been well established, and the enzyme is a good model to which protein engineering can be applied for alteration of its properties. However, much of the theoretical basis for designing a cold-adapted subtilisin is still unclear. If we were able to obtain a variety of cold-adapted subtilisins, rich background data on the structure-function relationship of this enzyme would be of enormous value in helping to clarify the molecular mechanism of cold adaptation.

For this purpose, we originally devised an evolution system for multistep random mutagenesis connected with screening of the evolved enzymes with an Escherichia coli host vector and also established a system for enzyme overproduction with a Bacillus subtilis host vector (14) to allow enzymatic analysis of the evolvants. In the present communication, we describe our improved evolution system and the isolation and characterization of a cold-adapted subtilisin which exhibits activity 100% higher than that of the wild-type enzyme at 10°C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression systems.

E. coli JM109 (15) was used as the host strain for the screening of subtilisin mutants on proteolytic activity assay plates (2% skim milk, 1% lactose, 1% yeast extract, 50 μg of ampicillin per ml) established by us previously (14). The recombinant subtilisin gene on plasmid pUC18 (15) was expressed under the influence of the original promoter of subtilisin and the lac promoter in E. coli. For overproduction of the recombinant subtilisin, the host strain B. subtilis UOT0999 was cultivated in liquid Luria-Bertani medium (10) containing 20 μg of tetracycline per ml.

In vitro random mutagenesis.

Mutagenesis was performed for the whole pUC18 plasmid harboring the wild-type subtilisin gene (approximately 2 kb) by treatment with hydroxylamine at 65°C for 2 h in 0.1 M sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 1 mM EDTA (14). The mutagenized plasmid DNA was redissolved in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0) containing 1 mM EDTA. The mutation point was analyzed by dideoxynucleotide chain termination sequencing with a BcaBEST kit (Takara Shuzo). Six sequencing primers were synthesized by the solid-phase phosphoamidite method with an Applied Biosystems 381A DNA synthesizer (12).

Screening system.

A mixture of the EcoRI-HindIII fragment including the mutagenized subtilisin gene was cut out and religated into the pUC18 plasmid to generate a mutant library. When E. coli JM109 was transformed with the recombinant plasmid and cultivated on the skim milk plate at 37°C overnight to form transformant colonies, detectable clear zones, caused by proteolysis of the skim milk, appeared around the colonies after a further 2 days of incubation at 10°C. The change in the proteolytic activity of mutant subtilisins was judged on the basis of the velocity of formation of the clear zone at the initial stage. For precise estimation of the catalytic properties of the mutant subtilisin, the DNA fragment including the subtilisin gene was subcloned into the EcoRI-HindIII sites of pHY300PLK (4), a shuttle expression vector between E. coli and B. subtilis, and the recombinant subtilisin was overproduced by B. subtilis UOT0999.

Site-directed mutagenesis.

To prepare two single-mutant subtilisins, with the V72I or A92T mutation, two mutagenic primers were synthesized as follows: 5′-CCGGCACA(G→A)TTGCGGCT-3′ for V72I (MUT-V72I) and 5′-CACTTTAC(G→A)CTGTAAAA-3′ for A92T (MUT-A92T). The target mutation was introduced with the primer pairs MUT4 (Takara Shuzo) and mutagenic primers described above (for the first PCR) and M13 primer RV (Takara Shuzo) and M13 primer M4 (Takara Shuzo) (for the first and second PCRs) via heteroduplex formation between the first two PCR products (5). PCR was carried out with programs of 25 cycles of 94°C for 30 s (denaturation), 55°C for 2 min (annealing), and 72°C for 3 min (elongation) (for the first PCR) and 10 cycles under the same conditions as those for the first PCR (for the second PCR). The single-stranded region of the heteroduplex was filled in by the second PCR followed by double digestion with EcoRI and HindIII. The double-stranded DNA fragment carrying the target mutation could, in principle, be selectively digested with both enzymes and subjected to cloning into the same restriction sites of the plasmids, pUC18 and pHY300PLK, respectively. Three double mutants, with the V72I A92T, A92T G131D, or G131D V72I mutations, were constructed by genetic engineering with unique restriction sites located between positions 72 and 92 and between positions 92 and 131.

Enzyme purification.

A recombinant B. subtilis harboring the wild-type or mutated subtilisin gene was cultivated at 37°C for 24 h in 100 ml of Luria-Bertani medium containing a final concentration of 20 μg of tetracycline per ml. Subtilisin excreted into the medium was recovered by ammonium sulfate precipitation (40% saturation) followed by dialysis against 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 6.3) for 2 days. The dialysate was subjected to ion-exchange chromatography on a DEAE-cellulose column and eluted out with 20 mM phosphate buffer. The pass-through fraction was further purified by carboxymethyl-cellulose column chromatography with a linear gradient of 0 to 0.2 M NaCl. The purified sample was precipitated by adding a fourfold volume of acetone to the fraction containing subtilisin. The purity of the recovered samples was checked by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15% polyacrylamide).

Assay for subtilisin activity.

Wild-type and mutant subtilisin activities were measured at various temperatures by monitoring the release of p-nitroaniline at 410 nm as a result of enzymatic hydrolysis of N-succinyl-l-Ala-l-Ala-l-Pro-l-Phe-p-nitroanilide (AAPF) (0.02 to 0.8 mM) in 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.6) containing 2 mM CaCl2 (14). A 10-μl aliquot of 4 to 8 μM purified subtilisins or culture supernatant subtilisins was mixed rapidly with 990 μl of the above substrate solution to give a final reaction volume of 1 ml. The apparent concentration of subtilisin was determined spectrophotometrically with an absorbance coefficient, E280 nm1%, of 11.7 (9). The precise quantification of each purified active subtilisin was performed by active-site titration with the specific proteinaceous inhibitor, Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor (8). The Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at pH 7.0 with an absorbance at 276 nm (1 mg/ml) of 0.829 (14). The estimated value was used to correct the value of specific activity and the kinetic constant, kcat. Preincubation times before addition of enzyme were 30 to 60 min. A Uni Cool type UC-55N apparatus (EYELA) was used as a cooling unit for control of the proteolysis reaction.

Thermal stability of subtilisin.

A 1-ml aliquot of 1 μM purified subtilisin was incubated at 60°C, and 50 μl of each sample was taken up at various time intervals and immediately cooled on ice. The residual subtilisin activity was measured with AAPF as the substrate as described previously (14).

CD spectra of subtilisin.

Wild-type and mutant subtilisins were dissolved in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 2 mM CaCl2 to give a protein concentration of about 200 μg/ml. The circular dichroism (CD) spectrum for each sample solution was recorded at 10°C with a JASCO-J500 CD spectrophotometer. The temperature was controlled by circulating thermostatically regulated water in the water jacket of the cuvettes (light path length, 1 mm).

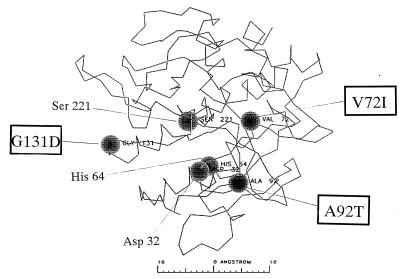

Computer graphics study.

The refined tertiary structure of subtilisin BPN′ (Protein Data Bank-ID no. 2SIC) was used as a data source for computational analysis (13). Distances among mutation points in mutant m-63 are presented in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

Mapping of the mutations on the tertiary structure of subtilisin BPN′. The catalytic triad of residues, Ser-221, His-64, and Asp-32, are indicated by closed circles. Cold-adapted mutant subtilisin, m-63, possesses three mutations, V72I, A92T, and G131D. Cα distances between mutation points themselves and between mutation points and catalytic triad residues are described as follows: 72 to 92, 12.2 Å; 92 to 131, 24.0 Å; 131 to 72, 26.5 Å; 72 to 32, 13.1 Å; 72 to 64, 13.0 Å; 72 to 221, 11.7 Å; 92 to 32, 7.4 Å; 92 to 64, 10.7 Å; 92 to 221, 15.7 Å; 131 to 32, 18.3 Å; 131 to 64, 22.8 Å; 131 to 221, 18.5 Å.

RESULTS

Isolation of a cold-adapted subtilisin.

The strategy for screening mutant subtilisins with increased activity at low temperatures consisted of two-step mutagenesis. As a primary mutation, activity-negative mutant subtilisins were screened on the basis of nondetectable activity on the skim milk plate; as a secondary mutation, activity-positive mutant subtilisins produced by intragenic suppression were screened from the primary mutants. The subtilisin mutants with reduced activities (primary mutants) were easily screened by detecting colonies with no clear zone. A total of 700 activity-negative mutants selected in the primary mutation were supplied as a mixture for the secondary-mutation experiment. Previously, in the secondary screening, activity-positive mutants were selected as candidates from colonies forming clear zones at least as large as that of the wild type (6). However, it was difficult to discriminate subtle differences in activity among activity-positive mutants when clear-zone formation became saturated. In fact, candidates were screened with high efficiency (0.02%), but some of them showed almost the same activity as that of the wild-type subtilisin. To conduct a more reliable screening of the mutant subtilisins showing activity recovery, we changed the selection criterion, which was originally the size of the clear zones appearing around transformant colonies on the skim milk, to the initial rate of clear-zone formation. This change enabled us to obtain mutant subtilisins with activity more than 40% greater than that of the wild-type subtilisin at a frequency of 0.0002%.

In our screening program, we obtained one candidate mutant, termed m-63, showing a 100% increase in subtilisin activity. DNA sequencing revealed that m-63 possessed three mutations: GTT→ATT, GCT→ACT, and GGT→GAT, corresponding to Val→Ile at position 72 (V72I), Ala→Thr at position 92 (A92T), and Gly→Asp at position 131 (G131D), respectively. The tertiary structure of subtilisin (presented in Fig. 1) is available for considering the effects of these amino acid substitutions on cold adaptation (see Discussion). In our search, two mutations, V72I and A92T, could not be found in the previous mutant list of subtilisin BPN′ and G131D was identical to one of the triple mutations (termed 12-12) isolated by us previously (14).

Enzymatic characterization of m-63.

To characterize the kinetic properties of the newly isolated mutant subtilisin, m-63, we purified the m-63 protein from the culture supernatant of transformant B. subtilis to homogeneity on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel (data not shown). No change in the production level was observed among the mutant subtilisins under the culture conditions used. Table 1 shows the temperature dependence of m-63 subtilisin at various temperatures based on kinetic parameters with AAPF as a synthetic substrate. The hydrolytic activity, kcat/Km, of m-63 subtilisin gradually became higher than that of the wild type, approaching a 100% increase, when the temperature was reduced from 50 to 10°C. In this case, cold adaptation was achieved mainly by the decrease in the Km value in a temperature-dependent manner.

TABLE 1.

Kinetic parameters of purified wild type and m-63 mutant for hydrolysis of AAPF at various temperaturesa

| Temp (°C) and sample | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (105 s−1 M−1) | Value relative to wild type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | ||||

| Wild type | 164.9 ± 14 | 242.2 ± 7 | 6.8 | 1.0 |

| m-63 | 145.6 ± 2 | 158.0 ± 5 | 9.2 | 1.4 |

| 37 | ||||

| Wild type | 73.8 ± 6 | 190.1 ± 9 | 3.9 | 1.0 |

| m-63 | 62.4 ± 2 | 109.5 ± 5 | 5.7 | 1.5 |

| 25 | ||||

| Wild type | 36.0 ± 3 | 141.9 ± 6 | 2.5 | 1.0 |

| m-63 | 30.1 ± 1 | 76.6 ± 5 | 3.9 | 1.6 |

| 10 | ||||

| Wild type | 20.6 ± 2 | 135.3 ± 5 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| m-63 | 20.9 ± 1 | 68.6 ± 7 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

Enzyme activity was assayed with acetone-precipitated subtilisin samples and AAPF as the substrate. Enzyme concentrations were estimated by active-site titration with Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor. Details for assay are described in Materials and Methods. kcat and Km values are given as means and standard deviations.

Effect of the mutation at each position.

To analyze the contribution of each mutation to cold adaptation, we then divided the triple mutations in the m-63 subtilisin gene into three single mutations and three double mutations by site-directed mutagenesis and restriction enzyme digestions. The G131D mutant was isolated in the previous study (14). With the same purification procedure as that used for the wild-type subtilisin, three single-mutant subtilisins (V72I, A92T, and G131D) and three double-mutant subtilisins (V72I/A92T, A92T/G131D, and G131D/V72I) were purified to a high degree from the culture supernatant of each B. subtilis transformant. Comparison of hydrolytic activity at 10°C was performed for the wild type, triple mutant (m-63), three single mutants, and three double mutants based on the kcat/Km value. As shown in Table 2, both the A92T and G131D mutations were found to contribute positively to the increase in subtilisin activity, with the same level of a 40% increase, while the V72I mutation reduced the activity to 70% that of the wild type subtilisin. It is noteworthy that the combination of all three mutations, each of which caused a different change in activity, produced the highest activity (100% increase).

TABLE 2.

Kinetic parameters of purified wild type, m-63 mutant, and its derivatives for hydrolysis of AAPF at 10°Ca

| Sample | kcat (s−1) | Km (μM) | kcat/Km (105 s−1 M−1) | Activity relative to wild type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | 20.6 ± 2 | 135.3 ± 5 | 1.5 | 1.0 |

| m-63 | 20.9 ± 1 | 68.6 ± 7 | 3.0 | 2.0 |

| V72I | 18.3 ± 1 | 184.3 ± 12 | 1.0 | 0.7 |

| A92T | 14.6 ± 1 | 70.6 ± 7 | 2.1 | 1.4 |

| G131D | 23.5 ± 2 | 107.1 ± 7 | 2.2 | 1.4 |

| V72I/A92T | 17.2 ± 1 | 78.9 ± 8 | 2.2 | 1.4 |

| V72I/G131D | 21.5 ± 1 | 157.3 ± 7 | 1.4 | 0.9 |

| A92T/G131D | 19.6 ± 1 | 80.4 ± 3 | 2.4 | 1.6 |

The enzyme activity assay was carried out as described in Materials and Methods. kcat and Km values are given as means and standard deviations.

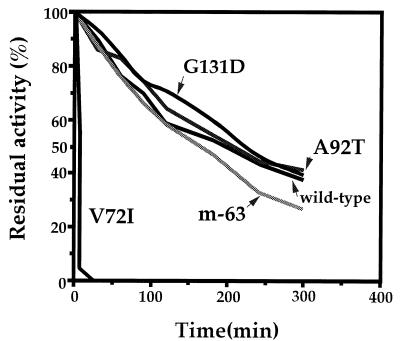

Thermal stability of the wild-type and mutant subtilisins.

We examined the thermal stability of mutant subtilisins along with that of the wild-type subtilisin. The half time of enzyme inactivation was 230 min for G131D, 210 min for A92T, 205 min for the wild type, and 175 min for m-63, as presented in Fig. 2. Clearly, the V72I mutant subtilisin was significantly sensitive to heat treatment at 60°C, indicating that this mutation might confer a thermolabile character on the enzyme. Strikingly, the triple mutant m-63 showed recovery of thermal stability from the low level caused by V72I to 76% of that of the wild-type subtilisin by combination of the effect of V72I with that of the other two mutations (A92T and G131D). The difference in stabilization free energy at 60°C between m-63 and the wild-type subtilisin was estimated to be 0.44 kJ · mol−1 according to the equation ΔΔG = 2.3RT log (205/175). However, it is unclear whether m-63 was more stable than wild-type subtilisin at 10°C.

FIG. 2.

Thermal stability of the wild-type and mutant subtilisins. The residual enzyme activity after exposure to 60°C for various time intervals was assayed at 25°C by adding purified samples to 100 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.6) containing 0.1 mM AAPF and 2 mM CaCl2.

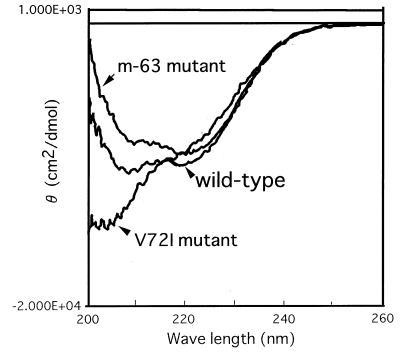

CD spectral analysis.

Differences in the CD spectra of the m-63 mutant, V72I mutant, and wild-type subtilisin were observed at 10°C (Fig. 3), suggesting that m-63 adopts native folding and that V72I has nonnative folding at this temperature.

FIG. 3.

CD spectra of the wild-type and mutant subtilisins. The CD spectrum for each sample solution was recorded at 10°C with a JASCO-J500 CD spectrophotometer.

DISCUSSION

The final goal of the present project is to create an efficient cold-adapted subtilisin from the mesophilic form. One strategy for achieving this involves performing sequential random mutagenesis on the gene encoding the enzyme to construct a huge mutant library and then screening the resulting proteins. In this process, there are two methods for producing sequential evolution. First, in each generation, a single improved variant derived from the wild type is chosen as the parent for the next generation, and sequential cycles allow the evolution of the desired features. The second approach is that used in the present study. We carried out random mutagenesis to enhance the enzyme activity at a low temperature via multistep mutations, consisting of a primary mutation causing a loss of activity and a secondary mutation causing recovery of activity. In the first study, this intragenic suppression-type mutation was technically advantageous in allowing us to obtain, as a positive selection, improved mutant subtilisins from the mutant subtilisins with reduced activity, compared to a screening from the library including the wild-type molecules and molecules with apparently increased activity (14).

By applying the improved system based on the initial rate of clear-zone formation, we obtained a cold-adapted mutant subtilisin, m-63, with proteolytic activity 100% higher than that of the wild type at 10°C. The negative mutation for proteolytic activity, V72I, is located in the internal α-helical structure (between His64, one of the catalytic triad residues, and Ala73), which is the most highly conserved region in all the members of the subtilisin protease family (generally termed subtilases) (11). However, the aliphatic and nonpolar amino acids Ile (20 times), Val (10 times), Ala (3 times), Leu (1 time), and Met (1 time) are present at this position in this order (the number indicates occupation frequency) in the 35 subtilase proteins. Reduction of subtilisin activity by this mutation resulted from an increase in the Km value rather than a decrease in kcat. Analysis of thermal stability and CD spectra suggested that the V72I mutant is very fragile even at 10°C.

The A92T mutation contributed positively to the increased in activity, due mainly to the decrease in Km. This position corresponds to the middle of the β-strand (positions 89 to 94), whose amino acid sequence is not strictly conserved. Also, another positively contributing mutation, G131D, was present at position 131, which corresponds to the N-terminal region of the α-helix, close to but on the reverse side of the substrate binding area. Previously, this mutation had been shown to be a suppressor that compensated for the defect of Ca2+ binding-mediated stabilization caused by mutation of D197N (14). It is unclear why the effect of the triple mutation (+100% for m-63) is not a simple sum (+50%) of the effects of the single mutations (−30% for V72I, +40% for A92T, and +40% for G131D). The successful increase in activity created by the triple mutations was achieved by a dominant contribution of the Km value without any reduction in kcat. However, gradual reduction of the kcat value was observed when the temperature was shifted up from 10 to 50°C compared with the case for wild-type subtilisin.

Furthermore, the addition of two mutations, A92T and G131D, compensated for the low level of thermal stability caused by mutation V72I and brought the stability at 60°C close to that of wild-type subtilisin (Fig. 2) with a concomitant change in the secondary structure at 10°C (Fig. 3). The kcat/Km values of the two double mutants, with the V72I/A92T and V72I/G131D mutations, strongly suggested that the unpredictable suppression of proteolytic activity and structural stability in the mutant with the V72I mutation could be brought about by a cooperative effect of the two mutations A92T and G131D. The fact that the combination of the two positively contributing mutations, A92T and G131D, unexpectedly gave a lower activity (kcat/Km = 2.4) than did m-63 (kcat/Km = 3.0) (Table 2) appeared to indicate that the role of V72I is more subtle when combined with A92T and G131D, although the single mutation V72I contributes negatively to both activity and thermal stability.

It has been shown that the mutation-screening system employed here would be useful for seeking potential positions related to the cold adaptation of subtilisin. Therefore, mutant subtilisins with much higher activity than that of m-63 could be obtained from a complete set of proteins bearing mutations at each of the positions (positions 72, 92, and 131) identified in this study.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank S. Kojima, Gakushuin University, for his valuable cooperation in measuring the CD spectra. We are also indebted to T. Nonaka, Nagaoka University of Technology, for his useful suggestion based on the molecular modeling.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid (70216828 to S.T. and 04660126 to H.M.) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan and a grant (to S.T.) from the Nissan Foundation and research aid (to H.M.) from Nagase & Co. Ltd.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chen K, Arnold F. Tuning the activity of an enzyme for unusual environments: sequential random mutagenesis of subtilisin E for catalysis in dimethylformamide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5618–5622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.12.5618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davail S, Feller G, Narinx E, Gerday C. Cold adaptation of proteins: purification, characterization, and sequence of the heat-labile subtilisin from the antarctic phsychrophile Bacillus TA41. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:17448–17453. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feller G, Narinx E, Arpigny J L, Aittaleb M, Baise E, Genicot S, Gerday C. Enzymes from psychrophilic organisms. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1996;18:189–202. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ishiwa H, Shibahara H. New shuttle vectors for Escherichia coli and Bacillus subtilis. II. Plasmid pHY300PLK, a multi purpose cloning vector with a polylinker, derived from pHY460. Jpn J Genet. 1985;60:235–243. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ito W, Ishiguro H, Kurosawa Y. A general method for introducing a series of mutants into cloned DNA using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1991;102:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90539-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kano H, Taguchi S, Momose H. Cold adaptation of a mesophilic serine protease, subtilisin, by in vitro random mutagenesis. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1997;47:46–51. doi: 10.1007/s002530050886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liao H, McKenzie T, Hageman R. Isolation of a thermostable enzyme variant by cloning and selection in a thermophile. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:576–580. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.3.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masuda-Momma K, Shimakawa T, Inouye K, Hiromi K, Kojima S, Kumagai I, Miura K, Tonomura B. Identification of amino acid residues responsible for the changes of absorption and fluorescence spectra on the binding of subtilisin BPN′ and Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor. J Biochem. 1993;114:906–911. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Matsubara H, Kasper C B, Brown D M, Smith E L. Subtilisin BPN′. I. Physical properties and amino acid composition. J Biol Chem. 1965;240:1125–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Siezen R J, de Vos W M, Leunissen J A M, Dijkstra B W. Homology modelling and protein engineering strategy of subtilases, the family of subtilisin-like serine proteinases. Protein Eng. 1991;4:719–737. doi: 10.1093/protein/4.7.719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taguchi S, Maeno M, Momose H. Extracellular production system of heterologous peptide driven by a secretory protease inhibitor of Streptomyces. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1992;36:749–753. doi: 10.1007/BF00172187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Takeuchi Y, Satow Y, Nakamura K T, Mitsui Y. Refined crystal structure of the complex of subtilisin BPN′ and Streptomyces subtilisin inhibitor at 1.8 angstroms resolution. J Mol Biol. 1991;221:309–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tange T, Taguchi S, Kojima S, Miura K, Momose H. Improvement of a useful enzyme (subtilisin BPN′) by an experimental evolution system. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1994;41:239–244. doi: 10.1007/BF00186966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33:103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao H, Arnold F H. Functional and nonfunctional mutations distinguished by random recombination of homologous genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7997–8000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.15.7997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]